Introduction

Spirituality is considered an important dimension of quality of life in cancer (Peterman et al. Reference Peterman, Fitchett and Brady2002; Weaver and Flannelly Reference Weaver and Flannelly2004). It encompasses the beliefs and practices of religious communities, and it also includes dimensions of meaning-making, purpose, and transcendence in life (Oman Reference Oman2013). One of the most widely used scales is the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy: Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp) (Canada et al. Reference Canada, Fitchett and Murphy2012; Peterman et al. Reference Peterman, Fitchett and Brady2002). The FACIT-Sp uses two factors to evaluate important aspects of spirituality: meaning/peace and faith. The meaning/peace factor assesses meaning, peace, and purpose in life; while the faith factor assesses the strength and effectiveness of one’s own faith (Canada et al. Reference Canada, Fitchett and Murphy2012; Peterman et al. Reference Peterman, Fitchett and Brady2002). Addressing spirituality in healthcare is essential for person-centered care, which is defined by the Institute of Medicine (2001) as “care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”

For Latinos, spirituality is an important core cultural value that can facilitate resilience in the face of cancer (Hunter-Hernandez et al. Reference Hunter-Hernandez, Costas-Muniz and Gany2015). It can help Latino people with cancer to cope with active treatment and cope with the consequences of cancer during survivorship (Hunter-Hernandez et al. Reference Hunter-Hernandez, Costas-Muniz and Gany2015). In a systematic review (Samuel et al. Reference Samuel, Mbah and Elkins2020) of the quality of life of Latino cancer survivors, spiritual well-being and spirituality-based coping were higher among Latino cancer survivors compared with other racial/ethnic groups in 50% of studies. These research articles also documented multiple religious and spiritual practices for coping with cancer, including prayer, faith, finding meaning and peace, religious or church attendance, and relationship with God (Samuel et al. Reference Samuel, Mbah and Elkins2020). The main findings were that Latino survivors commonly reported spirituality as a source of strength and comfort, and spirituality/religious coping was associated with lower anxiety, fatigue, and depression and higher general quality of life and functional well-being (Samuel et al. Reference Samuel, Mbah and Elkins2020).

In a study (Hunter-Hernandez et al. Reference Hunter-Hernandez, Costas-Muniz and Gany2015) with a sample of Latina breast cancer survivors, spiritual well-being and the factors of meaning/peace and faith were associated with higher quality of life and lower levels of depression; and the meaning/peace factor was the main predictor of an increase in quality of life and a reduction in depression (Garduño-Ortega et al. Reference Garduño-Ortega, Morales-Cruz and Hunter-Hernández2021). Spiritual well-being and the meaning/peace subscales have also been found to correlate with lower financial toxicity in Latina breast cancer survivors (Echeverri-Herrera et al. Reference Echeverri-Herrera, Nowels and Qin2022). Furthermore, in a longitudinal study with Latina women diagnosed with cancer, greater baseline spiritual well-being scores were associated with less concurrent distress, better quality of life, and emotional and functional well-being over time (Barata et al. Reference Barata, Hoogland and Small2022).

The association between spirituality and adjustment appears to be stronger for meaning- and peace-related well-being than for faith- or religious-related well-being in Latina survivors and Latinas undergoing cancer treatment (Barata et al. Reference Barata, Hoogland and Small2022; Garduño-Ortega et al. Reference Garduño-Ortega, Morales-Cruz and Hunter-Hernández2021). Nevertheless, religious concerns, practices, and coping are frequently present and sources of comfort among Latinos as they adapt to the cancer experience (Ashing-Giwa et al. Reference Ashing-Giwa, Padilla and Bohorquez2006; Culver et al. Reference Culver, Arena and Wimberly2004). Latinas diagnosed with breast cancer are more likely to seek and receive counseling from a spiritual leader, priest, or pastor after a cancer diagnosis (Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Garduno-Ortega and Hunter-Hernandez2021b, Reference Costas-Muniz, Hunter-Hernandez and Garduno-Ortega2017). Additionally, mental health providers of Latinos with cancer cite religious and spiritual beliefs and concerns as ones that were addressed when counseling Latino patients (Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Castro-Figueroa and Torres2021a).

However, few studies have focused on the existential needs of Latinos with cancer, and no studies have focused on the needs of Latinos with advanced cancer. Moadel et al. (Reference Moadel, Morgan and Fatone1999) found that between 50% and 65% of Latinos with cancer reported wanting help to find hope, meaning in life, and spiritual resources, and wanting to talk to someone about finding peace and meaning in life. Among these patients, 25% to 51% reported unmet spiritual or existential needs, which included wanting help in overcoming fears, finding hope, talking about peace of mind, finding meaning in life and spiritual resources, and having someone to talk to about the meaning of life and death (Moadel et al. Reference Moadel, Morgan and Fatone1999).

Several systematic reviews (Teo et al. Reference Teo, Krishnan and Lee2019; Uitterhoeve et al. Reference Uitterhoeve, Vernooy and Litjens2004) examining interventions for people with advanced cancer, or at the end of life, have shown that the interventions with the most evidence-based findings are Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) (Vos and Vitali Reference Vos and Vitali2018), dignity therapy (Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Hou2020), and managing cancer and living meaningfully (Troncoso et al. Reference Troncoso, Rydall and Hales2019). Many of these therapies have been implemented in different modalities (e.g., individual, group), cancer types (e.g., breast), groups (e.g., caregivers, parents), settings (e.g., palliative care, hospice), and countries and populations (e.g., Chinese, Canadians) (Teo et al. Reference Teo, Krishnan and Lee2019; Uitterhoeve et al. Reference Uitterhoeve, Vernooy and Litjens2004). However, MCP is the only intervention adapted and tested for Latinos with advanced cancer (Costas-Muñiz et al. Reference Costas-Muñiz, Torres-Blasco and Castro-Figueroa2022; Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Castro-Figueroa2020, Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Gany2023; Torres-Blasco et al. Reference Torres-Blasco, Castro-Figuero and Garduno-Ortega2020a, Reference Torres-Blasco, Castro and Crespo-Martin2020b; Reference Torres Blasco, Costas Muñiz and Zamore2022b). Studies have shown that MCP is acceptable to Latinos from the USA (Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Castro-Figueroa2020, Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Gany2023) and Puerto Rico (Torres-Blasco et al. Reference Torres-Blasco, Castro-Figuero and Garduno-Ortega2020a, Reference Torres-Blasco, Castro and Crespo-Martin2020b) and with Latino caregivers (Torres-Blasco et al. Reference Torres-Blasco, Costas-Muñiz and Zamore2022a).

MCP is a manualized psychotherapy intervention developed for the specific spiritual and meaning-making needs of people with advanced disease (Breitbart Reference Breitbart2002; Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Pessin and Rosenfeld2018; Breitbart and Poppito Reference Breitbart and Shannon2014; Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010, Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012, Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015). The basic concepts of MCP include: (1) Meaning of life, (2) Desire to find meaning, and (3) Freedom to find meaning in existence and to choose the attitude toward suffering. The main sources of meaning in life are derived from creativity (work, deeds, and dedication to causes), experience (art, nature, humor, love, relationships, and roles), attitude (attitude one takes toward suffering and existential problems), and historical context (having a sense of past, present and future legacy is critical for meaning-making) (Breitbart Reference Breitbart2002).

In this article, we examine associations between spiritual well-being, faith and peace/meaning, with quality of life, depression, anxiety, distress, and hopelessness. Given the prior evidence with samples of Latinos with cancer undergoing treatment and in remission, we hypothesize a strong association of peace/meaning with psychological adjustment in people with advanced disease. We also sought to quantitatively document the importance, acceptability, and relevance of existential themes as Latinos adjust to advanced cancer. Finally, we examined the narratives of meaning-making and sources of meaning for Latinos with advanced cancer and their alignment with the themes of MCP.

Methods

Study design and procedure

A mixed-methods, concurrent, integrative approach was used for this study. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from Latinos with advanced cancer.

Participants

Latino individuals with advanced cancer were recruited from two cancer clinics in New York City and one clinic in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Eligible patients had been diagnosed with advanced cancer (stages III or IV), identified as Latino, and were fluent in Spanish. After initial prescreening, which was limited to Latino/Hispanic ethnicity and Spanish surname documented in the medical record, 1274 people’s records were fully screened, and 267 people were eligible. Two hundred sixty-seven eligible people were approached by research staff from August 2015 through March 2022. Forty-six percent refused to participate (i.e., time constraints and lack of interest), yielding a sample of 142 people with advanced cancer. A nested sample of the first consecutive 24 participants was invited to complete in-depth, semi-structured interviews. All participants provided their written consent. This research was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of each institution: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s IRB #15-076, Lincoln Medical Center’s IRB#16-011, and Ponce Health Sciences University’s IRB #161129.

Assessments

Both quantitative and qualitative assessments were used, which included validated scales, an investigator-developed survey, and a semi-structured interview guide. Demographic and medical information was abstracted from the patients’ medical records, including information regarding age, marital status, income, education, preferred language, place of residence, clinical diagnosis, clinical stage, treatment status, and type of treatments received (including cancer and psychiatric treatments). A brief demographic section was also added in the quantitative assessments that included questions about age, marital status, income, education, employment status, language, birth country, place of residence, clinical diagnosis, cancer stage, years since diagnosis, and treatments received. Medical records were used as the primary sources of information; data collected from the questionnaire were supplemental.

All the instruments included have been validated in Spanish. The FACIT Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp-12) was used to assess the nature and extent of spiritual well-being (Peterman et al. Reference Peterman, Fitchett and Brady2002). This measure generates two sub-scales: Faith (the importance of faith/spirituality) and Meaning/Peace (one’s sense of meaning and purpose in life); scores range from 0 to 48 and it is validated for Spanish (Canada et al. Reference Canada, Fitchett and Murphy2012). The Spanish version (Herrero et al. Reference Herrero, Blanch and Peri2003) of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure clinical levels of depression and anxiety. The HADS consists of 14 items (score range 0–42), including a 7-item anxiety subscale (score range 0–21) and a 7-item depression subscale (score range 0–21).

The Spanish version (Aliaga Reference Aliaga, Rodríguez and Ponce2006) of the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) was used to measure degrees of pessimism and hopelessness.(Beck et al. Reference Beck, Weissman and Lester1974) The BHS includes 20 true/false questions (scores range 0–20). The Spanish version (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Hernandez and Bonomi1998) of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) is a 27-item questionnaire composed of general questions divided into four main domains: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being (Cella et al. Reference Cella, Tulsky and Gray1993). Finally, the main author and investigator developed a 27-item survey that included 22 questions assessing the acceptability of the goals and existential concepts and themes related to MCP, existential issues that would benefit from support, and important themes for counseling or psychotherapy, including spiritual and existential issues (Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Castro-Figueroa2020, Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Gany2023).

The interview guide included open-ended questions about (1) patients’ meaning-making processes and coping, (2) sources of meaning in their lives, (3) spirituality, and (4) meaning-making after their cancer diagnosis. The exploration of sources of meaning was guided by the definition and use of these concepts in MCP:

1. Historical Sources of Meaning: life as a legacy that has been given (past), that one lives (present), and that one gives (future).

2. Attitudinal Sources of Meaning: encountering life’s limitations and choosing one’s attitude.

3. Creative Sources of Meaning: Engaging in life fully requires creativity, responsibility, courage, and accomplishments in life.

4. Experiential Sources of Meaning: Connecting with life, such as through love, beauty/nature, and joy/humor.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software, version 20 (IBM North America, New York, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were utilized for sample characterization of demographic and clinical variables. Frequencies and percentages were reported for the items assessing the acceptability of the goals, existential concepts, and themes related to MCP. Pearson’s r correlations were used to evaluate associations between spiritual well-being factors, quality of life, and mood symptoms. Multivariate regression models were used to examine the association between spiritual well-being, meaning/peace, and faith with quality of life and mood symptoms. Models were adjusted for demographics (age, education, marital status, and birth country) covariates. A two-sided p-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Qualitative analyses

Qualitative analyses were guided by the seven steps of the Framework Method (Gale et al. Reference Gale, Heath and Cameron2013): (1) The 24 interviews were transcribed. (2) Three coders became familiar with the transcripts. (3) The coders used open coding (coding anything that might be relevant from as many different perspectives as possible) for the transcripts using the report and query functions of the qualitative analysis software, ATLAS.ti. (4) All coders met to discuss points of divergence and convergence. These discussions continued until the group reached consensus on code meanings and applications. The coders developed the code book and analytical framework by defining the codes (from open coding) and grouping them into working categories. The coding dictionary and analytical framework were supplemented with and guided by codes reflecting MCP concepts (and definitions), including attitudinal, historical, creative, and experiential sources of meaning. (5) The coders applied the analytical framework; the three coders coded all the responses and met to discuss points of divergence and convergence until the group reached consensus. Intercoder reliability was conducted through team-based consensus building. (6) Using a spreadsheet to generate a matrix, the qualitative data (quotations) were “charted” into a matrix of the analytical framework. (7) The data were discussed and interpreted for the generation of this research article. All the investigators had expertise in qualitative analysis, and the first author moderated these discussions.

Results

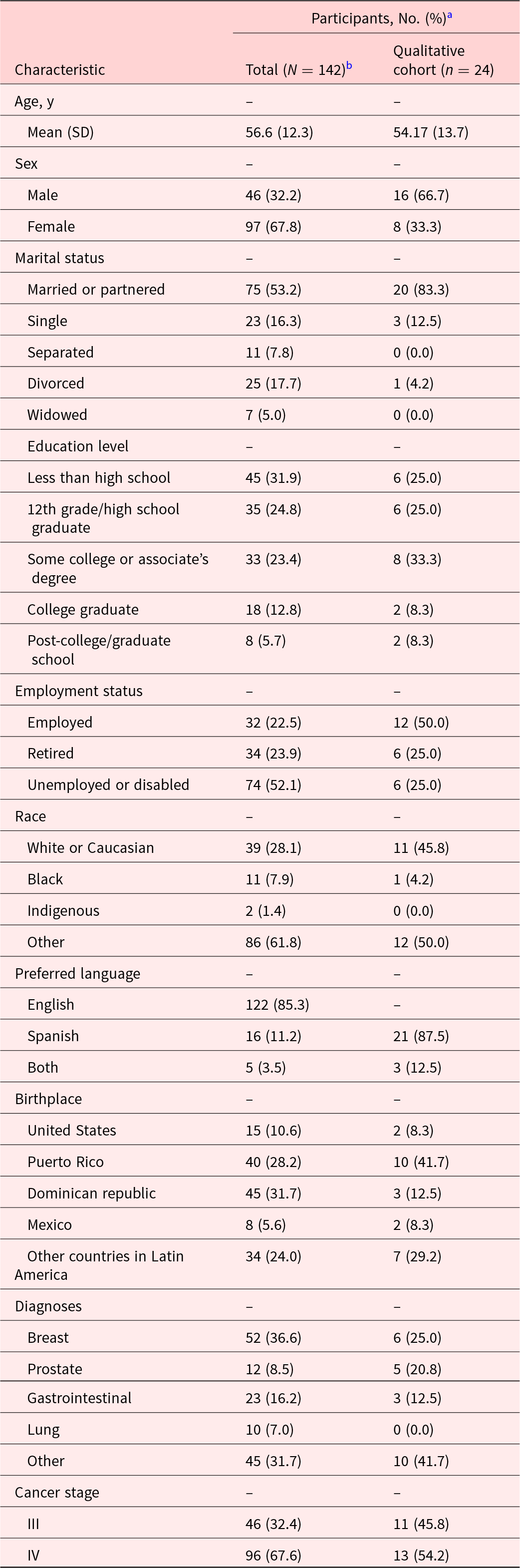

The sample (see Table 1) included 142 Latinos with advanced cancer (67.6% stage IV and 32.4% stage III), and the most frequent diagnoses were breast (36.6%) and gastrointestinal (16.2%) cancers. The mean age was 57 years. Most patients were female (67.8%), slightly more than half were married or partnered (53.2%), almost one third had less than a high school education (31.9%), and 41.9% had at least some college education. Slightly more than half of the sample reported being unemployed or on disability (52.1%). All spoke fluent Spanish, and most reported Spanish language preference (85.3%). The participants were born predominantly in the Dominican Republic (31.7%), Puerto Rico (28.2%), and the continental USA (10.6%).

Table 1. Characteristics of Latinos with advanced cancer who participated in the study

a Values are no. (%), unless otherwise noted.

b Frequencies may not be based on the total sample, due to missing data, and percentages may not equal 100%, due to rounding.

Association of spiritual well-being with psychological adjustment

Spiritual well-being as a whole and both factors (faith and peace/meaning) were associated with lower anxiety (r = −0.53, p < .001; r = −0.27, p = .001; r = −0.58, p < .001, respectively), depression (r = −0.62, p < .001; r = −0.37, p < .001; r = −0.64, p < .001, respectively), combined anxiety and depressed mood (r = −0.63, p < .001; r = −0.36, p < .001; r = −0.67, p < .001, respectively), hopelessness symptoms (r = −0.60, p < .001; r = −0.29, p = .001; r = −0.66, p < .001, respectively) and with higher quality of life (r = 0.62, p < .001; r = 0.33, p < .001; r = 0.68, p < .001, respectively). The meaning/peace dimension showed stronger negative associations with emotional suffering than the faith dimension. In multivariate regression models controlling for age, education, marital status, and time since diagnosis, spiritual well-being significantly predicted higher quality of life (β = .81, p < .001) and lower depression level scores (β = −.26, p < .001).

Further, in models including the meaning/peace and faith subscales (Table 2), the meaning/peace factor showed a stronger relationship with mood, anxiety, depression, hopelessness symptoms, and quality of life level scores (β = −.85, p < .001; β = −.41, p < .001; β = −.44, p < .001; β = −.35, p < .001; β = 2.20, p < .001; respectively). Faith had no relationship with any of the symptoms (mood, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness) or quality of life when controlling for the meaning/peace factor.

Table 2. Multivariate regression analyses predicting quality of life and depression

a Controlling for age, education, marital status, and birth country.

Acceptability of existential themes: Quantitative analysis

Most patients reported the following strategies as “quite a bit” to “extremely” important for coping with the cancer diagnosis (see Table 3): Maintaining hope (87.3%); Being responsible for myself after my cancer diagnosis (83.8%); Understanding what the purpose is of my life after being diagnosed with cancer (80.3%); Making-meaning in my life or thinking about my purpose in life (79.6%); and Making sense of the cancer experience (78.2%). Additionally, most patients found the following MCP sources of meaning items as acceptable: The love that I have for my loved ones has helped me to cope with my cancer diagnosis (82.4%); Maintaining a good sense of humor has helped me to cope with my cancer diagnosis (78.9%); The love that I have for life has helped me to cope with my cancer diagnosis (76.8%); and Finding beauty in music, nature and other life experiences has helped me to cope with my cancer diagnosis (76.8%). Finally, the most frequently endorsed important themes of counseling were: Coping with cancer (95.1%), changes in life after cancer (95.1%), finding purpose in life (89.4%), family issues (82.4%), spiritual issues (74.6%), and religious issues (71.8%).

Table 3. Importance and acceptability of existential themes (N = 142)

Meaning-making and sources of meaning themes: Qualitative analyses

Themes about meaning-making and sources of meaning as used in MCP (see Table 4) were qualitatively explored. Recurrent themes included meaning-making coping, attitudinal sources of meaning, social/family sources of meaning, spiritual and religious sources of meaning, historical sources of meaning-legacy, creative sources of meaning, and experiential sources of meaning.

Table 4. Qualitative results

When prompted about the main ways patients find meaning and purpose in their lives, the most shared themes included self-love, love for others, spirituality, experiential sources of meaning in life, and attitude/hope.

Attitudinal sources of meaning. When patients were asked about the ways they find meaning and purpose in choosing their attitude to face life situations, the main themes that emerged were positive attitude, self-love, love for life, enjoy life (passion about life), fighting spirit, surviving, finding purpose in the situation, and active learning. An exemplary quote of choosing a positive attitude was, “It is logical that it can affect me. But if you don’t instantly reconsider and if you become negative, the illness will knock you down more. So, I try to think positively so that the illness doesn’t take me away.”

Social/family sources of meaning. Patients often shared that they find meaning through social and family connections, including love for the family, happiness of children and family, joy for having loved ones, helping others, and being an example for others. A quote illustrating family connection is, “To love the family, my children, my grandchildren, my siblings, right? and all the people, well, that love me, although sometimes we feel rejected too… .”

Spiritual and religious sources of meaning. Spirituality, religiosity, spiritual growth, and trusting in God were cited as sources of meaning for many patients. A quote that illustrates spirituality is “Spirituality being calm with myself, being well, not being afraid. I’m not afraid. Thanks for what I had to live through and for where I have to go. Nothing else… .”

Other sources of meaning. Some of the creative sources of meaning cited by patients were work, having goals and projects, and music. Some of the experiential sources of meaning included loving the family and finding beauty in love, nature, music, children, or animals. Sources of joy and humor included children and family happiness, and enjoying life. A few patients shared their legacy (historical sources of meaning), which included supporting the academic goals of their children, family cohesion (union), and being remembered in a positive light. The meaning-making ways of coping and/or sources of meaning cited more frequently (by eight or more patients) were choosing a positive attitude (n = 12), enjoying life (n = 8), fighting spirit (n = 10), surviving (n = 8), family (n = 18), and spirituality (n = 13). Furthermore, family happiness, helping others, spiritual growth, work, and religiosity were each cited by five patients.

Discussion

This study examined associations between adjustment and spiritual well-being, meaning/peace, and faith in Latinos with advanced cancer. It explored the importance of existential themes and coping, and the narratives of meaning-making and sources of meaning. Spirituality is a helpful coping resource for many Latinos facing an advanced diagnosis (Breitbart Reference Breitbart2002; Lin and Bauer-Wu Reference Lin and Bauer-Wu2003; Troncoso et al. Reference Troncoso, Rydall and Hales2019). In this study, spiritual well-being and its two dimensions, meaning/peace and faith (related to spiritual beliefs), were associated with lower mood symptoms (depression, anxiety, and hopelessness) and better quality of life in Latinos with advanced cancer. However, only meaning/peace was associated with a significantly better improvement in quality of life and reduction of mood symptoms when controlling for the faith factor. Previous literature has shown the importance of faith and religiosity in the Latino community (Culver et al. Reference Culver, Arena and Antoni2002, Reference Culver, Arena and Wimberly2004; Garduño-Ortega et al. Reference Garduño-Ortega, Morales-Cruz and Hunter-Hernández2021; Hunter-Hernandez et al. Reference Hunter-Hernandez, Costas-Muniz and Gany2015; Moadel et al. Reference Moadel, Morgan and Fatone1999; Samuel et al. Reference Samuel, Mbah and Elkins2020), but our findings highlight that meaning/peace is more critical for emotional adjustment and overall well-being. Our findings are also consistent with results from a previous study involving Latina breast cancer survivors that found a stronger association between peace/meaning with depression and quality of life than faith (Garduño-Ortega et al. Reference Garduño-Ortega, Morales-Cruz and Hunter-Hernández2021).

Further, upon exploration of the acceptability of existential themes and existential coping in this sample of people with advanced cancer, it was revealed that maintaining hope, understanding purpose in life after the diagnosis, and making-meaning in life were themes endorsed by more than 80% of the participants as important. Most (89%) also stated that finding purpose in life was an important goal of counseling. These findings support the importance of spiritual coping in Latinos with advanced cancer, with a focus on existential coping, not only religious coping. Further, in our inquiry, a higher proportion endorsed addressing meaning or existential themes as a therapeutic goal over religious themes.

Lastly, the themes that were more frequently discussed in the qualitative interviews that explored meaning-making coping, and sources of meaning were attitudinal, social/family and spiritual sources of meaning. Considering that spirituality is a core cultural value for a large part of the Latino population (Janz et al. Reference Janz, Mujahid and Hawley2009), as it was for those in the current study, it is imperative to address and strongly encourage finding and maintaining meaning and peace (sense of meaning and purpose in life, and peace) while facing advanced cancer and end of life in Latino cancer patients. The roles of meaning and meaning-making have been extensively explored with non-Hispanic populations. Patients who report spiritual well-being (hope and meaning in life) are better equipped to cope with the process of terminal cancer and discovering meaning in the experience (Lin and Bauer-Wu Reference Lin and Bauer-Wu2003).

Further, finding meaning and purpose were often experienced through social and family connections, including love for the family, happiness of children and family, joy for having loved ones, helping others, and being an example for others. This finding is consistent with numerous studies showing that Latinos who feel supported by their family and friends adjust better to the diagnosis (Galván et al. Reference Galván, Buki and Garcés2009; Ochoa et al. Reference Ochoa, Haardörfer and Escoffery2018).

Our findings demonstrate the importance of implementing a meaning/peace approach (sense of purpose and meaning in life, and peace) with Latinos with advanced cancer. Nelson et al. (Reference Nelson, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2002) reported similar findings with predominantly non-Latino White patients with terminal cancer and AIDS, and Garduño-Ortega et al. (Reference Garduño-Ortega, Morales-Cruz and Hunter-Hernández2021) with a sample of Latina breast cancer survivors. Both studies found that meaning/peace was a crucial factor, more critical than faith. Our study also revealed that the major ways that patients found meaning and purpose in life were through their attitude, love for others (social/family connections), spirituality, and engagement with life.

This study suggests that implementing a meaning/peace approach may positively impact the adjustment of Latino patients with cancer. Psychotherapy interventions such as MCP (Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Pessin and Rosenfeld2018, Reference Breitbart, Poppito and Rosenfeld2012) and other existential-based therapies, such as Dignity Therapy (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005), supportive-expressive therapy (Kissane and Li Reference Kissane and Li2008), and family grief therapy (Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, McKenzie and Bloch2006), have been developed to address meaning-making needs and to encourage a sense of dignity and purpose in life at the end of life. Those interventions aimed at improving psychological adjustment have proven effective in predominantly non-Latino White people with cancer. Studies to adapt and implement MCP for Latino people with cancer (Costas-Muniz et al. Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Castro-Figueroa2020, Reference Costas-Muniz, Torres-Blasco and Gany2023) and Latino caregivers (Torres-Blasco et al. 2022) are underway. Meaning-making needs should be addressed in clinical settings. Health professionals can play an essential part by identifying patients’ needs and referring patients and families to programs for help.

There were some limitations to this study. First, the patients were recruited from New York City and Puerto Rico, with a sample of people predominantly born in the Caribbean. The findings may not generalize to Latinos from other geographic locations in the USA and Latin America. Future studies should include patient samples recruited in different geographical locations to enhance cultural representation and fit of the intervention. Second, only patients with stage III and stage IV cancer were invited to participate. The cancer experience of patients at different disease stages with different prognoses could vary significantly. The findings might not be applicable to patients with early-stage disease. In future studies, analyses stratified by stage and prognosis status are warranted.

Funding

National Cancer Institute (R21 CA180831, K08CA234397, P30CA008748, U54CA132378, U54CA163068, and R21CA253555); American Cancer Society (133798-PF-19-120-01-CPPB); National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD007579, 5R25MD007607, R21MD013674, and U54MS007579). OGV is a level II scientist and receives funding support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico. The funding sources were not involved in the development of this manuscript or its study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, and/or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the awarding agencies.

Competing interests

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Editorial support

The authors thank Sonya J. Smyk, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, for editorial support. She was not compensated beyond her regular salary.