1 Introduction: The Purpose and Scope of This Element

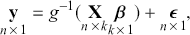

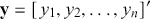

This Element is intended to extend Bayesian statistical knowledge beyond the basics. In the companion volume (Gill & Bao, Reference Gill and Bao2024) we introduced the core concepts of Bayesian inference and the mechanics for estimating simple quantities from social science data, including basic probability theory, the likelihood function, the core principle of Bayesian inference, construction of priors, expected value, and model evaluation. Here we broaden those ideas and focus on Bayesian regression modeling. New topics include Monte Carlo, Markov chains, Markov chain Monte Carlo, linear and nonlinear (generalized linear) regression, the Bayes factor, and model assessment with simulation. This is how the bulk of empirical social science work is done, so we call this work “Getting Productive.” We extend the “Getting Started” principles from Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024) here to this regression setting. Readers will get an appreciation for how the prior-to-posterior process works for common regression models that are linear, applied to dichotomous outcomes, applied to count outcomes, requiring bounded outcomes, and more.

Recall that the Bayesian statistical paradigm is perfectly suited to the type of data analysis routinely performed by social scientists since it recognizes that population parameters are not typically fixed in studies of humans, it incorporates prior knowledge from a specific literature, and it updates model estimates as new data are observed. Most empirical work in the social sciences is observational rather than experimental, meaning that there are additional challenges. Specifically: subjects are often uncooperative or not widely available, underlying systematic effects are typically more elusive than in the natural sciences, and measurement error is often significantly higher. The Bayesian approach to modeling uncertainty in parameter estimates provides a more robust and realistic picture of the data generating process because it is focused on estimating distributions rather than artificially fixed point estimates.

In Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024) the key technical skill that needed to be introduced was calculus. More specifically, integral calculus so that expected value calculations and marginalizations could be done. The key technical skill introduced here is integration with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). This is actually a computational method for not doing integral calculus because the computer does the hard and repetitive work for integrals that are very difficult or even impossible to calculate analytically. In fact, MCMC liberated the Bayesians in 1990 (more details later in Section 4.2, “Markov Chain Theory”) and allowed us to specify regression-style models that were previously unavailable for primarily calculus reasons. In essence, we let the computer explore a large multidimensional space and report its traversal, which is in proportion to the posterior probability when set up correctly. So, much of the work here is computational because computation freed the Bayesians.

The notation here is identical to Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024), but readers who have gained an appreciation for basic Bayesian inference from other sources will recognize the standard terms and formats used. We assume that current readers have seen and understood basic probability principles and Bayes’ law, likelihood functions, the core Bayesian process of generating posterior distributions from combining prior and likelihood (data) information, the role of priors in developing progressive science, integral calculus and expected value, calculating basic Bayesian quantities in R or Python, and evaluating/comparing model results. For extended details one can also reference Gill (Reference Gill2014).

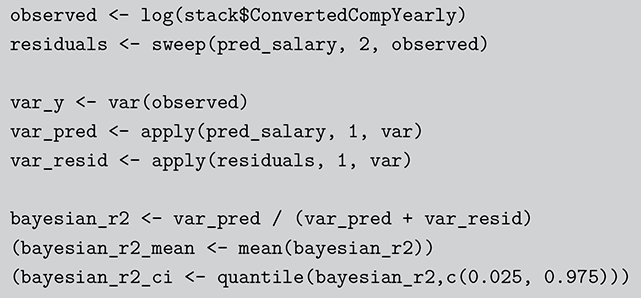

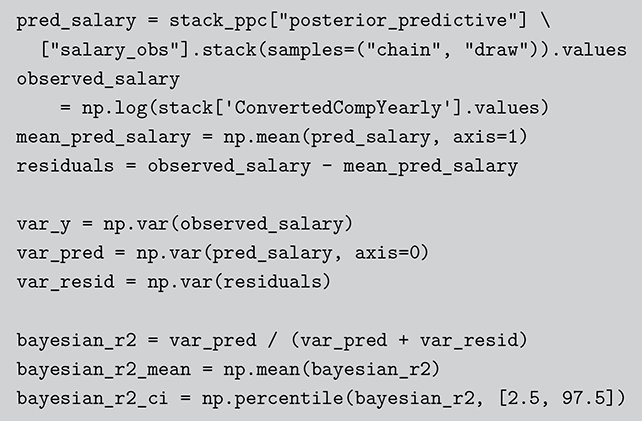

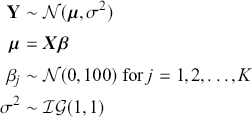

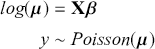

The basic regression-style structure we will work with looks like this:

(1.1)

(1.1)

where ![]() is a vector containing some outcome variable that can be measured as continuous or discrete,

is a vector containing some outcome variable that can be measured as continuous or discrete, ![]() is an “inverse link function” that is specified according to the measurement of

is an “inverse link function” that is specified according to the measurement of ![]() ,

, ![]() is a matrix of explanatory variable data organized where rows are cases and columns are variables (including a leading column of 1s for the constant), and

is a matrix of explanatory variable data organized where rows are cases and columns are variables (including a leading column of 1s for the constant), and ![]() is the residual vector. Gill and Torres (Reference Gill and Torres2019) provide a detailed and accessible introduction to such model specifications in the non-Bayesian context. These are vector and matrix structures where the dimensions are specified with the underset text in (1.1), meaning that the

is the residual vector. Gill and Torres (Reference Gill and Torres2019) provide a detailed and accessible introduction to such model specifications in the non-Bayesian context. These are vector and matrix structures where the dimensions are specified with the underset text in (1.1), meaning that the ![]() and

and ![]() vectors have

vectors have ![]() contained cases, the

contained cases, the ![]() matrix has

matrix has ![]() cases and

cases and ![]() explanatory variables, and the

explanatory variables, and the ![]() vector has

vector has ![]() coefficients to be estimated. In order to make these multidimensional structures more visually intuitive, we repeat these specifications with illustration. The vector

coefficients to be estimated. In order to make these multidimensional structures more visually intuitive, we repeat these specifications with illustration. The vector ![]() contains values of the outcome variable in a column vector:

contains values of the outcome variable in a column vector:

(1.2)

(1.2)

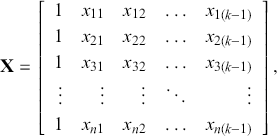

(the “prime” at the end of this statement turns the shown row vector into a column vector). The matrix ![]() contains cases along rows and explanatory variables down columns:

contains cases along rows and explanatory variables down columns:

(1.3)

(1.3)

with a leading column of ![]() s (e.g. there are

s (e.g. there are ![]() explanatory variables here) to estimate a constant (the predicted value of

explanatory variables here) to estimate a constant (the predicted value of ![]() when all the values of the explanatory variables are set to zero,

when all the values of the explanatory variables are set to zero, ![]() ). The vector

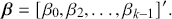

). The vector ![]() contains the targets of regression analysis, which tell us how important or unimportant each associated explanatory variable is in this particular context:

contains the targets of regression analysis, which tell us how important or unimportant each associated explanatory variable is in this particular context:

(1.4)

(1.4)

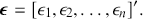

The vector ![]() contains values of the observed residuals (disturbances, errors) in a column vector:

contains values of the observed residuals (disturbances, errors) in a column vector:

(1.5)

(1.5)

Without such matrix notation, statistical regression models are very awkward to describe in formal terms. The simplicity of (1.1) belies its immense power and flexibility: it can include interactions, hierarchies (fixed and random effects), time-series components, different measurements of variables, different link functions, and more.

Notice also that we do not use the term “independent variables” here. This is because in the social sciences there is no such thing as a set of independent variables in this context with real data. That term is more appropriate for the physics or chemistry lab where the variables can actually be independent of each other in a way that is impossible when studying humans. Note that “covariate” is an acceptable term but slightly less informative than “explanatory variable.”

We also want to distinguish between ![]() , the true but unknown value of the regression vector, and

, the true but unknown value of the regression vector, and ![]() , the estimate of this quantity. Of course, since we are estimating Bayesian models, we will actually produce a distribution for

, the estimate of this quantity. Of course, since we are estimating Bayesian models, we will actually produce a distribution for ![]() , which can be summarized with measures of centrality, dispersion, and quantiles. Since accurately estimating the true distribution of

, which can be summarized with measures of centrality, dispersion, and quantiles. Since accurately estimating the true distribution of ![]() is our goal, we will judge the quality of the individual terms in

is our goal, we will judge the quality of the individual terms in ![]() by their diffusion: broad posteriors indicate higher uncertainty than narrow posteriors. As discussed in Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024), we can also evaluate the evidence of a marginal effect for a given

by their diffusion: broad posteriors indicate higher uncertainty than narrow posteriors. As discussed in Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024), we can also evaluate the evidence of a marginal effect for a given ![]() in

in ![]() relative to some threshold such as zero. Often we would like to say something like “there is a 0.98 probability that the effect of the explanatory variable

relative to some threshold such as zero. Often we would like to say something like “there is a 0.98 probability that the effect of the explanatory variable ![]() on the variability of the outcome

on the variability of the outcome ![]() is positive.” Notice that this type of statement cannot be made in the non-Bayesian context.

is positive.” Notice that this type of statement cannot be made in the non-Bayesian context.

Note also that all regression specifications are “semi-causal” in that by specifying (1.1) we are making an assertion that the collective evidence in ![]() explains a large part of the variability in

explains a large part of the variability in ![]() . The use of “semi” is very important here because a regression expression is not an assertion of causal inference since there are many other variables, measured or unmeasured, that could also cause variability in

. The use of “semi” is very important here because a regression expression is not an assertion of causal inference since there are many other variables, measured or unmeasured, that could also cause variability in ![]() . However, we specify the variables in

. However, we specify the variables in ![]() because we do think that they are explainers of the structure observed in

because we do think that they are explainers of the structure observed in ![]() , not because they are merely correlated. For instance, shoe size may be correlated with income (and it likely is for spurious reasons), but we would not include shoe size as a column of

, not because they are merely correlated. For instance, shoe size may be correlated with income (and it likely is for spurious reasons), but we would not include shoe size as a column of ![]() because we do not believe that it is an “explainer.”

because we do not believe that it is an “explainer.”

In Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024) we strongly emphasized using computer simulation to produce desired results with simple Bayesian calculations, even when the analytical calculation was available. Here we move to a world where computer simulation is actually required to get such results. We stated earlier that Markov chain Monte Carlo is essential for estimating nuanced Bayesian regression models. These are forms with nonlinear relationships, time series elements, hierarchies, interactions, and more. As such, much of the work here is dedicated to explaining how MCMC works and how to use it effectively with modern software. This emphasis is important because noncareful estimation with MCMC can go badly wrong. Unfortunately there is plenty of printed evidence of this. So, unlike estimating regular generalized linear models (GLMs) in the regression sense with iterative reweighted least squares (a multidimensional mode finder; see Gill and Torres [Reference Gill and Torres2019] for details), the process is not a simple application of canned software. One advantage to the type of software used for MCMC is that it causes the user to think deeply about the structure of the model being specified. However, it is important not to get lost in the mechanical aspects of estimating Bayesian models with MCMC and lose track of the original research objectives.

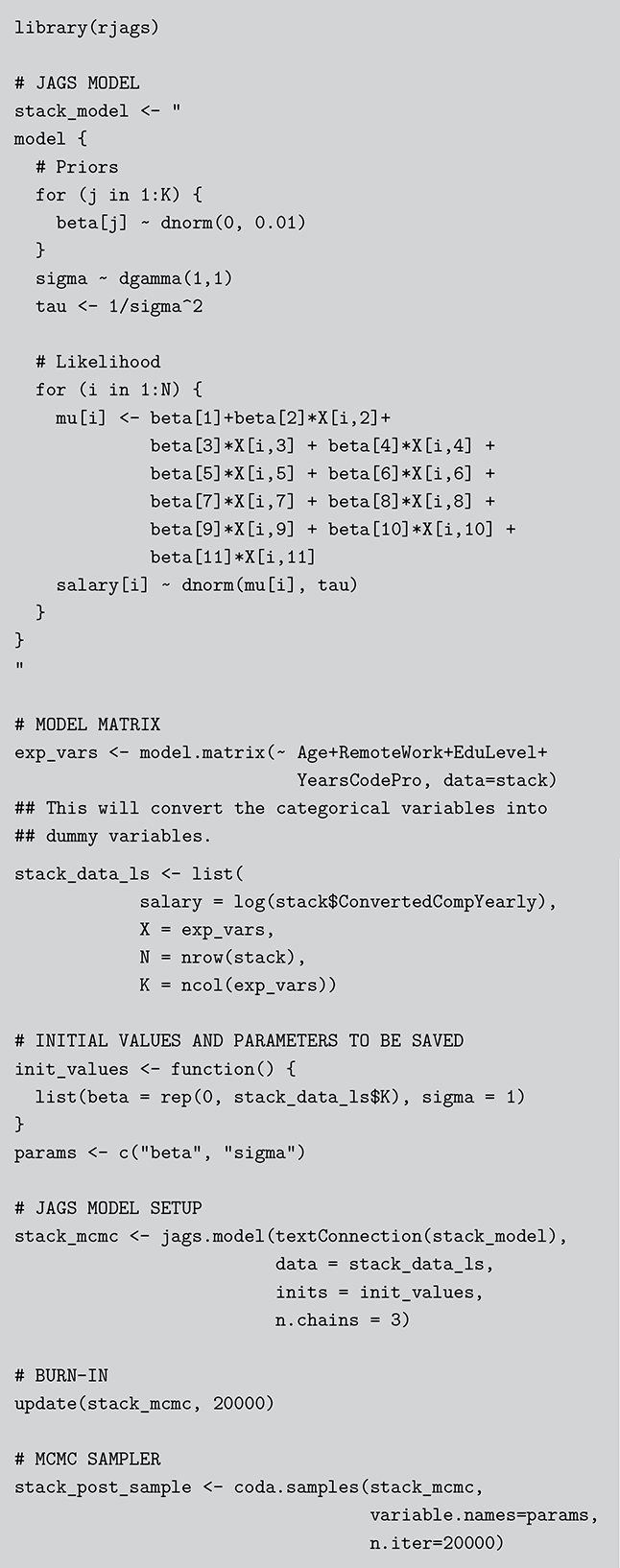

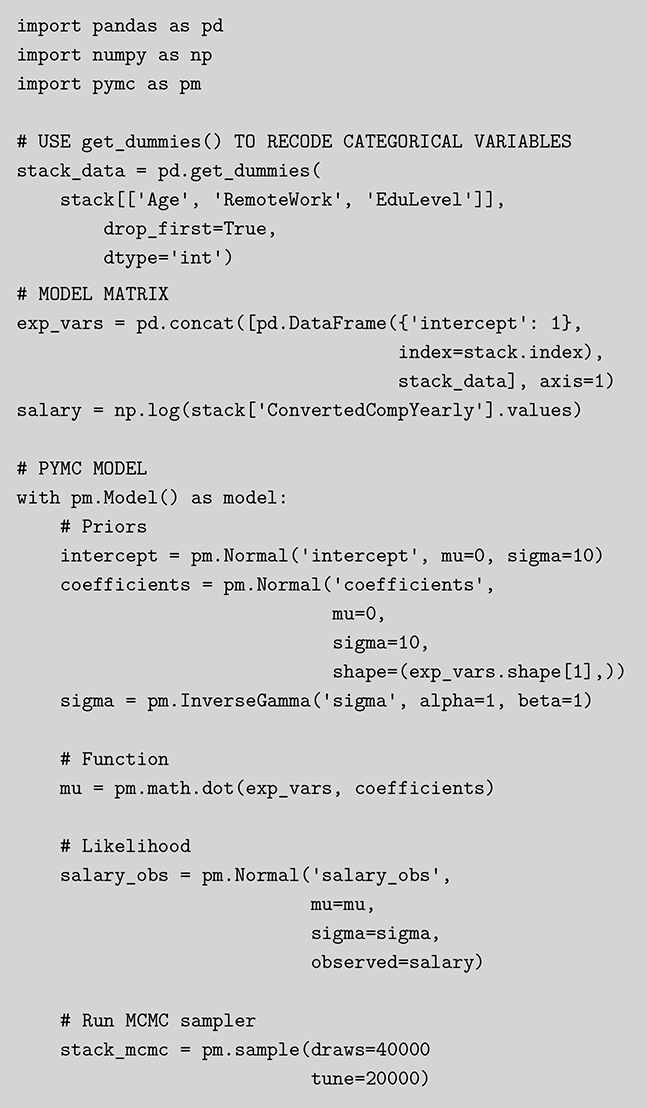

We focus here on applying MCMC with JAGS (“Just Another Gibbs Sampler” distributed freely by Martyn Plummer) called from R and PyMC (an open-source probabilistic programming library) in Python but there are other alternatives such as STAN, MultiBUGS, TensorFlow Probability, JAX, and more. In our view, JAGS and PyMC offer an optimal balance of flexibility, power, and ease of learning, with syntax closely aligned with mathematical notation, making them ideal for those new to Bayesian methods.” All code and data used throughout this Element are stored in a GitHub repository (https://github.com/jgill22/-Bayesian.Social.Science.Statistics2), and can also be conveniently executed online at a Code Ocean capsule (https://codeocean.com/capsule/0249394). We now turn to a review of Bayesian basics as a refresher.

2 A Review of Bayesian Principles and Inference

This section provides a very brief overview of Bayesian inference purely as a reminder. Readers are assumed to have seen similar discussions along the lines of Gill and Bao (Reference Gill and Bao2024). Fascinating historical accounts can also be found in works such as Dale (Reference Dale2012), McGrayne (Reference McGrayne2011), and Stigler (Reference Stigler1982, Reference Stigler1983). Important theoretical background is provided by Bernardo and Smith (Reference Bernardo and Smith2009), Diaconis and Freedman (Reference Diaconis and Freedman1986, Reference Diaconis and Freedman1998); Gill (Reference Gill2014), Jeffreys (Reference Jeffreys1998), Karni (Reference Karni2007), Robert (Reference Robert2007), and Watanabe (Reference Watanabe2018).

2.1 Basic Bayesian Theory

The Bayesian process of data analysis is characterized by three primary attributes: (1) a willingness to assign prior distributions to unknown parameters, (2) the use of Bayes’ rule to obtain a posterior distribution for unknown parameters and missing data conditioned on observable data, and (3) the description of inferences in probabilistic terms. The core philosophical foundation of Bayesian inference is the consideration of parameters as random quantities. A primary advantage of this approach is that there is no restriction to building complex models with multiple levels and many unknown parameters. Because model assumptions are much more overt in the Bayesian setup, readers can more accurately assess model quality.

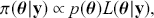

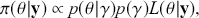

The primary goal in the Bayesian approach is to characterize the posterior density of each of the parameters of interest through the computation and the marginalization of the joint posterior distribution of the unknown parameter vector, given the observed data and the model specification, ![]() , for vectors

, for vectors ![]() and data

and data ![]() . Here the use of “

. Here the use of “ ![]() ” is a reminder that this is a posterior (post-data) probability distribution. The posterior distribution of the coefficients of interest is obtained by multiplying the prior by the likelihood function using proportionality:

” is a reminder that this is a posterior (post-data) probability distribution. The posterior distribution of the coefficients of interest is obtained by multiplying the prior by the likelihood function using proportionality:

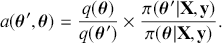

(2.1)

(2.1)

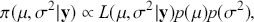

meaning that the posterior distribution is a compromise between prior information and data information. The fundamental principle and process of Bayesian inference starts with an unconditional prior distribution, ![]() , that reflects prior belief about the parameters of interest, and multiplies it with the likelihood function,

, that reflects prior belief about the parameters of interest, and multiplies it with the likelihood function, ![]() , bringing in the data information to produce the posterior distribution,

, bringing in the data information to produce the posterior distribution, ![]() . The posterior is now an updated distribution that reflects the most recent knowledge about some phenomenon of interest. Additionally, the result is a distribution, not a point estimate, so uncertainty is built into the results as distributional variability.

. The posterior is now an updated distribution that reflects the most recent knowledge about some phenomenon of interest. Additionally, the result is a distribution, not a point estimate, so uncertainty is built into the results as distributional variability.

This idea of compromise is critical to Bayesian thinking. When there is very reliable prior information and sketchy data information, then we should rely more on the specification of the prior. On the other hand, when there is a large amount of reliable data, then we should favor this type of information over any prior. A key feature of Bayesian inference is that this compromise is mathematically built into the process for any Bayesian result. So we get an important balance based on the amount of contribution from each of the two information sources. In addition, a posterior distribution can be treated as a prior distribution when another set of data is observed, and this process can be repeated as many times as new data arrive to obtain new posteriors that are conditional on all previous sets of observed data, as if they had arrived at the same time. This is a process called “Bayesian updating” or “Bayesian learning.”

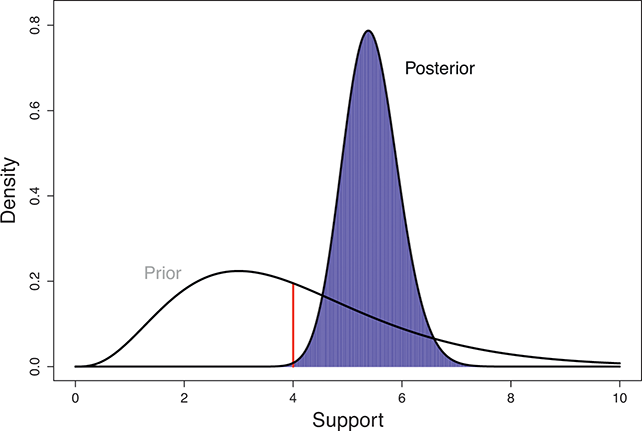

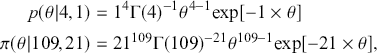

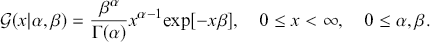

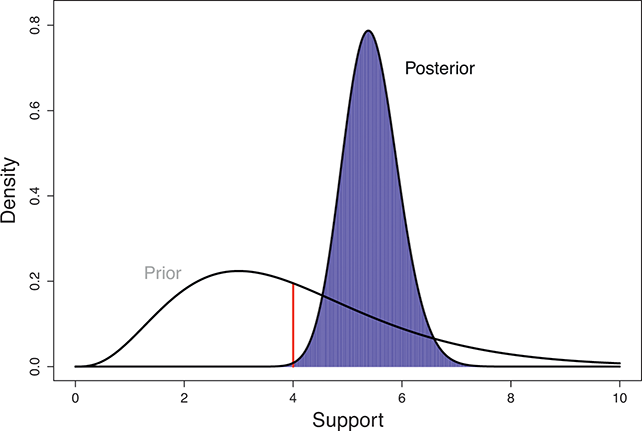

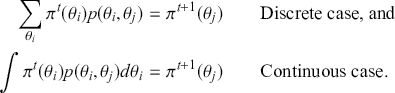

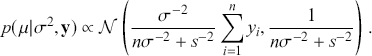

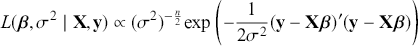

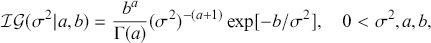

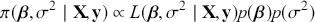

The Bayesian updating process is illustrated in Figure 1 where a gamma distribution prior is applied to a Poisson likelihood function with synthetic data (![]() ) generated by the R command rpois(20,5) or the Python command np.random.poisson(5,20), for a single parameter

) generated by the R command rpois(20,5) or the Python command np.random.poisson(5,20), for a single parameter ![]() . This is a conjugate setup, meaning that the form of the prior flows down to the posterior, albeit with different parameterization. Conjugacy is a special, and convenient, case of Bayesian modeling that has simple mathematical properties for determining the posterior distribution. In this case the prior and posterior parameterizations are

. This is a conjugate setup, meaning that the form of the prior flows down to the posterior, albeit with different parameterization. Conjugacy is a special, and convenient, case of Bayesian modeling that has simple mathematical properties for determining the posterior distribution. In this case the prior and posterior parameterizations are

using the rate version of the gamma PDF:

(2.2)

(2.2)

Suppose the threshold at 4 on the ![]() -axis is substantively important. In the prior distribution, 0.566 of the density is to the left of 4, whereas 0.005 of the posterior density is to the left of 4. So, even though there are only 20 data values, the likelihood function changes the prior substantially.

-axis is substantively important. In the prior distribution, 0.566 of the density is to the left of 4, whereas 0.005 of the posterior density is to the left of 4. So, even though there are only 20 data values, the likelihood function changes the prior substantially.

Figure 1 Poisson–Gamma update.

In many Bayesian models, priors themselves have prior parameters (hyperpriors), so there can be additional terms in the product but no substantial increase in complexity:

(2.3)

(2.3)

where ![]() is a higher-level parametric assignment with prior distribution

is a higher-level parametric assignment with prior distribution ![]() . Proportionality as used in (2.3) is typically employed to simplify the notation, since in the Bayesian setup,

. Proportionality as used in (2.3) is typically employed to simplify the notation, since in the Bayesian setup, ![]() is observed and therefore is assumed fixed and independent of

is observed and therefore is assumed fixed and independent of ![]() . In addition, Bayesian model specification can be naturally hierarchical, since parameters and hyperparameters can be conduits to additional specifications at group levels.

. In addition, Bayesian model specification can be naturally hierarchical, since parameters and hyperparameters can be conduits to additional specifications at group levels.

2.2 Interval Estimation

Highest posterior density (HPD) regions are the Bayesian equivalent of confidence intervals in which the region describes the area over the coefficient’s support with ![]() % of the density with the highest probability. Like frequentist confidence intervals, an HPD region that does not contain zero implies that the coefficient estimate is deemed to be reliable, but instead of being

% of the density with the highest probability. Like frequentist confidence intervals, an HPD region that does not contain zero implies that the coefficient estimate is deemed to be reliable, but instead of being ![]() % “confident” that the interval covers the true parameter value over multiple replications of the exact same experiment, an HPD interval provides a

% “confident” that the interval covers the true parameter value over multiple replications of the exact same experiment, an HPD interval provides a ![]() % probability that the true parameter is in the interval. Sometimes HPD regions are relatively wide, indicating that the coefficient varies considerably and is less likely to be reliable, and sometimes these regions are quite narrow, indicating greater certainty about the central location of the parameter. Highest posterior density regions do not have to be contiguous, and contiguous HPDs (no breaks on the

% probability that the true parameter is in the interval. Sometimes HPD regions are relatively wide, indicating that the coefficient varies considerably and is less likely to be reliable, and sometimes these regions are quite narrow, indicating greater certainty about the central location of the parameter. Highest posterior density regions do not have to be contiguous, and contiguous HPDs (no breaks on the ![]() -axis) are usually called credible intervals.

-axis) are usually called credible intervals.

2.3 The Bayes Factor

Formal hypothesis testing can also be easily performed in Bayesian inference. Start with ![]() and

and ![]() representing competing hypotheses about the location of some

representing competing hypotheses about the location of some ![]() parameter to be estimated. These two statements about

parameter to be estimated. These two statements about ![]() form a partition of the sample space, meaning that

form a partition of the sample space, meaning that ![]() , where “

, where “ ![]() ” denotes the empty or null set. Now prior probabilities are assigned to each of the two outcomes:

” denotes the empty or null set. Now prior probabilities are assigned to each of the two outcomes: ![]() and

and ![]() . Since the priors are different (but the form of the likelihood function is the same), there are two competing posterior distributions:

. Since the priors are different (but the form of the likelihood function is the same), there are two competing posterior distributions: ![]() and

and ![]() . We can now define the prior odds,

. We can now define the prior odds, ![]() , and the posterior odds,

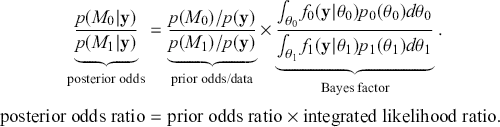

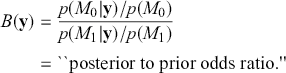

, and the posterior odds, ![]() . This leads to a prior-to-posterior ratio of

. This leads to a prior-to-posterior ratio of ![]() , which is called the Bayes factor, interpreted as odds favoring

, which is called the Bayes factor, interpreted as odds favoring ![]() versus

versus ![]() given the observed data, and it leads naturally to Bayesian hypothesis testing. Another interpretation is that the Bayes factor is the ratio of improvement in odds by accounting for the data.

given the observed data, and it leads naturally to Bayesian hypothesis testing. Another interpretation is that the Bayes factor is the ratio of improvement in odds by accounting for the data.

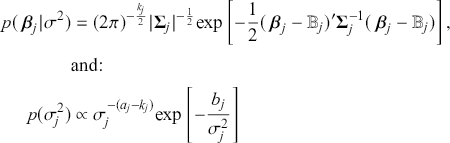

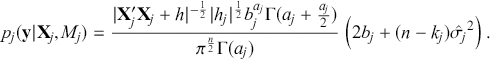

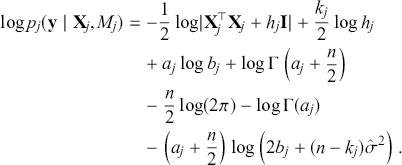

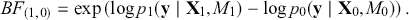

More formally, start with the two competing models, ![]() and

and ![]() . Specify corresponding parameter priors:

. Specify corresponding parameter priors: ![]() ,

, ![]() , and model priors:

, and model priors: ![]() and

and ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() . Therefore:

. Therefore:

(2.4)

(2.4)

Now rearranging and canceling out ![]() gives:

gives:

(2.5)

(2.5)

The Bayes factor here is analogous to a likelihood ratio test, except that it includes prior information. Also, the tested hypotheses do not need to be “nested” as does the likelihood ratio (one model is a subset of the other). Regretfully, though, there is no distributional test for the Bayes factor. Since a result near one is obviously inconclusive, what we want is a number that is decisively large, like 10 or greater, or decisively small, like 0.1 or less. There are some published thresholds contained in Jeffreys (Reference Jeffreys1998) and Kass and Raftery (Reference Kass and Raftery1995), but they are completely arbitrary.

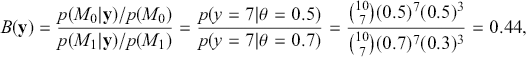

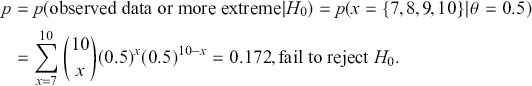

It is important to know that the Bayes factor as evidence is completely different than using p-values (or similar devices) in non-Bayesian inference. For example, consider testing whether a coin is fair or biased at a specific value: ![]() versus

versus ![]() . Assign equal priors:

. Assign equal priors: ![]() , so that the prior odds ratio is just one, which is commonly done. We flip the coin 10 times and get 7 heads, which is exactly at the alternative hypothesis. The Bayes factor between “model 0 supported” and “minimal evidence against model 0” is calculated by

, so that the prior odds ratio is just one, which is commonly done. We flip the coin 10 times and get 7 heads, which is exactly at the alternative hypothesis. The Bayes factor between “model 0 supported” and “minimal evidence against model 0” is calculated by

which provides no strong evidence for either hypothesis. Now calculate the p-value in the standard way:

Notice that the manner in which we make these conclusions is very different. The surprising result is that we cannot reject ![]() with the p-value as evidence even though the data landed right on the alternative of

with the p-value as evidence even though the data landed right on the alternative of ![]() . This is because the two hypotheses are relatively close and p-values are poor tools for asserting scientific evidence. Bayes factors are very compelling because they provide a direct way to compare competing hypotheses that include both prior and data information, but there are some shortcomings. First, they are known to be sensitive to the choice of priors, although an overwhelming number of authors set the prior probabilities to 0.5 each. Second, there is no ability to have directional hypotheses in the conventional sense. However, direction can be built into the hypothesis structure by specifying regions such as

. This is because the two hypotheses are relatively close and p-values are poor tools for asserting scientific evidence. Bayes factors are very compelling because they provide a direct way to compare competing hypotheses that include both prior and data information, but there are some shortcomings. First, they are known to be sensitive to the choice of priors, although an overwhelming number of authors set the prior probabilities to 0.5 each. Second, there is no ability to have directional hypotheses in the conventional sense. However, direction can be built into the hypothesis structure by specifying regions such as ![]() versus

versus ![]() . Finally, improper priors (those that do not sum or integrate to a finite value) do not work because the infinity values do not cancel out in the ratio, although there are several rather tortured work-arounds; see Gill (Reference Gill2014), chapter 6.

. Finally, improper priors (those that do not sum or integrate to a finite value) do not work because the infinity values do not cancel out in the ratio, although there are several rather tortured work-arounds; see Gill (Reference Gill2014), chapter 6.

2.4 Using Simulation

The challenge before us now is to use these Bayesian principles to develop regression-style specification of interest to social scientists. However, many of the important and popular forms require Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) so that the computer performs the difficult or impossible tasks for us in estimating these forms and getting marginal posterior distributions for each of the unknown parameters. One major impediment to wide usage of Bayesian regression specifications is the hurdle of learning MCMC. We break it down into three stages here: (1) understanding the general principle of Monte Carlo methods for making the computer do a lot of repetitive tasks, (2) defining what a Markov chain does mathematically in an accessible way, and (3) combining these two principles to produce a powerful tool that lets Bayesians model nearly anything. Our objective in the next three sections is to demystify MCMC tools and make them widely usable to a large class of researchers. We do this by introducing Monte Carlo simulation in the next section, then in Section 4 we provide a gentle introduction to the mathematics of Markov chains and then combine these principles to produce the powerful MCMC estimation engine in Section 5.

3 Monte Carlo Tools for Computational Power

This section introduces Monte Carlo Methods in statistics. This is a very important component to modern practice that exploits a computer’s ability to do a large number of mundane tasks. Such simulation work in applied and research statistics replaces analytical work with repetitious, low-level effort by the computer. So if a distribution is difficult or impossible to manipulate analytically, then it is often possible to create a set of simulated values that share the same distributional properties, and describe the posterior by using empirical summaries of these simulated values. This process was termed Monte Carlo simulation by Von Neumann and Ulam in the 1950s (although some accounts attribute the naming to Metropolis too) because it uses randomly generated values to perform calculations of interest, reminiscent of expected value calculations in gambling.

3.1 Random Number Generation with Uses

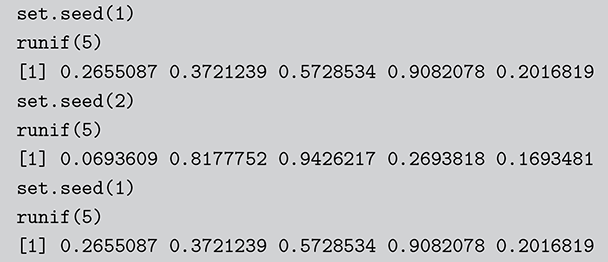

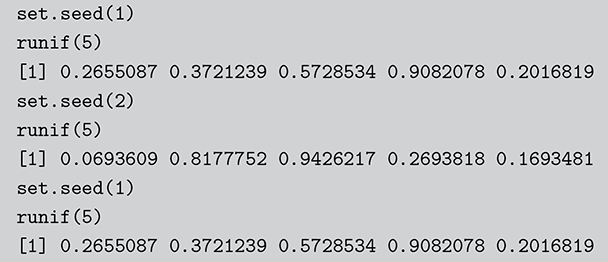

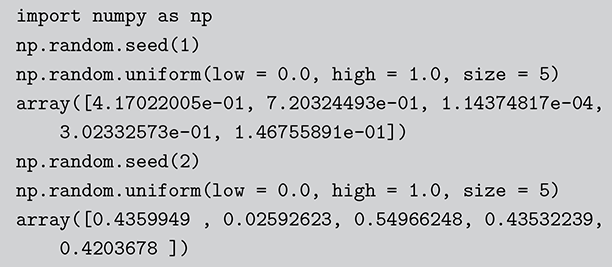

Surprisingly, all random number generation starts with producing ![]() continuous uniform random variables within computer algorithms. Then there is a large set of transformations that provide any distributional form of interest. These uniform random numbers are actually not random at all. They are pseudo-random numbers that are produced deterministically by the computer with a defined period before repeating the sequence identically. Fortunately, due to work mostly done in the 1980s, the length of this period is so large that we do not have to care. We can generate different sequences by setting a “seed” to start a new process. This is illustrated in the following code boxes in R and Python where we set this random seed before generating five

continuous uniform random variables within computer algorithms. Then there is a large set of transformations that provide any distributional form of interest. These uniform random numbers are actually not random at all. They are pseudo-random numbers that are produced deterministically by the computer with a defined period before repeating the sequence identically. Fortunately, due to work mostly done in the 1980s, the length of this period is so large that we do not have to care. We can generate different sequences by setting a “seed” to start a new process. This is illustrated in the following code boxes in R and Python where we set this random seed before generating five ![]() random numbers, change the seed to produce a different set, and then change the seed back to get the original set again.

random numbers, change the seed to produce a different set, and then change the seed back to get the original set again.

Code 1.01

set.seed(1)

runif(5)

[1] 0.2655087 0.3721239 0.5728534 0.9082078 0.2016819

set.seed(2)

runif(5)

[1] 0.0693609 0.8177752 0.9426217 0.2693818 0.1693481

set.seed(1)

runif(5)

[1] 0.2655087 0.3721239 0.5728534 0.9082078 0.2016819

Code 1.02

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(1)

np.random.uniform(low = 0.0, high = 1.0, size = 5)

array([4.17022005e-01, 7.20324493e-01, 1.14374817e-04,

3.02332573e-01, 1.46755891e-01])

np.random.seed(2)

np.random.uniform(low = 0.0, high = 1.0, size = 5)

array([0.4359949 , 0.02592623, 0.54966248, 0.43532239,

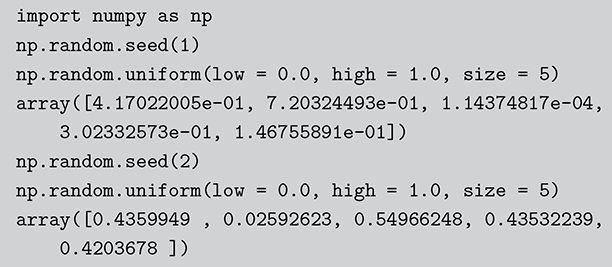

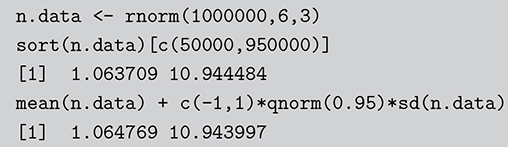

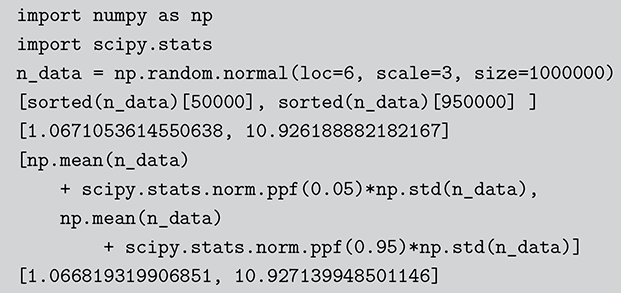

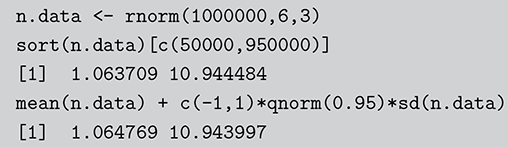

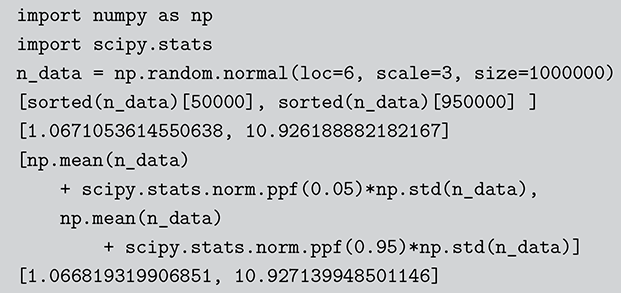

0.4203678 ]) The Monte Carlo principle is actually much more general than this, even though generating random numbers according to some distribution is very important. Suppose we could generate random numbers in a way that does work for us, and often you can get the right answer faster with simulation than by analytics. For instance, what is the 90 percent confidence interval for a random variable distributed ![]() ? This is obviously an easy analytical calculation but we can also do this quickly with two lines of code as shown in what follows (one line if we want to be clever). We simply generate 1,000,000 values from the desired normal distribution, sort them, and find the desired interval end-points empirically as if these were actual data. The large number of generated values (it can be larger) assures us a high level of accuracy.

? This is obviously an easy analytical calculation but we can also do this quickly with two lines of code as shown in what follows (one line if we want to be clever). We simply generate 1,000,000 values from the desired normal distribution, sort them, and find the desired interval end-points empirically as if these were actual data. The large number of generated values (it can be larger) assures us a high level of accuracy.

Code 1.03

n.data <- rnorm(1000000,6,3)

sort(n.data)[c(50000,950000)]

[1] 1.063709 10.944484

mean(n.data) + c(-1,1)*qnorm(0.95)*sd(n.data)

[1] 1.064769 10.943997

Code 1.04

import numpy as np

import scipy.stats

n_data = np.random.normal(loc=6, scale=3, size=1000000)

[sorted(n_data)[50000], sorted(n_data)[950000] ]

[1.0671053614550638, 10.926188882182167]

[np.mean(n_data)

+ scipy.stats.norm.ppf(0.05)*np.std(n_data),

np.mean(n_data)

+ scipy.stats.norm.ppf(0.95)*np.std(n_data)]

[1.066819319906851, 10.927139948501146]Here R and Python have slightly different answers because the default random number generators are different. Notice also that the two methods also have slightly different answers and this is due to rounding in the different calculations. There is also an error term introduced by using Monte Carlo methods instead of an analytical calculation: simulation error. The good news, however, is that this type of error decreases at a rate of ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of simulated values used. This means that the user controls the simulation error and the only cost is additional user time on increasingly fast computers.

is the number of simulated values used. This means that the user controls the simulation error and the only cost is additional user time on increasingly fast computers.

3.2 Basic Monte Carlo Integration

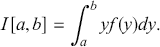

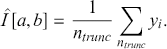

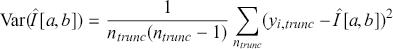

Another use of Monte Carlo simulation is doing integral calculus that is hard or impossible analytically. Suppose ![]() is a function that is difficult to integrate over a specific range but we can draw values from this form. For example, the expected value of

is a function that is difficult to integrate over a specific range but we can draw values from this form. For example, the expected value of ![]() distributed

distributed ![]() restricted to being between

restricted to being between ![]() and

and ![]() is given by the integral:

is given by the integral:

(3.1)

(3.1)

To get this integral by simulation, first generate a large number (![]() ) of simulated values of

) of simulated values of ![]() from

from ![]() . Then we discard any values below

. Then we discard any values below ![]() and above

and above ![]() to get the sample

to get the sample ![]() (e.g. left after truncation). The estimate of the integral is merely

(e.g. left after truncation). The estimate of the integral is merely

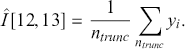

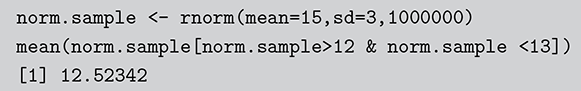

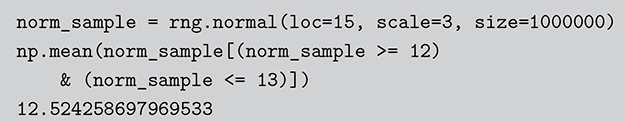

(3.2)

(3.2)

So we substitute a mean of the empirical sample for the analytical integral calculation. From the Strong Law of Large Numbers, the calculation of ![]() converges with probability one to the actual true answer. As in the preceding example the simulation error of

converges with probability one to the actual true answer. As in the preceding example the simulation error of ![]() goes to zero proportional to

goes to zero proportional to ![]() . In this case the expression of the variance of the simulation estimate is

. In this case the expression of the variance of the simulation estimate is

(3.3)

(3.3)

Note that the researcher fully controls the simulation size, ![]() , and therefore the simulation accuracy of the estimate.

, and therefore the simulation accuracy of the estimate.

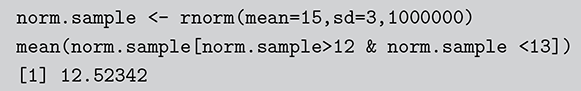

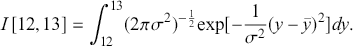

As a specific example, suppose we want to integrate a ![]() over the range

over the range ![]() :

:

This is easily calculated by the following:

The calculation is given in the following R and Python code boxes.

Code 1.05

norm.sample <- rnorm(mean=15,sd=3,1000000)

mean(norm.sample[norm.sample>12 & norm.sample <13])

[1] 12.52342

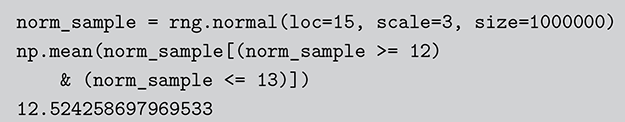

Code 1.06

norm_sample = rng.normal(loc=15, scale=3, size=1000000)

np.mean(norm_sample[(norm_sample >= 12)

& (norm_sample <= 13)])

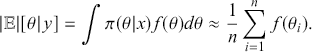

12.524258697969533 In a Bayesian context using 3.1 we can replace arbitrary ![]() with a posterior statement

with a posterior statement ![]() and

and ![]() in the preceding with

in the preceding with ![]() . So

. So ![]() is the posterior expectation of

is the posterior expectation of ![]() , given by:

, given by:

(3.4)

(3.4)

We can see here that if it is possible to generate values from ![]() , then we can calculate this expected value or any other related statistic. This is actually the last step of the MCMC process, which we will see in Section 4.2 on Markov Chain Theory.

, then we can calculate this expected value or any other related statistic. This is actually the last step of the MCMC process, which we will see in Section 4.2 on Markov Chain Theory.

3.3 Rejection Sampling

Suppose that we lack the ability to produce samples from some known distribution but we still have a difficult analytical problem that suggests Monte Carlo simulation. In some circumstances we can then use rejection sampling to integrate as done earlier. Rejection sampling is actually used in two primary contexts: obtaining dimensional integral quantities, and generating random variables. In addition, rejection sampling can be particularly useful in determining the normalizing factor for nonnormalized posterior distributions. The very general steps are as follows:

find some other distribution that is convenient to sample from, where it must enclose the target distribution.

compare generated values with the target distribution and decide which values to keep and which to reject.

the integral of interest is the normalized ratio of these values.

The easier case is when the target function has bounded support: a defined, noninfinite support of some PDF or other function. Consider a function of interest ![]() such that it can be evaluated for any value over the support of

such that it can be evaluated for any value over the support of ![]() :

: ![]() . We want to put a “box” around the function and we have the two sides of the rectangle from

. We want to put a “box” around the function and we have the two sides of the rectangle from ![]() and

and ![]() . Since our interest is almost always centered on probability functions, the bottom of the box is the x-axis at zero. To determine the top of the box we can use various mathematical tools like analytical root finding, numerical techniques such as gridding, Newton–Raphson, EM, etc. to find

. Since our interest is almost always centered on probability functions, the bottom of the box is the x-axis at zero. To determine the top of the box we can use various mathematical tools like analytical root finding, numerical techniques such as gridding, Newton–Raphson, EM, etc. to find ![]() . So we have defined a rectangle that bounds all possible values for the pair

. So we have defined a rectangle that bounds all possible values for the pair ![]() . Other geometric forms work too. The objective is now to sample the two-dimensional random variable in this rectangle by independently sampling uniformly over

. Other geometric forms work too. The objective is now to sample the two-dimensional random variable in this rectangle by independently sampling uniformly over ![]() and

and ![]() then pairing to produce a point in 2-space. Finally all we have to do is count the proportion of points that fall inside the region of interest. The value of the integral, which is the area under the curve, is the ratio of the generated points under the curve compared to the total number of points scaled by the known size of the box:

then pairing to produce a point in 2-space. Finally all we have to do is count the proportion of points that fall inside the region of interest. The value of the integral, which is the area under the curve, is the ratio of the generated points under the curve compared to the total number of points scaled by the known size of the box:

As with all Monte Carlo simulations, the error rate goes to zero proportional to ![]() .

.

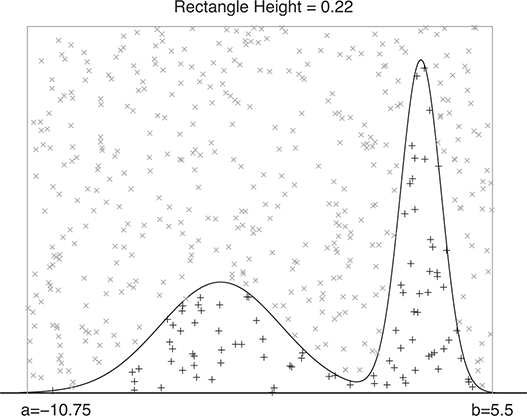

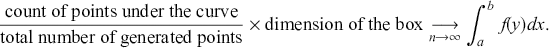

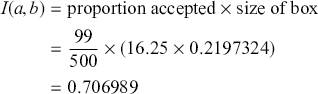

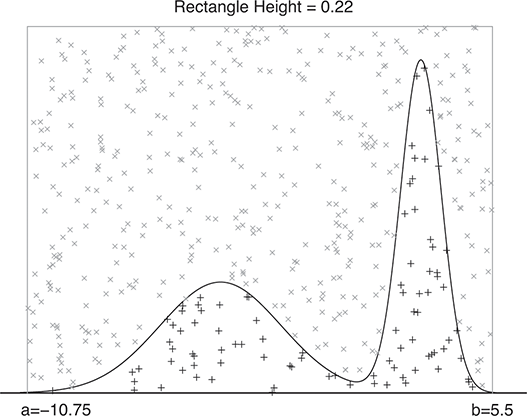

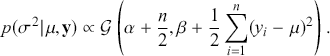

A curve of interest is plotted in Figure 2 with 500 points generated uniform randomly inside the rectangle. Normally many more points are generated to ensure good Monte Carlo accuracy (low error), but the number is limited here for graphical purposes. There are 99 accepted points (marked with “+”) under the curve, and 401 rejected points (marked with “x”) above the curve. and 401 rejected red points above the curve. The rectangle has sides of length ![]() by construction. So the area under the curve (the integral) is calculated by:

by construction. So the area under the curve (the integral) is calculated by:

This was straightforward because we were able to easily put a box around the function of interest. The key feature of this example is that while we could not integrate the function, we were able to insert values of ![]() and get values of

and get values of ![]() .

.

Figure 2 Example of Rejection Sampling

A more difficult version of this problem is when the target function, ![]() , has unbounded support, like say a gamma distribution with support

, has unbounded support, like say a gamma distribution with support ![]() . In this case we need to identify a majorizing function that fully envelopes the target in a way that a rectangle cannot, and can still have values drawn from. The rectangle was convenient because the size is simply height times width. Typically a chosen majorizing function,

. In this case we need to identify a majorizing function that fully envelopes the target in a way that a rectangle cannot, and can still have values drawn from. The rectangle was convenient because the size is simply height times width. Typically a chosen majorizing function, ![]() , is a PDF chosen such that

, is a PDF chosen such that ![]() for the full support of

for the full support of ![]() . To make sure that this property holds, it is always necessary to multiply the candidate generating function by a constant:

. To make sure that this property holds, it is always necessary to multiply the candidate generating function by a constant: ![]() . The steps are slightly different since we do not have the same height on the y-axis over the support. The steps are as follows:

. The steps are slightly different since we do not have the same height on the y-axis over the support. The steps are as follows:

uniformly randomly generate many points on the support of

(x-axis),

(x-axis),  .

.for all

, points calculate

, points calculate  .

.for all

, generate a unique

, generate a unique  value,

value,  .

.accept points if

.

.otherwise reject.

The setup is critical here. If the majorizing function is highly dissimilar than the target function, then a lot of values will be rejected and the algorithm will be inefficient. Rejection sampling is actually a fundamental part of one of the two important MCMC procedures.

Now we can state the Fundamental Principle of Monte Carlo Simulation. If we have many draws from a distribution of interest (or other functional forms), then we can use these draws to calculate any value of interest, with a known error rate. A key word in that definition is “any,” meaning that we can empirically calculate means, variances, intervals, quantiles, higher-order moments, and more. Thus, this process replaces analytical work for hard problems but does not deter us from getting values or summaries of interest.

Monte Carlo analysis has been around since the infancy of programmable computers in the early 1950s. Physicists such as Ulam, Von Neumann, Metropolis, and Teller were exploring subatomic properties developing nuclear weapons, but in some cases could not design the relevant physical experiments. So they turned to this new device called the computer and simulated the properties of interest. One important paper that is still cited and relevant to us in Section 5, is Metropolis et al. (Reference Metropolis, Rosenbluth, Rosenbluth, Teller and Teller1953). In this case the authors were interested in the paths of particles inside a box when the box is being squeezed down to a singularity.

General statistical interest in Monte Carlo methods in statistics started roughly in the 1980s when researchers were first having personal computers on their office desk. As these computers became more common and more powerful, Monte Carlo simulation became much more common because it made difficult calculations easier. If one were to look into the office of a research statistician in the 1970s, she would almost certainly be deriving properties analytically. Today, that same person is doing that same work on the same sorts of problems but mainly with various simulation tools. We now turn to the theoretical basics of Markov chains.

4 A Simple Introduction to the Mathematics of Markov Chains

4.1 A Modeling Exercise

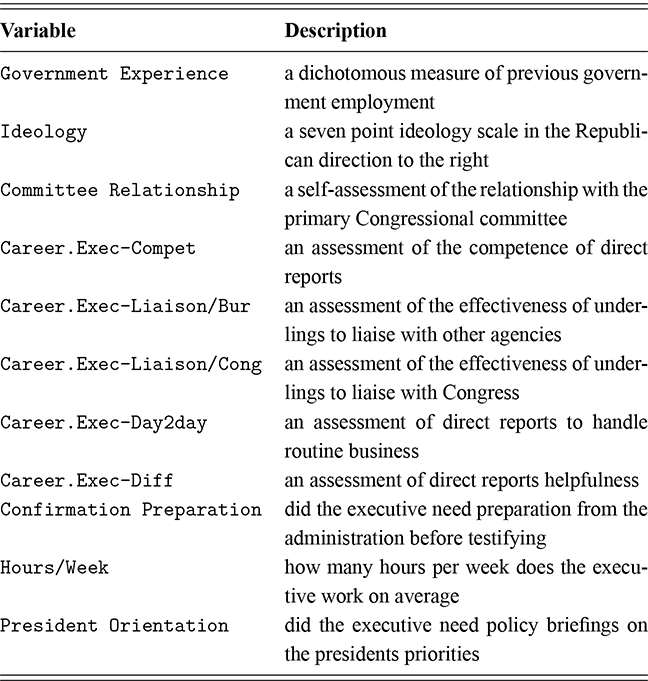

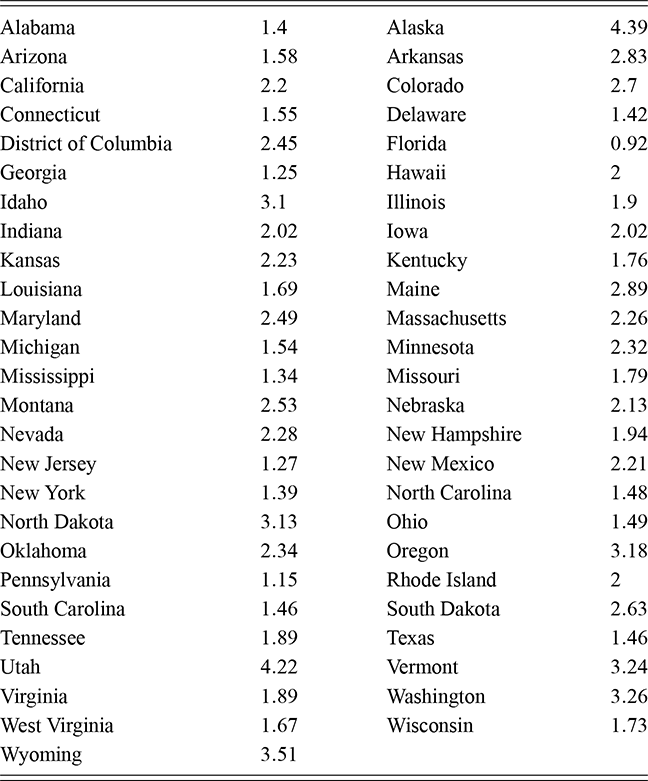

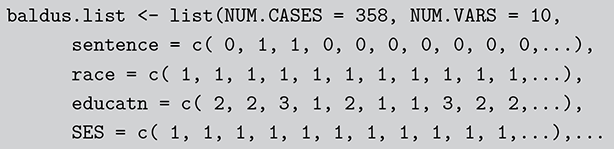

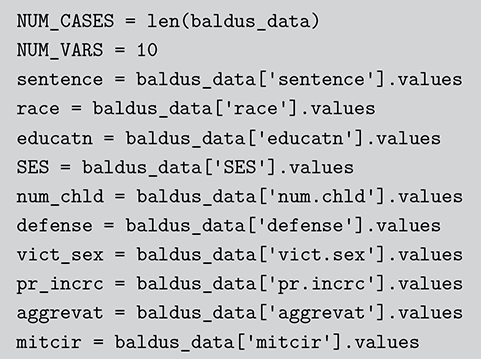

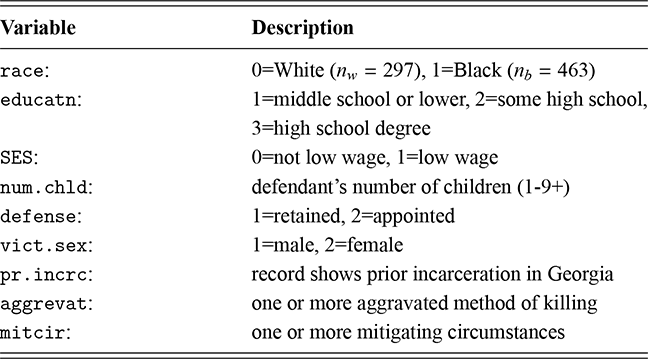

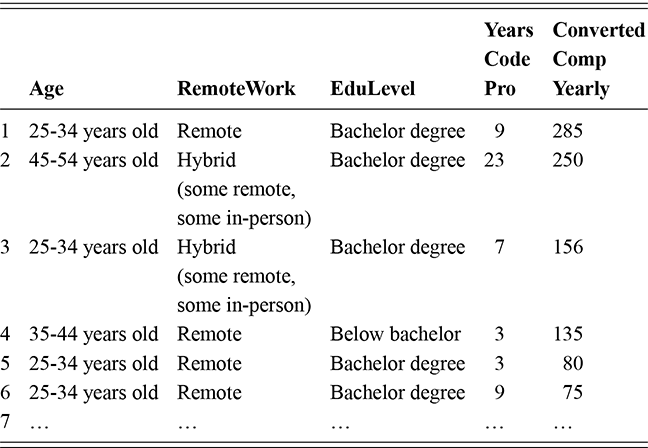

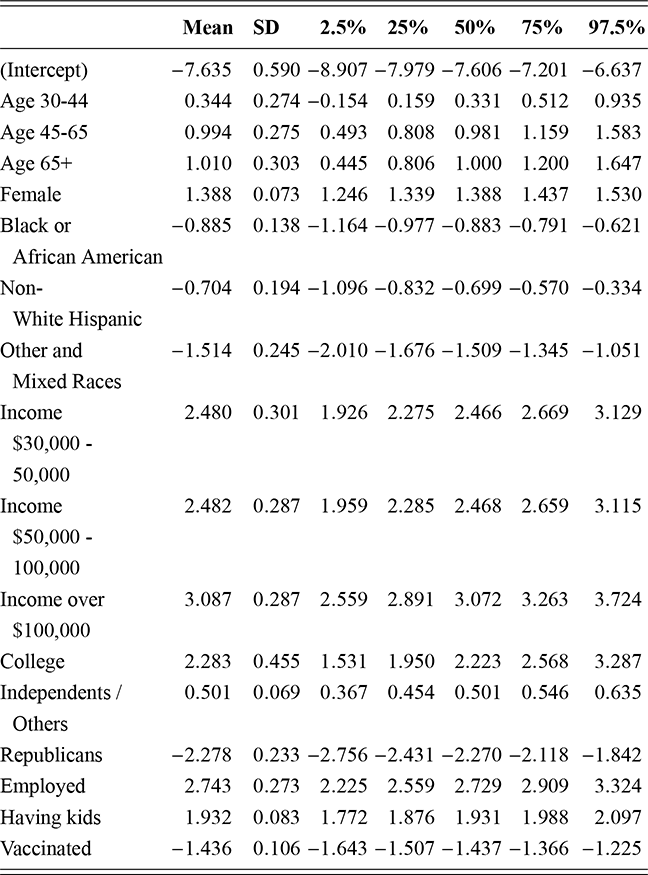

As a motivating example for our efforts to learn MCMC for Bayesian estimation, consider a dataset used in Gill and Casella (2009) looking at a puzzle in bureaucratic politics. These data contain every federal political appointee to full-time positions requiring Senate confirmation from November 1964 through December 1984 (collected by Mackenzie and Light, ICPSR Study Number 8458, Spring 1987). Their survey queries various aspects of the Senate confirmation process, acclamation to running an agency or program, and relationships with other functions of government. But these researchers needed to preserve anonymity of the interviewed so they embargoed some variables and randomly sampled 1,500 down to 512. This provides some methodological challenges, but we will ignore them here. So every respondent in the data ran a US federal agency or some major component of it. The puzzle is that even though all of them have to nominated by the president, underwent grilling on Capitol Hill, moved to an expensive real estate market, hired a lawyer or advisor for the process, often left a high-paying corporate position, and uprooted a family, ![]() they stayed in the position on average for only about two years. Fortunately, there is a convenient outcome variable that may explain this phenomenon: stress, which can be considered as a surrogate measure for self-perceived effectiveness and job-satisfaction recorded as a five-point scale from “not stressful at all” to “very stressful.” The emphasis in this Element is on Bayesian regression models, so consider the explanatory variables in Table 1.

they stayed in the position on average for only about two years. Fortunately, there is a convenient outcome variable that may explain this phenomenon: stress, which can be considered as a surrogate measure for self-perceived effectiveness and job-satisfaction recorded as a five-point scale from “not stressful at all” to “very stressful.” The emphasis in this Element is on Bayesian regression models, so consider the explanatory variables in Table 1.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Government Experience | a dichotomous measure of previous government employment |

| Ideology | a seven point ideology scale in the Republican direction to the right |

| Committee Relationship | a self-assessment of the relationship with the primary Congressional committee |

| Career.Exec-Compet | an assessment of the competence of direct reports |

| Career.Exec-Liaison/Bur | an assessment of the effectiveness of underlings to liaise with other agencies |

| Career.Exec-Liaison/Cong | an assessment of the effectiveness of underlings to liaise with Congress |

| Career.Exec-Day2day | an assessment of direct reports to handle routine business |

| Career.Exec-Diff | an assessment of direct reports helpfulness |

| Confirmation Preparation | did the executive need preparation from the administration before testifying |

| Hours/Week | how many hours per week does the executive work on average |

| President Orientation | did the executive need policy briefings on the presidents priorities |

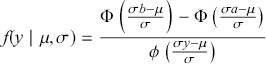

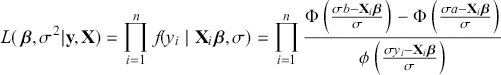

This is a rich dataset and there are many other variables to explore. Given that the chosen outcome variable is an ordinal scale, an “ordered choice model” makes sense. This name actually comes from economics, but applies to any regression outcome that is ordinal (i.e. not necessarily a “choice”). The model starts with assuming that there is a latent dimension underlying these observed ordinal categories. In a perfect world we could put some sort of a meter up to people’s heads and measure the exact level of stress in that person. In reality we have to live with some ordinal survey response, with five categories in this case. However, the model specification first assumes that we have the exact level measurement on the utility metric and then assumes that there are categories imposed on this latent scale from the survey wording. The setup looks like this:

Now the vector of (unseen) utilities across individuals in the sample, ![]() , is determined by a linear additive specification of explanatory variables:

, is determined by a linear additive specification of explanatory variables: ![]() as if we could see the latent dimension for real, where

as if we could see the latent dimension for real, where ![]() does not depend on the

does not depend on the ![]() cutpoints between categories, and the residuals have some distribution that we have not assigned yet,

cutpoints between categories, and the residuals have some distribution that we have not assigned yet, ![]() , stated in cumulative distribution terms (CDF). These cutpoints between categories also need to be estimated on this latent scale and are sometimes called “fences” or “thresholds.” The key to understanding this model is to see that it initially assumes we know something that we cannot know: the true latent dimension. Another key point to note is that the model is initially given all in cumulative terms. This means that the probability that individual

, stated in cumulative distribution terms (CDF). These cutpoints between categories also need to be estimated on this latent scale and are sometimes called “fences” or “thresholds.” The key to understanding this model is to see that it initially assumes we know something that we cannot know: the true latent dimension. Another key point to note is that the model is initially given all in cumulative terms. This means that the probability that individual ![]() in the sample is observed to be in category

in the sample is observed to be in category ![]() or lower is:

or lower is:

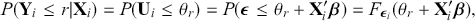

(4.1)

(4.1)

which is differently signed than the popular MASS package in R, which states ![]() from the help page. It is very irritating that the sign in front of

from the help page. It is very irritating that the sign in front of ![]() varies by author and software, but we just have to live with that. One convenient way to figure out which sign is being used is to check the effect of an “obvious” explanatory variable. So, for example, in voting models we know that people get more conservative as they get older and richer. This is not a perfect recommendation but it helps to make up for technical omissions by some authors. Now specifying a logistic distributional assumption on the residuals produces a logistic cumulative specification for the whole sample:

varies by author and software, but we just have to live with that. One convenient way to figure out which sign is being used is to check the effect of an “obvious” explanatory variable. So, for example, in voting models we know that people get more conservative as they get older and richer. This is not a perfect recommendation but it helps to make up for technical omissions by some authors. Now specifying a logistic distributional assumption on the residuals produces a logistic cumulative specification for the whole sample:

(4.2)

(4.2)

However, a probit (cumulative normal) distribution is another popular choice.

Of course, this work is about Bayesian specifications for social science models so we need to specify prior distributions for the ![]() parameters. However, this differs from simpler regression models in that we also need to specify prior distributions for the

parameters. However, this differs from simpler regression models in that we also need to specify prior distributions for the ![]() cutpoint parameter as well. So, let’s specify the most simple possible and nearly conjugate forms as possible to keep this extended example as direct as possible:

cutpoint parameter as well. So, let’s specify the most simple possible and nearly conjugate forms as possible to keep this extended example as direct as possible:

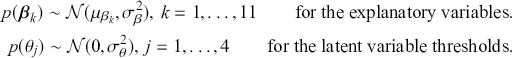

Here is the problem; all this produces a posterior distribution according to

(4.3)

(4.3)

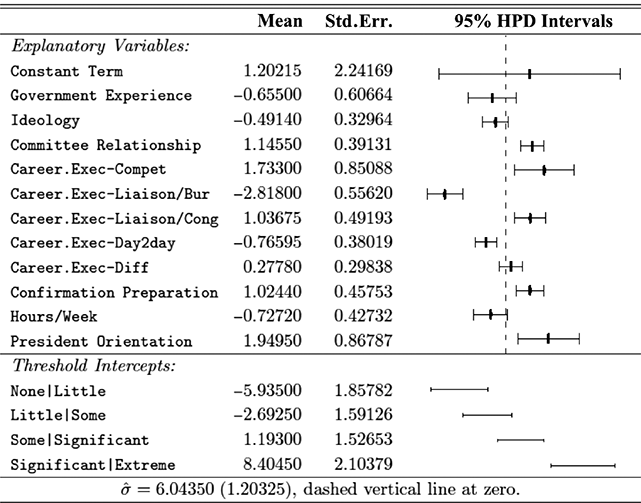

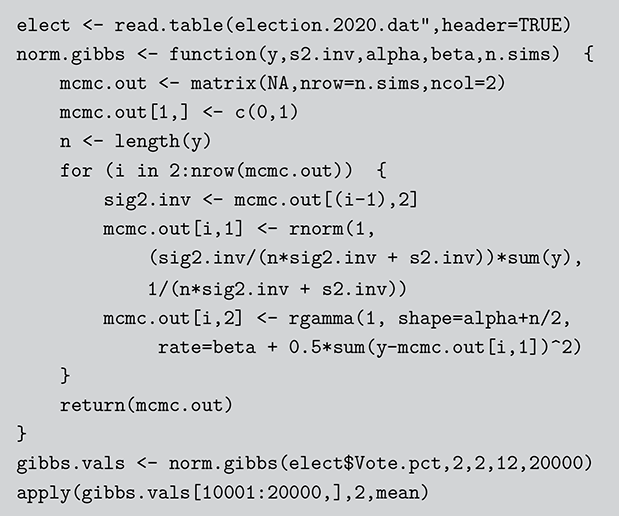

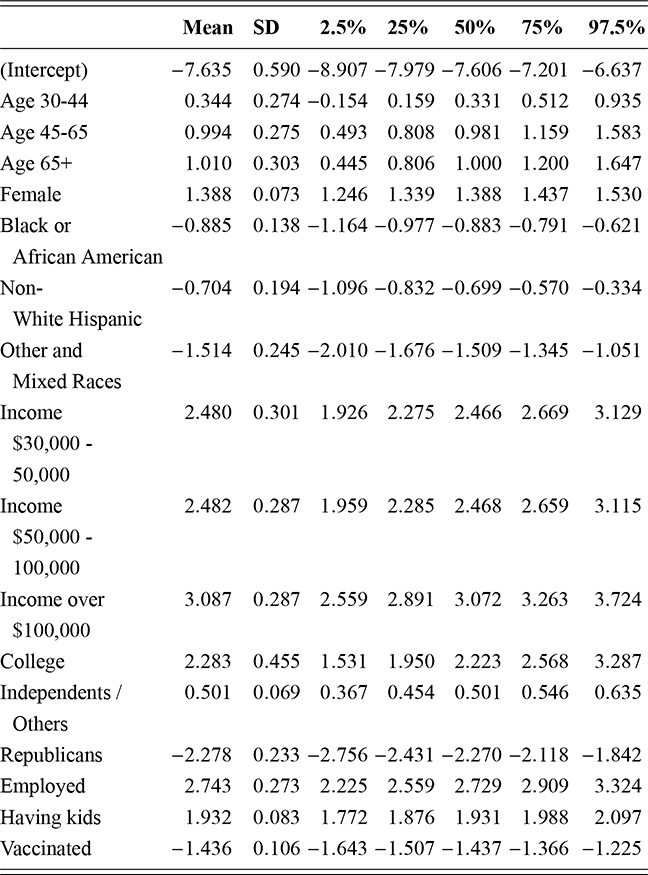

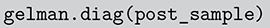

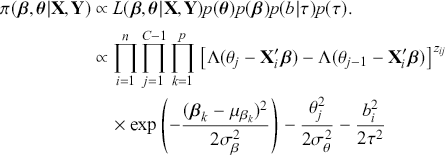

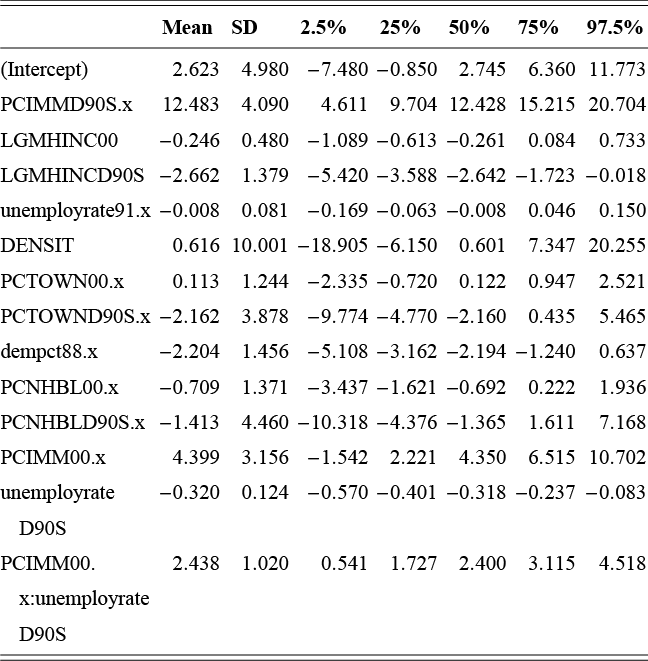

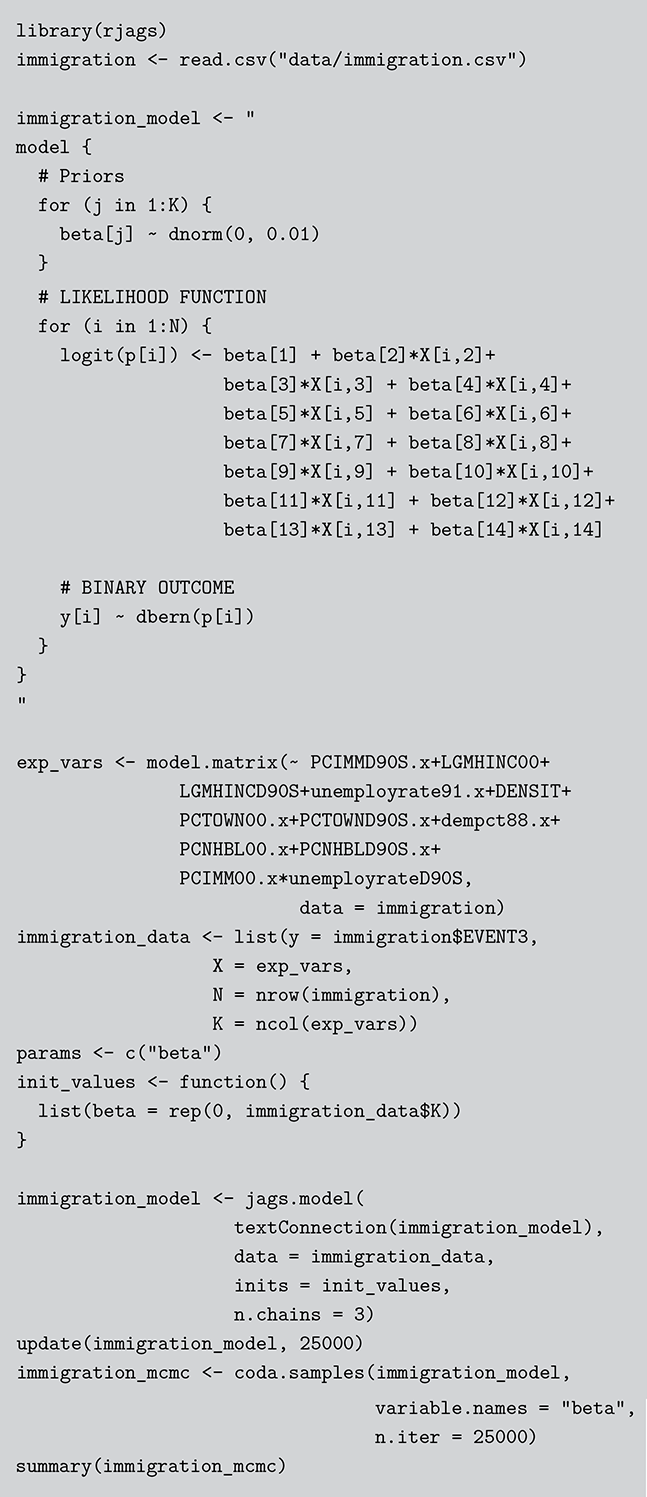

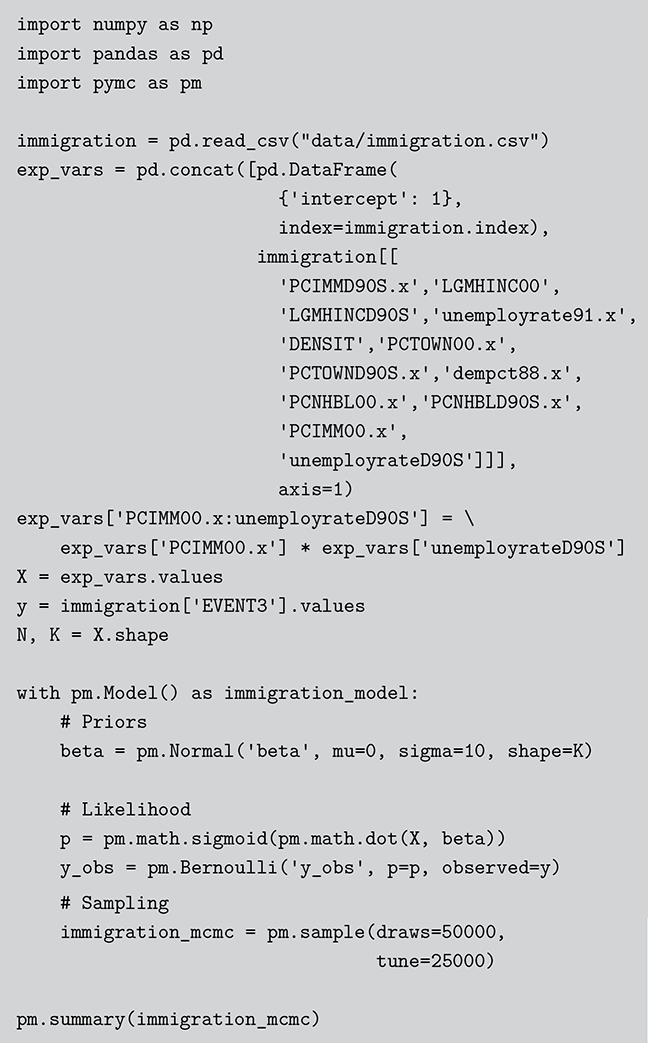

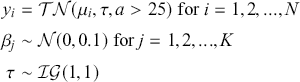

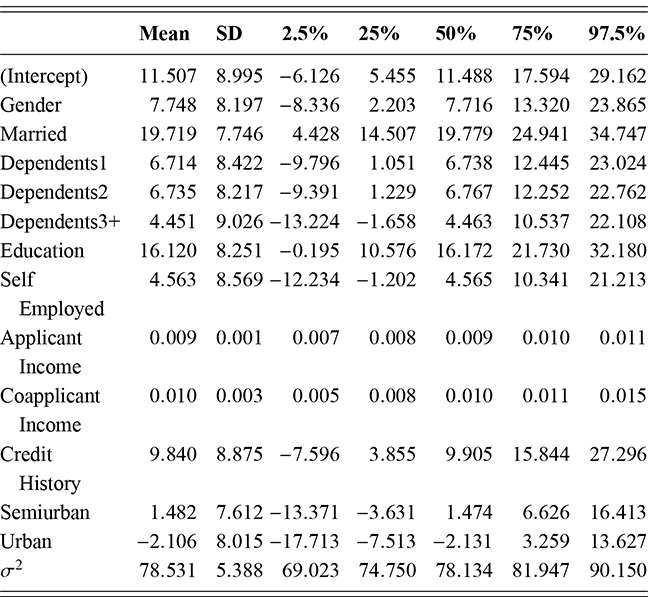

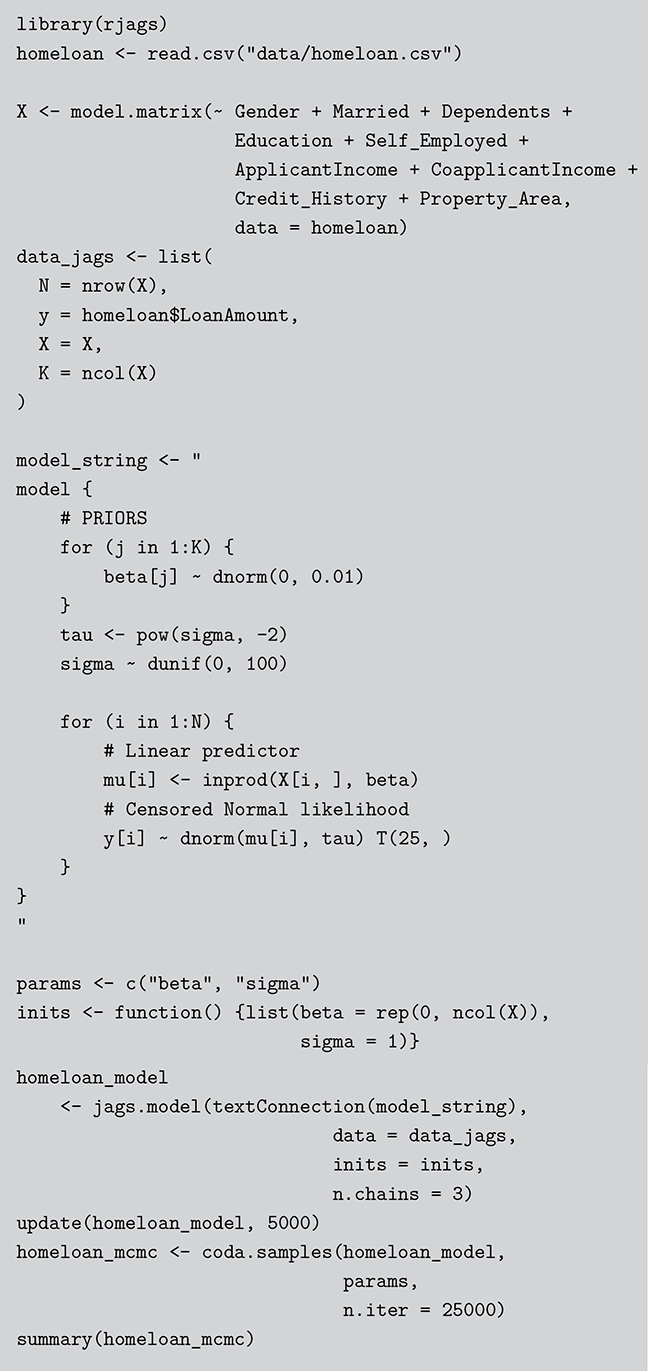

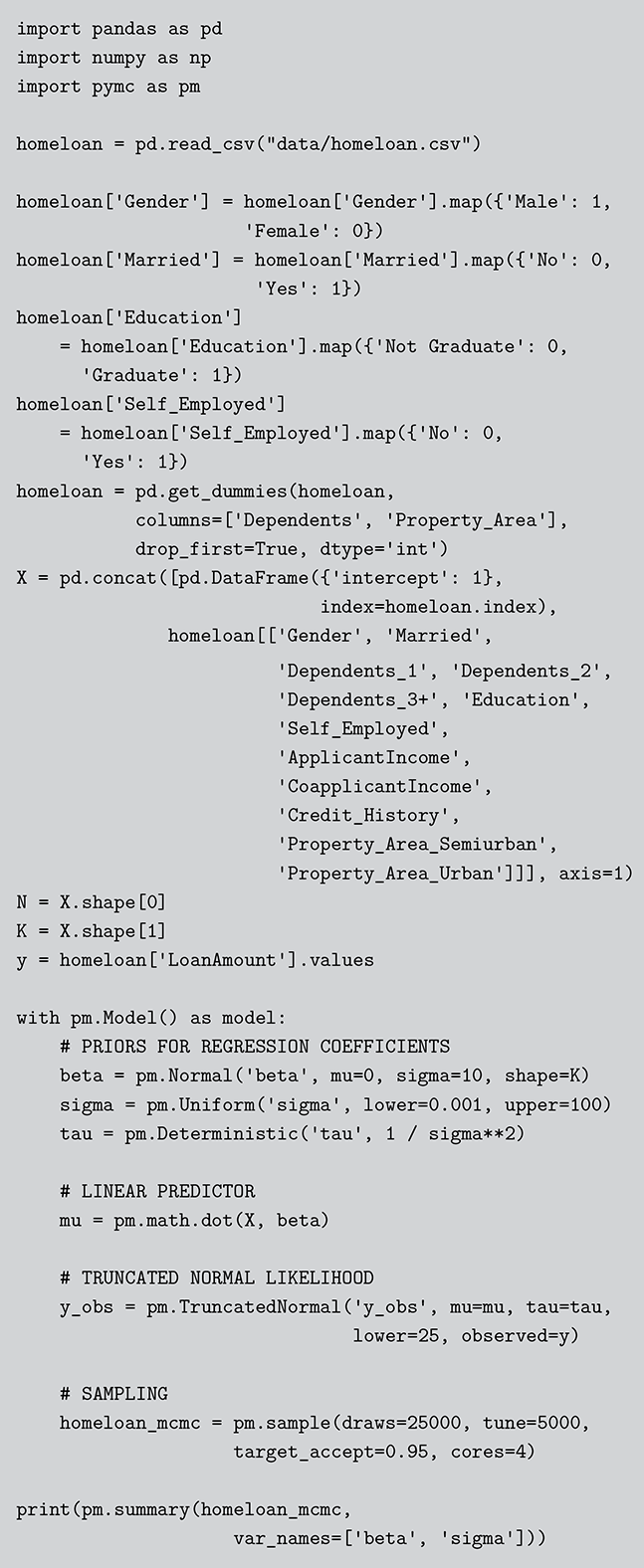

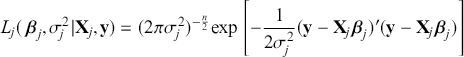

where ![]() denotes the cumulative density function (CDF) of the logistic distribution, meaning this is actually a simplified version. What is this? It is a big joint posterior probability distribution with 16 dimensions, from the 11 explanatory variable parameters, the 4 threshold parameters, and the density (probability) over them. While this form tells us everything we need to know about the joint distribution of the model parameters, we need to marginalize (integrate) it for every one of these parameters to create an informative regression table. This may be very difficult or even impossible. We do not know. But wait! This is a standard model in the toolbox of most practicing quantitative social scientists and we just showed that specifying the most simple Bayesian version of this model leads to an intractable mathematical problem. This example is provided because it highlights the key problem of practicing Bayesian modelers prior to 1990. This was an insurmountable task for twentieth-century Bayesians that was solved in 1990. It turns out that there was a tool hiding in statistical physics and image restoration that completely solved this issue. Employing Markov chain Monte Carlo (Gibbs sampling in this case) allows us to report the standard regression table output in Table 2. Here we see a mixture of results quality. Two reliable effects are interesting: pre-hearing confirmation preparation lowers stress and greater work hours increase stress. Of course, these are nuanced qualitative effects that warrant further investigation.

denotes the cumulative density function (CDF) of the logistic distribution, meaning this is actually a simplified version. What is this? It is a big joint posterior probability distribution with 16 dimensions, from the 11 explanatory variable parameters, the 4 threshold parameters, and the density (probability) over them. While this form tells us everything we need to know about the joint distribution of the model parameters, we need to marginalize (integrate) it for every one of these parameters to create an informative regression table. This may be very difficult or even impossible. We do not know. But wait! This is a standard model in the toolbox of most practicing quantitative social scientists and we just showed that specifying the most simple Bayesian version of this model leads to an intractable mathematical problem. This example is provided because it highlights the key problem of practicing Bayesian modelers prior to 1990. This was an insurmountable task for twentieth-century Bayesians that was solved in 1990. It turns out that there was a tool hiding in statistical physics and image restoration that completely solved this issue. Employing Markov chain Monte Carlo (Gibbs sampling in this case) allows us to report the standard regression table output in Table 2. Here we see a mixture of results quality. Two reliable effects are interesting: pre-hearing confirmation preparation lowers stress and greater work hours increase stress. Of course, these are nuanced qualitative effects that warrant further investigation.

Table 2Long description

The table includes means, standard errors, and 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals for explanatory variables and threshold intercepts. HPD intervals are displayed as horizontal lines with a dashed vertical line at zero for reference. Several intervals lie entirely to one side of zero (e.g., *Career.Exec-Compet*, *Career.Exec-Liaison/Bur*, and *President Orientation*), indicating stronger evidence for nonzero effects. The estimated standard deviation of the latent scale is reported as 6.04 (SD = 1.20).

We know that scientific advances do not proceed in a linear fashion (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1997), and this is a classic example of that. A review paper in 1990 (Gelfand & Smith, Reference Gelfand and Smith1990) changed all of this story. Now we turn our attention to this technology and the basic theory to understand it, starting with the mathematics of Markov chains.

4.2 Markov Chain Theory

The first step in this process is to understand some basic random variable definitions that occur over time. This is a case where the mathematical language does not reflect the simplicity of the principles, so it is important not to be intimidated by the vocabulary.

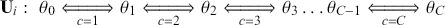

A stochastic process is a consecutive set of random quantities, ![]() s, defined on some known state space,

s, defined on some known state space, ![]() , indexed so that the order is known:

, indexed so that the order is known: ![]() . So

. So ![]() is a generic random variable in the standard statistical sense except that it is observed in a serial manner rather than just all at once in a standard sampling scheme. Here

is a generic random variable in the standard statistical sense except that it is observed in a serial manner rather than just all at once in a standard sampling scheme. Here ![]() just indexes the time of arrival and typically, but not necessarily,

just indexes the time of arrival and typically, but not necessarily, ![]() is the set of positive integers implying consecutive, even-spaced time intervals:

is the set of positive integers implying consecutive, even-spaced time intervals: ![]() . This state space is either discrete or continuous depending on how the variable of interest is measured. So, while the term “stochastic process” sounds very mathematical and intimidating it is really just the simple idea that random variables can have scheduled arrival times.

. This state space is either discrete or continuous depending on how the variable of interest is measured. So, while the term “stochastic process” sounds very mathematical and intimidating it is really just the simple idea that random variables can have scheduled arrival times.

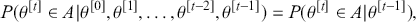

A Markov chain is a stochastic process with the property that any specified state in the series, ![]() , is dependent only the previous value of the chain,

, is dependent only the previous value of the chain, ![]() . Therefore, values are conditionally independent of all other previous values:

. Therefore, values are conditionally independent of all other previous values: ![]() . More formally:

. More formally:

(4.4)

(4.4)

where this is the probability that ![]() lands in some region

lands in some region ![]() , which is any identified subset (an event or range of events) on the complete state space defined by

, which is any identified subset (an event or range of events) on the complete state space defined by ![]() . We will use this

. We will use this ![]() notation extensively. Colloquially we can say:

notation extensively. Colloquially we can say:

“A Markov chain wanders around the state space caring only about where it is at the moment in making decisions about where to move in the next step.”

Anyone who has ever owned a house cat or been around them much will certainly feel that cats have a very Markovian quality to their behavior. Again, this is a simple idea that unfortunately gets wrapped up in intimidating mathematical language. Necessarily Markov chains are based on a probabilistic process, a “kernel,” that makes a decision about the next draw of ![]() at time

at time ![]() based only on the current existing draw of

based only on the current existing draw of ![]() at time

at time ![]() . This leads to the standard analogy that the Markov chain is traveling through the state space defined by the support

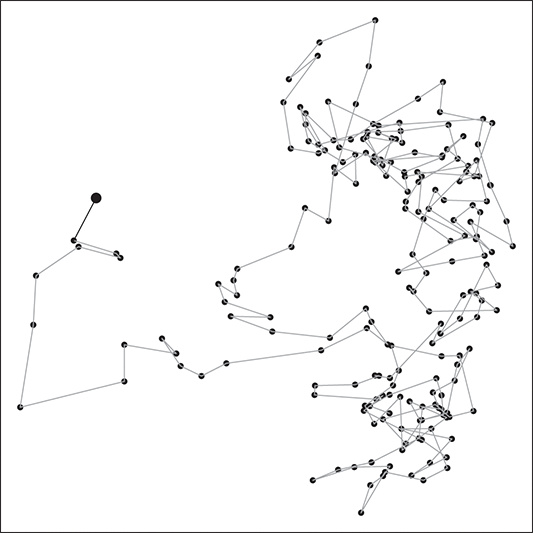

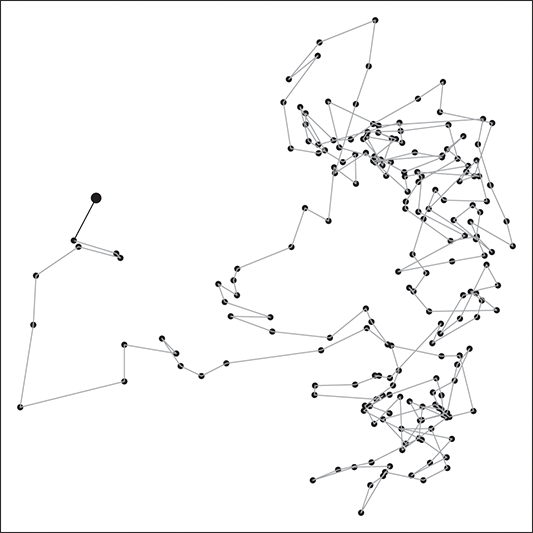

. This leads to the standard analogy that the Markov chain is traveling through the state space defined by the support ![]() . So we think of a serial path of the chain like an ant wandering around some topology on the ground. Consider Figure 3 where a 2-dimensional Markov chain is started at the point indicated by a larger dot (all Markov chains need an arbitrary starting point in the sample space), and the first step indicated by the bold black line segment segment. In this case we would call this a random walk Markov chain because we have not imposed any conditions on its behavior other than a random normal draw added to the current position.

. So we think of a serial path of the chain like an ant wandering around some topology on the ground. Consider Figure 3 where a 2-dimensional Markov chain is started at the point indicated by a larger dot (all Markov chains need an arbitrary starting point in the sample space), and the first step indicated by the bold black line segment segment. In this case we would call this a random walk Markov chain because we have not imposed any conditions on its behavior other than a random normal draw added to the current position.

Figure 3 Sample Markov Chain Path

So why is the Markovian property useful? This “short-term” memory property is very handy because when we impose some specific mathematical restrictions on the chain and allow it to explore a specific distributional form, it eventually finds the region of the state space with the highest density, and it will wander around there producing an empirical sample from it in proportion to the probability. If this distribution is the posterior from model, then we can use these “empirical” values as legitimate posterior sample values. Thus, difficult posterior calculations can be done with MCMC by letting the chain wander around “sufficiently long,” thus producing summary statistics from recorded values. For example, if we wanted marginal draws from the big awkward joint distribution in (4.3) then the Markov chain explores the multidimensional state space recording where it has been for us. This means that we can take the empirical values for each dimension (model parameter) and summarize them any way we want.

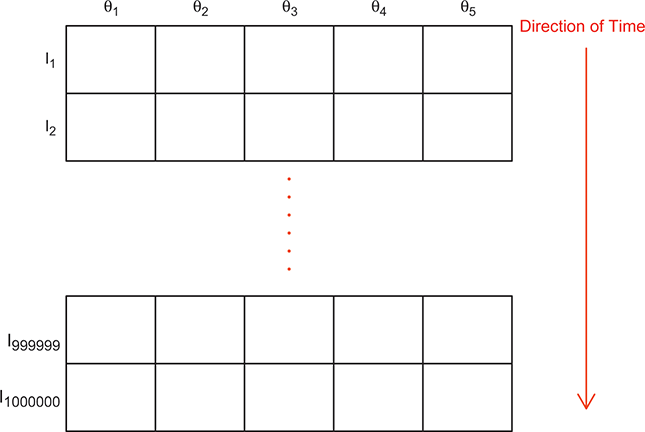

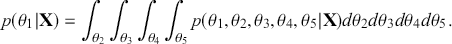

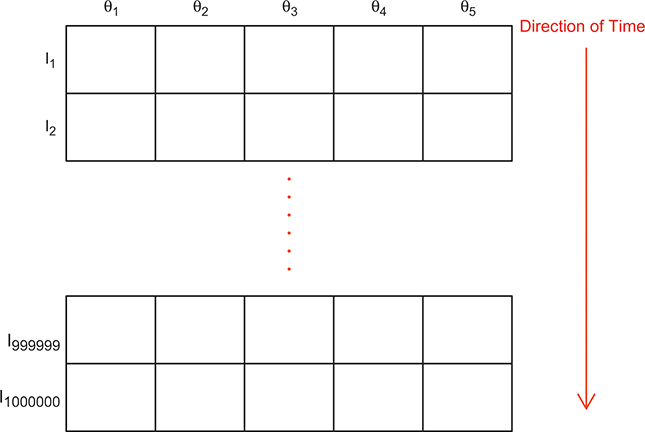

To clarify this strategy, consider the output of a Markov chain with 5 parameters run for 500,000 iterations. This means that it has visited 500,000 locations in the state space, and each 5-dimensional location is a row of a stored matrix. To get the marginal distribution analytically by contrast for just ![]() , we would have to perform the integration in four steps:

, we would have to perform the integration in four steps:

(4.5)

(4.5)

That’s a lot of work! And that’s for one of the dimensions; it needs to be done for all 5 of them. Recall from the structure of the joint distribution in (4.3) that this can be really hard or even impossible for humans with some model specifications. However, once we have run the Markov chain sufficiently long (more on this shortly) and stored the values in matrix form, then we get an empirical distribution for each of the parameters simply by looking down the columns. For instance, rather than do the integration process in (4.5), we would just pull out the values in column one to produce a vector of draws for the first parameter only. Doing the integration process gives an exact marginal distribution in mathematical terms, ![]() . But wait! If we have half-a-million draws from this marginal distribution, then we actually have all of the information we need to know for scientific purposes. That is, we can take the mean and standard deviation of the vector to produce the information needed for a regression table. We can also calculate any other desired statistic or summary: quantiles, different measures of centrality and variance, probabilities over ranges, HPD intervals, and so on. Furthermore, given the Law of Large Numbers we know that we are very nearly precisely correct, given a very big number of draws like 500,000.

. But wait! If we have half-a-million draws from this marginal distribution, then we actually have all of the information we need to know for scientific purposes. That is, we can take the mean and standard deviation of the vector to produce the information needed for a regression table. We can also calculate any other desired statistic or summary: quantiles, different measures of centrality and variance, probabilities over ranges, HPD intervals, and so on. Furthermore, given the Law of Large Numbers we know that we are very nearly precisely correct, given a very big number of draws like 500,000.

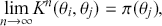

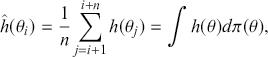

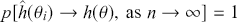

How does the Markov chain decide to move? The Markov chain moves based on a probability statement so we need to define how probability enters the decision. First, define the transition kernel, ![]() , as a very general, and for the moment unspecific, mechanism for describing the probability of moving to some other specified state based on the current chain location. Here

, as a very general, and for the moment unspecific, mechanism for describing the probability of moving to some other specified state based on the current chain location. Here ![]() is a defined probability measure for all

is a defined probability measure for all ![]() points in the state space to the set (subspace)

points in the state space to the set (subspace) ![]() . Therefore

. Therefore ![]() maps potential transition events to their probability of occurrence. Note that, in the current discussion,

maps potential transition events to their probability of occurrence. Note that, in the current discussion, ![]() is a multidimensional point in the sample space and not a coefficient to be estimated. This is slightly confusing given the preceding discussion, but this notation is consistent with the literature.

is a multidimensional point in the sample space and not a coefficient to be estimated. This is slightly confusing given the preceding discussion, but this notation is consistent with the literature.

Let us start with a simple discrete form of a two-dimensional state space, ![]() , with 64

, with 64 ![]() locations: the chess board. Discrete state spaces in this discussion are much easier to conceptualize so we will restrict ourselves to this form for now. It is also easy with this example to define various

locations: the chess board. Discrete state spaces in this discussion are much easier to conceptualize so we will restrict ourselves to this form for now. It is also easy with this example to define various ![]() subspaces, like, say, the four squares in the top right-hand side of this chess board. The most flexible and powerful piece in chess is the Queen who can move any distance on the board vertically, horizontally, and diagonally. Now imagine a Super-Queen who can move from any square to any other square on the chessboard in one move, arbitrarily for from

subspaces, like, say, the four squares in the top right-hand side of this chess board. The most flexible and powerful piece in chess is the Queen who can move any distance on the board vertically, horizontally, and diagonally. Now imagine a Super-Queen who can move from any square to any other square on the chessboard in one move, arbitrarily for from ![]() to

to ![]() , where the transition kernel is uniform selection of any of the 64 squares. Thus we have 64 moves from some

, where the transition kernel is uniform selection of any of the 64 squares. Thus we have 64 moves from some ![]() to another

to another ![]() , including moving to where we already are:

, including moving to where we already are: ![]() . The latter scenario is included because the current location is always a valid destination for a Markov chain.

. The latter scenario is included because the current location is always a valid destination for a Markov chain.

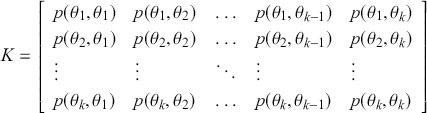

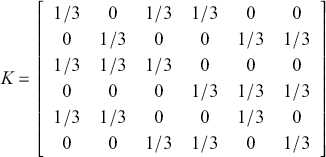

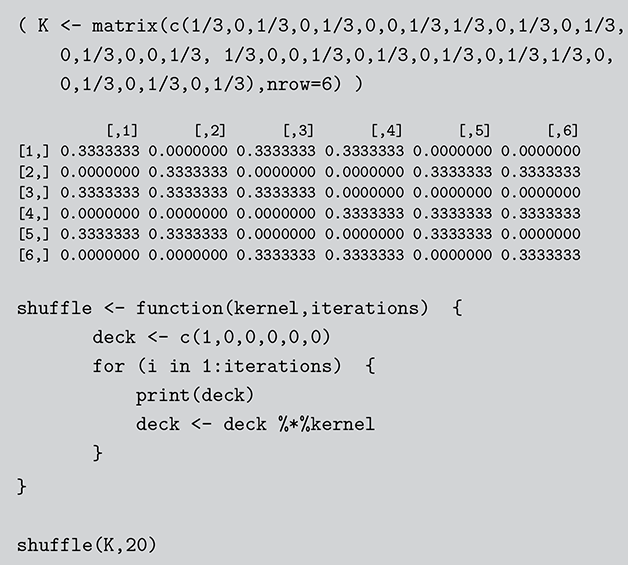

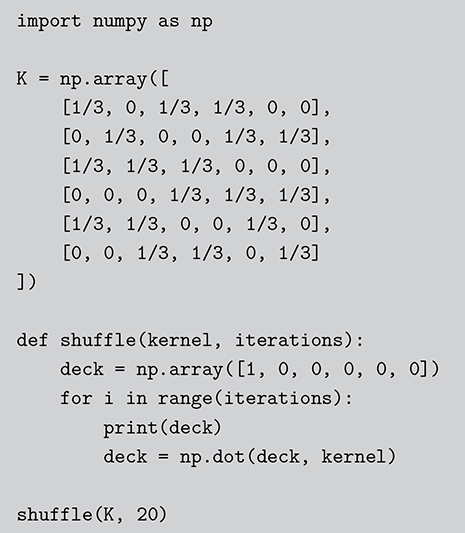

When the state space is discrete, ![]() is a matrix mapping for

is a matrix mapping for ![]() discrete elements in

discrete elements in ![]() , where each cell defines the probability of a state transition from the first term to all possible states. So for a rectangular 2-dimensional state space like the chess board (

, where each cell defines the probability of a state transition from the first term to all possible states. So for a rectangular 2-dimensional state space like the chess board (![]() ), the transition matrix giving the probabilities of moving from any square to any other square for our Super-Queen is:

), the transition matrix giving the probabilities of moving from any square to any other square for our Super-Queen is:

where the row indicates where the chain is at this period. Thus the first row gives the 64 probabilities of starting at ![]() (say the top leftmost corner if we are mapping the chess board like reading a paragraph) to all of the 64 possible destinations starting with

(say the top leftmost corner if we are mapping the chess board like reading a paragraph) to all of the 64 possible destinations starting with ![]() for returning to the current location using up a unit of time index, and proceeding to

for returning to the current location using up a unit of time index, and proceeding to ![]() for moving from the top left corner to the bottom right corner. It is important that each matrix row is a well-behaved probability function,

for moving from the top left corner to the bottom right corner. It is important that each matrix row is a well-behaved probability function, ![]() in the sense of the Kolmogorov Axioms. Rows of

in the sense of the Kolmogorov Axioms. Rows of ![]() sum to one and define a conditional probability mass function (PMF) since they are all specified for the same starting value as the condition and cover each possible destination in the state space: for row

sum to one and define a conditional probability mass function (PMF) since they are all specified for the same starting value as the condition and cover each possible destination in the state space: for row ![]() :

: ![]() . As a side note for now, when the state space is continuous, then

. As a side note for now, when the state space is continuous, then ![]() is a conditional PDF:

is a conditional PDF: ![]() .

.

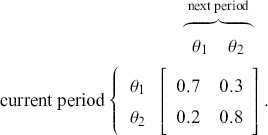

Consider a very simple mathematical example to get us started. Define a two-dimensional state space: a discrete vote choice between two political parties, a commercial purchase decision between two brands, a choice by a nation to go to war with another nation, and so on. In this setup, voters, consumers, predators, viruses, and so on. who normally select ![]() have a 70% chance of continuing to do so, and voters/consumers/predators/viruses/and so on who normally select

have a 70% chance of continuing to do so, and voters/consumers/predators/viruses/and so on who normally select ![]() have an 80% chance of continuing to do so. This provides the transition matrix

have an 80% chance of continuing to do so. This provides the transition matrix ![]() :

:

As a running hypothetical case, suppose we are doing market research for a major toothpaste brand and ![]() designates a purchase of Crest, and

designates a purchase of Crest, and ![]() designates a purchase of Colgate. So from the preceding transition matrix, in any given time period, 70% of the Crest buyers stay loyal whereas 80% of the Colgate buyers remain loyal. This is just a mapping from one time period to the next since it defines a Markovian process where the past before that does not matter. All Markov chains require a starting point, in this context set by a human to

designates a purchase of Colgate. So from the preceding transition matrix, in any given time period, 70% of the Crest buyers stay loyal whereas 80% of the Colgate buyers remain loyal. This is just a mapping from one time period to the next since it defines a Markovian process where the past before that does not matter. All Markov chains require a starting point, in this context set by a human to

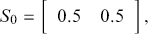

meaning that we initially recruit a sample that is one-half Crest buyers and one-half Colgate buyers. To go from this initial state to the first state, we simply postmultiply the starting state by the transition matrix:

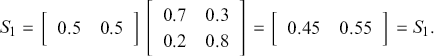

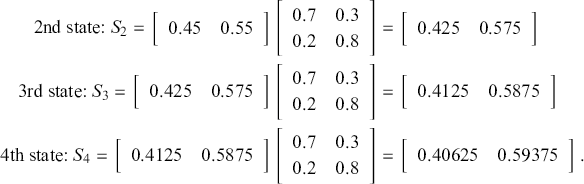

So, observing our sample’s purchase at time period ![]() , we see that 45% bought Crest and 55% bought Colgate. This series of observed purchases continues multiplicatively as long as we want to study our sample:

, we see that 45% bought Crest and 55% bought Colgate. This series of observed purchases continues multiplicatively as long as we want to study our sample:

If we continued this process a few more times, the resulting state of ![]() would emerge (try it!) and would never change no matter how many times we performed this operation. This is called the steady state, the stationary distribution, or the ergodic state (the latter for reasons that we will see later on page 31). Markov chains are not guaranteed to have this property and those that do not are called transient Markov chains.

would emerge (try it!) and would never change no matter how many times we performed this operation. This is called the steady state, the stationary distribution, or the ergodic state (the latter for reasons that we will see later on page 31). Markov chains are not guaranteed to have this property and those that do not are called transient Markov chains.

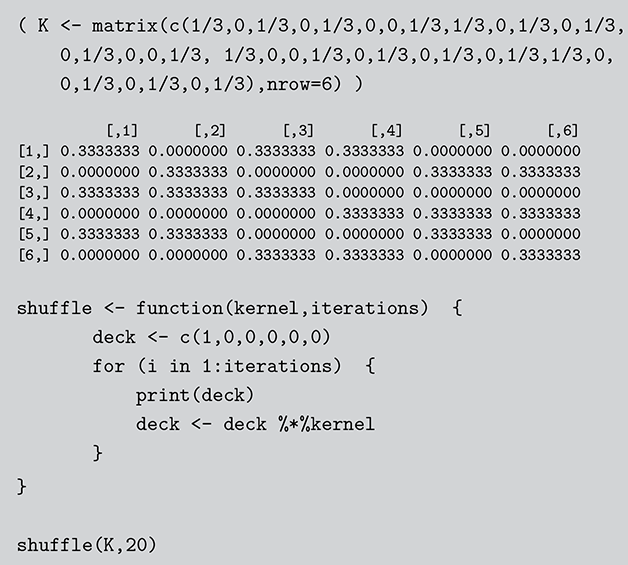

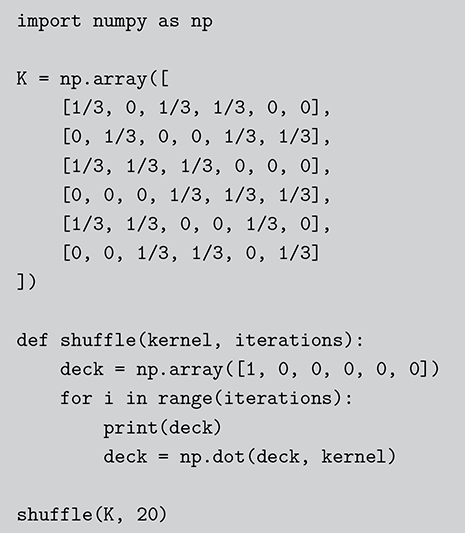

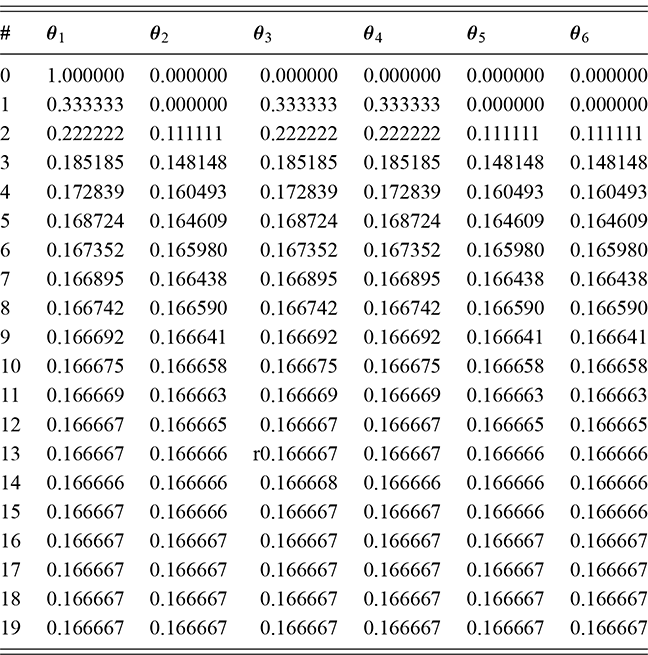

In this section we describe another simple discrete Markov chain simplified from Bayer and Diaconis (Reference Bayer and Diaconis1992), and also described in Gill (Reference Gill2014). Suppose we have the following algorithm for shuffling a deck of cards: take the top card from the deck and with equal probability place it somewhere in the deck, then repeat many times. The objective (stationary distribution) is a uniformly random distribution in the deck: for any given order to the stack, the probability of any one card occupying any one position is 1/52. Is this a stochastic process? Sure, there is a set of discrete outcomes which are the ordering of the deck that change with each step and have a state space that is ![]() big. Is this a Markov chain? Yes, clearly, because if we want to know the probability that the deck is in some specific ordering after the next step we only need to know the current status of the deck to compute the probabilities of the 52 possible arrangements at the next state. These are presumably all

big. Is this a Markov chain? Yes, clearly, because if we want to know the probability that the deck is in some specific ordering after the next step we only need to know the current status of the deck to compute the probabilities of the 52 possible arrangements at the next state. These are presumably all ![]() if we adhere to the condition of uniform random replacement presented earlier. So the previous states of the deck do not help us in any way. As long as we know the current state of the deck we have all the information required to use the transition kernel to move. What is the limiting distribution? For this, we will use simulation as a convenience as noted many times here.

if we adhere to the condition of uniform random replacement presented earlier. So the previous states of the deck do not help us in any way. As long as we know the current state of the deck we have all the information required to use the transition kernel to move. What is the limiting distribution? For this, we will use simulation as a convenience as noted many times here.

For simplicity and without loss of generality we will use a deck with only ![]() cards. This is the same problem as using

cards. This is the same problem as using ![]() cards but is a lot easier to describe and visualize. With three numbered cards we have a sample space of size

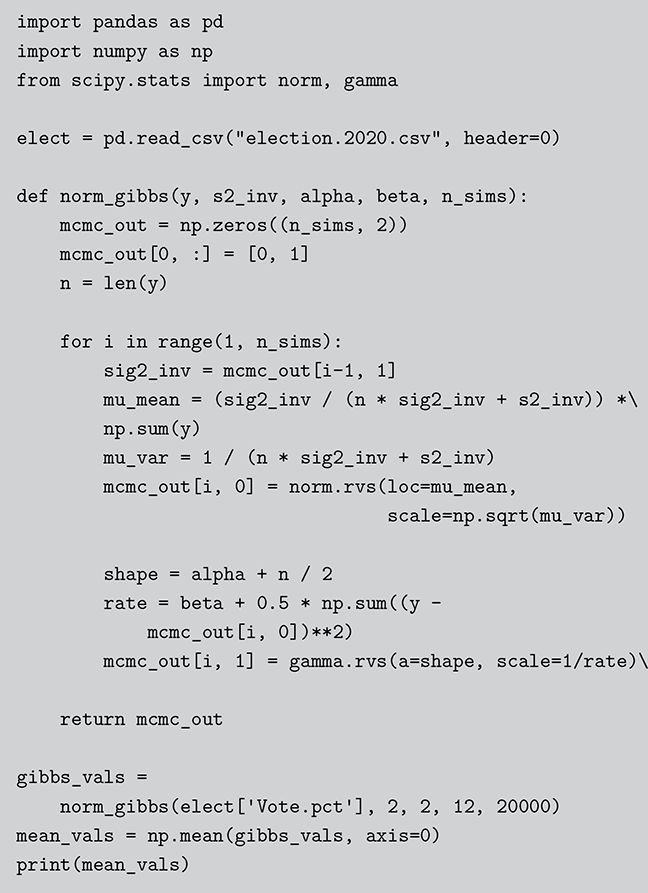

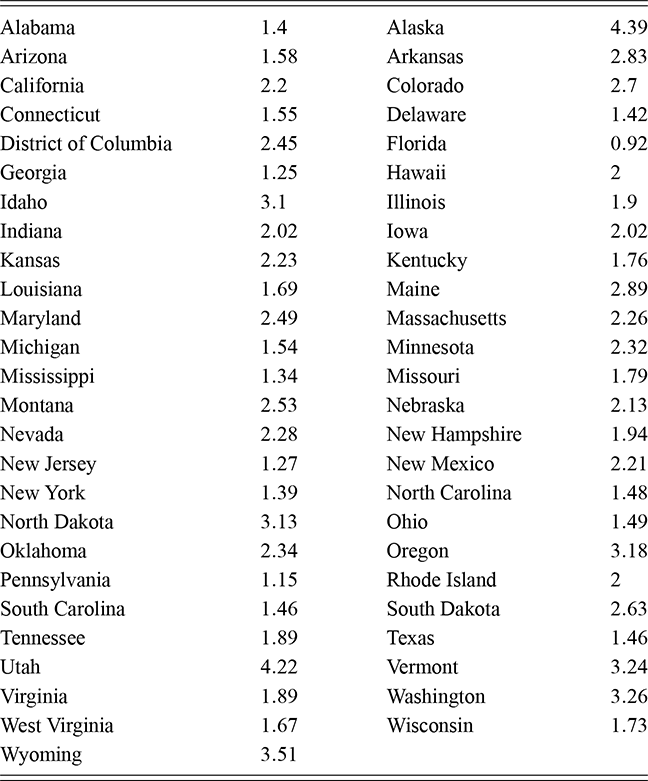

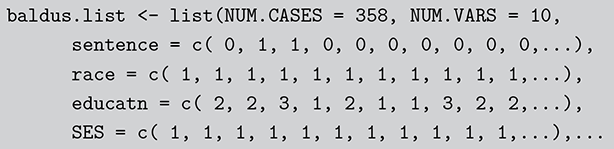

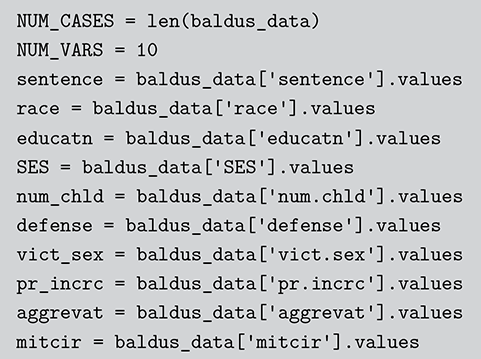

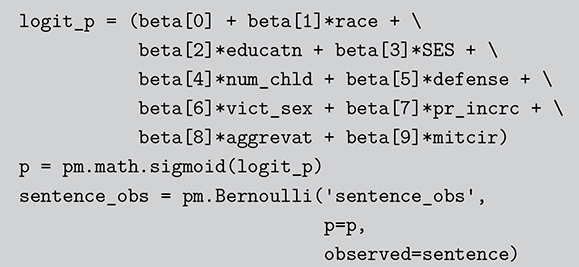

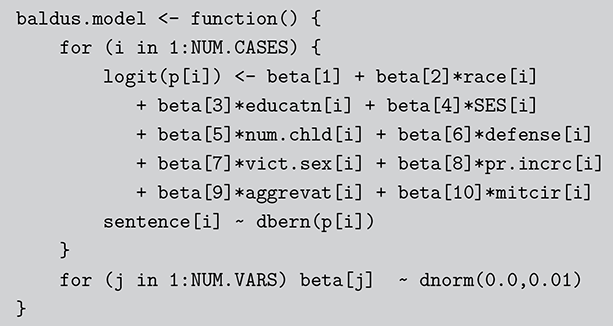

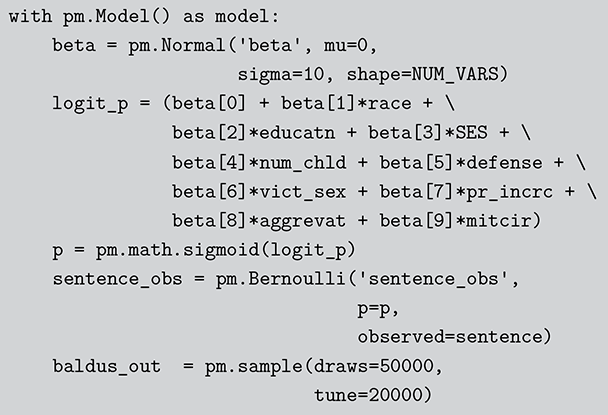

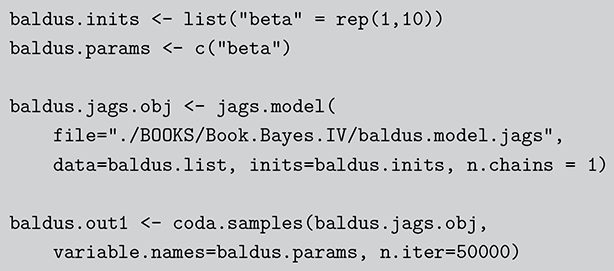

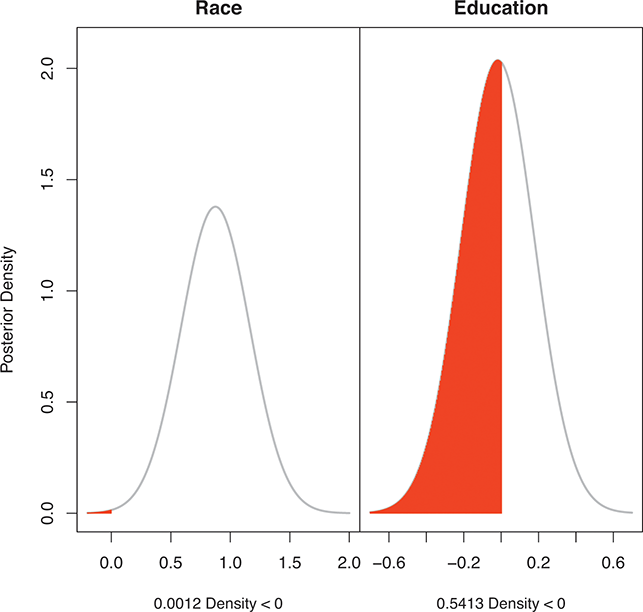

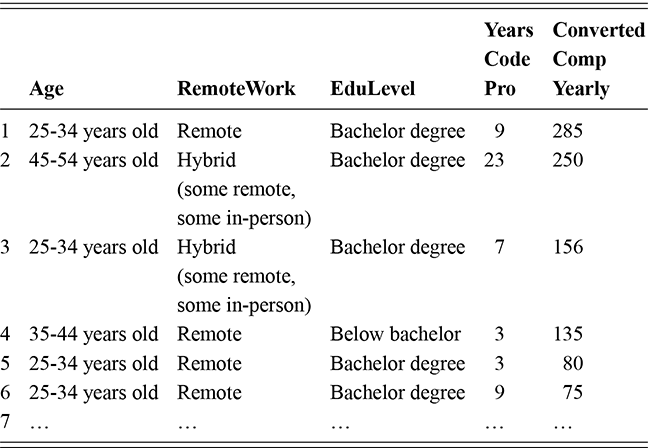

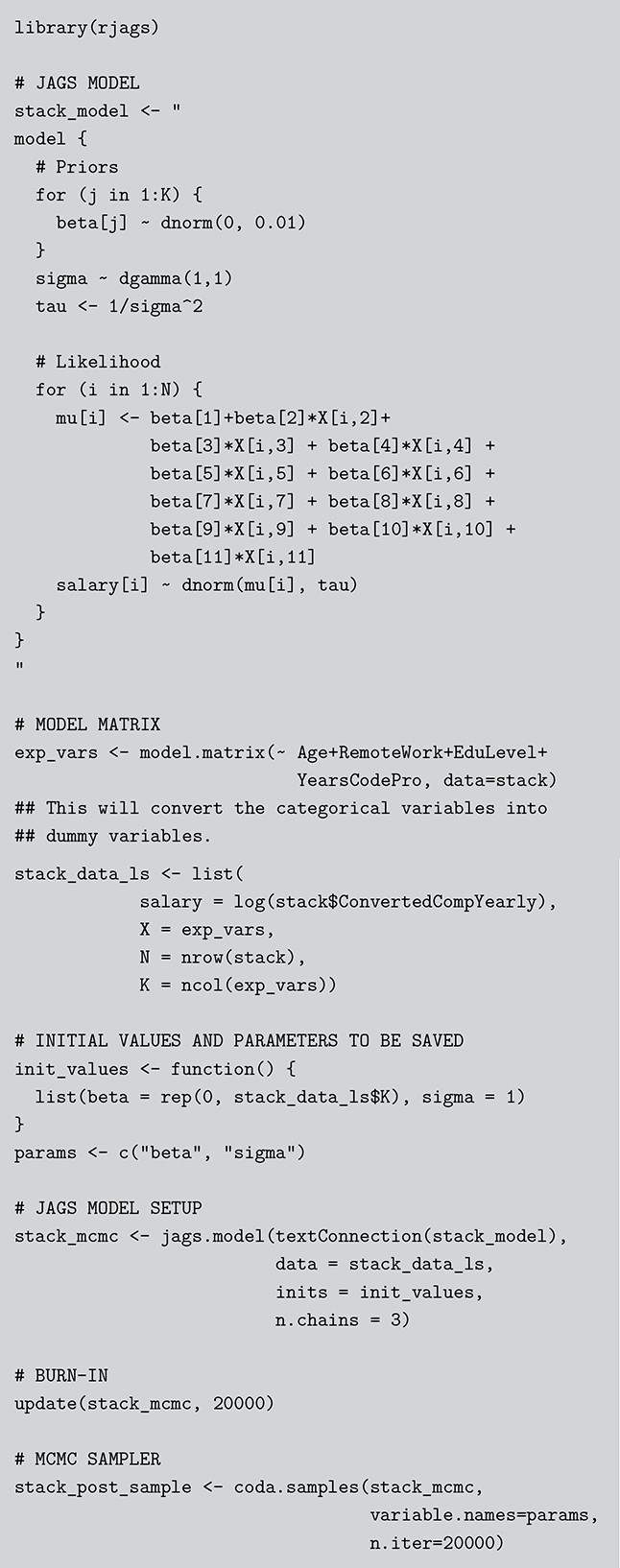

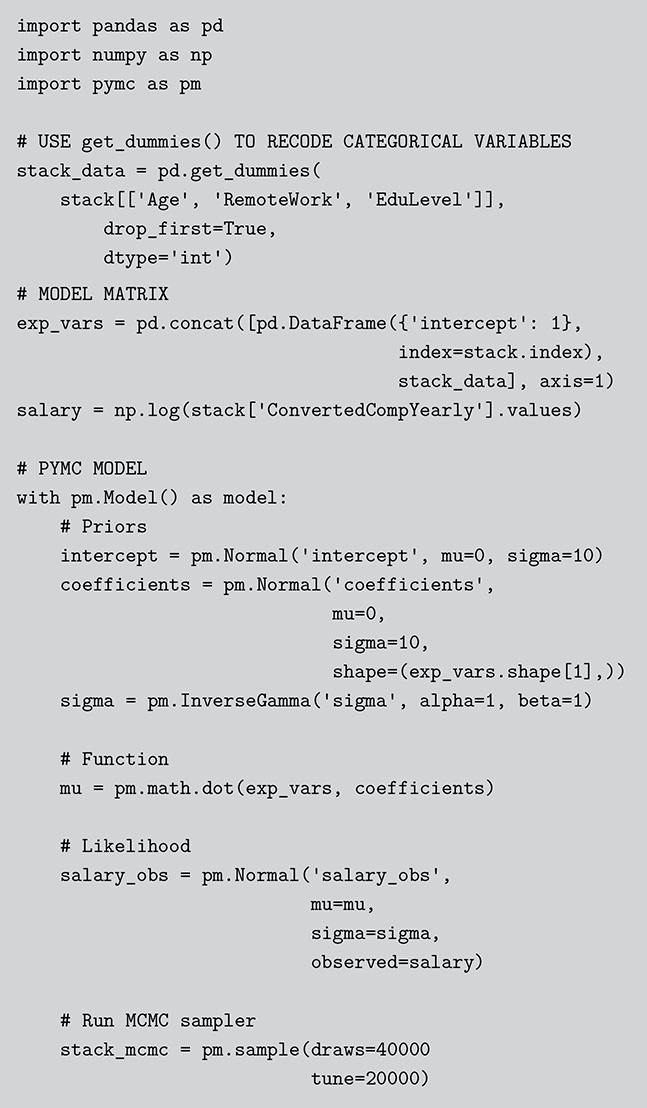

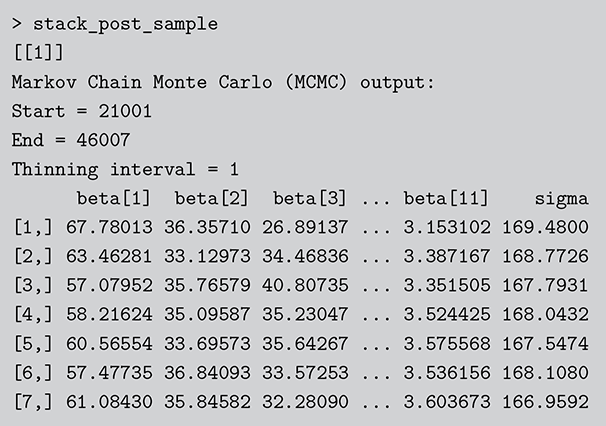

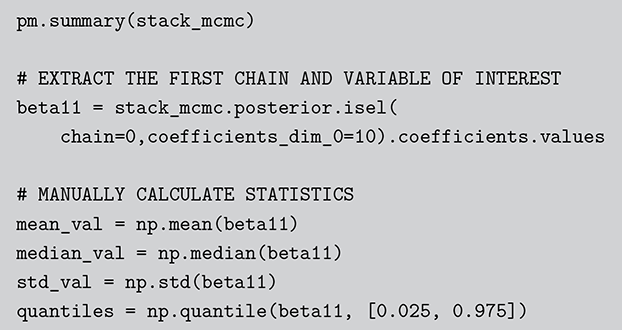

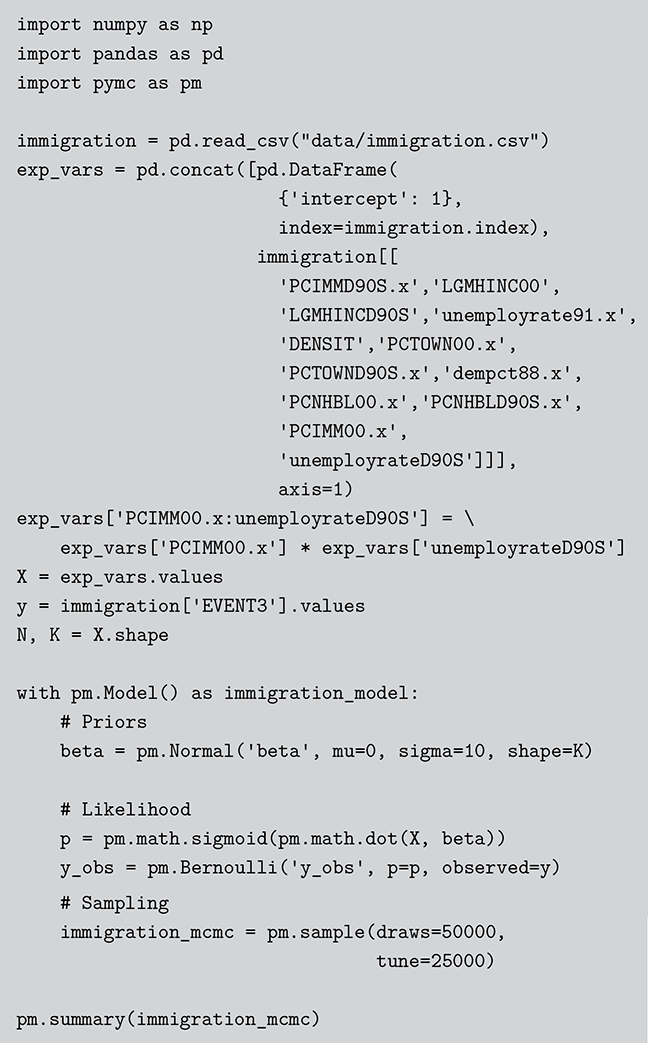

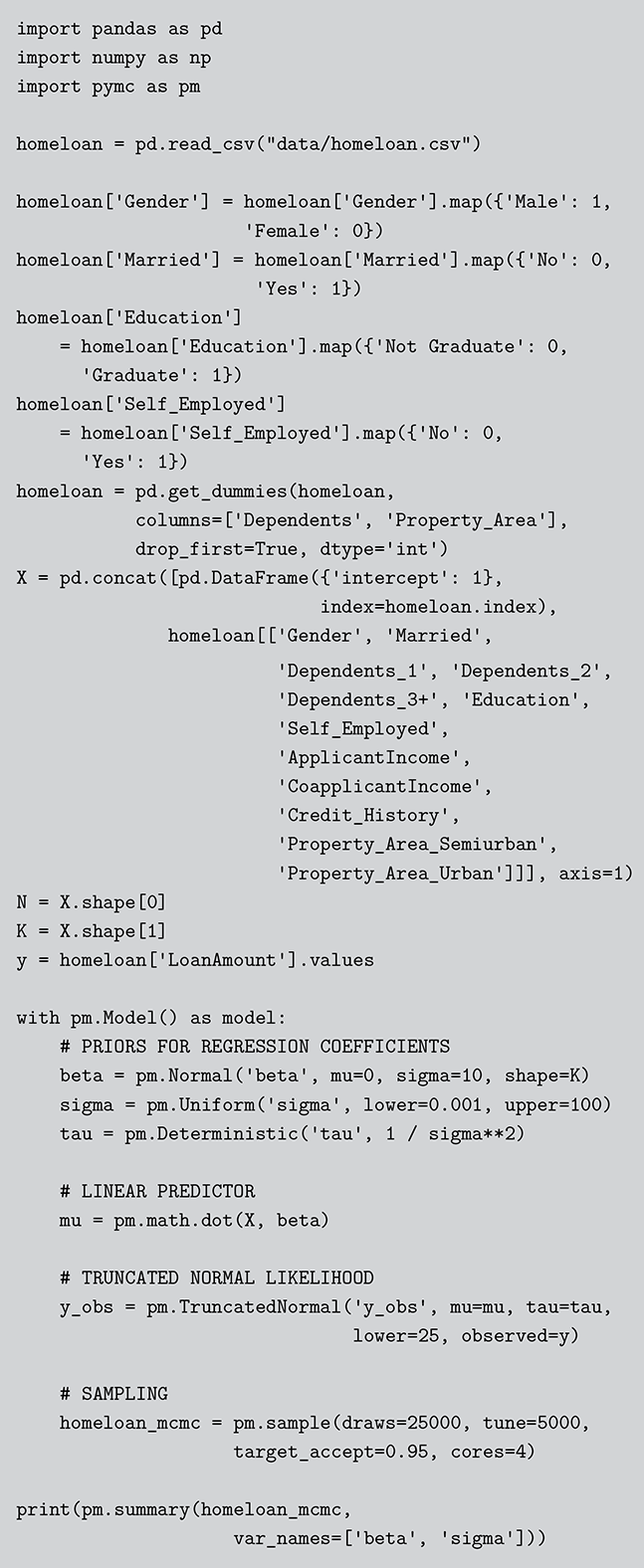

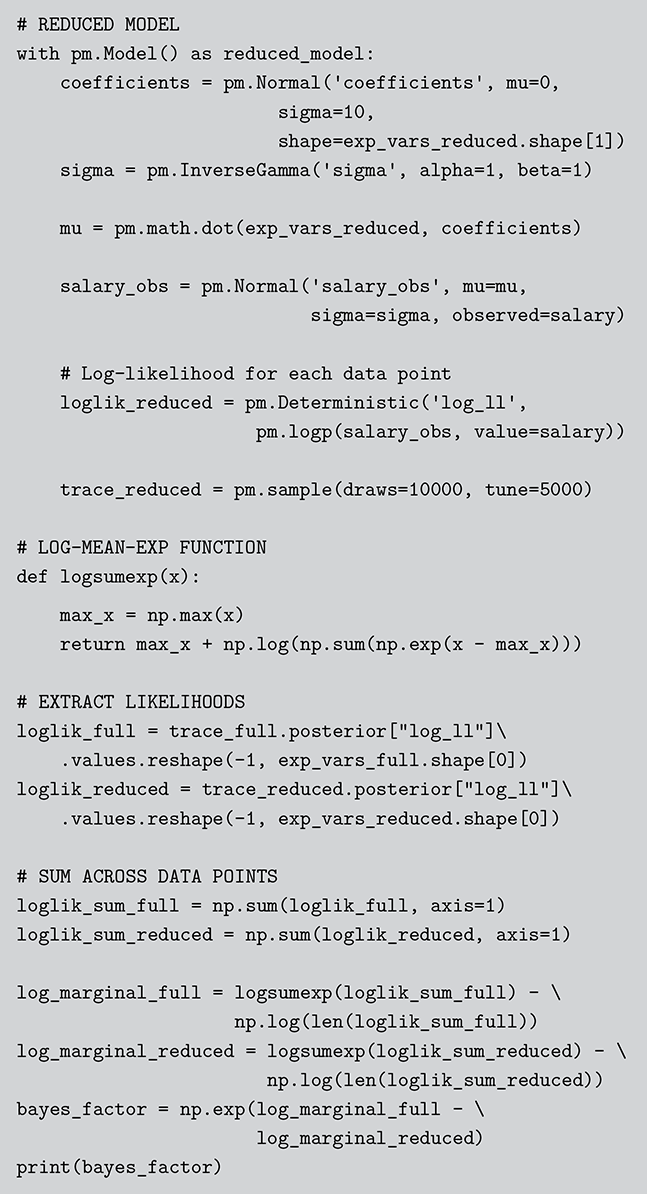

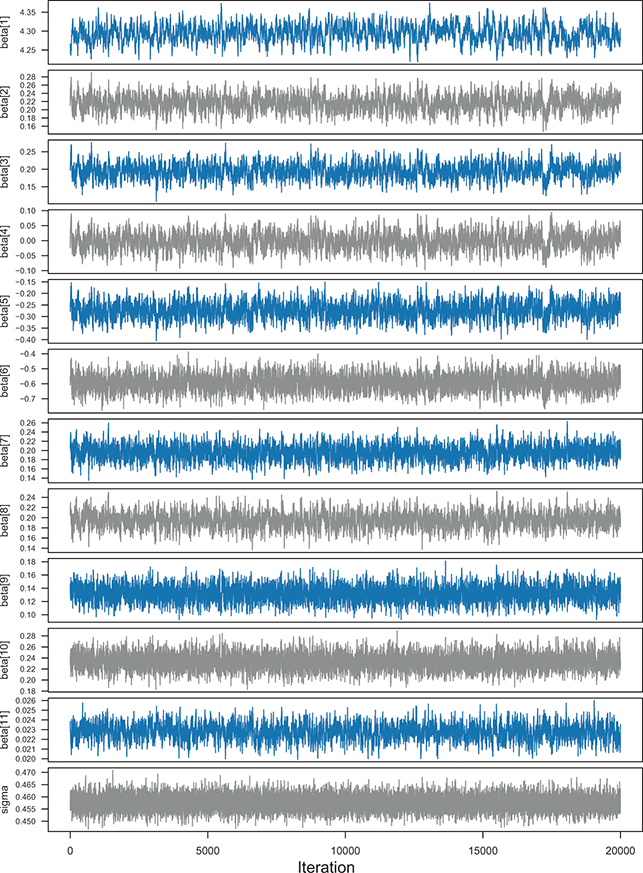

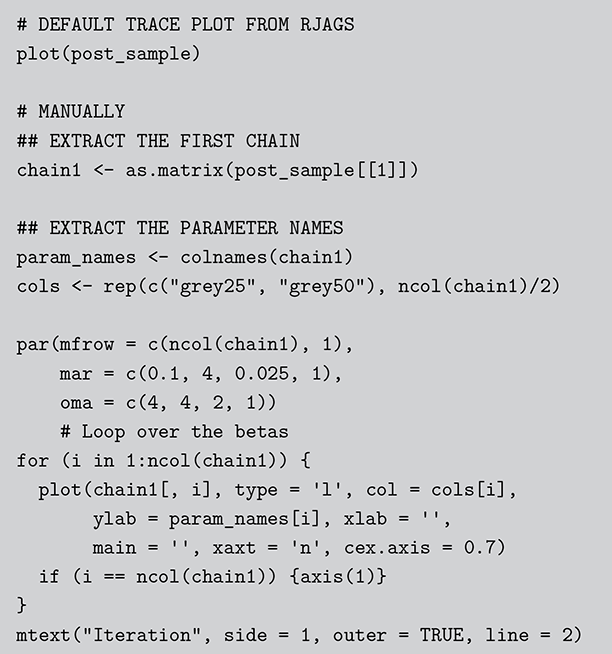

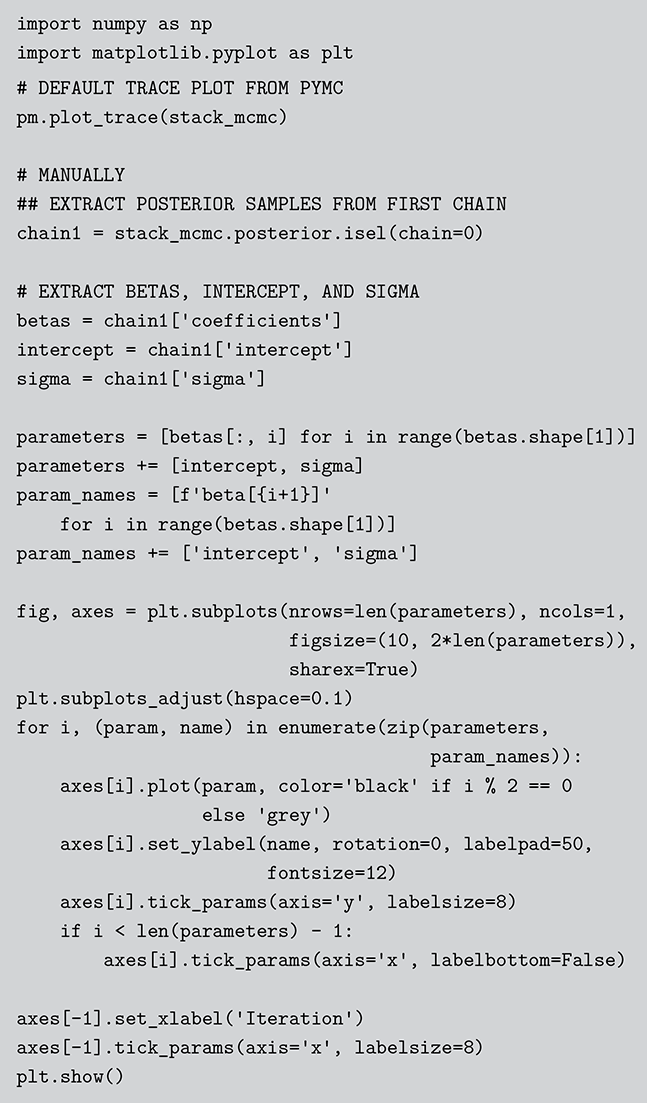

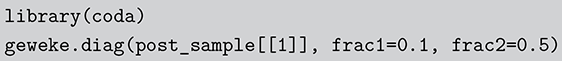

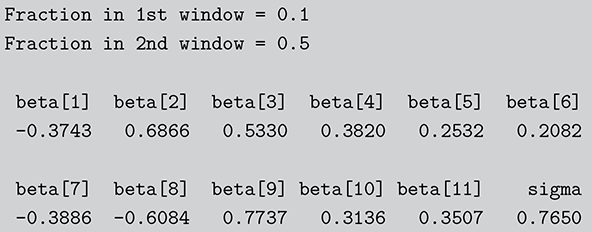

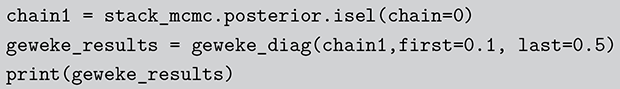

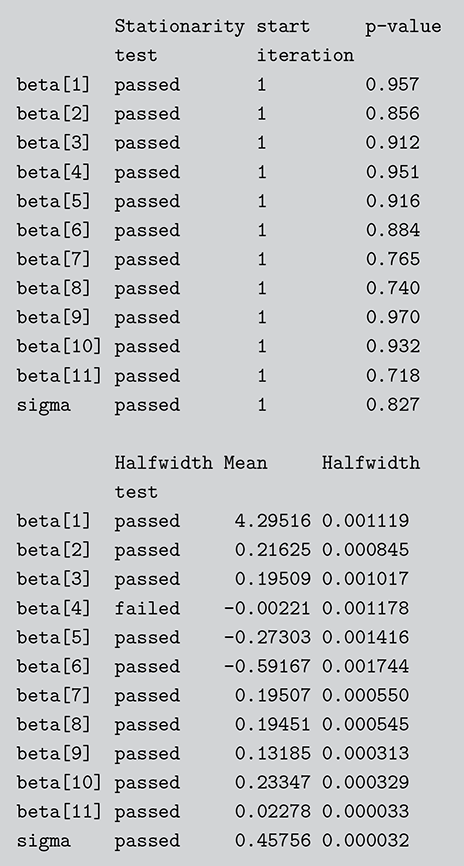

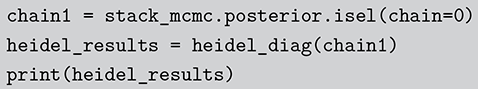

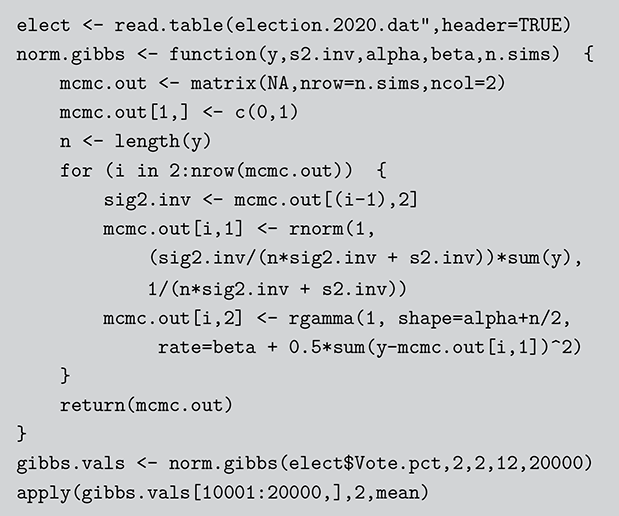

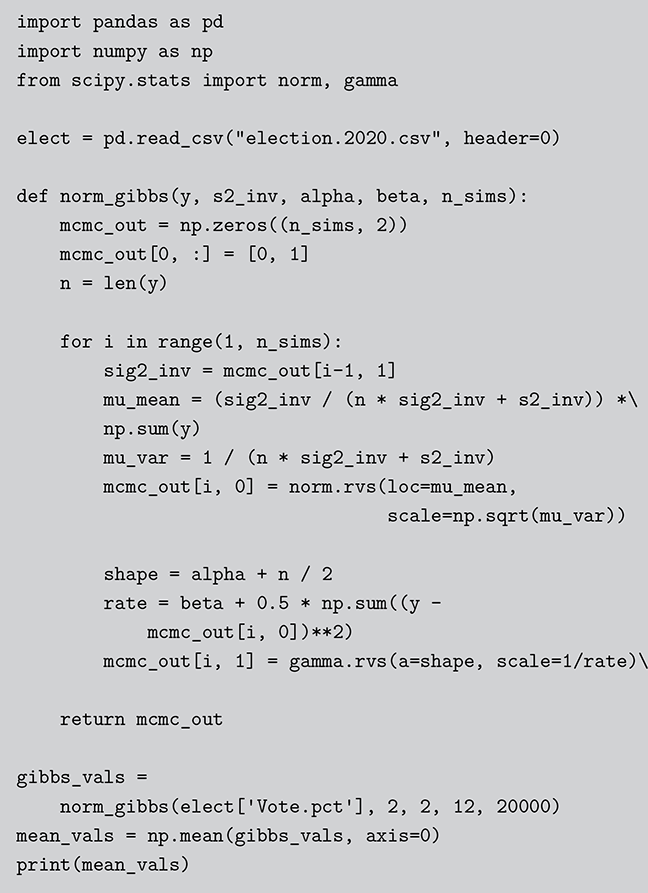

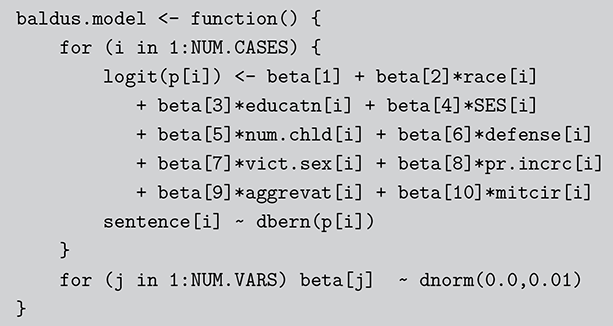

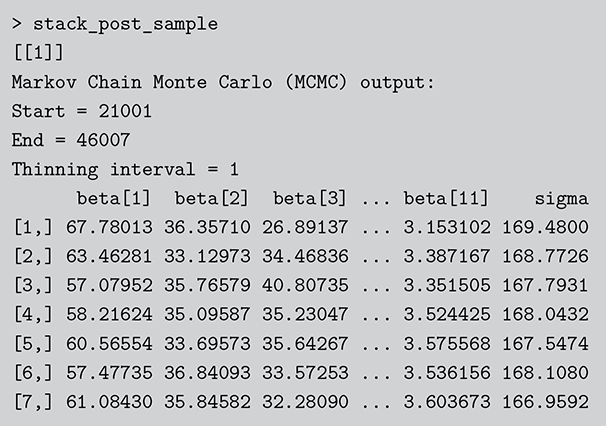

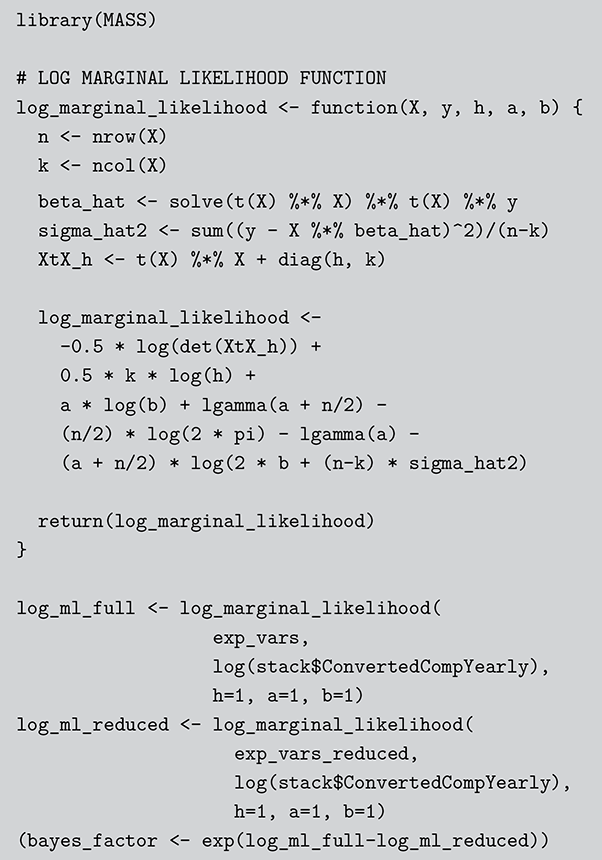

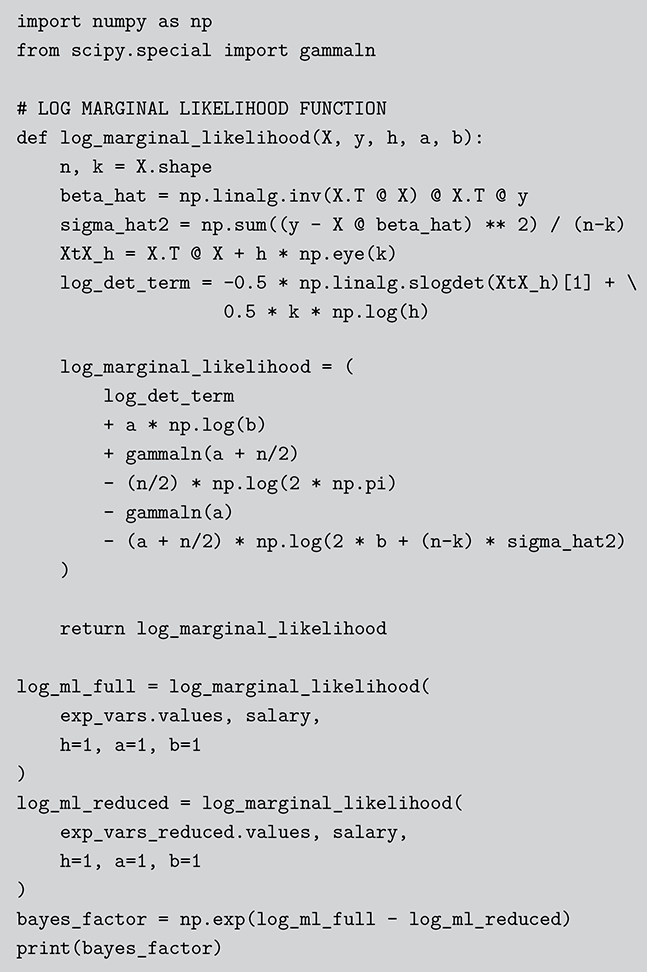

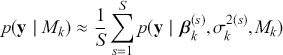

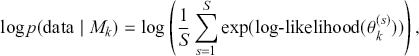

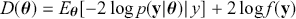

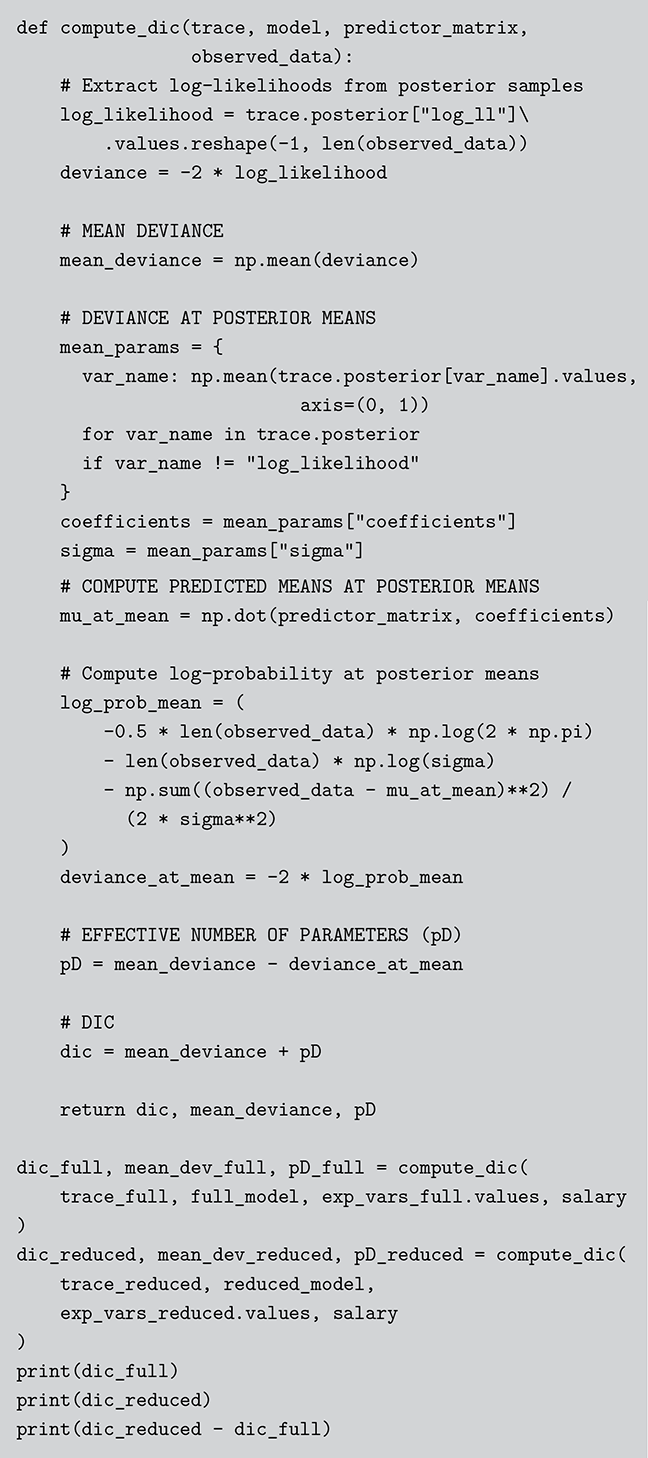

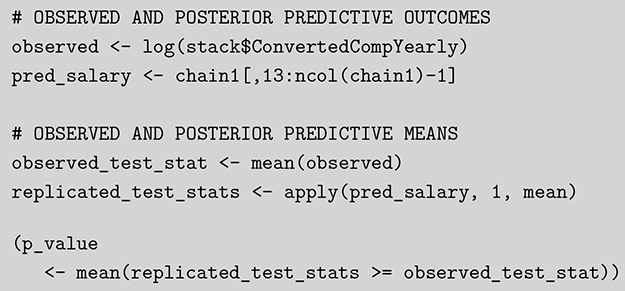

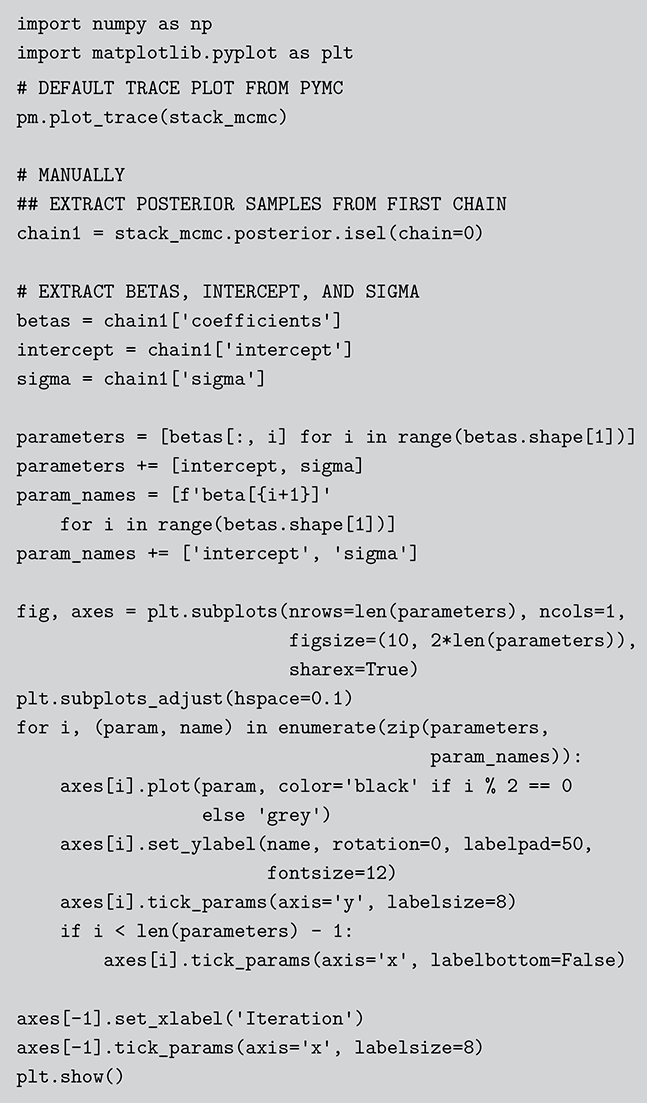

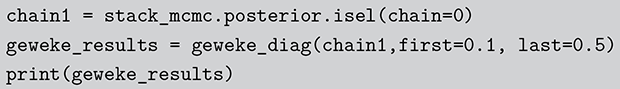

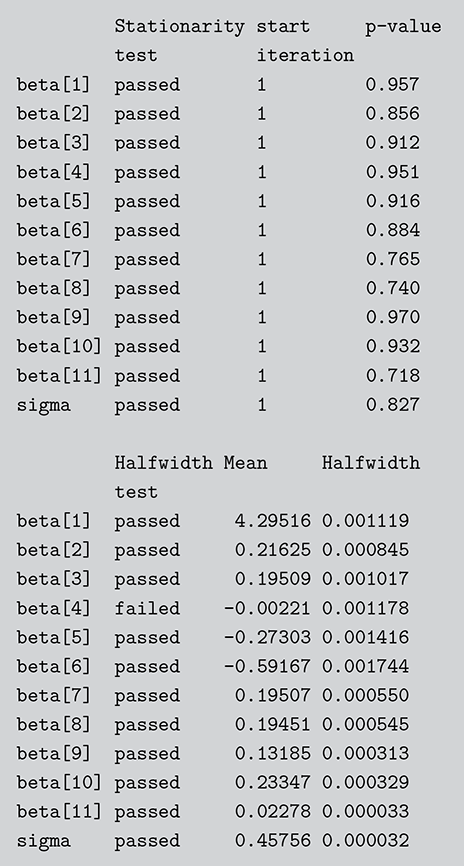

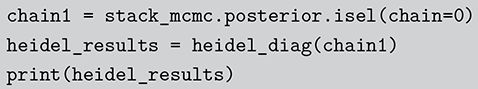

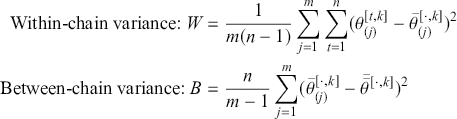

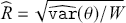

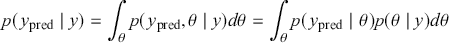

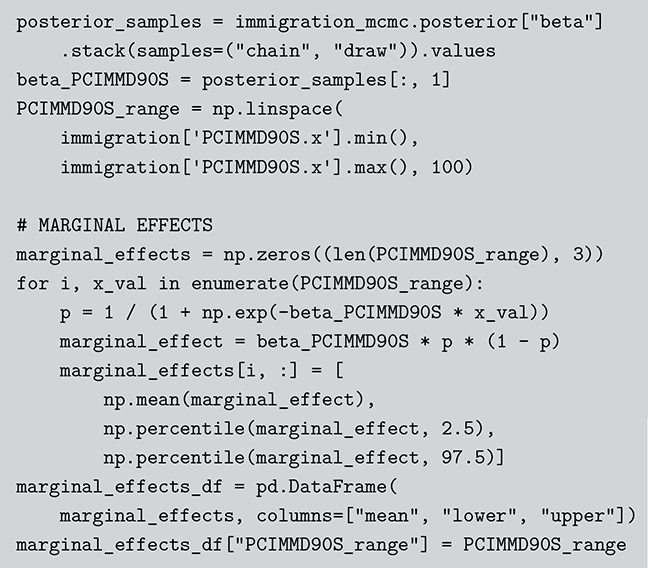

cards but is a lot easier to describe and visualize. With three numbered cards we have a sample space of size ![]() given by