Plain-language summary

Historical documents, such as the archives of the Dutch East India Company, contain invaluable information about the global past. However, these records are often written in older forms of languages, like Early Modern Dutch, which are difficult for most contemporary readers to understand. This research project aimed to solve this problem by training modern artificial intelligence (AI) systems, known as large-language models (LLMs), to accurately translate these historical texts into contemporary English. The goal was to create a reliable and accessible tool that could open these important archives to a broader audience of researchers, historians and the public, without requiring expertise in 17th-century Dutch.

To achieve this, the study used a technique called “fine-tuning.” Rather than building an AI translator from scratch, which is incredibly resource-intensive, existing open-source AI models (like Mistral and Llama 3) were given a specialized training dataset created from translated court testimonies from the Dutch East India Company’s archives in Cochin (Kerala) during 1680–1682 and 1707–1792 (van Rossum et al. Reference van Rossum, Geelen, Van den Hout and Tosun2020). Using two memory-efficient fine-tuning methods called “Unsloth” and “order-reward policy optimization (ORPO)” fine-tuning, this training was conducted on a regular consumer-grade computer, making the process more accessible for other researchers. The results of the fine-tuned models were then compared with other open-source models without specialized training, in addition to GPT-4o, a general-purpose AI that is often used as a standard for LLM performance comparisons.

Success was measured through a two-part evaluation process. First, automated scoring systems (BERTScore and METEOR) were used to compare AI-generated translations with professional human-created translation, measuring accuracy and fluency. Second, a historian specializing in Early Modern Dutch reviewed the translations to assess whether they captured the subtle nuances, legal terminology and historical tone of the original documents.

The findings clearly showed that specialized fine-tuning made a significant difference. The Mistral model fine-tuned with the Unsloth method produced the best results, consistently generating high-quality translations that were not only accurate but also preserved the historical integrity of the source texts. This approach was much more effective than the ORPO method and significantly outperformed the general-purpose models. This research demonstrates a successful and reproducible framework for adapting AI to translate low-resource historical languages, paving the way for making vast archives of historical knowledge more accessible to everyone.

Introduction

Archival records of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie [VOC]) comprise more than five million digitized pages and are recognized by UNESCO as Memory of the World heritage (UNESCO 2003). These documents illuminate colonial trade, slavery, migration and environmental history across Asia, Africa and Australia, yet they are written in early modern Dutch, a historical form that only a relatively small number of specialists can now read with confidence. High-quality, verifiable English translations are therefore conducive for opening this corpus to a global community of scholars and informing public debate.

The GLOBALISE project is constructing an infrastructure that applies handwriting recognition, entity extraction and linked-data enrichment to render the VOC files searchable and machine-readable (GLOBALISE Project 2025). However, without reliable English translations, downstream analyses, such as topic modeling, spatial–temporal mapping or citizen-science annotation, remain inaccessible. Similar challenges arise in other historical translation initiatives, where translation functions as the critical bridge between disciplines, cultures and periods (Deng, Guo, and He Reference Deng, Guo, He, Liu, Malmasi and Xuan2023).

From a natural language processing (NLP) perspective, early modern Dutch diverges from its contemporary counterpart in orthography, syntax and lexicon, and is virtually absent from web-scale pre-training corpora. State-of-the-art large-language models (LLMs) therefore show reduced accuracy in low-resource settings because English-centric pre-training introduces lexical interference and bias. Task-specific adaptation through supervised fine-tuning (SFT) or reward-based alignment can mitigate but not fully resolve these limitations (Terryn and de Lhoneux Reference Terryn and de Lhoneux2024; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Rajabi, Duh, Koehn, Koehn, Barrault and Bojar2023). Crucially, recent parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, such as low-rank adaptation (LoRA), update less than 1 percent of model weights, making domain adaptation feasible on everyday hardware.

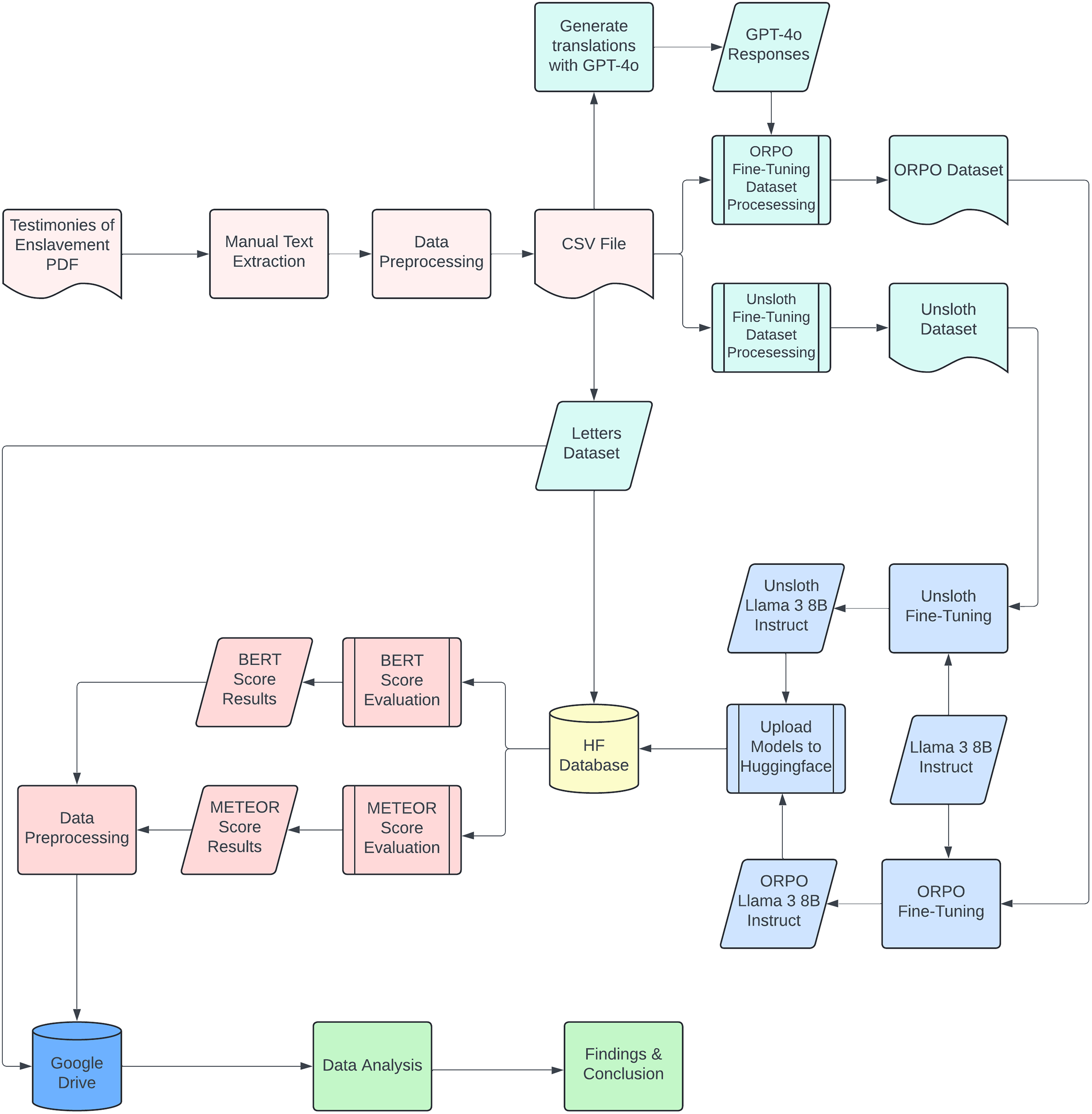

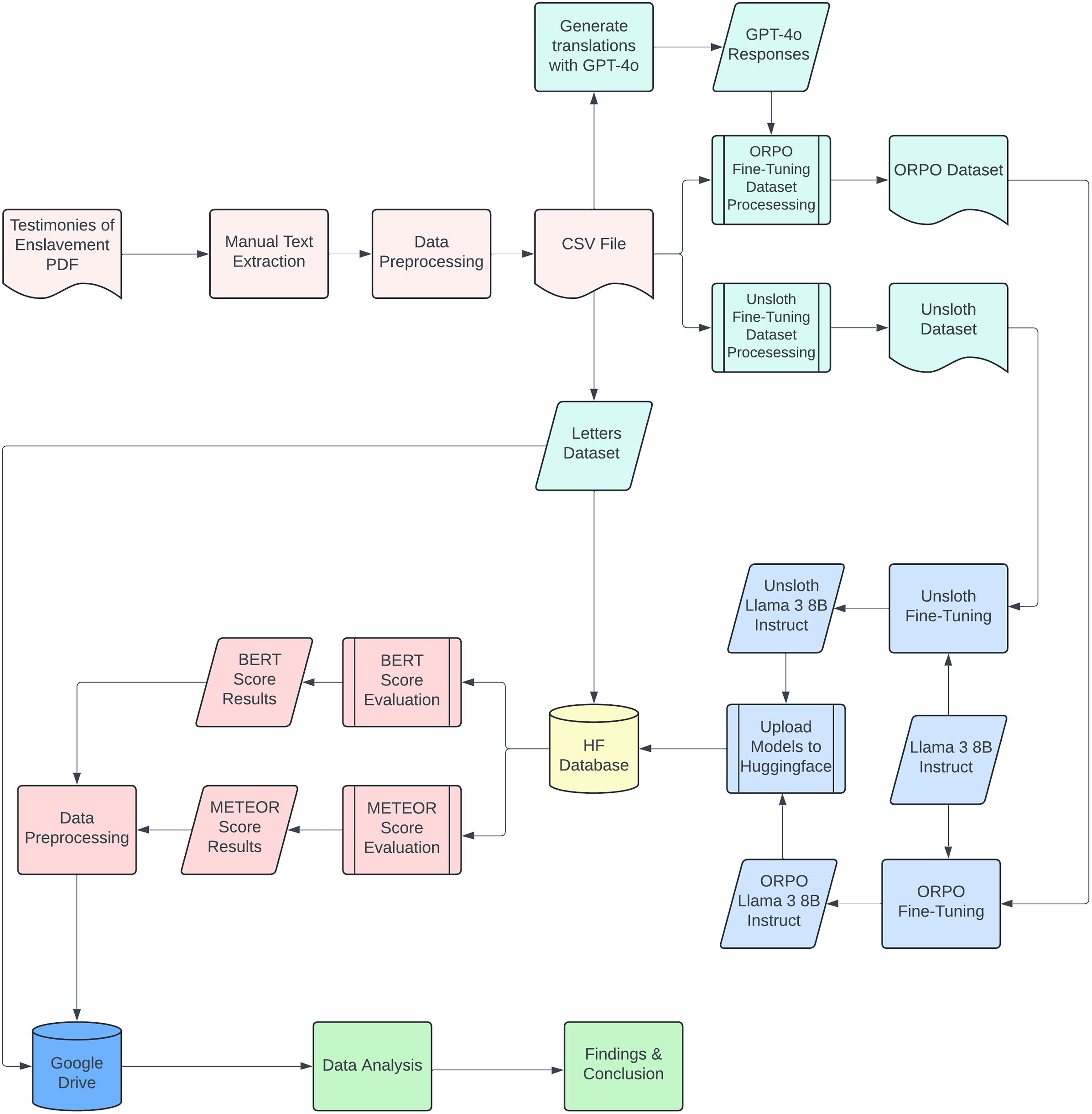

This article outlines a framework; a PEFT workflow combining targeted data augmentation, lightweight fine-tuning and blended automatic–expert evaluation. Such a system can close much of the gap between raw machine output and expert translation for early modern Dutch, thereby rendering the VOC corpus computationally accessible and historically verifiable. To develop such a system, a modular pipeline (Figure 1) is designed that

-

1. augments early modern Dutch coverage via testimonial text data (1680–1792) and custom tokenizer training,

-

2. fine-tunes open LLMs with specialist parallel data using SFT and order-reward policy optimization (ORPO), and

-

3. evaluates the resulting translations with two complementary metrics: BERTScore and METEOR supplemented by expert judgment.

Figure 1. End-to-end training and evaluation pipeline.

The outcome is a repeatable workflow for historical multilingual NLP: a model that renders 17th- and 18th-century Dutch courtroom testimony into modern English with fidelity comparable to human translators while retaining stylistic hallmarks, such as sentence length, register and punctuation.

Background

Current work on early modern Dutch translation intersects three domains: the historical breadth of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) archives, recent progress in domain-specific fine-tuning of LLMs and improvements in subword tokenization that enable LLMs to handle rare orthography and morphology (Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch Reference Sennrich, Haddow, Birch, Erk and Smith2016). The following sections situate the present study within this scholarship.

The Dutch East India Company and the VOC archives

Established in 1602, the VOC dominated early modern maritime commerce and colonial administration, particularly in Asia (Stoler Reference Stoler2002). Its surviving records, millions of pages of correspondence, ledgers and court proceedings, constitute a uniquely detailed source of economic, social and political history (Petram and Van Rossum Reference Petram and Van Rossum2022). Although large-scale digitization has facilitated access (Manjavacas and Fonteyn Reference Manjavacas and Fonteyn2022) to these records, computational use of the corpus remains limited because the material is written in early modern Dutch. The variety diverges markedly from the present Dutch in vocabulary, syntax and idiom (Jiang and Zhang Reference Jiang and Zhang2024), and there is no large bilingual corpus to train conventional neural-machine translation (NMT) systems (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Zhang, Geng, Yichao, Chen, Huang, Lun-Wei, Martins and Srikumar2024). Specialized fine-tuning of multilingual LLMs therefore offers a promising, but still underexplored, pathway to research accessibility.

Testimonies of Enslavement

“Testimonies of Enslavement” comprises English translations of court cases heard by the VOC’s Court of Justice in Cochin (Kerala) during 1680–1682 and 1707–1792 (van Rossum et al. Reference van Rossum, Geelen, Van den Hout and Tosun2020). This unique collection presents parallel texts in Dutch, Portuguese, Latin and local languages, systematically expanding historical abbreviations while preserving culturally specific legal and administrative terms that resist literal translation, precisely the linguistic challenges that complicate automated translation of Early Modern Dutch. The corpus’s digitization includes detailed metadata covering case type, date, thematic tags and personal attributes, such as gender or legal status, making it a benchmark for studying slavery, migration and cross-cultural jurisprudence. Most critically for machine translation (MT) research, the collection’s sentence-aligned parallel structure provides the expert-curated bilingual data essential for fine-tuning and evaluating historical translation models, bridging the gap between raw archival material and the structured datasets required for NMT.

Fine-tuning LLMs for specialized translation

MT remains a flagship application of transformer-based LLMs (Vaswani et al. Reference Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Guyon, von Luxburg, Bengio, Wallach, Fergus, Vishwanathan and Garnett2017). NMT systems outperform earlier rule-based and statistical approaches because they learn cross-lingual patterns from large parallel corpora (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Zhang, Geng, Yichao, Chen, Huang, Lun-Wei, Martins and Srikumar2024). A full fine-tune updates every weight in a multi-billion-parameter network, which demands expensive hardware. PEFT instead adjusts only a tiny slice of the model (often <1%), so researchers can adapt an LLM on a laptop-grade GPU while leaving the core weights untouched. Fine-tuning adapts these general models to low-resource historical domains through two successive steps:

-

1. Instruction tuning – also called SFT, exposes the model to curated sentence pairs so that it acquires the orthography, vocabulary and syntax of early modern Dutch.

-

2. Preference alignment reshapes the model’s output style using human feedback. Popular methods include reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) (Ouyang et al. Reference Ouyang, Jeff, Jiang, Alice, Naumann, Globerson, Saenko, Hardt and Levine2022), direct preference optimization (DPO) (Rafailov et al. Reference Rafailov, Sharma, Mitchell, Ermon, Manning, Finn, Alice, Naumann, Globerson, Saenko, Hardt and Levine2023), lightweight LoRA adapters (LoRA adds a small trainable matrix to each layer, enabling parameter-efficient updates.) (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Shen, Wallis, Allen-Zhu, Li, Wang, Lu and Chen2022) and ORPO (Hong, Lee, and Thorne Reference Hong, Lee, Thorne, Salakhutdinov, Kolter and Heller2024).

Combined, these stages yield a translator that preserves historical nuance while meeting present-day quality expectations.

Unsloth supervised fine-tuning

The first pipeline employs the Unsloth library, a wrapper around Hugging Face’s transformers library that integrates PEFT modules (Unsloth AI 2024; Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Debut, Sanh, Liu and Schuurmans2020). Unsloth accelerates training by fusing key matrix operations, re-ordering attention kernels and streaming gradients directly between CPU and GPU. On a single consumer GPU, it cuts training time by up to two times and memory usage by roughly 70 percent with no measurable loss in accuracy. It supports recent open models lines, such as Llama, Mistral, Phi and Gemma.

ORPO preference alignment

ORPO augments the language-model loss with an odds-ratio term that mildly penalizes rejected responses and strongly rewards preferred ones (Hong, Lee, and Thorne Reference Hong, Lee, Thorne, Salakhutdinov, Kolter and Heller2024). This regularization balances task learning and human alignment, improving generalization to previously unseen early modern Dutch inputs.

Machine translation

MT enables automatic transfer of text across languages and is indispensable for unlocking historical sources (Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch Reference Sennrich, Haddow, Birch, Erk and Smith2016). Recent advances in NMT have markedly improved adequacy and fluency, even for linguistically complex and culturally embedded material such as early modern Dutch (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Ma, Lin, Callan, Rogers, Boyd-Graber and Okazaki2022).

Three methodological stages frame the field:

-

1. Rule-based MT: Hand-crafted transfer rules and bilingual lexicons performed reliably in restricted domains, but proved brittle with orthographic variation, archaic morphology and long-distance dependencies (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Hua, He, Huang and Church2022).

-

2. Statistical MT: Word and phrase-based probabilistic models (Brown, Della, and Pietra Reference Brown, Della and Pietra1993; Lopez Reference Lopez2008) replaced rules with corpus statistics, improving robustness but still struggling with reordering and rich morphology: complex inflectional patterns where words change form for grammatical functions, creating numerous variants that fragment translation probabilities.

-

3. NMT: Sequence-to-sequence architectures with attention (Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio Reference Bahdanau, Cho, Bengio, Bengio and LeCun2015), culminating in the Transformer (Vaswani et al. Reference Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Guyon, von Luxburg, Bengio, Wallach, Fergus, Vishwanathan and Garnett2017), delivered large leaps in quality. Sub-word segmentation (Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch Reference Sennrich, Haddow, Birch, Erk and Smith2016) and massively multilingual pre-training (Aharoni, Johnson, and Firat Reference Aharoni, Johnson, Firat, Burstein, Doran and Solorio2019; Zhang and Sennrich Reference Zhang, Sennrich, Jurafsky, Chai, Schluter and Tetreault2020) further widened language coverage.

Unlike traditional MT systems that are explicitly trained on parallel corpora for translation tasks, contemporary LLMs acquire translation capabilities emergently through their general language modeling objectives. While specialized NMT systems remain optimized for translation quality, LLMs offer a more flexible approach that can handle multiple tasks, including translation, within a single model architecture. This study bridges these paradigms by adapting general-purpose LLMs to specialized historical translation through PEFT, combining the flexibility of LLMs with the domain specificity of traditional MT approaches.

-

• Full fine-tuning updates every parameter, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy but incurring high memory cost and risking catastrophic forgetting.

-

• PEFT freezes the backbone and trains lightweight modules – adapters (Houlsby et al. Reference Houlsby, Giurgiu, Jastrzebski, Morrone, De Laroussilhe, Gesmundo, Attariyan, Gelly, Chaudhuri and Salakhutdinov2019), prefix-tuning (Li and Liang Reference Li, Liang, Zong, Xia, Li and Navigli2021) or LoRA matrices (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Shen, Wallis, Allen-Zhu, Li, Wang, Lu and Chen2022) that reduce compute without sacrificing quality.

LLMs offer two further advantages for historical MT: (i) zero- or few-shot performance on extremely low-resource pairs and (ii) unified multitask capability translation, summarization and extraction in one model. This study therefore tests two PEFT strategies, Unsloth SFT and ORPO, to inject early modern Dutch expertise into open-source LLMs while keeping training and inference budgets modest. The resulting models are benchmarked with embedding-based metrics that reward semantic fidelity and stylistic precision.

Translation evaluation

Given the complexity and historical significance of translating early modern Dutch texts, accurate evaluation is crucial. This study scores system outputs with two automatic metrics chosen for their ability to capture semantic adequacy and fluency:

(i) BERTScore (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Kishore and Felix2020), a semantic-similarity metric that leverages contextual embeddings to gauge how closely a hypothesis preserves the reference meaning, an essential property for historically nuanced material.

(ii) METEOR (Banerjee and Lavie Reference Banerjee, Lavie, Goldstein, Lavie, Lin and Voss2005; Denkowski and Lavie Reference Denkowski, Lavie, Bojar, Buck, Federmann, Haddow, Koehn, Leveling, Monz, Pecina, Post, Saint-Amand, Soricut, Specia and Tamchyna2014), which aligns tokens at the exact, stem, synonym and paraphrase levels to balance lexical richness, fluency and stylistic authenticity.

Together these metrics overcome tokenization mismatches and length bias that affect traditional n-gram measures such as BLEU (Papineni et al. Reference Papineni, Roukos, Ward, Zhu and Isabelle2002; Post Reference Post2018), aligning with the goal of robust, historically-aware MT evaluation.

BERTScore

BERTScore compares a candidate sentence

![]() $C=\{c_1,\dots ,c_{|C|}\}$

with a reference sentence

$C=\{c_1,\dots ,c_{|C|}\}$

with a reference sentence

![]() $R=\{r_1,\dots ,r_{|R|}\}$

in a contextual-embedding space. Each token is encoded by the multilingual bert-base-multilingual-cased model (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee, Toutanova, Burstein, Doran and Solorio2019) (layer 8 by default). Cosine similarities form the matrix

$R=\{r_1,\dots ,r_{|R|}\}$

in a contextual-embedding space. Each token is encoded by the multilingual bert-base-multilingual-cased model (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee, Toutanova, Burstein, Doran and Solorio2019) (layer 8 by default). Cosine similarities form the matrix

![]() $S_{ij}=\cos \!\bigl (\mathbf {e}(c_i),\mathbf {e}(r_j)\bigr )$

. Keeping the maximum similarity for each token yields

$S_{ij}=\cos \!\bigl (\mathbf {e}(c_i),\mathbf {e}(r_j)\bigr )$

. Keeping the maximum similarity for each token yields

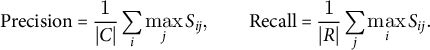

$$\begin{align*}\text{Precision}= \frac{1}{|C|}\sum_{i}\max_j S_{ij}, \qquad \text{Recall}= \frac{1}{|R|}\sum_{j}\max_i S_{ij}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\text{Precision}= \frac{1}{|C|}\sum_{i}\max_j S_{ij}, \qquad \text{Recall}= \frac{1}{|R|}\sum_{j}\max_i S_{ij}. \end{align*}$$

The harmonic mean gives the final score,

after inverse-document-frequency weighting that down-weights very common words. Sentence-level scores are averaged to produce the system-level values reported in the “Results” section (range 0–1, where 1 denotes identical meaning).

METEOR

METEOR aligns hypothesis and reference tokens via exact, stem, synonym and paraphrase matches (Banerjee and Lavie Reference Banerjee, Lavie, Goldstein, Lavie, Lin and Voss2005). Let m be the number of matched tokens; precision (P) and recall (R) are

Fragmentation incurs a penalty,

yielding a score between 0 and 1. We use METEOR v1.5 (SacreBLEU implementation) with the English WordNet synonym list and the paraphrase table of Denkowski and Lavie (Reference Denkowski, Lavie, Bojar, Buck, Federmann, Haddow, Koehn, Leveling, Monz, Pecina, Post, Saint-Amand, Soricut, Specia and Tamchyna2014).

Tokenization

Tokenization is the initial parsing step in most NLP pipelines: It segments raw text into words, subwords or bytes that LLMs can process (Mielke et al. Reference Mielke, Alyafeai and Salesky2021). For multilingual or historical LLMs, the chosen scheme directly influences how well the network captures vocabulary, morphology and syntax (Kudo and Richardson Reference Kudo, Richardson, Blanco and Lu2018; Manjavacas and Fonteyn Reference Manjavacas and Fonteyn2022; Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch Reference Sennrich, Haddow, Birch, Erk and Smith2016); translation quality therefore hinges on tokenization fidelity (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Jain, Elmoznino, Kaddar, Lajoie, Bengio and Malkin2024).

Efficient tokenizers compress more information into each context window, reducing training time and inference cost (Jiang and Zhang Reference Jiang and Zhang2024). Early modern Dutch, however, exhibits variable spelling, archaic graphemes and mixed scripts that tokenizers optimized for present-day corpora often fragment. The resulting high out-of-vocabulary (OOV) rates lengthen sequences, split morpho-syntactic units and depress model performance (Manjavacas and Fonteyn Reference Manjavacas and Fonteyn2022; Mielke et al. Reference Mielke, Alyafeai and Salesky2021). Targeted vocabulary augmentation and bespoke subword training are, therefore, prerequisites for accurate translation and analysis of historically significant documents. In this study, a custom tokenizer was developed to show what optimal processing of our source corpus would look like, the performance of which is reported as part of the methodological setup.

Data methods

Specialized data procedures were required at all stages of the pipeline (Figure 1), including extraction, cleaning, corpus construction and evaluation.

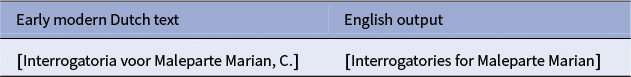

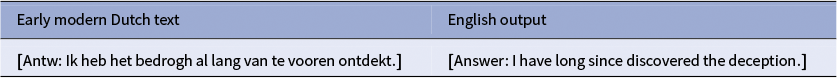

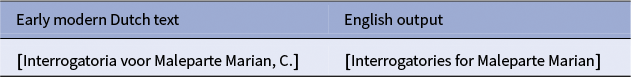

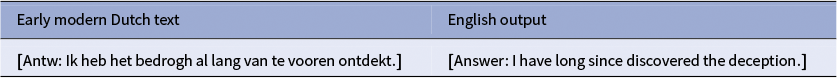

Early modern Dutch source sentences and their English renderings were transcribed from VOC Court-of-Justice testimonies recorded in Cochin (Kerala) for 1680–1682 and 1707–1792 (van Rossum et al. Reference van Rossum, Geelen, Van den Hout and Tosun2020). Because published PDFs contain complex layouts, the sentences were manually copied into a two-column comma-separated file comprising 1,281 aligned pairs.

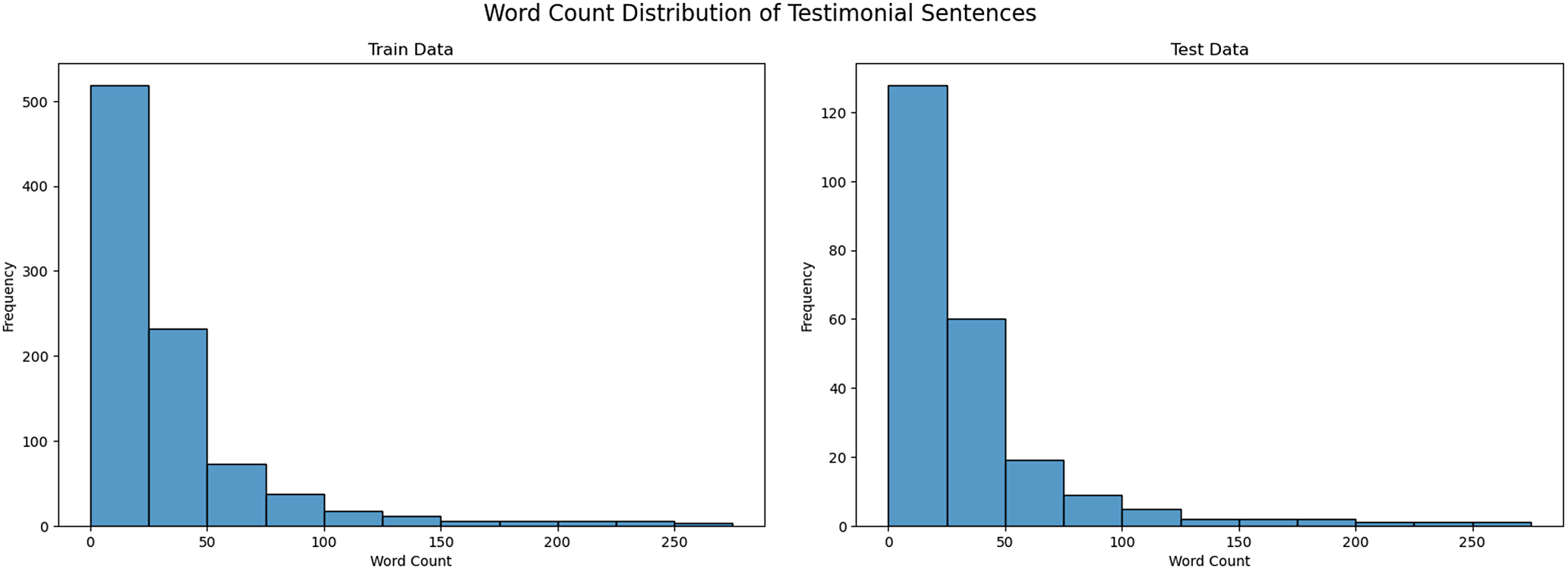

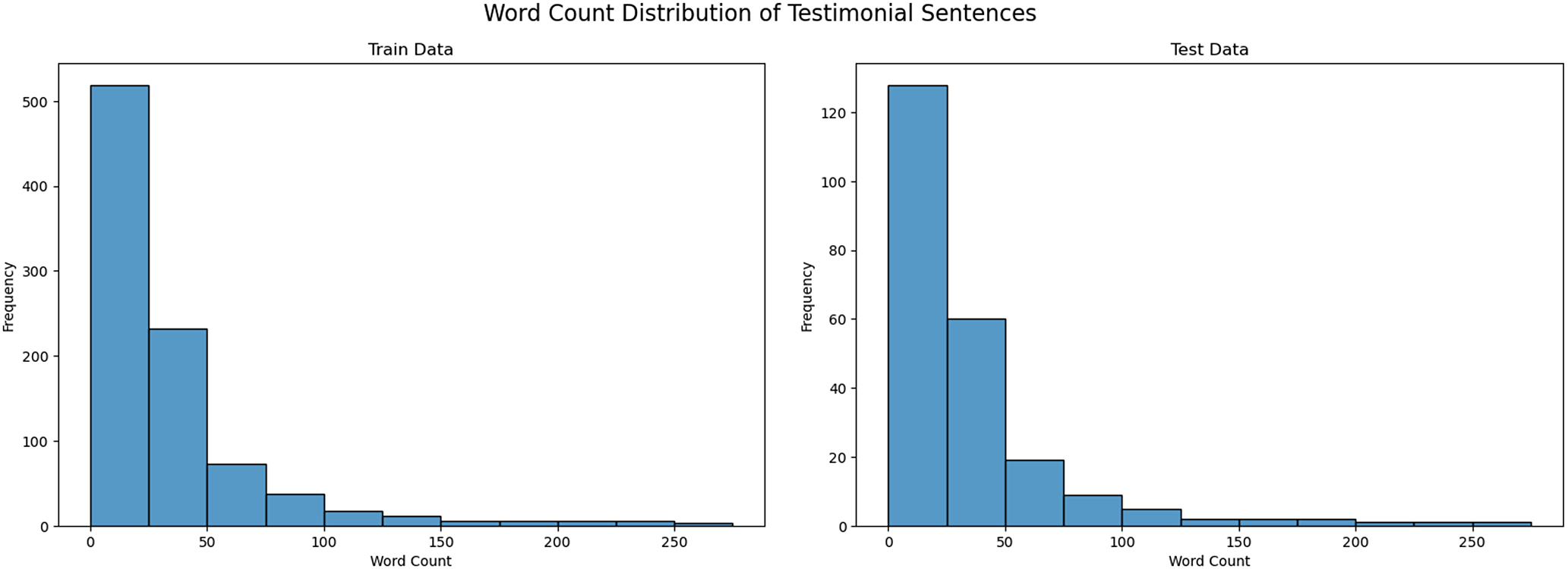

The exploratory graphs showed that both Dutch and English sentences were typically shorter than 300 words (Figure 2); the frequency of sentences greater than 300 words declined significantly beyond that limit. After stripping extra whitespace, line breaks and other artifacts with Python regular expression scripts, we discarded pairs containing fewer than five or more than 300 tokens and split the remainder into training and test sets (80% and 20%, respectively).

Figure 2. Word-count distribution for early modern Dutch sentences in the training and test splits.

Alignment corpora: The training split was duplicated to create two datasets: one for Unsloth SFT and one for ORPO fine-tuning (Hong, Lee, and Thorne Reference Hong, Lee, Thorne, Salakhutdinov, Kolter and Heller2024). ORPO requires a chosen/rejected format, so expert translations filled the chosen slots while GPT-4o outputs with identical prompts populated the rejected column (OpenAI 2024).

Consolidation and cleaning: Model outputs were stored separately and then merged so that each row contained (i) the Dutch source with word count and case ID, (ii) the expert reference, and (iii) each system’s hypothesis. Residual anomalies (e.g., stray brackets) were removed before saving the consolidated file.

BERTScore and METEOR (“Translation evaluation” section) were computed for every hypothesis–reference pair. System-level statistics were exported as .csv files for subsequent analysis.

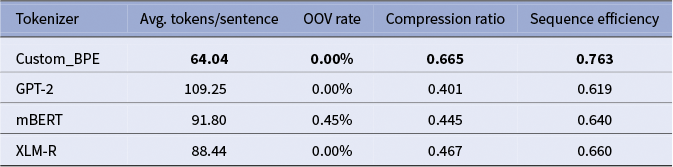

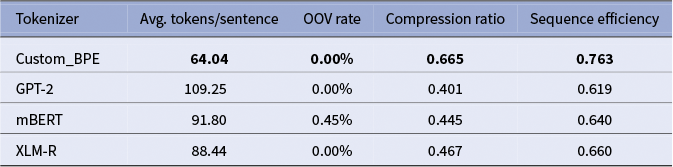

Tokenizer implementation

To mitigate the issues of orthographic fragmentation outlined in the “Tokenization” section, a custom byte-pair encoding (BPE) tokenizer was trained on the Early Modern Dutch corpus. This step served as a foundational preprocessing measure to ensure the subsequent fine-tuning models could efficiently process the historical texts. Its performance was compared against several standard tokenizers (GPT-2, mBERT, and XLM-R) on the test set. As shown in Table 1, the custom tokenizer achieved an impressive OOV coverage in contrast to other tokenizers and the highest sequence efficiency, representing the source texts in the fewest number of tokens. This optimization reduced computational overhead and potential context fragmentation during the fine-tuning and inference stages.

Table 1. Tokenizer performance comparison on early modern Dutch

Model evaluation methods

This study combines two automatic metrics, BERTScore and METEOR, with a qualitative review by a specialist in early modern Dutch. (For metric definitions, see the “Translation evaluation” section.) To validate the effectiveness of our fine-tuning approach, we employed a comparative framework that contrasted adapted models against their base (unfine-tuned) versions, supplemented by domain expert evaluation. This dual validation strategy ensured that performance gains resulted from targeted adaptation rather than general model capabilities.

Automatic scores quantified semantic adequacy and fluency across all systems, while expert judgment specifically assessed whether fine-tuned models better preserved historical nuance compared to their base counterparts (Freitag et al. Reference Freitag, Rei, Mathur, Lo, Stewart, Avramidis, Kocmi, Foster, Lavie, Martins, Koehn, Barrault, Bojar, Bougares, Chatterjee, Federmann, Fishel, Fraser, Freitag and Grundkiewicz2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Kishore and Felix2020). BERTScore and METEOR were computed against reference translations prepared by scholars at Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia and the Corts Foundation (van Rossum et al. Reference van Rossum, Geelen, Van den Hout and Tosun2020). The domain specialist reviewed parallel outputs from base and fine-tuned models, focusing on preservation of legal terminology, historical context and documentary authenticity.

This comprehensive evaluation framework, combining quantitative comparisons between base and adapted models with qualitative domain expertise, ensured that performance improvements reflected genuine enhancements in historical translation quality rather than metric optimization alone.

Testing environment

All inference ran in Google Colab on NVIDIA L4 and A100 GPUs via a custom notebook. (Notebook archive: https://anony mous.4open.science/r/EMDutchLLMFinetuneA67B.) Each model received a one-shot prompt consisting of (i) an instruction to render an early modern Dutch sentence in contemporary English under specified guidelines and (ii) the sentence itself (Lip Reference Lip2025). Generation parameters were fixed across systems: do_sample=True, num_beams=5, penalty_alpha=0.6. The models translated 230 sentences from 18th-century court cases; outputs were written to CSV for subsequent scoring.

Quantitative benchmark

Python implementations of BERTScore and METEOR (Lip Reference Lip2025) produced scores for every hypothesis–reference pair. BERTScore captures sentence-level semantic similarity, while METEOR assesses lexical choice, phrase alignment and fluency. Their conjunction provides a more complete picture of translation quality than either metric alone.

Qualitative benchmark

For the qualitative benchmark, a domain expert performed a systematic review of all 230 test sentences across all model outputs. Rather than aiming for “perfect” automated translations – an unrealistic goal given the complexity of historical texts – our framework positions model outputs as preliminary drafts for expert refinement. In practice, historians would work with these imperfect translations, using them as starting points that significantly accelerate the traditional translation process while maintaining scholarly oversight.

Training

Two fine-tuning strategies were applied to the testimonial corpus (see the “Data methods” section): SFT implemented with the Unsloth parameter-efficient library (Unsloth AI 2024); and ORPO (Hong, Lee, and Thorne Reference Hong, Lee, Thorne, Salakhutdinov, Kolter and Heller2024).

Base models

Experiments start from publicly available, instruction-tuned checkpoints:

-

• Llama-3-8B (Meta) – SFT and ORPO;

-

• Llama-2-7B (Meta) – SFT;

-

• Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3 (MistralAI) – SFT;

-

• TinyLlama-1.1B – SFT.

Compute environment

Fine-tuning was performed in Google Colab Pro on NVIDIA L4 (24 GB) and A100 (40 GB) GPUs. Notebooks and configuration files are archived in the project repository (Lip Reference Lip2025). Training curves were logged to Weights and Biases for real-time monitoring (Biewald Reference Biewald2020).

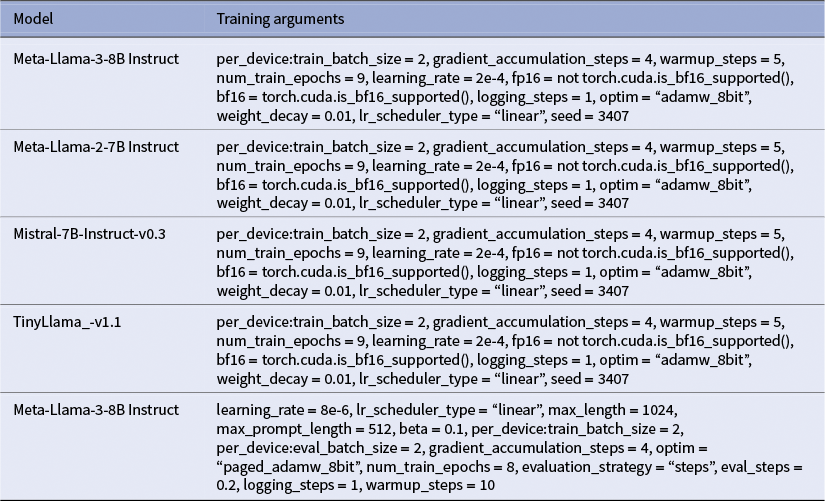

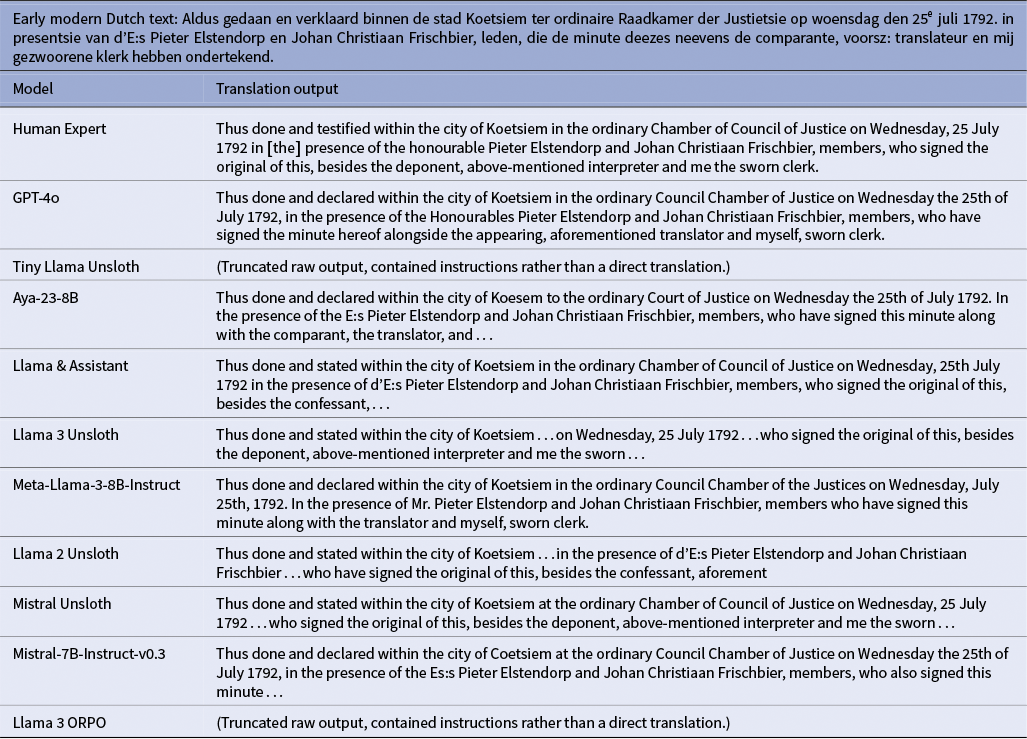

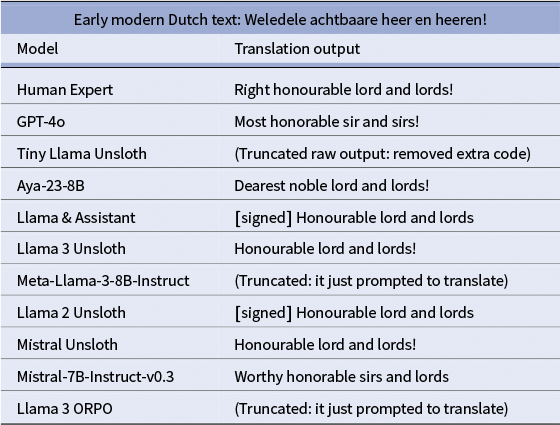

Hyper-parameters

All runs use an accumulative batch size of 64 and a maximum sequence length of 512 tokens. For the full parameter list for each model, see Table A6.

-

• SFT (Unsloth): Nine epochs, AdamW optimizer, learning rate

$2\times 10^{-4}$

,

$2\times 10^{-4}$

,

$\beta _{1}=0.9$

,

$\beta _{1}=0.9$

,

$\beta _{2}=0.999$

.

$\beta _{2}=0.999$

. -

• ORPO: Eight epochs, AdamW optimizer, learning rate

$1\times 10^{-5}$

, same

$1\times 10^{-5}$

, same

$\beta $

values, KL-divergence weight

$\beta $

values, KL-divergence weight

$0.02$

.

$0.02$

.

Results

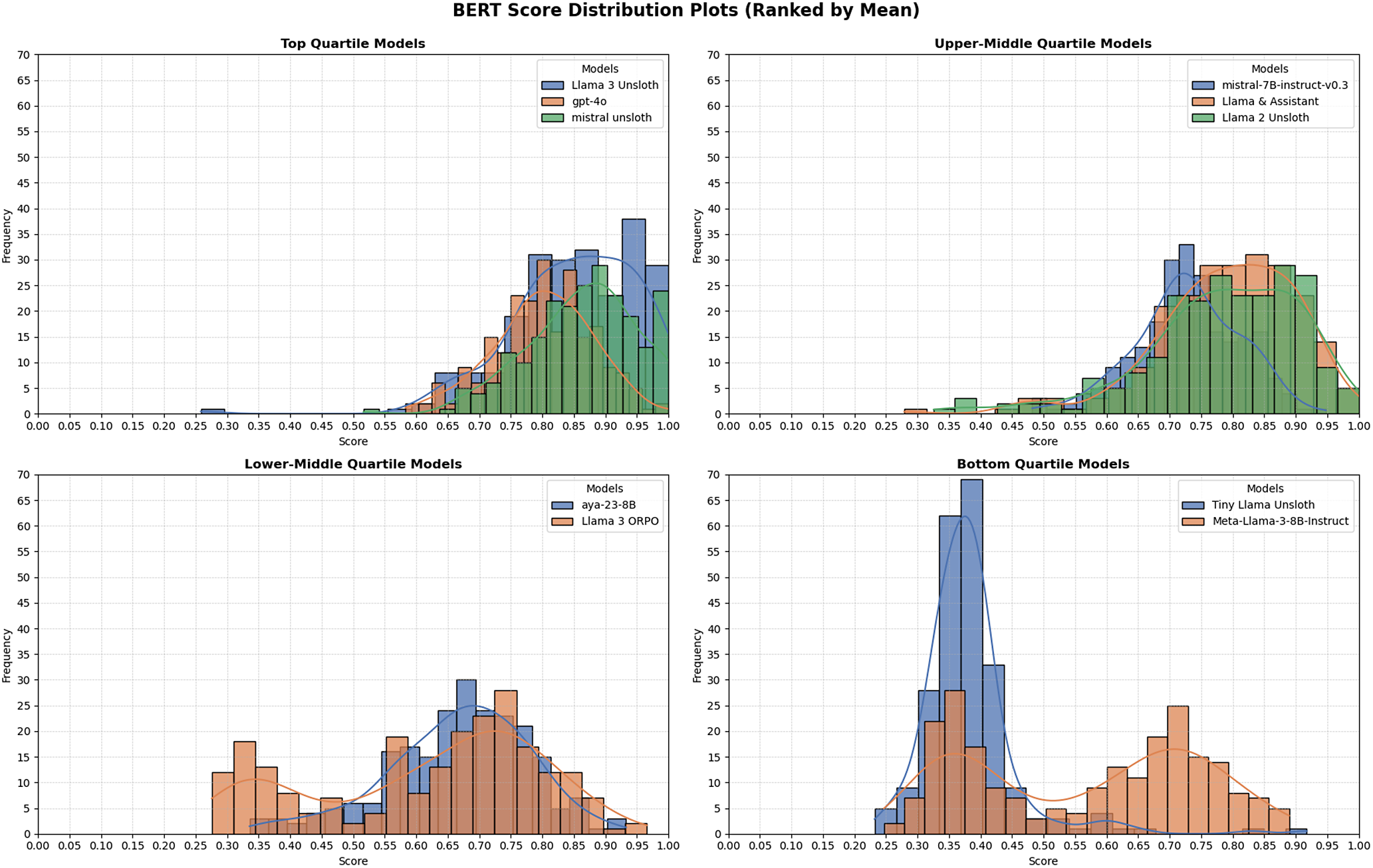

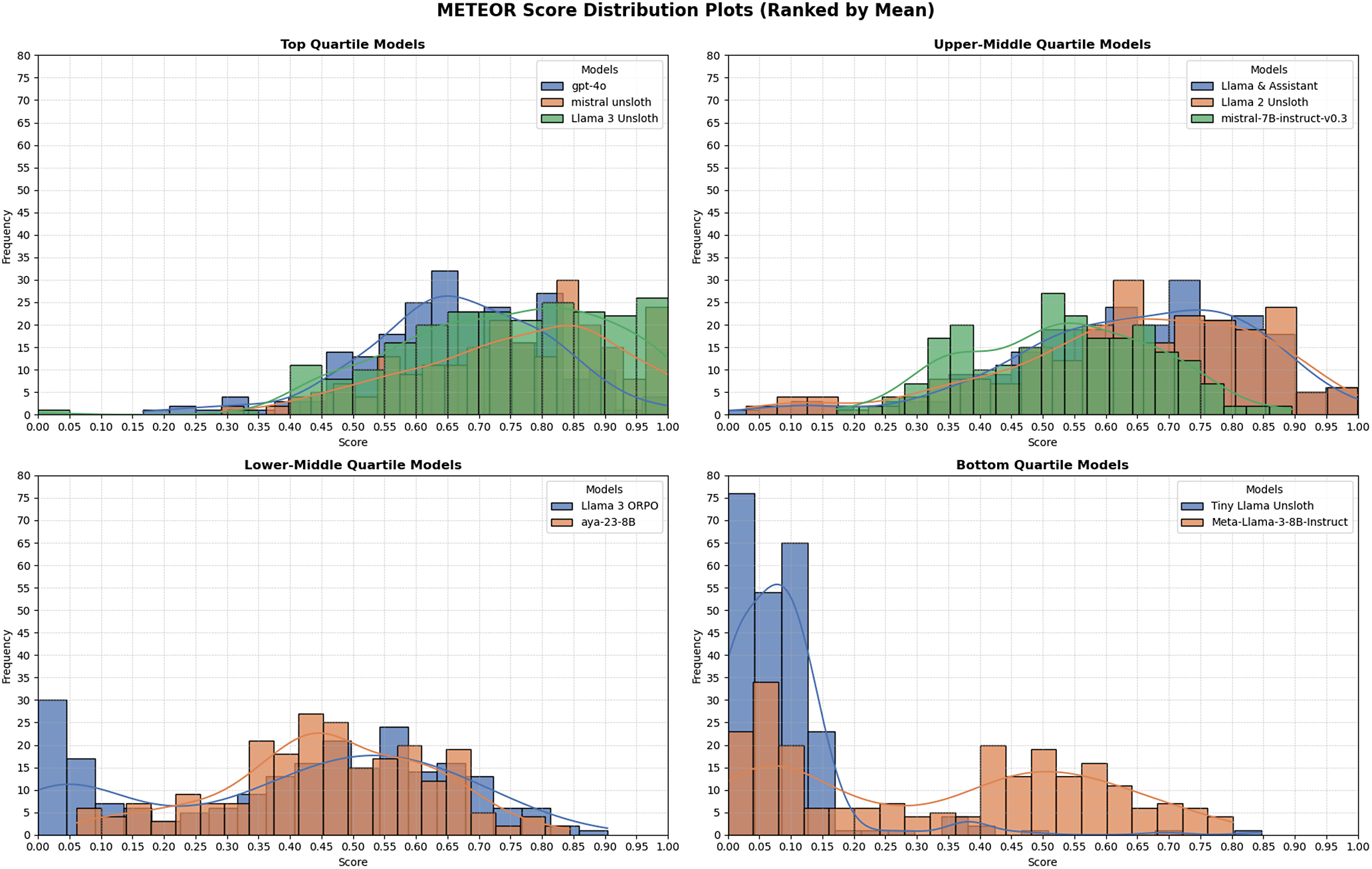

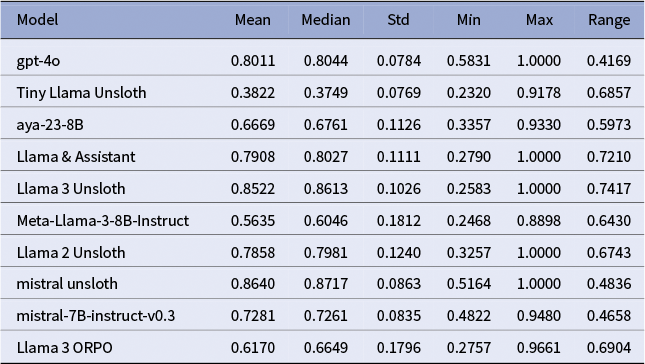

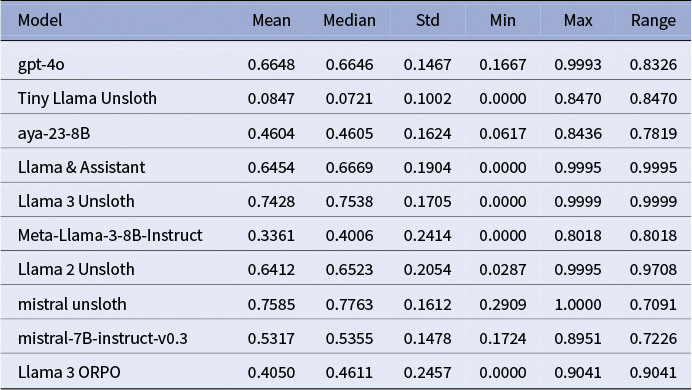

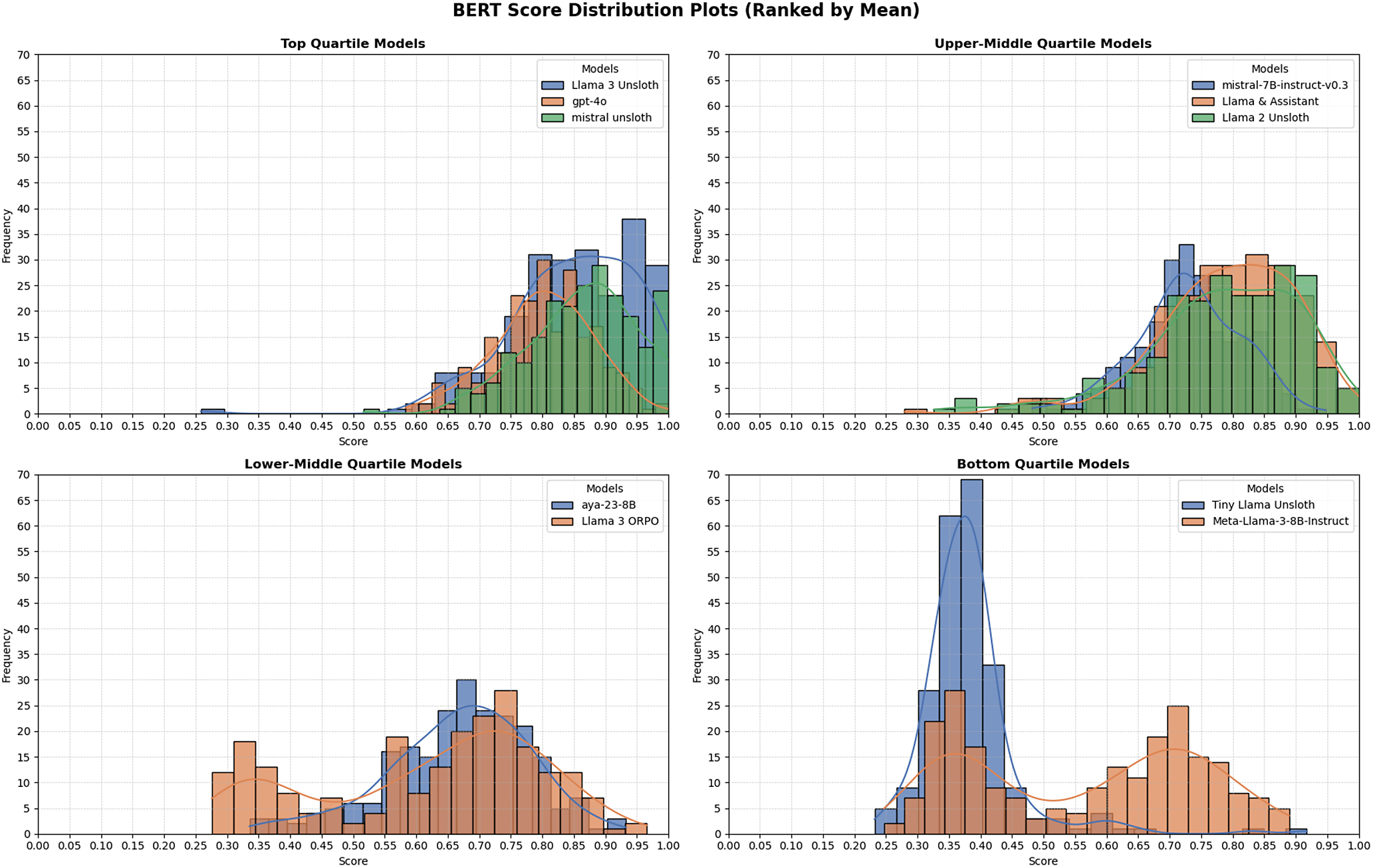

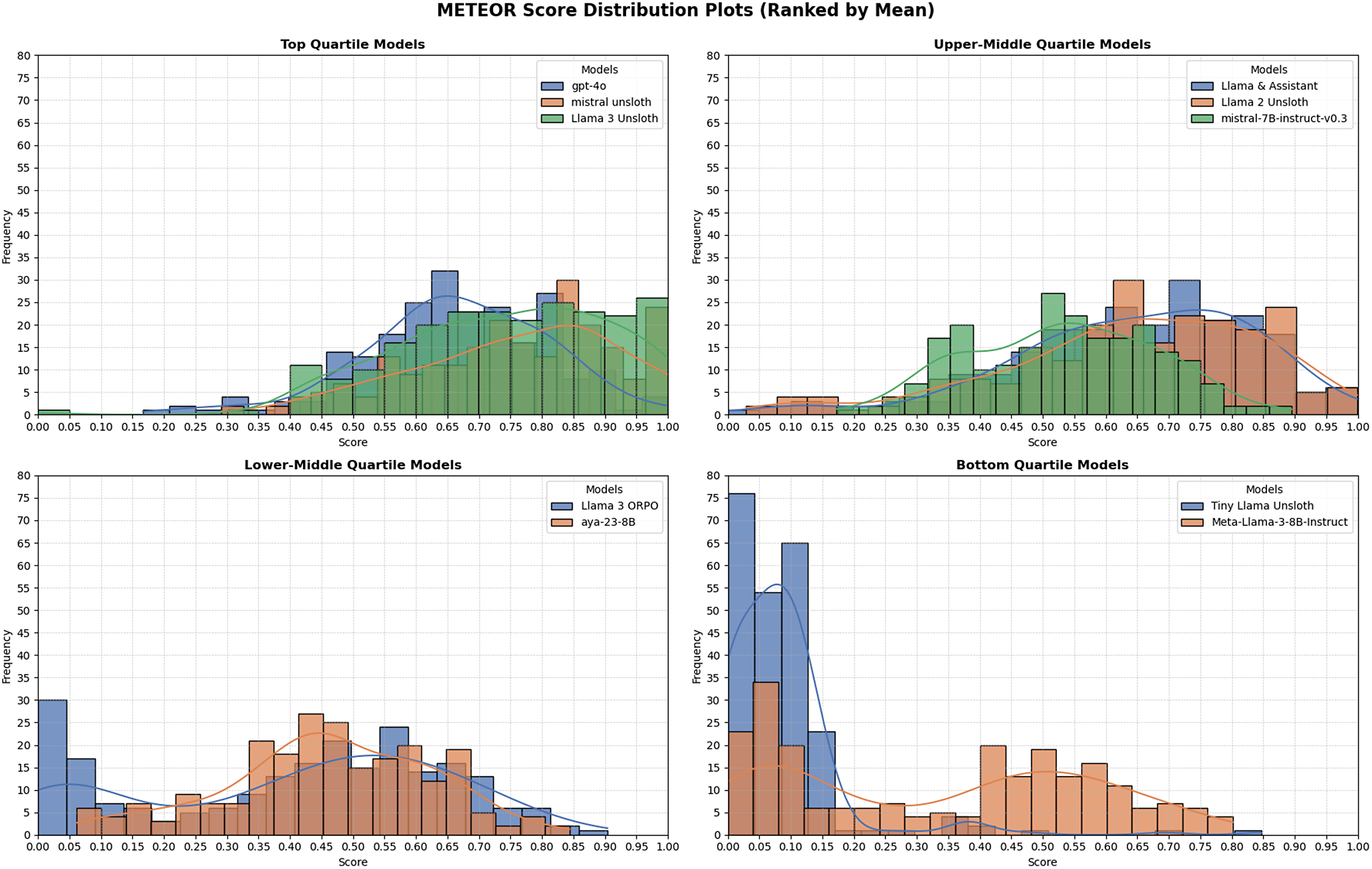

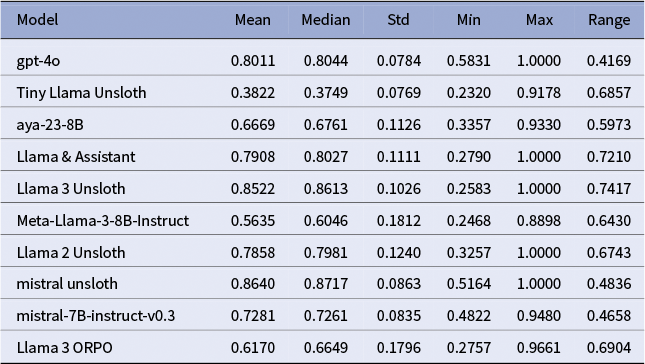

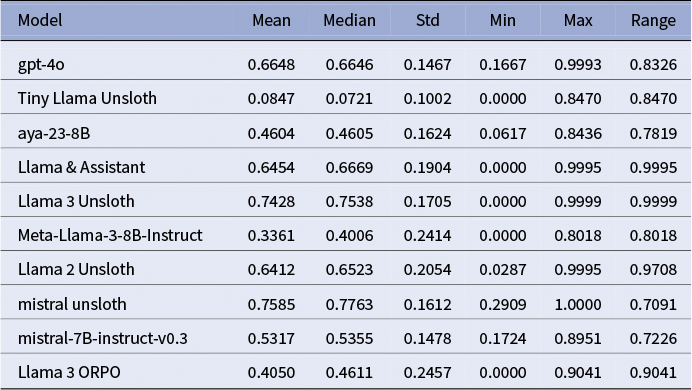

High-performing models

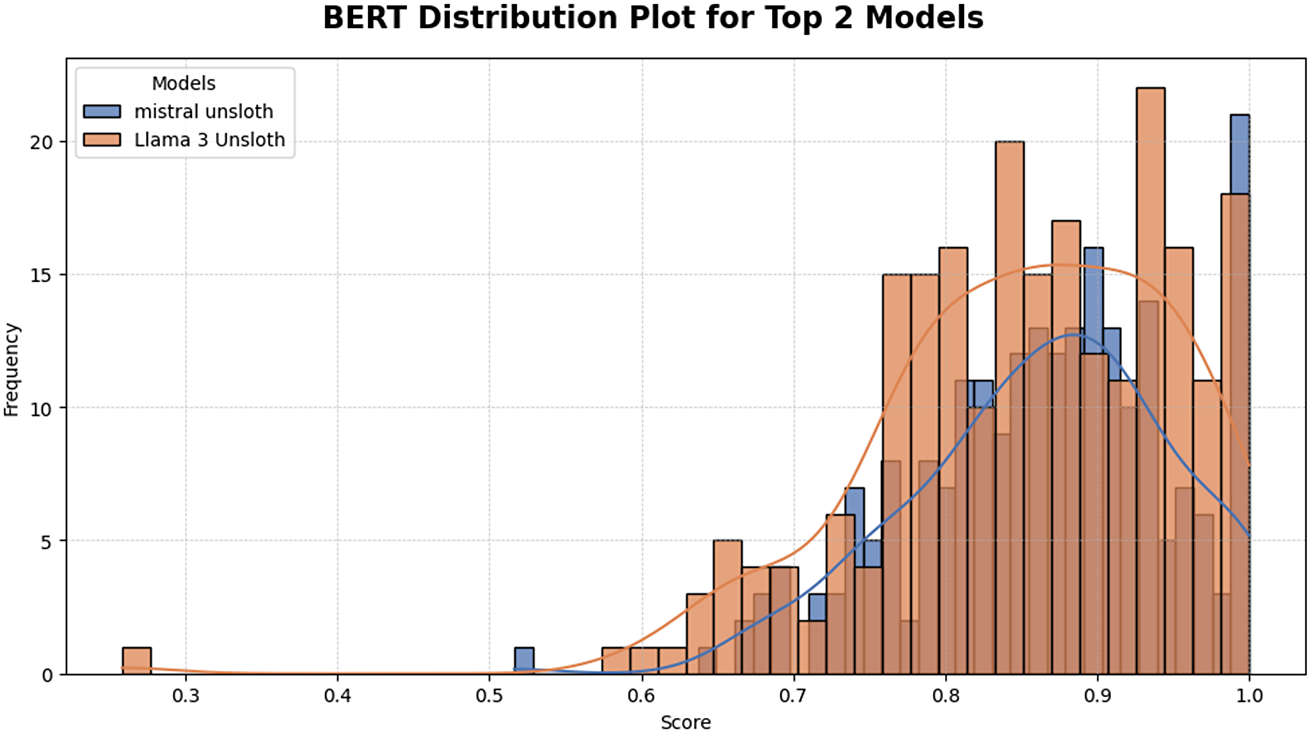

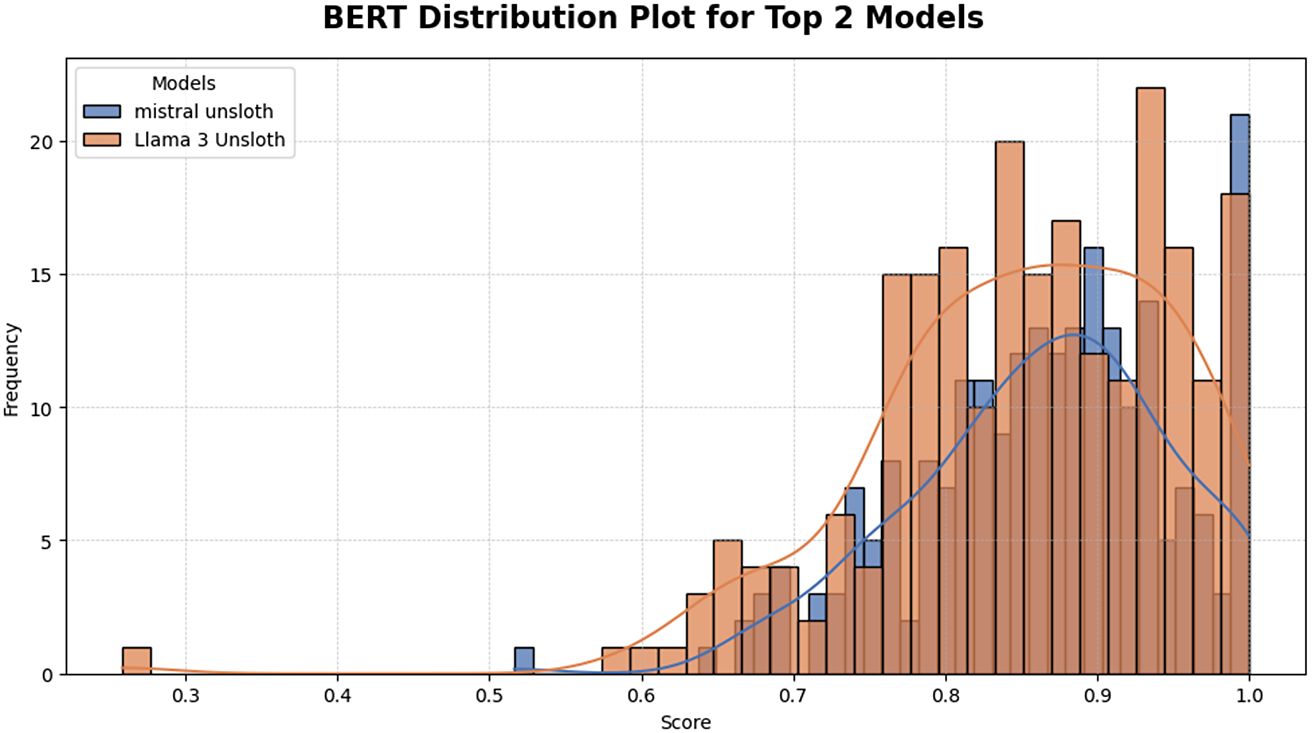

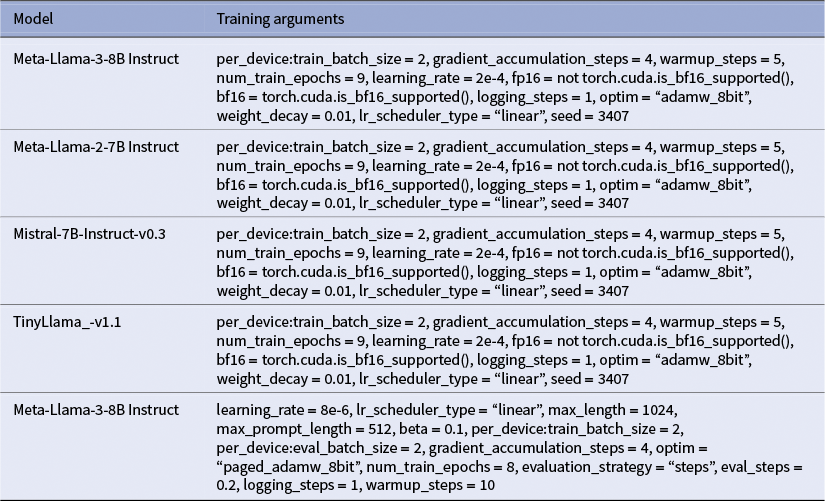

The three best systems were (i) Mistral-7B-Instruct fine-tuned with Unsloth, (ii) Llama-3-8B-Instruct with Unsloth, and (iii) GPT-4o. Mistral-Unsloth obtained the highest mean and median on both BERTScore and METEOR, with the narrowest inter-quartile range (Tables A10 and A11, marking it as the most reliable translator for early modern Dutch. Llama-3-Unsloth produced comparably high scores but showed slightly greater spread, while GPT-4o delivered a strong, untuned baseline.

GPT-4o required no additional training yet consistently approached expert quality: its low metric variance indicates robustness across sentence length and syntactic complexity (Table A10). Although it seldom tops individual metrics, its “plug-and-play” reliability makes it a practical benchmark when fine-tuning resources are scarce.

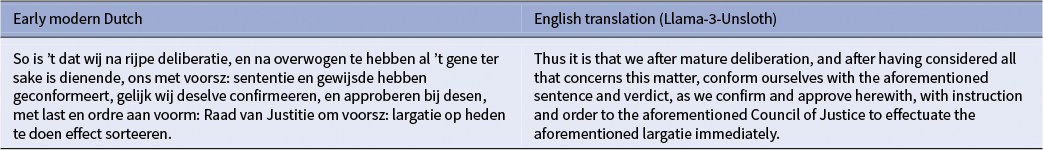

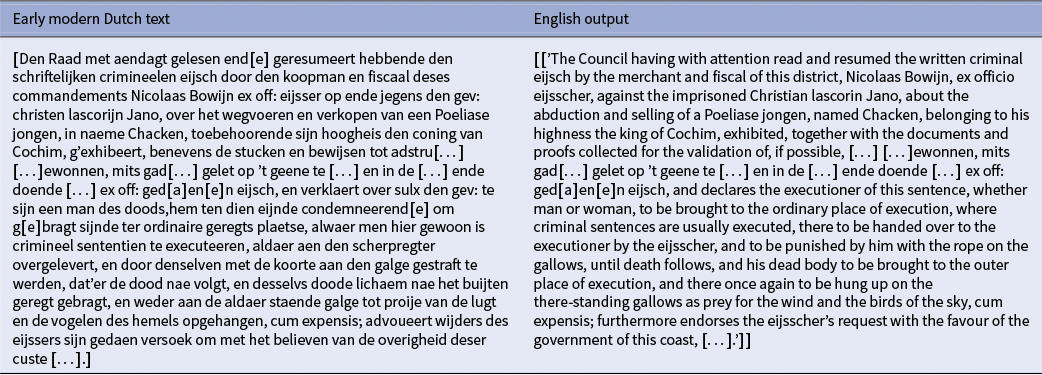

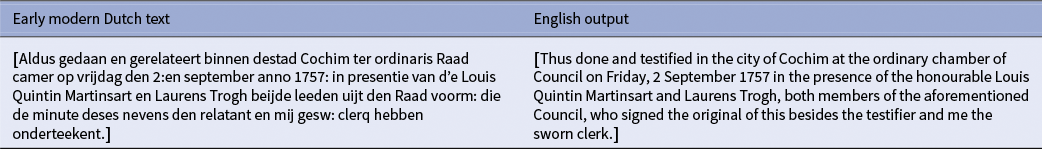

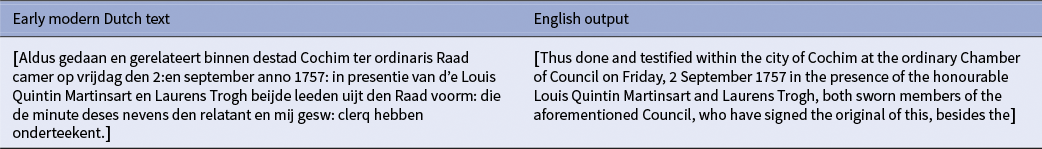

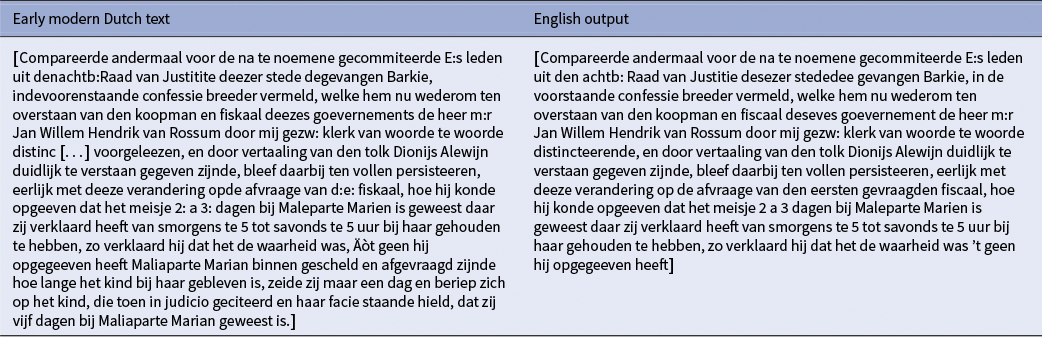

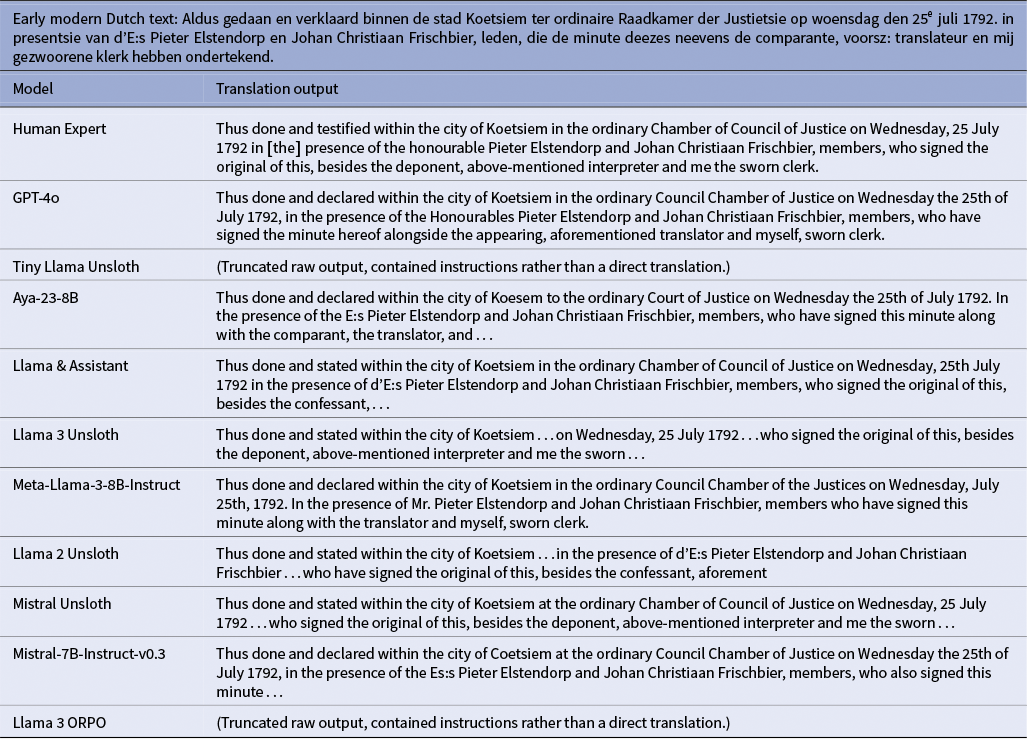

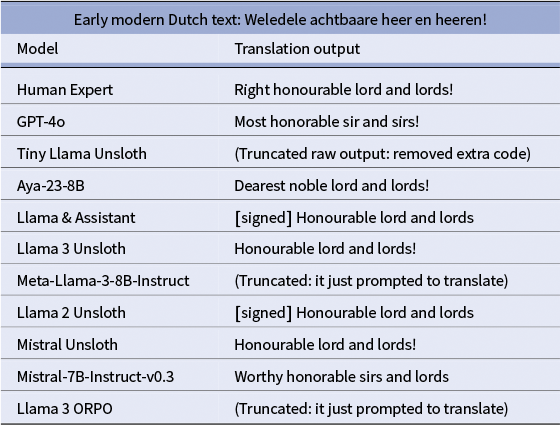

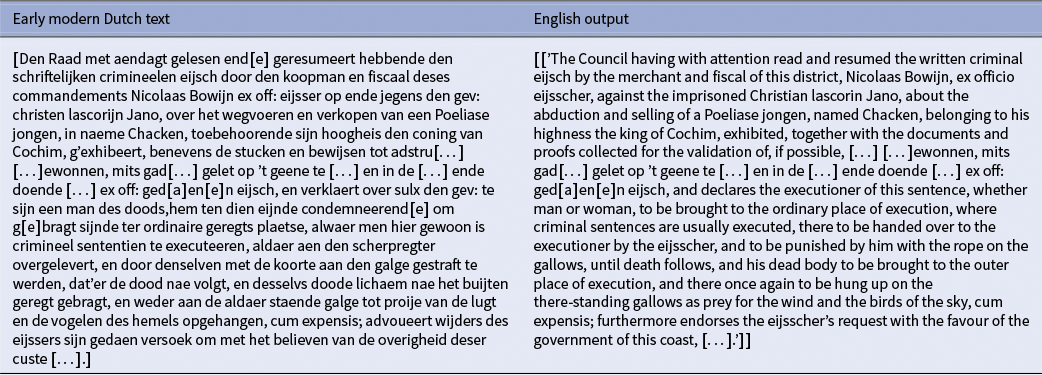

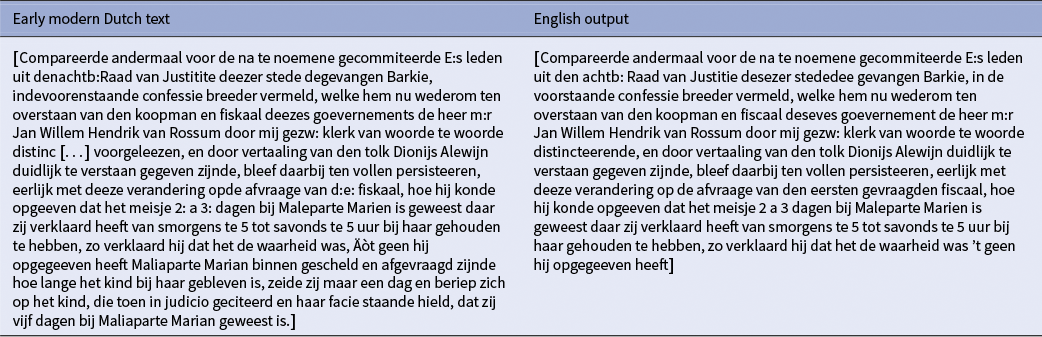

Mistral-Unsloth excelled not only in aggregate metrics but in domain expert assessment, demonstrating a strong capacity for handling the specialized lexicon of historical legal documents. The model consistently preserved critical semantic categories, including specific occupation titles (e.g., wasvrouw [laundress]), formal role titles (e.g., eijsscher [plaintiff/prosecutor]) and period-specific legal terms (e.g., schagerije [a type of dairy farm or settlement]). This proficiency is evidently illustrated in Table A2, where the translation accurately renders complex procedural language – such as “Aldus gedaan en gerelateert” to “Thus done and testified” and “gesw: clerq” to “sworn clerk” – while correctly preserving names, dates and the formal structure of the declaration. However, this high standard was not maintained across all outputs. Occasionally, the model exhibited inconsistencies with certain filler words and abbreviations, leading to a dip in translation quality. These specific shortcomings are documented in Tables A1 and 3, which showcase instances of untranslated words and verbatim copying of the source text, highlighting the areas where the model’s performance remains variable.

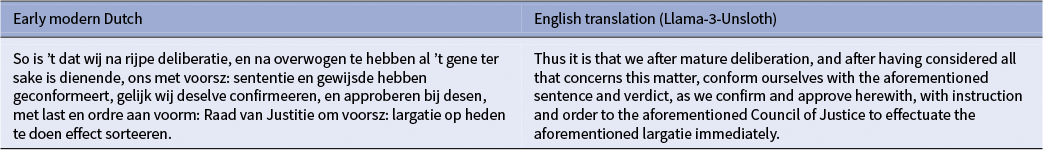

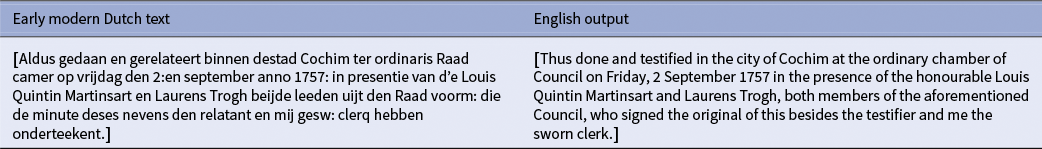

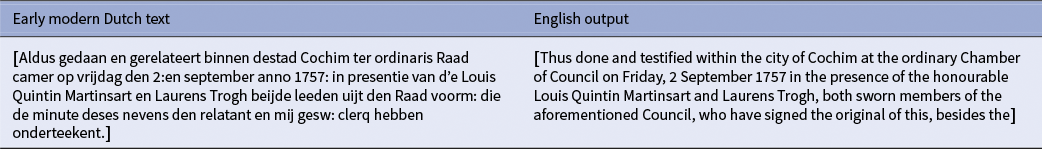

Table 2. Example of a high-quality translation by Llama-3-Unsloth showing preservation of legal syntax and formal register

Table 3. Example of an unsatisfactory translation: the Dutch text is copied verbatim rather than translated

Llama-3-Unsloth ranked a close second. Metric gains over the unfine-tuned Llama-3-8B-Instruct confirm the benefit of domain adaptation. Expert review noted strong preservation of complex legal syntax and formal register, though the model maintained the same tendency to leave Dutch technical vocabulary untranslated (Table 2). The model demonstrated sophisticated handling of archaic abbreviations and intricate sentence structures, expanding abbreviated forms like “voorsz:” and “voorm:” to “aforementioned” while preserving the document’s formal legal tone. However, specialized legal terms, such as “largatie,” remained untranslated, reflecting the model’s capability to preserve domain-specific terminology.

Both Unsloth-tuned models achieved high automatic scores yet share two limitations: (a) incomplete rendering of specialized terminology and (b) occasional omission of abbreviations or honorifics embedded in the source. Addressing these gaps, through the expansion of the targeted glossary or additional preference alignment, will be essential before deploying the systems for large-scale historical research.

In sum, automatic metrics and expert feedback converge: Unsloth fine-tuning markedly improves translation quality, with Mistral-7B-Unsloth the current best option, with domain-specific terminology remaining intact, preserving historical authenticity.

Mid-range performance models

Aya-23-8B produces readable output, but quality fluctuates more than for the top systems. Roughly one sentence in 10 drifts far enough from the reference to require manual correction, as shown by the wider spread in Table A7. Error clusters in Table A3 reveal systematic problems with archaic verb endings and idiomatic noun compounds, suggesting that a modest domain-specific fine-tune could stabilize performance. Teams employing Aya-23-8B should budget a short post-editing pass and, where resources permit, curate several thousand additional sentence pairs before large-scale deployment.

The Llama 2-Unsloth and Assistant models deliver steadier output, but still suffer from untranslated sentences. Their higher mean BERTScore and METEOR values (Figures 3 and 4) allow editors to focus on stylistic polish rather than basic correctness. Nevertheless, the long tail of low-confidence sentences, again visible in Table A10, shows that perfect automation is still out of reach. This can be observed in Table A3 where the phrase “myself, the sworn clerk” has been left out of the translation. Furthermore, on longer sentences, the model will still leave the sentence fragmented and untranslated (Table A4). These results reflect the model’s inconsistent performance, which requires further improvements for usability.

Figure 3. Distribution of BERTScore values for all systems, ranked by mean.

Figure 4. Distribution of METEOR scores for all models, ranked by mean.

Qualitative review confirms these findings. Both models usually preserve grammatical structure and semantic content, yet they recurrently leave Dutch terms, such as meijd, jongen and eijsser untranslated, and they handle proper names or titles inconsistently. Another quirk is the insertion of the bracketed word “signed” in official documents. Table A3 illustrates a strong rendering, whereas Table A4 shows a complete failure in which the Dutch source is reproduced verbatim. The comparison reveals a catastrophic LLM failure where the model failed to translate, instead producing a “modernized” Dutch version that destroys historical authenticity through inappropriate spelling standardization and content truncation. This example illustrated a failure where an untrained LLM produced modernized Dutch text rather than English translation, destroying historical authenticity through inappropriate orthographic standardization and content truncation. The failure validates our core finding that PEFT is essential for preserving documentary integrity in early modern Dutch translation tasks.

Llama 2-Unsloth’s metric gains over the base Llama-2-7B model indicate successful adaptation, yet the broader score distribution in Figures 3 and 4 implies vulnerability to syntactically dense passages.

Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3, despite the absence of domain fine-tuning, delivered impressively stable scores with minimal fluctuation (Figure 3), making it an attractive foundation for future adaptation. Expert review (Tables A8 and A9) shows that it preserves structure in simpler sentences but mistranslates abbreviations (E:, achtb.) and substitutes modern equivalents for historical measurements or currencies.

In sum, the mid-range systems achieve moderate automatic scores but share three limitations: (i) incomplete handling of specialized terminology, (ii) inconsistent treatment of proper nouns and titles, and (iii) occasional sentence-level failures on complex inputs. Addressing these gaps through targeted glossary expansion, additional preference alignment or confidence-based filtering will be essential before large-scale historical translation can proceed without human oversight.

Under-performing models

TinyLlama-1.1B-Unsloth scored well below all other fine-tuned systems (Table A7). Its low mean BERTScore and METEOR values, and the wide interquartile range, show that a one billion-parameter model lacks the capacity to capture early modern Dutch morphology and legal terminology. Occasional fluent sentences do appear, but the high variance suggests that extensive domain-specific augmentation or a larger backbone would be required before production use.

Llama-3-8B-ORPO exhibited similar volatility. Although individual outputs sometimes matched expert quality, many contained prompt remnants, repetitions or unfinished clauses, depressing overall metrics (Table A7). These errors point to miscalibrated reward weights: refining the preference data set or annealing the KL term could stabilize training.

The base Meta-Llama-3-8B-Instruct checkpoint delivered the weakest results among the untuned systems (Table A10). High score dispersion confirms that instruction tuning alone is insufficient for 17th-century Dutch and corroborates the large gains achieved through Unsloth SFT.

Evaluation

Fine-tuned model capabilities

The fine-tuned systems adapted with the Unsloth procedure markedly outperformed their baseline counterparts. Mistral-Unsloth achieved the closest alignment with expert reference translations, confirming that Unsloth can capture the lexical nuance and syntactic irregularity characteristic of early modern Dutch. Its low score variance further recommends it for applications in which scholars require dependable, minimally post-edited output.

Llama-3-Unsloth also profited from the same adaptation, although its wider dispersion of scores indicates residual sensitivity to sentence complexity and specialized terminology. Even so, the model’s mean performance approaches that of Mistral-Unsloth, shown in Figure 5, underscoring the practical value of targeted fine-tuning for historical translation. Together, the two models demonstrate that parameter-efficient strategies can yield both accuracy and stability, provided the backbone has sufficient capacity and the domain data are carefully curated.

Figure 5. Sentence-level METEOR distributions for the two best systems.

ORPO fine-tuning challenges

The Llama-3-8B model fine-tuned with ORPO delivered markedly lower and less reliable scores than the Unsloth SFT baselines. Its mean BERTScore was 0.617 (median = 0.665, SD = 0.180) and its mean METEOR 0.405 (median = 0.461, SD = 0.246; see Tables A10 and A11). Although the model occasionally produced near-expert translations, the wide dispersion of scores indicates that such high-quality outputs were unpredictable and infrequent. A review of the training notebook and data flow points to three primary implementation issues that likely caused this underperformance, rather than an intrinsic flaw in the ORPO algorithm for this task.

-

a) Sparse, imbalanced preference pairs: ORPO’s efficacy depends on a sufficient volume of high-quality chosen-rejected example pairs. With only 1,281 sentence-translation tuples available, creating the preference dataset effectively halved the number of examples seen per epoch compared to SFT. This data scarcity forces the model to learn from a very narrow distribution, increasing the risk of overfitting to frequent lexical patterns in the training data rather than learning generalizable syntactic and semantic rules for translation. Furthermore, using a powerful model like GPT-4o for the “rejected” samples, while a common practice, may have introduced high-quality but stylistically different translations, potentially sending a noisy or conflicting signal to the model during alignment.

-

b) Prompt-template drift: A critical mismatch existed between the structured, multi-line instruction block used during training and the simple, single-sentence prompt used at inference. Instruction-tuned models are highly sensitive to the format of the prompt. This discrepancy meant that the model was not optimized for the task it was being asked to perform during evaluation. Consequently, the model often exhibited prompt leakage, reproducing parts of the training header or failing to complete the translation (shown in Table A5), which severely depressed the adequacy scores and contributed to the high variance in performance.

-

c) Conservative hyper-parameters: The training configuration, which ran for eight epochs with a low learning rate of

$1\times 10^{-5}$

and a micro-batch size of two, was likely too conservative for this context. In ORPO, the language modeling loss is balanced by a KL-divergence regularizer that prevents the model from deviating too far from its original capabilities. When combined with a low learning rate, this regularizer can dominate the training process, effectively stifling the model’s ability to adapt to the new domain. The model is thus prevented from fully learning the nuances of Early Modern Dutch, leading to translations that may remain closer to the base model’s generic output rather than acquiring specialized historical knowledge.

$1\times 10^{-5}$

and a micro-batch size of two, was likely too conservative for this context. In ORPO, the language modeling loss is balanced by a KL-divergence regularizer that prevents the model from deviating too far from its original capabilities. When combined with a low learning rate, this regularizer can dominate the training process, effectively stifling the model’s ability to adapt to the new domain. The model is thus prevented from fully learning the nuances of Early Modern Dutch, leading to translations that may remain closer to the base model’s generic output rather than acquiring specialized historical knowledge.

These three factors – data sparsity, prompt inconsistency and a restrictive training regime – collectively explain the 0.20–0.35 drop in mean scores and the nearly three-fold increase in variance relative to the Unsloth SFT models, without necessarily indicting ORPO’s underlying algorithm for historical translation tasks.

Base model capabilities

The untuned Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3 delivered stable BERTScore and METEOR values across the test set, confirming that it possesses a strong multilingual prior even without domain adaptation. This consistency makes it an attractive foundation for historical translation workflows. Once fine-tuned with Unsloth SFT the model’s average scores rose by 8–10 points, and variance fell by roughly one third, indicating both higher accuracy and greater reliability (Table A10). The gain demonstrates the practical value of lightweight parameter-efficient tuning when adapting a general LLM to the lexical and syntactic idiosyncrasies of 17th- and 18th-century Dutch.

Among the other baselines, GPT-4o produced the most dependable high-quality output without any additional training. Although its mean scores lagged slightly behind the Unsloth-enhanced Mistral, the narrow dispersion of GPT-4o shows that it can serve as a robust standard alternative when compute or data for fine-tuning are unavailable (Figures 3 and 4). Taken together, these results suggest a two-tier deployment strategy: use GPT-4o as an immediate, low-overhead baseline and adopt a fine-tuned Mistral backend when project resources permit domain adaptation and post-editing.

Discussion

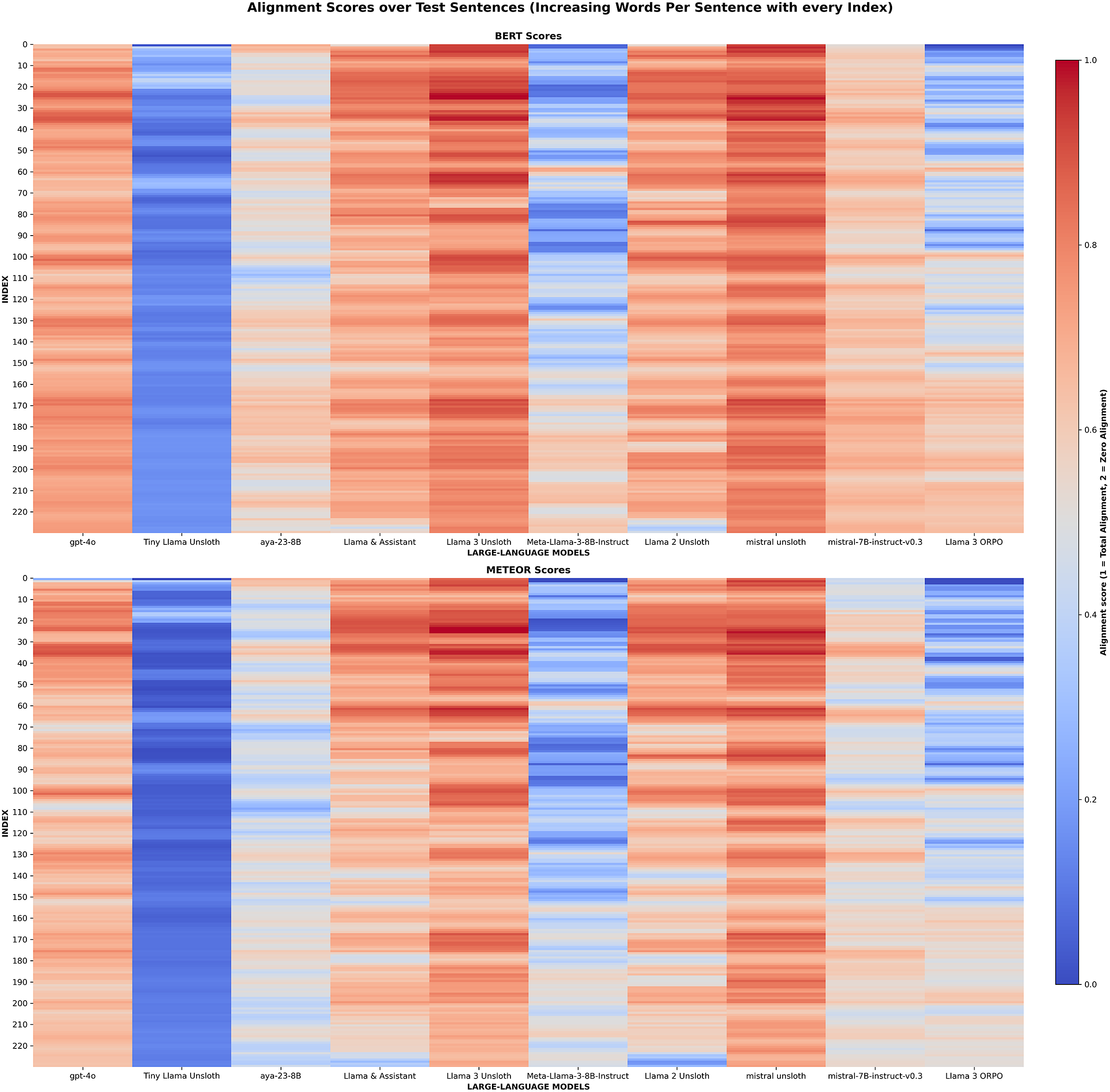

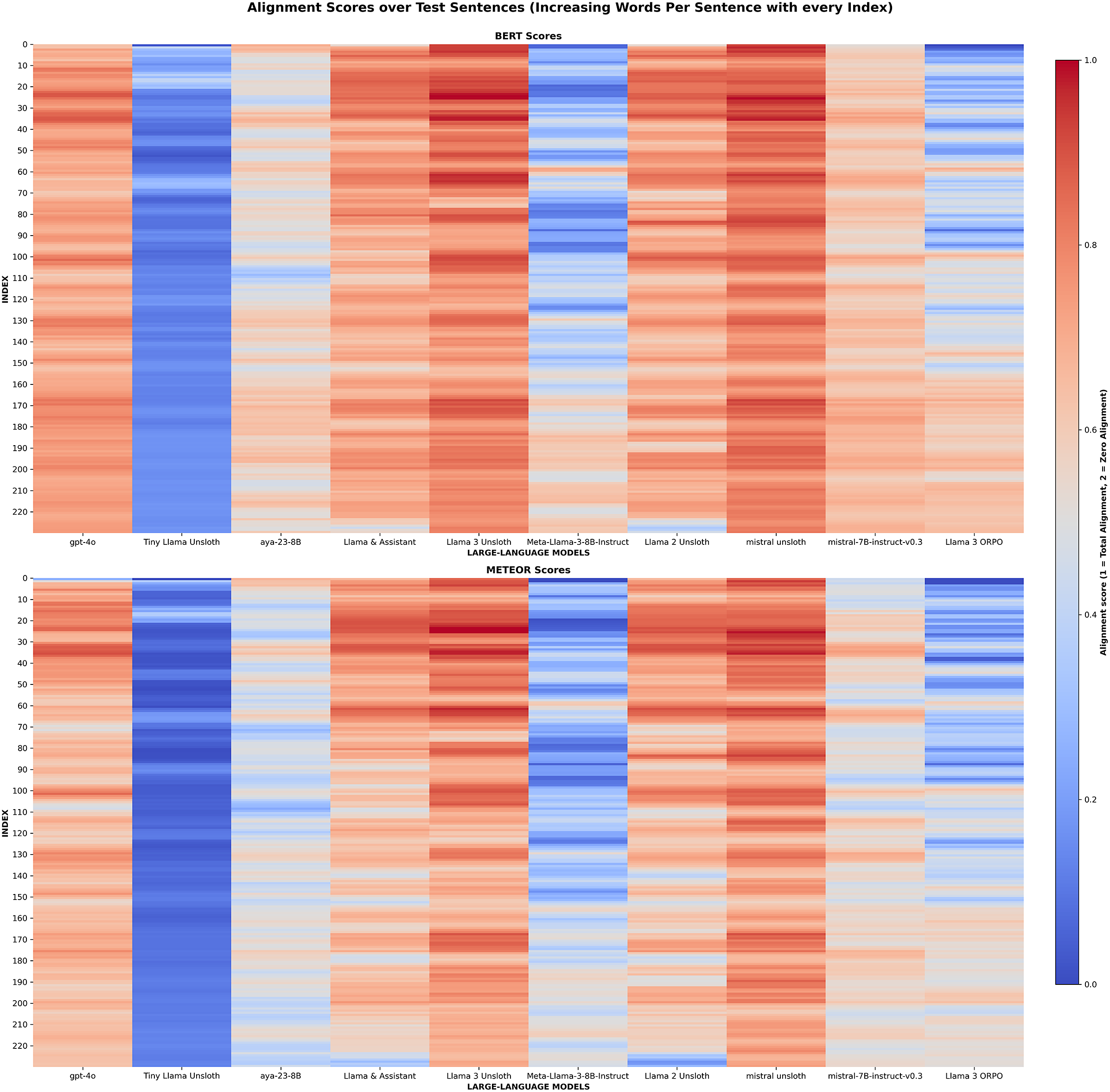

The comparative results underline how strongly translation quality varied between fine-tuning strategies. This is shown starkly in Figure A1, which highlights the jump in performance from base model to fine-tuned model through a heatmap visualization. Unsloth adaptation, exemplified by the Mistral-Unsloth and Llama-3-Unsloth models (Figures 3 and 4), consistently surpassed all alternatives. The ORPO variant remains less successful, but its shortcomings appear remediable (“ORPO fine-tuning challenges” section). Adjusting the preference corpus and harmonizing training and inference prompts may narrow the current performance gap. More broadly, combining automatic metrics with an authenticity checklist covering proper-noun preservation, date fidelity and punctuation style would yield a balanced scorecard for future experiments. A recurring error pattern across systems is the handling of very short lexical items and abbreviations in Dutch: when a sentence is both brief and semantically opaque, the model often leaves such tokens untranslated because their functional role is unclear. Targeted glossaries or context-window augmentation could mitigate this issue without sacrificing fluency.

Historical translators must decide which elements should remain unchanged to preserve documentary authenticity. Proper names, official titles (schout, fiscaal) and obsolete currency units (e.g., stuiver) are prime examples. Our expert evaluation shows that Mistral-Unsloth retains almost all personal and place names verbatim, whereas Llama-3-Unsloth occasionally anglicizes Dutch surnames or expands abbreviated titles. In contrast, GPT-4o sometimes over-translates institutional names, rendering Hoogheemraadschap as “Water Board,” which may help modern readers but risks erasing historical nuance. A pragmatic compromise is to keep these critical tokens in their original form and provide a parenthetical gloss on the first occurrence. Implementing this policy would require a lightweight named-entity filter upstream of the decoder or a constrained decoding pass that protects whitelisted terms.

Findings

This study compared two parameter-efficient adaptation strategies, ORPO and Unsloth SFT for translating early modern Dutch into present-day English assessed through both qualitative and quantize frameworks. Both methods improved substantially on untuned foundation models, yet their performance profiles diverge in ways that matter for historical scholarship. Unsloth fine-tuned Mistral and Llama 3 systems delivered the highest BERTScore and METEOR values while preserving most syntactic and stylistic features observed in expert references. ORPO, by contrast, produced more variable output: when reward signals aligned with domain needs, it matched Unsloth quality, but miscalibrated preferences yielded prompt leakage or unfinished clauses. The TinyLlama experiment shows that extreme parameter reduction comes at a steep cost to adequacy and fluency, confirming that complex, low-resource language varieties still demand mid-size or larger backbones. Taken together, the results advocate for a two-step workflow, tokenizer customization, followed by Unsloth SFT for projects that require dependable, scalable translation of historical texts.

Future work

Scalable infrastructure

The present experiments were limited by GPU memory, restricting model depth, batch size and context window. Even a modest increase in compute would enable larger backbones and longer sequences; scaling-law studies indicate near-linear gains in accuracy under such conditions (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Borgeaud, Mensch, Alice, Naumann, Globerson, Saenko, Hardt and Levine2022; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, McCandlish and Henighan2020). Beyond simply improving accuracy, scaling up the infrastructure would allow for fundamentally new research avenues. For instance, larger context windows (e.g., 32k or 128k tokens) would enable the translation of entire documents or chapters at once, rather than sentence by sentence. This would significantly improve coherence and consistency, allowing the model to track entities, terminology and narrative threads across long passages. Furthermore, employing larger backbone models (e.g., 70B or mixture-of-experts models) could enhance the system’s ability to grasp complex legal reasoning, subtle irony or intricate rhetorical structures present in the source texts, which smaller models might oversimplify.

Richer, well-curated data

Translation quality is ultimately capped by the scarcity of parallel material. Expanding the corpus across genres and annotating each record with place, year and document type remain a priority. Automatic workflows that recognize 17th- and 18th-century typographic conventions can accelerate transcription, while a tokenizer retrained on the enlarged dataset should capture historical spelling variation without inflating sequence length (Kudo and Richardson Reference Kudo, Richardson, Blanco and Lu2018). While the current corpus of court testimonies is valuable, its legalistic and formal nature may bias the model. Future work should prioritize expanding the training data to include a wider array of genres, such as personal letters, ship logs, administrative ledgers and pamphlets. This would create a more versatile translator capable of handling different registers and domains. Additionally, a significant challenge is the lack of a standardized transcription protocol for Early Modern Dutch. A key future task will be to develop and apply a semi-automated transcription workflow that can handle abbreviations, non-standard spelling and paleographic variations, perhaps using a combination of OCR/HTR models fine-tuned on specific scribal hands. This would not only accelerate corpus creation but also enrich the dataset with valuable metadata about scribal practices. This expanded and diversified corpus would, in turn, serve as the foundation for retraining the domain-specific tokenizer, further enhancing its ability to model historical spelling variation across genres and time periods.

Enhanced alignment strategies

ORPO lagged behind SFT chiefly because of sparse preference pairs and divergent prompt templates. Forthcoming work will (i) enlarge the preference pool with varied negative examples, (ii) harmonize training and inference prompts, and (iii) run ORPO as a post-SFT refinement step (Hong, Lee, and Thorne Reference Hong, Lee, Thorne, Salakhutdinov, Kolter and Heller2024; Ouyang et al. Reference Ouyang, Jeff, Jiang, Alice, Naumann, Globerson, Saenko, Hardt and Levine2022). The suboptimal performance of ORPO highlights the sensitivity of preference-based alignment methods to data quality and prompt design. Future iterations will focus not just on enlarging the preference pool, but also on diversifying it. This includes generating “better” negative examples that are subtly incorrect (e.g., grammatically fluent but semantically inaccurate) rather than obviously flawed. This would force the model to learn finer-grained distinctions. Beyond ORPO, exploring other alignment techniques like Kahneman–Tversky optimization (KTO), which does not require paired preference data, could offer a more robust solution for low-resource scenarios. A comparative study of these different alignment methods could yield a clearer understanding of which strategies are best suited for the unique challenges of historical texts, where human preferences might involve balancing literal accuracy with historical authenticity.

Adaptation to other historical languages

The presented workflow, comprising metadata-rich corpus curation, custom tokenizer training and two-stage alignment with continuous domain expert oversight, offers a transferable methodological blueprint for other low-resource historical languages (e.g., Middle High German, early modern Spanish and regional Malay manuscripts). Although the current investigation focuses specifically on Early Modern Dutch legal texts, the core components of this framework, particularly the integration of domain expertise throughout the pipeline, provide a reproducible approach adaptable to diverse historical contexts and text types.

It is acknowledged that the present implementation utilizes a specialized legal corpus; consequently, future applications would benefit from validating the approach across multiple genres and domains. The essential transferable elements include the PEFT strategies, evaluation protocols combining automatic metrics with expert review and tokenizer adaptation methodologies. However, successful application to new languages necessitates language-specific resources, particularly curated parallel corpora developed in collaboration with subject matter experts.

By emphasizing verifiable translation through sustained domain expert involvement, this pipeline model could help unlock extensive archives for linguists, historians and the broader public. The framework’s ultimate adaptability will depend on addressing language-specific challenges while maintaining the core principle that historical translation requires continuous scholarly validation to ensure both accuracy and preservation of documentary authenticity.

Interactive and verifiable translation

Future systems should move beyond static translation and toward an interactive, human-in-the-loop framework. This could involve developing an interface where historians can not only correct translations but also see the model’s confidence scores for specific words or phrases. The system could offer multiple translation options for ambiguous terms, annotated with explanations drawn from historical dictionaries or linguistic corpora. Such a tool would transform the model from a “black box” into a transparent research assistant. Furthermore, integrating a mechanism for the model to learn from these expert corrections in real-time (online learning) would create a continuously improving system that becomes more attuned to the specific needs and nuances of a particular research project or archive.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

This research highlights the critical importance of sustained interdisciplinary collaboration between computational methods and humanities scholarship. Future work should develop structured frameworks for domain experts and technical researchers to co-design translation systems that balance technical efficiency with historical accuracy. Such partnerships are essential for addressing epistemological questions about how MT shapes historical interpretation while ensuring tools enhance rather than replace traditional scholarly practices. Establishing sustainable collaboration models will be crucial for adapting this approach to diverse historical contexts and text types.

Conclusion

This study investigated PEFT strategies for translating early modern Dutch into present-day English.

Unsloth adaptation proved most effective: the Mistral-7B-Unsloth model achieved the highest mean BERTScore and METEOR values with the narrowest spread, while Llama-3-Unsloth followed closely but showed greater variance. By contrast, Llama-3-ORPO lagged behind, its lower and less stable scores traceable to sparse preference data and prompt drift rather than to ORPO’s core algorithm.

Among the untuned baselines, GPT-4o offered the strongest off-the-shelf performance, furnishing a dependable benchmark when compute or parallel data are scarce. Mid-range systems, such as Aya-23-8B and Mistral-7B-Instruct, delivered moderate but fluctuating quality, and the TinyLlama-Unsloth experiment confirmed that extreme parameter reduction cannot yet capture the lexical and syntactic nuance of 17th- and 18th-century Dutch.

Three broad conclusions follow. First, careful, PEFT, backed by a domain-specific tokenizer and curated parallel corpus, can raise translation quality to near-expert levels while containing hardware costs. Second, robustness still hinges on sentence length and specialized terminology; further gains will require richer training data provided by domain-experts, context-aware prompts and glossaries for period-specific vocabulary. Third, hybrid evaluation that combines embedding-based metrics with domain-expert review remains essential: automatic scores alone under-report errors in proper-name handling, abbreviations and legal terms.

Future work should (i) scale Unsloth tuning to larger backbones and longer contexts, (ii) expand the parallel corpus across genres and regions, and (iii) revisit ORPO as a post-SFT refinement once preference data and prompt alignment are improved. The framework outlined here, metadata-rich corpus curation, custom tokenizer training and domain-expert-aided two-stage alignment, offers a transferable blueprint for other low-resource historical languages, such as Middle High German, Early-Modern Spanish and regional Malay manuscripts. By systematically addressing the twin challenges of orthographic fragmentation and domain-specific terminology that characterize historical texts, such pipelines could unlock extensive archives for linguists, historians and the broader public. This research envisions a collaborative workflow where machine-generated translations serve as initial drafts for domain experts, reducing the time-intensive process of translating archival materials from scratch. Rather than replacing human expertise, our approach provides historians with rough translations that preserve historical terminology and context, which they can then refine and verify. This hybrid human–machine process makes large-scale archival translation feasible while ensuring scholarly accuracy through continuous expert validation.

This methodological framework promises to enable new research on migration, cultural exchange and social change that remains hidden behind linguistic barriers, while ensuring that computational tools preserve rather than compromise the documentary integrity essential to historical scholarship. The combination of PEFT with rigorous evaluation protocols thus provides a scalable pathway toward more accurate and transparent access to the world’s multilingual archival heritage.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to David Grantsaan for evaluating the translation quality of the LLMs, their expertise was crucial for judging the results.

Data availability statement

Computation notebook files, supplementary material, and replication of open-access data and code are available at this anonymous Github Repository: https://github.com/glp500/EMDutch-LLM-Finetune.

Disclosure of Use of AI Tools

No AI was used to generate content or conduct any part of the research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: G.L., V.d.B. and A.B.; Data curation: G.L.; Formal analysis: G.L.; Investigation: G.L.; Methodology: G.L.; Resources: V.d.B. and A.B.; Software: G.L.; Supervision: V.d.B. and A.B.; Validation and formal analysis: D.G.; Visualization: G.L.; Writing – original draft: G.L.; Writing – review and editing: V.d.B. and A.B.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The research was conducted as a partnership between Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and the KNAW Humanities Cluster. Open access funding provided by Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors affirm that this research did not involve human participants.

Appendix

Table A1. Bad translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Unsloth Mistral]

Table A2. Good translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Unsloth Mistral]

Table A3. Good translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Llama & Assistant]

Table A4. Poor translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Llama & Assistant]

Table A5. Translations of early modern Dutch text by different models

Table A6. Training arguments for different models

Table A7. Translation responses of various models

Table A8. Good translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3]

Table A9. Good translation from early modern Dutch to English by [Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3]

Table A10. Statistics of BERT scores for all models

Table A11. Statistics of METEOR scores for all models

Figure A1. BERT and METEOR score heat map.

Rapid Responses

No Rapid Responses have been published for this article.