Introduction

The shift of state–civil society relations towards collaboration lies at the core of the public-sector managerial models of the 2010s (Greve, Reference Greve2015). Examining such managerial approaches in a critical way, one can say that the collaboratively oriented governance model presents public organisations as agents that both withdraw from and open up to society when dealing with modern societal problems (Peeters, Reference Peeters2013). Collaboration with third-sector organisations (TSOs) lies at the core of such managerial models, especially when it comes to reforming the welfare state (Salamon, Reference Salamon2015; Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015).

This study focused on the concept of collaborative governance to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of the collaboration between public organisations and TSOs in the field of social welfare and health. Ansell and Gash (Reference Ansell and Gash2008, p. 544) described collaborative governance as ‘a governing arrangement where… public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders’. Following Emerson et al., (Reference Emerson, Nabatchi and Balogh2012, p. 2) collaborative governance is seen as a construct that emerges when people are transcending ‘the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished’.

We suggest that ‘collaboration’ between public organisations and TSOs should be understood as a form of social structure, a construct, influenced by the individual features of the collaboration actors and especially by their institutional settings and their positions in them. Collaboration is seen as an active process of working together, observed as both a formal and more informal arrangement of joint work, whereas the concept of partnership is rather a state of relationship (Whittington, Reference Whittington, Weinstein, Whittington and Leiba2013, pp. 15, 16). This approach helps to gain a nuanced understanding about collaboration dynamics, and this way contribute to collaborative governance literature (see Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Nabatchi and Balogh2012).

The theoretical framework of this study draws on studies focusing on the relations and collaboration between TSOs and public organisations. Research has shown that the relations between public organisations and TSOs are complex and shaped by different forms of dependency and conflicts of authenticity (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Martin, Reference Martin2011; Najam, Reference Najam2000; Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015; Verschuere & De Corte, Reference Verschuere and De Corte2014, Reference Verschuere and De Corte2015). Despite these dependencies, TSOs cannot be positioned solely as ‘underdogs’, as they also act in strategic ways in their collaboration with public organisations (Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018, p. 854; Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015). Moreover, varying politico-administrative contexts, different institutional forms of working together, and the diversity of collaboration roles make collaboration difficult to define unambiguously (Najam, Reference Najam2000; Pape et al., Reference Pape, Brandsen, Pahl, Pieliński, Baturina, Brookes and Chaves-Ávila2020; Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015).

Our aim was to contribute to the understanding of the collaboration between TSOs and public organisations from the viewpoint of collaboration agency by exploring TSOs’ discourse on collaboration. Taking an inductive approach, we investigated how TSOs portray their collaboration with public organisations and what kinds of collaboration agency can be identified based on these descriptions? The context of the study was social and health services in Finland, which represent a Nordic welfare model with a universal public service system. Throughout the research, we examined collaboration agency through an institutional lens. We used the concept of agency to analyse the structural effects of the interactions between various actors (Schwinn, Reference Outhwaite and Turner2007), focusing on the organisational level of collaboration.

Contextualising the Study: The Third Sector in Finland

The Finnish healthcare and social welfare system is decentralised and is mainly funded by municipal authorities, which are responsible for providing residents with healthcare and social welfare services. Local governments can organise the services themselves or purchase them from private organisations and TSOs. The operations of TSOs are funded by state-level agencies. The Funding Centre for Social Welfare and Health Organisations (STEA) handles the distribution, monitoring, and impact evaluation of funds granted to social welfare and health organisations. The funding system is currently being reconstructed. In addition to funding from the STEA, other key sources of income for TSOs are service fees and proceeds from other forms of operation. The main sources of income of local associations are membership fees and the proceeds from the activities that they arrange. Local associations can also receive small municipal grants for their work (SOSTE, 2020).

TSOs play an important role in the Finnish healthcare and social welfare system. Social welfare and health TSOs are often the leading experts in their fields. Many of the welfare services that are currently the responsibility of some 300 municipalities in Finland were initially developed by TSOs (Särkelä, Reference Särkelä2016). TSOs offer support, advice, and information, act as interest and pressure groups, train professionals in their fields, and provide services. They also play a central role in the provision of rehabilitation and social services (in particular, services for marginal groups).

The important role of TSOs has often been acknowledged in public discourse. However, the relationship between local governments and TSOs has changed in recent decades. Until the 1990s, TSOs were considered important partners of municipalities in service development and organisation. However, over the past two decades, the relationship has increasingly come to resemble a contractual one, emphasising market governance and a purchaser–provider relationship between TSOs and municipalities. This shift has been attributed, at least partly, to new public management policy ideas internationally and the national interpretation of European Union regulations, especially competition law, which has forced TSOs to compete with private companies and has diminished their role as active members of civil society (Särkelä, Reference Särkelä2016).

Public and Third-sector Organisations in a Collaborative Governance Framework

Although the roles of TSOs in societies have changed over time, they have maintained their roles as builders of social capital, protectors of pluralism, and citizen advocates. The third sector can be seen as a provider of services to the public alongside the public and private sectors (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017). Being both a part of civil society and (public) welfare service providers, TSOs assume various roles stemming from multiple positions. In this study, these roles and positions were examined through the lens of collaboration agency.

Collaboratively oriented governance (Greve, Reference Greve2015) increasingly seeks opportunities for collaboration between civil society actors, including TSOs (Martin, Reference Martin2011; Peeters, Reference Peeters2013; Pestoff, Reference Pestoff2014). As Brandsen et al., (Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017, p. 679) note, this quest for collaboration creates novel types of public organisation–TSO relationships, in which public actors actively try to shape and ‘manufacture’ TSOs.

This ‘manufacturing’ work can be seen when examining the forms of collaboration and the roles given to TSOs in this collaboration. Although public organisations may be more open to collaboration, the variety in the forms of collaboration may be narrowed. Contract-based co-management is becoming increasingly common in the field of TSOs (Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018; Pestoff, Reference Pestoff2014; Tsukamoto & Nishimura, Reference Tsukamoto and Nishimura2006), while the various forms of co-governance—that is, policy formulation–oriented collaboration—are becoming less common (see, e.g., Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Tsukamoto & Nishimura, Reference Tsukamoto and Nishimura2006). The role of TSOs as co-managers in service production means more professionalisation and market orientation, which may conflict with the civic values of these organisations (Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018; Martin, Reference Martin2011; Pape et al., Reference Pape, Brandsen, Pahl, Pieliński, Baturina, Brookes and Chaves-Ávila2020; Pestoff, Reference Pestoff2014).

Indeed, the opportunities for collaboration with governments entail risks. Most importantly, researchers have expressed concern about the authenticity and weakening autonomy of TSOs in collaborative governance (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007; Brandsen & van Hout, Reference Brandsen and van Hout2006; Martin, Reference Martin2011). Collaboration that takes place in the ‘invited spaces of governance’ may silence the critical voices of TSOs, as they become ‘partners’ with organisations that they formerly sought to influence with their advocacy work (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007, p. 187). However, whether collaborative governance in fact weakens the authenticity of TSOs is the subject of debate among scholars (Najam, Reference Najam2000; Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015). For instance, Najam (Reference Najam2000, p. 390) underlines the strategicness of collaboration in situations in which power is unevenly distributed: ‘One party, often the NGO, may have fewer options to play with in reaching its decision, but its very choice to stay in the game is in itself a strategic decision.’

Avoiding voicing criticism may also be a consequence of several forms of dependency of TSOs on public organisations as supporters and funders of their activities (Brandsen & van Hout, Reference Brandsen and van Hout2006; Martin, Reference Martin2011). Nevertheless, the connection between dependency and avoidance of voicing criticism is not as straightforward as it may seem. It also depends on the type of relationship between a TSO and a public organisation and the kinds of activities in which the TSO is involved as part of the collaboration. As Arvidson et al., (Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018, p. 854) note, avoiding voicing criticism is an active strategic choice made by TSOs themselves when operating in competitive and resource-dependent environments (see also Najam, Reference Najam2000). Overall, it is difficult to develop a straightforward understanding of the ways in which various types of dependency affect the work of TSOs, especially in terms of alleged changes in their advocacy work and autonomy (Najam, Reference Najam2000; see also Salamon & Toepler, Reference Salamon and Toepler2015).

This is also due to hidden forms of dependency and power imbalances affecting TSOs and public organisations. The autonomy of TSOs may be restricted by institutional settings that involve less direct and clear dependency structures. For example, public organisations may be more likely to favour contract-based partnerships (i.e. co-management) with TSOs than to offer opportunities to collaborate in planning and policy formulation through co-governance (Tsukamoto & Nishimura, Reference Tsukamoto and Nishimura2006). This makes it more difficult for TSOs to maintain their advocacy role and authenticity (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017). The role of TSOs is rather to support public service provision, potentially also promoting active citizenship and good behaviour (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017, p. 679). Thus, collaboration becomes a steering mechanism and a tool for governmental control (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Peeters, Reference Peeters2013; Waardenburg & van de Bovenkamp, Reference Waardenburg, van de Bovenkamp, Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2014, p. 89).

Finally, as previously noted, the relations between public organisations and TSOs are not easy to define, as TSOs may also play strategic games in their collaboration, and public organisations also depend on the existence of TSOs. Overall, TSOs across Europe seem to be resilient in turbulent policy environments (Pape et al., Reference Pape, Brandsen, Pahl, Pieliński, Baturina, Brookes and Chaves-Ávila2020). Therefore, there is a need to better understand the nature of collaboration by examining the perceptions and lived experiences of the collaboration parties. This study contributes to this task by examining the collaboration agency of TSOs as revealed by the analysis of their collaboration discourse.

A Discourse Perspective on the Collaboration Agency of Social and Health TSOs

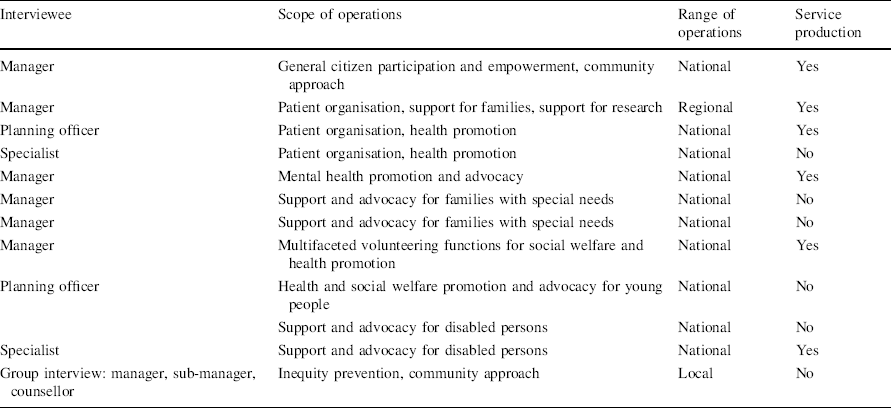

The qualitative data used in this study were collected in the context of a national social welfare and healthcare reform in Finland in 2018. In the Pirkanmaa region, regional experts and stakeholder groups were invited by the reform preparation group to participate in the planning and implementation of the reform. The groups were established to promote citizen participation and collaboration and involved representatives of both small local TSOs and large nationwide TSOs operating in the region.

The planning groups offered a setting for recruiting informants with first-hand in-depth knowledge of the role of TSOs in society (see Jupp, Reference Jupp2006). The interviewees (N = 16) were chosen because of their participation in these groups. They had high status in their respective organisations (see appendix) and during the interviews positioned themselves as their representatives. All were operating in the field of social and health services within the Finnish welfare state model in the Pirkanmaa region (see appendix). The variety of interviewees represented the entire range of social- and healthcare-focused TSOs with different financial and institutional positions, which affected their perceptions of their roles in collaboration. It is important to note that due to their roles in the reform work, the selected TSOs can be understood as actively engaging in collaboration and positioned close to public organisations.

The informants participated in semi-structured theme interviews (Schorn, Reference Schorn2000). The themes were (1) the operation and agenda of the respective TSO, (2) the social welfare and healthcare reform preparation group as a platform for co-creation, (3) cooperation and role of the TSO in the public service system, (4) expectations of TSOs in the social welfare and healthcare reform, and (5) the future. The interviews lasted about 60 min each. All interviews were conducted in Finnish, and quotations in following section are translated into English by authors.

In this study, the concept of agency refers to both individual and collective actors’ characteristics, behaviours, and functions (Giddens, Reference Giddens1984; Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Jessop and Mehmood2016, p. 169). It can be used to explain not only individual action choices but also—and more importantly—the structural effects of the interactions between many actors (Schwinn, Reference Outhwaite and Turner2007). Following this idea, this study focused on the organisational level of collaboration and its effects. Agency can take many forms due to different dispositions, mediating institutions, the actors’ ability to alter their social standing and identity, and rearrangement capability (Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Jessop and Mehmood2016, p. 169).

Widespread and even dominant discourse in society frames both the ways in which we understand and make sense of the world and the available options for developing actions (Alvesson & Karreman, Reference Alvesson and Karreman2000, p. 1138). The interest in discourse follows the idea of conceptualising discourse through ‘a duality of deep discursive structures and surface communicative actions’ (see Heracleous & Barrett, Reference Heracleous and Barrett2001, p. 755), which to varying extents also instantiate the deep structures. Discourse holds information that is somehow collectively shared and embodies both power and ideology (Jørgensenet et al., Reference Jørgensen, Jordan and Mitterhofer2012, p. 112).

Discourse analysis study of collaborative governance is needed in three ways: to gain deeper and more nuanced understanding on collaborative governance, to understand collaborative governance dynamics and power related to it, and to overcome normativity and declarative knowledge which has been a dominant (see also Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Nabatchi and Balogh2012, p. 22). The study of discourse on collaboration agency reveals an interesting link between human action and system-level conceptions of collaboration (see Heracleous & Barrett, Reference Heracleous and Barrett2001, p. 755).

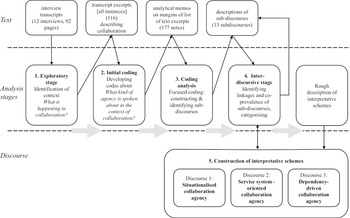

In this study, we performed an inductive discourse analysis of collaboration from the perspective of TSOs. Our discourse analysis (Fig. 1) drew loosely on the work of Paroutis and Heracleous (Reference Paroutis and Heracleous2013), Jørgensen et al. (Reference Jørgensen, Jordan and Mitterhofer2012), and Wallmeier et al. (Reference Wallmeier, Helmig and Feeney2019). The analysis process was applied ‘manually’, and each stage was organised in separate Word-documents. The stages were as follows:

(1) Exploratory stage: The analysis process started with immersion, carefully reading the data and noting how the informants spoke about collaboration (‘What is happening in collaboration?’). A total of 116 transcript excerpts were selected.

Example of an excerpt: ‘But we also do lot of collaboration with the cancer centre of the main hospital. So, it is really beneficial to them if they lack resources to sit down and speak with the patients.’

(2) Initial coding: Transcript excerpts were examined to develop codes guided by the research question, ‘How do TSOs describe collaboration?’ The codes were written in analytical memos (177 notes) on the margins of the list of excerpts.

Examples of codes: Collaboration built on the needs of the public service system; providing public services; collaboration defined by the service system

(3) Coding analysis: Coding continued in a more focused and analytical stage. A total of 13 sub-discourses) and the dominant linkages between them emerged. The sub-discourses were described in written form by answering to question ‘What kinds of agency emerge from these discourses?’.

Example of a description of a sub-discourse: Collaboration is seen as responsibilisation. Collaboration is based on mutual understanding but can shift to imbalanced collaboration when one party (a public actor) steps back and a TSO is pressured or even forced to take responsibility. This kind of agency can undermine the authenticity and internal ethics/moral codes of TSOs.

(4) Inter-discursive stage: The linkages and co-prevalence of sub-discourses were examined. Some overlapping descriptions of sub-discourses were re-examined and reinterpreted.

Example of a linkage: Sub-discourse Collaboration as responsibilisation reflects sub-discourse Settling in an existing framework for collaboration, in terms of threats to TSOs’ authenticity and limited action choices.

(5) Construction of interpretative schemes: Three interpretative schemes were constructed based on the sub-discourses (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Description of the analytical process

Discourse Analysis Results

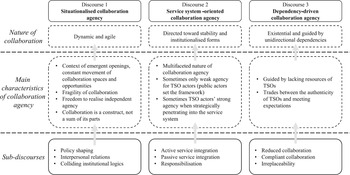

The analysis revealed three main discourses that reflected the nature of collaboration and the main characteristics of three main forms of collaboration agency: situationalised collaboration agency, service system–oriented collaboration agency, and dependency-driven collaboration agency. Each form of agency also had sub-discourses linked to the main discourse (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Summary of collaboration agency discourses

Discourse 1: Situationalised Collaboration Agency

The main characteristics of this discourse were dynamic and agile agency. Situationalised collaboration agency took place in the context of temporal openings. Attentive TSOs seized opportunities for collaboration with public organisations. The interviewees spoke of being alert and seizing opportunities to introduce their own expertise or special services into a larger service consortium:

“[Regarding a new service model bringing TSOs, private sector actors, and municipality services under the same roof.] We have been open now for two months, and it is very interesting to see what comes out of this. Quite interesting… but the role of the third sector is… we are on the ball there; whatever is going on, we’ll be part of it. If we really want to collaborate, we’ve got to keep our eyes and ears open [laughing]. (Interview 1)”

The data revealed a constant movement of collaboration spaces and opportunities for collaboration coming from various directions. TSOs were active themselves, but collaboration models were also the result of co-production between public organisations and TSOs. For instance, these kinds of collaboration models were based on the expertise and training offered by TSOs to professionals working in municipality social welfare and healthcare functions.

This situationalised framework made collaboration fragile but at the same time offered TSOs the freedom to exercise strong and independent agency in terms of seizing collaboration opportunities. Collaboration was shaped by several factors, such as finances, personal connections, service system reforms, organisational history, organisational strategies of TSOs, and authenticity of TSOs, and changes to any one of them had an impact on collaboration. These forces were visible in the identified sub-discourses of the situationalised collaboration agency discourse.

First, the policy shaping sub-discourse illustrated a form of agency strongly focused on pursuing strategic collaborations to influence policy-making processes. Several interviewees described this kind of agency. TSOs sought to get influential people on board through their activities, especially at the local level:

At the moment, it feels like collaboration with the local government works pretty well. We even have personal relations with the top managers. We’ve always had that with politicians and mayors and so on… Now we have it better; we’ve gained collaboration contracts as a result of being part of projects. (Interview 11)

It was also acknowledged that some TSOs had better opportunities to influence policy or become part of the system due to their superior resources. Thus, TSOs could shape policy to varying degrees. This is indicative of the labile nature of the environment in which TSOs operated.

A second sub-discourse on situationalised collaboration agency also described strategic relations, but more at a personal level and focusing on frontline relations than relations at the top policy level. The interpersonal relations sub-discourse had its foundations in seeking new forms of collaboration at the grassroots level of service production. Here, collaboration agency was also strategic, driven by the aim to penetrate the service system from the bottom up. As in the policy shaping discourse, this type of collaboration was fragile, as revealed in the following quotation:

Quite often, collaboration [with public service organisations] where you know a person is based on the relationship between two people. The collaboration takes place between them. And when you once again think about TSOs… they have a good connection with special expertise… And [in the context of reforming service structures] the person disappears into new structures. Or even if they don’t disappear, collaboration might be gone, or it just breaks down in this situation. (Interview 4)

Finally, while situationalised collaboration agency reflected an unexpected collaboration environment in which TSOs also needed to be alert to collaboration opportunities, it also reflected the autonomy of TSOs. In the colliding institutional logics sub-discourse, the representatives of TSOs also reported being cautious about collaboration with public actors due to colliding institutional logics. Sometimes it was not beneficial for TSOs to start a new collaboration, as the bureaucracy and inflexibility of public organisations, of which TSOs had prior experience, might, for instance, prevent the launch of new service models. However, this discourse was not as prominent as the discourses that presented collaboration with public organisations as valuable, or even of existential importance, for TSOs.

Discourse 2: Service System–Oriented Collaboration Agency

This discourse was prominent across various TSOs. It described a type of collaboration directed towards the stability and institutionalised positions of TSOs in the public service system.

This discourse was problematic in terms of the autonomy of TSOs. TSOs were offered weak agency if public actors set the collaboration framework and positioned them in a given structure in the public service system. Public actors acted intentionally to frame and control the agency of TSOs. For instance, they drove marketisation (e.g. by purchasing services from private and third-sector providers) as a precondition of collaboration or set other restrictive guidelines for TSOs. These preconditions undermined the autonomy of TSOs in terms of civil activities and advocacy work, as one interviewee noted:

[Talking about the strategic focus on operation in the markets versus civic activities.] It changes the interests, because it is, or at least has been, a question of whether a municipality will purchase this service or not, and questions like why this public tender is done like this, why we have not won the bid, and so forth. So, the focus is pretty much on these things. And the civic perspective and advocacy have been in the background and are still not at an adequate level. (Interview 6)

However, the power relations affecting the collaboration agency of TSOs cannot be expressed so simply. Service system–oriented collaboration agency was expressed in sub-discourses that reflected either active or passive agency and responsibilisation. In the active service integration discourse, the TSO actively penetrated the system by creating spaces for their agency with their supporting and integrating activities. Overall, this agency was guided by the desire to secure an institutionalised position and/or role in the service system, and thereby stability. Penetration was attempted by strategically seeking weaknesses of the systems, as described in the following quotation:

I believe that municipalities and hospital districts see peer support [provided by the TSO] as part of the service supply chain… And yes, it is on our agenda to find a spot for peer support as part of the service paths in the future as well. I do not see why this should not continue, as these activities have proved essential, producing effective and valuable outcomes. (Interview 3)

Moreover, this agency was driven by a service user perspective, as TSOs recognised these weak spots based on their members’ experience. This was a typical way of entering the service system: TSOs were informed by their members of the existing services and whether they met the needs of patients or service users. This role was highlighted across different TSOs, clearly reflecting the ongoing search for temporal openings for collaboration as well. Interestingly, TSOs emphasised that public organisations were open to such suggestions. This openness to collaboration reflected the collaboration environment, especially in the 2010s.

Despite public organisations’ openness to collaboration, imbalances in the collaboration environments were apparent, highlighting a passive service integration discourse as a second sub-discourse of service system–oriented collaboration agency. In this discourse, the role of TSOs was to act as ‘ligaments’ in the service system, but rather than being active agents seeking weaknesses themselves, it was public actors pointing out weak spots. The role of the TSOs was therefore to settle in the existing framework for collaboration. Collaboration spaces were offered as incentives for participation, but only in given structures, with no real possibility to negotiate.

It is said that TSOs have autonomy in making decisions over to whom they offer services and who their target groups are. But now someone comes and says, ‘Your target group cannot be this.’ Just because it would be overlapping with some public service, we have to redefine our target groups. In previous years, we had target groups ranging from babies to old people, and because of the new instructions, we had to change them to elderly and disabled people. (Interview 11)

The third sub-discourse, the responsibilisation discourse, was linked to the passive service integration discourse and highlighted the forced role of TSOs in collaboration. Although collaboration may at first have been based on mutual understanding, and even on formal contracts, it eventually became an imbalanced relationship, in which one party (a public organisation) stepped back and TSOs were forced to take responsibility for services or actions for which they were not prepared. Although the increased responsibility shouldered by TSOs may not have been explicit, it may have been an outcome of dysfunctional public services.

There has been a lot of responsibilisation on the part of the public organisation, as its own services have failed to meet the needs of service users. For instance, in the field of [special social and health services], public actors very eagerly tip service users off about our services because they do not have the resources themselves. But as we have limited resources here to run the service, we begin to have queues. This is because the public service system does not work as it should. (Interview 1)

The responsibilisation discourse encompassed TSO representatives talking about the precarious situations caused by responsibilisation, which were problematic for the authenticity and internal ethics and moral codes of TSOs—for instance, in terms of service promises to their members. The harshest comments referred to dishonesty in the rhetoric and reality of public organisations. These comments also reflected a power imbalance, calling for the examination of a dependency-driven form of collaboration agency.

Discourse 3: Dependency-driven Collaboration Agency

This type of agency was guided by the financial dependency and resource shortages of TSOs and caused various existential struggles. In its mildest forms, this agency consisted in a trade-off between the authenticity of TSOs and meeting the expectations of financing bodies, such as municipalities. In its most serious forms, it was a matter of survival for TSOs and was highly restrictive in terms of active collaboration agency. This type of collaboration agency mainly concerned TSOs that were entirely dependent on grants and subsidies and had no service production of their own or income from member fees. The nature of collaboration from the perspective of TSOs was existential and was guided by unidirectional dependencies. It was driven by financial dependency, the goal of penetrating the service system, and the recognition that there were limited options and opportunities. Simply put, TSOs either took the opportunity offered or risked their very existence. This form of collaboration involved a form of duress because seeking collaboration was the only way to ensure survival.

A sub-discourse in this category was a reduced collaboration discourse, in which collaboration was diminished to economic dependence. This discourse was guided by a division into givers and receivers. Collaboration was thus described and exemplified by referring to grants and subsidies that formed the basis for collaboration. Financial dependency was a struggle for survival and quite distant from the idea of reciprocal collaboration.

Related to this notion, the compliant collaboration discourse reflected collaboration in the context of imbalanced power relations. TSOs accepted the tasks that they were given to ensure their existence and ability to help their target groups. This discourse was connected to the previously discussed passive service integration and responsibilisation discourses, as the roles and duties were dictated by the collaboration party providing the funding and in some cases exceeded the capacities of the TSOs. Their limited capacities in terms of limited human resources and overwhelming numbers of service users also undermined the ethical standards and authenticity of TSOs. These sub-discourses painted a bleak picture of the collaboration between public organisations and TSOs. However, there was also evidence of a counter-discourse that presented TSOs as strong actors in collaboration.

In the final sub-discourse, the irreplaceability discourse, TSOs acknowledged their essential and irreplaceable role in the public service system and understood the dependencies from the public organisations’ perspective: Many parts of the service system would collapse without the TSOs’ efforts. This discourse can be viewed as constituting a self-empowering narrative that TSOs needed during times of fragmented funding and a vague collaboration environment.

Somehow, I see very clearly the important role of TSOs in Finland and Finnish society: We have deep roots; it is not easy to get rid of us, so we stand with an open mind towards the future. (Interview 4)

Discussion

In this study, discourses were used to examine the agency of TSOs in their collaboration with public-sector organisations. Reality and social systems can be seen as constructing practices and power structures. Although discourses may not have a visibly stable structure, they have structural properties. These properties, like social systems, vary depending on the time and place and the actors involved (Heracleous & Barrett, Reference Heracleous and Barrett2001, pp. 757, 758). Accordingly, interactive relationships are not only situations or contexts related to the use of language. Interaction is also a form of communicative encounter. Within these encounters, reality is reformed and reorganised due to the actors’ contributions.

The discourse-focused analytical lens of this study was used to examine agency as a form of interplay between individuals and the system. Based on our findings, it is easy to link the identified discourses to the public service system, which was the specific focus of one of the main discourses. Nevertheless, the forms of collaboration agency in which TSOs are involved are intimately connected to the public service system through TSOs’ acting in these settings and, from their perspectives, shaping the system. Based on the analysis of the main discourses in the context of the public service system, the following core characteristics of these discourses can be identified:

1. Situationalised collaboration agency in the service system context is agile and in constant movement, reflecting a dynamic system. This form of collaboration is shaped by TSOs’ seizing or declining collaboration opportunities, guided by shorter- or longer-term collaboration strategies. The situationalised collaboration form of agency is exemplified by notions of always being alert but also of critically evaluating opportunities for collaboration with public organisations against the possibility of conflicting institutional logics. Actively seeking opportunities to shape policies through either personal or more formal interactions underlines the strong agency of TSOs in shaping the system.

2. Service system–oriented collaboration agency already entails an interconnection between the agency of TSOs and the system. From this perspective, collaboration between TSOs and public organisations can be seen as an institutionalised, indispensable element of the public service system. This strong system-shaping agency is marked by the attempts of TSOs to identify weak spots in the system. However, we can also identify a weak form of agency in shaping the system, as TSOs may be forced to accept a given role or even exceed their capacities to maintain their position in the public service system.

3. Dependency-driven collaboration agency in the service system context reveals the ugly games of collaboration. The spirit of collaboration is violated, as one party is financially or institutionally dependent on the other. Although public organisations can also depend on TSOs, from the perspective of this discourse, TSOs have limited options to shape the system.

In sum, it is possible to identify bidirectional tensions and a strong interconnectedness in the collaboration between public organisations and TSOs. These tensions and interconnectedness shape the system. Ideally, public organisations benefit from the civil knowledge and innovative, user-centred support services offered by TSOs, which, for their part, use the collaboration-friendly environment to their own and the system’s benefit. Conversely, if the allocated space for collaboration is narrow and inflexible, the development impulses of the TSOs might be difficult to detect, refine, and utilise.

The identified forms of collaboration agency can exist simultaneously in a single TSO, underlining the complex, even paradoxical, and multifaceted nature of TSO–public sector collaboration, with various dependencies and collaboration logics. The relevant discourses reflect an interconnected public service system, which is constantly in flux and in which public organisations operate both with collaboration and top-down management logics. Collaborative governance both sets expectations and shapes the agency of TSOs, but at the same time, TSOs can use opportunities to their own advantage by taking strategic actions and constantly reshaping their collaboration with public organisations. Despite the hurdles facing TSOs due to their financial or other dependencies on public organisations, the results underline their strong strategic agency in terms of collaboration.

The research strategy has also certain limitations. It was conducted in the context of social welfare and healthcare, which naturally affects the results. Studies focusing on TSOs’ forms of collaboration agency in other fields could produce different results. Moreover, this study was based on qualitative data in the specific context of the Finnish public service system. The findings are not generalisable beyond this specific context, despite offering insights into other politico-administrative contexts.

Despite the limitations, the results of our study can contribute to various streams of literature. First, our study contributes to research focusing on TSO–public organisation collaboration and relations. Our results are relevant to previous studies critically examining the relations between TSOs and public organisations, also reflecting the previously discussed ‘manufacturing’ role of governments (Brandsen & van Hout, Reference Brandsen and van Hout2006; Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Martin, Reference Martin2011; Pape et al., Reference Pape, Brandsen, Pahl, Pieliński, Baturina, Brookes and Chaves-Ávila2020; Peeters, Reference Peeters2013). We identified different discourses that shed light on passive service integration, responsibilisation, and financial and other forms of dependencies, as portrayed by TSOs. The limiting nature of collaboration that arises from an imbalance in power relations cannot be discarded.

However, at the same time, we identified an active strategic agency of TSOs, even in situations characterised by imbalanced power relations. This is in line with Arvidson et al., (Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018, p. 854), who found that refraining from criticism is a deliberate choice of TSOs and that their ‘self-perception’ affects the perceived room for advocacy and freedom to criticise. Accordingly, our analysis shows that it is essential to take into account the perceived ability of TSOs to criticise public organisations. This notion sheds lights on the ways TSOs cope with imbalanced power relations in collaboration in different ways. s The strong, strategy-oriented agency discourse coexisted with a weak, stability-seeking agency discourse. Some TSOs were more confident of their position and recognised the bidirectional dependencies in collaboration. Collaboration between TSOs and public organisations can be seen as a balancing act that can be negotiated. Salamon and Toepler (Reference Salamon and Toepler2015, p. 2171) note that there is a need for balance between the needs of public organisations—for accountability, for instance—and TSOs’ need for self-determination and independence.

Second, our study offers an approach to portraying the collaboration between TSOs and public organisations. Typologically, it can be linked with previous models focusing on NGO–government relations. The Four-C’s model proposed by Najam (Reference Najam2000), which describes the relationships between NGOs and governments as confrontational, co-optive, complementary, and cooperative, underlines the diverging and converging institutional interests and the strategic nature of forming such relations. Moreover, the model of government–non-profit organisation relations as supplementary, complementary, and adversarial, proposed by Young (Reference Young2000) based on international comparisons, also supports the findings of our study. According to Young, such relations are multilayered and flowing with societal changes and trends.

In line with both studies, our study shows that there are no simple explanatory categories but a wide spectrum of roles, agency, and collaboration logics in TSO–public organisation collaboration. Our study also adds a new angle to the range of typologies, especially based on its methodology. We adopted an inductive approach to examining the collaboration agency of TSOs. Although our study was broader than a case study, we managed to gain a thorough understanding of TSOs’ perceptions using a small study sample. Our discourse analysis offers a tool for organising individual descriptions of experiences into a broader, abstract level.

Conclusions

In this study, we asked how TSOs portray their collaboration with public organisations and what kinds of collaboration agency can be identified based on these descriptions? The study focused on the concept of collaborative governance to gain understanding of the nature of the collaboration between public organisations and TSOs in the field of social welfare and health.

With this approach, our study offers insights into the nature of collaborative governance, which is often presented in a positive light, especially in policy documents (Batory & Svensson, Reference Batory and Svensson2019; Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Nabatchi and Balogh2012). The TSO–public organisation collaboration analytical lens reveals that collaborative governance involves a variety of operation logics, including coercive ones. Public organisations indeed use collaborative governance as a steering mechanism, even ‘manufacturing’ TSOs (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017). In line with Salamon and Toepler (Reference Salamon and Toepler2015), our study shows that to be truly collaborative, there is certainly room for more co-planning and co-designing in the collaboration between TSOs and public organisations. TSOs must fill the gaps or otherwise modify their operations according to the needs of public organisations. Therefore, to view collaborative governance from the perspective of the ‘politics of naming’ (Batory & Svensson, Reference Batory and Svensson2019), critical approaches are needed to recognise and illuminate the variety of collaboration logics, which also include coercive features.

The autonomy and authenticity of TSOs is a crucial question concerning the realisation of collaborative governance. There is an ongoing debate on whether collaboration with public organisations poses a risk for TSOs in this respect (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Martin, Reference Martin2011; Najam, Reference Najam2000). Our study contributes to this discussion, as our findings show that TSOs themselves focus on collaboration opportunities at the level of service production by seeking weak points and gaps in the service system rather than by focusing on advocacy work. This strategic choice can be explained by their desire for stability in the framework of imbalanced power relations. When a TSO obtains an established position in the public service system, it tends to develop a sense that its future is relatively secure. However, its collaboration agency may still be weak if there is no room for shaping the conditions for collaboration or the system itself. The risk that collaboration poses for TSOs is one of losing their authenticity when evolving too much to fulfil the system’s requirements.

One may ask whether TSOs consciously or unconsciously identify this risk and whether this is an active choice overall. This question indicates potential avenues for future research. Our findings show that TSOs are constantly alert to collaboration opportunities in a turbulent policy environment. They also constantly build strategic collaborations at the personal and policy levels. Against this backdrop, the choice to focus on supportive services in the service system context makes sense. However, it is essential to examine whether TSOs consider this kind of collaboration to be advocacy work and how it might be possible to assume an advocacy role in these settings—for instance, by training their members in advocacy skills. As Martin (Reference Martin2011, p. 913) notes, TSOs have the chance to reinvigorate their advocacy function instead of focusing merely on improving their own services according to a ‘business-oriented mode of operating’ through facilitating co-production activities.

This study focused on collaboration agency from the perspective of TSOs. However, there may be room for studying public organisations in the same way: What kinds of collaboration agency can be found in public organisations working with TSOs? Finally, it is important to highlight the finding concerning the strong strategic agency of TSOs in collaboration scenarios. It seems worthwhile to investigate their activities and strategic actions in different politico-administrative contexts and different kinds of services.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Vaasa (UVA).

Declarations

Ethical Approval

APA ethical standards were followed in the conduct of the study.

Appendix

See Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of the informants and NGOs

Interviewee |

Scope of operations |

Range of operations |

Service production |

|---|---|---|---|

Manager |

General citizen participation and empowerment, community approach |

National |

Yes |

Manager |

Patient organisation, support for families, support for research |

Regional |

Yes |

Planning officer |

Patient organisation, health promotion |

National |

Yes |

Specialist |

Patient organisation, health promotion |

National |

No |

Manager |

Mental health promotion and advocacy |

National |

Yes |

Manager |

Support and advocacy for families with special needs |

National |

No |

Manager |

Support and advocacy for families with special needs |

National |

No |

Manager |

Multifaceted volunteering functions for social welfare and health promotion |

National |

Yes |

Planning officer |

Health and social welfare promotion and advocacy for young people |

National |

No |

Support and advocacy for disabled persons |

National |

No |

|

Specialist |

Support and advocacy for disabled persons |

National |

Yes |

Group interview: manager, sub-manager, counsellor |

Inequity prevention, community approach |

Local |

No |