Management Implications

Imperata cylindrica (cogongrass) is one of the most troublesome invasive plants in natural areas due to its pyrogenic nature, aggressive rhizomatous growth, and a limited number of effective control options. Field practitioners commonly rely on glyphosate and imazapyr for I. cylindrica control due to logistical feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and the vast scale of infestations. Emerging threats such as climate change, hybridization, and resistance development may alter invasion dynamics, reduce treatment efficacy, and increase long-term management uncertainty. These factors underscore the need for diverse chemical management tools with differing mechanisms of action, especially for importunate invasives such as I. cylindrica. Due to increasing scrutiny of and restrictions on glyphosate usage, it is essential to develop a robust suite of alternative chemical control options to maintain effective invasive plant management techniques. This study tested glufosinate alone and in tank mixtures with imazapyr and glyphosate to evaluate efficacy for I. cylindrica compared with the common management standard of glyphosate + imazapyr. Based on our results, a stand-alone treatment of glufosinate applied at 2.0 kg ae ha−1 did not provide acceptable control compared with imazapyr or glyphosate alone at 540 d after treatment (DAT). Glufosinate alone may not achieve efficacy comparable to either imazapyr or glyphosate alone when targeting perennial, rhizomatous grasses such as I. cylindrica. However, tank mixes of glufosinate + imazapyr demonstrated acceptable control and were not different from glyphosate + imazapyr at 540 DAT. Natural area managers seeking an effective glyphosate alternative may consider glufosinate + imazapyr tank mixtures for I. cylindrica control.

Introduction

Cogongrass [Imperata cylindrica (L.) P. Beauv.] is an aggressive, rhizomatous grass originating from East Asia (Lucardi et al. Reference Lucardi, Wallace and Ervin2014; Reference Lucardi, Wallace and Ervin2020). Since its initial detection in 1911 in Alabama, I. cylindrica has been an increasing threat across much of the southeastern United States (Hejazi et al. Reference Hejazi Rad, Duque, Flory, Nascimento, Mendes, Maciel, Santos, da Silva and Shabani2025; Lucardi et al. Reference Lucardi, Wallace and Ervin2020; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2004; Tabor Reference Tabor1949). It is ranked among the world’s worst weeds due to its cosmopolitan distribution and extensive impacts to agricultural systems and natural areas (Holm et al. Reference Holm, Pucknett, Pancho and Herberger1977; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2004). This perennial C4 grass presents significant challenges for management in natural areas, primarily due to its rapid spread and regeneration from rhizomes. Imperata cylindrica rhizomes are drought tolerant, store considerable energy as nonstructural carbohydrates, and can quickly sprout and spread depending on their size and growth stage (Ayeni and Duke Reference Ayeni and Duke1985; Coster Reference Coster1932; Soerjani Reference Soerjani1970). Peninsular Florida populations of I. cylindrica are thought to typically spread asexually, primarily because of the low seed-fill rates observed (Burrell et al. Reference Burrell, Patterson and Bryson2003; Dozier et al. Reference Dozier, Gaffney, McDonald, Johnson and Shilling1998; Lowenstein Reference Loewenstein2011).

Despite extensive research into various control methods, effective I. cylindrica management in natural areas largely relies on chemical means, particularly foliar applications of glyphosate and imazapyr (Dickens and Buchanan Reference Dickens and Buchanan1975; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2004; Minogue et al. Reference Minogue, Miller and Lauer2012; Willard et al. Reference Willard, Gaffney and Shilling1997). Glyphosate is a broad-spectrum systemic acid formulation that targets aromatic amino acid production (Shaner and Beckie Reference Shaner2014). Imazapyr is a broad-spectrum formulation that inhibits acetolactate synthase but is also absorbed through the soil profile (Shaner and Beckie Reference Shaner2014). While these treatments can result in significant reductions in live rhizome biomass, repeated applications are still required for effective long-term control (Aulakh et al. Reference Aulakh, Enloe, Loewenstein, Price, Wehtje and Miller2014). Imazapyr is particularly effective in controlling I. cylindrica through both foliar and soil activity—which is especially important for targeting belowground meristems (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2002). However, glyphosate activity is completely dependent upon foliar absorption, making application timing somewhat more critical, as its effectiveness improves when applied during active translocation of photosynthates to the roots and rhizomes (Byrd Reference Byrd2007; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2004). Imazapyr use is often limited by the potential for non-target damage in mixed plant communities, especially for many hardwood species.

While glyphosate continues to be broadly recommended for natural area weed management (Benbrook Reference Benbrook2016), it faces increasing scrutiny due to recent reclassification by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a probable carcinogen (Guyton et al. Reference Guyton, Loomis, Grosse, El Ghissassi, Benbrahim-Tallaa, Guha, Scoccianti, Mattock and Straif2015). This has driven several cities and municipalities to impose bans or restrictions on its use on public lands and waters (Gandhi et al. Reference Gandhi, Khan, Patrikar, Markad, Kumar, Choudhari, Sagar and Indurkar2021). The limitations of imazapyr in many operational situations, coupled with possible limitations or future regulatory decisions regarding glyphosate, underscore the need for research to explore and evaluate effective alternative herbicides.

Over the past several decades, few alternative herbicides have demonstrated effective control of I. cylindrica in agricultural, rights-of-way, or natural area settings (Dickens and Buchanan Reference Dickens and Buchanan1975; Enloe et al. Reference Enloe, Belcher, Loewenstein, Aulakh and van Santen2012; Hinkson et al. Reference Hinkson, NeSmith, Alba, Durham, Ferrell and Flory2024; Parker Reference Parker and Terry1970; Teymourinia et al. Reference Teymourinia, Chitband and Khayrandish2023). One herbicide that remains under-tested for recalcitrant grasses within natural areas is glufosinate. Glufosinate (2-amino-4-(hydroxymethylphosphinyl) butanoic acid) is a nonselective herbicide with primarily contact activity that inhibits glutamine synthase, causing rapid phytotoxicity in susceptible plants (Shaner and Beckie Reference Shaner2014; Takano et al. Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2019, Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2020; Takano and Dayan Reference Takano and Dayan2020). Glufosinate has become a widely used chemical option in agricultural weed control, especially for genetically modified glufosinate-resistant crop production such as corn (Zea mays L.), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Bradley, Burns, DeWerff, Dobbels, Essman, Flessner, Gage, Hager, Jhala, Johnson, Johnson, Lancaster, Lingenfelter and Loux2025). In areas where regulations have limited or prevented the use of glyphosate, glufosinate is quickly becoming a comparable lawn and ornamental site chemical control option for a wide array of weed species (Marble et al. Reference Marble, Neal and Senesac2020). Glufosinate inhibits glutamine synthetase, a critical enzyme responsible for amino acid metabolism and photorespiration, leading to massive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2020). Effective applications cause chlorosis and wilting on susceptible plants within 3 to 5 d, with complete necrosis by 1 to 2 wk (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Bradley, Burns, DeWerff, Dobbels, Essman, Flessner, Gage, Hager, Jhala, Johnson, Johnson, Lancaster, Lingenfelter and Loux2025; Shaner and Beckie Reference Shaner2014). Preliminary studies with glufosinate applied to I. cylindrica have shown rapid leaf necrosis but limited long-term control due to regrowth from rhizomes (Byrd Reference Byrd2007; Gaffney Reference Gaffney1996). This is likely due to significant contact activity of glufosinate, minimal absorption via plant roots in field conditions, and subsequent rapid microbial breakdown of the herbicide within soil (Shaner and Beckie Reference Shaner2014). Adequate perennial grass control is extremely difficult to achieve if the applied herbicide is not effectively translocated throughout the plant.

Glufosinate’s mechanism of action and environmental influences complicate direct translation of agricultural research to natural area management, where objectives, acceptable control standards, and evaluation timelines differ significantly. Most agricultural weed control studies are therefore limited in relevance for natural area applications due to short observation periods, differing control standards, and the feasibility of mechanical control options. Agricultural weed management typically measures control with visual estimation and aims to reduce impacts on crop yield rather than achieve complete elimination of the target species. Natural area weed management often focuses instead on local patch eradication and includes more amorphous ecological goals that require greater logistical planning and costs for application. Nevertheless, some findings from agricultural contexts may still provide insight into glufosinate’s potential efficacy for non-crop sites. Early agricultural testing of glufosinate in citrus demonstrated adequate control of I. cylindrica using 4 kg ha−1 (Singh and Tucker Reference Singh and Tucker1987). Glufosinate applied at 0.983 kg ha−1 achieved 64% to 98% control of nutsedge [Cyperus rotundus L.] within 4 wk (Sharpe and Boyd Reference Sharpe and Boyd2019). On another rhizomatous C4 grass, johnsongrass [Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers.], glufosinate provided 75% control and 63% height reduction at 0.7 kg ha−1, with a subsequent application of 0.6 kg ha−1 (Landry et al. Reference Landry, Stephenson and Woolam2016). Repeat applications may be required for satisfactory control, as demonstrated by three applications of 0.88 kg ha−1, followed by a 0.59 kg ha−1 treatment, which resulted in 97% S. halepense control at 21 d after treatment (DAT) of the final glufosinate application (Landry et al. Reference Landry, Stephenson and Woolam2016). Although glufosinate has proven effective in managing various agricultural weeds, its efficacy for I. cylindrica control in natural areas remains understudied as a tank-mix partner with other herbicides, warranting further field trials.

Herbicide tank mixes offer several advantages for invasive species management, including enhanced control, resistance mitigation (Heap Reference Heap2014), and reduced application frequency. Combining multiple sites of action can improve efficacy and minimize the need or total area for repeat applications, therefore reducing overall required herbicide use. For example, mixing imazapyr with glyphosate has proven effective for I. cylindrica control, providing both rapid burndown and prolonged residual activity (Aulakh et al. Reference Aulakh, Enloe, Loewenstein, Price, Wehtje and Miller2014; Minogue et al. Reference Minogue, Miller and Lauer2012; Willard et al. Reference Willard, Gaffney and Shilling1997). Some agricultural investigations have found differing interactions with glufosinate + glyphosate tank mixes dependent upon the target species (Bethke et al. Reference Bethke, Molin, Sprague and Penner2013; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Norsworthy and Kruger2020). There exists some previous work using glufosinate in natural areas (Byrd Reference Byrd2007; Gaffney Reference Gaffney1996). However, tank mixes of glufosinate with key I. cylindrica herbicides remain undertested in field trials of natural area settings. A combination of glufosinate and imazapyr may provide both rapid necrosis and long-term soil activity, potentially resulting in improved I. cylindrica control. Concomitantly, the response of I. cylindrica to combinations of glufosinate and glyphosate in natural area field conditions with long-term data collection remain undertested.

Based on current literature, single herbicide applications are not expected to completely eradicate a colony of I. cylindrica due to its obdurate nature (Aulakh et al. Reference Aulakh, Enloe, Loewenstein, Price, Wehtje and Miller2014; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2004). Although not a long-term field-applicable method, single application experimentation with cover data collected during the growing season at least 1 yr following application informs of treatment efficacy based on regrowth. Such research can also inform of optimal re-treatment interval timing based on this same recovery metric. We suggest that chemical treatment of I. cylindrica in natural area contexts can be considered viable if initial treatment results in 80% or greater control of a treated area observed the following growing season based on previous literature (Aulakh et al. Reference Aulakh, Enloe, Loewenstein, Price, Wehtje and Miller2014; Minogue et al. Reference Minogue, Miller and Lauer2012) and due to the high costs and logistical requirements of large-scale re-treatment.

Given the need for alternative herbicides for I. cylindrica control and the uncertainty of glufosinate interaction as a tank-mix partner with currently relevant herbicides, the objective of this study was to evaluate glufosinate efficacy for chemical treatment of I. cylindrica in natural areas and investigate potential benefits of combining glufosinate with imazapyr or glyphosate for improved long-term control. If successful, this could benefit land managers greatly as a novel treatment approach or glyphosate alternative for an otherwise seemingly indomitable weed species.

Materials and Methods

Three study locations situated by latitude on Peninsular Florida, were selected and established (Table 1). The first was located in Gainesville, FL, at the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants (29.724694, −82.417083), the second was near Bream Lake in the Ocala National Forest (29.203472, −81.938278), and the third was located in Little Manatee River State Park (27.688111, −82.345000). The Gainesville study locale was situated within a pine flatwood with an overstory dominated by longleaf pine [Pinus palustris Mill.] and American sweetgum [Liquidambar styraciflua L.], with a common understory of hairy indigo [Indigofera hirsuta L.], American burnweed [Erechtites hieraciifolius (L.) Raf. ex DC.], dogfennel [Eupatorium capillifolium (Lam.) Small], and sand blackberry [Rubus cuneifolius Pursh]. Soils were largely composed of Plummer fine sand (loamy, siliceous, subactive, thermic Grossarenic Paleaquults), mixed with a minority of Mulat (loamy, siliceous, subactive, thermic Arenic Endoaquults) and Pomona sands (sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Ultic Alaquods). Mean temperature in Gainesville during the study period was comparable to historical averages, and annual precipitation was only somewhat greater (+37.4 cm) than historical averages (Florida Climate Center 2025; NOAA 2025).

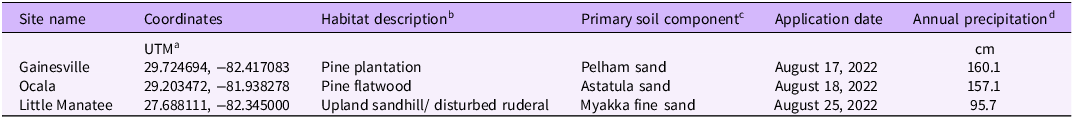

Table 1. Site-specific information for field trials.

a Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system.

b Habitat determination conducted by informal visual observation.

c Soil data retrieved from USGS WSS (Soil Survey Staff 2024).

d Total observed precipitation 1 yr following application date (NOAA 2025).

The Ocala study site was also located within a pine flatwood with an overstory of P. palustris mixed with a variety of oaks, including live oak [Quercus virginiana Mill.], laurel oak [Quercus laurifolia Michx.], and turkey oak [Quercus laevis Walter]. Commonly observed understory species included muscadine [Vitis rotundifolia Michx.], earleaf greenbrier [Smilax auriculata Walter], American beautyberry [Callicarpa americana L.], winged sumac [Rhus copallinum L.], wiregrass [Aristida spiciformis Elliott], and R. cuneifolius. Soils in this study area were completely composed of Astatula sand (hyperthermic, uncoated Typic Quartzipsamments). Mean temperature in Ocala was comparable to historical averages, and annual precipitation was somewhat greater (+25.9 cm) compared with historical averages (Florida Climate Center 2025; NOAA 2025).

The Little Manatee River State Park study location was positioned within an upland sandhill with very limited overstory of scattered Q. virginiana, mixed with an understory of wax myrtle [Morella cerifera (L.) Small], Brazilian peppertree [Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi], E. capillifolium, R. cuneifolius, common ragweed [Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.], horseweed [Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist var. canadensis], and I. hirsuta. Soils at this site were entirely composed of Myakka fine sand (sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Aeric Alaquods). Mean temperature in Little Manatee was comparable to historical averages, and annual precipitation was less than historical averages (−30 cm) (Florida Climate Center 2025; NOAA 2025).

At both the Gainesville and Little Manatee locations, 28 field plots measuring 6.10 by 9.14 m were established using PVC poles, tagged for reference, and geolocated in dense, healthy populations of I. cylindrica. The Ocala location maintained a similar setup as previously mentioned, with the only difference being a limitation in the size of the study area, which resulted in only 21 plots. Field plots at each location were assigned one of seven treatments, which resulted in four replicate plots per treatment at the Gainesville and Little Manatee sites, and three replicate plots per treatment at the Ocala study site. Treatments were arranged in a completely randomized design, and applications for each site all occurred within a 9-d period in late August 2022. Application during summer ensured the target plant was actively growing.

Treatments tested in this study consisted of glufosinate (Interline®, UPL, King of Prussia, PA), glyphosate (Roundup Custom®, Bayer, St Louis, MO), and imazapyr (Polaris®, Nufarm, Alsip, IL) herbicides applied individually and in combination with each other (Table 2). A non-treated control treatment was also included for reference. Adjuvants for all treatments included a water-conditioning agent (Quest®, Helena AgriEnterprises, Collierville, TN) at 0.5% v/v, methylated seed oil (MSO Concentrate, Loveland Products, Greeley, CO) at a 1.0 % v/v, and a blue spray indicator (Mystic HC, Winfield Solutions, St Paul, MN) at 0.44% v/v. All water used for treatments was obtained from local municipal sources.

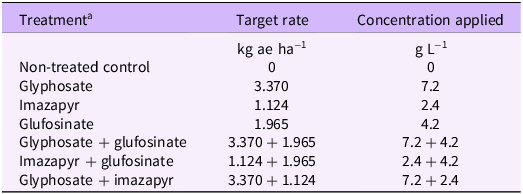

Table 2. Treatment rate and application details.

a All treatments included 1% v/v methylated seed oil, 0.44% v/v blue spray indicator, and a water-conditioning agent at 0.5% v/v.

A single-nozzle application approach was selected for use, because broadcast applications with a boom sprayer were not possible due to tree overstory within the plots. Treatments were applied at 207 kPa using a CO2-pressurized single-nozzle sprayer (R&D Sprayers, Bellspray, Opelousas, LA) mounted on an ATV (2005 Honda Foreman ES TRX500FE, Honda Motor Company, Tokyo, Japan). During application, each treatment was made using a two-person system that worked in tandem (one driver, one applicator) to administer 468 L ha−1 of treatment solution for designated field plots as evenly as possible. The spray wand was equipped with a single 6003 flat--fan spray nozzle (TeeJet® Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL). While terrain, trees, and other driving hazards such as stumps and fallen logs varied between each of the three research locations, application volumes per treatment were found to be consistent across treatments (data not shown).

Baseline data were collected at 0 DAT for each plot and included percent I. cylindrica cover. Posttreatment cover evaluations then took place at 14, 30, 270, 360, and 540 DAT. Non-target cover was also collected at 360 DAT for all identifiable vascular plants and categorized by species. When species-level identification was not possible, plants were identified to genus. Percent cover estimates were made visually over an entire plot basis on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 indicates no live green leaves and culms, and 100 indicates complete plot coverage of live green leaves and culms. Additionally, rhizome biomass was sampled at three randomly determined locations within each plot at 360 DAT. During each rhizome sampling, manually excavated soil samples were carefully made using a sharpened flat-bladed shovel (Anvil, Home Depot Product Authority, Atlanta, GA) that functioned to develop four 17.8-cm-wide 90° cuts vertically to the full 27.9-cm depth of the shovel blade into the ground. This created a 17.8 by 17.8 by 27.9 cm (8,840 cm3) sample cube that was carefully extracted. Belowground I. cylindrica rhizome biomass from each sample was coarsely hand sifted to remove excess soil, oven-dried at 71.1° C (160° F) for 120 h, resifted using a 4,000-micron (5-mesh) sieve (Stainless Steel Metal Sieve, Fieldmaster™, Frey-Scientific Inc., Greenville, WI), and weighed (Pioneer™, Ohaus Corporation, Parsippany, NJ). All other vegetative material that was not classified visually as live I. cylindrica rhizome was discarded. Fibrous roots from I. cylindrica did not represent a significant portion of any samples after processing. Biomass weights (grams) were averaged per plot and normalized (to kg ha−1) for statistical analyses. Percent control for I. cylindrica cover and biomass was calculated using the following equations:

$$\begin{align}{\rm{Percent \ control}} = &\left( {{{{\rm{Mean\; biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{control}}}} - {\rm{Mean \;biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{treament}}}}}}\over{{{\rm{Mean\; biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{control}}}}}}} \right) \\&\times 100\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\rm{Percent \ control}} = &\left( {{{{\rm{Mean\; biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{control}}}} - {\rm{Mean \;biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{treament}}}}}}\over{{{\rm{Mean\; biomas}}{{\rm{s}}_{{\rm{control}}}}}}} \right) \\&\times 100\end{align}$$

Statistical analysis compared treatments in terms of I. cylindrica cover by evaluation date, I. cylindrica rhizome biomass at 360 DAT, and non-target cover at 360 DAT. The analysis of all locations used location means in a linear mixed model with location incorporated as a random effect. Linear mixed-model estimates were obtained using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Individual locations (completely random design) estimates were obtained using the lm function (R Core Team Reference Core Team2024). Normality of model residuals was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test as well as QQ plots, KS tests, and outlier tests using the DHARMa package (Hartig Reference Hartig2022). This resulted in the use of the arcsine square-root transformation for percent cover variables and the log transform for biomass. The emmeans package (Lenth Reference Lenth2024) was used for mean comparisons. Treatment means were back transformed for summaries and compared using Tukey’s adjustment for multiplicity (5% level).

The analysis of individual locations was also used to determine whether treatments varied by location. This level of analysis was particularly important for rhizome biomass and non-target cover, as both varied by location One glufosinate-treated plot at the Gainesville location did not receive treatment due to applicator error and was therefore excluded from the analysis.

Results and Discussion

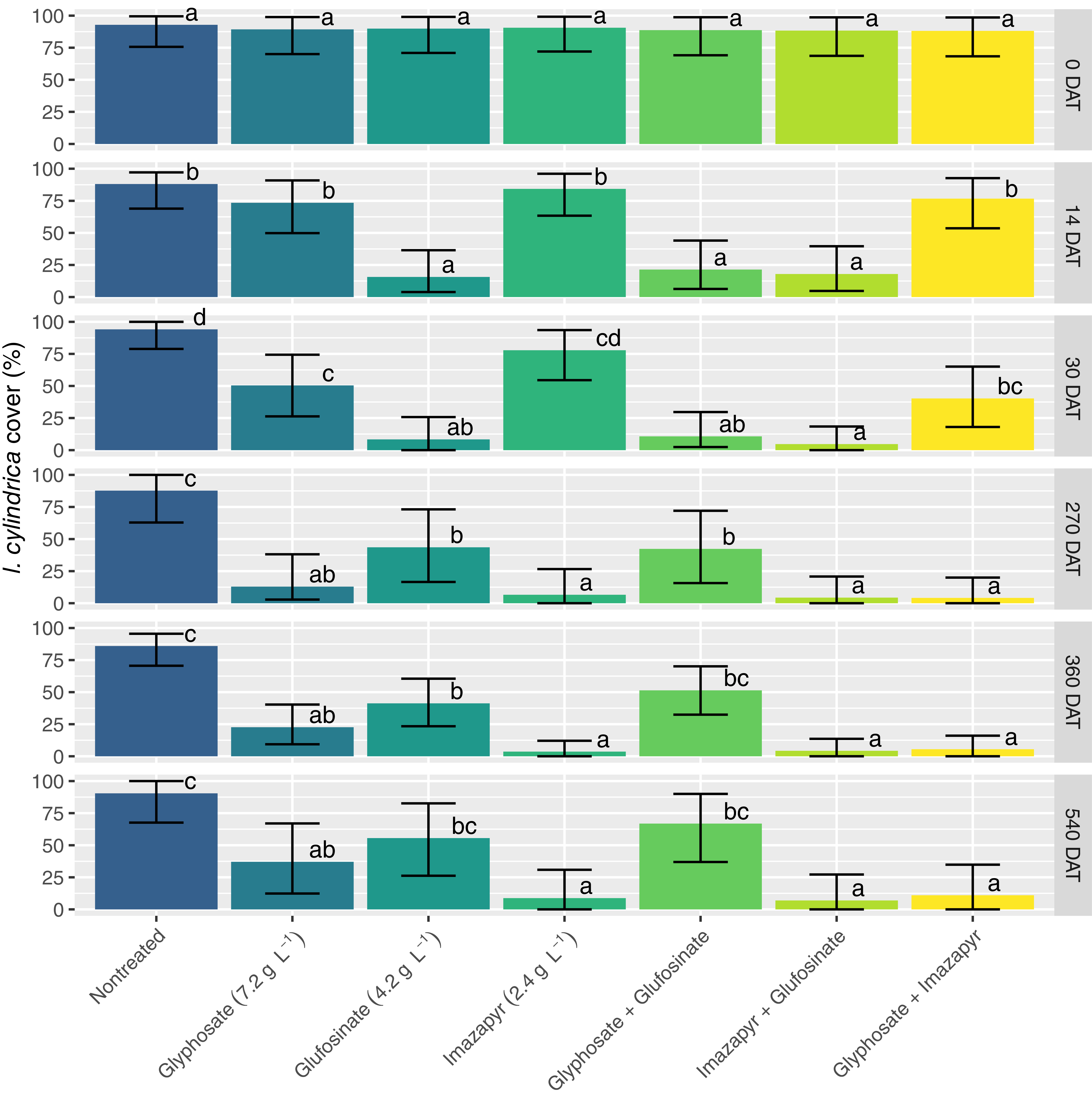

Throughout the study, percent cover of I. cylindrica in non-treated control plots remained consistently high, with mean cover ranging from approximately 80% to 92% across all sampling dates (August 2022 to February 2024). At 14 DAT, all treatments containing glufosinate (glufosinate, glufosinate + imazapyr, and glufosinate + glyphosate) resulted in rapid foliar burndown of I. cylindrica (Figure 1). These treatments exhibited significantly lower I. cylindrica cover compared with the glyphosate, imazapyr, and non-treated control treatments. This trend was also apparent at 30 DAT. Glyphosate alone and the tank mix of glyphosate + imazapyr, but not imazapyr alone, also reduced foliar cover compared with the non-treated control. The rapid contact-type activity of glufosinate was in clear contrast to the much slower action of both glyphosate and imazapyr.

Figure 1. Imperata cylindrica cover averaged across all locations for each evaluation (DAT, days after treatment). Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means for a given DAT with the same letter are not significantly different using Tukey’s adjustment at the 5% level.

By late spring the following year (270 DAT), all herbicide treatments reduced I. cylindrica cover compared with the non-treated control (Figure 1). Imperata cylindrica cover was still significantly lower in the glufosinate-alone treatment compared with the non-treated control. All treatments containing imazapyr resulted in significantly lower I. cylindrica cover than the glufosinate-alone and glufosinate + glyphosate treatments. However, these were not different from cover in the glyphosate-alone treatment. This pattern of herbicide activity was very similar by late summer (360 DAT), with the only difference being that I. cylindrica cover in the glyphosate + glufosinate tank mix was not different from the non-treated control. Although not quantified in this study, the poor I. cylindrica control observed in this treatment may suggest potential antagonism between glyphosate and glufosinate on this grass species. Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Norsworthy and Kruger2020) found tank mixes of the two herbicides to be antagonistic on other grasses, including large crabgrass [Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.] and broadleaf signalgrass [Urochloa platyphylla (Munro ex C. Wright) R.D. Webster]. However, they tested lower rates and suggested less antagonism at higher rates, which may explain the outcome in the current study.

At 540 DAT, the pattern of herbicide treatments was almost identical to 360 DAT, with the exception of glufosinate alone and glufosinate + glyphosate, which were not different from the non-treated control. All treatments that contained imazapyr resulted in less than 10% I. cylindrica cover, and these were different from all other treatments except glyphosate alone (Figure 1). Although some recovery was evident in the glyphosate-alone treatment, cover was still lower than in the non-treated control. Cover in the glyphosate-alone treatment did not differ from the glufosinate alone or glyphosate + glufosinate tank mix.

While reduction in plant cover is a useful metric for assessing herbicide treatment effectiveness, the reduction of perennating underground biomass is known to be the most accurate evaluation of long-term chemical efficacy for I. cylindrica control (Enloe et al. Reference Enloe, Belcher, Loewenstein, Aulakh and van Santen2012; Willard Reference Willard1988; Willard et al. Reference Willard, Gaffney and Shilling1997). Despite apparent uniform foliar cover across locations, belowground biomass between I. cylindrica patches may vary substantially and may depend upon site conditions, soil type, or age of infestation (Ayeni and Duke Reference Ayeni and Duke1985; Coster Reference Coster1932; Soerjani Reference Soerjani1970).

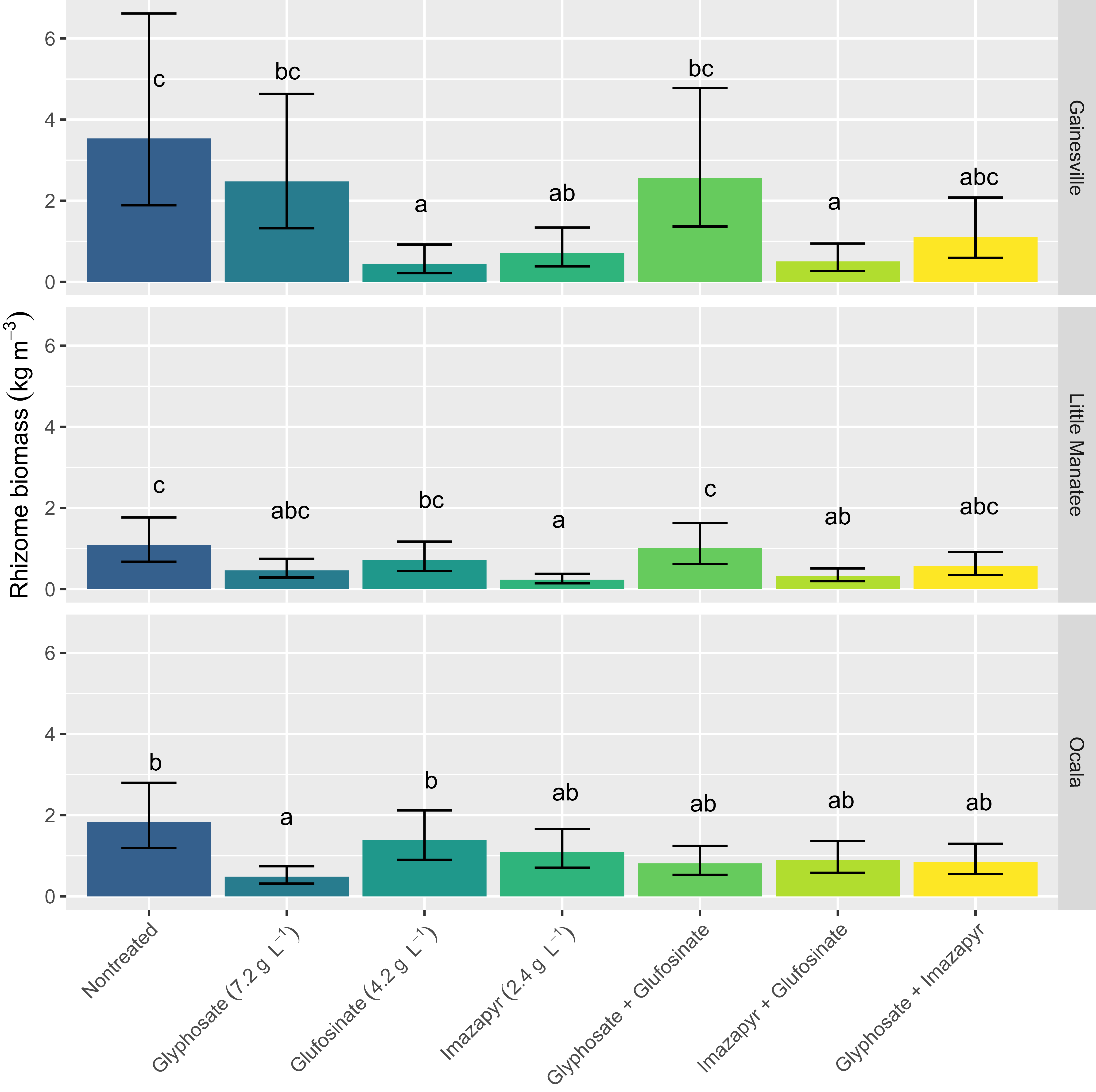

When rhizome biomass response at 360 DAT was analyzed separately across sites, there was considerable variation among herbicide treatments (Figure 2). At the Gainesville location, glufosinate applied alone, imazapyr applied alone, and the tank mix of the two were the only treatments to reduce rhizome biomass compared with the non-treated control. These were not different from the commercial standard glyphosate + imazapyr treatment. At Little Manatee, imazapyr applied alone and imazapyr tank mixed with glufosinate were the only treatments to reduce rhizome biomass compared with the non-treated control. Again, these were not different from the glyphosate + imazapyr treatment. At Ocala, only glyphosate applied alone reduced rhizome biomass compared with the non-treated control. However, non-treated control was not different from any other herbicide treatment. Sampling methodology that provides consistent sample size and reduces error from manual shovel excavation may also be a worthwhile improvement that reduces variation. Future studies should develop standard underground sampling methodologies that clarify the necessary sample volume that adequately measures rhizome density. Without such an understanding, the use of belowground biomass data to provide statistical support for evaluating treatments is not feasible.

Figure 2. Rhizome biomass at 360 d after treatment (DAT) for each location. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means for a given location with the same letter are not significantly different using Tukey’s adjustment at the 5% level.

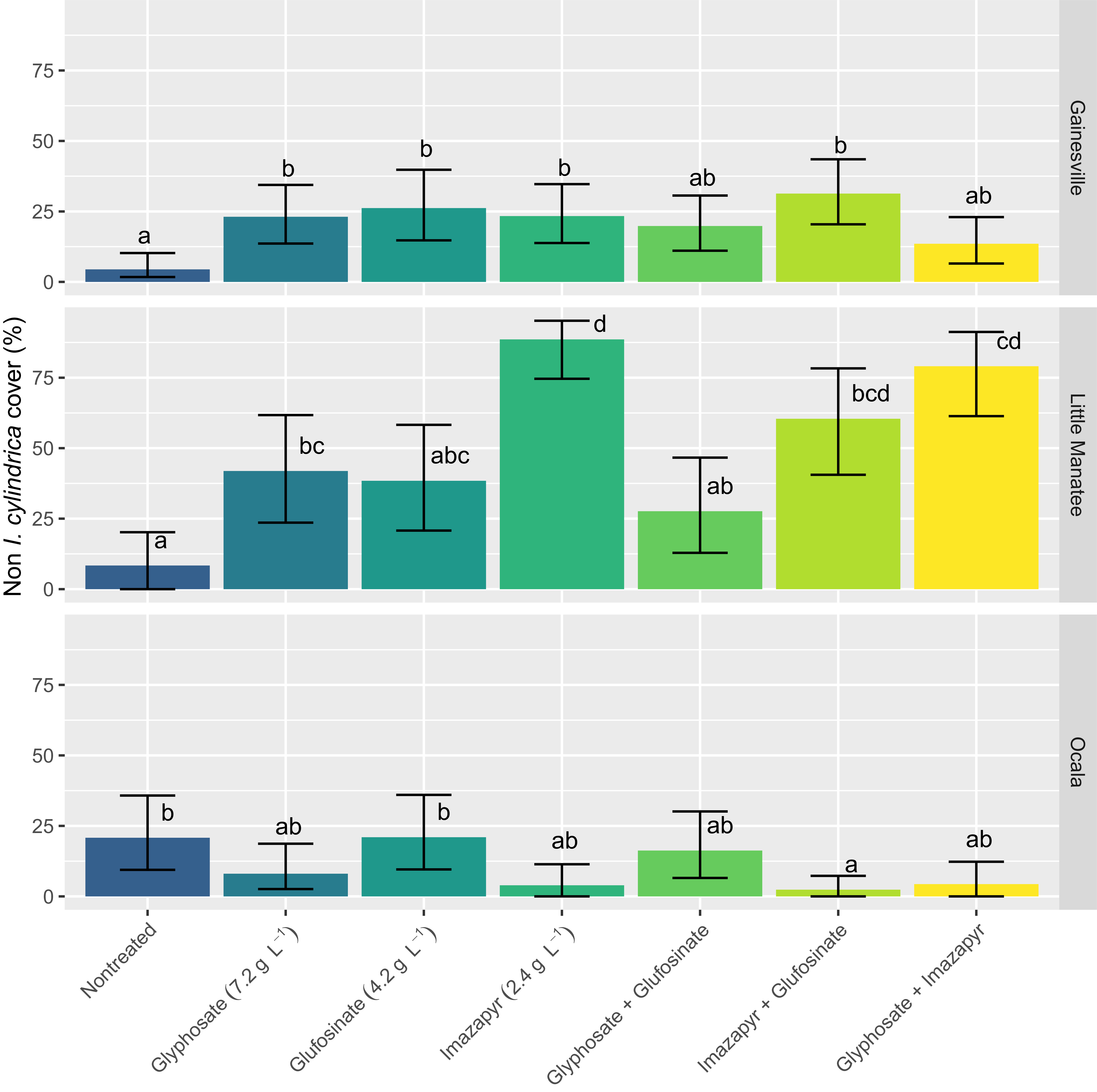

In addition to target efficacy, the posttreatment plant community response is of interest, especially within a restoration context (Hinkson et al. Reference Hinkson, NeSmith, Alba, Durham, Ferrell and Flory2024). In our field plots, the posttreatment non-target species composition at 360 DAT varied by site (Figure 3) and was generally quite limited in diversity. At Gainesville, glyphosate-alone, glufosinate-alone, imazapyr-alone, and imazapyr + glufosinate treatments resulted in higher non-target cover than the non-treated control. Non-target cover consisted mainly of I. hirsuta (10%), R. cuneifolius (6%), E. hieraciifolius (4%), and L. styraciflua (1%). At Little Manatee, glyphosate alone, imazapyr alone, imazapyr + glufosinate and glyphosate + imazapyr resulted in higher non-target cover than the non-treated control. At this site, non-target cover consisted mainly of E. capillifolium (18%), C. canadensis var. canadensis (15%), A. artemisiifolia (12%), and R. cuneifolius (11%). At Ocala, only the imazapyr + glufosinate treatment reduced non-target cover compared with the non-treated control. Non-target cover was extremely limited across the study and consisted of Quercus spp. (7%), S. auriculata (3%), and Vitis spp. (1%). Across all three sites, the generally depauperate flora precluded meaningful differences among species between herbicide treatments. The lack of consistent non-target posttreatment response among sites is likely due to a combination of site-specific factors, including the existing soil seedbank, proximity of wind-dispersed species, and general tolerance of non-target plants to herbicide treatments. For example, I. hirsuta and R. cuneifolius generally have a long-lived soil seedbank and recover quickly following imazapyr treatments. Erechtites hieraciifolius, E. capillifolium, and C. canadensis var. canadensis are all wind-dispersed ruderal species that often colonize sites following nonselective chemical treatment.

Figure 3. Non-target (non–Imperata cylindrica) percent cover at 360 d after treatment (DAT) for each location. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Means for a given location not sharing any letter are significantly different by the Tukey’s adjustment for multiplicity at the 5% level of significance.

In summary, these studies indicate glufosinate applied alone provides short-term control to aboveground tissue of I. cylindrica but would not likely be effective for long-term control without multiple treatments. Glufosinate may also be a viable tank-mix partner with imazapyr for long-term control, as it did not inhibit the effectiveness of imazapyr in reducing rhizome biomass. Although previous research has suggested non-target broadleaf recovery may benefit from glufosinate treatments (Mohamad et al. Reference Mohamad, Awang and Jusoff2011), our results indicated limited differences in total non-target cover for glufosinate compared with most other herbicide treatments. However, this response seemed driven by site-specific factors. Vegetation management within natural areas is often most limited by logistical variables that impact the feasibility of treatment. Although labor is typically the most important component of project budgeting, material cost is another factor that is especially important for large-scale chemical treatment. Economic trends, supply availability, bulk pricing, and governmental bidding systems frequently impact herbicide prices, but recent pricing of glufosinate is comparable to that of glyphosate (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Reference Fish and Conservation Commission2023). This would facilitate the use of glufosinate as a tank-mix partner with imazapyr but would increase costs as a stand-alone treatment due to the expected necessity of additional re-treatment to achieve long-term control, as previously demonstrated for perennial weeds in ornamental contexts (Marble et al. Reference Marble, Neal and Senesac2020). Given the mechanism of action of glufosinate and expected rapid regrowth of I. cylindrica from its rhizomes, repeat applications of glufosinate—possibly even within the same growing season—are likely necessary to maximize immediate injury to aboveground tissue and adequately exhaust the energy reserves of the plant to potentially achieve an acceptable level of control as a stand-alone treatment. There also exist a number of other factors such as season, target plant physiology, growth stage, and environmental conditions that could more subtly influence glufosinate efficacy (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Bradley, Burns, DeWerff, Dobbels, Essman, Flessner, Gage, Hager, Jhala, Johnson, Johnson, Lancaster, Lingenfelter and Loux2025; Mersey et al. Reference Mersey, Hall, Anderson and Swanton1990; Singh and Tucker Reference Singh and Tucker1987; Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Wax, Simmons and Phillips1997; Takano et al. Reference Takano, Beffa, Preston, Westra and Dayan2019; Takano and Dayan Reference Takano and Dayan2021; Wendler et al. Reference Wendler, Barniske and Wild1990; Reference Wendler, Barniske and Wild1993). Future research should examine re-treatment intervals using glufosinate on I. cylindrica to clarify the optimal timing and quantify the repetition necessary to achieve adequate control for situations in which the use of glyphosate or imazapyr is not feasible.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the landowners of the field sites used for this project, including the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS), Florida State Parks, and the USDA Forest Service, for granting access and supporting long-term field research. We thank the following land managers for their collaboration and logistical assistance: Liz Krienert (Wildlife Biologist), Kathryn Smithson (Park Services Specialist), Tina Miller (Park Services Specialist), and Tracy Muzyczka (Environmental Specialist II). Special appreciation is given to field application technicians (Benjamin Tuttle, Jonathan Glueckert, and Chad Rose) for their careful implementation of treatments and to laboratory technicians (Minjin Choi and Max Chou) for their contributions to soil sample processing and analysis. Thanks as well to Karen Rogers at the Florida Department of Environment Protection for all her assistance with regard to permitting.

Funding statement

This work was most graciously funded by Armando Rosales with the U.S. Department of Defense and supported by the University of Florida Department of Agronomy and the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.