Introduction

In 2022, the key issue in Finnish politics was the war in Ukraine, as Russia, Finland's next-door neighbour, crossed the southern border. A consensus around support to the Ukrainian cause was joined with a demand for NATO membership, where, first, the population shred off their prior doubts and the parties followed. Government–opposition contestation increased towards the end of the year. Finland had their first regional elections, which demonstrated that the former regional power Centre Party/Keskusta (KESK) was not gone - the party finished among the top three. National Coalition/Kokoomus (KOK) won the regional election. The results emboldened KESK, which previously had falling support rates, to contest the Social Democratic Party/Sosialidemokraatit (SDP) and the rest of the Marin I government coalition, which they were a part of, in preparation for elections in spring 2023. The closeness of the general election marked the political year.

Election report

The first Finnish county elections were held in 2022 following an administrative reform that included establishing social and health districts on a regional level (Palonen Reference Palonen2022; Sipinen Reference Sipinen2022). Designing the policy of regional reform, the two main parties adopted a different emphasis: Representative democracy was stressed by the Marin government parties, who sought elected officials (SDP) and regional governance (KESK).

In the regional elections, representatives are elected for 20 wellbeing service counties. Helsinki, the capital city of Finland, was excluded, as the City of Helsinki continues to be responsible for associated wellbeing services. This meant that many of the front-line politicians and party leaders did not run in the elections. In the future, regional elections will be held simultaneously with municipal elections, so the mandate for the first county councils was for three years only.

Regional elections

The county elections were held on 23 January 2022. Advance voting was scheduled between 12 and 18 January and for citizens abroad between 12 and 15 January. The elections were also considered indicative for the forthcoming national elections in 2023. The elections were won by the National Coalition, with some distance to the second and third largest parties. The election focus on welfare worked to the advantage of the Social Democrats, who came second. The Centre Party's results testified that the party was still functional, retaining a place among the largest three contenders. The Finns Party's (Perussuomalaiset [PS]) support declined to a mere 11 per cent, whereas in the past, the party's growth had precisely pushed Centre aside. Also, the Green League/Vihreä liitto (VIHR) showed less support than in the national elections, falling behind the Left Alliance/Vasemmistoliitto (VAS). This time, the election issues did not excite voters, and overall turnout was lower than 50 per cent. In these first-ever county council elections, it was significant that some municipalities did not receive any representation at the county level.

Cabinet report

The Marin government, which had been polling consistently better than its immediate predecessors, hit an all-time low in December 2022. In June, 58 per cent of the public thought the government was doing a good or relatively good job, with 16 per cent saying its performance was poor. In December, the figures were 46 and 23 per cent, respectively (Paananen Reference Paananen2022). This transformation can be explained by party profiling prior to the parliamentary elections in 2023. Indeed, towards the end of 2022, the closeness of the parliamentary elections started to show in the intra-government dynamics, just as the opposition was starting to attack the Marin government by establishing a critical tone ahead of the elections. The popularity of the Centre Party in the polls had declined, and they doubled down on their criticism of the Social Democrats, which reinforced the oppositions’ message. Also, the Greens in particular sought a new boost for their image, being cast in the shadow of the other parties. On environmental issues, the debate was mainly between the Greens and the Centre Party.

According to the Government Yearbook 2022, the Marin government had succeeded in completing 82 per cent of the government policy statement, with 8 per cent planned on being completed in the first quarter of 2023 (Valtioneuvosto 2023). The long-awaited reforms included the transgender legislation and the Sámi Parliament Act (Mac Dougall Reference Mac Dougall2022). The Centre Party had been particularly active in delaying the Sámi legislation, as the areas affected by it had been its stronghold, and land use was a contested issue. Allowing more autonomy to the Sámi, an Indigenous people, could also involve a loss of power for the traditional local elites. This was a hot topic for a party that used to be one of the largest three parties but had now lost ground to the Finns Party also in Finnish Lapland, where the Sámi population is concentrated.

The Sanna Marin government experienced few ministerial changes in 2022, but the turbulent seat of the Minister of Science and Culture changed hands for the fourth time (Table 1). This time, the vice-president of the Centre Party (KESK), Petri Honkonen, replaced Antti Kurvinen (also KESK), who took over the position of Minister of Agriculture after Jari Leppä’s (KESK) resignation (Valtioneuvosto 2022). Leppä resigned after a decision to step down from politics after a long career as MP (HS 2022).

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Marin I in Finland in 2022

Source: Valtioneuvosto. Governments and Ministers since 1917. Finnish Government (2023) (Valtioneuvosto 2022) (https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/history/governments-and-ministers/report/-/r/m1/76).

Parliament report

In the Parliament, the Russian attack on Ukraine had important effects. Already before the attack, as things were getting more tense, the Finns Party's foreign allegiance was addressed. In a careless tweet by an advisor, MP Mika Niikko's (PS), pro-Russian sentiments were unveiled, and he had to step down as the chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Finnish Parliament, Eduskunta, on 16 February. He was replaced by Jussi Halla-aho, the former leader of PS, who has a PhD in Ukrainian linguistics from the University of Helsinki. This was a clear signal of where the Finns Party positioned itself in relation to the war that Russia started. The public was told that the sensitive security material usually discussed in the Foreign Affairs Committee had not been taken there during Niikko's chairmanship, implying distrust in the politician (Lahti & Palonen Reference Lahti, Palonen, Ivaldi and Zankina2023).

On 26 April, Petteri Orpo, the KOK chairman, was chosen as chair of the Defence Committee after the previous holder, Ilkka Kanerva (KOK), passed away. He was replaced in the Committee position by Antti Häkkänen (KOK) on 9 September (Ruokoski Reference Ruokoski2022). There was no drama involved, but changes could be seen as preparation for the 2023 election. In Finnish politics, KOK is known for its long-standing pro-NATO attitudes. In 2022, public attitudes towards NATO changed, and also all the parliamentary parties sided with NATO membership. Only the Left Alliance stood divided on this.

During 2022, the opposition brought up six votes of confidence (Eduskunta 2022). The only vote of confidence in the spring was prior to the Russian attack, on 8 February, when Riikka Purra (PS) challenged the government about energy and gas prices. In the autumn, the criticism towards the government and profiling for the spring 2023 parliamentary elections was visible in the issues brought about during the votes of confidence. Sari Sarkomaa (KOK) issued one about the state of elderly care services and the crisis in healthcare on 9 September. Purra (PS) also challenged the government on energy markets, the cost of electricity and the government's ownership policy on the energy company Fortum on 20 September. The environmental policy was contested by Sanni Grahn-Laasonen (KOK), claiming that the government had failed to lobby the EU about nature restoration regulation, on 27 October. The chair of the Christian Democrats/Suomen Kristillisdemokraatit(KD), Sari Essayah, issued one on the agricultural crisis and securing the future of domestic food production. And Purra (PS) raised the final one of the year, on combating juvenile and street crime through immigration and criminal policy measures. It is noteworthy that all the votes of confidence were issued by women on the all-female-led government, and all but Purra, the party leader for the Finns Party, were former ministers.

A total of 328 government proposals were passed as bills by Parliament in 2022 (Eduskunta 2023). The major bills included the new climate bill, which targets carbon neutrality by 2035 and passed in late May (Keski-Heikkilä 2022). The year also saw major nature conservation and biodiversity bills. On the social side, the government passed a gender-neutral family-leave reform to encourage more equal parental leaves and working life for both parents, as the statistics showed that in 2020, men would have only 10 per cent of the parental leaves (a smaller figure than in other Nordic countries), and women lagged behind in workforce and pensions (Hiilamo Reference Hiilamo2022). The Credit Information Act reform was aimed at speeding the removal of default notices after payment of debt, as they could take up to two years; the legislation took it down to one month. (Uusitalo Reference Uusitalo2022) Finally, the Integration Act set out to improve equality, integration and opportunities for immigrants. (Eduskunta 2023).

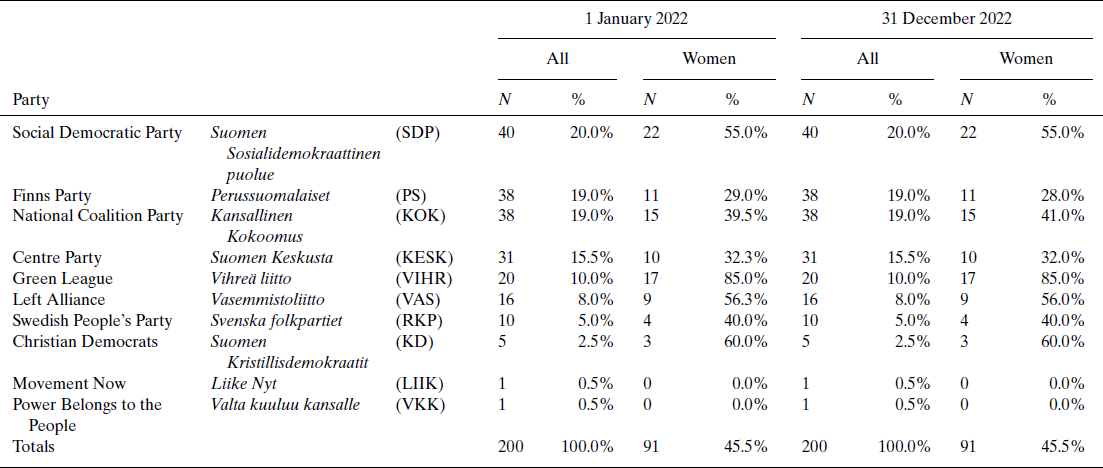

Information on the party and gender composition of the Parliament in 2022 can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Eduskunta) in Finland in 2022

Source: Eduskunta, Eduskunnan kokoonpano vaalikaudella 2019–2022 (2023) (www.eduskunta.fi/FI/naineduskuntatoimii/tilastot/kansanedustajat/kaikki-vaalikaudet/Sivut/eduskunnan-kokoonpano.aspx).

Political party report

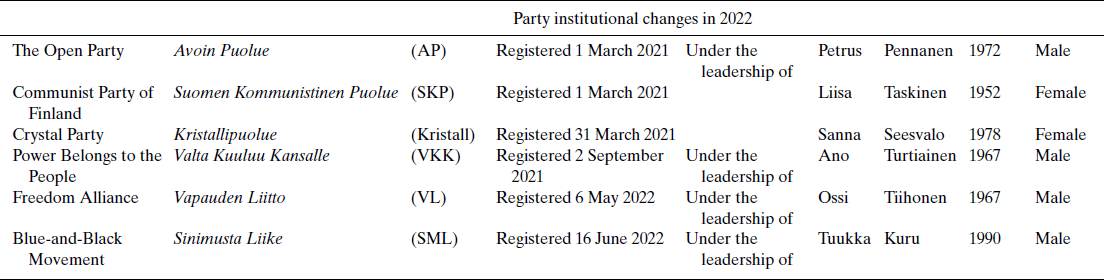

The party situation (Table 3) was stable, as in the beginning of 2022, there were regional elections, and parliamentary elections were scheduled for the spring. In light of this, the National Coalition Party conference voted to extend Petteri Orpo's term as the party's leader in June. Orpo had been the party leader of the National Coalition since 2016. Since there has been discussion of female prominence in Finnish politics, it is noteworthy that Orpo is the only male leader of a major parliamentary party. The only other male-led party in the Parliament is the Movement Now (Liike Nyt), a splinter from KOK. The position of the Centre Party's leader, Annika Saarikko, had been more vulnerable, but the party's good result in the regional elections motivated the Centre Party's biennial party conference in June 2022 to extend her term as the party leader.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Finland in 2022

Source: Vaalit, Rekisteröidyt puolueet (2023) (https://vaalit.fi/rekisteroidyt-puolueet).

Generally, we cover the parliamentary parties, but in this situation of war in Ukraine and the related ideological overtones, it is noteworthy that two new small parties, formed around people previously affiliated with PS, were registered in 2022: an anti-NATO, anti-EU, anti-migration Vapauden liitto (Freedom Alliance) and the proto-fascist Sinimusta liike (Blue-Black Movement). The latter took a year to collect enough signatures, the former using online groups to register support faster (on small parties, see Fagerholm Reference Fagerholm2022; on the comparison between the Blue-Black Movement and the Finns Party, see Salojärvi et al. Reference Salojärvi, Palonen, Horsmanheimo and Kylli2023). These parties also planned to run in the parliamentary elections in 2023—and eventually did so.

Institutional change report

On 22 February, Russia, Finland's neighbouring country, started a war in Ukraine. This put Finland in a radically new institutional situation in national security politics and initiated the process of accession to NATO. Additionally, the Finnish government coordinated with the EU to restrict and sanction individuals connected to the Russian aggression, freezing their funds and preventing travel. Material assistance was channelled to Ukraine in coordination with the EU, and Finland also carried out a policy of acceptance of Ukrainian refugees.

Initially, Finnish politicians were reluctant towards a quick application to NATO membership, but surveys indicated a swift mood change among the population, with a majority of all political parties’ supporters siding with membership. Already in early March, the polls indicated that 62 per cent of the population, who in the past had been reluctant to join NATO, were in support of membership. In this regard, even President Niinistö admitted retrospectively to have considered whether membership would be seen as a provocation by Russia (Teittinen Reference Teittinen2023). But the SDP leadership were quick to change their views. The traditionally Trans-Atlanticist KOK was strong in the polls.

Issues in national politics

The war in Ukraine and NATO membership were the prominent issues in Finland (see also Institutional Change Report). Strong solidarity was expressed to the Ukrainians from the start of the Russian attack. Finland applied for NATO membership, which gave the country a lot of attention. The Finnish armed forces, the 1300-km border with Russia, and the memory of the Winter War in 1939–1940, when the USSR attacked Finland, were not only featured worldwide but also featured in national politics. The Finnish government started to build a fence against the Russian border. The figureheads of this (both internationally and nationally) were President Sauli Niinistö (before his presidency: KOK) and the PM Sanna Marin, as well as Minister of Foreign Affairs Pekka Haavisto (VIHR), who supported Ukraine and contested Finnish and European previous trust in Russian trade links. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs listed their press mentions abroad as 140,000 for Niinistö, 146,000 for Marin and 53,800 for Haavisto (Ulkoministeriö 2023)—a significant increase from the previous year.

In August, something else broke the scene both in Finland and, later, abroad: Video recordings of Sanna Marin partying privately with her friends were disseminated publicly and resulted in discussions and controversy in the news media. The attitudes abroad were generally positive, but the statements in Finland condemned her behaviour. She had become a divisive figure, with earlier scandals (see Palonen Reference Palonen2022) being replicated here. The video featured misunderstandings and unfounded accusations of drug use, and political opponents called for a drug test, which was taken and came back negative (YLE 2022a; YLE 2022b). Further evidence of partying came out, including bringing friends to the summer residence of the president after a summer festival in July. The issue was about a generational shift, both in terms of social media use and also, more generally, about whether or not prime ministers should be partying (Lemola Reference Lemola2022). Marin's behaviour was also contested as inappropriate in a context where the costs of electricity and interest rates were rising (SVT 2022).

Dissatisfaction with the cost of living rose among unions. In the healthcare sector, a nurse strike began in April 2022 and lasted until the start of October (Uusitalo et al. Reference Uusitalo, Komulainen and Rautanen2022). The year 2022 saw a total of 64 strikes or industrial disputes affecting almost 180,000 people (SVT 2023). One of the longest strikes took place at the global UPM paper mill, where the union members returned to work in April 2022 after 112 days of strike, argued to have global effects on collective action (IndustriALL 2022). Besides rising costs, the payment gap between sectors (like the predominantly female health-care sector) was discussed.

The government's specialised unit for coordinating and monitoring COVID-19, centralised under the social and health ministry, was discontinued on 21 December. The COVID-19 pandemic was sidetracked when the war in Ukraine started. Partly, this was also due to the most active proponent of COVID-19 measures, Minister Krista Kiuru (SDP), starting her parental leave. The Omicron wave brought about large numbers of infections and COVID-19-affected deaths during the pandemic in Finland. However, national policies regarding borders, indoor activities and events were discontinued in early 2022, and the focus shifted to local management. Recommendations for remote work were also discontinued in early 2022. The wellbeing of the youth started to feature as a post-pandemic issue (Valtioneuvosto 2023).

Public spending and debt emerged already from the autumn as one of the key campaign issues, where the opposition presented the government as irresponsible towards the next generations, especially as a result of public spending increasing significantly during the pandemic.

The government provided support for households in the form of tax breaks, benefits and rebates for large electricity bills and was also committed to supporting both Ukrainian refugees and EU-coordinated activities in support of Ukraine. The energy crisis also had other effects on the Finnish government, which had to address an international trade issue when the state energy firm Fortum, the main shareholder of German gas company Uniper, rejected further contributions to Uniper, which had been facing heavy losses due to the Russian energy war. In an unusual situation, Minister Tytti Tuppurainen (SDP) sought to safeguard the Finnish interests while facing criticism from the opposition and the Germans. The first agreement was reached in July, and a sale deal with the German government took place in September (YLE News 2022c).