Introduction

Freedom of media and media pluralism are key criteria for evaluating the degree of democracy in a society as democracy is not possible without a free media to serve as a watchdog and foster accountability of those in power. Stojaravá (Reference Stojaravá2020) also compares the media as being a fourth estate providing checks and balances to the other three branches of government (162). Entrenched in the EU Charter for Fundamental Rights and the 1993 Copenhagen political criteria accession countries must meet prior to membership of the EU, freedom of expression has also become an integral part of the Europeanization and democratization processes, particularly relevant to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEECs) that joined the European Union in 2004 and 2007 and the more recent Western Balkan candidates. Although the CEECs have been successful in their transition to democracies, including in rule of law reforms, many scholars and journalists argue that the media in the Western Balkans have been deteriorating with the presence of informal networks between politicians and the media, financial dependence of the media on the ruling parties as well as an increase in attacks on journalists being among the most pressing concerns (ANEM 2015, Bieber and Kmezić Reference Bieber and Kmezić2015, Kmezić Reference Kmezić2018, Blazeva et al Reference Blazeva, Borovska, Lechevska and Shishovski2015, Jusić and Irion Reference Jusić and Irion2018, Kleut Reference Kleut, Dobek-Ostrowska and Głowacki2023, Stojaravá Reference Stojaravá2020, etc). In the Western Balkans, control over the media is mostly indirect and subtle in order to preserve the image of democracy.

According to the Reporters Without Borders Media Freedom Index for 2024, Serbia represents the worst drop in freedom of expression among EU and Balkan countries, falling 12 places to 98 out of 180 countries (Reporters Without Borders 2024). Serbia’s government under Aleksandar Vučić, who had been Information Minister under Milošević, has consolidated power through state capture of independent institutions such as the media, the judiciary and elections. The capturing of state institutions was a consequence of a lack of political stability caused by blocked post-socialist transformation during the 1990s. This was a pattern of a wider trend in Southeast Europe, especially among the Balkan countries where, “instead of paving the way for democracy like in most countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the introduction of competitive elections in the early 1990s led to the establishment of competitive authoritarian regimes that exploited structural weaknesses, and governance practices left over from the period of state socialism” (Kapidžić Reference Kapidžić, Kapidžić and Stojaravá2022, 6). Weak institutions and informal networks such as those in Serbia, combined with a lack of political will for reforms, presented political elites with fertile ground to ingrain and exercise their patronage network, which was especially visible in the media sphere. Voltmer (2012) argues that persisting structures, old norms, role models and power relations continued in the media even following the years of democratic transition (cited in Milojević and Krstić Reference Milojević and Krstić2018, 39). This informal clientelist network did not lead to the democratization of the media but rather undermined media freedom as a whole, allowing the government to continue to indirectly influence the media through various subtle mechanisms of control.

The focus of this article is on the Serbian Progressive Party (hereafter, SNS) led by President Aleksandar Vučić which gained power during the presidential and parliamentary elections in Serbia in 2012; and continues to remain in a position of power as the only leading political party even a decade onwards. While Vučić has an arsenal of authoritarian measures to implement control, media was chosen as the country’s EU accession process has gained particular saliency with regard to rule of law conditionality, thus making media freedom in Serbia particularly relevant to study. Moreover, the clientelist networks vis-à-vis the media, prevalent in all of the Western Balkan countries, are particularly underdeveloped in the literature on media studies and democratization. Although all of the former Yugoslav states and even some EU Member States are experiencing decline in freedom of expression, this trend is the most significant in Serbia with some journalists describing the media scene as being worse than in the 1990s because the mechanisms of control are subtler and less visible. That is to say, media control and pressure is exercised indirectly through the distribution of subsidies to “loyal” media as well as through the issuing of broadcasting licenses to regime media through an equally captured broadcaster. The adoption of the new media laws in August 2014 (the law on public information and the media, the law on electronic media, and the law on public service broadcasters) and again in October 2023 (the adoption of a new law on public information and the media and amendments to the law on electronic media) was expected to contribute to independence of the media through the phasing of the state out of the media. Instead, as Matić and Valić-Nedeljković (Reference Matić and Nedeljković2014) would argue, the media have become prisoners of the financial sources that are outside the media market, namely business and political groups who have their own interests (cited in Milinkov and Gruhonjić Reference Milinkov and Gruhonjić2021, 73). This paper will seek to analyze the presence of clientelist connections between the state and the media and how the political instrumentalization of the media has in turn shaped the media environment in Serbia in a way that has led to its deterioration. First, the theoretical framework that focuses on the concept of political clientelism and its linkage to the media is presented with an analysis of the scholarship within this field in relation to the Western Balkans. Then follows an analysis of the state capture of the regulatory authority for electronic media that has consistently granted licenses to the four national television channels with a high audience share. The concept of project co-financing, which entered into the law on public information and the media adopted in 2014, was supposed to ensure media received funding in a transparent way as a form of legal state aid, for projects whose content met the public interest, but itself became a corrupt instrument in the hands of the government. In addition, political advertising also became a tool to influence loyal media which was elucidated during the election campaigns. Finally, the newly adopted law on public information and the media in October 2023 that legalized the status of the state-owned Telekom telecommunications provider as direct owner of the media will be examined. The article concludes with a brief discussion on the EU’s failure to promote democratic reforms that would lead to freedom of expression as a consequence of its prioritizing stability and security concerns over democratic values.

Theorizing the Politicization of the Serbian Media through Clientelism

In the Western Balkans, particularly in Serbia, the media have not succeeded in becoming autonomous to exercise a will of their own to serve the public interest but have rather persisted in interconnected, complex patrimonial networks serving government and business elites’ interests. Scholars have closely examined the power dynamics between media and outside actors, including political, economic, financial, advertising and other elite or relevant social groups. This control of the media by the state is associated with the concept of political clientelism which is among the most challenging problems facing the Western Balkans today.

According to Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos (Reference Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos2002), the concept of clientelism has not been very developed in media studies even though it is part of a wider trend among Eastern and Southeastern Europe, but also in other parts of the world such as Latin America, the Middle East, and much of Asia and Africa (184). Contrary to this argument, however, there is a growing body of scholarship that suggests that media have an important place in clientelist systems of political organization (Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos Reference Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos2002; Hallin and Mancini Reference Hallin and Mancini2004; Roudakova Reference Roudakova2008; Örnebring Reference Örnebring2012). Political clientelism refers to “a pattern of social organization or network in which access to social resources is controlled by patrons and delivered to clients in exchange for deference and various kinds of support” (Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos Reference Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos2002, 184-185). Media-political clientelism, on the other hand, as Selvik and Høigilt (Reference Selvik and Høigilt2021) argue, “manifests itself in the instrumentalization of media outlets” by politicians (654). This is a process where politicians use the media under their control to advance their particularistic interests. Thus, “clientelism is linked to informal networks engaged in exchanges of favors and resources, often nontransparent, where the main goal of the network is to increase/retain the power and resources of its leading actor(s)” (Örnebring Reference Örnebring2012, 503). Örnebring (Reference Örnebring2012) posits that a broader understanding of clientelism within the media would be looking at how the media are used as an elite-to-elite and elite-to-mass communication tool which was used to describe the place of media in the clientelist systems of the CEECs but can serve as a point of departure for the Western Balkans as well – in other words, looking at how political elites communicate with and influence media owners and editors-in chief to retain a position of power. This can be done through political advertising where the most amount of money is awarded to loyal media who then promulgate party policy and create a positive image of the party leader(s) as well as through other mechanisms the paper will discuss such as through a captured regulatory authority. Clientelism is thus an asymmetric, hierarchical form of social organization where power is primarily concentrated at the top with the patron or the ruling party and its leader whose primary goal is the acquisition, maintenance and aggrandizement of power and wealth as well as the protection of their interests.

The scope of clientelist relationships and the mode in which they would be established strongly depended on the historical legacy of a given society, and thus it is strongest in Southeastern Europe due to the late development of democracy that was exacerbated by blocked post-socialist transformation and state capture of weak institutions (Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos Reference Hallin and Pappathanassopoulos2002, Cvejić Reference Cvejić2016). This was most evident in the former Yugoslav successor states where the collapse of the Milošević regime left fragile institutions coupled with political instability and unrestrained access to public funds and rents that the Milošević-era political elites inherited when they rose to power. Thus, clientelist relations and patronage networks are a defining characteristic of the Western Balkan societies that facilitate inequalities and uneven distribution of resources and opportunities, as well as undermining democratic principles that started emerging in the new states.

Although control of the media by Serbian elites is well researched in scholarly articles, clientelism as a concept to describe the political relationship with the government is limited in the literature on media freedom in the Western Balkans with the little existing scholarship either in the Serbian language or outdated and not taking new developments into account – for example, the Serbian government control of the media through the telecommunications provider as adopted in the 2023 Law on Public Information and the Media. Milojević and Krstić (Reference Milojević and Krstić2018) from the University of Belgrade who have written several articles in the field of media studies have published an article that utilizes the hierarchy-of-influences model as a framework for examining the ways in which media owners, managers and journalists perceive the influence exerted on their work during the twelve-year democratic transition in Serbia. Although they link the concepts of clientelism and corruption to explain how and why media become instrumentalized during transition periods, there are no concrete examples and in-depth analyses of advertising nor is the concept of project co-financing mentioned where our article has identified major clientelist practices (Milojević and Krstić Reference Milojević and Krstić2018). In a recent article by Milojević and Kleut (Reference Milojević and Kleut2023), however, state capture in relation to state ownership and financing of the media is utilized to analyze the concepts of project co-financing and advertising in order to elucidate the government control of the media outlets in Serbia. However, this article does not analyze the new media laws adopted by the Serbian Parliament in October 2023. The few articles that do exist where the term clientelism was specifically used to describe the informal networks vis-à-vis the Serbian government and the media, are mainly in the Serbian language (Jevtović and Bajić Reference Jevtović and Bajić2019, Prokopović and Vulić Reference Mihajlov-Prokopović and Vulić2015, Milinkov and Gruhonjić Reference Milinkov and Gruhonjić2021). Kmezić (Reference Kmezić2018), who has written extensively on the rule of law and democratic backsliding in Serbia and the Western Balkan states, provides an analysis of different types of informal and direct pressure by politicians against media owners, journalists and editors in chief in addition to clientelist connections between ruling elites and business tycoons who bought off media during privatization in 2015. However, this article appears outdated, and offers only brief analyses of the media scene up until 2018. Much of the research on government influence of the media focuses on state capture which, we argue, is not the same as political clientelism. Varraich (Reference Varraich2014) claims that clientelism, patronage, particularism and patrimonialism focus on the output side of corruption, such as how power is exercised, while state capture focuses directly on the input side where corruption is affecting the basic rules of the game (i.e., laws, rules, decrees and regulations policies, laws at the stage where they are formed) (25-26). Moreover, state capture is a broader concept that describes overall political processes in semi-authoritarian or hybrid regimes while clientelism is more associated with strategies of state capture or “how access to power is gained and secured” (Trantidis and Tsagkroni Reference Trantidis and Tsagkroni2017, 265). Thus, our research aims to address this gap in the literature by examining the scope and extent of clientelist relations between the Serbian government and the media through an in-depth analysis on the captured regulatory authority for electronic media (REM), examples of patronage networks in project co-financing, the political advertising of the ruling party and Vučić during the pre-election campaigns as well as through the recent, controversial legalization of the state-owned telecommunications provider, Telekom Serbia. Before we do so, we turn to a brief analysis of the methodology used for this study followed by a short background on the Serbia mediascape under the ruling Serbian Progressive Party and Vučić.

Methodology

To elucidate the results, a range of primary and secondary sources were used, namely reports and news stories by media organizations and journalists’ associations (i.e., Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia, the Journalists’ Association of Serbia, the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, and the Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability). As supplemental material, the author conducted six semi-structured interviews with journalists and media experts in Novi Sad and Belgrade, Serbia from January 21-28, 2024, in addition to three email interviews and one follow up phone interview on September 23, 2024. The journalists were identified through the two main journalists’ associations: Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia and the Journalists’ Association of Serbia as well as two media experts from the University of Novi Sad and University of Belgrade. Due to verbal death threats some of the journalists and media experts had received, anonymity was retained in the research.

Background of the Serbian Media Space under Vučić

Defined by a highly competitive political system together with a poor level of economic development enhanced by the economic recession made it all the more pertinent for the Serbian Progressive Party (led by Aleksandar Vučić) to win power so as to control the allocation of public resources in an unconstrained manner through state capture of weak, formal institutions. Thus, once elected, the SNS took to investing in engineering their own system, which largely implied state capture of major institutions and media outlets with the aim of promoting pro-government bias. Adopting a pro-EU reform agenda for financial incentives and electoral support both domestically and abroad, the SNS only declaratively adopted laws that would lead to democratic reforms including freedom of the media while establishing clientelist relationships with the media in order to promote their own agendas and interests. Thus, the Progressive Party under Vučić aimed to bring all the media under their own control by developing a special media-politics type relationship which essentially meant commanding and centralizing the news about the leader’s figure but also financially favoring certain media that would print affirmative news and propagate the party’s policies (Bequiri Reference Bequiri2021, 227). As Car (Reference Milinkov and Gruhonjić2021) argues, this form of “media capture” causes the media to become “hostages” who are unable to fulfil their primary mission as the “watchdog” of democracy (cited in Milinkov and Gruhonjić Reference Milinkov and Gruhonjić2021, 76).

Bieber (Reference Bieber2018) argues that the channel of government influence on the media is less direct and more subtle today under the Progressive Party than it was under the Milošević regime in the 1990s when the media were still under state control and/or ownership (347). In contrast to the 1990s, “today, we can note that competitive authoritarian regimes rely on a combination of loyal media owned by businesses with murky and convoluted ownership structures, economic pressure on independent media and threats and censorship of journalists and media” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018, 347). In Serbia under Vučić, the media serve two purposes: first to de-legitimize any critical, independent media and second, to construct and promote a well-established, omnipotent image of the Serbian president and ruling party in exchange for economic support. The tabloid media in Serbia especially contributed to the emergence of a personality cult around Aleksandar Vučić, portraying him as a constant victim of enemies […] while also displaying superhuman traits in overcoming these challenges (Bieber Reference Bieber2020, 128). In line with Ryabinska (Reference Ryabinska2011), this elucidates that “the media are not autonomous from governments or vested interests, but highly dependent on them, and they function not as democratic institutions, but as tools for trading influence and manipulating public opinion in the interests of power-holders”(4). The asymmetric, “reciprocal exchange” relationship, which is an essential feature of clientelism, is therefore reflected in the government’s politicization of media through subsidies while the media in exchange serve as propaganda tools for promoting pro-government bias, which has negative consequences for media freedom and pluralism. We argue that the indirect economic and political control over the media outlets, mainly through the financing of “loyal,” private media in Serbia is partly a consequence of the oversaturation and economic instability of the media. In the Reporters Without Borders Index, there are over 2,500 media outlets registered currently in Serbia, in addition to media that are not registered in the media register but continue to function (Reporters Without Borders 2023, Interview with Journalist A).

To phase the media out of the state, the Serbian Parliament, dominated and controlled by members of the Progressive Party, adopted a package of three media laws in 2014: the law on public information and the media, the law on electronic media and the law on public service broadcasters, in order to democratize the media environment. A key feature of this law was the privatization of the media by the deadline of October 2015. The privatization did not lead to the total phasing out of the state from the media outlets; rather, business tycoons with close connections to the Serbian government, or even members of political parties themselves, bought a majority of the media outlets for exorbitant amounts of money. This also precipitated these same media to receive large amounts of money through various subsidies vis-à-vis the government in addition to tax exemptions and other governmental “favors.”

The law on public information and the media also introduced the concept of project co-financing for media projects whose content met the public interest. This was also supposed to contribute to the withdrawal of the state from the media, but instead, this became a tool to award large sums of money to pro-government media. Furthermore, advertising, which is not embedded in any Serbian legislation, continued to entrench the Serbian media to publish only positive images of the ruling party and President Aleksandar Vučić: thus, critical reporting and investigative journalism were all but extinguished, aside from a few dailies whose circulation did not reach a wider audience. In addition to promulgating SNS policies, the media served to act as attack dogs for the Serbian government often criticizing and demonizing the opposition while delegitimizing the critical voice of other media and journalists. Vračić and Bino (2017) posit that “labeling journalists as foreign agents, enemies of the state or blaming the media and journalists for ‘throwing government pollution’ are just a few examples of attempts by political actors to denigrate the media” (61).

The adoption of a new law on public information and the media and amendments to the law on electronic media in October 2023 stemming from the recently established new Media Strategy (2020-2025) furthermore cemented government interference and control of the media outlets due to the legalization of the Serbian state-owned telecommunications provider Telekom, which is allowed to own and establish media outlets. Thus, the implementation of reforms was merely declarative or partial as the government maintained the old mechanisms of influence on the media. In the following sections, we present the extent and scope of the political instrumentalization of the media in the areas of the captured regulatory authority, project co-financing, advertising, as well as the legalization of Telekom.

Capture of the Media Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media

The Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media (REM) was initially established by the Broadcasting Law in 2002 (then known as the Regulatory Broadcasting Authority) with its main tasks being to allocate broadcasting licenses, monitoring electronic media in terms of adherence to the law and to appoint governing boards of the public service broadcasters (RTV and RTS). As of 2014, only its name has been replaced with little change to the actual functioning of the authority. The REM can be described as a captured regulatory authority with its current President, Olivera Zekić, criticized for turning the REM “into a local board of SNS.” Since her membership to the REM Council in 2015 followed by her election as President, REM has adopted a passive attitude regarding pro-government media and their infringement of existing laws (Massimo et. al Reference Massimo, Epis, Law, Djurić and Stevanović2024, 7).

The non-compliance with the law was further underlined in the case of granting four licenses for national frequency to the same pro-government channels linked to the ruling Serbian Progressive Party in 2022 (Babić Reference Babić2024, 34; Massimo et. al Reference Massimo, Epis, Law, Djurić and Stevanović2024, 10). Several calls for a fifth license have been made sine 2012 when TV Avala had ceased to exist, but this license has yet to be rewarded. A journalist speculated that the reasoning being was that “they had to grant a fifth license to either Nova or N1 (both independent channels) which they will not do” (Interview with Journalist E 2024). Furthermore, TV Nova S is running a court case against REM and the regulator has decided it cannot proceed with a decision on the license until the court process has finished (Kleut Reference Kleut, Dobek-Ostrowska and Głowacki2023, 268).

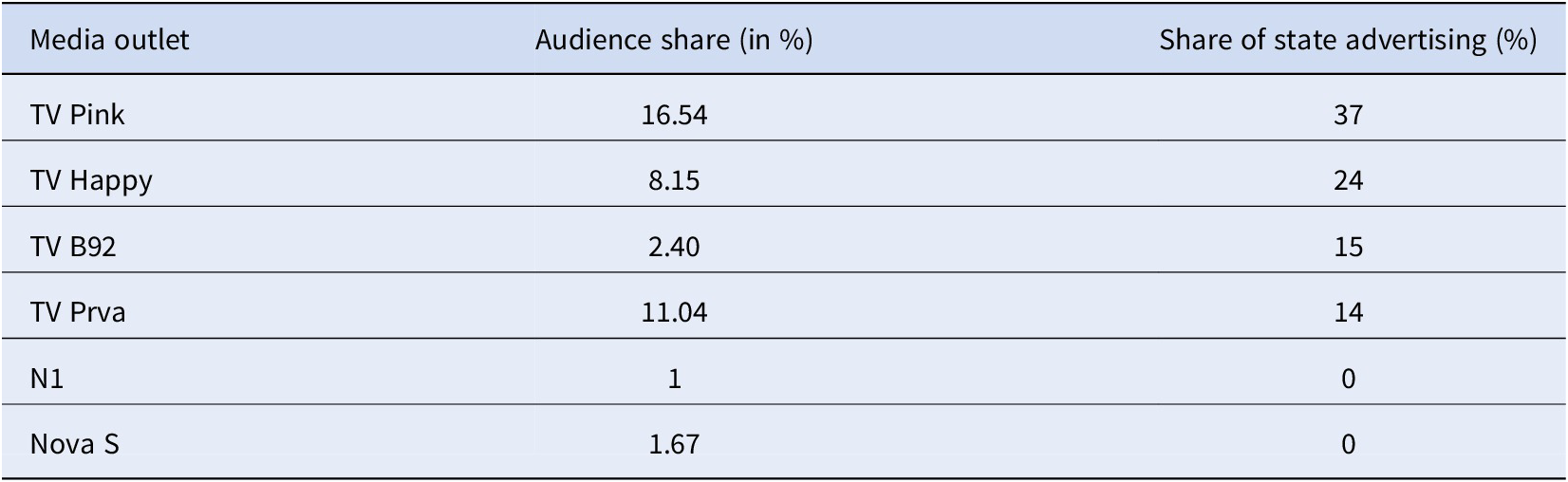

The minimum requirements for the provision of media services are defined by the ordinance that they must have informative, scientific, educational, cultural and artistic, documentary and children’s programs. TV Pink and TV Happy were leaders in commercial entertainment programs such as reality shows with a “complete absence of children’s, scientific-educational, cultural, artistic and documentary programs” (Petrović-Škero and Jovanović Reference Petrović-Škero and Jovanović2021, 13-14). Petrović-Škero and Jovanović (Reference Petrović-Škero and Jovanović2021) posit that “since 2013, the share of reality shows in program schemes has been growing, culminating in 2015, when the share of that program in the TV Happy scheme was as much as 58.42%. The complete collapse of the quality of programs on the stage occurred in 2018 and 2019, when the share of informative and reality content on Pink and Happy televisions was 65.97% and 74.86%, respectively” (14). This statement is also corroborated in a report by Crta (Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability) which posits that “the program content of both Happy and Pink consists from around 40% (38,80% exactly) of reality shows and 30% informative programs. When you take a look at that informative program, it’s clear that’s also a reality show” (Srećković et. al Reference Srećković, Jaraković, Srefanović, Branković, Avakumović and Manojlović2022, 41). Pink is owned by Željko Mitrović and has been described as a media working with the government of Serbia. Like TV Happy, TV Pink is largely financed from state advertising. TV Happy’s ownership structure is murky with rumors that the television channel is in the hands of Predrag Ranković who had previously provided financial support to the former Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić (Massimo et. al 2024, 10-11). TV Happy is also financed primarily from state advertising. TV Prva and TV B92 are tied to the ruling party through ownership structures. Table 1 elucidates the importance of these four national television channels and the two independent channels, and the share in state advertising for each of them.

Table 1. Audience and state advertising share in television market in Serbia, 2020

Source: Media Ownership Monitor, Srećković et. al 2022.

The control over private television networks with national coverage is established via the recurring allocation of broadcasting licenses by a regulatory body that is under firm government control as elucidated by various journalists’ and media experts’ reports. The main source of income for these national media is state advertising which is granted through the broadcasting licenses. Another example of political control and clientelism within TV Pink and TV Happy is the granting of discounts to the ruling party for advertising during elections – these discounts can be as high as 90 per cent (Srećković et. al Reference Srećković, Jaraković, Srefanović, Branković, Avakumović and Manojlović2022, 64). In return, the government would offer media protection through tax deductions, loans and other favors to “loyal” media, thus creating an informal, clientelist network where the control is in the hands of the ruling party. A journalist from Novi Sad elucidates the state capture of REM:

“REM is a serious political organization. I mean, it is not supposed to be. It is a regulatory body…However, it is very newsworthy in its manipulative role when it comes to the regulation of electronic media. For example, take the elections for the new Council of REM that were supposed to be held. They are putting it off indefinitely. REM want to keep the media under government control, so that it can ensure that those pro-government media can publish whatever they want, and to warn the latter [independent, critical media] for the smallest of trifles. Because the media should maintain that imbalance in the status quo.” (Interview with Journalist C 2024).

The state capture by the ruling Progressive Party of the four television channels with national coverage as well as the regulatory authority was a political manipulation tool to subvert democracy by manipulating public opinion so as to retain a position of power. TV Pink, Happy, B92, and Prva are among the most watched television channels in Serbia with a large portion of audience share while the two independent channels with critical views available on cable network are highly restricted as only a small percentage of the population has access to them. B92 additionally used to be one of the few independent and professional media during the Milošević regime that has since lost its credibility due to a change in ownership by a business tycoon closely linked with the ruling party. Moreover, as well as promoting government propaganda and promulgating SNS policy, these television channels do not host adequate children’s, education and scientific programs but rather what can only be described as sensational television in the form of reality shows, sometimes the glorification and rehabilitation of war criminals as featured on TV Happy, and other “violent, crude, primitive, and dangerous content” (N1 2024). There were multiple attempts and requests made by the media experts to shut down these media, cancel the television shows and reality programs that promote violence, and confiscate their national frequencies that went largely ignored, mainly because it is not in the interest of the government to relinquish their control and capture of the Serbian media space. It was not solely the online and television media that was criticized for their pervasiveness of clientelist connections and subversion of democracy, but also the print media, namely the tabloids, which had received huge amounts of money during the competitions for project co-financing which itself was a corrupt instrument suffering from numerous irregularities.

Clientelist Networks in Project Co-financing

Control over the media is enacted at high elite-to-elite level where the media owners are linked personally to political or business elites or are members of the political party themselves. This was observed in the concept of project co-financing where the Serbian government proceeded to award large sums of money to loyal, pro-regime media and those media whose ownership was in the hands of business tycoons who were in some way connected to the government or were (former) members of the Serbian Progressive Party themselves. This phenomenon of media moguls or oligarchs who typically personify the clientelist linkages between the media and politics was also identified in countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Örnebring Reference Örnebring2012, 505).

Gruhonjić, Šinković and Kleut (Reference Gruhonjic, Šinkovic, Kleut, Milojevic and Veljanovs-ki2018) identify three phases of political manipulation in project co-financing. In the first phase of implementation of project co-financing (2014-2015), it was misunderstood as an instrument for supporting and promoting media pluralism and used by local self-governments to financially support local media. However, in the second phase (2015-2018), it became a channel to award grants and subsidies to party-loyal media, in support of the Progressive Party-led government (cited in Milojević and Kleut Reference Kleut, Dobek-Ostrowska and Głowacki2023, 69). For example, Alo received over 300,000 euros, Srpski Telegraf over 220,000 euros, while Informer received over 135,000 euros since 2015 (Milojević and Kleut Reference Kleut, Dobek-Ostrowska and Głowacki2023, 69.) Just last year in 2023 during the competitions for project co-financing, Alo received 126,000 euros, Večernje Novosti received 117,000 euros, and other pro-government media, such as Adria Media System that owns the tabloid Kurir, received 83,000 euros in the competitions for project co-financing (Raskrikavanje 2023). The aforementioned tabloid media have also violated the Journalists’ Code a total of 2,579 times in the year 2023 (Kragulj Reference Kragulj2024). (Večernje Novosti had 430 violations; Alo 1,065 violations; Informer 791 violations; Srpski Telegraf 980 violations; and Kurir had 448 violations – Kragulj Reference Kragulj2024). In the third phase (2018-2020), Milojević and Kleut (Reference Milojević and Kleut2023) argue, project co-financing led to the creation of quasi political and economic media structures (69). Such structures are known as “gongo” media (or, government-organized non-governmental organizations). These are citizens’ associations that the government itself establishes, supports and finances in order to implement its political interests, creating the appearance of civil sector action. During the competitions for project co-financing, commissions were established with members from these “gongo” organizations in order to allocate money to government loyal media, as was the case with the commissions linked to Vladan Stefanović – a media mogul with connection to the ruling SNS – in Subotica and other cities in the Serbian province of Vojvodina (Subotičke 2022.) In a study by the Balkan Investigative Network (henceforth, BIRN), 27 so-called “gongo” organizations had been identified that had received 1,158,610 euros with an additional 138 phantom organizations that had received 5,842,544 euros in 2022 and 2023 (Gimzić Reference Gimzić2022). These phantom organizations usually have no real address or contact information, and are very often linked with the government (Interview with Serbian Journalist B 2024).

Since the end of the privatization process in 2015, business tycoons closely associated with the ruling party were often the recipients of significant financial rewards during the competitions for project co-financing. Such media moguls are affiliated with the Progressive Party (Radoica Milosavljević, Vladan Stefanović, Vidosav Radomirović) or are even actual members of the SNS (Zvezdan and Srđan Milovanović, and Nikola Gašić). Serbian Socialist Party member, Radoica Milosavljević, had purchased eight media outlets during the process of privatization. He additionally purchased another six media outlets including RTV Kragujevac which is due to be privatized yet again (Aleksić Reference Aleksić2021). From 2015-2020, his media outlets received a total of 3,097,445 euros solely through the competitions for project co-financing. The clientelist relationship between Milosavljević and the Progressive Party was further elucidated when the city of Kruševac awarded 17,500 euros to the city television through project co-financing of the media just a few hours before it was to be bought by Milosavljević. Milosavljević paid 14,000 euros to TV Kruševac. (Radio Free Europe 2024). Pavlović (Reference Pavlović2020) posits that the privatization process “appeared to have dealt a deadly blow to the independence of local media but also led to the deterioration of the media content’s quality. Instead of getting a preferred outcome under which the market would allocate resources so as to enhance media freedom in the Serbian municipalities, local TV and radio stations were sold off to tycoons affiliated with the SNS, with rigged sales administrated by the Privatization Agency, which itself was a corrupt institution, infected by massive party patronage” (28). The business elites who purchased the media during the process of privatization instrumentalized them into a SNS propaganda machine (Gotev and Poznatov Reference Gotev and Poznatov2016). The patron-client relationship between Milosavljević and the SNS was elucidated when it became known to the public that Milosavljević was the Minister of Internal Affairs, Bratislav Gašić’s, silent business partner. Gašić’s entire family owns media outlets and companies in Serbia, including his two sons Nikola and Vladan, who own TV Zona Plus and the online portal, Plus.

The private media outlets financed in this way who are under the control of SNS-affiliated owners and sometimes even party officials themselves, use these media to propagate SNS public policy as well as demonizing the opposition. Pavlović (Reference Pavlović2020) argues that this “extractive mechanism has a direct impact on the electoral process and media freedom, thus creating an unfair political arena whilst undermining democratic institutions” (34). Affirmative articles promoting the Serbian President and the SNS whilst utilizing hate speech to discredit the opposition appeared the most in the tabloid media which dominate the Serbian media environment. A journalist interviewed for the purpose of the research claims that the tabloids who are financed by the government through project co-financing are the media “who have more fake news on their front pages than there are days in a year…” (Interview with Journalist B 2024). They further posit that such tabloids receive projects at the republic level and projects from cities and huge money is poured into that type of media through various forms…they are supported in every other way” (Interview with Journalist B 2024). Therefore, the extent and scope of political clientelism in the competitions for project co-financing was extensive; significant amounts of money were awarded to media with close connection to the ruling party who would then publish affirmative news stories propagating SNS policies in order to maximize the party’s grip on power. These same media were the ones where Aleksandar Vučić held a dominant presence, especially evident in the campaigns leading up to the elections.

Indirect Control through Advertising during Election Periods

Elections were another political manipulation tool used by the ruling party and Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić. Spasojević (Reference Spasojević2021) claims that “clientelism, the exchange of votes or turnout for funds or services, had become an inevitable part of any campaign, and was getting less and less hidden” (73). The final report from Crta (2024b) (Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability) on the parliamentary elections in December 2023 also corroborates this, stating that: “observers recorded cases of pressure on voters, misuse of public resources and personal data, political pressures and electoral clientelism, especially aimed at employees in the public sector, distrust of citizens in institutions and a frequent atmosphere of fear” (23). The media, on the other hand, are very powerful in shaping public opinion and are important tools in elite-to-mass communication. Thus, they became an instrument for electoral manipulation, where the playing field was skewed to focus on policies that limit the political opposition or that favor the ruling party in order to gain electoral advantage and influence voters. Several surveys carried out in Serbia over the past few years show a rather dominant presence of Aleksandar Vučić in the major national television channels and public broadcaster as well as in the print outlets with the highest circulations, both which are controlled by the ruling party (Pavlović Reference Pavlović2020, 26). During the 2017 election campaign, Vučić received ten times more airtime than all the other candidates combined while he was portrayed in a positive context on 92 per cent of the front pages and 71 per cent on the television channels RTS, Pink and N1 (Maksić and Gruska Reference Maksić and Gruska2017, Crta 2017). The blurring of the difference between the state and the party also became more pronounced during the election period in 2017, when Vučić (who had been Prime Minister at the time) participated in the elections as the candidate of the ruling party, and in 2020 in the circumstances of the boycott by opposition parties and the COVID-19 pandemic. The opposition parties that had boycotted the election campaign were completely marginalized in the media outlets while the ruling parties almost completely dominated the campaign (Spasojević Reference Spasojević2021, 73-74). Vučić was also constantly portrayed as an irreplaceable leader and guardian of national interests in pro-government media. The media in this way not only emphasized Vučić’s central role in the country’s political life, but had sent the message that his survival in power is crucial for the national interest and the well-being of the country as was evident particularly in the 2023 election period where he ran under his own “AV” campaign (Crta 2024b, 63).

In clientelist relationships, governments benefit from being overrepresented in the media both in terms of content and coverage. However, the exchange is beneficial for both parties, as the media who publish positive news reports and have overwhelming coverage for the ruling party receive the most amount of money by the government in exchange either through project co-financing or through public procurement contracts for advertising. A journalist interviewed for the purpose of the research claimed that there does in fact exist a law on advertising from 2016 but it is old and does not recognize new methods of advertising such as digital, online advertising. In the draft proposal of the new law, platforms and social networks are mentioned, but they are not defined clearly enough, so it is not known exactly what is meant by that, whose accounts are monitored, who will control it, etc. (Interview with Journalists C and E 2024). The Law on Advertising includes the following:

Clear marking of political advertising, political advertisements must be clearly marked as such, so that citizens can recognize them. Parties are obliged to transparently show the costs of political advertising. REM monitors electronic media during campaigns and ensures that advertising does not exceed legally defined limits (Interview Journalist E 2024)

Monitoring media during election periods is the most important political aspect of the REM’s work. However, as discussed previously, the Regulatory Agency for Electronic Media (REM) is a captured agency used as an instrument for political manipulation and propaganda in the hands of the ruling party. A journalist from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network corroborates this fact:

REM has an obligation to respond to complaints and reports of irregularities related to reporting during campaigns. REM also publishes reports on media behavior during the election period and can sanction media for breaking the rules, although it is often criticized for insufficiently strict, adequate measures. Some international organizations, such as the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) and civil society criticized the inaction of REM during election campaigns (Interview with Journalist E 2024).

The Crta 2024 final report elucidated the passivity and non-transparency of REM during the December 2023 parliamentary elections in Serbia. REM only published part of the campaign monitoring data after election day, and only those collected in supervision over public media services and cable televisions, while delaying the publication of findings related to private televisions with national coverage in order to create a distorted picture of media pluralism in the campaign. Moreover, REM remained passive on the complaints filed by Crta (Crta 2024b, 8). This trend of disregard for the law and inaction by the REM was also observed in 2016 when REM decided not to make the monitoring reports publicly available and during the 2016 election period when it abandoned monitoring altogether (Kleut Reference Kleut, Dobek-Ostrowska and Głowacki2023, 68).

Clientelism was also prevalent throughout elections in addition to the media, where distribution of material gifts to socio-economically vulnerable citizens is one of the indicators of abuse of data from public records on the social status of citizens. The 2023 election period was also marked by testimonies of direct exchange of material gifts and services for votes in support of the ruling party, while state capture of the media, particularly for the purposes of political advertising, was used to limit the opposition and promote an aggrandized image of the Serbian President and ruling party. In illiberal politics, subverting elections and media go hand in hand where electoral manipulation – usually occurring before elections are held – focuses on capture of the media to silence critical voices while promulgating party interests in a positive light. The lack of political will to regulate and monitor the field of political advertising exposes domestic elites’ political instrumentalization of the media where the “captured” media become tools for legitimizing the interests of the ruling class: in this case, the SNS and Aleksandar Vučić. Democratic reform is once again merely declarative while political elites foster informal institutions (patronage networks vis-à-vis the media) that keep formal institutions (the media outlets) instrumentalized for their hidden agendas. In the next section, we analyze the legalization of the state-owned Telekom company in the recently adopted law on public information and the media in 2023, which was another instrument of state capture and subversion of the media, that would formally allow the government to return to co-owning and establishing media outlets.

Media Capture Through the Legalization of State-Owned Telekom

On October 26, 2023, the Serbian National Assembly passed two new controversial media laws, the law on public information and the media and the law on electronic media, the latter being an amendment to the previous law on electronic media from 2014. The newly adopted law on public information and media essentially cemented the government’s continued “capture” and imprisonment of the media as it stipulates that Telekom, with a market share of 53%, which is majority owned by the state, can establish media indirectly through subsidiaries, which was the case even before the proposal of the new laws (Telekom Srbija 2024). The new law merely legalized the current situation with Telekom, allowing the state to return to ownership of the media through the telecommunications provider. According to a journalist interviewed for the research, this caveat was simply a correction to the law passed in 2014 which had allowed internet operators to be founders and co-owners of media through related legal entities and had thus enabled the foreign telecommunications and Internet provider, United Media, to be founder of media. Now, the law had also legalized Telekom to be co-owner and founder of media outlets, creating a duopoly in the media space as the independent, foreign telecommunications provider, SBB, that owns the independent media outlets N1 and Nova S, is expected to compete with Telekom (Interview with Journalist D 2024). However, journalists and media experts argue that this legalization of state-owned Telekom to establish and own media outlets would have catastrophic consequences for Serbia as it would enable an incredible concentration of media, financial and political power in the hands of one company, and in the hands of one man, Aleksandar Vučić (Krstanović Reference Krstanović2023). This new caveat to the law on public information and the media would “displace from the market all those who are not connected to the criminal structures of Aleksandar Vučić and the SNS” (Krstanović Reference Krstanović2023).

The informal patronage network between the ruling party and the media became visible when Telekom purchased its first major acquisition in 2018 which was the Kopernikus cable operator owned by Srđan Milovanović, the brother of the former commissioner of the SNS for Niš, for 195 million euros (Ljubičić Reference Ljubičić2023). Suspicions about the government’s ownership of two additional television channels, TV Prva and TV O2 were raised when Srđan Milovanović purchased them a month following the sale of Kopernikus to Telekom (Faktor 2019). Telekom’s policy of acquiring other cable network operators was a strategy to fight with its biggest competitor SBB owned by the foreign investor, United Media Group. A journalist claimed that Telekom’s non-transparent acquisition of many media outlets enables the government, through Telekom, to exercise complete state capture of the Serbian media space (Interview with Journalist B 2024). Furthermore, they posit that United Media who owns the SBB operator in Serbia is outside the space that the government controls. However, what is happening now is that Telekom is trying in every possible way to diminish that influence by limiting the access of SBB in the cities as a provider including offering two years of free service to switch from SBB to Telekom which is a significant invasion of the state into every aspect of society (Interview with Journalist B 2024). Zoran Gavrilović from the Bureau for Social Research also claims that the Serbian Progressive Party “wants to control the media through a captured state. We have party totalitarianism, where the party wants to control everything, and the state is an auxiliary body” (B.N. 2023).

The notion of parties as patronage networks is further elucidated by the fact that taxpayers’ money that was poured into Telekom was used to finance companies and media owned by media moguls who support the ruling Serbian Progressive Party. An example of this was revealed in the 38-million-Euros-worth contract between Telekom Srbija and Wireless media, a company of Igor Žeželj, who is also the owner of the pro-SNS tabloid newspaper Kurir, one of the dailies with the highest circulation (European Western Balkans 2020). In 2019, Žeželj had used a part of the 38 million sum to buy the tabloid, Kurir. Previously Kurir had criticized the government but had once again returned to supporting the ruling party with the new ownership under Žeželj. These acquisitions are further evidence of the ruling party’s goal to monopolize the Serbian media space by weakening the SBB provider who is the owner of independent channels N1 and Nova S, the only channels that regularly invite government critics and opposition politicians.

The Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media (REM), which is responsible for issuing broadcasting licenses and monitoring the application of the law on electronic media and the law on public broadcasters, was supposed to ensure that Telekom behaved in a manner that did not violate media freedoms and acted in accordance with the media laws. However, clientelism was also prevalent in the REM where “ever since its establishment, frequencies have always been manipulated, usually obtained by media close to the government” (Interview with Journalist C 2024). Regardless of unethical and manipulative information as well as obscure reality shows, national pro-regime television channels such as Happy TV and Prva TV that frequently violate the law have never lost their frequencies and were never punished, and in the last frequency allocation cycle, REM granted them national licenses again (Interview with Journalist C 2024). The same journalist further posits that “as long as the president of the country is a guest on Pink almost every day, Pink will have a national license” (Interview with Journalist C 2024). The pro-government tabloid, Kurir, has also had 448 violations of the Journalists’ Code in 2023, and yet it receives large sums of money through public procurement contracts for advertising and through project co-financing, demonstrating the extent and scope of informal patronage networks (Kragulj Reference Kragulj2024). Gavrilović argues that if REM did its work in accordance with the law, many of these television channels bought by SNS affiliates with money funneled through Telekom, would not be able to function (B.N. 2023).

The informal patronage networks between the Serbian government and the media have enabled political elites to legitimize their interests in order to remain in a position of power. However, this relationship was not without its benefits to the media outlets who receive significant amounts of money in exchange for promoting pro-government bias as was elucidated through the competitions for project co-financing and through advertising, in addition to the legalization of Telekom to own and establish media. In Serbia, where there is a lack of political will for reforms coupled with a weak institutional setting, political elites have instrumentalized democratic institutions such as the media outlets for the purpose of legitimizing their interests and their own political agendas, which runs contrary to the normative interpretation of institutions acting as the drivers of domestic change. Instead of fostering genuine domestic change and compliance with democratic values, international organizations such as the EU have essentially facilitated the rise of informal networks in Serbia and the Western Balkan region as a whole.

Conclusion

The concept of political clientelism has been utilized in the contemporary literature on post-socialist transformation and the development of democratic institutions in the Central and Eastern European countries, and more recently, the Western Balkans. Serbia is part of a wider trend among both the former Yugoslav states as well as some EU Member States (Poland and Hungary) where state capture of the media has contributed to overall democratic backsliding in rule of law. In the Balkans, the democratic façade remains as the states seem to be captured by a strong executive that has fostered a complex, clientelist network vis-à-vis the media while only outwardly engaging in reforms to appease the EU. Stojaravá (Reference Stojaravá2020) argues that in such societies, control over the media is essential for illiberal regimes, as they provide twisted information in the form of Potemkin villages that reinforces the merits of the ruling elite thus enabling them to maintain their position of power.

The beginning of the post-socialist transformation in Serbia, as stated by Cvejić (Reference Cvejić2016), was marked by the almost unlimited power of one political party and its leader in directing the main determinants of social and economic life, and clientelist relations and informal concentration of power developed from the very beginning a ‘rules of the game.’ He argues that during the Milošević regime “clientelist relations penetrated to a greater or lesser degree to all the main institutions responsible for the functioning of the system: parliament, judiciary, government, local self-government, political parties and the media” (77). Thus, the political elites that had come to power in the post-transformation period following 2000 had merely adopted the old mechanisms of control vis-à-vis patronage networks, while media institutions became “integrated into the clientelist system as a tool or resource” (Örnebring Reference Örnebring2012, 510).

In Serbia, the main actors of clientelism are people who hold or aspire to positions of power, namely the ruling elites who were elected during the 2012 parliamentary elections. However, Bieber (Reference Bieber2018) argues that the Serbian Progressive Party lacked the same arsenals and resources for clientelism that the Milošević regime had during the 1990s, thus they had to adopt more subtle mechanisms of control rather than drawing on the same continuity of direct control (342). Concerned more with maximizing their power for the sake of winning elections, the Progressive Party and Aleksandar Vučić captured key institutions to legitimize their interests. The politicization of the media had benefitted the media moguls and editors with close affiliations to the ruling party through various subsidies received through project co-financing and public procurement contracts for advertising in addition to tax exemptions and money that was funneled through the state-owned telecommunications provider, Telekom. As Muno (Reference Muno2010) posits, the “cognitive dimension of clientelism identifies the feelings of loyalty, demerit and obligation as crucial factors for keeping patron-client relationships together” (9). In line with this argument, the “loyal,” pro-government print and television media in Serbia thus had an obligation to publish affirmative articles promoting government policy and facilitating the notion of the Serbian President as an irreplaceable leader and key actor for the success of the state. This type of patronage network was especially prevalent during the election campaigns in Serbia, where the majority of the media with national coverage were used to instrumentalize the ruling elites’ and Vučić’s political agenda.

Despite the adoption of the new media laws in 2014 and their amendments in 2023, Serbian political elites remained reluctant to democratize the media space in line with European standards. Any reform was instead declarative or partial with elites merely playing the democratic game while continuing to foster informal clientelist networks, namely through political instrumentalization of the media. By avoiding substantive changes to the legal order of the state, the Serbian political elites have entrenched their position in power, thus claims to EU accession were seen as an electoral strategy rather than a genuine intention to reform the media environment. Scholars (Pavlović Reference Pavlović2023, Bieber Reference Bieber2018, Richter Reference Richter2012, Richter and Wunsch 2019, Ɖorđević and Radeljić Reference Ɖorđević and Radeljić2020) argue that the European Union fosters non-democracy promotion as it tolerates and even legitimizes the clientelist policies of autocratic leaders such as Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia for the sake of regional stability, prioritizing the normalization of relations with Kosovo while relegating democratic institution building to a secondary role. In lieu of this argument, EU political conditionality, which would include fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, had the opposite effect in strengthening state capture in Serbia even as it triggered compliance with formal membership requirements (Richter and Wunsch Reference Richter and Wunsch2020, 43). As a consequence, the EU had instead entrenched rent-seeking elites thus enabling them to remain in a position of power with each new election cycle. We argue that such informal networks do not promote sustainable institutions based on a prevailing consensus of norms and value patterns. To conclude, we use a statement by one of our respondents who accurately describes the media environment journalists in Serbia face and the EU’s passive and simultaneously tolerant attitude regarding democratic backsliding and deterioration in media freedoms:

“I think Europe doesn’t know what to do with Vučić. I think they should be much more sensitive about the violence happening in Serbia and I cannot understand that Europe can bear with this kind of media pressure, under which we live. It’s not the case that we have so many media; now we have United Media and that’s it. Journalists here live in a terrible atmosphere. In such a terrible atmosphere in which they, if they don’t work in media owned and controlled by the state, they are treated like state enemies” (Interview with Journalist B 2024).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank their parents and grandparents, particularly Dr Ivan Gerić.

Disclosure

None.

Appendix: List of Interviewees

-

• Journalist A from the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia. 2023. Interviewed by author, January 23. Belgrade.

-

• Journalist B. 2023. Interviewed by author via Zoom, January 24. Novi Sad.

-

• Journalist C and Professor of Journalism at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad. 2024. interviewed by author by email, February 1. Novi Sad. Follow up interview via telephone: September 23.

-

• Journalist D from the Journalists’ Association of Serbia. 2024. Interviewed by author, January 23. Belgrade.

-

• Journalist E from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. 2024. Interviewed by author, October 10.