Twelfth Night is a very popular play in the theatre and during the last 100 years in particular it has inspired a staggering variety of approaches and readings by theatre directors and performers. Some directors emphasise the class war that is at the heart of the Malvolio narrative; others focus on sexuality and identity politics, which are fundamental to the Viola narrative. Some directors are seduced by realism, and aspire to create an Illyria that will be plausible and socially coherent, and others respond to the anti-realism in the play and flaunt its implausibility, its magical unrealism, its discontinuities and its topsy-turvy qualities so appropriate, in Shakespeare’s day, to the feast of 6 January, twelfth night.

Various trajectories can be discerned through the four centuries of Twelfth Night’s performance history: over the last 120 years Malvolio has become more of an object of sympathy, sometimes even a tragic hero, especially in the final scenes of the play; Viola having sung her way through much of the eighteenth century, became elegiac for much of the nineteenth, exquisite but essentially passive, before becoming rather more assertive and sexually enquiring by the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. Feste has grown from being an embarrassment, often marginalised by cutting, to a keynote figure, helping to establish tone and mood, a source of world-weary wisdom. However, the most crucial overall trend has undoubtedly been the move from seeing Twelfth Night securely as a comedy, to finding more unhappiness, misalliance, and indeed to seeing it as a comedy about to collapse into tragedy, a comedy infected by the proximity of Hamlet, which is close in date to Twelfth Night, rather than harking back to the broad comedy of Shakespeare’s other twins play, The Comedy of Errors. The play becomes a comedy haunted by the loss of Shakespeare’s son Hamnet, who would not come back from the dead to greet his twin sister Judith as Sebastian greets Viola, rather than a comedy intersecting, for example, in 2.5, with the technically brilliant physical comedy of The Merry Wives of Windsor. Some modern productions do buck the trend and not all modern Illyrias are full of doom and gloom, but it is currently the fashion to find less and less to laugh at in the play.

In order to discuss something of the territory Twelfth Night has ranged across in the course of its history in the theatre, this introduction begins chronologically, but moves to a more thematic approach when considering the diversity offered by post-Second World War productions. The major areas of investigation here are: the attempt to locate a production geographically, culturally and politically by means of its vision of the world of Illyria; the treatment of the Malvolio narrative; the treatment of the Viola narrative; the radical change in the theatrical fortunes of Feste; and the implied commentary on theatrical practice offered by recorded Twelfth Nights.

The first documented performance of Twelfth Night, in which Shakespeare himself presumably appeared as a performer, took place on 2 February (Candlemas) 1602. John Manningham, a young lawyer at the Middle Temple, records:

At our feast wee had a play called ‘Twelve night, or what you will’; much like the commedy of errores, or Menechmi in Plautus, but most like and neere to that in Italian called Inganni.

A good practise in it to make the steward beleeve his Lady widowe was in Love with him, by counterfayting a letter, as from his Lady, in generall termes, telling him what shee liked best in him, and prescribing his gesture in smiling, his apparraile, &c., and then when he came to practise, making him beleeve they tooke him to be mad.Footnote 1

Manningham’s enthusiasm for the Malvolio plot suggests that Malvolio’s suffering was not an issue for him and his understanding that Olivia was a widow indicates she was dressed in mourning. Given that Viola is now seen to be a star part, it is surprising that Viola’s plot line is only referred to implicitly, in Manningham’s reference to the use of twins in his comparison between Twelfth Night, Comedy of Errors and the Menaechmi. It is possible that Manningham’s omission here may reflect the fact that it takes an astute first time audience to register Viola’s name, which is only identified in the final scene of the play (5.1.225).

Twelfth Night probably premiered, and was mostly performed, at the Globe playhouse around 1600–1. However, relocating Twelfth Night to the Middle Temple for the performance that Manningham enjoyed would not have been difficult, despite different sight lines, acoustics and audience demographic in comparison with the Globe, because the Folio text is not demanding in terms of staging: it requires ‘several doors’ in 2.2; some kind of box tree in 2.5 (although productions have often run the joke of a palpably inadequate ‘box tree’ for the eavesdroppers to hide behind); and Malvolio is described as imprisoned ‘within’ in 4.2, which may have meant behind the doors at the back of the stage, presumably with a grille through which the actor playing Malvolio could speak.Footnote 2 Many of the play’s stage directions, such as the opening one ‘Enter ORSINO, Duke of Illyria, CURIO, and other Lords’ are left permissive, but the flexibility of ‘other Lords’ would be made precise in production. The play demands quite a few props – particularly jewels passing between various characters – and some kind of yellow-stockinged costume for Malvolio in 3.4.Footnote 3 The original casting is not known but boy actors would have played Olivia and Viola, and a small boy may have played Maria as there are references to that character’s height (1.5.168; 2.5.11; 3.2.52). It has been assumed that the role of Feste was written for Robert Armin, who had replaced Will Kemp as the clown of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, and the large number of songs given to Feste would certainly have provided a showcase for Armin’s singing skills.

In 1954 Leslie Hotson devoted a monograph to arguing that the first performance of the play was on Twelfth Night, 6 January, 1601. Hotson writes in thrilling style but the evidence remains completely circumstantial. Because Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, played at court before Queen Elizabeth and an Italian guest, Virginio Orsini, duke of Bracciano on 6 January 1601, Hotson imagines Shakespeare writing the play to order between St Stephen’s day, 26 December, and 6 January, and performing in conditions which very much reflect a 1950s vision of how Elizabethan theatre worked.Footnote 4 While Hotson’s case remains unproven, the notion of performing the play on Twelfth Night has appealed to many theatre directors over the centuries.Footnote 5

Twelfth Night was also performed at court for James I on Easter Monday, 6 April 1618, and on Candlemas, 2 February, in 1623, the year that the text of the play first became available for reading. Shakespeare had died in 1616 with Twelfth Night unpublished but in 1623 Shakespeare’s colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell saw the First Folio through the press, and this included Twelfth Night or What You Will. The records of Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels, use the title ‘Malvolio’ for the 1623 performance and two other early commentators also testify Malvolio’s ability to dominate the play.Footnote 6 Leonard Digges claims:

Meanwhile Charles I, in annotating his Shakespeare Folio, wrote ‘Malvolio’ by the title of the play, something which reads ironically in the light of those twentieth-century productions that have reconfigured the play’s action, casting Malvolio explicitly as a Puritan who is, by the end of the play, ready and waiting to start the English revolution that would deprive Charles of his kingdom and his life.

After the Restoration, Twelfth Night was assigned to Davenant’s Duke of York’s Men. Pepys saw it three times at Lincoln’s Inn Fields: on 11 September 1661, when Charles II was present, but, for Pepys (II 177), the play seemed a ‘burthen’ and he ‘took no pleasure at all in it’;Footnote 8 on 6 January 1663 Pepys (IV 6) thought it ‘acted well, though it be but a silly play and not relating at all to the name or day’; after a performance on 20 January 1669 he complained it was ‘one of the weakest plays that ever I saw on the stage’. By contrast John Downes records that the play ‘had mighty Success by its well Performance’, that ‘All the Parts being justly Acted Crown’d the Play’, which ‘was got up on purpose to be Acted on Twelfth Night’ (Downes 23). Downes records that the leading actor of the company, Thomas Betterton, took the largest role, Toby, but then Downes only lists the actors playing Andrew, Feste, Malvolio and Olivia, something which suggests that the Viola/Orsino narrative failed to make an impact, or may have been deeply cut, possibly even excised. Viola’s narrative, however, did get an airing in reworked form in the 1670s with the first performances of Wycherley’s The Plain Dealer, in which Fidelia, dressed as a man, courts Olivia, on behalf of Fidelia’s beloved master.

In 1703 William Burnaby adapted Twelfth Night as Love Betray’d; or the Agreeable Disappointment.Footnote 9 Love Betray’d was not a success, but it does offer insight into what Burnaby felt needed attention in order for Twelfth Night to work theatrically in 1703. For example, Burnaby has Cæsario (Viola) in love with Moreno (Orsino) for ‘Two years’ (11), rather than having Viola fall rapidly in love between 1.2 and 1.4. Cæsario sings for Moreno, as Shakespeare’s Viola suggests she will (1.2.57–8), although the Folio text gives her no songs. Concern about the cruelty of the plot against Taquilet (a combination of Malvolio and Andrew), is expressed by Emilia (Maria) who comments ‘If he shou’d come to lose his Place for his Love, this Business wou’d end too cruelly’ (25). At Cæsario’s prompting Rodoregue (Antonio) is explicitly pardoned and ‘shall share the blessings of this hour’ (60), whereas Shakespeare does not indicate how Antonio’s narrative ends. In addition Burnaby relocates the play to Venice, a popular location for later productions of Twelfth Night, and the Olivia character, Villaretta, becomes a widow, something which resonates with Manningham’s memory of Olivia in the 1601/2 performance.

Twelfth Night was then absent from the stage until 1741, when under the management of Charles Fleetwood at Drury Lane, Hannah Pritchard played Viola, while the consummate comedienne Kitty Clive began a long association with the role of Olivia. Clive was also famous for her singing skills and her performance helped reshape Olivia into a singing role for most of the rest of the century, although as Olivia, and Viola, sang more, Feste began to sing less.Footnote 10 The 1741 production also featured the Malvolio of Charles Macklin, who one month later was to astound London with a compelling Shylock, which moved away from the standard comic caricature of the time. As Macklin was researching Shylock when he first played Malvolio, it is possible his Malvolio may also have included some gravitas.

In the late eighteenth century Twelfth Night was often revived for one or two performances only, often around Twelfth Night. The fact the play was occasionally used for benefit performances suggests some degree of popularity.Footnote 11 Several of the individual actors who had great success with Twelfth Night during the latter part of the eighteenth century are memorialised by Charles Lamb and although he was writing ‘two-and-thirty years’ after some of the events he was recalling (Lamb 154), he vividly evokes, for example, the performance of James Dodd as Andrew and how ‘In expressing slowness of apprehension this actor surpassed all others’ (159). Lamb also argues for the unusual ‘richness and a dignity’ in Robert Bensley’s performances of Malvolio, and reminds his readers that ‘when Bensley was occasionally absent from the theatre, John Kemble thought it no derogation to succeed to the part’ (157), something which suggests a Malvolio tilting in the direction of decorum.Footnote 12 For Lamb, Bensley ‘threw over the part an air of Spanish loftiness. He looked, spake and moved like an old Castilian’ (158) and he evoked Don Quixote: ‘when the decent sobrieties of the character began to give way, and the poison of self-love, in his conceit of the Countess’s affection, gradually to work, you would have thought that the hero of La Mancha in person stood before you’.Footnote 13 Lamb confesses ‘I never saw the catastrophe of this character, while Bensley played it, without a kind of tragic interest’ (159). Sylvan Barnet produces evidence to suggest that ‘Lamb’s discussion of Bensley […] is Lamb writing of his own Malvolio, rather than of Bensley’s’ (187), and certainly Bensley’s Malvolio is remembered in a rather different vein by James Boaden:

I never laughed with Bensley but once, and then he represented Malvolio, in which I thought him perfection. Bensley had been a soldier, yet his stage walk eternally reminded you of the ‘one, two, three, hop’ of the dancing-master; this scientific progress of legs, in yellow stockings, most villainously cross-gartered, with a horrible laugh of ugly conceit to top the whole rendered him Shakespeare’s Malvolio at all points.

However, Bensley was best known for serious roles, and this plus the ‘grotesque’ element of his performances (Barnet 185) may have created a serio-comic mixture of a Malvolio.

Bensley’s Malvolio had the good fortune to play, from 1785 on, alongside the highly regarded Viola of Dora Jordan. Jordan was a comic actress, a particular favourite in breeches parts, but she also found pathos in the role, and won Charles Lamb over with her performance of spontaneity, particularly during her ‘Patience on a monument’ speech (2.4.106ff.; Lamb 155): Jordan ‘used no rhetoric in her passion; or it was nature’s own rhetoric, most legitimate then, when it seemed altogether without rule or law’ and the speech

was no set speech, that she had foreseen, so as to weave it into an harmonious period, line necessarily following line to make up the music […] but, when she had declared her sister’s history to be a ‘blank,’ and that she ‘never told her love,’ there was a pause, as if the story had ended – and then the image of the ‘worm in the bud’ came up as a new suggestion – and the heightened image of ‘Patience’ still followed after that, as by some growing (and not mechanical) process, thought springing up after thought, I would almost say, as they were watered by her tears.

The Public Advertiser (16 November 1785) also approved Jordan’s Viola which it found ‘serious, gentle, tender and sentimental’. Meanwhile Boaden, in his biography of Jordan, claims ‘the mere melody of her utterance brought tears into the eyes’ and Viola’s ‘passion had never so modest and enchanting an interpreter’ (Boaden, Vol. I, 76). Boaden also quotes Joshua Reynolds’s verdict that Jordan’s Viola ‘combines feeling with sportive effect, and does as much by the music of her melancholy as the music of her laugh’ (Vol. I, 221). Given all this musicality, and the fact that Jordan was famous for her singing ability, it is not surprising that this Viola also sang.

Several images of Jordan in the role of Viola survive. A painting by Hoppner has Jordan as Cesario in a hussar’s high hat and regimental coat, but with delicate, feminine features, whilst an illustration by Henry Bunbury of the duel scene accentuates the ample proportions of Jordan’s bosom and hips to such an extent that it seems impossible that her Cesario could have passed for a boy; nevertheless, it was presumably in a gesture towards a realistic presentation of twins that, on 10 February 1790, Jordan’s brother, George Bland, played Sebastian.Footnote 14

This was the period when many traditional comic routines were developed around the playing of the revelry of 2.3; for example, William Dunlap remembers with enjoyment that:

The picture presented, when the two knights are discovered with their pipes and potations, as exhibited by Dodd and Palmer, is ineffaceable [… Dodd’s] thin legs in scarlet stockings, his knees raised nearly to his chin, by placing his feet on the front cross-piece of the chair (the degraded drunkards being seated with a table, tankards, pipes, and candles, between them), a candle in one hand and pipe in the other, endeavouring in vain to bring the two together; while, in representing the swaggering Sir Toby, Palmer’s gigantic limbs outstretched seemed to indicate the enjoyment of that physical superiority which nature had given him.

Long term it was John Philip Kemble’s production of Twelfth Night which had the most significant impact, although Kemble built on the work of, for example, David Garrick, whose production of Twelfth Night is partly documented in Bell’s Shakespeare edition. Kemble’s published promptbook records the results of over twenty years’ work on the play: cuts, additions, erasures of inconsistencies, as well as his decision to reverse the opening two scenes of the play, an arrangement which has proved enduringly attractive to directors, particularly those wanting to open the proceedings with a tremendous storm.Footnote 15 Kemble also popularised songs that became perennial favourites, such as ‘Which is the properest day to drink?’ in 2.3; he restructured the action to produce strong curtains; and he reshaped the multi-focussed opening act so that Viola is more securely the star (Shattuck, 1974, ii). Meanwhile Andrew was built up, Feste cut back, especially his songs, and Antonio’s love for Sebastian much edited.Footnote 16 Olivia and Viola’s exchanges were trimmed, and rendered more decorous. Kemble was particularly careful about regularising Shakespeare’s text and, for example, Orsino does not fluctuate between ‘count’ and ‘duke’ but is consistently a ‘duke’; and Toby is always Olivia’s ‘uncle’, not her ‘cousin’. Many of Kemble’s adjustments to Twelfth Night became standard theatre practice, and could still be seen at work in later productions by, for example, Henry Irving (1884), Frank Benson (1892) and Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1901).Footnote 17

John Liston, who played Malvolio for Kemble in later performances, had only qualified success in the role according to John Genest (Vol. VIII, 227): Liston ‘was truly comic’ in the letter scene (2.5) and ‘when he entered cross-gartered’ (3.4), but ‘on the whole Malvolio was a part out of his line’. However, the singing Olivias (see Figure 1) and Violas continued to be popular and it seems a logical progression that in 1820 Twelfth Night became an opera: Frederick Reynolds adapted the text, and Henry Bishop provided the music.Footnote 18 Introduced songs included ‘Who is Sylvia’ from The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and the production featured ‘The Masque of Juno and Ceres’, which owed something to The Tempest. Maria Tree played Viola, a role her sister Ellen Tree/Kean was later to have great success with; while Leigh Hunt admired Maria Tree’s performance, the fact he spent thirteen lines of his review salivating over the display of her legs indicates he was not merely interested in her acting.Footnote 19 Although the production’s Malvolio, William Farren, was famous for straightforwardly comic roles, this operatic Twelfth Night is also possibly the first production to have staged 4.2, the dark room, with Malvolio visible to the audience, something which, as David Carnegie argues, has profound repercussions in terms of generating sympathy for the character (Carnegie 395; see pp. 44–5).

1 Elizabeth Farren as a lute-playing, singing Olivia.

For most of the nineteenth century Twelfth Night was only intermittently popular, although some individuals, such as Samuel Phelps, achieved critical and commercial success with the play. Phelps’s 1848 Twelfth Night featured Phelps himself as a Malvolio who had a ‘frozen calm’ and who ‘sails about as a sort of iceberg, towering over spray and tumult […] There is condescension in all he does […] His acceptance of his lady’s love is quite as approving as it is grateful’ (Bayle Bernard, Weekly Dispatch, quoted in W. M. Phelps 162). Henry Morley (Examiner 24 January 1857) provides more detail: this Malvolio was ‘in bearing and attire modelled upon the fashion of the Spaniard, as impassive in his manner as a Spanish king should be’, and Phelps took Olivia’s comment ‘you are sick of self-love, Malvolio’ as the key note to the role. Morley comments that ‘we are not allowed to suppose for a moment that [… Malvolio] loves his mistress’ and he ‘walks […] in the heaviness of grandeur, with a face grave through very emptiness of all expression. This Malvolio stalks blind about the world; his eyes are very nearly covered with their heavy lids, for there is nothing in the world without that is worth noticing, it is enough for him to contemplate the excellence within.’ Morley records that ‘When locked up as a madman [Malvolio] is sustained by his self-content, and by the honest certainty that he has been notoriously abused’ and Phelps’s delivery of Malvolio’s final line was memorable: ‘he is retiring in state without deigning a word to his tormentors’ when suddenly ‘marching back with as much increase of speed as is consistent with magnificence, he threatens all – including now Olivia in his contempt – “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you!”’ Although most critical attention was focussed on Phelps’s new reading of Malvolio, there was considerable praise for the decision to cut back on traditional comic business which had accrued particularly around 2.3, the drinking scene. The Phelps promptbook (S11) also indicates a significant return in many respects to Shakespeare, as opposed to Kemble.Footnote 20

In 1850 Charles Kean opened the Princess’s Theatre with a production of Twelfth Night which built on the high reputation of the Viola of Mrs Charles Kean/Ellen Tree.Footnote 21 Tree had first appeared in Twelfth Night as Olivia, when aged seventeen, but from 1832 she had frequently played Viola, to acclaim in England and the US.Footnote 22 In 1840 she played the role for Eliza Vestris at Covent Garden, using the costume of a ‘Greek boy’ for Cesario (T 26 June 1846), that is, a hat with a tassel, and a tunic with full skirts to the knees. Tree’s costume was to be imitated by many Cesarios over the next sixty years although, as Russell Jackson points out, ‘The danger here was of making Sebastian look effeminate in order to allow for the modesty of the leading lady’ (24). Tree’s Viola was appreciated for her ‘intelligence and feminine grace’ and the creation of a ‘lovely, pensive’ characterisation (Charter 8 September 1839); in 1850 her Viola displayed ‘the archness and the poetry, the sportiveness and the pensiveness, the wondrous variety and combination of opposites, the sauciness and the modesty of the assumed boy and the real woman’ (ILN 5 October 1850). John William Cole praises the ‘exquisite pathos’ of this Viola (333), but he also records a comparison with Dora Jordan’s performance which is illuminating. Citing the memories of an elderly man in the audience who remembered Jordan, but preferred Ellen Kean’s performance, Cole characterises Jordan’s Viola as having ‘greater breadth, higher colouring, more exuberant spirits, and a broad-wheeled laugh peculiar to herself’ (334); Cole thus implicitly argues that Viola should be ‘exquisite’. Meanwhile the production’s Malvolio, Drinkwater Meadows, was restrained, ‘a natural man – a disposition perverted by personal conceit, but not dishonourable; one who thinks nobly, but acts vainly; wise of purpose but foolish and overweening in conduct’ (ILN 5 October 1850).

That the ‘feminine grace’ of Ellen Kean’s performance was crucial in garnering such approbation for her Viola/Cesario, is suggested by the contrasting fortunes of Charlotte Cushman’s Cesario, at the Haymarket Theatre in 1846, which, on the evidence of the illustration published in The Illustrated London News (11 July 1846) avoided traditional femininity. The Times reviewer (26 June 1846) records ‘an intelligent version of the part’ and ‘no indolent following of convention’, but the reviewer did feel that ‘the gentle and delicate Viola’ was not suited to Cushman, famed as she was for ‘impulsive, passionate display’. Cushman avoided ‘gaiety’ and emphasised ‘earnestness throughout’; so the famous point ‘I am the man!’ (2.2.22) instead of, as traditionally, being ‘spoken in a tone of mirthful triumph’ and ‘a playful tap on the hat’ was rendered ‘as the expression of a serious conviction’. Cushman also ‘more than usually suppressed’ pathos during ‘She never told her love’ (2.4.106) by ‘assuming the tone of an indifferent narrator’. Cushman’s unconventional Cesario, and the contrast it provides with Ellen Kean’s more popular rendition of the role, reveals much about the formulaic femininity that nineteenth-century reviewers wanted from Viola/Cesario.

Kate Terry’s 1865 Viola, directed by Horace Wigan at the Olympic theatre, was also unconventional, as Terry appeared as Sebastian as well as Viola, with a dummy Sebastian being used for the final scene (Pall Mall Gazette 23 June 1865).Footnote 23 Reviewers felt this trick confused many in the audience, and Wigan’s company were not playing to their strength being ‘accustomed to works of a totally different kind’, generally avoiding Shakespeare, and being known for their ensemble work (T 9 June 1865). However, Terry’s Cesario was praised for maintaining an ‘innate modesty of […] nature, the melancholy consequent upon a hopeless love’ as well as ‘the dashes of gaiety that reveal themselves when she would assume somewhat of the boyish pertness’ (T 9 June 1865). Her ‘earnest delineation of feeling’ was also praised (Era 11 June 1865) but Terry was castigated for employing traditional business in the duel with Andrew: ‘the attempts to run away, and the dragging back and pushing on by main force’ (Fraser’s Magazine August 1865) and reviewers were not impressed that the role of Feste was played by Nelly Farren, who ‘trained in the fatal school of burlesque’, and performed, it was claimed, as if ‘a clown must always dance off the stage’ (Pall Mall Gazette 23 June 1865).

Generally actresses who managed to follow Ellen Tree/Kean in stressing the femininity of Cesario were those who enjoyed critical success with the role of Viola. For example, Adelaide Neilson played the role to acclaim in the United States as well as in her native England, working with a variety of managers including Augustin Daly, and later with Neilson’s partner Edward Compton. Neilson’s early death in 1880 contributed to the legend of her Viola, which was applauded for finding ‘the maidenly, boyish, womanly Viola of the poet’, for ‘artistic finish […] archness and piquancy’, and her finest scene was the duel ‘where she clearly reveals the woman’s heart beneath the garb of the gentle youth’ (CDT 10 December 1879). William Winter concurs, stating that Neilson’s Cesario approached the duel with ‘shrinking feminine cowardice, – commingled of amazement, consternation, fear, weakness, and dread of the disclosure of her sex’ which was ‘deliciously droll’ (Winter 44). Helena Modjeska also achieved critical plaudits as Viola: George Odell thought her ‘incomparably the finest [Viola] I ever saw, in pensive charm, in humour, in grace, in refinement, and in retention of womanly delicacy even in the farcical duel scene’ (Odell, Vol. XII, 23). Of the duel Sprague claims that ‘Madame Modjeska realized that her antagonist was not in the least dangerous’ and ‘had a good opportunity to hit him, and refrained from doing so, out of “womanly generosity”’ (Sprague 9). The Boston Evening Transcript (13 January 1887) also found what it called ‘the natural abhorrence of her sex to shedding blood’. Modjeska’s published acting text indicates that instead of Feste her Cesario sang to Orsino in 2.4, and George Becks’s annotation on a Daly promptbook (S38), which offers a lively discussion on possible stagings of the tormenting of Malvolio in 4.2, notes ‘Modjeska and others have had a barred arch opening under the steps of house and very good too.’

Laurie Osborne argues that the cuts in nineteenth-century performance editions, and the performances based on them, ‘diminished the aggressiveness and persistence of [Viola’s] surrogate wooing of Olivia as well as her self-consciousness about the role she is playing’, whilst simultaneously downplaying Viola’s wit; idealising her according to contemporary standards; undercutting ‘Olivia’s authority over her household’; and reducing Olivia’s wittiness in dealing with Cesario (1996a, 67). The real test for many nineteenth-century Violas, however, was the duel between Cesario and Andrew, which presented serious issues of decorum. In 1904 Elisabeth Luther Cary published an essay on nineteenth-century Violas which records Cary’s complete opposition to the traditional, undignified comic business: the ‘running away and pulling back, the ludicrous fight very literally at the point of the sword’ (Cary 285). Not all Cesarios were cowards; as early as Burnaby’s Love Betrayed the plucky Cæsario overhears Taquilet’s (Andrew’s) expressions of cowardice and resolves to give the duel her best shot. Viola Allen hit and pummelled Andrew on the back (S56) but critic and historian William Winter preferred a less combative approach such as that of Marie Wainwright’s Cesario who showed ‘jaunty demeanor, hampered by fluttering consternation’ which was, Winter pronounced, ‘exactly in the right vein’ (60–1).

While Viola was the focus for many nineteenth-century reviewers of Twelfth Night, that changed in 1884 when Henry Irving’s production found a new level of tragedy for Malvolio in the play, a reading that was at that time extremely controversial. By Irving’s standards his production of Twelfth Night was a failure, and when, after a tough first night, during a heatwave, in a stiflingly hot theatre, Irving made a speech rebuking his audience – after some of them had booed him – he unleashed a ‘furious war of words’ (CDT 13 July).

In some ways the production remained conventional: Irving followed Kemble’s cuts a great deal and indeed owned one of Kemble’s marked up promptbooks (S6). His production was also extremely picturesque: some of the sixteen scenes were designed by Hawes Craven, who was to produce the apotheosis of pictorial Twelfth Night sets for Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s 1901 production. William Archer (Macmillan’s Magazine August) records ‘ornate Renaissance palaces with their cool balconies and colonnades and their mazy arabesque traceries’ which ‘look forth among groves of palms, and plantains, and orangetrees, and cedars, over halcyon seas dotted with bird-like feluccas and high-prowed fishing-boats’. Some thought the production ‘over-dressed and over-mounted’ and that it was inappropriate that Olivia should live ‘in a building larger than Buckingham Palace, constantly attended by a suite of elegant ladies got up regardless of expense in Venetian finery of the sixteenth century’ (Freeman’s Journal 14 July). The cast also included ‘crowds of spearmen, torch-bearers, and richly-attired lords and ladies’ (Reynolds’s Newspaper 13 July). The biggest bone of contention in Irving’s production, however, was vividly summarised in a cartoon in Punch (19 July) where the ghost of Shakespeare appears to Irving in his sleep brandishing a placard with the words ‘Will you play Malvolio in a-merry-key?’ Irving’s Malvolio was ‘scholarly’ but ‘too sombre’ (Reynolds’s Newspaper 13 July); ‘too stern, too grave’ and unlikely to be fooled by the letter trick (Newcastle Courant 18 July); and most damningly he ‘talked through his nose, and the conception, so far from being original, was a rechauffé of Phelps’ (The Drama 12 July).Footnote 24 Archer (Macmillan’s Magazine August) argued that approaching 4.2 ‘in a tone of serious tragedy’, as Irving did, ‘is to introduce a discord’; that Malvolio should not be ‘stretched on the straw of a dungeon worthy of Fidelio’; that this Malvolio was ‘a mere repetition of [Irving’s] Shylock’; and to exit ‘like the baffled villain of melodrama, not the befooled fantast of comedy’ was wrong. By contrast The Times (9 July) thought the production ‘strikingly original in conception’ and felt respect for this Malvolio, ‘an ascetic Puritan, sober and quaint in garb, and moreover, aged in appearance’, whose ‘explosion of wrath at the end’ was ‘wrung from him by a sense of the cruel deception practised upon him’.

Ellen Terry’s Cesario was also controversial. The Times (9 July) found ‘a departure from traditional lines’ in this ‘bright and somewhat mischievous hoyden, who enters thoroughly into the fun of her disguise’. Terry

was acutely aware that Viola thinks first of serving Olivia but, finding that impossible, dons disguise to cover the impropriety of a woman serving a bachelor like Orsino. In his presence she was embarrassed by her garb, but with Olivia she could relax and enjoy the joke.

In the view of Elisabeth Luther Cary, Terry enjoyed the joke too much and Cary disapproved of this ‘laughing Viola, uncontrollably amused by her disguise and smiling at her grief with a most infectious merriment’ (276, 278). Terry was also censured for ‘introducing Cockney pronunciation and London affectations which could not have been known to the Viola of the play’ (CDT 13 July).

The Illustrated London News (16 August 1884) published a full page of sketches showing the characters as they appeared in this production: the three images of Irving’s Malvolio dominate but the sketch of Ellen Terry’s Cesario indicates she would never pass as a boy, even though realism obtained in the casting of Terry’s brother, Fred, as Sebastian.Footnote 25 Sebastian was a token role in this production and when, as a response to the negative press, Irving cut back the text even more, he came close to eliminating Sebastian and Antonio altogether. Irving also substantially reduced the role of Feste and had him played by a performer who couldn’t sing (Freeman’s Journal 14 July). By the time the production was taken to the US, however, reviewers had begun to recover from the first shock of Irving’s conception and the production fared slightly better.

The critical preference for melancholic, piquant and exquisite Violas, Violas who epitomised the (imaginary) wilting sister, ‘smiling at grief’ (2.4.111) rather than the Cesario who is ‘saucy’ at Olivia’s gates (1.5.162) risked depriving the role of energy and drive. For example, Viola Allen’s Cesario was judged too ‘self-confident’, and, because of this, missing in ‘the poetic charm’ of the role, and so, even though Allen managed to avoid ‘the “mannishness” that is apt to offend’, she did not evoke ‘the struggle Viola was undergoing in her endeavor to induce another woman to become the wife of the man she herself loves’ (CDT 22 December 1903). Allen’s Cesario might wear ‘Albanian white kilts’ and a ‘red and gold Zouave jacket’ (NYT 9 February 1904) that looked back to Ellen Tree, but her Cesario was not as successfully feminised as Tree’s had been.Footnote 26 Elisabeth Luther Cary (278–9) went so far as to identify the ideal Viola as that of Edith Wynne Matthison simply because of Matthison’s lack of, as Cary saw it, unbecoming merriment in performance. Non-normative Violas did occasionally appear: according to the New York Herald (24 March 1914) the ‘keynote’ to Margaret Anglin’s interpretation of the role ‘was repression’, but when influential theatre critic William Winter produced a whole essay on the ‘Character of Viola’ (Winter 35–9), his emphasis on patience, self-sacrifice, constancy, all evoke the gold standard, for Winter, as far as Viola was concerned: Ada Rehan’s performance in the 1893 Twelfth Night directed by Augustin Daly.

2 Orsino’s court, from the souvenir of Augustin Daly’s 1893 production.

Daly’s Twelfth Night, as with all Daly’s Shakespeare productions, was sumptuous, beautifully upholstered, gorgeously costumed and featured large numbers of extras (see Figure 2). Although Daly rearranged the play radically – opening with Sebastian and Antonio (2.1), and a song from The Tempest, then proceeding to Viola (1.2), before a long Orsino scene (1.1 and 1.4) – the spectacle seduced many.Footnote 27 There was ‘a lovely Oriental dance in Act 1’, music by Bishop, Purcell, Arne and ‘Elizabethan sources’ (NYT 22 February 1893), but 618 lines of the play were cut (Felheim 252). Ada Rehan’s Cesario maintained a ‘pensive melancholy’ and ‘Even in the rare moments of Viola’s frivolity there is still present the echo of the minor key in which the characterization is consistently pitched’ (Illustrated American 15 April 1893).

Daly brought the production to London for a successful run in 1894 and was so pleased with the English reviews that he published an anthology of extracts, not all of them unequivocally admiring, in a souvenir programme. The anthology concentrates on Rehan’s Viola – Malvolio is hardly mentioned – and stresses her femininity: she combined ‘exquisite maidenly reserve’ with ‘a woman’s delight in pleasantly hoaxing the sterner sex’ (Morning Post); she was ‘exquisitely pathetic’ in 2.4 (Daily News); she regards Olivia ‘with pity and sisterly regard’ (Daily Chronicle); she displays ‘tender and subdued womanliness’ (St James’s Gazette). Meanwhile although the Daily Chronicle is quoted as claiming ‘The excuse for the introduction of dances is seized, and a good deal of music is interpolated with happy effect’, the programme does balance this praise with the Athenaeum’s reservation that, ‘delightful’ though the production was, ‘too much stress is laid upon the setting, and accessories are elevated into undeserved and, in a sense, inartistic prominence’. But overall the production was a tribute to Daly’s managerial acumen in adapting Twelfth Night to suit contemporary theatrical taste and he achieved a significant commercial success.

In 1895, a year after Daly’s vision of Twelfth Night played in London, a stark contrast was on offer in the form of a production by William Poel, then embarking on his campaign to remove scenic clutter from the Shakespearean stage and to return to what he claimed to be original staging practices. Poel was not the first to experiment with Twelfth Night and so-called original staging practices: Karl Immermann mounted an original practices Twelfth Night in Germany in 1840 ‘in a (makeshift) hall with an amateur cast’ (Foulkes, 2002, 40). Poel’s claims to authenticity were also often contentious. Gestures towards ‘original practices’ were certainly in evidence: in Poel’s Twelfth Nights, music was by the Dolmetschs, it was composed in imitation of Elizabethan music, and it was played on instruments built in the early modern period. Sword-play was directed by Captain Hutton, who refused to use modern foils. Less obviously authentic were Poel’s decisions to cast primarily according to voice pitch, thus creating an anachronistic sense of orchestration in relation to the verse speaking, and his excision of Malvolio’s dark room scene.Footnote 28 William Archer contended that although the programme described the production as ‘Acted after the manner of the Sixteenth Century’ in fact it was ‘Staged (more or less) after the manner of the sixteenth century and acted after the manner of the Nineteenth Century Amateur’ (Speaight, 1954, 103) and complained that 251 lines were missing (Speaight, 1954, 104).

The provocation of Poel’s claims to ‘authenticity’ gained extra impetus, as far as Twelfth Night was concerned, in February 1897 when Poel staged the play in the Hall at Middle Temple, the venue for the performance John Manningham had enjoyed in 1601/2. Poel was not the first to envisage performing in this location. Elizabeth Robins and Marion Lea had previously made an attempt to stage Twelfth Night at Middle Temple, on twelfth night in 1892. Their proposal was to stage the play ‘in strictly Elizabethan style, with restored text, little or no scenic effect beyond arras hangings, but with rich costumes and special attention to the music’.Footnote 29 Robins and Lea were refused permission, but Poel got the go-ahead and once the precedent of staging a modern Twelfth Night at the Middle Temple had been set, productions of the play in that location became a rather recurrent event.Footnote 30 Poel’s Middle Temple Twelfth Night used a raised platform stage, plus, confusingly, given the original practices agenda, a proscenium with columns holding tapestry curtains (Mazer 70), and a raised gallery at the back of the stage area. It was a grand event, and was attended by the Prince of Wales, but while Poel’s ideas found favour with those reviewers who enjoyed bare boards Shakespeare, theatre practice did not change overnight. Daly’s sumptuous, upholstered, musical Twelfth Night played to the contemporary market while Poel’s Twelfth Nights were seen primarily as a curiosity, even an aberration.

The Early Twentieth Century

The beginning of the twentieth century saw three very different but extremely long-running Twelfth Nights reconfiguring the play for contemporary audiences. Firstly, the Benson Company’s Twelfth Night, which originated in the early 1890s, toured throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century and while the company never achieved a particularly high profile in London, these tours brought the Benson version of Twelfth Night to a very large number of people over the years. Benson’s Illyria was full of comic business, it was athletic, physical and, by the standards of the day, it did not invest heavily in sets because of the demands of touring. The comedy of drunken behaviour was stressed, and there was much farcical hitting and slapping by most characters, including Viola, and during the duel with Andrew, Cesario not only ran at Andrew but beat him on the back with her fists, before Andrew then chased Cesario around the stage (S44). The production made enthusiastic use of songs; the drinking scene included much business such as blowing smoke in Malvolio’s face, tweaking the tassel of Malvolio’s ridiculous night cap etc. (S44). The production usually omitted 4.2 – the tormenting of Malvolio – and cut the final scene so deeply that the pace towards the end must have been frantic.Footnote 31 Frank Benson’s Malvolio was described as a ‘lean pantaloon’ (T 6 February 1901), a commedia reference which suits the comic physicality of this Twelfth Night.

A less physically robust but decidedly pictorial approach to Twelfth Night was adopted by Herbert Beerbohm Tree who, in 1901, opened his production while England was in official mourning for the death of Queen Victoria. The black mourning gowns on display in the stalls on opening night provided a stark contrast to Olivia’s costume, a white Elizabethan dress with black trimmings, which Modern Society (16 February) felt inappropriate for a woman mourning her brother. In fact the costumes and sets for this production stole most of the reviews, and Hawes Craven’s backdrop for Olivia’s garden, which offered a perspective view of steps rising up to dizzying heights, received rave notices.Footnote 32 The glory of this setting for Hearth and Home (16 February), however, did impose a ‘strain on the credulity’, because it meant that quite surprising sections of the action, including Antonio’s arrest, clearly and unequivocally took place in Olivia’s private garden. Orsino’s palace was also impressive and ‘Venetian in its glittering tesseroe’ (Sporting Times 9 March).

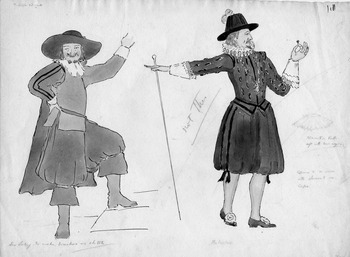

Tree played Malvolio ‘mincing, walking with much hip movement, finnicky, smiling, comically dignified, with a wealth of by-play’ (Sporting Times 9 March) (see Figure 3). He was often accompanied by a group of four minions, dressed in clothes identical to Malvolio’s, and the function of these minions was to reflect, and keep the comic focus on Tree. Dramatic World (March) enjoyed this Malvolio’s ‘artificiality […] his consummate coxcombry, his utter ignorance that anyone is laughing at him, his portly arrogance, and his almost sublime indifference to any interest but his own’ but also noted that ‘in the prison scene his awakening is pathetic’. Hearth and Home (16 February) indicates that Olivia allowed Malvolio ‘to toy with her hair’, something Malvolio could easily misread as encouragement, and it records of Malvolio’s final exit that ‘after vowing revenge he tears off his badge of office and stalks away, majestically dignified in his wrath’.Footnote 33 The Manchester City News (16 February) thought this Malvolio ‘a model of dignity and fatuous self-approval, passionately self-enamoured, his mortification in his defeat rises almost into tragedy, and his resentment at the indignities heaped upon him leads to his surrender of office and a contemptuous abandonment of his gold chain’. Several reviewers referred to the, by now traditional, reference to Don Quixote (e.g. Whitehall Review 10 October 1901).

3 Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Malvolio in Tree’s 1901 production.

Tree’s biographer, Hesketh Pearson, took a cautious view: ‘Tree was constantly inventing comic business, such as a careful inspection through his glass of the statue of a nude female figure, varying his reactions to it from strong disapproval to leering delight’ and such inventiveness overall gave ‘an unforgettable impression of Beerbohm Tree’s Malvolio, with incidental verbal music by William Shakespeare’ (Pearson 130). Something of the accuracy of this statement can be gauged from the inventive business Tree used to close 2.3. Promptbooks reveal that first Feste returned ‘as ghost. [Toby and Andrew] scream and go out of door. Clown drinks at last bottle. Goes to fire: sinks down & swigs’ (S46). After this Malvolio reappeared ‘in nightshirt and nightcap, with drawn sword and frantically bulging eyes, to seek in the peaceful darkness for imaginary dangers, and to thrust Don Quixotic-like, at candle-sticks and fallen chairs’ (Clarion 16 February 1901). Another comic elaboration was Tree’s entry in 2.5 when:

Descending the steps of the terrace, head in air, with stupendous self-importance, he tripped and almost fell headlong, but recovered his balance in the nick of time and managed to descend in a dignified sitting posture

but ‘to show that it had been his intention to take a seat at that precise spot, he calmly lifted his eyeglass and inspected the surroundings at leisure, the effect being fantastically funny’ (Pearson 130).

Lily Brayton’s Viola was generally praised, and this was an important role for Brayton, who had played Olivia for the Bensons in the previous year, but who was not, at that time, well known in London. As Cesario, Brayton donned ‘white tunic and crimson velvet sash, with crimson leggings, high boots embroidered with gold, and on her dark hair a fisherman’s knitted cap, also crimson’ (Court Circular Fashion Notes 16 February), a costume that looked back to Ellen Tree. Despite the lavish spending on costumes and set, the production recovered its costs in three weeks (People 31 March 1901), and Tree issued a souvenir brochure of twelve colour plates for its fiftieth performance.Footnote 34

Another Twelfth Night that ran for decades was that first mounted by Julia Marlowe and her partner E. H. Sothern in 1905 and which toured the US and Canada. Marlowe originally played Viola as early as 1887 and by 1919 there were suggestions the 54-year-old actress had ‘become rather mature in appearance for Viola’ (GM 2 December 1919) but Marlowe’s femininised Cesario – she ‘affects horror at the idea of drawing a sword’ – and Sothern’s robust characterisation of Malvolio as a ‘thoroughly affected ass’ (GM 25 April 1913) proved enduringly popular. Marlowe’s biographer Charles Russell hails her approach to Viola as innovative in its melancholy, its intelligence and emphasises the ‘diligent study’ Marlowe had devoted to the role.Footnote 35 As an example of Marlowe’s innovation Russell cites Viola’s opening lines, which, he claims, it was customary to play ‘to a somewhat lively tempo and for Viola to show to the world a face of youthful curiosity’ (47). Marlowe felt this was wrong and instead here ‘struck an undertone of melancholy’ (Russell 48). Sothern’s Malvolio was broadly played for comedy: Russell quotes a review recording Sothern’s ‘pursed, reticent mouth, his prim and pompous gestures’ plus ‘that self-consciousness which brings all Malvolio’s troubles upon him’ (547). By 4.2, however, Sothern was playing equally enthusiastically for tragic effects and the scene opened with the sound of Malvolio ‘mumbling’ and ‘clanking his chains’, and closed with groans of despair (S62, 63). The Sothern and Marlowe promptbooks, which Russell states were prepared by Marlowe (xxi), are full of extensive comic business, and this necessitated deep cutting to compensate for the running time added by these comic set pieces. Some aspects of the production, such as the use of mandolin music to accompany the willow cabin speech, or the performance of an eight-minute musical overture at the beginning of the play, might not appeal to modern theatrical taste, but this production of Twelfth Night sold well for twenty years.

Illyrias full of clutter and comic business did not, however, have a complete monopoly. While Poel’s productions were uneven, his ideas had struck a chord with other directors. The Times (4 May 1909) records a Twelfth Night at the Royal Court, produced by Gerald Lawrence and Fay Davis, where ‘The lack of scenery is positively pleasant to the eye’. In 1911 Lewis Casson, at Annie Horniman’s Gaiety theatre in Manchester, stripped back Twelfth Night, drastically trimmed the cakes and ale business, played a streamlined text, and had Edyth Goodall and Irene Rooke alternating Viola, ‘playing it a week in turn’ (Pogson 114). Then in 1912, one of Poel’s former actors, Harley Granville Barker, went a step further in working with Poel’s ideas whilst also adapting them realistically to contemporary taste.

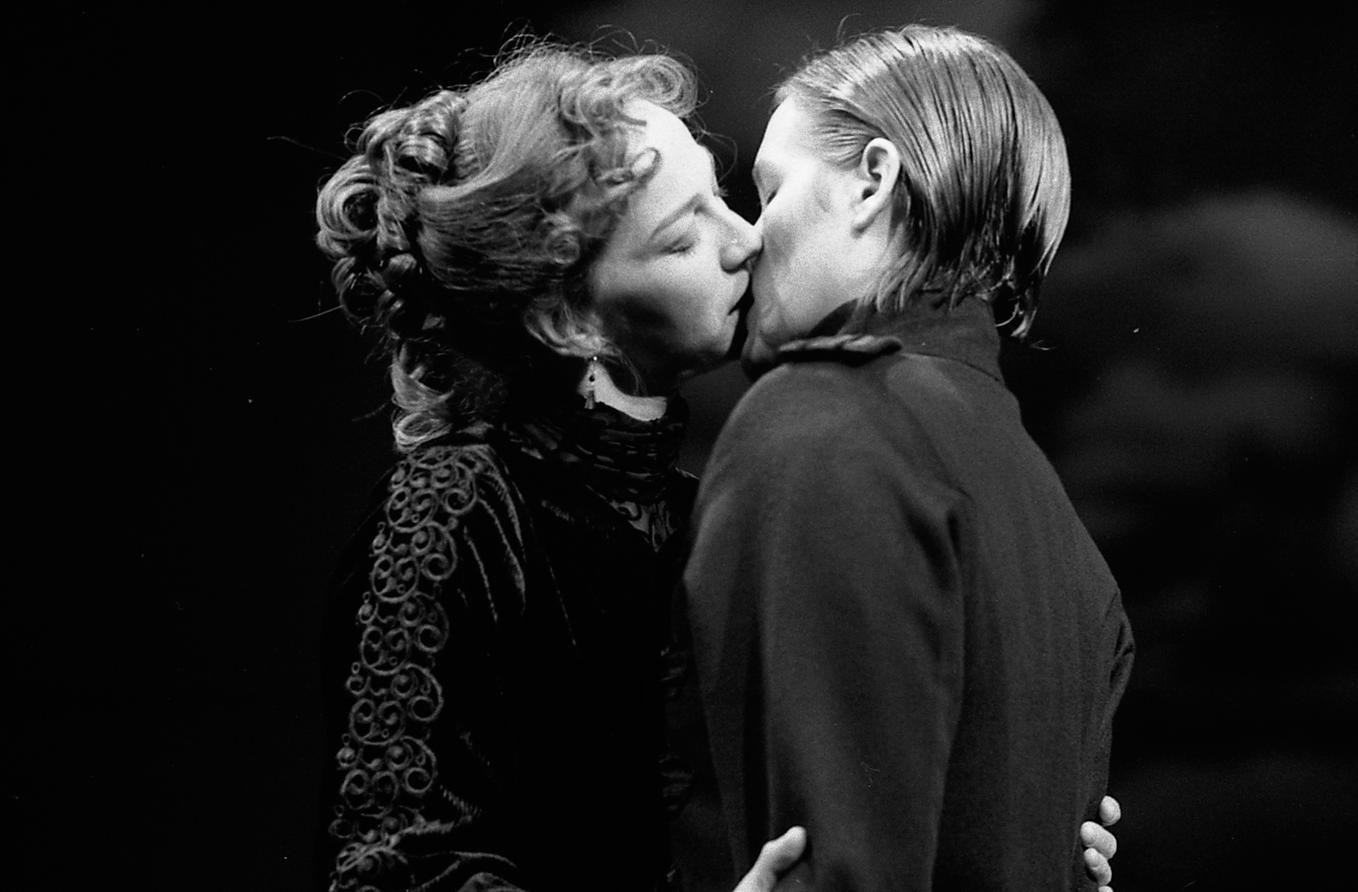

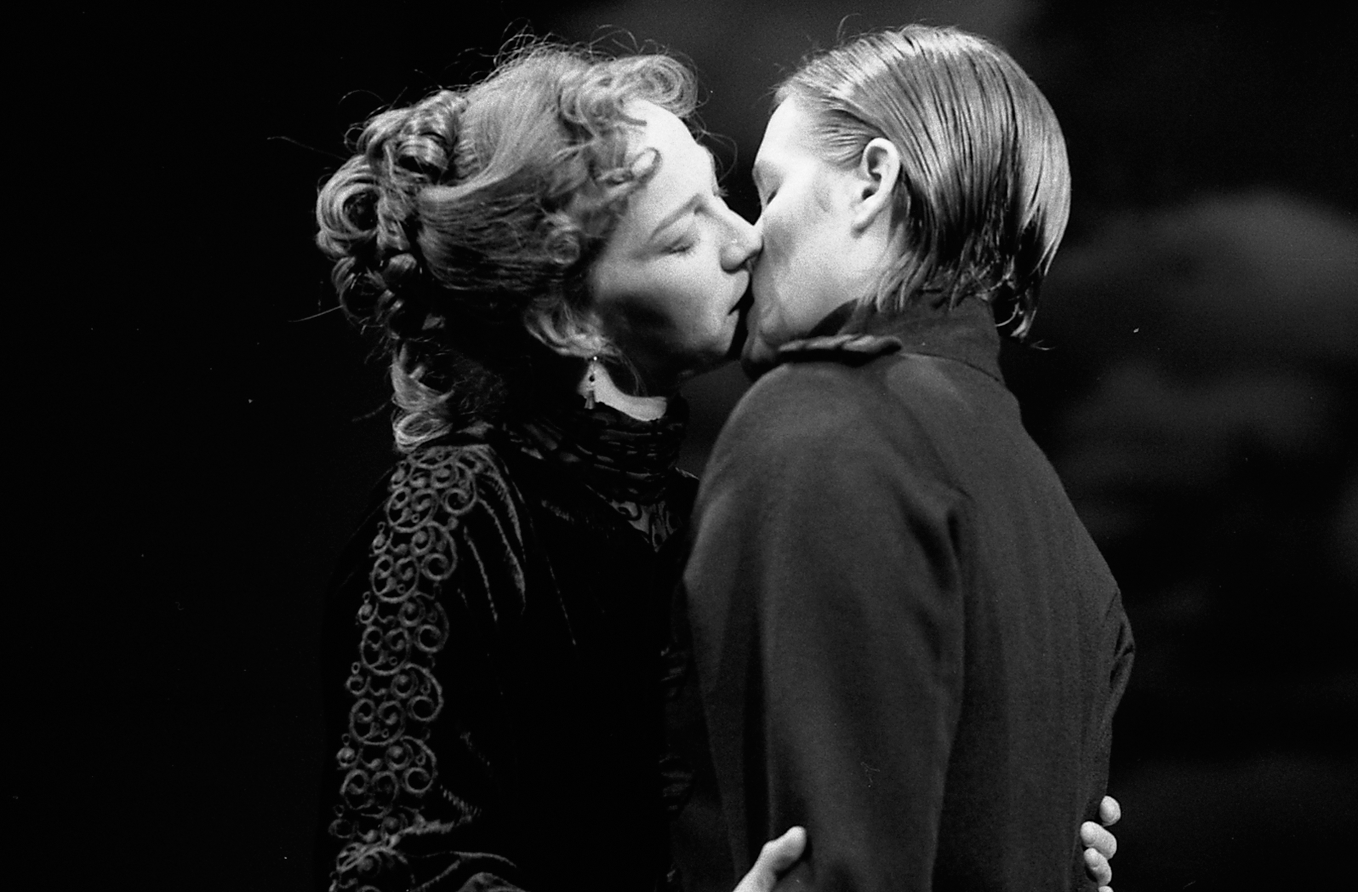

Barker came to Twelfth Night after a controversial production of The Winter’s Tale which had outraged many reviewers.Footnote 36 Barker’s Twelfth Night was better received but it still ruffled the feathers of the traditionalists. The production was fast moving, it only cut around twenty lines, and it used modernist sets as well as an Elizabethan style platform built over the orchestra pit. Most traditional comic business, particularly that associated with Toby, was abandoned, and in directing his then wife, Lillah McCarthy, as Viola (see Figure 4), Barker insisted on the role being played as a boy/girl not as a girl/boy. Both McCarthy’s Viola and her Cesario were gutsy – Cesario made a particularly good showing in the duel with Andrew beginning by imitating ‘almost everything [Andrew] does’ and soon ‘having gained courage, now fights with determination – strikes Andrew’s sword 1st time a direct blow – 2nd and 3rd reverse blows’ (pbk). As Dymkowski comments ‘the audience was left in no doubt about the likely victor if Antonio had not intervened’ (Dymkowski 55). McCarthy’s performance suggests a responsiveness to contemporary debates over women’s emancipation and their right to vote, issues aired in many plays directed, and indeed written, previously by Barker.

4 Lillah McCarthy in her ‘woman’s weeds’ as Viola at the end of Harley Granville Barker’s 1912 production.

Barker defended his direction of Viola in his preface to Twelfth Night stating that ‘Viola was played, and was meant to be played, by a boy’ (vi) and then lamenting that:

it is the common practice for actresses of Viola to seize every chance of reminding the audience that they are girls dressed up, to impress on one moreover, by childish by-play as to legs and petticoats or the absence of them, that this is the play’s supreme joke.

Barker maintains that, after 2.2, the Viola:

who does not do her best, as far as the passages with Olivia are concerned, to make us believe, as Olivia believes, that she is a man, shows, to my mind, a lack of imagination and is guilty of dramatic bad manners, knocking, for the sake of a little laughter, the whole of the play’s romantic plot on the head.

Barker also stresses that:

Shakespeare’s audience saw Cesario without effort as Orsino sees him; more importantly they saw him as Olivia sees him.

Lillah McCarthy as Viola certainly attempted to play this ‘mannish’ reading (160) and she recalls that during rehearsals

I must have stressed too much the poetry of the part, and by so doing let Viola betray the woman in her. The producer would not have it so. I must play the man – that is the youth that Viola pretends to be.

So McCarthy played the role ‘as a leading man, which the producer insists on’ (161).

Reviewers were divided in their reactions and even a supportive review, such as the Sketch (27 November 1912) was searching for womanliness:

The fact is she eschews deliberately the almost traditional humour of making fun of the equivocations due to her disguise. So much the better, for, in consequence, we have a truer and more womanly Cesario than before […] Moreover, she was mistakable as a youth.

Meanwhile the Athenaeum (23 November) thought this Viola ‘so lacking is a sense of fun that one wonders how she ever brought herself to dress up as a boy’, and The Illustrated London News (23 November) was put out by the fact that McCarthy ‘misses ever so many of the famous points in the heroine’s speeches’.

All this took place in an Illyria that was somewhere ‘Oriental’. In this production Viola’s marriage was clearly going to be interracial as Orsino wore a turban, lush clothes and a pointed beard; he had black turbaned servants, as did Olivia, while Antonio was extremely ‘Arabian Nights’ in appearance.Footnote 37 Although Norman Wilkinson, the designer, was aiming for clothes of ‘a particularly smart good cut of the Elizabethan type, combined with the romance of the Persian type of dressing’ (Evening News 12 November), nevertheless all the servants appeared African. The Daily Mail (16 November), baulked at Olivia’s garden, which it saw as ‘somewhat of a nightmare, with its pink baldachino over a golden throne, its Noah’s Ark trees, “box” hedges, and dead flat white sky’ and detected cubism at work; meanwhile the Referee (17 November) found post-impressionism.

Although Barker’s Twelfth Night broke with many longstanding comic traditions, it still saw Malvolio as securely comic. The Observer (17 November) vividly characterises Henry Ainley’s performance:

From the initial very quiet, utterly supercilious demeanour of the man-servant with a ‘swelled head,’ through the vulgarity that broke out in his supposed elevation down to the shame of his imprisonment in the dark room, and his final spit of rage against his tormentors, Mr. Ainley held the man together and made a single character of him.

And yet the promptbook clearly indicates that general laughter onstage was the response to both the explanation of the trick against Malvolio and to his vow of vengeance.

Something of the range of views on Malvolio at this time is indicated by a promptbook from shortly before Barker’s production, promptbook S72, which records two alternatives for Malvolio’s final exit: either ‘Malvolio at the end shaking his staff of office in good natured reproof & with a smile of forgiveness’ or ‘shaking with rage’ Malvolio tears off his chain and ‘with exaggerated dignity stalks off into house’. Although Irving’s Twelfth Night had been a critical and commercial failure, lead actors were now increasingly beginning to explore how far the play could be pushed in the direction of ‘the tragedy of Malvolio’, starting the move that by the late twentieth century would make uncomplicatedly comic Twelfth Nights a rarity, and Malvolio the star role.

In the early part of the twentieth century, however, much traditional comic business still remained in circulation and some routines proved enduringly popular, something which can be seen, for example, in the work of Robert Atkins. Atkins first performed in Twelfth Night for Herbert Beerbohm Tree but he went on to direct a frequently revived Twelfth Night at the Old Vic in 1920, and Atkins was still directing the play, and playing Toby, in 1959. Atkins did not simply recycle material and did occasionally break new ground: for example, he directed the 1927 curiosity performance of the ‘clan matinee’, a fundraising performance of Twelfth Night cast largely from the Forbes-Robertson family. The Viola of this performance, Jean Forbes-Robertson, later became famous for her performances as Peter Pan, and it was with this reputation that she returned to Viola for Atkins in the 1932 ‘black and white’ Twelfth Night. This production, performed in a ‘setting of black and white and silver’ (T 25 May), ran at the New Theatre, London, but it also, in ‘a commendable innovation’ braved the outdoor venue at Regent’s Park ‘for a few summer afternoons’ (T 14 July), and thus started the tradition of playing Shakespeare in that venue (Atkins 114). Forbes-Robertson was a ‘gravely boyish Viola’ (T 14 July), ‘wistful’ and ‘vocally and visually elegant’ (Atkins 114). But when Phyllis Neilson-Terry’s Olivia sang ‘Come away death’ ‘bending over her broideries’ (Punch 1 June), plus the last verse of Feste’s final song (Atkins 114), the production looked back to the singing Olivias of the eighteenth century. What is more, in his 1945 Stratford production, Atkins’s Toby was still performing the repeated ‘biz’ of 2.3 whereby ‘Sir T puffs at candle. Malv lifts it out of reach each time & brings it back’ (S94), business which again had its roots in eighteenth-century practice and the elaboration of Toby’s scenes with broad physical humour.

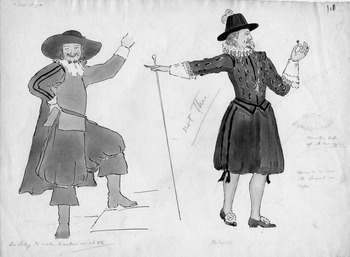

The commercial success of Atkins’s ‘black and white’ Twelfth Night, which was revived several years running came amidst something of a surfeit of Twelfth Nights in England, and certainly some London reviewers started complaining that they had had enough of the play. One seminal production, however, was that programmed for the gala reopening of the Sadler’s Wells theatre, on Twelfth Night, 1931, and directed by Harcourt Williams. This production was praised for its restraint, particularly in relation to traditional comic business and Ralph Richardson’s Toby was much commended for retaining his dignity and displaying the ‘uncommon virtue of remembering, even in his cups, that Toby is no pot-house brawler but Olivia’s kinsman’ (T 7 January). Many reviewers were disappointed with John Gielgud’s puritanical Malvolio, but when Williams decided to use a setting inspired by ‘Dutch pictures of the Puritan age’ (Williams 103) he established something of a fashion for a Cavaliers and Roundheads approach to the play, which became particularly popular with directors wanting to signal that the ‘cakes and ale’ philosophy of aristocrats like Toby would, only forty years after Twelfth Night was first performed, get short shrift from the New Model Army (see Figure 5).

5 Cavaliers and Roundheads costume design for Harcourt Williams’s 1931 Old Vic production.

Harcourt Williams’s Caroline Twelfth Night was revived in 1932, and although in the following year Tyrone Guthrie directed a completely new production of Twelfth Night at the Old Vic, Guthrie followed Williams’s lead in making the world of the play Caroline. Guthrie also ‘transposed’ the play to a ‘minor key’ (DM 19 September 1933) and Morland Graham played Feste as decrepit, aged and inspiring ‘curious pathos’ (News Chronicle 19 September). The biggest controversy arose over the casting of prima ballerina Lydia Lopokova as Olivia and the reviewers particularly objected to the fact that Lopokova’s Olivia made ‘violent love to Viola’ (News Chronicle 19 September), and ‘threw herself into a frenzy of passionate love-making’ (Star 19 September).Footnote 38 While Lopokova’s lively, energised Olivia would have been quite at home in many late-twentieth-century Twelfth Nights, the production also looked to the future in another way: Guthrie and the majority of his Twelfth Night cast were rehearsing The Cherry Orchard as they performed Twelfth Night, a creative juxtaposition which bore fruit in Guthrie’s next production of Twelfth Night in 1937. This production turned out to be the first in a very long line of Twelfth Nights labelled ‘Chekhovian’ (see pp. 38–40), although some thought it merely ‘morose’ (G 24 February). John Abbott’s Malvolio was ‘a young, attractive man whose feeling for Olivia is something deeper than mere social ambition’ (DTel 24 February). When this ‘calmly officious’ Malvolio was pitched against Marius Goring’s Feste, who was ‘always suggesting the verge of actual madness’, then ‘the often-boring prison-scene’ became ‘a thing of fierce, tragic-comic intensity, with something of a Chekhovian irony’ (Morning Post 24 February). Meanwhile Laurence Olivier’s scene-stealing comic antics as Toby were particularly remarked upon, even though he went overboard with make-up, prosthetics, and whiskers which affected his audibility.Footnote 39 This Toby indulged in ‘a superabundance of comical crawling, stumbling, and staggering’ (G 24 February), although the Telegraph (24 February) savoured the moment when, as Olivia rebukes him, Olivier’s Toby ‘cocks an eye just like a sky terrier who knows himself in disgrace but hopes shortly to wheedle his way back to his lady’s favour’. Alec Guinness played Andrew to Olivier’s Toby and reminded the Daily Mail (24 February) of Stan Laurel.

In view of the fact that Guthrie started a fashion for so-called Chekhovian Twelfth Nights, it seems ironic that the productions of the play directed by Michael Chekhov were so completely antipathetic to the stereotypical meaning of the adjective ‘Chekhovian’ in Anglophone culture.Footnote 40 Indeed Michael Chekhov’s Twelfth Night for the Habima Players, which premiered in Berlin before touring extensively, was thought to be far too much of a ‘joyous and swiftly moving farce’, unShakespearean and too close to ‘pantomime […] ballet and circus’ (T 7 January 1931). Feste became Harlequin, Olivia was ‘a ninny’, ‘Maria broke frequently into song and everybody danced in pink and yellow clothes’ and the whole experience was a kind of ‘sublimated circus’ performed by ‘super-acrobats and conjurers’ (ES 7 January). Clifford Leech records that Chekhov directed Malvolio as ‘a corpulent buffoon who is made ultimately to see the joke against himself and is persuaded to join Sir Toby and Sir Andrew in throwing paper-darts among the audience’ (Leech 37). Reviews of Michael Chekhov’s later US production, in 1941, also indicate an enthusiastic use of slapstick with an emphasis on ‘Russian horse-play’, ‘excessive makeup’ and ‘false beard and falser noses’ (New York Sun 3 December). The New York Post (3 December) also commented on the ‘prodigious amount of duelling’ and the decision to play Orsino as ‘waited on by tottering octogenarians apparently in the last stages of senile decay’. The World-Telegram (3 December) pronounced the production ‘a heavy handed romp’.

During this period British reviewers continued to search for the woman-beneath-the-boy in Cesario: Dorothy Green’s Viola, under Harcourt Williams’s direction in 1931, was ‘delightful’ because ‘the woman is ever present in the boy’ (T 7 January) but Dorothy Massingham, playing Viola in a revival of W. Bridges-Adams’s production, was disappointing because ‘her assumed boyishness does tend to hide the woman underneath’ (SUAH 26 July 1929). Valerie Tudor, in a revival of Ben Iden Payne’s 1936 Twelfth Night, was applauded for hinting ‘at the woman behind the disguise’ (BP 16 April 1938) and the Birmingham Mail compared Tudor with ‘Vesta Tilley in her heyday’ (16 April 1938).

More deliberately provocative Twelfth Nights, designed to shake up old certainties, also appeared. In 1933 reviewers were mostly stunned by Terence Gray’s production of Twelfth Night at the Festival Theatre Cambridge, a production in which Commedia was the dominant influence, performers wore masks and ‘danced and postured’, while Toby appeared ‘on roller skates in one scene’ and ‘Elizabethan pronunciation’ was used for 1.5 but for no other scenes (Cambridge Daily News 16 May).Footnote 41 In December 1933 the Evening News (21 December) was reporting that the Moscow Art Theatre was to mount the play as a challenge to ‘sanctimonious bourgeois prudery’, although in reviewing the actual production in 1934, the Guardian (25 September) thought the play was ‘treated like “The Marriage of Figaro”’, with an overlay of criticism of ‘the “decadent” social conditions’ of Shakespeare’s time as Feudalism moved into Capitalism. Then in 1939, the first woman to direct at Stratford, Irene Hentschel, produced a Twelfth Night which was lively and eclectic, which ‘shrieks at the conventions, flouts all the traditions’ (BM 13 April), and was grounded in the nineteenth century. Olivia was an Alice in Wonderland figure with long blonde hair down her back and looking, as Hentschel’s husband, the reviewer Ivor Brown, commented, straight out of Tenniel’s illustrations (Observer 16 April). Meanwhile Joyce Bland’s Viola, ‘straight-limbed’ and ‘boyishly brisk’ found Olivia round her neck ‘at almost the first encounter’ (BM 13 April). John Laurie’s Malvolio was Dickensian but while the Birmingham Gazette (13 April) detected Scrooge, The Times (14 April) thought of Pickwick Papers, and the News Chronicle (14 April) saw ‘a cross between the melancholy waiter in “David Copperfield” and a Spy cartoon of a very sick Disraeli’. Meanwhile Illyria, designed by the three-woman team of Motley, was dominated by black Victorian wrought iron, although Orsino was Byronic, and Toby Edwardian. Hentschel’s decision to use an eclectic nineteenth-century context for the play has had many followers since, and, although clichés get circulated – picturesque but cumbersome costumes, adherence to strict etiquette, sexual prudery and an enthusiasm for a cult of mourning – nevertheless a nineteenth-century milieu has proved resonant for many directors.Footnote 42

This period also saw new directions for Twelfth Night in North America and is particularly notable for striking responses to the play by women. In 1926 Eva Le Gallienne directed Twelfth Night, and starred as Viola, in a production which was ‘definitely fantastic’, and which used puppet-like wigs and make-up for all characters except for Olivia (NYT 21 December). Le Galliene herself, as Cesario, wore ‘a yellow rope wig’ with clearly marked-out curls, and she had doll-like red circles of rouge on her cheeks.Footnote 43 Le Gallienne cut 4.2 (S85), treated Olivia with sympathy, and served up the play as a Christmas entertainment. Jane Cowl also placed her stamp on the play when she took the part of Viola in Andrew Leigh’s 1930 production. Cowl’s Viola was ‘glamorously romantic, though lacking in mischief’ (DTel 13 November) but Cowl was also responsible for this production’s staging conceit: that the different scenes of the play should be played as emerging from the turning pages of an enormous book (New York Herald Tribune 26 October), while Feste ‘turns the pages to the settings corresponding to the action’ (Boston Evening Transcript 9 September). This concept clearly appealed to Orson Welles who used a very similar device in the production of Twelfth Night he worked on in association with Roger Hill for the 1932 Chicago Drama Festival Competition.Footnote 44 Welles and Hill published an edition of Twelfth Night based on the work they did for this all male Todd Troopers production, an edition embellished by Welles’s sketches, and Welles’s introductory essay indicates that ‘the prompt-books of the great actors’ have been consulted, although ‘Our business has been with the more respectful actors’ versions’ (Welles, Introduction, 28). The edition includes the text of the imaginative framework which includes Shakespeare talking to his fellow actors about his work and warning Richard Burbage to beware of the Malvolios of the world and their anti-theatricality (Welles, Prologue, 7).

The most commercially successful Twelfth Night in the US in this period was Margaret Webster’s 1940 production which ran for 128 nights on Broadway. Maurice Evans played Malvolio ‘as a commoner of humble beginnings desperately trying to be even more genteel than his masters’, but betrayed by his cockney accent (Evans 144). The New York Herald Tribune (21 November) thought his ‘efforts to get all the h’s in their right place’ all ‘add to the humanity of the unfortunate man’. Helen Hayes was a ‘brisk, boyish, loveable Viola’ (New World-Telegram 20 November). Webster herself was dissatisfied with the production: ‘It was gay, decorative, witty in a slightly sophisticated way, but seldom funny from the heart; charming and even occasionally touching, but lacking in shadows or in depth’. She cut the ‘footnote jokes’ (Webster 97) as much as possible and ‘stole a piece of business from Michael Chekhov’s production for the Habima Players’ (98) whereby in 2.5, the letter scene, Toby, Fabian and Andrew ‘carried round with them little, toy, potted trees which they would plant down in front of themselves as a ludicrous sort of concealment’.Footnote 45 Webster concludes ‘Twelfth Night is one of the most difficult plays in the whole canon to do really well. Yet everybody does it; everybody thinks it’s easy’ (Webster 98).

Illyria

After the Second World War it does seem as if, as Webster put it, ‘everybody’ was doing Twelfth Night and productions significantly increased in number and in diversity. While certain crucial issues get raised over and over again, particularly issues of tone, mood, identity politics and sexuality, what is critical in considering any of these issues is the question of location, where and when a director decides to situate Illyria, and how festive, permissive or repressive that location seems to be. While a director’s decision about the setting for any Shakespeare play in production has significant consequences aesthetically and politically, Illyria has often been a very forceful presence in productions of Twelfth Night, creating a significant impact on mood, tone and characterisation. Directors have placed Illyria in many different locations, time zones, and historical periods, and the location, and relocation, of Twelfth Night has often helped determine whether a production will tip in the direction of holiday spirits or in the direction of gloom. In addition the creation and realisation of many Illyrias onstage has been used to underscore the individual director’s approach to the insider/outsider, privileged/ marginalised dynamics in the play.

Geographical Illyria, the modern Albania, Macedonia and Bosnia, was very popular in nineteenth-century productions but, as Furness (4) points out, because in Shakespeare’s period ‘Dalmatia was under the rule of the Venetian republic’, many nineteenth-century productions rendered the play ‘a romantic and poetic picture of Venetian manners in the seventeenth century’ with occasional use of ‘Greek dresses’. Illyria for Shakespeare also had piratical associations and this is presumably why Antonio is sometimes, despite his protestations in 5.1, costumed as a local pirate:Footnote 46 so Alastair Sim, in Harcourt Williams’s 1932 production, turned Antonio ‘into one of the comic pirates out of “Peter Pan”’ (DTel 30 March) and in Hugh Hunt’s 1946 Twelfth Night Antonio sported a tremendous piratical costume complete with enormous earring.Footnote 47

Later twentieth-century attempts to evoke the geographical Illyria often trade in modern clichés about the eastern Mediterranean region: in 1973 Toby Robertson made Illyria ‘Yugoslavia in the 19th century’, with music provided by ‘peasants in traditional Yugoslav garb’ (or at least what English audiences would read as such), a Malvolio who appeared to be ‘a turbaned and droopily moustachioed Turk’, and a priest who ‘looks like Archbishop Makarios’ (DTel 6 September). Wilford Leach in 1986 produced an Illyria that was Albanian to the New York Post (3 July) but ‘Tatar-Cossack’ to the New York Times (3 July), although the latter also thought that ‘[s]ome of the actors look as if they are outfitted for a bus and truck tour of “Kismet”’. Larry Lillo in 1985 made Illyria ‘Ruritanian’, and included a Scots-accented Andrew who sported ‘Middle Eastern tailoring’, Turkish slippers and ‘a violet fez’ (GM 29 January). In 1986 Nancy Meckler’s production was ‘of vaguely Balkan provenance’ (O 5 October); Bill Alexander, in 1987, settled on a holiday brochure view of Greece with clusters of picturesque white houses; and Raymond Omodei, in 1988, staged a vision of ‘café-Albania’ (West Australian 5 March) with a Toby dressed as a ‘Balkan bandit’ (The Australian 9 March). Geographical Illyrias have occasionally come freighted with a political loading: for example, in 1983, Nicolas Kent evoked Illyria when it was ‘part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, prior to the Great War’, thereby suggesting a world about to change irrevocably.Footnote 48 Meanwhile Cecil Mackinnon, in 1991, evoked an element of ‘Illyria vs Islam’ although this production also dealt in clichés and had Olivia ‘overseeing a harem’ (Boston Globe 31 July).

Given the popularity of Illyrias of Eastern European provenance, it is not surprising that some directors have gone slightly further eastwards and indulged in exoticism and orientalism. Perhaps the most influential, modern vision of Illyria as an orientalist fantasy appeared in Ariane Mnouchkine’s 1982 production of Twelfth Night (La Nuit des Rois) which brought Kathakali, Kabuki and visually splendid theatricality to Illyria.Footnote 49 Brian Singleton describes Mnouchkine’s production as a ‘transdaption’ (Singleton, 1993, 115), which had Feste ‘dressed as an ankle-belled Indian dancer who invoked merriment on stage with his athletic tumbling, and his charismatic power over Sir Toby and Sir Andrew Aguecheek’ (113). Meanwhile Orsino was ‘the personification of sadness’ with ‘an enormous handkerchief and tears painted permanently on his face’ and always accompanied by ‘the tune of an Indian tampura’ (115). The video record of this production indicates that Orsino was so ridiculous, with his wailing theme music and indulgent posturing, that the audience laughed at him every time he appeared; by contrast characters such as Olivia, Antonio and Malvolio became possessed by a more frenzied desire, dancing wildly round the stage when struck by passion. Mnouchkine staged the whole play as ‘a confrontation of the … European Christian with the mystical and mischievous spirit of the East’ and Malvolio was ‘soberly dressed in Calvinist black’ a ‘killjoy and puritan’ (Singleton, 1993, 113). Costumes were ‘doublets and baggy trousers gathered at the ankle’ which managed to evoke ‘exotic, oriental luxury’ as well as the early modern (Kiernander 117). Music, as often with Mnouchkine, played throughout the production, inflecting the audience’s mood and sense of locality, and creating theme music for most of the characters; the production was a visual feast with gorgeous costumes, and huge decorated umbrellas borne by servants attending on the aristocrats.Footnote 50

Some modern productions have signalled Illyria as exotic by the deployment of race markers, especially blackness, in relation to court servants: for example, production photographs show that Michael Benthall’s 1958 Twelfth Night had a blacked-up servant, wearing a white turban and carrying a black fringed umbrella to keep Olivia in the shade. Ian Holm played a black drummer boy in John Gielgud’s 1955 production set in a ‘Persian court as an Italian old master might have imagined it’ (G 15 April). Slightly less loaded, if still conventional, orientalism appeared in Philip Minor’s 1978 production which had ‘Ali Baban costumes’ (The Real Paper 22 July). Nicholas Hytner, in 1998, had a set inspired by ‘Oriental carpets’ and ‘an Indian manuscript’, while Orsino lived ‘in an extraordinary kind of Buddhist temple’, the whole adding up to ‘an Oriental fantasy of the mind’ which required an environmentally challenging 10,000 gallons of water onstage every night (NYT 28 July). One reviewer thought this Illyria ‘straight out of The Arabian Nights’ (FT 17 July), another that it offered a mix of ‘Iberia and India, locating Illyria around Portuguese Goa’ (T 21 July). But in 1991 Virginia Boyle sent up the whole idea of Orientalism and had great fun with it at the same time: the audience were served Turkish delight during the interval and the combination of ‘Palm trees, genie costumes and voluptuous squealing belly dancers’ suggested ‘an exotic Arabian Nights fantasy’ (Tharunka 18 March).

Amidst such exoticism, the Englishness of some characters, especially Toby, can seem incongruous.Footnote 51 In 1978, Michael Elliott coped with this by evoking an Illyria ‘East of Suez’ (Stage 19 January 1978), and stereotypes of the British abroad. Similarly Denise Coffey, in 1983, placed Illyria ‘East of Suez’ in a land ‘occupied by British troops in Khaki and topees’, and permeated by strong elements of ‘a P. G. Wodehouse tea-dance’ (DTel 15 October). A popular variant on this combination of orientalism and the joke of the British abroad is the relocation of Illyria to India under the British Empire: for example, Michael Kahn, in 1989, placed the action in ‘a Last Days of the Raj outpost of English colonialism’ where Toby and Andrew became ‘idle Edwardian boors, pickled in Gordon’s Gin and armed with golf clubs’ (NYT 4 October). The Twelfth Night directed by Leon Rubin in 2006 at Stratford Ontario also had Illyria as India under the Raj; it was colourful and energetic, but several Anglo-Canadian performers had to apply make-up in order to play the Indianised characters. A very Indian Illyria appeared in Cliff Burnett’s 1991 Twelfth Night, with a huge Hindu deity dominating the stage, and Kaleem Janjua as a ‘puritanical and priggish’ Malvolio (Scotsman 9 February). Stephen Beresford’s 2004 West End Twelfth Night had an entirely Indian cast, and played to London audiences’ expectations of Indianness: this had the effect of emphasising caste, as well as mourning and courtship rituals. While most reviewers enjoyed the relocation, many felt Beresford could have taken things much further: for example, the Herald (1 September) felt the result was ‘a fairly conventional, charmingly innocent English reading, mildly coated in Asian flavours and sweetly acted’ although one performance that did go further was Kulvinder Ghir’s Feste. Performed in the tradition of a Baul singer, and including cross-dressed, mock Bollywood dance routines, this Feste was comic and threatening, and always an outsider.