Introduction

The early life of calves displays a critical period. At birth, the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of calves is not yet mature, and the rumen is non-functional (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021). From the beginning, it is largely influenced by microorganisms, which are therefore essential for the development, differentiation and function of the immune system and mucous membranes (Alipour et al. Reference Alipour, Jalanka and Pessa-Morikawa2018) and in addition that protect the host from invasive pathogens (Kamada et al. Reference Kamada, Chen and Inohara2013). The rumen microbiome is formed directly at and after birth, with the first microbial transmission from mother to offspring starting through contact with faecal material, the vaginal canal, saliva, skin and colostrum of the dam and continues during lactation and later life (Alipour et al. Reference Alipour, Jalanka and Pessa-Morikawa2018; Meale et al. Reference Meale, Chaucheyras-Durand and Berends2017; Palmonari et al. Reference Palmonari, Federiconi and Formigoni2024). Guzman et al. (Reference Guzman, Bereza-Malcolm and Groef2015) discovered that shortly after birth, there were some methanogens, fibrolytic bacteria and Proteobacteria present in the calves’ GIT and faeces, meaning that the GIT is colonized by microorganisms as soon as the animal is born, or even before it. Whilst the GIT is developing, also the gut microbiome changes gradually in calves (Du et al. Reference Du, Gao and Hu2023). Especially in the first days, there are some rapid differentiations occurring (Meale et al. Reference Meale, Chaucheyras-Durand and Berends2017). During weaning, there is a shift towards an adult-like microbiome (Dill-McFarland et al. Reference Dill-Mcfarland, Breaker and Suen2017), including increasing abundances of bacteria such as Ruminococcus, Bacteroides and Lachnospiraceae (Shanks et al. Reference Shanks, Kelty and Archibeque2011). Besides its role in digestion, the microbiome influences phenotypic traits such as feed efficiency, methane emission and disease status (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Bian and Teng2020). There is interest in determining whether there is a host genetic control defining the microbial composition (Gonzalez-Recio et al. Reference Gonzalez-Recio, Zubiria and García-Rodríguez2018) and if it is possible that some key modulators are determining the specificity between host and microbe (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Bian and Teng2020). Microbiome differences were identified between Italian Holstein and Italian Simmental breeds by Sandri et al. (Reference Sandri, Licastro and Dal Monego2018). These are most likely contributed to by breed-specific variations in metabolic adaptation and immune response.

Since calves have an underdeveloped reticulorumen, the milk flows directly into the abomasum (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Weary and von Keyserlingk2011). Bovine milk contains different types of casein, which are known for exhibiting antihypertensive, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, antioxidative and opioid-like peptides (Hohmann et al. Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021). The most common β-caseins are A1, A2 and B (Ben Farhat et al. Reference Ben Farhat, Selmi and Toth2025; Kappes et al. Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024). There is an ongoing debate about the health-impairing effects of the A1 allele of β-casein compared with the progenitor A2 allele. They differ in the amino acid position 67, in A1 milk it’s a histidine and in A2 milk a proline. Enzymatic digestion therefore yields the opioid β-casomorphin-7 for A1 (Hohmann et al. Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021), which is a peptide that is not digested in the human body. It activates µ-opioid receptors and increases the risk for type-1 diabetes, for example, but also neurological and digestive disorders (Jianqin et al. Reference Jianqin, Leiming and Lu2016; Kullenberg de Guadry et al. Reference Kullenberg de Guadry, Lohner and Schmucker2019). With A2-β-casein, enzymatic hydrolysis between Ile66 and Pro67 occurs in lower amounts, minimizing the release of β-casomorphin-7, which might have some advantages in the development of pre-weaned calves (Hohmann et al. Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021). Song et al. (Reference Song, Kim and Choi2025) detected in a human trial a significant shift in the composition of the gut microbiota after consuming A2 milk (p = 0.04), which was not detected after consuming A1/A2 milk. After milk consumption, significant differences were detected in the gut microbiota composition between A1/A2 and A2 milk drinkers (p = 0.031). The alpha diversity remained unchanged. In the A2 group, they highlighted enriched transport systems, which are related to energy, sugars, peptides and raffinose family oligosaccharides. Exclusively in the A2 group, significant associations between Blautia, Bifidobacterium and enhanced transport systems were observed. In mice, several studies demonstrated enhanced SCFA concentration when feeding A2 milk. They suggested positive impacts of milk, especially when containing exclusively A2 beta-casein. Beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillaceae, were detected with a higher abundance when feeding A2 milk to mice (Guantario et al. Reference Guantario, Giribaldi and Devirgiliis2020; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Qiao and Zhang2022; Nuomin et al. Reference Nuomin, Baek and Tsuruta2023).

The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of feeding homozygous A1- and A2-β-casein milk and the influence of breed on the composition of the oral and rumen microbiota of calves at different ages. Buccal swabs were used to collect saliva from calves at an early age, replacing traditional invasive methods such as rumen cannulation or rumenocentesis. Besides being stressful for animals, those methods also are very impractical for large-scale trials with many animals (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021).

Material and methods

Management and diet of the animals

Management and feeding of the calves were previously described by Kappes et al. (Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024). Calves (n = 104) of the breed groups German Holstein (≥80% German Holstein = GH), German Simmental (≥80% German Simmental = GS) and German Holstein x German Simmental crossbreds (20.1–79.9% GH = CR) were housed at the Livestock Center Oberschleissheim, Veterinary Faculty of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich, from September 2022 to June 2023. The calves were randomly assigned to one of two different feeding groups according to their birth order, with the group being changed after every second calf born and not balanced according to sex and breed. The first feeding group received an A1 milk diet with homozygous β-CN genotype A1A1 (49 calves), and group two received an A2 milk diet with homozygous β-CN genotype A2A2 (50 calves). Animals had the following breed distributions: 60 calves had the breed GS, 14 calves had 20.1–79.9% GH and 25 animals had 80–100% GH. To determine the body weight, every calf was weighed after birth and got ear tags for identification. They were housed individually in calf pens and received maternal colostrum ad libitum for the first 24 hours. After that, the calves were housed in pairs in a double igloo system and had ad libitum access to water and hay, but no access to calf starter. The intake of hay in the first 2 weeks of life was not considered, as the amounts were too small. They received either ![]() $\beta $-casein A1 or A2 milk three times per day at 06:00 (3 L), 11:30 (1.5 L) and 17:30 (3 L). The daily energy-corrected milk intake, based on fat and protein content, had to be calculated as the nutrient content of diets between the two treatments was not balanced. Faecal scores and cases of diarrhoea were documented daily. On day 15, the calves were weighed to determine their final body weight, average daily weight gain and body weight gain. From approximately 20 days of age onward, the calves were housed in larger groups and started receiving milk replacer and concentrate. For microbiota analyses, saliva samples of 99 calves could be used, which were taken with swabs (Salivette®, Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) three times during the experiment (mainly on the days 6, 15 and 27 after birth) as described in Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021). Swabs soaked with saliva were immediately frozen at −80°C, without an additional centrifugation step, until further processing.

$\beta $-casein A1 or A2 milk three times per day at 06:00 (3 L), 11:30 (1.5 L) and 17:30 (3 L). The daily energy-corrected milk intake, based on fat and protein content, had to be calculated as the nutrient content of diets between the two treatments was not balanced. Faecal scores and cases of diarrhoea were documented daily. On day 15, the calves were weighed to determine their final body weight, average daily weight gain and body weight gain. From approximately 20 days of age onward, the calves were housed in larger groups and started receiving milk replacer and concentrate. For microbiota analyses, saliva samples of 99 calves could be used, which were taken with swabs (Salivette®, Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) three times during the experiment (mainly on the days 6, 15 and 27 after birth) as described in Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021). Swabs soaked with saliva were immediately frozen at −80°C, without an additional centrifugation step, until further processing.

Sample preparation

DNA extraction

Bacterial cells were washed from buccal swabs, adding 4 mL PBS to each swab and incubating in the fridge at 4°C for 1 hour. This was followed by 30 seconds of sonication. Afterwards, the liquid was squeezed with sterilized forceps. Extracted samples were centrifuged at 2500× g for 10 minutes. After transferring the supernatant to two clean tubes, the samples were again centrifuged at 19.000× g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was discarded until 450 μL remained in the tubes. In the following, the pellet was resuspended and stored at 4°C.

DNA was extracted from the cell suspension using the FastDNATM SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio, USA). The liquid samples were sonicated for 15 seconds and subsequently added to Lysing Matrix E tubes. The following extraction was performed with slight modifications as described by Burbach et al. (Reference Burbach, Seifert and Pieper2016). For ensuring an effective cell lysis, a bead-beating procedure was included in the process. After determining the DNA concentration with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), the DNA was stored at −20°C.

PCR amplification and Illumina amplicon sequencing

For amplification of the V1-V2 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, two polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed as described by Kaewtapee et al. (Reference Kaewtapee, Burbach and Tomforde2017) and Deusch et al. (Reference Deusch, Camarinha-Silva and Conrad2017). Amplicon libraries were purified and normalized with the SequalPrepTM Normalization Plate (96) Kit (Applied Biosystems, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, California, USA) and sent to Novogene (Munich, Germany) for sequence analyses using the MiSeq platform.

Bioinformatic analysis

The bioinformatic analysis of the Illumina sequencing datasets was conducted using Qiime2 (2024.5) (Bolyen et al. Reference Bolyen, Rideout and Dillon2019). For importing raw data, the type SampleData[PairedEndSequencesWithQuality] was applied. Demultiplexing of sequences was performed using cutadapt (Martin Reference Martin2011), applying the same primer sequences as used during PCR and sequencing: forward primer CAAGRGTTHGATYMTGGCTCAG and reverse primer TGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT. Residual artificial sequences were trimmed by using the cutadapt trim-paired command and q2-cutadapt plugin (Martin Reference Martin2011). Subsequent quality filtration has been performed with the DADA2 in Qiime2 via a dada2 plugin and the denoise-paired command (Callahan et al. Reference Callahan, McMurdie and Rosen2016). Feature filtering was applied to retain only those features that occurred at least 10 times across all samples and were present in a minimum of three samples. The data were stored in a feature table and the taxonomy assignment was performed with the Genome Taxonomy Database (Parks et al. Reference Parks, Chuvochina and Chaumeil2020). In a second filtering for removal of unwanted features, sequences assigned to mitochondria, chloroplasts and cyanobacteria were excluded. Features without assignment at the phylum level also were removed. Low-read samples (<10,428 reads) were removed from the feature table as well. In the end, the biom feature table was exported and converted to a tsv format. Subsequently, the data were filtered. The filtering approach is documented in chapter 2.4. The following analysis was performed in R version 2024.12.1 (RStudio Team 2024) and the use of ANCOMBC2 (2.8.0) (Lin and Peddada Reference Lin and Peddada2024). A linear mixed-effects model was applied using the lmer function from the lme4 package (1.1.36) (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). The data were filtered to separate oral-associated bacteria from rumen-associated bacteria. The filtering approach was based on comparisons to filtered bacteria in the publications from Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021) and Kittelmann et al. (Reference Kittelmann, Kirk and Jonker2015).

Statistical analysis

Prior to statistical analysis, the count data were standardized by calculating relative abundances by dividing the counts of each amplicon sequence variant (ASV) by the total counts in each sample and multiplying by 100. With vegan (2.6–10), the Shannon diversity index was calculated to assess the alpha-diversity. The Kruskal–Wallis test together with the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) procedure was performed. For significant results, Wilcoxon test followed by BH was conducted for pairwise comparisons. Principal coordinate analysis plots were generated on the ASV level based on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Bar charts of relative abundances were created using the package ggplot2 (Wickham Reference Wickham2016) in R. All genera with relative abundances smaller than 1% were grouped in “Others < 1%.”

The ANCOM-BC2 (2.8.0) methodology was used for further analysis. In the calculations with ANCOM-BC2, prv_cut was set to 0.1, lib_cut to 50 and s0_perc to 0.05. Absolute abundances were used.

Afterwards, the data were log-transformed with the natural logarithm, on which the following analyses were performed. It was tested whether there are ASVs with significant changes between the effects considered and their interactions. After running an analysis of variance (ANOVA), the BH procedure was performed. For significant results again, the Wilcoxon test and BH were conducted. The effects of age, breed and the milk fed were implemented as fixed effects. Factors considered in this study are the age, the type of milk fed to the calves, either β-casein A1 or A2 and increasing percentages of the breed GH.

Results

Amplicon sequencing of 279 buccal swab samples revealed 5,421 ASVs. Taxa associated with the oral microbiota were separated and treated separately from the rumen bacterial taxa, resulting in a total of 21.56% oral-associated ASVs vs. 78.44% rumen-associated ASVs. The ASVs belonging to rumen-associated bacteria increased with increasing age: 1,878; 2,408; 3,784 ASVs were sequenced on days 6, 15 and 27 (Supplementary Table S1), respectively, whereas ASVs associated with the oral microbiota increased only slightly: 868; 929; 992 ASVs at days 6, 15 and 27, respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

Impact of the age

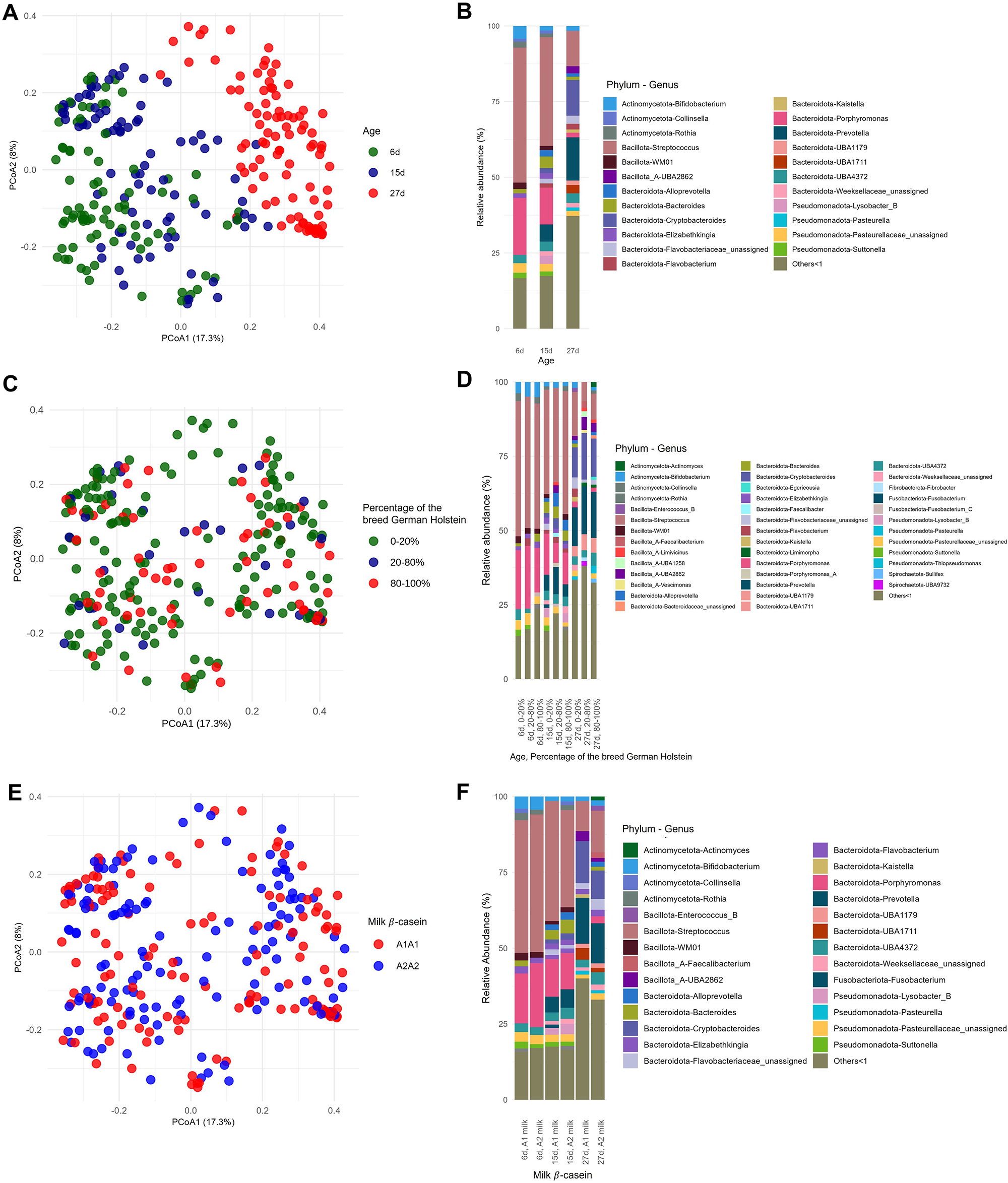

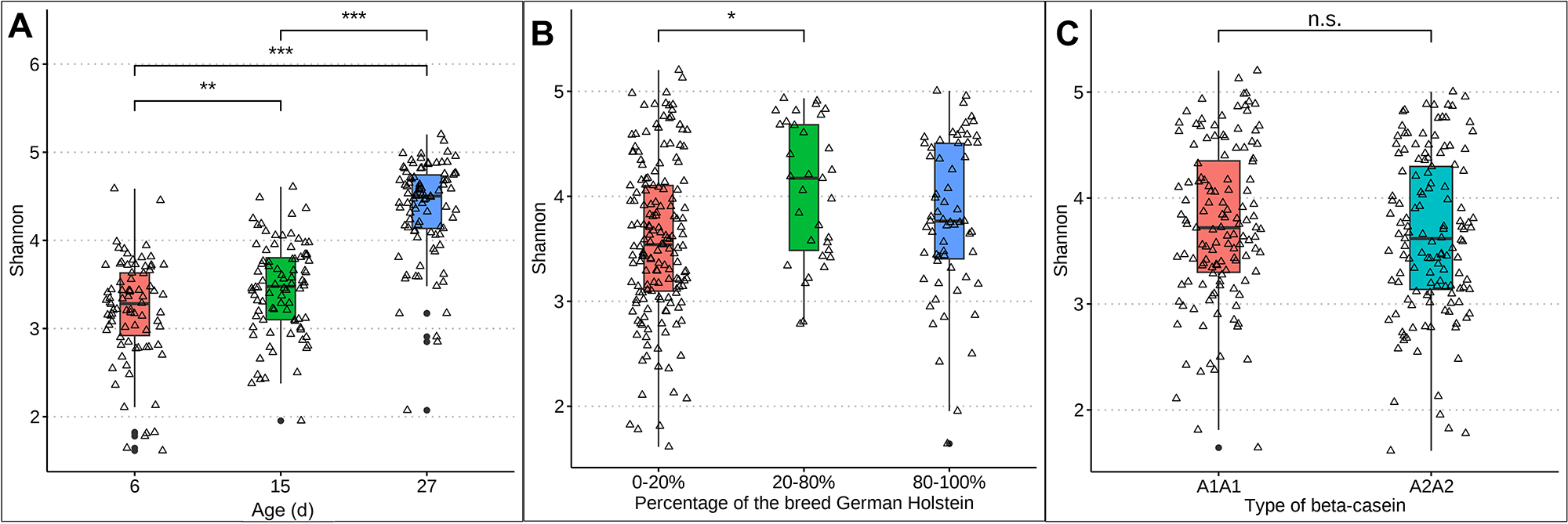

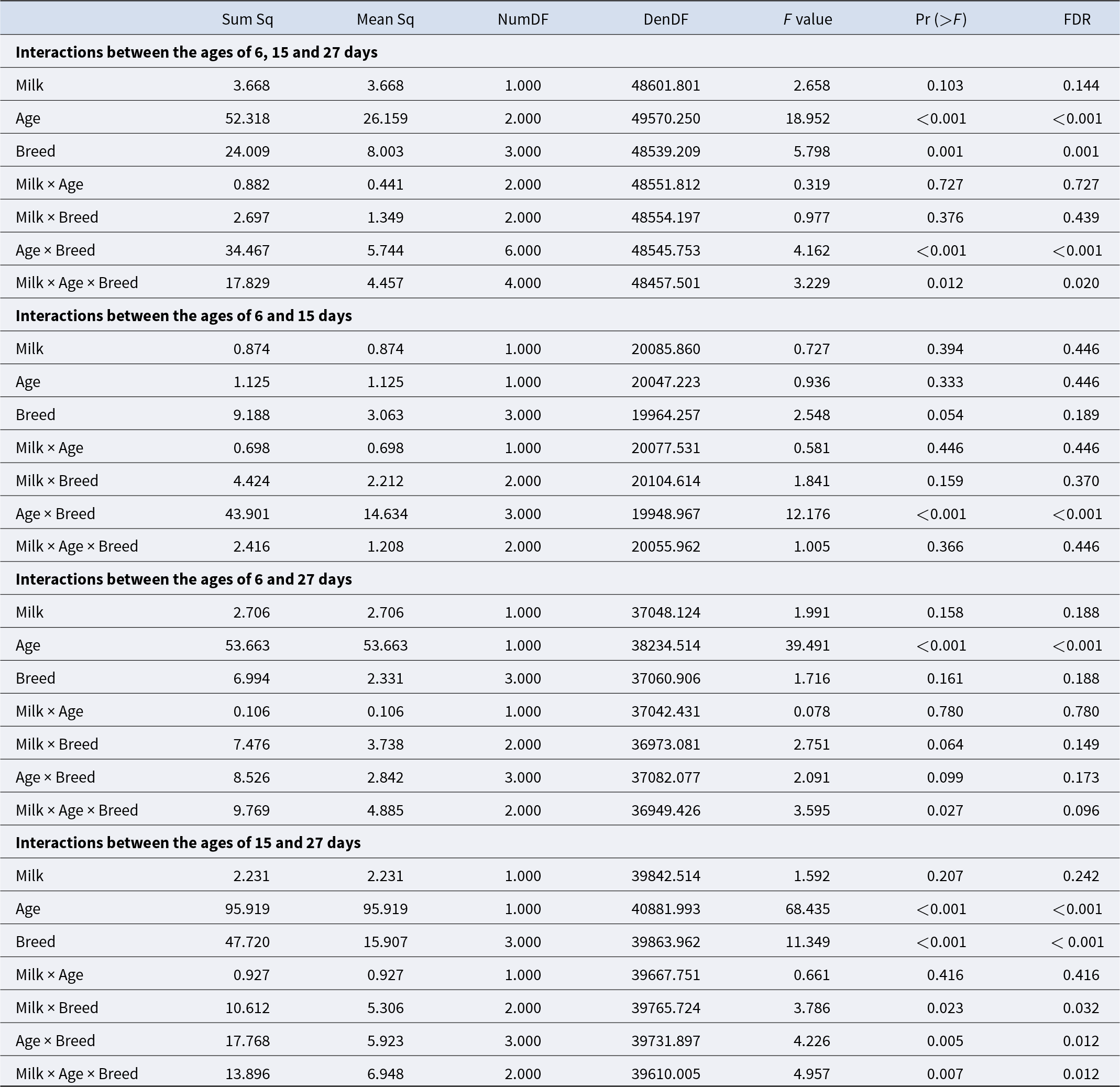

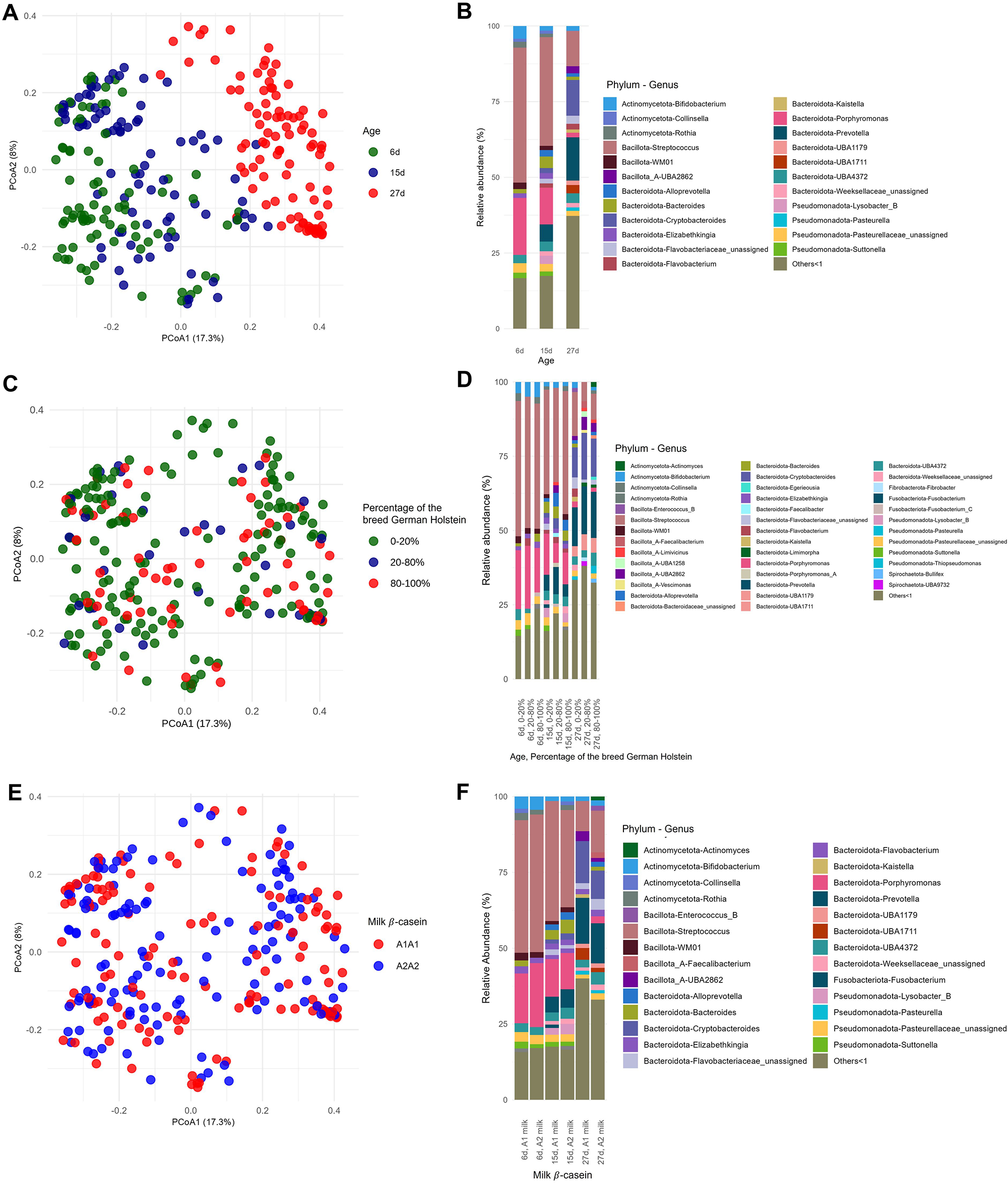

Differences in rumen-associated bacteria between samples collected from calves at day 6, 15 and 27 days of life are shown on the ASV level in Figure 1. Samples from day 6 clustered significantly differently (p = 0.0021) from samples taken at day 15. Samples from calves of the age of 27 days are clearly separated and almost no samples overlap with those taken at 6 days of age (p < 0.001) or 15 days (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). The Shannon diversity was significantly different between the age of 6 and 15 days (p = 0.006), 6 and 27 days (p ≤ 0.01) and 15 and 27 days (p ≤ 0.01) increasing in mean from 3.28 at day 6 to 4.50 at day 27 (Fig. 2A). The distribution of the oral-associated bacteria showed two clusters (Supplementary Figure S1A), one including samples collected at the age of 6 and 15 days (p = 0.28), another one with samples collected at day 27 (p = 0.007). The Shannon diversity values were similar at day 6 and 15, with an average of 2.24 but increased significantly (p < 0.0001) on day 27 to 3.31 (Supplementary Figure S2A).

Figure 1. Distribution of the rumen-associated bacteria according to their beta-diversity based on ASV level (A, C, E) and the relative abundance of the identified taxa at the three different time points (B, D, F). All genera with lower relative abundances than 1% are summarized in “Others < 1.” A and B, Changes with respect to sampling time points 6, 15 and 27 days. C and D, Changes regarding the percentages of the breed German Holstein in German Simmental calves. Animal numbers are distributed as follows: 0–20% (60 calves), 40–60% (2 calves), 60–80% (12 calves), 80–100% (25 calves). E and F, Changes with respect to the β casein, A1A1 or A2A2, in the milk fed.

Figure 2. Box plots representing the Shannon diversity of rumen-associated bacteria. A, Shannon diversity with increasing age of calves: 6 days (red), 15 days (green) and 27 days (blue). B, Shannon diversity considering breed: 0–20% German Holstein are shown in red, 20–80% in green and 80–100% in blue. C, Shannon diversity considering the effect of milk: A1A1 in red and A2A2 in turquoise.

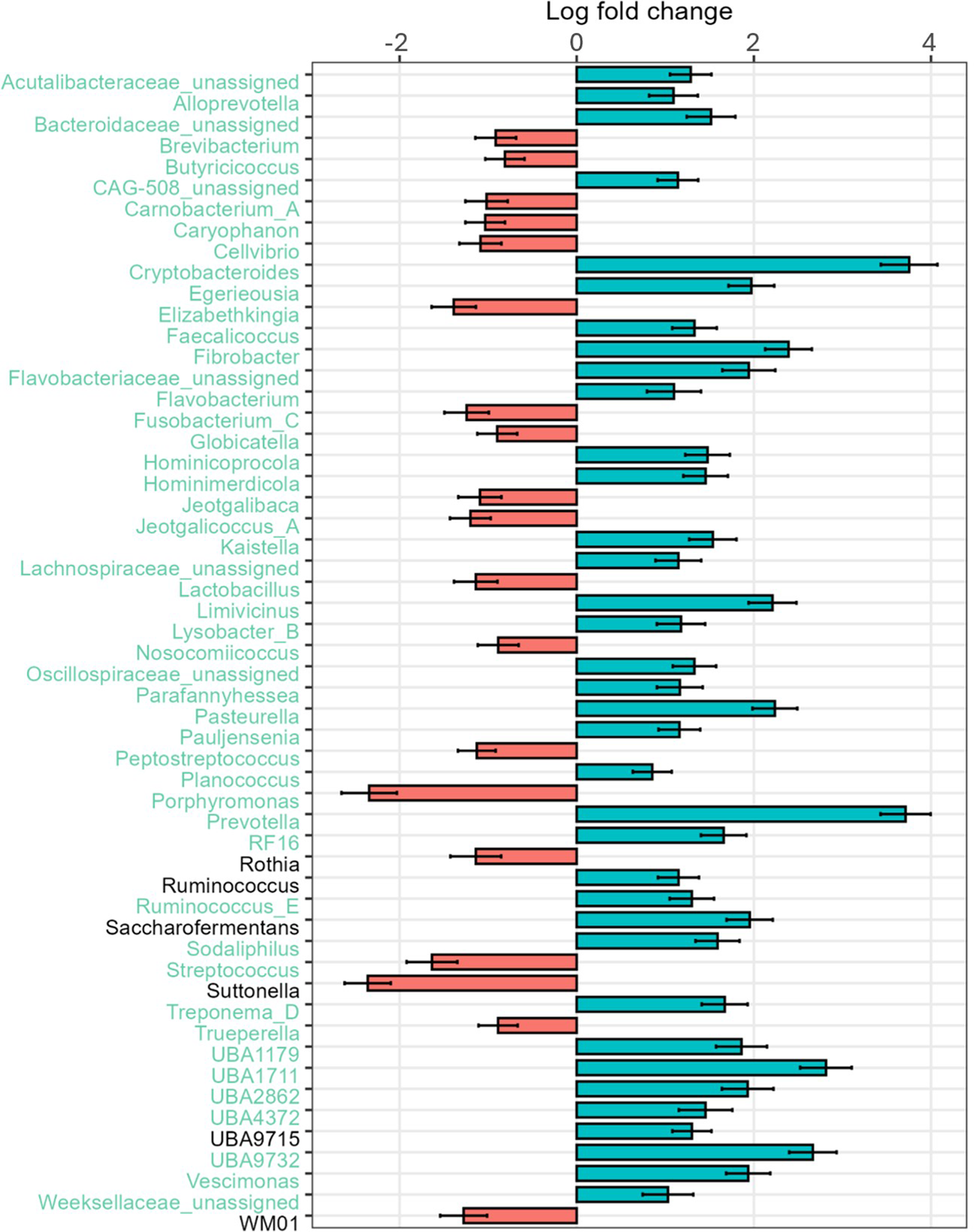

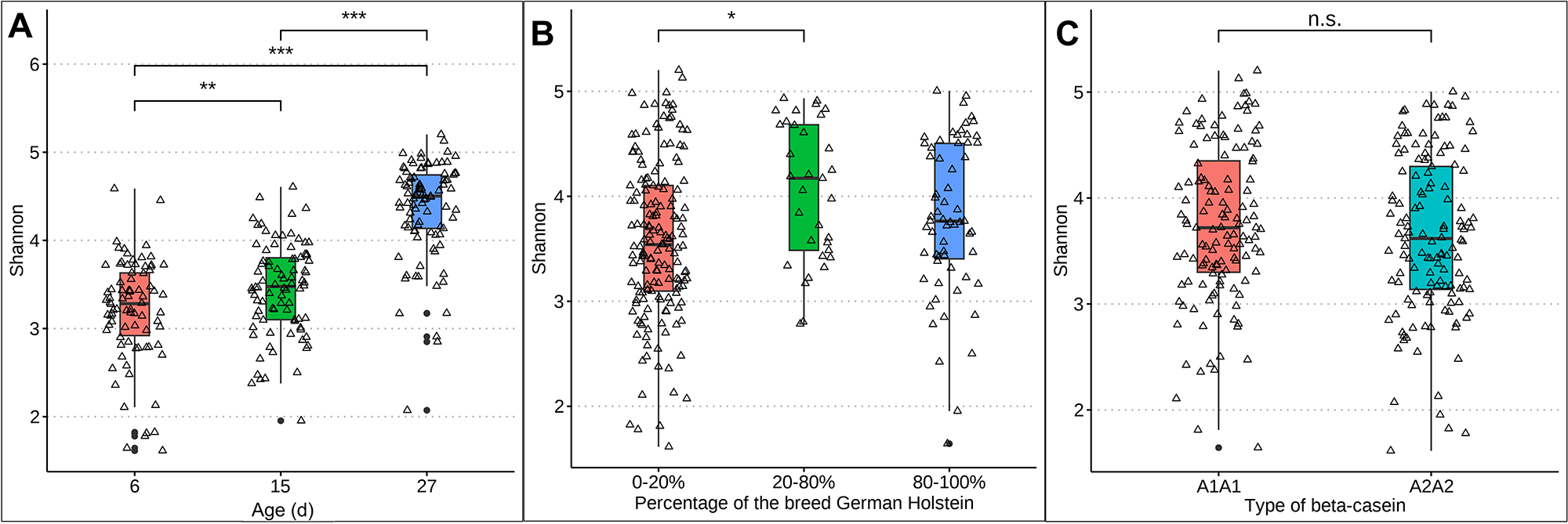

The rumen-associated microbiota data were compared regarding different effects at genus level. The total number of different genera increased with increasing age of the calves. Streptococcus had the highest relative abundance (44.6%) at the age of 6 days, with a rapid decline to 11.7% at day 27. Also, Porphyromonas was lowered in relative abundance with increasing age (18.8%–1.6%). In contrast, Prevotella was absent at day 6 and increased to 14.3% at day 27. Bifidobacterium had the lowest relative abundance in calves at the age of 15 days (1.5%), and the highest at day 27 of life (4.2%). The frequency of detected genera with a relative abundance of less than 1% increases with increasing age of the calves (13.6–32.5%) (Fig. 1B). Major changes in certain genera between day 6 and day 27 were analysed additionally by log-fold change (LFC) values. Highest positive LFC values were determined for Cryptobacteroides (LFC value = 3.75) and Prevotella (LFC value = 3.71), followed by Fibrobacter, Pasteurella and UBA1711. The genera Caryophanon, Cellvibrio, Elizabethkingia, Jeotgalibaca, Lactobacillus, Peptostreptococcus, Porphyromonas, Streptococcus, Suttonella and WM01 showed negative LFC values (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. LFC values of rumen-associated bacteria on the genus level comparing 27-day-old calves with 6-day-old calves. LFC values based on absolute abundances are shown. Red bars highlight positive LFC values, blue bars highlight those with a negative LFC value.

Impact of the breed

The taxonomic composition was examined under the influence of the factor breed, as the calves had different genetic backgrounds of GS and GH ratios. The percentages were grouped as described in Materials and methods. The high dynamic range in the sample distribution of rumen-associated bacteria based on ASV level is shown in Figure 1C. Samples from calves with 0–20% and 80–100% GH weren’t significantly different in the microbiota composition among all sampling dates (p = 0.087), as well as 20–80% vs. 80–100% (p = 0.5). With increasing percentages of the breed GH in GS calves, a significantly increased alpha diversity was observed (p = 0.01). In a pairwise comparison, the Shannon index was only significantly different between 0–20% and 20–80% (p = 0.004) GH. The mean ranged between 3.54 in GS calves and 4.17 in the crossbred group (Fig. 2B). Oral-associated bacteria also showed a dynamic range regarding the breed in beta-diversity (Supplementary Figure S1B). Alpha-diversity was not significantly influenced by breed. Means of Shannon diversity values varied between 2.49 (20–80% GH) and 2.71 (0–20% GH) (Supplementary Figure S2B). As seen in Figure 1D, the following changes can be observed in a direct comparison of the different fractions of the breed GH with increasing age on the genus level regarding relative abundances. Streptococcus was detected with the highest relative abundance in calves of the breed GS (45.5%) at the age of 6 days. For the same breed with increased age, the abundance decreased strongly (14.8%). Porphyromonas was mainly abundant in younger calves with 20–80% GH (21.2%). With increasing percentages of German Holstein, the abundance decreased. Prevotella was detected with the highest relative abundance in calves of the breed GH at 27 days (16.1%). Bifidobacterium was detected in all breeding groups. From the age of 15 days, it was detected with low relative abundances (0–2%). Actinomyces were only detected in 80–100% GH in GS calves at the age of 27 days (1.6%). Cryptobacteroides also weren’t detected in the calves at the age of 6 days, but from 15 days onward, they were detected in all breeding groups with an increased relative abundance at 27 days (15.7% in the crossbred group). Suttonella is detected with a frequency higher than 1% in calves with a low proportion of GH, independent of age. A positive log fold change value was detected for Fibrobacter (LFC value = 1.2), Desulfovibrio (1.3) and Actinomyces (1.5). Negative values for Lepagella and Jeotgalicoccus_A (LFC value = −1.1, −1.2).

Impact of the beta-caseins A1 and A2

The distribution of the ASVs was not influenced by the feeding groups over the entire sampling period (Figure 1E). For beta-casein A1, a slightly higher, but non-significant (p = 0.22) alpha diversity difference was detected. The Shannon diversity means were 3.72 (A1A1) and 3.62 (A2A2) (Fig. 2C). For oral-associated bacteria, the Shannon index was not significant (p = 0.55), Shannon diversity means were 2.58 (A1A1) and 2.70 (A2A2) (Supplementary Figure S2C). The beta-diversity of the oral-associated bacteria revealed no differences (Supplementary Figure S1C).

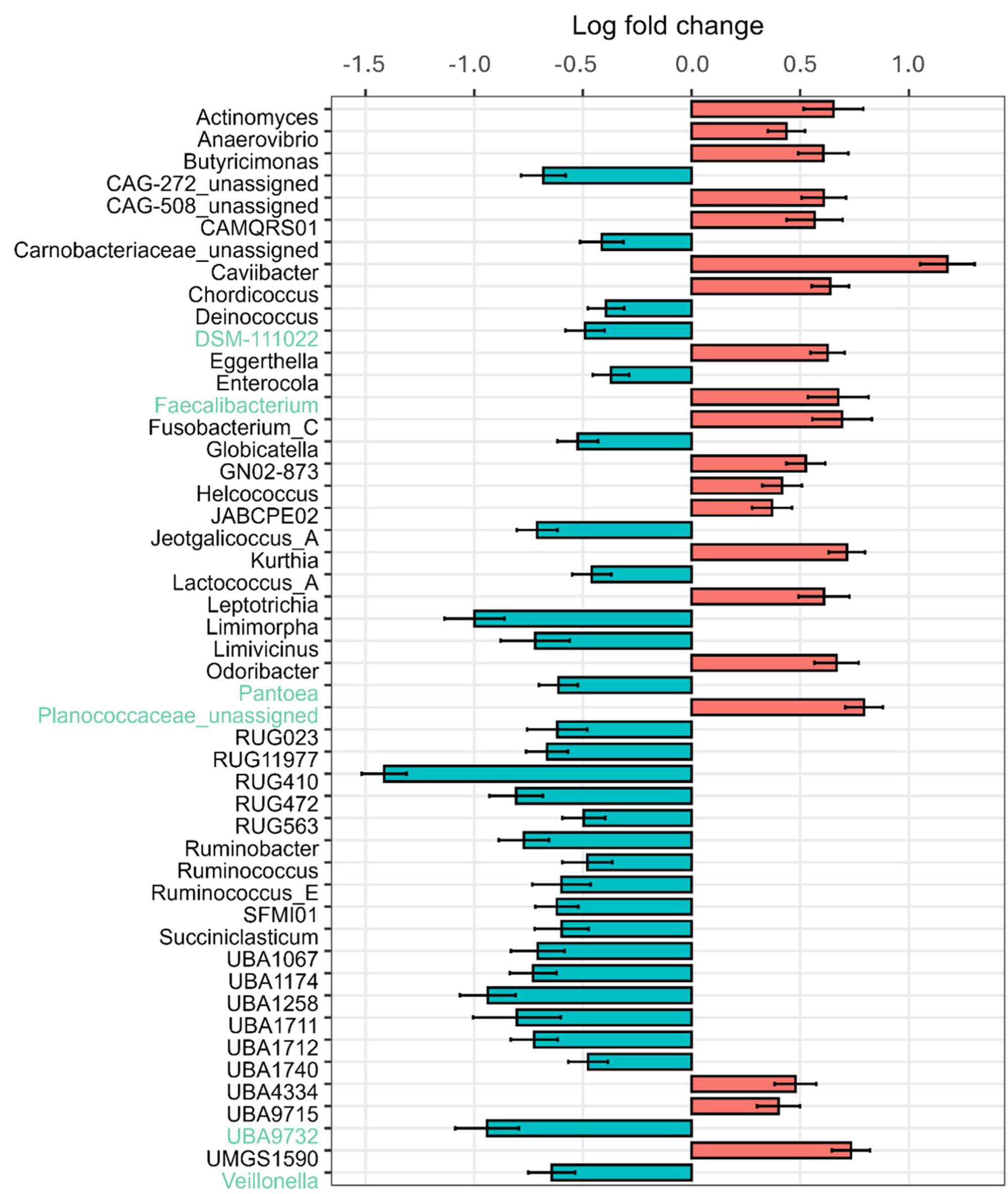

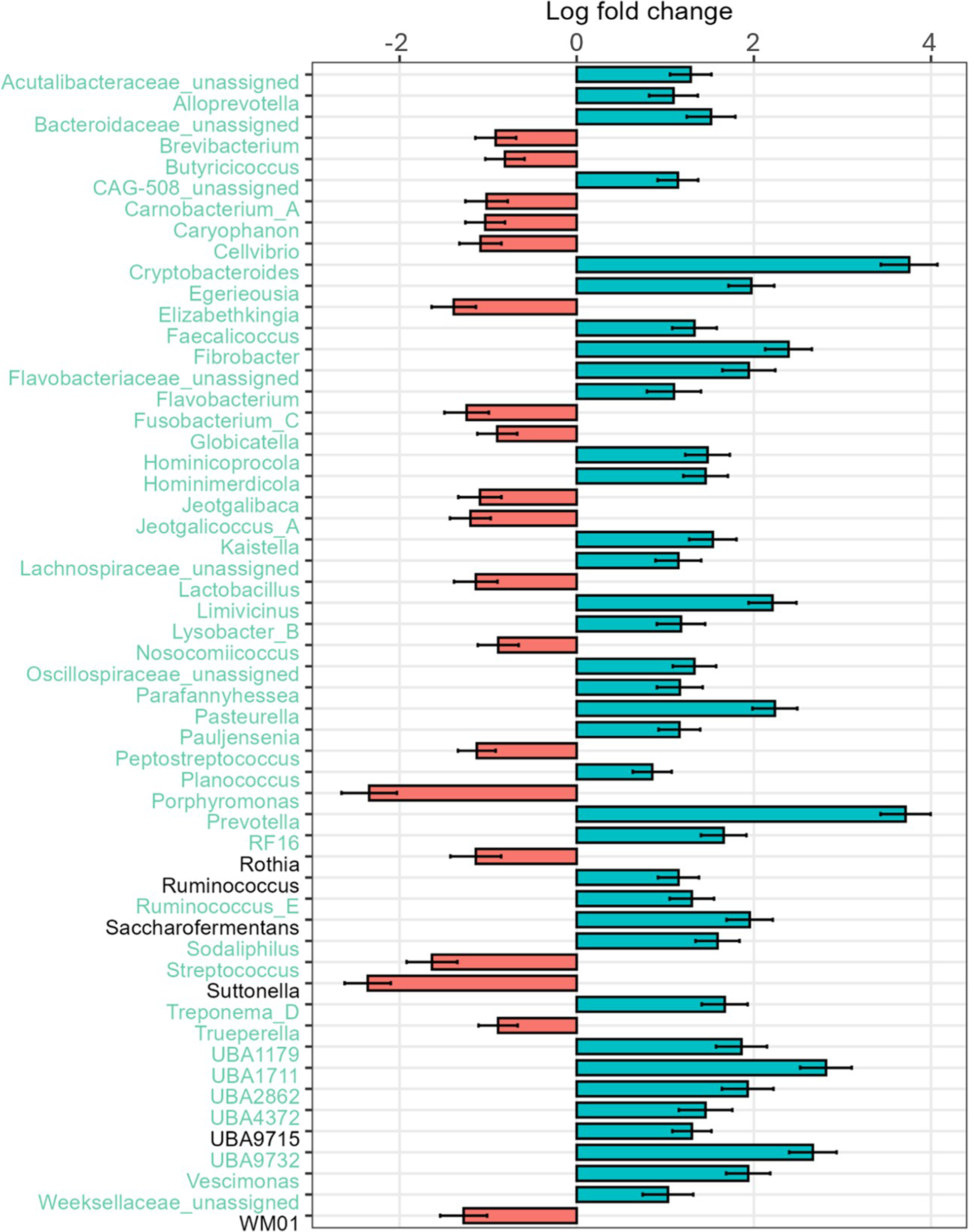

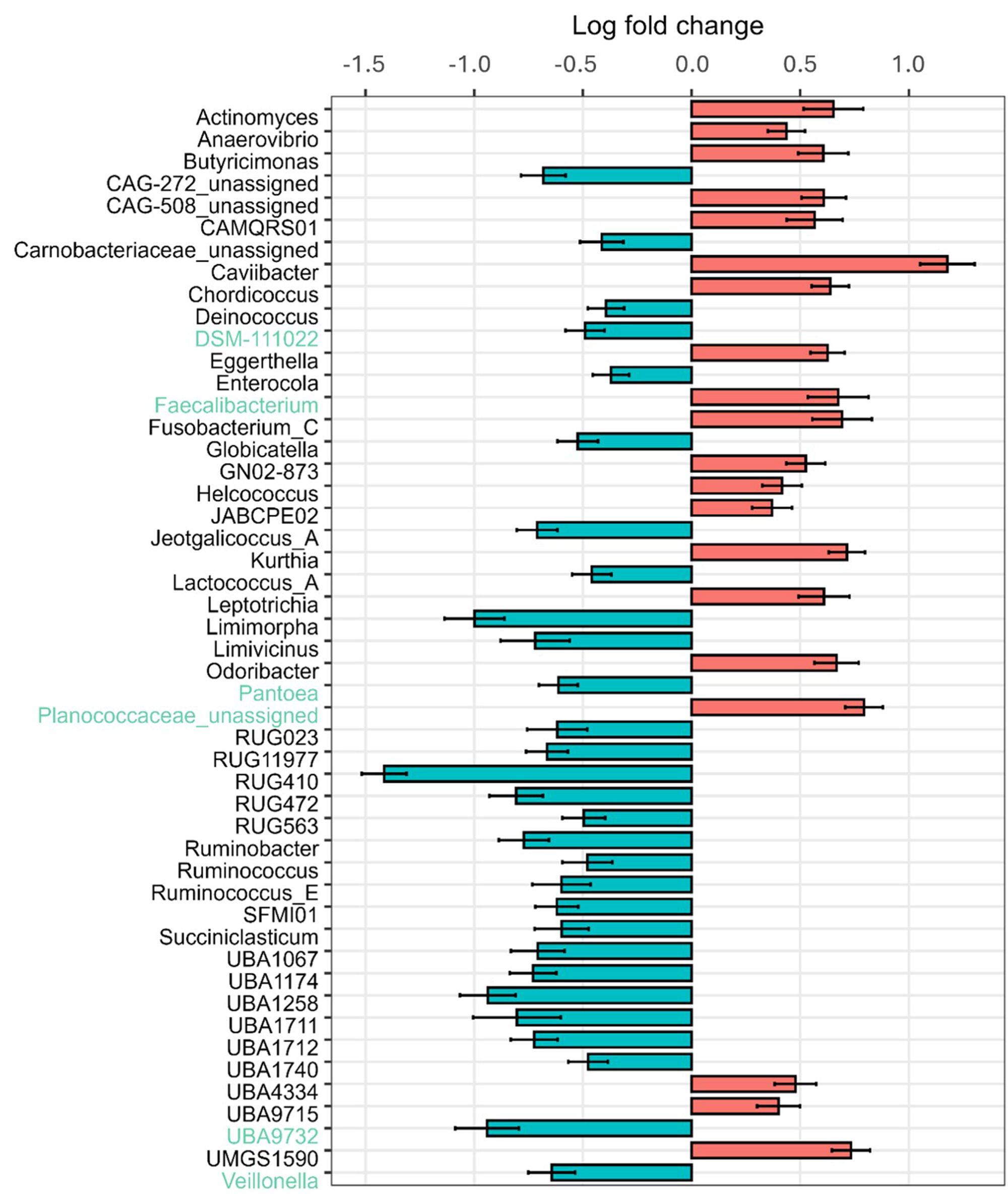

Relative abundances at the genus level were compared for the β-caseins A1 and A2 milk (Fig. 1F). An increasing abundance of genera with relative abundances smaller than 1% can be seen with increasing age for A1 milk (13.1%, 16.1% and 34.8%) and A2 milk (14.5%, 14.7% and 28.9%). Actinomyces were only detected in calves at 27 days of age fed A2 milk (1.2%). Analysis with ANCOM-BC2, considering all sampling dates, shows significantly different genera between the milks fed. There are many genera that increased significantly in absolute abundance, but also many that decreased when comparing A2 to A1. The highest positive LFC value is given for Caviibacter (LFC value = 1.18), followed by some unassigned genera and Faecalibacterium, Kurthia, Butyricimonas and Eggerthella. Those genera have a higher absolute abundance in calves fed the A2A2 milk. The highest negative LFC value is shown for RUG410 (LFC value = −1.41), followed by Limimorpha and UBA9732. For those, the abundance decreases in calves fed A2A2 milk (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. LFC values of rumen-associated bacteria on the genus level in calves comparing β-casein A2 and A1 in the milk fed. LFC values based on absolute abundances are shown. Red bars highlight positive LFC values, blue bars highlight those with a negative LFC value.

Interactions between the effects of age, breed and  $\beta $-casein

$\beta $-casein

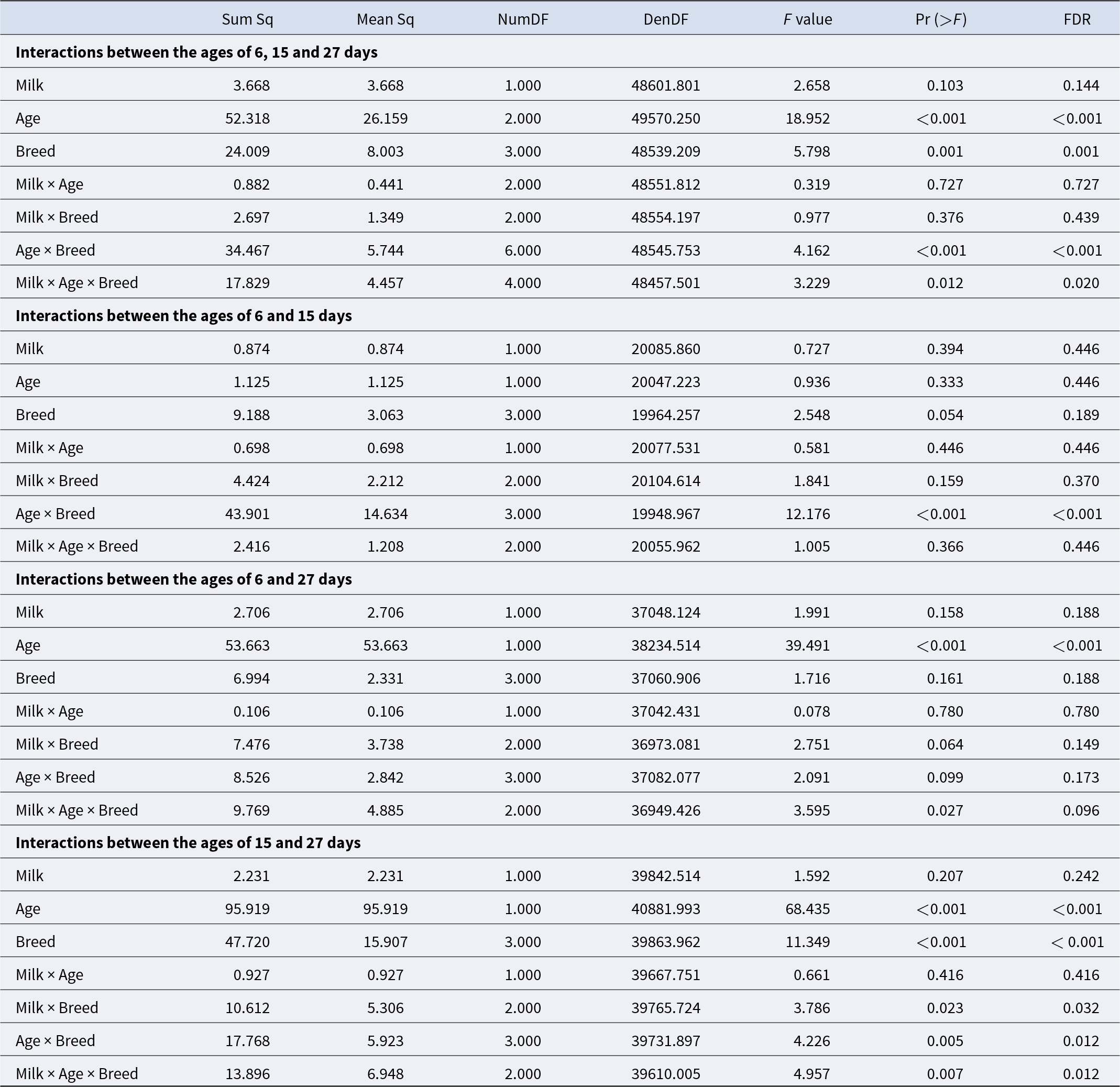

Variance analysis of the mixed linear model revealed fixed effects that might explain the variation in log-transformed bacterial counts. Taking the random effects of ASVs and all calf ages into account, the milk type (p = 0.14) showed no significant impact. A significant impact was identified for the breed (p = 0.001) and age of the calves (p < 0.001). Also, for the interaction of breed and age, a significant impact was detected (p = 0.001). For the three-way interaction between the milk type, the breed and the age, a significant impact was observed (p = 0.02). Both interactions milk type vs. age, and milk type vs. breed, had no significant effect (p = 0.73; 0.44). Microbiota from the age of 6 vs. 15 days weren’t significantly different for age, breed and milk, but they were significantly different for the interaction between the age and the breed (p = < 0.001). The interaction between age, milk type and breed was not significant (p = 0.45) (Table 1). At the ages of 6 and 27 days, no significant differences were detected except for the age (p < 0.001). Also, for the ages of 15 and 27 days, for the age and the breed, significant effects were detected (p < 0.001, p < 0.001). For the interactions of milk and breed (p = 0.032) as well as age and breed (p = 0.012), significances were detected. The three-way interaction of milk, age and breed was significant (p = 0.012) (Table 1). Significant differences were identified using pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Numerous bacterial genera differed especially between the groups of 15 and 27 days. Genera contributing most strongly with low adjusted p-values are Bacteroides, Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, Collinsella, Streptococcus, Porphyromonas, Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium_C.

Table 1. ANOVA of the effects age, breed and milk, and their interactions between different sampling events. p-Values are corrected with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Sum Sq: variance explained by the effect, the total amount of variation, Mean Sq: variance per degree of freedom (Sum Sq/Num DF), Num DF: degrees of freedom associated with the effect being tested, Den DF: degrees of freedom associated with the error term in the model (approximated in mixed models)

Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between the different breeds over time. Especially between 15 and 27 days of age, the bacterial abundance differed markedly among the breed groups. The biggest differences were observed between GS and GH calves (p < 0.001). The results support a significant interaction between breeding group and age of the calves at 15–27 days.

When calculating the same for the effect of diarrhoea, only the ages of 6 and 15 days were included. No significant impact was detected. Also, for the mean faecal score, no significances were found.

Discussion

Separation of oral-associated and rumen-associated bacteria

In this study, the separation into rumen- and oral-associated bacteria has been performed based on the work of Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021) and Kittelmann et al. (Reference Kittelmann, Kirk and Jonker2015). The same rumen-associated bacteria besides Pseudomonadota were the main representatives shown in the work by Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021), who examined calves at the age of 42–140 days. As well as a further strong presence of Bacteroidetes and an increasing differentiation of bacterial genera during ageing, which matches the present study. Based on the method that was used here, the possible use of buccal swabs and post-processing in silico handling of the bacterial data to receive rumen-associated results was successfully confirmed again.

Microbial dynamics along the first weeks of life

The development of the microbiome in the rumen of calves during early life has been investigated in many studies under different conditions (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021; Jami et al. Reference Jami, Israel and Kotser2013; Oikonomou et al. Reference Oikonomou, Teixeira and Foditsch2013). In this study, differentiations according to the calves’ age were noticed as well. Increasing ASV numbers during ageing reflect the colonization of bacteria in the forestomachs, starting from a sterile or low colonized population at birth. External factors like components of the dam’s milk, pathogens and change in feed are triggering a strong establishment of a more diverse microbiome as well (Malmuthuge et al. Reference Malmuthuge, Griebel and Le Guan2015). Kappes et al. (Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024) described a negligibly low intake of hay in the first 2 weeks of life, to which the calves had access ad libitum. A further intake of small amounts of hay after the first 2 weeks cannot be excluded. With the intake of solid feeds, microbial activity increases, and the microbiota would be optimized according to age. A strong clustering for rumen-associated bacteria regarding the age groups (Fig. 1) is comparable to results from Jami et al. (Reference Jami, Israel and Kotser2013). They took samples via stomach tubing and explored the rumen bacterial community from birth to adulthood. Newborn calves were fed colostrum exclusively. The correlation between saliva and rumen results could be higher, as there is a high level of exchange between the rumen and oral cavity on the one hand, and the influence of the small and large intestines is minimised on the other. Dill-mcfarland et al. (Reference Dill-Mcfarland, Breaker and Suen2017) investigated calves that were fed pasteurized milk and were offered calf starter supplement. They showed that bacteria quickly establish after birth, as early as week two of life, which is comparable to samples taken from calves at the age of 15 days in this study. Here, the genus Streptococcus had the highest relative abundance in six-day-old calves, significantly decreasing with increasing age. Jami et al. (Reference Jami, Israel and Kotser2013) detected that in the first days of life, the vast majority of the reads belonging to Firmicutes show the genus Streptococcus. In calves that were at least 2 months old, only small proportions of reads were associated with Streptococcus. This leads to the conclusion that the abundance in the present study is going to remain low at an older age. In an experiment from Oikonomou et al. (Reference Oikonomou, Teixeira and Foditsch2013), Streptococcus was, amongst others, one of the most abundant genera during the first week of life. Du et al. summarized that within 8 hours after birth, Streptococci and E. coli colonized all GIT regions of the calf. Streptococcus is aerotolerant, which explains the decrease with increasing age. Oxygen is used up by other bacteria and is displaced by anaerobic bacteria. The abundance could therefore also be high, as it is not influenced by the more aerobic environmental conditions in samples taken from the oral cavity. Lactobacillus was present in a higher absolute abundance in calves that were 6-day-old and decreased with increasing age. They are common members of the GIT, mouth and female genital tract and beneficial in terms of reducing diarrhoea, increasing the weight gain in calves, protection against pathogenic bacteria, reducing the risk of inflammatory responses and promoting gut health (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021). In this study, Bacteroides were significantly increased in their absolute abundance in calves between 6 and 27 days old. They are responsible for the degradation of starch and sugars (Brade and Distl Reference Brade and Distl2015). Song et al. (Reference Song, Malmuthuge and Steele2018) detected higher abundances of mucosa-attached Ruminococcus in calves at the age of 21 days than in younger calves, which is in line with the findings within this study. Ruminococcus are modulating the expression of mucin-related genes and increasing the mucin production and are known to degrade hemicellulose and cellulose (Brade and Distl Reference Brade and Distl2015). Species that belong to Ruminococcus may thereby play important roles in host resistance towards invasion of pathogenic bacteria through reinforced barrier functions (Song et al. Reference Song, Malmuthuge and Steele2018). A significant increase in the absolute abundance of Prevotella was detected (Fig. 3). This genus was often detected as the most abundant one in other studies. O’Hara et al. (Reference O’Hara, Kenny and McGovern2020) detected an abundance of 22.49% in the rumen of calves at a young age. They detected this especially between 7- and 14-day-old calves. This is in line with the findings of this study. Prevotella are connected to the degradation of plant polysaccharides (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021). Jami et al. (Reference Jami, Israel and Kotser2013) detected a shift in the composition of the phylum Bacteroidetes. First, Bacteroides had the highest abundance, but then they were partially replaced by Prevotella, which is in line with the present study. In the present study, the genus Bifidobacterium was detected with decreasing relative abundances (Fig. 1). Oikonomou et al. (Reference Oikonomou, Teixeira and Foditsch2013) revealed Bifidobacterium, together with Streptococcus, as the most prevalent genera during the first 7 days of life. The bacterium forms biofilms, which also prevent pathogen invasion and stimulate the host’s immune functions (Song et al. Reference Song, Malmuthuge and Steele2018). In infants, this genus is known for its ability to degrade oligosaccharides in breast milk. This may explain its abundance, especially in the first week of life (Flint et al. Reference Flint, Scott and Duncan2012). In this study, genera of the phyla Actinomycetota and Pseudomonadota were detected throughout the trial. Actinomycetota have an important role in the conversion of milk components (Amin et al. Reference Amin, Schwarzkopf and Kinoshita2021) and were present with the highest relative abundance in samples from calves that were 6 days old, subsequently lower and nearly constant. Pseudomonadota were prevalent at all ages, most prominent at 15 days (Fig. 1). In contrast, Jami et al. (Reference Jami, Israel and Kotser2013) detected a gradual decreasing abundance of Proteobacteria with increasing age, and Actinobacteria were mainly present in newborn calves, and Oikonomou et al. (Reference Oikonomou, Teixeira and Foditsch2013) detected Proteobacteria mainly present in the first week of life. Changes in the abundance of Pseudomonadota may be caused by Bacteroidota and Bacillota being strict anaerobes and Pseudomonadota being facultative anaerobes and thereby displaced by anaerobe phyla. Amin and Seifert (Reference Amin and Seifert2021) presented comparable results. In summary, there is a maturation process, and the detected rumen-associated bacteria change in their composition with increasing age. For oral-associated bacteria, a change in accordance with the age was detected as well, but the change was minor compared to rumen-associated bacteria, which is a good indication for the robustness of the analysis method, as the salivary microbiome should be established faster. In addition to the changes in microbial composition with increasing age as described above, analysis of variance based on the linear mixed model showed significant interactions for the different ages influencing bacterial diversity. Especially looking at differences between 6 and 15 days, but also 15 and 27 days, a significant interaction was detected. Dias et al. (Reference Dias, Marcondes and Motta de Souza2018) found the presence of Prevotella, Bacteroides and Ruminococcus in young ruminants at the age of 1 week, which is in line with the findings of this study, as described above. This supports the colonization of beneficial digestive bacteria in very early life. Compared to older calves, they detected age effects that were mostly evident for Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Streptococcus, for example. The maturation process of the microbiota shows a strong increase of bacterial types, digesting first the parental milk, but as well preparing for digestion of solids in the feed after weaning. As well as a strong decrease of pathogenic bacteria for the tested healthy calves is seen. In the future, these observations can be helpful to control and improve the health and wellbeing of calves during weaning.

Impact of the breed on bacterial composition

In the present study, Streptococcus was found as the predominant genus, with slight changes in the abundance, especially in calves at the ages of 6 and 15 days. With a focus on the behaviour of Bacteroidota depending on the breeds alongside Streptococcus and others with a relative abundance of less than 1%, a more pronounced change in dependence on the breed ratio was observed: the abundance of Prevotella increased when comparing GS calves to those with increased abundances of GH. Nan et al. (Reference Nan, Li and Kuang2024) analysed faecal samples from German Simmental and German Holstein calves aged 14–32 days, using raw sequences obtained from the V3/V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The authors identified the genera Prevotella and Butyricicoccus, which produce hydrolases for the degradation of cellulose and plant polysaccharides and thereby promote the growth. As in the present study, they found Prevotella with a higher relative abundance in the German Holstein group compared to the crossbred group. Pro-inflammatory functions were found to be associated with an increased abundance of Prevotella. In the crossbred group, Nan et al. (Reference Nan, Li and Kuang2024) detected the genus Faecalibacterium to be predominant. This genus has immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties and is thereby important for the animals’ health. In addition, the intestines of the crossbred group were characterized by the abundance of Parabacteroides, Subdoligranulum, Butyricimonas and Desulfovibrio. In the present study, only Faecalibacterium was detected in crossbred calves (20–80% German Holstein) at the age of 27 days. The others weren’t detected with a relative abundance higher than 1%. Nan et al. (Reference Nan, Li and Kuang2024) discovered Bacteroides as the predominant genus in calves with high percentages of the breed German Holstein, as well as in the crossbred calves. Here, it was slightly more abundant in calves with high percentages of the breed German Holstein. In the study from Nan et al. (Reference Nan, Li and Kuang2024), Escherichia-Shigella, Butyricicoccus and Peptostreptococcus were also abundant in the German Holstein group. In crossbred calves, on the other hand, Faecalibacterium, Megamonas, Butyricicoccus and Alloprevotella were predominantly present. In both studies, Alloprevotella were mainly detected with higher abundances in crossbred calves. An experiment by Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Chen and Li2024) investigated the differences in the relative abundances of bacterial phyla in the rumen and faeces of Holstein cattle and Xinjiang Brown. Rumen samples contained higher abundances of Bacteroidetes, followed by Firmicutes and subsequently Proteobacteria. In rumen samples, they detected Ruminococcus_1 to appear in higher abundances in Holstein cattle. In the present study, the genus was not detected with a relative abundance higher than 1%. Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Chen and Li2024) also detected that some genera of the family Lachnospiraceae had higher abundances in Holstein cattle. Sandri et al. (Reference Sandri, Licastro and Dal Monego2018) studied the rumen microbiome composition in Italian Holstein and Italian Simmental. In Italian Holstein cattle, significantly higher abundances of Bacteroides and Prevotellaceae were detected. This corresponds to higher genetic merit for their milk yield. Cows with higher milk yields have a higher intake of feeds and thereby influence the structure of rumen metagenome (Sandri et al. Reference Sandri, Licastro and Dal Monego2018). This is comparable to findings of this study, although the feed (milk) intake in GH calves did not differ significantly from GS and CR (Kappes et al. Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024). Sandri et al. (Reference Sandri, Licastro and Dal Monego2018) also mentioned that the abundances of Bifidobacterium and Actinobacteria were higher in Italian Simmental cattle, which is supported by this study for GS. Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Bian and Teng2020) investigated the differences between Angus (Bos taurus) calves and Brahman (Bos indicus) calves, and crossbreds of those. Fewer mucin-degrading bacteria were detected in calves with higher proportions of Brahman. As well, less pathogenic bacteria were present, such as Campylobacter. On the other hand, more butyrate-producing bacteria were found, which are considered beneficial due to their anti-inflammatory property. This was in line with positive associations with weight gain. In general, the current studies show that the microbial development differs between breeds with increasing age, which may be due to genetic differences in immune response, digestive capacity or feed intake behaviour within the first weeks of life. This might also explain the significant interaction of breed and milk. Summarized, the comparison of bacterial development in the GIT between different breeds showed different characteristics already in young calves.

Effect of β-casein on the bacterial composition in calves at a young age

As seen in the other comparisons, especially Streptococcus and Porphyromonas, were detected to change in their abundance. The calf’s health and growth statuses during early life are very important and have significant effects on milk production during the first lactation period. Milk replacers are often used to support calf welfare (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zou and Zhang2023) and Kumar et al. (Reference Kumar, Khan and Beijer2021) studied the impact of milk replacers on bacterial community profiles in faeces from calves. They revealed that high intakes of milk replacers increased the hindgut bacterial diversity, and as a result, resulted in SCFA profiles and bacterial communities associated with higher protein fermentation.

The impact of the milk proteins β-casein A1 and A2 was mainly tested on the health of calves. In the study from Kappes et al. (Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024), investigating the same calves as in the present study, data were collected on how β-casein affects calf performance and diarrhoea occurrence. In their observation, calves fed the A1-milk had a mean of 1.90 days with diarrhoea, and the ones fed A2-milk had a mean of 2.22 days with diarrhoea, declared as not significant (p = 0.22). There was no difference in the amount of milk consumed or weight gained up to 15 days of age between A1- and A2-milk. Hohmann et al. (Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021) investigated the effect of milk containing either homozygous A1 or A2 β-casein on the health and growth parameters of dairy calves in the first 3 weeks of life. Calves of the breeds German Holstein, German Simmental and crossbreds of those were included in the trial. In contradiction to the study from Kappes et al. (Reference Kappes, Schneider and Schweizer2024), Hohmann et al. (Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021) detected a higher faecal score and diarrhoea prevalence in calves fed A2 milk (2.56 and 10%, respectively) compared with those fed A1 milk (1.97 and 6%, respectively), along with a lower milk intake (6.96 vs. 7.28 L/day, respectively). However, the average daily gain was similar between the two feeding groups (0.64 ± 0.08 vs. 0.75 ± 0.07 kg/day; p = 0.07). They explained this with a higher protein content of A2-milk, which was also observed by Ben Farhat et al. (Reference Ben Farhat, Hoarau and Tóth2023) in Jersey cows, although the differences among β-casein genotypes were not significant. Based on the findings of Hohmann et al. (Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021), feeding A2 milk does not appear to be as beneficial for the calf’s health as feeding A1 milk, particularly from a diarrhoea perspective. Although A2 milk reduces the cleavage of β-casomorphin-7, which might have positive effects on the development of pre-weaned calves (Hohmann et al. Reference Hohmann, Yin and Schweizer2021), De Noni et al. (Reference De Noni, FitzGerald and Korhonen2009) reported an anti-diarrhoeal effect of β-casomorphins. Regarding the microbiome, Nuomin et al. (Reference Nuomin, Baek and Tsuruta2023) have investigated the effect of A1- and A2-milk fed on gut microbiota and fermentation in mice. Only small differences between A1- and A2-milk have been noticed in the microbiota composition, declared as not significant. These observations are in line with the results of the present study for both feeding groups. The effect ![]() $\beta $-casein showed no significance when testing the interactions with a linear-mixed model, independent of the age of the calves. Also, in combination with the age or the breed of the calves, no interaction was detected for young calves. One explanation for this observation could be the oesophageal groove reflex, which causes milk to be diverted directly into the abomasum, thus, no direct effect on the rumen microbiota might occur. Summarized, there are only minor differences in the main composition of the microbiota regarding the different types of milk fed. However, the variation in the composition of the microbiota for small relative proportions, which at the same time show a large diversification, is very high and shows a dependence on the milk supply.

$\beta $-casein showed no significance when testing the interactions with a linear-mixed model, independent of the age of the calves. Also, in combination with the age or the breed of the calves, no interaction was detected for young calves. One explanation for this observation could be the oesophageal groove reflex, which causes milk to be diverted directly into the abomasum, thus, no direct effect on the rumen microbiota might occur. Summarized, there are only minor differences in the main composition of the microbiota regarding the different types of milk fed. However, the variation in the composition of the microbiota for small relative proportions, which at the same time show a large diversification, is very high and shows a dependence on the milk supply.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to analyse the development of the oral- and rumen-associated bacteria in young calves under the effect of ![]() $\beta $-casein A1 and A2 and the breeds German Holstein, German Simmental and crossbreds of those. With increasing age, a significant change in the bacterial distribution of rumen-associated bacteria was observed. There was a strong increase in bacteria that are necessary for the subsequent digestion of cellulose and starch, and a strong decrease in pathogenic bacteria. For oral-associated bacteria, the change was not as strongly detected as for rumen-associated bacteria and became established more quickly, demonstrating the robustness of the analysis. Looking at the breed, different bacterial compositions were already found in young calves in addition to a similar main distribution at the genus level. These changes could be breed-specific in older cows. Also, the interaction of breed and age had a significant impact. When comparing the two types of

$\beta $-casein A1 and A2 and the breeds German Holstein, German Simmental and crossbreds of those. With increasing age, a significant change in the bacterial distribution of rumen-associated bacteria was observed. There was a strong increase in bacteria that are necessary for the subsequent digestion of cellulose and starch, and a strong decrease in pathogenic bacteria. For oral-associated bacteria, the change was not as strongly detected as for rumen-associated bacteria and became established more quickly, demonstrating the robustness of the analysis. Looking at the breed, different bacterial compositions were already found in young calves in addition to a similar main distribution at the genus level. These changes could be breed-specific in older cows. Also, the interaction of breed and age had a significant impact. When comparing the two types of ![]() $\beta $-casein fed, minor differences were found in the bacterial composition regarding rumen-associated bacteria. The procedure for analysing and evaluating saliva samples regarding effects of the milk fed and the breed provided good insights into the development of the microbiota in the forestomachs, and the separation of oral- and rumen-associated bacteria was successful.

$\beta $-casein fed, minor differences were found in the bacterial composition regarding rumen-associated bacteria. The procedure for analysing and evaluating saliva samples regarding effects of the milk fed and the breed provided good insights into the development of the microbiota in the forestomachs, and the separation of oral- and rumen-associated bacteria was successful.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/anr.2025.10024.

Data availability statement

Sequences were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive under the accession number PRJEB100822.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded partially by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Programa Institucional de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior (PDSE), public notice N° 10/2022 (Brazil). The authors acknowledge support by the High Performance and Cloud Computing Group at the Zentrum für Datenverarbeitung of the University of Tübingen, the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC and the German Research Foundation (DFG) through grant INST 37/935-1 FUGG.

Author contributions

Anouk Herrmann: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing – original draft. Roberto Kappes: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Victoria Schneider: methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing. Deise Knob: methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing. André Thaler Neto: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review and editing. Armin Scholz: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing. Jana Seifert: conceptualization, methodology, resources, project administration, supervision, writing – original draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed on animals in this study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the government of Upper Bavaria under protocol number ROB-55.2–2532.Vet_03–22–20.