Introduction

Service design is a user-centred approach to creating and designing public services (Trischler et al., Reference Trischler, Dietrich and Rundle-Thiele2019). This approach is grounded in service design theory, which questions how the needs and experiences of users can be incorporated into the service design process to facilitate greater efficiency, effectiveness, and responsiveness. However, the application of service design to public service provision is still in its early stages. Therefore, this Cambridge Element contributes to public management research and practice by discussing how service design principles and tools can be leveraged to improve public service provision.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of service design in public services, understanding of the links between service design, citizen engagement, and value creation is lacking – an issue that has moved to the forefront of the service design field (Andreassen et al., Reference Andreassen, Lervik-Olsen and Snyder2016). Moreover, the focus of service design has shifted from service design by experts towards service co-design with users (Trischler et al., Reference Trischler, Pervan, Kelly and Scott2018). Embedded within this shift is a focus upon value creation as the core element of service delivery. While early service management theory focused on service production and co-production, now the focus has moved to the use and consumption of services and the means through which services can add value to service users’ lives (Vargo et al., Reference Vargo, Maglio and Akaka2008; Gronroos & Voima, Reference Gronroos and Voima2013).

Current research on public service design mainly focuses on how to engage service users and embed their experiences in the decision-making processes that govern public service provision (Trischler et al., Reference Trischler, Dietrich and Rundle-Thiele2019; Trischler & Trischler, Reference Trischler and Trischler2020). In this context, design strategies provide a disruptive solution to challenges commonly associated with engaging citizens. Service design theory is particularly relevant given its emphasis on a citizen orientation and its focus on empathy, thus enabling a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with public service provision and the context the service is being provided in. By grounding service design in a citizen orientation that emphasises value creation for service users, new and innovative solutions that align with the ideas and needs of all actors involved can be generated. Crucially, another important aspect of service design is that all proposed modifications are tested: to ensure their feasibility, the solutions are tested with small-scale prototypes that can be scaled up and diffused once validated. Therefore, design strategies and methodologies offer a novel, underutilised perspective on ways of leveraging user engagement to foster value-adding solutions to challenges associated with public service delivery.

Public services are complex, and their design must account for the needs of multiple stakeholders, including service users, service providers and policymakers. Acknowledging this complexity, this Element offers a distinctive approach to service design in public services by combining theoretical and practical perspectives. The theoretical lens draws from existing literature on public service logic and public service delivery to construct a conceptual framework. The practical perspective is enriched with diverse case studies across public service sectors that illustrate the tangible application of service design. Embracing a multidisciplinary stance, insights from public management, design science and social sciences converge to provide a holistic approach to service design. Adopting a user-centred design approach, the Elements places the needs and experiences of service users at the forefront of the design process.

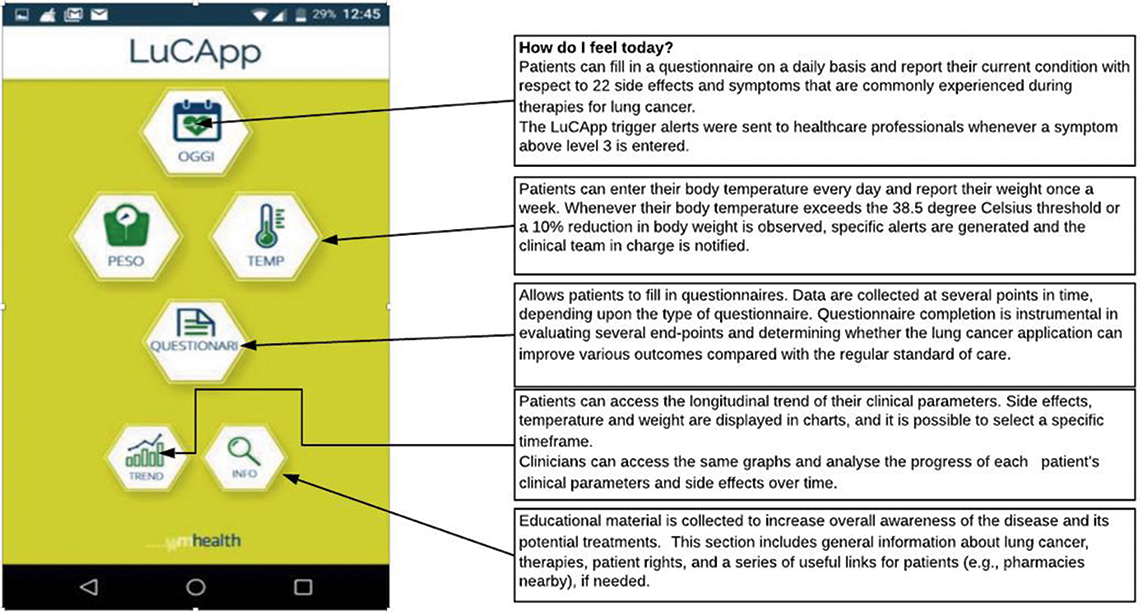

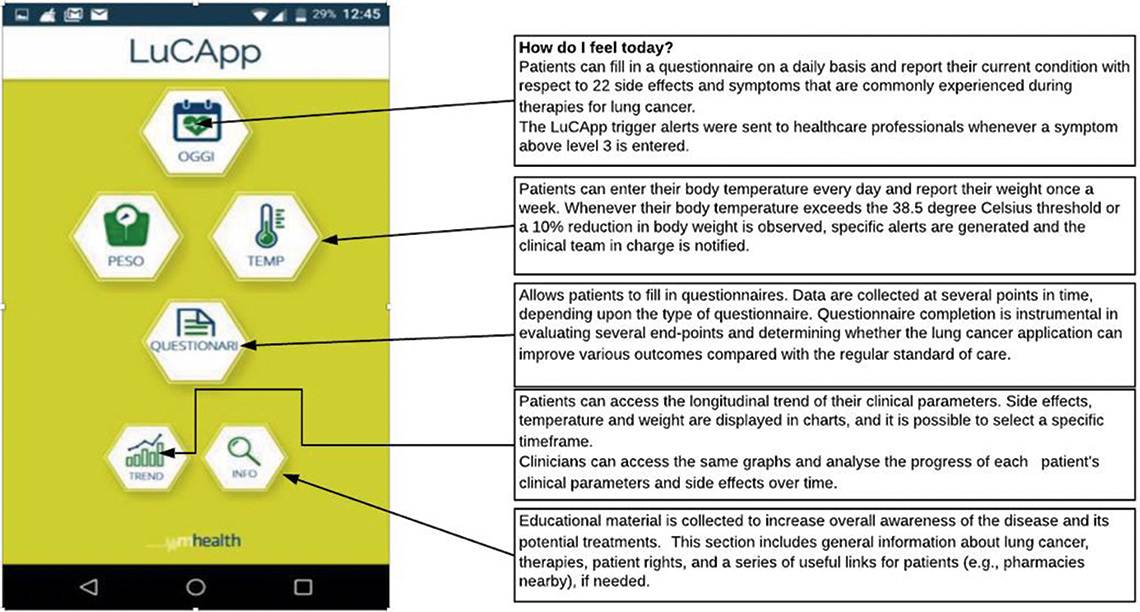

In the sections that follow, we will provide an overview of service design research in public management and public administration, with a particular emphasis on user-centred approaches and tools for service design. Drawing on this conceptual baseline, we then provide three empirical studies that showcase innovative applications of service design in public services. These include redesigning municipal services post-COVID-19, improving satisfaction with public education, and developing a mobile health application to improve the well-being of patients with lung cancer. As we discuss, each study illustrates the importance of user-centred design approaches and tools, digital transformation, and the direct engagement of service users to enhance the value of public services. Additionally, we address the critical issue of inclusivity in service design, acknowledging potential biases favouring those with more resources, and offering specific, practical guidance on how to mitigate these challenges.

1 Understanding Service Design Theory for Improving Public Services

1.1 Definition and Evolution of Service Design Theory

The term service design emerged in the early 1980s to integrate the design of tangible products with the innovation of intangible service components – in effect, replacing unsystematic trial-and-error with a more deliberate, end-to-end logic. Shostack’s seminal work (Reference Shostack1982, Reference Shostack1984) framed this logic as a systematic planning exercise: every step in the service process should be mapped, tested, and iteratively refined so that each customer touchpoint delivers consistent value.

Building on this process view, Zomerdijk and Voss (Reference Zomerdijk and Voss2010) shifted attention from operational consistency to experience-centricity. They demonstrate that when designers understand the emotions, preferences, and desires that surface along the customer journey, they can deliberately script ‘moments that matter’, creating distinctive memories rather than merely efficient transactions.

As digital channels proliferated, Glushko (Reference Glushko2010) widened the lens again, classifying service interactions as person-to-person, person-to-machine, or machine-to-machine. This triad acknowledges that technology is now a co-actor in service delivery; designing smooth hand-offs among people and smart devices has become as critical as choreographing face-to-face encounters.

Kimbell (Reference Kimbell2011) then reconceptualised service design as an exploratory, open-ended inquiry. Instead of following a linear blueprint, designers are encouraged to embrace uncertainty, prototype early, and iterate often – an approach that keeps the process responsive to emergent user insights.

Recognising that experiences unfold in concrete settings, Secomandi and Snelders (Reference Secomandi and Snelders2011) foreground the service interface: the blend of material artefacts, physical environments, and embodied human interactions that mediate every encounter. Their holistic perspective reminds us that the tangible and intangible are inseparable in practice.

Andreassen et al. (Reference Andreassen, Lervik-Olsen and Snyder2016) translate these ideas into a managerial agenda, positioning service design as a vehicle for customer-centric transformation. By systematically surfacing and addressing user needs, organisations can boost satisfaction and loyalty while gaining operational insight.

Finally, Karpen et al. (Reference Karpen, Gemser and Calabretta2017) highlight the capabilities and culture required to sustain such efforts. Design thinking must permeate everyday routines, and cross-functional collaboration must be institutionalised if service design is to move beyond isolated projects and influence strategic direction.

Together, these contributions chart a progression – from systematic planning, to immersive experience crafting, to technology-mediated interactions, and finally to organisational capability building. This trajectory reveals service design as both a method (how to map and improve service processes) and a mindset (how to embed user-centred, exploratory thinking across the organisation). The next subsection builds on this foundation by examining how these principles extend to service design in the context of public service logic, demonstrating the continued evolution of service design in contemporary contexts.

1.2 Service Design in the Context of Public Service Logic

Research in the field of services provides important perspectives for public administration and management, contributing to the conceptual advancement within the developing Public Service Logic (PSL) (Hardyman et al., Reference Hardyman, Kitchener and Daunt2019; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Cucciniello, Keast, Nabatchi and Verleye2023; Strokosch & Osborne, Reference 82Strokosch and Osborne2023). Early service research distinguished services from tangible goods, highlighting consumer participation due to the distinctive characteristics of services – intangibility, inseparability, perishability, and heterogeneity (Zeithaml et al., Reference Zeithaml, Parasuraman and Berry1985; Nankervis et al., Reference Nankervis, Miyamoto, Taylor and Milton-Smith2005; Grönroos, Reference Grönroos2016; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Shulver, Slack and Calrk2020).

A foundational influence on this evolution has been the development of Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic) by Vargo and Lusch (Reference Vargo and Lusch2004, Reference Vargo and Lusch2008, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016), which reconceptualised service as the application of operant resources (e.g. skills and knowledge) for the benefit of others and positioned value as co-created by multiple actors rather than delivered unilaterally. S-D Logic introduced a shift from goods-dominant perspectives to a framework where service (singular) is the basis of all exchange, with key axioms including: service as the fundamental basis of exchange, actors as resource integrators, and value as phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary. These principles laid critical groundwork for PSL by foregrounding co-creation, actor interdependence, and the contextual nature of value (Vargo & Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2017).

The transition towards a service logic in public administration, as advocated by Osborne and Strokosch (Reference Osborne and Strokosch2013), builds on and adapts these foundational ideas to the public sector context. PSL focuses on public services not as tangible products but as platforms for co-creating value through diverse user experiences (Hardyman et al., Reference Hardyman, Kitchener and Daunt2019; Osborne, Reference Osborne2020; Strokosch & Osborne, Reference Osborne2020; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Cucciniello, Nasi and Zhu2022a; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Cucciniello, Cui and Elgar2024). For instance, Osborne (Reference Osborne2020) emphasises that public service delivery does not involve ownership transfer, but rather is an intangible, relational process aimed at generating public value. Public services are characterised by user participation, shared responsibility, and context-dependent value, contrasting with the standardised, consumption-oriented model typical of manufactured goods (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Radnor and Nasi2013).

This conceptual convergence between S-D Logic and PSL underscores that value in public services emerges through lived experiences, interactions, and institutional arrangements – echoing S-D Logic’s focus on service ecosystems and value-in-context (Vargo & Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2008, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016). It also reinforces that PSL is not a departure from but rather a contextual extension of S-D Logic, adapted to the governance, ethical, and institutional complexity of public services.

Bridging this discussion with the evolution of service design methodologies reveals a natural progression in how services are conceptualised and delivered. The emphasis on user experiences and interactions aligns with service design’s commitment to user-centredness, creativity, and empathy (Simon, Reference Simon1969; Bason, Reference Bason2017; Bason, Reference Bason2017; McGann et al., Reference McGann, Blomkamp and Lewis2018). Service design processes extend value co-creation principles by actively integrating the diverse knowledge, needs, and social contexts of service users into design and delivery. In doing so, service design reinforces the foundational S-D Logic notion that value emerges through collaborative, contextual, and dynamic engagements among actors within service ecosystems.

This integrative approach enriches both service design and PSL by emphasising that public value is not merely delivered but co-constituted through continuous, reciprocal interaction among diverse stakeholders.

Service design has attracted scholarly attention since the 1970s and has since emerged as a distinctive paradigm challenging expert-driven design methodologies (Simon, Reference Simon1969; Bason, Reference Bason2017; Bason, Reference Bason2017). Traditional approaches, emphasising instrumental rationality and expert knowledge, are contrasted by service design methodologies that prioritise creativity, curiosity and empathy, particularly through human-centredness, problem-solving, testing, and iteration (McGann et al., Reference McGann, Blomkamp and Lewis2018).The scholarly literature on service design in public sector organisations reveals a growing interest in enhancing public services through innovative design approaches. Human-centred design (HCD) has gained prominence as a valuable framework for addressing the evolving needs of citizens and stakeholders in the public sector (Brown, 2008) and widely adopted in public service innovation, particularly in public service innovation, due to its emphasis on empathy, user involvement, and iterative development (Bjögvinsson et al., Reference Bjögvinsson, Ehn and Hillgren2012; Bason, Reference Bason2017). The approach typically unfolds in phases – inspiration (understanding user needs), ideation (generating and prototyping solutions), and implementation (delivering and scaling interventions). In public service settings, HCD supports inclusive innovation by foregrounding empathy, user voice, and iterative learning (Bason, Reference Bason2010; Bjögvinsson et al., Reference Bjögvinsson, Ehn and Hillgren2012).

Researchers stress the importance of understanding the unique challenges of the public sector when applying service design principles (Meroni & Sangiorgi, Reference Meroni and Sangiorgi2011). To this end, service design in the public sector involves improving efficiency and fostering citizen engagement and satisfaction (Mulgan et al., Reference Mulgan, Tucker, Ali and Sanders2007). The integration of co-creation methods, where citizens actively participate in the design process, is identified as a key element in achieving more responsive and inclusive public services (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Fernandes and Raposo2016). Additionally, the literature highlights the role of digital technologies in augmenting service design efforts within the public sector (Haug et al., Reference Haug, Dan and Mergel2023). E-government initiatives, incorporating service design principles, aim to leverage information and communication technologies for more accessible, transparent and user-friendly public services (Chun et al., Reference Chun, Shulman, Sandoval and Hovy2010; Cucciniello et al., Reference Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen2017). Building on the aforementioned points, service design has evolved from focusing solely on the delivery of predefined, functional services to shaping the broader servicescape – the physical, social, and institutional environment in which services are experienced and co-created (Bitner, Reference Bitner1992; Wetter-Edman et al., Reference Wetter-Edman, Sangiorgi and Edvardsson2014; Sangiorgi & Prendiville, Reference Sangiorgi and Prendiville2017).

This emphasises the creation of positive experiences for those interacting with services, transcending immediate user needs to consider long-term impacts on users’ lives and societal transformation (Patrício et al., Reference Patrício, Fisk and Cunha2008; Kimbell, Reference Kimbell2011; van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020). Service design achieves this goal by investigating stakeholders’ interactions, experiences and values through a methodology underpinned by the principles of openness, participation and inclusivity (Schwoerer et al., Reference Schwoerer, Kuehnl and Kuester2022).

A key to design methodologies within the PSL framework is to embed user-centredness throughout problem identification, understanding, and solution development in iterative processes (Wetter-Edman et al., Reference Wetter-Edman, Sangiorgi and Edvardsson2014). Accordingly, two approaches within service design, the informational and inspirational approaches, present different perspectives on how to embed user-centredness in the design process. The informational approach focuses on uncovering service users’ needs through scientific research, relying on principles of reliability, validity and rigor (Howlett et al., Reference Howlett, Mukherjee and Woo2015). In contrast, the inspirational approach roots itself in experimentation, focusing on ambiguity and generating future-focused solutions exemplified by policy or living labs (Sanders, Reference Sanders and 80Potter2005; van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020).

The emphasis on participation and inclusion within service design holds particular relevance to public services, where collectiveness is fundamental to participatory processes and outcomes. Yet, despite the promises of innovation and a user-centred approach, challenges persist regarding the practical implementation of service design in the public sector. For example, some argue that existing attempts to apply service design principles are reductionary, focusing on constituent parts while neglecting the broader service ecosystem, which, in turn, may limit the transformative potential of this approach to public service design (Howlett, Reference Howlett2014; Vink et al., Reference Vink, Koskela-Huotari, Tronvoll, Edvardsson and Wetter-Edman2021a).

Moreover, questions arise as to whether public service organisations (PSOs) can fully embrace quick and iterative problem-solving approaches, given not only the sector’s perceived aversion to risk (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Fernandes and Raposo2016) but also the significant legal and procedural constraints they operate under. It is not simply a matter of risk aversion or inertia; many PSOs must adhere to strict due process requirements, including transparency, accountability, and fairness, which limit their capacity for rapid iteration. In some jurisdictions, public sector decisions are subject to judicial review, adding yet another layer of complexity and caution to their operations (Christensen & Laegreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2007). Therefore, while service design principles that promote iteration can be beneficial, they must be adapted to align with the institutional and legal frameworks governing PSOs. The challenge lies in balancing innovation with the need to uphold these obligations, ensuring that any iteration is careful and deliberate rather than rapid and flexible.

In view of these challenges, scholars emphasise the need for a nuanced understanding of the organisational and cultural factors influencing its successful implementation in the public sector (Gascó-Hernández & Torres, Reference Gascó-Hernández and Torres-Coronas2015). Furthermore, the measurement of outcomes and impacts remains a subject of ongoing research, with scholars exploring methodologies to assess the effectiveness of service design interventions in achieving their intended objectives (Demunter et al., Reference Demunter, Van Looy and Gemmel2019). Building upon this foundation, a recent study by Strokosch and Osborne (Reference 82Strokosch and Osborne2023) delves deeper into the application and implications of design approaches in public service settings. The authors carefully explore the focus and impact of design practice, marking a pivotal investigation into how human-centred design is operationalised within PSOs and its consequent effects on public service delivery (Strokosch & Osborne, Reference 82Strokosch and Osborne2023).

Ongoing research explores methodologies for evaluating outcomes and demonstrating the tangible benefits of adopting design principles in public service contexts. In summary, the scholarly literature on public service design underscores the significance of citizen-centric approaches, co-creation strategies, and the integration of digital technologies. Successful implementation requires attention to organisational and cultural factors, and ongoing efforts focus on refining evaluation methods to demonstrate the effectiveness and impact of public service design interventions.

1.3 Engagement as a Key Element of Service Design

Service design theory offers important insights for theory and practice as it creates a framework organisations can use to better understand and meet the evolving needs and expectations of their customers. Specifically, applying a service design approach allows those designing public services to uncover insights about customer preferences, pain points, and desires, which can then be used to create more meaningful and impactful services. Additionally, as service ecosystems become increasingly complex and interconnected, having a holistic understanding of how +different elements interact and influence each other is crucial for successful service innovation. From this perspective, service design theory is essential to service innovation because it brings ideas to life and creates a foundation for progress towards overall better services that more accurately and efficiently meet users’ needs.

These diverse perspectives demonstrate the evolution of service design theory from a basic approach to providing services towards a more experience- and user-centred framework. Today, service design theory is crucial due to its role in driving service innovation and value co-creation within service ecosystems. As service design has grown to be a user-centred, collaborative, and holistic approach, it has become instrumental in improving existing services and creating new ones. Embracing service design theory through a multidisciplinary lens has become a strategic imperative for both service researchers and practitioners.

1.4 Unveiling the Potential of Service Design for Value Co-Creation in Public Services

By framing public services as intricate ecosystems that integrate diverse resources, service design transcends the conventional focus on individual services to emphasise the overarching constructs of experience and context. Crucially, focusing on value co-creation processes serves as an important foundation for institutional change by incorporating the knowledge, skills, and backgrounds of diverse actors. Relatedly, this approach to designing public services acknowledges that services, even when carefully designed, undergo continuous adjustments. Applying design principles in public service contexts can significantly enhance the co-creation of value, provided there is a deep understanding of how various resources within a complex ecosystem integrate (Vargo & Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016; Grönroos, Reference Grönroos2019; Strokosch & Osborne, Reference 82Strokosch and Osborne2023). This approach shifts the focus from the provision of services to fostering service experiences and understanding the context in which these services are delivered (Jaakkola et al., Reference Jaakkola, Helkkula and Aarikka-Stenroos2015; Schwoerer et al., Reference Schwoerer, Kuehnl and Kuester2022). Recognising the processes of value co-creation is crucial for initiating the institutional changes needed to achieve the benefits associated with service design.

The term ‘Service’ refers to a value creation perspective, distinct from ‘services’, which denotes a specific product category requiring different design, production, and delivery approaches (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson2005). In SDL and SL, ‘Service’ represents the process of doing something beneficial with and for other actors, where value is co-created during use rather than produced and delivered as a finished product (Vargo & Lusch, Reference Vargo and Lusch2008, Reference Vargo and Lusch2016). Thus, value is co-created and context-dependent, shaped by the beneficiary’s experience and the social setting (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Tronvoll and Gruber2011). The following subsections further differentiate ‘service’ from ‘services’ by tracing key conceptual developments in SL and SDL, establishing the foundational elements of the service lens.

Service design captures the subjective and social dimensions of service, including the unique contributions of individuals’ knowledge, skills, and backgrounds. However, regardless of the initial design, services will inevitably be adjusted to meet the evolving needs and experiences of users, particularly in fields like education and healthcare, where empathy, equity, and fairness are paramount. The design process, adjustments, and resulting value are influenced by the service context, including institutional norms, societal values, and user expectations.

By prioritising experience and context, designing for service acknowledges the multifaceted nature of the value co-creation process.

Our contribution builds on and extends the PSL framework by clarifying the distinctions between ‘services’ as discrete offerings and ‘service’ as a dynamic, co-creative process, aligning with Trischler et al. (Reference Trischler, Røhnebæk, Edvardsson and Tronvoll2023) in advancing a more nuanced understanding of value co-creation within public service contexts. We contend that service design, woven into the fabric of interactions, plays a pivotal role in influencing design processes, service outputs, and the entire spectrum of service delivery. This holistic impact underscores the potential of service design to shape and enhance value accrual in the dynamic landscape of public services.

Service design theory offers valuable insights for the public sector that extend beyond the realm of service design. In the realm of public services, service design emerges as a pivotal strategy for value creation, aligning with the principles of PSL. Rooted in user-centredness, service design transcends traditional, product-centric approaches prevalent in the twentieth-century New Public Management (NPM) framework. Unlike the latter’s focus on internal efficiency and individual entities, service design’s methodology is built upon creativity, curiosity, and empathy. This paradigm shift emphasises the design of the ‘servicescape’ to not only satisfy immediate user needs but also create positive experiences that extend to long-term impacts on users’ lives and societal transformation.

Through participatory and inclusive practices, service design engages stakeholders in the public context, going beyond mere consultation to active co-design with citizens and service users. Service design’s emphasis on openness, participation, and inclusivity reflects a commitment to understanding and incorporating diverse perspectives, which is crucial for addressing complex social goals inherent in public service organisations. Despite challenges and cautions about implementation, service design in the public sector has the potential to foster innovation and an outcomes-focused approach, ultimately contributing to the creation of enduring societal value.

Service design theory plays a pivotal role in reimagining public services through its use of a user-centred approach and its emphasis on leveraging design principles to meet the dynamic needs and expectations of users, thereby acting as a catalyst for creating enduring societal value.

In summary, this section underscored the essential role of service design theory in understanding and improving public services. The adoption of a user-centred approach and the incorporation of design principles empower organisations to enhance service quality and encourage active citizen participation. Thus, service design theory, with its valuable insights and innovative frameworks, becomes a catalyst for creating services that align with the evolving needs and expectations of users.

2 The User-Centred Design Approach to Service Design

2.1 How Are Services Designed in the Public Sphere?

This section delves into the pivotal role of service design in fostering value creation, with a special focus on engaging citizens through innovative methodologies and exploring essential principles supporting service design adoption and implementation (Downe, Reference Downe2020). Central to this discussion is the application of the Double Diamond design process, a key feature of service design theory that underscores the importance of validating the need for a service before delving into its development to ensure it meets the users’ and organisations’ requirements.

The transformative impact of service design, especially evident during the pandemic’s shift towards digital business models, illustrates its critical role in addressing contemporary challenges. In some cases, this period also sparked conversations around sustainability, though these shifts were less uniform.

It underscores the necessity for service researchers to anticipate and mitigate unintended consequences, such as exclusions and environmental impacts, through collaborative efforts with public sector organisations, healthcare, non-profits, and design firms. This section proposes that the iterative nature of service design is essential for not only developing services that meet user needs but also emphasising the significance of service design in the creation of value through citizen engagement. Co-design actively involves citizens/service users and draws on their past experiences to generate fresh ideas and support improvement and innovation (Donetto et al., Reference Donetto, Pierri, Tsianakas and Robert2015; Schwoerer et al., Reference Schwoerer, Kuehnl and Kuester2022). Citizens/service users are invited to actively contribute as an essential resource throughout the design process, including idea generation and the development of solutions (Wetter-Edman et al., Reference Wetter-Edman, Sangiorgi and Edvardsson2014). Subsequently, there has been a discernible upswing in the utilisation of explicit co-design principles in public services over the past decade, with a growing number of applications grounded in the concept of co-design for value creation (Blomkamp, Reference Blomkamp2018; Dudau et al., Reference Dudau, Glennon and Verschuere2019; Nasi & Choi, Reference Nasi and Choi2023). Exploring the impacts of power differentials on co-design (Farr, Reference Farr2018) and delineating the linkages between co-design and social innovation (Voorberg et al., Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015; Whicher & Trick, Reference Whicher and Trick2019) have emerged as pivotal themes in this evolutionary trajectory.

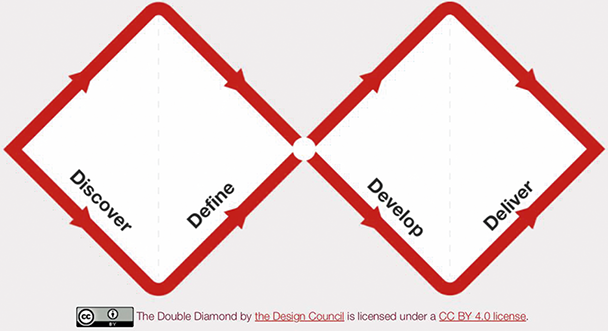

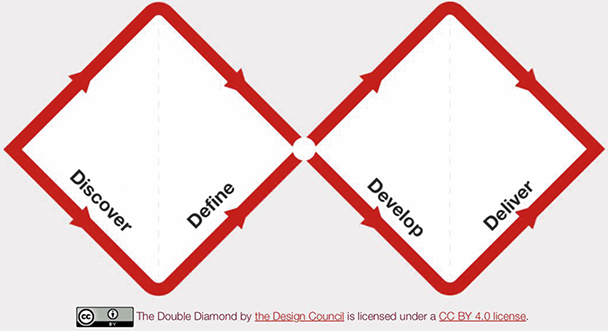

2.2 The Double Diamond: A Framework for Iterative and Inclusive Service Design

The Double Diamond design process originating from the Design Council in 2004 serves as a conceptual model elucidating the overarching stages traversed by numerous design innovation initiatives. This approach, notably adopted by the Scottish Government, emphasises an ethnographic methodology that draws heavily from service design theories, including the use of personas and other tools as key instruments for enhancing citizen engagement (Design Council, 2007; Scottish Government, 2019): ‘The design process reminds us that we have to be sure we’re creating the right thing before we can design something that’s fit for purpose and meets the needs of users, staff, or organisations’ (Scottish Government, 2019, p. 14).

The Double Diamond is a visual representation of the design and innovation process. It’s a simple way to describe the steps taken in any design and innovation project, irrespective of methods and tools used (https://www.designcouncil.org.uk).

The service design adopted by the Design Council presents a perspicuous, comprehensive and visually intuitive representation of the design process. Since its inception in 2004, the Double Diamond has garnered global recognition, with an extensive online repository of supporting research.

The Design Council’s utilisation of the Double Diamond effectively communicates a design process accessible to both experts in service design and non-experts. The two diamonds represent a sequential progression involving the expansive exploration of an issue (divergent thinking) followed by a focus on specific actions (convergent thinking). It is organised into the following four phases.

Divergent thinking characterises the Discover and Develop stages, encouraging designers to explore broadly whether to understand user needs and contextual dynamics in the Discover phase or to generate a wide range of possible solutions in the Develop phase (Brown, Reference Brown2008; Dorst, Reference Dorst2011). Convergent thinking, by contrast, underpins the Define and Deliver stages, where designers analyse and synthesise insights to clearly frame the problem and subsequently refine the most promising ideas into actionable solutions (Kimbell, Reference Kimbell2011; Bason, Reference Bason2017). This structured oscillation between expansion and narrowing supports creativity while maintaining strategic focus, making the Double Diamond particularly valuable in complex service contexts.

Discover (Exploration): This is the first phase of the Double Diamond process. It involves open-ended exploration and research. During this phase, designers seek to understand the users’ needs, motivations, and behaviours. This involves gathering insights and perspectives from a wide range of sources to fully comprehend the problem or challenge at hand. Techniques such as user interviews, observations, and focus groups are typically employed. The goal is to gather as much information and as many insights as possible without immediately seeking solutions.

Define (Creation): In this phase, the focus shifts from exploration to synthesising the gathered information to define the core problem(s) that need to be solved. This involves analysing the data collected in the Discover phase and identifying patterns, trends, and insights. Designers aim to articulate the problem clearly and succinctly, often in the form of a problem statement or a design brief. This phase is critical as it sets the direction for ideation by providing a clear and focused problem to solve.

Develop (Reflection): Here, the process opens up again into a phase of ideation and conceptualisation. With a clear understanding of the defined problem, designers begin to generate a range of ideas and potential solutions. This phase encourages creativity and the exploration of many different possibilities, using techniques like brainstorming, sketching, and prototype development. The aim is to explore a wide variety of solutions without immediately judging or dismissing them.

Deliver (Implementation): The final phase focuses on refining and testing the developed ideas to deliver effective solutions. It involves selecting the most promising ideas from the Develop phase and transforming them into practical and viable solutions. This often includes creating prototypes, conducting user testing, and iteratively improving the solutions based on feedback. The Deliver phase culminates in the final solution that can be implemented or launched.

Throughout the Double Diamond, the emphasis is on moving from a broad understanding of a problem space (diverging) to a focused and actionable solution (converging), thus ensuring a thorough exploration and validation of ideas and solutions. The process is inherently non-linear, a characteristic illustrated through the directional arrows present in Figure 1. Various organisations have observed that this approach often facilitates the uncovering of profound insights into fundamental issues, compelling a cyclical return to the formative stages of the process. The initiation and evaluation of preliminary ideas are integral components of the discovery phase, reflecting the principle that within the constantly evolving digital milieu, the concept of a ‘completed’ idea is obsolete. Feedback on the efficacy of services is systematically solicited and employed in an iterative cycle of enhancement based on the insights provided.

Figure 1 The Double Diamond

The Double Diamond can be used to navigate through a comprehensive process that encompasses the identification of needs, articulation of problems, formulation, and evaluation of solutions and the achievement of tangible outcomes and value. This process orchestrates user engagement, thus facilitating a fluid transition between the expansive exploration of broad concepts and the focused refinement of specific solutions. The construct of the first diamond serves a pivotal role in guiding the identification of the most pertinent challenges, ensuring a thorough comprehension of end-user requirements. Following this, the second diamond provides a structured framework for the design, enhancement, and realisation of the envisioned solutions, employing prototyping, and testing with both end-users and service providers to validate and refine the solutions.

The Double Diamond underscores the essence of service design as a dynamic and iterative process that is not merely focused on the creation of products and services but also dedicated to the cultivation of meaningful and impactful experiences that resonate with the complex and changing needs of users and stakeholders.

2.3 Placing the User’s Experience at the Heart of Public Service Delivery

This subsection discusses various service design methods employed for gathering information crucial to the development of public service system designs. Specifically, the focus is on assessing the efficacy of these methods in addressing the dual challenges of managing the complexities within service systems and comprehending user experiences. Drawing on established literature (e.g. Bitner et al., Reference Bitner, Booms and Tetreault1990; Edvardsson & Roos, Reference Edvardsson and Roos2001), we explore the application and effectiveness of some prominent service design techniques commonly employed in service design projects (Kimbell & Seidel, Reference Kimbell and Seidel2008; Diana et al., Reference Diana, Pacenti and Tassi2009; Segelström, Reference Segelström2009; Stickdorn & Schneider, Reference Stickdorn and Schneider2010; Zomerdijk & Voss, Reference Zomerdijk and Voss2010). Additionally, given their widespread usage in service design, a detailed analysis of these service design techniques is presented. To establish a foundation for the analysis, in this context, a service is defined as ‘something that assists individuals in accomplishing their necessary tasks’ (Down, Reference Downe2020).

Drawing on research by Trischler and Scott (Reference Trischler and Scott2015), Trischler et al. (Reference Trischler, Dietrich and Rundle-Thiele2019) and Popli and Rishi (Reference Popli and Rishi2021), it is imperative to prioritise the user’s experience in public service delivery. This entails embracing service design methods and frameworks that actively involve users as co-producers.

Service design employs a broad array of tools and methodologies to create and improve services that cater to the intricate requirements of users and stakeholders alike (Stickdorn & Schneider, Reference Stickdorn and Schneider2010). This vast toolkit encompasses various approaches, each designed to tackle distinct aspects of service design, from understanding user needs to prototyping and testing service concepts. In this subsection, we will introduce only a select few of these tools, focusing on the most popular and widely adopted approaches to service design (Kimbell & Seidel, Reference Kimbell and Seidel2008; Diana et al., Reference Diana, Pacenti and Tassi2009; Segelström, Reference Segelström2009; Stickdorn & Schneider, Reference Stickdorn and Schneider2010; Zomerdijk & Voss, Reference Zomerdijk and Voss2010). These methodologies, such as end user persona development, customer journey mapping, and service blueprints, are fundamental in facilitating a deep understanding of the service experience, allowing service design scholars and designers to craft solutions that are both innovative and user-centred. By employing these tools, a holistic and empathetic approach to developing services that genuinely meet the needs and expectations of their users can be ensured.

Persona development: The persona development concept, rooted in human-computer interaction research, emerges as a crucial mechanism for translating abstract customer segments into considerations based on individual perspectives. Defined by Cooper (Reference Cooper1999) as ‘fictitious, specific, and concrete representations of target users’, underscoring that their development is grounded in research rather than arbitrary invention, personas furnish a memorable and actionable framework. Personas are based on composite archetypes and help designers empathise with users’ needs, behaviours, and motivations (Pruitt & Adlin, Reference Pruitt and Adlin2006; Stickdorn et al., Reference Stickdorn, Hormess, Lawrence and Schneider2018). While demographic details such as age or occupation may provide contextual grounding, effective personas prioritise psychographic attributes such as attitudes, goals, frustrations, capabilities, and behavioural patterns – because these factors shape how users experience and interact with services (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2009). Emphasising psychographics allows personas to capture the lived realities of service users and support the design of experiences that are both meaningful and context-sensitive. Personas serve as an invaluable resource for concentrating on the primary user by elucidating behaviour patterns and pinpointing user needs. The utility of personas extends beyond this focus, facilitating communication among stakeholders, informing decision-making processes, and providing a basis for evaluating concepts, as acknowledged by both academics and professionals (Pruitt & Adlin, Reference Pruitt and Adlin2006; Mulder & Yaar, Reference Mulder and Yaar2007). They assimilate contextual information pertinent to service challenges, capturing the requirements, needs, or desires typically associated with the persona, and are enriched with ‘softer’ details like personality traits to offer a more nuanced and personalised portrayal. The crafting of personas is fundamental in making the abstract notion of user bases tangible, thereby facilitating empathy and tailored engagement with specific user segments. Through the integration of demographic, psychographic, and behavioural insights, personas act as a guiding structure, enriching the process of developing solutions that resonate with user needs and expectations. Most personas are developed from research insights which are usually gathered from interviews and focus groups (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2011).

Personas help designers understand the diverse needs, behaviours, motivations, and challenges of different segments of the population. They are a design tool used to construct representative archetypes of the intended user groups for whom a service is being developed (Pruitt & Adlin, Reference Pruitt and Adlin2006; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Reimann, Cronin and Noessel2014). To ensure their effectiveness, personas must be grounded in empirical research and crafted to reflect the diversity, inclusivity, and variability of real users’ experiences, avoiding stereotypes, and oversimplification (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2009; Stickdorn et al., Reference Stickdorn, Hormess, Lawrence and Schneider2018).

Here is an example of its application to the redesign of a Municipality Social Service Website. Imagine a local government wanting to redesign its online social services portal, which offers resources for employment, housing assistance, healthcare, and more. The portal is currently difficult to navigate, resulting in underutilisation by residents who need these services most. To improve the portal, the government could apply the personas methodology. Firstly, it is essential to gather data about the residents who use (or need to use) the social services portal. This could include an assessment of the user behaviours of the current website. To map needs and perceptions of satisfaction, it could also include assessments based on surveys and interviews with residents and users as well as focus groups with key population segments (e.g. seniors, low-income families, people with disabilities) as well as meetings with social service workers and community advocates.

Based on this research, it is possible to create a set of personas that represent the different types of users who will interact with the portal. Here are three examples of personas that could be used in this context such as a single mother named Mary, a retired citizen named John and Saman a recent immigrant with physical disability. For each of them it is important to depict their profile (e.g. Mary is a single mother of two, working a part-time job while juggling childcare. She has minimal free time and limited access to the internet, relying on her smartphone for most online services); goals (e.g. Mary wants quick access to housing assistance and affordable childcare services); challenges (e.g. Mary struggles with complex forms, lengthy application processes, and finding specific information on the portal. She often abandons the process halfway through because of time constraints) and needs (e.g. a mobile-friendly, easy-to-navigate interface with simple, clear instructions, and the ability to save applications to complete later).

Using these personas, the design team makes informed decisions about the portal’s layout, content, and features that can be tested with a small group of users representing each persona. Feedback is gathered, and adjustments are made to improve the service, ensuring it meets the community’s real needs

Customer journey mapping: Customer journey mapping is a vital tool that helps visualise user interactions and experiences throughout the service journey. It emphasises active stakeholder involvement in identifying pain points and areas for improvement, ultimately leading to user-centred design decisions. Furthermore, Customer journey mapping encourages cross-functional collaboration, thereby fostering alignment among stakeholders by establishing a shared comprehension of the service ecosystem. Visualising and mapping techniques play a crucial role in rendering service systems and processes more transparent. They clarify which components of the service system impact the overall user experience (Patricio et al., Reference Patrício, Fisk, Cunha and Constantine2011). The relevance of customer journey mapping is underscored by its ability to comprehensively capture the user’s experience throughout their journey and highlight the ‘touchpoints’ within the service system (Zomerdijk & Voss, Reference Zomerdijk and Voss2010). Active involvement of consumers in the analysis and design processes, as advocated by Sanders and Stappers (Reference Sanders and Stappers2008) and Ostrom et al. (Reference Osborne2010), is essential for fully integrating user experiences and gaining valuable insights. Collaborative design workshops have been effectively employed as part of these visualisation and mapping techniques to facilitate participants’ sharing of their experiences and the generation of innovative concepts (Bason, Reference Bason2010; Steen et al., Reference Steen, Manschot and De Koning2011).

For example, in redesigning an unemployment benefits service, a journey map follows a user like Rachel, who is a typical persona (e.g. she is a 45-year-old office worker who has just lost her job). The key stages in Lena’s journey to access unemployment benefits are identified as follows: awareness (e.g. Learning about the unemployment benefits programme); application (e.g. Applying for benefits); approval/denial, receiving benefits and reintegration (e.g. using resources to find new employment). Through customer journey mapping, the service designer understands the challenges she faces in accessing the service, such as difficult-to-find information, complex forms, long waiting times, and unclear payment processes. The map leads to improvements like clearer information architecture, simplified application forms, better communication, and integration with job placement services.

Service blueprinting: A service blueprint is a visual and systematic representation of a service that helps organisations comprehensively analyse and design service processes. It maps out the entire service journey, illustrating customer interactions, frontstage activities, backstage processes, and support systems involved in service delivery. This blueprinting process is crucial for identifying potential pain points, improving efficiency, and enhancing the overall customer experience. As described by Shostack (Reference Shostack1984), a pioneer in service blueprinting, it is a method to ‘chart the sequence of events and interactions in a service process’. This involves delineating customer actions, frontstage and backstage processes, support processes, and physical evidence encountered during service delivery. Bitner et al. (Reference Bitner, Ostrom and Morgan2008) emphasise service blueprinting as a ‘practical technique for service innovation’, highlighting its utility in fostering innovation and improving service design. The technique aids in identifying touchpoints, understanding customer emotions, and aligning various components to deliver a seamless and efficient service. Service blueprinting serves as a valuable tool for organisations to visually map and analyse their service processes, leading to enhanced service delivery and customer satisfaction. It helps to reveal the process behind critical service elements that define the user experience (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2011).

2.3.1 Exploratory and Confirmatory Focus Groups

Building on the methodological foundation presented thus far, we also include Tremblay and colleagues’ (2010) framework based on exploratory and confirmatory focus groups (EFGs and CFGs, respectively) as it presents a robust methodology that has been widely used over the past years for the refinement of artefact design. It can also be adapted for service design, particularly in the context of re-designing services. This adaptation leverages the iterative nature of EFGs and the validating strength of CFGs to enhance the user-centred design process, ensuring that services not only meet user expectations but also enhance user experiences in meaningful ways.

In their original development in design research (Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Hevner and Berndt2010a), EFGs serve to provide critical feedback that informs modifications of the artefact under study, while CFGs are used to demonstrate the utility of the artefact design in the application field.

Exploration and Creation Phase

In the realm of service design, EFGs can be utilised to gather in-depth insights into users’ experiences with existing services. This phase involves engaging with users to explore their perceptions, frustrations, and needs regarding a service. These discussions are pivotal for the following:

Uncovering insights: Facilitating the discovery of broad themes and users motivations

Identifying service gaps: Highlighting areas where the current service may fall short in meeting user expectations or needs.

Gathering contextual understanding: Providing a deeper look into the environmental and personal factors that influence user interactions with the service. In particular, the qualitative data gathered during these sessions are crucial to construct personas and generate hypotheses about how a service can be re-designed to better cater to its users.

The objective here is to uncover latent needs and opportunities for innovation that may not be immediately evident. Researchers can then synthesise these insights to propose tangible improvements or entirely new service concepts. This exploratory and creative phase is inherently iterative, with each session potentially unveiling new directions for refinement. Thus, through successive EFGs, a comprehensive understanding of user needs and service gaps can be developed, thereby guiding the subsequent design or re-design process.

Reflection and Implementation Phase

Following the exploration phase, CFGs are crucial for assessing the practical utility and user acceptance of the proposed service changes in real-world settings and for creating further ideas. The CFG participants are exposed to the re-designed service, either in prototype form or through detailed service blueprints, to evaluate its effectiveness, usability, and overall appeal. These focus groups should be structured to capture qualitative feedback on user experiences of specific aspects of the service design. These sessions are key to the following:

Testing re-design concepts: Validating whether the re-design ideas resonate with the target audience and address the issues identified in the exploratory phase.

Refining service propositions: Ensuring that the modifications proposed accurately reflect the user’s needs and align with their expectations.

Closing feedback loops: Identifying any overlooked elements in the re-design process and ensuring all user segments are adequately considered.

In Section 4 we use this methodology to help redesign the education services taking into account the feedback and the organisational analysis.

Running multiple CFGs with experientially distinct participant groups – such as a focus group of single mothers, another of retirees, or immigrants – enables the collection of diverse viewpoints, thereby enhancing the reliability and inclusiveness of the findings.

Adapting Tremblay and colleagues’ (Reference Tremblay, Hevner and Berndt2010b) approach to service design necessitates a flexible, yet systematic, process. Initial exploratory sessions should focus on understanding the user’s interaction with the service-identifying pain points and unmet needs. Insights from these sessions would then inform the development or refinement of service prototypes, which are then subjected to CFGs for validation. This cycle may be repeated several times, with each iteration refining the service design based on feedback until it meets the criteria for successful implementation in the field.

2.4 Benefits of Service Design Tools for Designing Public Services

The use of persona development, customer journey mapping, service blueprints, and focus groups in service design underscores their pivotal roles in achieving the following:

User-centred design: Both persona development and customer journey mapping champion a user-centred ethos, instilling empathy among designers and stakeholders (Brown, Reference Brown2008).

Holistic service understanding: The fusion of personas and journey maps engenders a holistic grasp of the service ecosystem. This comprehensive perspective empowers public managers and scholars to tackle challenges across various touchpoints, culminating in more effective service design (Meroni & Sangiorgi, Reference Meroni and Sangiorgi2011).

Enhanced collaboration: These tools act as catalysts for collaboration among cross-functional teams, providing a shared visual lexicon and unified comprehension of user requirements (Junginger & Sangiorgi, Reference Junginger and Sangiorgi2009).

Bias mitigation: When intentionally applied to reflect structurally disadvantaged user groups, such as low-income individuals or digitally excluded populations, these tools help surface inequities and design barriers, enabling practitioners to develop services that are more inclusive and less biased toward users with greater resources (Steen et al., Reference Steen, Manschot and De Koning2011; Le Dantec & Fox, Reference Le Dantec and Fox2015).

The tools and processes presented in this section are indispensable cornerstones of service design. They offer a structured, user-focused framework for crafting and enhancing services, and their integration forms a robust foundation for designing services that resonate with users, nurture empathy, and navigate the intricacies of the service landscape. As service design continues to evolve, these tools retain their fundamental role in shaping impactful services for users.

2.4.1 Service Design in Practice

In the following sections, we examine insights drawn from three distinct public service design projects that actively engaged users. These projects, set within the context of complex service systems, demonstrate the unique yet crucial role of service users as co-producers within these systems. Additionally, they highlight key actions that enhance the manageability of service systems while providing a concrete illustration of the service design methodology in practice. This exploration offers a deeper understanding of effective strategies for involving users in public service design endeavours. Furthermore, we address the critical issue of inclusivity in service design, acknowledging the potential biases favouring those with greater resources and offering practical guidance on how to mitigate these challenges. Collectively, these case studies contribute to the ongoing discourse framed by Public Service Logic (PSL) (see Osborne, Reference Osborne2010; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Radnor and Nasi2013; Radnor et al., 2015).

3 Redesigning Municipal Services to Create City Value in the Aftermath of COVID-19

The reverberation of the global pandemic has guided cities into an era of adaptation, compelling them to embrace new ways of living while grappling with the multifaceted challenges posed by the economic crisis. This juncture presents a unique opportunity to craft a long-term value proposition that transcends immediate hurdles as the pandemic-induced norms of social distancing, limited access to physical spaces and other COVID-19 restrictions have necessitated a profound re-evaluation of how citizens interact with institutions and service providers.

Furthermore, governments at various levels have found themselves contending with a slew of complex issues, ranging from economic and health concerns to welfare problems, unemployment, and a decline in competitiveness. These challenges have had a particularly pronounced impact on local governments, with some struggling to adapt to the evolving landscape. Certain local authorities continue to rely on fragmented, non-digitised processes, placing additional coordination burdens on citizens seeking essential services. Recognising that municipal resources alone may prove insufficient to drive recovery and long-term economic development within the confines of traditional government-citizen dynamics, this case study helped identify solutions that empower municipalities to adapt their city services in a post-emergency context. Specifically, the overarching aim of this case was to offer recommendations for how cities can implement a rapid and flexible recovery, thereby seizing the opportunity to implement transformative service redesign. It sought to accomplish this by assessing shifts in city priorities, expectations and public service satisfaction and subsequently proposing improvements to government operations.

The research unfolded in two primary stages:

1. Assessment of the current context: In this initial phase, a thorough investigation into the existing conditions was conducted, identifying the needs, capabilities, priorities, and perceived value within urban environments. Desk research and interviews with key stakeholders and users were utilised. This comprehensive exploration served as the foundation for understanding the current service landscape and identifying areas for innovation and redesign.

2. Development of strategies for service redesign: The second phase focused on crafting practical suggestions aimed at service redesign. These recommendations emerged from qualitative analyses and insights drawn from focus groups comprised of public administrators and citizens.

By dividing the research into these components, our aim was to not only diagnose the current state of urban services but also propose forward-thinking, actionable strategies for service redesign. This approach positions cities to not just recover from challenges but to evolve their service offerings, making them more responsive, and aligned with the needs and aspirations of their citizens.

This study focuses on a big southern European municipality – a historical capital – heavily struck by the lockdown measures. It is characterised by extraordinary cultural and artistic values and a robust tourism-based sector. Moreover, it released one of the earliest post-pandemic urban strategies. This empirical analysis hinges on the evaluation and evolution of the citizens’ expectations of and satisfaction with municipal services before and after the pandemic’s two initial waves, spanning from March 2020 to October 2020, coinciding with the commencement of the vaccination campaign in January 2021. Key findings emerged from this research, including a preference among citizens for engaging with government services online, especially when professional assistance is available. Furthermore, increased satisfaction with online services during the pandemic underscores the need for digital readiness and redesign in certain policy areas, such as mobility. Exploring the interplay between expectations, performance, and satisfaction revealed that the citizens most satisfied with a specific public service are those who have their expectations managed effectively and subsequently experience superior service performance. This underscores the importance of clear and transparent communication regarding service expectations. Lastly, the research highlighted the potential benefits of co-design and co-delivery in facilitating a mutual understanding of expectations and organisational feasibility, ultimately streamlining the redesign process.

In the following subsections of this section, we provide an in-depth exploration of the study’s background, the methods employed, and the insights derived from our research findings.

3.1 Research Context

Governments aim to enhance public well-being and meet stakeholder expectations through actions such as regulation, service delivery, policy formulation, and public goods provision (Bellé et al., Reference Bellé, Belardinelli, Cucciniello and Nasi2023). Historically, most governments have failed to assess the value they create with citizens and involve them in service design (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Radnor and Nasi2013; Nasi et al., Reference Nasi, Osborne, Cucciniello and Cui2024). Additionally governments often struggle to govern the nexus between objectives, needs and outcomes (Knapp, Reference Knapp1984).

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a debate on the value of government services as local governments grappled with changing citizen expectations and priorities shaped by the new daily routines. To meet such expectations, governments have to comprehend the evolving context in terms of needs, capacity, preferences and value, ensuring consistency with the existing status quo while making necessary adjustments. This process entails recognising and supporting changes in value rather than inventing entirely new solutions.

3.1.1 Assessing Value through Citizen Satisfaction

One way to gauge the value of government services is by evaluating citizen satisfaction. The importance of citizen satisfaction gained prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s, coinciding with the growth of instruments such as the Service Quality Model SERVQUAL, which was used to measure customer satisfaction in service industries (Bouckaert & Van de Walle, Reference Bouckaert and Van de Walle2003). Several scholars (i.e. Van Ryzin, Reference Van Ryzin2015) explored the relationship between expectations, satisfaction, and overall community judgment, arguing that the quality and outcomes of government services significantly influence citizens’ subjective evaluations of their community as a desirable place to live, thereby impacting residence and relocation decisions.

The COVID-19 pandemic reshaped citizens’ expectations and behaviours due to the restrictions and new practices it gave rise to. Public services designed to address immediate challenges, such as social distancing and limited physical access, may now no longer suffice. They may also fail to meet the evolved expectations that have arisen in the post-pandemic context (Vargo, Reference Vargo2008). Consequently, understanding how citizens’ expectations evolve is crucial for local governments to redesign services, allocate resources, and innovate to meet citizens’ needs.

3.1.2 Challenges of Meeting Diverse Needs

Local governments must cater to a diverse population with heterogeneous needs, making one-size-fits-all solutions impractical. Designing services that align with evolving expectations is complex due to the challenge of envisioning end-to-end experiences from multiple stakeholders’ perspectives. Service design emerges as an innovative approach to improving the quality of services, programmes, and policies considering expectations, satisfaction, and feasibility (Clarke & Craft, Reference Clarke and Craft2018). Service design was traditionally limited to engineering and architecture but has recently expanded into a multidisciplinary field that incorporates insights from psychology, cognitive sciences, and anthropology. It focuses on the user experience of citizens and providers, encourages early experimentation and prototyping to prevent later failures, and prioritises value delivery. In the context of public services, service design involves creating user-centred products, services, solutions, and experiences (Bason & Austin, Reference Bason and Austin2019).

3.1.3 Co-Design and the Creative Process

Service design fosters user participation to create new forms of value through co-design. Service design acknowledges the absence of well-defined problems and embraces divergent thinking to generate multiple ideas, followed by convergent thinking to refine and select the best solution. To this end, qualitative techniques, such as ethnographic research, service journeys, participant observations and prototyping, are used to facilitate user-centred problem-solving. To consolidate the design process and community involvement, a critical appraisal of service design methods is essential.

Thus, this study employs a range of methods to frame its background, assess citizen expectations and satisfaction with public services pre- and post-COVID-19, and deepen the understanding of the human experience of both citizens and providers. These methods and tools inform recommendations for service redesign.

3.2 Methods

We used service design tools to deepen insights into both citizens’ and providers’ experience with services. In doing so, we gained a better understanding of user expectations, the user journey, and organisational processes. This information allowed us to formulate recommendations to redesign the services that create value for their users.

A research methodology combining focus groups and directed observational studies was selected for its interactive nature. Importantly, the methodology adopted a systemic and holistic view, acknowledging and incorporating complexity, chaos, ambiguity, fuzziness, and dynamic forces rather than simplifying them for analytical ease (Gummesson, Reference Gummesson2006). This was particularly relevant for our research, where the complexity and uncertainty were heightened due to the numerous interactions between users and service providers (Sparks, Reference Sparks2001). Therefore, this method was deemed most suitable for the depth and breadth of analysis required in this study.

3.2.1 Understanding the User through the Use of Personas and Focus Groups

Personas were developed from in-depth interviews with eight citizens. The interviews focused on identifying perceived differences in service provision that might influence citizens’ experiences. The identified differences resulted from the clustering of the selected data’s relevant themes (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). The insights derived from the in-depth interviews provided an understanding of the service user’s background from a broader real-world perspective. The insights that were derived from the interviews were related to the specific service system to be analysed.

Building on this methodological foundation, we applied Tremblay and colleagues’ (Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Hevner and Berndt2010a) framework for utilising EFGs and CFGs as it presents a robust methodology that has been widely used over the past years for the refinement of artefact design. By adapting EFGs and CFGs within the service design process, organisations can ensure that their services are not only innovative and user-centred but also validated through rigorous user engagement. This approach aligns closely with the principles of user-centred design, emphasising the importance of understanding user needs and validating solutions through iterative development and testing.

The careful distinction between EFGs and CFGs aligns with our approach of embracing complexity and avoids oversimplification. For both types of focus group, a meticulously crafted script was developed, ensuring that each focus group’s unique objectives were effectively met and that the insights generated were both relevant and robust.

Two methods were used to recruit participants for the interviews and focus groups. To recruit citizens and entrepreneurs, we used the municipality’s Facebook page. We collected information and selected participants who are (i) aged between 18 and 64, (ii) residing in the central area of the municipality, (iii) unemployed, self-employed, or employed and (iv) working in the mobility industry (i.e. taxi drivers, mobility managers, etc.). Each citizen was offered transportation reimbursement for their travel to the focus group site and an Amazon Gift Card of €25 in value. As for public managers for the focus groups, we recruited those who are (i) engaged in delivering the service to citizens, (ii) engaged in mobility services, and (iii) engaged in the management of the Information Technology (IT) services for digital services. No compensation was offered to the recruited public managers.

All the focus groups were conducted in person while respecting the COVID-19 restrictions in place at the time of data collection. Before starting each focus group, the moderators introduced the project, explained the objectives, and provided general information about the focus group. We conducted a total of two Exploratory Focus Groups (EFGs) and one Confirmatory Focus Group (CFG), involving three panels of participants. The first panel included eight citizens, some of whom were entrepreneurs living and investing in the city; the second panel consisted of six public managers. Finally, a confirmatory panel was held, comprising six citizens and six public managers.

The scripts were prepared in advance in Italian to address the key questions of the study, which were designed to deepen our understanding of expectation and satisfaction with services and consequently identify strengths and challenges to address in case of the redesign.

The focus group discussions were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. The transcripts were analysed using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). We utilised Dedoose version 7.6.17 (www.dedoose.com). In the following, we draw illustrative examples from each transcript (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell1998): short quotes are used to support specific points of interpretation and longer quotes are used to convey a sense of the original discussions.

3.3 Findings

3.3.1 Understanding Users’ Needs and Ideas to Innovate Service Opportunities

The exploratory and confirmatory focus groups conducted with citizens, entrepreneurs, and public managers revealed key shifts in service expectations and user experiences in the post-COVID 19 context. The findings are organised around three pivotal factors influencing the evolving user journey:

(1) a revised schedule of daily routines,

(2) the widespread adoption of smart working practices, and

(3) the customisation of services to address concerns around health, access, and inclusion.

(1) A Revised Schedule of Daily Events: Shifts in Routine and Service Use Patterns

In the first exploratory focus group, conducted with citizens – some of whom were entrepreneurs – participants were asked what factors they consider when deciding where to live. Following individual brainstorming, their answers were categorised into five areas: (i) nature and environment (e.g. climate, open-air spaces for walking or training), (ii) job opportunities, (iii) cultural heritage and offerings, (iv) the area’s human scale and social capital, and (v) services (especially health, mobility, and education).

When discussing services, participants focused on quality and accessibility. They expressed a preference for modern, user-friendly channels of interaction that reflect the diverse needs of target users. Examples included digital services accessible to older adults with limited tech skills, booking systems usable by people with visual impairments, and clear information formats for users with cognitive challenges. One participant described what they expect in terms of healthcare quality:

‘I expect access to professionals with the right competencies and a multi-disciplinary vision of a health problem … I expect professionals to listen to the patients, to their questions and needs.’

Another highlighted the importance of evidence-based decision-making in service provision:

‘Through technology and data management, health professionals should innovate their decisions about diagnosis and therapies. Data is interconnected, and it should be used properly.’

A third emphasised usability:

‘I don’t want to queue to pay for services, including healthcare services … It has to be easy for the user to access a service and go through its delivery process.’

In mobility, participants generally appreciated the variety of transport options in the city. However, they identified major usability challenges. One participant commented:

‘I would always use my bike, but the metro construction sites, traffic, pollution and the lack of adequate bike lanes make it too dangerous to consider it as a main means of transportation.’

Another pointed to poor intermodality:

‘I now want to ride my car everywhere, but it’s hard to find a parking spot. I would switch to other means of transportation. Individually they are all good, but interconnectivity among them is still very limited.’

Participants noted that all urban transport modes – bikes, motorcycles, buses, taxis, and private cars – use the same roads, creating congestion and infrastructural degradation. The current system, described as a static backbone, lacks the flexibility to adapt to emerging needs.

Public managers confirmed these changes. They highlighted, for instance, that taxi usage had shifted from being dominated by business travellers and tourists (over 50 per cent of rides pre-COVID) to broader citizen use, creating demand for lower prices and changes in peak-hour service patterns. They also noted the limited capacity of public transportation and its rising operational costs due to altered school and business hours and the need to deploy additional transport options, such as converting tourist buses into school buses.

(2) The Widespread Adoption of Smart Working and Its Implications

Participants identified smart working as a major factor shaping both housing needs and expectations of service delivery. While most citizens agreed that the city had improved over time, they voiced concerns about rising inequality. One concern was housing affordability – ‘housing may become too expensive for some citizens’ – which may lead to exclusion from the city.

Another participant linked housing conditions to the inadequacy of home spaces for new work and life routines: ‘A two-bedroom apartment for a family of four to five people did not offer adequate space for studying and working.’

This highlighted the impact of smart working and lockdowns, which forced many families to adapt to confined and ill-equipped domestic environments. Public managers similarly acknowledged that citizens’ routines had changed. One noted:

‘COVID has taught us the importance of capillarity of services. Once the first wave of COVID-19 hit the city, we had to close down all the offices but the central one. Fortunately, most register’s office services were digitised, but some target groups were not capable of accessing online services, and we cannot afford to leave anyone behind.’

They observed that even young citizens may be digitally excluded if living in poverty:

‘Even a young citizen with a critical poverty situation is not able to access online services.’

Participants also suggested flexible service models adapted to these changing routines. Ideas included dynamic bus sizes for peak and off-peak hours, intelligent traffic systems to manage flow, and integrated solutions enabling seamless inter-mobility across local, regional, and national services.

(3) Customisation of Services to Address Concerns around Health, Access, and Inclusion

Participants stressed the importance of services that are responsive to real, complex user conditions, especially in digital service delivery. They generally praised the city’s online mobility parking pass system for its clarity and ease of use for ‘standard’ users, that is, municipal residents with privately owned vehicles. However, frustrations emerged when dealing with non-traditional use cases.

One such case, explored in the Confirmatory Focus Group, involved a resident using a car registered to a nonresident family member. Others involved leased cars or company-owned vehicles. These situations exposed limitations in the design logic of the digital service, which was built on the assumption that service users are residents who own their cars.

This misalignment led to reduced satisfaction and increased friction. The issue was further compounded by the absence of coordinated databases linking residency, ownership, and license plate registration. As one participant summarised: