Introduction

Media and Information Literacy (MIL) is fundamental for understanding the role of the media in society, both traditional and digital, in order to promote the critical consumption and responsible production of information (Wuyckens et al., Reference Wuyckens, Landry and Fastrez2022). According to Qerimi et al. (Reference Qerimi, Jahiri, Ujkani and Zeneli2023), addressing this issue is crucial as it enables young people and children to assess the credibility of the information and content they interact with online, which is proliferating exponentially every day, and to protect themselves from risks such as cyberbullying and other emerging phenomena within the media ecosystem.

In addition, Morduchowicz (Reference Morduchowicz2022) highlights that MIL has the potential to teach them to use information and communication technologies to tell their own stories and share their perspectives. In particular, marginal communities, or those who have been traditionally silenced, can find a powerful tool in this type of education to make their voices heard, and to have an influence on public discourse. Therefore, Mateus (Reference Mateus2021) argues that integrating MIL in education systems provides students with skills for personal and professional development, fostering an aware, resilient, and participative society.

In this context, Media Competence (MC) refers to a set of specific skills and knowledge that people develop as a result of MIL, such as the ability to utilize various communication platforms and understand their socioeconomic impact, the competence to create and distribute messages across different formats and channels, and the critical analysis of how media messages reflect and construct ideologies (Trültzsch-Wijnen, Reference Trültzsch-Wijnen and Trültzsch-Wijnen2020). A set of MIL education policies includes adding MC in the school curriculum, and the training of teachers so that they can teach it, by providing resources (King, Reference King, Fastrez and Landry2023). These policies also seek to guarantee the equal access to technology and information through initiatives to reduce the digital divide, ensuring that all communities have internet access and technological devices, through technological infrastructure at public schools and libraries (Daskal, Reference Daskal, Frau-Meigs, Kotilainen, Pathak-Shelat, Hoechsmann and Poyntz2021). For Grizzle et al. (Reference Grizzle, Moore, Dezuanni, Asthana, Wilson, Banda and Onumah2013), the formulation of policies in this area requires a comprehensive approach that considers a broad spectrum of actors working in a network. In this sense, not only do teachers play a crucial role, but so do education authorities, academia, and Civil Society Organizations (CSO), whose collaboration guarantees a sustainable implementation, as each of them performs a fundamental function (Rojas-Estrada et al., Reference Rojas-Estrada, Aguaded and García-Ruiz2024): a) the authorities and policy makers are responsible for creating regulatory frameworks and assigning the necessary resources; b) academics contribute with innovative research and pedagogic methods; c) media and the private sector can provide educational content and promoting the responsible consumption of media, and d) the CSO offer training programs, educational resources, and technical support.

Thus, the aim of the present study is to examine the perception of people working within CSO on the integration of MC in the curriculum of basic education (early, primary, and secondary school) in Latin American countries, encompassing three main areas: a) reach and content, b) key actors and relevant actions, c) opportunities and challenges. The objective is to make visible the role of entities in the promotion of media education, identifying possible areas of collaboration that can guide more efficient education policies and programs that are adapted to the needs of society, in terms of media and information.

Civil Organizations as a Key Piece in the Promotion of MIL

According to Johansson and Uhlin (Reference Johansson and Uhlin2020), CSO are defined as non-governmental and non-profit organizations that operate to promote social well-being, defend human rights, promote social change, or perform beneficial activities, among other objectives. In the area of the promotion of MIL, these entities tend to play a significant role, not only when complementing governmental actions, but also when offering a series of advantages for the promotion of this type of education, which include a variety of approaches, a close proximity to the community, ability to innovate, mobilization of resources, and the promotion of citizen participation (Frau-Meigs & Torrent, Reference Frau-Meigs and Torrent2009). On its part, the Paris Declaration on Media and Information Literacy in the Digital Age of the UNESCO (2014) underlines the importance of the CSO and their crucial role as “bridges” between diverse actors, aside from highlighting their ability to reach disadvantaged groups and provide continuous support throughout life.

In this context, the study by Kanižaj (Reference Kanižaj2017), which is centered on examining the role of CSO in the promotion of MIL in the European Union, highlights Croatia as a notable example. In this country, the “Društvo za komunikacijsku i medijsku kulturu” (Society for Communication and Media Culture) and the project “Djeca Medija” (Children of media) have incorporated essential elements in their work plans, such as active volunteering, awareness in the scientific community, the collaboration with other organizations as a prerequisite for conducting research, and the mobilization of grassroots support, aside from actions of political influence to promote media education.

In the USA, entities such as the “Center for Media Literacy” (CML), “National Association for Media Literacy Education” (NAMLE), and “Media Literacy Now” collaborate closely with educational and governmental entities to develop and promote MIL resources (Herdzina & Lauricella, Reference Herdzina and Lauricella2020). In Canada, since 1996, “MediaSmarts” has contributed significantly to media education, focusing on education, public awareness, and research and policy, facilitating collaborations and promoting policies to improve public access to media information (Kirkland, Reference Kirkland2021). In Turkey, the RTUK, responsible for telecommunications, suggested the integration of MIL in the curriculum of the platform “Stop the Violence,” involving public companies, CSO, and universities. Asrak-Hasdemir (Reference Asrak-Hasdemir2016) is the first step that mobilized the collaboration between academia, the government, and the CSO with respect to this subject, defining Turkey as a pioneering case in this educational policy.

At the regional level, institutions such as the “Media Literacy for Citizenship” (EAVI) which operates in European Union countries (Celot, Reference Celot2020) or the “Euro-American Inter-university Research Network on Media Skills for Citizens—Alfamed Network” (Alfamed, 2024), are networks of professionals, academics, and CSO representatives dedicated to the promotion of MIL. The main aims of these types of organizations are to promote research, facilitate cooperation, and promote the exchange of good practices in media education.

In the specific context of Latin America, according to Nelson-Mármol (Reference Nelson-Mármol2010), one of the pioneer organizations in the work related with the appropriation of ICT in education processes has been the “Asociación Católica Mundial para la Comunicación” (SIGNIS World Catholic Association for Communication), through their work network on educommunication. Also, in agreement to Garro-Rojas (Reference Garro-Rojas2020), in most of the countries in the region, progress in the area of the MIL has been mainly promoted by the actions performed by these entities. In this sense, a research study conducted by Pegurer-Caprino et al. (Reference Pegurer-Caprino and Martínez-Cerdá2016) in Brazil, centered on the analysis of the objectives of diverse MIL-related initiatives promoted by CSO, underlines the importance of considering the accumulated experiences of these entities, which go beyond the formal education setting, to guide the formulation and implementation of policies on this topic. Therefore, the present study seeks to discover the perspective of CSO representatives regarding the curricular integration of MC, which would allow for the formulation of more inclusive and effective education policies.

Method

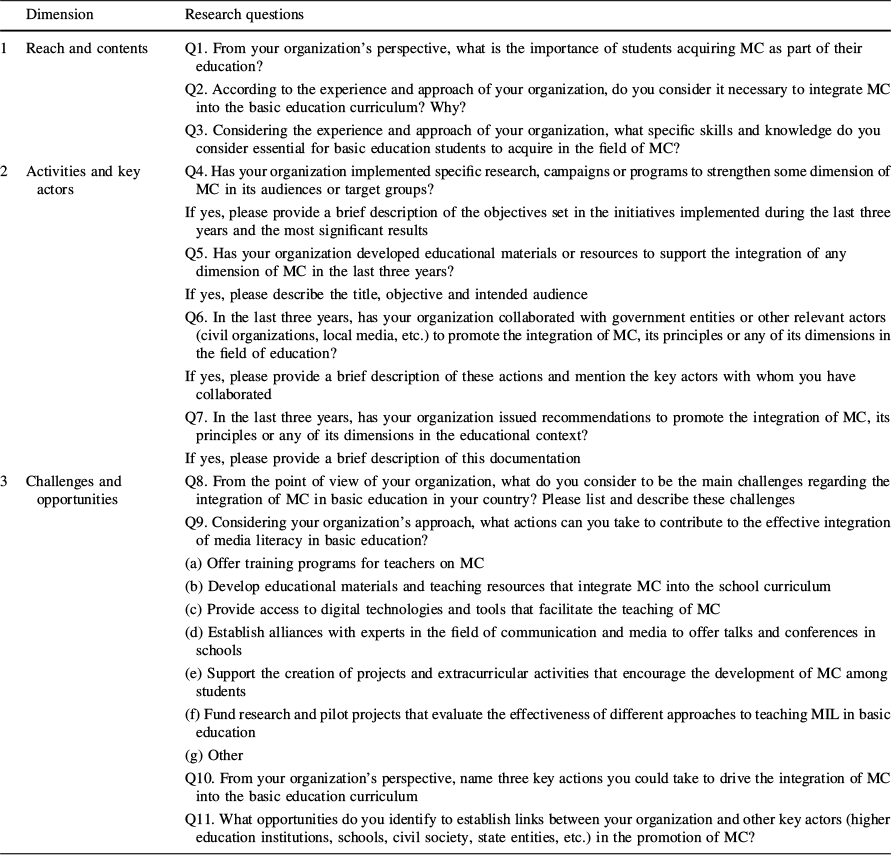

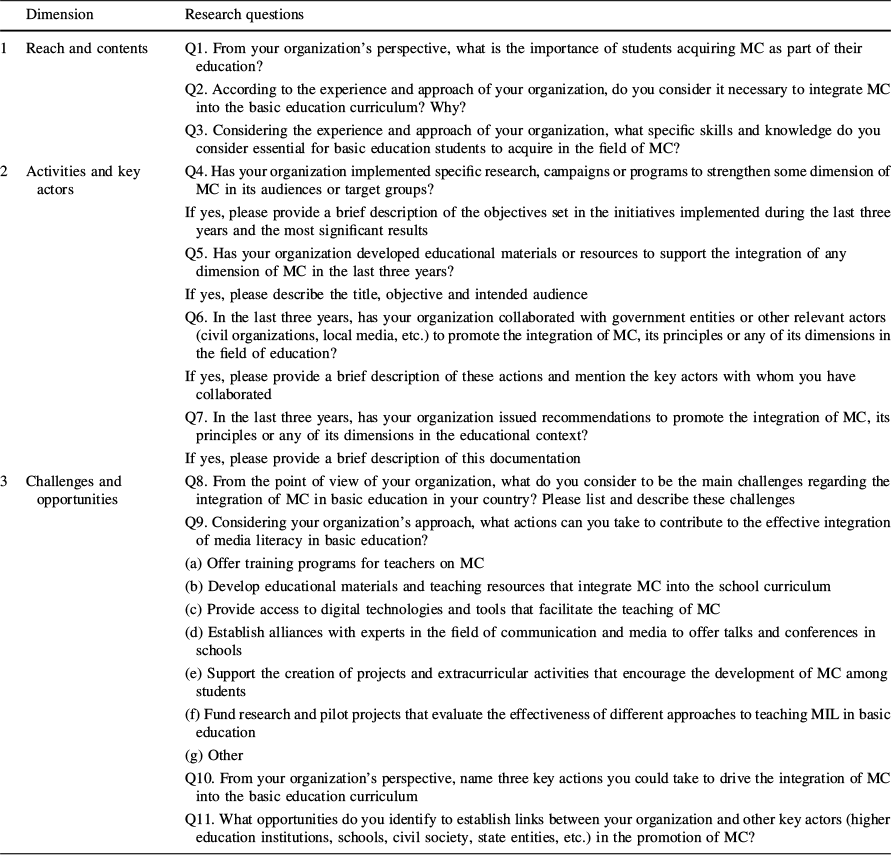

To examine the perception of people working within CSO regarding the integration of MC in basic education, the authors designed a survey composed of eleven questions, categorized into three dimensions (Table 1): a) Reach and contents, focused on determining the opinions of the CSO on teaching these types of competences; b) Activities and key actors, destined to the identification of other essential actors and the activities performed that are related to this topic; and c) Challenges and opportunities. According to Chowdhury et al. (Reference Chowdhury, Oakkas, Ahmmed, Rezaul Islam, Khan and Baikady2022), this data collection method enables systematic and standardized gathering of opinions. It was chosen because it facilitates the distribution of the questionnaire among CSO representatives and provides participants with the flexibility to respond at their convenience.

Table 1 Dimensions and survey questions.

Dimension |

Research questions |

|

|---|---|---|

1 |

Reach and contents |

Q1. From your organization’s perspective, what is the importance of students acquiring MC as part of their education? |

Q2. According to the experience and approach of your organization, do you consider it necessary to integrate MC into the basic education curriculum? Why? |

||

Q3. Considering the experience and approach of your organization, what specific skills and knowledge do you consider essential for basic education students to acquire in the field of MC? |

||

2 |

Activities and key actors |

Q4. Has your organization implemented specific research, campaigns or programs to strengthen some dimension of MC in its audiences or target groups? |

If yes, please provide a brief description of the objectives set in the initiatives implemented during the last three years and the most significant results |

||

Q5. Has your organization developed educational materials or resources to support the integration of any dimension of MC in the last three years? |

||

If yes, please describe the title, objective and intended audience |

||

Q6. In the last three years, has your organization collaborated with government entities or other relevant actors (civil organizations, local media, etc.) to promote the integration of MC, its principles or any of its dimensions in the field of education? |

||

If yes, please provide a brief description of these actions and mention the key actors with whom you have collaborated |

||

Q7. In the last three years, has your organization issued recommendations to promote the integration of MC, its principles or any of its dimensions in the educational context? |

||

If yes, please provide a brief description of this documentation |

||

3 |

Challenges and opportunities |

Q8. From the point of view of your organization, what do you consider to be the main challenges regarding the integration of MC in basic education in your country? Please list and describe these challenges |

Q9. Considering your organization’s approach, what actions can you take to contribute to the effective integration of media literacy in basic education? |

||

(a) Offer training programs for teachers on MC |

||

(b) Develop educational materials and teaching resources that integrate MC into the school curriculum |

||

(c) Provide access to digital technologies and tools that facilitate the teaching of MC |

||

(d) Establish alliances with experts in the field of communication and media to offer talks and conferences in schools |

||

(e) Support the creation of projects and extracurricular activities that encourage the development of MC among students |

||

(f) Fund research and pilot projects that evaluate the effectiveness of different approaches to teaching MIL in basic education |

||

(g) Other |

||

Q10. From your organization’s perspective, name three key actions you could take to drive the integration of MC into the basic education curriculum |

||

Q11. What opportunities do you identify to establish links between your organization and other key actors (higher education institutions, schools, civil society, state entities, etc.) in the promotion of MC? |

This instrument was hosted in an online platform, which also described the aim of the research, together with additional material that provided an explanation on the dimensions of MC and the importance of the participation of CSO representatives in the study. Also, a declaration of privacy was included to guarantee the confidentiality of the data provided by the participants and their consent for being cited in the results. Below, we provide the link to the survey: competenciamediatica.wixsite.com/encuesta

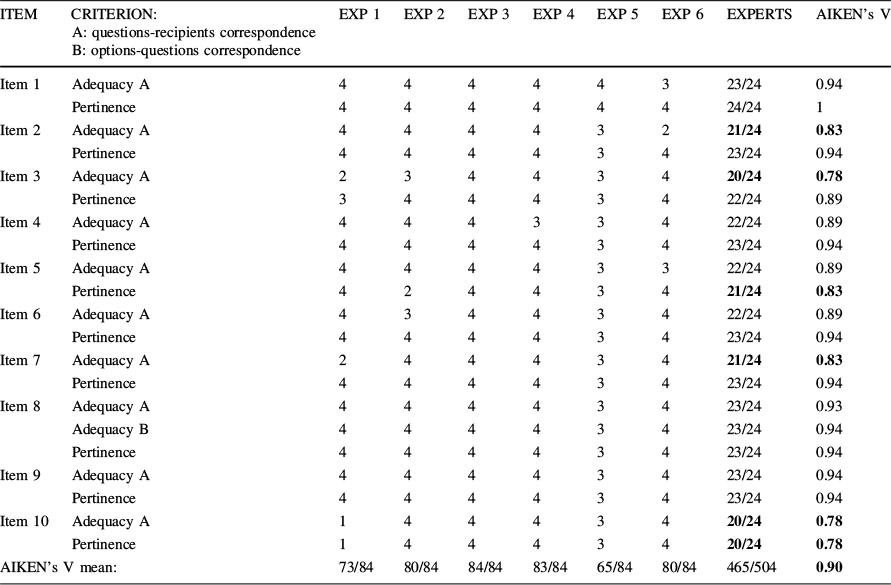

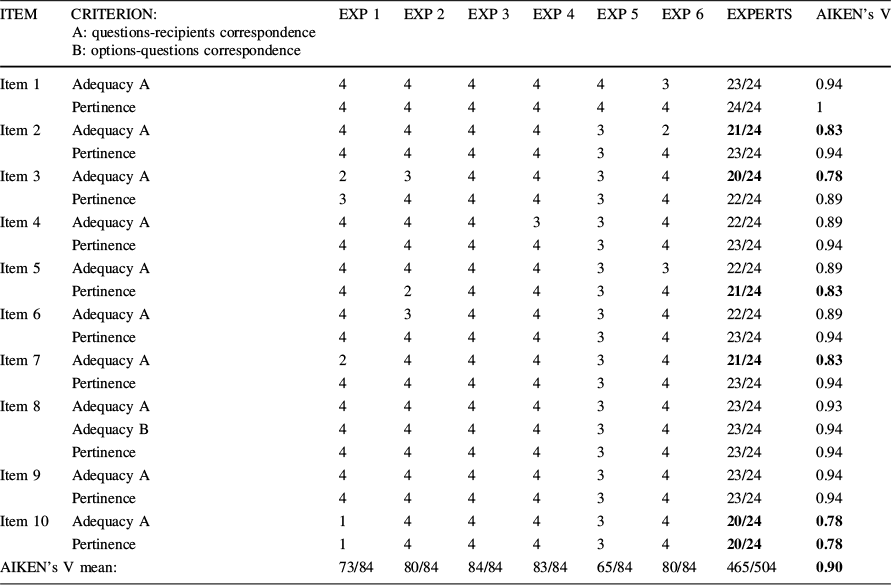

The questionnaire was evaluated by six experts from diverse countries (Spain, Bolivia, Venezuela, Mexico, Ecuador, and Brazil), to verify its suitability and the pertinence of the questions and the designed platform. As Table 2 shows, Aiken’s V was used (Penfield & Giacobbi, Reference Penfield and Giacobbi2004) to analyze the expert’s evaluations, with a coefficient of 0.90 obtained. This result indicated the need to pay attention to specific items, which were modified according to the recommendations by the experts, aside from the inclusion of an additional question in the survey.

Table 2 Aiken’s V validity coefficient.

ITEM |

CRITERION: A: questions-recipients correspondence B: options-questions correspondence |

EXP 1 |

EXP 2 |

EXP 3 |

EXP 4 |

EXP 5 |

EXP 6 |

EXPERTS |

AIKEN’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Item 1 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

24/24 |

1 |

|

Item 2 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

21/24 |

0.83 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 3 |

Adequacy A |

2 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

20/24 |

0.78 |

Pertinence |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

22/24 |

0.89 |

|

Item 4 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

22/24 |

0.89 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 5 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

22/24 |

0.89 |

Pertinence |

4 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

21/24 |

0.83 |

|

Item 6 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

22/24 |

0.89 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 7 |

Adequacy A |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

21/24 |

0.83 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 8 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.93 |

Adequacy B |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 9 |

Adequacy A |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

Pertinence |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

23/24 |

0.94 |

|

Item 10 |

Adequacy A |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

20/24 |

0.78 |

Pertinence |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

20/24 |

0.78 |

|

AIKEN’s V mean: |

73/84 |

80/84 |

84/84 |

83/84 |

65/84 |

80/84 |

465/504 |

0.90 |

|

The sample was selected intentionally, through a process that included a search in Google, using a query composed of three factors and Boolean operators: “civil organization” AND keywords related to the topic (i.e., “communication media,” “technologies,” “digital rights,” “digital citizenship,” “digital context”) AND the name of the Latin American country, according to the list of countries that are members of “The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States” (CELAC), where Spanish or Portuguese is spoken. Also, searches were performed in government directories, such as the federal registry of CSO in Mexico (Gobierno de México, 2021), to identify entities according to the following inclusion criteria: a) civil associations or active foundations, focused on education, social development, human rights, and/or culture/art; b) whose objectives or projects are related with the use of ICT as educational tools, the defense and promotion of the liberty of expression, the promotion of digital empowerment, the protection of digital rights, and/or the promotion of digital citizenship; c) with headquarters in any of the countries included in the study.

Afterward, a database was created of the 209 CSO that were contacted via email and social networks, to invite them to participate in the survey during the period from February 21 to April 21, 2024. During this period, 63 CSO representatives from fourteen different countries completed the survey, representing a response rate of 30.14%. This net response rate falls within the ranges observed in studies on CSO identified in the book by Johansson and Meeuwisse (Reference Johansson and Meeuwise2024). These were distributed in the following manner: Argentina (8), Bolivia (2), Brazil (4), Chile (9), Colombia (7), Costa Rica (1), Ecuador (7), El Salvador (1), Guatemala (1), Mexico (12), Nicaragua (1), Panama (3), Peru (3), and Venezuela (1), and three organizations that considered their reach to be Latin American, although they did not specify any country as their headquarters.

According to the information provided on their official websites, 51 of these organizations are identified as statutory non-profit entities, created by groups of citizens and funded by international organizations, public funds, or donations. The remaining organizations, while also non-commercial, adopt diverse structures, including 5 foundations (3 corporate and 2 civic) with governing boards, 4 independent collectives bringing together professionals and/or community members who are volunteers, 1 personal project (a platform led by a citizen), 1 community forum operating as a collective event, and 1 media observatory described as an agency affiliated with the government. Also, it is important to highlight that 57.1% of those surveyed were part of the CSO management team (CEO, director/general manager, etc.), while the remaining 42.9% were part of middle management (department heads, team leaders, etc.).

Results

Perspectives of CSO Representatives About the Understanding of the MC Concept and its Reach

According to the answers provided by the participants, three reasons stood out that underlined the importance of students developing MC during their period of education. In first place, in a global context characterized by a growing interconnection and the omnipresence of screens, these competences become indispensable for individuals to be able to effectively navigate and participate in a digital environment. In second place, their acquisition allows students to guarantee their online well-being. In third place, their fundamental role in guaranteeing equal access to the opportunities offered by the digital sphere for all students, independently of their origin was recognized. Although to a lesser degree, an emphasis was made of the importance of this knowledge for the full exercise of their rights to information and the liberty of expression, especially in contexts where censorship and violence against journalists are ever-present worries. In addition, an organization in Colombia highlighted the importance of teaching students about the “creation of informational or recreational content under quality and responsible standards.” Thus, the dual role of citizens as consumers and producers of information is recognized.

Likewise, they justify the curricular integration of MC in order to teach children and youth analysis strategies that allow them to discern between trustworthy sources and fake news. They also argued for the need for students to acquire knowledge about their rights in the digital space and to learn effective ways to protect their privacy. Other participants, from organizations focused on fighting against digital violence against women, considered that MC can be used to teach concepts related with this type of violence, the keys and mechanisms that protect victims, and the ways to prevent it: “In Mexico, children should grow up with an understanding of the legal reforms that penalize the unauthorized sharing of intimate content in digital spaces.”

On the other hand, the participants consider it essential for students, aside from developing the ability to analyze information critically, to acquire the following competences: a) to behave with integrity and in a respectful manner in digital spaces, particularly in social networks; and b) to efficiently utilize devices and technologies. Additionally, to a lesser degree, an emphasis was made on the importance of becoming aware of the underlying interests of the media, and to understand the emotional connection established with them. In particular, for the representative of “Fundación Más por TIC” (Colombia), it is crucial for the youth to recognize how communication media can become powerful tools for promoting social change and to promote fundamental values in the community. On the other hand, for the representative of “A mí no me la hacen” (Perú), it is considered imperative to disseminate the idea that the integration of MC in basic education must not only address technical skills, but also must also promote a more informed and critical digital citizenry.

The member of Internet Society Panamá” (ISOC Panama), in particular, states that this integration must start at early ages to maximize its effectiveness and relevance in the development of citizens. The representative of “Ratona de TV” (Mexico) agrees, pointing out that “even before becoming students, children become media audiences.” However, a participant from Ecuador believes that addressing these topics in early education could be premature due to the characteristics of the cognitive and emotional development of children at that age. Thus, he suggests that primary education would be the most adequate stage for introducing these concepts.

A striking aspect is that eight representatives indicated not knowing about the reach of MC or that it encompassed diverse dimensions. Three mentioned not being aware that their actions were aligned to the principles related to the topic, but they instead identified them with “digital competence” or “digital education”: Also, two of them indicated that they did not know the term: “This is the first time I have heard the concept of MIL. In our context, we have primarily focused on digital education, as it has been the predominant topic in discussion forums and legislative documents in our country.” According to Neag et al. (Reference Neag, Bozdağ and Leurs2022), the popularization of the term MIL and its competences implies a continuous effort of public awareness and education about their importance and benefits, for both educators and society in general, a task that in many cases is not considered a priority by the political sphere or the organizations in charge of guaranteeing access to quality education. Thus, it would be advantageous for CSO to become familiar with the opportunities that MIL can provide for their strategic plans, activities, and target audiences.

Activities and Key Actors Identified by the CSO Representatives Within the Framework of Integration of MIL

Programs and Projects

Of the 63 organizations examined, only 33 (52.38%) have developed activities that are specifically directed to schools, teachers, or school groups. These programs and projects have been mainly organized into three categories:

(a) Organizations with programs or projects of technological training and robotics In this area initiatives such as the project SPORTIC stand out, sponsored by the “Fundacion SES” (Argentina), which seeks to decrease gender inequalities and improve access to technologies as well as sports. Also, organizations such as “Fundación más Tecnología” in Chile, together with the “Fundación para la Reducción de la Brecha Digital” (Ecuador), offer advice and workshops to promote the learning of robotics at schools. Likewise, projects such as those by the “Fundación Más por TIC” (Colombia), which provide camps about innovation and technology for the youth in rural areas, are framed within this category.

(b) Organizations with programs or projects destined to address disinformation and digital safety. In this classification, initiatives such as the curriculum “Digimente” stand out, promoted by “Movilizatorio,” which is designed to train teachers in Latin America on how to address disinformation. At the same time, organizations such as “Chicos.net” (Argentina), or “TICMAS” (Ecuador), offer projects related with digital citizenship, cyberbullying, and grooming. “Casa Hacker” and “Fundacion Datos Protegidos” in Chile provide training on digital security for educators, promoting a healthy relationship with technology.

(c) Organizations with programs that explicitly address MIL. In this classification, we detected three programs that offer courses for teachers in this area: AMI para tod@as”, from “Rueditas Digitales” (Mexico), specifically designed for upper secondary education teachers; the program “Alfabetizad@s,” a collaboration between “Wikimedia” and “Faro Digital” (Argentina), which offers a training plan directed to teachers at all levels of education who are interested in strengthening their MIL competences; and “AMI Academy” by “A mi no me la hacen” (Peru). Also, we find “ABPEducom” in Brazil, which includes special projects such as meetings with researchers who work on educommunication topics and the organization of events such as “MIL Week” in the country, an initiative promoted by the UNESCO that is celebrated annually.

Different groups of organizations were identified, which, although they have other target audiences, they have programs and projects related with the development of MIL, which have been classified into the following groups:

(a) Organizations dedicated to the education, protection, and involvement of women in technology, which include, for example, “Mujeres TICs” in Guatemala, “Women of Security” in Panama, and “Mentoralia” in Mexico, with its project “Technovation Girls.”

(b) Organizations focused on fighting against gender violence in digital platforms or promoting more diverse representations in the media, for example, “Comunicar Igualdad” in Argentina and “Chicas Poderosas” in Mexico.

(c) Organizations dedicated to the defense of human rights in digital settings and data safety, which include, for example, “Youth IGF Ecuador,” “Datalat” in Ecuador and “Hiperderecho” in Peru. These organizations develop projects to promote transparency in public information and electoral processes. Additionally, “Social TIC” (México) organizes workshops to train info-activists, underlining the importance of strengthening these key actors in defense of digital rights and the promotion of informed citizens.

(d) Organizations dedicated to the creation of audiovisual material or contents to promote the democratization of communication and the culture of peace, for example, the “Grupo Comunicarte,” backed by Signis, which uses methodologies such as participative videos, and “La Otra Juventud,” which also operates in Colombia.

To optimize the viewing of the CSO classified according to projects and programs, an interactive map has been developed to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of their distribution. This resource is available in the following link: bit.ly/4c6MTWd

Campaigns, Research, and Recommendations

Many organizations implement initiatives through media and social networks, especially focusing on digital risks, such as the impact on health and the proliferation of fake news. For example, the aim of the Campaign “Internet segura para Jóvenes” from “ISOC Panama”, is to raise awareness and train youth about the danger of the Internet, promoting responsible and beneficial digital practices. Similarly, the Campaign “Vera,” promoted by the “Asociación Nacional de Medios de Comunicación” in Colombia, focuses on identifying and countering fake news. Other initiatives, such as “#ElpornoNoeduca” from the Faro Digital in Argentina, and “copiar-pegar: el pasaje hacia la ciudadanía digital,” invite encourage reflection on device use and promote critical awareness. Nevertheless, the Campaign “Educación Digital Crítica para Todos,” promoted by “JAAKLAC” stands out, as it seeks to raise awareness and promote conversations with respect to the rights to quality education in the digital era. Also, this initiative explicitly mentions media education, and is focused on learning not only “with” technologies, but also “about” them. It also maintains a close relationship with Latin American activists and youth.

The participation of the organizations in MIL principles-centered research. However, for eleven of them, this area of action is considered as one of the main ones, or is found among their priority activities. The role played by “A mí no me la hacen” (Perú) stands out, as it has acted as a consultant for the “International Programme for the Development of Communication” (IPDC) of the UNESCO, contributing to the development of research in this area. Also, “Faro Digital” (Argentina) conducted an exploratory study with the Secretaría Nacional de Infancia, Adolescencia y Familias (SENAF), as part of the program “Clic derechos,” focused on the knowledge and perceptions of adolescents about grooming. Organizations like “Fundación País Digital” (Chile), which conducted the study “Futuro de la Educación en Chile: Innovación, tecnología y habilidades del siglo XXI”, supported by the UNESCO. “REImagina” (Chile), establishes alliances with specialized centers to conducted research and share findings, informing local and global debates.

On the other hand, 93% of the participants affirm that their organizations have not provided recommendations for promoting the integration of MC, its principles, or any of its dimensions in the area of education. However, many of these organizations highlight the importance of this measure, arguing that it is fundamental for involving the political sphere, the communication media, and companies, in the adoption of specific measures in this regard, as well as to bring to light certain phenomena. For example, the member of “Fundación Datos Protegidos” de Chile underlined that in 2021, more than 60 organizations signed an open letter directed to Facebook and Google, which urged these platforms to assume responsibility as two of the most influential actors in online political campaigns, to promote a greater transparency in electoral propaganda, in order to empower users and voters (Privacy International, 2021).

Education Resources and Key Actors

In total, 63.4% of the participants mentioned that in the last three years, their organizations performed or promoted MIL-related resources MIL for teachers. Among the most important resources provided by the CSO, we find:

(a) Teaching guides, manuals, and curricula: “Civix Colombia” has developed the curriculum “Doble Click” with the financial support of the European Union, a training proposal directed to both students and teachers that is composed of 23 lessons distributed in seven modules, complemented with an internet platform that offers resources, podcasts, and gamification tools (Doble Click, 2024). Similarly, “Faro Digital” (Argentina) has developed a guide about media education, entitled Crítica (2020) which includes activities designed for addressing disinformation and other related topics, specifically directed to secondary education professors.

a. On the other hand, “ISOC Panama” has created the guide “¡Ciberseguridad: tu reto diario!” (Cybersecurity: your daily challenge!), which addresses essential topics of cybersecurity, and is designed for students and teachers in basic and secondary education. In the Chilean context, “Ideodigital” provides training proposals for teaching programing, from 7th grade to 12th grade (4to medio in Chile), in line with the curriculum in the area of technology. Likewise, the initiative “Digimente” offers educators support to be able to adapt their training programs on disinformation and media education, facilitating the effective implementation of these contents in the education setting.

(b) Educational content: “ISOC Panamá” has produced diverse infographs directed to students in different stages of education, such as the Infografía código de convivencia digital para escolares” and the “Buenos hábitos de convivencia digital para jóvenes”, which offer guidance on the responsible use of internet outside a school setting. Likewise, “Ideodigital” (Chile) has created two comic books starring Aida, a purple octopus, who seek to educate and raise awareness about the importance of maintaining a healthy balance in their interaction with technology.

(c) Videogames: As for interactive resources, the creation of the videogame “INFODEMIC”, created by “A mi no me la hacen” (Peru) stands out. It allows participants to assume the role of journalists, who must make decisions on how to address diverse events in the community, in order to generate debate about MIL in classrooms. On its part, “INOMA” (Mexico) has developed a series of videogames designed to promote creative skills through art and creative writing, which are accompanied by pedagogic guides that help teachers to integrate these resources in the education process, and has also created “Tak-USB,” a USB pen drive that contains the videogames developed, ensuring access to them without the need of an Internet connection.

(d) Blogs and articles: Twelve organizations have pointed out to the presence of blogs where they share relevant content on topics related with MIL or the writing of contents in platforms such as LinkedIn. Among the articles highlighted, we find “Sephora Kids: ¿menores de 15 usando cremas antiedad?” (Sephora Kids: children under 15 using anti-aging creams?), published by “Rueditas Digitales” (2024), which critically examines the impact of media on their perception of self and the self-esteem of those younger than 15, also exploring their influence in social and cultural aspects.

(e) Platforms with resources: The platform “Chicos.net” has teaching cards destined to teachers on many topics such as digital citizenship, artificial intelligence, and digital well-being. “REImagina” (Chile) highlights the platform “Aprendo en Casa”, which has more than 700 resources on digital education. On its part, the “Centro de Inovação para a Educação Brasileira” (Innovation Center for Brazilian Education) makes available the platform “EduTec,” which has a broad range of digital education solutions, organized with filters to ease their access to education managers.

(f) Videos and Podcasts: Also, CSO have ventured into the production of podcasts and magazines, which are available for perusal by teachers. For example, “Wikimedia Argentina” has launched a cycle of interviews centering on human rights on the Internet. Also, the creation of material for dissemination in social networks stands out, which include both images and videos.

In total, 96.8% of the respondents reported having collaborations with other key actors. These collaborations have materialized as projects with other local and international CSO, and in some cases, have expanded to alliances with other chapters of the same organization in different countries. In second place, the collaboration with local governmental entities is underlined, as they contribute to the creation of education materials, facilitating the teaching of courses related with the topic. For example, the organization “Robotix Fundación” (Mexico) mentions that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the state bodies asked for their support in making a broadcasted program in “Aprende en Casa” at the national level, in collaboration with the “Fundación LEGO” and the “Fundación Politécnico”. Likewise, they have associated with national university academics for the development and counseling on the creation of materials, and it is also mentioned that representatives of the CSO have been invited to give conferences in academic forums or spaces at universities. Seven of them indicate having collaborated with organizations associated with the media industry, such as the “Fundación Telefónica” or the “DW Akademie”.

Opportunities and Challenges Recognized by CSO Representatives for Integrating MC in the Educational Setting

For the participants, the main challenges related with the integration of MC in the education system of their respective countries are:

(a) The need to popularize the concept of MIL, in order to raise awareness in diverse actors about its importance and reach.

(b) The establishment of solid institutional alliances that support long-term campaigns in the area of media education, thus facilitating a greater coordination and efficacy in the actions taken.

(c) The urgency in achieving that all the interested parties, especially the political sphere, understand and prioritize the importance of including the teaching of these competences in the education curriculum, recognizing their relevance in the current context.

(d) The insufficient provision of tools and resources for teachers.

(e) The digital divide, which is manifested in the unequal access to technology and the low internet connectivity at schools.

(f) The lack of updated curricula, which impedes the adequate incorporation of contents and approaches related with MC in the existing study plans, which makes its effective integration in the education system difficult.

To a lesser degree, they mentioned the working conditions of teachers, such as low salaries, the saturation of the curriculum, and the scarce participation of the parents or caregivers in the education process. Also, two respondents highlight the importance of recognizing that the development of MC is important not only in the formal education setting, but the informal one as well. From the perspective of one of them, this understanding “will facilitate its adaptation to other contexts, as children are not only students, but sons and daughters as well.”

With respect to the question about the actions that could facilitate the effective integration of MC in basic education, as shown in Fig. 1, two measures stand out among the participants. In first place (96.8%), the importance of establishing strategic alliances with experts in the media education field is underlined, with the purpose of offering talks and activities at schools. In second place (95.2%), an emphasis is found in the need to implement training programs for teachers, to train them on the design and implementation of pedagogic strategies that effectively integrate MC. In addition, a suggestion is made for the development of education materials and resources that are specifically designed to address aspects related with MC (76.2%), as well as the technological provision of schools to facilitate access to digital tools (74.6%).

Fig. 1 Actions for contributing toward the curricular integration of MC.

Likewise, the creation of extracurricular projects is important, as they can foment the development of media skills among students outside of the classroom (71.4%). Lastly, some respondents raise the need to fund research and pilot projects that allow for the assessment of the effectiveness of the strategies implemented in the area of MC (20.6%). However, it is recognized that this option can be limited due to the search for funding by the organizations, which are on many occasions dependent on resources provided by international and governmental entities. Also, the representative of “A mí no me la hacen” (Peru) suggests starting awareness campaigns to promote the integration of MC in the education context.

With respect to three key actions to drive the integration of MC in the curriculum of basic education, the following priority options stand out: a) Establish international and inter-institutional alliances to support its insertion; b) Implement training programs for teachers, centered on the development of MC; c) Contribute toward the advancement of research to guide the formulation of a curriculum in this area. Additionally, the participants identify opportunities to establish links with key actors in the promotion of MC: a) collaborate with school, especially for piloting materials created; b) work together with state entities to have an influence on the development of public policies on media education and cybersecurity; c) partnering with media to promote an ethical and responsible coverage of MC issues; and e) involve companies in the promotion of MC through initiatives of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and educational sponsorship. Also, the importance of taking advantage of key international events stands out, such as the “MIL Week” of the UNESCO and the “Press and Media Week in Schools” of the French Ministry of Education.

Conclusions

The aim of the present article was to offer a comprehensive approach to the perception of people working within CSO on the integration of MC in the curriculum of basic education in Latin American countries. Next, a discussion is presented about the three dimensions analyzed:

Reach and contents The participants recognize that the teaching of MIL implies more than simple technical instructions; they also emphasize the development of competences for critically analyzing information, and safely and responsibly navigate in digital environments. They argue that this integration is essential for shaping digital citizens who are informed, reflective, and ethical. However, some aspects, such as the empowerment of students in areas such as social mobilization, civil participation, and intercultural dialog, received less attention. Also, most of the competences pointed out by the respondents define students mainly as “consumers” of information and content, without fully considering their potential as content creators able to counteract and fragment the dominant narratives.

It is important to point out that some CSO representatives who participated in the survey indicated not being fully aware that they were contributing toward the development of MC, nor having explored the meaning and the implications of MC in depth. To address these limitations, it is fundamental for CSO to receive training in this area, as well as the design and implementation of related projects. Providing this type of training will allow CSO members to play a more effective role in the promotion of MIL, facilitating the training of not only students and teachers, but also the population in general, given the reach of these organizations, which includes disadvantaged groups. Also, it will allow for the creation of initiatives for integrating MIL or its principles in the education system, particularly with respect to its inclusion in the curriculum. In this context, the absence of a curriculum or specific guide for this key group in the region is notable.

Activities and key actors The findings reveal the substantial commitment of CSO in the promotion of MIL or some of its principles. This effort is observed in the area of education through a broad range of educational materials, such as teaching guides and manuals, which not only support formal teaching, but also seek to raise awareness in students and teachers on the importance of cybersecurity, digital well-being, and the reflective analysis of the messages they consume. The diversity and specificity of the resources create also mirror a deep understanding of the contemporary education needs and the willingness to adapt to diverse contexts and audiences, including parents.

Likewise, it is important to highlight that CSO have forged strategic collaborations with diverse key actors, which include both local and international organizations, as well as governmental entities, academic institutions, and organizations related with the media industry. These alliances have played a fundamental role in various crucial aspects. On the one hand, they have facilitated the creation of educational resources, the organization of training courses, and the dissemination of specialized knowledge. On the other hand, these associations have made significant contributions toward the widening of this dissemination and the impact of the MIL-related initiatives, as well as to ensure the necessary financing to perform these activities.

Nevertheless, one of the least opportunities mentioned was the collaboration with technology companies to develop innovative, accessible resources, and large-scale projects. Examples such as the “New School Model” in Georgia, which integrated MIL into the curriculum, and provided electronic resources and internet to schools with the help of Microsoft, showcasing the benefits of strategic synergies (Levitskaya & Seliverstova, Reference Levitskaya and Seliverstova2020). Collaborations like these allow for stronger funding strategies, sustainable partnership models, and program continuity, even amid political and economic shifts that often threaten such initiatives.

Opportunities and challenges From the need to popularize the concept, to the lack of curricular updates, the digital divide, and the lack of political will, these entities have identified diverse obstacles that require strategic and collaborative approaches in order to overcome them, coinciding with those determined by other groups, such as teachers, with respect to the process of integration of MC in the education system (Mateus et al., Reference Mateus, Andrada, González-Cabrera, Ugalde and Novomisky2022). In this sense, their ability to mobilize resources, raise public awareness, and advocate for inclusive and equitable policies, is fundamental for addressing emergent challenges with respect to MIL. In addition, their approach, which is centered on the community, allows them to identify and effectively respond to the specific needs of diverse population groups, including those who could be marginalized or excluded from the debates and the decision-making processes.

Although the interests of CSO could be in conflict with other key actors, and may not be recognized as legitimate actors in the process of policy formulation or in the implementation of education programs, or given that they may face limitations related with financial, human, and technical resources, their experiences, knowledge, and visions make them fundamental entities for empowering individuals and communities in a digital world in constant change. Thus, it is essential for those responsible for formulating policies, educational institutions, and other relevant actors, to recognize the transforming potential of CSO, to provide them with the necessary support so that they can perform their projects and campaigns effectively, while leading advocacy processes that advocate for an education curriculum that includes these essential competences.

As for the limitations of the study, the number of CSO members who answered the survey must be highlighted, as it has an effect on the representativeness of the results. In this regard, it should be noted that the sample selection process did not involve consultation with experts. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to perform a systematic analysis of the objectives, initiatives, and impact of each of the CSO. This approach would allow for a deeper and more detailed understanding of the strategies and achievements of these organizations, facilitating the identification of good practices and areas of improvement.

Author Contributions

Elizabeth-Guadalupe Rojas-Estrada: Conceptualization; Literature search and Data analysis; Writing-original draft; Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Rosa García-Ruiz: Literature search and Data analysis; Writing-Reviewing and Editing; Supervision. Ignacio Aguaded: Supervision, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. All the authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Huelva/CBUA. Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Huelva/CBUA. This work is conducted within the support of the R + D Project “Alfabetización mediática y digital en jóvenes y adolescentes: Diagnóstico y estrategias de innovación educativa para prevenir riesgos y fomentar buenas prácticas en la Red,” financed by the Consejería de Universidades, Igualdad, Cultura y Deporte of Gobierno de Cantabria, the R&D Project “Research, design and implementation of a curricular proposal for teacher training in media literacy in the Euro-American context” of the Call for Knowledge Generation Projects 2023 (code PID2023-146288NB-I00) of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain, and the Project ‘The Alfamed Curriculum: Research and implementation of a proposal for teacher training in media education in Ibero-America’ in the Research and Transfer Policy Strategy of the University of Huelva’ (Spain) (EPIT 2023) (code EPIT16132023). E. G. Rojas-Estrada [CVU 1229049] is thankful to Conahcyt (Mexico) for the scholarship granted under the “Doctorados en Ciencias y Humanidades en el Extranjero 2022” call.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.