Introduction

α-Tocopherol, the most biologically active form of vitamin E, is a vital micronutrient for companion and farm animals, playing a key role in maintaining physiological balance, safeguarding cellular membranes, and supporting health and productivity. As a lipid-soluble antioxidant, α-tocopherol neutralizes free radicals and prevents oxidative damage to biological structures (Traber and Atkinson Reference Traber and Atkinson2007). Its importance in livestock nutrition is highlighted by its influence on immune function, reproduction, muscle growth, and meat quality (Idamokoro et al. Reference Idamokoro, Falowo and Oyeagu2020; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Meydani and Wu2019; Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024a). With growing emphasis on sustainable and efficient animal production, understanding the bioavailability and biopotency of α-tocopherol is crucial for optimizing dietary strategies.

Vitamin E comprises a family of compounds (vitamers) – tocopherols and tocotrienols – each with four isoforms (α, β, γ, and δ) differing in methyl group arrangement on the chromanol ring. Among these, α-tocopherol is distinguished by its superior biopotency, attributed to its preferential binding to hepatic α-tocopherol transfer protein (α-TTP) (Traber Reference Traber2007). This protein ensures selective incorporation of α-tocopherol into circulating lipoproteins, making it the predominant isoform in plasma and tissues of animals and humans (Arai and Kono Reference Arai and Kono2021; Traber Reference Traber2013). Despite its prominence, several factors – including chemical form, dietary composition, gastrointestinal physiology, and digestive efficiency – affect the absorption, distribution, and utilization of α-tocopherol, resulting in considerable variation in its bioavailability and biopotency across species and production systems (Dersjant-Li and Peisker Reference Dersjant-Li and Peisker2010; Lashkari et al. Reference Lashkari, Clausen and Foldager2021; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). This variability has significant implications for effective dietary supplementation.

Synthetic DL (all-rac)-α-tocopherol, produced chemically, consists of eight stereoisomers in equal proportions, while natural α-tocopherol from plants exists as a single stereoisomer, RRR-α-tocopherol (Kuchan et al. Reference Kuchan, Moulton and Dyer2018). The bioavailability of α-tocopherol refers to the extent and rate at which it is absorbed and becomes available in the bloodstream or at the site of action. Factors affecting bioavailability include the chemical form (free vs. acetate), dietary composition, gastrointestinal physiology, and the selective retention of RRR-α-tocopherol and 2R-stereoisomers by hepatic α-TTP, which eliminates other stereoisomers (Desmarchelier and Borel Reference Desmarchelier and Borel2017; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a; Traber Reference Traber2007).

Biopotency refers to the biological activity of α-tocopherol in exerting physiological effects, influenced by isomeric configuration, tissue-specific distribution, and metabolic demands (Hoppe and Krennrich Reference Hoppe and Krennrich2000). The relative potency of different isomers is of significant interest, as synthetic forms contain a racemic mixture with varying activity, prompting efforts to quantify equivalence between natural and synthetic forms in promoting health and production outcomes.

Recent advances in analytical techniques have improved the assessment of α-tocopherol and other fat-soluble vitamins in animals, enabling detailed investigation of their absorption, distribution, and metabolism (Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Pelletier and Kuntz2024). These advances have also facilitated the development of novel delivery systems to enhance α-tocopherol stability and bioavailability in feeds (Mujica-Álvarez et al. Reference Mujica-Álvarez, Gil-Castell and Barra2020; Saberi et al. Reference Saberi, Fang and McClements2013; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Li and Guo2024), addressing limitations of conventional supplementation.

Throughout this review, the primary focus is on α-tocopherol, the principal and most biologically active form of vitamin E in animal nutrition. The term “vitamin E” is used when referring to general properties or processes common to all, or at least several, vitamers – always including α-tocopherol. In contrast, specific discussions and mechanistic details focus on α-tocopherol unless otherwise stated. This approach is intended to provide conceptual clarity and narrative consistency, ensuring that the relationship between α-tocopherol and the broader vitamin E family is clearly defined and maintained across all sections of the manuscript.

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of α-tocopherol’s bioavailability and biopotency in animal nutrition, focusing on factors influencing its effectiveness and strategies to optimize its use. We review vitamin E absorption, transport, and retention, explore the molecular basis of α-tocopherol’s antioxidant function, and examine internal and external factors affecting its bioavailability and biopotency. The review evaluates current supplementation practices, highlights knowledge gaps, and emphasizes species-specific requirements, aiming to support evidence-based, species-specific supplementation strategies for improved animal performance, product quality, and sustainability.

Overview of absorption and metabolic fate

Vitamin E plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular integrity and function. The bioavailability and biopotency of vitamin E and its vitamers are intrinsically linked to its absorption, metabolism, and excretion processes. A clear understanding of these pharmacokinetic pathways is essential for optimizing their efficacy in animal nutrition and for developing evidence-based supplementation strategies.

Absorption

The absorption of vitamin E occurs primarily in the small intestine and is closely associated with dietary fat intake (Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a; Szewczyk et al. Reference Szewczyk, Bryś and Brzezińska2025). Being lipophilic, vitamin E requires the formation of micelles facilitated by bile salts and pancreatic enzymes for efficient absorption into enterocytes (Iqbal and Hussain Reference Iqbal and Hussain2009; Torres et al. Reference Torres, de Oliveira Sartori and de Souza Silva2022). The primary supplementation form for companion and farm animals is DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, which is hydrolyzed in the intestinal lumen by pancreatic carboxyl ester hydrolase to release free α-tocopherol for absorption (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Engberg and Hedermann1999). In contrast, natural D-α-tocopherol and other vitamin E vitamers present in feed ingredients are absorbed directly in their nonesterified forms. Included in micelles, the vitamin enters intestinal absorptive cells through passive diffusion (endocytosis), influenced by the concentration gradient between the intestinal lumen and the enterocyte cytoplasm (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP) 2010). Recent studies suggest that transport proteins, such as scavenger receptor class B type I and Niemann–Pick C1-like 1, may play an additional role in vitamin E uptake (Reboul Reference Reboul2019). Once inside the enterocytes, vitamin E is released from the micelles and incorporated into chylomicrons (portomicrons in poultry), which are released into the lymphatic system (directly into the portal circulation in poultry) and subsequently the bloodstream (Gagné et al. Reference Gagné, Wei and Fraser2009). This process is nonspecific, allowing for the absorption of all vitamin E vitamers, including α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherols and tocotrienols (Jiang Reference Jiang2022). However, the efficiency of absorption is influenced by various factors such as dietary composition, the presence of dietary fats, species-specific metabolism, digestive efficiency, as well as the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract, and health status (Hidiroglou et al. Reference Hidiroglou, Cave and Atwal1992; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a; Vagni et al. Reference Vagni, Saccone and Pinotti2011; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Chin and Suhaimi2017).

Metabolism and excretion

After absorption, chylomicron remnants deliver vitamin E to the liver, where a selective process determines its fate (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao and Wang2020). The liver preferentially incorporates α-tocopherol, particularly RRR-α-tocopherol, into very-low-density lipoproteins for distribution to peripheral tissues, a process mediated by the α-TTP protein (Bromley et al. Reference Bromley, Anderson and Daggett2013; Manor and Morley Reference Manor and Morley2007). Other vitamers and stereoisomers of vitamin E are more readily metabolized in the liver (Schmölz et al. Reference Schmölz, Birringer and Lorkowski2016). Metabolism begins with ω-hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes, primarily CYP4F2, followed by successive rounds of β-oxidation that shorten the phytyl tail, ultimately producing water-soluble metabolites such as carboxyethyl-hydroxychromans (CEHCs) (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Pal and Zhang2021; Mustacich et al. Reference Mustacich, Leonard and Patel2010; Traber et al. Reference Traber, Leonard and Ebenuwa2021). This ω-hydroxylation step is considered rate-limiting, and CYP4F2 shows strong substrate specificity for tocopherols and tocotrienols (Jiang Reference Jiang2022; Youness et al. Reference Youness, Dawoud and ElTahtawy2022). After β-oxidation, CEHCs undergo conjugation with glucuronic acid or sulfate to enhance solubility and facilitate urinary excretion (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ge and Singh2017). These metabolites are essential for maintaining vitamin E homeostasis and may exert biological effects, including modulation of inflammation and natriuresis.

Recent studies have revealed that intermediate metabolites, such as 13′-carboxychromanols (13′-COOH), formed prior to CEHCs, are not merely degradation products but bioactive compounds with significant physiological roles (Ciarcià et al. Reference Ciarcià, Bianchi and Tomasello2022). These metabolites inhibit cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways, modulate lipid metabolism, and activate nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and pregnane X receptor, contributing to anti-inflammatory effects (Jiang Reference Jiang2022; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Sun and Yang2025). Evidence also suggests that tocotrienol-derived metabolites may influence gut microbiota and neuroprotection, including prevention of β-amyloid formation in animal models, highlighting their potential in chronic disease prevention (Kumareswaran et al. Reference Kumareswaran, Ekeuku and Mohamed2023; Yunita et al. Reference Yunita, Nasaruddin and Ramli2025).

Furthermore, tocotrienols and non-α-tocopherol forms are metabolized and cleared more rapidly than α-tocopherol, explaining their lower plasma concentrations despite potent antioxidant properties (Szewczyk et al. Reference Szewczyk, Chojnacka and Górnicka2021). Genetic polymorphisms in CYP4F2 pharmacogene and α-TTP, as well as dietary factors and disease states, can significantly alter these metabolic pathways and vitamin E status (Athinarayanan et al. Reference Athinarayanan, Wei and Zhang2014; He et al. Reference He, Liu and Zhang2017).

Excretion of vitamin E and its metabolites occurs via both biliary and urinary routes (Brigelius-Flohe et al. Reference Brigelius-Flohe, Kelly and Salonen2002; Schubert et al. Reference Schubert, Kluge and Schmölz2018; Traber Reference Traber2013). Most unretained vitamin E is eliminated in feces through bile, while water-soluble metabolites, primarily CEHCs and sulfated derivatives, are excreted in urine (Baltusnikiene et al. Reference Baltusnikiene, Staneviciene and Jansen2023; Schmölz et al. Reference Schmölz, Birringer and Lorkowski2016). The balance between these pathways ensures vitamin E homeostasis and prevents toxicity, although excretion rates vary with vitamin E form, age, health status, and metabolic capacity (Jiang Reference Jiang2022; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). The liver’s selective retention of RRR-α-tocopherol remains a critical determinant of its superior biopotency and tissue distribution compared to other stereoisomers and vitamers, underscoring the importance of stereochemistry and metabolic clearance in supplementation strategies for both human and animal nutrition.

Species differences

While the fundamental processes of vitamin E absorption, metabolism, and excretion are conserved across species, there are notable differences. For example, ruminants have a complex stomach with multiple compartments that can alter the bioavailability of vitamin E, potentially requiring higher dietary intake to achieve optimal plasma levels (Alderson et al. Reference Alderson, Mitchell and Little1971; Schelling et al. Reference Schelling, Roeder and Garber1995; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak, Pelletier and Jenkins2023a; Song et al. Reference Song, Wang and Sun2023). In contrast, monogastric animals like pigs, poultry, and companion animals have simpler digestive systems, allowing for more efficient absorption. Additionally, the expression and activity of α-TTP can vary among species, affecting the distribution and retention of α-tocopherol (Aeschimann et al. Reference Aeschimann, Staats and Kammer2017; Rengaraj et al. Reference Rengaraj, Truong and Hong2019; Ulatowski et al. Reference Ulatowski, Dreussi and Noy2012). Moreover, there may be other differences in the mechanisms of absorption and metabolism that still require clarification. These differences could be due to variations in intestinal transport proteins, enzymatic activity, or genetic factors that affect vitamin E utilization. Understanding these interspecies variations is vital for formulating appropriate dietary recommendations and therapeutic interventions. Tailoring vitamin E supplementation to the specific needs of different species can enhance health outcomes and ensure optimal nutrient utilization.

Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying these species differences, particularly regarding the roles of intestinal transporters and hepatic processing, to enable more precise and effective supplementation strategies.

Molecular basis of α-tocopherol’s antioxidant function

α-Tocopherol serves as a crucial lipid-soluble antioxidant in animal biology because most other vitamin E vitamers are not readily retained in the body. Its principal role lies in preserving cellular integrity by protecting polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within biological membranes from oxidative degradation (Jomova et al. Reference Jomova, Alomar and Alwasel2024; Ponnampalam et al. Reference Ponnampalam, Kiani and Santhiravel2022). Oxidative stress – caused by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense system – is a central mechanism underlying cellular damage and dysfunction in both health and disease (Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Gordillo and Pelletier2023b). The potent antioxidant properties of α-tocopherol make it a cornerstone of nutritional strategies aimed at improving animal performance, health, and product quality (Saldeen and Saldeen Reference Saldeen and Saldeen2005). Recent studies have further clarified the molecular mechanisms by which α-tocopherol exerts its antioxidant function, including its interaction with lipid radicals, regeneration pathways, structural positioning in membranes, and its role in modulating redox-sensitive signaling.

Molecular structure and lipid membrane localization

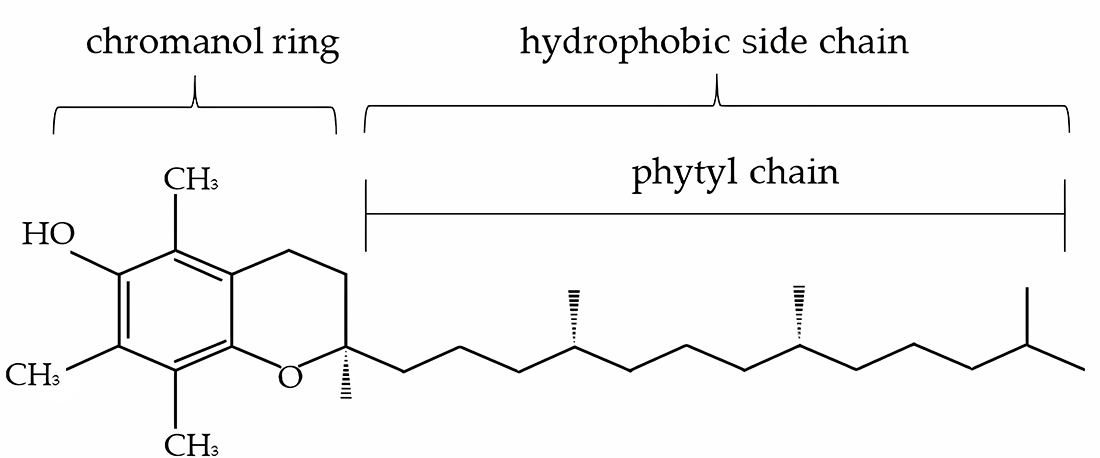

The antioxidant function of α-tocopherol is tightly linked to its unique molecular structure, which consists of a chromanol ring with a hydroxyl group at position 6 and a hydrophobic phytyl side chain (Figure 1). The hydroxyl group donates a hydrogen atom to neutralize lipid peroxyl radicals, while the lipophilic side chain anchors the molecule within the hydrophobic core of cell membranes and lipoproteins (Ayala et al. Reference Ayala, Muñoz and Argüelles2014; Wang and Quinn Reference Wang and Quinn1999). This amphipathic nature allows α-tocopherol to be optimally positioned at the membrane–lipid–aqueous interface, where lipid peroxidation is initiated and propagated (Burton and Ingold Reference Burton and Ingold1981).

Figure 1. The structure of α-tocopherol (adapted from Szewczyk et al. Reference Szewczyk, Chojnacka and Górnicka2021).

The chromanol head group faces the aqueous phase or polar regions of the lipid bilayer, facilitating interactions with ROS and radical species (Leng et al. Reference Leng, Kinnun and Marquardt2015). This spatial orientation is essential for its efficiency in intercepting lipid peroxyl radicals and terminating radical chain reactions in lipid environments (Kilicarslan et al. Reference Kilicarslan, Fuwad and Lee2024). The side chain, composed of saturated isoprenoid units, ensures high membrane retention and proper orientation within the lipid bilayer, particularly in membranes enriched with unsaturated phospholipids (Kavousi et al. Reference Kavousi, Novak and Tong2021; Quinn Reference Quinn2007; Wang and Quinn Reference Wang and Quinn1999).

Free radical scavenging and chain-breaking activity

At the molecular level, α-tocopherol functions as a chain-breaking antioxidant and is recognized as the predominant chain-breaking antioxidant in vivo (Burton et al. Reference Burton, Joyce and Ingold1982). α-Tocopherol terminates the propagation phase of lipid peroxidation by reacting with lipid peroxyl (LOO•) and alkoxyl (LO•) radicals, yielding lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) and the relatively stable tocopheroxyl radical (α-Toc•) (Bartesaghi et al. Reference Bartesaghi, Wenzel and Trujillo2010; Lebold and Traber Reference Lebold and Traber2014; Niki Reference Niki2021; Yamauchi Reference Yamauchi2007):

This hydrogen donation neutralizes peroxyl radicals before they can abstract hydrogen from neighboring lipid molecules, halting the self-propagating lipid peroxidation cycle (Carocho and Ferreira Reference Carocho and Ferreira2013). The resulting α-tocopheroxyl radical is less reactive and may either be excreted or regenerated to its active form (Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a; Traber and Atkinson Reference Traber and Atkinson2007).

Regeneration of α-tocopherol

A key aspect of α-tocopherol’s antioxidant function is its recycling by other antioxidants, notably ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and ubiquinol (coenzyme Q) (Kagan et al. Reference Kagan, Fabisiak and Quinn2000; May et al. Reference May, Qu and Mendiratta1998). This synergistic interaction forms the basis of the antioxidant network, wherein water-soluble antioxidants (vitamin C) regenerate lipid-soluble ones (α-tocopherol), sustaining antioxidant capacity (Traber and Stevens Reference Traber and Stevens2011). Ascorbic acid reduces α-tocopheroxyl radical back to α-tocopherol via electron donation:

This redox cycling is crucial in biological systems, where continued regeneration of α-tocopherol amplifies its protective effects, especially in tissues with high oxidative metabolism like the liver, muscle, and reproductive organs (Figure 2). Without adequate regenerating cofactors, α-tocopheroxyl radicals may undergo irreversible oxidation, forming tocopheryl quinones, which are biologically inactive (Khallouki et al. Reference Khallouki, Owen and Akdad2020; Liebler Reference Liebler1993; Packer and Obermüller-Jevic Reference Packer and Obermüller-Jevic2002).

Figure 2. The antioxidant network showing the interaction among α-tocopherol, vitamin C, and thiol redox cycles (Rimbach et al. Reference Rimbach, Moehring and Huebbe2010); PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid, ROOH: lipid peroxide, ROH: alcohol, ROO•: peroxyl radical; RO•: alkoxyl radical, O2•−: superoxide anion radical, NAD(P)H: nicotinamide-adenine-dinucleotide-(phosphate).

Prevention of lipid peroxidation and membrane integrity

The peroxidation of membrane PUFAs compromises membrane fluidity, permeability, and function (Bresciani et al. Reference Bresciani, Mânica da Cruz, González-Gallego and Makowski2015). In animals, cellular membranes rich in arachidonic acid and linoleic acid are particularly susceptible to ROS attack, especially under stress conditions such as heat, high metabolic rates, or pathogen challenge (Mercola and D’Adamo Reference Mercola and D’Adamo2023; Naudí et al. Reference Naudí, Jové and Ayala2013; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Sun and Luo2024).

By scavenging peroxyl radicals and preventing PUFA oxidation, α-tocopherol preserves the structural integrity and functionality of membranes (Kilicarslan et al. Reference Kilicarslan, Fuwad and Lee2024; Figure 3). This includes maintaining membrane-bound enzyme activity, ion gradients, receptor function, and transport processes (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Harroun and Wassall2010; Brigelius-Flohé Reference Brigelius-Flohé2009).

Figure 3. Antioxidant role of vitamin E in mitigating ROS-driven lipid oxidation in cell membrane models (Kilicarslan et al. Reference Kilicarslan, Fuwad and Lee2024).

Gene expression and modulation of redox-sensitive signaling pathways

α-Tocopherol plays a critical role in regulating the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress response, immune function, and inflammation across livestock species (Korošec et al. Reference Korošec, Tomažin and Horvat2017; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Meydani and Wu2019; Ulatowski et al. Reference Ulatowski, Dreussi and Noy2012). In poultry and pigs, dietary supplementation with α-tocopherol in the form of DL-α-tocopheryl acetate has been shown to influence gene expression in key tissues, including the liver, intestine, and spleen. This includes the upregulation of antioxidant defense genes, notably encoding superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, alongside context-dependent modulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, depending on the animal’s physiological status and exposure to stressors (Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Block and Ciraci2012; Laviano et al. Reference Laviano, Gómez and Núñez2024; Silva-Guillen et al. Reference Silva-Guillen, Arellano and Boyd2020; Surai et al. Reference Surai, Kochish and Fisinin2017; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li and Zhu2021).

Beyond its classical role as a chain-breaking antioxidant, α-tocopherol exerts non-antioxidant regulatory effects by influencing redox-sensitive signaling pathways (Liao et al. Reference Liao, Börmel and Müller2024; Zingg Reference Zingg2019). It modulates gene expression associated with apoptotic and immune responses through the regulation of key transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein-1 (Azzi et al. Reference Azzi, Gysin and Kempná2004a, Reference Azzi, Gysin and Kempná2004b; Blaner et al. Reference Blaner, Shmarakov and Traber2021; Sharma and Vinayak Reference Sharma and Vinayak2011). These effects are believed to involve redox-dependent modulation of signaling cascades and nuclear transcriptional activity.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that α-tocopherol can inhibit protein kinase C (PKC) activity, suppress the expression of cyclooxygenase-2, and reduce the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules – mechanisms that are independent of its antioxidant properties (Noguchi et al. Reference Noguchi, Hanyu and Nonaka2003; Reiter et al. Reference Reiter, Jiang and Christen2007; Ricciarelli et al. Reference Ricciarelli, Tasinato and Clément1998). These non-antioxidant actions suggest a broader physiological role for α-tocopherol in regulating inflammation and cellular stress responses in animals (Blaner et al. Reference Blaner, Shmarakov and Traber2021).

Recent studies have reported that phenolics can bind directly to cellular kinases, which may be important for improving reproductive capacity (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Yang and Gong2024a, Reference Hu, Yang and Wang2024b; Mhawish and Komarnytsky et al. Reference Mhawish and Komarnytsky2025; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Hu and Yao2024). The antioxidant mechanism of vitamin E is similar to phenolics in that it donates a hydrogen atom to neutralize free radicals, contributing to the protection of cellular components from oxidative damage. However, current evidence for α-tocopherol suggests its effects on kinases are mainly indirect, through modulation of redox signaling and transcription factors, rather than direct binding (Zingg Reference Zingg2007). These indirect actions may influence signaling pathways such as PKC and transcriptional regulators like B-lymphoma Mo-MLV (Moloney murine leukemia virus) insertion region 1, a key repressor that controls cell proliferation and differentiation – processes essential for steroidogenesis and gamete maturation (Betti et al. Reference Betti, Ambrogini and Minelli2011; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Wu and Wang2023). This functional similarity in antioxidant action provides a rationale for comparing phenolics and vitamin E in the context of reproductive physiology, despite structural differences. Further research is needed to clarify whether α-tocopherol can exert kinase-mediated effects similar to phenolics in animal systems.

The extent and nature of gene expression changes induced by α-tocopherol are modulated by several factors, including the dietary dose, the specific form administered (natural vs. synthetic), tissue-specific distribution and retention, and the duration of supplementation (Barella et al. Reference Barella, Muller and Schlachter2004; Kim and Han Reference Kim and Han2019; Rimbach et al. Reference Rimbach, Moehring and Huebbe2010; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). Recent transcriptomic studies underscore α-tocopherol’s complex biological functions, particularly its role in enhancing cellular resilience and maintaining immunological homeostasis – functions that extend beyond classical antioxidant activity. For a detailed discussion on the emerging epigenetic roles of vitamin E, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulation by noncoding RNAs – illustrated with examples from swine – readers are referred to the review by Shastak and Pelletier (Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a).

Role in animal health and product quality

The molecular mechanisms described above translate into tangible outcomes in animal production systems. Dietary supplementation with α-tocopherol, particularly as DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, has been shown to enhance immune responsiveness, reduce oxidative damage during stress, improve reproductive performance, and extend meat shelf-life by preventing lipid oxidation post-mortem (Ebeid et al. Reference Ebeid, Zeweil and Basyony2013; Kakhki et al. Reference Kakhki, Bakhshalinejad and Shafiee2016; Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Wang and Zhang2021).

For example, α-tocopherol accumulation in muscle tissues correlates with reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) formation and improved oxidative stability of meat, contributing to better color, flavor, and consumer acceptance (Jacondino et al. Reference Jacondino, Chec and Tontini2022; Leskovec et al. Reference Leskovec, Levart and Nemec Svete2018; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Wang and Zhang2021). In poultry, α-tocopherol supplementation supports fertility, embryonic viability, and chick quality by safeguarding the integrity of yolk lipids and reproductive tissues (Surai and Kochish Reference Surai and Kochish2019). Recent studies also highlight the importance of optimizing α-tocopherol bioavailability and tissue distribution to maximize these health and product quality benefits, especially under conditions of environmental or metabolic stress (Haga et al. Reference Haga, Ishizaki and Roh2021; Van Kempen et al. Reference Van Kempen, Benítez Puñal and Huijser2022, Reference Van Kempen, Reijersen and de Bruijn2016). However, the magnitude of these effects can vary depending on the form of α-tocopherol used, the animal species, and the specific production context, underscoring the need for tailored supplementation strategies.

Bioavailability

Understanding the bioavailability of vitamin E

In farm animals, bioavailability refers to the extent to which dietary vitamin E is absorbed, transported, and utilized to meet physiological and production requirements. For clarity, and as noted in the introduction, this review defines vitamin E as encompassing all, or at least several, of its vitamers, always including α-tocopherol. When bioavailability studies compare synthetic DL-α-tocopheryl acetate with natural α-tocopheryl acetate or free α-tocopherol, the comparison involves different forms of the same vitamer (α-tocopherol). However, when mixed natural tocopherols are compared with the synthetic form, the comparison reflects natural vitamin E (containing multiple vitamers) versus synthetic α-tocopheryl acetate.

Building on this definition, it is important to recognize that bioavailability is not determined solely by the chemical form of vitamin E. Recent studies highlight additional factors, including dietary composition, gastrointestinal physiology, and species-specific differences in digestive efficiency and metabolic pathways (Desmarchelier and Borel Reference Desmarchelier and Borel2017; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024a; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Khan and Ma2021). Interactions with other nutrients such as fat, selenium, and vitamin C also play a role (Liao et al. Reference Liao, Omage and Börmel2022). A key determinant is the hepatic α-TTP, which selectively retains RRR-α-tocopherol and 2R-stereoisomers in the circulation while eliminating other stereoisomers (Traber Reference Traber2007).

Situation in different animal species

The bioavailability of α-tocopherol varies considerably across farm animal species, reflecting species-specific differences in gastrointestinal physiology, dietary composition, and metabolic demands related to intake and utilization (Dersjant-Li and Peisker Reference Dersjant-Li and Peisker2010; Leal et al. Reference Leal, Jensen and Bello2019; Vagni et al. Reference Vagni, Saccone and Pinotti2011).

Ruminants: α-Tocopherol is a vital micronutrient for ruminants, functioning as a potent antioxidant and supporting immune competence, muscle integrity, reproductive performance, and disease resistance, especially under stress or when fed vitamin E-depleted forages (Li et al. Reference Li, Lin and Moonmanee2024; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Khan and Ma2021). Rumen microbial activity can degrade dietary vitamin E before absorption, reducing bioavailability (Lashkari et al. Reference Lashkari, Panah and Weisbjerg2023; Masoero et al. Reference Masoero, Moschini and Bertuzzi1997; Schäfers et al. Reference Schäfers, Meyer and von Soosten2018). Tissue concentrations of α-tocopherol are influenced by dosage, timing, and supplementation duration (Leal et al. Reference Leal, Jensen and Bello2019). Comparative studies show that natural D-α-tocopherol yields higher plasma concentrations than synthetic all-rac-α-tocopherol, with the latter showing 12–40% lower bioavailability (Hidiroglou Reference Hidiroglou1989; Hidiroglou et al. Reference Hidiroglou, Batra and Zhao1997; Meglia et al. Reference Meglia, Jensen and Lauridsen2006; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, Hogan and Wyatt2009). However, data on esterified versus free forms in ruminants remain limited, highlighting a need for further research.

Poultry: α-Tocopherol is essential for maintaining egg quality and enhancing the oxidative stability of broiler meat. Heat stress and other environmental challenges increase the demand for α-tocopherol, requiring higher dietary supplementation (Dalólio et al. Reference Dalólio, Albino and Lima2015). Free α-tocopherol is generally more bioavailable than α-tocopheryl acetate due to more efficient absorption and distribution (Van Kempen et al. Reference Van Kempen, Benítez Puñal and Huijser2022). Broiler studies show that DL-α-tocopherol leads to higher tissue concentrations than DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, with the latter showing up to fourfold lower bioavailability. Nano-formulated all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate improves bioavailability, and natural D-α-tocopherol outperforms synthetic forms in retention, meat quality, and antioxidant capacity (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Niu and Zheng2016; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Li and Guo2024).

Swine: In pigs, α-tocopherol supports immune function, reproductive performance, and meat quality. Natural α-tocopherol supplementation results in higher plasma and tissue concentrations than synthetic forms (Wilburn et al. Reference Wilburn, Mahan and Hill2008). For example, RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate may be about twice as bioavailable as all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate in sows (Lauridsen et al. Reference Lauridsen, Engel and Craig2002), and finishing pigs fed the natural form show significantly greater serum and tissue levels (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mahan and Hill2009). However, trials that use blood α-tocopherol concentration as a response parameter for comparing bioavailability should be interpreted with caution, as circulating vitamin E does not always reliably reflect tissue accumulation (Ullrey et al. Reference Ullrey, Moore-Doumit and Bernard2013).

Fish: In aquaculture, α-tocopherol bioavailability is crucial for growth and resistance to oxidative stress (Asencio-Alcudia et al. Reference Asencio-Alcudia, Sepúlveda-Quiroz and Pérez-Urbiola2023). Lipid-rich diets enhance absorption, but DL-α-tocopheryl acetate stability during feed processing (extrusion) may sometimes be a challenge (Marchetti et al. Reference Marchetti, Tossani and Bauce1999). Higher dietary inclusion is often needed to offset processing losses and meet physiological demands (El-Sayed and Izquierdo Reference El-Sayed and Izquierdo2022; Najafabadi et al. Reference Najafabadi, Mohammadiazarm and Mozanzadeh2025). However, comparative data on different α-tocopherol forms in fish are limited, highlighting a research gap.

Challenges and pharmacokinetic approaches in assessing vitamin E and α-tocopherol bioavailability

Assessing vitamin E and/or α-tocopherol bioavailability in animal nutrition is complicated by chemical variability in feeds (α-tocopheryl acetate vs. free α-tocopherol), species-specific gastrointestinal physiology, and metabolic differences. Feeding trials often differ in approaches, dosing regimen, duration, administration method, α-tocopherol type, dietary fat content, and the bioavailability parameter measured (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparative bioavailability (BA) of α-tocopherol sources in various animal species using the simple ratio and slope ratio approach

* Based on the slope ratio (linear regression).

A further limitation is the lack of a universal biomarker. Plasma α-tocopherol is commonly measured but does not always reflect tissue deposition or functional antioxidant capacity, as only about 1% of body α-tocopherol is in the blood and levels are influenced by lipid concentrations (Horwitt et al. Reference Horwitt, Harvey and Dahm1972; Thurnham et al. Reference Thurnham, Davies and Crump1986; Ulatowski et al. Reference Ulatowski, Parker and Warrier2014). Dietary factors such as fat composition, PUFA levels, and interactions with other antioxidants (e.g., selenium) also impact absorption and utilization (Rice and Kennedy Reference Rice and Kennedy1988; Schwenke and Behr Reference Schwenke and Behr1998; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a).

Rather than focusing on traditional simple ratio or slope methods (Table 2), recent research and reviews recommend a pharmacokinetic approach – evaluating absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of α-tocopherol (Mohd Zaffarin et al. Reference Mohd Zaffarin, Ng and Ng2020; Novotny et al. Reference Novotny, Fadel and Holstege2012; Qureshi et al. Reference Qureshi, Khan and Silswal2016; Saldanha and Vale et al. Reference Saldanha and Vale2023; Tegenge and Mitkus et al. Reference Tegenge and Mitkus2015). Key parameters include the rate and extent of intestinal absorption, hepatic processing (including α-TTP selectivity), plasma and tissue kinetics (e.g., area under the curve, tissue retention), and excretion rates (Figure 4). Multi-biomarker strategies that combine plasma kinetics, tissue levels, and oxidative stress markers may provide a more comprehensive and functionally relevant assessment of vitamin E bioavailability and biopotency in animals.

Figure 4. Plasma level time curves for different sources of vitamin E (adapted from Stielow et al. Reference Stielow, Witczyńska and Kubryń2023). The α-tocopherol is delivered directly into the systemic circulation via intravenous injection, ensuring 100% bioavailability and immediate achievement of maximum plasma concentration (c max, t max = 0 min). Orally administered vitamin E sources achieve a bioavailability level substantially lower than 100% due to incomplete absorption and/or elimination during the first pass through the liver. Additionally, due to the indirect path to the plasma, they are characterized by a long time lag. Different dosage forms may result in differences in c max and t max.

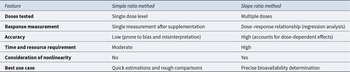

Table 2. Key differences between the simple ratio and slope ratio methods

Given the complexity and variability across species and production systems, future research should prioritize standardized pharmacokinetic models and species-specific correction factors to improve the reliability and comparability of bioavailability data.

Forms of α-tocopherol in animal nutrition: Free α-tocopherol vs. α-tocopheryl acetate

The form in which α-tocopherol is supplied in animal diets has a significant impact on its bioavailability, stability, and physiological effectiveness. The two primary dietary forms are free (unesterified) α-tocopherol and α-tocopheryl acetate, each with distinct advantages and limitations that must be considered in practical nutrition strategies (Hoppe and Krennrich Reference Hoppe and Krennrich2000; Vagni et al. Reference Vagni, Saccone and Pinotti2011).

Free α-tocopherol is the biologically active, unesterified form found naturally in plant oils and some feed ingredients. It is directly bioavailable, as it does not require enzymatic hydrolysis for absorption. However, its bioavailability can vary depending on the ingredient matrix; for example, α-tocopherol embedded in plant cell membranes may be less accessible for absorption (Chungchunlam and Moughan Reference Chungchunlam and Moughan2023; Torres et al. Reference Torres, de Oliveira Sartori and de Souza Silva2022). Free α-tocopherol is also highly susceptible to oxidative degradation during feed processing and storage, as well as within the digestive tract (Balakrishnan and Goodrich Schneider Reference Balakrishnan and Goodrich Schneider2023; Capitani et al. Reference Capitani, Mateo and Nolasco2011). This instability limits its practical use in commercial feed formulations, and as a result, the natural α-tocopherol content of feed ingredients is often not considered in diet formulation.

α-Tocopheryl acetate is an esterified, chemically stabilized form that is widely used in animal feeds due to its resistance to oxidation and suitability for long-term storage (Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024a; Yang and McClements Reference Yang and McClements2013). Upon ingestion, α-tocopheryl acetate must be hydrolyzed by intestinal esterases to release free α-tocopherol, which can then be absorbed (Brisson et al. Reference Brisson, Castan and Fontbonne2008). This additional enzymatic step can delay absorption and moderately reduce bioavailability compared to free α-tocopherol, particularly in young or enzyme-deficient animals such as weaned piglets (Amazan et al. Reference Amazan, Rey and Fernández2012; Lauridsen et al. Reference Lauridsen, Hedemann and Jensen2001; Lauridsen and Jensen Reference Lauridsen and Jensen2005; Pietro et al. Reference Pietro, Verlhac and Calvo2019). Nevertheless, its superior stability makes it the preferred form for most commercial applications.

Comparative studies indicate that free α-tocopherol, when available and stable, is more efficiently absorbed and results in higher plasma and tissue concentrations than α-tocopheryl acetate (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Niu and Zheng2016; Van Kempen et al. Reference Van Kempen, Benítez Puñal and Huijser2022). However, the practical challenges of preserving free α-tocopherol in feed and ensuring its bioaccessibility often outweigh these benefits. Recent innovations, such as encapsulation and nano-formulation, aim to improve the stability and bioavailability of both forms, but further validation in livestock production systems is needed (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Wang and Alalaiwe2019; Mohd Zaffarin et al. Reference Mohd Zaffarin, Ng and Ng2020; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Li and Guo2024).

In summary, the choice between free α-tocopherol and α-tocopheryl acetate should be guided by a balance between bioavailability and stability, as well as the specific needs and digestive capacities of the target animal species. Ongoing research into novel delivery systems and a better understanding of species-specific digestive physiology will be essential for optimizing vitamin E supplementation strategies in animal nutrition.

Critical assessment and knowledge gaps

Despite significant progress in understanding the bioavailability of vitamin E and/or α-tocopherol, several critical gaps remain that require further investigation and synthesis.

Variability across species and physiological states remains insufficiently explained. Although general trends are established, the mechanisms underlying interspecies differences – such as the impact of rumen microbial activity in cattle or gut microbiota in monogastrics – are not fully understood (Lashkari et al. Reference Lashkari, Panah and Weisbjerg2023; Shastak and Pelletier, Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024c). Likewise, data on altered vitamin E requirements during pregnancy, lactation, or stress are limited and inconsistent.

The influence of dietary components beyond fat, such as fiber and secondary plant metabolites, on α-tocopherol bioavailability is poorly characterized. Synergistic effects with other antioxidants (e.g., vitamin C, selenium) are not well quantified, complicating the design of optimal supplementation strategies (Leskovec et al. Reference Leskovec, Levart and Nemec Svete2018; Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a).

Although α-tocopheryl acetate is the most stable and widely used form, its efficacy relative to free α-tocopherol under different conditions is still debated. Novel delivery systems (e.g., encapsulation, nano-emulsions) show promise for improving bioavailability, but require further validation in practical livestock settings (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Wang and Alalaiwe2019; Mohd Zaffarin et al. Reference Mohd Zaffarin, Ng and Ng2020).

Genetic and epigenetic factors affecting α-tocopherol bioavailability and tissue distribution remain largely unexplored (Haga et al. Reference Haga, Ishizaki and Roh2021; Rimbach et al. Reference Rimbach, Moehring and Huebbe2010; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). Further research into how genetic variation influences key proteins such as α-TTP or lipoprotein receptors could enable more individualized nutrition strategies.

Environmental and management factors – including heat stress, disease, and housing – are known to affect oxidative stress and α-tocopherol demand (Calik et al. Reference Calik, Emami and White2022; Oke et al. Reference Oke, Akosile and Oni2024; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Peng2023), but their impact on bioavailability and utilization is not well defined. Addressing these gaps will be essential for developing precise, evidence-based supplementation recommendations for diverse production conditions.

Biopotency

Understanding biopotency in vitamin E and/or α-tocopherol

Biopotency, in the context of (micro)nutrients and bioactive compounds, refers to the ability of a substance to produce a biological effect when consumed (EMA 1999). Specifically, for drugs, vitamins, and other essential micronutrients, biopotency refers to the amount of an active ingredient, expressed as its concentration or dose, which determines the extent to which the compound can produce its physiological effects at the cellular or systemic level (Guilding et al. Reference Guilding, White and Cunningham2024). Biopotency is a key concept for understanding how efficiently a micronutrient supports health and metabolic processes in animals.

In the case of α-tocopherol, the primary and most biologically active vitamer of vitamin E, biopotency encompasses its ability to act as an antioxidant, protect lipids and cell membranes from oxidative damage, support immune function, and reduce the risk of diseases linked to oxidative stress (Brigelius-Flohe et al. Reference Brigelius-Flohe, Kelly and Salonen2002; Traber and Atkinson Reference Traber and Atkinson2007). Determining the biopotency of α-tocopherol in different animal species is essential for setting dietary recommendations and supplementation strategies.

In the context of vitamin E, biopotency refers to the relative ability of different vitamin E forms – including various vitamers and stereoisomers – to produce beneficial biological effects, such as antioxidant protection or immune support. Comparing the biopotency of RRR-α-tocopherol to other stereoisomers or to all-rac-α-tocopherol requires functional parameters (e.g., physiological or health outcomes), since all-rac-α-tocopherol is a synthetic mixture with only a fraction of the biologically preferred 2R-stereoisomers.

Situation in different animal species

α-Tocopherol is widely recognized as the most biologically active form of vitamin E across many animal species. However, variations in the biopotency of different vitamin E vitamers and isomers can be observed among various species (Szewczyk et al. Reference Szewczyk, Chojnacka and Górnicka2021). These differences are influenced by factors such as α-TTP in the liver, tissue-specific distribution and metabolic pathways (Brigelius-Flohe Reference Brigelius-Flohe2006; EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP) 2010; Rimbach et al. Reference Rimbach, Moehring and Huebbe2010).

Additionally, the efficiency of α-tocopherol and its vitamers absorption and transport varies between species and among individuals of the same species, which can influence its overall biopotency (Jensen and Lauridsen Reference Jensen and Lauridsen2007; Schmölz et al. Reference Schmölz, Birringer and Lorkowski2016). This variability between species underscores the complexity of evaluating the precise biopotency of α-tocopherol and its vitamers in animals and the necessity for species-specific studies to understand the nuanced roles of this vitamin in diverse physiological contexts (Jensen and Lauridsen Reference Jensen and Lauridsen2007; Schmölz et al. Reference Schmölz, Birringer and Lorkowski2016). Little is currently known about biopotency across different farm animal species (Cook-Mills and McCary Reference Cook-Mills and McCary2010; Hoppe and Krennrich Reference Hoppe and Krennrich2000; Vagni et al. Reference Vagni, Saccone and Pinotti2011).

Vitamers and stereoisomers

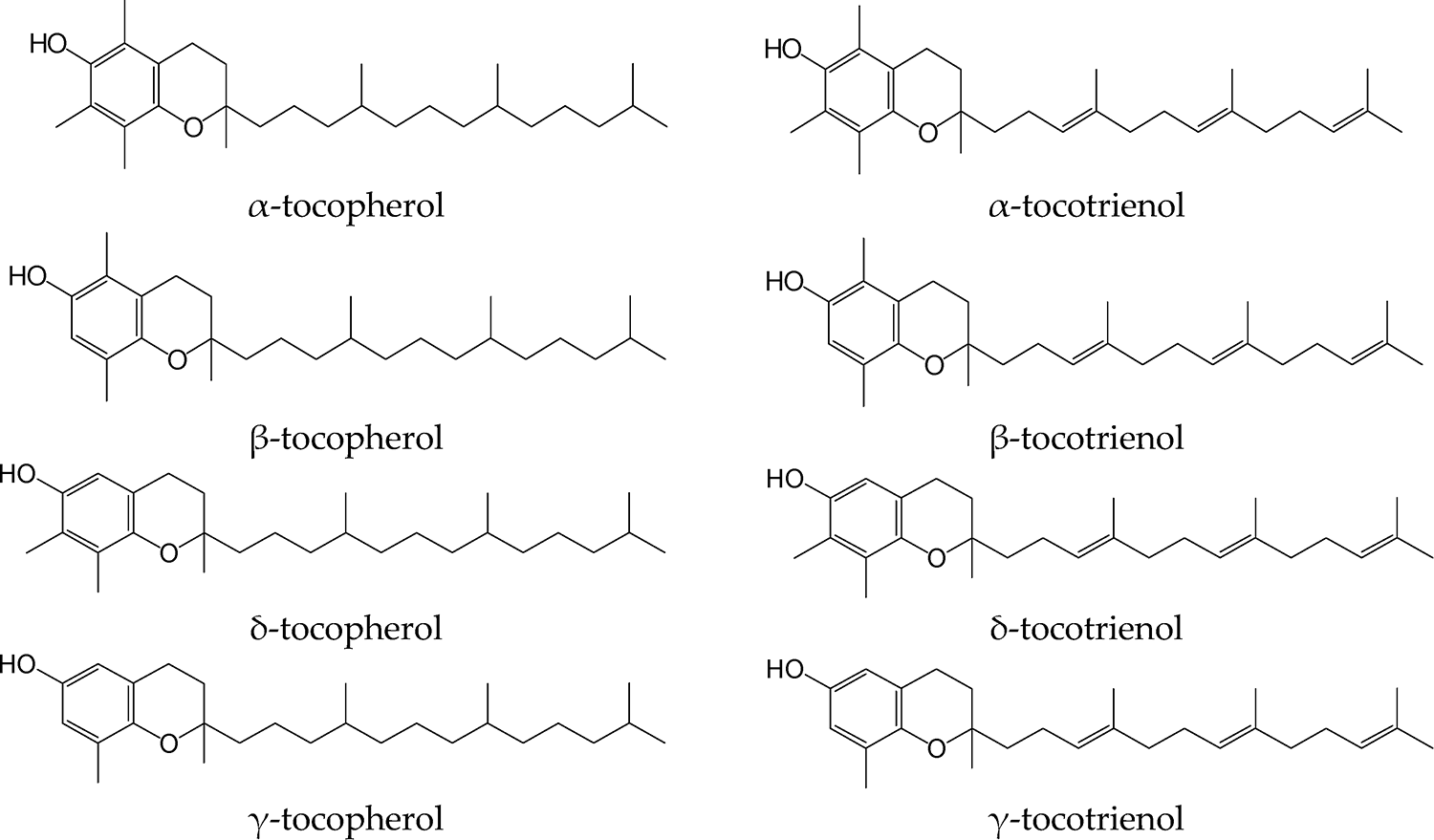

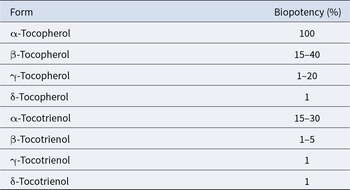

Vitamin E comprises eight structurally related vitamers: four tocopherols (α, β, γ, and δ) and four tocotrienols (α, β, γ, and δ), each with distinct biological activity and tissue distribution (Figure 5; Table 3). Tocotrienols, while antioxidants, generally have lower biopotency in classical assays and limited practical relevance in animal nutrition.

Figure 5. Vitamin E vitamers (Reboul Reference Reboul2017).

Table 3. Comparative biopotency of vitamin E vitamers in animal models using functional endpoints (AWT 2002)

Natural α-tocopherol occurs exclusively as the RRR stereoisomer, while synthetic all-rac-α-tocopherol is a racemic mixture of eight stereoisomers (RRR, RRS, RSR, RSS, SRR, SRS, SSR, and SSS), each comprising 12.5% of the total (Weiser et al. Reference Weiser, Riss and Kormann1996; Figure 6). All-rac-α-tocopherol, typically as tocopheryl acetate, is the predominant form used in the feed industry.

Figure 6. The eight stereoisomers of synthetic α-tocopherol.

Early studies (Weiser and Vecchi Reference Weiser and Vecchi1982) showed that 2R stereoisomers are generally more biologically active than 2S forms (Table 4). A biopotency ratio of ∼1.36:1 between RRR-α-tocopherol and all-rac-α-tocopherol (per unit weight) has been widely accepted, but more recent research suggests that biopotency may vary by tissue and over time (Ingold et al. Reference Ingold, Burton and Foster1987; Ranard and Erdman, Reference Ranard and Erdman2018; Weiser et al. Reference Weiser, Riss and Kormann1996).

Table 4. Biopotency of individual all-rac-α-tocopherol stereoisomers in rats (fetal resorption/gestation test) (Weiser and Vecchi Reference Weiser and Vecchi1982)

Organ- and species-specific patterns of stereoisomer distribution have been observed in mink, poultry, swine, and ruminants, often reflecting hepatic α-TTP selectivity and bioavailability rather than direct differences in biological activity (Hymøller et al. Reference Hymøller, Lashkari and Clausen2018; Lauridsen et al. Reference Lauridsen, Engel and Craig2002; Leal et al. Reference Leal, Jensen and Bello2019; Peisker et al. Reference Peisker, Jensen and Halle2014).

The selective binding of α-TTP in the liver is the main mechanism underlying biopotency differences among stereoisomers (Ingold et al. Reference Ingold, Burton and Foster1987; Kaneko et al. Reference Kaneko, Kiyose and Ueda2000; Kiyose et al. Reference Kiyose, Kaneko and Muramatsu1999; Traber et al. Reference Traber, Burton and Ingold1990, Reference Traber, Ramakrishnan and Kayden1994). While only RRR- and other 2R-α-tocopherol stereoisomers are considered fully effective in humans (Eggersdorfer et al. Reference Eggersdorfer, Schmidt and Péter2024), data for nonhuman species remain limited. A summary of biopotency studies using functional biological endpoints is provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Comparative biopotency of RRR- and all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate in different animal species based on biological activity assays

Vitamin E requirements in different animal species

Determining vitamin E requirements in animals is a complex task that goes beyond preventing overt clinical deficiency. In the European Union, only all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate and RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate are officially classified as vitamin E sources, disregarding potential physiological roles of other vitamers or their esters (EFSA, 2010). To avoid confusion, the requirement estimates and recommendations presented in this review refer exclusively to these two forms recognized by EFSA. However, based on the definitions adopted in this review, these requirements should conceptually be expressed in terms of α-tocopherol or α-tocopheryl acetate.

Historically, requirement standards were based on classical bioassays (e.g., reproductive performance in rats, prevention of muscular dystrophy in livestock), but these models do not fully capture the broader physiological roles of vitamin E under current production systems and stressors (Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a).

Furthermore, it involves accounting for chemical diversity among vitamin E forms, their differences in biological activity, the interplay between bioavailability and biopotency, and physiological demands under varied nutritional and environmental conditions (Hidiroglou et al. Reference Hidiroglou, Cave and Atwal1992; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a; Vagni et al. Reference Vagni, Saccone and Pinotti2011).

The League of Nations Health Organization, in 1941, defined 1 mg of DL-α-tocopheryl acetate as equivalent to 1 International Unit (IU). However, the compound used at that time is no longer available, and current commercial preparations may differ in biological activity due to differences in stereochemistry (Ames Reference Ames1971). This uncertainty, particularly regarding the asymmetric carbon atoms in synthetic DL-α-tocopherol, continues to influence how requirements are evaluated (Bieri and McKenna Reference Bieri and McKenna1981).

Integrating biopotency and bioavailability

Vitamin E requirements for companion and farm animals are stated in IU to reflect the biological activity of different compounds. This practice implicitly incorporates both biopotency (efficacy in vivo) and bioavailability (absorption and tissue utilization). To standardize comparisons across different chemical forms, specific conversion factors are applied (Bieri and McKenna Reference Bieri and McKenna1981):

• 1 mg of D-α-tocopherol = 1.49 IU

• 1 mg of D-α-tocopheryl acetate = 1.36 IU

• 1 mg of DL-α-tocopherol = 1.1 IU

• 1 mg of DL-α-tocopheryl acetate = 1.0 IU.

As feeds are predominantly formulated with synthetic form, namely DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, higher inclusion levels are needed to achieve similar biological outcomes compared to natural D-α-tocopherol.

Factors influencing requirements

(1) Diet composition

Vitamin E interacts closely with other dietary components. High levels of PUFAs accelerate oxidative stress, increasing vitamin E turnover and the need for supplementation (Hidiroglou et al. Reference Hidiroglou, Cave and Atwal1992; Lauridsen Reference Lauridsen2019; Raederstorff et al. Reference Raederstorff, Wyss and Calder2015; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). Vitamin E also acts synergistically with selenium and vitamin C, and imbalances can affect requirement levels (Kotit et al. Reference Kotit, Omar and Srour2025; Shastak et al. Reference Shastak, Obermueller-Jevic and Pelletier2023a).

(2) Form of supplementation

Esterified forms, particularly α-tocopheryl acetate, are more stable in feed but must be hydrolyzed enzymatically in the gut before absorption. Young, diseased, or stressed animals may have impaired hydrolysis capacity, which in turn reduces effective bioavailability (Van Kempen et al. Reference Van Kempen, Benítez Puñal and Huijser2022). Requirements must therefore account for both chemical form and physiological state.

(3) Physiological status

Reproductive animals, neonates, and high-yielding livestock have greater vitamin E demands due to increased oxidative metabolism and tissue turnover (Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2025a). For example, neonatal animals have immature antioxidant systems and low vitamin E tissue reserves, increasing reliance on maternal transfer or early dietary supplementation (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Masters and Ferguson2014).

(4) Environmental and management stress

Environmental stressors – heat, transport, high stocking density, and infection – elevate oxidative damage and suppress immune function (Abo-Al-Ela et al. Reference Abo-Al-Ela, El-Kassas and El-Naggar2021). In these situations, vitamin E needs exceed baseline recommendations. Practical nutrition often includes higher levels to buffer stress responses and improve performance under intensive management (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Celi and Luery2015; Selvam et al. Reference Selvam, Saravanakumar and Suresh2015; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024a; Webel et al. Reference Webel, Mahan and Johnson1998).

Toward functional requirement models

Traditional recommendations focus on preventing clinical deficiencies such as encephalomalacia in poultry, muscular dystrophy in ruminants, or reproductive failure in swine. However, modern animal production increasingly demands functional sufficiency, where optimal health, immune response, product quality, and stress tolerance are targeted outcomes (Ducrot et al. Reference Ducrot, Barrio and Boissy2024; Godde et al. Reference Godde, Mason-D’Croz and Mayberry2021; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2023b).

Markers like plasma α-tocopherol levels provide an estimate of vitamin status but are not always predictive of performance or resilience (Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak, Pelletier and Simões2025b). Therefore, emerging approaches assess:

• Oxidative stress biomarkers (e.g., MDA)

• Vaccine response and antibody production

• Fertility indices

• Meat lipid oxidation and shelf-life.

These indicators allow for refining requirements based on desired physiological or production outcomes. Consequently, feeding strategies have been routinely exceeding minimal requirement values to improve robustness, efficiency, and quality, particularly in commercial settings (Schelling et al. Reference Schelling, Roeder and Garber1995; Shastak and Pelletier Reference Shastak and Pelletier2024a).

Vitamin E requirements in animals cannot be universally defined, as they are influenced by a range of biological and environmental factors, including species, developmental stage, diet composition, stress exposure, and the specific chemical form of vitamin E provided.

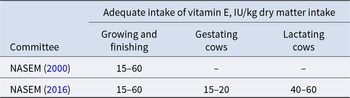

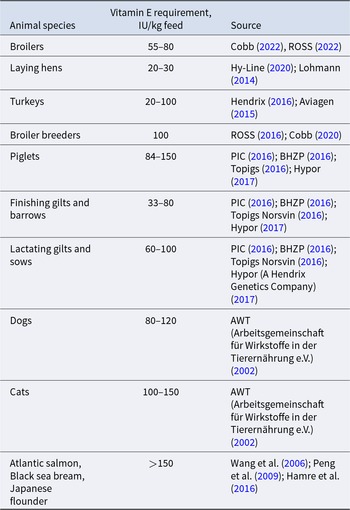

While classical requirement estimates values of scientific committees such as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) offer a baseline to prevent deficiency, optimal animal health and performance rely on higher, functional intake levels commonly provided by breeding companies (Tables 6–8). Future nutritional models will need to integrate outcome-based metrics and dynamic environmental factors to more precisely tailor vitamin E nutrition to the demands of modern animal production systems.

* Increased to 3 IU/kg BW for pre-fresh cows (2–3 weeks before parturition).

Table 8. Vitamin E dietary recommendations for monogastric species

Conclusions and suggestions for way forward

The nutritional power of α-tocopherol in animal nutrition is firmly rooted in its superior bioavailability and biopotency compared to other vitamin E vitamers. Its preferential retention and utilization in the liver ensure enhanced antioxidant protection, immune modulation, and overall health benefits across animal species.

However, the complexity of α-tocopherol metabolism – shaped by species differences, dietary composition, physiological status, and environmental factors – necessitates more nuanced and evidence-based approaches to optimize its nutritional impact. Recent research highlights that, beyond its classical antioxidant role, α-tocopherol also regulates gene expression and cellular signaling pathways, contributing to immune function, stress resilience, and product quality. These expanded roles encourage a shift from simple supplementation toward integrated, outcome-based nutritional strategies.

To advance the field, future efforts should prioritize:

• Improving delivery methods and feed formulations to enhance bioavailability and tissue retention, especially under commercial production conditions;

• Developing and validating functional biomarkers that better reflect true α-tocopherol status and efficacy, rather than relying solely on plasma α-tocopherol;

• Tailoring supplementation to specific species, life stages, physiological states, and stress conditions to maximize biopotency and minimize nutrient loss;

• Exploring synergistic effects with other micronutrients and antioxidants to further elevate functional benefits; and

• Deepening investigation into non-antioxidant roles and mechanisms, including gene regulation and immune modulation, to inform innovative applications for animal health, welfare, and production efficiency.

It is also important to recognize current limitations, such as the lack of universal biomarkers, incomplete understanding of interspecies variability, and the need for more standardized, comparative studies across animal species and production systems. Ultimately, unlocking the full potential of α-tocopherol demands multidisciplinary research that connects its bioavailability, biopotency, and emerging physiological roles.

A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach – integrating biochemistry, nutrition, physiology, and production science – will enable the development of more effective, species-specific strategies that harness α-tocopherol’s full potential to sustainably improve animal performance, health, and product quality.

Data Availability Statement

This review is based on previously published studies, which are cited throughout the manuscript. No new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Author Contributions

Yauheni Shastak: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – Original draft. Wolf Pelletier: Formal analysis, Writing – Original draft. Ute Obermueller-Jevic: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – Review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors of this work are affiliated with BASF, a manufacturer of vitamins and carotenoids, including vitamin E. Nevertheless, it is crucial to underscore that the content of this manuscript has been sourced exclusively from scientific peer-reviewed data. Our unwavering commitment lies in upholding transparency and adhering to ethical research principles.

Ethical Standards

This article is a review of previously published literature. No new studies involving human or animal subjects were conducted by the authors.