Introduction

Person-centered care (PCC) that honors individual preferences can enhance the health and well-being of nursing home (NH) residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). Preference congruent care, a cornerstone of PCC increases psycho-social well-being and reduce negative behavioral symptoms associated with ADRD [1]. However, honoring everyday preferences, such as going outside independently, are often seen as “risky” by NH staff and subsequently restricted. When residents’ preferences are not honored, particularly those living with ADRD, there are often unintended consequences, including preventable negative emotions such as frustration, sadness, and anger. This emotional distress can manifest as behavioral symptoms, including agitation, withdrawal, or aggression [Reference Duan, Shippee and Ng2]. In one study, staff noted that restricting residents from engaging in preferred activities – like going outside or socializing – led to increased depression, anxiety, and isolation [Reference McClean, Akter and Kowalchik3]. There is an urgent need for evidence-based strategies to help NH staff balance these perceived health and safety risks with the residents’ right to have their important preferences honored (e.g., preference congruence).

Preference-based dementia care requires attention to multiple factors that impact quality care delivery in NHs, including staff attitudes and behaviors. The unique challenges faced by rural, under-resourced NHs, warrant focused attention to support safe and effective preference congruence. ADRD individuals living in rural communities spend more time in NHs than their urban counterparts and are less likely to report care preferences [Reference Duan, Shippee and Ng2,Reference Rahman, White, Thomas and Jutkowitz4]. Highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, there are multiple factors that hinder preference-based dementia care in rural communities, including difficulties in recruiting and retaining direct-care NH staff, minimal staff training around dementia care, and greater issues in staff and resident safety [Reference Henning-Smith, Cross and Rahman5]. These barriers align with common factors associated with omissions of care in NHs (i.e. situations where clinical or non-clinical care is not provided for residents, resulting in preventable adverse outcomes) including low staffing levels and high turnover rates, gaps in knowledge and training of staff, and inadequate use of documentation systems [Reference Mangrum, Stewart and Gifford6]. In addition to these challenges, NH staff (i.e., senior leaders, nurses, nursing assistants, allied health professionals, and non-clinical staff) cite several systemic barriers to honoring a resident’s preference [Reference Behrens, Van Haitsma, Brush, Boltz, Volpe and Kolanowski7–Reference Bangerter, Heid, Abbott and Van Haitsma13].

The continuous close contact of direct-care NH staff offers frequent opportunities to determine and act upon residents’ preferences [Reference Gilster, Boltz and Dalessandro14]. Nursing staff, both licensed and unlicensed, comprise the largest portion of NH direct-care staff [15]. Unfortunately, this direct-care workforce also cites risks to residents’ health and safety as a major barrier to honoring residents’ preferences [Reference McClean, Akter and Kowalchik3,Reference Behrens, Boltz and Kolanowski8,Reference Bangerter, Abbott, Heid, Klumpp and Van Haitsma16]. Honoring ADRD resident preferences while mitigating risk requires clinical and risk assessments and engagement shared decision-making around risk-taking [Reference Behrens, Van Haitsma, Brush, Boltz, Volpe and Kolanowski7,Reference Behrens, Madrigal and Dellefield9,Reference Miller, Whitlatch and Lyons17].

Risk management in nursing homes

Conceptually, risk is culturally bound and includes the potential for harm or loss on the part of an individual themselves or others in their surroundings, cognitive recognition of the potential for harm or loss, and a decision-making process based on weighing the potentialities [Reference Shattell18]. An actual harm or loss does not need to occur for risk to be present in a situation, and no situations are risk-free [Reference Clarke19]. Potential risks for older adults living in NHs can be categorized as physical harms or injury (e.g., death, loss of physical independence); emotional harms or injury (e.g., loss of identity, loss of autonomy, loss of confidence); social harms (e.g., loss of friendships); and financial harms (e.g., loss of income) [Reference Clarke19–21]. Risk engagement is thought to mediate quality of life in older adults living in NHs through the optimal balance of risk-taking and risk-avoiding behaviors [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Kolanowski8]. Risk engagement involves negotiation among the older adult, care providers, and organizations to enact protective processes to negate consequences of extreme risk-taking or risk-avoiding behaviors (i.e. safeguards) and take action to compensate for exposure to risks that may otherwise lead to harm (risk repair) [Reference Clarke19]. Additionally, perceptions of risk in older adults are thought to be amplified and diminished based on interactions with care providers and organizations [Reference Clarke19].

A confluence of factors influences direct-care nurses’ perceptions of residents’ risk engagement. Intrinsic factors include fear of malpractice, manager disapproval and disciplinary actions, a value to err on the side of safety first and only engage in prudent risk-taking, and a perceived lack of professional autonomy in clinical decision-making [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Kolanowski8]. External factors include training requirements and practice expectations, challenges posed by the residents’ health condition and cognitive status, disagreements with family members about residents’ preferences, and the punitive nature of the legal and regulatory culture [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Kolanowski8]. This evidence suggests that NH staff attitudes and behaviors around engaging in risk situations impede the uptake of preference-based, PCC, theoretically perpetuating a poor quality of life for people living with ADRD in NHs.

There is an urgent need for evidence-based risk mitigation strategies that balance NH residents’ preferences with safety and quality of life needs [22]. Risk management is a key element of practice when delivering person-centered nursing care to older adults living with dementia [Reference Sillner, Madrigal and Behrens23,Reference Clarke and Mantle24]. Limited practical resources exist to help NH staff engage in risk assessment and management efforts that facilitate resident preferences [Reference Clarke, Keady, Wilkinson and Gibb20,Reference Calkins and Brush25]. A literature search yielded one care planning process that supports preference-based dementia care while negotiating residents’ risks. The Honoring Preferences When the Choice Involves Risk: A Process for Shared Decision Making and Care Planning has been pilot tested in two descriptive observational studies and found to be useful [Reference Behrens, Van Haitsma, Brush, Boltz, Volpe and Kolanowski7,Reference Calkins and Brush25]. This strategy involves a four-step process: (1) identify and clarify the resident’s choice; (2) discuss the choice and options with the residents and family; (3) determine how to honor the choice; and (4) monitor and revise the plan. This single strategy has not been tested for efficacy or effectiveness in clinical trials and does not include procedures for risk assessment and management for living well with dementia, such as determining the impact of supporting risk-taking on quality of life [Reference Clarke19,Reference Clarke and Mantle24]. Person-centered dementia care necessitates that NH staff have evidence-based risk mitigation interventions that will help tailor care to residents’ preferences and support risk assessment, planning and decision-making.

The aim of this paper is to describe the rigorous development of a multilevel intervention called DIGNITY, which is designed to support shared decision-making with ADRD residents in rural NHs, thus promoting resident psycho-social well-being and quality of life. DIGNITY includes three components: (1) in-person training introducing concepts of person-centered risk management to balance residents autonomy and safety in the NH context, (2) protocol manual describing elements of the risk management strategy, and (3) coaching via ECHO – an interactive web-based telemonitoring.

Material and methods

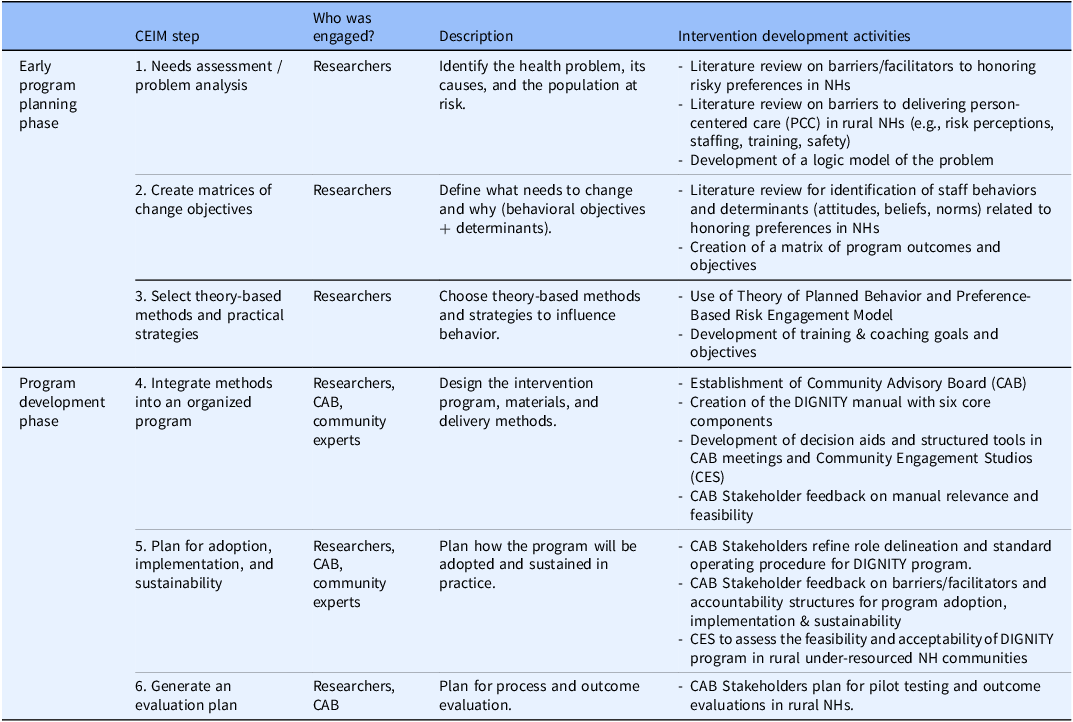

The objective of this study was to develop and refine the Decision-making In aGing and demeNtIa for autonomy (DIGNITY) program for future behavioral intervention testing. The goal of DIGNITY program is to optimize preference congruence and safety related to staff perceived health and safety risks within the complex dementia care environment of the NH. The objective is to develop a multi-component intervention that supports preference congruence. This work was guided by the Community-Engaged Intervention Mapping (CEIM) Model [Reference Santacroce and Kneipp29]. The CEIM model combines the six traditional steps of intervention mapping (IM) with principles of community engagement to involve stakeholders in the decision-making and research processes related to carrying out IM processes [Reference Santacroce and Kneipp29]. See Table 1 for a description of how the CEIM model guided each phase of the DIGNITY program development.

Table 1. Community Engagement Intervention Mapping (CEIM) model guiding intervention development activities

Community Engagement Intervention Mapping (CEIM) Model Guiding Intervention Development Activities. CAB = Community Advisory Board; CES = Community Engagement Studio; DIGNITY = Decision-making in aging and dementia for autonomy; NH = Nursing Homes; PCC = Person-Centered Care.

This study received institutional review board approval from Penn State University with an exemption status before proceeding with any study activities. This study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT05618678].

Early program planning phase

Three authors (LB, MB, KSV) completed the IM early planning phase. This included a gerontologic nurse, a geriatric nurse practitioner, and a clinical geriatric psychologist – all behavioral scientists engaged in the NH setting. Consistent with IM techniques [Reference Santacroce and Kneipp29–Reference Kok, Peters and Ruiter31], three steps were accomplished in the early planning phase of the DIGNITY intervention. First, a logic model of the problem to be addressed was constructed (Supplementary Material). Next, we reviewed previous research on how staff honor risky preferences of NH residents living with ADRD to identify which staff behaviors need to be changed and potential determinants of those behaviors [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Kolanowski8,Reference Behrens, Boltz and Sciegaj32]. This resulted in a matrix of program outcomes and objectives (step 2, Supplementary Material).

In step 3, a deliverable theory-based intervention was designed to change identified staff attitudes and behaviors. The Theory of Planned Behavior purports that the likeliness of an individual (intention) to perform a given behavior (risk-taking) is determined by their attitudes toward the behavior (behavioral beliefs/risk perceptions), the perceived social pressure to perform the behavior (normative beliefs/culture of safety), and the degree of perceived control over the behavior (control beliefs/practice autonomy) [Reference Ajzen33,Reference Steinmetz, Knappstein, Ajzen, Schmidt and Kabst34]. The use of this theory in combination with the Preference-Based Risk Engagement Model [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Sciegaj32] allows us to target NH staff attitudes and behaviors around assessing and judging whether to engage in risk situations to support resident preferences (e.g. to go outside) despite cognitive decline due to dementia. A review of the literature identified behavioral, normative, and control beliefs associated with NH staff intentions to honor residents’ preferences, which was used to construct a set of training goals and objectives (Supplementary Material).

Program development phase

Also consistent with CEIM techniques [Reference Santacroce and Kneipp29–Reference Kok, Peters and Ruiter31], three more steps were accomplished in the program development phase of the DIGNITY intervention. First (step 4), we designed intervention programs, materials and delivery methods in an organized program. From this, a DIGNITY program manual was drafted based on the best available evidence and included five key sections: (1) program overview, (2) key terms, (3) six program components, (4) decision aid tools, and (5) evidence supporting the approach. Key elements of the DIGNITY program and its delivery have been tested in prior studies as a decision aid [Reference Clarke, Keady, Wilkinson and Gibb20], care planning process [Reference Behrens, Van Haitsma, Brush, Boltz, Volpe and Kolanowski7,Reference Calkins and Brush25], and staff education/coaching [Reference Trautner, Grigoryan and Petersen35]. Next (steps 5 and 6), we employed two community engagement approaches to plan how the DIGNITY program will be adopted and sustained in typically under-resourced NH communities and to develop a meaningful evaluation plan for program processes and outcomes.

Community advisory board

A community advisory board (CAB) of NH stakeholders was established using purposive sampling. The goal was to recruit at least two stakeholders from each group (nursing home administrator, academic/clinical expert in nursing home care/risk management, nursing home regulator, ombudsman, or surveyors, nursing home staff members, nursing home resident, or family member/legally authorized representative of a nursing home resident). Stakeholders were eligible to participate if they were: (1) 18 years or older, (2) able to read, write, and speak English, (3) Self-identified as a NH stakeholder group member, and (4) able to attend virtual group meetings.

Data collection

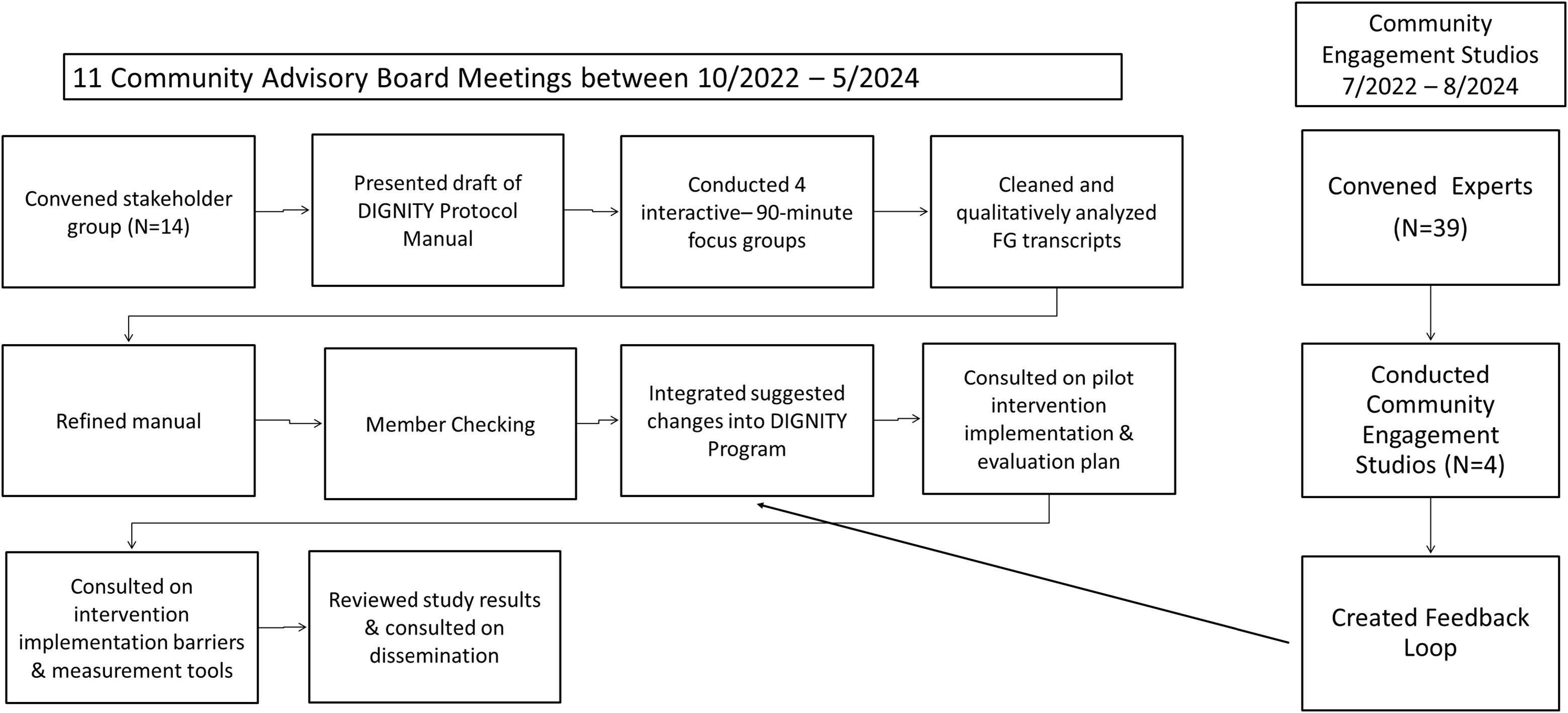

Semi-structured sequential focus group techniques collected opinions of stakeholders around the development, refinement, implementation, and evaluation of the DIGNITY program for rural NH environments [Reference Krueger and Casey36]. Eleven CAB meetings took place between October 2022 and May 2024, the first four meetings were conducted as focus group sessions, the remaining sessions informed implementation and evaluation of a pilot study to test the intervention (Figure 1). All stakeholder meetings were led by experienced moderators (LB, JK) and took place virtually or in-person based on stakeholder needs. Stakeholders were asked to complete a brief demographic survey and review the DIGNITY program manual. Focus groups used semi-structured interview guides that lasted 90 minutes each, and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1. Depiction of Program Development Phase process integrating feedback from both the community advisory board and community engagement studio sessions into the finalized DIGNITY (Decision-making in aging and dementia for autonomy) program.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics summarize characteristics of stakeholders. Qualitative content analysis was completed by two authors (KK, LB) [Reference Hsieh and Shannon37]. Analysis was completed question by question; themes were constructed within and across questions via consensus. Results were confirmed with a group of stakeholders in a member checking session.

Community engagement studios

A Community Engagement Studio (CES) is a structured, one-time consultation session designed to elicit project-specific feedback from community stakeholders – such as patients, caregivers, or frontline staff – on research design, implementation, and dissemination [Reference Joosten, Isreal and Williams38]. CES sessions are facilitated by a neutral moderator, and focus on improving the relevance, feasibility, and cultural sensitivity of a specific research project [Reference Joosten, Isreal and Williams38]. CES sessions differ from focus groups in that their purpose is to improve specific research projects through stakeholder feedback rather than exploring general attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. The goal of our CES sessions was to capture feedback to improve the feasibility and acceptability of implementing the DIGNITY program in rural NH communities.

There were four CES sessions: two sessions were held with self-identified NH leaders, staff, regulators, resident advocates at annual training meetings of the Center for Innovation Pioneer Network and the Association of Health Facility Survey Agencies (AHFSA) and two with rural NH community staff, residents living with dementia, and family as members of the study’s priority population. To identify participants for CE studios, we asked organizational liaisons to distribute a flyer with information about the CE studio’s purpose, location, format, and compensation via email and posting on websites. The CE studios were reviewed by the lead author’s IRB and determined to be non-human subject research; thus, consent was not required. Potential participants indicated their willingness to participate by attending the meeting in person and participating. Except for the AHFSA group, due to organizational policies, all participant attendees received a free lunch and were offered a $25.00 gift card to compensate them for their time.

Data collection

All CES sessions were held in person at locations within the community. CESs followed institutional guidelines for conduct and lasted an average of 90 minutes each. Experienced neutral moderators facilitated CE studios (LB, KK, SR) and followed a structured discussion guide. Each DIGNITY program CES session began with a welcoming and ice breaker exercise, followed by an introduction to the DIGNITY program, a card sort activity to center the context of the DIGNITY intervention, and a detailed review and conversation of relevant DIGNITY program manual procedures and tools. Participants provided initial reactions and had the opportunity to ask clarifying questions. Written field notes recorded participant responses and were checked for accuracy by session moderators within 72 hours of the session.

Data analysis

After each session, audio recordings from CES were transcribed verbatim, read by at least two investigators (LB, KK, JK, SR), and compared against written field notes to ensure all participant ideas were captured. A standardized feedback loop with categories of engagement, community expert participant input, and suggested research team actions were created and shared with the investigator team.

Results

A total of 53 stakeholders participated in the development and refinement of the DIGNITY program providing structured feedback on intervention design, materials, and delivery methods from October 2022 and August 2024 (Figure 1). Reported here are the results of eight of these sessions conducted simultaneously with key stakeholders in a CAB and CESs that were analyzed separated and then merged to inform the tailoring of DIGNITY to the unique needs of rural and other under-resourced NH communities.

Community advisory board focus groups

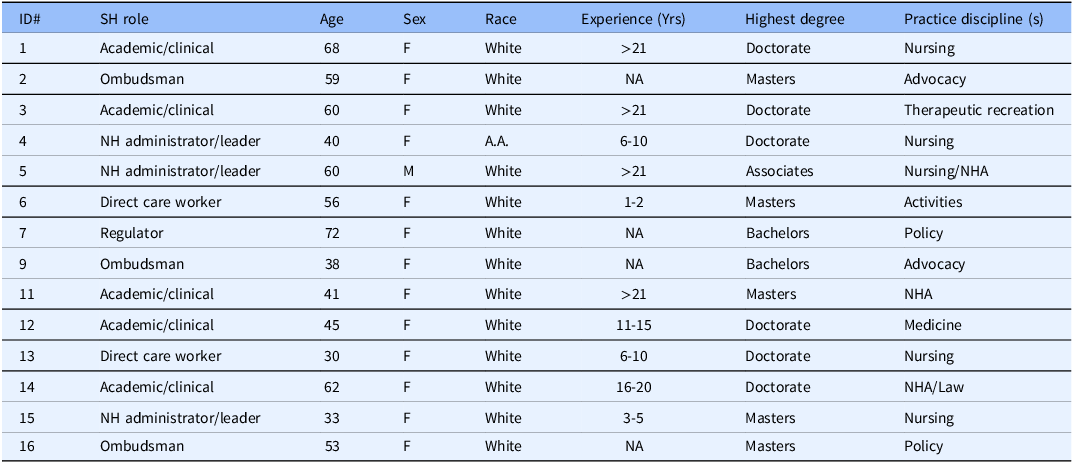

In total, 14 stakeholders took part in four sequential focus group sessions (Table 2). Qualitative analysis of transcript data indicated that overall, stakeholders found the DIGNITY program relevant and feasible to assist rural NH staff to honor residents’ risky preferences for care and activities in the NH environment. Stakeholders identified six thematic areas for modification to the DIGNITY program: (1) DIGNITY manual formatting, (2) communication, (3) expanding staff roles, (4) addressing residents’ decision-making capacity, (5) potential barriers to implementation, and (6) potential facilitators to implementation.

Table 2. Community advisory board participant demographics

Community Advisory Board Stakeholder Demographics Table. A.A. = African American; F = Female; ID#=Identification Number; NA = Not Applicable; NH = Nursing Home; M = Male; NHA = Nursing Home Administrator; SH = Stakeholder; Yrs = Years.

DIGNITY manual formatting

Throughout the focus groups, there were several formatting changes requested by stakeholders based on their program manual review. Most stakeholders agreed that the DIGNITY program manual was easy to read and reported an average reading time of 66 minutes. One ombudsman stakeholder described their experience:

I will say that when you first open it, it’s a large document. It was a little scary at first, but I agree the font size [was good], and it was a really nice, easy read. The Glossary terms in the front were really good to kind of help break down what all of those terms mean, and make it just a nice, leisurely read. (SH#2_009)

Fewer stakeholders agreed that the manual included the appropriate amount of material, indicating it was too long and too much for direct-care staff to read through all at once. Stakeholders suggested changes to the manual, including shortening it, improving the color and organization, and providing alternative learning options (e.g. online modules, case studies, podcasts, training videos, and audiobooks).

Communications

Throughout the focus groups, many stakeholders expressed concerns about the lack of communication that currently exists in the culture of NHs. One NH leader stakeholder described the importance of communicating across interdisciplinary teams to keep the residents safe during staffing shortages. Stakeholders viewed documentation elements of the DIGNITY program as a key strategy to support care team communication by allowing providers to familiarize themselves with the residents’ preferences, capacity, and abilities to remain independent. Stakeholders suggested that direct-care workers should be involved in care plan communication processes and encouraged conversation documentation around risk scenarios to protect themselves from legal risks.

Expanding staff roles

Throughout focus groups, stakeholders described the need to clearly define and delineate staff roles within the DIGNITY program manual. One NH Staff Member stated:

I’m on the ground level with the patients -- and so I’m a hundred percent on board. I think it’s a fabulous program. I’m just wondering how this information is going to get into the hands of the people like me -- who are at the ground level, working with the residents. (SH#2_006)

With another NH leader stakeholder responding to that comment with:

I spent some time yesterday thinking about that exact thing because all the steps to the [DIGNITY] protocol are important. However, I spent some time thinking [about] who could do each step within the protocol. I do think different steps could be done by different people located within the long-term care facility. (SH#2_015)

Stakeholders recommended making changes to modify four program components (1,2,3,6) and adding a component for role delineation and organizational standard operating procedure development. Stakeholders wanted descriptions of the following roles within each program module component: leadership, direct-care workers, regulators, ombudsman, legal team, board of directors, surveyors, and the residents and families. Stakeholders made further suggestions on who may be involved within each activity suggested within the DIGNITY program components.

Addressing residents’ decision-making capacity

Stakeholders described the DIGNITY program as an innovative way to manage residents’ needs to be autonomous and their right to self-determination. There were clear sentiments made by stakeholders to support the presumption that a resident has decision-making capacity. One Ombudsman described their role in supporting residents in decision-making around everyday care activities:

…we presume, and we uphold the resident’s right to make their own decisions, unless a judge has determined that they lack the capacity to do so on their own. And even where that determination has been made, there are all kinds of other levels of decision-making that we feel very strongly they should retain. (SH3_016)

Reflecting on the use of the DIGNITY program, collectively, stakeholders strongly advocated that the DIGNITY program should center the role of the residents as their own decision-maker and further clarify who can make decisions on behalf of residents and in what circumstances.

Potential barriers to program implementation

Throughout focus group meetings, stakeholders explained that the culture of care and organizational accountability structures will impact the uptake of the DIGNITY program. Collectively, stakeholders suggested that communities that do not ascribe to PCC have high staff turnover, less trained staff, or staff with low morale may have difficulty consistently implementing elements of the DIGNITY protocol. When asked about something that would not be easy to implement in the protocol, one Ombudsman stated:

My concern goes back to the diversity of answers that this group provided [to role delineation]. My experience is where no one feels that they are primarily responsible for something, it gets very easy to assume that someone else is responsible for it. That could lead to erosion of implementation in a very short period of time. (SH4_016)

When asked in what ways we could help people feel more accountable, an ombudsperson supported the need for clear accountability needing to be added to the program manual:

… but when I look at the six point model, the core components, communicate and consult, there needs to be a core component zero. The administrator appoints responsible person or a team lead for each component. The model needs specific accountability for each component. (SH4_002)

Stakeholders gave recommendations to modify the language throughout the protocol to empower staff to operate at their scope of practicing and training, and to closely track who delivers elements of the DIGNITY protocol and why in the future pilot study.

Potential facilitators to program implementation

Stakeholders discussed that some parts of the DIGNITY program (components 1,5,6) are easier to implement, especially when using the manual (e.g. routine preference assessments). One clinical expert commented:

Part of me thinks that the easiest thing would be assessing and tracking preferences…It’s sort of like on the MDS, (a resident) wants to go to bed this [time], she wants to read that. And maybe if there’s nothing other than beginning to help people take this more seriously, the manual will have served its purpose. (SH4_001)

Generally, stakeholders perceived the manual itself to be useful as a tool to advocate and raise awareness of the need to support residents in everyday decision-making.

Stakeholders emphasized staff training as a key facilitator to program implementation. One NH administrator with a nursing background commented:

I feel like the training component is really critical…….I think even just an awareness level, because until you see it, you may not see it, what’s really happening in a lot of these areas The well-intentioned staff think that they’re being protective, when in fact they’re really taking away autonomy from folks and you don’t see that until you can internalize it. So, I think that training component and that awareness is huge. (SH#4_005)

Stakeholders also suggested building structured incentives for the staff to complete the DIGNITY program training. One NH staff member gave an example of how their organization incentivized training with bonuses:

The dementia ones that are nice to know -- if you do X number, … I think it’s six or more a year, then they give you bonuses. I’m not sure what the bonuses are… … At [Organization], this might be something that could be tailored to different levels of the staffing… and then they would be incentivized to take it. (SH4_006)

Other incentives included personalizing training for staff members by highlighting a resident living in the NH to make training more personal and offering in-person training rather than web-based training modes. Finally, stakeholders suggested that implementation would be easier at the organizational level if the DIGNITY program was integrated through the organizational Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement programs.

Community engagement studios

In total, 39 Community Experts participated in four CES sessions between July 2022 and August 2024. The experts, 7 male and 29 females, represented NH: leadership (n = 3), nursing staff (n = 10), social work (n = 1), activities staff (n = 1), residents living with dementia (n = 4), family members (n = 4), surveyors (n = 15), and a federal regulator (n = 1). Just under half of the participants were working/living in a rural NH community (n = 16). Experts provided suggestions for improving the feasibility and acceptability of the DIGNITY intervention implementation and evaluation as summarized in the feedback loop (Supplementary Material). Expert suggestions were discussed among the intervention development team, and via group consensus, changes were made to the DIGNITY intervention program.

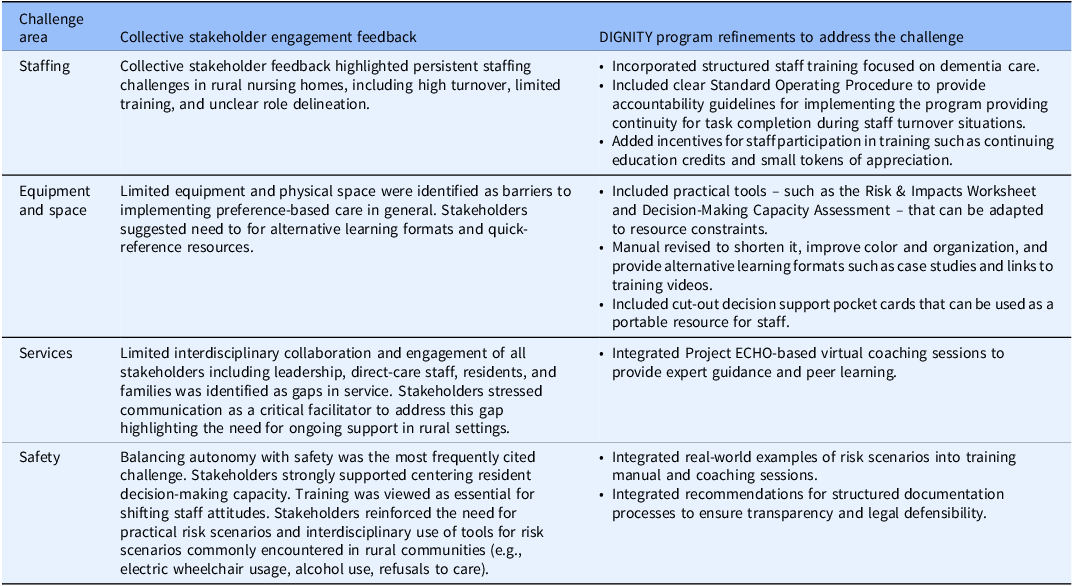

Tailoring the DIGNTY program to key challenges of rural NH providers

Rural NH leaders report challenges in providing care to residents living with dementia in four key areas: staffing, equipment and space, services, and safety [Reference Henning-Smith, Cross and Rahman5]. Shown in Table 3, through integration of iterative feedback from CAB and CES sessions (Figure 1), the DIGNITY program evolved into a multi-component intervention – including a streamlined manual, decision aids, in-person training, and virtual coaching – designed to address staffing limitations, resource constraints, service gaps, and safety concerns in rural NHs.

Table 3. Integrating stakeholder feedback with rural nursing home challenges to providing dementia care for DIGNITY program refinement

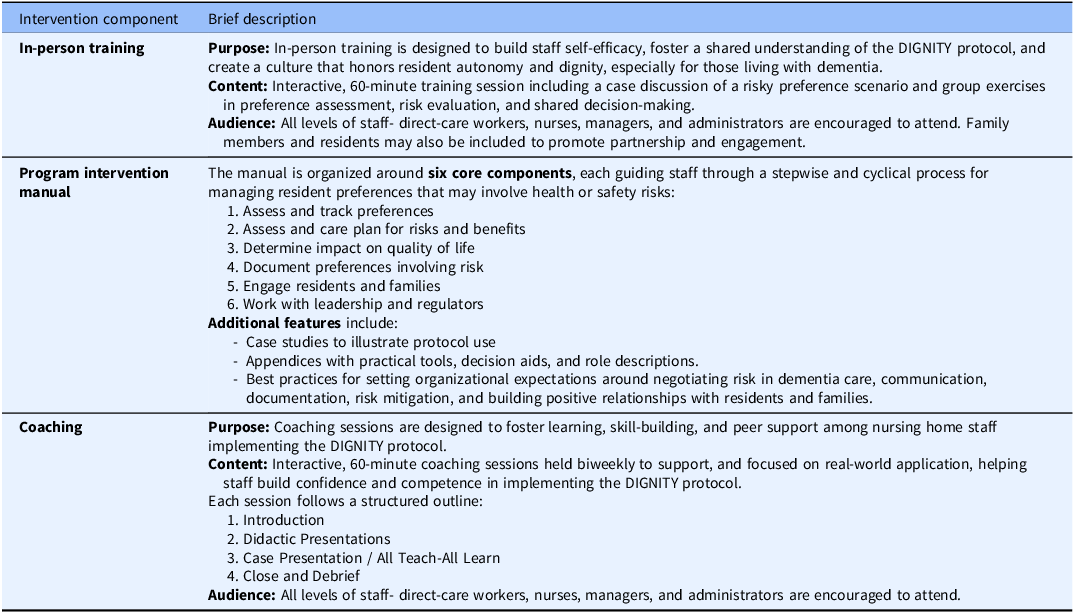

The final DIGNITY intervention program is a multi-component, evidence-based intervention designed to help NH staff safely honor the preferences of residents, including those living with dementia, while managing associated health and safety risks. Described in detail in Table 4, the final DIGNITY intervention includes three pedagogical components: an intervention manual, a 60-minute in-person education session and six one-hour virtual coaching sessions with NH staff.

Table 4. Final DIGNITY program components

Discussion

In this paper, we described the development of an intervention protocol including program materials, and an implementation and evaluation plan that was guided by the CEIM model [Reference Santacroce and Kneipp29]. The final developed DIGNITY intervention is not uniquely rural, however has been tailored to address the reported concerns of rural NH providers caring for older adults living with dementia. For example, stakeholder engagement during the DIGNITY program development phase highlighted persistent staffing challenges in rural NHs, including high turnover, limited training, and unclear role delineation. The program was refined to address these barriers by incorporating structured training, clear accountability, and incentives for staff participation. However, staffing challenges are a concern across rural and urban NHs thus the DIGNITY intervention has potential usefulness in both settings around this care challenge.

Similarly, limited physical space and equipment in rural facilities were acknowledged as barriers to honoring resident preferences in this study. Stakeholder feedback led to the inclusion of practical tools – such as the Risk & Impacts Worksheet and Decision-Making Capacity Assessment – that can be used to adapt decision-making to any NH community with resource constraints. Safety concerns related to dementia care is another challenge that crosses the rural/urban divide [1,Reference Rahman, White, Thomas and Jutkowitz4]. Balancing resident autonomy with safety concerns was a central theme in stakeholder feedback. The DIGNITY program incorporates structured risk assessment and management tools, transparent documentation, and policies to empower staff while protecting resident rights. These tools can be utilized in any NH community with residents who are living with dementia and a staff perceived risk associated with the resident’s everyday care and activity choice.

Likely the most unique to rural NH communities is the persistent limited access to specialized services (e.g., behavioral health clinicians) affecting their ability to provide comprehensive, preference-congruent care for residents with dementia. The DIGNITY program incorporates Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) to address this concern because it extends access of rural providers to experts for collaborative learning and problem-solving and has proven effectiveness in improving clinician knowledge and confidence in managing complex conditions [Reference Bessell, Kim and Chiem42,Reference Melhado, Schneegans and Rochat44]. Two potential benefits of the DIGNITY program for rural NH communities that should be evaluated in future research.

Development of effective interventions intended to change human behaviors target specific mechanisms of action that are grounded in theory or prior empirical work [Reference Birk, Otto, Conelius, Poldrak and Edmondson39]. The DIGNITY intervention program has been designed to change staff attitudes and behaviors around risk engagement as a putative mechanism on the psycho-social well-being and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia care [Reference Behrens, Boltz and Sciegaj32]. However, mechanisms cannot be further tested unless they can be measured [Reference Birk, Otto, Conelius, Poldrak and Edmondson39]. By using the Theory of Planned Behavior, staff intent to honor a residents’ risky preference becomes a potentially viable measure of changes in staff attitudes and behaviors around risk engagement [Reference Steinmetz, Knappstein, Ajzen, Schmidt and Kabst34,Reference Ajzen40,Reference Ajzen41]. Future research should establish whether staff intent to honor residents’ risky preferences is a valid and reliable way to measure the construct of risk engagement [Reference Birk, Otto, Conelius, Poldrak and Edmondson39].

Further translation of this evidence-based intervention into the real-world rural NH practice setting will require the strategic employment of tailored strategies that will address the barriers and leverage the facilitators of risk engagement for NH staff [Reference Powell, Waltz and Chinman26]. Prior work has established that in-person education and virtual coaching sessions support rural staff to engage in risk management processes in hopes of improving knowledge and self-efficacy in the process [Reference Behrens, Madrigal and Dellefield9,Reference Bessell, Kim and Chiem42–Reference Melhado, Schneegans and Rochat44]. Similarly, future research needs to test the feasibility and acceptability of using the DIGNITY intervention protocol including program materials, and the implementation and evaluation plan, among a group of rural NH staff who are caring for residents living with ADRD who are perceived to be making a “risky” choice around a care or activity preference.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop an intervention aimed at promoting NH staff risk engagement in support of PCC delivery. The first strength of this study is the theory- and evidence-based frameworks used to guide the development of this intervention. Secondly, successful translation of scientific discoveries into improvements in individual and population health requires the involvement of community representatives in all research stages [Reference Joosten, Isreal and Williams38]. We successfully recruited NH stakeholders to participate in research which is difficult due to systemic issues in balancing residents’ and staff’s safety and well-being brought forth during the global COVID-19 pandemic. This project leveraged existing groups of NH community stakeholders to obtain meaningful input on the DIGNITY trial procedures and build valuable relationships with key community stakeholders for future testing of the intervention. Thirdly, developing this intervention to suit rural, resource-poor NH communities promotes success in future feasibility and acceptability testing of the intervention. Considering these strengths and despite efforts to foster collaboration and equal voices in the development of this program, it is possible that we have not meaningfully integrated input of stakeholders in the DIGNITY program resulting in a limitation of selection bias.

Conclusion

Limited evidence-based interventions exist to support NH staff in the safe delivery of preference-based dementia care. To achieve this goal, we have constructed an evidence-based, theoretically informed, shared decision-making intervention for use by NH staff in risk management efforts that are supportive of resident’s preferences. This behavioral intervention is intended to change staff attitudes and behaviors around risk engagement as a putative mechanism on the psycho-social well-being and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia care. Future work should investigate the acceptability and feasibility of DIGNITY on changing staff attitudes and behaviors around risk engagement.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2025.10235.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the nursing home residents, family members, staff, administrators, regulators, ombudsman, and other generous stakeholders who generously shared their time, experiences, and insights through the development of the DIGNITY intervention. They have been instrumental in shaping this program. We are grateful for your commitment to advancing person-centered dementia care and supporting resident autonomy.

Author contributions

Liza L. Behrens: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Kimberly S. Van Haitsma: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Susan L. Ryan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing; Kalei H. Crimi: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing; Marie L. Boltz: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing; Jennifer L. Kraschnewski: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Penn State CTSI KL2 Mentored Career Award (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, KL2TR002015) and the Ross and Carol Nese College of Nursing.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare related to financial, professional, contractual or personal relationships or situations.