Introduction

The year 2024 was the first full year in office of the three-party coalition government led by Prime Minister Christopher Luxon, comprising the National Party, ACT and New Zealand First (NZF). As the coalition established itself on the government benches, it began the new year as it had finished the previous one, with a focus on unwinding or outright cancelling a range of policy initiatives and institutional reforms undertaken by the previous Labour government. Cuts and reversals were made notably in areas such as Māori affairs, the environment and climate change and water governance. The government's economic agenda delivered on key election promises, including tax cuts for the ‘squeezed middle’ and extensive cuts to the public sector. The latter had significant knock-on effects on morale in the public service as well as on the economy of the capital city, Wellington. By the end of 2024, the economy was in a sluggish state and cost of living pressures remained high.

Throughout the year, questions began to emerge about Prime Minister Luxon's ability to manage coalition dynamics and to strike a coherent and effective direction for his government organised around National's policy agenda. It became increasingly apparent that the ‘junior’ coalition partners, ACT and NZF, were exercising outsized influence around the Cabinet table. Most vividly, the introduction of the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi bill (colloquially known as the Treaty Principles Bill) at the behest of ACT prompted one of the largest protest marches in a generation, highlighting that the government and Māori were on a collision course. Yet, by the end of the year, polling showed that public opinion had changed little since the 2023 election.

Election report

There were no major elections in New Zealand in 2024.

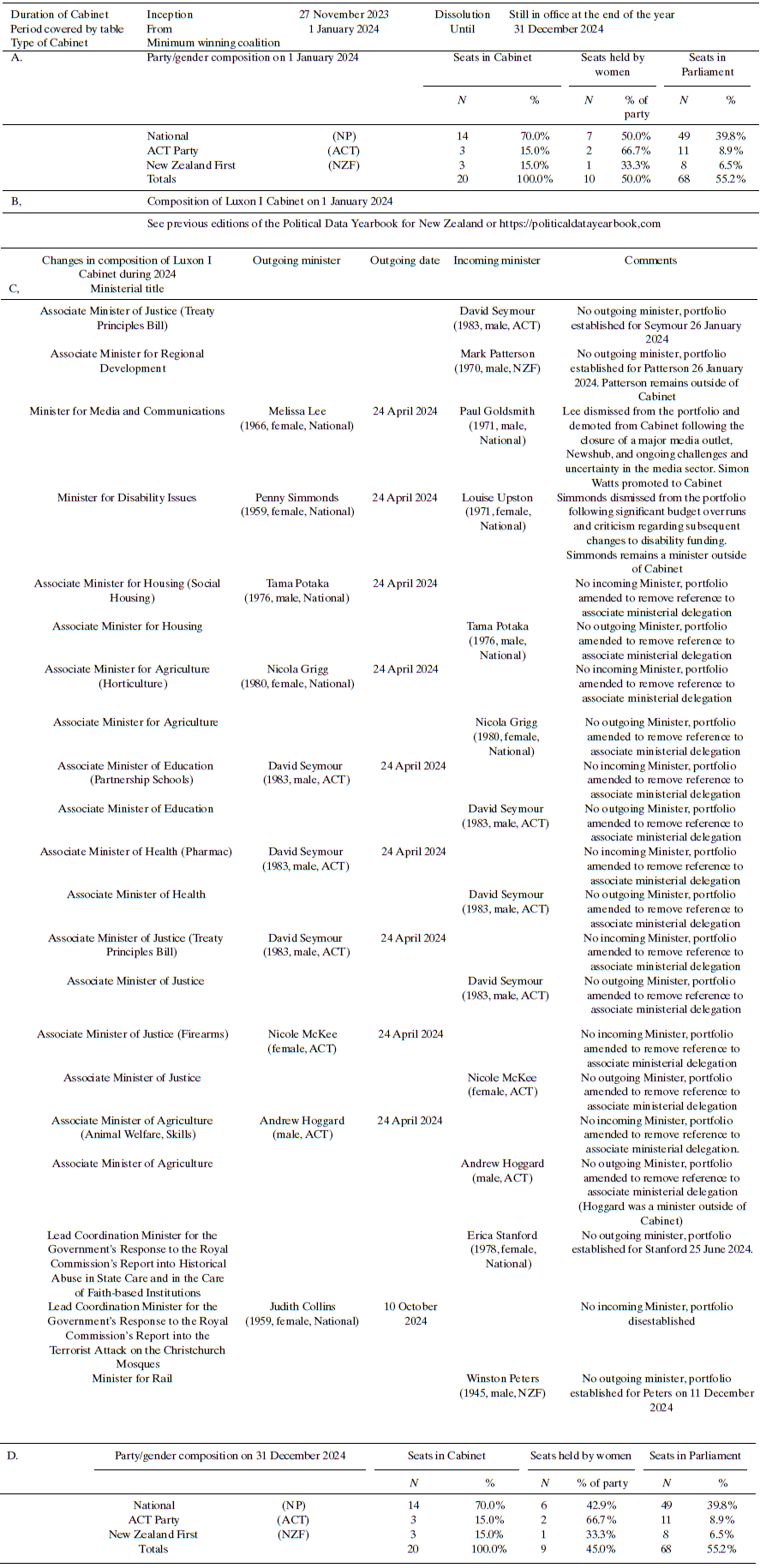

Cabinet report

On 24 April, less than five months after announcing his Ministerial lineup, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon stripped the Media and Communications portfolio from Melissa Lee (National) and Disability Issues portfolio from Penny Simmonds (National). The roles were given to more senior Cabinet colleagues from the National Party: Paul Goldsmith and Louise Upston. With the loss of her main portfolio, Lee was removed from the Cabinet, and Simon Watts (National) was elevated in her place.

Both ministers had suffered acute public criticism, with Lee accused of ‘hiding’ whilst the media sector struggled with ongoing financial uncertainty, including widespread redundancies and the closure of a major news network, Newshub (McCulloch Reference McCulloch2024). Calls for Simmonds’ sacking followed budget overruns in the Ministry of Disabled People—Whaikaha and consequential funding restrictions for disability support carers that lacked consultation with the sector (Labour Voices 2024; Rutherford Reference Rutherford2024). Luxon's pro-active Cabinet management early on contrasted with the lengthy scandals that had gradually whittled away senior Ministers in the beleaguered Labour Cabinet of 2023. Discussing the reshuffle, Luxon said he wanted ‘the right people on the right assignment at the right time’ and that, in contrast to the previous government, under his leadership New Zealand should ‘expect this to happen going forward as well’ (Luxon in Radio New Zealand 2024). However, no further Cabinet demotions or reshuffles occurred throughout the year.

On 25 June, Erica Stanford assumed responsibility as the Lead Coordination Minister for the Government's Response to the Royal Commission's Report into Historical Abuse in State Care and in the Care of Faith-based Institutions. The Royal Commission was established in 2018 and heard from almost 3000 survivors of abuse and neglect throughout its seven-year inquiry (Stanford & van Velden Reference Stanford and van Velden2024). As one Government response to a Royal Commission inquiry geared up, another was wound down. On 10 October, Judith Collin's position as the Lead Coordination Minister for the Government's Response to the Royal Commission's Report into the Terrorist Attack on the Christchurch Mosques was disestablished. Of the Royal Commission's 44 recommendations, 36 had been ‘implemented or are being integrated into ongoing work programmes, while the remaining eight will not be progressing’ (Collins Reference Collins2024). The final Cabinet change of the year saw Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters appointed on 11 December as the first Minister for Rail since 1996. Peter's appointment accompanied an announcement regarding the Government's procurement plan to replace the state-owned Interislander ferries that connect the North and South Islands (Willis and Peters Reference Willis and Peters2024), suggesting that advocates of rail-enabled ferries would find an ally in Peters at Cabinet.

Details of Cabinet composition and changes can be found in Table 1.

Parliament report

As Table 2 shows, there were many changes in Parliament during 2024. Following Labour's loss of the Treasury benches at the 2023 General Election, several of its senior and long-serving MPs resigned in 2024. Each was replaced by former MPs from Labour's party list who had failed to win electorates in 2023. The first to resign was Rino Tirikatene on 28 January. Tirikatene had been defeated by Tākuta Ferris of Te Pāti Māori in the Māori electorate of Te Tai Tonga (which Tirikatene had held since 2011) but had entered Parliament from Labour's party list. His resignation allowed Tracey McLellan to enter in his place. Former Labour Party Deputy Leader Kelvin Davis shortly followed in Tirikatene's footsteps, resigning from Parliament on Waitangi Day (6 February). He had been similarly ousted by new Te Pāti Māori MP Mariameno Kapa-Kingi from the Māori electorate of Te Tai Tokerau and was replaced by Shannan Halbert from Labour's list. The last of Labour's old guard to resign in 2024 was former Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Grant Robertson. His resignation on 22 March to take up the Vice-Chancellorship at the University of Otago saw Glen Bennett re-enter Parliament.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of Parliament in New Zealand in 2024

Notes:

1. Golriz Ghahraman (Green) resigned from Parliament on 18 January 2024. Celia Wade-Brown entered Parliament from the Green's party list on 19 January 2024.

2. Rino Tirikatene (Labour) resigned from Parliament on 28 January 2024. Tracey McLellan entered Parliament from Labour's party list on 30 January 2024.

3. Kelvin Davis (Labour) resigned from Parliament on 6 February 2024. Shanan Halbert entered Parliament from Labour's party list on 8 February 2024.

4. Fa'anānā Efeso Collins (Green) passed away on 21 February 2024. Lawrence Xu-Nan entered Parliament from the Green's party list on 6 March 2024.

5. Grant Robertson (Labour) resigned from Parliament on 22 March 2024. Glen Bennett entered Parliament from Labour's party list on 25 March 2024.

6. James Shaw (Green) resigned from Parliament on 5 May 2024. Francisco Hernandez entered Parliament from the Green's party list on 6 May 2024.

7. Darleen Tana resigned from the Green Party 8 July 2024. Tana remained an independent Member of Parliament until she was expelled from Parliament on 22 October 2024. Benjamin Doyle entered Parliament from the Green's party list on 22 October 2024.

The Green Party also experienced significant parliamentary turnover in 2024. Just over a week into the new year, Green MP Golriz Ghahraman stepped aside from her portfolios after shoplifting allegations were made against her. She resigned from Parliament on 18 January and was replaced by former Wellington Mayor, Celia Wade-Brown. News regarding Ghahraman's court appearances and eventual conviction continued to make headlines through the year (Earley Reference Earley2024; Radio New Zealand 2024b).

On 21 February, tragedy struck: just six days after his maiden speech, newly elected Green MP Fa'anānā Efeso Collins collapsed and died during a charity run in Auckland. His death brought Parliament to a halt as members from across the House shared stories and memories of Collins (Moir Reference Moir2024). Lawrence Xu-Nan entered Parliament from the Green's party list on 6 March.

Then, days after Chlöe Swarbrick was elected Green co-leader (see the Political Party Report), Green MP Darleen Tana was accused of knowing about alleged migrant exploitation at her husband's e-bike business. Tana, a new MP, was suspended from the party as it commissioned an independent investigation. This marked the beginning of a protracted struggle between the party and Tana. Whilst the investigation dragged on, former party co-leader James Shaw concluded his staggered exit from politics, resigning from Parliament on 5 May. He was replaced by Francisco Hernandez. In July, Tana met with her former caucus colleagues to discuss the completed report into the allegations against her. After the meeting, she resigned from the party on 8 July. Whilst Tana had initially welcomed the independent investigation (Maher Reference Maher2024), she claimed natural justice issues occurred throughout the investigation. In turn, the party caucus unanimously asked Tana to resign as an MP, claiming her behaviour failed to meet the standard of an MP (Checkpoint 2024).

Tana chose to stay in Parliament as an independent MP. This placed the Greens in an uncomfortable position: use the powers within the Electoral (Integrity) Amendment Act 2018 to expel Tana from Parliament (despite the Green's moral opposition to the bill in 2018, which they had called a ‘dead rat’; Radio New Zealand 2018) or allow her to continue in Parliament (despite their assessment she was unfit to be an MP). Tana took legal action to prevent the party from holding a Special General Meeting (SGM) in September to discuss the use of the ‘waka-jumping’ legislation, which although successful in delaying the meeting ultimately saw the court rule against Tana (New Zealand Herald 2024). At the re-convened SGM, delegates agreed to use the powers of the waka-jumping legislation. Upon receiving notice from the party, the Speaker expelled Tana as an MP on 22 October, ending the ‘Tana saga’ and allowing Benjamin Doyle to enter Parliament as the House's first non-binary MP (Perese Reference Perese2024).

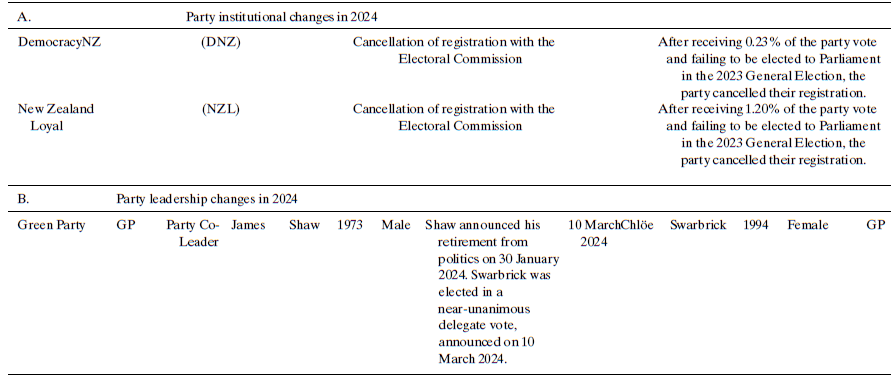

Political party report

James Shaw, a co-leader of the Greens since 2015, announced on 30 January his imminent retirement from politics. Chlöe Swarbrick was subsequently elected to replace him in a near-unanimous party delegate vote, announced on 10 March (Radio New Zealand 2024a).

During 2024, fringe parties DemocracyNZ and New Zealand Loyal cancelled their registration with the Electoral Commission after failing to be elected at the 2023 General Election. This signalled NZF's successful consolidation of the anti-lockdown and vaccine conspiracy fringe vote, represented best by their new MP Tanya Unkovich, a member of the ‘Nuremberg Trials’ Telegram channel (which compared the COVID-19 vaccine to Nazi war crimes) (de Silva Reference De Silva2023).

Changes in political parties are reported in Table 3.

Institutional change report

In January, the Independent Electoral Review, established by Labour in 2022, delivered its final report and recommended numerous reforms to the country's electoral rules (Independent Electoral Review 2024). However, Minister of Justice Paul Goldsmith immediately ruled out many of the recommendations, including lowering the voting age to 16, allowing all prisoners to vote, and fixing the ratio of electorate to list seats in the MMP electoral system (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2024). The Review received little further attention from the government. The government legislated its own reform in July, re-establishing the requirement for local referenda to be held regarding the establishment of Māori constituencies and wards in local government elections (Department of Internal Affairs 2024).

In September, after almost a decade of preparatory work under different governments, the ‘arcane … [but] important’ Parliament bill was introduced (Collins Reference Collins2024a). Once enacted, the Parliament Bill will enhance the legislature's independence by moving decisions about funding for the Office of the Clerk and Parliamentary Services away from the executive (Daalder Reference Daalder2024). It will also give Parliament's security guards greater powers to act on Parliament's grounds, as the parliamentary occupation of 2022 had demonstrated the limitations of their existing powers.

No other major constitutional change was implemented during 2024, although the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill generated significant discussion regarding the constitutional foundations of Aotearoa New Zealand (see the Issues in National Politics).

Issues in national politics

As signalled in the government's 100-day plan, the government began 2024 by continuing its reversals of Labour policy, including repealing legislation to create a smoke-free generation and using urgency to reverse water governance reform. It also began work on its economic agenda. Following their reversal of the Reserve Bank's dual-mandate in late 2023 (focusing its attention solely on low inflation by removing the need to consider employment rate), Minister of Finance Nicola Willis directed heads of all government departments and public agencies to find savings of 6.5 per cent to 7.5 per cent (RNZ 2024c). This started a turbulent period that saw thousands of jobs lost across the public service (RNZ 2025). Most cuts were concentrated in core policy agencies predominantly based in Wellington, and the cuts and ‘culture of restraint’ had a large and highly publicised impact on the capital's economy (Waiwiri-Smith Reference Waiwiri-Smith2024).

The government directed these savings towards tax reform, allocating NZD 15 billion across the next four years to provide tax relief for the ‘squeezed middle’ and restoring full interest deductability for landlords of residential properties at an additional cost of NZD 2.9 billion over four years. Opposition politicians cited this latter tax break regularly throughout the year as evidence that Luxon was solely interested in advantaging ‘the wealthiest New Zealanders’ (Edmonds, cited in 1News 2024), contrasted against funding cuts for disability services and review of the Ka ora, Ka ako free school lunch programme (1News 2024).

Another part of the government's economic agenda was a push to consolidate key trading relationships, including rekindling attempts to negotiate a Free Trade Agreement with India. Indeed, Luxon and Foreign Minister (and NZF leader) Winston Peters had a busy year of travel, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, between them visiting Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, India and more. While not a prominent actor on either Ukraine or Gaza, the government contributed humanitarian support for Gaza and expanded sanctions on Russia. Despite regular pro-Palestine protests, this issue did not generate the same degree of domestic division or extreme clashes between student protesters and government seen elsewhere.

In late November, cross-party agreement was reached and Parliament unanimously passed a private member's bill introduced by Green MP Teanau Tuiono. The Citizenship (Western Samoa) (Restoration) Amendment Act 2024 provided a pathway to New Zealand citizenship for Samoans born as British subjects during New Zealand's administration of Western Samoa (1924–1948), who had been stripped of the right to citizenship in 1982. The 2024 Act was widely welcomed and went some way to rectifying a long-standing source of pain for New Zealand's large Samoan community and a subject that had affected New Zealand's relationship with Samoa (Dreaver Reference Dreaver2024).

As the year went on, the Reserve Bank began reducing the Official Cash Rate for the first time since the pandemic began in March 2020. Inflation continued to decline from its peak in 2022, reaching 2.2 per cent (CPI) by the end of 2024 (Stats NZ 2025), although steep increases in individual items such as local taxes (rates) and insurance costs continued to be widely felt. Despite declining inflation, GDP contracted in consecutive quarters and unemployment increased (Stats NZ 2025a), reaching 5.1 per cent by December, accompanied by the largest annual fall in employment since 2009. The economic downturn, dramatic slowdown in sectors such as construction and hospitality, and challenging labour market conditions saw substantial growth in the number of New Zealanders looking abroad. The year to December 2024 saw a net migration loss of 30,000 people to Australia, traditionally the largest destination for New Zealanders (Stats NZ 2025b). By the end of 2024, it was difficult to deny that the economy and labour market were stalling, and ongoing inflation and cost of living pressures were making life hard for many New Zealanders.

However, the economy was not the most dominant issue in 2024; rather, it was fracturing relations between the government and the Indigenous Māori, the tangata whenua (people of the land) of Aotearoa New Zealand. The tone had been set late in 2023 with a nationwide day of action against the government's proposed policies in relation to Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi. In late January, the first in a series of Hui-ā-motu (nationwide meetings) was hosted by the Māori King, Kīngi Tuheitia, at Tūrangawaewae marae to demonstrate kotahitanga (unity) and respond to government policies. Shortly afterwards, the annual Waitangi Day commemorations were marked by protest and disruptions of government politicians’ speeches. Protest continued throughout the year against policy changes described by some as a ‘systematic legislative attack’ on Māori (Corlett & Tahana Reference Corlett and Tahana2024) and a rolling back of 50 years of progress in Māori-Crown relations (1News 2024a). Such changes included reduced Māori language use by government agencies, a decision to roll back school curriculum reforms that had increased teaching of the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori history, Māori ward poll requirements in local government, and formal disestablishment of Te Aka Whai Ora | the Māori Health Authority.

Procedurally, aspects of government management of policy and parliamentary business drew comment from constitutional experts, who noted increasing use of urgency (and thus avoidance of select committee scrutiny) to advance the government's agenda. Additionally, on several occasions, Ministers appeared to make decisions on issues such as speed limits, tobacco, and alcohol policy that went against advice and scientific evidence provided by officials, raising concerns about industry lobbying. Periodic leaks of information and some high-level resignations reflected an unsettled public sector that had a tense relationship with the coalition.

Questions were also asked about coalition dynamics. While the Cabinet was stable, the Prime Minister appeared to lack authority over his coalition partners (Hickey Reference Hickey2024). More broadly, considerable political capital was spent on a range of disparate policy initiatives that were not high on National's list of priorities but which ACT and NZF had negotiated during coalition formation. This included a $24 million funding boost for a single, controversial mental health provider (Gumboot Friday) that breached government procurement standards, consideration of loosening firearms laws, mandating a second phase of the Royal Commission into the country's COVID-19 response, and establishment of a Ministry of Regulation. The ‘junior’ coalition partners appeared to be exercising disproportionate influence on the policy agenda and in the media, something their leaders were only too happy to claim publicly (Smith Reference Smith2024a).

This was highlighted most clearly with the introduction of the Treaty Principles Bill, which sought to redefine the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi by nationwide referendum. The ‘principles of the Treaty’—including partnership, redress, active protection, and equity—have been developed over decades via court decisions, government decisions, and policy practice, and provide a way of reconciling the Māori text of te Tiriti o Waitangi with the English draft of the Treaty of Waitangi (Corlett Reference Corlett2024). Māori and non-Māori legal scholars alike objected to the bill, arguing it would redefine the Treaty relationship without consultation with iwi and hapū Māori, the Treaty partners. Further, they said the principles proposed by the Bill did not reflect what is written in Te Tiriti; rather, by ‘imposing a contested definition of the three articles, the bill seeks to rewrite the Treaty itself’ (Scoop 2024) and would alter how the Treaty would be used and applied in New Zealand law and political practice (Jones Reference Jones2024).

Despite an already fractured relationship with Māori, the government pressed on with the bill because it was one of ACT's ‘non-negotiables’ during coalition formation. Debate at the first reading on 14 November was heated and made headlines around the world: during her speech Te Pāti Māori MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke tore a copy of the bill in half and protested further with a haka directed at ACT party leader David Seymour (Corlett Reference Corlett2024). MPs from her party and Labour MP Peeni Henare joined her, as did members of the public gallery, resulting in the Speaker suspending Parliament (Perese Reference Perese2024a). Ultimately, the bill passed its first reading and was sent to Parliament's Justice Committee for consideration. Despite opposing progression of the bill past first reading, by promising to support it to committee, National drew the ire of many and one of the largest protest marches in a generation was sparked. By the time the nine-day Hīkoi mō Te Tiriti (March for the Treaty) arrived in Wellington—having marched the length of Aotearoa New Zealand—it had drawn tens of thousands from around the country.

Surprisingly, strong opposition to government policies and wider economic challenges did not translate into significant government decline in the polls (Manhire Reference Manhire2024). Although the Prime Minister was not especially popular, appeared to lack political acumen in his own decision-making, and did not always front difficult coalition issues, neither the main opposition Labour Party nor the Greens managed to propose clear, positive alternative policy positions or achieve cut through in their attacks on the government. By the end of the year, it seemed 2024 had further opened the gap between supporters of the government and its critics.

Acknowledgments

Open access publishing facilitated by Victoria University of Wellington, as part of the Wiley - Victoria University of Wellington agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.