Introduction

Psychosis is a multifactorial syndrome shaped by the interaction of biological, psychological, environmental, and societal factors (Howes & Murray, Reference Howes and Murray2014; Morgan & Gayer-Anderson, Reference Morgan and Gayer-Anderson2016; Read, van Os, Morrison, & Ross, Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; van Os, Kenis, & Rutten, Reference van Os, Kenis and Rutten2010; Vassos et al. Reference Vassos, Pedersen, Murray, Collier and Lewis2012). Among these, exposure to psychological trauma has emerged as a consistent and significant risk factor (Thompson & Broome, Reference Thompson and Broome2020). Evidence from meta-analyses indicates that approximately one-third of psychosis cases may be attributable to childhood adversity (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012). A recent large-scale meta-analysis spanning four decades of research confirmed a strong association between childhood adversity and psychosis, with an overall odds ratio of 2.80 and particularly strong effects for emotional abuse (OR = 3.54), underscoring the clinical importance of early adversity in psychosis risk (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Sommer, Yang, Sikirin, van Os, Bentall and Begemann2025). This association has also been highlighted in subclinical psychosis populations, where emotional abuse has emerged as one of the strongest predictors of psychosis-like experiences (Toutountzidis et al., Reference Toutountzidis, Gale, Irvine, Sharma and Laws2022). Epidemiological studies show high prevalence rates of childhood abuse among individuals with schizophrenia: 26% report childhood sexual abuse, 39% physical abuse, and 34% emotional abuse (Bonoldi et al., Reference Bonoldi, Simeone, Rocchetti, Codjoe, Rossi, Gambi and Fusar-Poli2013). These findings underscore the importance of trauma exposure as a potentially modifiable factor in the etiology of psychosis and raise questions about underlying mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a hypothesized pathway through which trauma may contribute to psychosis. PTSD affects around 16% of trauma-exposed youth (Alisic et al., Reference Alisic, Zalta, van Wesel, Larsen, Hafstad, Hassanpour and Smid2014), and its persistence has been linked to heightened risk of psychotic experiences (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Philips, Greenstone, Davies, Stewart, Ewins and Zammit2023). Longitudinal studies suggest PTSD partially mediates the association between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences in adolescence (14%) and, to a lesser extent, in adulthood (8%) (Strelchuk et al., Reference Strelchuk, Hammerton, Wiles, Croft, Turner, Heron and Zammit2022). These findings highlight the importance of timely interventions targeting trauma-related distress to potentially interrupt the progression to more severe psychopathology.

Several neurobiological and psychological mechanisms have been proposed to explain how trauma confers risk for psychosis. Trauma exposure may lead to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, heightening stress sensitivity (Walker, Mittal, & Tessner, Reference Walker, Mittal and Tessner2008). Intrusions of trauma-related memory content may underlie certain hallucinatory experiences (Gracie et al., Reference Gracie, Freeman, Green, Garety, Kuipers, Hardy and Fowler2007), and early adversity can contribute to the development of negative core beliefs, thereby increasing vulnerability to persecutory delusions (Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O’Sullivan and Sellwood2014). Emotional abuse has been identified as a reliable predictor of psychotic symptoms, potentially through its impact on self-concept (Toutountzidis et al., Reference Toutountzidis, Gale, Irvine, Sharma and Laws2022). Moreover, trauma-related negative cognitions are common among individuals at high risk of psychosis (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, French, Lewis, Roberts, Raja, Neil and Bentall2006), suggesting that addressing these beliefs may be a useful therapeutic target (Ackner, Skeate, Patterson, & Neale, Reference Ackner, Skeate, Patterson and Neale2013; Zarubin, Gupta, & Mittal, Reference Zarubin, Gupta and Mittal2023).

Given these associations, trauma-focused interventions (TFIs) have been increasingly applied in psychosis populations, particularly for comorbid PTSD (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Spain, Furuta, Murrells and Norman2017). For this review, TFIs are defined as treatments that directly encourage a person face the memories, situations, and unhelpful thoughts or beliefs related to a traumatic experience, by using cognitive, emotional, or behavioral techniques to facilitate the processing of the experience (Schnurr, Reference Schnurr2017; Wade et al., Reference Wade, Varker, Kartal, Hetrick, O’Donnell and Forbes2016). Evidence-based TFIs include trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), both of which are recommended in clinical guidelines for PTSD (NICE, 2018). These interventions use exposure to the traumatic memory but differ in their mechanisms: exposure-based treatments, such as prolonged exposure (PE), aim to reduce avoidance and desensitize trauma responses, EMDR targets maladaptive memory networks through bilateral stimulation, while TF-CBT combines exposure with cognitive restructuring (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023).

A meta-analysis by Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall, and Thomas (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018) using pre–post analyses indicated a significant small pre–post treatment effect on positive symptoms (K = 7) and delusions (K = 4), but not for hallucinations (K = 4) or negative symptoms (K = 4). Pre–post treatment and follow-up data suggested that TFIs showed promising effects on reducing positive symptoms of psychosis at post-treatment (g = 0.31); however, these effects were small and not maintained at follow-up (g = 0.18). TFIs had a small effect on delusions at post-treatment (g = 0.37) and follow-up, but this was only significant at follow-up (g = 0.38). Crucially, Brand et al.’s (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018) review found no significant benefit specifically for hallucinations either at the end of treatment (g = 0.14) or at follow-up (g = −0.06). These findings are intriguing, considering much research in this area has proposed a relationship between hallucinations and traumatic events, with some suggesting they may be direct manifestations of trauma-based memories (Steel, Reference Steel2015). Treatment length was found to significantly moderate both positive and negative symptoms at follow-up, suggesting this could be an important point of focus (Brand et al., Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018). However, an up-to-date synthesis of studies is needed as several new studies (including randomized controlled trials, RCTs) have been published since Brand et al.’s (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018) meta-analysis of hallucinations and delusions (in four pre–post studies and two RCTs). Additionally, most of the studies included in Brand et al.’s review were rated at high risk of bias and with low methodological quality. Only people with clinical presentations of psychosis were included, and thus, the question remains whether TFIs could be used to alleviate subclinical symptoms of psychosis and prevent escalation into psychotic disorders.

The most recent systematic review of 17 studies in this area conducted by Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023) found that psychotherapies using exposure such as PE, EMDR, and TF-CBT were more likely to improve at least one symptom of psychosis than trauma-informed interventions (e.g., cognitive restructuring) that did not include exposure. Nevertheless, the review by Reid et al. did not include a meta-analysis, which reduces the precision and certainty of results. Additionally, Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023) included only four controlled studies, and the remaining were case series with small sample sizes, making it hard to generalize results. Like Brand et al. (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018), studies posed a variety of methodological issues – for example, lack of blinding of participants, risk of attrition bias, and unrepresentative samples. As Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023) did not synthesize data using meta-analyses, it was also unclear whether any intervention (e.g., those that involved exposure) had significantly reduced any symptoms of psychosis. Our review focused on examining hallucinations, delusions, and total negative symptoms separately as Brand et al. (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018) found TFIs impacted symptoms differently.

Much of the research in both Brand et al. (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018) and Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023) reviews also focused on treating PTSD, with symptoms of psychosis as a secondary outcome; interventions therefore were often not targeted toward traumatic memories that might be directly relevant to symptoms of psychosis, an important consideration as research has shown relationships between the content of psychosis experiences and traumatic events (see Vila-Badia et al., Reference Vila-Badia, Butjosa, Del Cacho, Serra-Arumí, Esteban-Sanjusto, Ochoa and Usall2021).

The present systematic review and meta-analysis provides an updated quantitative synthesis of the effects of TFIs on psychosis symptoms, examining hallucinations, delusions, and negative symptoms separately. We investigated psychosis symptoms across the continuum, as such experiences are not confined to clinical diagnoses (van Os et al., Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam2009), and examining both clinical and subclinical presentations may inform the development of more effective preventative strategies.

Methods

Search strategy

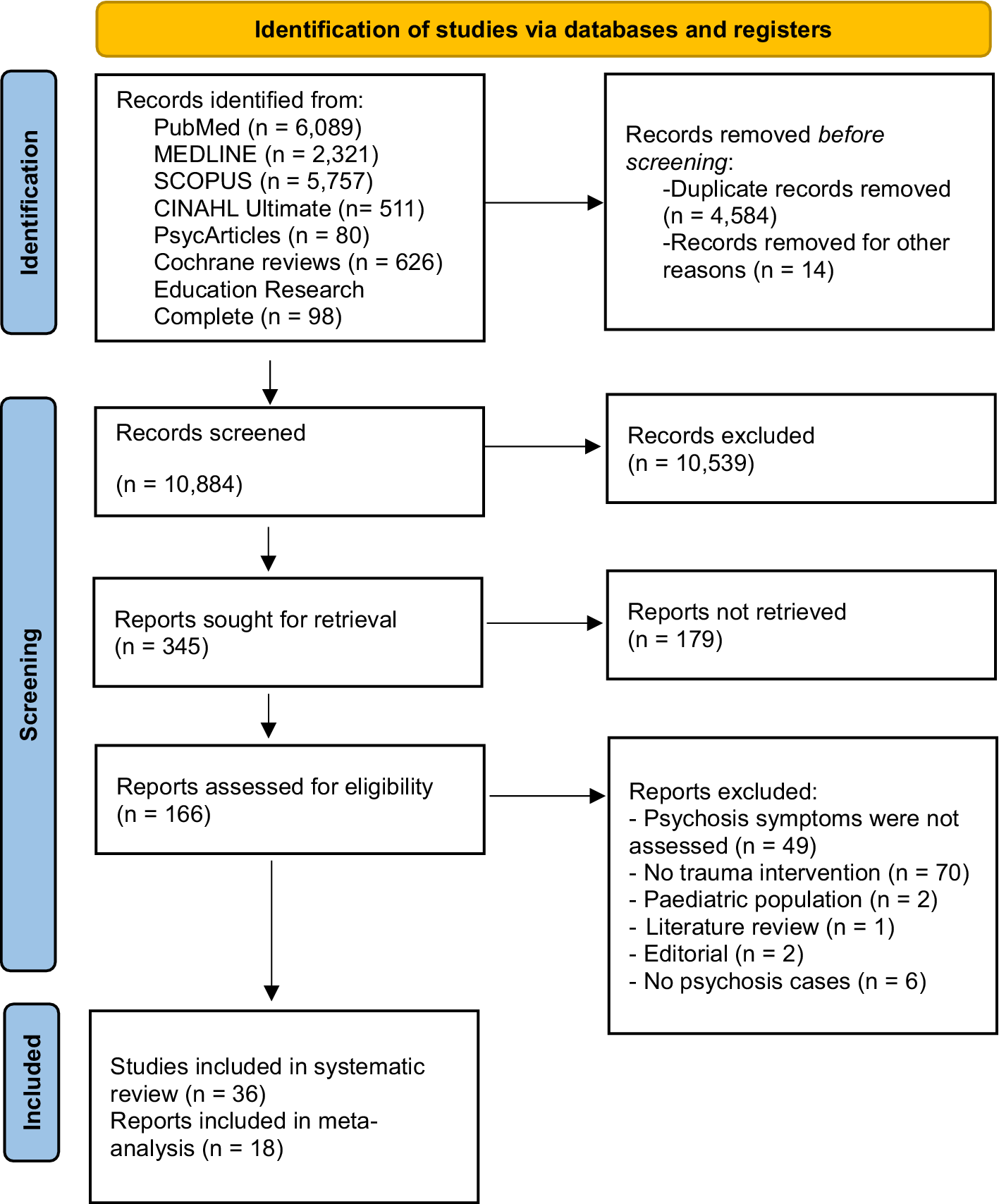

The review was preregistered with PROSPERO (CRD42024508790) and followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see Figure 1 for flowchart and Supplementary 1 for the PRISMA 2020 Checklist (Haddaway & McGuinness, Reference Haddaway and McGuinness2020)).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagram of each stage and details of excluded reports in full review.

Literature searches were conducted on PubMed (n = 6,089), CINAHL Ultimate (n = 511), PsycArticles (n = 80), Cochrane reviews (n = 626), Education Research Complete (n = 98), and MEDLINE (n = 2,321) using the following sets of search terms:

(Psychosis OR psychotic OR schizoty* OR psychosis-like OR psychotic-like OR subclinical psychosis OR schizophrenia OR attenuated psychotic symptoms OR hallucinations OR delusions OR magical ideation OR suspiciousness OR delusional ideation OR odd belie* OR eccentric behavi* OR odd speech OR constricted affect OR unusual perceptual experiences OR ideas of reference OR paranoia ideation) AND (Post-traumatic OR trauma OR stressful events OR traumatic incident) AND (therapy OR psychotherapy OR intervention OR early intervention trauma focused OR CBT OR cognitive therapy OR cognitive processing therapy OR exposure therapy OR EMDR OR eye movement desensitization OR narrative exposure therapy OR brief eclectic psychotherapy OR virtual reality exposure).

A broader search strategy was used for Scopus – as only one article came up compared to 6,089 on PubMed using the original strategy – and revealed 5,757 research articles in English:

(psychosis OR schizoty* OR psychosis-like OR subclinical OR schizophren*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (post-traumatic OR trauma* OR abuse OR maltreatment OR neglect OR victimisation) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (psychotherapy OR emdr OR intervention OR behavioural OR dialogical OR behavioral OR narrative OR exposure OR virtual).

Studies published in these databases since their day of inception to screening were screened for inclusion. Searches were updated in mid-June 2025. Identified articles were uploaded to Covidence (n = 15,482). A total of 4,584 studies were removed as duplicates and 14 for other reasons (e.g., not in English, conference abstracts). We screened 10,884 study titles manually using Covidence and classified 345 articles as potentially relevant. Following title and abstract screening, 166 articles were identified for full-text screening, and finally, after excluding 130 articles (See Supplementary 2 for full list), 36 studies were included in the systematic review. Out of these 36 studies, some were identified as follow-up investigations that utilized the same participant sample. For example, specific studies by van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, Van Minnen and van der Gaag2015, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, De Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2016, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2018), de Bont et al. (Reference de Bont, van den Berg, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van der Gaag and van Minnen2016), and Burger et al. (Reference Burger, Hardy, Verdaasdonk, van der Vleugel, Delespaul, van Zelst and van den Berg2025) all reported on a shared sample. In this case, we further examined de Bont et al. (Reference de Bont, van den Berg, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van der Gaag and van Minnen2016) as this study presented data on hallucinations and delusions for two TFIs. For the meta-analyses, sufficient data were obtained from 18 studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We approached researchers to request the data from studies where outcomes of psychosis symptoms were not available in the published papers. We received additional datasets for papers by Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Rosenberg, Xie, Jankowski, Bolton, Lu and Wolfe2008 and Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Gottlieb, Xie, Lu, Yanos, Rosenberg and McHugo2015.

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the systematic review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) adult participants diagnosed with psychosis or symptoms of psychosis (i.e., clinical cases of a psychotic disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorder or scoring highly for psychosis symptoms; or subclinical cases of those scoring highly on psychometric assessment of schizotypal traits or whose personality traits bare similarity to psychosis symptoms in early intervention and protective services); (b) studies that included TFIs for PTSD or post-traumatic stress symptoms; and (c) studies written in English. Screening and eligibility assessment were performed independently by two reviewers (DT and ER), and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data collection process and data items

The following data were extracted from each study: 1) study design, 2) participant characteristics (mean age and gender composition), 3) intervention and comparison groups, 4) primary outcomes, 5) secondary outcomes, and 6) treatment retention. A summary of all studies and their characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Study characteristics

Note: AHS, Auditory Hallucinations Subscale (of PSYRATS); BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAVQ, Beliefs about Voices Questionnaire; BPD, borderline personality disorder; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CST, coping skills training; DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale; DID, dissociative identity disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EMDR, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; FU, follow-up; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; GPTS, Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IR, imagery rescripting; M, mean; MDD, major depressive disorder; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NR, not reported; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PD-NOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; PE, prolonged exposure; PMR, progressive muscle relaxation; post, post-treatment; pre, pre-treatment; PSYRATS, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales; PSYRATS-AHS, PSYRATS – Auditory Hallucinations Subscale; PSYRATS-D, PSYRATS – Delusions Subscale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial; S, session(s); SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; SD, standard deviation; SIPS, Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes; SZA, schizoaffective disorder; SZ, schizophrenia; TAU, treatment as usual; TF-CBT, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy; TFT, trauma-focused treatment; TI-CBTp, trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis; TSQ, Trauma Screening Questionnaire; WL, waitlist.

Quality assessment tools

Study quality was assessed using the AXIS Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (Downes, Brennan, Williams, & Dean, Reference Downes, Brennan, Williams and Dean2016). The range of possible scores is from 0 to 20. The AXIS contains 20 items that assess: reporting quality (seven items: 1, 4, 10, 11, 12, 16, and 18), study design quality (seven items: 2, 3, 5, 8, 17, 19, and 20), and possible biases in the study (six items: 6, 7, 9, 13, 14, and 15). All items are scored 1 for ‘Yes’ and 0 for ‘No’, except for items 13 and 19, which are reverse-scored because a ‘Yes’ response indicates a potential source of bias rather than a quality feature.

For RCTs, risk of bias was assessed using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB2: Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Savovic, Page, Elbers, Blencowe, Boutron and Higgins2019). RoB2 classifications are either ‘low’ risk of bias, ‘high’ risk of bias, or ‘some concerns’.

We also used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to assess the quality of evidence for each outcome and give an overview of confidence in the effect sizes (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter, Alonso-Coello and Schünemann2008). GRADE ratings fall into four categories (high, moderate, low, and very low) based on risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision, and publication bias.

Results

Our searches identified and included 14 randomized controlled trials (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Norr, Katz, Gahm and Reger2019; Burger et al., Reference Burger, Hardy, Verdaasdonk, van der Vleugel, Delespaul, van Zelst and van den Berg2025; de Bont et al., Reference de Bont, van den Berg, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van der Gaag and van Minnen2016; Every-Palmer et al., Reference Every-Palmer, Flewett, Dean, Hansby, Freeland, Weatherall and Bell2024; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Kim, Hoon, Park and Lee2010; Marlow et al., Reference Marlow, Laugharne, Allard, Bassett, Priebe, Ledger and Shankar2024; Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Rosenberg, Xie, Jankowski, Bolton, Lu and Wolfe2008, Reference Mueser, Gottlieb, Xie, Lu, Yanos, Rosenberg and McHugo2015; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Hardy, Smith, Wykes, Rose, Enright and Mueser2017; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, Van Minnen and van der Gaag2015, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, De Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2016, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2018; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Sellwood, Pulford, Awenat, Bird, Bhutani and Bentall2024; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Li, Xi, Verma, Zhou and Wang2023); 15 case series studies (Airey, Berry, & Taylor, Reference Airey, Berry and Taylor2023; Brand et al., Reference Brand, Bendall, Hardy, Rossell and Thomas2021; Brand & Loewenstein, Reference Brand and Loewenstein2014; de Bont, van Minnen, & de Jongh, Reference de Bont, van Minnen and de Jongh2013; Keen, Hunter, & Peters, Reference Keen, Hunter and Peters2017; Newman-Taylor, McSherry, & Stopa, Reference Newman-Taylor, McSherry and Stopa2020; Paulik, Steel, & Arntz, Reference Paulik, Steel and Arntz2019; Quevedo, de Jongh, Bouwmeester, & Didden, Reference Quevedo, de Jongh, Bouwmeester and Didden2021; Slotema et al., Reference Slotema, van den Berg, Driessen, Wilhelmus and Franken2019; Strous et al., Reference Strous, Weiss, Felsen, Finkel, Melamed, Bleich and Laub2005; Tong, Simpson, Alvarez-Jimenez, & Bendall, Reference Tong, Simpson, Alvarez-Jimenez and Bendall2017; Trappler & Newville, Reference Trappler and Newville2007; van den Berg & van der Gaag, Reference van den Berg and van der Gaag2012; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Douglas, Dudley, Bowe, Christodoulides, Common and Turkington2021; Ward-Brown et al., Reference Ward-Brown, Keane, Bhutani, Malkin, Sellwood and Varese2018); and 7 case studies (Arens, Reference Arens2015; Brand, Hardy, Bendall, & Thomas, Reference Brand, Hardy, Bendall and Thomas2020; Callcott, Standart, & Turkington, Reference Callcott, Standart and Turkington2004; Cherestal & Herts, Reference Cherestal and Herts2021; Granier & Brunel, Reference Granier and Brunel2022; McCartney et al., Reference McCartney, Douglas, Varese, Turkington, Morrison and Dudley2019; Yasar et al., Reference Yasar, Kiraz, Usta, Abamor, Zengin Eroglu and Kavakci2018). These 36 studies comprised 1,384 participants; of these studies, 29 provided gender composition details (55.53% were female and 44.47% male), and 27 provided age data, leading to an overall mean age of 37.84 years (SD = 9.75; range 16–97). The studies emerged from a variety of countries, including United States (K = 9); Netherlands (K = 9); United Kingdom (K = 8); Australia (K = 3); China (K = 2); France (K = 1); Israel (K = 1); New Zealand (K = 1); South; Korea (K = 1); and Turkey (K = 1).

Study quality

Although the 20 AXIS items are not equally weighted, the mean score for the 36 studies was 14.06 (SD =2.01). The lowest AXIS study quality rating was 10 out of 20 (Granier & Brunel, Reference Granier and Brunel2022), and the highest was 18 (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Kim, Hoon, Park and Lee2010; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Li, Xi, Verma, Zhou and Wang2023). Following recent research (Antczak et al., Reference Antczak, Lonsdale, Lee, Hilland, Duncan, del Pozo Cruz and Sanders2020), we classified AXIS quality scores according to the number of ‘1’ scores for the 20 items for each study – so, studies achieving 80% ‘1’ scores indicated high quality; 60–80% indicated moderate quality; and < 60% indicated low quality. Thus, of 36 studies, 10 (27.78%) were rated as having high quality, 22 (61.11%) as moderate quality, and 4 (11.11%) as low quality.

Trauma-focused interventions

This section includes the TFIs found in the identified studies. As differentiated by Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Cole, Malik, Bell and Bloomfield2023) in line with the principles of Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), both TF-CBT and trauma-informed CBT recognize the impact of trauma on thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; however, TF-CBT combines these elements with exposure to process traumatic memories through desensitization and cognitive restructuring, and the trauma-informed CBT interventions in this review do not have an exposure component. Exposure involves systematic confrontation with a trauma-related memory (imaginal exposure) or reminders of trauma (in vivo exposure) with the aim of encouraging habituation over time and a reduction in trauma response (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Azevedo, Yadav, Keyan, Rawson, Dawson and Hadzi-Pavlovic2023). This approach on its own is often referred to as PE (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, Reference Foa, Hembree and Rothbaum2007). In contrast, while EMDR also involves exposure to trauma-related imagery through visualization, the focus is less on reliving with the aim of habituation and more on using bilateral stimulation such as eye movements during visualization to stimulate reprocessing of traumatic memories (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2001).

Synthesis of main findings

Eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR)

Eleven studies examined EMDR, with nine reporting improvements in psychosis symptoms. Two RCTs (Marlow et al., Reference Marlow, Laugharne, Allard, Bassett, Priebe, Ledger and Shankar2024; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Sellwood, Pulford, Awenat, Bird, Bhutani and Bentall2024) found significant reductions in PANSS scores compared to treatment as usual, and another (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Li, Xi, Verma, Zhou and Wang2023) found positive effects in subclinical psychosis. Several case series reported reduced hallucinations, while one study showed complete remission following a single session. However, one RCT (Every-Palmer et al., Reference Every-Palmer, Flewett, Dean, Hansby, Freeland, Weatherall and Bell2024) found no significant differences in psychosis symptoms, though trauma symptoms improved. Overall, EMDR showed promising effects, especially for delusions, though controlled evidence remains limited.

Prolonged exposure

Four studies evaluated PE, including one RCT using virtual reality delivery (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Norr, Katz, Gahm and Reger2019), which found improvements in hallucinations over time, though not significantly different from waiting list. Case series showed mixed results, with some reporting temporary distress or symptom worsening and discontinuation of treatment (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Bendall, Hardy, Rossell and Thomas2021). While PE may reduce psychosis symptoms in some cases, variability in outcomes and adverse responses deserve caution.

Eye movement desensitization reprocessing or prolonged exposure

Two studies directly compared EMDR and PE. A large RCT (de Bont et al., Reference de Bont, van den Berg, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van der Gaag and van Minnen2016) found both interventions significantly reduced paranoia, with PE effects sustaining longer. However, neither significantly reduced hallucinations. A smaller case series (de Bont et al., Reference de Bont, van Minnen and de Jongh2013) reported reduced PTSD symptoms, with no worsening of symptoms of psychosis. These findings suggest both EMDR and PE may benefit certain symptoms, especially paranoia, though effects on hallucinations remain unclear.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Four uncontrolled case series investigated TF-CBT, most reporting improvements in hallucinations and delusions, maintained at follow-up in some cases (Keen et al., Reference Keen, Hunter and Peters2017; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Douglas, Dudley, Bowe, Christodoulides, Common and Turkington2021). Other case reports also noted reductions in negative symptoms and dissociation. While these findings suggest TF-CBT may benefit different symptom domains, the lack of controlled trials limits conclusions.

Trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy

Four studies used trauma-informed CBT without exposure. Case series showed mostly positive outcomes, although temporary symptom worsening was reported (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Simpson, Alvarez-Jimenez and Bendall2017). Two RCTs (Mueser et al., Reference Mueser, Gottlieb, Xie, Lu, Yanos, Rosenberg and McHugo2015; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Hardy, Smith, Wykes, Rose, Enright and Mueser2017) showed mixed results: both groups reduced PTSD symptoms, but psychosis symptoms did not differ significantly from control or improved more slowly. Trauma-informed CBT may be helpful, particularly when combined with preparatory or stabilizing work, though results were not consistent.

Other trauma-focused interventions

Six studies examined alternative trauma-focused approaches, including imagery rescripting (Newman-Taylor et al., Reference Newman-Taylor, McSherry and Stopa2020; Paulik et al., Reference Paulik, Steel and Arntz2019), trauma management therapy (Arens, Reference Arens2015), and phasic trauma treatment (Brand & Loewenstein, Reference Brand and Loewenstein2014). These generally reported positive effects on paranoia, hallucinations, and trauma-related distress. However, other approaches (e.g., iMAPS or trauma interviews alone) yielded limited or no effect on psychosis symptoms (Airey et al., Reference Airey, Berry and Taylor2023; Strous et al., Reference Strous, Weiss, Felsen, Finkel, Melamed, Bleich and Laub2005). The heterogeneity of methods and designs limits generalizability, though exploratory evidence suggests imagery-based approaches may be promising.

Overall, EMDR, TF-CBT, and PE were conceptualized as including exposure. All other TFIs examined (i.e., imagery rescripting, trauma-informed CBT, trauma management therapy, phasic trauma treatment, iMAPS, and trauma interviews) were categorized as non-exposure approaches, as they do not involve systematic or prolonged confrontation with trauma memories.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis synthesis of studies was conducted by two authors (KRL and ER) using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 4.0. All final meta-analyses including meta-regression were completed by KRL. Primary outcomes were hallucinations and delusions, with negative symptoms of psychosis, PTSD, depression, anxiety, functioning, and quality of life as secondary outcomes. For between-group comparisons, we assessed effect sizes for the end of trial and follow-up. Both people with subclinical symptoms of psychosis (e.g., Brand & Loewenstein, Reference Brand and Loewenstein2014; Newman-Taylor et al., Reference Newman-Taylor, McSherry and Stopa2020) and clinical populations were included in meta-analyses. Random effect models were used for all analyses. Hedge’s g effect sizes were calculated for pre–post treatment effects across all studies. A correlation of 0.5 was assumed between pre- and post-analyses. For RCTs, we ran analyses comparing end-of-trial symptom scores for intervention and control groups. If studies did not provide means and standard deviations, effect sizes were calculated using r values and sample size (see van den Berg & van der Gaag, Reference van den Berg and van der Gaag2012). The Q and I 2 statistics were used to assess effect size heterogeneity.

For meta-regression and subgroup analyses, we followed the recommendations of no fewer than ten studies for a continuous variable and at least four studies per group for a categorical subgrouping variable (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Gartlehner, Grant, Shamliyan, Sedrakyan, Wilt and Trikalinos2011). Following guidance from the Cochrane Handbook on Systematic Reviews (Cumpston et al., Reference Cumpston, Li, Page, Chandler, Welch, Higgins and Thomas2019), tests for funnel plot asymmetry were applied to analyses where at least ten studies were included in the meta-analysis (as fewer studies make the power of tests too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry). Of the 36 studies included in the systematic review, 18 were included in the meta-analyses. Reasons for exclusion from meta-analyses included: case studies with small numbers, i.e., one or two participants (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Hardy, Bendall and Thomas2020; Callcott et al., Reference Callcott, Standart and Turkington2004; Cherestal & Herts, Reference Cherestal and Herts2021; Granier & Brunel, Reference Granier and Brunel2022; McCartney et al., Reference McCartney, Douglas, Varese, Turkington, Morrison and Dudley2019; Yasar et al., Reference Yasar, Kiraz, Usta, Abamor, Zengin Eroglu and Kavakci2018), lacking data (Slotema et al., Reference Slotema, van den Berg, Driessen, Wilhelmus and Franken2019; Trappler & Newville, Reference Trappler and Newville2007; Ward-Brown et al., Reference Ward-Brown, Keane, Bhutani, Malkin, Sellwood and Varese2018), not focusing on hallucinations, delusions, or negative symptoms (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Simpson, Alvarez-Jimenez and Bendall2017), analyzing only pre–post data on negative symptoms (Strous et al., Reference Strous, Weiss, Felsen, Finkel, Melamed, Bleich and Laub2005), including only outcomes on positive symptoms (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Li, Xi, Verma, Zhou and Wang2023), using the same sample with other studies (Burger et al., Reference Burger, Hardy, Verdaasdonk, van der Vleugel, Delespaul, van Zelst and van den Berg2025; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, Van Minnen and van der Gaag2015, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, De Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2016, Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh, van Minnen and van der Gaag2018), or using unreliable or single-item outcome measures (Arens, Reference Arens2015; Buck et al., Reference Buck, Norr, Katz, Gahm and Reger2019).

Hallucinations (pre–post)

Fourteen studies (15 samples; N = 506) were included in the meta-analysis for hallucinations. Pre–post analyses indicated significant post-treatment effects for hallucinations (Hedge’s g = −0.37 [95% CI −0.50, −0.24]; prediction interval −0.72 to −0.02), suggesting a small–moderate reduction in reported symptoms of hallucinations following TFIs. The forest plot showing the within-groups analysis for hallucinations at post-treatment is presented in Figure 2. Heterogeneity was moderate (Q = 22.71, df = 14, p = .07; I 2 = 38.34). Trim-and-fill analysis suggested five potentially missing studies. The resulting adjusted effect size was reduced, but remained significant (g = −0.28; 95% CI −0.43 to −0.13).

Figure 2. Pre–post analyses for hallucinations.

Observation of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry and possible small-study effects (see Supplementary Appendices).

Hallucinations (between group) – end of trial and follow-up

Six studies (seven samples) used RCTs to compare TFIs to a control group at the end of trial (N = 222 intervention and N = 172 control) and at follow-up (N = 190 intervention and N = 147 control). The effect size for TFIs did not differ significantly from controls at the end of trial (g = −0.12 [95% CI −0.32 to 0.08]), with no heterogeneity (Q = 3.43, df = 6, p = .75; I 2 = 0); or at follow-up (g = −0.01 [95% CI −0.23 to 0.21]), with no heterogeneity (Q = 2.63, df = 6, p = .85; I 2 = 0; see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hallucination ratings in between-group comparisons at the end of trial and follow-up.

Delusions (pre–post)

Thirteen studies (14 samples; N = 447) were included in the meta-analysis for delusions. Pre–post analyses using CMA indicated significant post-treatment effects for delusions (Hedge’s g = −0.49, 95% CI [−0.67, −0.32], p < .001) with a prediction interval of −1.08 to 0.09. The heterogeneity statistics suggested moderate heterogeneity (Q = 36.10, df = 13, p < .001; I 2 = 63.99). Overall, the findings indicate a reduction in the reported symptoms of delusions following TFIs with a medium effect size (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pre–post analyses for delusions.

The funnel plot did not indicate any asymmetry that might suggest small study effects and possible publication bias (see Supplementary Appendices).

Delusions (between-group) – end of trial and follow-up

Six studies (seven samples) used RCTs to compare TFIs to a control group at the end of trial (N = 268 intervention and N = 194 control) and at follow-up (N = 249 intervention and N = 176 control). The effect size for TFIs differed significantly from controls at the end of trial (g = −0.44 [95% CI –0.86 to −0.02]), with high heterogeneity (Q = 26.74, df = 6, p < .001; I 2 = 77.56); prediction interval −1.82 to 0.94; and at follow-up (g = −0.48 [95% CI –0.73 to −0.22]); prediction interval −1.07 to 0.12; with moderate heterogeneity (Q = 8.91, df = 6, p = .18; I 2 = 32.68; see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Delusions ratings in between-group comparisons at the end of trial and follow-up.

Negative symptoms of psychosis (between-group) – end of trial and follow-up

Six end-of-trial between-group comparisons (intervention N = 192; controls N = 158) were included in the meta-analysis of negative symptom outcomes. Analysis of these studies found no significant reduction in negative symptoms at the end of trial (g = −0.02; 95% CI [−0.26, 0.23], p = .89). The prediction interval was large at −0.53 to 0.50. Heterogeneity was moderate (Q = 6.17, df = 5, p = .29; I 2 = 19.01). At follow-up, analysis of these studies found a small but significant reduction in negative symptoms (g = −0.26; 95% CI [−0.48, −0.04], p = .02). Heterogeneity was low (Q = 1.75, df = 5, p = .88; I 2 = 0; see Figure 6). The forest plots did not show any asymmetry at either end of trial or follow-up.

Figure 6. Negative symptoms of psychosis ratings in between-group comparisons at the end of trial and follow-up.

GRADE ratings

GRADE ratings indicate varying levels of confidence in the evidence for TFIs (see Supplementary Appendices). For uncontrolled pre–post studies, the evidence is rated as very low confidence for hallucinations and low for delusions – this partly reflects risk of bias from the lack of control groups, inconsistency in effect sizes, and imprecision from wide confidence intervals. Hallucinations also showed potential publication bias.

By contrast, evidence from between-group RCTs was rated moderate for hallucinations, delusions, and negative symptoms. Hallucinations produced consistent null findings with little or no heterogeneity. By contrast, controlled studies of delusions were downgraded for inconsistency, and negative symptoms were downgraded for imprecision. No clear evidence of publication bias was found for between-group outcomes. Overall, the strongest confidence in evidence exists for controlled trials of delusions, while evidence for any reduction of hallucinations and negative symptoms is minimal or less convincing.

Moderator analyses

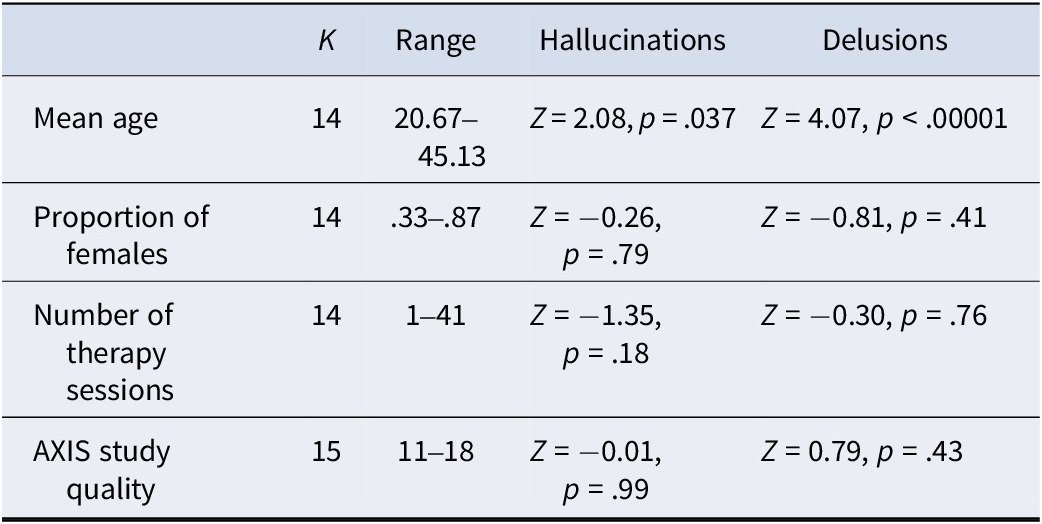

Moderator analyses were conducted on pre–post analyses for hallucinations and delusions as the number of controlled between-group studies was too few to derive reliable moderator analyses. Meta-regression analyses showed that the number of sessions, the proportion of female patients, and AXIS study quality did not predict effect sizes for hallucinations or delusions. In contrast, age was a highly significant predictor of effect size for delusions and marginally significant for hallucinations, with greater efficacy in studies with younger samples (See Table 2).

Table 2. Meta-regression analyses for pre–post hallucination and delusion effect sizes

We used a subgroup analysis to compare effect sizes for hallucinations in pre–post studies using exposure (g = −0.35 [−0.47, −0.22]; K = 10) versus no exposure (g = −0.46 [−0.82, −0.11]; K = 5) and found no difference (Q = 0.37, df = 1, p = .54). A subgroup analysis was also used to compare delusion effect sizes for pre–post studies involving exposure (g = −0.56 [−0.76, −0.37]; K = 10) and no exposure (g = −0.31 [−0.62, −0.01]; K = 4) and again found no difference (Q = 1.81, df = 1, p = .18).

Further, several studies were identified as feasibility trials (Airey et al., Reference Airey, Berry and Taylor2023; Brand et al., Reference Brand, Bendall, Hardy, Rossell and Thomas2021; de Bont et al., Reference de Bont, van Minnen and de Jongh2013; Keen et al., Reference Keen, Hunter and Peters2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Kim, Hoon, Park and Lee2010; Quevedo et al., Reference Quevedo, de Jongh, Bouwmeester and Didden2021; Slotema et al., Reference Slotema, van den Berg, Driessen, Wilhelmus and Franken2019; van den Berg & van der Gaag, Reference van den Berg and van der Gaag2012; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Sellwood, Pulford, Awenat, Bird, Bhutani and Bentall2024; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Li, Xi, Verma, Zhou and Wang2023). An exploratory examination revealed no difference in pre–post effect sizes for delusions in feasibility (g = −.50 [−.72 to −.28; K = 9) versus other trials (g = −.48 [−.81 to −.16] K = 5): Q = .01, df = 1, p = .93). Similarly, for pre–post hallucination, effect sizes for feasibility (g = −.38 [−.56 to −.20; K = 9) and other trials did not differ (g = −.37 [−.56 to −.17] K = 6): Q = .01, df = 1, p = .92). Only one RCT (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Sellwood, Pulford, Awenat, Bird, Bhutani and Bentall2024) was confirmed as a feasibility trial, and so, we did not analyze RCTs alone.

Secondary outcomes

Meta-analyses of between-group comparisons were conducted for PTSD, depression, anxiety, functioning, and quality of life at the end of treatment and follow-up. For PTSD symptoms (K = 6), small but significant effects favoring the intervention were observed at the end of treatment (g = −0.36, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.12, I 2 = 35%) and follow-up (g = −0.31, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.08, I 2 = 25%). For depression (K = 7), effects were small and not statistically significant at either time point: end of treatment (g = −0.24, 95% CI −0.51 to 0.02, I 2 = 58%) and follow-up (g = −0.11, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.13, I 2 = 50%). Similarly for anxiety symptoms (K = 5), no significant effects were found at the end of treatment (g = −0.16, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.11, I 2 = 46%) or follow-up (g = −0.17, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.01, I 2 = 0%). For functioning (K = 6), there was no effect at the end of treatment (g = 0.12, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.29, I 2 = 0), but a small, significant improvement emerged at follow-up (g = 0.28, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.45, I 2 = 0). For quality of life (K = 3), no significant effects were observed at either end of treatment (g = −0.13, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.10, I 2 = 0) or follow-up (g = −0.07, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.16, I 2 = 0).

Risk of bias

Our searches identified 14 controlled trials, though four were reanalyses of the same trial and one used single-item outcome measures to capture psychosis-like experiences. We therefore conducted Cochrane RoB2 analyses of nine individual trials (see Supplementary Appendices). These showed that none of the included trials were at high risk of bias overall or in any individual domain.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 36 studies (N = 1,384) evaluating the efficacy of TFIs for psychosis. Our meta-analyses provide updated evidence that TFIs consistently reduce delusions, with moderate effect sizes observed across both uncontrolled and controlled trials, including at follow-up. In contrast, hallucinations did not significantly improve in controlled trials, and although small-to-moderate improvements were seen in pre–post designs, these were attenuated after adjusting for publication bias. These findings indicate symptom-specific variability in treatment response, suggesting potentially distinct underlying mechanisms and a need for tailored intervention strategies.

Our analysis of RCTs revealed a dissociation in the effects of TFIs on delusions and hallucinations; with a significant and lasting reduction in delusions, but not for hallucinations. These findings reinforce and expand upon the previous meta-analysis of Brand et al. (Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018), who similarly reported stronger TFI effects for delusions than for hallucinations. By tripling the number of studies included (K = 15 for delusions and K = 14 for hallucinations in pre–post analyses; K = 7 for each in controlled trials), we increase the statistical power and precision of this conclusion. Although effect sizes for delusions were comparable at the end of trial and follow-up, the prediction interval for follow-up was much smaller than that for the end of trial. These findings suggest that immediate treatment effects for delusions are quite variable across studies, while long-term effects are more stable and predictable. One clear implication is that the expected range of true effects for delusions appears more favorable at follow-up than at the end of trial, suggesting that TFIs produce a more stable and sustained reduction in delusional symptoms over time. This may reflect the challenging nature of TFIs, which can initially increase distress or exacerbate delusional thinking for some individuals.

In contrast to the findings for delusions, none of the RCTs conducted to date have reported a statistically significant reduction in hallucinations. It is important to recognize that several trials included relatively small samples, including one feasibility study (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Sellwood, Pulford, Awenat, Bird, Bhutani and Bentall2024), meaning that very small effects may not have been detectable. However, small sample size alone is unlikely to fully account for the pattern of results. The same seven RCTs that yielded no effect on hallucinations did detect moderate reductions in delusions at both end of trial and follow-up, indicating that the designs were capable of detecting effects of that magnitude. To examine this issue more formally, we calculated the minimum detectable effect size (MDES) for hallucination outcomes. Across RCTs, observed effects on hallucinations were small (g = −0.12 at end of trial; g = −0.01 at follow-up) and showed no between-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%). While MDES estimates indicate that trials were only powered to detect effects of approximately g ≥ 0.30 – so very small effects may have gone undetected – the consistently near-zero effect sizes suggest that any true impact of TFIs on hallucination outcomes is likely to be minimal. Together, these findings imply that TFIs may have limited influence on hallucinations, even if modest, sub-detectable effects cannot be ruled out.

While TFIs appear to impact the severity of delusions but not hallucinations, it remains possible that hallucination severity may be less appropriate than, for example, hallucination distress as a target for TFIs. Indeed, psychological therapy trials for psychosis have historically followed a pharmacological model of outcomes, placing primary emphasis on reducing positive symptoms (for discussion, see Birchwood & Trower, Reference Birchwood and Trower2006; Laws et al., Reference Laws, Darlington, Kondel, McKenna and Jauhar2018). Similarly, most studies in the current review focused on symptom reduction, with few studies examining reductions in distress associated with such symptoms. Although only two studies in the current review (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Bendall, Hardy, Rossell and Thomas2021; Paulik et al., Reference Paulik, Steel and Arntz2019) assessed the impact of TFIs on distress associated with hallucinations, both reported large pre–post reductions in the distress associated with hallucinations. Future research should more explicitly prioritize patient-centered outcomes such as distress associated with hallucinations, as well as functioning and quality of life in sufficiently powered trials. These findings underline the importance of selecting outcomes that map onto the psychological processes TFIs are most likely to influence, particularly when assessing hallucinations.

This symptom-specific pattern of response raises important questions about the underlying mechanisms driving treatment effects. Hallucinations and delusions have both been associated with childhood trauma (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Alvarez-Jimenez, Garcia-Sanchez, Hulbert, Barlow and Bendall2018), thus underpinning the rationale for TFIs in psychosis. Nonetheless, the differential treatment response seen here – in the same samples – points to possible differences in the underlying mechanisms of these two symptoms. Delusions, particularly paranoid or persecutory types, are often conceptualized as arising from maladaptive threat-based appraisals shaped by trauma (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garety, Kuipers, Fowler and Bebbington2002; Garety et al., Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington2001). In such cases, trauma-focused work may help individuals reconstruct more adaptive narratives, potentially diminishing the need for delusional explanations. By addressing maladaptive trauma-related schemas (e.g., beliefs about danger, trust, and self-worth), TFIs may effectively reduce the cognitive bias and threat perception that fuel delusional ideation (Brand et al., Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Fowler, Freeman, Smith, Steel, Evans and Garety2005). While trauma exposure has been linked to the content and distress of hallucinations (Peach et al., Reference Peach, Alvarez-Jimenez, Cropper, Sun, Halpin, O’Connell and Bendall2021), the core phenomenology of hearing voices appears to be less responsive to change through both cognitive-based and exposure-based trauma interventions. Hallucinations – particularly auditory hallucinations – may differ because they are primarily associated with alterations in perceptual processing and underlying neural activity (Allen, Larøi, McGuire, & Aleman, Reference Allen, Larøi, McGuire and Aleman2008; Waters et al., Reference Waters, Allen, Aleman, Fernyhough, Woodward, Badcock and Larøi2012; Zmigrod, Garrison, Carr, & Simons, Reference Zmigrod, Garrison, Carr and Simons2016). Indeed, hallucinations may stem from dissociative processes that persist independently of trauma meaning-making (Longden, Madill, & Waterman, Reference Longden, Madill and Waterman2012). So, although trauma may influence the content and emotional salience of hallucinations (Steel, Reference Steel2015), TFIs may not directly address the perceptual anomalies or dissociative processes that give rise to the experience of hearing voices (see Frost, Collier, & Hardy, Reference Frost, Collier and Hardy2024). TFIs may therefore be well suited to altering trauma-related beliefs that fuel delusions, but have limited impact on the neurocognitive and perceptual mechanisms associated with hallucinations. These findings also suggest that collapsing delusions and hallucinations into a single ‘positive symptom’ outcome may obscure differential treatment effects and mechanisms (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Garety, Freeman, Craig, Kuipers, Bebbington and Dunn2007).

Beyond symptom-specific mechanisms, individual characteristics may also shape differential response to TFIs. Our moderator analyses revealed that younger age significantly predicted larger pre–post TFI treatment effects for delusions and to a lesser extent also for hallucinations. This age-related effect may reflect multiple factors, including shorter illness duration, greater neurocognitive plasticity, or higher engagement among younger individuals. Younger people with psychosis are more likely to be in the early stages of illness, which has been associated with better responsiveness to psychological interventions (Stafford et al., Reference Stafford, Mayo-Wilson, Loucas, James, Hollis, Birchwood and Kendall2015). Additionally, adolescents and young adults may retain greater neural flexibility, potentially enhancing their capacity to benefit from trauma-focused work (Paus, Keshavan, & Giedd, Reference Paus, Keshavan and Giedd2008). Additional planned moderator analyses of pre–post effect sizes for hallucinations and delusions showed that neither gender (proportion of female participants), number of therapy sessions, nor study quality significantly moderated treatment effects. Furthermore, and contrary to previous reports (Brand et al., Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018), we also did not find any higher efficacy for TFIs incorporating exposure techniques (e.g., EMDR, PE). However, this finding was based on pre–post analyses, and further research, especially using longitudinal or follow-up designs, is suggested to examine this result thoroughly.

Although the primary focus of this review was on positive symptoms, the differential pattern of effects also extended to negative symptoms. Although TFIs did not significantly reduce negative symptoms at the end of treatment, a small but significant improvement emerged at follow-up. This is a notable finding given the well-established difficulty of treating negative symptoms (Erhart, Marder, & Carpenter, Reference Erhart, Marder and Carpenter2006), though it should be interpreted cautiously. Negative symptoms were not a primary outcome in most included studies, and the review’s search strategy was not optimized for capturing them, raising the possibility that available data underestimate or incompletely reflect TFI effects. Moreover, small statistically significant improvements in negative symptoms – common across both pharmacological and psychological interventions – do not always translate into clinically meaningful change (see Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Papanastasiou, Stahl, Rocchetti, Carpenter, Shergill and McGuire2015). Nonetheless, theoretical work suggests that aspects of negative symptomatology, such as emotional numbing, anhedonia, and social withdrawal, may overlap with trauma-related avoidance and emotional suppression (Brand et al., Reference Brand, McEnery, Rossell, Bendall and Thomas2018; McGorry, Reference McGorry1991). TFIs that reduce avoidance and facilitate emotional processing could therefore plausibly influence negative symptoms over time. Future research should examine these potential shared mechanisms directly and assess whether TFIs can produce sustained and clinically relevant improvements in negative symptoms.

The symptom-specific pattern of response was broadly mirrored in secondary outcomes. We report small improvements in PTSD symptoms at both end of treatment and follow-up, as well as a modest enhancement in functioning at follow-up. However, TFIs did not significantly improve depression, anxiety, or quality of life outcomes at any time point. Nevertheless, whether such null findings represent a true lack of efficacy or not is hard to determine. Secondary outcomes have been assessed in only a small number of trials and crucially, not typically as a direct focus of TFIs and so may be both underpowered and insufficiently focused to detect such effects.

The current findings should also be considered in light of several methodological limitations that qualify the strength of the evidence. These methodological considerations are crucial for guiding the next generation of TFIs, which will need to be explicitly shaped around symptom-specific mechanisms and patient-centered outcomes. While pre–post designs permit meta-analyses of more studies and therefore enable moderator analyses, pre–post analyses are vulnerable to confounding influences such as spontaneous remission, regression to the mean, and placebo effects (Cuijpers, Weitz, Cristea, & Twisk, Reference Cuijpers, Weitz, Cristea and Twisk2017). This limitation reinforces the importance of assessing controlled trials, which did confirm the moderate reduction for delusions, but not hallucinations. The confidence associated with evidence from pre–post studies (as rated using the GRADE) was low for delusions and very low for hallucinations. By contrast, all GRADE ratings for controlled studies of hallucinations and delusions at the end of trial and at follow-up revealed moderate confidence in the findings. Further, we note that on the Cochrane RoB2 assessment, none of the RCTs were deemed at high risk of bias, and all studies included in the review were rated as having moderate-to-high quality using the AXIS scale. In this context, the end of trial and follow-up analyses do provide reliable indicators of the true effects of TFIs for delusions and hallucinations.

Conclusion

Together, these findings provide consistent evidence for a symptom-specific pattern of TFI response, with robust effects on delusions but less impact on hallucinations. This systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that TFIs are effective in reducing delusional symptoms in individuals with psychosis, with gains that are maintained over time. In contrast, TFIs showed limited efficacy for hallucinations, particularly in controlled trials at the end of trial or follow-up. Some benefit emerged in pre–post analyses, though they appeared to reflect the evidence of possible publication bias/small study effects. A significant reduction in negative symptoms at follow-up also emerged, although this outcome was not a central focus of the included studies and warrants further investigation. These findings suggest TFIs may be more effective for cognitive-affective processes underpinning delusions than for perceptual or dissociative mechanisms associated with hallucinations. Accordingly, future trials should treat hallucination distress – not severity – as a primary outcome when evaluating TFIs. These results expand upon earlier findings by including substantially more studies, especially RCTs, and offer the first reliable moderator analyses for delusions and hallucinations, albeit in pre–post analyses. The number of controlled trials nonetheless remains limited, and many studies did not directly address psychosis-related trauma, which may have influenced symptom-specific treatment outcomes. Researchers might also place greater emphasis on examining more patient-centered outcomes – such as functioning and quality of life – which would enhance clinical relevance. Future research should focus on (1) targeting trauma directly linked to symptoms of psychosis, (2) distinguishing between symptom domains when assessing treatment efficacy, and (3) identifying mechanisms and moderators that account for differential response. The evidence therefore points toward a future in which TFIs are developed and evaluated with explicit attention to symptom domain, underlying mechanism, and outcomes that matter to the patient.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725103036.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Kim T. Mueser and colleagues for sharing their data from two studies with us. We are also grateful to Professor Filippo Varese for his expert advice on the direction and scope of the review, particularly in relation to ongoing developments in the trauma and psychosis literature.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.