Impact statement

Continuous traumatic stress (CTS) has generated debate in the context of current definitions of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the DSM-5. Prevalence data on posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and PTSD in adolescents aged 10 to 24 years exposed to CTS in Sub-Saharan Africa are lacking. In the 10 studies identified, the pooled prevalence of PTSS/PTSD in sub-Saharan adolescents exposed to CTS was 32.0%, with a higher prevalence in middle-income countries (39.34%) compared to low-income countries (24.60%). Studies using clinician-administered measures reported higher PTSS/PTSD rates (49.0%) compared to studies utilizing self-report measures (28.0%). These findings highlight the need to assess PTSS/PTSD among adolescents exposed to CTS particularly in middle-income countries where rapid urbanization may heighten CTS exposure and its adverse consequences – rather than limiting assessment to a single past DSM-5 Criterion A traumatic event. Future research should incorporate multiple approaches to assessing PTSS/PTSD, including a CTS-specific measure as well as both self-report and clinician-administered tools. It is also important to measure responses to CTS as a construct distinct from PTSS, to gain a clearer understanding of how CTS affects adolescents’ development and mental health. Such insights can guide the design of future interventions. Finally, measures of CTS response should be standardized and culturally adapted for use not only in Sub-Saharan Africa but also across diverse global contexts.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa has been, and still is, impacted by continuous wars and armed conflicts over several decades (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Stevenson, Kalapurakkel, Hanlon, Seedat, Harerimana, Chiliza and Koenen2020). Notably, countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007) and Sudan (Rolandsen and Leonardi, Reference Rolandsen and Leonardi2014) have been experiencing ongoing conflicts and political instability since 1960. Furthermore, people living in Sub-Saharan Africa face continuous traumatic stressors (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Stevenson, Kalapurakkel, Hanlon, Seedat, Harerimana, Chiliza and Koenen2020). In South Africa, gender-based violence (Dlamini, Reference Dlamini2021) and gang-related violence (Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Hinsberger, Elbert, Holtzhausen, Kaminer, Seedat, Madikane and Weierstall2017) have significantly increased since the COVID-19 pandemic. Of concern is the increase in gang-related violence in schools, where adolescents have become targets of gang leaders (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Daniels and Tomlinson2019). Furthermore, Burkina Faso (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016), Uganda (Okello et al., Reference Okello, De Schryver, Musisi, Broekaert and Derluyn2014), and Kenya (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021) report high levels of ongoing emotional abuse, especially in poorer and previously disadvantaged communities. Among adolescents specifically, bullying has reached epidemic proportions, including in Ghana (Acquah et al., Reference Acquah, Wilson and Doku2014), Mozambique (Peltzer and Pengpid, Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2020), and Sierra Leone (Aboagye et al., Reference Aboagye, Seidu, Hagan, Frimpong, Budu, Adu, Ayilu and Ahinkorah2021). People living in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially adolescents, both individually and collectively, encounter high levels of ongoing trauma exposure (Hynd, Reference Hynd2021; Kimemia, Reference Kimemia2021).

Continuous traumatic stress exposure and response

While extant data describe PTSD consequent to war (Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Zasiekina, Guterman and Pat-Horenczyk2025), armed conflict (Agbaria et al., Reference Agbaria, Petzold, Deckert, Henschke, Veronese, Dambach, Jaenisch, Horstick and Winkler2021), gender-based violence (Enaifoghe et al., Reference Enaifoghe, Dlelana, Abosede Durokifa and Dlamini N2021), and gang-related violence (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Daniels and Tomlinson2019), these data focus on traumatic events as past and/or singular events since the diagnostic nomenclature of PTSD conceptualises it as a disorder resulting from past trauma (Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023, Reference Leshem, Zasiekina, Guterman and Pat-Horenczyk2025). Evidence for the association of continuous and ongoing exposure in the context of PTSD is lacking, especially among Sub-Saharan African adolescents.

The term ‘continuous traumatic stress’ (CTS) redefined the bounds of trauma. CTS exposure describes persistent and ongoing exposure to traumatic stressors, particularly in contexts of political violence, social upheaval, or prolonged conflict, where the threat is chronic rather than episodic, and collective rather than interpersonal (Straker and The Sanctuaries Counseling Team, Reference Straker1987; Straker, Reference Straker2013). While PTSS mainly include intrusion symptoms, persistent avoidance of stimuli, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and marked alterations in arousal and reactivity (Avanci et al., Reference Avanci, Serpeloni, De Oliveira and De Assis2021), CTS exposure is associated with dejection, somatization, feelings of hopelessness, and a persistent fixation on the possibility of future traumas (Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023). Notably, PTSS refers to trauma-related symptoms that an individual may experience even when the full diagnostic criteria for PTSD, as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), are not met.

The concept of CTS exposure and its resultant response (i.e., CTS response) has been further developed by various scholars (e.g., Nuttman-Shwartz and Shoval-Zuckerman, Reference Nuttman-Shwartz and Shoval-Zuckerman2016; Goral et al., Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021; Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023; Zasiekina and Martyniuk, Reference Zasiekina and Martyniuk2025). Goral et al. (Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021) recently developed the Continuous Traumatic Stress Response Scale (CTS-RS) that differentiates three clusters (subscales) of responses to CTS exposure, including exhaustion/detachment, rage/betrayal, and fear/helplessness. This underscores that a CTS response is not fully captured by the PTSD construct alone (Levin et al., Reference Levin, Ben-Ezra, Hamama-Raz, Maercker, Goodwin, Leshem and Bachem2023; Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Zasiekina, Guterman and Pat-Horenczyk2025; Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Griffin, Blakemore, Hlova and Bignardi2025). Instead, determining CTS response rates requires exploration of additional distress markers, such as depression and anxiety (Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023; Levin et al., Reference Levin, Ben-Ezra, Hamama-Raz, Maercker, Goodwin, Leshem and Bachem2023; Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Goral, Fedotova, Akimova and Martyniuk2024, Reference Zasiekina, Griffin, Blakemore, Hlova and Bignardi2025) and is thought to have distinct manifestations compared to single or multiple past traumas. CTS exposure includes experiences such as the destruction of infrastructure and the loss of family members, which severely undermine essential social support networks. Due to its ongoing nature, CTS response is characterized by difficulties in anticipating both real and perceived threats, making it a uniquely complex form of trauma (Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Goral, Fedotova, Akimova and Martyniuk2024; Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Zasiekina, Guterman and Pat-Horenczyk2025).

Unlike trauma confined to the past, CTS exposure occurs within a specific and ongoing context that must account for the political, socio-economic, and cultural setting. In their study among Lithuanian adolescents exposed to continuous violence (n = 321, aged 13-17 years), Truskauskaite et al. (Reference Truskauskaite, Kvedaraite, Goral and Daniunaite2025) found that the intensity of exposure to neglect, psychological abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse positively predicted severe CTS response (CTS-RS≤18). Another study documented that war-related ongoing trauma exposure among Ukrainian nurses (n = 130, aged 20-74 years) was associated with significant levels of CTS response as measured by the CTS-RS (Zasiekina and Martyniuk, Reference Zasiekina and Martyniuk2025). In their validation study of the CTS-RS among adults exposed to an ongoing security threat in Israel (n = 313, mean age = 41.1 years), Goral et al. (Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021) categorized 94.2% of the sample as having high CTS-RS scores. While participants’ CTS-RS scores did not meet the criteria for PTSD, it is notable that 62.2% endorsed significant PTSS.

CTS exposure and PTSS/PTSD

Although CTS exposure can cause a wide range of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses that go beyond PTSS, there is a significant positive association between CTS exposure and clinically significant PTSS (Agbaria et al., Reference Agbaria, Petzold, Deckert, Henschke, Veronese, Dambach, Jaenisch, Horstick and Winkler2021; Avanci et al., Reference Avanci, Serpeloni, De Oliveira and De Assis2021; Goral et al., Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021; Truskauskaite et al., Reference Truskauskaite, Kvedaraite, Goral and Daniunaite2025). A systematic review of studies in Palestinian children and adolescents exposed to ongoing political violence (n = 15121, aged 4.5-17.1 years), identified a pooled PTSD prevalence of 36% (Agbaria et al., Reference Agbaria, Petzold, Deckert, Henschke, Veronese, Dambach, Jaenisch, Horstick and Winkler2021). Accordingly, Avanci et al. (Reference Avanci, Serpeloni, De Oliveira and De Assis2021) found clinical levels of PTSD among 7.8% of Brazilian adolescents (n = 862, mean age = 15 years) exposed to continuous violence, such as community, family, physical, and psychological violence. Notably, the prevalence of PTSS and PTSD among adolescents exposed to CTS in Sub-Saharan Africa remains underreported (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Stevenson, Kalapurakkel, Hanlon, Seedat, Harerimana, Chiliza and Koenen2020) and under-researched. These data are important for making informed decisions about mental health prevention and intervention, particularly as adolescents are exposed to CTS during critical stages of development and socialization (Agbaria et al., Reference Agbaria, Petzold, Deckert, Henschke, Veronese, Dambach, Jaenisch, Horstick and Winkler2021; Avanci et al., Reference Avanci, Serpeloni, De Oliveira and De Assis2021). CTS exposure can negatively affect developmental trajectories (such as executive functioning and social and emotional learning) and lead to maladaptive behaviors and poor mental health outcomes (Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023; Levin et al., Reference Levin, Ben-Ezra, Hamama-Raz, Maercker, Goodwin, Leshem and Bachem2023; Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Griffin, Blakemore, Hlova and Bignardi2025; Zasiekina and Martyniuk, Reference Zasiekina and Martyniuk2025).

The negative consequences and potential snowballing effect of perpetuated violence following CTS exposure are further exacerbated by poor mental health care access due to financial barriers (Aguwa et al., Reference Aguwa, Carrasco, Odongo and Riblet2023), the high population burden of mental disorders (Arias et al., Reference Arias, Saxena and Verguet2022), and mental health-related stigma (Koschorke et al., Reference Koschorke, Oexle, Ouali, Cherian, Deepika, Mendon, Gurung, Kondratova, Muller, Lanfredi, Lasalvia, Bodrogi, Nyulászi, Tomasini, El Chammay, Abi Hana, Zgueb, Nacef, Heim, Aeschlimann, Souraya, Milenova, Van Ginneken, Thornicroft and Kohrt2021) in Sub-Saharan Africa. As such, a clearer understanding of the association between CTS exposure and PTSS and/or PTSD (hereafter referred to as PTSS/PTSD) is needed to develop contextually and culturally relevant mental health interventions.

Study aims and objectives

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) was to establish the pooled prevalence of PTSS/PTSD among adolescents exposed to CTS by synthesizing data from studies conducted within Sub-Saharan Africa. Our research questions were:

-

(i) What is the prevalence of PTSS/PTSD among adolescents aged 10 to 24 years exposed to CTS in Sub-Saharan Africa?

-

(ii) What are the other common trauma-related mental disorders in adolescents in this age group?

-

(iii) What are the moderators for PTSS/PTSD, including country-level income (World Bank categories), sex, age, education, recruitment methods, PTSS/PTSD measure, or sample type (i.e., purposive vs random) following CTS exposure?

Method

This SRMA was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024587060) and was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, JE, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, LA, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021).

Literature search

Medline (PubMed), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost) and PTSDpubs (ProQuest) were systematically searched for eligible articles on 8 August 2024 (updated search: 23 October 2024). The identified list of articles was compared to the results of another literature search in Research4Life, a platform that provides institutions in lower-income countries with online access to academic and professional peer-reviewed content.

The keywords were (adolescent OR young adult OR child OR teen OR youth OR student OR emerging adult) AND (stress disorder OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR posttraumatic stress disorder OR posttraumatic stress disorder OR posttraumatic stress disorder) AND (mental health OR mental health symptoms OR continuous traumatic stress OR ongoing violence OR continuous violence OR continuous threat OR ongoing threat OR cycle of violence OR multiple exposure). The research strategy is detailed in the Supplementary Materials section.

Eligibility criteria

Full-text quantitative, empirical, and randomized control studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2004 and 2024 were included. Grey literature and review articles (scoping, systematic, and literature) were excluded.

Population and CTS exposure

Similar to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on war-related PTSD prevalence among adolescents (Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Griffin, Blakemore, Hlova and Bignardi2025), the target population was adolescents and youth aged 10 to 24 years living in Sub-Saharan Africa who were exposed to CTS. The selected age range was based on findings that the transition period between childhood and adulthood spans a broader range (i.e., 10-24 years) (Erikson, Reference Erikson1993; Batra, Reference Batra2013) due to various factors, including protracted brain development (Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Griffin, Blakemore, Hlova and Bignardi2025).

For this study, we defined CTS exposure as exposure to the cycle of violence, war and armed conflicts, domestic abuse, and situations where there is a constant threat. This encompassed ongoing exposure to severe interpersonal traumas, gang violence and violent protests, in addition to political, social and economic instability (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Stevenson, Kalapurakkel, Hanlon, Seedat, Harerimana, Chiliza and Koenen2020; Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023).

Reported outcomes and additional information

Studies had to report on the prevalence of clinically significant PTSS (i.e., meeting the threshold for probable disorder) and/or PTSD as determined using either screening or diagnostic PTSS/PTSD measures with robust psychometric reliability and validity. Included studies had to provide sufficient information to determine study-level factors (World Bank country income category, sex/gender, age, education, or PTSS/PTSD measure) associated with the pooled prevalence of PTSS/PTSD. For studies where this information was not provided, the corresponding author was contacted via email and the information was requested. Only one author responded to our request. Consequently, 16 articles were excluded based on missing information on PTSS/PTSD prevalence.

Screening

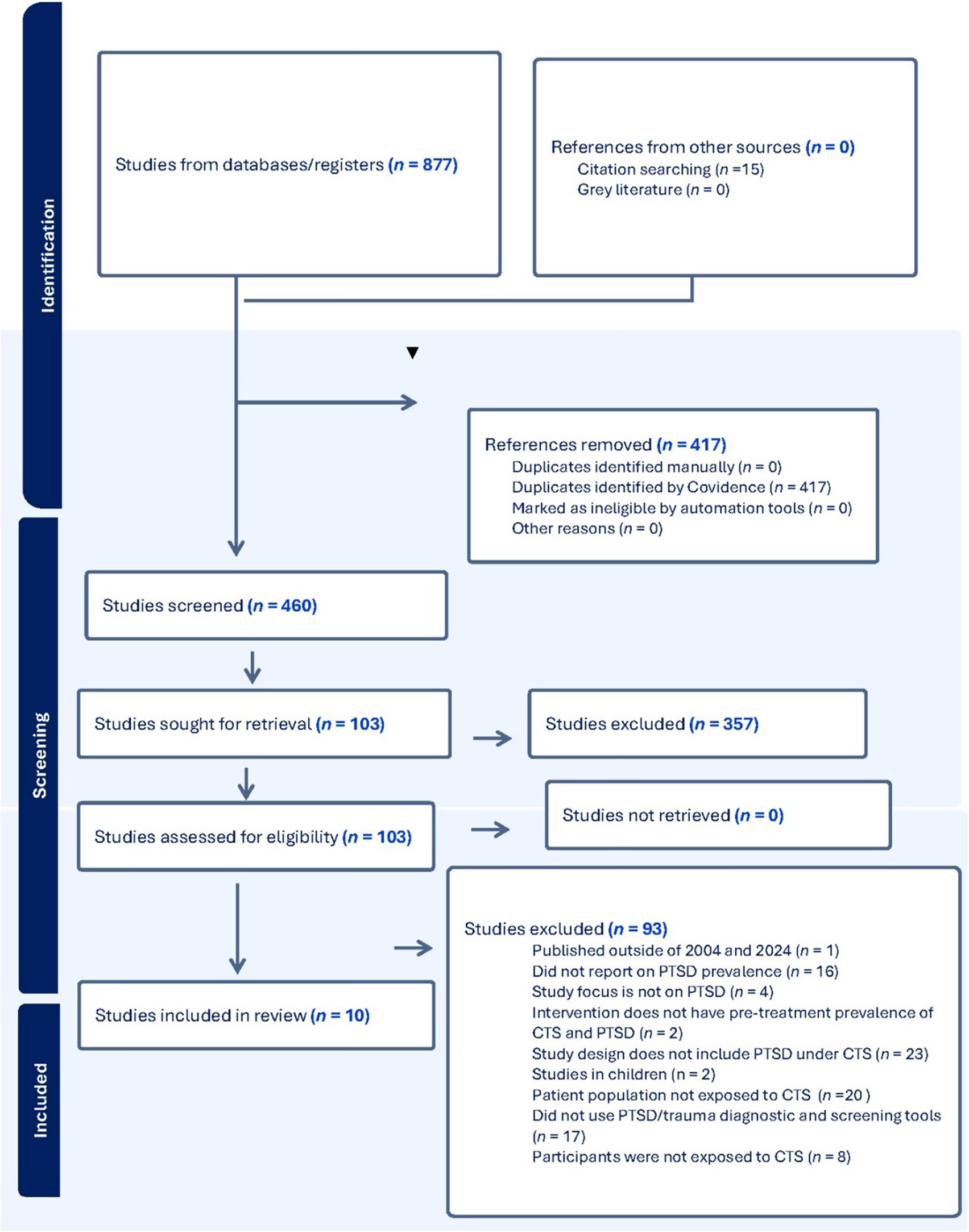

Screening and selection were conducted independently by two authors using Covidence (2024). Disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. Studies were searched and identified in multiple databases, followed by the removal of duplicates. Next, articles were screened for eligibility by their titles and abstracts. The final selection was made after full-text reviews. Ten articles were included in the SRMA. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram.

Data extraction

An Excel coding sheet was developed. The following data were extracted: (i) authors’ details and publication year; (ii) country; (iii) World Bank category; (iv) sample size; (v) number per sex; (vi) mean age; (vii) education level; (viii) recruitment method and (ix) study design. Additionally, we extracted data on (x) trauma (exposure measure, trauma load and trauma type); (xi) PTSS/PTSD (measure and prevalence); and (xii) the presence of comorbid depression, anxiety and/or substance-use disorder (including measure used). Risk of bias outcomes for each article were recorded.

Data analysis

A meta-analysis using R version 4.3 (the meta package) was conducted to estimate the prevalence of PTSS/PTSD amongst adolescents exposed to CTS using the metraprop function (R meta package). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic, with thresholds of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (Lin, Reference Lin2020). To address the bounded nature of proportions and stabilize variances, a logit transformation was applied. A random-effects model was employed using a generalized linear mixed-effects model with Hartung–Knapp adjustment for confidence intervals and prediction intervals.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for education level (no schooling, primary, secondary), World Bank income classification (low, lower-middle, upper-middle), type of PTSS/PTSD assessment (self-report vs. clinician-administered), and sample type (i.e., purposive vs random). Due to the limited number of studies, ‘no schooling’ and ‘primary’ education were grouped as a potential moderator (vs ‘secondary’ education). Accordingly, ‘lower-middle’ and ‘upper-middle’ income were grouped as a potential moderator (vs low income). Meta-regressions were performed to examine whether the proportion of female participants and mean age moderated PTSS/PTSD prevalence. Only studies with sufficient data were included in each subgroup analysis.

Lastly, data on comorbid depression, anxiety, and/or substance use were included as secondary outcomes. Information regarding these disorders was evaluated for all 10 studies and tabulated.

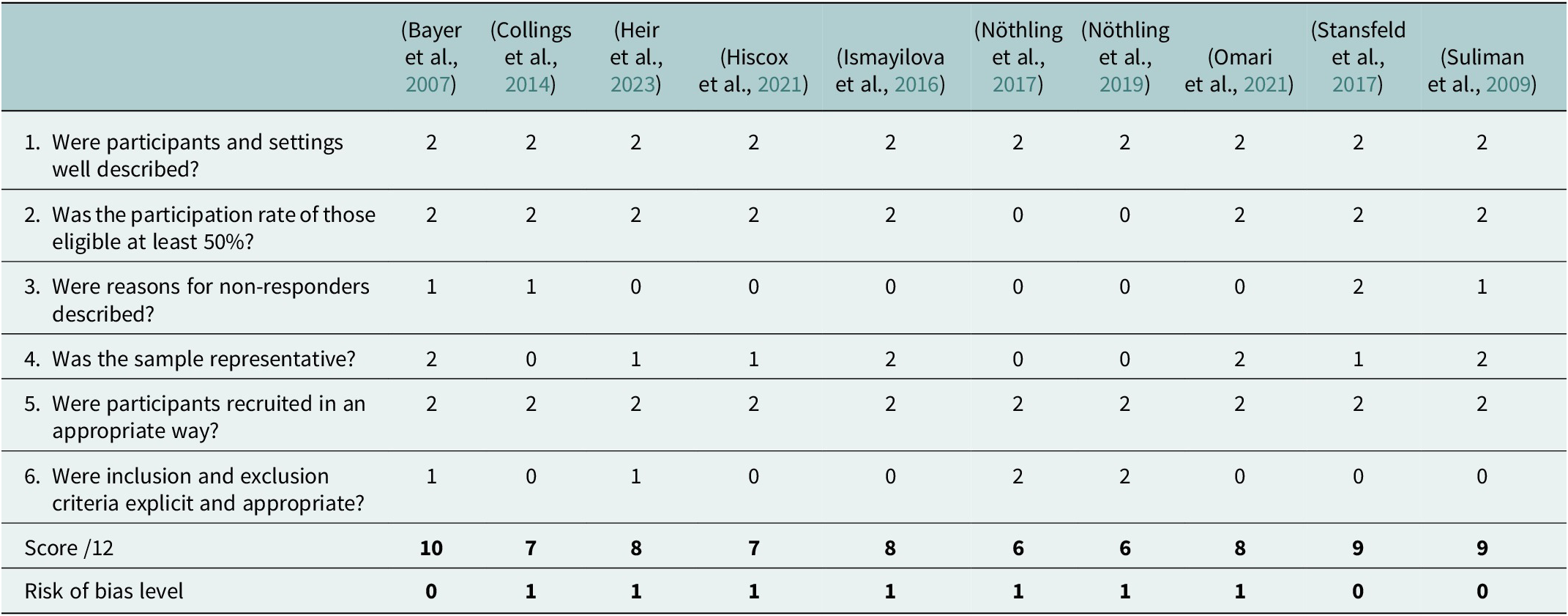

Risk of bias outcomes

Risk of bias was independently evaluated by two authors. Each study’s quality was assessed using the Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool (PACT) adapted by Woolgar et al. (Reference Woolgar, Garfield, Dalgleish and Meiser-Stedman2022) from the Joanna Briggs Institute (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Moola, Riitano and Lisy2014). The PACT includes six questions and assesses the description of the (i) participants and settings; (ii) participation rate of the eligible participants; (iii) reasons for non-response; (iv) quality and representativeness of the sample; (v) appropriateness of recruitment; and (vi) eligibility criteria. Each criterion was also rated on a three-point scale (high risk = 2, medium risk = 1, low risk = 0). The PACT provides a score out of 12. Inter-rater reliability at the item level was substantial (Kappa = 0.709, p < 0.001) and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Full ratings for each study are presented in Table 1. Total scores are categorized as low risk = 9-12, medium risk = 5-8, and high risk = 0-4 (Woolgar et al., Reference Woolgar, Garfield, Dalgleish and Meiser-Stedman2022). Three (30%) showed a low risk of bias, and seven (70%) showed a medium risk of bias.

Table 1. Risk of bias outcomes

Note: Each study was rated high (2), medium (1) or low (0) risk of bias on each criterion.

Results

Descriptive information

Socio-demographic data

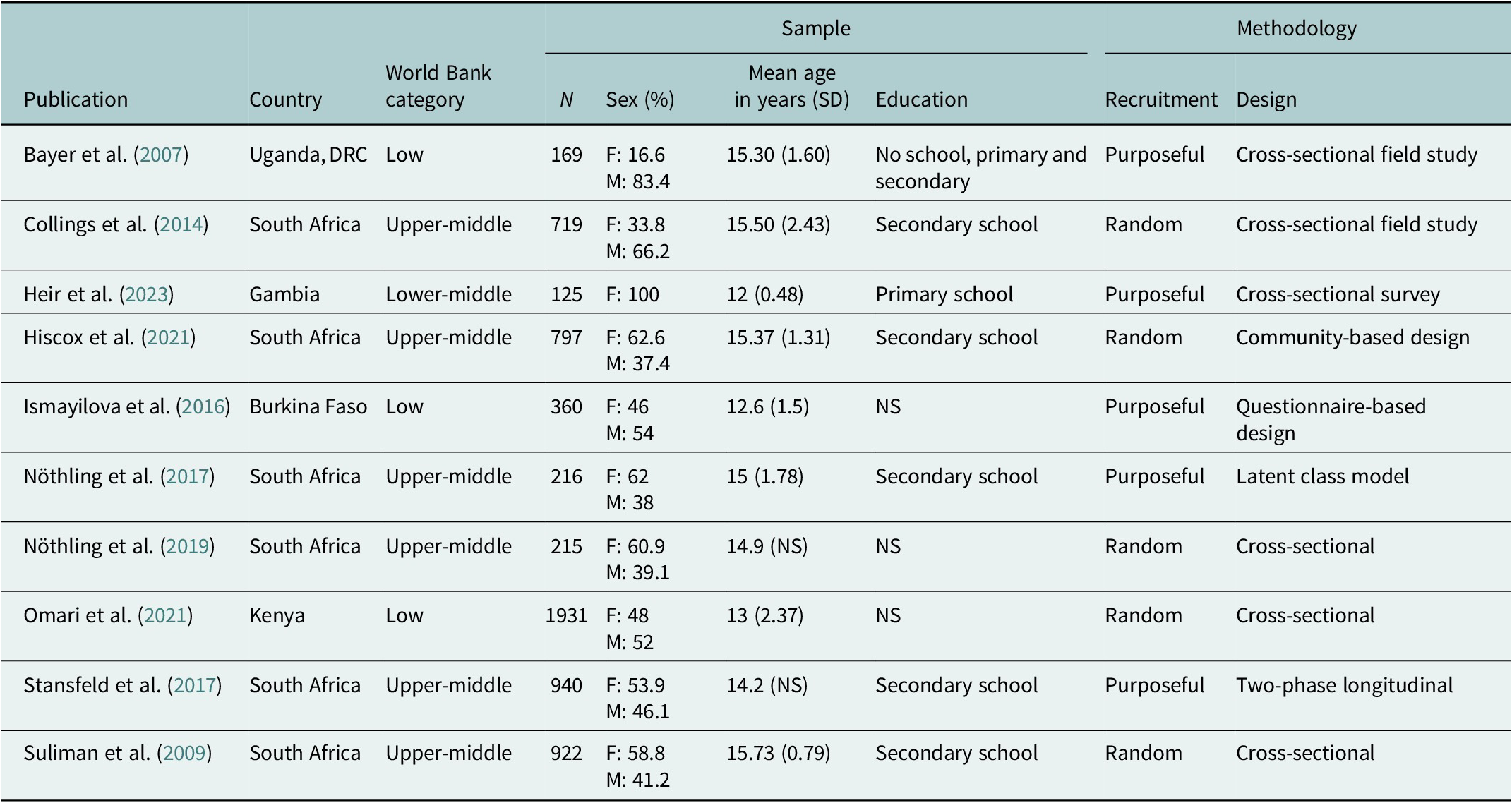

The 10 studies were published between 01 January 2007 and 30 August 2024 (see Table 2) and comprised a total of 6394 participants recruited via purposive (n = 5) (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007; Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Simmons, Suliman and Seedat2017; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017; Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023) or random (n = 5) (Fincham et al., Reference Fincham, Altes, Stein and Seedat2009; Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009; Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014; Okello et al., Reference Okello, De Schryver, Musisi, Broekaert and Derluyn2014; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Hiscox et al., Reference Hiscox, Hiller, Fraser, Rabie, Stewart, Seedat, Tomlinson and Halligan2021; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021) sampling. Overall, there were 3069 (48.97%) male participants and 3263 (51.03%) female participants, with one study only including female participants (Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023). Participants’ ages ranged between 10 and 20 years, and their education ranged from no schooling to primary and secondary education. Three studies did not specify the participants’ education level (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021).

Table 2. Descriptive data of the included studies’ country, World Bank category, sample, and methodology

Note: DRC = Democratic Republic of Congo, F = female, M = male, SD = standard deviation, NS = not specified.

Studies were conducted in low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries. Studies in low-income countries included Uganda (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007), the Democratic Republic of Congo (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007), Burkina Faso (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016), and Kenya (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021). One study was conducted in Gambia, a lower-middle-income country (Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023). South Africa was the only upper-middle-income country identified and accounted for six of the included studies (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009; Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Simmons, Suliman and Seedat2017, Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017; Hiscox et al., Reference Hiscox, Hiller, Fraser, Rabie, Stewart, Seedat, Tomlinson and Halligan2021).

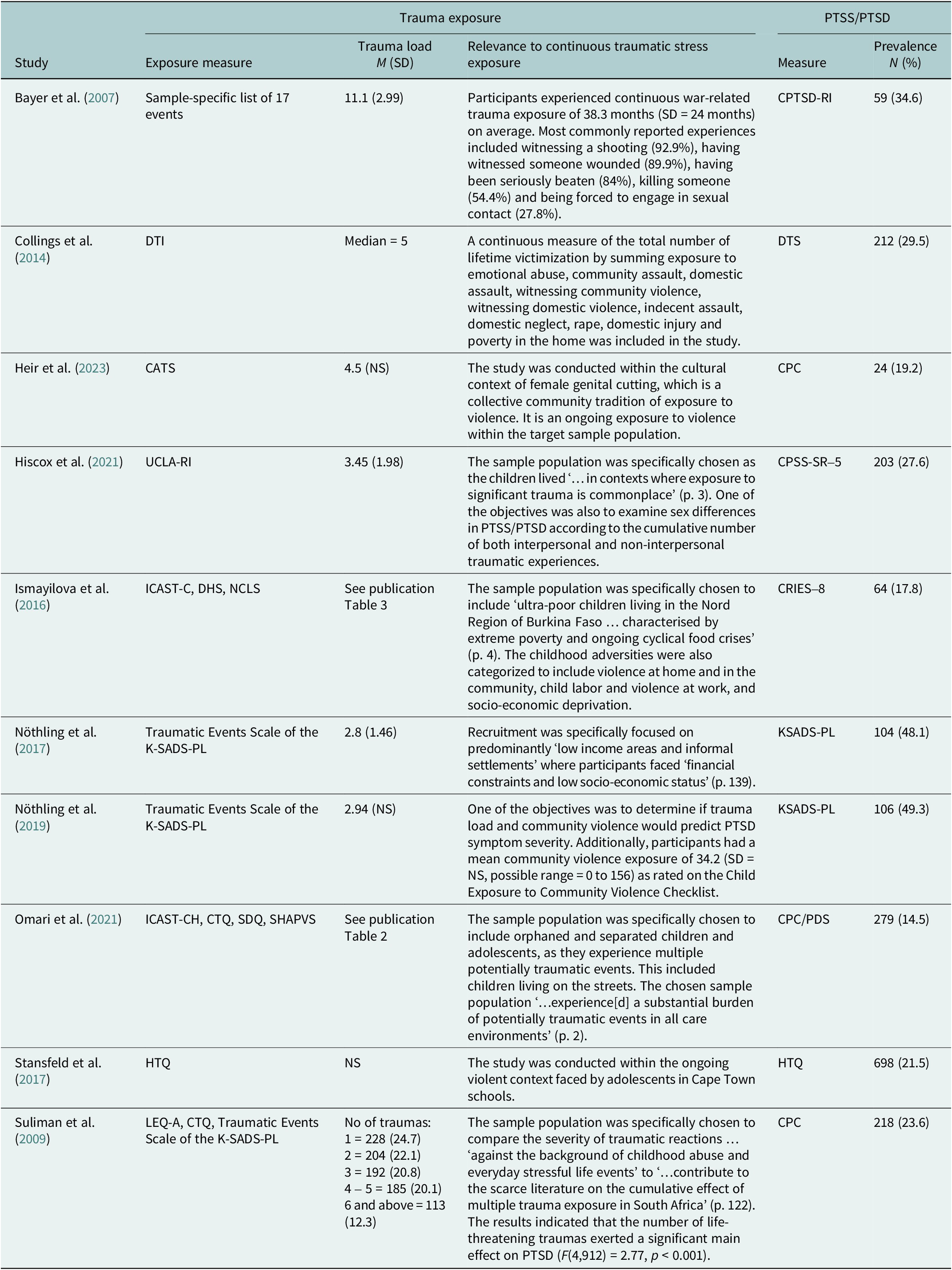

CTS exposure and PTSS/PTSD

All 10 studies reported on CTS exposure. Types of trauma exposure assessed mostly aligned with Criterion A for PTSD in the DSM. This is unsurprising given the type of trauma exposure measures used and the dominance of DSM-informed approaches in mental health research assessment (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Craddock, Cuthbert, Hyman, Lee and Ressler2013). Nonetheless, the studies also included traumatic events that do not necessarily align with Criterion A, including, for example, emotional abuse (Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021), domestic neglect (Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014), poverty (Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014; Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016), scary medical procedures (Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023), child labor (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016), being confronted with traumatic news (Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Simmons, Suliman and Seedat2017, Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019), bullying (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021), ‘other events’ (Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023), and cumulative trauma (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009).

PTSS/PTSD measures varied (see Table 3), with two studies using a diagnostic measure; the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version for DSM-5 (K-SADS-PL) (Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Simmons, Suliman and Seedat2017, Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019). Self-report measures included the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017), Child PTSD Reaction Index (CPTSD-RI) (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007), Davidson Trauma Scale (DTI) (Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014), Child PTSD Checklist (CPC) (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021; Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023), Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 (CPSS-SR-5) (Hiscox et al., Reference Hiscox, Hiller, Fraser, Rabie, Stewart, Seedat, Tomlinson and Halligan2021); and Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016). In addition to the CPC, Omari et al. (Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021) used the Post-traumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) to cover the different age groups.

Table 3. Descriptive data of the included studies’ trauma and PTSS/PTSD measures and prevalence

Note: NS = not specified. CATS = Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen; CDI-SF = Children Depression Inventory Short-Form; CPC = Child PTSD Checklist; CPSS-SR-5 = Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5; CPTSD-RI = Child PTSD Reaction Index; CRIES-8 = The Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale; CTQ = Child Trauma Questionnaire; DHS = Demographic and Health Survey (domestic violence items); DTI = Developmental Trauma Inventory; DTS =Davidson Trauma Scale; HTQ = The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; ICAST-CH = Child Abuse Screening Tool for Children at Home; KSADS-PL =Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version for DSM-5; LEQ-A = Life Events Questionnaire- Adolescent Version; NCLS = National Child Labor Surveys (child labour and abuse at work); PDS = Post-traumatic Diagnostic Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (bullying); SHAPVS = Social and Health Assessment Peer Victimization Scale (bullying item).

Prevalence of PTSS/PTSD of adolescents exposed to CTS

In the pooled sample of 6394 adolescents, the overall estimated PTSS/PTSD prevalence was 32.01% (95%CI: 20.68%–45.96%), with a wide prediction interval of 6.12%-77.29%. There was a high degree of heterogeneity (I 2 = 99.1%; p < 0.01). A forest plot of the individual and pooled prevalence estimates is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest Plot with PTSS/PTSD prevalence.

Moderators of PTSS/PTSD

Based on the subgroup analyses, World Bank Category (see Figure 3) significantly moderated PTSS/PTSD prevalence (Χ 2 = 3.83, df = 1, p = 0.05), with the South African studies (i.e., upper-middle income country) reporting a higher prevalence rate (21.0%) than low and lower-middle-income countries (38.0%). Further PTSS/PTSD measures (see Figure 4) significantly moderated PTSS/PTSD prevalence (Χ 2 = 7.93, df = 1, p < 0.01). Studies utilizing clinician-administered measures reported a higher PTSS/PTSD prevalence rate (49.0%) than studies using self-report measures (28.0%). Variability remained high, and caution should be used when interpreting the findings (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3. Forest Plot with PTSS/PTSD prevalence per World Bank Category.

Figure 4. Forest Plot with PTSS/PTSD prevalence per PTSS/PTSD measure used.

Sex/gender (F(1, 8) = 0.0792, p = 0.79), age (F(1, 8) = 1.6320, p = 0.24), education (Χ 2 = 1.49, df = 1, p = 0.22) and sample type (Χ 2 = 0.92, df = 1, p = 0.34) did not significantly moderate PTSS/PTSD prevalence (see Supplementary Figures A to D).

Trauma-related comorbidities

Seven studies reported on comorbid depression, anxiety, and/or substance-use behaviorsFootnote 1 (see Table 4). Five studies included measures of depression, with prevalence rates ranging from 14.5% (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021) to 41.2% (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017). While Suliman et al. (Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009) did not report a specific prevalence rate, the mean score of 11.51 (SD = 10.36) on the BDI is indicative of mild to moderate depression (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbauch2011). Three studies included measures of anxiety, with prevalence rates of 7.92% (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021), 15.6% (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017), and 61.3% (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009). Only one study included data on substance use, with prevalences of 19.6%, 8.0% and 16.8% for smoking cigarettes, smoking marijuana and alcohol use, respectively (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017).

Table 4. Descriptive data of the included studies’ comorbidity measures and prevalence

Note: NS = not specified. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CDI-SF = Children Depression Inventory Short-Form; CES-D-10 = Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; CES-DC-20 = Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children 20-items; KSADS-PL =Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version for DSM-5; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; NCLS = National Child Labor Surveys (child labour and abuse at work); PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; R-CMAS = Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale; SAS = Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.

Discussion

This SRMA on the prevalence of PTSS/PTSD highlights the exposure and response to CTS among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Study characteristics

Most of the included studies (60%) were conducted in South Africa, which indicates skewness toward a specific region. Since South Africa is also the only country among the included studies that is classified as upper middle-income, this may be indicative of the lack of resources/funding for important research throughout the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa. Obtaining research funding has become increasingly difficult and complex (Aagaard et al., Reference Aagaard, Mongeon, Ramos-Vielba and Thomas2021). Further, Ogega et al. (Reference Ogega, Majani, Hendricks, Adegun, Mbatudde, Muyanja, Atekyereza, Hugue and Gyasi2023) note that the ‘African research landscape faces a myriad of challenges which have resulted in a very unequal continent in terms of research and research capacity’ (p. 1). Considerable efforts must be made to ensure that poorer countries are not left behind when it comes to undertaking research in Sub-Saharan Africa. Only 30% of the studies had a low risk of bias, which may also be indicative of resource constraints that may compromise research rigor (Thelwall et al., Reference Thelwall, Simrick, Viney and Van Den Besselaar2023).

Prevalence of PTSS/PTSD of adolescents exposed to CTS

The pooled prevalence estimate for PTSS/PTSD was 32%, with a high degree of heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 99%; p < 0.01). This may be ascribed to the fact that the 10 studies used different PTSS/PTSD measures, potentially contributing to variability and heterogeneous outcomes (Murad et al., Reference Murad, Wang, Chu and Lin2019; Howes and Chapman, Reference Howes and Chapman2024).

Given the multitude of traumatic events that are present in countries with ongoing conflict and violence, the pooled PTSS/PTSD prevalence (32 %) among Sub-Saharan African adolescents is unsurprising. Whilst this prevalence rate is lower than that reported in Palestine (36%) (Agbaria et al., Reference Agbaria, Petzold, Deckert, Henschke, Veronese, Dambach, Jaenisch, Horstick and Winkler2021), it is much higher than that reported in Brazil (7.8%) (Avanci et al., Reference Avanci, Serpeloni, De Oliveira and De Assis2021). These findings highlight the importance of assessment beyond narrow DSM-5 criteria, where trauma exposure as a prerequisite for PTSD is considered as a past event. Clinicians and counselling services should assess for PTSS in adolescents exposed to CTS to allow for appropriate intervention.

Moderators of PTSS/PTSD

We explored moderators that contributed to the prevalence of PTSS/PTSD in adolescents exposed to CTS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Results indicated two independent moderators of PTSS/PTSD.

World Bank category

South Africa and Gambia (i.e., middle-income countries) (Collings et al., Reference Collings, Penning and Valjee2014; Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023) had a higher pooled prevalence of PTSS/PTSD (38.0%) than low/lower-middle income countries (21.0%). Notably, all middle-income studies were conducted in urban settings, whereas the low-income studies were conducted in rural villages (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016) and a random sample of households spread throughout a county (i.e., mixed area) (Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021). One low-income study was conducted among displaced child soldiers in an urban setting (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007). Urbanization has been associated with poorer mental health (Hepat et al., Reference Hepat, Khode and Chakole2024), including higher levels of PTSD (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Said Mohamed, Norris, Richter and Kuzawa2023a, Reference Kim, Tsai, Lowe, Stewart and Jung2023b), with high crime rates suggested as the causal link (Ventriglio et al., Reference Ventriglio, Torales, Castaldelli-Maia, De Berardis and Bhugra2021). Indeed, most studies were conducted in South Africa and of the countries included in this review, only the Democratic Republic of Congo (7.35) has a higher crime index compared to South Africa (7.18) (‘Ranking by Criminality’, 2023; Statista Research Department, 2024). Other than Kenya (7.08), the other countries included in the SRMA have lower levels of crime (i.e., Uganda = 6.55 and Burkina Faso = 5.92) (Statista Research Department, 2024).

Importantly, six of the seven studies conducted in middle-income countries were conducted in South Africa, and a sub-analysis indicated a significant difference in PTSS/PTSD prevalence between studies conducted in South Africa (41%) vs studies conducted in other countries (20%) (see Supplementary Figure E). As such, South Africa’s unique historical context (i.e., apartheid) should be considered when interpreting these findings. For example, research indicated that greater prenatal stress from apartheid predicted psychiatric comorbidities in adolescents aged 17 to 18 years (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Said Mohamed, Norris, Richter and Kuzawa2023a). Furthermore, apartheid continues to affect the children and grandchildren of those who lived during apartheid through secondary traumatization, socio-economic and material impact (which can, in turn, impact trauma exposure and mental health (Modise, Reference Modise2025)), and a sense of powerlessness and hopelessness (Adonis, Reference Adonis2016).

PTSS/PTSD measures

In 7 of the 10 studies, prevalence rates of PTSS/PTSD were based on self-report measures. The only two studies that used clinician-administered PTSD measures (Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Simmons, Suliman and Seedat2017, Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019) (which also reported higher PTSS/PTSD prevalence [49.0%] compared to self-report measures [28.0%])) were conducted in South Africa. PTSS severity assessed using clinician-administered versus self-report PTSS/PTSD measures have been shown to be discrepant (Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Whiteman, Petri, Spitzer and Weathers2023). While multimethod approaches for the assessment of PTSS/PTSD among youth, including parent and teacher reports, provide more comprehensive and less biased prevalence data of PTSS among adolescents (Hawkins and Radcliffe, Reference Hawkins and Radcliffe2006), there is some evidence that combining measures of PTSS/PTSD does not improve the prediction of a PTSD diagnosis (You et al., Reference You, Youngstrom, Feeny, Youngstrom and Findling2017). Furthermore, using checklists as the source of identifying index traumatic events (as was done in most of the studies included in this systematic review) might miss cases with PTSS/PTSD.

Five studies specifically noted that they translated questionnaires into the local languages (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Klasen and Adam2007; Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Hiscox et al., Reference Hiscox, Hiller, Fraser, Rabie, Stewart, Seedat, Tomlinson and Halligan2021), while Heir et al. (Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023) administered questionnaires in English but had translators to assist when there were any ambiguities or inquiries. Similarly, only one study specified that they culturally adapted assessments (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017). Kaiser et al. (Reference Kaiser, Ticao, Anoje, Minto, Boglosa and Kohrt2019) noted that adolescents use a variety of slang/colloquial phrases relevant to their context and culture. Thus, accurate translation of measures into local languages, as well as considering colloquial language used by adolescents, is important (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Ticao, Anoje, Minto, Boglosa and Kohrt2019). Worldwide, mental health assessment tools lack cultural relevance and sensitivity (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Ticao, Anoje, Minto, Boglosa and Kohrt2019). Africa is a diverse continent with many different cultures. There is a need for transcultural and linguistic adaptation (Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Sivathasan, Yoon, Da Silva and Ravindran2018). For example, Kaiser et al. (Reference Kaiser, Ticao, Anoje, Minto, Boglosa and Kohrt2019) conducted a study using a mixed-method approach to culturally adapt the Depression Self-Rating Scale, Child PTSD Symptom Scale, and Disruptive Behaviour Disorders Rating Scale in Nigeria. Adolescents reported that some of the items were difficult to conceptualize, some were not equivalent across languages, and others were considered stigmatizing (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Ticao, Anoje, Minto, Boglosa and Kohrt2019). Further, while some of the PTSS/PTSD measures used in the included studies, such as the CPSS (Burundi), the HTQ (South Africa), the PDS (South Africa) (see Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Devadas, Ardman, Levis, Go and Gaynes2020 for systematic review) were validated within the African context, the use of Western-developed measures in the sub-Saharan context may still impact findings. Considering the above, it is plausible that some tools may not have been easily understood by adolescents, contributing to the variation in PTSS/PTSD prevalence and underscoring the need for continued development of contextually and culturally relevant measures.

Trauma-related comorbidity

Six studies assessed comorbid depression (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009; Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Gaveras, Blum, Tô-Camier and Nanema2016; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017; Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Hiscox et al., Reference Hiscox, Hiller, Fraser, Rabie, Stewart, Seedat, Tomlinson and Halligan2021; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021), three studies assessed anxiety (Suliman et al., Reference Suliman, Mkabile, Fincham, Ahmed, Stein and Seedat2009; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017; Omari et al., Reference Omari, Chrysanthopoulou, Embleton, Atwoli, Ayuku, Sang and Braitstein2021), and one study assessed comorbid substance use (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Rothon, Das-Munshi, Mathews, Adams, Clark and Lund2017). Prevalence rates of depression (14.5%-41.2%) and anxiety (7.92%-61.3%) differed across studies, which may be accounted for, in part, by the use of different measures (Schou Pedersen et al., Reference Schou Pedersen, Sparle Christensen and Prior2023) and other methodological differences. Nonetheless, prior studies have documented high rates of depression (Mngoma et al., Reference Mngoma, Ayonrinde, Fergus, Jeeves and Jolly2021), anxiety (Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Sivathasan, Yoon, Da Silva and Ravindran2018), and substance use (Ebrahim et al., Reference Ebrahim, Adams and Demant2024) among adolescents living in stressful conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is important for health care providers to assess for comorbidity among adolescents exposed to CTS.

Importantly, distinct clusters of psychiatric symptoms linked to PTSS/PTSD may be differentiated by different types of trauma in adolescents (Giourou et al., Reference Giourou, Skokou, Andrew, Alexopoulou, Gourzis and Jelastopulu2018; Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Sivathasan, Yoon, Da Silva and Ravindran2018; Goral et al., Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021). For example, child sexual abuse or emotional abuse has been linked with the cluster of exhaustion/emotional detachment (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Seng, Briggs, Munro-Kramer, Graham-Bermann, Lee and Ford2017), while physical neglect or parental death has been linked to the cluster of fear/helplessness (Kline et al., Reference Kline, Millman, Denenny, Wilson, Thompson, Demro, Connors, Bussell, Reeves and Schiffman2016). Furthermore, many adolescents with PTSS/PTSD have a history of multiple and ongoing trauma, with multimorbidity (Lansing et al., Reference Lansing, Virk, Notestine, Plante and Fennema-Notestine2016), including depressive symptoms (Hankerson et al., Reference Hankerson, Moise, Wilson, Waller, Arnold, Duarte, Lugo-Candelas, Weissman, Wainberg, Yehuda and Shim2022), anxiety-related symptoms (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Antl and McAuley2022), and substance use behaviors (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Dodd, Taylor, Stewart, Yang, Shahidullah, Guzick, Richmond, Aksan, Rathouz, Rousseau, Newport, Wagner and Nemeroff2023). Comprehensive screening for common mental disorders in adolescents living in conditions of CTS is key.

Implications

During adolescence, there is continued brain development, especially in areas associated with higher cognitive and emotional functioning (Hochberg and Konner, Reference Hochberg and Konner2020). There is a dynamic reorganization of neural circuitry and connectivity during adolescence related to emotion reactivity and regulation (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Heller, Gee and Cohen2019). This includes areas such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. These regions are associated with the fear-based limbic system that is activated during times of distress (Henigsberg et al., Reference Henigsberg, Kalember, Petrović and Šečić2019; Iqbal et al., Reference Iqbal, Huang, Xue, Yang and Jia2023), such as CTS exposure. As such, CTS exposure may negatively impact adolescents’ cognitive and emotional development. For example, Ainamani et al. (Reference Ainamani, Rukundo, Gumisiriza, Tumwine and Hall2024) found that PTSS severity decreased adolescents’ willingness to forgive and heightened their desire for revenge, highlighting how exposure to continuous traumatic events may leave youth traumatized and wanting to perpetuate violence as a form of vengeance. Early intervention is important to mitigate the long-term effects of CTS, to deter the cycle of violence.

Notably, none of the included studies explored CTS response as distinctly different from PTSS/PTSD. However, Ainamani et al. (Reference Ainamani, Rukundo, Gumisiriza, Tumwine and Hall2024) also highlighted the importance of expanding research on CTS response as a separate construct from PTSS. Adolescents’ unwillingness to forgive and their heightened desire for revenge following CTS exposure is more aligned with the CTS response of rage, betrayal, and detachment as measured by the CTS-RS (Goral et al., Reference Goral, Feder-Bubis, Lahad, Galea, O’Rourke and Aharonson-Daniel2021; Leshem et al., Reference Leshem, Kashy-Rosenbaum, Schiff, Benbenishty and Pat-Horenczyk2023). To date, most research on CTS response has focused on PTSS/PTSD as an outcome, rather than as a separate construct. This lack of research is likely influenced by the fact that only one CTS response measure (the CTS-RS) is currently available (Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Goral, Fedotova, Akimova and Martyniuk2024). While the measure has been validated, factor analyses have found differences between Israeli and Ukrainian samples (Zasiekina et al., Reference Zasiekina, Goral, Fedotova, Akimova and Martyniuk2024). To our knowledge, no validation studies of the CTS-RS have been conducted in a Sub-Saharan African context. Further research is needed to not only measure CTS response as a distinct construct among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa, using the CTS-RS but also to determine its validity, reliability, and cultural relevance. Such studies will assist in a better understanding of the psychosocial impact of CTS exposure on adolescents and inform future intervention development.

Limitations and future recommendations

This SRMA covered a small number of studies, with most from a single country (South Africa). Given South Africa’s unique historical history (i.e., apartheid) and its ongoing aftermath (Adonis, Reference Adonis2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Said Mohamed, Norris, Richter and Kuzawa2023a; Modise, Reference Modise2025), as well as being the only upper-middle-income country included in the SRMA, findings are not generalizable to the whole continent.

The review only included articles published in English. Considering the many other languages spoken in Sub-Saharan African countries (e.g., Portuguese, French, etc.), it is possible that articles published in these languages were excluded. Our results are, for example, not representative of countries like Mozambique and Cameroon, where Portuguese and/or French are predominantly spoken. Future studies should include literature published in other languages.

While our analysis indicated that age did not moderate the prevalence of PTSS/PTSD, the included age range (10–24 years) does span distinctly different developmental periods, which include early adolescents, middle adolescents, and young adulthood (Backes and Bonnie, Reference Backes and Bonnie2019), subgroup analysis comparing early adolescents (10–14 years), middle adolescents (15–19 years), and emerging adults (20–24 years) was not feasible due to limited sample sizes across the studies. Consequently, we were unable to explore potential age-related variability in prevalence. This is an important limitation, as the developmental stage may shape both exposure patterns and responses to trauma. Future research with larger, age-stratified samples should examine these developmental subgroups to provide more nuanced insights.

For the most part, trauma types were broadly defined (e.g., ‘childhood trauma’; ‘community violence’), despite the nuanced nature of trauma (Nöthling et al., Reference Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons and Seedat2019; Heir et al., Reference Heir, Bendiksen, Minteh, Kuye and Lien2023), and we were unable to analyze trauma type as a potential moderator.

The use of purposive sampling in 50% of the studies may influence the generalizability of the pooled prevalence estimates. Additionally, this precludes us from determining population-level prevalence estimates as purposive samples are not drawn randomly from a defined population and may not reflect the true distribution of PTSS/PTSD. Thus, these prevalence estimate reflects sampled groups, not populations.

Despite efforts to retrieve the necessary data, sixteen studies were excluded because they did not report PTSS/PTSD prevalence data. Thus, we cannot purport that the included studies are representative of similar studies within Sub-Saharan Africa. Future research should consider accessing individual case-level data and utilizing statistical methods to account for missing data.

Lastly, extreme heterogeneity (I2 = 99%) remains a concern. While the moderation analyses included in the study serve to shed some light on what may cause the heterogeneity, many other factors not included in this SRMA could mediate or moderate the development of PTSS/PTSD among adolescents. For example, studies have found a strong association between PTSD and social support (Elklit, Reference Elklit2002; Ekşi et al., Reference Ekşi, Braun, Ertem-Vehid, Peykerli, Saydam, Toparlak and Alyanak2007). Social support is a mediator of the relationship between trauma and adolescents further engaging in risky behaviors (Nooner et al., Reference Nooner, Linares, Batinjane, Kramer, Silva and Cloitre2012). These factors were not considered in our analysis. Future studies should consider including a wider array of factors.

Conclusion

The prevalence of PTSS/PTSD (32.0%) among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa is high. Intensive exploration of CTS exposure and response in adolescent populations in Sub-Saharan Africa, covering a wider geography, is warranted to determine the burden and care needs. Trauma-informed care, psychosocial support, and prevention and early intervention strategies are essential components of public mental health interventions for adolescents living in environments characterized by CTS exposure.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10129.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10129.

Data availability statement

Parties should contact the corresponding authors of the included articles to request data.

Author contribution

All the authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study and contributed significantly to writing the manuscript. OS and YR conducted the literature search, article selection and data extraction. AvdW cross-checked the data extraction. AvdW and MACR equally contributed to writing the first full draft.

Financial support

We thank our funders, Alborada Fund, Cambridge-Africa, for making this project possible. We also thank Dr Simonne Wright for her assistance with the data analysis. This work is supported by the South African PTSD Research Programme of Excellence and the South African Medical Research Council/Stellenbosch University Genomics of Brain Disorders Research Unit.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments

Hereby, we submit our research article to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. Our article on Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adolescents Exposed to Continuous Traumatic Stress in Sub-Saharan Africa is a systematic review and meta-analysis of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among adolescents (aged 10 to 24 years) in Sub-Saharan Africa.

There is a lack of published prevalence data on PTSS and PTSD in adolescents aged 10 to 24 years in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region often plagued by continuous wars, armed conflict, and traumatic stress. Given the potential negative impact of continuous traumatic stress (CTS) exposure on adolescents’ developmental trajectories, we aimed to fill this gap. Further, we highlight predictors of PTSS and PTSD in adolescents exposed to CTS.

Finally, we highlight an important debate in the context of the current definitions of trauma and PTSD in the DSM-5; as well as the importance of developing culturally appropriate measures to determine CTS responses which are not fully captured within the PTSD symptomatology criteria.

We declare that we have no competing interests. This article was not submitted to any other journal. We look forward to a favourable response.

Yours faithfully

Berte