1 Overview

Motivation for this Element

Informal Digital Learning of English (IDLE) refers to how learners autonomously engage with English across digital spaces, outside of the traditional classroom (Lee, Reference Lee2022a). Coincidentally, the term “IDLE” sounds like aideul, the Korean word for “children,” which captures the spirit of how young learners naturally acquire language – through curiosity, creativity, and playful experimentation in online environments. My own journey with English began in much this way. As a seventh grader, I fell in love with “real” English through music, movies, and sports. By high school, I found myself shedding my anxiety and imagining life in English-speaking settings. In my twenties, IDLE gave me the skills and confidence to explore more than ten different countries, whether studying, backpacking, volunteering, or working abroad.

Seeing the potential of IDLE to spark motivation and growth, I introduced these strategies to my Korean students in my early thirties. Yet, weaving IDLE into classroom life was far from simple. Many students, parents, colleagues, and senior teachers hesitated, their uncertainty rooted in Korea’s strong group-oriented culture and intense focus on exams – especially at my school, where such societal pressures ran deep (Lee, Reference Lee, Dressman and Sadler2020a; Zadorozhnyy et al., Reference Zadorozhnyy, Lai and Lee2025). My perspective widened further when, after four years of teaching in Korea, I encountered Moroccan learners who spoke English with remarkable fluency and confidence – thanks to IDLE (Dressman & Lee, Reference Dressman and Lee2021). Through interviews, observations, and consultations, I witnessed firsthand how powerfully IDLE could shape English learning and use beyond traditional classrooms (Lee & Dressman, Reference Lee and Dressman2018).

Today, IDLE has become a global phenomenon, fueled by affordable smartphones and the widespread reach of platforms, such as Meta (formerly Facebook), Instagram, YouTube, and Netflix (Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023; Soyoof et al., Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Vazquez-Calvo and McLay2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Soyoof, Lee and Zhang2025). This Element explores how changing global trends and rapid technological advancements have made IDLE possible, how it supports language learning, and how partnerships are helping to weave it into schools and communities.

Background and Context

In our rapidly changing, interconnected world, English has become a vital tool for global communication (Graddol, Reference Graddol2006; Crystal, Reference Crystal2010). It brings together people from diverse cultures, fosters international collaboration, and opens doors to global conversations (Warschauer, Reference Warschauer2000; Friedman, Reference Friedman2005). Recent technological breakthroughs – especially in generative Artificial Intelligence – are revolutionizing English learning, making it more accessible, affordable, and adaptable to every learner’s needs (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2022; Liu et al., Reference 69Liu, Darvin and Ma2024a; Lai & Sundqvist, Reference Lai and Sundqvist2025).

Digital platforms now offer learners vivid, authentic English experiences (Liu & Darvin, Reference Liu and Darvin2023). Interactive apps and vast online courses, alongside dynamic social media, allow users to practice English in real time – participating in discussions, sharing interests, and immersing themselves in multimedia content (Lee, Y.-J., Reference Lee2023). Apps, such as Babbel and Duolingo, use AI to personalize lessons, while communities on Twitter and Reddit let learners converse with people around the world about topics they care about (Chik & Ho, Reference Chik and Ho2017; Isbell, Reference Isbell2018; Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2021; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Jiang and Peters2024).

Within this dynamic landscape, more and more language learners are turning to informal digital methods to strengthen their English (Sockett, Reference Sockett2014; Richards, Reference Richards2015; Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016; Toffoli, Reference Toffoli2020; Toffoli et al., Reference Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023). IDLE marks a shift from traditional, classroom-based learning to a more self-directed, technology-driven approach (Lee, Reference Lee2022a; Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023). Learners take charge, exploring a wealth of online resources – YouTube tutorials, podcasts, language exchanges – at their own pace and according to their unique interests (Rezai & Goodarzi, Reference Rezai and Goodarzi2025).

Similar concepts, such as Extramural English (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009; Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016) and Online Informal Learning of English (Sockett, Reference Sockett2014; Toffoli & Sockett, Reference Toffoli and Sockett2015), highlight this evolving landscape. Researchers are uncovering how activities such as gaming, social media engagement, and digital content creation effectively support language learning well beyond the classroom (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009, Reference Sundqvist2019, Reference Sundqvist, Ziegler and González-Lloret2022, Reference Sundqvist2024; Chik, Reference Chik2014; Sockett, Reference Sockett2014; Lai, Reference 65Lai2017; Dressman & Sadler, Reference Dressman and Sadler2020; Reinders et al., Reference Reinders, Lai and Sundqvist2022; Toffoli et al., Reference Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses synthesize these findings, offering a broad view of IDLE’s influence (Dizon, Reference Dizon2023; Guo & Lee, Reference Guo and Lee2023; Soyoof et al., Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Vazquez-Calvo and McLay2023; Guan et al., Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024; Aiju et al., Reference Aiju, Abdullah and Yufeng2025; Dressman et al., Reference Dressman, Toffoli and Lee2025; Kusyk et al., Reference Kusyk, Arndt, Schwarz, Yibokou, Dressman, Sockett and Toffoli2025). Special journal issues and dedicated symposia further spotlight the latest research and foster a vibrant community of scholars and practitioners (Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2017; Arndt & Lyrigkou, Reference Arndt and Lyrigkou2019; Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019; Reynolds & Teng, Reference Reynolds and Teng2021; Lee & Chik, Reference Lee and Chik2025; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Liu and Soyoof2026).

As research increasingly highlights IDLE’s positive effects (e.g., improved proficiency and motivation), researchers are also uncovering the factors that drive learners to embrace these practices (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024; Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2024; see Section 3). Understanding what motivates learners and how they interact with technology enables educators to design IDLE activities that blend smoothly with formal curricula (Melnyk & Morrison-Beedy, Reference Melnyk and Morrison-Beedy2012; Lai & Lee, Reference Lai and Lee2024; Lee & Chik, Reference Lee and Chik2025). By aligning IDLE with educational goals, teachers can make learning more engaging, effective, and expansive (Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023; Lee, Reference Lee2024).

Recently, IDLE has moved from theory to practice; it is now used in classrooms, built into curricula, embedded in AI-powered language apps, and woven into community projects (Dressman & Lee, Reference Dressman and Lee2021; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025). These initiatives thrive on transdisciplinary collaboration, connecting experts in education, technology, linguistics, psychology, and sociology (Melnyk & Morrison-Beedy, Reference Melnyk and Morrison-Beedy2012; Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Granfeldt and Gullberg2022; Lee, Reference Lee2024). For example, partnerships between researchers and industry have produced AI-mediated IDLE programs that personalize learning beyond the classroom (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025). In line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 (lifelong learning), community projects are also using informal strategies to support language learning among marginalized and under-resourced groups, helping them adapt and thrive in new societies (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist, Ziegler and González-Lloret2022; Reinders and Lee, Reference Reinders and Lee2023; Lee, Reference Lee2024; see Section 4).

As the field of IDLE continues to expand, this Element looks to the future (see Section 5). Our aim is to explore how IDLE can further enrich language learning – by including more diverse learners and contexts, extending IDLE to languages beyond English, deepening research with new theories and tools, and refining methods to strengthen evidence. Ultimately, we hope to help educators and communities integrate IDLE meaningfully, maximizing its benefits for learners everywhere (Dizon, Reference Dizon2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024).

1.1 The Aim and Structure of This Element

This Element unfolds across five sections, each designed to guide readers through the evolving landscape of IDLE:

Section 1: Overview

The opening section lays the foundation for the entire volume. It delves into the motivation behind the Element, provides essential background, and sets the stage for what follows. Readers will find a clear outline of the Element’s overall aims, along with a roadmap previewing Sections 2 through 5.

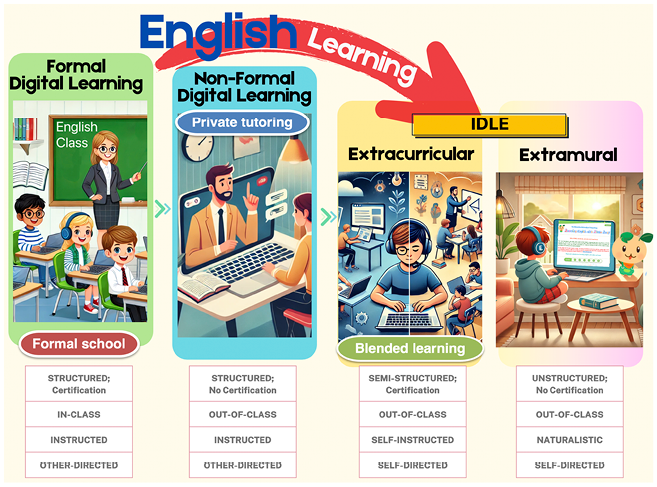

Section 2: IDLE

This section places IDLE within the sweeping changes brought about by globalization and technological advances from the 1990s to the 2020s. It discusses why IDLE is so relevant today, introducing four core principles – formality, location, pedagogy, and locus of control – that define its character. Further, the section breaks down IDLE into four distinct learning spaces, forming the backbone of the IDLE Continuum Model, a practical framework for teachers aiming to bring IDLE into formal classrooms. The discussion also contrasts IDLE with traditional English education and examines related concepts, such as Extramural English and Online Informal Learning of English. In addition, the section reviews key literature and recent trends, offering a holistic and up-to-date understanding of IDLE’s rapid expansion (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009; Sockett, Reference Sockett2014; Toffoli & Sockett, Reference Toffoli and Sockett2015; Lee, Reference Lee2022a).

Section 3: Antecedents and Consequences of IDLE

Drawing on a wide array of empirical research, this section maps out both the precursors and outcomes of IDLE engagement. A comprehensive visual model illustrates these relationships, providing researchers and educators with a clear picture of what is already known about IDLE – and what remains to be explored. This section also serves as a practical guide, enabling the design of evidence-based IDLE interventions tailored to the needs of specific schools or communities.

Section 4: Bringing IDLE into Schools and Communities

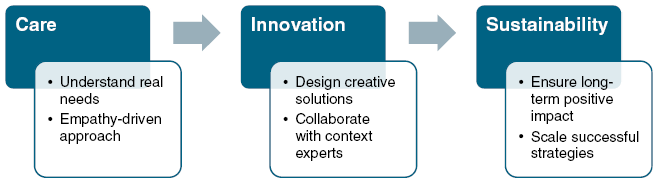

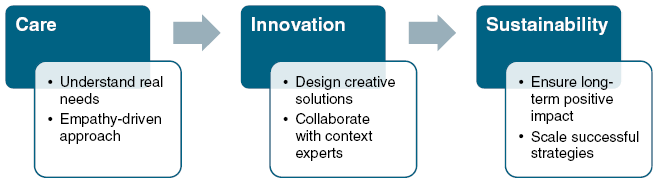

As the evidence base for IDLE grows, so too does the call to embed it in formal education. This section begins with a candid look at the challenges faced in integrating IDLE into school systems in places such as Hong Kong and Indonesia. It introduces the IDLE Continuum Model, which gives educators at every level – K-12 and higher education – a flexible framework for blending IDLE into their curricula, supported by conceptual, empirical, and experimental research. Practical pedagogical strategies are discussed, showing how educators can transition smoothly across different modes of digital learning: from formal and non-formal settings to extracurricular and extramural experiences. The vital role of teachers – as context experts who understand both research and the unique needs of their students and institutions – is underscored. In alignment with the Research Excellence Framework’s emphasis on social impact, the section highlights how IDLE initiatives have reached beyond academia into communities, engaging stakeholders such as teachers, NGOs, government officials, and industry partners. It also introduces the “Care–Innovation–Sustainability Model” and illustrates how multidisciplinary teams have applied this model to IDLE implementation in Indonesian schools and communities.

Section 5: Future Directions for IDLE

Building on the cutting-edge research presented in Sections 1–4, the final section looks ahead to the future of IDLE. It charts pathways for expanding IDLE to more diverse learners and contexts – including young students and those in the Global South – and for embracing Languages Other Than English (LOTE), such as Korean and Chinese. The section explores how IDLE can be deepened by drawing on various theoretical frameworks, including ecological systems theory and the technology acceptance model. It encourages methodological innovation, whether through digital learner analytics or by adopting research approaches from other disciplines, such as experience sampling methods (ESM). Innovative strategies for integrating IDLE into schools are discussed, always with an eye on local contexts. Finally, the section advocates for IDLE as a tool for broader social impact, aiming to reach more learners and communities in alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals – particularly SDG 3 (health and well-being) and SDG 4 (quality education).

2 Informal Digital Learning of English

2.1 The Rise of Digital Technology and English Learning

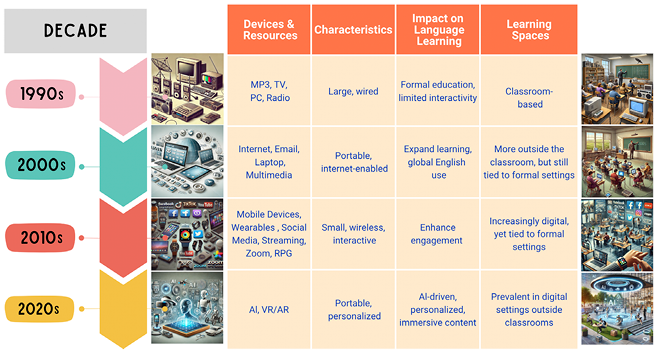

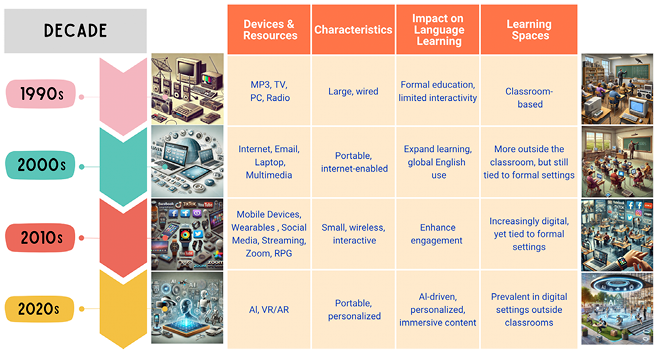

What might be contributing to the global surge in IDLE among young English learners (Guo & Lee, Reference Guo and Lee2023; Guan et al., Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024)? A key factor appears to be the ongoing progression of digital innovation and the increasing accessibility of advanced technologies (Soyoof et al., Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Vazquez-Calvo and McLay2023). Over time, technological developments have likely reshaped how learners engage with English, as illustrated in Figure 1. Drawing on research that traces the evolution of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL; Warschauer, Reference Warschauer, Fotos and Brown2004; Chun, Reference Chun2016, Reference Chun2019; Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019; Lee, Reference Lee2022a), this section outlines a tentative timeline of digital shifts and their potential influence on English learning, suggesting that technology has, in many cases, extended language learning beyond the traditional classroom. Since the 1990s, each decade seems to have introduced notable changes in language acquisition, gradually lowering barriers and expanding possibilities.

Figure 1 Digital Technology and English Learning: A Chronological Evolution

The 1990s: Wired and Walled in

In the 1990s, learning was often tied to bulky, wired devices – MP3 players, satellite TV boxes, and desktop computers – primarily available in wealthier, developed regions (Stockwell, Reference Stockwell2008). English instruction largely remained within conventional classrooms, shaped by fixed curricula and limited digital tools. Authentic English content – such as podcasts, films, or global media – was not widely accessible outside school, meaning students typically depended on textbooks and teacher guidance (Kim, Reference Kim2015).

The 2000s: Portability and Early Connections

With the turn of the millennium came a wave of educational change. Portable devices such as laptops and early tablets began to loosen the spatial constraints of learning (Kim, Reference Kim2015). The internet and email introduced learners to a broader array of English-language materials and intercultural interactions (Nah et al., Reference Nah, White and Sussex2008). Still, access to these tools was uneven. While some households in affluent areas such as northern Europe came online, the benefits were often limited to those with sufficient resources, reinforcing existing digital divides (McCallum & Tafazoli, Reference McCallum and Tafazoli2024).

The 2010s: On-the-Go Learning and Creative Autonomy

The 2010s marked the proliferation of smartphones, smartwatches, and social media platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, which arguably reduced the constraints of time and place (Chik & Ho, Reference Chik and Ho2017; Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2021). Lightweight, wireless devices enabled learners to turn idle moments – on public transport, in cafés, or at the gym – into potential learning opportunities (Reinders & Benson, Reference Reinders and Benson2017). Learners increasingly moved beyond passive consumption, producing their own content – memes, vlogs, and tutorials – aligned with their interests (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2016; Chen, Reference Chen2020). This period may have fostered greater learner agency, allowing individuals to shape their English learning paths outside traditional publishing structures (Benson, Reference Benson2011a, Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011b).

The 2020s: Immersive and Personalized Experiences

Emerging technologies such as AI, VR, and AR are once again reshaping the landscape of language learning (Lin & Lan, Reference Lin and Lan2015; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., Reference Kaplan-Rakowski, Lin and Wojdynski2021). Generative AI can offer lessons tailored to individual learner profiles, while VR and AR simulate immersive English-speaking environments – virtual cafés, international conferences, or bustling cityscapes (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2022; Stockwell & Wang, Reference Stockwell and Wang2025). Increasingly affordable and multifunctional devices may be helping to bridge geographic gaps, enabling real-time collaboration across borders (Dooly & Sadler, Reference Dooly and Sadler2013; Lee & Song, Reference Lee and Song2020). These tools appear to blur the line between formal instruction and informal exploration, potentially supporting fluency through experiential learning (Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023).

IDLE’s Bright Future: Learners in Control

This ongoing technological evolution seems to be positioning IDLE as a prominent mode of English learning. As digital tools become more adaptive, accessible, and embedded in daily life, learners may be gaining more autonomy over their language development (Lai, Reference 65Lai2017; Jeon, Reference Jeon2022; Lai & Lee, Reference Lai and Lee2024). IDLE offers alternatives to rigid curricula, suggesting more flexible and personalized pathways to proficiency in a world where English increasingly mediates global communication (Benson, Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011b; Reinders & Benson, Reference Reinders and Benson2017; Lee, Reference Lee2022a). Nonetheless, digital inequality continues to constrain access for some. The future of language learning may well unfold not only in classrooms but also across the expansive, digitally connected environments that many learners now navigate daily (Warschauer, Reference Warschauer2000; UNICEF, 2020; Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist, Ziegler and González-Lloret2022; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025).

2.2 From Classrooms to IDLE: Redefining Language Learning Spaces

For decades, second language acquisition research focused on what happens inside learners’ minds – memory capacity, motivation levels, innate aptitude (Papi & Hiver, Reference Papi and Hiver2025). But this cognitive approach overlooked a crucial element: the real-world actions learners take to master a language. “Proactive Language Learning Theory” changes the game by spotlighting four key behaviors that drive success (Papi & Hiver, Reference Papi and Hiver2025):

1. Input-seeking – Surrounding themselves with English through Netflix binges, podcast commutes, or social media scrolling (Lee, Reference Lee2022a; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Akhter and Hashemifardnia2025)

2. Interaction-seeking – Joining Discord servers, commenting on TikTok videos, or voice-chatting in multiplayer games (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2019; Lee, Y.-J., Reference Lee2023)

3. Information-seeking – Instantaneously consulting DeepL for translations or watching YouTube tutorials on tricky grammar points (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016; Arndt & Woore, Reference Arndt and Woore2018)

4. Feedback-seeking – Submitting Reddit posts for native speaker review or using AI writing assistants for real-time corrections (Isbell, Reference Isbell2018; Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2022)

This learner-centered perspective perfectly captures today’s reality – where smartphones have become more powerful than textbooks, and fluency grows through organic digital immersion rather than rigid classroom drills (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2018, Reference Godwin-Jones2019). The rise of IDLE exemplifies this transformation. Consider how modern learners operate (Reinders et al., Reference Reinders, Lai and Sundqvist2022; Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023; Lee, Reference Lee2024): A teenager absorbs colloquial phrases from Twitch streams (input), debates in Facebook groups (interaction), researches slang on Urban Dictionary (information), and refines pronunciation via speech-recognition apps (feedback). These behaviors do not just supplement formal education – they are becoming the primary drivers of language acquisition for digital natives (Butler, Reference Butler2015; Lee, Reference Lee2022a).

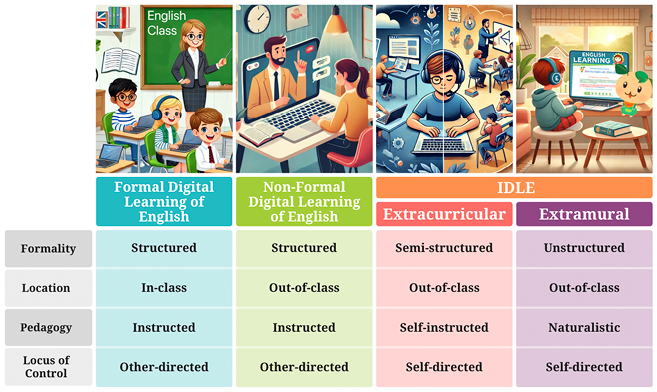

This paradigm shift reflects broader changes in education. As Reinders and Benson (Reference Reinders and Benson2017) demonstrated, effective learning now happens anywhere – during a morning jog (listening to podcasts), in line at Starbucks (flipping through flashcard apps), or between Zoom meetings (chatting with language partners). The four pillars of Language Learning Beyond the Classroom – formality, location, pedagogy, and locus of control – are being supercharged by digital tools that make English acquisition seamless and integrated into daily life (Benson, Reference Benson, Benson and Reinders2011b; Reinders & Benson, Reference Reinders and Benson2017; Lee, Reference 66Lee2019):

Formality: Learners craft their own rhythms, ditching rigid timetables to study when inspiration strikes – whether at dawn, during lunch breaks, or late at night.

Location: Parks, coffee shops, subway cars, or cozy bedrooms transform into vibrant learning hubs, untethered from desks and whiteboards.

Pedagogy: Curricula bend to individual passions – gamers master English through strategy guides, K-pop fans dissect lyrics, and aspiring chefs follow international recipes.

Locus of Control: Learners steer their journeys, choosing apps, media, or peer interactions that resonate with their goals, creating bespoke pathways to fluency.

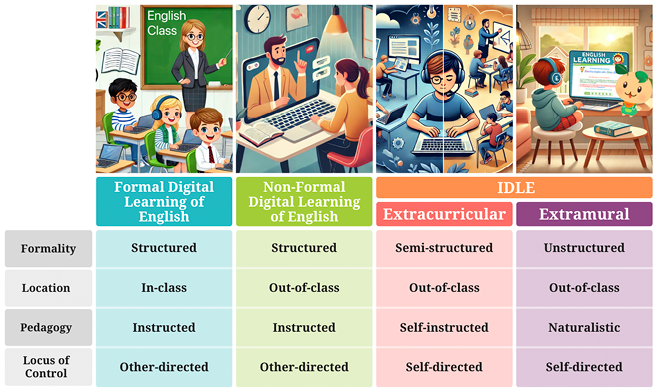

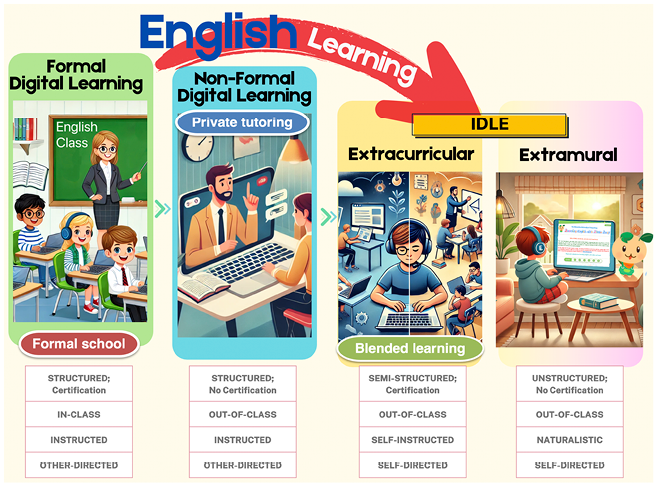

Lee’s (Reference 66Lee2019) IDLE model captures this cultural transformation, showing how digital spaces have evolved into sophisticated learning ecosystems. From algorithm-curated YouTube feeds that teach grammar through pop culture, to AI chatbots offering 24/7 conversation practice, today’s learners are not just studying English – they are ‘living’ it (Lee, Reference Lee2024). As illustrated in Figure 2, these emerging digital learning spaces are not merely alternatives to classrooms; they are becoming the main stage where authentic, motivation-driven language acquisition unfolds (Tsang & Lee, Reference 76Tsang and Lee2023; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025). This revolution has given rise to four distinct types of digital learning spaces:

1. Formal Digital Learning: The Structured Classroom Goes Digital

Here, technology serves traditional teaching methods. Smartboards display grammar exercises, students watch preselected TED Talks, and computer labs host scripted language software sessions. While these tools modernize the classroom, the teacher remains firmly in control – students might interact with digital content, but within strict curricular boundaries (Kim, Reference Kim2015). Think of a class collectively using Rosetta Stone under teacher supervision, with every click tracked and assessed.

2. Non-Formal Digital Learning: Guided Learning Beyond School Walls

This middle ground offers structured lessons outside institutional settings (e.g., shadow education; Yung, Reference Yung2015). A business professional might take scheduled Zoom lessons with a Cambridge-certified tutor on Italki, or a student could enroll in a self-paced TOEFL prep course on Udemy. While more flexible than classroom learning, these options still follow designed syllabi and measurable outcomes – just without school bells or report cards (Yung, Reference Yung2019).

3. Extracurricular IDLE: The Bridge between Classrooms and Curiosity

Blending formal education with personal exploration, this approach lets learners stretch their wings while maintaining ties to academic goals (Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2017; Lee, Reference 66Lee2019). Imagine high schoolers completing teacher-assigned Netflix viewing logs, university students collaborating on Google Docs for group projects, or language app streaks being counted toward course credit (Li, Reference Li2018). The activities are chosen by educators, but execution relies on students’ independent engagement with digital tools (Hwang & Lai, Reference Hwang and Lai2017).

4. Extramural IDLE: Pure Passion-Driven Learning

This is where magic happens organically – gamers coordinating raids in English on Discord, K-pop fans translating lyrics for their Twitter followers, or binge-watchers absorbing accents from British detective series (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019; Vazquez-Calvo et al., Reference Vazquez-Calvo, Zhang, Pascual and Cassany2019). Completely divorced from formal education (Sockett, Reference Sockett2014; Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2017; Lee, Reference 66Lee2019), these activities thrive on intrinsic motivation. Unlike extracurricular IDLE, there is no teacher looking over shoulders – just learners diving into digital worlds where English becomes the natural currency of connection and enjoyment (Lee, Reference Lee2022a).

Figure 2 IDLE in Digital Learning Spaces Based on LBC’s Four Dimensions

The boundaries between these spaces are increasingly fluid (Bruen & Erdocia, Reference Bruen and Erdocia2024), with learners often moving seamlessly from textbook exercises (formal) to language exchange apps (non-formal) to meme-sharing with international friends (extramural) in a single day. This ecosystem demonstrates how digital environments have not just expanded learning opportunities – they have fundamentally redefined what it means to “study” a language (Dizon, Reference Dizon2023; Guo & Lee, Reference Guo and Lee2023).

In December 2024, the Hong Kong Education Bureau awarded a one-time grant of HK$400,000 to K-12 schools, aiming to strengthen students’ English abilities through self-directed learning (Yiu, Reference Yiu2024). The Bureau emphasized that “Language acquisition should not be confined to the classroom, and students also learn through various means…it is important to nurture students’ self-directed learning so that they can proactively take charge of their own learning.” This move highlights the Hong Kong government’s recognition of learning environments beyond the classroom, including digital spaces like IDLE. English teachers are thus encouraged to fully harness these online platforms to help students further develop their English skills (Lee et al., Reference Lee2024; Lee & Taylor, Reference 68Lee and Taylor2024).

Lee’s (Reference Lee2022a) IDLE Continuum Model vividly illustrates this evolving landscape, moving beyond rigid labels to present a fluid spectrum of language learning experiences. Earlier researchers (e.g., Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2017; Lee, Reference 66Lee2019) drew sharp lines between extracurricular learning (loosely connected to schools) and extramural learning (completely outside institutional reach). By contrast, the IDLE continuum reveals how students can move along a connected pathway – from structured, teacher-supported activities (“weak IDLE”) to fully independent, student-driven digital learning in authentic contexts (“strong IDLE”; Lee, Reference Lee2022a, Reference Lee2024).

Research highlights this developmental journey. For instance, Zhang and Liu (Reference Zhang and Liu2022) showed that teachers can play an active role in guiding students as they transition from extracurricular to extramural settings, effectively stretching the classroom’s boundaries. Building on this idea, Liu, Guan, Qiu, and Lee (Reference Lee2024) designed a twelve-week IDLE program that carefully increased learner autonomy. The program began with three weeks of teacher-led instruction, then gradually shifted responsibility to students over the following weeks, culminating in high autonomy by the end. Their results revealed that students in the IDLE program grew much more willing to communicate in English than their peers in traditional classes.

Similarly, Rezai et al. (Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025) explored the effectiveness of both extracurricular and extramural IDLE for Iranian EFL university students’ reading comprehension. After a four-month intervention, both groups performed significantly better than the control group, with no notable difference between them. These findings suggest that both forms of IDLE provide rich environments for language exposure and reading development. Introducing IDLE even in a classroom-based, teacher-supported format (“weak IDLE”) can yield benefits for EFL learners’ reading skills that are just as substantial as those achieved through completely independent, extramural IDLE (“strong IDLE”).

By reimagining learning spaces in this way, the IDLE model empowers students to take ownership of their language journey. It blends the structure of guided learning with the freedom of personal exploration, allowing learners to engage with English in ways that resonate with their interests and aspirations (Lee, Reference Lee2022a). This shift makes language learning more dynamic, meaningful, and personalized – offering a fresh perspective on how students can build autonomy, motivation, and real-world communication skills, as explored further in Section 4 (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Jager and Lowie2022; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Akhter and Hashemifardnia2025).

2.3 IDLE vs. Formal English Education

The notion of the “prosumer” – someone who is both a producer and a consumer – was first introduced by futurist Alvin Toffler in his 1980 book The Third Wave (Toffler, Reference Toffler1980). Toffler envisioned a future where people would move beyond passive consumption and play an active part in shaping the goods, services, and media they engage with. This vision has become even more relevant in the digital age, as Don Tapscott (Reference Tapscott1996, Reference Tapscott2008) highlight how technology empowers ordinary users to be creators. Today, anyone can upload videos to YouTube, personalize products, or contribute to open-source projects, becoming active participants in digital culture.

This idea closely aligns with the concept of “participatory culture,” where individuals do not just passively consume content, but actively create, share, and interact with media and with each other (Lomicka & Ducate, Reference 70Lomicka and Ducate2021). In participatory culture, creative expression and civic engagement are open to almost everyone, thanks to low barriers that invite widespread involvement (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton and Robison2009). There is strong encouragement for people not only to make things but also to share their creations widely, fostering an environment of collaboration and exchange. Informal mentorship is common, as experienced participants naturally guide newcomers, passing along what they have learned. People are motivated by a feeling that their contributions matter, and they develop a sense of social connection and community, caring about and responding to what others have made (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton and Robison2009; Sauro, Reference Sauro2017).

In this evolving landscape, the prosumer is not just a recipient but a co-architect of their own experiences, blurring the traditional line between audience and author (Sauro, Reference Sauro2017). This dual identity resonates strongly with receptive and productive IDLE (Lee, Reference Lee2022a). In receptive IDLE, learners immerse themselves in English-rich environments – streaming Netflix thrillers, binge-watching sitcoms, or scrolling through global news feeds – soaking up accents, idioms, and cultural cues (Lee, Reference 66Lee2019, Reference Lee2022a). Productive IDLE, on the other hand, sees learners using language for personal expression: tweeting clever remarks, debating on Reddit, writing fanfiction, or coordinating strategies in online games (Lee, Reference 66Lee2019, Reference Lee2022a).

Recent research shows that learners rarely separate receptive and productive IDLE into distinct categories (Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2024). Instead, they blend them effortlessly into a rich, continuous learning experience. For instance, someone might binge-watch Bridgerton to absorb the rhythm and elegance of British English, then jump onto Tumblr to unravel plot twists with fans from around the world – transforming passive viewing into active dialogue (Lee, Reference Lee2024). Likewise, a Minecraft enthusiast might study in-game tutorials to grasp vocabulary and mechanics, then collaborate with Indonesian teammates on Discord to plan elaborate builds, turning comprehension into real-time negotiation.

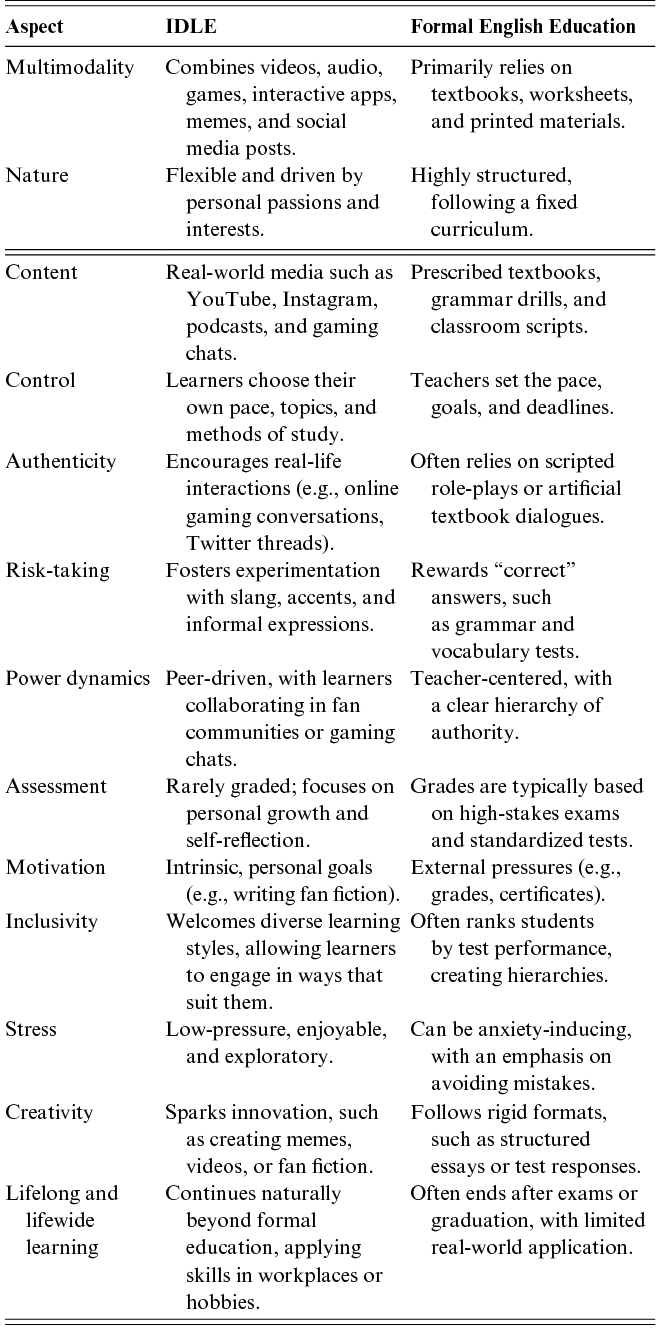

Liu and Lee (Reference Liu, Lee, Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023) also highlight how IDLE offers a unique advantage over conventional classroom methods, which often rely on grammar drills and high-pressure exams. While formal education tends to tether learners to textbooks and rigid assessments, IDLE flourishes in the dynamic terrain of digital culture, where curiosity – not curriculum – fuels engagement. Learners often abandon rote memorization in favor of solving real-world problems, replacing structured lesson plans with spontaneous, self-guided exploration (Soyoof et al., Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Neumann and Vazquez-Calvo2024). This shift empowers them to use English not just as a subject to study, but as a living tool for creativity, connection, and personal growth (Lee, Reference Lee2022a; Dressman et al., Reference Dressman, Toffoli and Lee2025; see Table 1 for a detailed contrast).

| Aspect | IDLE | Formal English Education |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodality | Combines videos, audio, games, interactive apps, memes, and social media posts. | Primarily relies on textbooks, worksheets, and printed materials. |

| Nature | Flexible and driven by personal passions and interests. | Highly structured, following a fixed curriculum. |

| Content | Real-world media such as YouTube, Instagram, podcasts, and gaming chats. | Prescribed textbooks, grammar drills, and classroom scripts. |

| Control | Learners choose their own pace, topics, and methods of study. | Teachers set the pace, goals, and deadlines. |

| Authenticity | Encourages real-life interactions (e.g., online gaming conversations, Twitter threads). | Often relies on scripted role-plays or artificial textbook dialogues. |

| Risk-taking | Fosters experimentation with slang, accents, and informal expressions. | Rewards “correct” answers, such as grammar and vocabulary tests. |

| Power dynamics | Peer-driven, with learners collaborating in fan communities or gaming chats. | Teacher-centered, with a clear hierarchy of authority. |

| Assessment | Rarely graded; focuses on personal growth and self-reflection. | Grades are typically based on high-stakes exams and standardized tests. |

| Motivation | Intrinsic, personal goals (e.g., writing fan fiction). | External pressures (e.g., grades, certificates). |

| Inclusivity | Welcomes diverse learning styles, allowing learners to engage in ways that suit them. | Often ranks students by test performance, creating hierarchies. |

| Stress | Low-pressure, enjoyable, and exploratory. | Can be anxiety-inducing, with an emphasis on avoiding mistakes. |

| Creativity | Sparks innovation, such as creating memes, videos, or fan fiction. | Follows rigid formats, such as structured essays or test responses. |

| Lifelong and lifewide learning | Continues naturally beyond formal education, applying skills in workplaces or hobbies. | Often ends after exams or graduation, with limited real-world application. |

IDLE stands out because it allows learners to engage with English in authentic, everyday situations (Dressman & Sadler, Reference Dressman and Sadler2020). On platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and online games, learners are driven by personal interests rather than external pressures such as grades or exams (Godwin-Jones, Reference Godwin-Jones2019; Lee et al., Reference Lee2024). For instance, they might analyze their favorite TV shows, join fan forums to discuss plot twists, or debate trending topics on Reddit (Sauro, Reference Sauro2017; Isbell, Reference Isbell2018). This freedom enables learners to choose topics that excite them, explore creative expressions like experimenting with slang or accents, and even create memes (Lee, Reference Lee2024). Without the stress of grades, learners feel safe to take risks, make mistakes, and grow naturally (Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2023; Uztosun & Kök, Reference Uztosun and Kök2023).

IDLE also goes beyond language – it fosters real-world skills that learners can use in their careers, hobbies, and global interactions (Lee & Drajati, Reference 67Lee and Drajati2019a; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a). For example, someone who learns English by gaming might later apply those same communication skills in a virtual work environment or when traveling abroad. In contrast, formal English education provides a structured foundation. Classroom learning focuses on textbooks, grammar drills, and teacher-led lessons to build a strong understanding of grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. This approach ensures students develop basic language skills systematically (Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023). However, in exam-driven systems, the emphasis on achieving correctness and high scores could limit creativity and induce anxiety (Lee, Reference Lee, Dressman and Sadler2020a). For example, students might memorize grammar rules for a test but struggle to use them naturally in conversations.

Formal education often lays a solid groundwork for language learning, offering structure and clarity (Dressman & Sadler, Reference Dressman and Sadler2020). Yet, in the updated L2 English learning pyramid, Sundqvist (Reference Sundqvist2024) proposes that Extramural English – language exposure beyond the classroom – has become a key individual difference factor, and for many learners, it now serves as the true starting point for acquiring English. This shift aligns somehow with the IDLE Continuum Model, where IDLE complements the limitations of formal instruction by fostering confidence, fluency, and real-world communication skills (Lee, Reference Lee2022a; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024). Together, formal education and IDLE form a balanced and dynamic learning ecosystem. A student might master grammar rules in class, then apply them organically by posting on social media, chatting with international teammates in online games, or discussing novels in a virtual book club (Lee, Reference Lee2022a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025). This fusion of structured learning and spontaneous exploration allows learners to build both academic precision and practical fluency – equipping them not only for classroom success but also for meaningful interaction in global, everyday contexts (Sauro & Zourou, Reference Sauro and Zourou2019).

2.4 The Growth of IDLE Research

The past decade has witnessed an explosive surge in IDLE scholarship, marked by empirical studies, seminal books, and systematic reviews that have shaped the field. Sockett (Reference Sockett2014) pioneered work Online Informal Learning of English, which mapped how French learners absorbed English organically through digital media like podcasts and web forums. This foundational study redefined perceptions of informal learning, proving its legitimacy as a research-worthy phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Sundqvist (Reference Sundqvist2009, Reference Sundqvist2019, Reference Sundqvist2024) carved a parallel path in Northern Europe with their concept of Extramural English (also see Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016). By analyzing Swedish gamers who mastered English through World of Warcraft raids and online forums, they revealed how leisure activities could rival – or even surpass – classroom instruction in building fluency. Their work challenged educators to rethink the boundaries between “play” and “learning,” urging schools to harness students’ digital passions.

The field gained global momentum with Dressman and Sadler’s Handbook of Informal Language Learning (Reference Dressman and Sadler2020). This volume wove together historical roots, cultural contexts, and case studies from Asia to the Americas, showcasing IDLE’s universality. Crucially, it proposed frameworks to bridge informal digital practices with formal curricula – for example, suggesting teachers assign TikTok video analyses as homework to validate students’ out-of-class learning.

Reinders, Lai, and Sundqvist’s Language Learning Beyond the Classroom (Reference Reinders, Lai and Sundqvist2022) deepened these insights, offering educators a toolkit of theories, methods, and strategies. The book also demonstrated how to track learners’ informal language learning habits to inform lesson plans or use social media analytics to measure linguistic growth, blending rigor with innovation.

Dressman, Lee, and Perrett (Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023) then shifted gears from theory to action. Their work delivered ready-to-use lesson plans, such as having students design social media campaigns to practice writing or analyze movie dialogue to study informal language expressions. These strategies showed teachers how to weave IDLE’s spontaneity into structured classrooms without sacrificing academic goals.

Most recently, Lee, Zou, and Gu (Reference Lee, Zou and Gu2024) have propelled the field forward with a teacher-centric guide. Their edited volume equips educators to craft IDLE-aligned activities – like guiding gamers to write strategy guides in English. By prioritizing student interests, these approaches turn hobbies into learning engines, proving that engagement and rigor need not clash.

Review Papers on IDLE

As IDLE research grew, scholars published several review papers. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Zou, Cheng, Xie, Wang and Au2021) analyzed extramural language learning, highlighting that most activities – such as watching videos, listening to music, and reading blogs – were primarily receptive. Their findings emphasized the positive impact of these activities on both linguistic skills (e.g., vocabulary growth) and psychological factors (e.g., motivation and confidence). Soyoof et al. (Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Vazquez-Calvo and McLay2023) conducted a scoping review of IDLE, examining its linguistic, cultural, affective, and digital literacy dimensions across Asian and European contexts from 1980 to 2020. They demonstrated how IDLE promotes language learning in a variety of cultural and technological environments.

Lee (Reference Lee, Reinders, Lai and Sundqvist2022b) reviewed seventy-six studies on “language learning and teaching beyond the classroom,” identifying key gaps in the field, including the need for more rigorous methodologies and innovative tools to assess IDLE’s potential. In a related book, Lee (Reference Lee2022a) synthesized findings from multiple studies, showing strong links between IDLE activities and positive outcomes for EFL learners, such as enhanced fluency, motivation, and digital literacy.

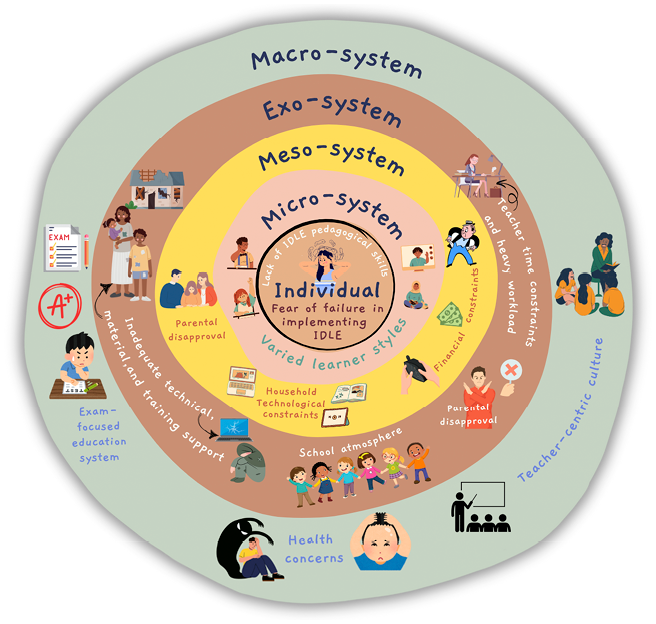

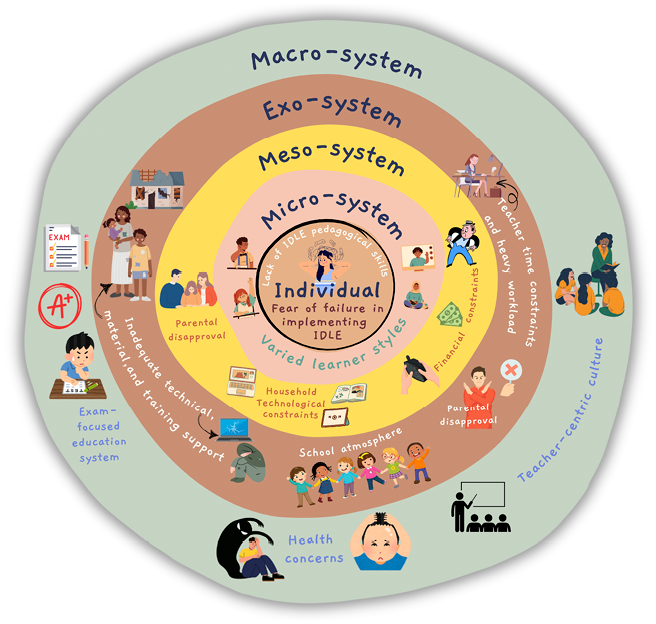

Guo and Lee (Reference Guo and Lee2023) applied Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Reference Bronfenbrenner1976, Reference 59Bronfenbrenner1979) to explore the factors influencing learners’ IDLE engagement. They found that most critical factors operated at the individual and micro-system levels, such as personal interests, peer interactions, and access to technology. They also called for more research on less-studied levels, such as the meso-system (e.g., school–family relationships), exo-system (e.g., societal influences), macro-system (e.g., cultural norms), and chrono-system (e.g., the effects of technological advancements over time). Inspired by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Reference Bronfenbrenner1976, Reference 59Bronfenbrenner1979), Rezai et al. (Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024b) examined teachers’ perspectives on students’ IDLE engagement, offering strategies to better support learners outside the classroom.

Guan and colleagues (Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024) made a significant contribution to IDLE research with a meta-analysis on AI-driven IDLE. Their study revealed that AI tools – such as language-learning chatbots, adaptive apps, and virtual reality platforms – greatly improved learners’ English proficiency, self-regulation, and engagement.

Kusyk et al. (Reference Kusyk, Arndt, Schwarz, Yibokou, Dressman, Sockett and Toffoli2025) carried out a scoping review exploring trends in informal second language learning, analyzing 206 studies published between 2000 and 2020. Their review highlighted a surge in research beginning in 2011, with peak activity between 2017 and 2019. The three most commonly explored themes were second language development (18.2%), mapping informal learning practices (17.5%), and describing informal learning activities (14.3%). They also uncovered a confusing mix of overlapping terms – such as out-of-class language learning, informal second language learning, Extramural English, online informal English learning, and IDLE – leading to what is known as the “jingle-jangle fallacy.” The “jingle–jangle fallacy” occurs when different constructs are mistakenly considered the same because they have the same name (jingle), or when similar constructs are mistakenly considered different because they have different names (jangle; Kelley, Reference Kelley1927). In language learning research, this fallacy can result in conceptual confusion and hinder the comparison of findings across studies (Kusyk et al., Reference Kusyk, Arndt, Schwarz, Yibokou, Dressman, Sockett and Toffoli2025). A wide range of theoretical frameworks were applied, including sociocultural theory, complex dynamic systems, learner autonomy, and ecological approaches. Quantitative methods dominated (41%), followed by qualitative (33%) and mixed methods (20%), with surveys (35.7%) and interviews (23%) being the most used tools. The research primarily focused on young adults aged 18–25 (54.4%) and adolescents aged 11–17 (21.8%), with recent studies concentrating on Europe and East Asia. English was the target language in most cases (66.4%). Various learner-related variables were examined, such as usage frequency, attitudes, motivation, activity diversity, confidence in using the second language, and willingness to communicate. Although the review concluded before the rise of AI tools, it offers a comprehensive snapshot of the field’s evolution and pinpoints promising directions for future inquiry.

Liu, Soyoof, Lee, and Zhang (Reference Liu, Soyoof, Lee and Zhang2025) conducted a thematic review of IDLE research, analyzing forty-nine empirical studies from Asian EFL contexts published between 2014 and 2024. Echoing the trends identified by Kusyk et al. (Reference Kusyk, Arndt, Schwarz, Yibokou, Dressman, Sockett and Toffoli2025), they found that IDLE has gained substantial attention, especially in the past four years. Their review revealed that IDLE has been examined through various lenses of individual differences – linguistic, emotional, and cultural. Another key insight was the nuanced and sometimes complicated relationship between teachers and IDLE practices. The study also emphasized how unequal access to digital tools and differing levels of digital literacy shaped learners’ participation in IDLE. Drawing from these emerging patterns, the authors proposed several avenues for future research.

Dressman et al. (Reference Dressman, Toffoli and Lee2025) examined forty-seven narratives drawn from fourteen studies focused on informal language learning. These narratives, rich in ethnographic detail, traced how individuals’ language abilities evolved over time in informal settings. By analyzing these stories, the researchers were able to map out seven distinct pathways of language development, shedding light on key factors and circumstances that shape each learner’s experience. Their review makes it clear that IDLE does not follow a single, predictable route; instead, it is a highly individualized process shaped by a range of personal and contextual variables.

Emerging Trends and Expanding Horizons

The field of IDLE is witnessing rapid expansion, sparking a proliferation of research that is reshaping our perspectives on language learning in the digital era. For instance, Rezai (Reference Rezai2024) and Rezai et al. (Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a) investigated how IDLE influences the professional engagement of EFL teachers. Moving beyond simple observation, they designed a robust instrument to systematically measure teachers’ own involvement in digital informal learning. This innovative scale provides concrete metrics for evaluating educators’ interactions with digital environments, offering valuable insights into the ways these platforms impact teaching practices.

Meanwhile, the infusion of artificial intelligence into IDLE has become a major focal point. Studies by Guan, Zhang, and Gu (Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024), along with Liu, Darvin, and Ma (Reference 69Liu, Darvin and Ma2024a, Reference Liu, Darvin and Ma2024b), have uncovered how AI-driven tools are revolutionizing language learning. Innovative technologies such as chatbots simulate real-life conversations, AI-powered writing assistants provide personalized feedback, and immersive virtual reality platforms create engaging environments for practice (Naghdipour, Reference Naghdipour2022). These tools offer learners tailored, interactive experiences that make practicing English more accessible and enjoyable than ever before.

But the enthusiasm is not confined to English alone. Reflecting our increasingly interconnected world, researchers have begun turning their attention to Languages Other Than English (LOTE). For example, Liu, Zhao, and Yang (Reference Yang, Xu, Liu and Yu2024) explored how learners are informally studying French and German through digital platforms. Using language apps, online communities, and digital media, learners are finding creative and dynamic ways to immerse themselves in new languages. Similarly, Lee et al. (Reference Lee and Chiu2023) examined how multilingual learners are picking up Korean through informal digital means. From diving into Korean drama fan sites to joining German gaming forums, these platforms offer authentic, real-world contexts that foster language exposure and practice. Such informal engagement not only increases learners’ time spent with the language but also boosts their willingness to communicate and may enhance their overall communicative competence.

3 Antecedents and Consequences of IDLE

As IDLE gains recognition as one of the key subfields within CALL research, scholars have increasingly turned their attention to two main questions (Soyoof et al., Reference Soyoof, Reynolds, Vazquez-Calvo and McLay2023; Lee, Reference Lee2024): How does IDLE influence outcomes? And what motivates individuals to engage in it more frequently?

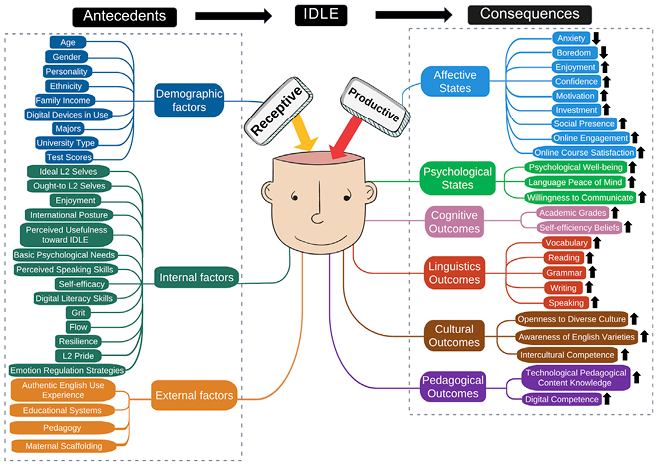

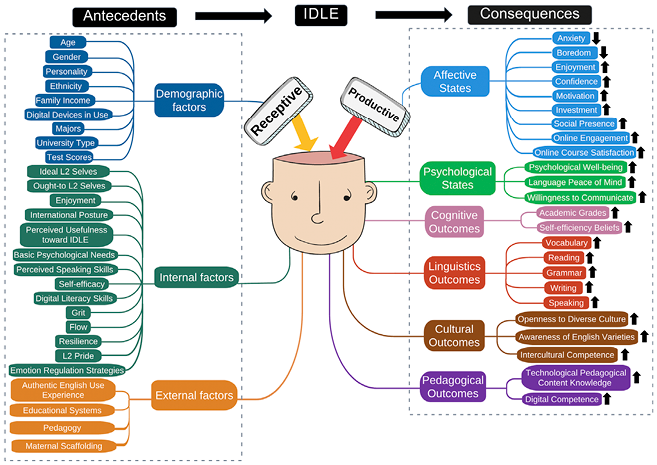

To date, researchers have identified over forty distinct factors – both causes and effects – linked to IDLE. These findings, illustrated in Figure 3, offer rich insights into how IDLE shapes the learning journey and what encourages individuals to participate. For example, those who engage in receptive activities (e.g., watching English YouTube videos) or productive ones (e.g., chatting with English speakers) often report a wide range of benefits. These include emotional gains (e.g., increased enjoyment), psychological boosts (e.g., enhanced psychological well-being), academic improvements (e.g., better grades), linguistic development (e.g., vocabulary growth), cultural awareness (e.g., becoming more tolerant toward varieties of English), and even digital literacy.

Figure 3 Antecedents and Consequences of IDLE

On the flip side, several factors have been found to influence IDLE participation. These include demographic traits (e.g., age), internal characteristics (e.g., international outlook), and external conditions (e.g., the structure of the education system). Mapping these relationships provides a valuable evidence base for educators and researchers to design, adapt, and implement IDLE activities or intervention programs in ways that are both scientifically grounded and locally relevant (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025).

3.1 Consequences of IDLE

This section explores the wide-ranging benefits of IDLE, focusing on six major areas: emotional, psychological, cognitive, linguistic, cultural, and pedagogical. The first five notably influence learners, while the pedagogical impact is most relevant to educators. Growing research suggests that IDLE holds the potential to reshape how students learn new languages and how teachers design their lessons. Each domain below presents key research findings and the scholars behind them, followed by a discussion of these results. Since most evidence is correlational, it is important to interpret these findings with appropriate caution.

Affective Benefits

Lowered anxiety (Lee & Xie, Reference Lee and Xie2023; Uztosun & Kök, Reference Uztosun and Kök2023; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Bollansée, Prophète and Peters2024; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025)

Less boredom (Taherian et al., Reference Taherian, Shirvan, Yazdanmehr, Kruk and Pawlak2023)

Greater enjoyment (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Lee & Xie, Reference Lee and Xie2023; Tsang & Lee, Reference 76Tsang and Lee2023; Lee et al., Reference Lee2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024; Fu, Reference Fu2025; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025)

Increased confidence (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Lee & Drajati, Reference Lee and Drajati2019b; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Liu, Li and Chen2025)

Heightened motivation (Lee & Drajati, Reference Lee and Drajati2019b; Tsang & Lee, Reference 76Tsang and Lee2023; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Bollansée, Prophète and Peters2024; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025)

Stronger investment (Liu & Darvin, Reference Liu and Darvin2023)

Enhanced social presence (Wu, Reference Wu2023)

Higher online engagement (Wu, Reference Wu2023)

Higher online course satisfaction (Zheng & Xiao, Reference Zheng and Xiao2024)

Learning and teaching a new language are deeply emotional processes (Richards, Reference 73Richards2020). For teachers, understanding and responding to learners’ emotions is a core professional skill. For students, emotions shape how they approach and absorb new knowledge. In recent years, the field has experienced an “affective turn” (Prior, Reference Prior2019), as researchers increasingly acknowledge the central role of emotions in language learning. Early studies focused mostly on negative emotions – anxiety, fear, or shame – but the rise of positive psychology has ushered in a wave of research on positive experiences in language acquisition (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014, Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, MacIntyre, Gregersen and Mercer2016). Positive psychology seeks not just fleeting happiness but authentic well-being, resilience, fulfillment, and a sense of being true to oneself (MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Gregersen and Mercer2016). This has shifted scholarly attention toward the power of positive emotions to enhance language learning.

This new focus on emotion and well-being has deeply influenced research on IDLE. Studies now suggest that IDLE significantly shapes learners’ emotions and attitudes, nurturing positive feelings while easing negative ones (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Uztosun & Kök, Reference Uztosun and Kök2023). IDLE reduces the anxiety common in language learning by creating a relaxed, low-pressure environment. Digital tools (e.g., language apps and educational games) let students practice English at their own rhythm, free from the scrutiny and stress of the traditional classroom. This sense of autonomy makes learners more comfortable and less afraid of making linguistic mistakes (Uztosun & Kök, Reference Uztosun and Kök2023; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Bollansée, Prophète and Peters2024).

Lee and Xie (Reference Lee and Xie2023), using a person-centered approach, found intriguing patterns among 1,265 Korean EFL learners who participated in a variety of IDLE activities. Their findings showed that students who balanced their IDLE time across gaming, entertainment, English learning, and social interaction experienced noticeably less anxiety during face-to-face English conversations than those whose IDLE activities revolved mainly around gaming and entertainment.

But the benefits of IDLE go beyond reducing anxiety – it also injects excitement and genuine interest into language learning (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024). Interactive digital platforms turn what could be a monotonous task into an engaging, playful journey, sparking curiosity and making learning feel meaningful and fun (Taherian et al., Reference Taherian, Shirvan, Yazdanmehr, Kruk and Pawlak2023). Lee and Xie (Reference Lee and Xie2023) further discovered that learners who diversified their IDLE experiences – incorporating English learning and socialization along with entertainment – reported greater enjoyment in studying English than those who stuck only to gaming and entertainment. The hands-on, interactive features of these digital tools keep learners actively involved, boosting both their motivation and enthusiasm.

Learners often discover real enjoyment in self-directed activities tailored to their own interests (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025). Whether it is watching English-language YouTube videos, joining online communities, or exploring digital content tied to their hobbies, these experiences allow students to connect with English in ways that feel meaningful and fun (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021). Here, learning blends seamlessly with leisure, making progress feel less like work and more like play (Chik & Ho, Reference Chik and Ho2017).

Small wins – such as understanding a movie without subtitles or confidently posting in an online forum – can give learners a powerful boost in self-belief (Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2023). Each success story strengthens their confidence and encourages them to keep going (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Lee & Drajati, Reference Lee and Drajati2019b). This growing self-assurance motivates learners to take on new challenges and fosters a positive image of themselves as capable language users (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Liu & Lee, Reference Liu, Lee, Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024; Fu, Reference Fu2025).

IDLE naturally integrates language practice into learners’ daily passions, whether that is gaming, music, or social media (Dressman et al., Reference 61Dressman, Lee and Perrot2023). When learning is woven into activities they already love, motivation and commitment soar (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Guan et al., Reference Guan, Li and Gu2024). This relevance inspires learners to invest more time and energy, making English a natural and enjoyable part of everyday life (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023).

Digital platforms also build a strong sense of community, connecting learners with peers around the world (Sauro, Reference Sauro2017; Vazquez-Calvo et al., Reference Vazquez-Calvo, Zhang, Pascual and Cassany2019). Through online discussions, comments, and collaboration, students gain a sense of belonging to a supportive network where they can share, learn, and encourage each other (Wu, Reference Wu2023). Such connections not only increase motivation but also provide the emotional support needed for sustained learning (Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference 78Zadorozhnyy and Lee2025).

Zheng and Xiao (Reference Zheng and Xiao2024) explored how engaging in IDLE influences online course satisfaction among 563 Chinese university EFL students. Their findings revealed that students who participated in IDLE activities more often felt more satisfied with their online courses, appreciating both the course design and their teachers’ effectiveness. The study also uncovered that self-regulated learning online played a key mediating role in this relationship. In other words, students who frequently engaged in IDLE tended to develop stronger self-regulation skills, such as setting goals, managing their time, using effective learning strategies, and evaluating their own progress. These enhanced skills, in turn, boosted their satisfaction with online courses.

Psychological Benefits

Better psychological well-being (Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2024)

Greater autonomy and sense of relatedness (Wu & Wang, Reference Wu and Wang2025)

Growth in self-regulated online learning (Rezai & Goodarzi, Reference Rezai and Goodarzi2025)

Flow experiences (Wu & Wang, Reference Wu and Wang2025)

Increased grit (Lee & Lu, Reference Lee and Lu2023; Liu & Lee, Reference Liu, Lee, Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023; Fu, Reference Fu2025)

Greater peace of mind in language learning (Ghasemi & Noughabi, Reference Ghasemi and Noughabi2024)

Higher willingness to communicate (Lee & Drajati, Reference Lee and Drajati2019b; Taherian et al., Reference Taherian, Shirvan, Yazdanmehr, Kruk and Pawlak2023; Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2023; Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Yang2024; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xu, Liu and Yu2024; Fu, Reference Fu2025; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Yao and Lee2025; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nesi and Milin2025)

The psychological rewards of engaging in IDLE reach well beyond simple language gains – they play a powerful role in nurturing learners’ mental health and boosting their openness to communication (Taherian et al., Reference Taherian, Shirvan, Yazdanmehr, Kruk and Pawlak2023; Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2024; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xu, Liu and Yu2024). By creating a low-stress, supportive learning space, IDLE helps foster a sense of balance and well-being in daily life (Lee & Chiu, Reference Lee and Chiu2024). When students interact with enjoyable digital platforms, language study becomes not just more relaxed, but also more personally satisfying compared to traditional classroom approaches (Liu & Lee, Reference Liu, Lee, Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023; Ghasemi & Noughabi, Reference Ghasemi and Noughabi2024). For instance, Rezai and Goodarzi (Reference Rezai and Goodarzi2025) discovered that among 325 Iranian EFL students, those who used IDLE more frequently displayed stronger skills in self-regulated online learning. These learners excelled at setting goals, organizing their study environment, developing effective strategies, managing their time, seeking help when needed, and evaluating their own progress.

Wu and Wang (Reference Wu and Wang2025) discovered that when 333 Chinese university students used GenAI-supported IDLE, they often entered a state of “flow” – that deep, effortless concentration where learning feels both easy and enjoyable (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi2014). Importantly, these students also felt a greater sense of independence and a stronger bond with others – two key factors for psychological well-being. This shows that GenAI-powered language activities can help students take charge of their own learning while feeling connected, even in a digital environment.

IDLE also nurtures “grit” – the determination to keep trying and stay interested, even when faced with setbacks (Duckworth, Reference Duckworth2017). By giving learners the chance to repeatedly face new challenges and still enjoy the process, IDLE has the potential for strengthening their grit (Liu & Lee, Reference Liu, Lee, Toffoli, Sockett and Kusyk2023; Fu, Reference Fu2025). Lee and Xie (Reference Lee and Xie2023), using a person-centered approach, found that Korean EFL learners who balanced their IDLE time among gaming, entertainment, English study, and socializing showed much more grit than those who focused mainly on gaming and entertainment.

Another key psychological benefit is what researchers describe as “foreign language peace of mind” – a comforting sense of inner calm and coherence while navigating a new language (Ghasemi & Noughabi, Reference Ghasemi and Noughabi2024). Among 316 Iranian EFL students, those who regularly engaged in IDLE activities – whether listening, reading, writing, or speaking – reported feeling more at ease with English, which in turn boosted their willingness to communicate. Free from the anxiety of being judged or making mistakes, learners can experiment, participate in online conversations, comment on social media, or use language apps without the fear that often shadows classroom settings. This growing sense of ease naturally leads to greater willingness to communicate, even in unfamiliar or real-world situations. As learners become more confident and adept, they are more likely to start conversations, offer opinions, or connect with strangers – actions they might have shied away from before (Ghasemi & Noughabi, Reference Ghasemi and Noughabi2024; Lee et al., Reference Lee2024).

Cognitive Advantages

Improved academic achievement (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015; Sundqvist & Wikström, Reference Sundqvist and Wikström2015)

Stronger performance on standardized English exams (Zou et al., Reference Zou, Liu, Li and Chen2025)

Greater self-efficacy (Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2023)

IDLE does not just broaden learners’ language skills – it fuels cognitive growth on multiple levels. When students immerse themselves in informal digital activities – like exploring educational apps, watching insightful videos, or joining online discussions – they add meaningful layers to their formal education. Research by Lai et al. (Reference Lai, Zhu and Gong2015) and Sundqvist and Wikström (Reference Sundqvist and Wikström2015) shows that this combination of formal and informal learning often leads to higher grades and better classroom participation. Supporting this, Zou et al. (Reference Zou, Liu, Li and Chen2025) found that Chinese university students who regularly participated in meaning-focused IDLE activities scored higher on the College English Test–Band 4 (CET-4), a rigorous, nationwide exam that measures listening, reading, writing, and translation skills across China. The CET-4, much like academic grades, is designed to assess a wide range of cognitive abilities, from comprehension to language production. In this way, IDLE acts as both a language booster and a cognitive catalyst – helping students achieve more in their studies while strengthening their ability to analyze, understand, and use English in practical contexts.

Beyond academic results, IDLE fosters a stronger sense of self-efficacy – the conviction that one can take charge of their own learning process (Zadorozhnyy & Lee, Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2023). When students make choices about what and how to learn, they gain confidence and stay motivated, consistently building their language skills. Zadorozhnyy and Lee (Reference Zadorozhnyy and Lee2023) highlight how this sense of ownership leads to steady progress and personal development.

Linguistic Benefits

Expanded vocabulary (Sundqvist & Wikström, Reference Sundqvist and Wikström2015; Jensen, Reference 64Jensen2017; Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2019; Alhaq, Reference Alhaq2022; Lai et al., Reference Lai, Liu, Hu, Benson and Lyu2022; Warnby, Reference Warnby2022; Lai & Wang, Reference Lai and Wang2024, Reference Lai and Wang2025; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024c)

Sharper reading comprehension (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025)

Deeper understanding of grammar (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016)

Stronger writing skills (Kusyk, Reference Kusyk2017)

Enhanced speaking abilities (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009; Lee & Dressman, Reference Lee and Dressman2018; Tsang & Lee, Reference 76Tsang and Lee2023)

One of IDLE’s greatest advantages is its ability to boost every aspect of language proficiency. When learners immerse themselves in genuine, everyday situations – such as gaming online, watching streaming videos, or chatting on social media – they naturally pick up fresh vocabulary, including slang and expressions rarely found in traditional textbooks (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2022; Lai & Wang, Reference Lai and Wang2024). This natural exposure leads to a richer, more practical command of language (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009; Lee & Dressman, Reference Lee and Dressman2018). Watching movies or TV with subtitles, browsing blogs, and reading online articles all sharpen reading comprehension skills (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016; Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025). For example, Rezai et al. (Reference Rezai, Ashkani and Moradian2025) found that Iranian university students who participated in both extracurricular and informal IDLE activities showed significantly higher reading comprehension scores than those in the control group.

Engaging with a wide range of written texts allows learners to decode meanings, appreciate different writing styles, and handle increasingly complex content (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016; Tsang, Reference Tsang2023). Frequent encounters with natural language in context mean learners start to pick up grammar intuitively, without needing to memorize endless rules (Cole & Vanderplank, Reference 60Cole and Vanderplank2016). Observing and hearing correct usage in everyday settings helps them internalize grammatical structures, making their language use more accurate and fluid (Arndt & Woore, Reference Arndt and Woore2018).

Writing skills also get a boost as students engage in real communication – whether it is posting on forums, leaving comments, or keeping online journals (Kusyk, Reference Kusyk2017). These activities sharpen their ability to organize thoughts, express ideas clearly, and tailor their writing for different audiences. Meanwhile, video chats, multiplayer games, and interactive online discussions offer a safe space to practice speaking, improving both fluency and pronunciation by mimicking native speakers and interacting in real time (Lee & Dressman, Reference Lee and Dressman2018; Tsang & Lee, Reference 76Tsang and Lee2023). By combining a range of IDLE activities with targeted classroom support from teachers to address anything not picked up through IDLE, IDLE fosters the development of well-rounded language skills (Schurz & Sundqvist, Reference Schurz and Sundqvist2022).

Cultural Awareness

Openness to diverse cultures (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023)

Awareness of English varieties (Lee & Drajati, Reference 67Lee and Drajati2019a; Lee, Reference Lee2020b; Lee et al., Reference Lee2024)

Development of intercultural competence (Lee, Reference Lee2020b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023)

IDLE does far more than build language skills – it serves as a powerful gateway to cultural awareness, immersing learners in a tapestry of perspectives and ideas from around the globe (Lee, Reference Lee2020b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023; Lee et al., Reference Lee2024). When learners dive into international content, they are not simply acquiring new vocabulary or grammar; they are stepping into new worlds, encountering different traditions, beliefs, and viewpoints that expand their understanding of what it means to be part of a global society (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023).

Engaging with authentic materials – whether it is watching foreign films, reading international literature, or joining global online discussions – pushes learners to open their minds and adapt to unfamiliar cultural experiences (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023). This kind of exposure not only nurtures curiosity and appreciation for diversity, but it also breaks down stereotypes, fostering empathy and genuine respect for others (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023). As learners connect with realities beyond their own, they become more inclusive and better equipped to navigate an interconnected world (Lee, Reference Lee2022a).

Through IDLE, learners encounter a rich array of English accents and dialects, deepening their appreciation for the language’s diversity on a global scale (Lee & Drajati, Reference 67Lee and Drajati2019a; Lee, Reference Lee2020b). Hearing English spoken in countless varieties – from British and American to Australian, Indian, or Korean – highlights its role as a living, evolving lingua franca (Graddol, Reference Graddol2006; Crystal, Reference Crystal2010). This awareness encourages learners to become flexible communicators, comfortable with the many ways English is shaped by different cultures and histories (Lee & Drajati, Reference 67Lee and Drajati2019a).

Such wide-ranging exposure naturally builds intercultural competence, arming learners with the confidence and sensitivity needed for effective cross-cultural communication (Lee & Drajati, Reference 67Lee and Drajati2019a). They become skilled at interpreting subtle cultural cues and adjusting their communication styles to bridge differences. True intercultural competence means moving beyond awareness – it is about applying empathy, active listening, and adaptability in real-life interactions across diverse settings. By nurturing cultural awareness, IDLE prepares learners to actively participate in our interconnected world (Lee, Reference Lee2020b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Bao and Liu2023). It empowers them to engage in thoughtful conversations, work collaboratively with people from all backgrounds, and make meaningful contributions to global communities. In this way, IDLE not only advances cultural fluency – an invaluable asset in today’s multicultural societies and workplaces – but also supports the lifelong learning journey envisioned by the UN SDGs, ensuring learners are prepared to contribute meaningfully throughout their lives (Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist, Ziegler and González-Lloret2022).

Pedagogical Enhancements

Stronger technological pedagogical content knowledge (Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a)

Greater digital competence (Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a)

Job engagement (Rezai et al., Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a)

The impact of IDLE is not limited to students – it powerfully empowers educators as well, allowing them to elevate their teaching and seamlessly weave technology into their classrooms. For example, Rezai et al. (Reference Rezai, Soyoof and Reynolds2024a) explored how IDLE relates to technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK), digital competence, and job engagement among 375 Iranian EFL teachers. Their findings revealed a strong positive connection: teachers who engaged with IDLE displayed higher levels of TPACK and digital competence, which in turn boosted their engagement and enthusiasm for their work. Notably, both TPACK and digital competence served as bridges, linking IDLE involvement to increased job satisfaction and commitment. These results highlight that IDLE not only advances teachers’ technological and pedagogical skills but also fuels their passion for teaching, fostering a more dynamic, innovative, and rewarding classroom environment.

However, it is important to recognize that not every teacher is able to enhance their pedagogical or technological skills. For example, Becker (Reference Becker2022) found that most of the seventy-three EFL teachers surveyed in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, had never used video games in their teaching. Many cited a lack of interest in video games, uncertainty about effective methods, and unfamiliarity with the necessary teaching strategies. Similar barriers were reported by Hong Kong EFL teachers in Zadorozhnyy et al. (Reference Zadorozhnyy, Lai and Lee2025). Based on 470 survey responses from 159 teachers collected between 2019 and 2024, the challenges to integrating IDLE stemmed from both internal factors (like insufficient training and familiarity) and external pressures (such as exam-driven curricula and heavy workloads). Therefore, it becomes clear that while individual initiative is important, broader systemic or structural support is also essential to help teachers successfully bring innovative pedagogies like IDLE into schools.

3.2 Antecedents of IDLE

The exploration of IDLE’s benefits has sparked a deep interest in understanding the factors that encourage and sustain learners’ engagement with these digital learning environments. Researchers are eager to uncover what drives individuals to adopt IDLE practices and how these motivators can be nurtured to enhance language learning outcomes. These influential factors are grouped into three main categories: sociobiographic, learner-internal, and learner-external.

Sociobiographic Factors

Gender (Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2023)