Introduction

Scholars have sounded the alarm about processes of democratic backsliding affecting consolidated democracies (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018). Efforts to undermine judicial independence and media freedom in Poland and Hungary, to delegitimize election results in the United States and, more recently, to erode minority rights in Italy and France all pose serious threats to the stability and integrity of democratic governance. These developments suggest that processes of democratic erosion can affect long‐established democracies and be met with limited public contestation.

Against this backdrop, recent studies have sought to understand the increasing prevalence of democratic backsliding and the conditions that may facilitate it. Some of these efforts have focused on analysing why citizens might support candidates who undermine different dimensions of liberal democracy (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Jacob, Reference Jacob2025; Kaftan & Gessler, Reference Kaftan and Gessler2025; Lewandowsky & Jankowski, Reference Lewandowsky and Jankowski2023; Saikkonen & Christensen, Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023; Wunsch & Gessler, Reference Wunsch and Gessler2023). Generally, these works conclude that citizens are willing to tolerate candidates who undermine democracy as long as these candidates advance their preferred policy positions. In contrast, studies directly probing citizens' commitment to democracy by examining their willingness to trade a democratic political system for other socially desirable outcomes reach a more optimistic conclusion: citizens are often unwilling to trade democracy for greater security or prosperity (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023). These studies suggest that a majority of citizens support democracy and are firmly committed to this political system (see also Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022).

The contradictory nature of these different findings raises some relevant questions. Why, in spite of a strong commitment to democracy among citizens, are some democracies experiencing backsliding processes without strong contestation? How is it that voters are firmly committed to democracy and unwilling to trade this political system for other socially desirable considerations, but they fail to hold accountable candidates who undermine democracy?

We contribute to these debates by proposing that citizens may tolerate backsliding because it does not always involve the democratic principles that they value most. While citizens may not easily relinquish free elections, they may be more open to abandon key liberal principles of democracy such as judicial independence, media freedom or horizontal accountability. This may explain why backsliding processes, characterized by a gradual erosion of these principles, along with the preservation of elections, may be acceptable to some citizens. This explanation could help us reconcile the divergent findings between studies that directly examine the robustness of citizens' support for democracy, which have put a strong emphasis on free elections (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023) and those that focus on their likelihood of supporting candidates who undermine that political system (e.g., Saikkonen & Christensen, Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023; Wunsch & Gessler, Reference Wunsch and Gessler2023).

We address these questions through a conjoint experiment in the United Kingdom, Poland, Hungary, Spain, Sweden, Portugal and Israel. In the experiment, participants were asked to rate and choose among several hypothetical countries that varied in terms of their respect for democratic principles. Following Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023), we also include an additional attribute that captures the income that respondents would enjoy in each country. The inclusion and randomization of this attribute allow us to analyse how citizens prioritize among democratic principles and what kind of trade‐offs they are willing to make by estimating and comparing the monetary value of each principle. In other words, by including income as an attribute, we can analyse variations in citizens' willingness to pay (WTP) to preserve each democratic principle using a comparable and intuitive metric across countries.

Our results indicate that among all the democratic principles considered, free elections are the principle that individuals value the most. Citizens are firmly committed to elections, as they are not willing to forgo this principle even when compensated with high increases in income. Although there is considerable variation across countries, most respondents would only be willing to forgo free elections if their personal income more than doubled. In other words, their price elasticity for free elections is low. Instead, citizens are much more price elastic when it comes to liberal principles related to the rule of law, horizontal accountability or freedom of speech and association. For example, in most countries citizens would be willing to trade off the freedom to demonstrate for a relatively modest 30 per cent increase in their income. Overall, the analysis shows that in many countries a majority of citizens would be willing to forgo liberal principles of democracy in exchange for relatively small increases in their income. This is especially true when these liberal principles are dismantled one by one, suggesting that a gradual or ‘piecemeal’ approach to democratic backsliding is likely to be met with less resistance or contestation from citizens. These findings have relevant implications for our current understanding of backsliding processes, and how they relate to individuals' support for liberal democracy.

Theory

Studies aiming to explain the occurrence and limited public contestation of democratic backsliding have often focused on its demand side, specifically examining how voter attitudes and preferences shape their responses to democratic erosion during elections. In particular, these studies frequently explore how citizens' democratic preferences affect their support for candidates who undermine democratic norms. For instance, recent works by Kaftan and Gessler (Reference Kaftan and Gessler2025) and Wunsch et al. (Reference Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen2025) highlight that while citizens' conceptions of democracy can be inconsistent, voters whose understanding of democracy is grounded in liberal principles are more likely to reject candidates who violate democratic norms. Conversely, voters with a majoritarian conception of democracy are more inclined to support such candidates. Similarly, Lewandowsky and Jankowski (Reference Lewandowsky and Jankowski2023) find that voters with populist and authoritarian attitudes tend to be more tolerant of illiberal candidates.

Other recent studies have combined a demand and supply perspective to explicitly analyse the trade‐offs that voters may face in elections in which candidates advance proposals that undermine democracy. These have focused primarily on the trade‐off between advancing one's own political preferences (or, more generally, partisanship) and safeguarding liberal democracy. Most of this research shows that, in multiple countries, citizens are likely to tolerate candidates who undermine liberal democracy as long as they advance their preferred policy positions (see, e.g., Avramovska et al., Reference Avramovska, Lutz, Milačić and Svolik2022; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2022; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Saikkonen & Christensen, Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023). While citizens may disapprove of undemocratic proposals, actions, or candidates, they are unlikely to punish them at the ballot box if they are ideologically aligned with a particular candidate (Jacob, Reference Jacob2025). This is especially true in highly polarized contexts, which increase the salience and relevance of the partisanship–democracy trade‐off (Svolik, Reference Svolik2019).

Overall, this strand of literature paints a bleak picture. In many cases, citizens are unlikely to withdraw their support from candidates who make proposals that undermine liberal democracy and pave the way for democratic backsliding. This suggests that citizens' support for democracy is weaker or less robust than previously assumed (see also Foa & Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2017). However, these findings stand in contrast to robust evidence showing that support for democracy and liberal values remains high among the citizenry of advanced democracies (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022).

In light of this discrepancy, some recent studies have sought to uncover whether and to what extent citizens are truly committed to democracy – not by analysing their likelihood of voting for undemocratic candidates, but by assessing their willingness to trade off a democratic political system for other socially desirable outcomes. This approach could provide an ultimate measure of the robustness of citizens' commitment to democracy and the extent to which they may tolerate democratic backsliding. Overall, the conclusion of these recent studies is optimistic. Citizens are unlikely to trade off democracy for other socially desirable outcomes, such as greater economic prosperity and welfare (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023) or security (Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023). Thus, support for democracy seems to remain robust, at least in Europe and other middle‐ and high‐income countries. These findings cast doubt on prevailing discourses about a crisis of democracy, at least from the perspective of citizens' commitment to this political system (see also Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2020).

We contribute to these debates by proposing that, in contemporary democracies, citizens may be complacent about democratic erosion because democratic backsliding does not undermine the attributes of democracy they value most. Previous studies have placed a strong emphasis on free and fair elections when examining citizens' support for democracy and their openness to give up on this political system (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023). This is for good reason since free elections are central to modern democracies (Coppedge, Reference Coppedge2020). However, today's democratic erosion most often involves the gradual weakening of other democratic principles, such as the rule of law, media freedom, freedom of association and horizontal accountability (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Boese et al., Reference Boese, Lundstedt, Morrison, Sato and Lindberg2022; Cianetti et al., Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2020; Ding & Slater, Reference Ding and Slater2021).

We argue that it is crucial to go beyond free and fair elections and examine the relative value citizens place on the liberal foundations of democracy that are most often undermined through democratic backsliding, such as the rule of law and freedom of association, and compare them to the value citizens place on free elections. While a majority of citizens may not easily relinquish free elections, they may be more willing to abandon key liberal attributes of democracy.Footnote 1 This may explain why backsliding processes, characterized by the gradual erosion of these principles alongside the preservation of elections, may be acceptable to some citizens. Our main expectation is that while citizens will value each democratic principle positively, none will be valued as highly as free elections. Specifically, we expect that citizens will be more elastic or willing to forgo certain liberal principles of democracy – those at the core of modern democratic backsliding – rather than relinquish free elections.

Prioritizing democratic principles

Our expectation that citizens will place a higher value on free and fair elections and be more elastic in their commitment to other liberal principles often compromised in backsliding processes builds on previous studies of citizens' understandings of democracy (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Shin, Jou, Diamond and Plattner2008), democratic theory (Dahl, Reference Dahl1998) and empirical models of democracy (Coppedge, Reference Coppedge2020). A commonality across these diverse strands of literature is that they all, in one way or another, consider elections the cornerstone of democracy.

While different democratic traditions vary in the importance they attribute to principles such as individual freedoms or checks and balances most emphasize that elections are a necessary and fundamental principle of democracy (Dahl, Reference Dahl1998; L. Diamond & Morlino, Reference Diamond, Morlino, Diamond and Morlino2005; Held, Reference Held1995; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell1999). In other words, modern democracies are unthinkable without free elections. Elections are the primary instrument for fulfilling key democratic functions. Unlike other forms of political participation, such as protests and demonstrations, regular elections provide a formal, structured, and direct channel through which citizens can influence policy‐making and ensure that governments remain responsive to their demands (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini1999). This is partly because elections are the primary mechanism through which citizens hold governments and politicians accountable and can potentially ‘throw the rascals out’ (Morlino, Reference Morlino2009; Przeworski, Reference Przeworski1999).

Citizens should be aware of the importance of elections because of their direct experience with them and the extensive attention and media coverage that this institution receives in democratic societies. Indeed, for many citizens, voting in elections is the most direct, if not the only, way to experience democracy first hand. This crucial link between democracy and elections is reinforced by the extensive attention paid by the media to electoral processes and their ‘horse race’ dynamics, as well as the importance of elections for learning what democracy is through schools (Banducci & Hanretty, Reference Banducci and Hanretty2014; Druckman, Reference Druckman2005). As an example of the ‘popular’ relevance of elections for democracy, consider the frequent – and often misleading – societal discussions linking voter turnout to the legitimacy of this political system (Kirkland & Wood, Reference Kirkland and Wood2017).

The democratic relevance of elections is reflected in citizens' views or conceptions of democracy. Observational evidence consistently shows that when citizens think about democracy, elections are one of the first aspects that come to mind (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Sin and Jou2007). Across different regions of the world, elections and principles related to electoral competition form the basis of how citizens understand democracy (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Williamson and Yeung2024; Fossati & Coma, Reference Fossati and Coma2023; Hernández, Reference Hernández, Ferrín and Kriesi2016, Reference Hernández, Ferrín and Kriesi2025; Norris, Reference Norris2011). This suggests that, among citizens, democracy is unthinkable without elections.

The central role of elections in normative models of democracy, their influence in shaping various democratic outcomes, citizens' direct experience with them, as well as previous findings on citizens' understanding of democracy lead us to anticipate that individuals will regard free and fair elections as the most valuable democratic principle. Hence, we expect that citizens will be firmly committed to this principle of democracy and will not be easily persuaded to forgo elections. In contrast, we anticipate that citizens will attribute lower value to the liberal principles of democracy frequently eroded in backsliding processes, such as media freedom, freedom of association, the rule of law and mechanisms of horizontal accountability. Hence, we expect that citizens will be more elastic in their commitment to these liberal principles and will be more open to forgoing them.

In sum, we hypothesize that citizens will place a greater value on free and fair elections than on other liberal democratic principles often associated with democratic backsliding, such as media censorship, restrictions on the opposition or the weakening of checks and balances (Hypothesis 1).Footnote 2

Research design

To analyse the value citizens attribute to different liberal democratic principles (compared to free and fair elections), their elasticity in their commitment to these principles and the conditions under which they would be willing to forgo democratic principles, we fielded a conjoint experiment in the United Kingdom, Spain, Poland, Hungary, Sweden, Portugal and Israel.Footnote 3 This country selection aims to maximize variation in factors that may influence how much citizens value different attributes of democracy. Specifically, some of the countries have recently experienced backsliding processes of different kinds (Poland, Hungary and Israel), while others have not (e.g., Sweden). In this regard, according to the Regimes of the World measure from the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) project, most of the sampled countries were classified as liberal democracies in 2024, while Israel and Poland were categorized as electoral democracies and Hungary as an electoral autocracy (Nord et al., Reference Nord, Altman, Angiolillo, Fernandes, Good God and Lindberg2025). Furthermore, we included countries where, at the time of the fieldwork, the government was led by a left‐wing party (Spain), a conservative party (the United Kingdom, Portugal, Poland, Sweden), and a radical right populist party (Hungary, Israel). This is relevant because most backsliding processes are carried out by governing parties (Svolik, Reference Svolik2019).Footnote 4 Finally, our sample includes countries with varying levels of economic development and different lengths of democratic experience.Footnote 5

The sample of participants was drawn from the panel of the commercial firm Bilendi, using population‐representative quotas for gender, education, age and region. The samples in the United Kingdom, Spain and Hungary each consisted of 2300 respondents, while in Israel, Poland, Portugal and Sweden the samples included 1500 respondents each. The survey fieldwork was conducted between May and July 2024.

After completing a pre‐treatment questionnaire, respondents were presented with a paired conjoint experiment. They were first introduced to the idea that countries may differ in various characteristics through an example task (see Online Appendix C). In our conjoint, countries could vary along seven dimensions: the freedom and fairness of elections, governmental censorship of critical media (freedom of speech), restrictions on protests and demonstrations by opposition supporters (freedom of association), the extent to which the government abides by court rulings (judicial checks and balances), parliamentary oversight of government decisions (parliamentary checks and balances), the degree to which the government respects the law (rule of law) and the personal income respondents would enjoy in each country (see Table 1). All conjoint attributes were fully randomized with equal probability, without any cross‐attribute constraints. The order of presentation for each attribute in the conjoint table was randomized across respondents but remained fixed for each respondent throughout the conjoint tasks.

Table 1. Attributes and levels of conjoint experiment

Except for the principle of free and fair elections, which we included in the conjoint as a benchmark to compare to the value of other liberal democratic principles, the remaining attributes reflected the liberal principles that are often eroded during democratic backsliding: media freedom (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), checks and balances or mechanisms of horizontal accountability (Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018), the rule of law (L. Diamond, Reference Diamond2015), judicial independence (Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019) and freedom of speech and assembly (Angiolillo et al., Reference Angiolillo, Martin, Marina and Lindberg2024; L. Diamond, Reference Diamond2015; Ding & Slater, Reference Ding and Slater2021). Thus, the conjoint attributes represent the most relevant liberal democratic principles that are often eroded in backsliding processes and the way in which they are most frequently eroded.

The wording of the levels for the conjoint attributes follows recent advances in the observational measurement of citizens' support for liberal democracy. Specifically, the levels for the attributes related to ‘freedom of speech’, ‘judicial checks and balances’, ‘parliamentary checks and balances’ and ‘rule of law’ are based and adapted from Claassen et al.'s (Reference Claassen, Ackermann, Bertsou, Borba, Carlin, Cavari, Dahlum, Gherghina, Hawkins, Lelkes, Magalhães, Mattes, Meijers, Neundorf, Oross, Öztürk, Sarsfield, Self, Stanley, Tsai, Zaslove and Zechmeister2024) proposal to improve the measurement of support for liberal democracy. The wording of the attribute associated with ‘freedom of association’ is based on our own wording but builds on Claassen et al. (Reference Claassen, Ackermann, Bertsou, Borba, Carlin, Cavari, Dahlum, Gherghina, Hawkins, Lelkes, Magalhães, Mattes, Meijers, Neundorf, Oross, Öztürk, Sarsfield, Self, Stanley, Tsai, Zaslove and Zechmeister2024), Medzihorsky and Lindberg (Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024), and Munck (Reference Munck2016), who underline the importance of organized oppositions for democracy. The wording for the attribute related to the freedom and fairness of elections is based on the corresponding item from Neundorf et al. (Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023). Additionally, the wording and specific quantities used in the ‘Monthly income’ attribute are derived from Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023). Although we aimed to closely follow the original wording from these studies, in some cases, we made adjustments to improve clarity and coherence and avoid repetition across attributes.Footnote 6

After being presented with each pair of countries, respondents were asked to choose the country in which they would prefer to live (forced‐choice) and to rate each country on a 0–10 scale, ranging from ‘Very bad’ to ‘Very good’ (rating).Footnote 7 Each respondent completed five choices/rounds, generating 10 observations per individual and resulting in a total of more than 128,000 country‐profile observations.

Results

We analyse the value citizens attribute to different democratic principles and the conditions under which they would be willing to forgo these principles through three sets of analyses. First, we estimate the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of each attribute on the two outcomes considered in this study (choice and rating), which provide an initial indication of how citizens prioritize among the principles of democracy that are most often eroded in backsliding processes. Second, we focus on the rating outcome and estimate the WTP for each attribute. That is, the additional income respondents would require to give up each of these principles. This allows us to estimate and compare how price elastic citizens are with respect to each of these democratic principles. Third, also relying on the rating outcome, we simulate how much it would take for a given society to turn against particular attributes of democracy and to support ‘alternative’ or ‘illiberal’ configurations of democracy.

Citizens' democratic priorities

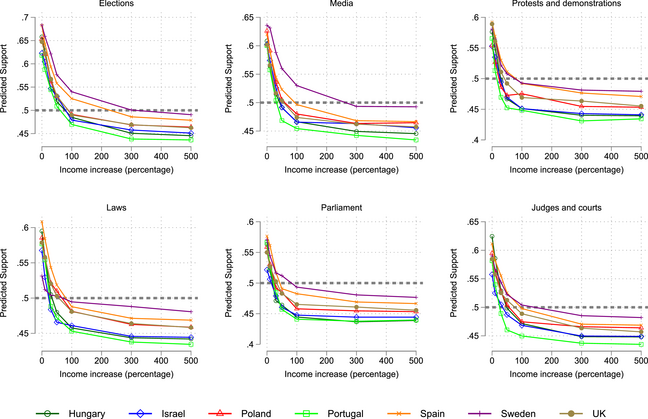

Figure 1 summarizes the AMCEs of each attribute for each country and the two dependent variables considered in this study: choice and rating. All attributes included in the analysis are binary, except for individual income. While income was originally measured as a factor with five categories (see Table 1), we follow Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023) and rescale this variable into two continuous variables. In Figure 1, income is normalized by the country average (we refer to this variable as normalized income). Hence, in this figure, the income coefficient summarizes the effect of doubling the average monthly income that individuals would earn in the corresponding country. Since incomes vary among the countries included in the study, a one‐unit increase in the average income represents different monetary values: 443,000 Ft in Hungary;

Figure 1. Average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for country choice and rating.

Note: All specifications include individual‐specific pair fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the individual level.

If our expectations are correct, we should find that not holding free and fair elections should be more consequential than disregarding any other liberal democratic principle. Indeed, our results show that if a country does not hold free elections, the probability of respondents choosing that country drops substantially – between 40 per cent (in Poland) and 50 per cent (in Sweden). This represents a substantial decline, particularly when compared to the next two most valued democratic principles: media freedom and judicial checks and balances. While still significant, the effect of undermining these principles is consistently smaller; having a government that ignores court rulings or censors the media can, at most, reduce the probability of choosing a country by 30 per cent (Sweden).

Figure 1 reveals that bypassing parliamentary oversight (parliamentary checks and balances) and bending the rules to address pressing social issues (rule of law) also have a negative and significant effect on the probability of choosing a country. Similarly, respondents are less inclined to choose countries where the government restricts the freedom of the opposition to demonstrate (freedom of association). However, the size of these effects pales in comparison to the effect of free and fair elections.

Beyond analysing which country citizens would prefer to live in, we can also assess how the presence or absence of democratic attributes impacts the rating of these countries. In line with the results for the country‐choice outcome, holding free elections remains the most important driver of a country's attractiveness. The negative effect of not holding free and fair elections on country ratings ranges from −1 in the United Kingdom to −1.3 in Sweden (on a 0–10 scale ranging from ‘very bad’ to ‘very good'). Once again, media freedom and government compliance with the judiciary emerge as the second and third most important principles, although their effects are approximately half the size of those of holding free and fair elections.

Figure 1 also shows that the income individuals would enjoy in each country is a relevant factor in shaping respondents’ choices. The results of the first panel indicate that a 100 per cent increase in average monthly income raises the probability of choosing a country by approximately 50 per cent in Sweden, by 70 per cent in Spain, Poland, the United Kingdom, and Israel, by 80 per cent in Hungary and by 90 per cent in Portugal. This operationalization of income does not account for substantive differences in income levels across countries, though. However, when income is measured using an equivalent measure (i.e., $1000 PPP), the results are very similar.Footnote 9 As with normalized income, the results indicate that the positive effect of a $1000 PPP increase is larger in Portugal and Hungary and more limited in Sweden.

Willingness to pay

We now turn to examining whether and to what extent citizens would trade different democratic principles for a higher income. This analysis expands our comparison of the relative importance of each principle by estimating the monetary value of each democratic principle. By doing so, we can assess how price elastic citizens are with respect to each of these principles. Specifically, in Tables 2 and 3, we calculate the average monthly income increase needed to make respondents indifferent between a country that respects a given democratic principle and one that does not. Following Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023), we refer to this as the WTP for each principle. The WTP is based on the ratio of the AMCE of each democratic principle to the AMCE of individual income, estimated using specifications that include individual‐specific pair fixed effects.

Table 2. Willingness to pay using rating estimations and normalized income

Note: Ratios of AMCEs. Standard errors in parenthesis. AMCEs estimated with individual‐level round fixed effects. WTP as a percentage of the average income.

Abbreviations: AMCE, average marginal component effect; WTP, willingness to pay.

*![]() , **

, **![]() , ***

, ***![]() .

.

Table 3. Willingness to pay using rating estimations and $1000 PPP

Note: Ratios of AMCEs. Standard errors in parenthesis. AMCEs estimated with individual‐level round fixed effects. WTP as a percentage of the average income.

Abbreviations: AMCE, average marginal component effect; WTP, willingness to pay.

*![]() , **

, **![]() , ***

, ***![]() .

.

In Table 2, we compute the WTP as the percentage increase in income required for respondents to give up a democratic principle (using rating estimations and normalized income).Footnote 10 The results reveal that respondents across the seven countries are less price elastic in their commitment to free elections than to any other liberal democratic principle. The additional income required to make respondents indifferent between a country that holds free and fair elections and one that does not is consistently higher than the income required for them to forgo any other liberal democratic principle. While the magnitude varies across countries, the value of elections is consistently at least twice as high as that of other liberal principles and, in many cases, significantly higher. For example, respondents in Spain would forgo parliamentary checks and balances in exchange for a 43 per cent increase in income, but it would take a 101 per cent increase to abandon free and fair elections. In the more extreme case of Israel, respondents would give up parliamentary checks and balances for a 13 per cent income increase but would only forgo elections if their income increased by 90 per cent.

The results of Table 2 consistently reveal a lower price elasticity for elections than for any other liberal principle. However, there are also significant differences between countries in the absolute and relative income increases required to give up democratic principles and in the liberal principles respondents in each country are more open to trade for a higher income. First, although respondents are strongly committed to free and fair elections, its monetary value varies substantially across countries. For example, Swedish respondents would require a 197 per cent increase in their income to give up elections, while Portuguese, British and Hungarian respondents would trade off free elections for income increases of 60 per cent, 71 per cent and 72 per cent, respectively. Second, there are also differences when it comes to the second principle of democracy that citizens value most. While in most cases, it is media freedom (four countries), in others it is the rule of law (two countries) and judicial checks and balances (one country). Third, differences also arise when it comes to the least valued liberal principle, both in terms of which principle it is and in terms of its relative value. In Hungary, Israel, the United Kingdom and Spain, parliamentary checks and balances are seen as the least valuable liberal principle, with income increases between 13 per cent and 43 per cent being sufficient to make respondents forgo this principle. In contrast, the least valued principle in Poland and Portugal is the freedom of the opposition to demonstrate, while in Sweden it is having a government that does not bend the law when faced with pressing social issues. In these three countries, income increases between 17 per cent and 29 per cent would suffice to trade off these principles. In any case, a consistent pattern emerges from these results. Citizens are significantly more willing to trade liberal principles than elections in exchange for a higher income. In other words, citizens are much more price elastic when it comes to these liberal principles.

The results of Table 2 also reveal consistent and substantial differences in the WTP for each democratic principle across countries. Generally, Swedish and Spanish respondents appear less open to trading off democratic principles for a higher income. In contrast, Portuguese and British respondents seem to be more price elastic regarding liberal democracy. For these respondents, a 35 per cent increase in income would be sufficient to give up most democratic principles except for elections. Thus, liberal democracy may rest on more fragile ground in these countries, as a significant share of the population may be open to forgoing liberal democratic principles in exchange for relatively small income increases. We return to this question in the next section.

In Table 3, we replicate the analyses using income in $1000 PPP instead of normalized income. Thus, the estimates in the table represent the monthly increases in $1000 PPP required to make respondents indifferent between a country that respects a particular democratic principle and one that does not. This alternative metric makes income increases more comparable across countries in terms of purchasing power. Substantively, the results summarized in Tables 3 and 2 are quite similar. However, these results also highlight cross‐country differences in how much citizens value different democratic principles. For example, when focusing on the freedom and fairness of elections, we observe that Swedish respondents would only trade off this principle if their monthly income increased by $8278 PPP. This contrasts with Hungary and Portugal, where respondents would be willing to trade off elections for a $1700 PPP increase in monthly income. With regard to liberal democratic principles, the use of PPP$ reveals that although these principles are positively valued, limiting freedom of association, eliminating parliamentary checks and balances, or allowing the government to bend laws are relatively ‘cheap’ democratic erosions (in comparison to the value attributed to elections). In most countries, an increase of approximately $1500 PPP in monthly income would be sufficient for respondents to give up these liberal democratic principles.

Support for ‘alternative’ configurations of democracy

Up to this point, we have estimated country‐average preferences for key democratic principles. This has allowed us to compute and compare the elasticity and average monetary value of these principles by calculating the additional income required by respondents to abandon these principles. In this section, we shift the focus to individual‐level estimates to simulate whether and when a majority of respondents would abandon each democratic principle. To this end, we first leverage the 10 country‐profile observations per respondent to estimate the individual marginal component effects (IMCEs) of the conjoint attributes, as proposed by Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023). We then use the IMCEs to calculate the predicted share of citizens who would support a country that forgoes different democratic principles. Specifically, by using individual estimates, we can analyse how each respondent evaluates countries that respect democratic principles versus those that do not while varying the income respondents would receive in the latter.

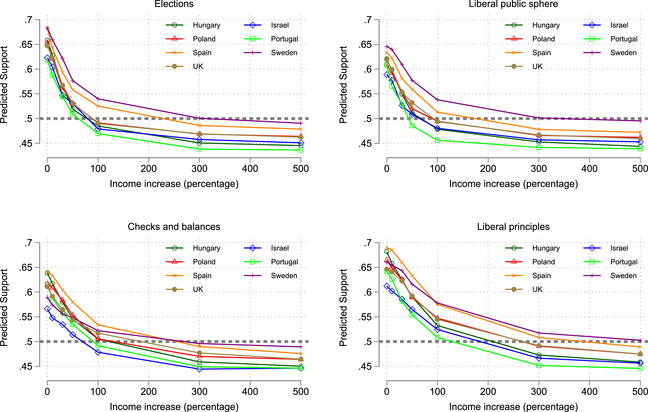

In Figure 2, we estimate the increase in normalized income that residents of a country would have to receive in order for a majority of them to oppose each democratic principle, which would occur at the point where the predicted probability falls below the 0.5 mark (i.e., the point where less than 50 per cent of the population would support this principle). We start by comparing a country that holds free and fair elections with a country that does not, holding everything else constant (top left panel). The results indicate that citizens' initial support for the country that holds free and fair elections is relatively high, reflecting a strong preference for the democratic country. As one would expect, as we improve the country that does not hold free and fair elections by increasing the monthly income that individuals would enjoy, the percentage of respondents who support free and fair elections shrinks. Specifically, a 100 per cent increase in individuals' monthly income would be enough for a majority of respondents to abandon free elections in Hungary, Israel, Poland, Portugal and the United Kingdom.Footnote 11 However, only extremely large increases in income would move a majority of Spanish and Swedish citizens in favour of a society that does not hold free and fair elections (approximately 250 per cent and 300 per cent monthly increases, respectively).

Figure 2. Simulated share of citizens who support each electoral and liberal principle of democracy.

Note: Based on individual marginal component effects (IMCEs) of the conjoint attributes. The y‐axis differs for each democratic principle.

The results for free elections stand in contrast to those for the liberal principles summarized in the remaining panels of Figure 2. For media freedom (freedom of speech) and freedom of the opposition to demonstrate (freedom of association), a modest 50 per cent income increase would suffice for a majority of citizens in many countries to give up these key democratic principles. Similarly, in most countries, a majority would be willing to abandon principles related to checks and balances and the rule of law if their income increased by about 50 per cent. In light of these results, it appears much easier to build a coalition of citizens in favour of dismantling certain liberal democratic provisions than to find a majority willing to give up free and fair elections.

Using the IMCEs, we can go a step further and simulate the conditions under which a majority of citizens in a given country would be open to trading off multiple liberal principles simultaneously. These results are summarized in the top‐right and bottom panels of Figure 3, where we have created theoretically informed bundles of liberal attributes to estimate the income increase required to turn a majority of citizens in a given country against these liberal principles. The top‐right panel focuses on principles related to the liberal public sphere: freedom of speech and freedom of association. The bottom‐left panel covers principles related to the rule of law and checks and balances: government abiding by court rulings, government not bending the law, and government being subject to parliamentary control. Finally, the bottom‐right panel bundles all five liberal democratic principles together. The top‐left panel summarizes again this simulation for free elections, which we use as an informative benchmark.

Figure 3. Support for ‘alternative’ configurations of democracy.

Note: Based on individual marginal component effects (IMCEs) of the conjoint attributes. ‘Liberal public sphere’ includes freedoms of speech and association. ‘Checks and balances’ covers the rule of law, and parliamentary and judicial checks and balances. In the ‘Liberal principles’ panel, we bundle the five liberal principles together.

Regarding the liberal public sphere, the results summarized in Figure 3 reveal that a majority of citizens would accept a society that undermines freedom of speech and association in exchange for an income increase ranging from approximately 45 per cent to 95 per cent (with the exception of Spain and Sweden). Thus, in some countries, a majority of citizens would more readily forgo all these liberal principles related to the public sphere at once than give up free and fair elections. In contrast, the additional income required to turn a majority in favour of a country that undermines most checks and balances at once is significantly higher. In Hungary, Israel, Portugal and Poland, this income increase ranges from 75 per cent to 135 per cent. For the United Kingdom, the required increase rises to 185 per cent, while for Spain and Sweden, it reaches 260 per cent. Hence, in all countries except Sweden, the income increase needed to sway a majority of citizens in favour of a country that undermines all liberal principles related to checks and balances and the rule of law is greater than the increase required to turn a majority against elections. Hence, building a successful coalition to dismantle all these liberal principles related to governmental limits and constraints appears considerably more challenging.

When we bundle together the principles related to checks and balances with those of the liberal public sphere (bottom right panel), this pattern intensifies. In this case, it would be much more difficult to build a coalition of citizens in favour of overturning all these liberal principles at once than it would be to convince a majority to accept elections that are not free and fair. To put it differently, respondents in the seven countries would need a smaller increase in their monthly income to sacrifice free elections than to sacrifice all these liberal principles combined. Therefore, while in a direct comparison every liberal principle by itself pales when compared to free and fair elections, when these liberal principles are considered together they become much more valuable. The most paradigmatic case in this regard is Sweden, where an income increase of approximately 500 per cent would be needed to turn a majority of respondents in favour of a society that does not respect any of the liberal principles considered in this study. We return to this point in the conclusion.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, several countries have experienced democratic backsliding (Angiolillo et al., Reference Angiolillo, Martin, Marina and Lindberg2024), and recent studies show that candidates promoting backsliding are not always punished at the ballot box (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Jacob, Reference Jacob2025; Svolik, Reference Svolik2019). At the same time, other studies suggest that citizens are unlikely to trade off democracy for other desirable considerations (Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023). Thus, it appears that citizens remain strongly committed to democracy (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022), but they may, sometimes, support candidates who undermine this political system. We address this puzzle by proposing that while citizens may be fully committed to certain key attributes of democracy, such as elections, their commitment to other liberal democratic principles may be less steadfast. This may explain the coexistence of high support for democracy – measured generically or through election‐centred definitions – and citizens' openness to support candidates who undermine liberal democratic principles but not elections.

Drawing on recent methodological advances to analyse trade‐offs through conjoint experiments, we fielded a multi‐country conjoint experiment in which respondents were asked to choose between countries that varied in their respect for democratic principles. The results indicate that citizens consistently regard free and fair elections as the most valued democratic principle, one they are unlikely to trade for a higher income. In contrast, citizens are more price elastic regarding their support for other liberal democratic principles, showing a less firm commitment to these principles than to elections. In monetary terms, while an income increase of 35 per cent would be sufficient in most countries to make citizens give up liberal principles like the rule of law or freedom of speech, the income increase required for citizens to give up free and fair elections climbs to a minimum of 60 per cent (in Portugal). Moreover, while the absolute value and price elasticity of each democratic principle vary between countries, the relative prioritization of these principles is very similar across countries. Media freedom (freedom of speech) and judicial horizontal accountability are typically viewed as the second and third most valuable principles, whereas parliamentary horizontal accountability is consistently among the least valued. Finally, it is worth noting that in all countries citizens become less price elastic when these liberal democratic principles are bundled together (e.g., when all attributes that constrain the manoeuvrability of democratically elected governments through horizontal accountability and the rule of law are grouped together (see Figure 3). While in a face‐to‐face comparison every single principle pales when compared to free and fair elections, the income increases required to make respondents forgo bundles of democratic principles rise substantially.

These results can help us better understand the potential role of citizens as a ‘democratic safeguard’ against democratic backsliding. Citizens may tolerate democratic backsliding precisely because the principles undermined in these processes are not the ones they value most. While in all countries citizens are relatively inelastic regarding free elections, their commitment to other liberal principles frequently eroded in backsliding processes is less firm. This greater elasticity when it comes to principles like the rule of law or freedom of association implies that these principles are more vulnerable to erosion, and rulers who undermine them may face less resistance. This empirical regularity that we identify across all countries in our sample suggests that most democracies may be at risk when ruled by leaders with illiberal inclinations.

However, the analysis of the relative monetary value of different bundles of democratic attributes also suggests that undemocratic incumbents may only be successful in eroding liberal democracy when they pursue an incremental, piecemeal approach to backsliding. It may be difficult for would‐be authoritarians to dismantle many liberal principles at once. However, these leaders may be more successful if they implement a piecemeal approach to democratic backsliding. For example, while dismantling or tampering with all horizontal accountability mechanisms at once would likely encounter strong resistance, eroding a single institution that checks government actions (e.g., parliament) may be more readily accepted by citizens.

These results partially align with Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020), who demonstrate that citizens value media freedom and checks and balances in addition to elections. However, our study follows Adserà et al. (Reference Adserà, Arenas and Boix2023) and Neundorf et al. (Reference Neundorf, Dahlum and Frederiksen2023) by moving beyond the ‘candidate choice’ framework, typically used in current studies of democratic backsliding, and adopting ‘country choice’ as the main dependent variable. While this approach involves an abstract and hypothetical decision that respondents may never face in reality, potentially making their choices less reflective of real‐world decision‐making (Findley et al., Reference Findley, Kikuta and Denly2021), it offers several key advantages for studying citizens' support for democracy. First, while candidate choice experiments are well‐suited for mimicking voting scenarios, using candidates to study support for democracy assumes that such support is contingent on candidate characteristics and positions. Consequently, candidate choices only provide an indirect indication of citizens' support for democratic principles. Instead, choosing between countries is likely more revealing of such support, as countries are the natural settings where democratic principles are realized. Second, by presenting respondents with country profiles, we can eliminate partisanship and ideology from the equation. While a candidate choice experiment could theoretically exclude these variables, it would be highly unrealistic for respondents to evaluate candidates with no policy positions or partisan affiliations. Third, the ‘country choice’ approach allows us to include the income respondents would earn in each country as an attribute, enabling us to measure the value citizens place on democratic principles using a straightforward metric that most respondents are likely to be familiar with. Moreover, this feature of our design distinguishes our study from previous works that have measured support for different democratic principles using ‘unconstrained’ questions (Ferrín & Kriesi, Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Norris, Reference Norris2011), allowing us to reduce potential biases related to social desirability. While the use of hypothetical income is subject to other potential biases (e.g., embedding effects) identified in contingent valuation research (P. A. Diamond & Hausman, Reference Diamond and Hausman1994), we would argue that this innovation provides us with a useful metric to assess citizens' commitment to different democratic principles.

Another potential limitation of our study lies, precisely, in the conjoint‐dependent nature of some results. Specifically, the absolute monetary value of democratic principles depends to some extent on the number of attributes included in the conjoint. Our design is well‐suited to comparing the relative value of democratic attributes both relative to one another and across countries. This allows us to examine how citizens prioritize democratic principles, determine their relative value, analyse their openness to forgo these principles and assess cross‐country differences in these patterns. However, the conjoint is less suited to determining the absolute values that citizens attribute to these democratic principles since these could have been different had our conjoint included other attributes that may be important to citizens (e.g., the climate of each country). As such, caution is warranted when inferring the absolute monetary value of democratic principles in the real world based on our results. Yet, we would argue that the analysis of the relative value citizens place on different democratic principles and how citizens prioritize among them can help us better understand the role of citizens as a democratic safeguard in contemporary processes of democratic backsliding.

Furthermore, while we follow previous studies in treating ‘free and fair elections’ as a standalone principle of democracy (see, e.g., Ferrín & Kriesi, Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016), some might argue that citizens may perceive this principle as implicitly encompassing other characteristics of democracy. For example, elections may require other liberal provisions, such as freedom of speech, to be considered truly free. This perception could lead citizens to attribute greater value to this principle. While this is a plausible concern, we contend that the explicit inclusion of these other liberal provisions in our conjoint design (e.g., freedom of speech) helps mitigate this issue. Moreover, for our purposes, it is relevant to assess the extent to which citizens are open to relinquishing standalone liberal principles as well as broader electoral principles. This distinction provides valuable insights into the potential pathways to autocratization and the likelihood of citizen resistance, depending on the specific democratic attributes at stake.

The findings of our study, along with its limitations, open new avenues for further research. First, since democratic backsliding is an elite‐driven process that relies on some level of citizen consent, citizens play a key role in safeguarding democracy against those who seek to undermine it. Given this, future studies on the electoral dynamics of backsliding would benefit from incorporating information on the democratic principles that voters value most into their explanatory frameworks. Kaftan and Gessler (Reference Kaftan and Gessler2025) and Wunsch et al. (Reference Wunsch, Jacob and Derksen2025) are excellent examples that already take into account how citizens ‘understand democracy’. In fact, a potential open question that warrants further scrutiny is whether respondents recognize all the principles included in the conjoint and their violation as a breach of liberal democracy. If some respondents do not know that certain elements – such as legislative oversight or judicial independence – are intrinsic to democracy, their willingness to trade them off may reflect limited awareness rather than genuine preferences. Future research could explore this by linking respondents' choices to their knowledge about democratic principles, potentially shedding light on their openness to forgo democratic principles as function of their sophistication about democracy (Hernández, Reference Hernández2019).

Similarly, given that our study underlines the importance of assessing citizen heterogeneity in support of key democratic principles, a promising path for future research could be to explore how variables that have been at the centre of recent academic debates – such as gender, income and age – shape the value that citizens attribute to different democratic principles. These studies could adopt and adapt methods like estimating the ‘willingness to pay’ for each democratic principle, which may offer more precise insights into how citizens prioritize among democratic principles and how this may deter or increase the electoral punishment of backsliding. Moreover, in estimating the value of democratic principles, future studies could move beyond their monetary value and explore other quantifiable and intuitive metrics, such as safety. This approach could provide an alternative means of assessing the relative value of democratic principles, particularly in regions and countries like, for example, El Salvador that have direct experience with trade‐offs between democracy and security (Meléndez‐Sánchez & Vergara, Reference Meléndez‐Sánchez and Vergara2024). Finally, while our sample includes democracies with varying experiences of backsliding, it covers only a limited range of regime types in a specific world region. According to the Regimes of the World measure developed by V‐Dem, our sample consists of four liberal democracies (Spain, Sweden, Portugal and the United Kingdom), two electoral democracies (Poland and Israel) and one electoral autocracy (Hungary). Future studies should examine whether the patterns of prioritization of democratic principles observed in our study are replicated in different regime types beyond the European context.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Union (ERC Starting Grant 101042292 DEMOTRADEOFF), the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (project PID2022‐137516NA‐I00 COMPROMISE) and the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2024 EPSA Annual Conference, the workshop on ‘Current Directions in Research on Political Support’ at the University of Duisburg, the 7th ‘Jornades de Comportament Politic i Opinió Publica’ at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the 2024 EPOP conference. We thank all the discussants and participants for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank the four anonymous reviewers and the editors of the European Journal of Political Research for their valuable feedback.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data and code to replicate the findings are publicly available in the Harvard Dataverse at ‘Replication Data for: Ferrer, Hernández, Prada and Tomic (2025) The Value of Liberal Democracy: Assessing Citizens’ Commitment to Democratic Principles': https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GA9WBR

Appendix A: Fieldwork details

Appendix B: Attributes and levels

Appendix C: Introductory text and task example

Appendix D: Additional results