As economic and ecological crises increasingly expose the unsustainability of neoliberal capitalism, we need to understand how societies can meet their needs in a socially just and ecologically sustainable fashion. Markets do not ensure universal access to essential goods and services, nor do they incentivize ecologically sustainable behavior independent of economic competition and profit maximization (Reference WrightWright 2018). Capitalist economies also concentrate power and create hierarchical production systems, directly counteracting dynamics of democratic participation and legitimation (Reference Eskelinen and Ada-CharlotteEskelinen 2022). Policies and state intervention may mitigate some of these problems but are limited in their capacity to ensure democracy, which under capitalism is “limited to the political sphere [while] the spheres of economic production, social reproduction, care responsibilities and division of labor are not open to democratic deliberation” (Reference Tiedemann, Benjamin, Heiko, Daniela, Nikolai, Felix and Ada-CharlotteTiedemann et al. 2022: 21). Not coincidently, efforts to create more democratic spaces in the margins of capitalist economies do so by introducing decommodified economic processes, non-hierarchical labor relations, and collective ownership models (Reference Johanisova and StephanJohanisova and Wolf 2012). Thus, democratizing how our economies produce and allocate essential resources requires removing those processes from the sphere of capitalist market competition.

One of the most promising theoretical frameworks tackling this challenge is that of the Foundational Economy (FE). This framework zooms in on essential reliance systems, such as food provision, energy, care work, and housing, to characterize their dominant dynamics and highlight transformative alternatives. It captures how the provision of essential needs is crucial for individual survival and societal functioning, while also being increasingly commercialized, privatized, and made inaccessible under neoliberalism (Reference Barbera, Nicola and AngeloBarbera et al. 2018). FE scholarship also interrogates state- and community-driven practices that socially embed essential reliance systems around democratic participation, non-commercial exchange, social values, and ecological sustainability (Reference Barbera and Ian ReesBarbera and Jones 2020). Numerous social movements seek to transform the FE along these lines, not least the agroecology movement, which aims to reorganize the production, distribution, and governance of food around principles of democratic participation and ecological sustainability (Reference Anderson, Janneke, M. Jahi, Csilla and Michael PatrickAnderson et al. 2021).

As FE scholarship continues to advance, it needs to further strengthen its conceptualization of democratic agency to investigate these practices. Thus far, FE scholars mainly rely on the notion of “active citizenship” to capture a variety of practices (Reference Barbera and Ian ReesBarbera and Jones 2020), whose diversity and scope they rarely interrogate. There is thus a lack of discussion of how economic alternatives can foster collective ownership or participatory decision-making and subvert social norms and power relations. For example, Richard Bärnthaler, Andreas Novy, and Leonhard Plank (2021) argue for an expansion of foundational thinking around dimensions of non-waged labor and socioecological transition, yet their intervention still lacks a consideration of what kind of democratic agency this transition would involve.

This article aims to address this blind spot and advance our perspective on democratic transformations within essential reliance systems by expanding the FE framework with conceptual insights from two other theoretical currents: social reproduction theory (SRT) and the solidarity economy (SE). Both streams are characterized by extensive scholarly and practical engagement and much of the resulting work is strongly interlinked with the FE.

SRT explains that FE systems are essential for the entire economy as they physically and mentally reproduce labor power (Reference Fraser and TithiFraser 2017). The theory emphasizes that socially reproductive labor is highly gendered and racialized, being predominantly performed by women and racially and ethnically marginalized people, whose work is structurally undervalued. It often also takes the form of entirely unpaid domestic labor (Reference Bhattacharya and TithiBhattacharya 2017). By exposing these relations of exploitation and exclusion within the FE, SRT helps identify core dimensions in need of democratization. The SE, in turn, characterizes practices that reorganize economic processes around participatory and deliberative democratic principlesFootnote 1 (Reference LavilleLaville 2010), thus encapsulating the ways foundational reliance systems are democratized and socially embedded. Introducing the two theoretical currents to the FE framework can therefore significantly strengthen its conceptualization of democratic agency: while SRT captures who participates in transforming the FE, the SE captures how this can be done democratically.

In addition to explaining how these concepts and reflections can help expand the FE framework, this article demonstrates their application in the case of the agroecology movement, drawing on original empirical research from the UK. This growing movement seeks to democratize the essential reproductive system of food provision, while also facilitating sociocultural change in local communities and advocating for changes in agrifood policy. The article thus aims to strike up a scholarly trialogue across the FE, SRT, and SE literature by showcasing how their integration can deliver a nuanced understanding of this contemporary movement.

The following section introduces the FE framework and discusses its conception of democratic agency before explaining how insights from SRT and the SE can help alleviate existing blind spots. A second section introduces the UK agroecology movement and explains the applied research methodology. A third section then applies the new conceptual lens by interrogating the agroecology movement's strategies and achievements toward democratizing the food system. Finally, a concluding section reflects on the value gained from integrating FE, SE, and SRT concepts and identifies avenues for future theoretical debate.

The Foundational Economy: A Framework for Economic Democracy

The FE framework offers a way to conceptualize both the dominant capitalist economy and democratic interventions aiming to transform it. The FE represents “the group of heterogeneous activities delivering goods and services which meet essential citizen needs and provide the infrastructure of everyday life” (Reference Froud, Colin, Sukhdev and KarelFroud et al. 2020: 319). It encompasses three dimensions: a “material” dimension that provides daily consumable necessities and resources, such as food, water, housing and energy, a “providential” dimension that offers universal services and transfers for collective welfare, such as health, care and education, and a “discretionary” dimension that includes goods and services whose essential nature is time- and group-dependent, such as furniture or clothingFootnote 2 (Reference Bentham, Andrew, Marta de la, Ewald, Ismail, Peter, Julie, Sukhdev, John, Adam, Michael and KarelBentham et al. 2013). The FE can be distinguished from a “traded” economy of (non-essential) products and services whose primary purpose is commercial profit and a “core economy” of unpaid domestic and community activities.

The FE's structural conditions are contingent upon economic developments and social struggles. During the period of Fordist capitalism, most economies in Europe were characterized by highly regulated FE sectors, resulting in almost universal access to essential necessities through affordable prices or free provision (Foundational Economy Collective 2018). Much of this has changed from the 1980s onward due to the gradual neoliberalization of capitalist economies in the global North and the neoliberal-authoritarian “shock doctrine” implemented across many developing countries (Reference Brenner, Jamie and NikBrenner et al. 2010). As capital concentration, financialization, and trade liberalization increased competitive pressure across FE sectors, numerous governments privatized public services or allowed for them to be outsourced to the less protected voluntary sector. This removal of state control over FE sectors effectively resigned any formal democratic accountability for providing these essential needs.Footnote 3 In many countries, this resulted in price spikes for users, worsening labor conditions for employees, and a gradual loss of social infrastructure. Even where public ownership over the FE was maintained, increasingly market-oriented management requirements and working conditions have taken hold (Reference Plank, Filippo and Ian ReesPlank 2020). Today, a significant share of people's income is spent on essential goods and services,Footnote 4 diminishing their financial security and forcing them to accumulate debt or encounter precarity, while at the same time giving private FE providers, such as retailers, energy or communication companies, major oligopolistic power.

FE scholarship problematizes the socioeconomic precarity and erosion of democratic accountability arising from this process, most of which has been disregarded in neoclassical economic literature (Reference Bentham, Andrew, Marta de la, Ewald, Ismail, Peter, Julie, Sukhdev, John, Adam, Michael and KarelBentham et al. 2013). In response, FE scholars explore social innovations that reject neoliberal profit-seeking in favor of satisfying people's essential needs, producing social and ecological value, and ensuring democratic control over essential reliance systems (Reference Russell, David, Ian Rees and MartinRussell et al. 2022). To that end, the FE is conceived not only as an economic sector but as a moral and political project aimed at a more democratic, egalitarian, and ecologically sustainable economy (Foundational Economy Collective 2018). This does not solely entail non-capitalist provision systems but also involves the social embedding of the economy to either “civilize capitalism” (Reference Heslop, Kevin and JohnHeslop et al. 2019) or else “undermine” it from within (Reference Bärnthaler, Andreas and LeonhardBärnthaler et al. 2021).

Democratic Agency in the Foundational Economy

FE scholars tend to approach the notion of democratic agency within the economy through the concept of “active citizenship.”Footnote 5 In contrast to traditional rights-based citizenship, active citizenship encompasses people's capacity and desire to engage in collective action and exercise democratic control (Reference Barbera, Nicola and AngeloBarbera et al. 2018). The concept draws on ideas of “civic republicanism” that emphasize people's autonomy, mutual solidarity, and collective political struggle. It also draws on notions of “performative citizenship,” which underlines people's ability to claim new rights and capacities for exercising democratic control over economic commons through prefigurative praxis (Reference ChipatoChipato 2021). Active citizenship thus integrates people's ability to influence policy change via representative democracy with their community-driven defense and management of the economy through participatory democratic experiments. Importantly, the concept frames the question of democratic control as a moral entitlement of humanity as a whole, irrespective of scale or scope (Reference Barbera and Ian ReesBarbera and Jones 2020).

Active citizenship is constitutive for a democratic FE by virtue of encompassing a range of practices that enhance citizen control and drive decommodification within essential provision systems. Prominent cases of active citizenship, as studied by FE scholars, include local “mini publics,” such as community juries and citizen assemblies (Reference Heslop, Kevin and JohnHeslop et al. 2019); public–community partnerships, for instance, in the form of municipal cooperatives (Reference ThompsonThompson 2023), radical municipalism (The Care Collective 2020), and trans-scalar civil society networks such as the “Transition Towns” movement (Reference Seyfang and AlexSeyfang and Haxeltine 2012). These practices can be characterized as participatory-deliberative forms of democracy (Reference Cohen, Thomas and JohnCohen 2009), as they involve people in bottom-up decision-making, economic co-production, and policy consultation (characteristic of participatory democracy), while also providing spaces for collective meaning making based on consensual debate (characteristic of deliberative democracy, e.g., Reference RyfeRyfe 2005).

Moreover, going beyond discursive and institutional forms of democracy, active citizenship in the FE generates a form of lived economic democracy that transcends capitalist reality. This allows people to enter a “process of learning to live without hierarchies” and continuously develop their “democratic skills” (Reference Eskelinen and Ada-CharlotteEskelinen 2022: 204). As such, the FE facilitates the “production of a new subjectivity or common-sense and the concomitant emergence of radical forms of citizenship—and its intersection with a material foundation” (Reference Russell, David, Ian Rees and MartinRussell et al. 2022: 9). This constitutes a mutually reinforcing relation between democratic agency and political economic structure, as the FE provides crucial resources and infrastructures for fostering, consolidating, and upscaling further active citizenship (Reference Heslop, Kevin and JohnHeslop et al. 2019). Put differently, a democratized FE is able to generate the necessary material conditions for its own ongoing democratization.

What distinguishes active citizenship in the FE from similar prefigurative frameworks such as the “commons” is its emphasis on state governance as a means of democratizing the economy (Reference Barbera, Nicola and AngeloBarbera et al. 2018). To scale up social innovations and transform economic structures and thinking, FE scholars expect the state to play a significant role, such as by subsidizing community-driven alternatives, placing social obligations on private businesses, and facilitating public ownership and procurement of essential goods and services. Mirroring notions of polycentric governance (Reference OstromOstrom 2010), this multi-scalar and multi-sectoral perspective considers systemic transformations as being simultaneously rooted in “place-based” democratic alternatives and engaged in cooperation across geographical and sectoral boundaries. A foundational approach thus goes beyond “prefigurative lifeboats” (Reference Russell, David, Ian Rees and MartinRussell et al. 2022) and underlines the need for alternative economies to avoid romanticizing the local scale in favor of actively facilitating policy change and interregional solidarity (Reference HansenHansen 2021).

Through the notion of active citizenship, the FE framework offers a uniquely valuable perspective for investigating democratization and decommodification within essential economic sectors. However, its capacity for interrogating specific forms and challenges of democratization retains some shortcomings.

First, the economic spheres and social fault lines associated with the FE do not sufficiently account for dimensions of democratic exclusion and empowerment. Current conceptions of the FE solely encompass the “visible” terrain of waged employment, while the provision of essential needs through unwaged household or voluntary labor is externalized in the “core economy” (Reference Bärnthaler, Andreas and LeonhardBärnthaler et al. 2021). This exclusion is problematic, given both the significance of domestic and third sector labor in reproducing the economy while shouldering the burdens of austerity and the highly gendered and racialized nature of exploitation within these spheres (Reference Bhattacharya and TithiBhattacharya 2017). Since capitalism structurally prevents entire social groups from equal democratic participation by eroding workers’ rights and reproducing gendered or racial hierarchies (Reference Tiedemann, Benjamin, Heiko, Daniela, Nikolai, Felix and Ada-CharlotteTiedemann et al. 2022), economic democracy has to prioritize the empowerment of disadvantaged groups. FE scholarship thus needs to address dynamics of exploitation and exclusion along relations of class, gender, and race within essential reliance systems (Reference Mostaccio, Ian Rees and FilippoMostaccio 2020), including by investigating the domestic sphere and third sector.

Second, the concept of active citizenship may highlight people's collective self-empowerment through democratic participation and deliberation, but it does not sufficiently distinguish between different democratic practices or their relative contributions toward empowerment. While the concept's inclusive definition is helpful for capturing a wide range of innovative practices, it lacks a level of precision necessary for determining the extent to which these practices can democratize economic systems.Footnote 6 Since democracy is not a simple compromise between fixed interests but “the means of a political community to contemplate on its future” (Reference Eskelinen and Ada-CharlotteEskelinen 2022: 198), the ways people build their participatory initiatives informs what alternative economic systems they aim toward. FE scholarship should thus more closely examine the potential and trade-offs of different democratic innovations.

Expanding the Framework around Social Reproduction and the Solidarity Economy

To address the above blind spots, the FE framework can be expanded by drawing on the scholarly writings around SRT and the SE.

Social Reproduction Theory

Scholarship on SRT has been instrumental in highlighting the significance of reproductive labor for the functioning of capitalist economies. Expanding on the Marxist concept of the labor theory of value, social reproduction refers to processes by which people physically and cognitively reproduce themselves and their labor power (Reference FergusonFerguson 2020). Reproductive labor therefore encompasses all activities that facilitate these processes, including the provision of food, water and housing, medical support, care, cleaning, education, and emotional labor. These forms of labor are performed across all economic sectors, including through public welfare provision, commercial goods and services, voluntary associations, and charities (Reference Bhattacharya and TithiBhattacharya 2017). Most of the FE is thus based on reproductive labor, except for transport, communication, and energy-provision. Indeed, it is their reproductive function that makes many sectors “foundational” in the first place.

Most distinctively, reproductive labor is also performed unpaid in the household. Many economists, including FE scholars, separate domestic labor from the “regular” economy as it is not directly involved in the provision of marketable goods and services (Reference FergusonFerguson 2020). However, as various authors explain (Reference Bhattacharya and TithiBhattacharya 2017; Reference Fraser and TithiFraser 2017; Reference JaffeJaffe 2020), reproductive labor ultimately (re)produces people's labor power itself, thus being essential not only for individual survival but for economic activity as a whole: “Unwaged social reproductive activity is necessary to the existence of waged work, to the accumulation of surplus value, and the functioning of capitalism as such” (Reference Fraser and TithiFraser 2017: 23).

Capitalism is thus rooted in both a productive and reproductive sphere whose relation is historically contested through “boundary struggles” taking place at and over the separations between market economy (including between exploitation and expropriation), politics, civil society, nature, and familyFootnote 7 (Reference FraserFraser 2022). Those boundaries are deeply imbued with gendered and racialized power relations. Both in the household and beyond, reproductive labor is predominantly performed by women and racially and ethnically marginalized people at low pay (Reference Bhattacharya and TithiBhattacharya 2017). Boundary struggles are thus inherently tied to social inequalities, as well as closely interwoven with struggles of class (Reference FraserFraser 2022).

Under Keynesian economic policy, governments in Europe and North America provided many reproductive services through public provision systems, largely involving women's labor, which have since become increasingly privatized and financialized under neoliberalism, leading to a dual commodification and domestication of social reproduction (Reference BakkerBakker 2007). As explained above, this has resulted in a social “impoverishment” and erosion of a “civic infrastructure” that could retain some degree of democratic accountability over reproductive labor conditions (Reference Barbera, Nicola and AngeloBarbera et al. 2018). This ultimately undermines the stability of capitalism itself, as “the logic of economic production overrides that of social reproduction, destabilizing the very processes on which capital depends” (Reference FraserFraser 2016: 103). The potential severity of this became evident during the pandemic, whose intensity was amplified by years of budget cuts targeting reproductive sectors such as health, care, and education (Reference Pokhrel and RoshanPokhrel and Chhetri 2021). Due to the implementation of lockdown measures and closure of schools and care facilities, reproductive functions such as cooking, childcare, and education were pushed almost entirely into the private household, thus becoming the predominant domain of women's unpaid labor even more than before the pandemic (Reference Yavorsky, Yue and AmandaYavorsky et al. 2021).

By rendering visible the scope of reproductive labor and the interrelation of different forms of exploitation and exclusion, SRT provides an important perspective on how neoliberal capitalism fails to provide economic democracy. By drawing on SRT, FE scholarship can explain how processes of commodification and austerity not only erode the working conditions in FE sectors, but also deepen social inequalities at the expense of women and marginalized people (see Reference Bruff, Stefanie, Aida A. and JacquiBruff and Wöhl 2016; Reference Hajek and BenjaminHajek and Opratko 2016), thus lowering their capacity for engaging in democratic participation. Consequently, SRT also enables FE scholars to understand why and how boundary struggles by those disadvantaged groups involve developing democratic innovations and engaging in active citizenship across the FE. Initiatives such as mutual aid networks, food banks, social clinics, and housing activist groups are often predominantly run by women who politicize reproductive work and “raise broader questions about the nature of, and responsibility for, social provisioning” (Reference BakkerBakker 2007: 547). In doing so, they pave the way for shifting social reproduction onto a foundation of collective solidarity that is no longer grounded in traditional power and labor relations (Reference Bergeron and StephenBergeron and Healy 2013), but represents a community-based alternative to the capitalist FE (Reference ArampatziArampatzi 2018). As such, these initiatives are directly involved in “struggles in, around and (in some cases) against capitalism itself,” which, if coordinated, could “envision new configurations . . . of the relation of economy to society, nature and polity” (Reference FraserFraser 2022: 34). In that regard, SRT also offers a critical assessment of such democratic initiatives themselves by highlighting to what extent they subvert or reproduce societal power inequalities between participants.

The Solidarity Economy

The SE framework outlines the contours of a democratic and socially embedded alternative to neoliberalism, like the FE. It is framed around principles of democratic participation, material redistribution and reciprocity, horizontal labor relations, community ownership, and ecologically sustainable production (Reference LavilleLaville 2010). Practices associated with the SE include mutual aid networks, alternative currencies, cooperatives, open-source networks, and community sharing platforms. By building alternatives to capitalist markets they go beyond the traditional “social economy” of non-profit associations and social enterprises (Reference NardiNardi 2016). Importantly, the SE combines an economic dimension of prefiguring non-market systems of production, distribution, and social reproduction with a political dimension of building non-hierarchical, participatory democratic structures and supporting efforts toward policy change (Reference LavilleLaville 2010).

As such, the SE encompasses the radical democratic and non-capitalist innovations that define much of the FE. Yet, while the FE framework also views the state as central in scaling up those innovations, literature on the SE underlines the autonomy of radical innovations from both markets and state authority (Reference Laville and PeterLaville 2015). Thus, whereas the FE relies on a broad range of activities characterized as active citizenship, including institutional engagement and public sector control, the SE primarily reflects notions of performative citizenship by relying on alternative everyday practices to prefigure new forms of living.

At the same time, the SE's approach does not romanticize local escapism, but rather emphasizes the inherent challenges and tensions of expanding social innovation. While other theories often view systemic transformation as a process of growing innovations beyond their economic niche (Reference Seyfang and AlexSeyfang and Haxeltine 2012), the SE emphasizes the ability of local alternatives to build “infrastructures of dissent” (Reference SearsSears 2014) capable of supporting transformative social movements and political struggles at scale (Reference ArampatziArampatzi 2018). Indeed, the SE literature distinguishes between different forms of expansion and their respective democratic benefits and challenges.Footnote 8 This includes upscaling, by which local innovations grow their organizational capacities and engage with institutional actors and public procurement; out-scaling, which involves replicating innovations in other locations or sectors; and deep-scaling, by which innovative projects forge stronger bonds with local communities through politicization and grassroots learning (Reference NicolNicol 2020; Reference Ribera-Almandoz and MònicaRibera-Almandoz and Clua-Losada 2020). Upscaling can risk undermining the SE's democratic ambitions by introducing pressures to become more economically efficient or creating dependencies on public or NGO benefactors at the expense of democratic participation and accountability (Reference Laville and PeterLaville 2015). Out-scaling and deep-scaling are more effective at developing horizontal and decentralized structures that can expand economic alternatives while retaining a high level of participation and accountability (Reference ShivaShiva 2021).

By drawing on the SE's notions of performative citizenship and scaling, FE scholarship can diversify its conception of active citizenship, enabling it to more clearly differentiate between activities aimed at facilitating and expanding economic democracy. Given the tendency of governments to externalize the effects of austerity via voluntary labor and to commodify alternative values, such as “community resilience” and “sustainability” (Reference McCabe, Mandy and RobMcCabe et al. 2020), FE scholars need to be highly critical in their assessment of state policies that ostensibly embrace social innovations. The SE literature offers ways to conduct such a critical assessment by explaining how and to what extent different alternative practices achieve their democratic and non-commercial ambitions.

Case and Methods

Expanding the FE framework to include notions of SRT and the SE allows for a more nuanced examination of grassroots initiatives engaged in democratizing essential reliance systems. The rapidly growing agroecology movement is a prime example of such engagement within the system of agriculture and food provision.

Agroecology refers to the holistic integration of ecological agricultural practices with principles of a democratic participation and social justice (Reference Anderson, Janneke, M. Jahi, Csilla and Michael PatrickAnderson et al. 2021). It is deeply intertwined with the paradigm of “food sovereignty,” by which movements of peasants, food workers, and indigenous peoples, largely in the Global South, have framed their struggle to regain control over their own food systems, repel large agrifood businesses, and engage in ecological land stewardship and food provision (Reference Levidow, Michel and GaetanLevidow et al. 2014). To put such ideals into practice, agroecological organizations reorganize the production, distribution, and governance of food around democratic participation, horizontal labor relations, local and indigenous knowledge, and socially inclusive ownership and consumption models. They strive for market autonomy and social value creation as opposed to competing for profit, and champion ecological sustainability and feminism (Reference Anderson, Janneke, M. Jahi, Csilla and Michael PatrickAnderson et al. 2021). As such, agroecological organizations intersect with the FE and SE while also engaging in boundary struggles over the commodification, reproductive function, and ecological sustainability of the food system.

Agroecological organizations can take a variety of forms: Food councils are institutional bodies comprised of different stakeholders that enable citizens to democratically influence their municipal food policy (Reference MooneyMooney 2021). In community-supported agriculture (CSA) food producers and local households collectively share the costs, risks, output, and often the labor of agricultural production (Reference HinrichsHinrichs 2000). This enables them to establish short and sustainable supply chain systems in relative autonomy of the commercial food system. Many of these initiatives can collaborate via local food partnerships or larger networks to engage in knowledge exchange, collective action, and policy advocacy.

This article draws on a qualitative investigation of agroecological networks in the UK, in particular organizations involved in the promotion of sustainable food provision. It focuses on farmer unions such as the Landworkers Alliance (LWA) and Organic Growers Alliance (OGA), which advocate for the interests of small sustainable food producers in general (LWA 2023c; OGA 2022), and the more specialized CSA Network and Social Farms and Gardens (SF&G), which facilitate mutual exchange, support, and institutional representation for CSAs and care farms (CSA Network 2021a; SF&G 2022). The investigation also includes the Sustainable Food Places network and Food Foundation, which connect local food policy councils and food partnerships (Food Foundation 2022b; Sustainable Food Places 2022a).

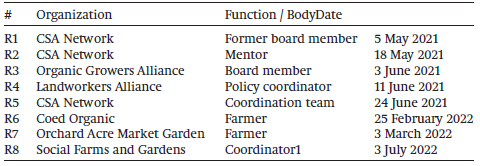

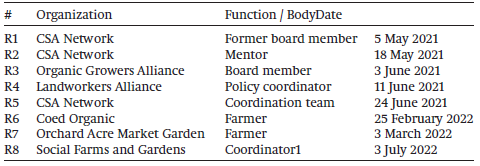

The research combines qualitative document analyses of around 130 publications and online posts written by the selected organizations, eight hour-long semistructured expert interviews with network representatives and local farmers (table 1), and participant observation at network gatherings and events, nine online and one in-person.

Table 1: Interview Respondents

Coding the documents revealed the organizations’ conceptions of agroecology, their grievances with the dominant agrifood system, democratic practices, transformative objectives and policy claims, and their encountered achievements and challenges. Interview questions revolved around the governing structure of the respondents’ organizations, their short- and long-term aims, practices, policy claims, successes and failures, and their visions for a democratized agroecological food system. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, followed by a qualitative open coding analysis mirroring the document analysis. Participant observation took place alongside the interviews and resulted in written field notes that captured both the content of participants’ discussions (focusing on goals, achievements, and challenges) and observations about their practices and mutual engagement.

Agroecological Organizations in the UK

Agroecology and the Solidarity Economy: Democratizing the Food System

Many agroecological organizations in the UK explicitly aim to empower people toward gaining more control over the food system, thus enhancing its democratic legitimacy and ownership. This is reflected both in their own participatory practices and their efforts to involve communities in food policymaking.

The CSA Network considers the practice of CSA to be “one of the most radical ways that we can re-take control and ownership of our food system” (CSA Network 2023). As CSA members co-finance farming operations, they can gain the ability to decide collectively how their own food provision is organized, for instance, what crops are planted and how food is distributed (CSA Network 2018). As such, CSA can involve a form of performative citizenship characteristic of the SE, as the model prefigures participatory democratic, non-hierarchical, and non-market-based forms of food provision. That said, more than half of UK CSAs self-identify as “farmer-driven” rather than “community-driven” (R5), indicating notable differences regarding whose control and ownership they seek to strengthen.

Similarly, the Sustainable Food Places network aims to change the food system in part by “taking a strategic and collaborative approach to good food governance and action [and] building public awareness, active food citizenship and a local good food movement” (Sustainable Food Places 2023, emphasis added). The network organizes local food partnerships (including food councils), bringing together producers, retailers, activists, and consumers to influence food policy and reorganize local food provision. Food councils in particular can act as deliberative mini publics by involving these actors in collaborative discussion and planning, whereas other food partnerships are more pragmatic and professionalized. For instance, “Food Cardiff” encompasses 95 organizations, including farms, retailers, hospitalities, and research institutes, who aim to promote local food cultures, organize public procurement, and battle food poverty within the city (Food Cardiff 2021). Although most food partnerships involve commercial businesses to some extent, their efforts contribute to reducing market pressures and enhancing community engagement and control over the food system, thus helping to foster active citizenship.

The LWA is the most vocal about its democratic ambitions. As a member of the international food sovereignty alliance La Via Campesina, one of its key goals is to create a democratic food system: “Control over the resources to produce, distribute and access food should be in the hands of producers, communities and workers across the food system. Civil society should be at the centre of policymaking, with the power to shape the way the food system functions and influence the policies and practices needed to transition to a just food system” (LWA 2023c).

To facilitate a democratic transformation at scale, agroecological organizations connect with and support one another across territories, thereby engaging in out-scaling. The CSA Network, SF&G, and Sustainable Food Places bring together hundreds of local initiatives at the national level and facilitate mutual knowledge sharing and public promotion to spread their innovative practices. Although the UK's roughly 220 CSAs represent only 0.1 percent of the country's agricultural system (CSA Network 2021b), their volume has doubled since 2020, guided primarily by the CSA Network and SF&G (R5, R8). Similarly, Sustainable Food Places has set up food partnerships in 82 municipalities (Sustainable Food Places 2022b) while the Food Foundation runs nationwide campaigns to incentivize businesses, public and community organizations to increase their distribution of vegetables (Food Foundation 2022a).

This expansion helps diffuse participatory and deliberative democratic food practices and create an infrastructure of dissent capable of supporting political engagement, yet it is not necessarily rooted in enhanced democratic participation itself. The CSA Network, for instance, is constituted as a typical association, governed by an elected board and a coordinating staff. While local members can deliberate at annual assemblies, the board and coordinators run all daily operations (R5). Although the network attempted to incentivize more independent participation at the regional level, only one regional network was founded in Wales and quickly grew dormant again (R2). This development reflects both a trend toward organizational professionalization and a lack of bottom-up engagement by local members, who lack the time and capacities to engage in regular democratic participation beyond their own enterprise. As one former board member explains: “It's an interesting example of a democratic organisation in that people are just really happy it exists but don't want to take on too much responsibility themselves. And again, a lot of the people involved in CSAs have a lot going on in their local CSAs” (R1).

On the other hand, the LWA is even more professionalized while also offering a higher degree of democratic participation and deliberation. It is run as a labor union with local and regional branches, whose members can elect a national leadership, which in turn hires administrative staff. At the same time, regional representatives are highly engaged (R4), local members can participate in thematic working groups, and local delegates can debate the organization's overall strategy in a national “organisers assembly” (LWA 2023a). These experiences highlight an inherent tension between facilitating effective organizational governance at scale while also ensuring broad democratic participationFootnote 9—a tension that different organizations are bound to address differently depending on their internal conditions, resources, and members.

In contrast to more strictly prefigurative approaches to economic democracy, national-level agroecological organizations in particular call for state intervention in the food system in favor of material redistribution and environmental sustainability. In doing so, they exhibit forms of active citizenship that involve the upscaling of agroecological principles in a way that is more particular to notions of the FE rather than the SE. Most of their claims revolve around gaining more subsidies and public procurement contracts for small producers and community initiatives (CSA Network 2021a; LWA 2019). Some organizations also advocate for better public nutritional education to promote healthy diets and combat food waste (Reference Bellamy and TerryBellamy and Marsden 2020). Others are primarily concerned with the lack of ecological expertise in agricultural education, most of which focuses primarily on industrial food production without training people to farm sustainably (Food Farming and Countryside Commission 2020). Addressing this blind spot is considered crucial for both promoting agroecological farming as a career (R2) and helping agroecological farmers reach a level of professionalization necessary to feed larger populations and offer decent wages rather than depend on volunteers: “When you get to a certain scale . . . that makes the job a little bit more skilled. It involves more training or more direct skills around working with machinery and makes it a little bit less accessible to people and volunteers just from a health and safety point of view” (R6).

Consequently, agroecological organizations such as LWA and the CSA Network develop training courses, act as mentors, and publish handbooks for new farmers, including on such topics as organizing internal democratic processes and fostering community involvement (CSA Network 2018). As such, they engage in deep-scaling by spreading a “new subjectivity or common-sense” (Reference Russell, David, Ian Rees and MartinRussell et al. 2022) among professional stakeholders and the general public, intended to fuel a mutually conducive cycle between active citizenship and economic democracy.

Pushing the Boundaries of Social Reproduction in the Food System

By integrating core principles of environmental sustainability, social equality, democratic sovereignty, and independence of market imperatives, agroecological organizations engage in boundary struggles against the capitalist, hierarchical, and extractivist nature of the food system in a way that aims to transform “the relation of economy to society, nature and polity” (Reference FraserFraser 2022: 34). Unlike food banks or charities that simply alleviate the failures of the neoliberal food system without challenging its underlying power relations (Reference Lorenz, Stefan and KatjaLorenz 2011), agroecological organizations aim to transform food provision into a means of democratic empowerment and social inclusion.

Much of the work done by agroecological organizations expresses feminist and anti-racist ideals and directly aims at tackling gendered, racialized, and classed forms of disempowerment. This is especially true of the LWA, which has dedicated working groups called “Women and Diverse Genders in Forestry and Landwork” and “Racial Equity, Abolition and Liberation in Landwork” that aim to boost the inclusion of women, diverse genders, and racially marginalized people in agriculture. By involving members of those groups in knowledge exchange, mutual solidarity, and awareness raising, LWA is thus trying to tackle social inequalities via enhanced democratic participation (LWA 2023b, 2023d). Some leading members of LWA are engaged in Granville Community Kitchen in London, whose aim is to empower women, especially from low-income backgrounds, by becoming organized around food justice (Reference Woods and Josina CallisteWoods and Calliste 2020). The LWA also co-organizes the Jumping Fences project, which conducts research into the experiences of British farmers from racially marginalized groups and has exposed systemic problems with racial discrimination and isolation in UK agriculture, while also pointing toward opportunities for greater social justice (Land in Our Names et al. 2023). LWA's work also reflects a class-based perspective, as it organizes small agroecological farmers and land workers against large agri-industrial producers calling for better working conditions in the agriculture sector (LWA 2021) and mandatory community consultations whenever significant land holdings are to be sold (LWA 2019).

These calls for social equality reach far beyond the agrifood system, underlining the agroecology movement's engagement in boundary struggles throughout the sphere of social reproduction. To fight food insecurity, many agroecological organizations call for material changes across the whole economy, such as a general reduction of income inequality. A member of the CSA Network, for instance, demands that government contribute to “making the income gap smaller so that people can afford to buy good food and have the resource to do so” (R5), while the Food Foundation demands a general raise in wages and benefits to “ensure that price isn't a barrier to choosing sustainable options, including for people on low incomes” (Food Foundation 2022b: 15).

To what extent agroecological organizations themselves manage to achieve a significant level of diversity among their participants is rather uneven, however. Women represent a majority in most agroecological organizations, making up around 74 percent of CSA participants (Soil Association 2011: 24) and 54 percent of LWA's members (LWA 2020), thus creating a considerably higher level of gender-diversity than UK agriculture in general. On one hand, this creates a risk of reproducing women's traditional responsibility for reproductive labor (around food provision), but on the other hand, it allows women to politicize these activities, turning them into a form of democratic empowerment through collective action (Reference BakkerBakker 2007). Conversely, agroecological organizations tend to struggle with being inclusive toward people with lower income and cultural capital. Particularly in CSAs, participation involves financial commitment and requires time and nutritional knowledge (Reference Verfuerth and Angela SandersonVerfuerth and Bellamy 2022), thus being accessible mostly to people from educated middle-class backgrounds, who also represent a disproportionately white majority. In LWA, 90 percent of members are white and 77 percent are from higher education backgrounds (LWA 2020).

This exclusivity demonstrates a lack of alignment between different boundary struggles, as the agroecology movement manages to subvert some dimensions of domination while reproducing others. Thus, the movement's ability to democratize the food system remains limited, as long as its new forms of democratic control and ownership retain many of the structural barriers that make the traditional food system—and the wider sphere of social reproduction—undemocratic and exploitative in the first place. Agroecological organizations are keenly aware of this problem, especially in the case of CSA. Despite the model's inherent self-reliance, members of the OGA thus call on government to help make it more accessible: “An area where support from government would be really helpful is to allow people from lower incomes to access the benefits of CSA” (R3).

Ultimately, agroecological organizations in the UK are strongly committed to uniting different boundary struggles of class, gender, race, and nature and envisioning “new configurations, not ‘merely’ of economy, but also of the relation of economy to society, nature and polity” (Reference FraserFraser 2022: 34). As such, they are working toward democratizing the food system in a way that actively accounts for the gendered, racialized, and classed forms of inequality and exploitation inherent in the system. However, their ability to put these ambitions into practice remains constrained by structural barriers of the agricultural system and their own limited reach and accessibility.

Conclusions

The aim of this article has been to expand the FE framework to develop a more nuanced examination of how grassroots social innovations seek to democratize essential reliance systems. Drawing on conceptual reflections of SRT and the SE, it has addressed blind spots in the Foundational Economy literature to strengthen notions of democratic agency through active citizenship. Social reproduction defines what makes essential reliance systems “foundational” in the first place, thus making the gendered and racialized hierarchies and boundary struggles of reproductive labor key arenas of democratization within the FE. The SE, in turn, encompasses the range of participatory and non-capitalist forms of prefiguration (performative citizenship) by which the FE can democratize the economy. In establishing this trialogue across scholarly currents, the article builds on previous interventions and, hopefully, encourages further in-depth exchange, conceptual reflection, and empirical research.

The article has also demonstrated the value of this conceptual integration by characterizing the UK agroecology movement using the expanded FE framework. Agroecological organizations are deeply embedded in the FE and SE, fostering active citizenship in general and performative citizenship in particular, as they build non-hierarchical, participatory, and deliberative democratic structures, while also seeking to overcome capitalist market pressures and change agrifood policy. Their democratizing potential is also reflected in their efforts to subvert classed, gendered, and racialized inequalities in the agrifood system in favor of more socially just and ecologically sustainable systems of social reproduction.

Unlike individual “prefigurative experiments in commoning [that] evade the necessity of confronting capitalist power” (Reference FraserFraser 2022: 100) or fall into the “local trap” of disregarding multi-scalar political dynamics (Reference RussellRussell 2019), agroecological organizations pursue various strategies for ambitious economic and political change at scale. Collaborating across larger networks, they seek to spread their innovations with economic democracy through different scaling practices. On the other hand, agroecological organizations also struggle with overcoming social hierarchies between members and facilitating significant democratic participation beyond the local scale.

Ultimately, agroecological organizations provide an effective demonstration of a larger point: Efforts to democratize the FE are closely intertwined with scaling SE practices and contesting hierarchies of social reproduction, which involves myriad challenges. Conversely, the FE, SE, and SRT not only inform the democratizing qualities of socially innovative organizations but also outline the strategic field in which they operate. Embracing the FE, SE, and SRT thus holds major opportunities for a wide range of transformative organizations and prefigurative projects to build a wider and more proactive movement for economic democracy.