Introduction

Can policymakers still deliver ambitious policy goals, such as reasserting the role of the state in contexts where liberalization seems the only game in town? And if so, what are the conditions under which such ambitious policymaking may come about? We explore these questions by focusing on the case of collectively-governed markets, i.e. institutional arenas organized around non-state actors’ self-governance (typically trade unions and business associations) that had long been considered as shielded from both “market liberalization” and state intervention (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Thelen and Kume Reference Thelen and Kume1999; Thelen Reference Thelen, Iversen, Pontusson and Soskice2000). Yet, significant changes in collectively-governed markets over the last three decades challenge their depiction as institutional equilibria. Changes initially took the form of liberalization (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2011; Howell Reference Howell2019) but more recent evidence shows movements in the opposite direction, namely increased government intervention. Pursued primarily by left-wing governments, interventions have been shoring up collectively-governed markets when non-state actors’ self-governance alone proved unable to do so (Busemeyer et al. Reference Busemeyer, Carstensen and Emmenegger2022; Durazzi and Geyer Reference Durazzi and Geyer2020; Eichhorst and Marx Reference Eichhorst and Marx2011, Reference Eichhorst and Marx2021; Ibsen and Thelen Reference Ibsen and Thelen2024). In this paper, we propose a theorization of and empirical investigation into when and how center-left governmentsFootnote 1 intervene in collectively-governed markets.

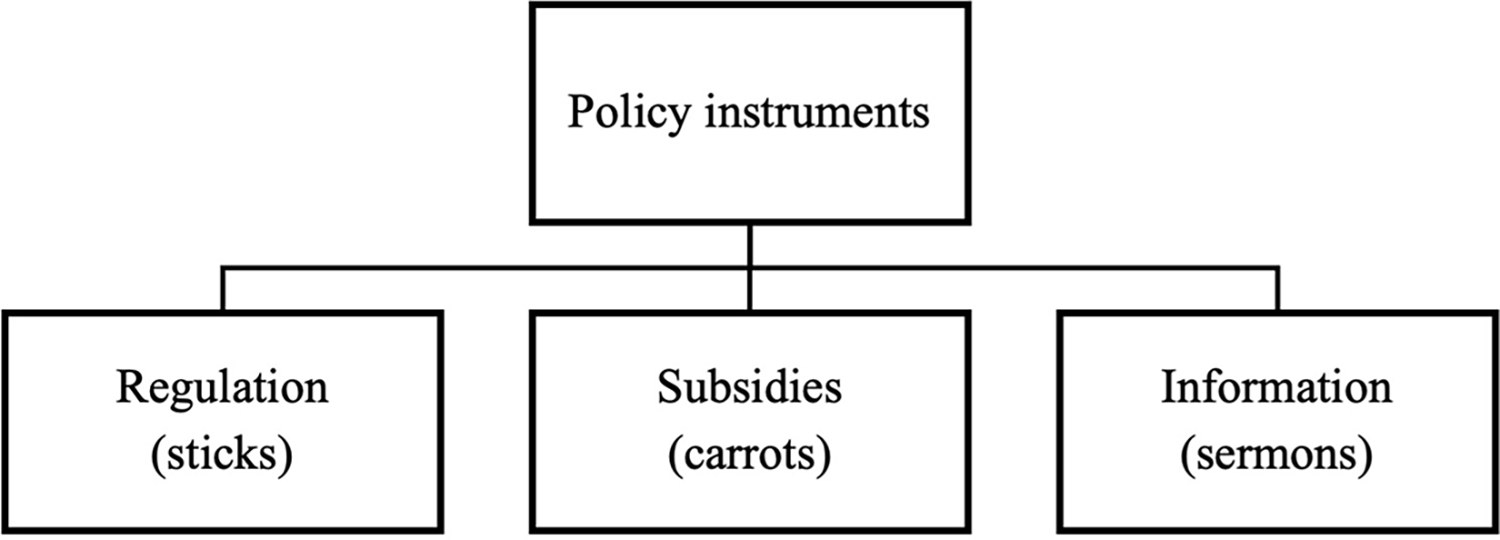

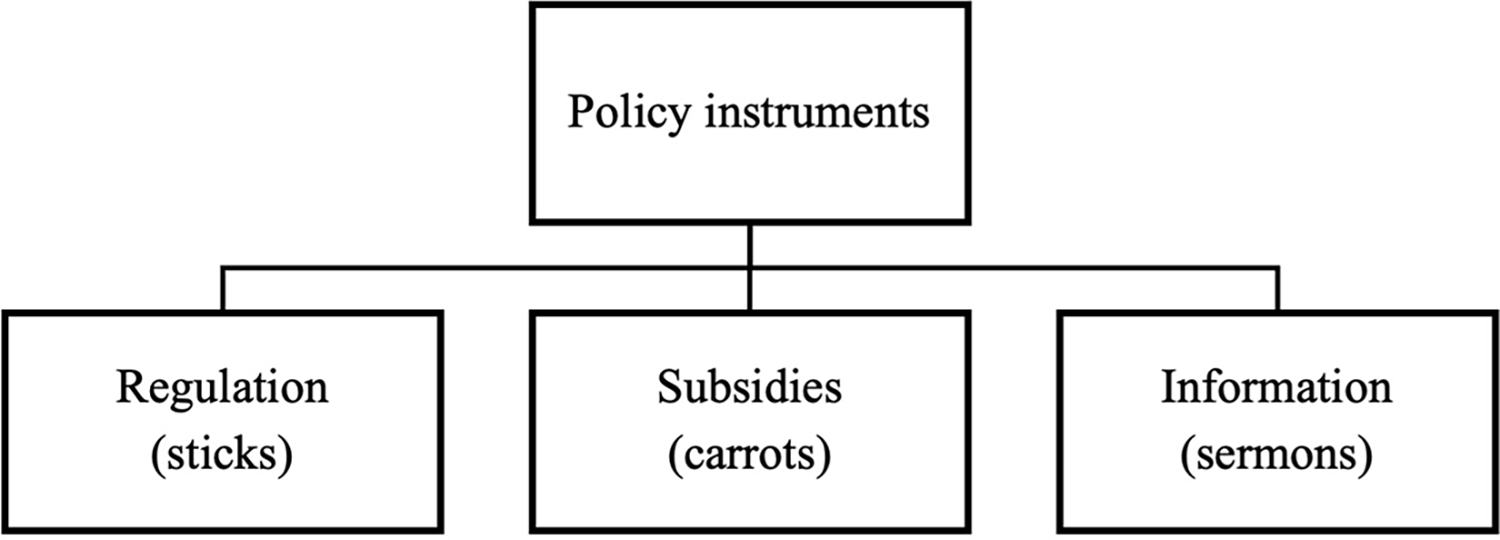

In doing so, we bring together insights from Comparative Political Economy (CPE) and public policy. We construct a typology of policy instruments that are available to governments to shore up collective markets and study the politics of policy choice. We build on Vedung’s (Reference Vedung, Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung1998) seminal definition of a hierarchy of policy instruments ordered depending on the authoritative force involved in governance efforts. We distinguish the following instruments: regulations (sticks), the most coercive measure, consisting of rules and directives mandating how rule-takers should act; economic policy instruments (carrots), which are less coercive but involve the handing out or taking away of material resources, making certain courses of action cheaper or more expensive; information (sermons), which are the least coercive and involve the communication of arguments to convince actors to undertake certain actions. We then embed this threefold classification of policy instruments in a CPE framework to outline the political-economic conditions through which left-wing governments can opt for different instruments. We argue that the choice of a more or less coercive policy instrument depends on the extent to which the constraints that normally frustrate state intervention give way, opening the possibility for reform (Keeler Reference Keeler1993).

Adapting Keeler’s conceptualization of the opening of a window for reform to a coalitional and time-conscious view of the political economy, we conceptualize two types of resources for policymakers aiming to innovate politically: coalitional and contextual. Akin to power resource theory (PRT) (Korpi Reference Korpi2006), the coalitional resources available to left-wing governments are the coherence of preferences, with its traditional ally in interest representation, labor unions (alignment). The contextual resources relate to the timing of policy intervention, namely the socio-economic context that may gather momentum behind a policy or, conversely, militate against it (timing). We argue that: if left-wing governments and unions are aligned and the timing is favorable, the instrument chosen will be the most coercive (i.e., stick). If left-wing governments and unions are aligned but the timing is not favorable, the chosen instrument will have less coercive power (i.e., carrot). Lastly, if left-wing governments and unions are misaligned but the timing is favorable, the chosen instrument has the lowest coercive nature (i.e., sermon). A comparative case study of wage setting and vocational education and training (VET) policy in Germany – which we argue represent two least likely policy areas nested within a least likely case (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975) – provide support for the proposed approach.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section The rise, fall, and return of the state in comparative political economy reviews the approaches in comparative political economy to the topic of state intervention and partisanship throughout history and across policy areas. Section Theorizing the Left’s intervention in collective markets presents the theoretical framework through which we systematize types of state intervention. Section Research design and data collection explains the research design of the paper and the methods employed. Section Analysis delves into the evidence to demonstrate the usefulness of the typology, presenting the processes of state intervention in VET and wage setting in Germany. Finally, section Discussion and conclusion offers some concluding remarks and proposes the two variables of timing and coalitional support as the key determinants of types of state intervention.

The rise, fall, and return of the state in comparative political economy

The role of the state has been a central yet fluctuating theme in CPE. Early studies on models of capitalism, such as the influential framework by Shonfield (Reference Shonfield1965), placed the state at the center of economic organization, particularly in Europe. However, by the 1970s, with the rise of neo-corporatism, scholarly interest turned to “self-organizing networks, partnerships and other forms of reflexive collaboration” instead of the hierarchical authority of the state (Jessop Reference Jessop, Ansell and Torfing2016, p. 71). “Non-market” cooperation between employer associations and trade unions, involving minimal state intervention, became a core object of inquiry. Government became an arena “within which economic interest groups or normative social movements contended or allied with one another to shape the making of public policy decisions” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985, p. 4; Streeck and Schmitter Reference Streeck and Schmitter1985).

In the 1980s, the state re-emerged as a focal point in political analysis as scholars called for “bring[ing] the state back in” political analyses (Skocpol Reference Skocpol, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985, see also Heclo Reference Heclo1974). However, interest in the state faded with the emergence of the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) research program in the early 2000s (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001), which drew attention to the market or non-market mechanisms through which actors’ behavior achieved institutional equilibria. Such equilibria came, famously, in two “varieties”: a “coordinated” equilibrium attained via “extensive relational or incomplete contracting, network monitoring based on the exchange of private information insider networks, and more reliance on collaborative […] relationships and a “liberal” equilibrium achieved via “hierarchies and competitive market arrangements” (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001, p. 8).

Despite the great influence of VoC on the field, many scholars criticized its neglect of the state. In light of socio-structural pressures, scholars highlighted the importance of state intervention in collectively-governed systems (Hancké et al. Reference Hancké, Rhodes and Thatcher2007; Regini Reference Regini2003; Watson Reference Watson2003). Not only did the state shape the broader business system, including how employers behave through associations (Whitley Reference Whitley, Morgan, Whitley and Moen2005), but it could also revitalize employer coordination, including by subsidizing private sector associations (Streeck Reference Streeck1997). For example, Martin and Thelen’s work (Reference Martin and Thelen2007) related differing coordination survival in Denmark and Germany to the state’s role and size.

Since the Great Recession, the role of the state has become ever more apparent (Bulfone Reference Bulfone2023; Moschella Reference Moschella2023) and several recent studies have drawn attention to state intervention in collective markets, such as VET (Busemeyer et al. Reference Busemeyer, Carstensen and Emmenegger2022; Ibsen and Thelen Reference Ibsen and Thelen2014), often promoted by actors to the Left of the political spectrum (Carstensen et al. Reference Carstensen, Emmenegger and Unterweger2022; Durazzi and Geyer Reference Durazzi and Geyer2020). Yet, we lack a systematic understanding of when and – crucially – how actors on the Left intervene. This paper aims to fill this gap by posing the following research question: How and why do left-wing governments intervene in collective markets to shore up coordination? We focus special attention on the factors configuring types of state intervention as viable courses of action and develop a typology of state intervention in the next section.

Theorizing the Left’s intervention in collective markets

In this section, we embed a typology of policy instruments in a broader CPE framework. We study policy instruments (Capano and Howlett Reference Capano and Howlett2020) through the widely applied typology developed by Evert Vedung (Reference Vedung, Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung1998). This typology provides a more fine-grained and nuanced account of the policy instruments for state intervention compared to the standard CPE approach, which tends to fall back on rather crude binary distinctions between “more” or “less” state intervention. At the same time, we embed concepts from the public policy literature within a broader CPE framework and point to the distribution of costs and benefits across different instruments. These deeply political conditions are a blind spot from the perspective of the public policy literature but are important in theorizing the conditions under which different policy choices can be pursued. In doing so, we embrace recent calls for the integration of public policy and CPE debates to advance theoretically both streams (Durazzi Reference Durazzi2022; John Reference John2018).

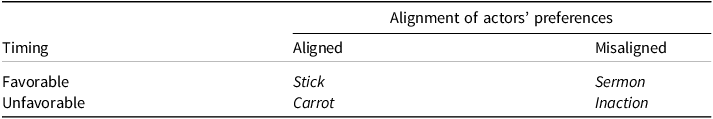

Policy instruments are classified as follows (see Figure 1 for a visual illustration). First, regulations are measures consisting of rules and directives aimed at mandating actions of rule-takers. They are often associated with the threat of negative sanctions for non-compliant actors (think of polluting beyond a certain threshold) or outright impositions on (particular groups of) actors (think of statutory changes to employers’ social security contributions). Vedung refers to these as sticks, which are the most coercive form of state intervention because rule-makers intervene in a way that (i) forces rule-takers to comply and (ii) shifts the costs of state intervention onto them. Second, subsidies involve the handing out or taking away of material resources. This instrument makes it cheaper or more expensive (in cash or other resources) to pursue certain courses of action over others (think of publicly providing R&D resources to firms who commit to engaging in certain economic activities). The costs of this measure are born by the state which sets the incentives, but rule-takers are not forced to undertake that course of action. Subsidies are also called carrots in Vedung’s terminology and are less coercive form of intervention compared to regulations. Third, information consists of moral suasion acts aimed at influencing people through the communication of arguments and knowledge. Information does not need to be factual and objective but can also concern more normative notions about “what is right or wrong.” As with subsidies, information does not involve any level of obligation. In contrast to subsidies, however, information does not involve the handing out of material resources as rewards for action and therefore it does not impose material costs or benefit on rule-takers, resulting in the weakest form of state intervention, named sermons by Vedung (Reference Vedung, Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung1998).

Figure 1. Typology of public policy instruments.

Source: Vedung, Reference Vedung, Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung1998.

The next step, largely eluded by the public policy literature but crucial from a CPE perspective, is to theorize the conditions under which actors on the Left opt for certain instruments over others, delivering more or less ambitious policy goals. We propose a parsimonious framework to account for this choice, which highlights two variables. The first has to do with the extent to which actors on the Left of the political spectrum, chiefly center-left parties and trade unions (hereby referred to collectively as “the Left”), agree on the need to intervene on a certain issue, that is the extent to which their preferences are aligned. We take cues from PRT (Korpi Reference Korpi2006) to suggest that a coalitional (re-)alignment between actors on the Left is crucial for incisive state intervention to counter likely opponents, notably business. We are sympathetic to Carstensen et al. (Reference Carstensen, Emmenegger and Unterweger2022)’s effort to study the conditions under which partisan politics matters for collective governance and build on the authors’ argument that partisan politics “sets the terms” of state intervention when the corporatist arena is conflictual. However, contrarily to their focus on the “outcomes” of state intervention in terms of social inclusion, we are interested in the type of intervention, ranging from more to less coercive. Given the increasing structural power of firms, absent broad and strong coalitional support, both from parties and unions, it is unlikely for actors on the Left to be able to push reforms that enlarge the scope of the state relative to collective governance (Vogel Reference Vogel1987).

Yet, actors form their preferences through learning processes that take place within complex organizations and unfold over time (Freeman Reference Freeman, Goodin, Moran and Rein2006). Political science has extensively engaged with the enabling conditions for policy at the organizational level, ranging from state capacity to organizational capacity. We submit that there is an exogenous enabling condition to policy innovation, which we term timing. Temporal concerns have been crucial to groundbreaking political analyses (for example, see Jacobs Reference Jacobs2012; Kreuzer Reference Kreuzer2023; Pierson Reference Pierson2004) that have situated temporal questions in a variety of empirical settings, ranging from the role of time in institutions, processes, organizations, actor constellations, ideas, policy problems and public policies (Goetz Reference Goetz and Goetz2023). Yet, temporality has rarely been integrated in research on policy instruments (Capano and Howlett Reference Capano and Howlett2020, p. 3). As such, we argue that it is not only important that actors’ preferences align, but that timing is favorable to their mobilization. We define timing as the socio-economic context that creates momentum for a policy innovation and functions as “windows of opportunity” (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995).Footnote 2 This conception of timing considers time as a long-term development that does not necessarily amount to an “explosive” crisis but creates the context for the emergence of policy problems and the need for the formulation of appropriate solutions in the form of choosing a policy instrument over others (Seabrooke and Tsingou Reference Seabrooke and Tsingou2019; Carstensen et al. Reference Carstensen, Emmenegger and Ivardi2025). As such, timing enables agentic action to receive the legitimacy necessary to address policy problems (Bakir Reference Bakir2022). The timing of decision-making within organizations, however, may not necessarily develop in line with the broader socio-economic context due to endogenous factors, e.g., changes in leadership or intra-organizational conflicts giving greater power to certain factions over others, or due to exogenous factors, e.g., how the economy or the labor market are faring. For example, actors may start “powering and puzzling” (Heclo Reference Heclo1974) over a policy instrument at t0 and develop a coherent policy preference at t1 only to realize that such an instrument was only suited for the socio-economic context at t 0, which may make it less appealing at t 1. At the same time, a policy instrument can become institutionalized and generate positive or negative feedback effects that affect its future operation (Capano and Howlett Reference Capano and Howlett2020, p. 4). In short, we submit that the socio-economic context in which policies are formulated provides opportunities and constraints that are to a certain extent independent of actors’ attempts to (de-) politicize it.

Thinking in terms of alignment between actors’ preferences and timing has obvious affinities with public policy classics, such as “garbage can models” and “multiple streams” (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995). However, these models tend to under-specify their dependent variable, which essentially boils down to a dichotomy between introducing a policy or not. Instead, using Vedung’s typology as the outcome variable and locating it at the intersection of actors’ alignment and timing, we develop more nuanced expectations not only as to whether state intervention occurs – but also in which form.

The most coercive form of state intervention – that of sticks – is more likely to emerge when both conditions are present, namely, actors on the Left agree on a specific policy intervention and when the timing is favorable to such intervention. Think of regulating atypical employment by making it unlawful for firms to employ workers on atypical contracts (beyond specific circumstances). We expect such intervention to be more likely if unions and center-left parties stand behind it and if atypical employment is on the rise, which provides a clear rationale for state actors to impose the cost of adjustment on firms.

Now consider the same situation, but in a context where atypical employment stands at an all-time low. If the Left has politically coalesced around this issue, we expect actors to be willing to intervene. Yet, due to the timing, it is unlikely that state actors will have the authority to sanction firms and, thus, exert the highest possible degree of coercion. Businesses could counter such an intervention by pointing at the inconsistency of attempting to use regulation to bring down a phenomenon that is already contained. With this “unfavorable” timing, state intervention may take the form of a carrot, e.g. a subsidy for firms who are willing to transform atypical into standard workers but could not turn into a stick. A carrot type of state intervention is a way for the “united Left” to show its willingness to act, while, at the same time, avoiding conflicts with business by internalizing the costs of the measure – a conflict that the Left may have a hard time winning, if “timing” is on the side of its opponents.

We expect yet another outcome if the timing is favorable, but the Left’s preferences are misaligned. Consider a context where atypical employment is at an all-time high, where unions are vocal about regulating it but the center-left party leadership is moderate and business-friendly. With misaligned preferences, any form of coercion becomes hard to expect. Therefore, in this context, we expect the Left to opt for the least intrusive form of state intervention, i.e., that of encouraging some non-binding commitment from firms in collaborating to bring down atypical employment. We would expect, in other words, the Left to act through a sermon. A crucial assumption that makes us predict a sermon (and not a carrot) in the context of misaligned preferences and favorable timing is that misalignment within the Left manifests with trade unions having more leftist preferences than center-left parties, and not the other way around (Diessner et al. Reference Diessner, Durazzi, Filetti, Hope, Kleider and Tonelli2025). A similar argument is made by Jensen (Reference Jensen2012) who argues that since left-parties are office-seeking, they have electoral incentives to prefer policies that do not only captivate the interests of their constituency, but potentially appeal to broader voter shares. In contrast, unions are not office-seeking and can afford to pursue only the preferences of their members, which are workers with specific interests in the labor market (Engler and Voigt Reference Engler and Voigt2023). Following this line of reasoning, because the authority to act through public policy lies with parties in government and not with unions, if their preferences are misaligned – but timing still pushes for action – we expect an intervention to emerge through its weakest coercive form as the key actor behind it will be a center-left party who occupies a moderate and business-friendly position.

Finally, if preferences on the Left are not aligned and if the context is also unfavorable, we expect to see state inaction, given that there cannot be any credible form of intervention if actors cannot agree on what intervention should be and the socio-economic context does not provide a clear rationale for intervention altogether.

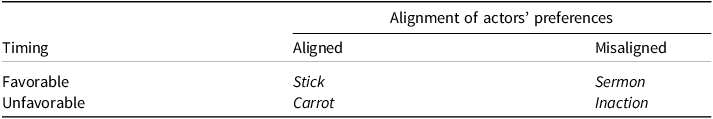

Leaving inaction to the side, given the chief interest of this article is on action and the forms that action takes, we can derive three theoretical propositions. Firstly, if the preferences of left-wing governments and unions are aligned (i.e., they agree on the desirability of a certain policy intervention) and the timing is favorable (i.e., a certain policy intervention matches the prevailing socio-economic context), the instrument chosen will be the most coercive. Government intervention will therefore take the form of a stick (theoretical proposition #1). Secondly, if left-wing governments and unions are aligned but the timing is not favorable (i.e., preferences converge on a certain policy intervention at a time when this does not match the prevailing socio-economic context), the chosen instrument will have less coercive power. It will therefore take the form of a carrot, whereby the government intervenes but “internalizes” the costs of intervention rather than imposing them onto rule-takers, as in the case of a stick (theoretical proposition #2). Thirdly, if left-wing governments and unions are misaligned but the timing is favorable, the chosen instrument has the lowest coercive nature. Governments will opt for a sermon – i.e. they will deploy moral suasion to shift actors’ behavior, but they will be unable to attach a credible sanctioning mechanism or commit significant financial resources for the attainment of their objective (theoretical proposition #3). Table 1 provides a succinct overview of the predicted forms of state (non-) intervention and the political-economic conditions that we have theorized to be associated with them.

Table 1. Predicted forms of state intervention

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Research design and data collection

To scrutinize empirically the three theoretical proposition developed in the previous section, we conduct process tracing to unpack causality (Trampusch and Palier Reference Trampusch and Palier2016, p. 438) between the introduction of the policy instrument and the variables that we have theorized (alignment and timing). Process tracing is an appropriate method because it allows us to “flesh out the causal process between X and Y” (Beach Reference Beach2016, p. 464; see also Trampusch and Palier Reference Trampusch and Palier2016). To this end, we have followed the three-step approach recommended by Beach (Reference Beach2016) for theory-first process-tracing research: “(1) making predictions about what the empirical fingerprints each part of a mechanism would leave in a given case, and evaluating the predicted evidence in theoretically certain and/or unique in relation to the theorized mechanism […], (2) collecting empirical evidence and assessing whether one actually found the predicted evidence, and (3) evaluating whether we can trust the found evidence” (pp. 468–9). We collected evidence from primary and secondary sources, i.e., newspaper articles, policy reports and statements by relevant stakeholders and academic literature (see Appendix for a full and exhaustive list). Each source has a unique bracketed acronym that we use throughout the analysis to distinguish it from citations to other academic literature. We test the theory elaborated above, according to which different mixes of alignment and timing lead to varying choices of policy instruments by looking for its observable implications in representative policy areas (Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2015).

We examine two least likely policy areas nested within a least likely case (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975). Germany is often considered the prototype of corporatism, and a country where the “semi-sovereign” state (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1987) is least involved in policymaking. Analysts have seen the role of the state representing a “shadow of hierarchy” (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1997) in which corporatist decision-making bodies that feature the social partners prominently discuss policymaking. Within the country, this paper focuses on two least likely policy areas from the perspective of theories about the involvement of the state, namely wage setting and VET. Wage setting in Germany takes place through collective bargaining, meaning that unions and employers negotiate working conditions independently from the state. VET is considered the “poster child” of coordinated capitalism (Culpepper Reference Culpepper, Hall and Soskice2001) because it involves employers and unions in governance. Employers have a pivotal role as they provide training (Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2012) and, together with unions, take part in decision-making around VET at various levels of governance (Emmenegger et al. Reference Emmenegger, Graf and Trampusch2019). The least likely nature of the policy areas that we analyze and of the country in which we analyze them means that we effectively stack the cards against our argument. Hence, if our proposed framework holds under the least favorable theoretical circumstances, it is likely that its validity will travel beyond this case.

Analysis

This section examines how state intervention evolved over the last (circa) two decades in two policy realms traditionally governed via collective-markets, wage setting and VET.

From sermon to stick in wage setting: the introduction of a statutory minimum wage

In this section, we show that the early 2000s the collective market of wage setting had started showing significant cracks. The socio-economic context began therefore to be favorable for forms of state intervention to be considered. The Left, however, was misaligned on the policy instruments to be pursued, with a statutory minimum wage (SMW) emerging as a rather divisive option. The result was a series of sermons (proposition #3). Over time, however the Left re-aligned and actors’ preferences coalesced in support of a SMW. The socio-economic context proved “favorable”, leading to the introduction of a stick in wage setting, namely a SMW (proposition #1).

Misalignment of the Left and favorable timing: a sermon

The introduction of a SMW in Germany appeared unlikely for a long time as actors from across the political spectrum, including the Left, traditionally preferred bargaining between employers and unions at the sectoral level over state intervention in setting wages [S39]. And, indeed, collective bargaining coverage had been high in post-World War II Germany, standing at 85% just before German reunification [S35]. Yet, structural trends (e.g., globalization, de-industrialization, increasing female labor market participation) and political choices (e.g., the Hartz reforms) jointly contributed to decreasing coverage of collective bargaining and increasing use of non-standard work in the German labor market [S35]. As these trends unfolded through the 1990s, a debate around the need for the introduction of a SMW emerged. This debate initially took place at the fringes of the labor movement, with the Food and Allied Workers Union (NGG) proposing the introduction of a (national) SMW in 1999 testifying to the difficulties faced by unions in low-end services to command decent wages [S35, p. 26; S39, p. 66]. The proposal was not met with enthusiasm. Although with varying degrees of skepticism, most of the trade union movement, employers’ associations, and mainstream political parties voiced their continued trust in the collective bargaining system over state intervention in wage setting matters at the turn of the century.

Until around 2007, trade unions remained substantially divided on the introduction of the SMW. The NGG and ver.di, the union representing service sector workers, together with a small part of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) endorsed the need for a SMW [S39]. However, other unions, i.e., IG-BAU, the construction union, and Industrial Union of Metalworkers (IGM), opposed it because through sectoral wage bargaining, they could retain the power to negotiate wages, which would be conceded to governments with a SMW [S37]. Meanwhile, the timing for intervening in the labor market would have been favorable. With the effect of the Hartz reforms beginning to show, a low-wage segment of the labor market proliferated, and in-work poverty started increasing, particularly in the service sector [S38]. Despite favorable timing, as long as the Left remained divided, it was difficult to agree on a common course of action. The only action that was concerted at this point was an exhortation, included in the coalition agreement of 2005 between the center-right Christian Democratic Party (CDU) and the center-left SPD to prevent wages from falling “below an unethical level” [S39, p. 69]. The divided Left could not expect to coerce employers in any way and, following proposition #3, it proposed a sermon type of intervention, a non-binding commitment to uphold the conditions in the labor market [P25].

Re-alignment of the Left and good timing: introduction of a stick

The introduction of a SMW in Germany is the outcome of a coalitional re-alignment between the SPD and the trade union movement after their relationship had become adversarial during the liberalizing Hartz reforms in the early 2000s [S36]. Marx and Starke identify indeed trade unions as first movers in the implementation of the SMW [S38].

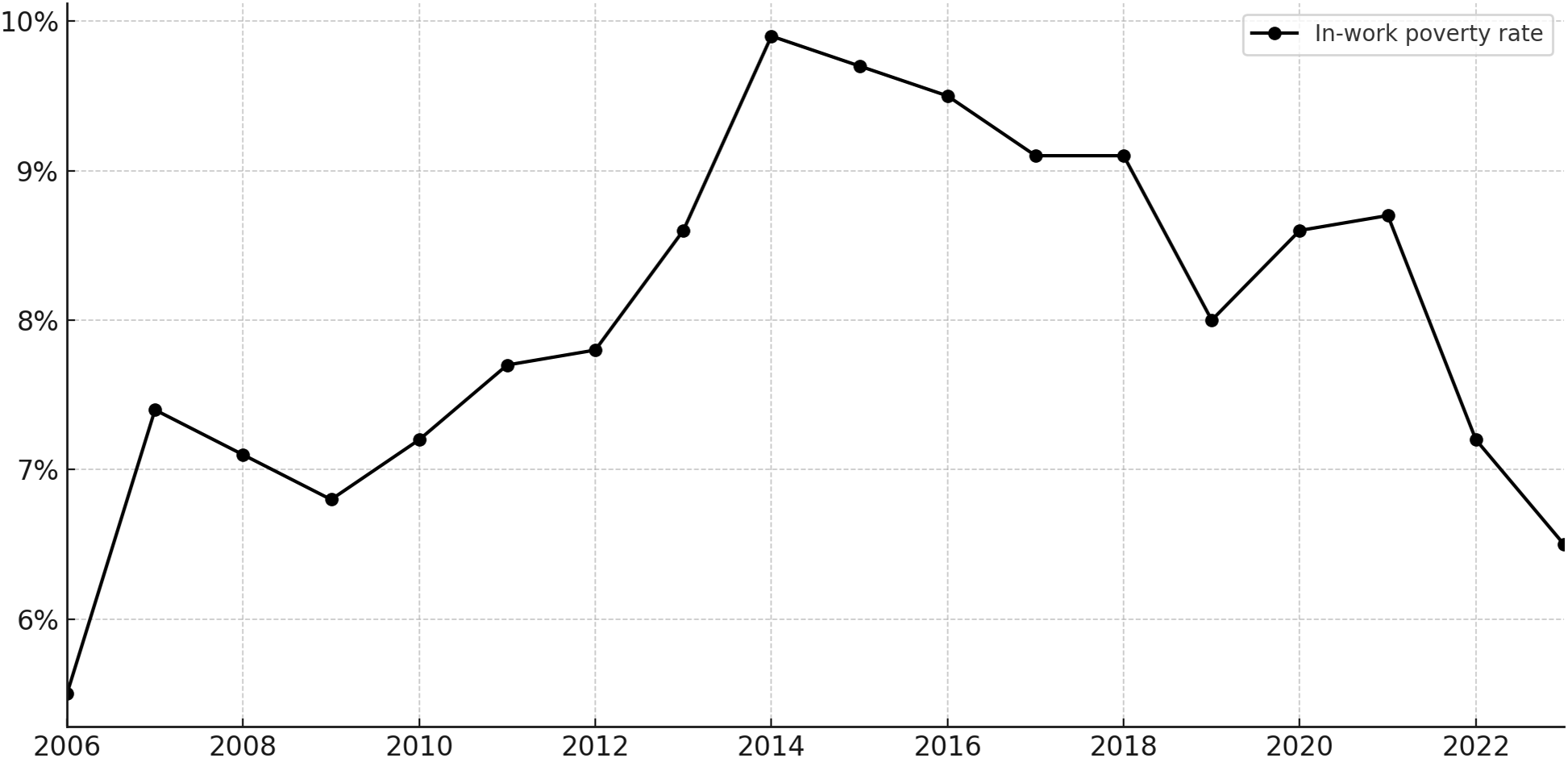

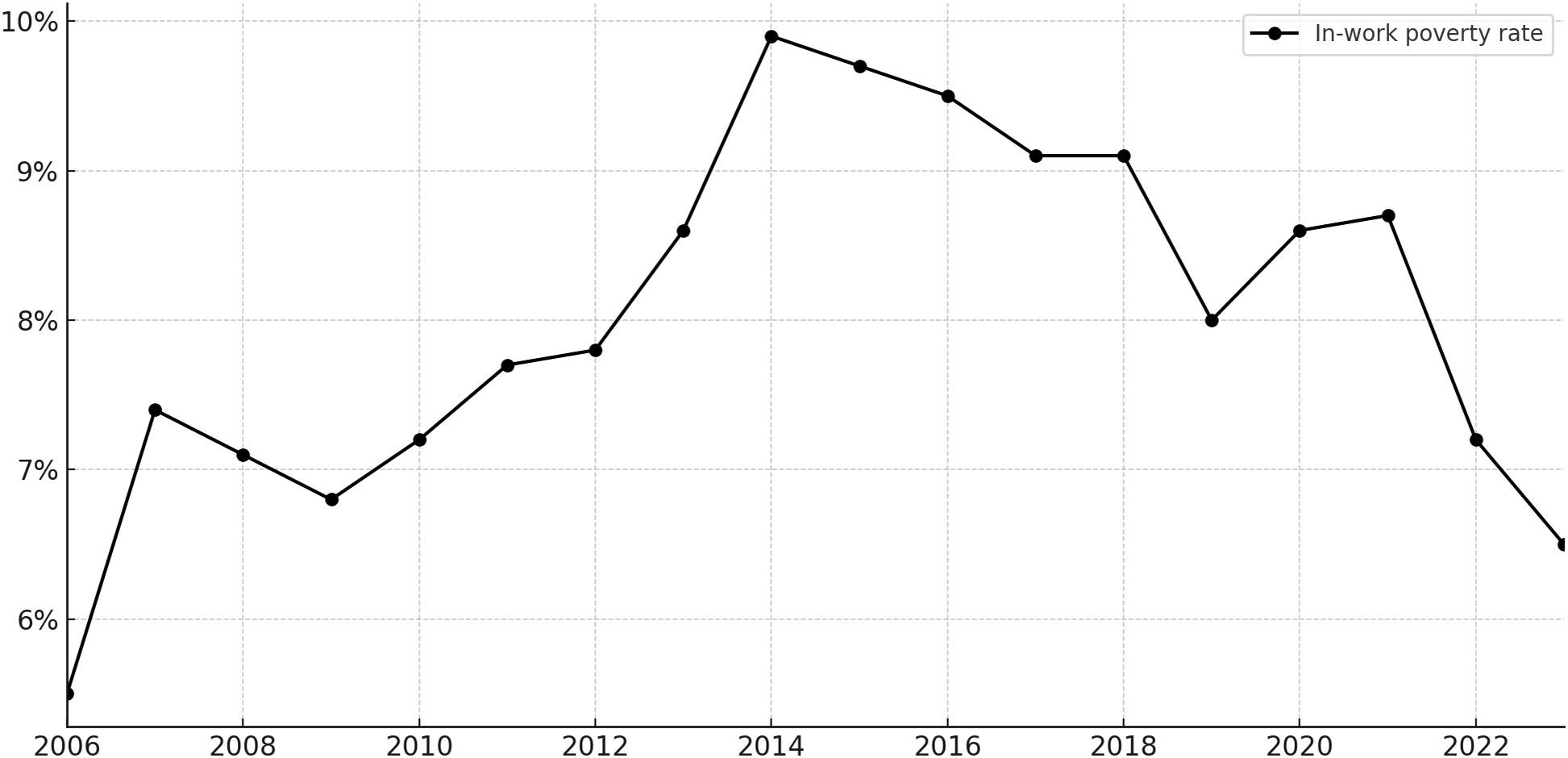

As indicated above, timing remained ideal for an intervention in wage setting, as conditions in the labor market had all but been worsening due to dualization and deindustrialization. A crucial indicator to assess how the socio-economic context proved favorable to the introduction of a SMW is the rate of in-work at-risk-of-poverty rates among adults. As Figure 2 shows, this had been on the rise since 2005, providing clear evidence that – if workers experienced poverty despite being employed – wage setting was no longer appropriately functioning. Indeed, it is 2007, when in-work poverty reached new heights that a “change of heart” took place within the union movement and a process of re-alignment in the preferences of the Left began [S37].

Figure 2. The socio-economic context of state intervention in the labor market: In-work poverty rate (2005–2023).

Source: EU-SILC survey [ILC_IW01__custom_10752536].

A watershed moment was when the German Confederation of Trade Unions (DGB) took over responsibility for promoting the SMW in a national campaign. No longer a marginal issue owned by service sector unions, the introduction of a SMW became a key demand of the DGB in 2006, when it was included in the DGB’s Federal Congress resolution. This was followed by a high-profile campaign in favor of a minimum wage taken over by DGB in 2007 after it had been initiated by service sector unions ver.di and NGG [P28]. An additional key moment was when the IGM, the largest union federation and traditionally among the SMW-skeptics, decided to throw its weight behind the campaign. Notably, IGM’s choice did not happen exclusively due to self-interest, as the level of SMW was likely going to be lower than collectively bargained wages in the metal-working sector. IGM acted out of solidarity with the broader union movement and recognized how unions in other quarters of the economy – notably the service sector – were unable to command decent wages for their members [S38]. Broadly speaking, the mix of interests and ideas that informed IGM’s choice to back the introduction of a SMW are representatives of the motives behind the union movement more generally: interests mattered because wage competition from the periphery of the labor market had started to threaten the core; but ideas mattered too, as unions justified their change of preferences in class-solidaristic terms, stretching across sectors [S38]. Backed by an overwhelming majority of IGM members – around 80% – voting in favor of curtailing the low-wage sector and curbing in-work poverty, IGM leaders talked of the SMW as “the just punishment [for employers] dumping wages” [N5].

Employers staunchly opposed the introduction of a SMW, highlighting the need for companies to hire flexibly, and attempting to shift the debate on the potential job losses that the introduction of a SMW would cause. Once it became clear that there was a political majority backing the introduction of a SMW, employers’ efforts shifted onto making its application “flexible,” e.g. by pushing for exceptions – some of which were eventually accepted. Yet, for a SMW to be introduced, it is not enough for the unions to have the upper hand on employers. There needs to be a parliamentary majority that is willing to vote for it. The role of political parties and policymakers has been therefore highlighted alongside that of the unions [S37]. Once the DGB managed to create broad support among unions – crucially including traditional skeptics such IGM – also the SPD became gradually more invested [S38].

Here, we come across a somewhat different set of arguments being put forward in favor of the SMW. Parties at the center-left of the political spectrum made the introduction of a SMW a key demand during the 2013 electoral campaign and the SPD made it a “red line” for them to join the grand coalition after the election. The motives put forward by center-left parties, however, appear rather different from the class-solidaristic arguments coming from the union camp. Rather, SPD and Green’s representatives stressed the importance of a SMW on grounds of fiscal prudence because – their argument goes – low wages call for tax-financed supplements in the form of in-work benefits, hence shifting costs away from employers onto taxpayers. This argument has been recurrent. A representative of the Greens talked about SMW as a way to protect “the public coffers from the fact that in many sectors the form for top-ups financed by the state is added to the employment contract” [N3]. In a similar vein, the SPD representatives argued that the SMW

alone saves the state seven billion euros, among other things because we then don’t have to top up wages with tax money. It has absolutely nothing to do with the market economy that we permanently use the state treasury to provide wage subsidies [N7].

An SPD economic expert pushed this argument further by saying that the introduction of a SMW should not be a matter of partisan politics but one of “correcting an undesirable development in the German economy” since “[i]t cannot and must not be that we are subsidizing wage dumping with tax money” [N8]. This argument came up again in 2014 when discussing the design of the SMW and it was brought up by the highest levels of the SPD, namely Minister of Labor Nahles, who argued that the SMW

makes an important contribution to fair and functioning competition in our country. It ensures more stability in social security funds. To secure one’s existence, wages no longer have to be topped up by state basic security benefits for job seekers. This means that taxpayers no longer have to subsidize dumping wages. And we protect our honest employers, the majority of companies that already pay fair wages [N6].

This framing of the SMW as a policy of fairness toward the tax-payer and of rectitude in the management of public finance put center-right parties on the defensive. The CDU/Christian Social Union (CSU), for instance, fairly quickly moved from the position of thinking of the SMW as a “job killer” [N2] to a much more “appeasing” position, calling for the application of a minimum wage “selectively” and focused “in sectors where unions cannot assert themselves” [N1]. Perhaps most indicative of how the arguments put forward by the SPD opened a breach across party lines is how the most vocal opponent of the SMW – i.e. the Liberal Party (FDP) – bought into the idea that “[w]here there is no collective bargaining agreement, it cannot be the case that the taxpayer subsidizes business models in which employees earn wages that they cannot live on in the long term” [N4], although the FDP remained of the position that social partners should address this issue via collective bargaining. Comparing the framing of the unions and the SPD allows us to weight contrasting evidence on the introduction of the SMW in Germany, analyzing explanations that foreground the role of unions [S38] versus state agency [S37]. The unions – with their vigorous class-solidaristic framing of the SMW – have been crucial in putting the issue at the center of the political agenda and, therefore, getting the buy-in from the SPD. The fairness toward the taxpayer and public finance rectitude argument embraced by the SPD, however, resonated with politicians from across the political spectrum, creating therefore a broad political coalition that commanded a parliamentary majority in favor of the introduction of a SMW. If the unions were crucial at the agenda-setting stage, it was the SPD’s discourse that conferred the SMW sufficient political legitimacy for a parliamentary majority to get behind it.

In the coalition government negotiations in the aftermath of the 2013 federal election, the introduction of a national SMW became the red line for the SPD to join the CDU/CSU in government. Such a strong stance was enabled by the support for a SMW shared by all major actors on the Left as well as by a socio-economic context that kept providing favorable functional underpinnings to this policy instruments, given still rising in-work poverty rates at the time of the coalition negotiation (recall Figure 2). Therefore, following proposition #1, a stick was introduced. The grand coalition government was sworn in at the end of 2013, and a law on the introduction of a national SMW was passed in 2014, coming into effect at the beginning of 2015. The SMW came into effect on 1st January 2015. It set a nationwide hourly minimum wage at EUR 8.50, with an in-built provision for the rate to go up in 2017. From 2017 onwards, the SMW level would be decided upon by a commission composed of nine members, three appointed by the unions, three appointed by the employers, a commission chairperson, and two independent experts. The latter does not have voting rights. The chairperson does not vote in the first instance, but s/he is responsible for formulating a proposal of mediation in case the six representatives of the producer groups cannot reach a majority. If a majority is not reached after the mediation, then the chairperson acquires the right to vote [P31]. Since its introduction, the SMW has been raised eight times and it currently stands at EUR 12.82/hour [P27].

From (attempted) stick to carrot in VET: the introduction of a training guarantee

In this section we show that the collectively-governed market of VET encountered severe difficulties form the early 2000s, when insufficient supply of training places on the side of business gave rise to the so-called apprenticeship crisis [S41, S43, S46]. This socio-economic context, therefore, allowed a discussion on state intervention to take off. But while some actors on the Left advocated the introduction of a training levy (i.e., a stick), this policy instrument was seen as controversial and opposed by others within the Left. The training levy, therefore, ultimately failed due to a misalignment of actors on the Left, despite a favorable socio-economic context. Again following proposition #3, the fallback option was a sermon – i.e., a non-binding exhortation by the government to employers, asking them to step up the supply of training place. Over time, actors on the Left converged on the need of state intervention, but by the time such alignment of preferences occurred, the crisis of the apprenticeship market was much less severe. As a result, and following proposition #2, in the 2020s, the carrot training guarantee was introduced as the outcome of aligned actors’ preferences in an unfavorable socio-economic context.

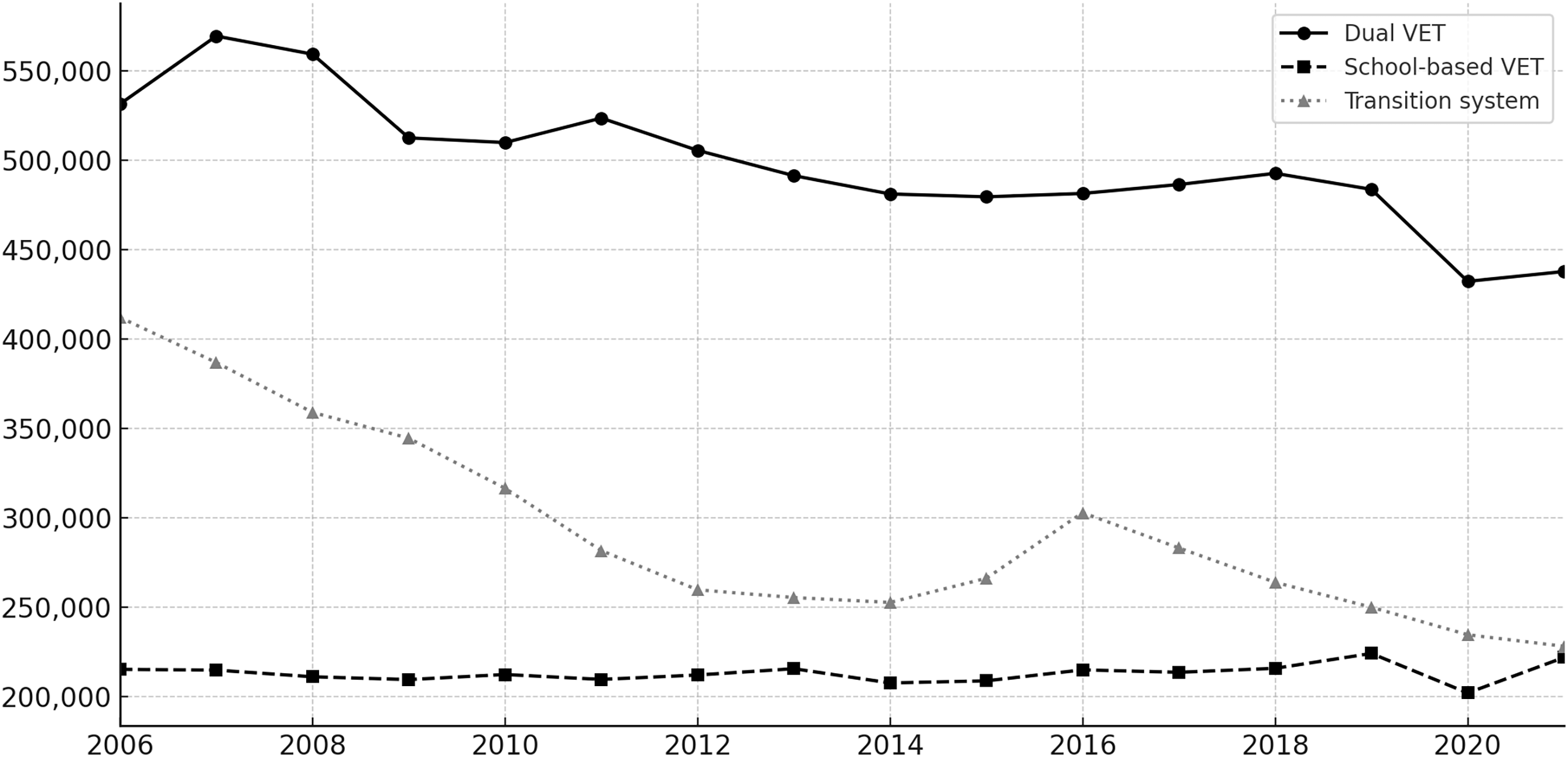

Good timing but misalignment of the Left: the failed stick training levy

The need for policy intervention in training originated in the crisis of the training market in the early 2000s, when applicants struggled to secure a training place. A big problem emerging in the debate around this time related to the so-called transition system (Übergangssystem), an arrangement of different labor market instruments that was introduced after a proposal to upgrade school-based training had failed (Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2012). The transition system is not subject to standardized certification and provides preparation without qualifications [S40]. Therefore, it carries little labor market value and provides lower quality training to people at the lower end of the skills distribution, who become even less likely to receive high-level certified training [S45]. Figure 3 shows that in the early 2000s, the transition system was at record high levels of participation (more than 400.000 entrants in 2006, the earliest year available for data collection). Thus, policy discussions centered around the problem of the transition system becoming a “parking lot” for young people who lacked prospects [I32, see also S48, N20].

Figure 3. The socio-economic context of state intervention in VET policy: New entrants across different VET paths (2006–2021).

Source: National Education Report (2022).

In the 2000s, policy circles in Germany discussed the (re-)introduction of a training levy, indicating a formal requirement for firms to pay into a joint training fund, to reimburse training firms. A national training levy had been adopted in the 1970s, but the government had never used it, and the law had been declared void by the Constitutional Court in 1981. Arrangements similar to training levies are customary in European countries, e.g., the apprenticeship tax in France or the employers’ training contribution in Denmark. In our framework, since a training levy represents a strong incentive to train, it can be understood as a stick type of policy intervention, as it requires that even non-training firms pay into the joint fund, according to the collective logic whereby firms that train are helping the whole employer community by creating a skilled workforce [S42]. As timing was pressing to intervene in the training market due to the apprenticeship crisis, the SPD proposed introducing the collection of a training levy to pressure employers into providing more training spots (Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2012, p. 701). The proposal for a national training levy came from the social-democratic party and the unions. The proposal originated with the DGB, who saw it as a way to improve the chances of young people in the training market [N9]. However, the Left was misaligned, because although they had long demanded a training levy, unions did not support it unanimously. Only the more left-leaning unions endorsed the proposal, and the more centrist (the trade union for mining, chemicals and energy, IG BCE and the trade union for construction, IG BAU) were against it. Even the SPD was internally split over the technical feasibility of the levy (Durazzi and Geyer Reference Durazzi2022). When the misaligned Left encountered the opposition of the right, the proposal fell. The view that ultimately prevailed was the one of the CDU and FDP, who saw the levy as an intrusion of the state into firms’ autonomy over training.

Due to the rising pressure to act and solve the apprenticeship crisis, in 2004 the government resolved to enact the first National Pact for Vocational Training and the Qualification of Skilled Workers in Germany. The Pact, signed by the Federal Ministries in charge of economics, labor, and education and several employers’ organizations established a new governance structure for the training market [S42]. This intervention can be characterized as a sermon due to its non-binding character (see proposition #3). Notably, the Left remained skeptical of this solution. Unions did not sign the pact as they never believed it would be an effective way to create new training spots. The Pact was renewed in 2007 and 2010 despite continued criticism.

The training guarantee: the introduction of a “carrot”

In the 2015–2020 period (before the COVID-19 pandemic), policy discussions centered again around the need to intervene to ensure graduates could access adequate training. Generally, the feeling in policy circles was that despite various measures put in place over the years to compensate for imbalances in the training market, among which promoting the mobility of young people and improving career guidance, matching problems persisted [S48]. In particular, the transition system became connected to broader considerations about the increasing numbers of unskilled youth at risk of poverty (one in four young people in 2023) [see N17]. As such, discussions around the need to reform the transition system sparked.

The Left was aligned on the need to intervene structurally in the training market to prevent students from falling into the dead-end of the transition system, namely the “educational scandal” of 2.6 million people between the ages of 20 and 30 without vocational qualifications in 2023 [N10]. Pressure came from the trade youth group and the young socialists of the SPD (Jusos) to develop a training guarantee [I32, I34, N22]. Minister Hubertus Heil (SPD) was a key proponent of the training guarantee, intending to “correct earlier liberalizations of the labor market with regard to dual VET” [S47, p.143]. The training guarantee is modeled after the Austrian policy that creates a commitment to supply all compulsory school graduates who do not have a place at an upper-secondary school or cannot find a company-based apprenticeship with the opportunity to learn an apprenticeship trade at a supra-company training institution that is publicly financed [S44]. Since the primary responsibility of the private sector to train remains untouched [N10, N11, N16], the training guarantee can be understood as a carrot type of policy intervention, a facilitative measure that addressees are not obliged to adopt, contrary to a stick type of regulation.

Financing the training guarantee was a hard sell for the Left. Both trade unions and left-wing parties thought the guarantee should be financed through a levy, especially in those sectors where firms train below market demand [I32, I34]. The DGB writes “the DGB and its member unions are … proposing that the financing [of the training guarantee] should be based on a nationwide future fund into which all companies pay” [P30, p. 4] because although the costs of training are born by a part of the companies, the availability of skilled workers benefits all companies. The fund would achieve the objective of promoting in-company training and cover the costs of additional external training, such as the one provided under the training guarantee. As such, the advocates of the training guarantee proposed a training levy to finance it, essentially with the same arguments that had been used in the training levy debate decades earlier. With this additional instrument, what seemed like a carrot type of intervention, became a stick, due to the hypothetical regulatory obligation for firms to pay into the joint fund.

However, despite the alignment of the actors on the Left, the timing was not favorable. Although the pandemic brought momentum to the worsening conditions of the training system [N18], by the time the Left had to negotiate with other political actors in the context of the coalition agreement, the pressing problem of the transition system had waned [I33]. As shown in Figure 3, at the time when the training guarantee was presented in the coalition agreement, participation in the transition system was at its lowest since its inception, and the system catered to slightly more than 200,000 new entrants every year. New entrants were the same number as those in the school-based VET, which always enjoyed comparatively lower popularity in Germany compared to the apprenticeship-based type of VET. This meant that, when the discussion for the levy-financed training guarantee came to the fore, the urgency of it appeared to be at an all-time low prompting an instrument with less coercive power than the Left would have hoped for (proposition #2). Employers, the CDU, and the FDP always disagreed on the need for an obligation for firms to pay into a joint fund, and their criticism prevailed due to bad timing [N12]. There nevertheless is evidence that actors across the political spectrum recognized the urgent need to intervene in the training market [P30]. However, we find that the levy financing, which is what characterizes the policy as a stick and not a carrot, would have required favorable timing to be implemented.

The coalition agreement, which was the result of negotiation between the Greens, the SPD, and the FDP, did not manage to include levy financing, which the FDP fiercely opposed [I32, see N12 and N23]. As such, the compromise was a training guarantee without any specification of its financing. There is contrasting evidence on the recommendations for the financing: while the Bertelsmann Stiftung argued that the only solution was to apply the guarantee at the federal level, the final version of the law followed the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung’s advice, who recommended a state-level approach. Only young people who “had made sufficient efforts to apply for roles and to have taken advantage of the careers advice services… or… live in a region in which the federal employment agencies have identified a significant shortage of vocational training places to exist” could apply for the guarantee [P29 para. 7]. This shows that the training guarantee was substantially watered down compared to its initial proposal, as a function of the constraints imposed by political negotiation within the government coalition, an element of timing that could not be predicted by the Left when it first started proposing the training guarantee. While the constellation of actors supporting state intervention here was similar to the one leading to the introduction of a stick in the SMW case (S37), our timing sensitive account helps us understanding why the outcome was different in the training case, taking the form of a “less coercive” instrument, namely carrot.

In 2022, a training guarantee was introduced in the German training market. The draft bill was presented at the end of 2022 by the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs after the government had presented the intention to introduce a training guarantee already in the coalition agreement signed in 2021. The bill comprises the commitment of the state to offer extra-company vocational training for those who cannot land an apprenticeship spot in a company [P24]. This policy only applies to young adults who did not get a training place in a company, even without a school-leaving certificate. Such extra-company training would take place in educational institutions commissioned by the Federal Employment Agency. This policy is foreseen as an “ultima ratio” that can be enacted when all the other measures of the bill have failed, including proposals to “strengthen vocational orientation,” “support young people to find an apprenticeship in another region” and “provide preparatory courses for in-company training” [P26].

Discussion and conclusion

We proposed a parsimonious typology of state interventions in collective markets based on the hierarchy of policy instruments developed by Vedung (Reference Vedung, Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung1998) to show that different policy instruments become actionable depending on the interaction of two key variables, alignment and timing.

The first variable is the coalitional (re-)alignment of actors on the Left, including social democratic parties and trade unions. This coalition is important to counter the likely opposition to state intervention of powerful actors such as businesses. The latter enjoy structural power and, thus, are likely to have the upper hand when the Left is divided. This can be seen at the beginning of the wage-setting timeline, when only few unions and a small part of the SPD were in favor of the SMW and, therefore, could not push for it. Therefore, the coalition government promoted a sermon type of intervention. As a caveat, we do not consider other actors who could express “left” positions, such as the Greens and parties belonging to the “new Left,” as this paper is rooted in traditional party studies. However, it is conceivable that these parties will become more important actors in these processes.

The second key variable is timing. Timing relates to the socio-economic context, which can be more or less favorable for creating momentum for a policy choice, acting as “windows of opportunity” (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995). While actors can choose to strategically draw attention to issues (Afonso Reference Afonso2012; Massoc Reference Massoc2019), we argue that actors have control over timing only to a limited extent, as political changes in leadership or organizational conflicts are hard to predict. A case in point are elections: for example, the need to negotiate the terms of the training guarantee with a tripartite coalition including the FDP was not anticipated by the SPD but it led to a watering down of the levy-funding aspect of the guarantee. Structural developments are also, to some extent, exogenous to politics. For example, the problem of in-work poverty was so high that discussions of a SMW were considered necessary, making timing favorable.

This paper builds a bridge between public policy studies that consider the role of time in political processes (Goetz Reference Goetz and Goetz2023; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995) and institutionalist accounts in CPE. On the one hand, this analysis offers a deeper insight into the “dependent variable” of most public policy studies, which is usually just a binary category for the introduction of a policy or the lack thereof. Here, the dependent variable is not simply whether the policy is introduced, but the degree of coercion that can be exerted on employers. On the other hand, this paper belongs to a stream of work that seeks to inject more agency into institutionalist accounts (Emmenegger Reference Emmenegger2021). By showing the extent to which Left actors can decide (and not always for material reasons, but also ideational ones, as in the case of IG Metall for the SMW) to (re)align, this paper sheds light on the micro-processes through which political actors can exercise agency and, ultimately, influence the politics of economic intervention. In this sense, this paper provides a more “political” perspective to the CPE literature about the resilience of coordination.

This study has limitations. While we have shown the importance of partisanship in accounting for state intervention to shore up collective governance, we do not have the ambition to evaluate the success of the policies under consideration. It goes beyond the scope of this paper to adjudicate on whether these policies, either the SMW or the training guarantee, achieved what they promised to workers and apprentices. What interests us here is the mechanisms of governance, namely the state’s intervention in markets where we would least expect it. Moreover, our structuralist explanation does not wish to close the door completely on more ideational factors that were also at play in the developments under consideration, as hinted in the section about the unions’ position towards the SMW. Ideational elements are crucial in VET too: for example, the German VET system is seen by the German policy community as stable and instrumental to economic efficiency (Ivardi Reference Ivardi2025). Thus, a key factor in the promotion of the training guarantee forward was that it was always presented as a complement to the apprenticeship system rather than a substitute for it, because any policy that calls the apprenticeship system more into question, is likely to meet with resistance.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100962

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions that greatly benefitted our paper. We sincerely thank Daniel Clegg, Patrick Emmenegger, Christian Lyhne Ibsen, Cathie Jo Martin, Paul Marx, Manuela Moschella, and participants at the 2025 SISEC Annual Conference for feedback on previous versions of the paper as well as our interview partners for sharing their knowledge with us. All remaining errors are our own.

Funding statement

Cecilia Ivardi acknowledges support by the Schweizerisches Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation in the framework of the Leading House “GOVPET: Governance of Vocational and Professional Education and Training.”

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none