A number of different changes took place to reduce original geminate consonants in Latin. In addition, there was another rule (or rules) which produced geminates out of original single consonants. Since these changes did not take place at the same time, and were not necessarily reflected in spelling at the same rate, I will discuss them here separately.

<ss> and <s>

Double /ss/ was degeminated after a long vowel or diphthong around the start of the first century BC (Reference MeiserMeiser 1998: 125; Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 66, 170), for example caussa > causa. A search for caussa finds 23 inscriptions from the first four centuries AD, compared to 269 for causa (a frequency of 8%), although the spelling with <ss> is rather higher in the first century AD (18 or 19 inscriptions containing caussa to 60 inscriptions containing causa = 23 or 24%),Footnote 1 including in official inscriptions such as the Res Gestae Diui Augusti (Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp. 769–99, AD 14),Footnote 2 the SC de Cn. Pisone patri (9 instances of causa to 3 of caussa in the B copy; Eck et al. 1968, AD 20), and CIL 14.85 (AD 46, EDR094023). By comparison, a search for (-)missit finds 4 instances in the first four centuries AD compared to 192 of (-)misit (a frequency of 2%).Footnote 3

Most of the writers on language clearly considered the <ss> spelling old-fashioned:

‘causam’ per unam s nec quemquam moueat antiqua scriptura: nam et ‘accussare’ per duo ss scripserunt, sicut ‘fuisse’, ‘diuisisse’, ‘esse’ et ‘causasse’ per duo ss scriptum inuenio; in qua enuntiatione quomodo duarum consonantium sonus exaudiatur, non inuenio.

Archaic writing should not prevent anyone from writing causa with a single s: for they also wrote accussare [for accūsāre], just as I find fuisse, diuisisse, esse, causasse written with double ss [as one would expect]. When these words are pronounced I do not know what the double consonant is supposed to sound like.

quid, quod Ciceronis temporibus paulumque infra, fere quotiens s littera media uocalium longarum uel subiecta longis esset, geminabatur, ut “caussae” “cassus” “diuissiones”? quo modo et ipsum et Vergilium quoque scripsisse manus eorum docent.

What of the fact that in Cicero’s time and a little later, often whenever the letter s was between long vowels or after a long vowel, it was written double, as in caussae, cassus, diuissione. That both he and Virgil wrote this way is shown by writings in their own hand.

iidem uoces quae pressiore sono edu[cu]ntur, ‘ausus, causa, fusus, odiosus’, per duo s scribebant, ‘aussus’.

The same people [i.e. the antiqui] wrote words which are now produced with a briefer sound, such as ausus, causa, fusus, odiosus, with double s, like this: aussus.

Although Terentius Scaurus states that there are ‘many’ who use the double <ss> spelling in causa:

‘causam’ item <a> multis scio per duo ‘s’ scribi ut non attendentibus hanc litteram … nisi praecedente uocali correpta non solere geminari.

I know that causa is spelt by many with two s-es, as by those not paying attention to the fact that this letter is not geminated unless the preceding vowel is short.

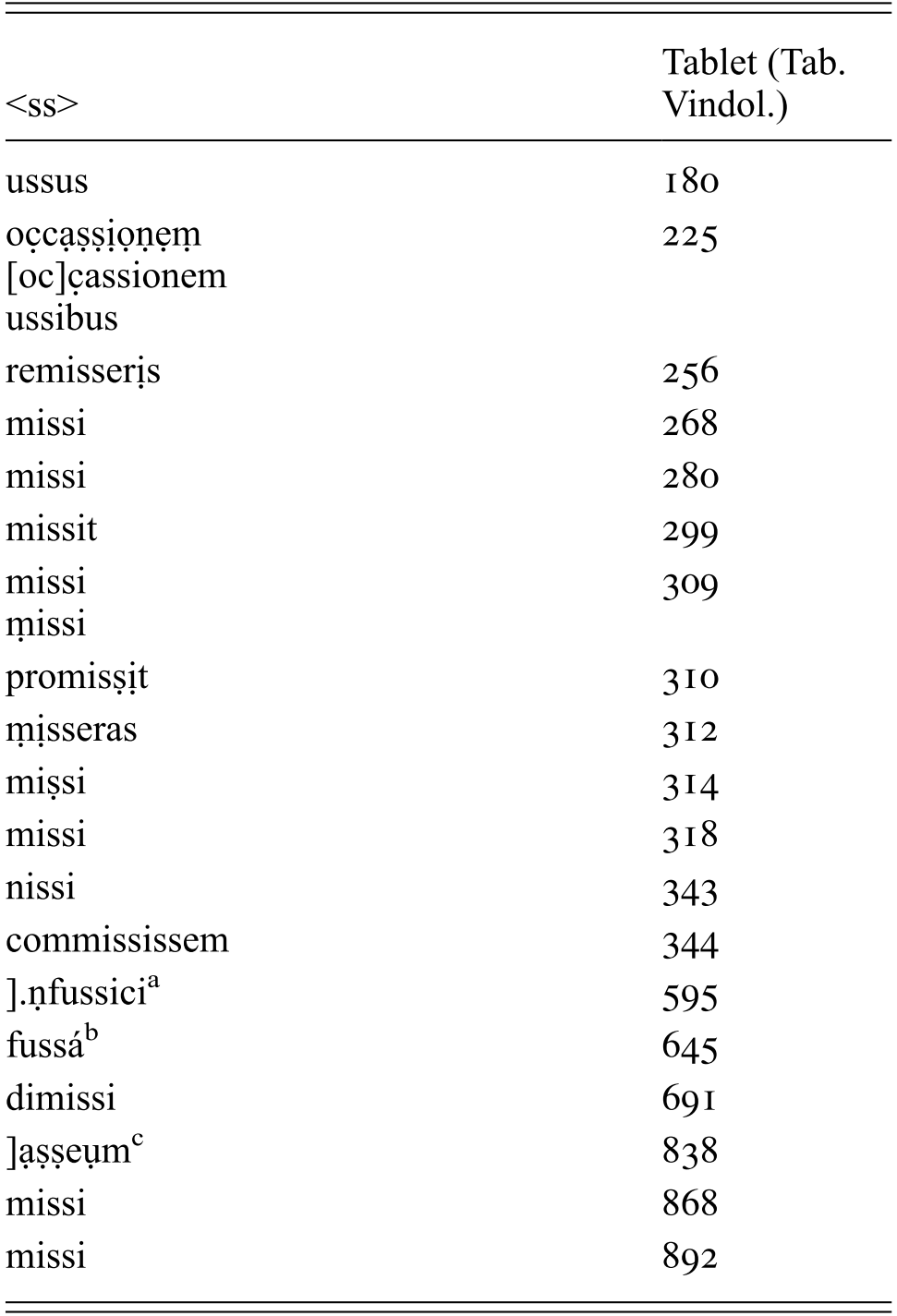

At Vindolanda the 21 instances of etymologically correct <ss> compare with 24 of <s>, giving a total of 47% (see Table 25).Footnote 4 The frequency with which the <ss> spelling is found in mīs-, the perfect stem of mittō ‘I send’, is out of kilter with the uncommon spelling of this lexeme with <ss> in the epigraphic evidence as a whole.

Table 25 <ss> at Vindolanda

| <ss> | Tablet (Tab. Vindol.) |

|---|---|

| ussus | 180 |

| 225 |

| remisserịs | 256 |

| missi | 268 |

| missi | 280 |

| missit | 299 |

| 309 |

| promisṣịt | 310 |

| ṃịsseras | 312 |

| miṣsi | 314 |

| missi | 318 |

| nissi | 343 |

| commississem | 344 |

| ].ṇfussiciFootnote a | 595 |

| fussáFootnote b | 645 |

| dimissi | 691 |

| ]ạṣṣeụmFootnote c | 838 |

| missi | 868 |

| missi | 892 |

a The editors suggest that this is to be taken as c]ọnf̣ussici ‘mixed’.

b See Reference AdamsAdams (2003: 556–7).

c Assuming that the editors are right to understand this as c]asseum ‘cheese’.

In 225, <ss> is used in the draft of a letter probably written in the hand of Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians himself, a man apparently of some education (on which, see Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 129, and p. 1), who also uses <uo> for /wu/. It is also found in 255, from Clodius Super to Cerialis; the editors suggest that though a centurion, Clodius may have been an equestrian (but there is no evidence he wrote it himself). In 256, a letter to Cerialis from a certain Genialis, <uo> is also used for /wu/ in siluolas; there are no substandard spellings. In the case of 312, a letter from Tullio to a duplicarius whose gentilicium is Cessaucius, the editors note that ‘[t]he hand is rather crude and sprawling’, which may suggest a lower level of education in the writer, although no substandard spellings are found.Footnote 5

Metto (the author of 309) and the anonymous author of 180 and 344 were probably civilians, and therefore not necessarily using military scribes. The writer of 309 also uses <xs> for <x>, as does the writer of 180 and 344 (who also writes 181: ụexṣịllari), who also includes substandard spellings in 180 (bubulcaris for bubulcāriīs ‘ox-herds’, turṭas for tortās ‘twisted loaves’ and 181 (emtis for emptīs, balniatore for balneātōre, and Ingenus for Ingenuus). Substandard spellings are also found in 892, a letter from the decurion Masclus to Julius Verecundus, prefect of the First Cohort of Tungrians, which has commiatum for commeātum and Reti and Retorum for Raetī, -ōrum. Since the final greeting is in a different hand, presumably that of Masclus himself, the writer of the rest of the text was probably a scribe.

Tab. Vindol. 343, whose author, Octavius, could have been a civilian or in the military, also contains a number of substandard spelling features (see p. 262), but also <k> for /k/ before /a/, and <xs>. The single example of <ss> in nissi is interesting because there was never an etymological *-ss- in nisi, which comes from the univerbation of *ne sei̯. However, since this univerbation must have occurred after rhotacism, nisi presumably contained an intervocalic voiceless /s/, a feature shared almost exclusively with forms like mīsī < mīssī, where it was the result of degemination of original /ss/. The writer of 343 must have learnt the spelling with <ss> and mistakenly overgeneralised it to nisi.

We can conclude that the spelling <ss> for /s/ after a long vowel or diphthong is common at Vindolanda (nearly half the examples). It correlates with other old-fashioned spellings such as <uo> for /wu/, <xs> for <x>, and <k> for /k/ before /a/. However, it does not correlate with quality of spelling: although it is used by the well-educated Cerialis, it also appears in texts which also feature substandard spellings, and in texts which are not necessarily written by military scribes.

Reference Cotugno, Marotta and MolinelliCotugno and Marotta (2017) argue against <ss> at Vindolanda being an old-fashioned feature, on the basis that since <ss> is found in accounts as well as letters, it cannot have been used as a stylistic marker, as might be the case in letters, and consequently that its use should not be considered an archaism. They suggest that instead it arose as a way of marking a voiceless tense /s/ among Batavian speakers of Latin (North-Western Germanic languages having, like Latin, turned original voiceless *s into /r/ by rhotacism); in this view, therefore, the use of <ss> would reflect Germanic interference in the Latin spoken by the Batavians at Vindolanda. But this is unlikely for several reasons. Firstly, given that (almost) all examples of <ss> are etymologically correct, Occam’s razor would lead us to prefer old-fashioned spelling as an explanation; secondly, spellings with double <ss> are found in other corpora where Germanic influence is not to be suspected (albeit mostly at lower rates); thirdly, other old-fashioned features, such as use of <xs> (Chapter 14) and <uo> for /wu/ (Chapter 8) are also found in documents other than letters; fourthly, it is implausible that the highly educated Cerialis, who otherwise spells in a completely standard manner and uses other old-fashioned features (<uo>), should have used a non-standard spelling solely in the use of <ss>; fifthly, at least three of the documents containing <ss> originate from civilian authors, who were therefore probably not Germanic speakers; these may of course have been written by military scribes but they might well not have been. The argument also rests on the implicit assumption that old-fashioned spelling is a variable that differs according to the register of text in which it is found. This may, but need not, be true, and requires demonstration rather than being a premise.

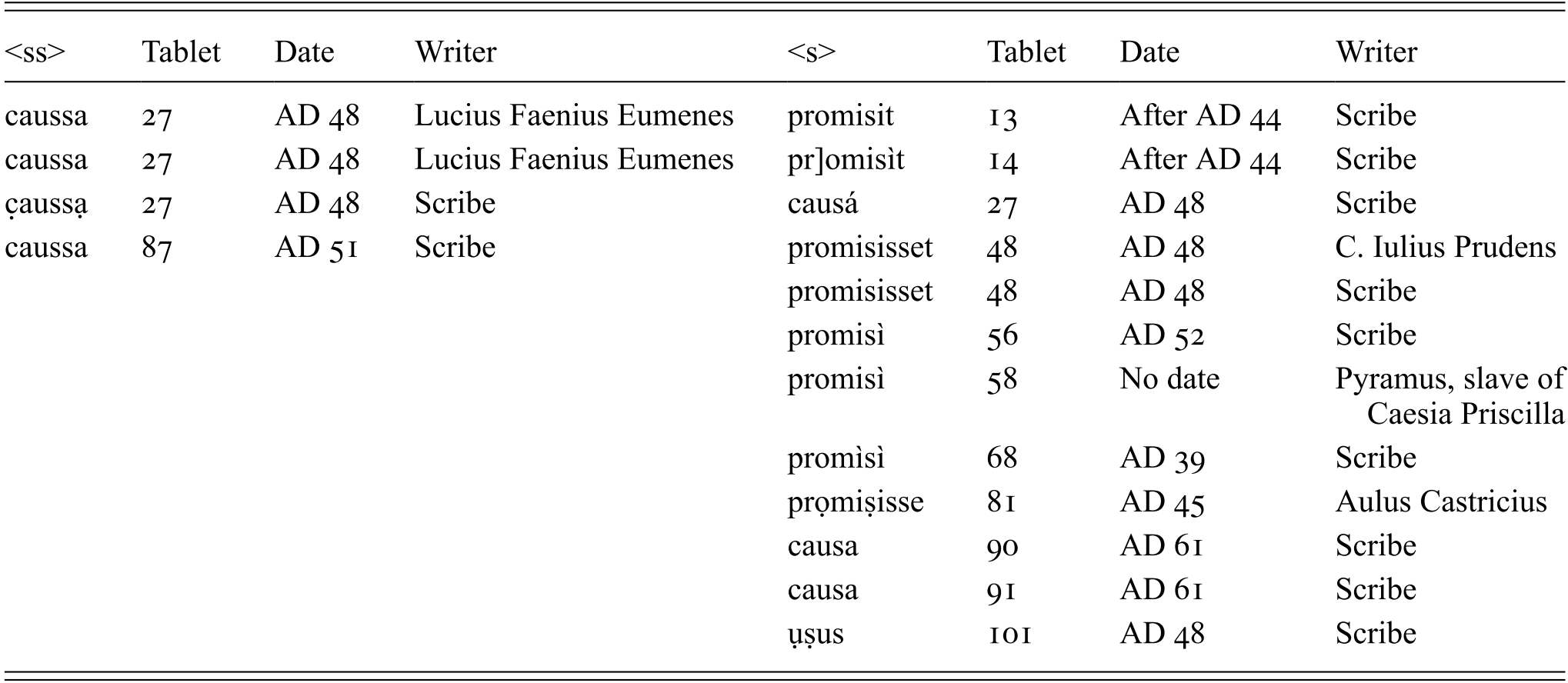

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, apart from in the sections written by C. Novius Eunus, which I consider separately below, spellings with <ss> are outnumbered by those with <s>: there are 4 instances, all of caussa, and 12 of <s> (25%); however, two of the instances of <ss> belong to a single writer, Lucius Faenius Eumenes, and another is found in the scribal portion of the same tablet (one wonders if the scribe, who also uses <s> in causá, could have been influenced by the spelling of Faenius). The clustering of examples of <ss> in causa and not in other lexemes seems to fit with the usage of the epigraphic evidence as a whole (see Table 26).

Table 26 <ss> and <s> in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| <ss> | Tablet | Date | Writer | <s> | Tablet | Date | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| caussa | 27 | AD 48 | Lucius Faenius Eumenes | promisit | 13 | After AD 44 | Scribe |

| caussa | 27 | AD 48 | Lucius Faenius Eumenes | pr]omisìt | 14 | After AD 44 | Scribe |

| c̣aussạ | 27 | AD 48 | Scribe | causá | 27 | AD 48 | Scribe |

| caussa | 87 | AD 51 | Scribe | promisisset | 48 | AD 48 | C. Iulius Prudens |

| promisisset | 48 | AD 48 | Scribe | ||||

| promisì | 56 | AD 52 | Scribe | ||||

| promisì | 58 | No date | Pyramus, slave of Caesia Priscilla | ||||

| promìsì | 68 | AD 39 | Scribe | ||||

| prọmiṣisse | 81 | AD 45 | Aulus Castricius | ||||

| causa | 90 | AD 61 | Scribe | ||||

| causa | 91 | AD 61 | Scribe | ||||

| ụṣus | 101 | AD 48 | Scribe |

Eunus shows a consistent double writing of intervocalic /s/, regardless of whether it results from original /ss/ or not. Once again, this will be an overgeneralisation of the rule that <ss> is to be written for /s/ in many words after a diphthong or long vowel to apply to all instances of /s/ (Reference AdamsAdams 1990: 239–40; Reference Seidl and RosénSeidl 1996: 107–8).Footnote 6 Thus, in addition to promissi (TPSulp. 68), where <ss> is etymologically correct, he consistently spells the name Caesar with <ss> (51; 52, 3 times; 67, twice; 68, 3 times), generally does so for the name Hesychus (51, twice, 52, twice, 68 once, but twice with <s>), and also uses double <ss> in writing Asinius (67) and positus (51; 52, twice).

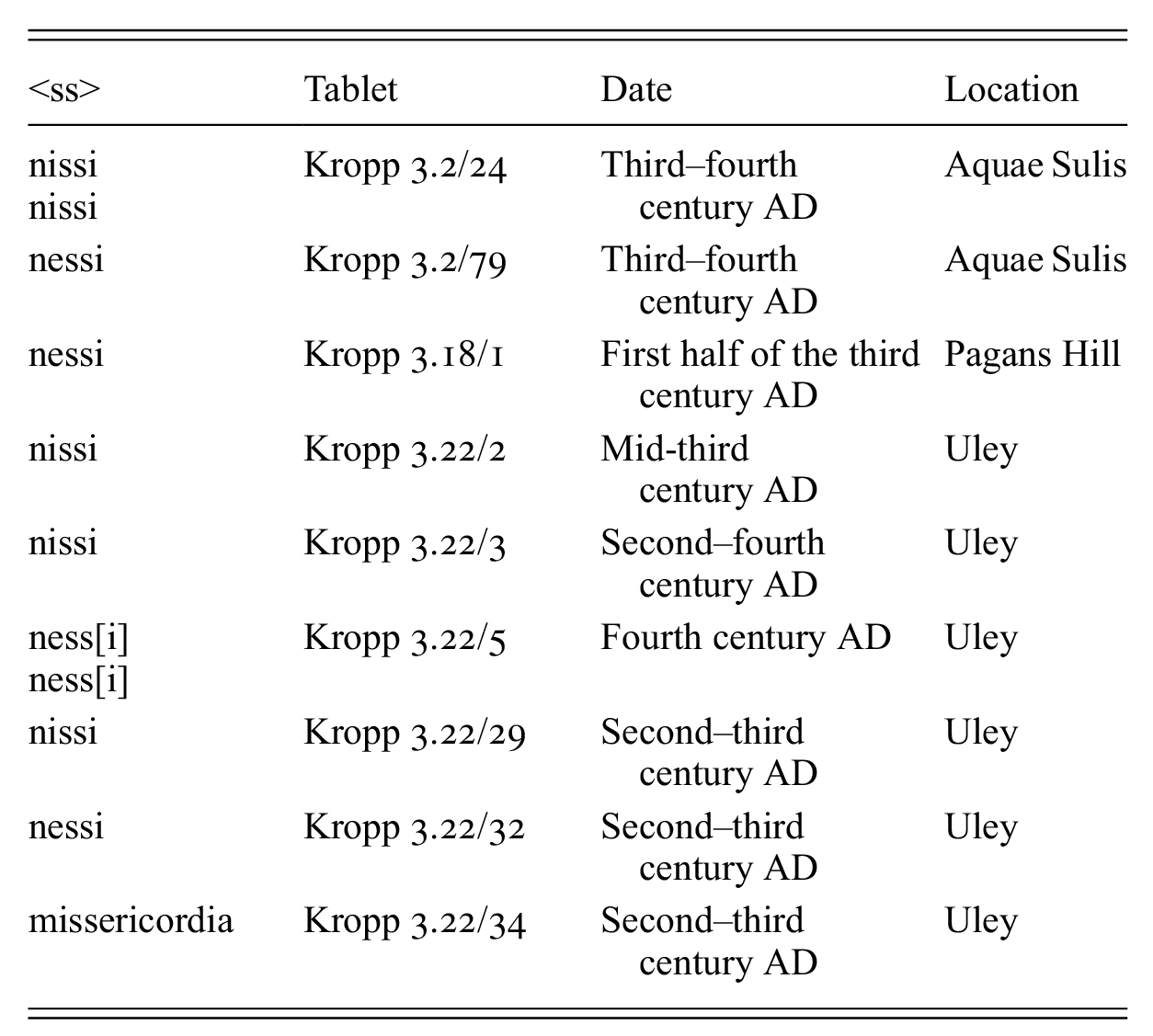

In the curse tablets, all instances of etymological <ss> are spelt with single <s> (7 examples, 3 of amisit,Footnote 7 4 of causaFootnote 8), but Britain, and in particular Uley, provides a large number of instances of non-etymological <ss>, particularly in the word nisi (see Table 27).Footnote 9 Should we explain double <ss> in nissi/nessi as the result of failure to learn (or teach) the rule whereby some words with /s/ are written with <ss> due to degemination after a long vowel, as with Eunus? Or should we posit some other local development, whether that be an educational tradition or influence on pronunciation from a second language (presumably Celtic)?

Table 27 Unetymological <ss> for /s/ in the curse tablets

| <ss> | Tablet | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kropp 3.2/24 | Third–fourth century AD | Aquae Sulis |

| nessi | Kropp 3.2/79 | Third–fourth century AD | Aquae Sulis |

| nessi | Kropp 3.18/1 | First half of the third century AD | Pagans Hill |

| nissi | Kropp 3.22/2 | Mid-third century AD | Uley |

| nissi | Kropp 3.22/3 | Second–fourth century AD | Uley |

| Kropp 3.22/5 | Fourth century AD | Uley |

| nissi | Kropp 3.22/29 | Second–third century AD | Uley |

| nessi | Kropp 3.22/32 | Second–third century AD | Uley |

| missericordia | Kropp 3.22/34 | Second–third century AD | Uley |

The former seems more likely: it may seem remarkable that (mis)use of <ss> should cluster around this word in particular, but its frequency is probably just the result of the formulaic nature of the curse tablets: in the curse tablets from Britain it is common for the curse to threaten a thief with unpleasant punishments unless (nisi) the property is returned either to the owner (thus Kropp 3.22/2, Kropp 3.22/29) or to a temple (Kropp 3.2/24, Kropp 3.18/1, Kropp 3.22/3, Kropp 3.22/5). An alternative formula is that the thief is given as a gift to the god, and ‘may not redeem this gift except (nisi) with his own blood’ (3.2/79, 3.22/32). And in most of the tablets there are no other examples of single /s/, so we cannot say that it is only nisi which receives this treatment, while in 3.22/4, the only example is missericordia for misericordia ‘pity’, which is also spelt with a geminate.

However, there are two cases where /s/ is spelt singly in tablets which also have <ss> after a short vowel; in 3.22/3 there is also amisit, which has <ss> etymologically, and in 3.22./34 there is thesaurus, which does not have etymological <ss>, but which might be expected to be spelt with <ss> if the writer had generalised the rule that all instances of /s/ were to be spelt <ss>. But it is also possible that the writers of these tablets were simply inconsistent in their spelling.

The use of <ss> correlates with <xs> in 3.2/24 (paxsam ‘tunic’, but [3]xe[3]), 3.33/3 (exsigat ‘may (s)he hound’ twice, but laxetur); in both the spelling is not far from the standard, although the former has Minerue for Mineruae and the latter lintia for lintea. Most of the tablets have some substandard features in addition to <ss> after a short vowel:Footnote 10 Minerue for Mineruae, serus for seruus, redemat for redimat, nessi for nisi (3.2/79), [di]mediam for dīmidiam, nessi for nisi (3.18/1), coscientiam for cōnscientiam (3.22/5),Footnote 11 tuui for tuī, praecibus for precibus, pareat for pariat (3.22/29), redemere for redimere (3.22/32).

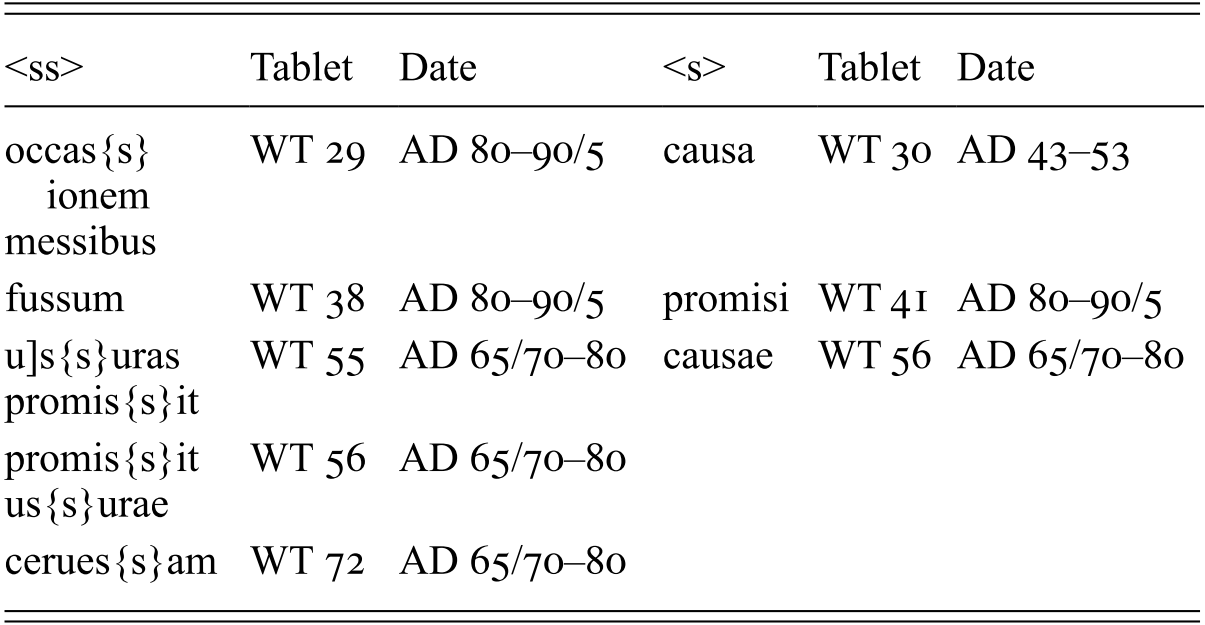

In the London tablets (see Table 28), <ss> shows a remarkably high distribution, including in tablets relatively late in the first century AD; WT 56 includes two spellings with <ss> (promissit, ussurae) and one with <s> (causae). In addition there is mistaken use of <ss>, in messibus (WT 29) for mēnsibus ‘months’, which would have been pronounced [mɛ̃ːsibus] and hence appeared to be a case of single /s/ after a long vowel, where only one <s> is found in the 4 other instances of the same word in this tablet. The word ceruesa ‘beer’ is generally supposed to have been borrowed from Gaulish, and there is no evidence that it ever contained double /ss/. Four other instances in this tablet are spelt with single <s>. If the reading is correct, this would be an example of use of <ss> for /s/ after a short vowel. Once again, this is a corpus which has high frequency of the spelling <xs>.

Table 28 <ss> and <s> in the London tablets

| <ss> | Tablet | Date | <s> | Tablet | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT 29 | AD 80–90/5 | causa | WT 30 | AD 43–53 |

| fussum | WT 38 | AD 80–90/5 | promisi | WT 41 | AD 80–90/5 |

| WT 55 | AD 65/70–80 | causae | WT 56 | AD 65/70–80 |

| WT 56 | AD 65/70–80 | |||

| cerues{s}am | WT 72 | AD 65/70–80 |

In the tablets from Herculaneum, geminate <ss> is only found in the name Nassius (TH2 A3, D13, A16, 4),Footnote 12 where the spelling change may have been retarded in a name (cf. causam TH2 89, proṃisi A10, repromisisse 4, all 60s AD). In the letters, the only possible instances of <ss> being used after a long vowel or diphthong is bessem ‘two thirds (of an as)’ in CEL (72) in a papyrus letter of AD 48–49 from Egypt. I think the preceding vowel was probably long, but cannot be certain.Footnote 13 Otherwise, 31 other instances show <s>.Footnote 14

In the Isola Sacra inscriptions there are instances of causa (IS 57), laesit (IS 10), manumiserit (IS 320), permisit (IS 142 and 179) and, with <ss>, the word crissasse (IS 46) for crīsāsse ‘(of a woman) to move the haunches as in coitus’ (in a graffito written on a tomb; not earlier than the reign of Antoninus). The word is otherwise found with a single <s> at AE 2005.633 (second half of the second or early third century AD) and Reference Solin and KarivieriSolin (2020, no. 24a). An original geminate is implied by the absence of rhotacism, and is found in Martial and in the grammarians (TLL 1206, s.v. crīsō).Footnote 15

At Bu Njem there is no sign of the <ss> spelling, but 17 examples of original /ss/ with <s>. At Dura Europos there are 5 examples of (a)misit; there are no examples of a double spelling for an old geminate.

<ll> and <l>

Double /ll/ was degeminated after a diphthong, as in paulus < paullus ‘little’, caelum ‘sky’ < *kai̯d-(s)lo- (Reference Weiss, Jamison, Melchert and VineWeiss 2012: 161–70) and between [iː] and [i], as in uīlicus ‘estate overseer’ beside uīlla ‘estate’, mīlle ‘thousand’ beside mīlia ‘thousands’ (Reference MeiserMeiser 1998: 125).Footnote 16 The latter change had taken place by the second half of the first century BC.Footnote 17 The standard spelling for mīlia and mīlibus retained the double <ll> until late in the first century AD. Not including the TPSulp. tablets, I find 27 inscriptions containing these spellings dated to between AD 14 and 100 (many of which would be characterised as official),Footnote 18 and only 11 in this period with the spelling milia, miliarius, milibus.Footnote 19

The only reference to the geminate spelling in this context in the writers on language which I have found is by Terentius Scaurus, who actually recommends the double spelling:

uerum sine dubio peccant qui ‘paullum’ [et Paullinum] per unum ‘l’ scribunt …

There is no doubt that those who write paullus with one l are wrong …

The corpus with the greatest number of relevant forms is the tablets of the Sulpicii, all in the word mīlia, mīlibus ‘thousands’.Footnote 20 By comparison to the use of <ss>, where <s> is favoured by both scribes and writers other than Eumenes and Eunus, <ll> appears to be the standard for milia and milibus in the tablets, in agreement with the rest of the epigraphic evidence.Footnote 21 In Table 29 there are 30 instances of these words being spelt with <ll>, by both scribes and others; none of the 11 instances of spelling with <l> are by scribes; 9 of them are by C. Novius Eunus, whose spelling is highly substandard (see p. 262).

Table 29 <ll> and <l> in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| <ll> | Tablet (TPSulp.) | Date | Written by | <l> | Tablet (TPSulp.) | Date | Written by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| millia | 22 | AD 35 | Aulus Castricius Celer |

| 51 | AD 37 | C. Novius Eunus |

| ṃillia | 46 | AD 40 | Nardus, slave of P. Annius Seleucus |

| 52 | AD 37 | C. Novius Eunus |

| millia | 46 | AD 40 | Scribe | m[i]lia | 76 | No date | C. Trebonius Auctus |

| miḷḷị[bus | 49 | AD 49 | Scribe | milia | 82 | AD 43 or 45 | L. Patulcius Epaphroditus |

| 51 | AD 37 | Scribe | ||||

| 53 | AD 40 | L. Marius Jucundus | ||||

| millia | 53 | AD 40 | Scribe | ||||

| 54 | AD 45 | Scribe | ||||

| 57 | AD 50? | Scribe | ||||

| 58 | No date | Pyramus, slave of Caesia Priscilla | ||||

| millia | 59 | No date | Unknown non-scribe | ||||

| mìllia | 66 | AD 29 | M. Caecilius Maximus | ||||

| 69 | AD 51 | C. Sulpicius Cinnamus | ||||

| millia | 71 | AD 46 | C. Julius Amarantus | ||||

| 74 | AD 51 | Scribe | ||||

| millia | 77 | AD 58 | C. Caesius Quartio | ||||

| 79 | AD 40 | Scribe | ||||

| milliạ | 98 | AD 43 or 45? | Q. Poblicius C[…] | ||||

| ṃillibus | 108 | No date | Unknown non-scribe |

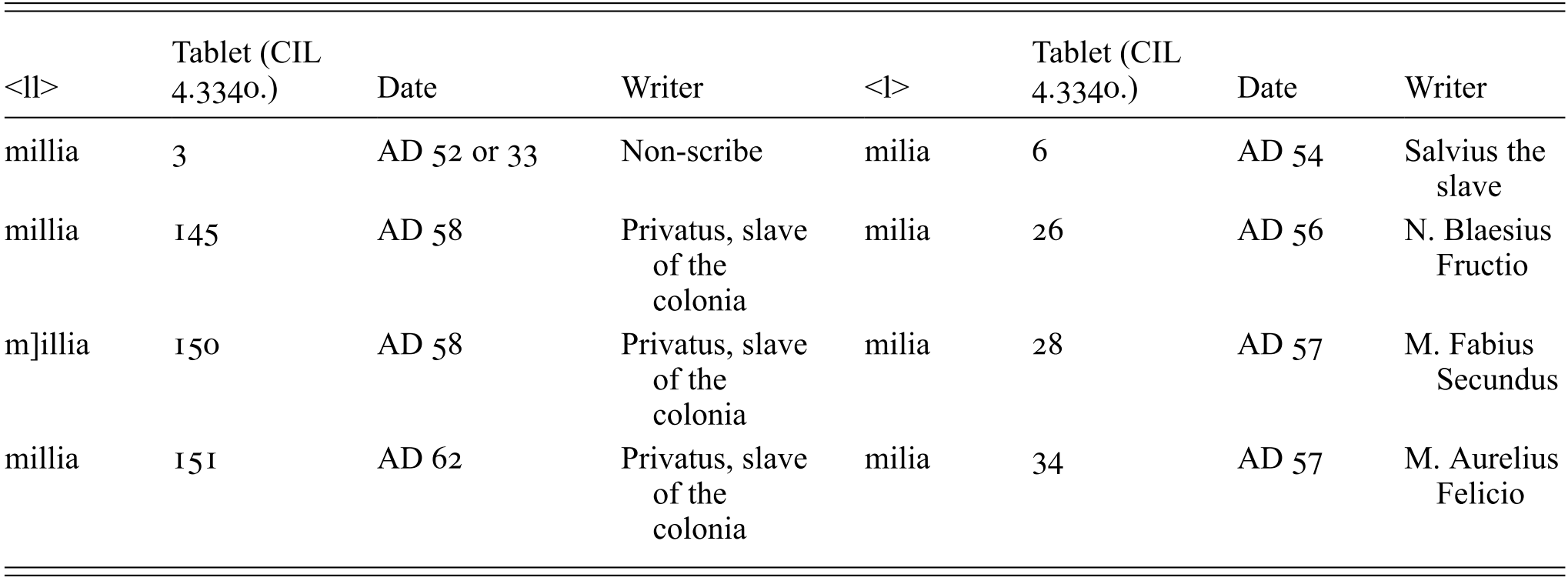

In the Caecilius Jucundus tablets, the balance between <ll> and <l> in millia ~ milia is much more even, with 4 instances of each spelling (Table 30). It looks rather as if use of milia tends to correlate with less standard spelling, and millia with more standard spelling, as we might expect if millia is standard. There are no instances of this word written by scribes. The writing of N. Blaesius Fructio (CIL 4.3340.26), who uses milia, is highly substandard (see p. 9 fn. 11). That of Salvius the slave (6) is much better, but omits final <m> in a number of words (see p. 262). M. Fabius Secundus (28) omits all final <m>: de]ce(m), auctione(m), mea(m), tabellaru(m), s[ign]ataru(m). In what is left of the writing of M. Aurelius Felicio (34), the spelling is largely standard, but he does omit the <n> in duce(n)tos.

Table 30 millia and milia in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets

| <ll> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340.) | Date | Writer | <l> | Tablet (CIL 4.3340.) | Date | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| millia | 3 | AD 52 or 33 | Non-scribe | milia | 6 | AD 54 | Salvius the slave |

| millia | 145 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | milia | 26 | AD 56 | N. Blaesius Fructio |

| m]illia | 150 | AD 58 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | milia | 28 | AD 57 | M. Fabius Secundus |

| millia | 151 | AD 62 | Privatus, slave of the colonia | milia | 34 | AD 57 | M. Aurelius Felicio |

By comparison, in tablet 3 there is little remaining of the writing of the non-scribe but the spelling is standard. Privatus, slave of the colonia, who writes the other tablets with millia, has largely standard spelling as well as the old-fashioned spellings seruos (142) and duomuiris (144). He does, however, have occasional deviations from the standard: Hupsaei, Hupsaeo for Hypsaei, Hypsaeo (tablets 143, 147 respectively), pasquam for pascuum (145, 146), pasqua for pascua (147).

In the tablets from Herculaneum, there are two instances of <ll> in this lexeme (millibus, TH2 52 + 90, interior; mi]ḷḷịḅụṣ A10, interior), both from the 60s AD, and none of <l>. The spelling with <ll> is also found in the name Pa]ullịṇạe (62).

In the letters the only case of <ll> is the name Paullini (CEL 13); I have found no other instances of original /ll/ after a long vowel or diphthong. At Vindolanda there is one instance of milia without a geminate (Tab. Vindol. 343 – the letter of Octavius, whose writing is characterised by both old-fashioned and substandard spelling; p. 262). The curses have paullisper (Kropp 1.5.4/3) in a curse tablet from Pompeii and hence no later than AD 79, whose spelling is entirely standard, but Paulina, 8.4/1, from the mid-second century AD, and milibus in 3.10/1 and 3.18/1, both from third century AD Britain. At Bu Njem there are no examples of original /ll/, and at Dura Europos there is only 1 example of the name Paulus. In the Isola Sacra inscriptions there is milia (IS 233, dated to the reign of Hadrian), and the names Paulus (176), Paulino (IS 288) and Paulinae (IS 343). This compares with one example of the <ll> spelling in the name Paullinae (IS 90).

Singletons for Geminate Consonants after Original Long Vowels

There were (at least) two sporadic rules which produced geminate consonants in the original sequence (*)VːC > VCC (Reference WeissWeiss 2010; Reference SenSen 2015: 42–78). One of these affected high vowels followed by a voiceless consonant, in forms like Iūpiter> Iuppiter. Since long /iː/ and /uː/ from original *ei̯ and *ou̯ were affected, a terminus post quem for the change is the mid-second century BC. Another rule resulted in the sequence /aːR/ becoming /arr/ (Weiss), or synchronic variation between /aːR/ and /aRR/ (Sen).

According to Sen, the first rule was a diachronic change, while the variation between /aːR/ and /aRR/ was a continuing synchronic development. However, the exact status of the rules is difficult to establish, partly because the evidence of both manuscripts and inscriptions is not always easy to analyse or to date, partly because older spellings could continue to be used beside newer spellings, and partly because of the sporadic nature of the change: in the case of cūpa ‘cask’ and cuppa ‘cup’, both versions were maintained beside each other (and both continued into Romance), although with a semantic divergence. However, support for the Iūpiter-type rule being diachronic comes from the non-attestation of the long vowel variants of some words such as uitta ‘headband’ < *u̯īta. The evidence for the change involving /aːR/ is even weaker, but all the best examples (*pāsokai̯dā > parricīda ‘parricide’, gnārus ‘knowing’ beside narrāre ‘I tell’, parret ‘it appears’ besides (ap)pāreō ‘appear, be visible’) suggest a direction of change /aːR/ > /aRR/ and not vice versa, so I take it that this too is a diachronic change.

In the corpora there are two lexemes which contain these environments. The first is parret. The consistent long vowel in pāreō and its derivatives suggests that the long vowel was original in this word (Reference de Vaande Vaan 2008: 445). Festus says that it should be spelt with <r>, on analogical grounds, but noting that it appears particularly in contracts:

parret, quod est in formulis, debuit et producta priore syllaba pronuntiari, et non gemino r scribi, ut fieret paret, quod est inveniatur, ut comparet, apparet.

Parret, which is found in contracts, ought both to be pronounced with a long first syllable, and not to be written with double r, so that it becomes paret, which is inuieniatur ‘should it be proved’, as in comparet and apparet.

There is no clear chronological development in the attestations of parret and paret, but Festus does suggest that (in practice), the double <rr> spelling was found particularly in contracts, and, in our admittedly meagre data, there does seem to be a distinction between the impersonal usage with <rr> in legalistic contexts, while <r> was used in other senses and contexts. The <rr> spelling is attested in 87 BC in the Tabula Contrebiensis from Spain (CIL 12.2951a), the Lex riui hiberiensis, also from Spain, from the time of Hadrian (Reference Beltrán LlorisBeltrán Lloris 2006), and in a fresco depicting a wax tablet in a villa near Rome of around 60–40 BC (Reference Costabile, Angelelli, Musco, Baratta, Santarelli and FerraraCostabile et al. 2018: 78, and for the dating 22–3).Footnote 22 The spelling paret appears in the non-impersonal usage at CIL 12.915, CIL 13.5708, Kropp 4.4.1/1 (first century AD), and impersonal but not legalistic at CIL 3.3196 (dated to the second century by the EDCS: EDCS-28600186). The spelling parret (TPSulp. 31, scribe) is, therefore, not old-fashioned in the sense that the older form was probably pāret. However, it may be that its use with this spelling was specific to the legal/contractual context, and may therefore reflect particular training for this genre for the scribe.

The other relevant lexeme is littera, for which the non-geminate spelling is rare; leiteras (CIL 12.583, 123–122 BC) probably represents /liːtɛraːs/ (Reference SenSen 2015: 218), and one may add literas (CIL 12.3128; 100–50 BC, EDR102136), ḷịteras (Reference Castrén and LiliusCastrén and Lilius 1970, no. 266). The spelling with <tt>, on the other hand, is well attested inscriptionally, the earliest examples being litteras (CIL 12.588.10, 78 BC and CIL 12.590.1.3, 70s BC; Reference SenSen 2015: 218). In my corpora, the geminate is used in litteras in TPSulp. 46 (scribe, AD 40), 78 (non-scribe, AD 38) and 98 (non-scribe, AD 43 or 45). The geminate in litteras is found twice at Kropp 6.2/1, from Noricum. The spelling literae (Kropp 11.1.1.7, Carthage, first–third centuries AD) is probably a reflection of the writer’s inability to spell geminates correctly rather than an old-fashioned spelling (cf. posit for possit (twice), posu[nt for possunt, posint for possint, ilos for illōc). An early letter (CEL 9, last quarter of the first century BC), has ḷiteras; otherwise we find only littera- (CEL 13, AD 27, then 7 other examples, from the second to the fifth century). The spelling with a single <t> in CEL 9 might, however, be due to a general loss of geminates in this author, who also writes disperise for disperisse, sucesorem for sucessōrem, sufragatur for suffrāgātur, rather than reflecting an old-fashioned spelling.