1. Introduction

The resolve of the African Union (AU) to merge the currently existing African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACtHPR or Human Rights Court)Footnote 1 with the African Court of Justice (ACJ)Footnote 2 to form the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR) through the adoption of the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human RightsFootnote 3 (hereafter, Merger Protocol), no doubt began the redefinition and streamlining of the African Union organs, bodies or mechanisms. This streamlining or rationalization of institutions, or what this author would call the Merger Project, was predicated on the increasingly diminishing resources available to the continental body as this author has alluded to elsewhere.Footnote 4 The further decision that the AU Assembly took in 2014 in Malabo, Equatorial GuineaFootnote 5 to extend the jurisdiction of the ACtHPR to include international crimes (the so-called Malabo Protocol) is the latest dimension of the AU judicial institutions rationalization process. This decision thus creates one single court to be known as the African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACJHPR).Footnote 6 The extension of criminal jurisdiction to the Court has generated and continues to generate ample debates from a number of commentators – debates that range from the propriety and legality of such decision in the era of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the resource questions, to the political ramifications of the decision.Footnote 7

It is not the intention in this chapter to delve into the debate on the propriety, legality or otherwise of the AU decision to merge the ACJ with the ACtHPR, or its extension of the jurisdiction of the Human Rights Court to include international crimes. That debate is now stale and would therefore, serve no more meaningful purposes. This author had amply dealt with the issue in the years past.Footnote 8 Rather, this chapter, as the title suggests, focuses on the resources question relative to the significance of the African Union judicial mechanism as the composite judicial body of the Union. In other words, we must emphasize the reality that the ACJHPR when fully constituted, will be the main judicial organ of the African Union. The importance of this phenomenon cannot be overstated; it is indeed a big deal. While the composite court is not yet in force, it is important to engage at the strategic level on financing and sustaining the Court taking into account its significance and enormous role as a single Court. There may be the temptation to focus only on the resources needed to effectively sustain the criminal arm of the Court. That would not do justice to the significance and importance of the Court, as the holistic financing of the court must be the focus. It is also in the interest of continental norm creation and dispute resolution that a holistic emphasis is placed on the development of a robust continental judicial process that is adequately resourced. Thus, the chapter will be forward–looking; perhaps to provide the AU policy makers some food for thought in their planning in the continental body’s new scheme to ensure autonomous financing of the African Union and its institutions. The chapter will not go into the dollar and cents requirements of the ACJHPR, or the numerical staffing needs of the Court, as that would be practically impossible to do in this limited piece. That would require a holistic resource-focused study. The chapter will, however, provide a thematic discussion and evaluation of the resource needs of the Court taking into account its structure and applicable international practice and standards.

The chapter is divided into seven (7) sections. Following the above introductory section, section two deals with the notion of the ACJHPR as a single Court. The section flags the holistic nature of the court particularly because there may be a tendency to have a segregated view of the African Union’s judicial mechanism in the form of a separate Court of Justice, a Human Rights Court and more emphatically, an international criminal tribunal. Section three examines the adoption of the Malabo Protocol and tries to make sense of its adoption without a prior determination of the cost implication of the endeavour. Section four takes a thematic overview of the ACJHPR from a resource perspective. It examines the organic structure of the Court and juxtaposes that structure against the kind of resources that should be envisaged. In this regard, it highlights the Presidency of the Court, the Registry, Office of the Prosecutor and the Defence Office in terms of the enormity of the judicial project and its resource implications. Section five briefly discusses applicable examples of other judicial mechanisms in terms of the financial implication of organizing them. Such examples include the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the United Nations-backed Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the current African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACtHPR). Section 6 delves into what could be done to sustainably finance the ACJHR leveraging on the current reform of the African Union funding mechanism – the 0.2 per cent import levy on eligible imports into the continent. Section 7 concludes the chapter, emphasizing the significance of the current AU financing mechanism reform – the 0.2 per cent levy on eligible imports into the continent, as a great opportunity for effectively financing and sustaining the ACJHPR. The section calls on the AU to make provisions for the funding of the Court through a regular budget from member states’ assessed contributions, an endowment or trust fund from surpluses, and provision for voluntary contributions from willing member states and partners to cater for ad hoc needs and short-term resource requirements.

2. The ACJHPR as a Single and Composite Court

It must not be lost on any observer, commentator, or policy maker that the ACJHPR is a single Court and the main judicial organ of the African Union. As a result, any evaluation of its resource needs must begin from that perspective. The court as a single and composite court will have four Organs – a Presidency, an Office of the Prosecutor, a Registry and a Defence Office.Footnote 9 The Court will be made up of three Sections – ‘a General Affairs Section, a Human and Peoples’ Rights Section and an International Criminal Law Section’.Footnote 10 Specifically, the International Criminal Section is endowed with ‘a Pre-Trial Chamber, a Trial Chamber and an Appellate Chamber’.Footnote 11 Similarly, all the Sections are allowed to ‘constitute one or more Chambers in accordance with the Rules of [the] Court.’Footnote 12 The General Section of the Court has jurisdiction over disputes other than human rights questions and international crimes, which are accordingly within the purview of the Human Rights and International Criminal Law Sections, respectively. The reality of the above configuration of the Court is that, in effect, you have three courts fused into one. The strategic leadership of the Court revolves around the four organs enumerated above. The President of the Court would be assisted by a Vice PresidentFootnote 13; the Prosecutor will have two Deputies.Footnote 14 The Registry of the Court would be overseen by one Registrar who in turn would be assisted by three Assistant Registrars.Footnote 15 The Defence Office would be presided over by the Principal DefenderFootnote 16 with requisite staff complement to ensure the rights of accused persons or others that may require legal assistance.

The above structure of the Court shows the enormity of the African Union’s ambitious judicial project. It is in the interest of the African Union that this judicial project is realized if it should be taken seriously in fully implementing the noble aspirations contained in the AU Constitutive Act. The fact that the African Court of Justice was not operationalized despite the entry into force of the Protocol on the ACJFootnote 17 adopted pursuant to Article 18 of the Constitutive Act – due to the Merger Project, calls for a meaningful engagement and credible efforts to bring the Malabo Protocol into force.

3. Adopting the Malabo Protocol without Cost Implications

Some may, for argument sake, contend that it was imprudent on the part of the African Union to adopt the Malabo Protocol without first ascertaining the cost implications of implementing the objectives and provisions of the Protocol, which was mainly to extend the jurisdiction of the merged African Court of Justice and Human Rights to include international crimes. The same argument could be made regarding any other treaty negotiated by the African Union or any other interstate institution such as the United Nations (UN) or other regional organizations. It is not usually very easy to fully appreciate the cost implications of adopting any international agreement before such an agreement is adopted. Where such a forwarding financial thinking exists, it will no doubt make life very easy for the eventual implementation of the objectives of an intended treaty. This author would, however, think that the paramount issue would be whether there is a strong collective will to undertake a particular objective through the adoption of a treaty or an international agreement. The crystallization of that objective through the actual adoption of the treaty should provide the impetus for working out the cost implication of its implementation within the timeline of preparation for its entry into force.

In the case of the Malabo Protocol, this is even more so applicable. It needs recalling that the implementation of the Protocol on the Court of Justice of the African Union despite its entry into force, was aborted by the Merger Project leading to the adoption of the Merger Protocol, which also is yet to enter into forceFootnote 18 and which also had its own structures. During preparations for the adoption of the Malabo Protocol that eventually brought everything together, there was an attempt to evaluate the final implication of its implementation. When the Protocol was presented during the AU Summit of January 2013, it was not decided upon by the AU Assembly. The Executive Council, which normally prepared for the meeting of the Assembly rather decided that a report on the financial and structural implications of adopting the Protocol, among other issues, should be prepared and reported on at the following midyear Summit.Footnote 19 The eventual adoption of the Protocol in Malabo in July of 2014 was not faced with the same fate of first elucidating on the financial and structural implications before it was adopted. The urgency of adopting the Protocol in the face of the increasing strong concerns of the African Union Assembly about the activities of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in Africa would have primarily worked on the minds of the Assembly in this regard. This author who had become Legal Counsel of the African Union during the period in November 2013, was also of the opinion that it would not be very helpful to hurry a report on the structural and financial implications of the Protocol before its adoption. The reason was simple; it was necessary that the report on the financial implications should be well informed by a thorough study between the adoption of the Protocol and its entry into force based on the finally adopted Protocol. I was of the view that an initial assessment hurriedly put together by a Consultant was not thorough enough and could not have taken adequate account of the Protocol that eventually emerged having regard to the composite character of the Court and available best practices. It mainly focused on the financial implications of extending criminal jurisdiction to the existing ACtHPR.Footnote 20 In terms of the structural implications of the Court, the court’s structure is now very clear based on its organic composition from which a clear assessment of personnel and resource needs could be made taking into account international courts of a similar nature.

While awaiting the ratification and entry into force of the Malabo Protocol, it is now vital for a comprehensive study on the financial implications of the ACJHPR to be undertaken where an evaluation of the resource needs of the various sections of the Court would be made. That study will now benefits from an adopted Protocol, whose structure is set. Thus, the General, Human Rights and International Crimes Sections as the fused components of the Court would be thoroughly examined to ensure effective resource allocation. This is even more important now that the African Union has launched its reform agenda with a strong focus on effectively and adequately financing the African Union. At its Twenty-Seventh Ordinary Summit in Kigali, Rwanda in 2016, the AU Assembly took a Decision to finance the African Union ‘in a predictable, sustainable, equitable and accountable manner with the full ownership by its Member States’.Footnote 21 The Decision created a new mechanism for funding the African Union – instituting and implementing ‘0.2 percent Levy on all eligible imported goods into the Continent to finance the African Union Operational, Program and Peace Support Operations Budgets starting from the year 2017’.Footnote 22 A committee of African Union Ministers of Finance made up of ten ministers, two from each AU region (referred to as the F10) is charged with working out the implementation of the 0.2 per cent levy to ensure adequate and sustainable funding of the African Union by being involved in the budgetary process.Footnote 23 This reform of the AU is led by President Paul Kagame of Rwanda who recently became the Chairperson of the AU Assembly. President Kagame presented his report to the AU Assembly in January 2017.Footnote 24

There is no doubt that the reform of the African Union, particularly the way it is funded has implications for the financing of the judicial arm of the African Union – the ACJHPR, and in a more sustainable manner. It becomes imperative for AU policy makers to look at Financing the Union in a very holistic way that pays deliberate attention to the Court in the same manner as it does to peace support operations within the renewed emphasis on the ‘Peace Fund’, which the Assembly financing Decision recognizes as having ‘three (3) thematic windows, namely Mediation and Preventive Diplomacy; Institutional Capacity; and Peace Support Operations’Footnote 25 The Merger Project is a huge initiative and must be realized. It will involve enormous resources, which resources need to be available based on a deliberate, proper and systematic planning. The question then is how does the AU assess such resource requirements to sustainably finance the Court? In this regard, there is need for a systematic evaluation of what the composite Court involves. This will bring out a clear picture of the various compartments of the Court from where a sense of the resource requirements could be established.

4. Thematic Overview of the ACJHPR’s Structure from a Resource Implications Perspective

While I continue to emphasize that the ACJHPR is a single Court, it is indeed a composite court that literally combines three courts together – the initially planned Court of Justice of the African Union, the currently existing African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the Malabo Protocol’s creation – the International Criminal arm. An appreciation of this composite nature of the Court will be very helpful in evaluating the resource needs of the Court because of the diverse expertise needed for the Court to fully perform its role and to achieve its mandate. It will thus be useful to examine the organs of the Court and each of the Sections and juxtapose them against what may be required in its sustainable financing.

A. The Presidency

The Presidency is the organ that represents the judicial and political leadership of the Court and generally oversees the strategic operation of the Court. It oversees the judges of the Court. It is a collective of the judges of all the Sections of the Court – the General Affairs, Human Rights and International Criminal Law Sections. The Court when fully constituted will be made up of 16 Judges elected by the African Union Assembly from its five AU Regions who would serve for a single term of nine years.Footnote 26 In the configuration of the Court and based on how the Judges are elected, the General Affairs and Human Sections will be composed of five (5) Judges each while the International Criminal Law Section will have six (6) JudgesFootnote 27. The Presidency will be led by the President of the Court who together with the Vice President will be elected by all the judges for a terms of two years renewable once.Footnote 28 Of the 16 Judges of the Court, only the President and the Vice President would initially serve full-time.Footnote 29 It is envisaged that all the Judges of the Court could serve on a full-time basis but at such a time that would be determined by the AU Assembly based on the Court’s recommendation.Footnote 30

From a resource perspective, it means that, taking into account Article 23 of the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights on the remuneration of the Judges, provisions have to be made for the Presidency in a manner that firstly takes into account the salaries or allowances of the Judges for the initial period where they are largely expected to serve on a part-time basis except for the President and the Vice President who would always serve full-time and also envisaging the resource needs for when all the judges would be required to serve full-time. There is no doubt that the caseload of the Court, among other considerations, would determine whether the Court continues to function on a part-time basis over a long term or a much shorter period in terms of the salaries and allowances of the Judges. If the experience of the currently existing African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights is anything to go by, it can provide some lessons for the future.Footnote 31 Only the President of the Human Rights Courts serves on a full-time basis and in just 12 years of its existence, the caseload and other activities of the Court have increased tremendously. In 2016 alone the Court received 59 cases and 2 advisory opinion requestsFootnote 32. Effectively delivering on its judicial mandate and timely so, may be impacted by the part-time nature of the Judges’ work, as they are also generally involved in other occupations. Secondly, the Presidency would require formidable administrative support befitting of its role and mandate. The 16 Judges will require competent legal officers, assistants and secretaries, among other essential personnel. Such support staff complement for the Presidency must be clearly assessed taking into account the various stages of the Court’s development. Extrapolating from the currently existing Human Rights Court would be helpful even though the current Human Rights Court is only made up of 11 Judges, five Judges shy of the 16 required for the ACJHPR.

B. The Registry

In the workings of a judicial institution such as a Court, the Registry is literally the engine room where the administrative functioning of the Court is overseen. Without an effectively equipped and functioning Registry it will be very difficult for a court to deliver on its mandate. For the ACJHPR, the Registry is a vital organ of the Court. Article 22B (1) of the Statute of the ACHPR provides for a Registrar to lead the Registry supported by three Assistant Registrars. It is no coincidence that the Statute makes provision for three Assistant Registrars within the Registry. The three distinct Sections of the Court that have various jurisdictional mandates will surely require jurisdiction-specific attention in the way the Registry functions. The General Affairs Section, which is mainly a civil jurisdiction arm of the Court would require registry expertise in civil processes thus requiring an Assistant Registrar to oversee that arm. In the same vein, the Human Rights Section would need an Assistant Registrar to manage the human rights processes of the Court in the same way that the International Criminal law Section would require an Assistant Registrar versed in criminal processes. The Registrar would serve for a single term of seven (7) years while the Assistant Registrars would for a term of four (4) years renewable once.

Because of the importance of the Registry to the holistic administrative operations of the Court, it is important to properly assess its resource needs. There will be such departments or units within the Registry that are a sine qua non to a composite Court in the nature of the ACJHPR. Apart from the immediate office of the Registrar, there is the larger administrative services department that will be responsible for general recruitment/human resources, finance and budget, facility maintenance, procurement and the like. There will also be the language services department that will be responsible for ensuring translation of documents and the interpretation of proceedings in the various working languages of the African Union. The importance attached to a judicial process that makes for effective participation by litigants or respondents from various legal and language traditions cannot be over-emphasized. There will also be a witness and evidence unit or department that would further be arranged in terms of the civil, Human Rights and criminal dimensions of the Court. This will require a Victims and Witness Unit as well as a Detention Management Unit to specifically account for the international criminal law requirements of the Malabo ProtocolFootnote 33.

The various components of the Registry highlighted above require enormous resources that must be deliberately put in place for a credible ACJHPR to exist and to be taken seriously. It is therefore very important that AU policy makers pay attention to the detail. The detail from the beginning is important for a sustainable financing model to be arrived and applied over the years taking into account the stage of the Court in terms of its caseload and other activities over time.

C. Office of the Prosecutor

The extension of the jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to international crimes that led to the adoption of the Malabo Protocol effectively created an international criminal tribunal of the African Union. In contemporary international criminal adjudication, enormous resources are required to run such courts. Article 22A of the Malabo Protocol provides for the Office of the Prosecutor which is composed of a Prosecutor and two Deputy Prosecutors who would all be elected by the Assembly of the African Union.Footnote 34 The Prosecutor’s term of office will be one term of seven (7) years while the terms of office of the Deputy Prosecutors will be for four (4) years each, renewable only one.Footnote 35 The Statute vests the Office of the Prosecutor with the responsibility to prosecute and investigate the proscribed crimes.Footnote 36 The Statute requires the Prosecutor to be assisted by such staff as are necessary for the effective and efficient discharge of the mandate and responsibility of the office.Footnote 37

For the ACJHPR to be a credible Court from the perspective of its criminal justice mandate, it must be equipped to deliver quality justice through the efficiency of its prosecutorial arm. The ability of the Office of the Prosecutor to do this is dependent on how it is resourced on two fronts – it investigative and prosecution mandates. It is in this regard that the Prosecutor is assisted by two Deputy Prosecutors – one to oversee investigations and the other the prosecution. The experience of the United Nations-backed Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSC)Footnote 38, the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)Footnote 39, the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia (ICTY)Footnote 40, the International Criminal Court (ICC)Footnote 41, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL), and most recently, the Extraordinary African Chambers (EACs)Footnote 42, clearly shows that the work of the prosecutor is dependent on robust investigations and efficient prosecution of the alleged crimes. Apart from the general staffing and resources for the immediate or front office of the Prosecutor, ample resources will be required for properly equipping both the investigations and prosecutions departments. The number of staff as well as resources required for the various departments in the Office of the Prosecutor would of course be dependent on the stage of the Court’s work, requiring a short-term and a long-term outlook. Thus, conscious preparations must be made to determine what would be need in the short, immediate and long terms for the office of the Prosecutor.

D. The Defence Office

A lot of emphasis is usually placed on the Prosecution of accused persons resulting in enormous resources being at the disposal of the Prosecutor with little attention paid to defence issues. The importance of ensuring the rights of accused persons in international criminal justice adjudication necessitated the need to interrogate the level of attention paid to those who undergo criminal trials in international justice mechanisms as envisaged in the Malabo Protocol. The initial main and substantive attention in this regard was the eventual creation of the Office of the Principal Defender of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which I had referred to elsewhere as the watershed in international criminal justice adjudication.Footnote 43 The mandate of the SCSL Defence Office in accordance with Rule 45 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the SCSL was to ensure ‘the rights of suspects and accused’ persons. That office carried out its mandate by providing initial advice, attending detention issues, providing legal assistance as may be ordered by the court, ensuring that facilities were made available to counsel for the defence of the accused, maintaining a roster of counsel that could be called upon to defend the accused and its personnel acting as duty counsel for the accused as me required, among various other things.Footnote 44 While the SCSL may have blazed the trail in flagging the importance of defence issues in international criminal justice, its Defence Office was not independent but subject to the administrative oversight of the Registrar of the Court. The ICC would later establish the office of the Principal Counsel for the Defence in the mould of the Principal Defender of the SCSL. It is the Special Tribunal for Lebanon that established a fully independent Defence Office as an OrganFootnote 45 within the principle of equality of arms between the Prosecution and the Defence.

The Malabo Protocol has followed in the footsteps of the STL to make the Defence Office of the ACJHPR an Organ of the Court.Footnote 46 Article 22(C) of the amended Statute of the ACJHPR establishes the Defence Office as an independent Organ under the oversight of the Principal Defender, who would be appointed by the Assembly of the African Union. He or she would be assisted by such staff members as are required to enable the office to effectively and efficiently deliver on its mandate.Footnote 47 As envisaged in the Statute of the of the ACJHPR, the Defence Office, just like other Organs of the Court would require enormous human and other resources to be able to fulfil its mandate of watching over the rights of accused persons including acting as public defender for indigent accused persons or such accused persons that the interest of justice would require the provision of legal assistance. There is nowhere else that the functions of the Defence Office would be more useful than in Africa where the average accused person is generally indigent requiring the need for elaborate legal assistance. In operationalizing the ACJHPR, attention must be paid to fully resourcing the Defence Office, as it is expected to play a vital role right from the beginning of the process in the same way as the Prosecution.

The organic structure of the ACJHPR as described above is indicative of what operationalizing the Court involves and should inform what resource measures to put in place to have a credible court. For the African Union to be able to do this, it must evaluate the Court’s resource needs in the context of what the Court is expected to do, drawing lessons from what has been done elsewhere. In this regard, it may be important to look at the Court, though a single court, from its composite nature of three courts fused into one. From this perspective, it could be said that the General Affairs Section of the Court is a mini International Court of Justice (ICJ); the Human Rights Section, a mini Human Rights Court; and the International Criminal Law Section, a mini International Criminal Court. It is thus important to study and draw lessons from similar endeavours for indicative resource needs and how that could be sustained.

5. Resource Needs and Applicable Lessons

Sustainably providing for the ACJHPR is a huge endeavour and requires a deliberate effort on the part of the African Union. The continental organization must draw lessons from similar institutions such as the ICJ, the SCSL, the ICTR and the ACtHPR, to name a few. The ICJ was operationalized in 1947 as the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. It is composed of 15 judges and has more or less a general affairs jurisdiction with no Human Rights and international criminal justice jurisdictions as envisaged under the ACJHPR. Structurally, it has a Presidency and a Registry. In the almost 71 years of it existence, the ICJ had had only 168 cases listed in it General List.Footnote 48 The two-yearly budget of the ICJ for 2016 to 2017 was $ 52,543,900Footnote 49 and that of 2018 to 2019 is $46,963,700Footnote 50. There is no doubt that the ICJ has had limited judicial work compared to regional courts of a similar nature. It is generally funded within the United Nations system and thus through the regular general member states assessment.Footnote 51 Funding the ICJ through member states assessment ensures stability in the ability of the Court to function and to carry out its mandate.

The SCSL as an international criminal justice mechanism only dealt with international crimes. It had a somewhat similar structure as the International Criminal Law Section of the ACJHPR. While it dealt with and convicted only ten persons, its average annual budget was not low. As I have observed elsewhere, ‘As small as the SCSL operation was relative to the other [international criminal] tribunals, its annual budget averaged between 26 and 30 million dollars’Footnote 52 It is important to note that the funding of the SCSL was based on voluntary contributions – a not so good way of funding or sustaining any judicial or justice mechanism. The voluntary nature of funding the SCSL created an unhealthy anxiety from time to time regarding whether or not the Court would have adequate resources to continue to carry out its mandate.

The ICTR was the most significant international criminal justice mechanism to have operated on the African continent. As a mechanism designed to ensure legal accountability for the atrocities arising from the Rwandan genocidal war, it received enormous support having been established pursuant to a United Nations Security Council Resolution.Footnote 53 The ICTR indicted 93 individuals of which 62 were convicted and sentenced.Footnote 54 The Tribunal as an ad hoc measure operated for a period of over twenty years from 1994 to 2015 when it officially wound up and entered into a residual mechanism and it had an army of professional and general service staff. The proposed budget of the ICTR for the period 2004–2005 was $251.4 million,Footnote 55 which meant that the resources required for the functioning of the Court from its inception to when it formally wound up end entered into a residual mechanism phase was quite enormous.

The experience of the currently existing ACtHPR is very instructive in deciphering the resource requirements of the ACJHPR. In its 12 years of existence, the Human Rights Court has received 161 applications or casesFootnote 56. The total 2016 budget of the present Human Rights Court stood at USD 10,386.101.Footnote 57 Seventy-Six percent of the said budget, representing USD 7,934,615, is from the assessed contributions of member states of the African Union while 24 per cent of the budget in the amount of USD 2,451.486 came from ‘international partners’Footnote 58. This budget outlay needs to be considered within the context of the present characteristics of the ACtHPR as purely a part-time court that deals with Human Rights cases without the complexities inherent in criminal prosecutions of international crimes, or complex international civil claims between member states as could be envisaged in the International Criminal Law and General Affairs Sections of the ACJHPR, respectively.

The above overview of lessons from various judicial mechanisms provides a glimpse into what it may take to adequately resource the ACJHPR if it is to fulfil its mandate as a credible judicial arm of the African Union. It must be a court that should remain financially sustainable and fully financed by the resources of the African Union. How this could be done is the focus of the next section of this chapter, taking the current AU reform agenda into account.

6. Sustainably Financing the ACJHPR

As an institution that fuses three jurisdictional and legal competencies into one operation, the ACJHPR must be provided with adequate financial and human resources that are competitive, and sustainably so. The Court would complete the organic structure of the African Union as one of the most vital and permanent organs of the Union. It is not therefore, a body that is envisaged to fizzle out soon; in fact not at all. It thus becomes important that in the current mood of an AU reform as an organization that needs to take the financing of the Union much more seriously, the sustainable financing of the ACJHPR should occupy a central place in AU fiscal arrangements. Within this reform and under the funding mechanism envisaged in the AU 0.2 per cent levy on eligible imported goods into the continent, the AU must deliberately address the funding of its judicial arm in a forward looking manner. This it could do in three ways – through a regular budget, an endowment or a trust fund, and voluntary contributions from member states and willing partners. A regular budget would provide for the functioning of the Court based on predictable judicial and other activities from year to year from a predictable member states assessed contributions. A trust fund or an endowment fund would provide a reliable and sustainable source of funding for the future through proper investment channels. This would ensure that the court is placed in a position where it can be sure of its financial stability knowing the volatility of African economies that are dependent on commodities. This will enable the Court to continue to adequately function in circumstances of unforeseen financial drought. Voluntary contributions on the other hand, would assist the court to deal with ad hoc projects or activities, or enable it to bring on board short-term expertise that it may require to enhance its capacity from time to time.

It is envisaged that the new AU funding formula, if truly and fully implemented, would result in the Union generating more resources than it may immediately need or require. The situation where, in applying the 0.2 per cent import levy, member states would have the prerogative to keep for their domestic needs proceeds that are over and above their assessed contributionsFootnote 59, should be rethought. Those surpluses should be the source for the seed money for the endowment or trust fund for the Court.

The AU reform agenda provides an unmatched opportunity for the Union to really address how its institutions are funded. To ensure adequate financial accountability and to match the needs of those institutions with essential resources - particularly as it affects the ACJHPR, the AU must take a needed proactive step. As discussed earlier, it is essential to evaluate through a comprehensive study, the resource needs and requirements of the ACJHPR among other AU organs. This study should analyze the Malabo Protocol in terms of the structure of the Court and the resources for the optimal functioning of each of the structures – the sectional aspects of the Court – the General Affairs Section, the Human Rights Section and the International Criminal Law Section. In the same vein, the study should look at the organic structure – the Presidency, the Registry, the Office of the Prosecutor and the Defence Office. A clear assessment of resource needs that is specifically and holistically made, will provide a chance for getting it right in the sustainable financing of the ACJHPR.

It must not be business as usual where haphazard provisions are made for African Unions institutions without adequately thinking and really being alive to the needed resource requirements. For the ACJHPR, the significance of the situation cannot be overstressed – without the operationalization of the mechanism under the Malabo Protocol, a reputable and holistic judicial arm of the African Union will remain lacking. I would not want to imagine a United Nations without the International Court of Justice to articulate and interpret the norms established over the years by the United Nations systems when the need arises. Thus, an African Union without the operationalization of its judicial mechanism that is envisaged in its Constitutive Act for a continuously long period does not support the ideals that resulted in the transformation of the Organization of African Unity to the African Union.

7. Conclusion

Indeed, the adoption of the Malabo Protocol in 2014 was the ultimate streamlining of African Union’s judicial institutions that innovated the fusion of what could ordinarily stand as three separate courts – a Court of Justice of general jurisdiction, a Human Rights Court and an International Criminal Tribunal into a single judicial institution - the African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples’ Rights. The adoption of the Protocol was one thing; in fact, the simplest thing - all things considered; but operationalizing the Court that the Protocol created remains the most difficult. And the Court must be operationalized, as the AU cannot afford not to have a respectable judicial entity that should be relied on to resolve legal disputes within the African Union system. That is the significance of the ACJHPR. The need to operationalize the Court therefore must evoke serious thinking and concrete action on the financial sustainability of the institution, which has been the preoccupation of this chapter. Granted that there was no concerted effort to fully assess the financial implications of adopting the Malabo Protocol before it was adopted, this chapter sees it as a blessing in disguise, as it would have been nearly impossible to clearly articulate what would or would not be adopted by the AU Assembly at the time. Now that the Protocol has been adopted with clear organic structures and opened for ratification, it presents an opportunity for the AU to proactively take the next step to make the financial sustainability of the Court a cardinal point of emphasis and action. The chapter sees the current reform embarked upon by the AU on how its institutions are financed as the greatest singular opportunity in this regard. The strong resolve of the African Union to take its financial future into its own hands rather than overly relying on international partners to fund its programmes and institutions could not have come at a better time. The 2016 Kigali decision by the AU to impose 0.2 per cent import levy on eligible imports into the continent as way for member states to support the financing of AU institutions rather than from state treasury has the potential of making the AU financially sustainable. In this effort, the Court must therefore be prioritized, as the fused judicial institution would require enormous and sustainable resources to be able to fulfil its mandate. To get it right, the AU must take steps to embark on a post Malabo Protocol adoption study on the comprehensive resource needs of the Court so as to be able to place its financial requirements within the 0.2 per cent import levy financing mechanism just like the AU peace support operations. A concerted effort in this regard would ensure sustained financing for the Court through a regular budget from assessed contributions, an endowment or trust fund from surpluses as well as through voluntary contributions from partners to cater for ad hoc or short-term requirements of the Court.

1. Introduction

In the nearly twenty years since the Organization for African Unity became the African Union (AU),Footnote 1 it seems the AU has been in a state of perpetual reorganization, expansion, or modification.Footnote 2 The pace of change has sometimes been dizzying. Just in 2016, the AU committed to creating the African Minerals Development Centre, the African CDC, the African Science Research and Innovation Council, the Pan African Intellectual Property Organization, the Africa Sports Council, and the African Observatory in Science Technology and Innovation.Footnote 3

But many of these institutions exist only on paper.Footnote 4 For example, the AU formally adopted a constitutive document for all of the organizations listed in the paragraph above, but those documents have not been ratified by enough member states for them to enter into force.Footnote 5 The result is that the organizations exist in limbo waiting for the state support they need to come into being. Once their constitutive documents come into force, the AU will still have to give them the resources they need to succeed.

Even some older institutions still exist only on paper. For example, the Protocol on the African Investment Bank (adopted 2009), the Agreement for the Establishment of the African Risk Capacity Agency (adopted 2012) and the Protocol on the Establishment of the African Monetary Fund (adopted 2014) have not been ratified by enough states to enter into force.Footnote 6 In fact, of the three financial institutions that were specifically listed in the AU’s Constitutive Act in 2001 as being core components of the AU,Footnote 7 none of them exist yet.Footnote 8 The repeated failure of the AU to create functioning institutions has raised legitimate questions about whether the AU has the political will and capacity to follow-through on its many commitments.Footnote 9

These questions about the AU’s ability and desire to create functioning institutions are particularly relevant to its recent adoption of the Malabo Protocol.Footnote 10 The Malabo Protocol adds an international criminal law component to the jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights (ACJHR).Footnote 11 The addition of criminal jurisdiction to the ACJHR represents a significant increase in the court’s subject matter jurisdiction.Footnote 12 It also greatly increases the difficulty of the court’s work and necessitates a more complex organizational structure.Footnote 13 But can this new and improved ACJHR be successful? Will the AU have the political will to make it a reality? This chapter argues that the resources that the AU eventually devotes to the ACJHR will shed light on whether to be hopeful or doubtful about the court’s eventual success.

Building a functioning international criminal court is not easy. It requires substantial investigative and adjudicative resources.Footnote 14 If the AU does not devote sufficient resources to the ACJHR, it will not be successful.Footnote 15 Of course, having sufficient resources is not a guarantee of success, but if the AU devotes sufficient resources to the international criminal law component of the ACJHR that would be a very hopeful sign. First and foremost, it would indicate that the AU is committed to the ACJHR’s success. This is incredibly important as the ACJHR will not be successful if it does not have the financial and political support of the AU.Footnote 16

Thus, this chapter will explore the resources that will be needed to give the ACJHR a functioning international criminal law component. The International Criminal Court (ICC) will be used as a comparator. The ICC has publicly released information about the resource requirements of its own work and that will form the basis for predicting the eventual requirements of the ACJHR. While it is impossible to know exactly what resources are needed to carry out the Malabo Protocol, this chapter estimates that a fully operational ACJHR will need about 370 full-time personnel and a budget of approximately 50 million euros per year.Footnote 17 It is unlikely that the Malabo Protocol can be successful in the long-run with dramatically fewer resources than this. When the Malabo Protocol comes into force, the resources that the AU devotes to its implementation will give us insight into whether the expanded ACJHR can be successful.

2. The Development of the AU’s Judicial Bodies

In general, the evolution of the AU’s judicial bodies looks similar to the rest of the AU in that they have undergone rapid and extensive changes.Footnote 18 It also looks similar to the rest of the AU in that there has been a lack of follow-through. The first judicial body within the AU was the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights (the ACHPR). It was created to foster the “attainment of the objectives of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.”Footnote 19 The protocol establishing the ACHPR was opened for signature in June 1998 and entered into force in January 2008.Footnote 20

In addition, the AU’s Constitutive Act called for the establishment of a Court of JusticeFootnote 21 to serve as the “principal judicial organ” of the AU.Footnote 22 A protocol for the establishment of the African Court of Justice (ACJ) was adopted in July 2003 and entered into force in February 2009.Footnote 23 Almost as soon as the ACJ’s constitutive document had been adopted, the AU began talking about merging the ACHPR and the ACJ into a single court.Footnote 24 This was premised, at least in part, on the desire to reduce the cost of supporting two separate international courts.Footnote 25

In 2008, the AU issued the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights.Footnote 26 This protocol merges the two existing courts to create the ACJHR.Footnote 27 While the protocol to establish the ACJHR was adopted in 2008, it has never come into force. It requires fifteen ratifications to enter into force,Footnote 28 but has only been ratified by six states.Footnote 29

Yet even though the protocol establishing the ACJHR had not come into force, in 2009 the AU began discussing modifying the ACJHR to add an international criminal component.Footnote 30 This was driven largely by the indictment of African government officials by European states and the ICC.Footnote 31 The indictments were seen by the AU as inappropriate interference in African affairs.Footnote 32 By adding a criminal component to the ACJHR, the AU hoped to take control of the indictment and trial of African leaders.Footnote 33 These discussions culminated in 2014 in the adoption of the awkwardly-named Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human rights (hereafter called the “Malabo Protocol” because it was adopted in the city of Malabo in Equatorial Guinea).Footnote 34 Entry into force of the Malabo Protocol requires fifteen ratifications,Footnote 35 but, as of July 2017, it had not been ratified by a single country.Footnote 36

The story of the AU’s judicial bodies has been one of over-commitment and under-delivery. Almost ten years ago, the AU decided to merge the ACHPR and the ACJ to form a single court – the ACJHR. Progress toward that goal has been slow. But despite the fact that the ACJHR had not been established yet, the AU almost immediately began discussions to greatly expand the planned ACJHR by adding an international criminal law component.

At the rate that ratifications are currently being received, it could be another five or ten years before the protocol establishing the ACJHR comes into force.Footnote 37 At that point, it would require another fifteen ratifications of the Malabo Protocol before the amendments to add a criminal component to the ACJHR would take effect. As a result, it is not clear when or if the Malabo Protocol will come into effect, but it is unlikely to occur in the near future.Footnote 38

3. A New African Criminal Court?

Assuming that, at some point in the future, the Malabo Protocol comes into force, what would happen? The Protocol makes a number of significant changes to the ACJHR. First, it alters the structure of the ACJHR. As originally conceived, the ACJHR would have two sections: a Human Rights Section that would hear all cases relating to “human and/or peoples’ rights” and a General Affairs Section that would hear all other eligible cases.Footnote 39 The Malabo Protocol adds a new International Criminal Law Section,Footnote 40 which has jurisdiction over “all cases relating to the crimes specified” in the statute.Footnote 41

The addition of a criminal component to the ACJHR required other structural changes. For example, it necessitates the creation of an Office of the Prosecutor, and a Defence Office.Footnote 42 The Office of the Prosecutor will be responsible for “the investigation and prosecution” of crimesFootnote 43 while the Defence Office will be responsible for “protecting the rights of the defence [and] providing support and assistance to defence counsel.”Footnote 44

The Malabo Protocol also lays out the crimes the expanded ACJHR will have jurisdiction over. First, it will have jurisdiction over the core crimes under international law: genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.Footnote 45 It will also have jurisdiction over the crime of aggression.Footnote 46 The definitions of these four crimes appear to have been largely based on the definition of those crimes in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, although some changes have been made to expand them at the margins.Footnote 47 The ACJHR will also have jurisdiction over a number of crimes that are not within the jurisdiction of the ICC like piracy, terrorism, corruption, money laundering, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and the exploitation of natural resources.Footnote 48 These new crimes represent a potential source of problems as some of them do not have well-established definitions.Footnote 49

The overall result is a significant change in both structure and jurisdiction for the ACJHR. The resulting court will be unique in its attempt to incorporate the components of a regional international court, a human rights court, and an international criminal court into a single institution.Footnote 50 But will the new and expanded ACJHR be successful? This question will be explored below.

4. Between Hope and Doubt

The adoption of the Malabo Protocol has left many observers unsure whether to be hopeful or doubtful. On the one hand, there are reasons to be hopeful that the Malabo Protocol will make a positive impact.Footnote 51 First, having a regional court capable of investigating mass atrocities committed in Africa could help shrink the impunity gap on the continent.Footnote 52 Second, there may be some benefit in having cases arising out of African situations prosecuted in Africa.Footnote 53 Third, the Malabo Protocol will grant to the ACJHR the ability to prosecute some crimes that are outside the jurisdiction of the ICC, but are relevant in an African context.Footnote 54 Fourth, it says all the right things.Footnote 55 In the Preamble to the Malabo Protocol, the AU reiterated its commitment to “peace, security and stability on the continent” and to protecting human rights, the rule of law and good governance.Footnote 56 The members of the AU also stressed their “condemnation and rejection of impunity” and claimed that the changes in the Malabo Protocol will help “prevent[] serious and massive violations of human and peoples’ rights … and ensur[e] accountability for them wherever they occur.”Footnote 57 In short, the stated goals of the Malabo Protocol are very positive. They hold out hope of preventing atrocities and ensuring accountability. Thus, there are reasons to be hopeful.Footnote 58

On the other hand, there are also reasons to be doubtful.Footnote 59 The first concern is that the AU often appears to lack the political will and capacity to implement its vision for the organization.Footnote 60 This can be seen with the AU’s financial institutions. Despite being identified as key to the organization in the Constitutive Act, more than fifteen years later they still do not exist.Footnote 61 Something similar may happen to the Malabo Protocol.Footnote 62 Even if the Malabo Protocol does come into force, will the AU have the political will and resources to adequately fund the expanded ACJHR?Footnote 63

A second concern is whether the AU really intends the Malabo Protocol to be successful. The AU has a tense relationship with the ICC.Footnote 64 The ICC has brought charges against a number of African leaders and this has upset many AU member states.Footnote 65 The indictments of Presidents Al-Bashir of Sudan and Kenyatta of Kenya “galvanized [the] AU’s resolve to establish an African regional criminal court to basically serve as a substitute and operate parallel to the ICC.”Footnote 66 Thus, one way to view the Malabo Protocol is as a mechanism to prevent the ICC from exercising jurisdiction over senior government officials accused of committing crimes in Africa.Footnote 67 And indeed, there are some signs that the drafters of the Malabo Protocol hoped that the addition of criminal jurisdiction to the ACJHR would have this effect.Footnote 68

Creating a regional court whose work would prevent the ICC from exercising jurisdiction over violations of international criminal law committed in Africa would be fine if the AU intended the ACJHR to fairly and impartially prosecute violations committed by African leaders.Footnote 69 But there is also the possibility that the AU intends to use the Malabo Protocol to try and shield African leaders from accountability for human rights violations.Footnote 70 For example, the Malabo Protocol has a worrying provision on immunities.Footnote 71 It prevents the ACJHR from instituting or continuing cases against “any serving AU Head of State” or “other senior state officials.”Footnote 72 This has led to fears that the Protocol is designed, not to end impunity, but to shield African leaders from accountability.Footnote 73

Given that there are reasons to be both hopeful and doubtful about the Malabo Protocol, how should we view it?Footnote 74 The answer may lie in what happens if and when the Protocol enters into force. At that time, the AU will have the difficult task of turning the blueprint in the Malabo Protocol into a functioning international criminal court. It will have to staff the court and give it the resources and support it needs to be successful. This will not be an easy task.Footnote 75

One key indicator of the AU’s intentions toward the new and improved ACJHR will be the resources it devotes to the court. For it to live up to the hopeful vision of a successful regional court that reduces impunity and prevents atrocities, the ACJHR will have to have sufficient resources to carry out both its investigative and its adjudicative functions. On the other hand, if the court is mainly intended to insulate African leaders from accountability for human rights abuses, it will probably not be given the resources to conduct robust investigations and prosecutions. Thus, one way to evaluate the court will be to look at the resources it receives.

Of course, adequate resources are not a guarantee of success, but they are a prerequisite for it.Footnote 76 It will be extremely difficult for the court to be successful if it lacks the resources to carry out its functions. The rest of this chapter will examine what sort of resources one would expect the new ACJHR to need to be successful. Section 5 will look at the scope of the crimes usually investigated by international criminal courts, while Section 6 explores the investigative resources necessary to meaningfully investigate those crimes. Section 7 describes a typical trial at an international criminal court, while Section 8 explores the adjudicative resources necessary for such a trial. Section 9 presents an estimate of the staffing needs and costs of a fully operational ACJHR, while Section 10 compares those estimated costs to the AU’s early projections of the expense of the court. Finally, this chapter’s conclusions are presented in Section 11.

5. International Crimes

Most domestic crimes involve a single perpetrator, a single victim and a single crime site.Footnote 77 And very few domestic crimes involve the most serious offenses like rape and murder.Footnote 78 International crimes, at least the ones that are investigated and tried before international courts, look nothing like the typical domestic crime.

First, the kinds of crimes that are investigated and prosecuted at international tribunals are almost always perpetrated by large hierarchically organized groups working together.Footnote 79 Most often the perpetrators are military or paramilitary units of various sorts. In addition, the majority of international crimes take place as part of an armed conflict, with all the systematic violence that entails.Footnote 80 Even when there is not an armed conflict, there is still usually extensive politically-motivated violence aimed at civilians.Footnote 81 International crimes are also usually much larger in geographic and temporal scope than domestic investigations. The typical ICC investigation involved crimes committed at dozens of different crime sites over time periods that ranged from several months to several years.Footnote 82

International crimes also tend to be extremely serious and involve the widespread commission of rape, torture, murder, inhumane treatment and forcible displacement. For example, at the ICC, the average investigation covered the unlawful deaths of more than a thousand peopleFootnote 83 and the forcible displacement of huge numbers of civilians.Footnote 84 Systematic rape is a common feature of international crimes.Footnote 85 International crimes also tend to be marked by extreme cruelty, often against vulnerable groups like women, children, and the elderly.Footnote 86

As a result of these features, international crimes are vastly more complex than the average domestic crime. They involve a larger number of victims, more serious offenses, and take place over larger areas and longer time periods. They also take place during periods of systematic violence and tend to be carried out by large hierarchically organized groups. As a result, they require substantial resources to investigate.Footnote 87

6. Investigative Resources

Assuming the ACJHR undertakes criminal investigations that are similar in gravity to those undertaken by the ICC,Footnote 88 the ICC’s experience can be a guide to the investigative resources the ACJHR will need. The typical ICC investigation lasts about three years.Footnote 89 The investigative team varies in size over the course of the investigation, with fewer in the first few months and the last few months. But for at least two years, during what the ICC calls the “full investigation” phase, the investigative team is composed of about 35 personnel.Footnote 90

This team includes investigators and analysts, as well as a handful of lawyers, legal assistants and case managers.Footnote 91 It also includes specialists in forensics and digital evidence, and personnel to provide field support and security.Footnote 92 Over the course of three years, this team will screen hundreds of potential witnesses, interview about 170 of them, and collect thousands of pieces of physical and digital evidence.Footnote 93 It will then analyze this information so that the Prosecutor can decide whether to issue charges and, if so, who to charge, and what to charge them with.

It might be tempting to conclude that the ACJHR needs only one investigative team, but then it would only be able to undertake one investigation every three years. This would almost certainly not be enough. For example, the ICC anticipates opening nine new preliminary investigations and one new full investigation every year.Footnote 94 This is on top of the six active investigations it will have in any given year.Footnote 95

The ACJHR will probably need at least two investigative teams. Given that investigative teams only need to be at full strength during the middle of the investigation, it seems plausible that two teams could handle three investigations every three years (assuming that the start of the investigations was staggered). This would give the ACJHR the capacity to undertake approximately one new investigation every year. Thus, in any given year, the ACJHR would have two investigations ongoing, one that was being wrapped up, and have the ability to open one new one, if necessary. This is less investigative capacity than the ICC has, but would probably be sufficient, at least initially.

7. International Trials

Of course, completing an investigation is only the first step in a long process. The most visible part of the process comes next: the trial. International trials are complex undertakings that can take years to complete. For example, at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the average trial took 176 court days to complete.Footnote 96 During the trial, an average of 120 witnesses testified and more than 2,000 exhibits were entered into evidence.Footnote 97 While some have criticized international trials as too long and too slow,Footnote 98 it appears that this complexity is necessary.Footnote 99

International trials feature a number of factors that increase their complexity relative to the average domestic trial. First of all, they often involve multiple defendants accused of acting together, which increases trial complexity.Footnote 100 International trials also tend to involve a large number of charges against each accused, which also increases complexity.Footnote 101 Finally, another hallmark of international trials is that the accused tend to be senior military or political leaders, which also increases the length of the resulting trial.Footnote 102

This latter point is particularly important as it generates significant additional trial complexity.Footnote 103 This complexity appears to be a result of the difficulty of attributing responsibility for mass atrocities to senior leaders who are both geographically and organizationally distant from the crimes.Footnote 104 Attributing responsibility requires establishing evidence that links the charged persons to the crimes carried out by the direct perpetrators. International criminal lawyers refer to this as the “linking evidence” and it is critical to demonstrating the guilt of the accused. Establishing this link, however, is complex and time-consuming. This complexity is necessary, however, if courts are serious about ending impunity for those most responsible for mass atrocities.Footnote 105

One result of the length and complexity of international trials is that courts need significant resources to carry them out. This is true both in the Office of the Prosecutor and Chambers. If adjudicative resources are insufficient, then trials may be delayed. In a worst case scenario, prosecutions may fail for lack of evidence or accused may have to be released because of the delay in bringing them to trial.

8. Adjudicative Resources

So, what adjudicative resources does the new ACJHR need to conduct successful trials? Again, the experience of the ICC will be used as a guide. The Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC estimates that the average trial takes about five and a half years from the completion of the investigation until the conclusion of the appeal. This includes half a year of pre-trial preparation, three years for the actual trial, and two years for the appeal.Footnote 106 The core trial team is composed of about 15 personnel. The majority of these personnel come from the prosecution division and includes lawyers, legal assistants, and case managers.Footnote 107 They are supported by a small number of investigators who provide support for cross-examination of defense witnesses and investigation of defense theories.Footnote 108 This team has to be in place for about three and a half years to complete a single trial. Assuming that the ACJHR closes one investigation each yearFootnote 109 and that (like the ICC) the majority of new investigations result in immediate trial proceedings,Footnote 110 then there will be approximately one new trial beginning each year. Given that each trial lasts three years, the ACJHR would need at least three trial teams to staff those trials.

The Office of the Prosecutor at the ACJHR will also need a group of lawyers and support staff dedicated to appeals. If one trial finishes each year, and appeals last two years, then on average there will be at least two final appeals going on at any time. To handle two final appeals plus a small number of interlocutory appeals arising out of ongoing cases, the ICC requires seven personnel.Footnote 111 It seems likely that the ACJHR would need an appeals section of about the same size.

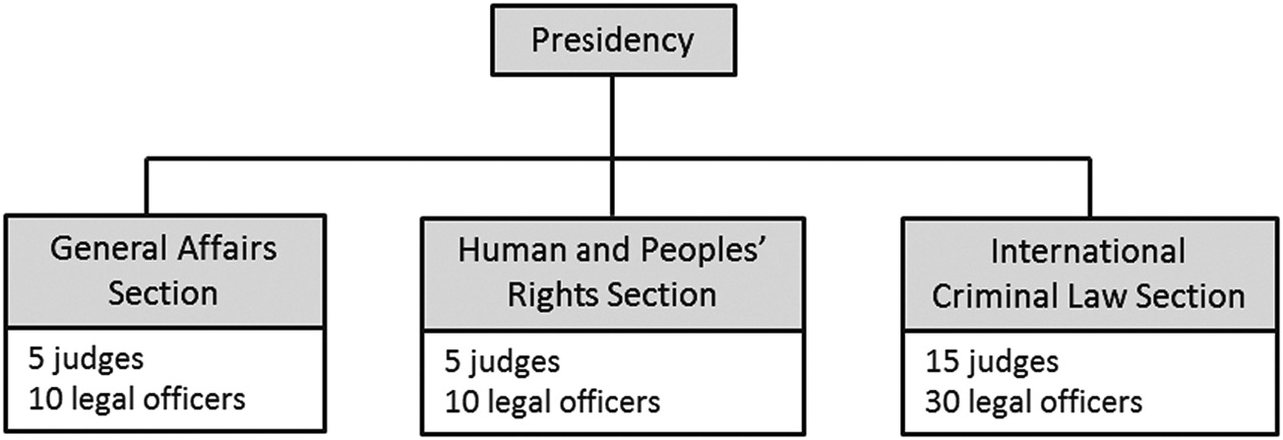

In addition to the required personnel within the Office of the Prosecutor, the ACJHR will also require the necessary staff within Chambers. The new International Criminal Law Section will have within it three Chambers: a Pre-Trial Chamber, a Trial Chamber and an Appellate Chamber.Footnote 112 But, it appears the International Criminal Law Section as a whole will have only six judges.Footnote 113 This is almost certainly inadequate.Footnote 114

The Pre-Trial Chamber requires one judge, the Trial Chamber requires three judges, and the Appellate Chamber requires five judges. Even if only one trial was going on at a time six judges would be inadequate because it would be impossible to staff all three chambers unless judges sat on multiple chambers for the same case. This would be problematic as it would require a judge who sat at an earlier stage of a case (say as a trial judge) to then adjudicate a later stage (say as an appellate judge). Having the same judge sit at different stages of the same case undermines the defendants’ fair trial rights.Footnote 115 So, for this reason alone, the ACJHR would need at least nine judges so that no judge would have to sit at different stages of the same case.

But even nine judges would probably not be enough. Assuming that one new trial begins each year and that each trial lasts about three years,Footnote 116 the ACJHR will need to constitute three Trial Chambers. This would require nine judges on its own. Even if the existing Appellate Chamber could handle all of the appeals and a single Pre-Trial Chamber judge could handle all pre-trial matters that would still mean that the ACJHR would need fifteen judges just in the International Criminal Law Section.Footnote 117

In addition to 15 judges, the International Criminal Law Section would also need the necessary legal personnel to support those judges. The ICC estimates that it needs five full-time legal personnel assigned to Chambers per trial.Footnote 118 If the ACJHR has similar needs, it would require fifteen legal personnel to staff the three Trial Chambers. Again, following the ICC’s model, the Appellate Chamber would need a staff of ten legal officersFootnote 119 while the Pre-Trial Chamber would require only two personnel (assuming that only a single judge is assigned to it).Footnote 120

Finally, the Chambers will need something like the ICC’s Court Management Section, which maintains the official records of the proceedings, distributes orders and decisions and maintains the Court’s calendar, including the scheduling of all hearings.Footnote 121 The ICC employs 33 people in the Court Management SectionFootnote 122 to support the work of 18 judges.Footnote 123 This chapter argues that the ACJHR will eventually need fifteen judges in the International Criminal Law Section. This is on top of the judges in the Human and Peoples’ Rights Section and the General Affairs Section. Accordingly, it seems likely that the ACJHR will need a similarly sized court management section to support the work of those judges.

9. Staffing a New International Tribunal

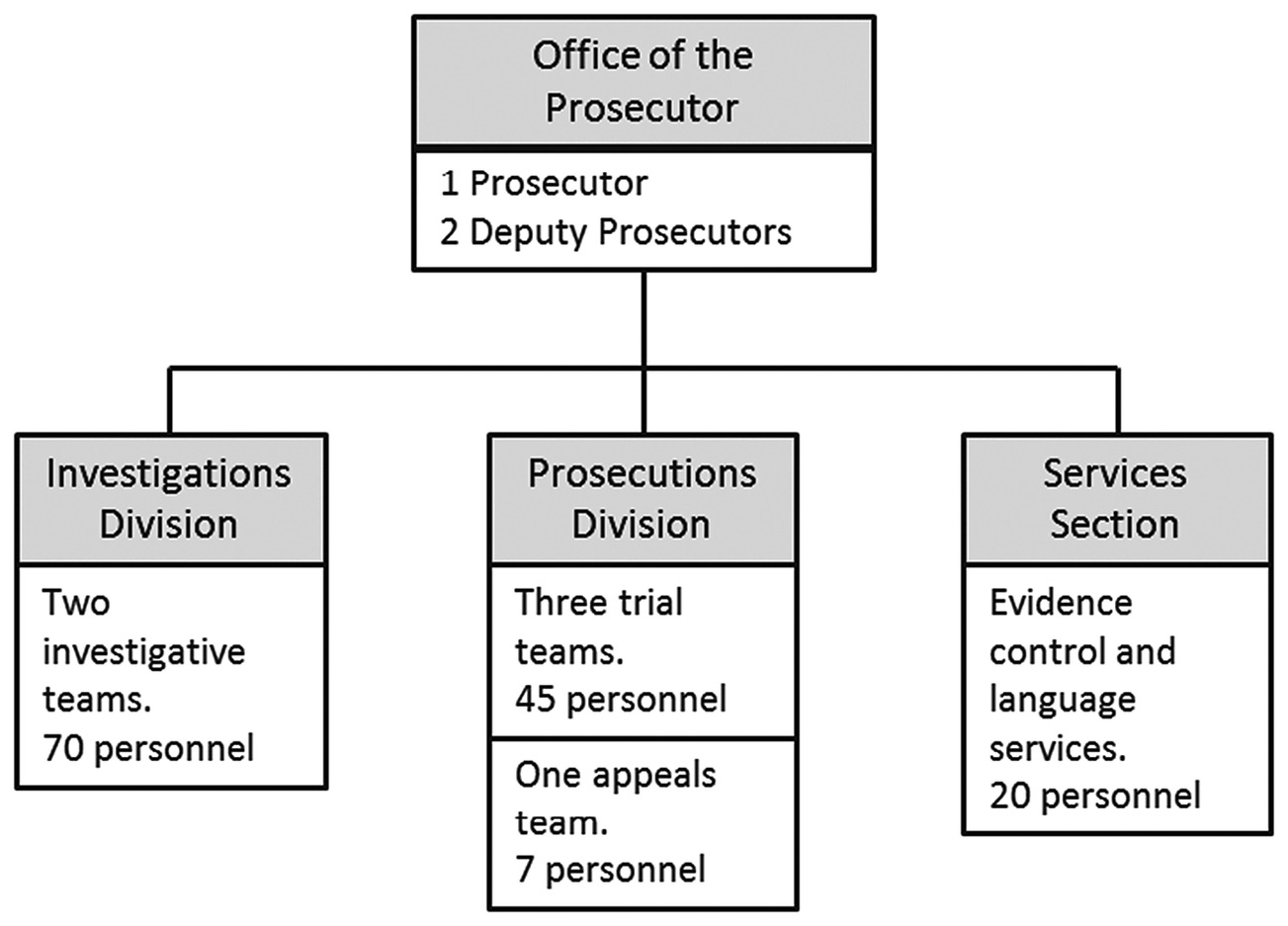

As the previous sections have demonstrated, building a functioning international criminal court is far from simple. First, it will need to have the staff to carry out its investigative functions. Within the new ACJHR’s Office of the Prosecutor this will probably mean two investigative teams of about 35 personnel each. This will include a mix of investigators, analysts, forensics experts, and legal personnel.

The court will also have to have sufficient personnel to carry out its adjudicative functions. This will almost certainly mean in increase in the number of judges assigned to the International Criminal Law Section to 15 or so judges. They would need to be supported by at least twice that number of legal officers. In addition the prosecutions division within the Office of the Prosecutor will need three trial teams of about 15 personnel each plus an appeals team of about 7 or 8 personnel. Finally, there must be some organ like the ICC’s Court Management Section to create the official record and handle all of the scheduling issues.

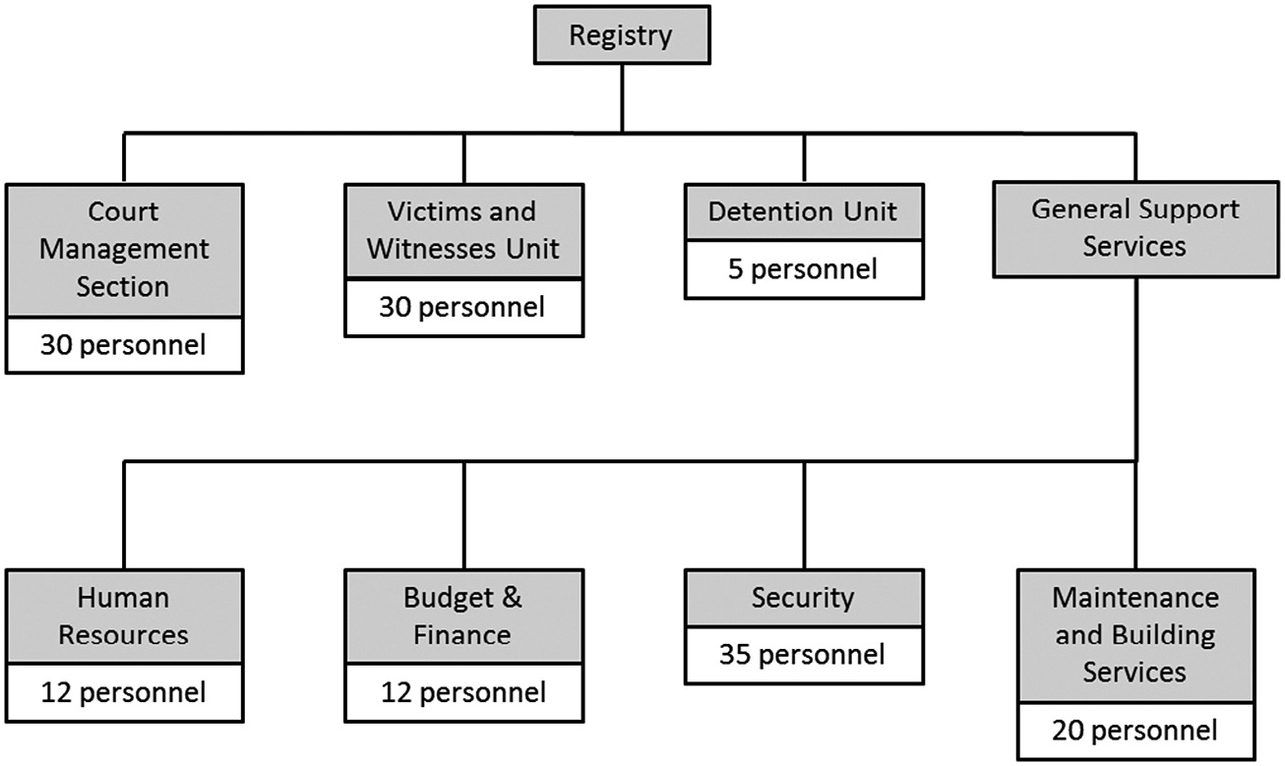

And these are just the core personnel tasked with carrying out the investigations and trials. In practice, international courts need additional personnel to support the core tasks. For example, the OTP at the ICC contains a Services Section that contains the Information and Evidence Unit and the Language Services Unit.Footnote 124 These are important units that help control and preserve evidence and provide the interpretation and translation services that are almost certainly going to be needed by the investigative and prosecutorial teams.Footnote 125 The Services Section at the ICC is about one-third the size of the Investigation Division and half the size of the Prosecutions Division.Footnote 126

In addition, the Amended Statute of the new ACJHR specifically says that the Registrar must create a Victims and Witnesses Unit to provide “protective measure and security arrangements, counselling and other appropriate assistance” for victims and witnesses.Footnote 127 It also requires the Registrar to set up a Detention Management Unit to “manage the conditions of detention of suspects and accused persons.”Footnote 128 Finally, the Amended Statute provides for an independent Defence Office that will be responsible for “protecting the rights of the defense, providing support and assistance to defence counsel … .”Footnote 129 These units will have to be staffed. At the ICC, the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence has similar functions to the ACJHR’s Defence Office and has five personnel.Footnote 130 Similarly, the ICC’s Detention Section has five staff members.Footnote 131 The ICC office most similar to the ACJHR’s Victims and Witnesses Unit is the Victims and Witnesses Section.Footnote 132 The ICC employs 63 people in this task.Footnote 133

It is also highly likely that the new ACJHR will need other more general support services. At the ICC, these are located within the Registry. It is likely the same would be true at the ACJHR.Footnote 134 At the ICC, the Registry includes functions like a Human Resources Section,Footnote 135 a Budget Section,Footnote 136 a Finance Section,Footnote 137 a Security and Safety SectionFootnote 138 and a General Services Section.Footnote 139 While the ACJHR would not necessarily need to be structured in the exact same way, it will need the same services. It will need to have staff that provide security, clean and maintain the buildings, and pay the bills. Even if we assume that the new ACJHR would only need about half as many personnel in these functions as the ICC, it would still need something like 80 people in these support positions.

The following organizational charts make an educated guess about what resources the new and expanded ACJHR will need to successfully investigate and prosecute international crimes once it is fully operational.Footnote 140 These are not meant to be exact predictions. For example, it may be possible to make the investigations teams slightly smaller. Or it might be possible to have fewer legal officers in Chambers and fewer personnel in the Victims and Witnesses Unit. Perhaps the court can get by with fewer personnel in support roles. Of course, cutting corners on resources can be counter-productive, as the ICC has discovered.Footnote 141

These figures suggest a court with about 145 personnel in the Office of the Prosecutor. The majority of the personnel in the OTP would be working on investigations. The Presidency would be composed of 25 judges and 50 legal officers. Their primary function would be to hear the trials and appeals. Finally, the Registry would require about 145 personnel to provide the needed support services to the court. In addition, the Defence Office will have five or six staff members. This assumes that there will be no permanent interpretation/translation office in the Registry and that interpretation and translation services will be provided under service contracts rather than through the hiring of full-time personnel.Footnote 142

Overall, the expanded ACJHR would have a staff of about 370 personnel. This would make it roughly one-third the size of the ICC, which currently has about 1,100 personnel.Footnote 143 This implies an expected cost of about 48 million euros per year for the new ACJHR.Footnote 144 This is many times the current budget of the AU’s judicial bodies.Footnote 145

10. Early AU Estimates of the ACJHR’s Needs

The AU’s member states have been concerned about the consequences of expanding the ACJHR’s jurisdiction.Footnote 146 So, for example, at a meeting of Ministers of Justice in 2012, various delegations asked about the “financial and budgetary implications” of expanding the jurisdiction of the court.Footnote 147 This concern has resulted in a small number of documents that discuss the expected resource requirements of the ACJHR. Unfortunately, these documents are from 2012, so it is unclear whether they still represent the position of the AU.Footnote 148 But given that they are the only financial projections from the AU that are available, this chapter will discuss them.

The reports discuss whether there are existing courts that could be used as examples of the resources the ACJHR will need. For example, the report of the meeting of Ministers of Justice notes that the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) cost $16 million per year in 2011 and employed slightly more than 100 personnel.Footnote 149 It also notes that the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) cost $130 million per year in 2010 and employed 800 staff.Footnote 150 But it takes no position on whether either of them is a good model for the ACJHR. Another report suggests that the trial of the former President of Chad, Hissène Habré, in Senegal, which reportedly cost about 7 million euros over three years, represents the “most appropriate” comparison.Footnote 151

All of these comparisons are flawed. The ACJHR probably does not need to be as big as the ICTR at its height.Footnote 152 Nor is the trial of a single individual – Hissène Habré – likely to represent the experience of the ACJHR, which may need to open one new investigation and begin one new trial every year.Footnote 153 The SCSL in 2011 is not a particularly good comparison either. By 2011, the SCSL had almost completed its mandate. The only significant legal activity that year was the trial of Charles Taylor.Footnote 154 There were no new investigationsFootnote 155 and minimal activity by the Appeals Chamber.Footnote 156 The expanded ACJHR will have to undertake complex investigations and be able to deal with more than one trial and appeal at a time. The most obvious contemporaneous comparator is the ICC. The omission of references to the ICC in the AU’s documents may stem from its difficult relationship with the ICC.Footnote 157

If the SCSL is to be used as a comparator, however, then the SCSL in 2007 is a better choice. In that year, the SCSL was engaged in the CDF trial, the RUF trial, and the AFRC trial.Footnote 158 There was also substantial activity in the Appeals Chamber.Footnote 159 The Office of the Prosecutor, in addition to participating in the ongoing trials, was also engaged in the investigation of the Charles Taylor case.Footnote 160 This is more like what a fully operational ACJHR can expect. But it is worth noting that the SCSL cost $36 million in 2007 and employed more than 400 people.Footnote 161 This is similar to the projections in this chapter.Footnote 162

Besides looking for appropriate comparators, one of the AU’s reports also contains a proposed staffing table for the expanded ACJHR.Footnote 163 A summary of that information is contained below in Table 38.1.Footnote 164 One noticeable (and presumably deliberate) omission is any entry for the judges and their salaries. But beyond that, there are some staffing assumptions that are simply unrealistic.

| Office | Components | No. of Staff | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registrar | |||

| Office of the Registrar | 18 | $420,791 | |

| Information and Communication | 3 | $89,403 | |

| Languages Unit | 41 | $1,127,451 | |

| Sub-Total | 62 | $1,637,645 | |

| Legal Division | |||

| Office of the Division | 1 | $45,551 | |

| Legal Unit | 16 | $511,568 | |

| Library, Archives, and Documentation | 14 | $266,692 | |

| Sub-Total | 31 | $823,811 | |

| Finance, Admin. and HR | |||

| Office of the Division | 2 | $91,102 | |

| Finance, Budgeting, and Accounting | 6 | $131,838 | |

| HR and Administration | 8 | $169,668 | |

| Procurement, Travel, and Transport | 11 | $144,809 | |

| IT Services | 10 | $254,860 | |

| Security and Safety | 30 | $326,022 | |

| Protocol Unit | 9 | $168,546 | |

| Sub-Total | 76 | $1,286,845 | |

| Office of the Prosecutor | |||

| Office of the Prosecutor | 6 | $189,696 | |

| Prosecution Division | 5 | $161,511 | |

| Investigation Division | 1 | $38,489 | |

| Sub-Total | 12 | $389,696 | |

| Total | 181 | $4,137,997 |