The forests of Taunus were flooded with a dark human tide … .

After nightfall, fires flared at regular intervals along the hillside. Each time a new light pierced the blackness, thousands of loud-speakers roared: ‘The goal is in sight.’ Many were dressed in ‘festive shepherds’ garb’ and wore ornamental badges. There were also many uniforms similar to those of the former Wehrmacht, except that the swastika had been replaced by a shepherd’s staff with a ribbon, the ends of which were gripped in the beaks of doves.

Ten minutes before midnight, Friedolin appeared on a clearance where a pile of wood had been prepared. He was accompanied by the Shepherds, five field marshal generals, two grand admirals, and one air general … .

In the clearing a few hundred guests of honor – Germans as well as foreigners – were waiting … .

A field marshal general held a silver microphone. Thousands of loudspeakers transmitted Friedolin’s shrill cry: ‘The Fourth and Eternal Reich is in sight!’

Then the pile of wood in the clearing flared up. The human mass roared; power gathered like a thunderhead.1

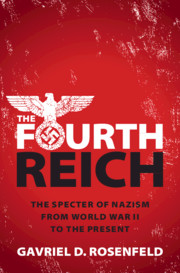

As World War II was winding down in the fall of 1944, the American-based Austrian writer, Erwin Lessner, published a dystopian novel, Phantom Victory, that gave voice to a burgeoning fear among many people in the English-speaking world. The novel’s plot, set in the years 1945–60, portrayed a humble, but charismatic shepherd named Friedolin replacing Adolf Hitler as Germany’s new Führer and leading the nation in a renewed bid for world power. Phantom Victory reflected growing concerns that the dangers of the recent past might return in the near future. At the time of the novel’s publication, Allied forces were rapidly driving the Wehrmacht back into German territory. The novel’s conclusion, however, implied that military might would not be enough to guarantee a final triumph. Unless the Allies remained vigilant about preventing the revival of Nazi ideas, the impending defeat of the Third Reich might prove fleeting – a “phantom victory” – and be followed by the rise of an even deadlier Fourth Reich.

Lessner’s narrative was one of the first to articulate a fear that has hovered over the entire postwar era. Ever since the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945, a specter has haunted western life – the specter of resurgent Nazism. Throughout Europe and North America, anxieties have persisted about unrepentant Nazis returning to power and establishing a Fourth Reich. These anxieties have been expressed not only in novels like Lessner’s, but in political jeremiads, journalistic exposés, mainstream films, prime-time television shows, and popular comic books. They have imagined a range of threats – political coups, terrorist attacks, and military invasions – emanating from a variety of settings, including Germany, Latin America, and the United States. Fears of a Fourth Reich have fluctuated over time, swelling in certain eras and ebbing in others. But the nightmare they have envisioned has never come to pass. Thus far, the prospect of a revived Reich has remained confined to the imagination.

It may initially seem pointless to examine the history of the Fourth Reich. After all, history is commonly understood as the documentation and interpretation of events that actually happened. Yet, as Hugh Trevor-Roper eloquently observed more than a generation ago, “history is not merely what happened: it is what happened in the context of what might have happened.”2 It is a fact that no Fourth Reich came into being in the years following World War II. But could it have? Can reflecting on such a counterfactual question teach us anything about real history? This book suggests that the answer is yes.

From today’s perspective, postwar fears of a Fourth Reich appear grossly exaggerated. Germany did not descend into dictatorship after 1945. Instead, the country became a stable democracy. It is entirely appropriate, therefore, to view postwar German history as a success story. Yet doing so runs the risk of portraying the country’s democratization as more or less inevitable. It implies that a Fourth Reich was destined to remain an unrealized nightmare. Whether or not this claim is true is hard to say. Until now, there has been little serious research on the subject of the Fourth Reich. As a result, historians have remained ignorant about its complex postwar history. They have generally overlooked the fact that in every phase of the Federal Republic’s existence, fears persisted throughout the western world that a new Reich was on the horizon. They have neglected to examine the reasons for these fears. And they have failed to ask – let alone answer – the question of whether these fears had any basis in reality. This latter omission is particularly problematic, for there were more than a few episodes after 1945 when Germany faced serious threats from Nazi groups seeking to return to power. All of these efforts ultimately failed. But it is worth investigating whether they might have succeeded. By revisiting these episodes and imagining scenarios in which they might have unfolded differently, we can better gauge the validity of postwar anxieties.

By examining the history of what might have happened, moreover, we can better understand the memory of what actually did. The evolution of the Fourth Reich as an idea in postwar western intellectual and cultural life reflects how people have remembered the twelve-year history of the Third Reich. The idea’s evolution, however, does not merely show how people have passively remembered the events of the past. It shows how they have actively employed those memories to shape the future. The fear of a Nazi return to power has long driven public efforts to prevent such a possibility from actually transpiring. The fear has galvanized people to prevent a Nazi revival not only in Germany, but anywhere in the world. Over the course of the postwar era, the Fourth Reich has become universalized into a global signifier of resurgent Nazism and fascism. In the process, the idea has functioned like a self-fulfilling prophecy in reverse. By inspiring popular vigilance, its existence in the realm of ideas has prevented its realization in reality. In order to understand this paradoxical phenomenon, it is necessary to examine the origins and evolution of the Fourth Reich in western consciousness. In so doing, we can see how postwar history has been shaped by a specter.

Historicizing the Fourth Reich

There has been little systematic research thus far on the Fourth Reich. As a result, most people have been exposed to the topic through sensationalistic stories in the mass media. For decades, but especially since the turn of the millennium, European newspapers in countries from Spain to Russia have warned of a Fourth Reich – none more frequently than British tabloids, which have regularly published stories with excitable headlines, such as “MI5 Files: Nazis Planned ‘Fourth Reich’ in Post-War Europe” and “Dawn of the Fourth Reich: Why Money is Fuelling New European Fears of a Dominant Germany.”3 Similar stories have appeared in the American press, particularly since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, with one recent journalist dramatically declaring that the efforts of left-wing “antifa” groups to combat the “alt-right” were part of a larger campaign to “guard … against a Fourth Reich.”4 Further contributing to this sensationalizing trend have been non-academic studies that have linked the idea of a Fourth Reich to various global conspiracies. Books such as Jim Marrs’ The Rise of the Fourth Reich: The Secret Societies That Threaten to Take Over America (2008) and Glen Yeadon’s The Nazi Hydra in America: Suppressed History of a Century – Wall Street and the Rise of the Fourth Reich (2008) have made outlandish assertions that have done little to shore up the topic’s claim to academic credibility.5

The proliferation of such sensationalistic texts helps explain why historians have shied away from studying the Fourth Reich. This is not to say that they have entirely avoided it. In fact, scholars and other writers have produced monographs, journal articles, and opinion pieces with eye-catching titles prominently featuring the phrase “The Fourth Reich.”6 Yet, after grabbing readers’ attention, these works have generally failed to explain the idea in any significant depth and show how it was perceived, used, and exploited. Similar shortcomings have marked academic studies that have mentioned, but never sufficiently defined, the idea of the Fourth Reich. In her book, A History of Germany 1918–2008, for example, Mary Fulbrook asserted that, after the end of World War II, “many [Germans] saw the occupation by the Allies as a ‘Fourth Reich,’ no better than the Third.”7 Similarly, in his study, The Nazi Legacy, Magnus Linklater declared that, after 1945, “the German people, totally exhausted by war and politics, thought only of survival: a kilo of potatoes … mattered more than dreams of a Fourth Reich.”8 These two passages employ very different understandings of the Fourth Reich; yet because neither goes on to interpret the concept in any further depth, its significance remains unclear.9 The failure of scholars to advance our understanding of the Fourth Reich has been compounded by historians who have dismissed the concept altogether. In his book, The Third Reich at War, Richard Evans flatly declared that “history does not repeat itself. There will be no Fourth Reich.”10 In The Nature of Fascism, Roger Griffin dismissed “fears … [of] a Fourth Reich in Germany” as “hysterical.”11 And in The Spirit of the Berlin Republic, Dieter Dettke concluded that “it is inconceivable that the Berlin Republic will ever be a Fourth German Reich.”12 These curt responses are understandable given the sensationalistic invocations of the concept. But by dismissing its seriousness, they discourage efforts to probe its deeper history.

In light of how the Fourth Reich has been under-theorized and under-documented, it is high time for it to be historicized. Doing so requires uncovering the term’s origins and tracing its evolution in western intellectual, political, and cultural discourse. This task entails examining the ways that the Fourth Reich has been imagined by intellectuals, politicians, journalists, novelists, and filmmakers. It necessitates explaining how the idea’s evolution has reflected broader political and cultural forces. Finally, it involves understanding how the concept relates to broader questions of history and memory.

The Fourth Reich as Symbol

The first step towards historicizing the Fourth Reich involves recognizing its semantic ambiguity.13 At the most basic level, the Fourth Reich is a linguistic symbol – that is to say, a word or a phrase that employs description or suggestion to communicate some kind of meaning in relation to some external entity.14 The Fourth Reich is also a metaphor, a phrase that means one thing literally, but is used figuratively to represent something else. Most importantly, the Fourth Reich is a slogan. It is a highly rhetorical signifier that employs an attention-grabbing phrase in order to inform and persuade. The phrase can be aspirational or oppositional, positive or negative, but it reformulates complex social and political ideas into more simplified terms. In so doing, a slogan forges solidarity among people of varying political views by giving them a common idea to rally around. At the same time, a slogan can also foster social polarization by sparking opposition from groups whose members believe differently.15

From its inception up to the present day, the Fourth Reich has displayed nearly all of these characteristics. As an omnipresent symbol, metaphor, and slogan in postwar western life, it has long been defined by ambiguity. This is especially true in a temporal sense. As a term, the Fourth Reich has mostly been used to refer to the future – to a reality yet to come. But it has also been used to refer to the present – to a reality that (allegedly) has already come to be. The Fourth Reich is also ambiguous in a spatial sense. It has mostly been employed to refer to a future or present-day Germany, but it has been applied to other countries as well. In both realms – temporal and spatial – the Fourth Reich has communicated denotative as well as connotative meaning. It has been used literally, symbolically, and metaphorically to describe a current or future reality – whether democratic or totalitarian – in multiple locales. It has also been employed rhetorically to evoke competing views about that reality. These views have been both positive and negative; they have expressed fantasies as well as fears. In both cases, the idea of the Fourth Reich has galvanized support as well as opposition. In doing so, it has won the allegiance, and aroused the enmity, of millions of people in Germany and around the world. For all of these reasons, tracing the history of the Fourth Reich provides a deeper understanding of one of the postwar era’s more influential, albeit under-examined, ideas.

The Fourth Reich and Postwar German History

Historicizing the Fourth Reich opens up new perspectives on postwar German history. It is especially useful in helping us rethink the Federal Republic’s main “master narrative.” Scholars have traditionally portrayed Germany’s postwar development as a “success story” (Erfolgsgeschichte).16 They have attributed this success to a range of factors, including the reconstructionist thrust of the western Allies’ occupation policy, the prosperity generated by the country’s economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder), the stability afforded by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s pursuit of western integration (Westbindung), and the salutary effects of the country’s overall “modernization.” Politicians have long embraced the belief that this combination of factors made Germany a model to emulate – most notably, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, who, in 1976, coined the famous campaign phrase, “Modell Deutschland.”17 The “success story” narrative has also been institutionalized in museums, such as the Haus der Geschichte in Bonn, whose permanent exhibit presents an unmistakable story of progress from dictatorship to democracy.18 Despite this consensus, however, some issues remain debated. Scholars have disagreed about when postwar Germany became stabilized once and for all, with conservatives pointing to the mid 1950s and liberals dating it to the country’s liberal “second founding” in the 1960s and 1970s.19 Most agree, however, that with German reunification in the years 1989–90, the country’s success was clinched. By this point, Germany’s deviant historical path of development (or Sonderweg) finally came to an end.20

There is nothing inherently false with the “success story” narrative, but it has sometimes lent the Federal Republic’s success an aura of inevitability. Few historians have made this claim explicitly, but the tendency of some to portray the country’s democratization as proceeding in uninterrupted fashion makes the thesis vulnerable to certain interpretive pitfalls.21 One potential problem is “hindsight bias.” This common fallacy uses our knowledge about the final outcome of a historical event to portray it as overdetermined and essentially inevitable; in so doing, it reproduces the familiar problems associated with teleological or “whiggish” views of history.22 To cite one example: hindsight bias clearly informed a speech delivered by Federal President Horst Köhler in 2005, in which he praised the “success” of Germany’s postwar “democratic order,” concluding that “hindsight shows clearly that all [the] … decisions [that were made] were right.”23 Hindsight bias is closely related to the equally problematic narrative strategy of “backshadowing,” in which historical events, decisions, and phenomena are portrayed – and, more importantly, judged – as smoothly progressing to inevitable outcomes that “should” have been visible to contemporaries.24 Both of these interpretive shortcomings are related to the larger problem of “presentism.”25 The tendency to view the past exclusively from the vantage point of the present brings with it inevitable distortions of historical perspective. Besides promoting deterministic thinking, it ignores the existence of alternate paths of development and neglects to imagine how history might have been different.

In recent years, historians have called attention to the presentist features of postwar Germany’s master narrative. They have done so, fittingly enough, because of important changes in present-day German life. The “success story” narrative peaked in the years leading up to, and immediately following, German unification in 1990 – a time when many Germans viewed their country’s postwar development with unadulterated pride.26 Since the turn of the millennium, however, new concerns about contemporary problems – economic stagnation, social decline, and cultural anomie – have led scholars to critically rethink the “success story” narrative. Some have called for questioning the postwar era’s underlying “myths” and “dark sides.”27 Others have bemoaned the fact that Germany’s success is taken for granted and have called for challenging its aura of inevitability.28 Still others have criticized the paradigms of “westernization,” “modernization,” and “democratization” for being overly “whiggish.”29 From these critics’ perspective, none of Germany’s postwar achievements had to happen. “Other paths of development,” one observer has declared, “were … conceivable.”30

Yet while scholars have admitted there were alternative paths for postwar Germany’s development, few have explored how they might have actually unfolded. Few have speculated at length about what specific alternatives existed. Fewer still have wondered what their consequences would have been. Would alternative decisions have made things better? Or would they have made them worse?

Counterfactual History

To answer these speculative questions, it helps to employ counterfactual reasoning. In recent years, scholars in the humanities and social sciences have increasingly explored “what if” questions in their academic work. They have produced extended, “long form counterfactuals” devoted to speculating on such varied subjects as Darwin’s theory of evolution, World War I, and the Holocaust.31 They have interjected briefer, “medium form counterfactuals” into narratives on the rise of the west, the Enlightenment, and the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin.32 And they have produced fleeting, “short form counterfactuals” on a myriad other topics. In so doing, scholars have challenged the view that history pertains only to events that actually happened and have instead explored events that never happened. They have produced “fantasy scenarios” to show how events could have turned out better; they have imagined “nightmare scenarios” to show how events might have been worse; and they have entertained “stasis scenarios” to show how history ultimately had to happen as it did. In the process, they have embraced diverse rhetorical strategies to convince readers of their scenarios’ plausibility. They have employed causal, emotive, temporal, spatial, existential, and manneristic counterfactuals in order to appeal to readers’ emotions and reason.33

This recent scholarship makes clear that counterfactual reasoning is indispensable for understanding historical causality. Counterfactuals are embedded in all causal claims: when we declare that “x caused y,” for instance, we implicitly affirm that “y would not have occurred in the absence of x.”34 Counterfactuals can also help us differentiate between different levels of causality: between immediate, intermediate, and distant causes; between exceptional and general causes; and between necessary and sufficient causes.35 To be sure, it can be difficult to distinguish between the relative importance of such causes, but as Max Weber argued over a century ago, we can determine a single factor’s significance in causing a historical event by imaginatively eliminating (or altering) the former and speculating on how doing so would affect the latter.36 By revealing the relationship of events that did and did not happen, counterfactuals enable us to sort out the relative influence of contingency and determinism in historical events. Counterfactuals enable us to rethink teleological views of history – in particular, the distorting effects of hindsight bias and backshadowing – and reveal the alternative paths that history might have followed.37 Ultimately, counterfactual history provides historians with a new and important arrow in their methodological quiver as they pursue the elusive ideal of historical truth. Skeptics may question whether exploring events that never happened can bring us closer to this ideal. But as John Stuart Mill pointed out long ago, we acquire a “clearer perception and livelier impression of truth” once it is brought into “collision with error.”38 Similarly, we can better understand what actually happened in the past by examining it alongside what might have happened.

Pursuing this unconventional path of analysis is not only profitable, but timely. We are living in an era that is inclined to counterfactual thinking. Speculative thought thrives in periods of rapid change. While orthodox views of the past are easy to maintain in periods of stability, revisionist challenges gain support in eras of upheaval. It is easy to take history’s course for granted – to perceive it as deterministically preordained – when the existing order is not threatened by any looming alternatives; by contrast, when the status quo begins to break down in the face of new forces, alternative paths of development become increasingly clear.39 The current interest in counterfactuals reflects this same trend. Although “what ifs?” were hardly unknown during the cold war, they proliferated after its conclusion. The end of the comparatively stable, bipolar world brought about a new era of uncertainty marked by unexpected crises. They began in the 1990s with the Yugoslav Civil War, intensified after the turn of the millennium with the global “war on terror,” and reached a climax after 2008, with the eruption of the Great Recession and the rise of right-wing and left-wing populism. All of these developments cast doubt upon previous certainties – especially the efficacy of capitalism and the inevitability of democracy – and stimulated the tendency to speculate about how the past and present might have turned out differently.40

Counterfactuals and Postwar German History

This new climate has shaped perceptions of postwar German history. Until recently, the validity of the Federal Republic’s “success story” narrative was more or less taken for granted. When the narrative became solidified in the years leading up to the Federal Republic’s fortieth anniversary in 1989, there was little reason to question West Germany’s commitment to democracy and the western alliance; there was even less reason to question these commitments during the euphoric period following unification in 1990, when Francis Fukuyama’s claims about the inevitable triumph of liberalism made postwar Germany’s democratization seem equally inevitable.41 The growing uncertainty of the contemporary world, however, has challenged this deterministic viewpoint. It has also helped us appreciate the insecurities of the early postwar era. Because at the time of this writing (2018) we do not know the ultimate outcome of the “war on terror,” the future of the post-Brexit EU, or the fate of the United States under President Donald Trump, we can better grasp the concerns of people who, after 1945, feared that Germany’s young democracy might be threatened by a Fourth Reich. Aware as we are about our own world’s contingent character, we are more likely to entertain “what ifs?” about the postwar period.

It may sound unorthodox to speculate about events that might have happened, but German scholars have long sensed the potential in such an enterprise. Already a generation ago, Hans-Peter Schwarz argued that postwar German history could profitably be explained through the concept of “the catastrophe that never was.”42 By examining what failed to happen, he suggested, historians could better understand what did – namely, why postwar German history ended up being so stable. Other scholars have echoed this claim and called for an “imaginary history” of the Federal Republic – a history of “that which was expected, but never arrived.”43 Thus far, however, few have done much to advance this goal.

How might it be done? To begin with, it helps to adopt an alternative perspective on postwar Germany’s “success story.” Whereas most historians typically explain the country’s success by focusing on what went right, we can focus instead on what did not go wrong; rather than examining why Germany succeeded, we can focus on why it did not fail. Put simply, we can investigate why the Federal Republic never fell to a Fourth Reich. Reframing the story of postwar German history in this way is not a matter of slippery semantics. It is about examining two sides of a causal relationship. Historical events typically result from the interplay between existing “systems” and external “forces.”44 The more stable the system, the more difficult it is for an external force to affect it; the less stable the system, the easier it is for an external force to affect it. Historians have often applied this mode of reasoning to explain the rise of the Nazis. Heinrich August Winkler, for instance, has endorsed the argument that “Hitler came to power … not because the National Socialists … [were] so numerous … but because there were not enough democrats … to defend [the Weimar Republic].”45 Scholars who have analyzed the postwar Federal Republic have shared this focus on the existing “system,” rather than on oppositional “forces,” preferring to examine the policies that stabilized the postwar state rather than Nazi efforts to challenge it.46

This tendency reflects the widespread belief that Nazism was an extremely weak force in postwar Germany. As early as the 1950s, journalists insisted that there was “no [chance of] reviving the National Socialist corpse” in the Federal Republic, while in the 1960s, historians confidently dismissed the “fear that there may be a recurrence of the events of 1933.”47 Many recent scholars have advanced similar claims, declaring that Nazism after 1945 was “crushed” as a political tradition, “failed entirely” as a movement, and “never [posed] a serious threat to democracy in West Germany.”48 Convinced that Nazism appealed only to isolated “cranks” after 1945, scholars have insisted that “an antidemocratic right had no chance in the Federal Republic.”49

While these statements are factually accurate, they enjoy the benefit of hindsight and marginalize the instances after 1945 when Nazi forces threatened to overturn German democracy. These efforts first erupted in the occupation period, when conspiratorial campaigns to resist the installation of a democratic order were launched by fanatical Werewolf insurgents, unrepentant Hitler Youth leaders, committed SS men, and unbowed Wehrmacht veterans. In the early years of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s administration, between 1949 and the early 1950s, fears of “renazification” were sparked by the rise of the Socialist Reich Party (Sozialistische Reichspartei, or SRP) and the uncovering of the infamous “Gauleiter Conspiracy” headed by former Nazi Propaganda Ministry deputy Werner Naumann. Soon thereafter, the eruption of the “swastika wave” of 1959–60 revived concerns about the persistence of Nazi loyalists in West Germany, as did the rise of the National Democratic Party (Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or NPD) in the years 1964–69. In the 1970s and 1980s, the appearance of extreme right-wing demagogues, such as Manfred Roeder and Michael Kühnen, fanned fears of resurgent Nazism. And in the decades after German unification, concerns about growing right-wing extremism were stoked by the rise of neo-Nazi skinhead groups and New Right organizations affiliated with Hans Dietrich Sander’s journal, Staatsbriefe, the German College (Deutsches Kolleg), and the Reich Citizens’ Movement (Reichsbürgerbewegung).

Historians are familiar with all of these movements and have examined them with varying degrees of thoroughness. But they have overlooked their ties to the idea of a Fourth Reich. This oversight is surprising, given the idea’s frequent invocation by both its supporters and opponents. Throughout the postwar period, Nazi and other radical right-wing activists energetically pursued the creation of a new Reich and employed the concept as a rallying cry to inspire their adherents. Their critics in Germany and abroad, meanwhile, raised the alarming prospect of a Fourth Reich as a means to mobilize popular resistance to it. Empirically documenting the concept’s usage in postwar political discourse is the first step towards writing the history of the Fourth Reich. The second step is equally important, but more challenging – namely, interpreting the concept’s overall significance. It is common knowledge that all the Nazi efforts to create a Fourth Reich failed. Yet, to fully understand why, we need to ask how close they came to succeeding.

Employing counterfactual reasoning and examining scenarios in which history might have turned out differently helps address this important question. To be sure, this task represents a methodological challenge for the obvious reason that it is impossible to prove anything about events that never happened. Nevertheless, if we explore counterfactual scenarios responsibly by carefully considering their plausibility, we can ensure that the task of speculation is not overwhelmed by an excess of imagination. In part, this requires positing different points of divergence from the established historical record and imagining their varied consequences. Counterfactual reasoning, however, does not have to be a purely subjective enterprise. The rich secondary literature on postwar German history contains a surprisingly large number of short-form counterfactual claims by scholars that can also be employed in attempting to answer various “what if” questions. The task of synthesizing new and old speculative assertions is challenging, but worth the effort. By examining how narrowly the Federal Republic avoided a Fourth Reich, we can acquire a new perspective on the reasons for the country’s postwar stability.

By imagining how history might have happened differently, we can further address the important question of whether postwar fears of a Fourth Reich were warranted. Strictly speaking, the question answers itself. Because the Nazis never achieved their goals after 1945, fears of a Fourth Reich would appear to be exaggerated. Yet it would be wrong to dismiss them as entirely groundless. Doing so, first of all, would both reflect and perpetuate the chief weakness of the “success story” narrative – namely, its suggestion that Germany’s postwar democratization was more or less inevitable. Today, we know the ending of the dramatic story of Germany’s postwar recovery from military defeat. But what is now a settled past once lay in the future. In the years after 1945, Germany’s postwar narrative was still open-ended – a fact that caused anxiety throughout the western world. Putting ourselves in the position of contemporaries and taking their fears seriously enables us to better understand the factors that shaped the era’s events. Fears have long been an active force in history. As is shown by the ways in which modern political movements, such as nineteenth-century conservatism or twentieth-century fascism, exploited anxieties about looming revolution, fears about possible future events have often shaped the events that actually transpire.50 Some historians have endeavored to apply this insight to the postwar Federal Republic and have called for framing the country’s postwar history as a “history of fears.”51 Others have sought to explain why the intensity of these fears were out of proportion to the country’s stable reality.52 Building on these approaches, we can profitably assess the legitimacy of postwar fears of a Fourth Reich.

The Fourth Reich and the Memory of Nazism

In so doing, we can better understand the role that memory played in the Federal Republic’s postwar “success story.” Since the collapse of the Nazi regime in 1945, countless observers have urged the Germans to remember the “lessons” of the Third Reich in order to prevent history from repeating itself. In attempting to determine whether or not the Germans successfully fulfilled this task, scholars have examined how they pursued the difficult work of “coming to terms” with the Nazi experience. The scholarship on Vergangenheitsbewältigung, as it is known in Germany, is vast and has been advanced from many methodological perspectives.53 To date, however, few scholars have recognized that the postwar discourse on the Fourth Reich was a crucial part of this larger process of confronting the recent past.

In the years after 1945, the Fourth Reich was a signifier of competing positions on memory. The question of how to respond to the Nazi experience divided people both in Germany and abroad. Some, mostly on the left-liberal wing of the political spectrum, called for remembrance, demanding that the crimes of the Nazi era be documented and their perpetrators brought to justice. Others, typically on the center-right, argued for amnesia and amnesty, insisting that Nazi-era misdeeds be forgotten and their perpetrators integrated into postwar society. These opposing views about Germany’s past were directly correlated with worries about whether a new Reich loomed in the country’s future. On the one hand, “alarmists” in Germany and abroad were committed to remembrance and consistently stoked fears about the possibility of a Nazi return to power. On the other hand, “apologists” believed that Nazism had been permanently consigned to the past and dismissed postwar fears to the contrary as unwarranted. Examining how both groups employed the idea of a Fourth Reich reveals that it was influenced by different motives – some pure, others less so. Among the alarmists, some sincerely believed that a new Reich represented a serious possibility, while others instrumentally exploited the concept for ulterior motives. Among the apologists, some genuinely doubted that Nazism posed a real postwar threat, while others deliberately underplayed it to help boost Germany’s international image. Comparing the two groups’ intense debate on the Fourth Reich helps us understand how present-day forces shaped views of the past.

Studying the Fourth Reich as a reflection of memory, moreover, allows us to understand not just German, but also global, trends in remembrance. Starting in the 1960s, the concept of the Fourth Reich became increasingly normalized. Rather than being viewed as a signifier of a Nazi revival in Germany, it became universalized into a metaphorical harbinger of global fascism. Starting with the swastika wave of 1959–60 and the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1960–61, many people became convinced that the Nazi threat could emanate from places outside of Germany – whether Latin America, the Middle East, or the United States. Shortly thereafter, left-leaning political activists and intellectuals in the US and Europe – including H. Rap Brown, James Baldwin, and Régis Debray – employed the concept of a Fourth Reich to attack racism against African-Americans, the war in Vietnam, and the Watergate scandal. During the 1970s and 1980s, the term became further globalized to refer to other authoritarian states, whether Greece’s military junta or South Africa’s Apartheid regime. Since German unification in 1990, finally, the Fourth Reich has become further inflated into a signifier of global malfeasance. Right-wing European nationalists in Britain, Russia, and Poland have employed the idea to attack European integration, globalization, and westernization. Left-leaning activists in the US, meanwhile, have employed the term to attack symbols of authoritarian populism, such as Great Britain’s decision to leave the EU and Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States.

In addition to becoming universalized, the Fourth Reich has become aestheticized. Starting in the late 1960s and 1970s, the idea of a renewed Reich was increasingly featured in popular novels, films, television shows, comic books, and even punk rock songs. The more prominent examples included best-selling novels (and later hit films), such as Frederick Forsyth’s The Odessa File, Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil, and Robert Ludlum’s The Holcroft Covenant; episodes of the television shows Mission Impossible, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and Wonder Woman; issues of DC and Marvel comic books, such as Batman and Captain America; and songs by the Dead Kennedys and the Lookouts. This trend has continued up to the present day, whether in ironically minded films, such as Iron Sky, or ambitious Internet dramas, such as Amazon’s The Hunt.54 These works have been inspired by a variety of motives, but many of them have exploited the premise of a Nazi resurgence for profit and entertainment, thereby dimming its moral thrust. As a result of these normalizing trends, the idea of the Fourth Reich has become unmoored from its original referent – the idea of a Nazi return to power in Germany – and become an all-purpose signifier of evil. Through this process, it has lost some of its admonitory credibility.

The Fourth Reich in History and Memory

This book examines the evolution of the Fourth Reich in postwar western life by adopting both a chronological and a thematic approach. The first part of the book focuses on the Fourth Reich’s origins in, and impact on, Germany from the early 1930s to the early 1950s. Chapter 1 shows how the idea emerged as an anti-Nazi rallying cry among a wide range of dissident groups, including left-leaning German-Jewish exiles, conservative Wehrmacht officers, and renegade National Socialists. In response, Nazi government officials sought to suppress the concept, a fact that initially led British and American observers to view the Fourth Reich as the hopeful symbol of a future democratic Germany. As the Second World War neared its conclusion, however, Anglo-American fears that Nazi loyalists were going underground to resist Allied forces transformed the Fourth Reich into an admonitory symbol of unrepentant Nazi fanaticism. Chapter 2 focuses on the ensuing Allied occupation of Germany from 1945 to 1949 and describes how American and British military officials, journalists, civilian lobbying organizations, novelists, and filmmakers continued to warn about the prospect of a Fourth Reich unless the Allies purged Nazism from all areas of German life. This fear reflected the fact that committed Nazis during this period actively sought to overthrow the Allied occupation and revive the Reich. They included the Werewolf insurgency of 1945–46, the attempted coup led by Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann in 1945–46, and the “Deutsche Revolution” plot led by SS and Wehrmacht veterans in 1946–47. Allied forces ultimately suppressed the revolts, but by imagining certain counterfactual scenarios, it is possible to see how they might have succeeded. Chapter 3 examines how Nazi resistance movements continued after the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949 by examining the rise of the SRP and the uncovering of the Gauleiter Conspiracy in the years 1950–52. Like the coup attempts of the occupation period, these threats were also crushed. But had circumstances been slightly different, they might have been more successful. In recognizing West Germany’s vulnerability to the Nazi threat during this period, it becomes clear that fears of a Fourth Reich were hardly baseless.

The second part of the book covers the 1960s up to the present and explores how the idea of a Fourth Reich spread beyond, but ultimately circled back to, Germany. Chapter 4 describes how fears of a Nazi comeback in the Federal Republic were revived by the eruption of the “swastika wave” in 1959–60 and the rise of the NPD from 1964 to 1969. These fears ultimately proved to be unwarranted, but they did not entirely disappear. Around the same time, new concerns arose that Nazism was emerging in the United States. During the 1960s, the rise of the American Nazi Party, the racist backlash against the Civil Rights Movement, the escalation of the war in Vietnam, and the scandalous behavior of the Nixon administration prompted left-liberal Americans to claim that a Fourth Reich was dawning in America. These claims played an important role in normalizing the Fourth Reich by universalizing its significance. The normalization process was also promoted by the aestheticization of the Fourth Reich in popular culture. Chapter 5 explains how, during the “long 1970s,” the fear of a Nazi return to power was transformed into a source of mass entertainment in Anglo-American works of literature, film, and television. This cultural turn represented a major development in the postwar evolution of the Fourth Reich, but it was abruptly halted in 1989–90, with the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the unification of Germany. Chapter 6 shows how, starting in the 1990s and continuing after the turn of the millennium, the Fourth Reich was “re-Germanized” and became a topic of renewed political concern. All across Europe, worried observers voiced the fear that the Federal Republic was heading in a right-wing, if not neo-Nazi, direction. Some of the claims were grounded in legitimate concerns, as right-wing German intellectuals were busy theorizing the political basis for a future Fourth Reich. Yet other claims, especially those articulated in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis in countries like Greece, Italy, and Russia, were more tendentious and expressed cynical domestic and foreign policy calculations.

How the Fourth Reich will evolve in the future is uncertain. But the book’s conclusion explores the possibility that it will remain an appealing signifier in a world of growing uncertainty. To date, the term has largely served as an ominous slogan of admonition. But there is no saying it will not evolve into a term of inspiration. Given the ways in which Nazi groups have kept the term alive since 1945, it is conceivable that under the right conditions, the idea of a Fourth Reich could one day experience a popular renaissance.