In the early months of 1861, two fortresses, both near a major port-city in the midst of a revolution, but thousands of miles apart from one another – one in America, the other in Italy – were under siege. In April of that year, at Fort Sumter, at the entrance of Charleston harbor, General Robert Anderson’s U.S. army contingent was attacked and overwhelmed by the South Carolina militia of the newly formed Confederate States of America under the command of General P. T. Beauregard. Two months earlier and a continent away, in February 1861, at the fortress of Gaeta, close to the bay of Naples, Bourbon King Francis II’s soldiers were defeated as a result of ruthless shelling by General Enrico Cialdini’s Piedmontese troops, soon to become part of the army of the recently unified Kingdom of Italy. Although happening in two different parts of the world, these two sieges had some important features in common. To begin with, they both occurred in a southern region, one in the American South, the other in southern Italy, or the Mezzogiorno. More importantly, they both had enormous symbolic and practical significance as foundational acts for the birth of a new nation-state: the Confederate States of America, or Confederacy, in one case, and the Kingdom of Italy in the other. In America, Beauregard’s victory over the U.S. army at Fort Sumter simultaneously eliminated the last significant remnants of Federal presence in the south and strengthened the new Confederate nation, as four Southern states joined the secession movement already underway in seven states in the Lower South and left the American Union as a result of the siege. On the other hand, in Italy, Cialdini’s conquest of Gaeta represented the defeat of the last major resistance by the army of the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies against the movement for Italian national unification, and resulted in the exile of Bourbon King Francis II and the annexation of the Mezzogiorno to the Italian Kingdom.Footnote 1

Even though the siege of Fort Sumter was much shorter than the one at Gaeta, the leadup to the event and the political and military crisis related to it were longer. It all started when the state of South Carolina proclaimed its secession from the Union on December 20, 1860; as a result, all Federal military installations in South Carolina were regarded with hostility. After General Anderson secretly relocated with his 1st U.S. artillery to the still unfinished Fort Sumter on December 26, 1860, South Carolina Governor George Pickens demanded from President Buchanan its immediate evacuation, to no avail. Instead, on January 9, 1861, fire from the Charleston citadel prevented the U.S. steamer Star of the West from bringing food and supplies to Anderson and his 127 men, who were by now completely surrounded by the batteries arranged by Beauregard. Stalemate ensued, as Buchanan decided not to act and instead to let president-elect Abraham Lincoln deal with the crisis while Anderson’s contingent ran short on supplies. After Lincoln was installed, on March 4, he faced a potentially explosive crisis and decided to notify Pickens of his intention to send a fleet to resupply Fort Sumter, knowing that the Confederates would have taken his decision as an act of war. In fact, this led to Beauregard’s ultimatum to Anderson, and, after the latter’s refusal to surrender, to the ensuing Confederate attack with heavy artillery bombardment on April 12. By April 14, the Battle of Fort Sumter was over, with the surrender of the U.S. military garrison and the victory of Beauregard’s Confederate forces. As a direct consequence of the battle’s outcome, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers in preparation for the upcoming Civil War, while 4 Upper South states, including Virginia, joined the original 7 seceding states in the Lower South in breaking from the Union and forming the Confederate nation.Footnote 2

Similar to Fort Sumter, the siege of Gaeta was also a defining act in a process of nation-building; significantly, it was also a major confrontation aiming at crushing the last surviving military presence of a former nation and asserting complete territorial control in the name of a new national government. One important difference, though, is that it occurred on a much larger scale, since the fortress of Gaeta was the last refuge of a large contingent of Bourbon troops – ca. 16,000 – which had accompanied King Francis II when he fled from Naples as Giuseppe Garibaldi approached the city in September 1860, in the process that led to Italian national unification. After taking one last stand at the Battle of Volturno, where they were defeated by Garibaldi, on October 1, 1860, the Bourbon troops retreated to Gaeta, where Cialdini and his Piedmontese troops began the siege on November 13, mostly conducting it through continuous shelling with little care for the civilians living in the town. On December 8, Piedmontese and Bourbons reached a temporary truce as a result of pressure from French Emperor Napoleon III, but this only lasted five days, and shortly afterward, a typhus epidemic broke out within the fortress. A new truce followed on January 8, 1861, but ended eleven days later, after Francis II’s refusal to surrender. Between January 22 and February 13, Cialdini’s shelling intensified, leading to an increasingly large toll of dead and wounded Bourbon soldiers and civilians. Finally, on February 14, the siege concluded with Francis II’s surrender and his subsequent exile, and with a final death toll of almost 1,000 dead on the two sides. As a direct result of Cialdini’s victory at Gaeta, the last territory ruled by the Bourbon king of the Two Sicilies ceased to exist, and the entirety of the Mezzogiorno – aside from the two fortresses of Messina and Civitella del Tronto – was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy.Footnote 3

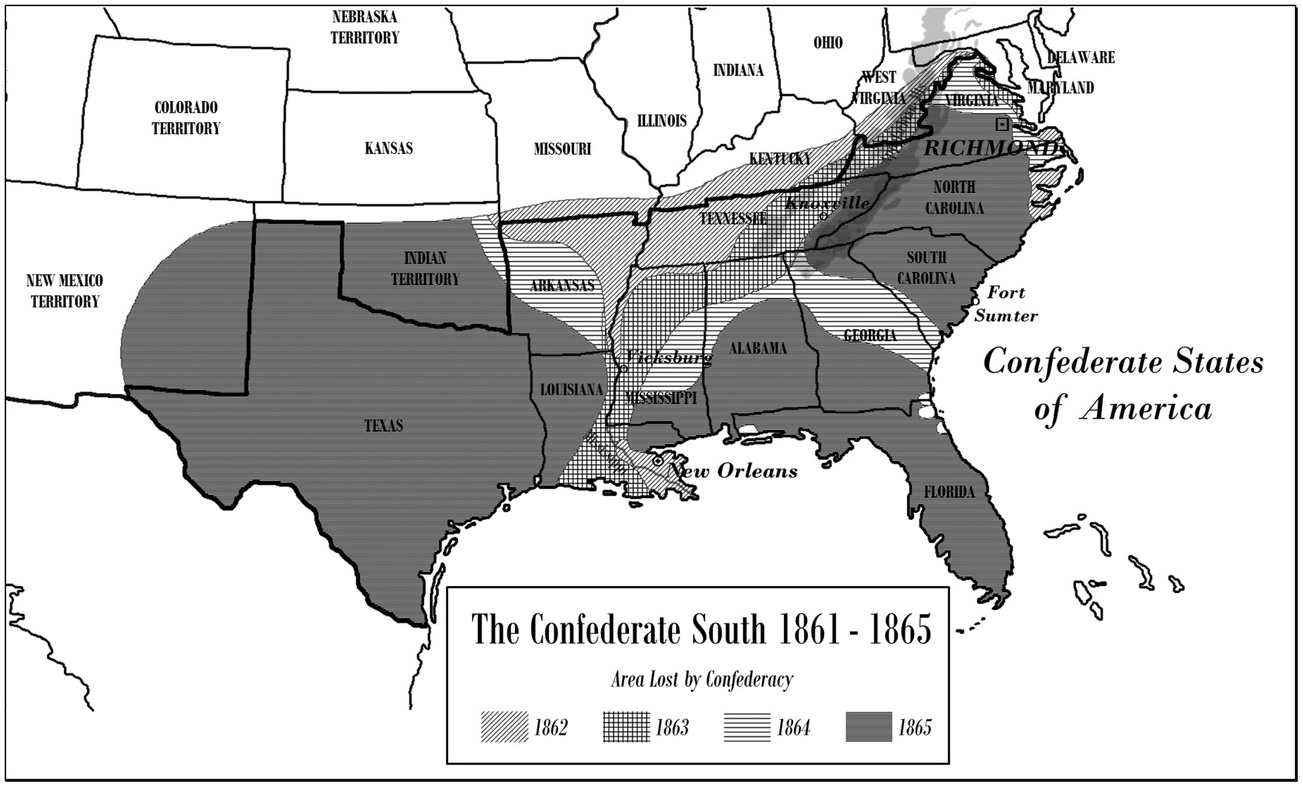

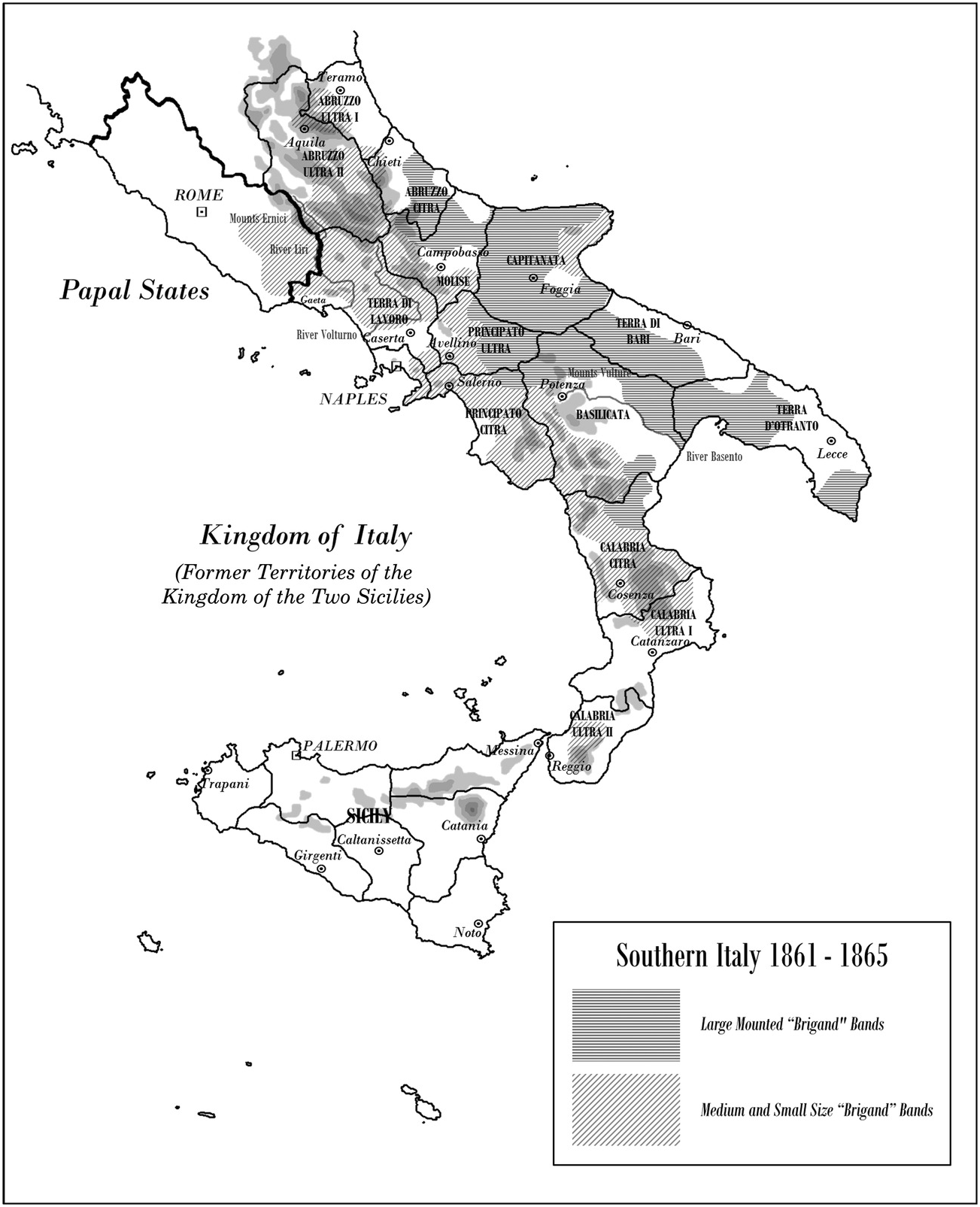

In one particularly important respect, the sieges of Fort Sumter and Gaeta are comparable and relate directly to the subject of the present book. They were both events that sparked civil wars, both occurring in the period 1861–5. In fact, while U.S. scholars consider the Confederates’ taking Fort Sumter as the first battle in the American Civil War, Italian scholars see a link between the Bourbon defeat at Gaeta and the beginning of Italy’s first civil war, known as the “Great Brigandage.” Both civil wars were fought either largely or exclusively on southern soil, and both involved different groups of Southerners with different and conflicting loyalties with regard to national affiliation, so that it is possible to say that in both cases an “inner civil war” occurred between southerners and southerners within a south – in one case, the Confederate South (see Map 1); in the other, southern Italy (see Map 2).Footnote 4 In this respect, thus, the events at Fort Sumter and Gaeta and the reactions to them are emblematic of the internal divisions within the two southern regions that would characterize the two inner civil wars – one between Unionists and Confederates, the other between pro-Bourbons and pro-Italians. At the same time, though, the divisions between opposing and conflicting national affiliations cut across even deeper separations in racial and class terms in the Confederate South, and in class terms in southern Italy. Thus, the nature of the inner civil wars in the two southern regions related also to other, equally important, elements represented by the crucial roles played by the exploited agrarian masses – specifically, Southern slaves and southern Italian peasants – in supporting the established national institutions – i.e., the Union and the Bourbon monarchy – in their wars against the newly established nations – the Confederacy in one case, and the Italian Kingdom in the other.Footnote 5

Map 1: The Confederate South, 1861–1865

Starting from these premises, my aim in the present book is to provide a sustained comparative study of the inner civil wars that occurred in the Confederate South and southern Italy in 1861–5 along the lines just described. As modern scholarship on nationalism has shown, nineteenth-century nations were steeped in an “invention of tradition,” and they were mostly born in war and revolution.Footnote 6 As new nations, both formed in 1861, the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom were no exception to this pattern: They both forged their “invented tradition” of nationality in the midst of military events that accelerated the process of nation building by rallying against a common enemy, while they also risked being torn apart if that enemy proved to be stronger. Clearly, there is a great deal of difference between, on one hand, the Confederacy’s war on a continental scale against the stronger and more industrialized Union, and also its simultaneous efforts to deal with opposition from within, and on the other, the Italian Kingdom’s regional war – conducted within its territories in the south, and from a far stronger position than that of its internal enemy, though with little difference between northern and southern Italy in terms of industrialization. Yet, at the heart of my study are two parallel and comparable phenomena of internal dissent, which, regardless of differences in terms of scale and coexistence with, or absence of, large pitched battles, proved to be the ultimate defining tests for the survival of two newly formed nations. It is important to reflect on the odds that allowed the survival of new national institutions in the nineteenth century, since, despite the fact that the nineteenth century was the “age of nationalism,” not all nineteenth-century nationalist experiments survived. At the same time, virtually all the nations that came into being during that period – whether they disappeared after a short time, or managed to adapt and live on through structural transformations – were plagued by one form or another of internal dissent. Therefore, investigating internal dissent in newly formed nineteenth-century nations such as the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom is equivalent to trying to understand why certain nineteenth-century nations survived and others did not.Footnote 7

In short, the central question I have investigated in writing the present book is the following: How did nineteenth-century newly formed nations cope with internal dissent, and how crucial was the role played by the latter in threatening the survival of those new nations, to the point of bringing about their collapse? To answer this question, I have focused on the Confederate South and southern Italy in the civil war years 1861–5, because the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom provide a perfect example of what Theda Skocpol and Margaret Somers have termed a “contrast of contexts.” In practice, the two nations’ different contextual histories, the different processes of nation-building, and, above all, their completely opposite historical trajectories – one of disappearance, in the case of the Confederacy, and the other of survival, in the case of the Italian Kingdom – render them particularly intriguing case studies for a historical comparison, with each therefore liable to shed new light on the other’s case. Thus, while in previous studies I have at times attempted to adopt a mixed comparative/transnational approach to historical investigation, in the present book I have opted for an exclusively comparative historical methodology, since I believe that, by engaging in a sustained comparison of the different varieties of internal dissent that generated “inner civil wars” in the Confederate South during the American Civil War and in southern Italy in the years of the Great Brigandage, it is possible to offer an important contribution toward answering the reasons for the survival or disappearance of new nations in the course of the nineteenth century. At the same time, in contributing to this particular historical problem, I have also sought to provide, through this specific comparison, a possible model for future studies that might focus on comparing the reasons for the divergent historical trajectories of other newly formed nation states in the nineteenth-century Euro-American world.Footnote 8

Methodologically, for the most part, in the present book I have used a “rigorous” approach to the comparative history of the Confederate South in the American Civil War and southern Italy at the time of the Great Brigandage. According to Peter Kolchin, “rigorous comparative analysis” is a historical method in which two or more cases are the object of a systematic and sustained comparison aiming at highlighting their similarities and differences.Footnote 9 There are currently relatively few examples of this methodological approach, mainly because of its difficulties; a great deal of them have been produced by scholars of comparative slavery, mostly in the Americas – a field recently revitalized by the important nuances coming from the scholarship on the “second slavery,” the collective name for the profit-oriented and capitalist-based slave systems that characterized the nineteenth-century U.S. South, Brazil, and Cuba, following Dale Tomich and others.Footnote 10 Fewer “rigorous” comparative monographs have dealt with slave emancipation in the American South in comparative perspective; among those which have, especially notable are those by Eric Foner, Frederick Cooper, Thomas Holt, and Rebecca Scott.Footnote 11 There are also few “rigorous” comparative studies that have focused on comparison between economic, social, and political features of the American South and of specific regions of Europe, specifically slavery vs. free or unfree labor; those that exist include monographs by Peter Kolchin and Shearer Davis Bowman, and also my own work.Footnote 12 However, none of these studies has dealt specifically with the American South during the Civil War and other regions of the world at the same time, while only a very limited number have dealt with the American Civil War and a conflict in another country by employing a “rigorous” comparative perspective.Footnote 13 At the same time, there is no comparative study that has focused on the Italian Mezzogiorno at the time of the Great Brigandage.

Thus, the present book is the first study of the American Civil War and Italy’s Great Brigandage that utilizes a “rigorous” comparative approach throughout.Footnote 14 In short, my methodological approach is focused specifically on the analysis of similarities and differences between the different factors involved in the two parallel processes of challenge to national consolidation that occurred in the inner civil wars that characterized the Confederate South and the Italian Mezzogiorno in the years 1861–5. In undertaking this analysis, I have relied specifically on the already cited comparative method of the “contrast of contexts” – a method whose aim is “to bring out the unique features of each particular case … and to show how these unique features affect the working out of putatively general social processes.”Footnote 15 I believe that investigating and understanding the specific challenges to nation building in the Confederate South during the American Civil War and in southern Italy at the time of the Great Brigandage is an exercise in the application of the methodology of “contrast of contexts” as Skocpol and Somers have defined it. This methodology is particularly apt for clarifying through a comparative perspective the actual meaning of concepts such as “civil war” and “agrarian rebellion,” and the significance of their use in relation to the Confederate South and southern Italy in the years 1861–5, as will become evident in the course of the present book.Footnote 16

Looking at the period during which the American Civil War and the Great Brigandage took place from a broader perspective, we can clearly see that the decade of the 1860s was one of intense warfare in the entire Euro-American world, and often a type of warfare associated with processes of nation building. In their seminal 1996 study on “Global Violence and Nationalizing Wars in Eurasia and America,” Michael Geyer and Charles Bright dispelled the once popular notion of a peaceful nineteenth century following the catastrophic Napoleonic conflicts, and showed that, across the world, 112 wars were fought in the period 1840–80. A number of these wars were fought in Europe and the American hemisphere in the 1860s, and among the eight most costly wars of that forty-year period, three – the American Civil War (1861–5) and the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–70), recently compared by Vitor Izecksohn,Footnote 17 and the Ten Years’ War between Cuba and Spain (1868–78) – were fought in the New World, the latter with the full involvement of a major European nation. Moreover, either national consolidation or nation-building were the prime causes behind those three wars, and this was also the case with other, smaller conflicts that occurred in the 1860s. These included, in Europe, the Wars of Italian National Unification (1859–70), the 1863–4 Polish Uprising, the Second Schleswig-Holstein War (1864), and the Prussian-Austrian War (1866) – the latter two both parts of the process of German National Unification – and in the Americas, the Franco-Mexican War (1862–7).Footnote 18 Warfare in the 1860s Euro-American world, therefore, was strictly linked to the construction of nations.Footnote 19 A well-established scholarship on nation-building has described the two main models of construction of nations in nineteenth-century Europe as “unification nationalism” and “separatist/peripheral nationalism.” We can extend this classification also to the Americas, and argue that all the conflicts previously cited could be grouped under one or the other of these two categories as manifestations of processes of nation-building and/or national consolidation.Footnote 20

According to Michael Hechter, “unification nationalism involves the merger of a politically divided but culturally homogenous territory into one state” and “aims to create a modern state by eradicating existing political boundaries and enlarging them to be congruent with the nation.”Footnote 21 As we might expect, with regard to Europe, Hechter cites the classical cases of the wars of Italian and German national unification, mostly occurring in the 1860s, in both of which nation building entailed a politico-military operation of incorporation of smaller independent polities into a larger unified nation state. In the process, according to John Breuilly, the political elites that created the territorially unified nation state also created a new constitutional order using “the language of nationality” to fuse “the principles of territoriality and constitutionalism,” thus completing “a transition from older to newer forms of politics.”Footnote 22 With regard to the Americas, this process resonates particularly with the reunification of the United States in the American Civil War, since the latter also entailed the political elites’ creation of a territorially homogenous and modern nation state at a time when the American national territory was divided between the two polities of the Union and the Confederacy, as scholars such as David Potter, Carl Degler, and Peter Parish, among others, have remarked. Significantly, all of these scholars have also noted that with that creation came also a new constitutional order dominated by the free labor principles of the Republican Party – which, with the Union’s victory in the Civil War, defeated the slaveholding principles at the heart of the creation of the Confederacy.Footnote 23

In contrast to “unification nationalism,” which seeks to make a new unified nation, separatist or “peripheral nationalism” – according to Michael Hechter – “occurs when a culturally distinctive territory resists incorporation into an expanding state, or attempts to secede and set up its own government.” Thus, “peripheral nationalism seeks to bring about national self-determination by separating the nation from its host state,” through a process of secession that seeks to unmake an existing nation.Footnote 24 In studying this process in nineteenth-century Europe, with particular reference to the Habsburg empire, John Breuilly has identified the threat brought by an existing state against major regional institutions and the opposition to the state advanced with the use of the language of nationalism by regional elites, i.e., by “privileged groups entrenched within those institutions,” as key elements in separatist/peripheral nationalism.Footnote 25 This is a model that applies well to both the 1860s European attempts at nation building through separation from host states, as in the case of Poland with Russia, and to contemporaneous events in the 1860s Americas, specifically the secession of the southern Confederacy from the United States – as recent studies by Paul Quigley and Niels Eichhorn have pointed out – and also Eastern Cuba’s rebellion against Spain in the Ten Years’ War. In all these cases, powerful regional elites led experiments in nation building that entailed breaking away from an already existing polity, mostly with little success.Footnote 26

Whether the attempt at nation building occurred through “unification nationalism” or “separatist/peripheral nationalism,” though, a crucial component for its success was the common perception of the national struggle, and therefore of the nation that would emerge from that struggle, as legitimate, both externally and internally.Footnote 27 Thus, for Breuilly, on one hand, “the problem of legitimacy [was that of] … convincing outsiders of the nationalist cause,” especially the great movers of international diplomacy, while on the other, nationalism was also “a way of making a particular state legitimate in the eyes of those it” controlled.Footnote 28 Therefore, in attempting to build a new nation either through unification or through secession, the political elites in charge ought to convince the citizens/subjects that their rule of the new nation was legitimate, and had to justify as equally legitimate their national cause and their national struggle in the international arena. With regard to Europe, in the case of Italy, Poland, and Germany – examples of either “unification nationalism” or “separatist/peripheral nationalism” – the legitimacy of the national struggle relied on “the search for liberal constitutional government against the illiberal regimes of Austria and Russia and, to a lesser extent, Prussia … in the eyes of France and Britain,” as Breuilly has noted.Footnote 29 Thus, the legitimacy of the national struggle coincided with support for the progressive cause of creating liberal national institutions that would have replaced backward reactionary governments. This was the same rationale that had been behind the creation of the Latin American Republics in the early part of the nineteenth century, and its influence was stronger than ever in several parts of the Americas in the 1860s, especially in Mexico, torn by the struggle between Benito Juarez’s Liberals and the French-supported Emperor Maximilian.Footnote 30 A similar rationale also had guided Piedmontese and then Italian Prime Minister Camillo Cavour and his party, the Moderate Liberals, in supporting Italian National Unification, and, most notably, Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party in the American Civil War.Footnote 31 Here, the war between Lincoln’s Republican Union and the Southern slaveholders’ Confederacy came to incarnate the very struggle between progress and reaction in the eyes of many Europeans, as Don Doyle has recently shown in The Cause of All Nations.Footnote 32 Thus, a specific comparison between the United States and Italy in the first half of the 1860s helps us understand the importance of the issue of legitimacy in Euro-American processes of nation building, whether these occurred according to the model of “unification nationalism” or of “separatist/peripheral nationalism.”

In particular, if we look at Civil War America from the point of view of “peripheral/separatist nationalism,” there is little doubt that, in the 1860s Euro-American world, the Confederate states’ secession from the Union was the most exemplary case study in this sense. Yet, despite the appearance of the contrary, the formation of the Confederacy through “peripheral/separatist nationalism” also shared important features with the formation of Italy through the opposite process of “unification nationalism.” In particular, these two processes, though opposite, ended up creating two new, and thus comparable, political entities that similarly aspired to the title of legitimate nations. Yet, both the Confederacy in 1861 and the Italian Kingdom after Cavour’s untimely death in the same year were hardly in a position to be granted legitimacy in the international arena. For international diplomats, the only recognized government in the United States was the Union, whose official position was that the creation of the Confederate nation out of the eleven seceding Southern states – between December 20, 1860 and June 8, 1861 – was little more than a treasonous rebellion to be subdued. Likewise, with Cavour’s death and the end of his diplomatic efforts, the Kingdom of Italy was left in an uncertain diplomatic position in the international arena, since the overthrow of the southern Italian Bourbon dynasty, perpetrated by the Piedmontese army without a formal declaration of war, cast a long shadow over the legitimacy of the new Italian nation.Footnote 33

The question of legitimacy, though, was equally crucial in both the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom, especially with regard to its effects on internal divisions and on the dissent manifested by southern Unionists in one case and by southern Italian Bourbon supporters in the other. This, together with other factors, led to the explosion of comparable inner civil wars in the Confederate South and southern Italy, with movements that opposed the two new nations in the form, in both cases, of guerrilla warfare fought in particular areas – especially Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and North Carolina in the Confederacy and Terra di Lavoro, Principato Citra, Principato Ultra, Basilicata, Capitanata, and Terra di Bari in southern Italy. At heart, the two inner civil wars were vicious struggles between those who supported the new nations – the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom – with the help of the regional governmental and military authorities, and those who, instead, aimed at destabilizing the new governments and reestablishing the old ones – the American Union and the Bourbon Kingdom. Also, in both cases, the inner civil war between opposing types of nationalism was both a political and a social conflict; it also aimed at settling grievances held by the less privileged sections of the populations against the agrarian elites that mostly supported the new nations because they benefited most from them.Footnote 34

In America, from the time of the Confederacy’s formation in February 1861 up to the end of the first year of the American Civil War and until late 1862, the Confederacy showed that it was able to remain independent and, through a series of important victories, convinced the Union government that the war to bring the seceded states back into the fold would be long and costly. Also as a result of these initial Confederate successes, pro-Union activities and anti-Confederate sentiment within the Confederacy maintained a relatively low profile for a while, even though in several areas loyalties were so divided that the state governors had to take severe measures against open boycotting of the Confederate government, or against secret Unionist organizations, or even against the formation of Unionist guerrilla groups. In other words, in 1861–2, anti-Confederate and Unionist forces were organizing themselves. After the enforcement of the Confederate Conscription Act of April 16, 1862, a number of disaffected young Southerners – many of whom were yeomen who resented the exemption of the planter class from military service – and deserters joined the ranks of the Unionists. By later the same year, after the Union inflicted a resounding victory on the Confederacy at the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Unionist activities – which were the expression of a combination of political and social matters – had become the heart of a prolonged inner civil war within the Confederacy and against the Confederate authorities in a number of areas, as shown by important recent studies such as, especially, Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning.Footnote 35

Little more than a month after the Confederacy began its existence, in March 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was formed in Turin, and southern Italy was caught in the middle of its own inner civil war, comparable to the Confederate South’s inner civil war: the Great Brigandage, fought between the pro-Bourbon forces on one side and the National Guard and the Italian troops on the other side. Those who sided with the Bourbons considered themselves “legitimist” as they aimed to restore the legitimate Bourbon king, Francis II, to his rightful place. Several of them came from abroad to help, among them especially Spanish officers who had been defeated in the recent Carlist wars. Throughout 1861 and 1862, large mounted bands of “brigands,” mostly made of peasants and ex-Bourbon soldiers and helped by foreign officers and troops, fought for the legitimist cause and the restoration of Francis II, whose government in exile in Rome provided help and support, in a number of areas of southern Italy. Simon Sarlin’s Le légitimisme en armes and a few other recent studies have investigated the course of legitimist activities and the tortured relationship between Francis II’s government in exile, the brigands, and the foreign officers and volunteers for the Bourbon cause.Footnote 36

Although for very different reasons, in the cases of both the Confederate South and southern Italy in 1862–3, the crisis of legitimacy reached a point of no return in terms of escalation of conflict between supporters of opposite nationalisms. At the same time, both inner civil wars witnessed largescale rebellions carried out by the exploited agrarian masses of the two southern regions for different but comparable social and political reasons. In fact, within the contexts of the two crises of legitimacy in the Confederate South and in southern Italy, the numerous and widespread episodes of unrest caused by the agrarian masses represented an essential component. While on a different scale and in different ways, as a result of its duration and geographical extension, particularly from 1862–3 onward, in both cases agrarian unrest deeply affected the course of the inner civil wars in the Confederate South and southern Italy and the social structure of the two regions, particularly the relationships between the two agrarian elites and the agrarian workers – specifically, the African American slaves and freedpeople (after emancipation) in one case, and the southern Italian peasants in the other. Also, the laborers’ revolts assumed very different aspects in the two southern regions, as a result of the Union Army’s contribution to the slaves’ insurrection in the Confederate South, which stood in stark contrast to the fight undertaken by southern Italian peasants on their own after the defeat of the pro-Bourbon forces.Footnote 37

In the Confederate South, the African American slaves’ own struggle for freedom, particularly from 1862–3 onward, inserted itself within the framework of a Confederacy already torn apart from within, as a number of studies by Ira Berlin and other scholars have revealed in the past thirty years.Footnote 38 In his work, Steven Hahn has shown how, during the American Civil War, the slaves’ relationships of mutual solidarity and kinship networks were instrumental in creating the preconditions for a variety of defiant actions that disrupted the slave system as a whole. In this sense, emancipation, when it came, acted as a catalyst for a number of rebellious acts that now found a logical conclusion. More than thirty years ago, Leon Litwack wrote that “the extent of black insurrectionary activity during the Civil War remains a subtle question.”Footnote 39 Thirty years later, Steven Hahn asked himself if, by not acknowledging the massive – even though diverse and unconnected – number of rebellious acts in the Civil War in the same collective way that we acknowledge the slaves’ rebellious acts in the Haitian Revolution, we had not missed the largest slave rebellion that ever occurred, during the American Civil War. In this regard, Stephanie McCurry’s work has gone in a similar direction, since she has argued very forcefully that a massive slave rebellion did take place in the Confederate South during the Civil War. That rebellion built on what W. E. B. Du Bois termed a “general strike” engaged in by the slaves and ultimately culminated in 180,000 African Americans’ enlistment in the Union Army by 1865.Footnote 40

Comparable to events in the Confederate South, in southern Italy the inner civil war also entered a new phase in 1862–3, as the brigands’ bands multiplied and there was sizeable participation of the peasant masses in guerilla warfare amounting to a class war in several regions. The Italian government responded to the emergency by sending an army that, by the end of the conflict, would number more than 120,000 men. In October 1863, the Italian Parliament passed the infamous Pica Law, which would be enforced over the next two years. It gave military authorities the power to maintain martial law in all the provinces of southern Italy where brigandage was present, leading to countless imprisonments and executions not just of brigands but also of civilians.Footnote 41 In interpreting the rebellious peasants’ actions during the Great Brigandage, scholars have taken substantially different views. Some have emphasized the social dimensions of the phenomenon, while others have looked at its delinquent elements or at the importance of the northern soldiers’ and civil servants’ mostly hidden racial prejudices against southerners; most recently, several scholars have considered the political aspirations of pro-Bourbon supporters.Footnote 42 Increasingly, though, a number of historians – among whom Salvatore Lupo, John Davis, and Carmine Pinto particularly stand out – have argued that, in Lupo’s words, the Great Brigandage “assumed more clearly the character of a civil war … because the conflict concerned only Italians,” and in many parts of southern Italy, mostly southerners.Footnote 43

I believe that a comparative perspective can offer an important contribution to the study of the inner civil wars in the Confederate South and southern Italy, since the experience of civil war in the Confederate South can help us shed light on the features of civil war of southern Italy’s Great Brigandage, while the Great Brigandage’s characteristics of agrarian rebellion can help us shed light on the nature of the slave rebellion that took place in the Confederate South. In practice, in the present book, I have investigated the processes I have just briefly described in order to assess the degree and extent to which radical social change occurred in the Confederate South and in southern Italy in 1861–5. My central thesis is that two subsequent phases, partly overlapping, of two inner civil wars, with two different, but comparable, types of conflict and agrarian unrest characterized the Confederate South and southern Italy in 1861–5. In both cases, a conflict between opposite nationalisms that featured antigovernmental guerrilla operations in 1861–3 partly overlapped, and partly was followed by, massive agrarian unrest, rebellion, and either occupation or invasion of landed estates in 1862–5. Both these phases were instrumental in temporarily weakening the power of the agrarian elites that had ruled over the two southern regions. However, after the end of the two inner civil wars, the elites of both regions regained much of their power and fought back against the reestablished national governments, leading in the process to the creation of traditions of local antistate violent activities. In comparable terms, therefore, with regard to both the Confederate South and southern Italy, we can speak of revolutions that remained unfinished or incomplete, and we can say that the legacies of these incomplete processes shaped the future and the subsequent histories of the American and Italian nations.

Maintaining as frameworks the general contexts I have briefly described, in the present book I have focused on specific regions of the Confederate South and southern Italy in my comparative analysis of the two inner civil wars. In the first part of the book, I have analyzed the inner civil wars between opposite nationalisms in relation to events occurring in East Tennessee and Northern Terra di Lavoro. On one hand, East Tennessee was at the center of extensive Unionist networks and Unionist guerrilla activities, which, in 1861–3, disrupted Confederate authority in the area to such an extent that the Confederate government resorted to martial law. Civil War scholars have long recognized the importance of East Tennessee’s Unionist guerrilla warfare within the Confederate South’s inner civil war and have provided several accounts of Unionist activities – particularly in studies by W. Todd Groce, Noel C. Fisher, Robert Tracy McKenzie, and John Fowler.Footnote 44 Comparably to East Tennessee, Northern Terra di Lavoro was one of the main centers of guerrilla warfare undertaken by the legitimist forces which tried to restore the Bourbon state by fighting against the National Guard and the Italian army in 1861–63 – also leading to the implementation of extreme military measures. The importance of Northern Terra di Lavoro in the study of pro-Bourbon brigandage against the Italian state emerges especially in studies by Michele Ferri and Domenico Celestino, Fulvio D’Amore, and Simon Sarlin.Footnote 45 In comparable terms, East Tennessee and Northern Terra di Lavoro were close to borders with regions that were either part of the enemy institution – in the case of Kentucky and the Union government – or hosted the enemy institution – in the case of the Papal State that hosted the Bourbon government in exile – which waged war against the new nation, whether the latter was the Confederacy or the Italian Kingdom, and which played a major role in supporting antigovernmental guerrilla activities. Thus, by looking in comparative perspective at the features and protagonists of guerrilla actions in East Tennessee and in Northern Terra di Lavoro, I have sought to contribute to a better understanding of the wider dynamics of conflicting nationalisms in the inner civil wars within the Confederate South and southern Italy in 1861–3.

Still maintaining the overall framework sketched out previously, in the second part of the book I have analyzed the aspects of social revolution that involved the agrarian masses particularly in the later parts of the two inner civil wars, or in the period 1862–5, by focusing specifically on events that occurred in the Lower Mississippi Valley and Upper Basilicata. In the Lower Mississippi Valley, in the Confederate-held areas, African American slaves rebelled and in some cases took control of plantations even before the Union army arrived in 1863, as McCurry has shown in relation to Mississippi.Footnote 46 At the same time, however, I have argued that rebellious activities were routinely carried out also by freedpeople in the Lower Mississippi Valley’s Union-held areas, such as southern Louisiana, as a result of the Union government officials’ ambiguous attitude toward the fundamental issues of African American emancipation and landownership. In investigating these issues, I have placed particular emphasis on both the slaves’ and the freedpeople’s wish to end their labor exploitation and to own land, by relying on an established scholarship which includes, among others, work by C. Peter Ripley, John C. Rodrigue, Armistead Robinson, Justin Behrend, Ira Berlin, and Steven Hahn, together with the other editors of the volumes of the Freedmen and Southern Society project.Footnote 47

Comparable with the case of the Lower Mississippi Valley, the rebellion staged in Upper Basilicata by the agrarian masses during the Great Brigandage led to the exploited laborers’ invasion of the masserie (landed estates) owned by the region’s proprietors, as Franco Molfese, in particular, has shown in his studies. Since Molfese published his works in the 1960s, the description of the Great Brigandage as a “peasant war” has come under attack and is currently downplayed, if not dismissed altogether by several historians.Footnote 48 However, I believe it is still a valid interpretation, since the record shows that the majority of the “brigands” who formed guerrilla bands were peasants, many of them landless, and their targets were, for the most part, the landowners – particularly the liberal landowners who supported the Italian government – and their estates, together with the National Guard and the Italian army which protected them.Footnote 49 As a result of the scale and intensity of the conflict that opposed peasants and landowners in Basilicata, the region has been at the center of treatments of the Great Brigandage, both in general and also at the local level – most notably with studies by Franco Molfese, Francesco Pietrafesa, Tommaso Pedio, Pierre-Yves Manchon, and Ettore Cinnella.Footnote 50 Thus, by looking at the two parallel and contemporaneous instances of social revolution carried out by the exploited agrarian masses through rebellious activities and either land occupation or invasion in the Lower Mississippi Valley and Upper Basilicata, I have sought to shed further light on the phenomena of slave rebellion and peasant rebellion that occurred in the midst of the inner civil wars that characterized the Confederate South and southern Italy.

The book is organized as follows. The Introduction argues in favor of the essential comparability of the two case studies of inner civil wars in the Confederate South and southern Italy in 1861–5, with regard to both the parallel conflicts between opposite nationalisms and the parallels in the agrarian masses’ rebellious activities. Part I focuses on the parallel resistances to the processes of national consolidation and nation building that occurred in the Confederate States of America and in southern Italy in the period 1860–3. In Chapter 1, I argue that we should see the movement leading to the secession of the Confederate States of America and the southern Italian elite’s support to Italian unification and the Kingdom of Italy, in both cases in 1860–1, as preemptive counterrevolutionary measures. Through these, American slaveholders and southern Italian landowners attempted to create two new nations that protected their interests either by implementing or by embracing processes of nation-building that had a great deal in common with what happened in other regions of the Americas and Europe. In Chapter 2, I investigate the different ways in which the Confederacy and the Italian Kingdom claimed and maintained, or failed to maintain, their legitimacy as new nations; the different processes of nation building and their different outcomes; and, in particular, the inner civil wars fought by Unionist guerrillas within the Confederate South and through Bourbon activities within southern Italy in the period 1861–3. In Chapter 3, I look at the specific case studies of East Tennessee and Northern Terra di Lavoro in 1860–1, first by providing background information on the social and political features of the two regions and on the mixed reactions of their populations to Confederate secession and Italian unification, and then by focusing on particularly significant examples of Unionist and pro-Bourbon guerrilla activities and the Confederate and Italian authorities’ reactions to them. In Chapter 4, I continue the analysis of East Tennessee and Northern Terra di Lavoro in the period 1861–3, by looking specifically at the Confederate and Italian governments’ implementations of repressive measures and at the processes of escalation of the inner civil wars; in both cases, these led to the implementation of extreme military provisions that affected the regions’ civilians in a major way.

Part II focuses specifically on the experiences of the lower strata – African American slaves and southern Italian peasants – arguing that, in both cases, it is possible to say that a social revolution occurred in the two southern countrysides, though with very different characteristics. In Chapter 5, I look in general at the historiography and the historical evidence regarding rebellious activities carried out by the exploited agrarian masses in the Confederate South and southern Italy, particularly in the period 1862–5, and I relate these to other instances of agrarian rebellion in the nineteenth-century Euro-American world. In Chapter 6, I review the historiography and the historical evidence on the crucial issue of land in relation to the agrarian masses in the Confederate South and southern Italy, and I focus specifically on the struggles between masters and both slaves and free African American laborers over land in the American Civil War, and between landowners and peasants in the Great Brigandage. In Chapter 7, I look at agrarian rebellions by focusing specifically on the Lower Mississippi Valley and Upper Basilicata in comparative perspective in the period 1862–3; significantly, this period witnessed an escalation of slave unrest in the Confederate-held areas and freedpeople unrest in the Union-held areas of the Lower Mississippi Valley, and an escalation of brigand activities and peasant unrest in most of Upper Basilicata. In Chapter 8, I look at the continuation of established patterns of agrarian rebellion and unrest, and I relate these to the land issue by analyzing episodes of occupation of plantations by slaves and freedpeople in the Lower Mississippi Valley and invasion of landed estates by brigands in Upper Basilicata. Finally, in the Conclusion, I argue that a comparative perspective between the two inner civil wars highlights the fact that the processes of socioeconomic and political change that the Confederate South and the Italian Mezzogiorno underwent during the American Civil War and Italy’s Great Brigandage had revolutionary potentials that were not fulfilled, and that the legacies of both “unfinished revolutions” determined the subsequent histories of both the agrarian elites and the agrarian masses in the two regions.