Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include maltreatment (e.g. abuse), interpersonal loss (e.g. parental separation), family dysfunction (e.g. inter-parental conflict), and other childhood adversities (e.g. socio-economic hardship) occurring in childhood and adolescence (Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). These experiences are common, with reported estimates between 20% and 70% among adults worldwide (Daníelsdóttir et al., Reference Daníelsdóttir, Aspelund, Shen, Halldorsdottir, Jakobsdóttir, Song, Lu, Kuja-Halkola, Larsson, Fall, Magnusson, Fang, Bergstedt and Valdimarsdóttir2024; Grummitt, Baldwin, Lafoa’i, Keyes, & Barrett, Reference Grummitt, Baldwin, Lafoa’i, Keyes and Barrett2024; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Thiemann, Deneault, Fearon, Racine, Park, Lunney, Dimitropoulos, Jenkins, Williamson and Neville2025; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021; Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). ACEs have been classified into broad categories, such as maltreatment, interpersonal loss, family dysfunction, and others, in a recent umbrella review (Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). Childhood maltreatment, including physical and sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, has been most frequently associated with anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022).

ACEs are non-specific risk factors that confer a 2- to 6-fold increase in the odds of developing any mental disorder in adulthood (Abate et al., Reference Abate, Sendekie, Merchaw, Abebe, Azmeraw, Alamaw, Zemariam, Kitaw, Kassaw, Wodaynew, Kassie, Yilak and Kassa2024; Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). Experiencing multiple ACEs (Merrick, Ford, Ports, & Guinn, Reference Merrick, Ford, Ports and Guinn2018) is associated with higher odds of later mental health problems (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017), with some indications of a ‘dose-effect’ (Daníelsdóttir et al., Reference Daníelsdóttir, Aspelund, Shen, Halldorsdottir, Jakobsdóttir, Song, Lu, Kuja-Halkola, Larsson, Fall, Magnusson, Fang, Bergstedt and Valdimarsdóttir2024). Explanations for such associations include ACEs leading to heightened attention toward threats, and maladaptive schemas triggering negative cognitions, anxious behavior, emotional dysregulation, depressed mood, and paranoia (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Sullivan, Lewis, Zammit, Heron, Horwood, Thomas, Gunnell, Hollis, Wolke and Harrison2011). This indicates that ACEs confer a predisposition to poor outcomes transdiagnostically. Several major mental health conditions appear to have common risk factors and shared treatments in earlier stages (Dalgleish, Black, Johnston, & Bevan, Reference Dalgleish, Black, Johnston and Bevan2020; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Scott, McGorry, Cross, Keshavan, Nelson, Wood, Marwaha, Yung, Scott, Öngür, Conus, Henry and Hickie2020), suggesting that transdiagnostic prevention approaches might have advantages over single-disorder approaches. Furthermore, while previous studies have investigated the associations between ACEs and discrete mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis (Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022), understanding the relationship between ACEs and a pooled transdiagnostic outcome might help overcome the challenge of achieving statistical power to reliably detect low-incidence outcomes (Cuijpers, Reference Cuijpers2003). This approach might also offer public health advantages, as potential interventions for transdiagnostic risk factors might have benefits across many disorders simultaneously.

While existing prospective studies have consistently shown that ACEs increase the odds of mental disorders in adulthood, several studies retrospectively ascertained exposure to ACEs from official court and child protection records (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021; Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). Such methods only included the most severe and/or reported instances and likely underestimated the role of more concealed experiences, such as emotional neglect (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021), which is less likely to receive attention from welfare agencies (Chamberland, Fallon, Black, Nico, & Chabot, Reference Chamberland, Fallon, Black, Nico and Chabot2012). Prospectively collected, self-report data are needed to study the potential impacts of all ACEs.

In such data, investigating factors that moderate the associations between ACEs and mental disorders could identify vulnerable subgroups. Markers of additional vulnerability when being exposed to ACEs have had limited study, in contrast to the literature on protective factors. While prior, predominantly cross-sectional studies have indicated the mediating (Buchanan, Walker, Boden, Mansoor, & Newton-Howes, Reference Buchanan, Walker, Boden, Mansoor and Newton-Howes2023; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Han, Teopiz, McIntyre, Ma and Cao2022) or moderating (Crouch, Radcliff, Strompolis, & Srivastav, Reference Crouch, Radcliff, Strompolis and Srivastav2018) effect of protective factors, such as psychological processes, family support, and ethnicity (Elkins, Kassenboehmer, & Schurer, Reference Elkins, Kassenboehmer and Schurer2017), there is little direct evidence for interaction effects from prospective studies that can guide the identification of youth at higher risk. Clinical risk factors typically assessed by general practitioners and primary care clinicians, such as sex or gender, family history of mental disorders, childhood symptoms, and adolescent personality traits, may be particularly relevant. Examining whether these factors increase the risk of poor mental health outcomes when exposed to ACEs could be used to select participants in preventive intervention trials, and subsequently, for selective prevention. For instance, parental mental disorders might influence children’s mental health trajectories via early exposure to dysfunctional family environments, whereas supportive family environments might mitigate the effects of losses (Adjei et al., Reference Adjei, Schlüter, Melis, Straatmann, Fleming, Wickham, Munford, McGovern, Howard, Kaner, Wolfe and Taylor-Robinson2024; Behere, Basnet, & Campbell, Reference Behere, Basnet and Campbell2017; Kamis, Reference Kamis2021; Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). Females may be more vulnerable to interpersonal abuse and are more likely to develop mental health symptoms (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Montalvo, Creus, Cabezas, Solé, Algora, Moreno, Gutiérrez-Zotes and Labad2016; Herringa et al., Reference Herringa, Birn, Ruttle, Burghy, Stodola, Davidson and Essex2013; Sternberg et al., Reference Sternberg, Lamb, Greenbaum, Cicchetti, Dawud, Cortes, Krispin and Lorey1993). Personality traits measured within the five-factor model, or related markers, such as self-esteem and self-regulation, have also been hypothesized or identified to interact with ACEs to contribute to poorer mental health outcomes, predominantly in cross-sectional studies (Gallardo-Pujol & Pereda, Reference Gallardo-Pujol and Pereda2013; Kushner, Bagby, & Harkness, Reference Kushner, Bagby and Harkness2017; Rogosch & Cicchetti, Reference Rogosch and Cicchetti2004; Vinkers et al., Reference Vinkers, Joëls, Milaneschi, Kahn, Penninx and Boks2014). The development of such personality traits may also be influenced by ACEs and in turn affect the way youth engage with or adapt to ACEs (Mallet, Reference Mallett2022). Finally, lower neurocognitive functioning is associated with early exposure to adversity (Melby et al., Reference Melby, Indredavik, Løhaugen, Brubakk, Skranes and Vik2020), and higher neurocognitive functioning might protect against developing psychopathology (Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Borràs, Solé, Torrent, Garriga, Serra-Navarro, Forte, Montejo, Salgado-Pineda, Montoro, Sánchez-Gistau, Pomarol-Clotet, Ramos-Quiroga, Tortorella, Menculini, Grande, Garcia-Rizo, Martinez-Aran, Bernardo, Pacchiarotti and Verdolini2024). To our knowledge, no study, to date, has examined interactions between these commonly clinically assessed effect modifiers, ACEs, and transdiagnostic mental health outcomes, using prospective data. Prospective studies examining interactions are vital as mental health outcomes including mood states could affect the report of effect modifiers such as personality traits (Hibbert, Reference Hibbert2018).

This study, using the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC; Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser, Henderson, Molloy, Ness, Ring and Davey Smith2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Davey Smith, Henderson, Macleod, Molloy, Ness, Ring, Nelson and Lawlor2013), had two aims. First, to investigate the prospective associations between adverse childhood experiences and transdiagnostic mental health outcomes in young adulthood that are likely to need clinical mental health care. We focused on depressive, anxiety, and psychotic symptoms, operationalized as a pooled transdiagnostic outcome (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023). Second, we examined the role of family history of mental disorder in a first-degree relative, sex at birth, childhood neurocognition, and personality traits in adolescence as potential effect modifiers of the association between ACEs and mental health outcomes in young adulthood.

Method

We used a prospective cohort design, adhering to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (Supplementary Table 1). Informed consent for the use of data collected via questionnaires and clinics was obtained from participants following the recommendations of the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee at the time.

Data source

This study used data from the ALSPAC cohort. Pregnant women resident in Avon, UK with expected dates of delivery between 1st April 1991 and 31st December were invited to take part (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser, Henderson, Molloy, Ness, Ring and Davey Smith2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Davey Smith, Henderson, Macleod, Molloy, Ness, Ring, Nelson and Lawlor2013). The initial number of pregnancies enrolled was 14,541, and 13,988 children were alive at 1 year of age. Children who were unable to join the study at age 1 were invited to participate in the study during adolescence and adulthood bringing the cumulative total to 15,546 participants. A proportion of children, their mothers, and families have been followed since the prenatal period, with recurring measurements at different timepoints throughout the children’s lives (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Davey Smith, Henderson, Macleod, Molloy, Ness, Ring, Nelson and Lawlor2013; Major-Smith et al., Reference Major-Smith, Heron, Fraser, Lawlor, Golding and Northstone2023; Northstone et al., Reference Northstone, Lewcock, Groom, Boyd, Macleod, Timpson and Wells2019). Through self-reported questionnaires, interviews, and clinical data, ALSPAC investigators measured parents and children’s personal experiences, household, and neighborhood environment, health outcomes and other factors throughout childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Approximately 14–56% of the total eligible participants with data on the exposures and outcomes at ages 16, 18, and 24 years formed the analytic sample (Supplementary Figure 1).

The study website contains details of all the data available through a fully searchable data dictionary and variable search tool and reference the following webpage: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/. Please see Supplementary Methods for detailed description of the recruitment.

Exposure

ACEs were assessed via self-report questionnaires. Children began self-reporting their experiences from age 8, before which their mother/mother’s partner completed the questionnaires, recalling events over a 12-month period. Data from these questionnaires were integrated into exposures from birth to age 16 into 19 different ACEs (Supplementary Figure 2; Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling, & Howe, Reference Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling and Howe2018). We focused on the five ACEs linked to maltreatment including physical abuse (defined as ‘adult in family was ever physically cruel toward or hurt the child’), sexual abuse (‘the child was ever sexually abused, forced to perform sexual acts or touch someone in a sexual way’), emotional abuse (‘parent was ever emotionally cruel toward the child or often said hurtful/insulting things to the child’), emotional neglect (‘child always felt excluded, misunderstood or never important to family, parents never asked or never listened when child talked about their free time’), and bullying (‘child was a victim of bullying on a weekly basis’; Houtepen et al., Reference Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling and Howe2018). Rather than broader environmental factors, we chose maltreatment-related ACEs as they primarily stem from interpersonal interactions and have the strongest relationship with mental health outcomes (Fitzgerald & Bishop, Reference Fitzgerald and Bishop2024). While all 19 ACEs could be examined, we limited our examination to maltreatment ACEs as testing many interactions could identify spurious associations from Type I error (Ranganathan, Pramesh, & Buyse, Reference Ranganathan, Pramesh and Buyse2016). Dichotomous responses across multiple timepoints from birth to age 16 were used to derive binary constructs as developed by Houtepen et al. (Reference Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling and Howe2018). We created pooled variables that described ‘any ACE’, ‘cumulative ACE’ (classified as having experienced one, two, or three or more ACEs), and ‘any abuse’, which described physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, consistent with the categorization in the CDC-Kaiser Permanente ACE Study (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, Koss and Marks1998), with details in the Supplementary Methods.

Outcome

Given the strong inter-relationships and shared causal factors among anxiety, depressive, and psychotic symptoms reported in our previous work (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023), we considered a pooled transdiagnostic stage-based outcome including these symptom types during the transitional years of ages 18 and 24. In transdiagnostic staging approaches, Stage 1a represents nonspecific or mild symptoms, Stage 1b suggests subthreshold but clinically significant symptoms, and Stages 2, 3, and 4 suggest full threshold discrete disorders at varying levels of severity and persistence (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Scott, McGorry, Cross, Keshavan, Nelson, Wood, Marwaha, Yung, Scott, Öngür, Conus, Henry and Hickie2020). Our primary outcome was Stage 1b or higher (1b+), representing at least moderate symptoms associated with functional impact. By this stage, young people show specific clinically relevant mental disorder symptoms that signal the need for mental health intervention (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023).

Participant-reported anxiety, depressive, and psychotic symptoms were used to generate the pooled outcome. Briefly, depression and anxiety were assessed using the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R), with Stage 1b + defined as at least a) recurrent or persistent moderate symptoms at ages 18 and 24, or b) severe symptoms with functional impairment at either age 18 or 24 (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023). Psychosis was examined by the Psychosis Like Symptoms Interviews, with Stage 1b + characterized by at least monthly primary psychotic symptoms associated with distress, functional impairment, or help-seeking within the past 6 months at either age 18 or 24. The pooled Stage 1b + outcome was considered present if at least one Stage 1b + outcome was present and considered absent, if symptoms were absent for all three disorders. Please see the Supplementary Methods and our previous report for detailed definition and rationale for this outcome (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023).

While broader transdiagnostic stage outcomes have included manic symptoms, substance use, and externalizing symptoms (Hickie et al., Reference Hickie, Scott, Hermens, Naismith, Guastella, Kaur, Sidis, Whitwell, Glozier, Davenport, Pantelis, Wood and McGorry2013), it may be unwise to pool these in a simple dichotomous outcome (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023), as we have previously argued. Such an outcome could have substantial heterogeneity, which could obscure associations or interaction effects.

Covariates

Potential confounders

We selected confounders a priori, using a Directed Acyclic Graph (Supplementary Figure 3) outlining hypothesized causal pathways. We included four confounders measured during pregnancy (i.e. prior to ACEs), consistent with previous studies investigating the associations between ACEs and mental health outcomes (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021). Confounders included child’s ethnicity, sex at birth, maternal age at delivery, and household social class (indicated by mother’s and partner’s occupational background).

Effect modifiers

We examined the role of sex at birth, first-degree family history of severe mood and psychotic disorders, childhood neurocognition, and adolescent personality traits. These variables have been found to be related to early adversity and mental health outcome, as previously discussed. The child’s sex was determined at birth, dichotomized into female and male. First-degree family history of mental disorders was based on report of parents having experienced severe depression or schizophrenia as reported by parents from birth until children were 8 years of age (or until parents were approximately 35 years of age), ensuring that at least a majority of the risk for depression and psychosis was captured. We included the full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) scores measured by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children at age 8. Personality traits were measured at age 14 using computer-assisted self-assessment using the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg, Mervielde, Deary, De Fruyt and Ostendorf1999), assessing for the ‘Big Five’ personality factors in continuous scores: openness (or intellect vs unconventionality), conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability (or neuroticism). These are further described in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

To account for missing data, we conducted multiple imputation (MI) using multivariate imputation by chained equations. MI models included all analysis variables and auxiliary variables (described in the Supplementary Methods). In our analytic sample, there were approximately 0–20% missing observations for the variables in the primary analyses (Supplementary Table 2), therefore, we generated 20 datasets with data imputed using the ‘mi estimate’ command.

We described sample characteristics using a randomly selected imputed dataset. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to examine the association between each ACE and young adults’ Stage 1b + mental health outcome, adjusting for confounders.

To test for effect modification, we included interaction terms between any abuse, emotional neglect, and bullying and each effect modifier in separate statistical models. We used F-test statistics to test for interaction and obtained stratum-specific odds ratios (ORs) for categorical effect modifiers (i.e. sex and first-degree family history of severe mood and psychotic disorders) and ORs associated with each unit increase in numerical effect modifiers (i.e. childhood neurocognition and adolescent personality traits). The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied to correct for multiple testing (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2018). Additive and multiplicative interactions were examined to quantify the deviation of joint effect from the sum and the product of the individual effects of each exposure and effect modifier (VanderWeele & Knol, Reference VanderWeele and Knol2014). We used the ‘nlcom’ command to calculate the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) to address additive interaction and the ratio of odds ratios (ROR) derived from the multivariable regression coefficients to quantify multiplicative interaction (VanderWeele & Knol, Reference VanderWeele and Knol2014). We described the strength of interaction using VanderWeele’s interaction continuum for interactions between exposures and each categorical effect modifier (VanderWeele, Reference VanderWeele2019). This allows identified interactions to be placed on a rank indicating their strength. A higher rank (numerically lower) indicates a higher strength of association. The model and the ranks are detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Sensitivity and post-hoc analyses: For ease of interpretation, we described effect modification where personality scores were categorized into tertiles (low, normal, high; Supplementary Table 3) and FSIQ scores were categorized into low (the bottom 25%), normal (the middle 50%), and high (the top 25%; Supplementary Table 3), in line with the previous research (Ayers, Gulley, & Verghese, Reference Ayers, Gulley and Verghese2020; Moran, Klinteberg, Batty, & Vågerö, Reference Moran, Klinteberg, Batty and Vågerö2009).

We replicated all main analyses using a combined approach of inverse-probability weighting and multiple imputation (IPW/MI; Seaman, White, Copas, & Li, Reference Seaman, White, Copas and Li2012), with auxiliary variables and confounders measured at birth or in gestation with less than 10% missingness to generate weights for larger missing data blocks, to examine whether the findings were replicated in a larger proportion of the eligible participants.

We replicated our analyses using the complete case sample to check for similarity with imputed findings, and we examined associations between each ACE and each mental disorder outcome (Stage 1b + of depression, anxiety, and psychosis) to identify outliers. We also conducted post-hoc analyses to examine whether excluding each symptom type from the pooled outcome altered the results of the statistically significant (p < .05) multivariable logistic regressions and effect modification tests. Finally, given the possibility that the data could depart from missing at random (MAR) assumptions (Supplementary Table 2), we conducted post-hoc sensitivity analysis for statistically significant effect modification results using the method developed by Carpenter, Kenward, and White (Reference Carpenter, Kenward and White2007)). The overall parameter estimate was computed as a weighted average of the MAR-based estimates, with the weight determined by the coefficient for the association between having the outcome and the likelihood of having complete data for any ACE.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata BE/18.

Results

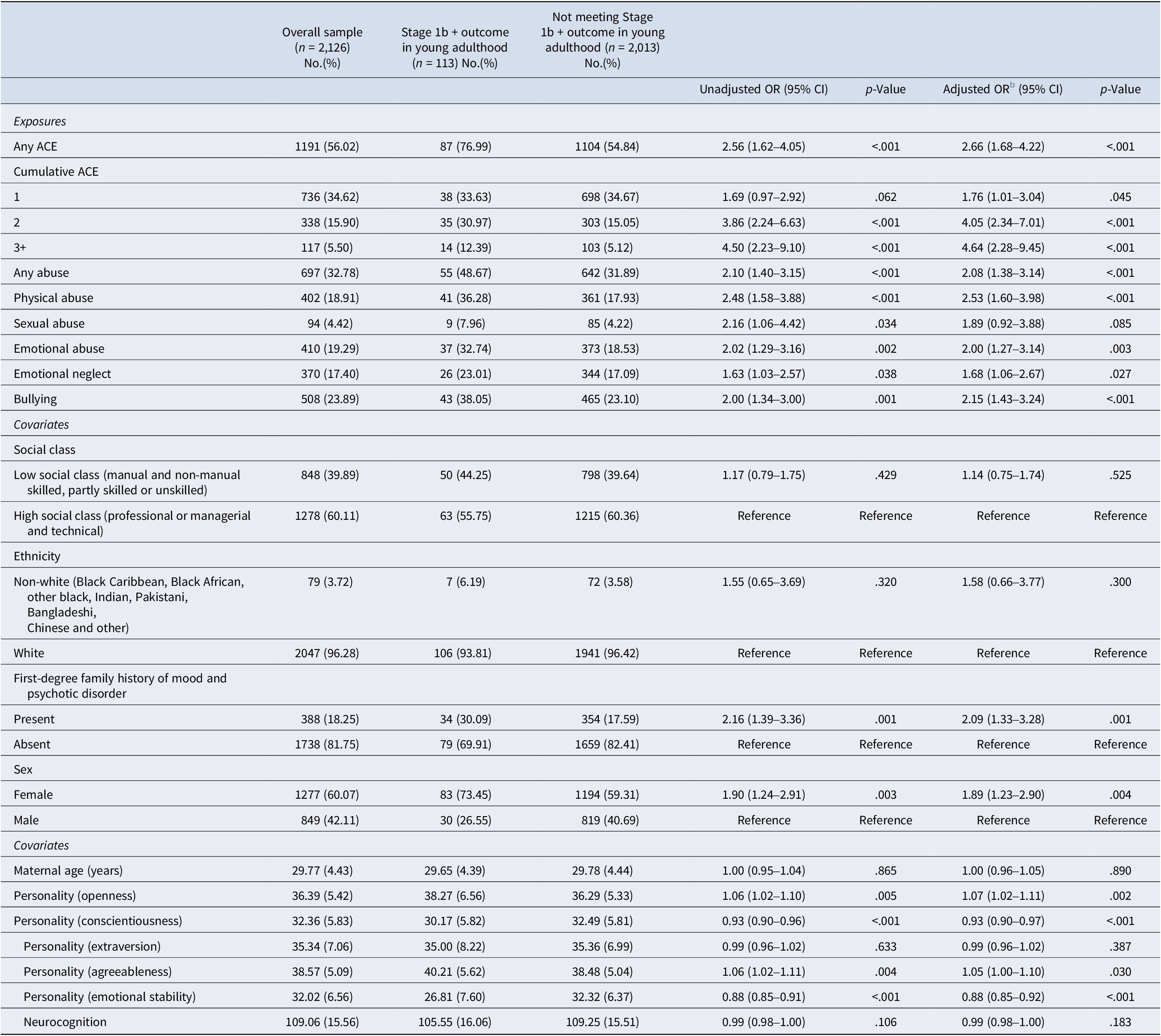

Among 15,645 eligible pregnancies, 2,126 participants had complete data for both the exposure (i.e. any abuse, emotional neglect, and bullying) and the pooled Stage 1b + mental health outcome (Supplementary Figure 1). The complete case sample was impacted by selective attrition with differences in sex, ethnicity, social class, and family history of mental health conditions. In post-hoc analyses using IPW/MI, the weighted sample (N = 7,815) was similar to the initial eligible sample in most characteristics except for lower social class (Supplementary Table 2). In the complete case sample, most participants were female (60.07%), white (96.28%), from high social class (60.11%), and 56.02% participants had experienced at least one ACE (Table 1). 10–20% of observations of data were missing in our primary analyses (Table 1 & Supplementary Table 2), and all ACEs were independent of covariates (Supplementary Table 4). The prevalence of Stage 1b + outcome was 5.32% (n = 113).

Table 1. Prevalence of each variable as well as multivariable logistic regressions for the association between each exposure or covariate and the Stage 1b + mental health outcomea

a Using a randomly selected MI dataset (n = 2,126).

b Confounders include maternal age, social class, ethnic group, and sex.

Having experienced any ACE led to a 2.66-fold increase in the odds of the Stage 1b + outcome (95% CI = 1.68–4.22, p < .001, Table 1). Among different ACEs, physical abuse had the strongest association with the outcome (OR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.60–3.98, p < .001), followed by bullying (OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.43–3.24, p < .001), emotional abuse (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.27–3.14, p = .003), and emotional neglect (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.06–2.67, p = .027). There was no evidence of an association between the Stage 1b + outcome and sexual abuse (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 0.92–3.88). A ‘dose-effect’ was evident, such that people who had experienced three or more ACEs (OR = 4.46, 95% CI = 2.28–9.45, p < .001) or two ACEs (OR = 4.05, 95% CI = 2.34–7.01, p < .001) had higher odds of the Stage 1b + outcome compared to those experiencing one type of ACE (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.01–3.04, p = .045). Associations between different ACEs and Stage 1b + of individual disorders indicated similar patterns (Supplementary Table 5).

Effect modification

First-degree family history of mental disorders and childhood neurocognition

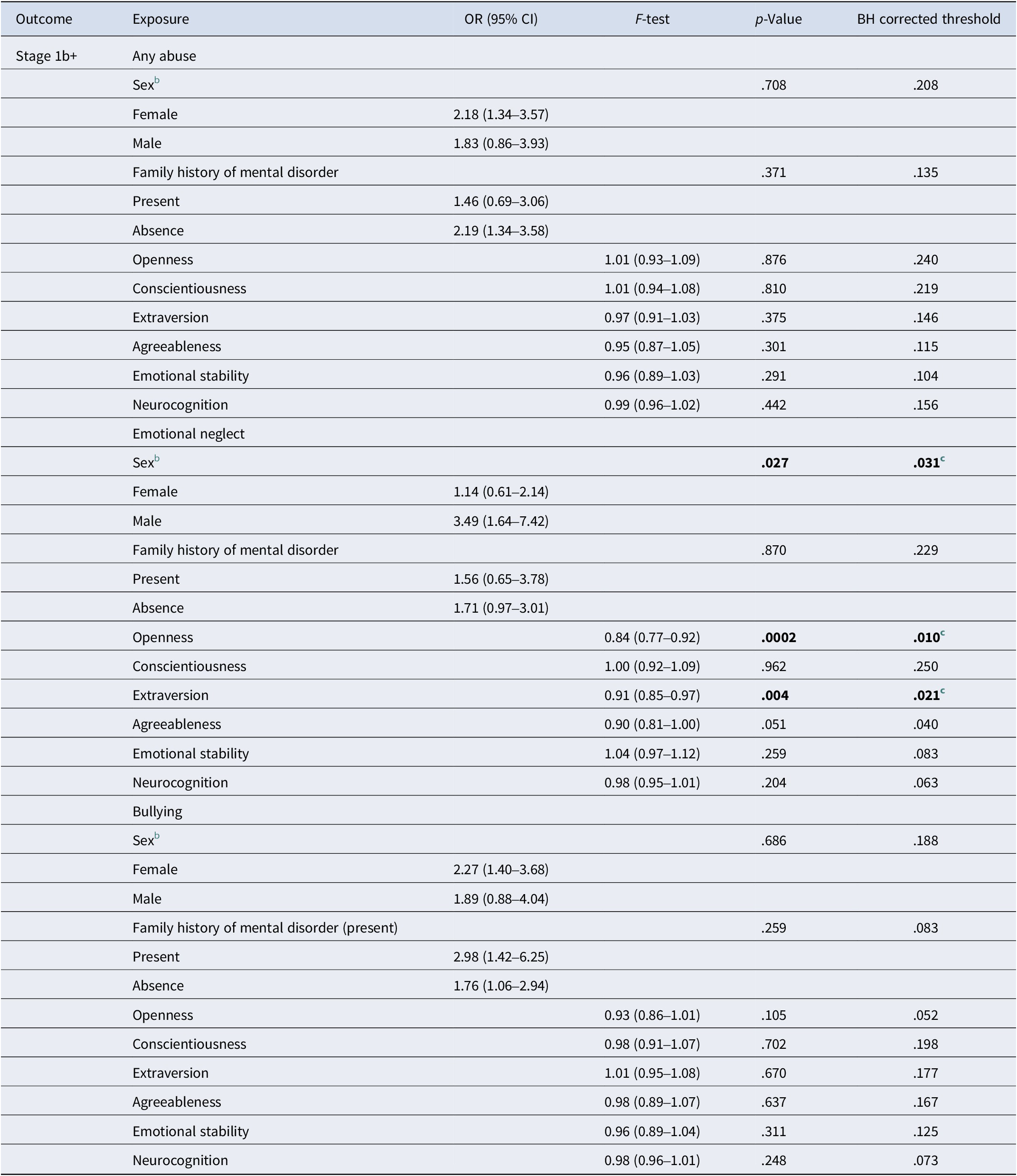

There was no evidence of effect modification by first-degree family history of mental disorders or childhood neurocognition on the association between the Stage 1b + mental health outcome and any abuse, emotional neglect, or bullying (p-values for F-tests for interaction >.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Logistic regression models between the exposures and the outcome across levels of each effect modifiera

a Confounders include maternal age, social class, ethnic group, and sex except in note b below.

b Confounders include maternal age, social class, and ethnic group.

c p-value of the F-test is smaller than the critical Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) corrected threshold.

The bolded text indicates that they are below the conventional statistical significance threshold of 0.05. They are in bold to aid readability and highlight significant findings.

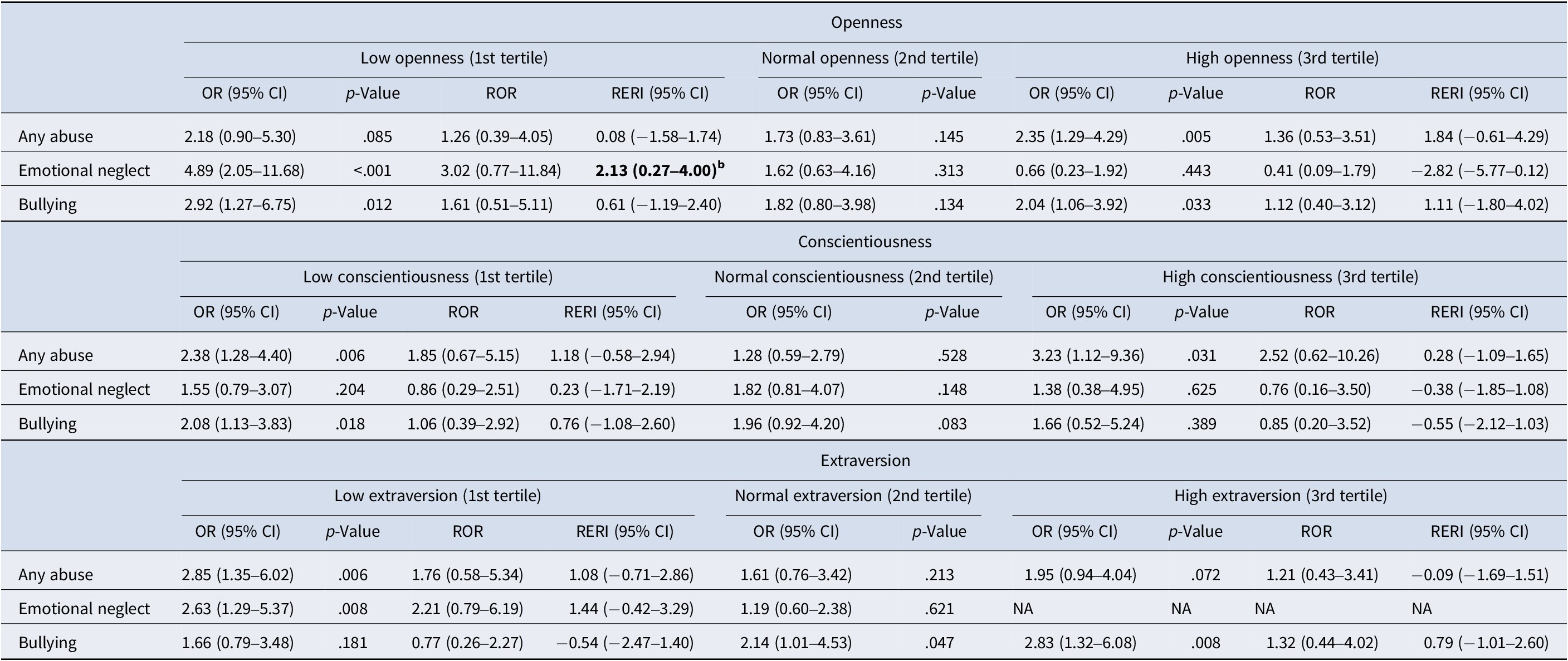

Sex at birth

There was evidence for sex modifying the effect of emotional neglect on the Stage 1b + outcomes (p = .027, threshold = 0.031, Table 2). The association was weak among females (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.61–2.14) but was stronger and statistically significant among males (OR = 3.49, 95% CI = 1.64–7.42, p = .001; Table 3). The negative multiplicative (ROR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.12–0.88, p < .05) and non-significant additive interaction between emotional neglect and female sex (Table 3) was ranked fourth in VanderWeele’s interaction continuum (2019) for two causative exposures. This indicates a weak interaction.

Table 3. Logistic regression models between the exposures and the outcome across levels of the dichotomous effect modifiers including sex and first-degree family history of mental disorders

Note: ROR, ratio of odds ratios; RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction.

a Confounders include maternal age, social class, ethnic group, and sex are adjusted for.

b Confounders include maternal age, social class and ethnic group are adjusted for.

c p-value<.05.

The bolded text indicates that they are below the conventional statistical significance threshold of 0.05. They are in bold to aid readability and highlight significant findings.

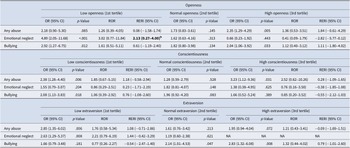

Table 4. Logistic regression models between the exposures and the outcome across levels of the trichotomous effect modifiers, including personality traits and neurocognitiona

The bolded text indicates that they are below the conventional statistical significance threshold of 0.05. They are in bold to aid readability and highlight significant findings.

Table 5. Logistic regression models between the exposures and the outcome across levels of the trichotomous effect modifiers, including personality traits and neurocognition (continued)a

Note: RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction; ROR, ratio of odds ratios.

a Confounders include maternal age, social class, ethnic group, and sex.

b p-value <.05.

NA, not applicable as model did not converge due to low cell numbers.

Personality measured during adolescence

There was strong evidence for effect modification by openness on the association between emotional neglect and the Stage 1b + outcome (p < .001, Benjamini–Hochberg corrected threshold = 0.010, Table 2). For each score increase in openness, there was a 0.84-fold decrease in the odds of experiencing the outcome associated with emotional neglect (95% CI = 0.77–0.92, p < 0.05, Table 2). Post-hoc analysis indicated that compared to those with normal openness (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 0.63–4.16, p = .313), the association between the outcome and emotional neglect was stronger and statistically significant among those with low openness (OR = 4.89, 95% CI = 2.05–11.68, p < .001; Table 4). The effect of low openness was ranked second on the interaction continuum for two causative exposures (VanderWeele, Reference VanderWeele2019), suggesting a strong interaction.

There was also evidence for effect modification by extraversion on the association between emotional neglect and the Stage 1b + outcome (95% CI = 0.85–0.97, p = .004, Benjamini–Hochberg corrected threshold = .021, Table 2). For each score increase in extraversion, there was a 0.91-fold decrease in the odds of experiencing the Stage 1b + outcome. Post-hoc analysis indicated that those with low extraversion had a higher risk of the Stage 1b + outcome associated with emotional neglect (OR = 2.63, 95% CI 1.29–5.37, p = 0.08) while those with normal extraversion did not (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.60–2.38, p = .621; Table 3). The model did not converge for high extraversion.

Sensitivity and post-hoc analysis

Using IPW/MI to extend our findings to roughly half the eligible sample (N = 7,815), the interaction findings for sex and extraversion remained significant, but the impact of low openness on outcomes was attenuated. In sensitivity and post-hoc analyses using a delta-adjusted method for departures from MAR assumptions, findings for the association between ACEs and the Stage 1b + outcome (Supplementary Table 6) and for effect modification by sex, openness and extraversion on the impact of emotional neglect (Supplementary Tables 7–8b) were similar to that with the analytic sample. Results using complete case data were similar to the findings using MI data (Supplementary Tables 5–8). Post-hoc sensitivity analyses excluding each mental health symptom type from the transdiagnostic outcome indicated a similar pattern of interactions (Supplementary Tables 9–10b).

Discussion

In this prospective study, we confirmed that ACEs were associated with an increased risk of poor transdiagnostic mental health outcomes in young adulthood. We also identified that youth who experienced emotional neglect prior to age 16 were more likely to experience poorer mental health outcomes in young adulthood if they were male or had lower self-reported openness or extraversion in adolescence. Lower extraversion and male sex remained relevant in roughly half the total eligible sample in weighted analyses.

Our results contribute to a growing body of literature identifying ACEs as both a common and major contributor to mental ill-health. In our sample, approximately 60% of participants had experienced at least one ACE, consistent with previous studies (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021). Experiencing ACEs increased the odds of negative mental health outcomes, with evidence of greater association with multiple types of ACEs. While broadly consistent with existing findings, the magnitude of the association (ORs between 1 and 3) in our results was slightly lower than some existing studies (ORs between 2 and 6; Daníelsdóttir et al., Reference Daníelsdóttir, Aspelund, Shen, Halldorsdottir, Jakobsdóttir, Song, Lu, Kuja-Halkola, Larsson, Fall, Magnusson, Fang, Bergstedt and Valdimarsdóttir2024; Grummitt et al., Reference Grummitt, Baldwin, Lafoa’i, Keyes and Barrett2024; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021; Sahle et al., Reference Sahle, Reavley, Li, Morgan, Yap, Reupert and Jorm2022). This might be explained by different appraisals of ACEs observed between retrospective and prospective studies (Baldwin, Coleman, Francis, & Danese, Reference Baldwin, Coleman, Francis and Danese2024).

We found that sex modifies the effect of emotional neglect, with males showing increased vulnerability to mental ill health in young adulthood. The use of different coping techniques might explain the higher resilience shown by females in response to emotional neglect (Brown, Fite, Stone, Richey, & Bortolato, Reference Brown, Fite, Stone, Richey and Bortolato2018; McGloin & Widom, Reference McGloin and Widom2001). Females tend to use emotion-focused strategies and to seek social support, whereas males tend to employ problem-focused strategies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fite, Stone, Richey and Bortolato2018). While both problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies reduced mental disorder symptoms, the latter led to a faster decrease, and such improvements were particularly pronounced among females (Fluharty, Bu, Steptoe, & Fancourt, Reference Fluharty, Bu, Steptoe and Fancourt2021). Future studies could consider coping styles and other mechanisms such as self-regulation (Rollins & Crandall, Reference Rollins and Crandall2021) or self-esteem (Kim, Lee, & Park, Reference Kim, Lee and Park2022) in conferring resilience to specific ACEs, considering between-sex differences.

There was also evidence that higher extraversion, and in a sub-sample higher openness, in adolescence might be protective against the impact of emotional neglect. This reflects the known association between resilience and these traits (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, Reference Campbell-Sills, Cohan and Stein2006; Nakaya, Oshio, & Kaneko, Reference Nakaya, Oshio and Kaneko2006; Oshio, Taku, Hirano, & Saeed, Reference Oshio, Taku, Hirano and Saeed2018). Resilience depends on positive interpretation of adversity (Hähnchen, Reference Hähnchen2022). When facing negative emotions and maladaptive thoughts induced by adversity, extraverted individuals cultivate resilience through cognitive restructuring, as they tend to focus on solving the problem itself rather than the associated negative affect (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, Reference Connor-Smith and Flachsbart2007). Extraversion facets, such as expressiveness and positive emotionality (Burgin et al., Reference Burgin, Brown, Royal, Silvia, Barrantes-Vidal and Kwapil2012; Riggio & Riggio, Reference Riggio and Riggio2002), also support resilience, mitigating the harm associated with ACEs (Hähnchen, Reference Hähnchen2022). Overall, we identified evidence for interaction between several effect modifiers with emotional neglect but none with other types of abuse. This could be explained by abuse being a more potent risk factor indicated by the magnitude of association from our data and from prior literature (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, Reference Connor-Smith and Flachsbart2007; Gardner, Thomas, & Erskine, Reference Gardner, Thomas and Erskine2019; Li, D’Arcy, & Meng, Reference Li, D’Arcy and Meng2016; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fang, Gong, Cui, Meng, Xiao, He, Shen and Luo2017; Taillieu, Brownridge, Sareen, & Afifi, Reference Taillieu, Brownridge, Sareen and Afifi2016). It suggests that emotional neglect might have specific pathways to mental health problems.

The threat-deprivation model (McLaughlin Sheridan, & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014) provides some explanation. Emotional neglect and passive maltreatment, which constitutes deprivation, differs from experiences that involve actual (i.e. physical and sexual abuse, and bullying) or implied harm (i.e. emotional abuse) leading to the perception of threat. Threat exposure is believed to directly and strongly influence emotion regulation and reaction to potential danger through fear learning and conditioning, whereas deprivation could preferentially affect cognition through lack of experiences and pruning of under-stimulated synaptic connections (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014; Sheridan, Peverill, Finn, & McLaughlin, Reference Sheridan, Peverill, Finn and McLaughlin2017). Prior studies have indicated that deprivation-related ACEs had a weaker impact on internalizing symptoms (e.g. anxiety and depression; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Gracey, Shaffer, Ebert, Kuhn, Watson, Gruhn, Vreeland, Siciliano, Dickey, Lawson, Broll, Cole and Compas2021; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Islam, Nahar Lata, Nahar, Zakir Hossin and Uddin2024) but higher risk of executive functioning difficulties (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Policelli, Li, Dharamsi, Hu, Sheridan, McLaughlin and Wade2021). When facing a relatively weak effect, higher openness and extraversion could lead to youth seeking novel experiences and social integration (Yu, Zhao, Li, Zhang, & Li, Reference Yu, Zhao, Li, Zhang and Li2021), while those with lower openness and extraversion might be unable to do so, potentially worsening the impact of such ACEs over time. Conversely, early-life threat exposure could cause harm irrespective of personality traits, as threats could cause strong impacts on social–emotional processing and difficulty disengaging from negative experiences (McLaughlin & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin and Lambert2017). This signals the need to develop different interventions targeting children exposed to deprivation (Sheridan & McLaughlin, Reference Sheridan and McLaughlin2016).

It should also be noted that exposure to ACEs may have a reciprocal relationship with the development of openness and extraversion (Fosse & Holen, Reference Fosse and Holen2007; Grusnick, Garacci, Eiler, Williams, & Egede, Reference Grusnick, Garacci, Eiler, Williams and Egede2020; Pos et al., Reference Pos, Boyette, Meijer, Koeter, Krabbendam and de Haan2016), yet such traits could prompt individuals’ exposure to additional ACEs (Mallett, Reference Mallett2022) through their engagement with new environments (Shiner & Caspi, Reference Shiner and Caspi2003). Therefore, caution should be taken when interpreting the interplay between ACEs and personality, which may contribute to the observed associations. While openness and extraversion are malleable in childhood and early adolescence (Branje, van Lieshout, & Gerris, Reference Branje, van Lieshout and Gerris2007; Tetzner, Becker, & Bihler, Reference Tetzner, Becker and Bihler2023), they are associated with minimal change from mid adolescence to young adulthood (ages 15–24; Elkins et al., Reference Elkins, Kassenboehmer and Schurer2017; Vecchione, Alessandri, Barbaranelli, & Caprara, Reference Vecchione, Alessandri, Barbaranelli and Caprara2012). This suggests that such traits could be used to select youth at higher risk of additional harm in the face of emotional neglect.

We did not find evidence for effect modification by first-degree family history of mental disorder. While these children might be predisposed to adverse mental health outcomes due to genetic risks and the impact of impaired parenting (Burke, Reference Burke2003; Mattejat & Remschmidt, Reference Mattejat and Remschmidt2008; van Santvoort Hosman, van Doesum & Janssens, Reference Van Santvoort, Hosman, Doesum and Janssens2014), some develop protective compensatory mechanisms and resilience through coping (Pölkki Ervast, & Huupponen Reference Pölkki, Ervast and Huupponen2004), or by caring for their parent with a mental illness (McDougall, O’Connor, & Howell, Reference McDougall, O’Connor and Howell2018; van der Mijl & Vingerhoets, Reference van der Mijl and Vingerhoets2017). Variable responses to maltreatment (Mattejat & Remschmidt, Reference Mattejat and Remschmidt2008) could have led to the lack of significant interactions.

We did not find that neurocognition moderated the impact of ACEs. This could be because the differences between participants regarding their cognitive processes may be explained better by their engagement with intellectual experiences (openness) rather than intellectual functioning (Ziegler, Cengia, Mussel, & Gerstorf, Reference Ziegler, Cengia, Mussel and Gerstorf2015). While openness encourages the pursuit of intellectual experience, crystalized intelligence fosters positive experience of successful problem-solving, subsequently enhancing motivation and skills for further growth (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Cengia, Mussel and Gerstorf2015).

This study’s primary limitation is the smaller proportion of the eligible sample due to longitudinal attrition, which is common among birth cohort studies. This selective attrition might reduce the generalizability of our findings to non-white individuals and those with parents from non-professional or managerial backgrounds. However, additional analyses in a weighted sample including half the total eligible participants identified similar findings with respect to sex and extraversion, suggesting acceptable generalizability. The finding regarding openness needs confirmation in prospective studies with less attrition. Second, we could not examine the possibility that early life ACEs could influence the personality traits studied in this investigation due to our use of time-collapsed ACE variables. However, this allowed us to comprehensively examine the role of ACEs, which are likely to have a cumulative impact on adult mental health outcomes. Third, we acknowledge that children might engage in help-seeking behavior such as undergoing counselling in response to ACEs, which would subsequently affect the outcome. However, we did not include this in our analysis as ALSPAC only captured help-seeking for specific difficulties such as self-harm. There were also challenges in temporality with young people potentially receiving counselling at several points in adolescence or young adulthood. Additionally, we utilized sex at birth, which limited our capacity to investigate the role of self-determined gender on the risks associated with ACEs. This was, however, necessary to inform the confounding effects of sex on early-life exposures. Finally, evidence of statistical interaction must be interpreted with caution, given the high possibility of detecting a range of interactions within the sufficient component causal model of complex mental disorders (Zammit, Lewis, Dalman, & Allebeck, Reference Zammit, Lewis, Dalman and Allebeck2010). Hence, we corrected for multiple comparisons and interpreted findings on the interaction continuum, highlighting the modifying effect of sex and extraversion on the association between emotional neglect and the Stage 1b + outcome as the most promising finding. Our findings are also likely robust as we used prospectively collected data from birth to adulthood. We ensured temporality between ACEs and young adults’ mental health outcomes, supporting conclusions regarding their causative role in the development of mental disorder. ALSPAC data collection utilized widely used and validated clinical questionnaires to identify outcomes, confounders, and effect modifiers. The use of a transdiagnostic approach allowed us to identify previously unrecognized impacts of ACEs on subgroups, such as males and those with certain personality characteristics. Finally, our results were robust to sensitivity analysis excluding individual symptom types from our transdiagnostic outcome.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest the need for future research to identify why some children might have differential risk, aiming to identify malleable risk factors. Our results, as well as prior data, suggest that all children exposed to, or at-risk of, maltreatment should be offered preventive interventions such as parent training. In addition, there is a need to develop public health interventions addressing emotional neglect, potentially targeting subgroups or malleable mechanisms.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725000893.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses.

Funding statement

The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref: 217065/Z/19/Z) and the University of Bristol provided core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors and Yufan Chen and Aswin Ratheesh will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). This research was specifically funded by the MRC (MR/M006727/1, G0701503/85179). M.B. is supported by a NHMRC Leadership 3 Investigator grant (GNT2017131). Z.A. is supported by an Australian Research Council Early Career Industry Fellowship (IE230100561). S.M. is supported by the NIHR Midlands Translational Research Centre and the Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.