Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25 results

Chapter 4 - Diptych and Virtual Diptych

- from Middle Proem: Dead Languages and Living Ones

-

- Book:

- Latin Poetry Across Languages

- Published online:

- 19 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 125-160

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Passages to Italy

- from Middle Proem: Dead Languages and Living Ones

-

- Book:

- Latin Poetry Across Languages

- Published online:

- 19 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 161-205

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Latin Poetry Across Languages

- Adventures in Allusion, Translation and Classical Tradition

-

- Published online:

- 19 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026

Chapter 3 - Wollstonecraft and Godwin, Loving by the Book

-

- Book:

- Reading Sympathy in Romantic Literature

- Published online:

- 05 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 101-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- The Joy of Love in the Middle Ages

- Published online:

- 20 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 December 2025, pp 169-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Critic

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Introduction to Samuel Johnson

- Published online:

- 07 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 78-95

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Biographer

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Introduction to Samuel Johnson

- Published online:

- 07 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 114-131

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - The Later 1650s

-

- Book:

- Milton's Ireland

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024, pp 145-161

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1823: A Year in the Afterlife of Shakespeare and Milton

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Public Humanities / Volume 1 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 November 2024, e22

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Puritan Democracy

-

- Book:

- Democracy, Theatre and Performance

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024, pp 63-89

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Milton and National Exceptionalism

- from Part II - Writing the Nation

-

-

- Book:

- The Nation in British Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 20 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 10 August 2023, pp 137-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - ‘Varieties too Regular for Chance’

- from Part II - Times

-

-

- Book:

- A History of English Georgic Writing

- Published online:

- 01 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 140-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Scattered Bones, Martyrs, Materiality, and Memory in Drayton and Milton

- from Part II - Grounding the Remembrance of the Dead

-

-

- Book:

- Memory and Mortality in Renaissance England

- Published online:

- 06 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2022, pp 123-140

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

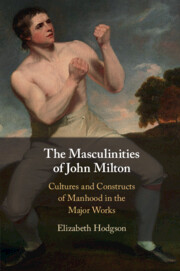

Postlude

-

- Book:

- The Masculinities of John Milton

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022, pp 174-189

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Masculinities of John Milton

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022, pp 1-26

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Masculinities of John Milton

- Cultures and Constructs of Manhood in the Major Works

-

- Published online:

- 01 September 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022

Chapter 8 - William Blake as leitourgos

- from Part III - Culture’s Theological Mode of the Sacred

-

-

- Book:

- Sacred Modes of Being in a Postsecular World

- Published online:

- 07 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 164-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Epic Hero and Epic Fable

-

- Book:

- Explorations in Latin Literature

- Published online:

- 05 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 19 August 2021, pp 62-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - First Similes in Epic

-

- Book:

- Explorations in Latin Literature

- Published online:

- 05 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 19 August 2021, pp 286-321

-

- Chapter

- Export citation