Refine search

Actions for selected content:

621 results

Chapter 3 - Thomas and Solomon

-

- Book:

- Dante's Political Philosophy

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2026, pp 99-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Three Problems in Heidegger’s Plato

- from Part 1 - Plato and Marburg

-

- Book:

- Heidegger and German Platonism

- Published online:

- 16 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 60-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Romantic Prophets

- from Part II - Romancing the Nation

-

- Book:

- Charismatic Nations

- Published online:

- 14 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 67-82

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Plato and the Poets and Plato as Poet

- from Part II - Post-Heideggerian Platonism

-

- Book:

- Heidegger and German Platonism

- Published online:

- 16 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 161-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Latin Poetry Across Languages

- Published online:

- 19 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Fall of the Tang

- Gao Pian's Trials of Allegiance

-

- Published online:

- 19 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026

7 - Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

- from Part I - Post-Medieval Arthurs in Literature and Culture

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Arthurian Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 12 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 166-187

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Keats’s Interreading

-

- Book:

- Reading Sympathy in Romantic Literature

- Published online:

- 05 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 156-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - Derek Walcott as Pragmatist Strong Poet

- from Part III - Methods

-

-

- Book:

- William James and Literary Studies

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 361-386

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Hunt, Byron, and Dante’s Paolo and Francesca

-

- Book:

- Reading Sympathy in Romantic Literature

- Published online:

- 05 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 39-67

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - William James, Attention, and Post-1945 American Poetry

- from Part II - Influence

-

-

- Book:

- William James and Literary Studies

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 208-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Teaching Style

- from Part I - Style

-

-

- Book:

- William James and Literary Studies

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 19-31

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Utopian Articulations in Experimental British Poetry

- from Part III - From Crisis to Hope: Utopian Aesthetics

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Utopian Literature and Culture since 1945

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 February 2026, pp 178-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

De la souffrance où nous joint l’infini: Raïssa Maritain’s Poetic Theodicy and Metz’s Suffering Unto God

-

- Journal:

- New Blackfriars ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2026, pp. 1-9

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Women's Poetry from Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, 1400–1800: An Anthology

-

- Published online:

- 05 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

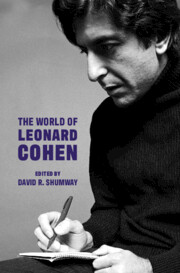

The World of Leonard Cohen

-

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

Chapter 2 - The Poetry and Prose

- from Part I - Creative Life

-

-

- Book:

- The World of Leonard Cohen

- Published online:

- 29 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 29-46

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Section 3 - Wales 1400–1660

- from Part I - 1400–1660

-

- Book:

- Women's Poetry from Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, 1400–1800: An Anthology

- Published online:

- 05 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 134-192

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Section 4 - Ireland 1660–1800

- from Part II - 1660–1800

-

- Book:

- Women's Poetry from Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, 1400–1800: An Anthology

- Published online:

- 05 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 195-349

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

First Collection

- from Letters for the Advancement of Humanity

-

- Book:

- Johann Gottfried Herder: Letters for the Advancement of Humanity

- Published online:

- 13 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 3-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation