Refine search

Actions for selected content:

8 results

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 1-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Imperial Examinations and Confucianism

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 163-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Emergence and Evolution of the Institutional Genes of the Chinese Imperial System

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 122-162

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Institutions and Institutional Genes

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 59-90

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 658-724

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Property Rights as a Form of Institutional Gene

-

- Book:

- Institutional Genes

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025, pp 91-121

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

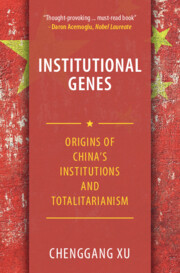

Institutional Genes

- Origins of China's Institutions and Totalitarianism

-

- Published online:

- 03 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 26 June 2025

15 - The Origin of China’s Communist Institutions

- from Part II - 1950 to the Present

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Economic History of China

- Published online:

- 07 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 February 2022, pp 531-564

-

- Chapter

- Export citation