‘Imagisme is not Impressionism.’1 Ezra Pound’s distinction – in an essay entitled, confusingly, ‘Vorticism’ (1914) – is typically dogmatic. Pound’s critics have tended to take him at his word, concentrating on the line of ‘artistic descent viâ Picasso and Kandinsky; viâ cubism and expressionism’ traced out in his official manifestoes for imagism (and later vorticism, the panartistic grouping by which imagism came to be absorbed), which is then said to represent a break from the nineteenth-century milieu out of which impressionist art emerged, and to be more truly congruent with the radical anti-mimesis of Kandinsky, the cubist abstractions of Picasso and Braque, and the new geometric sculpture of Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (GB, p. 82).2 If the force of Pound’s judgement is intended to emphasise the difference between the two terms, however, the fact that such a distinction seemed necessary to him might cause one to wonder whether the issue was so unambiguous, since it could seem to imply that imagism risked being mistaken for impressionism (which is here implicitly conceived as both a visual and a verbal form) or that they were similar enough to have been confused already. Indeed, a likeness is signalled by the tangled grammar of Pound’s qualification to his initial distinction – ‘though one borrows, or could borrow, much from the impressionist method of presentation’ (GB, p. 85) – which indicates an actual debt, before retreating into a more provisional mode, as if to correct or moderate itself. Either way, the pressure of that word, ‘impressionism’, is conspicuous, suggesting that the difference between the two terms mattered to Pound and that he felt it needed to be clarified. In fact, while he is usually supposed to have had only ill-informed or haphazard things to say about imagism’s precursor, one of the styles with which Pound’s early writings about art and poetry are most frequently and deliberately engaged is impressionism.3 The emphasis of these engagements is constantly altering, so that impressionism comes to represent two contradictory styles, but impressionism is nonetheless the central term towards which Pound’s writings are repeatedly drawn, and with which they are in productive tension. As I will be arguing, it is partly out of this tension that Pound’s concept of the Image evolves.

Perhaps the most prominent example of Pound’s attempts to differentiate between imagism and impressionism follows his well-known account (also in ‘Vorticism’) of the genesis of his famous imagist poem ‘In a Station of the Metro’ (1912). Pound recalls stepping onto the platform at La Concorde some time in 1911, and being met by a vision of faces lit up momentarily in the darkness: ‘[I] saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another, and then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful woman’ (GB, p. 87). For months he struggled to find words ‘as lovely as that sudden emotion’, which presented itself to the memory only as ‘little splotches’ and ‘arrangements in colour’, as if too delicate for the rigid semantic prescriptions of the written word (p. 87). Pound’s solution was a type of poem in which ‘painting or sculpture seems as it were “just coming over into speech”’:

The ‘one image poem’ is a form of super-position, that is to say, it is one idea set on top of another. I found it useful in getting out of the impasse in which I had been left by my metro emotion. I wrote a thirty-line poem, and destroyed it because it was what we call work ‘of second intensity’. Six months later I made a poem half that length; a year later I made the following hokku-like sentence:

I dare say it is meaningless unless one has drifted into a certain vein of thought. In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective.

Pound concludes, ‘This particular sort of consciousness has not been identified with impressionist art. I think it is worthy of attention’ (p. 89). The relationship between the pronouns and the subjects of those final sentences is significantly unclear – what is ‘worthy of attention’ here could be a psychological state or an art form – and this ambiguity is multiplied by the double meaning of ‘identify’, which can mean both ‘recognise’ and ‘associate’. In turn, these ambiguities raise the question: is Pound suggesting that the sort of consciousness described here has not been identified by impressionist artists, who have not found it worthy of attention? Or is he arguing that this kind of consciousness has not been considered in relation to that which is the subject of impressionist art, and that a comparison of the two would be worth examining? Or, less plausibly, is he suggesting that there is a positive affinity between the two that has not yet been recognised?

The tone of Pound?s opening remarks would suggest the first, but certain similarities between impressionism and imagism are betrayed by the anecdote’s Parisian locale, oriental blossom and subterranean flâneurie. And while it may be merely coincidental that Place de la Concorde also provides the setting for Edgar Degas’s famous painting of faces silhouetted against the foliaged borders of the Tuileries Gardens, the essay’s frame of reference does tend to connect Pound’s Image to nineteenth-century painting rather than demonstrate ‘its inner relation to certain modern paintings and sculpture’ (p. 82).4 If Pound claims in his essay to have ‘found little that was new to me’ on encountering Kandinsky’s 1911 essay Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), this is because he was already familiar with the ‘arrangements of colour’ made famous by Whistler (p. 87). Indeed, of the artists Pound connects with his own poetry, it is not Kandinsky or Picasso but Whistler who emerges as the root influence: elsewhere in the essay Pound credits Whistler’s campaign against ‘extraneous matter’ with initiating a wider ‘movement against rhetoric’ by Ford (‘the shepherd of English Impressionist writers’) and the English poets of ‘the “Nineties”’ (particularly in the lyric ‘Impressions’ and ‘Pastels’ of Symons and Wilde), who, in turn, had paved the way for the eloquent minimalism of the Image (p. 85).5 Such filial relations are compounded by a more fundamental epistemological correspondence. According to Pound’s essay, the Image aims to ‘record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective’ – or, as he put it a year earlier in ‘A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste’ (1913), it is ‘that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time’ (LE, p. 4). In other words, an Image is a verbal portrait of that vague perceptual zone in which stimuli are ‘transformed’ into traces of themselves. The emphasis is on a ‘darting’ movement – presumably of the mind, despite Pound’s curious suggestion that an object might transform itself – rather than the things being darted between. In Hugh Kenner’s influential argument, ‘[t]he imagist [is] not concerned with getting down the general look of the thing’, but rather with distilling ‘the process of cognition itself’.6 But this would also seem to be the interest of the impressionist, or at least the area of concern implied by the impression. Like the Image, the impression makes an obscure metaphorical unity (or ‘complex’) of the two moments in which the mind receives and reads an imprint.7 In this sense, the whole logic of ‘super-position’, with its emphasis on the interstices between perceptual moments, seems to imply a structural analogue for the impression’s layering of sensation and sense, emotion and intellect, the tactility of lived experience and the hallucinations of memory.

This is not to suggest that there is no difference between imagism and impressionism, but simply to notice affinities which run counter to Pound’s apparent suggestion that one has ‘identified’ a form of consciousness alien to the other, and to register how these affinities amplify the connotation of likeness which haunts the word ‘identify’ itself. A nagging sense of similarity or kinship may account for the stringency of the essay’s culminating distinction:

The logical end of impressionist art is the cinematograph. The state of mind of the impressionist tends to become cinematographical. Or, to put it another way, the cinematograph does away with the need of a lot of impressionist art.

There are two opposed ways of thinking of a man: firstly, you may think of him as that toward which perception moves, as the toy of circumstance, as the plastic substance receiving impressions; secondly, you may think of him as directing a certain fluid force against circumstance, as conceiving instead of merely reflecting and observing. [The] two camps always exist. In the ’eighties there were symbolists opposed to impressionists, now you have vorticism, which is, roughly speaking, expressionism, neo-cubism, and imagism gathered together in one camp and futurism in the other. Futurism is descended from impressionism. It is, in so far as it is an art movement, a kind of accelerated impressionism. It is a spreading, or surface art, as opposed to vorticism, which is intensive.

The thrust of Pound’s initial comparison is that the cinema is artless because the camera is brainlessly impartial. His related criticism of the impressionist ‘state of mind’ also hinges on the notion that it is too passive, too diffuse.8 This argument underwrites a basic (and implicitly gendered) tension between two ways of seeing at the heart of ‘Vorticism’, in which Pound opposes reflective or ‘surface’ art to active or ‘intensive’ art. The opposition is conceived as a permanent polarity, but Pound’s illustrative examples (Pater, Whistler, Maupassant) and, indeed, the polarity itself have a distinctly nineteenth-century flavour. His ‘creative’ faculty has its roots in the sublimating power of the imagination, as it is conceived within romantic aesthetics; while his ‘mimetic’ art form absorbs the mirror-like reflectivity denigrated by fin de siècle poetics and also, in the phrase ‘plastic substance’, an echo of the metaphor most closely associated with impressionism: that of the tabula rasa.9 In other words, the metaphorical range of Pound’s opposition is historically specific and precisely calibrated to separate the Image from impressionist art forms, which are then implied to be insufficiently active or concentrated.

The passage would be one example of how, as Daniel Albright has noted, Pound distinguished imagism ‘strongly, even irritably [from] dying literary movements’.10 Elsewhere the irritability with ‘surface’ or ‘mimetic’ art will be amplified, as in the essay Pound contributed to the first volume of Blast, in which he argues that ‘Impressionism, Futurism, which is only an accelerated sort of Impressionism, DENY the vortex. They are the CORPSES of VORTICES.’11 But if, as he suggests in the same essay, it is still the case that ‘the primary pigment of poetry is the IMAGE’, then Pound’s distinctions jar against his first prescription for poetic practice: ‘Direct treatment of the “thing”, whether subjective or objective’.12 As Douglas Mao suggests, the statement ‘simply leaves no doubt that the Image is at bottom presumptively mimetic’.13 The language of ‘things’ – what Pound called a ‘hard’ language, ‘as much like granite as it can be’ – seems to lend itself to the treatment of objects, to the extent that ‘the inclusion of “objective” things became one of the hallmarks of Pound’s kind of poetry, in part because it seemed extraordinarily difficult [to] conform to the imagist aesthetic of hardness without turning to images of hard objects’.14 As Mao observes, by enshrining ‘discerning perception and accurate transcription as the foundations of literary value’, the founding tenets of imagism risked it resembling ‘yet another variety of insufficiently virile empiricism’.15 This danger accounts for Pound’s awkward suggestion – in another dependent clause, as if trying to reroute his initial meaning – that ‘things’ might be subjective as well as objective; but the attempt at clarification only multiplies the ambiguity. It is not clear what mimesis (or ‘direct treatment’) would entail in the case of a subjective ‘thing’ (such as an emotion or mood); nor is it apparent how poems addressing interior subjects avoid the ‘emotional slither’ that the aesthetic of hardness is supposed to counteract.16 The water is muddied further by Pound’s insistent association of slither and ‘muzziness’ with impressionist painting, which would seem to contradict the passive reflectivity implied by his descriptions of impressionism in ‘Vorticism’ and, thus, to house two opposed flaws within one noun.17

Out of Pound’s comments on impressionism and imagism, twinned divisions emerge. On the one hand, the epistemological basis of the Image – its ‘complex’ relation of the ‘outward and objective’ to the ‘inward and subjective’ – is ambiguous in a way that splits imagism in two, leaving it vulnerable to its own predicates. On the other, this ambiguity seems to revolve around a parallel division within Pound’s conception of impressionism, which he sees by turns as excessively subjective (‘muzzy’, ‘emotional’) and too placidly objective (‘surface’, ‘mimetic’). These ambiguities are mutually sustaining: if the tensions internal to the Image have obstructed attempts to define what it is, they have also frustrated attempts to say what it is not, so that both have been subject to conflicting interpretations. Most commonly, confusion has arisen from an absorption of Pound’s language of photographic mimesis and an acceptance that impressionism is slavishly ‘grounded in the senses, and the simple representation of atmosphere’.18 Impressionism is then held responsible for a ‘pictorialist impasse’ that mired a whole generation of poets, spawning a range of opposed values – ‘intellectual energy’, ‘force’, ‘effort’ – which are said to have enabled Pound to ‘break [into] some realm beyond the mood or the impression’.19 Versions of this argument are numerous. It underlies notions of impressionist ‘acquiescence’, which then serves as a foil for the ‘intensity’ of the Image.20 It appears frequently in the effort to separate Pound’s ‘architectonic’ imagism from the frangible art-products of the fin de siècle – those ‘precious impressions demanded by an effete age’s mimeticism’; those ‘playthings of external reality’ which, ‘unlike true art, lack the power of transformation’.21 And it is there, too, in the notion that impressionism is too languid or diffuse, too ‘prosing’, to have had more than ‘an accidental connection’ with Pound’s ‘short, sharp psychic images’.22 Arguments of this kind tend to yield versions of the Image that are non-visual, or occupied primarily with the invisible and affective.23 Nearly as frequently, though, Pound’s talk of slither and muzziness has led critics to interpret impressionism in the opposite way, so that rather than being blandly representational, it represents a form of emotional profusion in which the outlines of objects are blurred.24 Looked at from this perspective, impressionism is marred by its infidelity to appearances, being the expression of an ‘impulse [to] obliterate or at least transmogrify the object’.25 It is opposed, in turn, by a version of imagism which foregrounds its direct treatment of external reality:

Impressionism evoked very different atmospheres from those sought by the Imagists. Imagist poems aimed to flash images directly onto the mind, to produce what was essentially a surprise effect. Vision or contact are never direct in Impressionist work[.] The rain falls in Impressionist painting as it does in the poems of Verlaine.26

After the impressionists have drenched the visual field in sentiment, it is the job of the imagist, on this view, to mop up the emotional residue. Such accounts stress ‘the pictorial intensity, the thereness, the specificity, the solidity of the thing’ as it is rendered in the imagist poem.27 Against the subjective haze and soft focus associated with impressionism, imagism means clarity, hardness, objectivity.

As we will see, Pound himself would characterise impressionism in both ways at different times. Such characterisations are partial, both in the sense that they seem under pressure to rescue the Image from association with a rival or precursor and in the sense that they reflect only one aspect of impressionism itself. One effect of this partiality has been to camouflage certain conceptual and stylistic similarities between the two forms. Another has been to disguise Pound’s dependence on impressionism as an opposed term against which to define his own poetry. The combined result has been to obscure the nature of the Image itself. That is to say, the tendency to simplify impressionism – to concentrate only on some of the flaws Pound identifies in it – has disguised how the Image itself is always shifting in tandem with its rival term, such that it often resembles versions of the impression it has previously been said to counteract. Taking a fuller view reveals the extent to which Pound’s engagement with impressionist styles helped him to formulate his own poetic principles. It also brings into clearer focus how the impression’s capacity to carry multiple, sometimes contradictory meanings produces a parallel ambiguity within the Image itself, which can seem to be at once a product of dissent from impressionism and a perfect incarnation of its central metaphor. Imagism might then be seen not as impressionism’s opposite but as a mirror-image of its range of significances: a poetics whose own instability results from Pound’s attempt to withdraw simultaneously from two contrasting visions of its rival form.

Pound’s divided response to impressionism is evident in his earliest manuscripts, which consist mostly of unpublished reviews and fragments. By 1900, North America was the most important market in the world for French impressionist art. In turn, impressionism had become the dominant style in American painting. Pound’s first works of art criticism respond to exhibitions featuring impressionist art, which is often the main focus of his critical remarks. The manuscripts are characterised especially by a disdain for a certain kind of impressionist artwork – usually by painters, like Claude Monet or Mary Cassatt, who participated in the impressionist exhibitions in Paris – which is said to be inappropriately materialist, in the sense of being either ‘photographic’ (too invested in raw, unfiltered sense data) or merely decorative. Yet they also show Pound articulating his early ideas about poetic style through analogy with artists, like Whistler, who were often associated with the French painters but seemed, in Pound’s view, to represent more positive values.

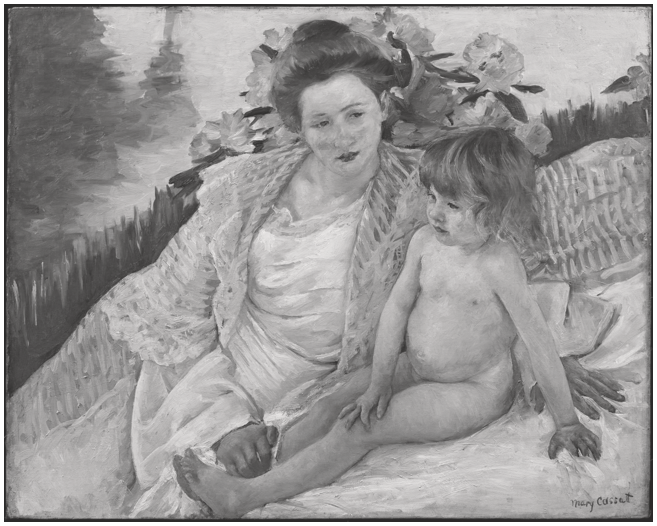

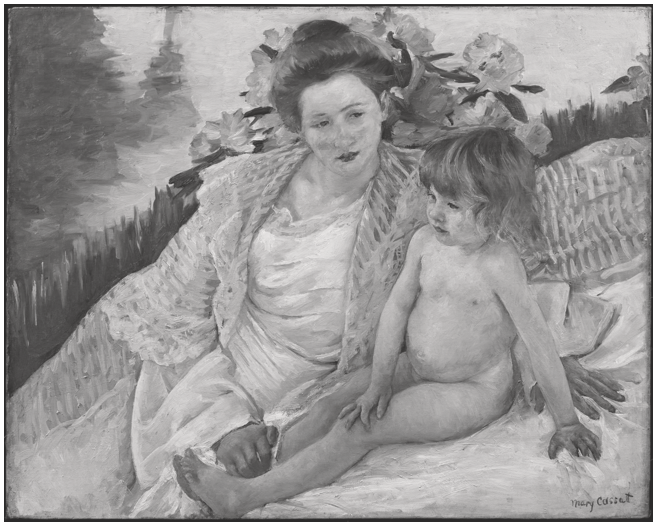

The earliest extant piece of art criticism authored by Pound is an unpublished review of exhibitions held in Philadelphia in the autumn of 1906.28 The centrepiece of the essay is a critique of Mary Cassatt’s painting The Sun Bath (1901, Figure 4.1), which was on display at the Art Club. Pound compares the painting’s ‘harmony’ and ‘pictoreal idiocy [sic]’ to ‘certain chintxz curtains a misguided relative sent me in undergraduate days’, claiming not to have hung the curtains, ‘as I did not want my windows broken with greater frequency than usual’.29 The disharmony of Cassatt’s painting is then adduced as evidence for a wider argument about the relationship of art to certain kinds of mimesis, at the heart of which is Pound’s feeling that ‘[t]he function of the painter is [not] to rival the cemera [sic] in exactness of reproduction of line and mass’.30 Pound’s wariness of photographic ‘reproduction’, with its implications of passivity, commercialism (‘chintxz’) and lack of design (‘pictoreal idiocy’), foreshadows the characterisations of impressionism we find in his later essay on ‘Vorticism’. What is curious, however, is that the substance and language of Pound’s criticism derive from Whistler, who was not only the archetype of the new commercial artist, but also, like Cassatt, closely associated with the French impressionist painters. In another untitled typescript written contemporaneously with his review of Cassatt, Pound instructs, ‘Do not let a professor of English refer you to Ruskin’s Modern Painters [until] you have read the First part of Whistler’s “Gentle Art of Making Enemies”.’31 The first part of The Gentle Art comprises an essay entitled ‘The Red Rag’ (1878), in which Whistler made a distinction (discussed in Chapter 1) between ‘surface’ painting and art which goes ‘beyond’ this: ‘The imitator is a poor kind of creature. If the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be the photographer. It is for the artist to do something beyond this.’32 These would be the terms in which Whistler characterised his own impressions, just as they would underpin his wider definitions of ‘pictorial art’: ‘Painting [is] the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of colour.’33

Figure 4.1 Mary Cassatt, The Sun Bath (after the Bath) (1901), Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo, Japan.

There is an ambiguity here, perhaps even a contradiction – a painting of sight alone might seem vulnerable to Whistler’s own dismissals of ‘surface’ (which can itself have a positive connotation in his writings) – yet in employing this argument to criticise Cassatt, Pound is expressing a preference not about the impression per se, but rather about two distinct kinds of vision which the impression could seem to imply: one which is participatory and active, another which is passively imitative.34 The resulting opposition – of creative projection against photographic reception – is fundamental to all Pound’s early writings. In a further untitled typescript dated ‘July 31 07’, Pound expresses a preference for Whistler’s brand of non-imitative art in terms of a painting which carries its ‘message’ through ‘color alone’ rather than ‘thru accidental chances of subject’, suggesting that paint should be understood as having ‘a separate existence above mere human passion [as] Arthur Symons has said for music’.35 Shortly prior to the composition of Pound’s typescripts, Symons published an essay about Whistler in his Studies in Seven Arts (1906) which Pound described as ‘the finest thing’ written about the artist (GB, p. 122). In a neighbouring discussion of Whistler’s painting in the wider context of nineteenth-century art, Symons pre-empts Pound in distinguishing between two kinds of impression. The first of these he associates with the French painters, particularly Monet, and describes as a ‘shorthand note, which the reporter has not even troubled to copy out’; it ‘reduce[s] painting to a kind of science, the science of disimpassioned technique’ (SSA, p. 43).36 The second is what Symons (borrowing a phrase from Browning) calls the ‘instant made eternity’. Its exemplary exponent is Whistler, who ‘goes clean through outward things to their essence’ (SSA, p. 49).

Symons’s phraseology here is significant. It points forward to Pound’s later definition of the Image as the record of a moment ‘when a thing outward and objective [darts] into a thing inward and subjective’. It also brings out the ambiguity intrinsic to the impression itself, which could suggest both photographic representation and creative illumination. But this opposition also has a more immediate resonance. As Pound’s appraisals of Cassatt illustrate, the opposition of ‘eternal’ to ‘disimpassioned’ instants is already there in his earliest prose writings, where it is mapped onto the same painters discussed by Symons. In another typescript of 1907, Pound complains, ‘I continualy hear the modern discople [sic] of Monet sneer that the old fellows are very much over estimated’, while praising Whistler for ‘lead[ing] us deeper into the mystery and wonder of gods [sic] own colouring’.37 Crucially, it provides a logic and motif for his first poems. ‘For Italico Brass’ (1908) is exemplary in its opposition of moments of emotional luminosity to the shallow impressions of the French painters:

In its description of a temperament which perceives gondolas returning ‘from death’s isle’ only as patterns of light, Pound’s poem frames Monet’s interest in optical science and light effects as evidence of pathological detachment, which is then juxtaposed against the gravity of the speaker’s own perceptions.38 Elsewhere, Pound credits Whistler with a depth and intensity which elude the French painters. In a letter to his mother of 1909, he supposes that ‘the artist is the maker of an ornament or a key’, putting Whistler in the second grouping: ‘when you leave the pictures you see beauty in mists, shadows, a hundred places where you never dreamed of seeing it before’.39 In the poems, too, Whistlerian atmospheres gather about special moments of revelation, as in ‘Nel Biancheggiar’ (1908), which heralds a twilit vision of the poet’s beloved with a symphony in blue and white (‘Blue-grey, and white, and white-of-rose, / The flowers of the West’s fore-dawn unclose’; CEP, p. 72).

The opposition being set up here foreshadows Pound’s later pronouncements about art and poetry, and would be the first significant instance of art and poetry themselves being joined in his thought. The distinction between ornament and key in particular becomes increasingly important to Pound. In a later essay about Constantin Brancusi (1921), he will describe the sculptor as having discovered ‘master-keys to the world of form’, opposing Brancusi’s metallic ovoids to the ‘idiotic ornamentation’ which fills museum ‘junk-shops’ (LE, p. 443); just as in his literary criticism he will distinguish between ‘interpretative metaphor, or image, as diametrically opposed to untrue, or ornamental, metaphor’.40 It will also be crucial to his prescriptions for the Image itself: ‘Use no superfluous word, no adjective which does not reveal something’; ‘Use either no ornament or good ornament’ (LE, pp. 4–5). But Pound’s reference to ‘lyric’ indicates that the distinction was already integral to his poetic vision some time before imagism. In a 1908 letter about his use of ‘the short so-called dramatic lyric’ to William Carlos Williams, Pound remarked:

I catch the character I happen to be interested in at the moment he interests me, usually a moment of song, self-analysis, or sudden understanding or revelation. And the rest of play would bore me and presumably the reader. I paint my man as I conceive him. Et voilà tout!

The resemblance between the Image as a fragmentary record of ‘sudden emotion’ and moments of sudden understanding evoked by outline is striking. It is conspicuous, too, that the argument here is made through analogy with painting, and that its emphasis should land (as in ‘Vorticism’) on the moment of conception rather than the moment of sight, as though to protect the lyric instant Pound is describing from association with passive ocular vision. It illustrates how the opposition being sketched out in Pound’s earliest writings – of the creative, participatory, suggestive (not photographic) to the passively received, superfluous and ornamental – not only prefigures his later distinctions between imagist intensity and impressionist docility, but seems in fact to have emerged from a tension within impressionism itself.

Elements of Pound’s early attraction to revelatory moments passed into his notion of the ‘Luminous Detail’, a concept trialled in the lectures he delivered at the Regent Street Polytechnic between 1908 and 1909, before being officially unveiled in a series of articles published in the New Age under the title ‘I Gather the Limbs of Osiris’ (1911–12). The Luminous Detail – ‘swift and easy of transmission’, giving ‘sudden insight’ – is a clear descendant of the kind of impression that Pound had found in Symons and Whistler (PP, I, p. 44). It marks his ongoing attraction to an aesthetics of effulgent instants and survives in his stipulation that the Image must engender a ‘sense of freedom from time limits and space limits; [a] sense of sudden growth’ (LE, p. 4 ). Yet what sticks out immediately is the stylistic gulf separating the chiselled definition of Pound’s later verse from the ‘hyper-aesthesia’ (as he called it) of the poems he was writing when he arrived in London, with their ‘honey words and flower kisses’, their ‘dew of sweet half-truths / Fallen on the grass of old quaint love-tales’ (‘The Summons’, CEP, p. 262).41 As late as 1911, the primary mode of the poems is libidinous melodrama punctuated by moments of unwitting bathos, as in the flat opening note sounded by ‘Canzon: To Be Sung beneath a Window’, which begins ‘Heart mine, art mine?’ (CEP, p. 136), or the clanging rhymes of ‘Madrigale’ (‘the spun gold above her, / Ah, what a petal those bent sheaths discover’; CEP, p. 147). These poems may focus on significant moments – moments which ‘[b]reak down the four-square walls of standing time’ (‘Und Drang’, CEP, p. 171) – but they bear little resemblance to the imagist style that Pound would shortly adopt.

In August of 1911, Pound travelled to Giessen to stay with Ford (who was then attempting, unsuccessfully, to obtain a divorce by taking German nationality). As the editor of the English Review, Ford had helped Pound to get his first poems into print; while in Giessen, Pound took the opportunity to present the older writer with a copy of his recently published Canzoni. On leafing through the collection, Ford – so the story goes – slumped from his chair to the floor with groans of uncontrollable laughter.42 Pound recounts the incident in his ‘Ford Madox (Hueffer) Ford; Obit’ (1939):

he felt the errors of contemporary style to the point of rolling (physically, and if you look at it as a mere superficial snob, ridiculously) on the floor of his temporary quarters in Giessen when my third volume displayed me trapped, fly-papered, gummed and strapped down in a jejune provincial effort to learn, mehercule, the stilted language that then passed for ‘good English’ in the arthritic milieu that held control of the respected British critical circles, Newbolt, the backwash of Lionel Johnson, Fred Manning, the Quarterlies and the rest of ’em.

And that roll saved me at least two years, perhaps more. It sent me back to my own proper effort, namely, toward using the living tongue (with younger men after me), though none of us has found a more natural language than Ford did.43

As Peter Robinson has suggested, Ford’s roll might be the inaugural event in the history of practical criticism.44 It also marks a critical juncture in the history of modern poetry, in so far as Ford is credited here with ushering in a style that would characterise Pound’s mature oeuvre and a major strand of modernist verse. What is rarely noticed, however, is that this seminal moment coincides with a significant reversal in Pound’s thinking about impressionism. We have already observed that Ford had begun by 1909 to describe ‘natural’ or ‘living’ verse forms in terms of impressionism, which he conceived as a functional tonic to certain kinds of poetic self-indulgence:

You won’t have any vine-leaves in your poor old hair; you won’t just dash your quill into an inexhaustible ink-well and pour out fine frenzies. No, you will be just the skilled workman doing his job with drill or chisel or mallet.

Ford’s emphasis falls on processes of controlled excision: the removal of surplusage as opposed to the ‘pouring out’ of unshaped emotion; precise definition as an antidote to the Pre-Raphaelite idea ‘that Poetry is a matter of mists hiding, of glamours confusing the outlines of things’; clarity and intelligibility as curatives for the notion that words are ‘instruments for exciting blurred emotions’.45 Impressionism, in this usage, denotes a programme of verbal hygiene and refocused vision. Commentary was banished: ‘Never comment: state.’46 Perceptions were to be rendered simply, without comment, leaving only the ‘impression as hard and definite as a tin-tack’ (‘On Impressionism’, CWF, p. 39).

For a poet who had just published a collection of canzoni, Ford’s impressionist programme – particularly his impatience with verse which ‘deals in a derivative manner with mediaeval emotions’ – was antipathetic (‘Modern Poetry’, CA, p. 187). Pound’s obituary brushes over the distress, but the trauma of that meeting in Giessen was registered in his letters, in which he complained to his mother that he disagreed with Ford ‘diametrically’ on everything, ‘art, religion, politics’.47 Whether because he sensed their validity or because sales of Canzoni were poor, however, in the latter parts of 1911 and early 1912 Pound began to vigorously promote the poetic values Ford had urged on him.48 In an essay entitled ‘Prologomena’ (sic) (1912) there is a new insistence that the ‘proper and perfect symbol is the natural object’ and a reframing of his formative interests to accord with this emphasis on perceptual clarity, as when he claims to find a ‘precision which I miss in the Victorians’ in the art of Dante and Cavalcanti, whose ‘testimon[ies]’, he suggests, are ‘of the eyewitness’ (LE, p. 11).There is a doubling back here. A certain kind of ‘eyewitness’ was something Pound had associated with impressionism, often in the unfavourable sense of being merely ‘mimetic’. After his trip to Giessen, however, it signifies something clear-sighted and direct. Like Ford, he begins to interpret impressionism not as a form of suggestive haze but as a liberation into clarity and light. Thus, the nineteenth century now struck Pound as ‘a rather blurry, messy sort of a period, a rather sentimentalistic, mannerish sort of a period’ (LE, p. 11). By contrast, focused in the beam of the impressionist consciousness, objects would appear in their starkest form, undistorted by sentiment. Following Ford, Pound began to place a premium on clarity and ascesis, on cutting away superfluities to leave only the poem’s tautest outlines:

As to Twentieth century poetry [sic], and the poetry which I expect to see written during the next decade or so, it will, I think, move against poppy-cock, it will be harder and saner, [it] will not try to seem forcible by rhetorical din, and luxurious riot. We will have fewer painted adjectives impeding the shock and stroke of it. At least for myself, I want it so, austere, direct, free from emotional slither.

The poetics outlined here is lapidary, economical and impersonal, as though the poem should resemble sculpted rock or cut diamond.

Such pronouncements indicate how Ford’s vision of impressionism as a form of descriptive precision and objective statement weaned Pound off what he had already recognised as the ‘crepuscular’ atmosphere of his own early poems (see ‘Against the Crepuscular Spirit in Modern Poetry’, CEP, p. 97). Pound had absorbed this cloudiness in part from Rossetti and Swinburne, but the major influence came from the hazy symbolist effects of Yeats’s The Wind among the Reeds, which provided Pound with poetic correlatives for Whistler’s nocturnal fogs (a repurposing not without irony, given Yeats’s hostility towards impressionism). Now Pound began to divide his daily routine, seeing ‘Ford in the afternoons and Yeats in the evenings’, the casual irony of the former counterbalancing the gnostic mistiness of the latter.49 He would contrast Ford’s precision with the dream-dimmed ambience of Yeats’s early collections in a famous passage from ‘Status Rerum’, published in January 1913:

Mr. Yeats has been subjective; believes in the glamour and associations which hang near the words. ‘Works of art beget works of art’. He has much in common with the French symbolists. Mr. Hueffer [Ford] believes in an exact rendering of things. He would strip words of all ‘association’ for the sake of getting a precise meaning. He professes to prefer prose to verse. You would find his origins in Gautier or in Flaubert. He is objective.

Ford’s emphasis on ‘exact rendering’ passed directly into the first wave of imagist aesthetics. As Pound remembered in ‘Vorticism’, ‘the “Imagisme” of 1912 to ’14 set out “to bring poetry up to the level of prose’ (GB, p. 83). It was an attempt at translating into verse the precise statement that Ford had found in Flaubert and Maupassant. The earliest statements of imagist doctrine are along Fordian lines: ‘[i]n the spring or early summer of 1912’, Pound remembered in ‘A Retrospect’, he, Richard Aldington and H.D. had fixed on the foundational tenets of imagism, which were ‘direct treatment of the thing’, ‘presentation’ (LE, p. 3). In ‘A Few Don’ts’, published in March 1913, Pound was urging ‘the unspeakably difficult art of good prose’ on his contemporaries (LE, p. 5); in the fifth instalment of ‘The Approach to Paris’, published in October of 1913, he allied himself to ‘the “prose tradition” of poetry[.] It means constatation of fact. It presents. It does not comment’ (PP, I, p. 181).

It is hardly novel to point out that Ford’s vision of impressionism helped to shape the imagist doctrines of direct treatment and limpid presentation.50 But it is interesting to observe that these doctrines show Pound coming to adopt a set of aesthetic values of which he had previously been critical, and which he had associated with an impoverished art form, particularly the soulless colour-science of Monet and the French impressionists. Indeed, by the time he came to write ‘The Serious Artist’ in the latter part of 1913, Pound’s interpretations of Ford’s poetic dicta increasingly resembled the scientific aesthetics he had attributed to Monet five years earlier. When he suggests that ‘poets should acquire the graces of prose’, he also calls for an art that contains ‘precise psychology’ (PP, I, p. 202). Good art is now ‘art that is most precise’; bad art is ‘inaccurate art’. More broadly, ‘[t]he serious artist is scientific in that he presents the image of his desire, of his hate, of his indifference as precisely that, as precisely the image of his own desire, hate or indifference’ (PP, I, pp. 187–8). Such statements are markedly different in tone from the vague profundity of ‘For Italico Brass’ and the troubadour imitations of Canzoni, yet they represent a persistence of the binary which underpins Pound’s first pieces of art criticism. The difference is that here the emphasis has been reversed, so that the qualities of suggestion and evocation which inspire Pound’s earliest poems and manuscripts are now tempered by aesthetic values they had previously outranked. His early writings seem in this sense to play out a dialectic internal to impressionist aesthetics, which might imply both sharp outline and effects of haze, both raw fact and spiritual ambience. That dialectic will continue to shape Pound’s thought, but the immediate impact of Ford’s prescriptions was to push Pound towards the crisp expression and precise definition customarily associated with imagism, and which he would urge on those ‘contemporary poets who escape from all the difficulties of the infinitely difficult art of good prose by pouring themselves into loose verses’ (GB, p. 83). It is on the basis of this early period of Pound’s imagist activity that the Image has been understood as a form of gleaming particulate hardness, the sharply defined product of a stern semantic discipline in which the outlines of things are focused and clarified.

To the extent that Ford’s interpretation of impressionism helped to inculcate in Pound certain stylistic values – clarity, definite outline, accurate presentation – the ramifications of that trip to Giessen would be far-reaching.51 Again, this will not be news to readers of Ford or Pound; but what complicates things is the fact that concurrently with his adoption of certain impressionist values from Ford – indeed, partly because of these values – Pound launches a new critique of an opposed set of aesthetic characteristics (softness, sentimentality, inexactitude) which he also associates with impressionism. In other words, he rounds back on himself in two ways. First, Pound’s adoption of objective hardness and scientific precision as aesthetic criteria involves a reversal of his earlier attitudes, in that the kind of impressionism he associates with Ford is in one sense congruent with the passionless empiricism he had previously attributed to Monet. But in addition to – or because of – this reversal, Pound’s attitudes towards art and poetry also undergo a series of major revisions. Most significantly, he up-ends his critiques of Monet, who, rather than being too concerned with superficies, is said to have engendered an emotional ‘looseness’ in an entire generation of poets. There is continuity and change: impressionism remains the term through which Pound defines his arguments about poetry and painting and, as in the early manuscripts, one kind of impressionism corrects another; but now each term has been turned on its head, so that the impressionist contradiction expressed in Pound’s first responses to art appears in inverted form.

The clearest example of this pattern of inversion appears in an essay of 1914 about James Joyce, in which Pound remarks ‘I admire impressionist writers’, but qualifies this by separating them into two groups: ‘Impressionism has [two] meanings, or perhaps I had better say, the word “impressionism” gives two different “impressions”’ (LE, p. 399). The first of these belongs to the ‘impressionist writers [whose] founder was Flaubert’ and who ‘deal in exact presentation’; ‘they are perhaps the most clarifying and they have been perhaps the most beneficial force in modern writing’ (p. 399). This was the impressionist tradition into which Pound placed Ford, and his description gives a sense of the high esteem in which he now held the older writer. The second belongs to a group of ‘verse writers who founded themselves not upon anybody’s writing but upon the pictures of Monet’:

Every movement in painting picks up a few writers who try to imitate in words what someone has done in paint. Thus one writer saw a picture by Monet and talked of ‘pink pigs blossoming on a hillside’, and a later writer talked of ‘slate-blue’ hair and ‘raspberry-coloured flanks’.

These ‘impressionists’ who write in imitation of Monet’s softness instead of writing in imitation of Flaubert’s definiteness, are a bore, a grimy, or perhaps I should say, a rosy, floribund bore.

The impressionist poet of this type inflicts compound inexactitudes, seeking after effects which belong to a different medium, and doing so in imitation of a visual style which is now said to be chronically imprecise: ‘soft’ in the sense of being inexact, so that haystacks are seen in grey-purple (as in Monet’s pictures of Giverny) and the realities of rural poverty are transformed into a bucolic bourgeois fantasy. On this increasingly widespread view, impressionism was a form of unconstrained emotionality. It resembles the Fontainebleau ‘miasma’ that Storer, for instance, had begun to describe in his art columns for the Commentator: ‘a dreamy-creamy thing, a mélange of subtle colours’ which was ‘nearly always wet’, both in the ‘wet-on-wet’ technique associated with plein air painting and in its emotional incontinence.52 Imitated in verse, what results is not an example of painting ‘just coming over into speech’, but a ‘luxurious riot’ with anaemic verbal relatives (‘slate-blue’, ‘raspberry-coloured’) of a visual form which, far from being passive and emotionless, is now said to be emotionally distortive, melting things into swirls of the wrong shade.

As is often the case in Pound’s criticism, the swagger of the prose masks a remarkably subtle distinction. Contemporary theorists of literary impressionism often distinguish between two kinds of impressionist writing: between the lyrics that poets such as Symons and Wilde were writing as the nineteenth century drew to a close, and the prose tradition from which Conrad and Ford drew inspiration as the twentieth century got underway.53 Such distinctions usually repeat the judgement Pound makes here, echoing his verdict that the impressions of the 1890s are imitative and superficial while the writings of Flaubert, Turgenev and Maupassant represent a progression towards the self-consciousness of the modernist novel.54 Far from being ignorant of impressionism, Pound would in fact seem to be finely attuned to its varying resonances in ways that are quite prescient. These resonances not only form the basis of the critical criteria by which Pound evaluates contemporary writing, but also transmit some of their own irregularity to his critical sensibility. In the years following his trip to Giessen in particular, impressionist imprecision would become something of a bugbear for Pound. He had already appended a satiric note in doggerel to Ripostes, in which he disdained:

[and] the Post-Impressionists who beseech their ladies to let down slate-blue hair over their raspberry-coloured flanks.

As late as 1919, he was still poking fun at ‘the neochromatist who rhymed ardoise and framboise in his endeavour to persuade “her” to let down her slate-coloured hair over her raspberry-coloured flanks’.55 The common targets of such complaints are imprecision and various types of appetite. In Pound’s examples, words spill over with meaning (‘rich’ is flavoured by ‘framboise’), or are distended with fattened vowels, too thickly rhymed, mangled through inexact metaphor.

By the standards he had absorbed from Ford, Monet’s painting and its derivatives were no longer too slavishly attached to the surfaces of things, but the opposite: too excitedly inexact, too extravagantly colourful, too distortive. In keeping with Pound’s new emphasis on hard outline, the evaluative criteria here are primarily textural. The chromatiste sort of impressionism occupies a subdivision of the soft: it is not the spectral haze exemplified by Yeats and ‘the French symbolists’, in which the ‘associations’ hanging near words are a glamorous mist shrouding their referents (PP, I, p. 112); it is heavier, staining objects with too much of the wrong kind of sentiment and smudging out the distinctions between itself and other art forms. In Pound’s writings, verse of this kind resembles uncooked batter, a glutinous slop which soils the outlines of things. Its most egregious examples are to be found in the ‘post-Swinburnian British line’:

The common verse in Britain from 1890 was a horrible agglomerate compost, not minted, most of it not even baked, all legato, a doughy mess of third-hand Keats, Wordsworth, heaven knows what, fourth-hand Elizabethan sonority blunted, half-melted, lumpy.56

Thicker than the rarefied symbolist mist, the English lyric impressions of the 1890s are a lumpy mix of borrowed forms; they provoke derogations which imply the ‘blunted’ outlines of baked pudding, such as ‘soufflé’, ‘soft, mushy edges’ and ‘slushiness and swishiness’.57 Verse of this type came to be one of Pound’s pet hates during his time in London. As foreign editor for Poetry, in particular, he felt that he was constantly fighting against Harriet Monroe’s susceptibility to ‘slop, sugar, and sentimentality’, her habit of ‘relapsing into the ’Nineties’ – formulations which suggest an undisciplined taste for ‘rich’ rhyme and poetic themes, as well as a ‘soft’ form in which words are melted into each other, legato.58 In 1915, he remarked that ‘[t]he “nineties” have chiefly gone out because of their muzziness, because of a softness derived, I think, not from books but from impressionist painting. They riot with half decayed fruit.’59

What emerges from this is a picture of self-division and irregularity within both impressionist aesthetics and Pound’s thought. More than any other poet who features in this study, Pound was attuned to the capacity of impressionism to suggest contrasting kinds of vision, just as he was the poet who most self-consciously incorporated this opposition within his responses to contemporary writing. On the one hand, he describes an impressionist style which is overreactive, yielding too easily to stimuli and then being too slack to retain their imprints. On the other, there is a more salutary form of impressionism that privileges precise definition and direct statement, and which serves as an austere corrective to the sentimentalism and flatulent verbosity of its sibling style. The binary is central to Pound’s critical pronouncements in the 1910s. It underlies, for example, his attempts to wipe clean poets he wished to salvage from the swill of the ‘nineties’. Thus, in a 1915 essay on Lionel Johnson, he remarks that ‘because he is never florid, one remembers his work’, praising his ‘definite statement’ and ‘short hard sentences’, and concluding that ‘[t]he impression of Lionel Johnson’s verse is that of small slabs of ivory, firmly combined and contrived’ (LE, p. 363). And it is there, too, in his editorial advice. In a letter of 1916 to Iris Barry he appraises a poem of hers entitled ‘Impression’, taking issue not with the impression itself, but with the specific kind of impressionism it exemplified: ‘“dissolve” is bad not only because it is, as I think, out of key with what goes before but because it really means a solid going into liquid, and when you compare that to pear-petals falling, you blur your image’ (LP, p. 79). Cumulatively, Pound’s critical remarks after 1912 illustrate that it was through two opposed sets of impressionist values that his thinking about poetry continued to be defined. His vacillation between these contraries exemplifies the semantic volatility intrinsic to impressionism’s central metaphor, but it also illustrates the propulsive effect of that volatility on Pound’s poetics, which undergo a radical shift in the wake of his visit to Germany.

Pound’s sense from 1912 onwards that ‘modern stuff’ should be ‘Objective – no slither’ has ensured the enduring association of imagism with notions of impersonality, hardness and objectivity.60 At the same time, his severe critical remarks about one branch of impressionist aesthetics have led Pound’s admirers to characterise impressionist painting as ‘an atmospheric, indefinite painting’, and to segregate the Image from a ‘pictorial’ poetic style sunk in ‘mists and twilight’ for which impressionist art was the principal model.61 In fact, this is only one part of the truth about imagism, just as it is only one part of the truth about Pound’s conceptions of impressionism. If Ford had helped Pound to purge his poems of certain prominent imperfections of contemporary style, Pound’s critical manoeuvres in the years after publishing Canzoni also retain the imprint of the aesthetics of epiphany which had informed his earliest writings. While many of the important tenets of imagist practice are indeed shaped by prose values, imagism is also underpinned by a set of stylistic priorities – ‘compression’, ‘hardness’, ‘intensity’ – that are established through dissent from Ford and a restatement of some of Pound’s earliest critical positions.

Pound absorbed various crucial stylistic principles from Ford after 1911, but he also voiced scepticism about their possible limitations, often in ways that indicate the persistence of convictions we find in his manuscripts of 1907 and 1908. In a review in early 1912 of Ford’s collection, High Germany (1911), Pound remarked:

[Ford’s] flaw is the flaw of impressionism, impressionism, that is, carried out of its due medium. Impressionism belongs in paint, it is of the eye. The cinematograph records, for instance, the ‘impression’ of any given action or place, far more exactly than the finest writing[.] A ball of gold and a gilded ball give the same ‘impression’ to the painter. Poetry is in some odd way concerned with the specific gravity of things, with their nature. […]

The conception of poetry is a process more intense than the reception of an impression. And no impression, however carefully articulated, can, recorded, convey that feeling of sudden light which works of art should and must convey. Poetry is not much a matter of explications.

There is a clear theoretical continuity between Pound’s opposition of art concerned with the gravity of things to art which records only their surface appearance and his earlier distinctions between ‘surface’ painting and art which goes ‘beyond’ this. The passage also points forward, foreshadowing the binaries which underpin his later theories of the Image as well as his claim that imagism represents a ‘more intense’ art form than its nineteenth-century precursors. In a way that augurs the argument Pound puts forward in ‘Vorticism’, in particular, there is a suggestion that impressionism, or one form of it, is too ‘of the eye’, just as there is the kernel of his argument that impressionism had been made redundant by the cinematograph. The argument in this case is framed differently, so that certain forms of impressionism in paint are said to be acceptable, but Pound is quite insistent that their strengths become flaws when translated into literature, and he repeats his view that ‘impressions’ are units of purely ocular perception. As late as 1923, in an essay ‘On Criticism in General’, he will reiterate this argument, remarking, ‘I think [Ford] goes wrong because he bases his criticism on the eye, and almost solely on the eye. Nearly everything he says applies to things seen. It is the exact rendering of the visible image, the cabbage field seen, France seen from the cliffs.’62 We observe a sort of aesthetic doppelgänger effect in Pound’s discriminations. His description of impressionism could equally serve as a description of imagism, which has often been said to be a pictorial form concerned with ‘the pure visuality of ordinary objects’ (or, more critically, ‘a mere lively heresy of the visual in the verbal’).63 Yet in this instance the purely ‘visual image’ is said to be a mistake, something which Pound defines his own aesthetics against. So while Ford’s language of objectivity functioned as a stylistic corrective, Pound also seems to have decided that it would not suffice as a complete poetics, and that the transcription of ocular perceptions was too passive and diffuse to ‘convey that feeling of sudden light’ which is central to his thought even as an undergraduate. Pound’s criticism indicates not just a further rounding-back in his thinking about impressionist aesthetics but also, because of this, an Image which is more complex, ‘intense’ and congruent with his early verse than critics have usually supposed.

In an instalment of ‘I Gather the Limbs of Osiris’ published in February of 1912, Pound implored greater ‘simplicity and directness of utterance’, but he was also careful to distinguish these qualities from those of daily speech – doing so, significantly, in terms that repeat the argument he had made in his letter to Williams four years earlier (PP, I, p. 69). Poetry, Pound suggests, is ‘more “curial”, more dignified’ than the language of conversation, perhaps even than prose, in virtue of having been formed ‘at the very crux of a clarified conception’:

This difference, this dignity cannot be conferred by florid adjectives or elaborate hyperbole: it must be conveyed by art, [by] something which exalts the reader, making him feel that he is in contact with something arranged more finely than the commonplace.

In their contempt for hyperbole, the comments reflect Ford’s influence, but they also indicate resistance: a certainty that verse must be more selective than simply ‘a quiet voice, just quietly saying things’, as Ford had described his own preferred style.64 In his review of High Germany a few weeks later, Pound turned this argument back on Ford, complaining of diffuseness and a lack of intensity: ‘Mr Hueffer is so obsessed with the idea that the language of poetry should not be a dead language, that he forgets it must be the speech of today, dignified, more intense, more dynamic, than today’s speech as spoken’ (PP, I, p. 71). In 1914, he suggested that ‘they’ – the writers who had followed Flaubert – ‘are often so intent on exact presentation that they neglect intensity, selection, and concentration’ (LE, p. 399). In ‘Vorticism’, impressionism is said to be a ‘flaccid’ or ‘spreading art’, whereas vorticism (and, by extension, imagism) ‘is an intensive art’ (GB, p. 90).

Yet Pound continued to associate his own poetry with forms with the impression at their heart. He first coined the term ‘Imagisme’ in the wake of an exhibition of Whistler’s paintings at the Tate Gallery, which ran from mid July to late October of 1912, and which he visited in August. The same exhibition prompted Pound to compose a poem ‘To Whistler: American (on the Loan Exhibit of His Paintings at the Tate Gallery)’, which he sent to Monroe in September with a letter restating his ambition ‘to carry into our American poetry the same sort of life and intensity which [Whistler] infused into modern painting’ (LP, p. 10). As he was revising ‘In a Station of the Metro’ in October, he again praised Whistler’s paintings, this time singling out those canvases which had taken their inspiration from ‘Japanese models’ in the New Age.65 In the pages of the Egoist a year later, he would remark that it was ‘From Whistler and the Japanese, or Chinese, the “world” [learned] to enjoy “arrangements” of colours and masses’ – an argument which is restated once more in ‘Vorticism’ as a comparison of Whistler and Monet: ‘the organization of forms is a much more energetic and creative action’, a more ‘intensive art’, ‘than the copying or imitating of light on a haystack’ (GB, p. 91).66

‘Intensity’ is the term running through all Pound’s early writings, from his first pieces of art criticism to his later definitions of the Image. It is also the term that clarifies the difference in Pound’s mind between imagism and one incarnation of its rival form, even as it bonds the Image to impressionism in other ways. Writing to Flint from St Raphael in 1921, Pound assented to Flint’s invitation to contribute, alongside Ford, to a rough draft of ‘our joint screed’ on imagism; but in his reply he also proposed that Flint write a critique of Ford: ‘Also chance for crit of FMH – Impressionism – probably closest accord with your own attitude – really in opposition to my constant hammering on vortex, concentration, condensation, hardness.’67 Ford’s ‘attitude’, like Monet’s, led in practice to dilution, diffusion, haze – a cumulative harvesting of impressions from multiple vantage points, rather than a compact distillation of instants of intellectual and emotional energy. As Ford himself remarked, albeit with a more positive emphasis, the impressionist programme involved ‘not so much the reconstitution of a crystallised scene in which all the figures were arrested – not so much that, as fragments of impressions gathered during a period of time’.68

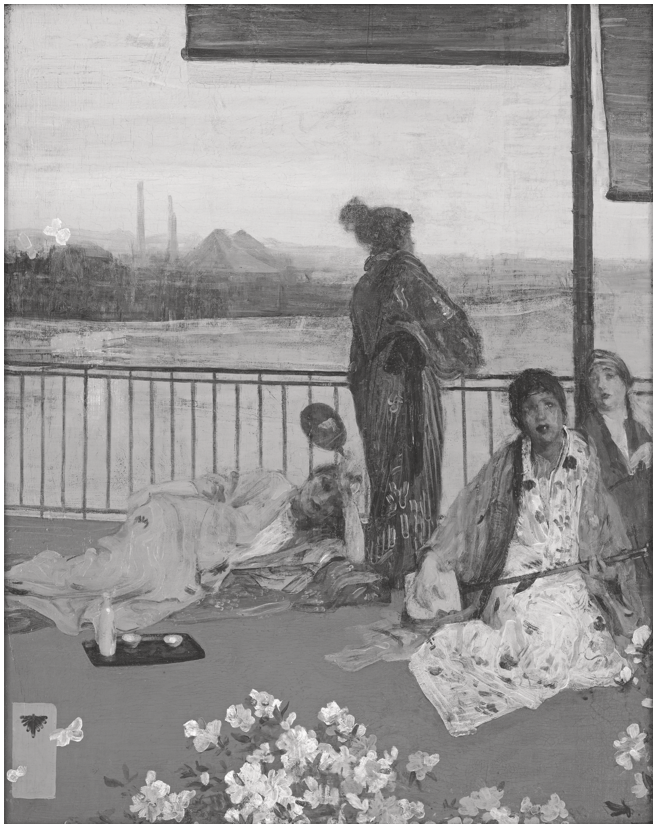

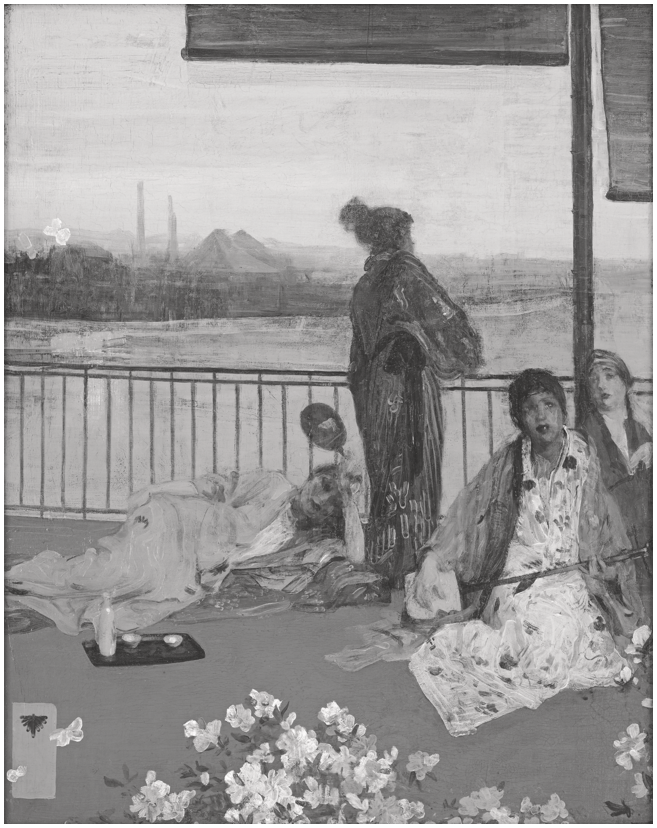

If ‘intensity’ meant concentration, energy, force, these were qualities for which Whistler’s paintings remained Pound’s primary models, the significance of which had been refreshed by his new sense of their alignment with oriental art. Whistler had been among the first Western painters to take an interest in Japanese art; in particular, he was drawn to the simplified outlines and ‘flat’, unshaded space of the ukiyo-e woodblock print, which would provide the inspiration for many of his paintings in the 1870s (see, for example, the The Balcony, Figure 4.2).69 Successive generations of English poets – Symons and Binyon in the 1890s, Flint and Hulme in the 1900s – had drawn analogies between the evocative sparsity of Whistler’s canvases and the elliptical compression of the haiku.70 Following his visit to the Whistler exhibition of 1912, Pound began to employ the epigrammatic, ‘hokku-like’ forms which have become synonymous with imagism.71 Along with the forms of compact allusiveness he found in Herbert Allen Giles’s History of Chinese Literature (1901), a copy of which he borrowed from Allen Upward in early 1913, the haiku provided Pound with a form that could heal the rift that had grown in his mind following his trip to Giessen by marrying condensation and luminosity to exact statement and limpid presentation. The result was the Image itself. In late 1913, Pound told Dorothy Shakespear, ‘There is no long poem in Chinese. They hold if a man can’t say what he wants to in 12 lines, he’d better leave it unsaid. THE period was 4th cent. B.C. – Chu Yüan, Imagiste.’72 Between August 1912 and the publication of Lustra (1916), Pound’s poetry is marked by processes of concentration, deletion and refinement – as when he reduced Giles’s ten-line translation of Lady Ban’s ‘Song of Regret’ to a brief three lines, entitled ‘Fan-Piece, for Her Imperial Lord’:

Pound’s short haiku-like poems are characterised by figurative precision and simplicity of utterance, but also by the brevity that is their subject. Here, beauty and romantic favour are fleeting like the translucent loveliness of frost-cumbered grass. In ‘Gentildonna’, similarly, five lines obliterate the beauty of youth, and age is summarised as ‘Grey olive leaves beneath a rain-cold sky’ (P, p. 93); in ‘April’, the ‘pale carnage’ of storm-stripped olive boughs appears like the sudden brightness of the poet’s ‘membra disjecta’ (P, p. 93).

Figure 4.2 James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony (1879), Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA.

Such poems exemplify the qualities of clarity and restraint that Pound repeatedly associates with Ford’s prose. In doing so, they portend a major vein of twentieth-century poetry. Yet they also represent a partial reversion to the vision and style of Pound’s earliest writings, which are characterised by an interest in gestural form and moments of epiphany, and often return to Whistler for models. Under the sign of the butterfly, a popular motif in Japanese prints, Whistler had reduced his subjects to their barest outlines; the sign for cognate processes of reduction in Pound’s poems is that of the petal, which has a special resonance in classical Japanese poetry as a symbol of the passage of time and the precarity of existence, and which appears everywhere in his contributions to Des Imagistes (1914) – in a station of the Metro, in an aubade for a dawn-lit lover (‘Alba’), and in the haiku-like ‘Ts’ai Chi’h’:

Petals appear in such poems as sudden emanations of intense or heightened beauty, proffering themselves as emblems of the tersely lucid forms which body them forth. Often Pound envisages petals in flame, or vice versa, as in ‘Heather’:

Or in a later poem, entitled ‘Phanopoeia’ (1920), in which flame and leaf are knotted together:

As here, such images fuse at moments of heightened perception; they are emblems not just of a poetic style, but also the kind of aesthetic experience it would engender: one in which radiant instants induce a state of silent epiphany. Such luminous instants form the crux of Pound’s discriminations between Ford’s impressionism and the aesthetics of the Image, which depend on a contrast between what Pound called ‘the “special moment” which makes the hokku’ and Ford’s more random and arbitrary ‘impression of a moment’.73 But they are also central to his earliest aesthetic convictions: the aphorisms at the head of A Quinzaine for This Yule (1908) repeat the Whistlerian dictum that ‘[b]eauty should never be presented explained’, and assert that art bestows ‘a slow understanding (slow even though it be a succession of lightning understandings and perceptions) as of a figure in mist’ (CEP, p. 58). This would be a picture of one impressionism enfolding another: of the epiphanic and eternal being rendered with a crystalline transparency, or of precise description being intensified by stringent modes of compression and concentration.

In Pound’s writings impressionism is cleaved in half, attaching to two opposed kinds of aesthetic vision, whose antagonistic relation brings forth an Image which retains the impression of both. He would later acknowledge parts of this inheritance. Pound’s tendency was to view the impressionist haze as the culmination of a long process of rarefaction, as when he suggested ‘that Wagner, [in] his manner of greatness, produced a sort of pea soup, and that Debussy distilled it into a heavy mist, which the post-Debussians have dessicated into a diaphanous dust’.74 In a letter to Ford in 1920, he suggested that vorticism was itself a product of this process:

certainly one backs impressionism, all I think I wanted to do was to make the cloud into an animal organism. To put a vortex or concentration point inside each bunch of impression[s] and thereby give it a sort of intensity, and goatish ability to butt.75

Pound conceives of Ford’s impressionism as a kind of cloud or mist, the haze resulting in this case not from esoteric ‘glamour’ but scientific decomposition, which yields a prismatic vapour of raw perceptual data. According to Pound, the vortex exists within this haze as a kind of movement-in-stasis, a fizzing or aggravated cloud of aesthetic energy. As Albright puts it, ‘what the Impressionists dispersed, the Vorticists will gather again, without resolidifying back to inert matter. A vortex is simply a wave that redounds back on itself, a wave as discrete, as self-contained, as a particle.’76 In this sense, the Image might be seen as both a product of impressionism’s capacity for self-rupture and a modernist avatar for its central metaphor.

This modifies the question of definition itself. It would be to say that neither the Image nor the impression seems sufficiently stable to be opposed in any straightforward fashion. It would also be to observe that this instability is one crucial way in which they resemble each other – to notice that just as the Image has been segregated from the impression on grounds of intensity, concentration, imaginative activity and so forth, so vorticism is separated from imagism, which has itself been vulnerable to the suggestion that it is a static or passive form of mimesis – and to draw attention to the fact that both are simplified by such distinctions.77 Like its impressionist precursors, imagism has often been characterised as a naïve, trivial or passive pictorialism – a ‘divagation’, as Kenner put it, from the ‘patterned energies’ which tessellate Pound’s later oeuvre.78 Yet this argument runs counter to Pound’s own sense of things, as when he complained that the hardness at the heart of imagist rhetoric had led to a misunderstanding of its founding principle: ‘If you can’t think of imagism [as] including the moving image, you will have to make a really needless division of fixed image and praxis or action.’79

Elsewhere, Pound suggested that the substance of the Image consists not in its parts but in the relationship between them:

The pine-tree in mist upon the far hill looks like a fragment of Japanese armour.

The beauty of this pine-tree in the mist is not caused by its resemblance to the plates of the armour.

The armour, if it be beautiful at all, is not beautiful because of its resemblance to the pine in the mist.

In either case the beauty, in so far as it is beauty of form, is the result of ‘planes in relation’. The tree and the armour are beautiful because their diverse planes overlie in a certain manner. There is the sculptor’s or the painter’s key. The presentation of this beauty is primarily his job.

The imagist poem divines ideal elements of design common to diverse things – essential ‘beauties of form’ that Pound will later call ‘the equations of eternity’ (GB, p. 122). As it had been in his earliest letters, it is the presentation of the ‘key’ – not the thing to be unlocked – that is central to Pound’s thinking. And this ‘key’ is valuable not in so far as it unlocks or illuminates things themselves, but in so far as it reveals their ‘relations’. The Image comprises pictorial elements, but it works non-pictorially; it is in the lacunae between its component images that the Image-proper is constituted. This would be the thrust of Pound’s insistence that the Image is ‘creative’ rather than representational: it relies on forms of mimetic limpidity – on pictorial images which adhere to the imagist doctrines of hardness and precision – but its final success rests on its capacity to provoke the relational energies which might join those parts. As Pound conceived it, the Image presents solidities for the mind to fuse together. Pound thought of this fusion as fluid and luminous (a ‘folding and lapping brightness’). It is from this doubled emphasis – on the necessity for clearly defined objects, on the one hand; on the galvanising force of the subject, on the other – that the central paradox of the Image springs: that it must be understood simultaneously as solid and fluid, visual and non-visual, fixed and moving.

Pound’s revisions to ‘In a Station of the Metro’ bring this paradox into clearer view. The version of the poem that Pound printed in ‘Vorticism’ is not the same as the final version he collected in Lustra and, later, Personae (1926), which has a semicolon in place of the colon; nor is it the same as the first version of the poem, which was published in Poetry in April of 1913 with additional spacing; nor is it the version printed in T.P.’s Weekly in June of the same year, which appears without a comma after ‘Petals’.80 In fact, the version he prints in ‘Vorticism’, with quotation marks and a space before the colon, seems to have been the version with which he was least satisfied: it was printed only once, being replaced with a lightly revised version in Pound’s Catholic Anthology of 1915, before taking its most stable form in Lustra. This incarnation of the poem overlays two images in a strongly contrasted linear arrangement, but the insertion of a semicolon equalises the relationship between the two lines:

Where in earlier versions a colon implies teleological sequence, the semicolon has the effect of making the comparison reversible. The competing demands of spatial and grammatical arrangement are deliberately orchestrated: in colliding grammatical fusion with spatial distinction, there is separation and relation at the same time. Each only exists because of the other. For Pound, imagism – like all valuable thought – is ‘a swift perception of relations’ (the definition of metaphor he ascribes to Aristotle).81 This is why Pound placed a premium on distinction. As Ethan Lewis has argued, ‘[o]nly separate entities can relate; once united, their relation and mutual predication is consummated, relegated to the past’.82 Unity would extinguish the floating whirl of mental energy by which the Image is sustained. In this sense, the imagism of the poem inheres in its semicolon.

‘In a Station of the Metro’ concentrates a set of competing forces which have their roots in Pound’s prolonged engagement with different conceptions of impressionist art. As I have suggested, the Image appears in fact to derive many of its precepts from specific (and often conflicting) impressionist styles, even if Pound frequently attempts to dissociate the two terms. While his definitions of impressionism often undercut one another, they provided Pound with a fruitful binary through which to structure his early poetry and poetics, and they reflect with startling clarity a dualism intrinsic to the impression itself. Moreover, because the Image emerges out of Pound’s pendular swings between contrasting kinds of impressionist vision, it inherits its own version of this dualism, becoming a kind of mirror-image of its rival term. In its fluctuating relation to objectivity and subjectivity, stasis and movement, the Image might therefore be seen not as a break from the semantic irregularity of the impression but rather as its most potent replenishment, and one which lodged this irregularity at the heart of a significant strain of twentieth-century writing.