Book contents

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Plates

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Note on the Cover

- Introduction: Curses, Religion, Aesthetics

- 1 Making Justice

- 2 Substance and Story

- Interlude

- 3 Tongues, Breath, Stutter

- 4 Incantation

- Conclusions

- Ancient Sources

- Bibliography

- Index of Ancient Sources

- Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

Introduction: Curses, Religion, Aesthetics

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 June 2024

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Plates

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

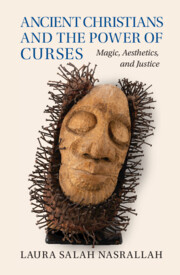

- Note on the Cover

- Introduction: Curses, Religion, Aesthetics

- 1 Making Justice

- 2 Substance and Story

- Interlude

- 3 Tongues, Breath, Stutter

- 4 Incantation

- Conclusions

- Ancient Sources

- Bibliography

- Index of Ancient Sources

- Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

Summary

Someone had it out for a garland weaver named Karpimē Babbia, a low-status woman who lived in Corinth in the late first or early second century CE. Chthonic Hermes, the goddess Anankē or Necessity, and the justice-exacting Fates are called upon to bring monthly destruction to her entire body, head to toe. Someone – a ritual practitioner with a client, most likely – made this curse by inscribing letters onto a thin lead tablet (Figure 0.1). What they wrote included rhythmic Greek, but also bubbled into a continuous stream of letters and sounds, the meaning of which is still unclear, which scholars call voces magicae: magical utterances. The curse-makers then rolled up the lead and pierced it with a nail, depositing it on or near a pedestal at the sanctuary of the goddesses Demeter and Kore, midway up the Acrocorinth, facing the busy city below and the blue of the Gulf of Corinth beyond.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ancient Christians and the Power of CursesMagic, Aesthetics, and Justice, pp. 1 - 42Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024