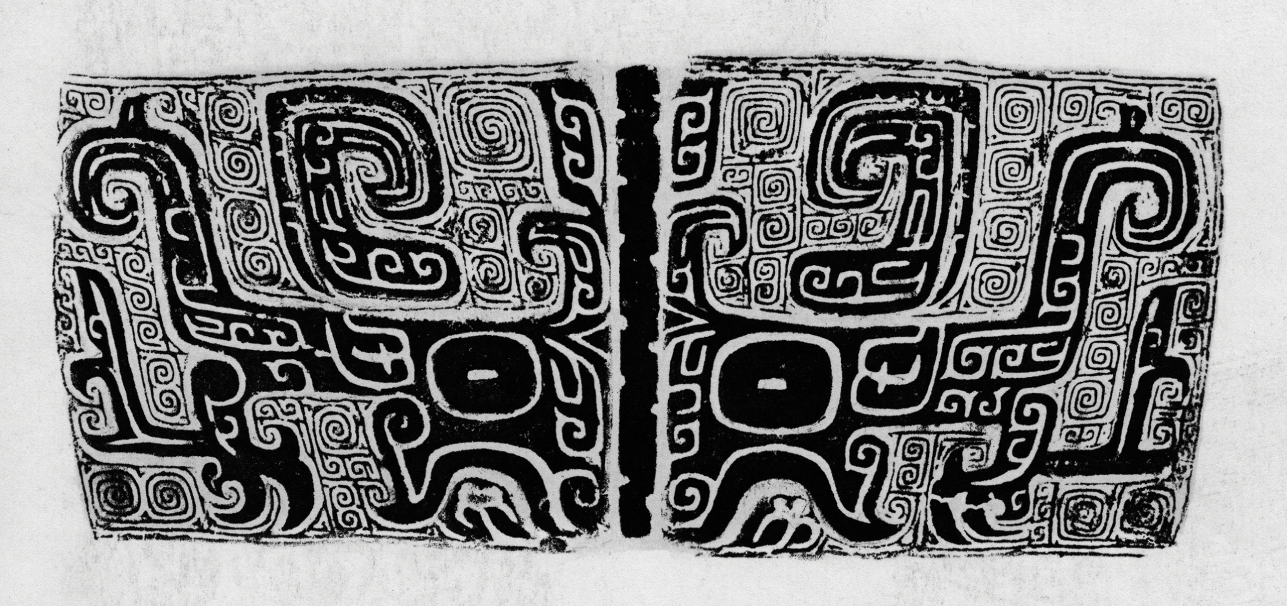

Animal images – whether realistic, imaginary, schematic or just recognizable – are seen all over the archaeology, art, material culture and orthography of the late Shang period (c. 1300–1050 BCE). Most of us get introduced to Shang animals through animal motifs in Shang art, particularly the two-eyed animal pattern called the taotie 饕餮 or ‘glutton’ mask, which is not only one of China’s most enduring and representative designs, but also one of the most original and distinctive in the iconography of the ancient world. The taotie is a highly complex and symmetrically arranged pattern-motif that can be looked at either as two animals joined together or as a single animal split apart.Footnote 1 Its origin is now reasonably determined as having derived from Neolithic prototypes,Footnote 2 and its early development and stylistic evolution in Bronze Age art has been traced through the type sites Erlitou 二里頭 (c. 1800–1600 BCE), Erligang 二里崗 (c. 1600–1400 BCE) and Panlongcheng 盤龍城 (1600–1400 BCE).Footnote 3 Yet there are still important connections to be made, as it concerns Shang ritual culture at the time when writing first appeared and when animals were first being written about.

First, I want to call attention to specific connections between late Shang Anyang period taotie animal ‘images’,Footnote 4 which by this time had evolved into being featured on bronze ritual vessels in high relief on a patterned background, sacrificial animals recorded on contemporary oracle bone inscriptions (hereafter OBI) and food and beverage for spirit and human consumption.Footnote 5 Data extracted from these material documents leave no question that an intimate connection existed between real-world sacrificial animals – particularly oxen, rams, antelopes and boars – and their images on the very bronze objects that either contained them or were meant to accompany their offering to the spirits.Footnote 6 Examining the minute and exact details of sacrifice and animals with this in mind, and within the context of humans’ attempts to predict and safeguard the future through bone divination and writing, adds another dimension of understanding of how text and image on this topic are related.Footnote 7

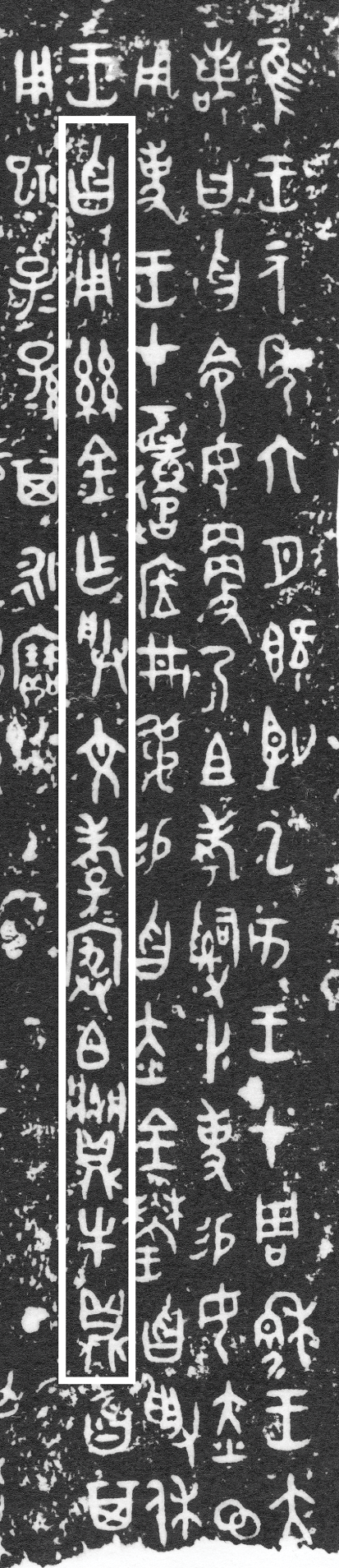

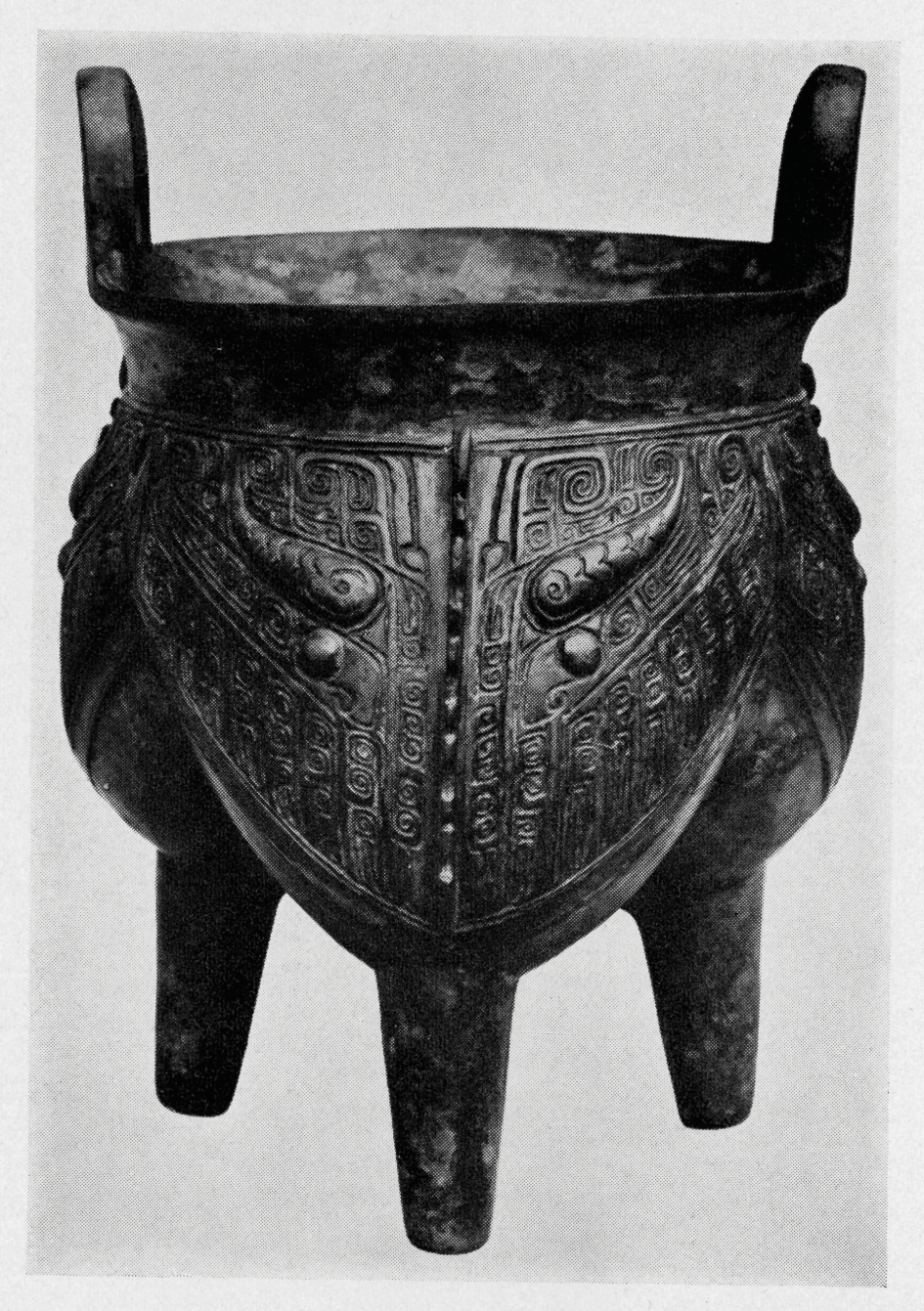

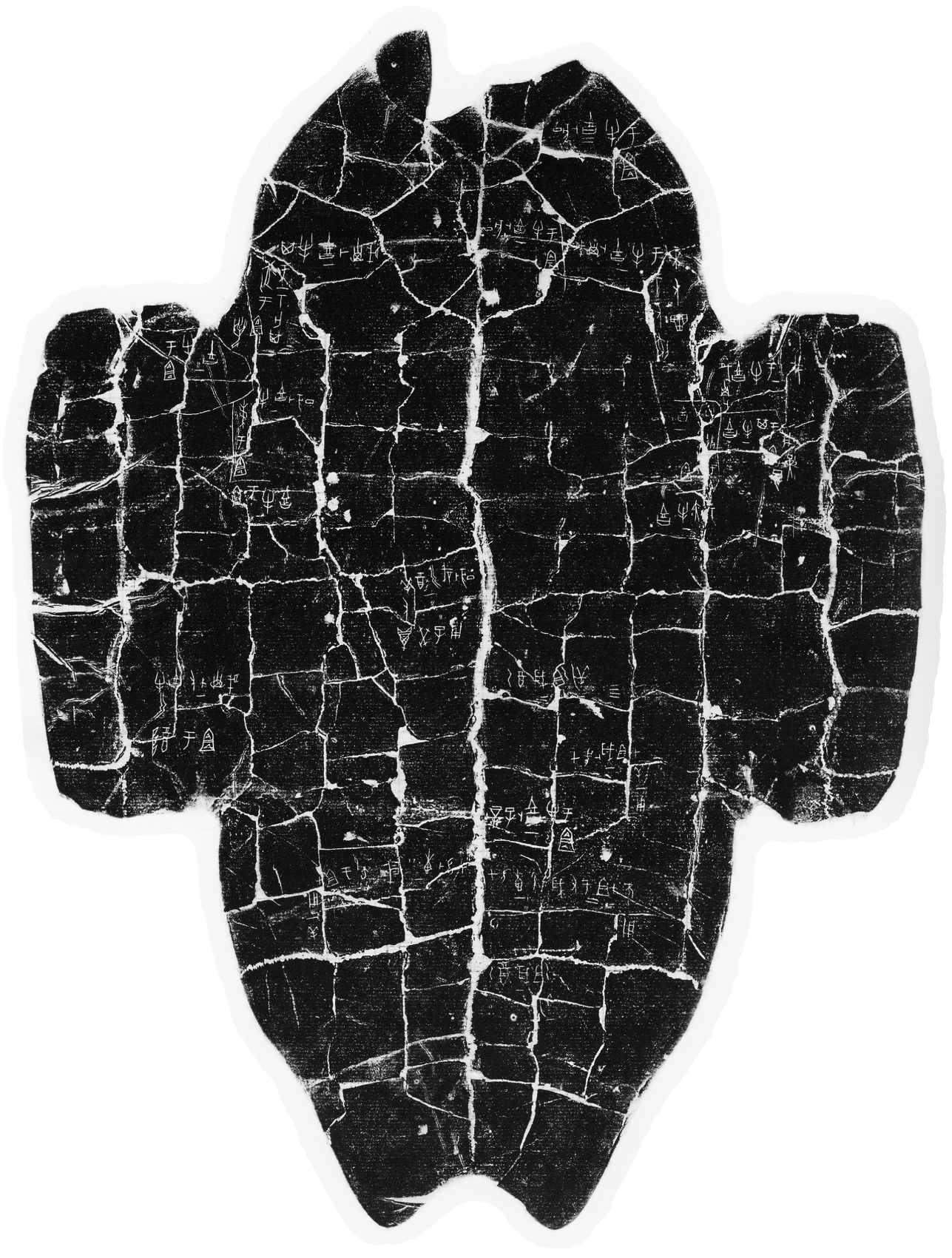

I would like the reader to imagine sets of ox bones (scapulae)Footnote 8 (Figure 1.1) being used to make divinations about an ox sacrifice and its accompanying grain and wine offerings – these very items were subsequently cooked and served in sets of ox-themed bronze vessels.Footnote 9 There exists a group of Western Zhou period (1045–771 BCE) bronze inscriptions where donors named their vessels after animal types like bovine, sheep, pig (Figure 1.2) and rabbit.Footnote 10 These examples show a direct connection between the ritual object, its motif, its inscription where the object’s name is recorded, and a specific sacrificial animal, whose meat would be cooked and served in it. Figure 1.3 shows the beginning of the famous Hu ding曶鼎 (Hu’s cauldron) inscription. The cauldron, explicitly stated as being used for sacrificial offerings, was called a ‘bovine cauldron’ (niu ding 牛鼎). Although the vessel itself is lost, it is not at all surprising to find Qing dynasty catalogues mentioning that its legs had bovine motifs.Footnote 11 Hu’s bovine cauldron, which was decorated on the outside with bovine motifs, was made for beef offerings.Footnote 12

Figure 1.1 Ox scapula Shang oracle bone (Jiaguwen heji 19813 recto: Early Wu Ding period) with multiple inscriptions inquiring about bovine sacrifice (arrows pointing to quantity (2) + bovine). Discovered in 1937 in Xiaotun North 小屯北.

Figure 1.2 Inscription on the Han Huangfu ding 函皇父鼎 (Yin Zhou jinwen jicheng [JC] 2745) that mentions a ‘pig cauldron’ (shi ding 豕鼎) (outlined) as part of a set (25) of ritual bronzes made for Huangfu’s wife, Diao Yun (line 1, characters 5–6), which included cauldrons (11), tureens (8), liquor (4) and washing vessels (2).

Figure 1.3 Beginning section of the Hu ding 曶鼎 (Jicheng 2838) with the sentence (outlined): ‘Hu uses this metal to make (for) my cultured father Jiubo a cauldron to set out beef offerings.’

Let us now take a Shang example, by comparing an OBI from the middle of the Anyang period that details ‘setting out ritual tripod cauldrons’ (zun li 尊鬲) and providing large-scale servings of beef from thirty heads of cattle to a royal ancestor (Figure 1.4), with a bronze ritual tripod cauldron which has bovine images (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.4 Shang oracle bone inscription (Heji 32125: Post Wu Ding period): (top register) ‘On Jiayin [day 51/60] tested: On the coming Dingsi [day 54/60] setting out tripod cauldrons to Father Ding, make viands from thirty heads of cattle’.

Figure 1.5 A Shang period ritual tripod cauldron with bovine taotie images. From An Exhibition of Chinese Bronzes.

What I want to illustrate is how, in one actual ritual performative instance, the vessel used for display was connected to the animal offering, and how vessels of this type (cauldrons) were often decorated with images of this category (bovine) of sacrificial animal. Similar exercises, both inscriptional/art historical and orthographical/art historical, can be done with sheep, pigs, tigers, birds, horses, deer and fish.

There is an enormous amount of qualitative data on animals in OBI. They were, quite literally, the bones and joints that held the elite skeleton of early Chinese ritual culture together. Rather than providing a synthesis of sacrificial animals as they exist across nearly two centuries’ worth of OBI, I will focus here on how these special types of animals were sanctioned and used in religious rituals over a defined time period concurrent with the taotie motif’s high period. My more general point, however, is not about the complex meanings of ritual iconography, but rather the importance of animals to Shang ritual observed through the planning and preparation stages. A corpus-based approach to a scientifically excavated oracle bone archive like the one described below, which was unearthed at Huayuan zhuang East (Huayuan zhuang dongdi 花園莊東地, hereafter HYZ OBI) in 1991 (published in 2003) not only provides us with a complete and reliable dataset from which to work, but also offers a unique insight from first-hand records on the topic of animals and sacrifice. To study sacrificial animals first requires a prefatory overview of the institution of sacrifice itself: why and what kinds of animals were needed and how were they used? I begin therefore with a brief discussion of the organization, typology and disposition of Shang religious rites.

Sacrificing to the Shang royal ancestors, especially the former kings and their spouses, was a daily preoccupation and major corporate enterprise. Divination records on religious rites and activities number in the tens of thousands and are, by far, the largest and most complex genre of oracle bone inscriptions. As a core institutional practice, divination on this particular topic was used to certify the royal worship agenda and to fix the minute details of sacrificial and festive offerings. The lesser was pursued for the sake of the greater.

In contrast to divinations produced by or on behalf of the Shang kings, those produced by or on behalf of royal family members present novel and emic perspectives on ritual motivation and ancestral preoccupation, as well as demonstrating access and control over valuable economic resources. While Royal Family Group oracle bone inscriptions (hereafter RFG OBI) account for only roughly 2–3 per cent of an entire corpus of more than 100,000 pieces, they reveal crucial information about life and society outside of the king’s immediate purview.

Amongst this relatively unknown and extremely understudied group of inscriptional materials, none is more important than the recently unearthed oracle bone inscriptions from Huayuan zhuang East OBI. Made in the southeast corner of the moated enclosure of the palace-temple complex at Anyang, this important discovery is a synchronically compact and unified corpus of 2,452 individual divination accounts inscribed on 529 (345 completely intact) turtle shells and bovine scapulae.Footnote 13 Produced by or on behalf of an adult son of the twenty-seventh king Wu Ding 武丁 (r. c. 1200 BCE) over a relatively short period of time (probably several years), the HYZ OBI provide the most unified and diachronically succinct ‘week-at-a-glance’ account of daily life in early China. A corpus-based approach and synchronization of inscriptions into these sets offers first-hand insights into the organization of religious rites and the resources available to an important junior member – a prince – of an elite royal lineage, which played a major role in the development of Chinese civilization.

The Organization and Typology of HYZ Ancestor Worship

There were two types of Shang religious rites – those performed for ancestors, and those performed for natural powers. Those for ancestor worship can be further separated into two sub-types. The first were highly regulated and performed weekly, cyclically (or seasonally), and for particular milestone events. The second were impromptu and performed out of necessity, such as to cure an illness, to dispel calamity or to protect against it.Footnote 14 The HYZ OBI do not include any occurrence of worship events to any natural powers, such as the High God (Di 帝), mountains and rivers. The fact that such a large archive contains no such records almost certainly means that they were restricted amongst the royal family to everyone but the king. This is something that we were not fully aware of before this discovery. In summary, all of the HYZ OBI on the topic of sacrifice were related to ancestors. The majority can be classed as regular worshipping, with a minority being impromptu and in response to necessity.

The Ancestors and Weekly Worship

Weekly worship refers to the performance of rites and food offerings to ancestors on their specific temple-days within the period of one ten-day week, from Jia 甲 [day 1/10] to Gui 癸 [day 10/10]. HYZ ancestor worship followed a strict adherence to the schedule: rites and offerings of sacrificial items were only performed on an ancestor’s temple-day, that is, when the day of the ritual event (in bold below) and the day name of the ancestor (in bold below) matched.Footnote 15

甲寅歲祖甲白豭一![]() 鬯一登自西祭 一

鬯一登自西祭 一

(1) On Jiayin, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Jia one white boar, offer one measure of aromatic ale, (and) raise up (or: let him taste) sacrificial items from the west.Footnote 16 #1 (4.1)

乙未歲祖乙豭子祝在阜 一二

(2a) On Yiwei, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi some boars (and) our lord will pray. At Fu. #1, 2 (13.2)

丁酉歲妣丁![]() 一在阜 一

一在阜 一

(2b) On Dingyou, sacrifice (to) Ancestress Ding one sow. At Fu. #1 (13.5)

This selection of inscriptions provides a good introduction to divinations on ancestor worship as a type, and the HYZ OBI as a corpus. The most basic form of these divinations starts with the date of a sacrificial event, followed by a verb that – in this context – meant ‘to sacrifice’ (sui 歲; to be read gui 劌 ‘to chop-cut’), the name of the recipient ancestor, and the kind of animal to be used. Complex forms, which are divinations containing more than one clause, commonly included sub-activities that accompanied the sacrificial event, such as the presentation of ale and grain, prayer and announcements, and music and dancing. A distinctive emphasis on the colour and gender of animals added complexities to the diviner’s practice. These OBI further confirm the Shang’s predilection for the colour white,Footnote 17 in addition to revealing their preference, if and when available, for matching an animal’s gender to a recipient ancestor.

The most notable feature of HYZ ancestor worship was that the chief recipients were all proximate ancestors no more than three generations older than the prince and protagonist of the divinations. HYZ divinations on religious affairs basically present a diachronic account of how a Shang prince interacted with his dead grandparents, great uncles and aunts, and great-grandparents. This suggests that, for those other than the king, the most ritual weight was placed on maintaining a relationship between living performers and those deceased family members who proactively resided in their personal memory.

Statistics demonstrate that the prince’s grandmother (Ancestress Geng; bi Geng 妣 庚), grandfather (Ancestor Yi; zu Yi 祖乙) and great uncle (Ancestor Jia; zu Jia 祖甲) received the largest amount of ritual attention by far.Footnote 18 The collection and synchronization of multiple divination sets into longer timelines further reveal that, over consecutive ten-day weeks, at least these particular ancestors were offered sacrificial worship once a week. Barring a conjunction with periodic or seasonal ritual cycles discussed below, each ancestor’s temple-day worship appears to have been carried out once weekly throughout the year. With regard to those ancestors mentioned above, this means that the HYZ prince would have needed a minimum of three animals per week to sacrifice.Footnote 19

Bouts of divination were routinely started prior to temple-days – sometimes as far as a ten-day week in advance, in order to set its agenda and fix the details – and they usually continued right through the day of the event, to ensure that the ritual package was correct. The procedures and activities carried out on the day of a weekly ancestral rite maintained a consistent form. Presumably ending with a feast (xiang 饗) in the late afternoon (dinner time), and with some of the sanctified meat being distributed to participants and/or delivered to absentees, the day’s activities centred on two separate but intertwined main events – a sacrificial killing and a subsequent libation (guan 祼). The type and amount of fare seems to have varied in accordance with status and gender, and a typical meal consisted of viands, an aromatic ale called chang 鬯 and grain. A less frequent but equally important second line of sacrificial rites centred on human beheadings (fa 伐), which were often flanked by animal slaughter and preceded by a different type of libation and viand offerings.

Joint Rites and Joint Offerings

There are two types of joint rites in the HYZ OBI: joints of ancestors with corresponding temple-days, and joints of ancestors with non-corresponding temple-days. The former refer to offerings made to multiple ancestors with the same temple-day on the same day of the week, while the latter refer to offerings made to multiple ancestors with different temple-days on the same day of the week. While it is certainly possible to suggest that identical sacrifices for different ancestors commanded equal status from the donor’s perspective, there also seem to have been economic reasons for making such multiple offerings. As the following examples illustrate, diviners proposed using whatever their patron had or anticipated having ‘in stock’ – in this case, lamb for everyone. The divination within the series about not including liquor (3b) probably does not mean that the spirits would not want it, but rather that it was simply ‘out of stock’ at the time. Other records confirm such deliveries (HYZ 265, 286) and sacrificial items offered by other contributors (HYZ 226, 237). Ad hoc requests (HYZ 218, 297) for and donations (HYZ 450) of ritual items were – and still are – an integral part of the social fabric of a ritual culture.

己酉歲祖甲![]() 一歲[祖乙]

一歲[祖乙]![]() 一入自

一入自![]() 一

一

(3a) On Jiyou, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Jia one ewe (and) sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi one ewe when entered from Lu. #1 (196.1)

弜又鬯用 一

(3b) Do not have aromatic wine. Used. #1 (196.2)

惠一羊于二祖用入自![]() 一

一

(3c) Let it be one sheep to the two Ancestors (i.e. Ancestor Jia and Yi) that is used when entered from Lu. #1 (7.2)

庚戌歲妣庚![]() 一入自

一入自![]() 一

一

(3d) On Gengxu, sacrifice (to) Ancestress Geng one ewe (when) entered from Lu. #1 (196.6)

Ancestors that shared the same temple-day, as demonstrated in the sequence below, were referred to by a distinctive formula that put two kinship terms next to each other and used the single day name they had in common after it. As one can see, the selection of animals was deductive. It began with a category (sheep) (4a) and continued on to a refined item level (4b). The inability to validate the category of sheep led to a subsequent divination proposing, in a more resolute fashion, an alternative category (4c).

乙卜惠羊于母妣丙 一

(4a) On Yi divined: Let it be sheep to Mother, Ancestress Bing. #1 (401.1)

乙卜惠小![]() 于母祖丙 三

于母祖丙 三

The motivation of this sequence was not so much which ancestors to sacrifice to on the following day – since that was fixed – but rather, what to give to whom. The use of the modal copula hui 叀 (惠) at the head of the first two inscriptions placed focus on, and expressed a preference for, the object that followed.

The joining of an ancestor into the worship activities of another one with a different temple-day is a unique aspect of the practice of regulated weekly and cyclical rites. Here I only cite the former, as the form, syntax, and context between the two differ rather significantly. Joining ancestors together for a cyclical rite is discussed later.

乙巳歲祖乙牢牝刏于妣庚小![]() 一

一

甲子卜夕歲祖乙祼告妣庚用 二

(6) On Jiazi divined: Make an evening sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi, (and by means of) the ale libation, make an announcement (to) Ancestress Geng. Used. #2 (474.2)

The events mentioned in these two divinations were both performed on days for the worship of the prince’s grandfather, Ancestor Yi. The inclusion of this ancestor spouse into ritual events for her husband will be seen again in the following section. These examples vividly illustrate how the living understood marriage to continue in the afterlife.

The Ancestors and Cyclical Sacrifices

‘Cyclical Sacrifices’ (zhouji 周祭) refers to a system comprised of three main cycles – Yi 翊, Rong 肜 and Ji 祭, and totalled five rites in all, with the inclusion of two additional sub-cycles within the Ji 祭-cycle. Each cycle, which organically grew with the death and subsequent inclusion of each dead king and his main spouse, spanned up to several months and together constituted one ritual year (si 祀). Thus, in addition to weekly ancestor worship, each recipient ancestor included in this system would have also received – based on the order of his or her succession – five larger and more elaborate ‘periodic’ worship events each year. Animals were offered in larger quantities for these special events (especially in the king’s rites) and their selection and ‘ritual packaging’ had even more importance than usual. These records elucidate the way animals could be used to bind generations and relationships together ritually – the living with the living, the living with the dead, and the dead with the dead – through the medium of the living. Time phrases that appear in the HYZ inscriptions indicate that people other than the king ritualized time ‘ancestrally’.

The most notable feature of the HYZ dataset as a group is the reserved use of a single type of animal for the Cyclical Sacrificial Rites and a specific cutting procedure – carving (gua 刮). A typical example, such as the one adduced below, focuses on whether this ritual package for one of the cycles will make the prince’s grandmother happy.

庚辰卜刮肜妣庚用牢又牝妣庚衍(侃)用 一

(7) On Gengchen divined: Carving Rong-rite (offerings) (to) Ancestress Geng, use pen-raised cattle (and) offer cows; Ancestress Geng will be happy. Used. #1 (226.11)

‘Happy’ (kan 侃) is a frequently used divination coda in the HYZ OBI. Its repeated occurrence at the end of a divination statement – particularly in a special binary combination with ruo 若 ‘approved; favourable’ (seventeen instances) – is a highly characteristic feature of the corpus as a whole and indicative of a specific tradition of divination practice. But what is even more interesting for us here is the belief that offering a specific animal type would produce this emotion. The limited number of these major rites performed over a year made happiness absolutely essential. Freshly carved beef equalled happiness.

In comparison to more complex divinations of this type discussed below, I refer to (7) as ‘simple’, because it recorded a single ancestor and both the date of the divination and the date of the event matched her temple-day. In the following two inscriptions, sacrifices made to junior or lower-status ancestors (underlined) were incorporated into the temple-day of a senior or higher-status ancestor (in bold). The form and syntax of this type of inscription is new to the OBI, has not yet been discussed in scholarship, and is open to interpretation. The reading that I advance here is significant for better understanding connections between the dead amongst themselves and interventions from the living.

丁巳歲祖乙![]() 一刮祖丁肜 三

一刮祖丁肜 三

(8) On Dingsi, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi one ram (and) carve (it for) Ancestor Ding’s Rong-rite. #3 (226.5)

乙巳歲妣庚![]() 一刮祖乙翊 一二三

一刮祖乙翊 一二三

(9) On Yisi, sacrifice (to) Ancestress Geng one sow (and) carve (it for) Ancestor Yi’s Yi-rite. #1,2,3 (274)

The form of these two inscriptions is identical. Each contains two clauses that start with the date of the ritual event and continue as:

Sacrifice + ancestor name + animal type and quantity (initial clause)

Carve + ancestor name + name of event (final clause)

The days of the ritual carving event match the day names of the ancestors in the second clause, whereas the names of the ancestors mentioned in the initial clause, and for whom the sacrifices were made, do not match the date. The syntax is different from the inscriptions mentioned previously in the section on joint rites. There, the name of the temple-day ancestor always preceded the temple-day ancestor with a non-corresponding day name which was joined in. As I understand it, the ram and sow were contributory sacrifices made in the name of one ancestor to another who was intimately related and senior to him/her; Ancestor Yi was Ancestor Ding’s son and Ancestress Geng’s husband. K.C. Chang’s hypothesis, cited at the start of this chapter, can therefore be expanded upon. According to this view, animals not only brought the living together with the dead, but also connected the dead with the dead.

Pen-raised Animals

Cattle ![]() (lao 牢), sheep

(lao 牢), sheep ![]() (xiang?

(xiang? ![]() ) and pig

) and pig ![]() (jia 家) are the three categories of pen-raised animals in the HYZ stock. As David Keightley comments, ‘The oracle bone graph depicts a cow or sheep penned under a roof; cf. the Shuowen definition, 牢,閑養牛馬圈也, ‘lao is a pen for enclosing and rearing bovines and horses’, thus suggesting an animal especially reared for sacrifice.Footnote 20 OBI scholars conventionally read lao 牢 as ‘penned cow’ and xiang?

(jia 家) are the three categories of pen-raised animals in the HYZ stock. As David Keightley comments, ‘The oracle bone graph depicts a cow or sheep penned under a roof; cf. the Shuowen definition, 牢,閑養牛馬圈也, ‘lao is a pen for enclosing and rearing bovines and horses’, thus suggesting an animal especially reared for sacrifice.Footnote 20 OBI scholars conventionally read lao 牢 as ‘penned cow’ and xiang? ![]() ‘penned sheep’. The HYZ lexicon now includes one of the earliest occurrences of jia 家, i.e. ‘penned pig’ (HYZ 61.3), which was co-opted around this time to mean ‘family, house’ (e.g. HJ 3096).

‘penned sheep’. The HYZ lexicon now includes one of the earliest occurrences of jia 家, i.e. ‘penned pig’ (HYZ 61.3), which was co-opted around this time to mean ‘family, house’ (e.g. HJ 3096).

With the exception of the one interesting orthographic variant mentioned below, the absence of animal gender in these combined spellings infers that, in a graph like 牢, the ‘牛’ component inside the roof could refer to either a bull or a cow. Thus, the emphasis was not on an animal’s gender but on whether it was pen-raised or not.

The following set of divinations from HYZ 70 presents a simple, selective focus on which category of pen-raised animal should be used for an unspecified ritual event. The diviner, still in a categorical decision stage, shifts back and forth between odd numbers of pen-raised cattle and young sheep. When his first divination proposing three young sheep was inconclusive, he upped the offer by two. The inability to validate either led him to hand it over to his superior, the prince, to check:

三牢 一二║Footnote 21 三小![]() 一二║三牢║ 五小

一二║三牢║ 五小![]() 一二三║ 子貞 一

一二三║ 子貞 一

(10a) Three (heads of) pen-raised cattle. #1,2

(10b) Three young pen-raised sheep. #1,2

(10c) Three (heads of) pen-raised cattle.

(10d) Five young pen-raised sheep. #1,2,3

(10e) Our lord tested (it). #1

The diviner did not consider gender. Another inscription seems a continuation of this decision process:

甲辰卜歲祖乙牢惠牡 一二

(11) On Jiachen divined: When sacrificing (to) Ancestor Yi pen-raised cattle, let them be bulls. #1,2 (169.2)

Amongst the group of pen-raised animals, a special ritual value was evidently accorded to young pen-raised sheep (thirty-six instances). There is also one instance of the previously unseen graph ‘young pen-raised ram’ (小![]() ). Written as

). Written as ![]() (HYZ 354.1), this is a rare occurrence in Shang palaeography where the gender of a pen-raised animal was specified. As an exception, it might be better understood as a scribal abbreviation meant to denote

(HYZ 354.1), this is a rare occurrence in Shang palaeography where the gender of a pen-raised animal was specified. As an exception, it might be better understood as a scribal abbreviation meant to denote ![]()

![]() Footnote 22 ‘pen-raised sheep-ram’. The number of young pen-raised sheep offered up in the OBI is as high as ten (HYZ 45.3, 455.1, 89.5; HJ 19849). I will return to the significance of these numbers later.

Footnote 22 ‘pen-raised sheep-ram’. The number of young pen-raised sheep offered up in the OBI is as high as ten (HYZ 45.3, 455.1, 89.5; HJ 19849). I will return to the significance of these numbers later.

The Taxonomy and Palaeography of Sacrificial Animals

The animals most commonly used for sacrifice were cattle, sheep and pigs. It is, therefore, no coincidence that the first two are the most common taotiemotifs. HYZ palaeography contains a large number of individual graphs for males and females of each animal type (Table 1.1). Gender in these graphs was represented either by the pictographic addition of a reproductive organ, a deictic mark (a small circle – see ‘sow’ in Table 1.1) or a phonetic value – tu土 for males and bi 匕 for females. Differentiating a pig’s gender by its reproductive organ is a characteristic feature of HYZ script. Yet this method of graphic depiction was not applied for any other animals, which were written as phonographs (xingsheng zi 形聲字), i.e. one classifier plus one phonetic value.

Table 1.1 Selected HYZ palaeography of animals.

| Animal | Bone graph | Transcribed form |

| Bovine | 牛 | |

| Prime bovine | 吉牛 | |

| Bull | 牡 | |

| Cow | 牝 | |

| Sheep | 羊 | |

| Ram | ||

| Ewe | ||

| Pig | 豕 | |

| Castrated pig | 豖 | |

| Boar | 豭 | |

| Wild boar | 彘 | |

| Male wild boar | ||

| Hairy boar | ||

| Sow | ||

| Antelope | 廌 | |

| Male antelope | ||

| Female antelope | ||

| Dog | 犬 | |

| Deer | 鹿 | |

| Musk deer | 麇 |

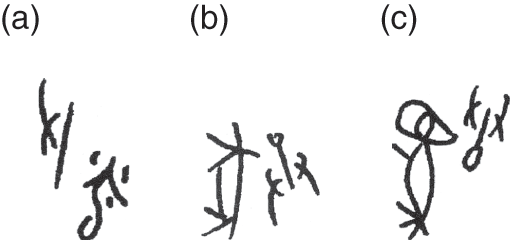

Aside from this pictographic depiction of pigs, variants of boar and sow were also written as phonographs and composed of shi 豕 ‘pig’ + phonetic (土/匕). There is, however, more we can find in the HYZ corpus: the three variants of ‘boar’ (in Figure 1.6) trace the diachronic evolution from pictograph to phonograph:

(1) is a pure pictograph that depicts a pig with an emphasized penis; (2) is a ‘pseudo’ phonograph, in that it is composed of a horizontally orientated tu 土 written just off the pig’s belly. It still seems intended to represent its penis. ‘土’ as a phonetic value seems to have been retained because of its relatable shape; (3) is a phonograph, having moved ‘土’ away from the pig and writing it in a vertical orientation to its side as ![]() . In the Han lexicon Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 (Explaining Graphs and Analysing Characters) the word for ‘boar’ was jia 豭, a pure phonograph comprised of a pig classifier plus phonetic, while in excavated Warring States materials from the Chu state (i.e. modern Hubei) it was represented by yet another variation written as

. In the Han lexicon Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 (Explaining Graphs and Analysing Characters) the word for ‘boar’ was jia 豭, a pure phonograph comprised of a pig classifier plus phonetic, while in excavated Warring States materials from the Chu state (i.e. modern Hubei) it was represented by yet another variation written as ![]() , that is shi 豕 ‘pig’ phoneticized by gu 古. In classical Chinese tu 土, jia 叚 and gu 古 all belonged to the same rhyme group, yu 魚. Of the three, jia 豭 eventually became the standardized Han dynasty form for boar.

, that is shi 豕 ‘pig’ phoneticized by gu 古. In classical Chinese tu 土, jia 叚 and gu 古 all belonged to the same rhyme group, yu 魚. Of the three, jia 豭 eventually became the standardized Han dynasty form for boar.

Figure 1.6 Variant spellings of jia 豭 ‘boar’ in HYZ script.

Two other logographs in the HYZ palaeography relating to the disposal of sacrificial animals were written with a pig element. The graph conventionally used to write the word sha ![]() (殺) ‘to kill’ is one such example. This form, seen throughout all periods of the Shang script (Figure 1.7a), depicts a hand holding a hammer (chui 錘) or club next to a bloody chong 虫 (the classifier for reptile or insect here is likely to be a type of snake). The HYZ script has two innovative writings (HYZ 76.1 and 226.7) where the ‘reptile’ gets substituted by either ‘pig’ (Figure 1.7b) or ‘buffalo’ (Figure 1.7c).Footnote 23

(殺) ‘to kill’ is one such example. This form, seen throughout all periods of the Shang script (Figure 1.7a), depicts a hand holding a hammer (chui 錘) or club next to a bloody chong 虫 (the classifier for reptile or insect here is likely to be a type of snake). The HYZ script has two innovative writings (HYZ 76.1 and 226.7) where the ‘reptile’ gets substituted by either ‘pig’ (Figure 1.7b) or ‘buffalo’ (Figure 1.7c).Footnote 23

Figure 1.7 Variant spellings of sha 殺 ‘to kill’ in HYZ script.

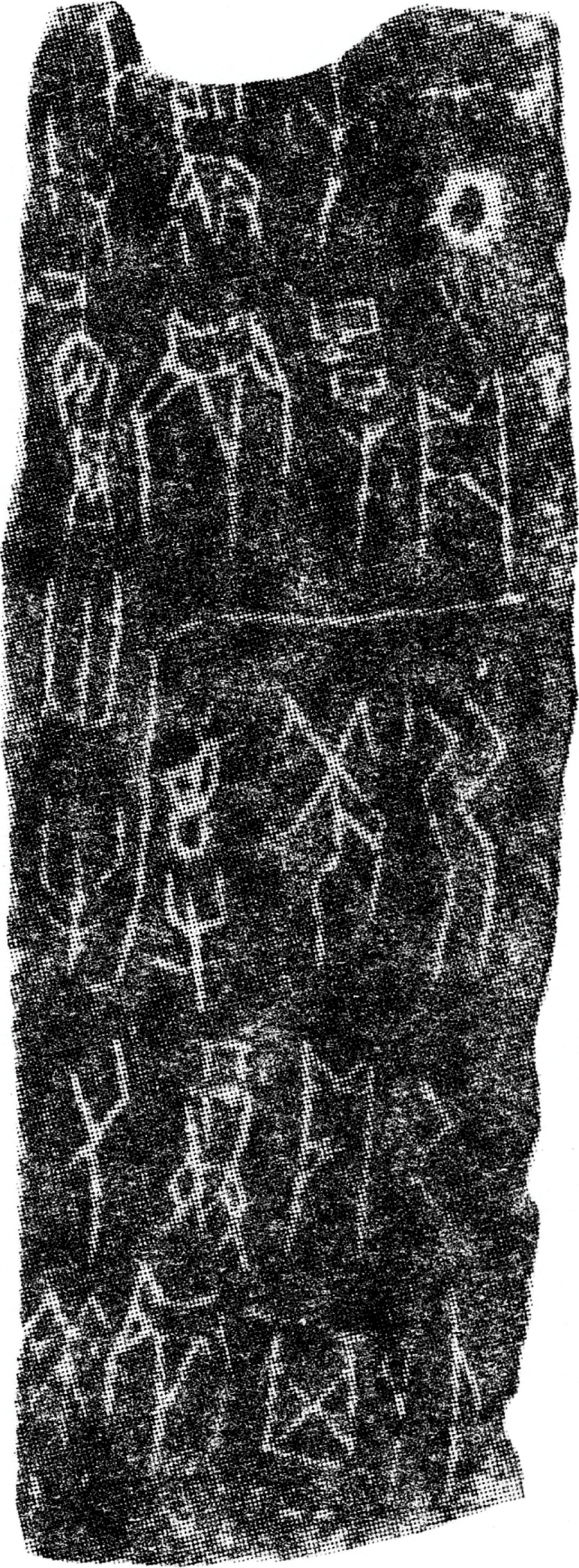

The second example, bo 剝 ‘to pare’, is a compound pictograph that conveys its meaning through the combination of pig and knife.Footnote 24 Its most familiar occurrence in early Chinese texts is as number 23 of the Yijing’s 易經 (Book of Changes) sixty-four hexagrams. The HYZ OBI now contain possibly the earliest – and certainly the most informative – usage of bo in a sacrificial context. HYZ 228 (Figure 1.8) is a complete turtle plastron which has been used in numerous divination sessions and is inscribed densely with nineteen interrelated divination records. The focus of this large divination set is on strong, prime cattle (ji niu吉[佶]牛)Footnote 25 – whether they should be pared and presented on viand tables or an altar, or both – and if the arrangements would lead to an undesirable outcome for the person who made the final decision to do so. Let’s look at a brief selection:

丁亥卜吉牛介于宜 一

(12a) On Dinghai divined: Prime cattle – parts to the viand tray(s). #1

丁亥卜吉牛[皆]于宜 一

(12b) On Dinghai divined: Prime cattle – [all] to the viand tray(s). #1

吉牛于宜 一

(12c) Prime cattle to the viand tray(s). #1

吉牛其于宜子弗艱 一

(12d) If the prime cattle go to the viand tray(s), our lord will not be troubled (by it). #1

戊子卜吉牛于示又剝來有曲 一

(12e) On Wuzi divined: Prime cattle going to the altar – offer and pare what has come from the Qu? (a tribal group or place name). #1

戊子卜吉牛其于示亡其剝于宜若 一

(12f) On Wuzi divined: If prime cattle go to the altar stand, (and) if there is none pared for viand tray(s), (it) will be favourable. #1

戊子卜吉牛于示 一

(12g) On Wuzi divined: Prime cattle to the altar. #1

吉牛亦示 一

(12h) Prime cattle also (to) the altar. #1

戊子卜又吉牛弜尊于宜 一

(12i) On Wuzi divined: Offer prime cattle, (but) do not present (them) on viand tray(s). #1

Figure 1.8 HYZ 228; from Yinxu Huayuan zhuang dongdi jiagu (2003).

The Economic Value of Sacrificial Animals

OBI on the topic of sacrifice commonly record offering lists of animals. The sequence in which the animals are listed indicates each animal’s hierarchical value vis-à-vis the others. For example, pen-raised cattle appear in fifty-four instances and, when used in combination with other animals, commonly lead the offering list.

乙亥升歲祖乙二牢物牛白豭![]() 鬯一子祝二三

鬯一子祝二三

(13) On Yihai, make ascend sacrificesFootnote 26 (to) Ancestor Yi (of) two pen-raised cattle, variegated cattle, white boars, offer one measure of aromatic ale, (and) our lord will pray. #2,3 (142.5)

庚午卜在阜禦子齒于妣庚[![]() ]牢物牝白豕用 一二

]牢物牝白豕用 一二

(14a) On Gengwu divined, at Fu: To exorcise our lord’s tooth to Ancestress Geng, [register] pen-raised cattle, variegated cows, (and) white pigs. Used . #1,2 (163.1)

![]() 又(有)齒于妣庚

又(有)齒于妣庚![]() 牢物牝白豕至

牢物牝白豕至![]() 一用 一二

一用 一二

(14b) … the tooth to Ancestress Geng, register pen-raised cattle, variegated cows, (and) white pigs down to one sow. Used . #1,2 (163.2)

甲戌歲祖甲牢幽廌白豭![]() 二鬯 一二三

二鬯 一二三

The results yield the following value propositions:

Pen-raised cattle > variegated cow > white boar

White pig > sow

Pen-raised cattle > dark red antelope > white boar.

It is noteworthy that pen-raised cattle and pen-raised sheep never appeared together in such a hierarchal offering list for the same ritual event. This implies an equivalent value – that either one would be used or the other. In general, male animals were listed before females of the same type and pure-coloured ones before those with differing colours or markings. Human victims, when present, always came at the top of any list, followed by pen-raised cattle or sheep, antelopes, cattle, sheep and, finally, pigs.Footnote 27 Dogs (five instances) were never combined in the HYZ OBI with any other animals and had no accompaniments, thus their relative value and utility cannot be determined. But, while they were considered comparatively lowly offerings in later periods, it is well known that they held a special role in Shang mortuary customs.

The Antelope

Prior to the HYZ discovery no useful information had been found about the role and ritual value of antelopes in the Shang ancestral cult, probably because these animals were found in the western mountains and on high plains outside the Shang cultural sphere.Footnote 28 They probably feature as an item stocked for the HYZ ancestor cult in this corpus (seventeen instances) for geographical reasons. An initial study of HYZ geography indicates high activity along the western boundary of the Shang royal domain and environs, especially in the area between Xiuwu 修武 (northwest Henan) and the Qinyang 沁陽 River in southern Shanxi. The HYZ prince did a lot of horse trading in and around this area, kept stock at a strategic location near or just inside the western border, and had social and business relations with powerful lineages. One such lineage, Cha 插, provided the prince with horses and antelopes (HYZ 467.7). A percentage of the prince’s sacrificial animal stock, particularly bovines and antelopes, was sent to the king as ‘contributions’ (38.4). In these administrative OBI, antelopes are listed ahead of bovines. Bovine deliveries are common in the OBI, whereas antelope deliveries are not.

The OBI graph ![]() is commonly transcribed as zh(a)i 廌 and identified as an antelope (lingyang 羚羊). The characteristic feature of the graph was the animal’s long U-shaped horns and striped body. Hayashi Minao used the antelope’s characteristic horns as a means to identify its taotie image in bronze art (Figure 1.9).Footnote 29 HYZ OBI describe antelope according to both their gender and colour. In sacrificial listings they appear after pen-raised bovines (HYZ 149.12) but before non-penned ones and cows (HYZ 139.6, 132.1, 38.4), showing that their value was considerable. While antelope sacrifices were not nearly as frequent as cattle, sheep or pig, the value placed on them is probably due to the fact that they had to be imported.

is commonly transcribed as zh(a)i 廌 and identified as an antelope (lingyang 羚羊). The characteristic feature of the graph was the animal’s long U-shaped horns and striped body. Hayashi Minao used the antelope’s characteristic horns as a means to identify its taotie image in bronze art (Figure 1.9).Footnote 29 HYZ OBI describe antelope according to both their gender and colour. In sacrificial listings they appear after pen-raised bovines (HYZ 149.12) but before non-penned ones and cows (HYZ 139.6, 132.1, 38.4), showing that their value was considerable. While antelope sacrifices were not nearly as frequent as cattle, sheep or pig, the value placed on them is probably due to the fact that they had to be imported.

The synchronized divination set on two separate turtle shells (HYZ 34.1 and 198.27) selectively translated below reveals insights into the complexities of divination on animal selection, and highlights the importance of getting the ritual menu right. Shang elites ate a lot of meat: three stone offering tables (each modified by a directional marker) of dark red antelope viands – the highest count ever seen in the OBI – were presented in combination with other viand offerings of cow, bull and bird meat. A hypothetical reconstruction of the context posits that several antelopes were ritually sacrificed, cut up, and presented on stone trays for a banquet organized by the prince.

辛卯卜子尊宜惠幽廌用 一

(16a) On Xinmao divined: Our lord will set out viand trays; let it be dark red antelope that is used. #1 (34.1)

辛卯卜惠口宜□![]() 牝亦惠牡用 一

牝亦惠牡用 一

(16b) On Xinmao divined: Let it be Kou’s viands … female antelope, cow; also let it be bull that is used. #1 (198.4)

壬辰卜子尊宜右左惠廌用中惠![]() 用

用

(16c) On Renchen divined: Our lord will set out the viand trays right and left; let it be antelope that is used; (for) the middle (one), let it be male antelope that is used. (198.6–7)

壬辰卜子亦尊宜惠![]() 于左右用 一

于左右用 一

(16d) On Renchen divined: Our lord will also set out viand trays; let it be male antelope for the left (and) right (one) that is used. #1 (198.8)

Odd Numbers

Shang divination on the economics and numerology of ritual offerings showed a marked preference for odd numbers of items that increased incrementally by two and stopped at ten. At that point, numbers usually increased either directly to fifteen or continued in multiples of ten, with a preference for odd multiples of ten, such as thirty and fifty. The aggregate of items for a single ritual event was often odd as well. Let me here adduce a few of the more noteworthy examples found in the HYZ OBI:

HYZ 32 is a set of four inscriptions that is notable for recording the single highest count (105) of animal offerings in the entire corpus. Each of these inscriptions started with an initial clause that proposed a fixed quantity of rams to be sacrificed. Unable to validate the first proposition, the count moved from three to five (divinations two and three) and finally to seven in the fourth.

On HYZ 401 and HYZ 286 counts of cattle and sheep, respectively, increase in similar steps of two from three to seven, then jump to ten, i.e. 3–5–7–10.

HYZ 113 proposed making animal contributions to the king in multiples of ten, starting with thirty (3 × 10) and ending at fifty (5 × 10).

Returning to HYZ 32, the odd count of 105 bovines recorded for an exorcism and the mathematical combination 10 × 10 + 5 (see also HYZ 276.4) were clearly not just arbitrary numbers. They seem to have been intentionally selected with a favourable outcome in mind and without any room for negotiation.

The number five is seen all over the inscriptional corpus. It was the item count of choice, especially for exorcism offerings and for animal sacrifices accompanying human beheadings. Consider the odd value counts of 1–5–5–1 in the following divination:

乙亥夕酒伐一[于]祖乙卯![]() 五

五![]() 五

五![]() 一鬯子肩禦往 一二三四[五]六

一鬯子肩禦往 一二三四[五]六

(17) On the evening of Yihai, make ale libation (and) behead one human [to] Ancestor Yi, cutting apart five rams, five ewes (and) offering one (measure) of aromatic ale; our lord’s shoulder exorcism will be sent off. #1,2,3,4,[5],6 (243)

This ‘odd phenomenon’ was not just confined to the offering counts in ritual contexts and the divination process but also, interestingly, and not coincidentally, to the number of animal-themed images on bronze art discussed at the beginning of this chapter. Three bovine taotie are on the Shang tripod cauldron example in Figure 1.5, and perhaps more famous are the seven bovine images on the early Western Zhou tripod cauldron known as the Bo Ju li 伯矩鬲, discovered in 1974 in Beijing Liulihe, tomb 251. Finally, odd numbers regularly appear outside ritual contexts as well. Predictions within divination statements of how long it would take to recover from illness occur several times in odd multiples and were usually estimated to be three to five days (HYZ 446 and 3.8). The phrase ‘five weeks’ appears in isolation on a complete turtle plastron and was probably related to an anticipated arrival (HYZ 112; also 266). Elsewhere, a weather divination estimated that rain would arrive in three to five days (HYZ 256.2–3).

United Colours of the Sacrifices

Colours are emphasized throughout the HYZ OBI, in relation to the material documents too. Inscriptions, which included re-carved divination cracks, were often filled with black and red pigments. Animate and inanimate items – whether sacrificial, ritual or gift giving – were regularly spoken of in terms of their colour. In some situations, colour trumped the item itself.

HYZ diviners had a predilection to divine using sacrificial animals with a certain colour.Footnote 30 White (bai 白) and black (hei 黑) were the two most common colours, and there was a definite fondness for the former, not just for sacrificial animals but for several other kinds of items, such as stones earmarked for gifts (HYZ 37.5, 193, 359). Coloured animals in the HYZ stock included white pigs and white cattle, black cows, bulls and pigs, variegated cows and dark red antelopes. Colour combinations of black and red and black and white indicate that the Shang royal family liked to colour coordinate.

I will demonstrate here four modes of how colour terms occurred in divinations on animal sacrifice. In the first mode, the animal’s colour was considered the priority and its gender was accounted for in a second divination:

甲寅歲祖甲白豭一![]() 鬯一登自西祭 一

鬯一登自西祭 一

(18a) On Jiayin, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Jia one white boar, offer one measure of aromatic ale, (and) raise up (or: let him taste) sacrificial items from the west. #1 (4.1)

甲寅歲祖甲白![]() 一 一二

一 一二

(18b) On Jiayin, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Jia one white sow. #1,2 (4.2)

The second mode focused on colour and, in doing so, de-specified the gender of the animal, although the category of the animal had presumably already been decided. The diviner, however, was still unable to get a good result. We do not know what happened thereafter.

甲子歲祖甲白豭一![]() 鬯一 一二三四五

鬯一 一二三四五

(19a) On Jiazi, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Jia one white boar (and) offer one measure of aromatic ale. #1,2,3,4,5 (459.6)

The third mode revealed a preference for colour which was abandoned when the diviner could not validate it:

乙卯卜惠白豕祖乙不用 一

(20a) On Yimao divined: Let it be white pigs (to) Ancestor Yi. Not used. #1 (37.24)

乙卯歲祖乙豭![]() 鬯一 一

鬯一 一

(20b) On Yimao, sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi some boars (and) offer one measure of aromatic ale. #1 (37.25)

The fourth and final mode turned attention to accompaniments and the anticipated psychological outcome of the sacrificial event, with the animal species, its gender and colour having already been validated:

乙巳歲祖乙白彘一又登祖乙衍(侃) 一

(21) On Yisi, to sacrifice (to) Ancestor Yi one white wild boar, there will be a (cereal) offering; Ancestor Yi will be happy. #1 (29.5)

Conclusion

A corpus-based approach to a scientifically excavated oracle bone archive such as the 1991 discovery from Huayuan zhuang East in Anyang (Henan) provides a revealing and detailed case study of life at the commencement of China’s historical period. Now firmly ensconced as one of the most important discoveries from the ancient world, these new inscriptions are one of the most synchronically unified and informative bodies of early Chinese epigraphic writing ever encountered. These material ‘princely’ documents expose us to a wealth of fresh data and greatly supplement what is known about the complex role animals played in the early development and transmission of Chinese ritual culture, scribal practice and social interaction. The majority of Shang OBI were on the topic of ancestor worship, and most worship events included sacrifice. The almost mesmerizing repetition of varying types of inventoried cows, sheep and pigs used as sacrificial items have led me to believe that an intimate connection existed between real-world sacrificial animals, bronze and stone offering vessels with animal taotie ‘images’ on them, animal bones as a medium for divination, and the act of recording these divinations in writing.