Book contents

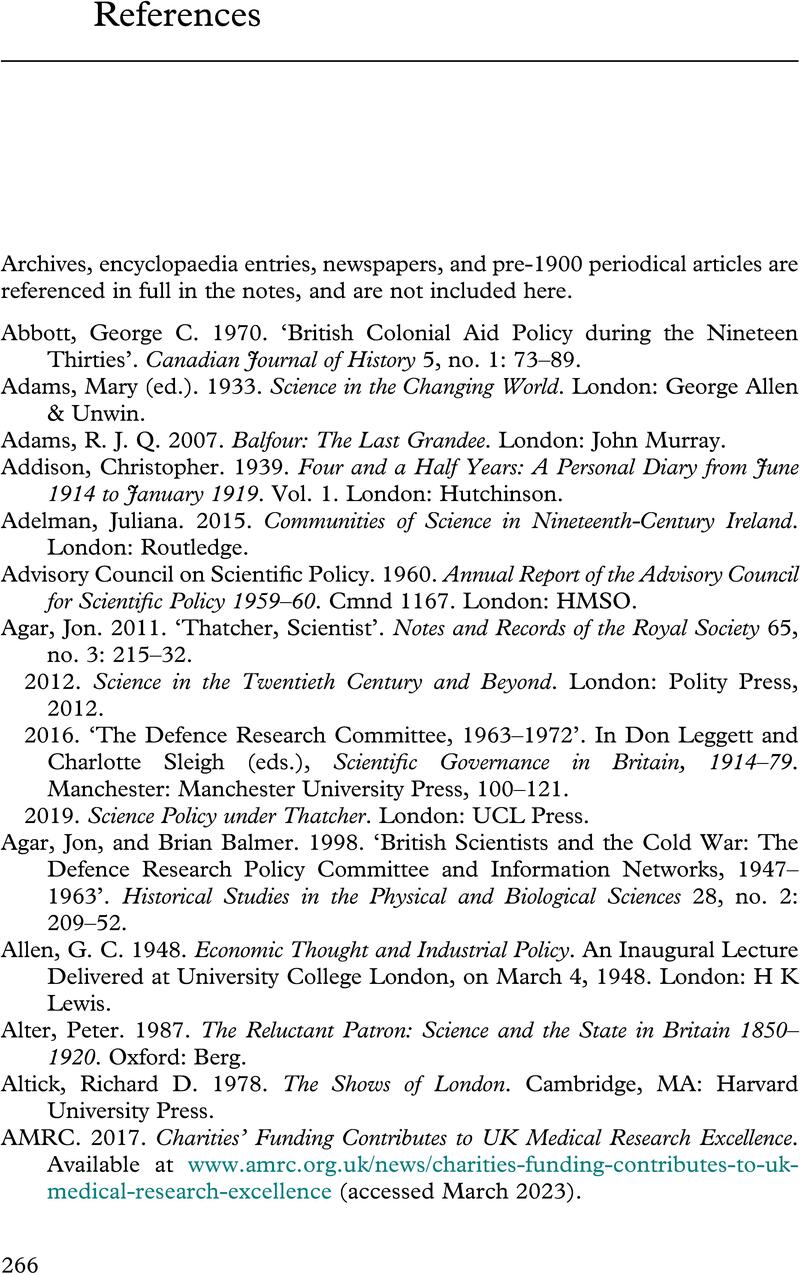

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2024

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Applied ScienceKnowledge, Modernity, and Britain's Public Realm, pp. 266 - 315Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024