Heard by a duke

Immediately after its two sentences about Mühlhausen (p. 87), the Obituary continues with:

For in the following year, 1708, a visit he made to Weimar, and the opportunity he had there to be heard before the then Duke, led to the position of Chamber- and Court-Organist being offered him, of which he took possession straightway.

Does this mean that according to what he said later, it was on a chance visit that Bach was heard by the duke? This would excuse him, or be an attempt to excuse him, for taking another job so soon, not least for the sake of readers of Walther’s Lexicon who noticed that the date of one of Bach’s jobs (1707) was strangely close to the next (1708). The Obituary’s sentence need not imply that it was on the organ, or only on the organ, that he played for the duke. By convention, the court position he was offered would necessarily include duties as ‘organist’, but these would not be exclusively in chapel or on the organ, rather those of a ‘general keyboard-player’.

There was nothing unusual in musicians visiting ducal and other courts hoping to be heard, and a gifted young organist with a good position in an important church in the Free Imperial City of Mühlhausen had much in his favour. Yet while a duke would appoint without the need to invite applications, hold auditions in public or have candidates vetted by committees, a post would not have been offered unless it was vacant or about to become so. This suggests one of two things: either that the ‘visit he made to Weimar’ was undertaken in the knowledge that the court organist Johann Effler, an old acquaintance, was near to retiring; or that in visiting Weimar in the summer of 1708, he learnt of Effler’s intentions, put himself forward as successor and was auditioned there and then by one of the dukes, the senior or the junior. It is possible he was visiting Weimar to look officially or unofficially at work on the organ (completed 16 June), even invited to do so by Effler as a fellow organist. If he did visit to see the organ, perhaps this is a hint that as an enthusiastic organist he did so more often and to more organs than is now known about.

Since it is also possible that Bach’s original return from Lüneburg was with an eye to a likely vacancy in Eisenach, something of a pattern might be observed here: he heard of or anticipated a desirable vacancy and made sure to be available. His original move as a teenager from being Laquey in Weimar to organist in Arnstadt had come about when he was inspecting a newly completed organ, somehow finding it possible to stay on as its organist. He must have made a quite exceptional impression on the authorities at each of these rather different places (Arnstadt, Mühlhausen, Weimar), combining, so one imagines, outstanding professional abilities with an obvious charismatic energy. Emanuel would not know the full story of any of his appointments or have given much thought to just how many direct and indirect family connections there were in this general neighbourhood. But not irrelevant to the Weimar appointment was that decades earlier Effler had been a colleague elsewhere of Emanuel’s grandfather Ambrosius.

Recent marriage and impending fatherhood must have made better pay desirable, and it is quite possible that Maria Barbara’s condition had prompted Bach to look to Weimar in the summer of 1708. Or there were disagreements with his pastor in Mülhausen, J. A. Frohne, a defender of Pietism (qv), on what constituted a ‘well-regulated’ ensemble music in an important church. Or there were personal tensions between the two main churches’ clergy themselves, even perhaps a particular falling out that year over a cantata for 24 June, St John’s day (Petzoldt Reference Petzoldt2000, p. 187). Or Bach did not get on well with the town’s instrumentalists and preferred a court’s music-making to that of a parish church and its ambience. ‘Chamber and court organist’ was one who participated with others in a wide musical repertory, even in the theatre if the occasion ever arose, but how expected it was that Bach should compose keyboard, instrumental and vocal music in Weimar has to be guessed. Almost certainly not as much as he did compose. But the musical potential in Weimar was higher than anything he had yet known, and it is a striking fact that for Bach, promotion and better pay never led to less work and never freed him from that inner drive to compose and perform. On the contrary.

However, it is certainly the case that Bach, like a clergyman, was called by God only to higher positions. The request for dismissal from Mühlhausen has touches of self-justification and disingenuousness, or at least of a barb or two thrown by the departed, one leaving with a better offer.

The Weimar appointment

Whatever the reasons for leaving the city of Mühlhausen, personal and professional contacts there did not cease. The Marienkirche’s archdeacon and his daughter became respectively godparents to Bach’s first two children (in Weimar), and apparently his election cantata of 1709 again had its text and music printed and available in the city (no extant copy). Also, decades later he was welcomed there when accompanying his son Johann Gottfried Bernhard on the boy’s successful application at the Marienkirche in 1735. It looks very much as if he had always had better relations in Mühlhausen with people at the Marienkirche than at his own church, allowing one to speculate not so much why he left but why so soon: church doctrine or church personnel?

But Weimar, though much smaller than Mühlhausen, was a notable German ‘residence city’, seat of an absolute ruler, a domain that was subject less to powerful clergy and elected officials and more to the will of the reigning dukes. In Weimar’s case, the ‘Red Castle’ of the reigning duke, with the court chapel and Festsaal (banqueting hall), was supplemented by the ‘Yellow Castle’ of his half-brother, both of whom soon supplied Bach with a harpsichord (Dok. II, p. 41). So Bach could call on at least three locations for music-making. It was a city in whose cultural life music featured high, judging by a succession of eminent musicians who had worked there: Melchior Vulpius, Johann Schein, Heinrich Schütz (for a short time) and J. G. Walther. (Much later in Weimar, Bach seems to have been largely forgotten. George Eliot, who stayed there in the 1850s and wrote a long account of the city, makes no mention of him.)

Having ‘the opportunity to be heard by the duke’ in Weimar, probably not in the town church but in the duke’s castle, sounds as if Bach was suing for patronage. When the child Handel had been ‘heard’ by a duke as he played, it was probably on the spectacular organ in the duke’s palace chapel of Weissenfels, and as with Bach in Weimar, this was a story presumably told by the composer himself in later years. Clearly, it was a standard way of obtaining a ruler’s attention, in Handel’s case not yet for a job but for patronage or sponsorship. J. P. Kellner, an important copyist of Bach manuscripts in the mid-1720s, and probably a friend rather than a pupil, reports in his autobiography of similarly being heard by several princes ‘on command’ while he was still at student age, presumably having sought their interest first. Interestingly, although Louis Marchand said he had ‘the honour to be heard’ by the king of France, and consequently dedicated his Premier Livre to him in 1702, he still had six years to wait for royal appointment – interesting, because this foreshadows the several years Bach had to wait for royal appointment at Dresden in the 1730s.

At Weimar, the duke must have acted fast, as he was entitled to do, for by 20 June Bach’s salary was approved and he was paid as for the second quarter of 1708, at a rate nearly double that at Mühlhausen. An annual allowance of corn (18 bushels), barley (12), firewood and beer (plus freedom from alcohol excise) was additional, as was an initial grant for ‘procuring his furniture’ (Dok. V, pp. 113f.). Surely Bach had bargained for all this. On 14 July, also perhaps at his request, on entering service he received a sum of 10 guilders ex gratia. The phrase is used in connection with payment zum Anzugs-Gelde (‘for clothing money’: Dok. II, p. 35), i.e. he had to acquire court dress. So Bach wore uniform. His rôle in the chapel music has not been established in detail, but it is likely to have been modest, surely in line generally with the Weimar Church Regulation of 1664 which required the organist not to play too long before the chorales or ensemble music, and to observe a proper musical gravity (BJ 2006, p. 40). As at any court, hiring and firing of employees was not an open process, and the duke’s appointment specifies little more than terms of salary, including the payments in kind. But as for good behaviour and obedience: a duke had no need to specify.

The payment of 14 July 1708 implies that by then the Bachs (Maria Barbara pregnant with Catharina Dorothea) were resident in Weimar, and also that Bach’s successor in Mühlhausen was already in place. The new ‘chamber and court organist’ of Weimar was much better paid than most parish-church organists and indeed better than his predecessors at the court, with a substantial salary rise in 1711 and another on promotion in March 1714, surely a result of his importuning. There were also additional miscellaneous fees for extra events, for keeping the harpsichords in order (at least, in the earlier years), teaching Clavier to the duke’s page, and for engagements beyond Weimar (organ-testing in Taubach, visits to Weissenfels and probably elsewhere). Such a position could also lead to the acquiring of students, as it did. The Bachs seem to have lived in a house owned by a fellow court-musician, at least until 1713, and it will be remembered that already by March 1709, perhaps from July 1708, Maria Barbara’s sister Friedelena had been living with them.

In the professional sphere, one particularly kindred spirit (so one might guess) to visit Bach early on in Weimar was the violinist J. G. Pisendel, composer of some solo violin music, the details of whose influence on Bach one would very much like to know. There may also have been good contact with Telemann, then working in Eisenach and, as we might now say, tirelessly networking. Emanuel said that ‘in his young years’ his father was ‘often together with Telemann’ (Dok. III, p. 289), though whether this means already in Eisenach is unclear. Perhaps he meant Bach’s early twenties in Weimar, even possibly hinting that they were less ‘together’ later. Whatever the case, from Telemann’s music Bach could have continued to learn for decades what was fashionable in the musical world, both new conceptions (such as arias in 2/4 time) and newer genres (the scherzo movement, the affettuoso movement). Quite what Bach thought of the rather flabby lines of Telemann’s Concerto in G for two violins when he made his copy of it in 1709 (apparently with and for Pisendel) is unrecorded, but it does bring together three gifted musicians much affected, one can safely assume, by the dazzling new Italian styles. It was some such interest that also led at Weimar to the arrangement of yet another Telemann concerto, BWV 985, now with a connection to Prince Johann Ernst, the younger duke’s young half-brother and a composer of whom more needs to be said below.

Already resident in Weimar from a year previously was Bach’s distant relative J. G. Walther, teacher of one of the scions of the ducal house (the same Prince Johann Ernst) and organist of the town church, the church to whose parish the young Bach family probably belonged. Why Walther rather than Bach taught the young prince is unknown but may have been the result of tensions in the ducal family: Prince Johann Ernst was a member of the junior family, not the reigning duke’s, assumed to be Bach’s employer. In his later twenties Bach came to stand as godfather to a son of Walther (1712), of his own brother Christoph (1713), of the court organ-builder H. N. Trebs (1713) and of a musical colleague in Weissenfels (A. I. Weldig, master of the pages, and one of Emanuel’s godfathers, 1714). Meanwhile Maria Barbara was to stand for the daughters of a Weimar court trumpeter and of Sebastian’s pupil J. G. Ziegler. The range of godparents for Bach’s own children, three each, implies an active circle of acquaintance in the town and the province, whatever rôle godparents played in practice.

Although by 1708 Maria Barbara had her own box-pew in the nave of the duke’s chapel, behind the capellmeister’s wife, the family may also have had a pew in the town church where its baptisms took place, from Catharina Dorothea (1708) onwards, including those of Friedemann and Emanuel. A close connection between Weimar’s two organists Bach and Walther can be guessed from the interest they shared in certain techniques of composition, in which Bach’s greater adventurousness is self-evident. One interest was in using little patterns of notes to embellish the chorales, the so-called figurae in use for decades by German organists and now systematically applied by both composers. Another was working on ways to set Advent and Christmas melodies in canon, the extant examples of which even suggest a rivalry between the two composers. They also shared an interest in certain French keyboard music, both of them making copies of Dieupart’s Suittes de Clavessin and de Grigny’s Livre d’orgue. Doubtless less self-reliant than his cousin, Walther seems to have been a much more prolific copyist of other people’s organ music than Bach – though one cannot be totally sure of this – and preserved a great deal of it.

A big question is whether Bach, in his years as a regular organist before 1717, copied the work of other organists more than he is known from surviving manuscripts to have done. Even his own copious output as a composer cannot have covered every requirement, so the possibilities are that he improvised or repeated a good deal, and that he copied other composers’ music, German or French, more than we know. If he did not, was it because he rejected it? If he did and used it in chapel (something he was unlikely to do with the French music he know), did it disappear along with other chapel music when eventually he left Weimar, probably in some haste?

On the chapel itself, see below, p. 118.

Early years in Weimar

His gracious lord’s delight in his playing fired him to attempt everything possible in the art of how to treat the organ [Kunst die Orgel zu handhaben].

Very little is documented of the first five years at Weimar, and a fair assumption is that they, Bach’s mid-twenties, were very much taken up with keyboard activities: playing, teaching, composing, inaugurating (a small organ in nearby Taubach, 1710), involving harpsichord as much as organ, if not more. It would be strange if Taubach was the only organ he inaugurated at that period. But when the Obituary goes on to say that here in Weimar he also wrote most of his pieces for organ at least two questions arise. Did Emanuel overstate, affected by his father’s spoken enthusiasm for what had been his last position as a regular organist? Or did he know (or think) that his major works apparently written later derived from versions already composed in Weimar? Both could be the case, the second more significant musically.

For any composer, increasing familiarity with foreign keyboard music leavens the standard fare of local consumption, and Bach can have been no exception in this respect. All the more unfortunate, therefore, is that the earliest known choral-ensemble music of his Weimar period, i.e. the second and possibly third election cantata for his old community in Mühlhausen, has not survived, since it might show how far ‘beyond Buxtehude’ he was beginning to move by now. Whether a visit to the Gotha Court at some point in 1711 (Dok. V, p. 273) was for more than advising on the organ is not known, but if the outstanding ‘Hunt Cantata’, BWV 208, was performed for the Duke of Weissenfels’s birthday in 1713, not only had musical understanding grown exponentially in five years but his renown had already spread, apparently beyond Thuringia. This is suggested by one pupil, P. D. Kräuter, coming from far-away Augsburg in the same year to study with him. (For BWV 208 and Kräuter, see further below.)

There must be several reasons why the Obituary emphasizes the organ, almost to the detriment of any vocal works there were, few or none of which Emanuel knew unless they were revised later. For one thing, by the 1750s the music for organ was in wider circulation than most other music of Bach including the cantatas and Passions, and by then the harpsichord, chamber and vocal music of 1715 had been largely superseded. But the very uniqueness of the bigger organ pieces impressed itself on writers whose own period produced nothing comparable. The result is that the Obituary authors knew little of what was composed at Weimar. When it was composed is another big question: much organ and harpsichord music is dated today on the basis of how far it appears to have developed beyond provincial compositions of c. 1700. But such reasoning could be circular for a composer who accumulated and rethought.

By ‘His gracious lord’, it is not clear which of the two Weimar dukes Emanuel is referring to, Wilhelm Ernst the senior or Ernst August the junior (his nephew), and perhaps he was uncertain himself. The former was the controlling authority of funds and personnel, as events were to prove, but in 1775 Emanuel cited the latter as having particularly supported his father (Dok. III, p. 289). It was also Ernst August’s own father who had employed Bach for a time in 1703, as part of building up a musical establishment, and it was his own younger half-brother Prince Johann Ernst whose string concertos are found among Bach’s transcriptions. But whichever duke it was that Bach impressed, Emanuel is silent on one intractable problem of life in Weimar: the two dukes lived in such mutual enmity and territorial rivalry as would inevitably involve the musicians one way or another, leaving those favoured by one to be discriminated against by the other. There are few signs that the atmosphere was easy.

The situation gives some idea of life in an absolutist ruler’s court. Shortly before Bach’s arrival, the senior duke had decreed that his cappella musicians were not to play in the junior duke’s residence without his permission, on pain of a fine and incarceration (Glöckner Reference Glöckner, Hoffmann and Schneiderheinze1988, p. 137). The decree was re-issued two years after Bach’s departure, presumably because it had been defied – by Bach himself? – and by then the conditions were stricter: the musicians were not even allowed to discuss the matter. In response, the junior duke tried to compel them to choose to be his retainers as well, failing which they would forfeit any payments they (like Bach) had had from him, a forfeit which he would pursue through their children and children’s children. Although by then Bach was not involved, such nasty conditions throw some light on another, much later event, namely, his own incarceration in 1717 and release a month later. They also raise questions about other contacts he had made in 1713, at Weissenfels (probably a visit) and later the same year at Halle (certainly a visit), this latter for the vacant organist’s post. Five years after appointment at Weimar, he was looking to leave?

If, at about the time he became court musician to one or other Weimar duke, Bach was producing the organ Passacaglia, not only was his ability to create harmonic tension maturing but so must have been his organ-playing. So they were if, similarly, he was soon to begin to create the types of chorale now familiar from the album later called Orgelbüchlein (see below). On such ‘ifs’ hang a whole interpretation of the composer’s development, not least as a player. Specifically, the technical demands of many organ works are taxing beyond norms of the day, setting him on the path to the Six Sonatas for Organ twenty years later, and justifying the Obituary’s remark at the top of this section. While the Orgelbüchlein chorales and the later sonatas are both remarkably succinct, interesting work was also done towards creating much longer pieces, as with the Passacaglia. Spacious treatment, even when the pre-laid harmonic plan of a chorale is treated at great length, can result in more than mere length: the long Variation 10 of the chorale variations ‘Sei gegrüsset’, BWV 768, already achieves a new and convincing coherence. For Bach, success in creating both unusually succinct and unusually extended music remained a recurrent aim: he could do both length and brevity.

When engaged as organ-examiner, at Arnstadt in 1703, Langewiesen in 1706, Mühlhausen in 1709 (?), Taubach 1710, Halle 1716, Erfurt Augustinerkirche 1716, Leipzig University Church 1717 (the last three major organs), Bach may customarily have played a public concert of his grander works, various praeludia or Fantasien and longer chorale-settings. (At Halle, it is not known which of the organists present played before or after the sermon when the special new organ was inaugurated, whether it was one of the three examiners including Bach or the newly appointed organist Kirchhoff. Perhaps all four (Dok. II, p. 60).) A probable reason why the dating and purpose of Bach’s bigger organ works are such guesswork is that some were portfolio works selected and revised as such occasions required or as studied by qualified students. ‘Occasions’ would include inaugurations and demonstrations as well as lessons, and it can be misleading to pin down the dates of so many keyboard works of Bach: the works themselves were not fixtures even when gathered into a collection, as gradually happened now and then.

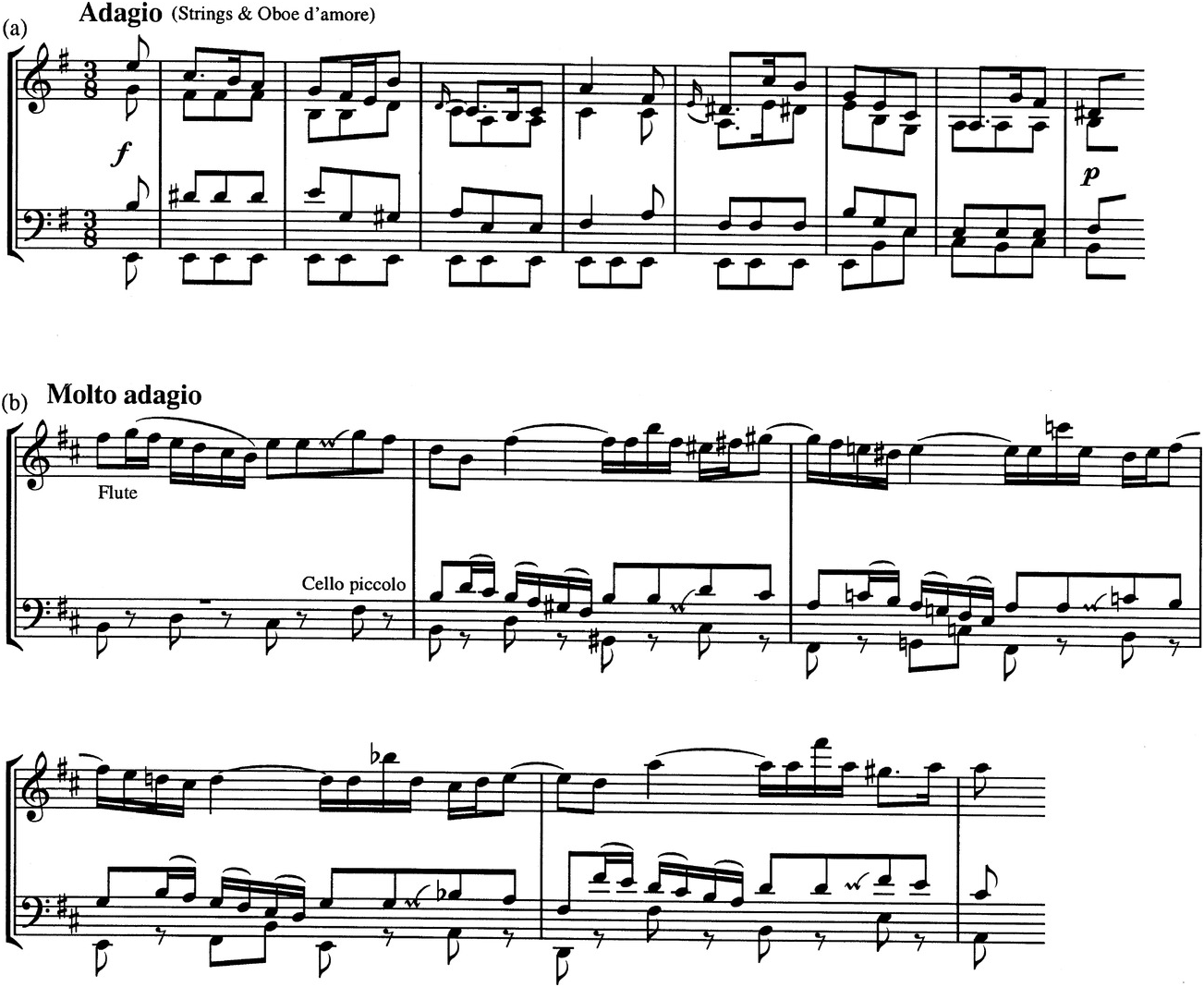

The Obituary’s emphasis here on the organ is one-sided. Given that Bach had virtuoso ability as an organist and explored certain kinds of organ music farther than any predecessor, and given that he continued to do so even as cantor and no longer a regular organist, it is still puzzling that neither part of the Obituary, Emanuel’s or Agricola’s, acknowledges the strides he also took in chamber and harpsichord music during the Weimar years. At Leipzig, did he never speak of having taken a leading part in the duke’s concert life? Learning ‘how to treat the organ’ sounds like the composer’s own phrase when later describing his priorities at that period. It implies that he was also imitating other kinds of music on the organ, composing chorales like chamber trios and fugues like concertos. Emanuel would know the extraordinary range between a chorale of 8 bars in the Orgelbüchlein (BWV 631) and a big toccata of more than 400 (the F major, BWV 540), and would find in works such as these a clear demonstration of ‘how to treat the organ’.

With the duke’s approval and at his cost, the chapel organ was being improved and enlarged over several years, and was in and out of commission over 1707–9 and again from June 1712 to May 1714 (Schrammek Reference Schrammek, Hoffmann and Schneiderheinze1988). The instrument could never become very grand, placed where it was, and its sound must always have been somewhat indirect in the chapel, if not actually dull or indistinct. For it was located at the back of an attic chamber above the chapel ceiling through which a balustraded opening of 4 by 3 metres admitted sight and sound, 20 metres above the chapel floor. Through this opening the organ, just visible, spoke down into the rectangular chapel below, as if from on high. For its services, the chapel, which was some 30 metres long and 12 wide, was occupied on the ground floor and two running galleries not by a parish-congregation but by court personnel, who looked towards the liturgical east end at an altar structure that was itself not unlike a stage-set or scena. This consisted of (in vertical order) step, altar rail, altar table, baldacchino, pulpit, a decorated obelisk pointing up to ‘heaven’s castle’, then the attic chamber balustrade. This chamber had a narrow space for performers and some way at the back of it the organ, with a ‘heavenly’ fresco on the plaster dome above. Although documentary reference to certain seats built in this attic conveys a picture of singers and instrumentalists stationed there during services or rehearsals, whether they always performed from on high in this way and more or less out of sight is open to doubt.

The organ, glimpsed at the top of the scena or ‘path to heaven’ (Weg zur Himmelsburg), had its back against the wall, with bass pipes and bellows-chamber at the very back. In 1658 it had one manual only, which probably was all that could be accommodated comfortably in a restricted space; but then a second was added, its pipe-chest placed to the side and played presumably with a complicated action that might never have worked very well. Shortly before Bach was appointed, an improvement was made by relocating this side-chest under the main pipe-chest. How room was made for this is hard to guess, but it probably made further work of improvement inevitable; this was done during Bach’s term of office and resulted in an enlarged chamber being constructed behind, presumably at his urging. A row of tuned bells was also made (probably positioned just behind the music-desk and played from the manual), and the whole organ now comprised about two dozen stops: not a great inspiration, barely more than adequate for realizing new ideas in organ music, but useful none the less. Quite why Bach thought, as it seems he did, that a row of bells was necessary (acquired at some cost from Nuremberg) is not explained, and one can only assume that they sounded at certain jolly moments, during chorales at Christmas and other festive times. An organist writing in 1742 specifically mentions the young Bach having a Glockenspiel or row of bells installed earlier at Mühlhausen (Dok. II, p. 405).

The duke may have ‘fired him up’ (feuerte ihn an) but many a court organist strove to please, and in Bach’s case there must also have been an extraordinary creative urge and practical ability matched by curiosity and industry. Fortunately for this new range of musical styles, it seems that his predecessor Effler preferred a more modern organ-tuning than elsewhere (BJ 2004, pp. 160–1), which might explain the appearance of the keys F minor and E flat major for chorales in the Orgelbüchlein. The tangible result of the duke’s support was that the organ music produced by Bach surveys a range of styles wider and on a bigger scale than had ever been achieved before by any organist in any European tradition, offering every subsequent composer a model to emulate as best he can. The Obituary authors surely realized this. After all, there is an important possibility to bear in mind here: that the first music Bach developed beyond precedents was not so much that for voices, strings or harpsichord but for the church organ.

The Obituary’s gracious acknowledgement of the duke’s support may have had another purpose: it was of a kind that Bach was not to receive later in Leipzig. But what purpose his organ music had at Weimar is not as clear as is often assumed, whether for voluntaries before and after the service or as items for private ducal concerts. Or as brilliant music shown off by a star employee for the duke’s noble visitors? A ruler of such known piety as the Duke of Weimar might well take pleasure in special organ music being played in his chapel by a gifted and well-paid employee, although compared to other court chapels in that part of the world (Eisenberg, Saalfeld, Sangerhausen, Weissenfels) the Weimar chapel and its organ were not the most spectacular. Whether the organist played after the services as the congregation retired is uncertain, but if he did, there was a choice of toccatas, fugues, concerto- transcriptions and improvisations as well as exceptional mixed genres such as a grand ritornello Fantasia on the Whitsuntide hymn, BWV 651a. By now pieces such as these had become genuine organ works, no longer suitable for other keyboard instruments.

To what extent the works as we know them represent the composer’s improvisations is not clear from the Obituary’s phrase ‘everything possible in the art of how to treat the organ’. Certainly Bach was expanding the repertory by absorbing other kinds of music such as sonatas and concertos, as he was also expanding styles in the cantatas, and such music would come about only after thoughtful deliberation. But how he improvised can be only hesitantly traced from surviving examples: first, in fantasias and toccatas, with their various runs, arpeggios, stopping and starting, clear cadences, distant modulations, moments of free recitative, etc; and secondly, in fugues, with moments of contrapuntal imitation interspersing freer episodes based as often as not on broken chords. A work such as the ubiquitous ‘Toccata and Fugue in D minor for Organ’, BWV 565, might give an idea of what some organists throughout the eighteenth century could improvise with thin harmonies, a few rhetorical gestures, dramatic pauses, simple shape, much repetition and virtually no counterpoint. But far too much is doubtful about the authenticity of this piece for it to have anything reliable to say about the young organist J. S. Bach.

Although it is clear that Bach did develop organ toccatas into big, subtle, fully worked concerto-like movements (C major, BWV 564.i; F major, BWV 540.i), the steps in this evolution are also hard to trace. As already suggested, early compositions or creative adaptations such as the Albinoni fugues are as likely to have been revised, rewritten and transmitted in various states; and this is true of some of the later big preludes and fugues. How unusual Bach’s practice was in this aspect is impossible to know, since no comparable fund of sources exists for any other composer. But not all versions now known are likely to go back in all their details to Bach himself, and few are likely to be the only ones that ever existed. The ‘Fantasia in G major’, BWV 572, could represent the kind of music that Bach improvised in his late twenties or early thirties, indeed for the delight of his duke in Weimar, either on organ or on harpsichord, and attaching it to one or more other movements. But many works are so original that there are few clear criteria for dating them: the G major Praeludium, BWV 541, which begins like an improvisation but couples two highly organized ritornello movements, could have originated many years before the composer made a copy of it in the 1730s, with or without its known fugue. Evolution of a genre is not reliably traced when it is as isolated as Bach’s ‘free’ organ works are, individually structured like string concertos but otherwise unlike them and unlike each other.

A down-to-earth question is how often Bach paired a prelude with a fugue to make a complementary pair, either on paper or in performance. This was almost certainly less often than supposed by anyone who relies on later editions or who has the completed WTC in mind, as all subsequent editors and players of the music have. But the earliest known versions of many WTC preludes did not accompany fugues either, and not even in WTC did the composer actually label them Prelude & Fugue (see p. 237). Nevertheless, once the idea of a pair became familiar from publications by J. K. F. Fischer and others, pairing must have seemed natural, particularly when the prelude was short and preceded a substantial fugue, as it did not always do. Prelude-and-fugue pairing is also there in vocal works early (Cantata No. 131) and late (Kyrie of the ‘B minor Mass’), as it is in the harpsichord works of Clavierübung I, II and ‘IV’. A fugue does not have to be ‘bigger’ than its prelude – it rarely is later in the WTC1 and WTC2 – and it could be that some couplings of doubtful authenticity result from someone else attaching a fugue to a free-standing prelude.

That Bach was constantly, so to speak endlessly, curious is suggested by music of other kinds he became acquainted with during his earlier Weimar years, making a most important item in his biography and output. Concertos of Albinoni (Op. 2, published 1700) and Telemann (Concerto in G, copy c. 1709) are certain, but often over his middle years one can only infer what he knew, such as one or other edition of Corelli’s violin sonatas, Op. V. While these are a worthy model for any musician, the musical quality of some other items varies, suggesting that Bach’s self-teaching was serendipitous and eclectic. He came to own copies of at least three important organ publications originating far from Weimar: the volumes of Ammerbach’s Tabulaturbuch (Leipzig, 1571), Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali (Venice, 1635) and his manuscript of de Grigny’s Livre d’orgue (Paris, c. 1700). He appears to have possessed at least three exemplars, possibly more, of the Ammerbach, either paying homage to a Leipzig predecessor or investing in them to sell to visitors. Their antiquarian value was high, being the first printed volume of keyboard music in Germany, an example of tablature, published by the then organist of St Thomas. A note, probably autograph, on one copy said that it cost one gold louis d’or (Dok. I, p. 269), a very large sum. By the eighteenth century, however, Ammerbach’s actual musical influence had dwindled.

As for Frescobaldi, discriminating composers must always have recognized his quality. In Dresden, J. D. Zelenka also had a manuscript copy of the Fiori musicali dated 1718 (Beisswenger Reference Beisswenger1992, p. 285), while in Hamburg Reinken is known to have been familiar with a book of Frescobaldi toccatas. Exactly how Bach got to know the de Grigny and (two or three years later) the Frescobaldi publications is a guess, probably through J. G. Walther who habitually corresponded with other musicians. His own copies of the de Grigny and Dieupart books were perhaps a little later than Bach’s but surely suggest a shared interest. While Frescobaldi continued to influence Bach’s counterpoint into his maturity, de Grigny’s manner of writing for the organ is less in evidence. Did copying not lead him to grasp the beauty of the French styles, especially the lyrical solos for the left hand – the en taille solos? These can be occasionally glimpsed, as in the Weimar organ-chorale BWV 663a, but Bach seems never to have composed fully in this way, perhaps finding its peculiar lyricism too indulgent for Lutheran chorales, Lutheran organists, Lutheran congregations. One thing seems likely: the exceptionally high musical quality of Frescobaldi’s and de Grigny’s books was recognized by Bach and they were even more carefully preserved than usual.

Some full-length organ-chorales from these years took in an unusual range of styles, confirming that Bach, though a Lutheran organist, did absorb much non-Lutheran music that he came across in Weimar. De Grigny, for instance, gave him practical examples of writing richer harmony by adding a fifth part to the usual four, something found then in certain chorales and cantatas. Dance-types were also adapted for chorales, either because they were familiar to German organists already or because (in Bach’s case) André Raison referred to them in his Livre d’orgue of 1688. The very length of one Weimar chorale, ‘Schmücke dich’, BWV 654a, a work fittingly enthused over by Schumann a century later, enables the composer to amalgamate two very different genres: a true-to-life sarabande and an organist’s typical setting of the hymn line by line according to tradition. The result is continuous and tuneful. A gigue, on the other hand, has to be tempered when the chorale is for Communion (BWV 666a) but can be extrovert for Whit Sunday (the astonishing ‘Komm, Gott Schöpfer’, BWV 667a). The large scale of such organ-chorales, even before later revision in the Leipzig years, is also a feature of the recently discovered chorale BWV 1128, as if it were Bach’s ‘answer’ to the kind of long fantasia beloved by organists in the north.

If it is less certain than usually thought quite how the organ-chorales were actually used, how much more is this so for the harpsichord toccatas! Although five or so of these are now known in disparate copies, the Obituary lists Six Toccatas as if speaking of a fixed set. (A lost set known to Emanuel and intended for publication?) Copies of two of them, BWV 913 and 914, had already been made by 1708 or 1709, so shortly after the move to Weimar, and possibly for or by a new student. The Toccatas’ sections appear to follow the structures of earlier German organ toccatas, familiar in the Weimar chapel perhaps, and in which free virtuoso passages are interspersed between sections more in the style of sonata movements. Each section is characteristically ‘thorough’, exploring its themes with felicitous harmony and taking an evident pleasure in perfect cadences. If the counterpoint is still somewhat hidebound, there are flashes of melody elsewhere in which one might fancy the influence of Georg Böhm. Despite the traditional repetitions and short phrases in these toccatas, there are increasing signs of the maturing composer’s grasp of sustained length, of harmonic movement and of what works well on the keyboard.

Cantatas in Weimar, 1

Tracing step by step Bach’s experience with vocal works before his promotion at Weimar in March 1714 (see p. 155) is not possible, though there are some pointers. In Cantata No. 196 (see above, p. 67) the young composer had not gone much beyond imitating choral works by Weckmann and others he could have heard in Hamburg or Lübeck. But this might reflect the fact that a display of old-fashioned permutation counterpoint is not inappropriate for the text of No. 196, a formal Old Testament benediction from Psalm 115; see Example 7 on p. 131. Not for the only time, guessing which of two accomplished but disparate Bach works was the earlier (the Passacaglia or Cantata No. 196) cannot be based on simple comparison: they are too different in genre and purpose.

An area explored during at least the later Weimar years was the copies Bach made (or had made) of choral works, including Latin works, chiefly old-style Kyries, by Roman Catholic composers not now well known, such as J. Baal, F. B. Conti, M. G. Peranda, J. C. Pez (from the Missa San Lamberti, Augsburg, 1706) and J. C. Schmidt. Whether these were for private study or for occasional performance in the Weimar chapel is not clear from documents, although some separate performing parts make it possible that Kyries (often sung in major Lutheran churches) were intended for it. Bach and Walther shared an interest in Palestrina and the stile antico (qv) of old Latin vocal music, but again, whether the known copies of Palestrina’s original printed parts were made in order for singing in a service (unlikely), in informal performances (possibly) or in contrapuntal studies (probably) is not established. Judging by the accidentals consistently added at some stage to Peranda’s and particularly Palestrina’s modal lines, someone was interested in modernizing this music for modern performance, either in Weimar or in Weissenfels. At this period in Weissenfels, J. P. Krieger had a collection of the very works known in Weimar (BJ 2013, p. 85).

An assumption has been that Bach made use of the Weimar Palestrina copies later for performance in Leipzig. But used in this way or not, such vocal music was to be studied for much the same reason that it was studied in twentieth-century British universities: as a model for contrapuntal work, to learn the nature of intervals, to absorb the art of good part-writing and so forth. Its usefulness as a foundation to such a composer of keyboard music as Bach is also clear from many a fugue of his over the years to come. On the other hand, the cantatas from the Weimar years rarely allude patently to this old contrapuntal style, just occasionally (a countersubject in Cantata No. 54.iii). Characteristics of the style emerge much more often in the later cantatas for the Thomaskirche, Leipzig, suggesting that earlier in Weimar, for the solo singers of the duke’s chapel or because the dukes had other tastes, Bach was deliberately turning away there from the stile antico.

How unusual such copying of imported choral music was is difficult to know, for some of it survives because it has Bach’s name or writing on it. But other acquaintances also copied out French keyboard music. The young prince himself was to compose concertos imitating Vivaldi with a musical competence rare, perhaps unique, for a teenage nobleman. In the same way, one can assume that many details in the arias and recitatives in the Weimar cantatas were due to exposure to other kinds of up-to-date music in a cultured court, even the court of a duke anxious to observe his religious obligations by standardizing the duchy’s hymnbooks. This he did by means of the published Weimar Gesangbuch of 1713. In March 1714, the very month Bach became concertmeister and began a series of cantatas, the chapel accounts include the cost of five blackboards on which the hymn-numbers were to be announced (Jauernig Reference Jauernig, Besseler and Kraft1950, p. 71). The two genres, chorales sung by the congregation and chorales sung by professional soloists, remained quite separate in their musical language.

Bach’s original position of ‘chamber musician’ indicated duties in the general music-making at court and as member of a cappella of fourteen musicians, to whom were added a pool of seven trumpeters and timpanist as occasion required. Whether duties included playing harpsichord solos in court concerts is not documented, nor indeed whether solo harpsichord-playing was known at all to audiences bigger than a select few. Nor is it known precisely what the ensemble works were in which he presumably did participate: solo instrumental sonatas (playing continuo with violin, gamba, recorder or oboe soloists), string trios, mixed trios and broken consort music for wind, strings and keyboard (those works the Italians called concerti). One can suppose that it would have taken some years for all these activities to flourish.

A particular unanswered question is whether the set of parts Bach himself seems to have copied for an anonymous setting of the St Mark Passion a few years into his Weimar job (a work attributed variously to the northerners R. Keiser and F. N. Brauns) was made for performance in the chapel, or indeed anywhere else. If this had happened or was meant to happen, it would have probably been his largest performance to date, though in a chamber setting for a few performers: SATB, two violins, two violas, oboe and harpsichord. There were some new movements added (recitative, a prelude and fugue for instruments, two bicinia), the work of a still-young composer using and adding to music from elsewhere, interested in ways to write for voices and instruments and making a new, whole piece for local performance. This was a procedure also familiar to Handel. Bach’s copy is the only surviving manuscript of the work, which he revived twice in Leipzig, and is an example of what could well have been a common activity for him in Weimar.

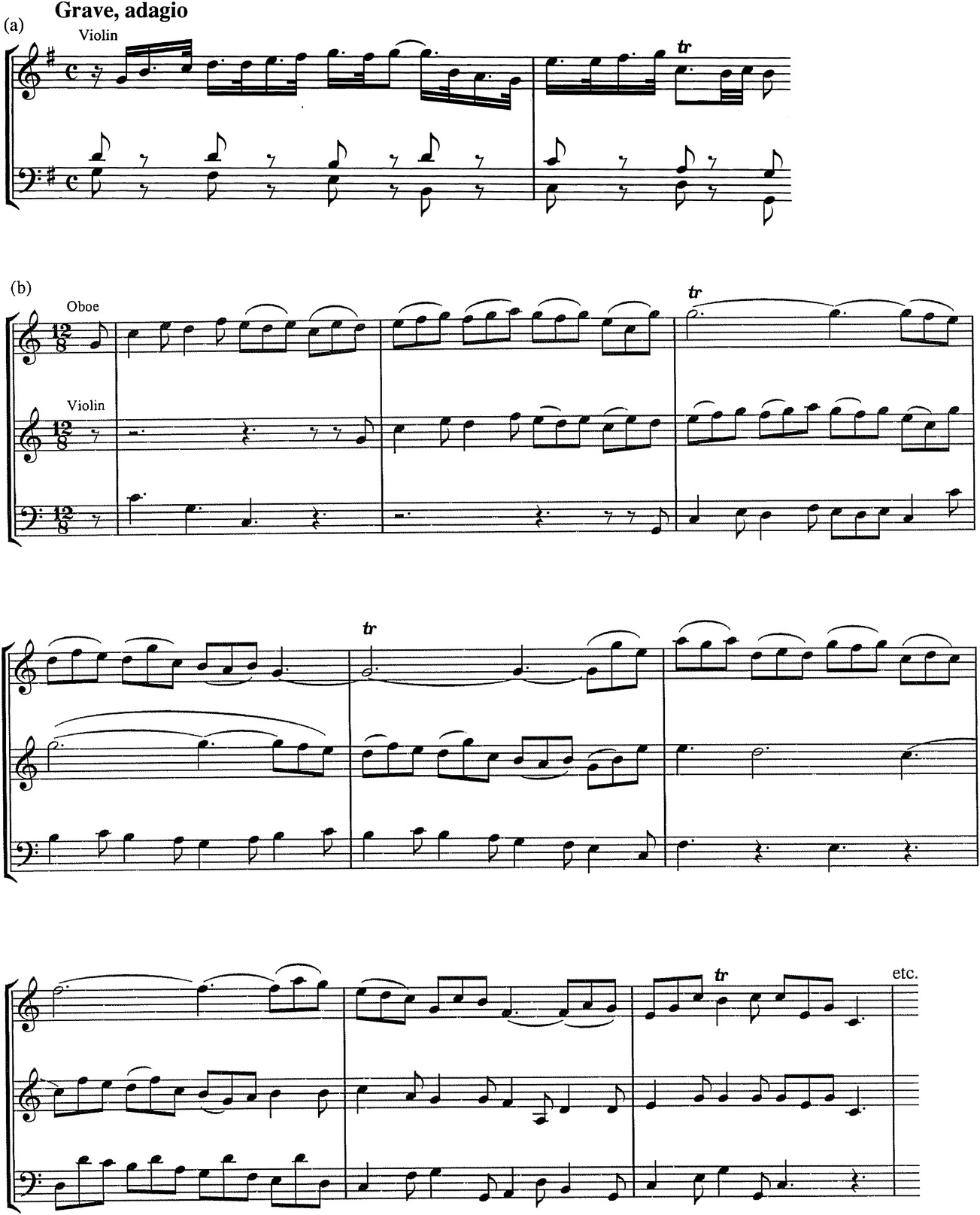

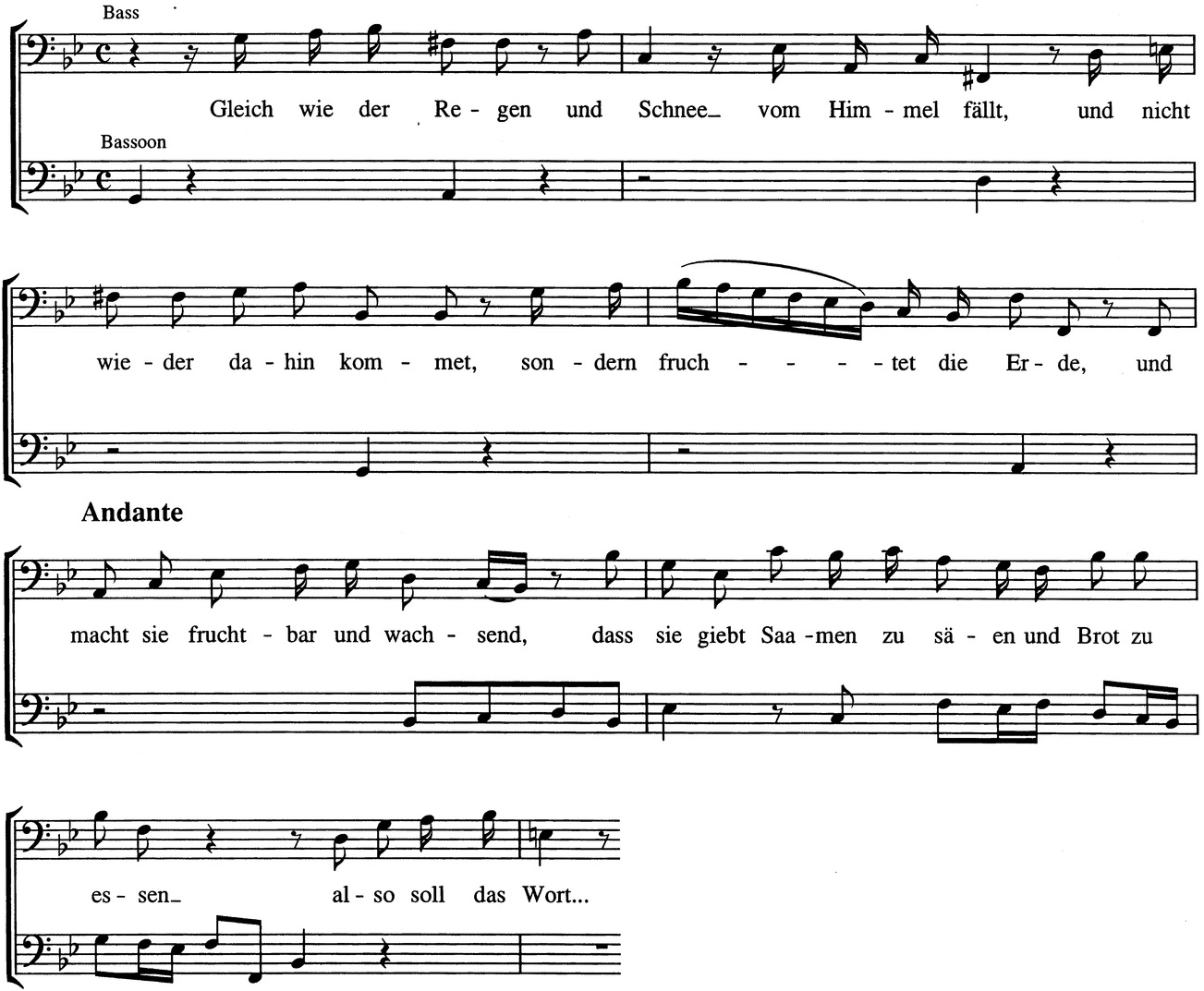

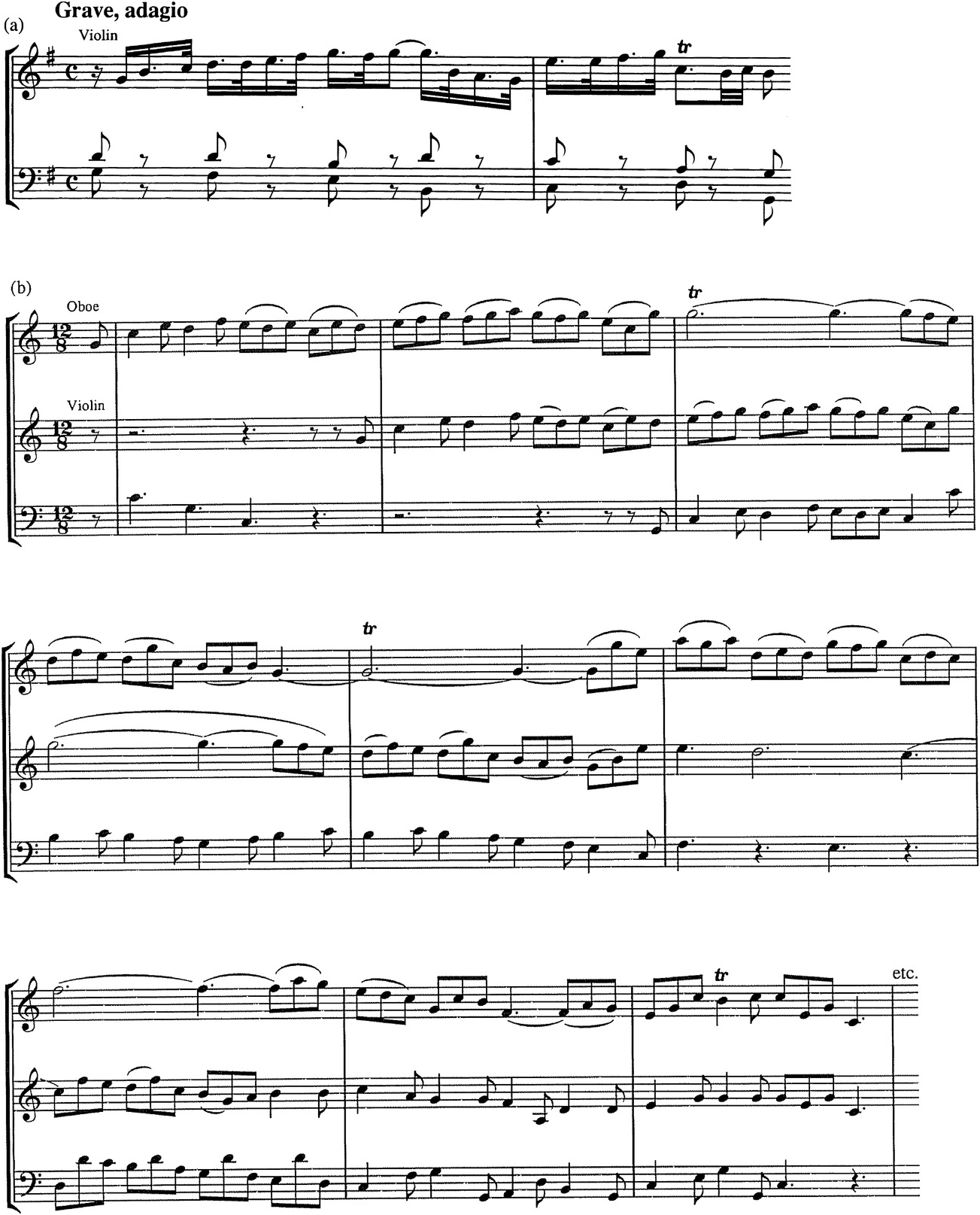

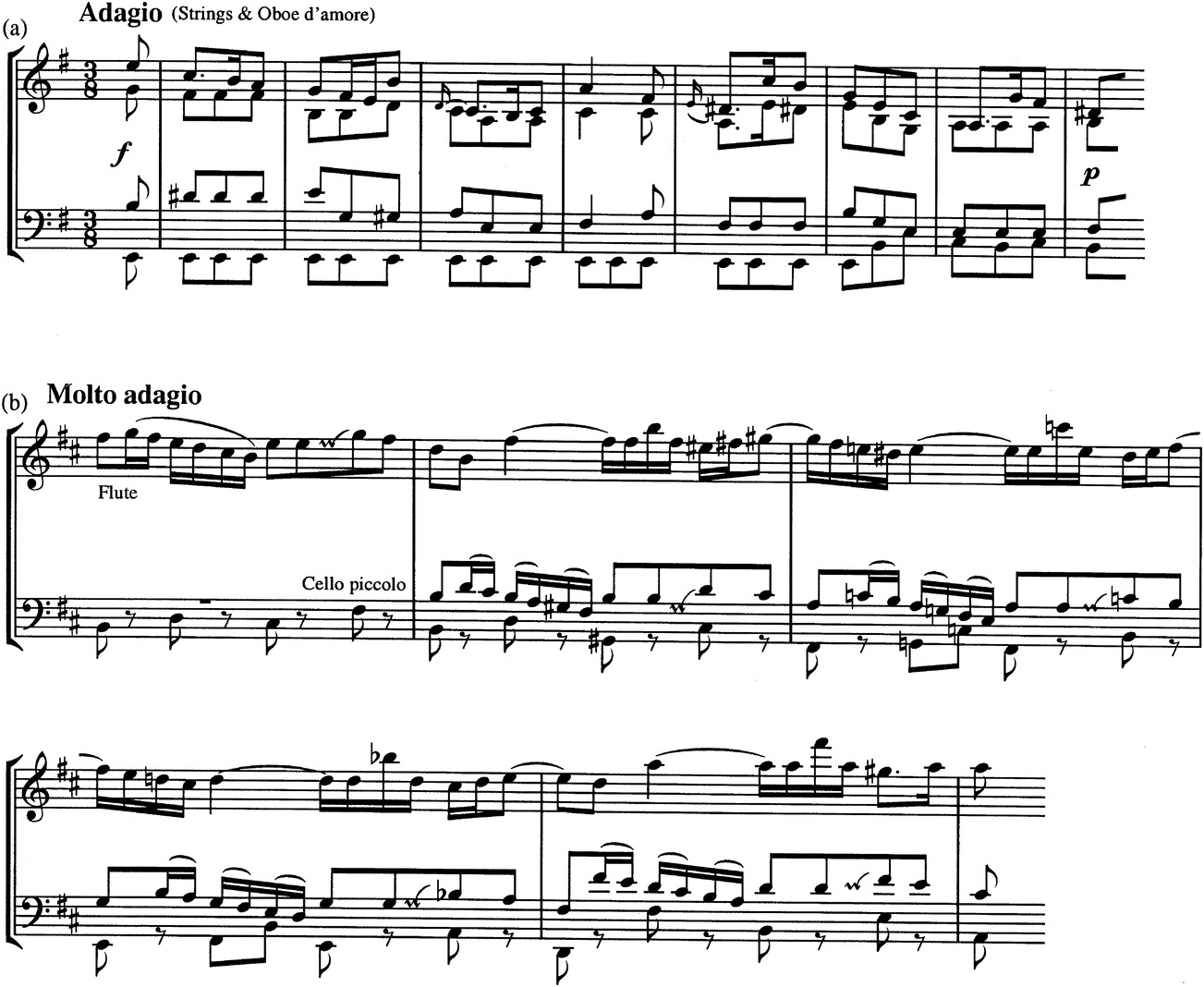

In the chapel cantatas, and perhaps on other occasions, the six male singers and a handful of string- and wind-players made it possible to create various ensemble combinations, especially when other soloists joined them. This was an enthralling opportunity for a young musician and composer of cantatas. Familiar with the old tradition for mixed consorts, Bach was gradually able to create newer works in a variety of instrumental combinations, fresh springs from which the mighty stream of ‘Brandenburg Concertos’ was to issue later. Particularly after his promotion in 1714, a big ensemble of strings, wind and brass could rejoice in a Sonata for an Easter Day in Cantata No. 31 or introduce the cantata for Christmas Day in No. 63; other ensembles include a five-part ‘French’ string band for an Advent Ouverture in Cantata No. 61, an expressive string and woodwind Sinfonia for a post-Christmas cantata in Cantata No. 152 and a delicate violin solo in the Sonata for the Annunciation in Cantata No. 182. The four solo violas in Cantata No. 18 have an essentially old-fashioned sound and texture, but the work also includes an example of the new recitativo secco (qv), and does so with little sign that Bach was experimenting with something novel to him, except perhaps in the shortness of the phrases. Example 5 already includes both a characteristic change of pace and, because of this, draws attention to important words (‘falls’, ‘fructify’, ‘Word’).

Example 5 Cantata No. 18.ii: ‘Just as the rain and snow fall from heaven, and do not persist but fructify the earth, making it fertile and increasing so that it gives seeds to sow and bread to eat, so should the Word …’

Telemann’s setting of this same cantata text by Erdmann Neumeister is typically bland in its harmony and gesture, emphasizing what a colourful drama Bach brought to the music for the Weimar liturgy. This becomes clearer when on later occasions in Leipzig, Bach writes a cantata as if imitating the simpler harmony and phraseology of the ever-popular Telemann, for example Cantata No. 47 (1726). There is in the Weimar cantatas a lightness of touch in melody and timbre that remained distinct from the later works for Leipzig, and of course from the work of contemporary composers. At the same time, writing recitative with continuo in a cantata was itself a way of reconciling ‘church sounds’ with ‘chamber sounds’, as it had also been for a generation or so of German composers. It is well to remember too that one cannot be sure that such colourful cantatas were performed only in chapel or only as part of its services. Never anywhere else?

Although the intimate understanding of French manière evident in the opening ouverture et fugue of the Advent Cantata No. 61 (1714) may appear to have little to do with Parisian organ music, the way it paraphrases the Gregorian chorale-melody is as French as it is German. De Grigny too, in his book copied by Bach, had paraphrased the original hymn melodies in this way in his settings, though doing so with a degree of arbitrariness in his harmonies (why this, why that, what is the key?) unknown to the orderly Bach. There are other touches of French style in Cantata No. 61, adopted almost certainly as a means of matching the theatrical aura of the text it uses, i.e. one of Pastor Neumeister’s, associated also with Telemann’s ‘French annual cantata-cycle’ of 1714/15. Thus might a cantata – here from 1714, but also others before and after – gather together all and any kinds of musical idiom, not only for the Greater Glory but for that mixing of styles to which the composer was not alone in being attracted throughout his life. Doubtless deliberately, the first movement of a later Advent cantata, No. 62 (1724) paraphrases the same hymn-tune but now in the very different style, not a French ouverture but an Italian ritornello concerto.

Whatever their musical styles, the works being produced in Weimar are responding in a lively fashion to the newer poetry as celebrated in Erdmann Neumeister’s libretti, of which there were hundreds, and gathered as yearly cycles from 1704 onwards. Neumeister’s original title of 1700, Geistliche Cantaten statt einer Kirchen-Music (‘spiritual cantatas in the place of a church anthem’), uses the word cantata in order to allude directly to fashionable Italian chamber cantatas and their sequence of arias (new poetry) and recitatives (new or old prose), now in ‘spiritual’ form. Alien to the Italian conception of cantatas, however, were the additional movements, the instrumental overture, the big choral movement and the final chorale. So of course were any chorale-melodies introduced at any point within a cantata. Such cantata-texts, often published and treated as self-contained poetry, could be realized as recitatives, arias and choruses (these with biblical sentences), and an appropriate chorale could round it off even if the poet’s text did not call for one.

In general, the new texts would naturally encourage a ‘theatrical’ style of music at a certain moment in services, introducing conspicuously new sounds and words, and it is not surprising that court chapels such as Meiningen and Weissenfels soon made use of such texts. At Weissenfels, the composer J. P. Krieger may have set Neumeister’s volume complete. But already in 1709–10 such works were being criticized as theatralische Music by none other than the Leipzig cantor Kuhnau (DDT 58–9, p. xlii). Deliberately or not, Kuhnau was recognizing the difference between court chapels and parish churches: as Bach was to find, a parish church was sensitive to theatrical music. Pastor Neumeister supplied ready examples of these so-called madrigalian texts for the composer of any court or, eventually, of any parish church, and the idea was given impetus by what was acceptable in royal cosmopolitan Dresden. Texts from 1710 onwards that mixed biblical words and chorales with the new poetry were especially acceptable. At Weimar in 1709, a member of the court clergy published a Passion text based on St Matthew, ‘with intermixed devotional chorales and arias’, and it is possible that at least in the town church some such work was performed over the following years (BJ 2006, pp. 45f.).

From now on Bach seems often to have chosen Neumeister texts and, since he set far fewer of them than did Telemann or Fasch, those from other poets such as the court secretary, Salomon Franck, who had a similar way of incorporating biblical words in his poetry. Franck’s Cantata No. 172 for Whit Sunday 1714 draws from Bach an alert series of musical affects: first a rejoicing (big orchestra, catchy rhythms) then a quieter recitative, a tenor aria in the minor interspersed with a forthright affirmation of the Trinity (this with trumpets and bass voice), an exhortatory aria (soothing soprano) and finally a fully orchestrated verse from an Annunciation chorale. While such music lends itself to a sermon-like interpretation encouraged, so one might guess, by the composer himself, the sheer charm of so many melodies in Weimar cantatas should not be missed, as in Nos. 132.i and 63.v. Nor should the inventive timbres colouring the effortless counterpoint, as in the viola d’amore in No. 152.i and two solo cellos in No. 163.iii. These cantatas are not from the earlier Weimar years but follow on the composer’s promotion (pp. 155f.). However, that this was less of a watershed moment, a turning point in his maturity, than it has sometimes been taken to be, seems clear from the sheer scope of the fifteen movements of the ‘Hunting Cantata’, No. 208, from a year or more earlier.

Musical development: counterpoint, variations, concertos

Bach’s musical experiences in Weimar were much wider than is implied either by the Obituary’s emphasis on him as a virtuoso organist or by any other extant documentation. A still-open question is what music visiting artists and companies brought to Weimar, including excerpts from French or Italian operas. There were also his other contacts with neighbouring courts, such as at Gotha in 1711 when he was a ‘guest player’ (Dok. V, p. 273) and then, on returning to Weimar, a successful applicant already for a salary increase – not a coincidence, probably.

It was no doubt from private study rather than court-visiting that a fundamental technique in Bach’s maturing compositions for instruments or voices emerged and bore fruit: his mastery of invertible counterpoint, well beyond the examples offered by any theory-book. For him, this generated virtually any kind of music, from the earliest organ-chorales to the later Inventions (qv), from a Mühlhausen cantata to the ‘B minor Mass’. With this mastery, different themes or melodic lines are combined or exchanged with a bass-line (which is melodious in its own way) to produce music for virtually any wished-for Affekt, including the lightest and brightest. See Example 6(a), recomposed as Example 6(b). Even a canon can be made to work if other such lines are added so as to convince the ear that all is well, as in Example 6(c). Examples 6(a) and 6(c) belong to much the same period (1712–13) and are quite typical. An advantage of invertible counterpoint is that at a stroke the lines become available for re-using in different combinations, and the different keys have their own character. In such ways any initial effort that is required to create the invertibility turns out to be an economical way of generating movements and one that is practically infinite.

Example 6 (a) Cantata No. 208 (1713?).xiii, b. 5; (b) Cantata No. 68 (1725).ii, b. 5; (c) Organ-chorale, BWV 600, b. 9

Typical of the music for choirs had been a counterpoint based on the permutation principle. Bach’s look very like the best achievements of previous composers and give the impression of being ‘systematic’ or ‘calculated’ (see Example 7). This is an old way of creating vocal counterpoint, and while in this instance the lines are still melodious despite the ingenuity, there can appear many short phrases and a certain repetitiousness that arises in the service of the text. In the organ Passacaglia’s fugue, however, the short phrases such as those found in Cantata No. 196 (Example 7) have disappeared, despite this being a permutation fugue. Here, new counterpoint emerges each time and is unpredictable.

Example 7 Cantata No. 196.i, b. 18. Text: ‘He blesses the House of Israel, the House of Aaron’

A less pervasive technique than invertible counterpoint or fugue but still important was canon. The German organist’s custom of making canons at the octave (qv) from the melodies of Advent or Christmas hymns will clearly be challenged more severely by some melodies than others. Example 6(c), ‘Gottes Sohn ist kommen’, required ingenuity if the canon was to work, i.e. to make us think that the lines occurred naturally. Walther’s setting of this melody eases the problem by leaving it longer before the canonic answer, resulting in a movement nearly twice as long as Bach’s but therefore ‘less canonic’. The canon in another Weimar organ-chorale, ‘Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge’, BWV 624, needs to have its answers at varying intervals if it is to work, whereas in the Ten Commandments setting (BWV 635) there are several ‘simultaneous’ canons as the melody accompanies itself. The painstaking thought (and imagination) required for such music is obvious.

Certain practices and techniques, such as creating a set of variations on a hymn-tune by exploring a different motif in each variation, barely survived into the Weimar period, and one can understand why. Such sets, generally called ‘Chorale Partitas’ today (though not with any certainty by Bach himself), seem to have been a speciality of Thuringian organists for a few decades around 1700, if only seldom beyond the second decade. In 1802, Forkel’s claim that Bach found writing sets of variations a ‘thankless task’ (1802, p. 52) arose because he (Forkel) knew that in most cases they merely reiterated the harmony by superficially decorating it. One sees this clearly in the ‘Chorale Partitas’, BWV 766–8 and 770, and perhaps Emanuel or Friedemann had heard the composer speak of the ‘thankless task’. But Forkel could have concluded this because there are so few examples of ordinary variations in Bach’s worklist compared to Handel’s or indeed Mozart’s, with which by then Forkel was also familiar. The remark does not quite do justice, however, to the way a chorale might be varied, reharmonized several times in a cantata or a Passion (as was the case): harmony can be imaginatively explored under a melody as much as the melody can be decorated. More to the point, perhaps, is that any such ‘partitas’ reliably attributed to Bach confirm that his early activity as a composer was typical of a Thuringian organist of the time.

All the same, Bach can be imagined to have reacted against the simplistic variations he came across in his youth, works that continued to influence Handel in his variations. One notes that the four big, outstanding and indeed unique variation-works that Bach did compose in the course of over thirty years – Cantata No. 4 for voices, the Passacaille for organ, the Ciaccona for violin, the Aria mit Veränderungen (‘Goldberg Variations’) for harpsichord – do everything but reiterate the harmony in some simplistic way. A similar point could be made about those Leipzig cantatas that are based, in rather different ways, on seven-verse chorales (see p. 283). Three late works, Musical Offering, Art of Fugue and ‘Vom Himmel hoch’, take the variation principle a step further by using the stated theme not for reiterating or varying the harmony but as a point of reference, one way or another, for an array of complex canons.

For the picture he is drawing of a serious composer, Emanuel described the Weimar job in terms of organ music and, after the promotion in 1714, of ‘mainly church pieces’, as he called them. And yet of huge importance to Bach, something even changing the direction much of his music was to take, was something Emanuel never mentions: sudden acquaintance in 1713 with a group of new string concertos from Venice. Whether or not this was as simple as evidence now suggests, the vivid and seductive effect of these spectacular pieces, perhaps glimpsed already in isolated examples previously making their way north, can be imagined: a voracious, energetic composer in his late twenties suddenly gets to know Vivaldi’s Op. 3, L’Estro armonico, and Op. 4, La Stravaganza. A revelation! Did Emanuel not appreciate this or did it detract too much from his picture of the self-made German master?

The closer Bach had continued to keep to tradition in his organ and harpsichord music, the more startling must have been the ‘Vivaldian effect’ in other kinds of music. When, probably in July 1713, the young Prince Johann Ernst returned to Weimar from a stay in Holland with copies of music by Vivaldi and other Italians (Corelli? Frescobaldi?), the prints of string concertos he brought took the form of part-books: not scores but sets of playing parts. So one is left to imagine the effect on players picking up these parts and trying them out; or on the transcriber as the concertos emerged in score and revealed their effects. Soon after the prince’s return, one imagines those musicians concerned (the prince, his half-brother, Walther, Bach, some string-players) gathering to play the concertos in the junior duke’s residence, the Red Palace or Rotes Schloß with or without the senior duke’s approval.

There could be various reasons why one Weimar organist, Walther, seems to have worked more with the older generation of Italian composers such as Torelli, while another, Bach, worked increasingly with the younger such as Vivaldi: personal preference, accident of sources, availability, even reciprocal agreement between the two organists. In any case, the sheer quality of Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico concertos is surely the reason for Bach’s transcribing at least half of them, either at that time or later: three for harpsichord alone, two for organ alone, and the unique one later for four harpsichords and strings. Two more each from Op. 4 and Op. 7 (1716, one for organ) must be a sign of someone’s continuing enthusiasm for such transcriptions, Bach’s or perhaps a student’s. Transcribing part by part was laborious, and it must have been difficult to resist modifying in some way what was being transcribed.

Whether Bach learnt from Prince Johann Ernst that at this period in the Protestant Netherlands people could hear such Italian concertos being played in certain public organ recitals is not known, nor therefore whether he or anyone else had the idea of producing concerts of this kind in Weimar. There is no evidence either way, unless one takes the duke’s support for Bach as a hint that he did play such (private?) recitals – which is possible. Transcriptions were not the only way to assimilate Italian styles, as one sees later in the same year, 1713, when Bach’s aria BWV 1127 (apparently for the senior duke’s birthday) combined old and new: the German organist’s traditional bicinium bass has become a continuo part of a kind familiar to Italian cellists, and the old German strophic form (different verses to the same melody) is supplied with new Italian string interludes. The combination made a suitable offering to the duke, one of many offerings at a typical ducal court, no doubt – but why Bach and not the capellmeister? Was it a gratuitous, even presumptuous, act of homage?

If anything of Vivaldi’s music such as the trio sonatas Opp. 1 and 2 (1705, 1709) had previously penetrated to Weimar, the young prince would have been alerted before his trip to Holland to search for more of their kind among the Dutch publishers and booksellers. Albinoni’s three-movement concertos were being published from 1700 onwards, and signs of Vivaldi’s influence are also there in movements of Handel’s Concerto in B flat, HWV 312, now dated c. 1710 in Hanover. In Bach’s case, it is hard to imagine how at least some of the ‘Brandenburgs’ and the solo violin or harpsichord concertos would have come about without the revelations offered by Vivaldi’s Opp. 3, 4 or 7. All these have a dashing quality beyond even Corelli’s concertos, with singable melodies and clear solo sections, plus certain stylistic earmarks such as beginning in bare octaves. Any composer would be excited by Vivaldi’s way of organizing instrumental pieces by the means of repetition, note-spinning, sequences and simple harmony, all handled inventively with great rhythmic vitality.

It was probably at a period when the young prince was composing his own works in this style that Walther also arranged many Venetian concertos. Telemann got to hear of the prince’s efforts and published some of his works. Sources also attribute to Bach two transcriptions of the prince’s Concerto in C major, one for organ (BWV 595) and another, different in detail and substance, for harpsichord (BWV 984). There is a commonsense logic to the concerto shape of three movements, fast–slow–fast (or lively–slower–quicker), and it occurs as if quite naturally in very different genres. Two examples of the shape are the earlier Toccata in C major for organ, BWV 564, and the much later double-choir motet ‘Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied’, BWV 225.

Musical development: strategy, tactics

How to shape a piece of music, to sustain length and allow a movement to develop and come to a well-paced conclusion without repeating inappropriately or continuing boringly, was clearly a question of importance to any composer. So was another: how to create the faultless miniature.

In both the small and larger-scale works of the Weimar period, melodic flair merges with a harmonic logic in which a simple common chord can sound as striking as a complex discord. Seldom if ever does harmonic control fail Bach, though he comes close to it at one moment in the long Fugue in F major, BWV 540, in a precipitous modulation from C minor to D minor (an unreliable source or a textual crux?). When a movement of carefully organized length strikes one as not very inspired, as some movements in Cantata Nos. 12 or 31 do, it could be that too much attention has been paid to conveying a text. In the case of No. 31, for example, the idea of ‘Heaven laughing’ leads to something ordinary in the melody, harmony and rhythm, while the idea of the ‘Prince of Life’ leads to a merely formulaic rhythm. Conventions can be too automatically applied, as when without any further ado chromatic intervals convey something anxious, sad, regretful or in some other way negative. As in other works of the period, Cantata No. 12 can leave an impression of ‘going through the motions’, as too does many a later cantata aria.

Cantata No. 12 also has a slow, opening melody for oboe that is more touching than anything one is likely to find elsewhere except for certain moments in Handel’s Italian cantatas. Even using standard effects like the Neapolitan sixths (qv) in an aria of the same cantata – picking ingredients off the shelf, so to speak – can also have a touching quality. It is a formula of the kind that went through changes later and gradually became rare in Bach, but the conventional appearances of it were a first, necessary step. The sheer number of Neapolitan sixths in compositions from the Weimar years and earlier (especially in certain toccatas) is presumably a sign that he liked them and found them ‘expressive’, doing so right up to the ‘B minor Mass’, both in a new movement (Kyrie) and an earlier one now transformed (Agnus dei).

Chromatics were another time-honoured formula that could automatically embellish harmonies, and one much practised by Walther and Bach. When Bach writes longer or shorter phrases that include all twelve semitones, as in a recitative of Cantata No. 167 (1724) or passages in the later A minor Prelude WTC2, one can assume it was intended, a stretching of the older chromatic motif in order either to be more expressive or to do something new. The chromatic phrase was one of a whole catalogue of the motifs or patterns of notes (figurae) taught and used by many German composers, learning from precedent rather than books. But in Weimar the year of Bach’s arrival, Walther listed and briefly described many of them in an unpublished treatise written for the same Prince Johann Ernst, the Praecepta of 1708, in which he gave them Italian names and in this way marked their origin. (Another somewhat similar treatise probably of some influence on German teachers was Mauritius Vogt’s Conclave thesauri, Prague, 1719). Bach’s ‘Chorale Partitas’ play with Walther’s motifs and explore his own versions of them, and they lead gradually, by steps not now traceable, to a unique collection of short organ-chorales in which the patterns are applied with unheard-of sophistication.

These are the chorales for the church year, in an album or collection later called the Orgelbüchlein (‘Little Organ Book’), which it is possible to view as the peak of the tradition for creating music by subtly embellishing hymn-tunes and their harmony. The melodies are harmonized in such a way as to establish a unique mood for each of the texts, ‘depicting’ the words of the hymns with old and newer motifs. Yet the Orgelbüchlein’s settings are rarely single-minded in this endeavour, especially when compared with chorale-based compositions by earlier organists such as Scheidt or Steigleder, or later by Walther and Vetter (see Example 10 on p. 160). One has the impression that in this album Bach is deliberately using the very motifs outlined by Walther in his book and adding quite a few of his own. Did the two organists discuss such techniques, vie with each other, compete in composing certain types of music?

The two men were surely aware of each other’s activities, and Walther’s music often uses straightforwardly the very patterns handled more inventively by Bach. Bach’s earliest surviving puzzle canon, BWV 1073, is dedicated to Walther, 1713, and it is not unlikely that he knew Walther’s copy of Johann Theile’s book Kunstbuch, Naumburg 1691, a treatise on ‘special music and secrets deriving from double counterpoint’. Both of them also made use of the works of G. M. Bononcini, Walther his treatise Musico prattico, and Bach his Sonata Op. 6, No. 10 (Venice, 1672) – or so it seems, for a theme from the latter appears in the so-called ‘Legrenzi Fugue’ in C minor, BWV 574. Assuming this print was his source for his treatment, Bach condenses the original movement and omits its echo-passages, a credible sign of his technique for reworking his models.

Note-patterns are like tactics in need of a strategy. In a cantata movement or prelude based on a chorale, shape is no special problem, since the chorale-melody provides it. But what of substantial pieces of music without such props? It is not obvious how far Vivaldi’s concertos helped Bach shape movements of his own, which, in the big organ preludes and fugues, are lone works anticipated by no predecessor and matched by no successor. This is uncertain despite assumptions made by Forkel in 1802, and copied ever since, that Vivaldi’s ritornello movements were models for Bach. Forkel seems not to have known of Torelli and the possibility that his concertos had also been models. But he did know that Emanuel’s colleague Quantz had previously acknowledged the impression Vivaldi and his ‘beautiful ritornelle’ had made on him, and how he had for a time taken them as a ‘good model’ in his own music (Quantz Reference Quantz and Marpurg1755, p. 205). For Forkel, if Quantz was bowled over by Vivaldi, so must his hero Bach have been.

But Bach had already written keyboard fugues which tend by nature towards a kind of ritornello form, with a theme returning periodically, after episodes and with a final statement or coda. Returns or ‘local repetition’ are not only so natural, even necessary, to the transient thing that is music, but the principle of ‘returning themes’ is open to a huge variety of treatment. For nearly fifty years Bach shaped fugues, concertos, arias, sonatas, chorale-preludes and choruses around this principle, whatever other habits formed around each genre. The principle of such a shape, especially where the opening and returning section is short or very short, had been familiar with Kuhnau and Buxtehude before 1700, and Bach’s Cantata No. 131 (1707?) includes something of this kind. But the organ Fugue in G minor, BWV 535a, is cast as a clearly formed ritornello and, if its dating is correct, c. 1705–7, is already producing a shape rare for organ fugues on this scale. Whether one calls this work ‘a fugue in ritornello form’ or ‘ritornello form as a fugue’ is moot: the tight fugues of previous periods are now giving way to longer-paced movements that return as naturally to the theme after a special episode as any concerto movement does.

It is likely, though not documented, that in his early days in Weimar Bach had come across works of Torelli, and therefore seen further examples of movements planned and constructed so that a distinctive theme returned after distinctive episodes. In Albinoni’s Sinfonie (1700) he could already have seen examples of fugues in a clear ritornello form somewhat comparable to the Fugue, BWV 535a. And from elsewhere in Albinoni he could have learnt the effect of bringing back at some point in a movement the whole of the opening statement, as well as marking the sections with strong cadences. In this way he would find how to design a substantial movement without deliberately imitating Vivaldi’s breathless continuity. Nevertheless, although Bach’s watchful ways of proceeding could well have gradually produced the great structures without his knowing any Italian concerto, the vividness of Vivaldi surely left a permanent mark. It can be heard in such later concertos as the A minor for Violin and the ‘Brandenburg Concerto’ No. 4.

The free way in which Italian composers would treat the returns of a theme (now longer now shorter, now this segment now that) also left its mark. Not only do Bach’s ritornello movements have various ways of re-presenting the returning theme but there are moments in his concertos, cantatas and even organ-chorales in which one particular segment of a theme returns when it could easily have been another. Extant sketches for the mature cantatas show the composer similarly considering and reconsidering such details with great care (Marshall Reference Marshall1972). Any apparent ‘arbitrariness’ in this process has the effect and the purpose of avoiding the too-obvious and of surprising the listener: the principle of return is not denied but is constantly rethought. A rather theoretical approach to Bach’s invention in recent years has emphasized those ways in which he creates a structure by bringing back themes or snatches of melody already heard; but more fundamental still, and far less of an Italian characteristic, is the control of harmonic processes, taking listeners in whatever direction his sense of logic moves. Cantata No. 199 (1714) already displays ritornello shapes one is unlikely to find in contemporary cantatas by a Graupner or Telemann, and looks like a conscious swerving away from their simpler conceptions.

A firm harmonic control can be heard in compositions written during Bach’s thirties, such as the Cello Suites, well before the biggest mature organ preludes in ritornello form. In addition, the kinds of theme, rhythm and even the reiterated chords heard in cantata or concerto movements can often be recognized as Italian in inspiration, though sustained for longer than they might be in Vivaldi’s Opp. 3 and 7 or any other concerto transcribed in Weimar. The impression Italian ritornello forms made on Bach is hinted at in such a work as Cantata No. 31 (Easter Sunday, 1715), where the opening instrumental Sonata uses a full orchestra to imitate a Vivaldian opening theme in octaves. A powerful stirring of the spirit on the day of Resurrection, though harmonically not adventurous! What follows, however – arias with recycled episodes, a fund of distinctive melody, moments of canonic imitation – would not be mistaken for Vivaldi or Albinoni or any contemporary German composer.

The year 1715 was also the year in which Albinoni’s Op. 7 Concertos were published in Amsterdam, giving yet other examples for structuring instrumental pieces. Even if none of them had circulated earlier in manuscript, in print they could have easily sped on their way to Weimar or Berlin or Dresden. By then too Bach had also developed ritornello shapes in organ-chorales, with or without having regard to Vivaldi’s concertos.

Some Weimar music: more on Italian and French tastes

Although patchy, existing evidence supports what one would expect: that the years Bach spent at Weimar in his twenties and early thirties saw developments in his chamber music, especially no doubt during his later years there. Although the sources do not confirm it, some instrumental movements known as adaptations or arrangements for church cantatas at Leipzig (Nos. 146, 156, 188, 35) or in harpsichord concertos (D minor for solo harpsichord, C major for three harpsichords) might have originated in other guises and for other forces in concerts during the later Weimar years.

Doubts sometimes expressed about the authenticity and especially the date of strikingly original works such as the ‘C major Triple Concerto’ may arise only because no one knows what the original form was, or even whether it had more than the one original form often supposed for it, e.g. as a concerto for three violins in D major. No other composer of either c. 1715 (violin version?) or c. 1735 (harpsichord version?) springs to mind as likely to have been capable of its original and characteristic amalgam of subtle counterpoint, extrovert rhythms, purposeful harmony and pleasing melody. That goes also for both of the triple concertos now known, the C major and D minor. Sources do not exist to clarify the history of such works, which is most unfortunate since only with them could one trace the composer’s maturing style, how quickly indeed it had matured since the arrival of Vivaldi’s concertos.

Slow movements with prominent solo melodies become a hallmark. Instrumental movements prefacing the Weimar Cantatas Nos. 12, 21 and 182 do not seem to me to owe very much to Italian concertos but rather result from an imaginative composer’s way of building on earlier German consort music that had still been the model for the Sonatina prefacing Cantata No. 106. Nor, yet more importantly, can one be certain what the expressive or emotional impact of such slow movements was expected to be and how much this changed over the period. The likelier that the well-known and bewitching Largo of the F minor Harpsichord Concerto, BWV 1056, imitates a Telemannesque woodwind concerto of c. 1715, the likelier that in its Leipzig version (late 1730s) it had matured to become even more expressive: now with pizzicato strings and a cantabile harpsichord melody in A flat major. What was charming, light and fresh originally and again when re-used in Cantata 156 (in F major, c. 1729), becomes more seriously beautiful, more affektvoll, probably slower, exquisite, inspiring reflection through the concerto’s key and instrumental colour.

By no means of minor interest, though utterly different, are the transcriptions for harpsichord alone of Italian and other string concertos BWV 972–87, probably made in the later Weimar years and appealing to the taste not only for imported string music but for a new world of keyboard music, one far from German traditions. Whatever music had penetrated to Thuringia beforehand, now, at a stroke, there appeared groups of imported works revealing how to shape sustained movements when there were no words to help provide shape or organization. Some composers were also surely desiring to move on from the traditional genres, such as suites, variations, fantasias, fugues, concerti grossi (qv), and would have found Italian solo string concertos to be another world. Bach’s keyboard transcriptions made at Weimar create a strikingly different repertory and present yet another peak of achievement in one very particular genre: indeed, a conspicuous group of works. They offered the Thuringian organist new melodies, new movement-shapes, new effects and textures, giving the player, then and now, a welcome breath of fresh air after the older German idioms: Vivaldi after Buxtehude.

In many little details these transcriptions of Bach anticipate details in his own later works. They include the broken chords colouring episodes (‘Fifth Brandenburg’), the emphatic chords in 2/4 time (Italian Concerto), the slow-movement cantilena (the three string concertos) and even simple contrary-motion scales (‘Goldberg Variations’): all these appear in the concerto transcriptions. In the work of other composers such as Christoph Graupner and Handel signs of Vivaldian influence can certainly be heard, but Bach’s transcriptions stand as a distinct repertory. One can still find them more effective as music for public performance than most suites and most fugues, for unlike them, their origins lay precisely in this: music for public performance. Nevertheless, how far Bach understood the natural verve and rhetoric of Venetian string concertos is an open question. Perhaps he wished to temper it with ‘German seriousness’, for it is otherwise difficult to understand why he sometimes filled in Vivaldi’s rests with bits of busy counterpoint.