By the end of the Hellenistic period, pursuit of the good life had established itself as the main purpose of philosophy. Academic skeptics argued that each dogmatic school’s thought hangs off its view of the human final end and then proceeded to attack all possible systems.1 Stoics positioned ethics as the crowning gem of their curriculum. Epicureans went so far as to judge theories in physics by whether one could attain tranquility by accepting them. Augustine and Boethius are squarely rooted in this Hellenistic outlook, which makes living well the linchpin of all philosophical undertaking. Just as important was the idea that the best life for a human (Greek: eudaimonia; Latin: beata vita) is a matter of realizing our distinctively human nature. Within the domain of ethics, ideas about living well are ideas about human excellence or virtue (Gr.: arete; Lat.: virtus). These, in turn, are grounded in ideas of human nature within the domains of physics and psychology. While the various Hellenistic schools argued about the details, for the most part they all took this general framework for granted. When Augustine and Boethius depart from this Hellenistic rootstock, it is by grafting on Christian and Platonist ideas, which are sometimes hard to distinguish from each other. The result is a hybrid of sorts, a living system which is what the West later came to accept as Platonism. At the heart of this system is the notion that human beings are metaphysical straddlers: we have one foot in eternity and another in time. When it comes to the good life, the task is to live the best life for us, given the kind of thing we are. In practical terms, this calls us to reorient our lives around eternal norms, even amid the transient concerns of everyday life. The present chapter aims to orient readers to the early medieval project of using Hellenistic and Platonist frameworks to work out how Christians ought to live their lives as the created image of an eternal God. This interplay of time and eternity provides a thread through a maze of philosophical puzzles distinctive of this period: the problem of evil, fate vs. free will, temporal vs. eternal law, grades of virtue, theories of mind, and strategies for reading Scripture.

We will begin with Augustine of Hippo, who sets out this project, and Boethius, who refines it. We will then skip ahead to the Carolingian renaissance with Alcuin of York, who helped restart liberal learning, and Eriugena, whose encounter with the negative theology of Pseudo-Dionysius led him to reframe the Augustinian project, creating a bold new breed of Christian Platonism. Our period sits in the era between apologists fighting for Christianity’s survival and scholastics seeking to refine and systematize centuries of classical, Arabic, and Christian thought. Ethical inquiry, particularly in these earlier centuries, is more concerned with self-reflection and spiritual exercise than demonstrative argument. It is more first-person than third-person (see Matthews Reference Matthews1992). What’s more, frameworks and hierarchies that later medieval thinkers take for granted are still being put together. I take this to be a strength: insofar as these earlier thinkers are operating closer to the ground, it is easier to connect their work to issues today.2

1.1 Augustine

Augustine was born in the relative obscurity of provincial North Africa. Like Cicero before him, his skill for rhetoric carried him quickly to the center of political power, at that point the imperial court at Milan. Situated between Constantine’s conversion and Justinian’s theocracy, Augustine’s Rome was still only partly Christianized. While Augustine looked to Ambrose as a role model for an educated Christian, it was Ambrose’s rival in the Altar of Victory affair, Symmachus, who secured Augustine his position in Milan. At this point, the question was not whether Christianity was here to stay, but what form it would take. Augustine’s philosophical career was dominated by working out a synthesis of Christian faith and classical philosophy.

The first challenge in discussing Augustine’s ethical thought is to determine what we should consider his “ethical works.” As with the American Pragmatists, Augustine criticized pursuing knowledge for knowledge’s sake (Conf. 10.35.54–57). Even his most tortured metaphysical speculations and antiquarian exegetical pursuits tie back, however indirectly, to improving how we live. So in one sense, we could look to any of Augustine’s works for his ethical thought. Given that the corpus is huge – dialogues, letters, sermons, scriptural commentaries, autobiography, polemics – I will narrow my focus to those works that readers of the present volume are likely to be most interested in. Yet this raises a second challenge: if we use current assumptions about what counts as “ethical thought” to guide our selection, we risk giving a skewed version of earlier figures’ work. Modern ethics tends to focus on the rightness or wrongness of particular actions; ancient and medieval ethics tend to focus on the goodness or badness of lives. This difference, however, can be put to good use, as it allows us to augment current debates by setting them within more holistic discussions from the past. I will thus focus on aspects of early medieval thought that differ most from our own. This raises the third challenge: differences often sit not at the level of individual claims or arguments but in the overarching projects of whole works. We must set individual passages within their larger contexts, engaging in something closer to formal, literary analysis than might be usual for some philosophers. Put another way, to see what is characteristic of Augustine, we must ask not merely what he thinks but what he is doing with those thoughts.3

1.1.1 De libero arbitrio

The deep structure of De lib. arbit. is built around the idea that not all goods are of equal value. (See Harrison Reference Harrison2006 for a close reading of De lib. arbit.) Augustine helps clarify the relative worth of things by grouping them into three classes. Eternal goods such as God, wisdom, and mathematical truth are the most valuable things there are. Temporal goods such as wealth, physical resources, and bodily health are at the bottom of the value scale. Human beings, as metaphysical straddlers, come in the middle. He articulates this scheme in De lib. arbit. 2 by reflecting on human acts of judgment (2.3.7–10.29). If I am deciding whether to replace a dented salad bowl, then clearly I am worth more than the salad bowl. Humans judge things; things don’t judge humans. In passing judgment, however, I use eternal standards which are not up to me to decide: in this case, mathematical facts about circles. I cannot change the definition of a circle to accommodate my dented bowl. Eternal truths are thus more valuable than the human beings who use them. This broad structure of the world is mirrored in human nature. I am certain that I exist, that I live, and that I understand (that I exist and live). Yet mere existing, which I have in common with rocks, is not that impressive insofar as living things do it already. In turn, living, which I have in common with animals, is not that impressive insofar as all understanding things do it already (2.3.7). Human cognitive faculties mirror this scheme in a similar way. My most basic way of grasping the world is through my bodily senses. Yet through an “inner sense” I coordinate and judge my five senses, even though I cannot grasp this inner sense through any of my bodily senses. My inner sense is thus worth more than my bodily senses. This much I have in common with other animals. Yet insofar as I can reflect abstractly on such matters, e.g. in working through the present argument, my reason, which takes my bodily and inner senses as its objects but not vice versa, is higher still. This reason is the highest human faculty. Through it, I am connected to eternal goods, just as my bodily senses connect me to temporal goods. In this way, human psychology bridges eternity and time.

If we accept Augustine’s three broad classes of relative value – temporal things, human beings, eternal goods – then we should respect these relative values when making decisions. De lib. arbit. 1 explores what happens when we do not. If I steal my neighbor’s car, then I have inverted the actual worth of things in valuing a temporal good over a human being. On this view, evil action arises from inordinate desire or “lust” (libido), which De lib. arbit. 1 defines as loving something that can be lost against one’s will. To “love” a thing in this context means to thoroughly invest oneself in it, to place it ahead of all else in one’s decisions. In De lib. arbit. 2’s terms, this is to value a temporal good as though it were something more than temporal. This inordinate desire also explains how temporal punishment works (1.2.5–5.12). All a state can do to a criminal is take away temporal goods, whether wealth, freedom of movement, or even embodied life. Yet this taking away will punish, in a strong sense, only those people who love temporal goods inordinately in the first place. While this does not line up individual crimes with individual punishments, it does sort out broad classes of people. Those who keep their desires in line with what things are actually worth may have temporal goods taken away, but, as the Christian martyrs have shown, they will not really suffer as a result. What’s more, individuals are responsible for their own inordinate desires (1.7.16–11.22). Temporal goods or even other people cannot corrupt my desires unless I acquiesce. Eternal goods, meanwhile, will not do so given that they are by definition good. It follows that the human individual, by his own free choice, is responsible “for enslaving himself to lust.” Given that this follows from the normative structure of reality, Augustine concludes that it is a matter of eternal law that evildoers make themselves susceptible to temporal laws’ punishments.

The state of having one’s desires in line with the actual worth of things is what Augustine calls “piety.” While this is not sufficient for attaining happiness, Augustine treats it as a necessary step along the way. At De lib. arbit. 3.2.5, he sets out the “rule of piety” as calling us to (i) think of God in the highest terms possible; (ii) thank God for the goods He’s given us, even if they are not the greatest goods; (iii) acknowledge our sins and look to God for healing. Augustine introduces this by thinking about a puzzle of how it is that we freely sin if God foreknows our actions. The answer – that our actions cause God’s knowledge, not vice versa – is from an ethical perspective not as important as his analysis of how people go wrong in dealing with this puzzle. Some, by concluding that God cannot know our free choices, contradict (i). Others, by concluding that we are not to blame for our sins, contradict (iii). Both groups inquire “impiously.” From this small example, Augustine makes the more general point that the only way to make progress in inquiries such as this is to hold firmly to the rule of piety. On my reading, this discussion of piety provides the linchpin for the whole of De lib. arbit. Looking back, we see that the philosophical inquiry leading up to this point helped instill a pious mindset: book ii’s classifications of goods drive home (i) and (ii), while book i’s discussion of punishment drives home the importance of (iii). Looking ahead, we see the rest of book iii taken up with an exploration of Genesis which is guided by this pious outlook.

The surface structure of De lib. arbit. is built around a discussion between Augustine and his friend Evodius over the problem of evil. Book i opens as Evodius asks whether God is responsible for evil action. The discussion of crime and punishment that ensues brings them to the answer: no, because humans freely choose to give in to inordinate desire. Book ii opens with the question of whether God was wrong to give us free will which makes evil possible. They proceed to spin out hierarchies of goods which drive home the general idea that all goods are good, even if not all are the greatest goods. Augustine positions free will in this scheme by two criteria (2.18.47–20.54). Great goods, such as virtue, can be used only for good. Free will clearly does not fit. Among the class of goods that can be used for good or evil, minor goods are those without which we can live rightly, e.g. feet, while intermediary goods are those without which we cannot live rightly. Augustine places free will in this intermediary class. In fact, it is through this intermediary good that we have access to great goods of virtue freely chosen. Free will is thus a good and God was not wrong to give it to us. If evil exists at all, it does not exist as a thing (after all, God made all things good); rather, evil is merely a perverse movement of the will. Book 3 opens with the question of where this perverse movement comes from. After running a quick piety check, Augustine looks to Scripture for an answer. He responds first (3.5.12–16.46) by invoking a principle of plenitude, i.e. that the world is a perfect good because it contains every possible grade of goodness. This involves multiple comparisons, e.g. a horse that wanders off is better than a stone that stands still. Yet this perfection does not require human beings to sin, merely the existence of human beings who could sin. God is thus not the source of the will’s perverse motion. Augustine then turns to the account of the Fall in Genesis to show where this perverse motion does come from (3.18.51–25.77). While we today are responsible for freely choosing to sin, our wills are impaired by ignorance of the good and trouble at holding to it (3.18.51–23.70). This ignorance and trouble are punishment for the original humans’ transgression. Adam and Eve, by contrast, were created in a middle state, not unlike infants, and could have chosen wisely or foolishly. Unfortunately, they took the latter option at the Devil’s prompting (3.23.66–25.77). What then of Lucifer? As the highest created being, he must have been aware of what a great good he was losing in turning away from God. Augustine suggests that it was the realization of his own exalted status as the pinnacle of creation that led Lucifer to value the penultimate good, himself, over the ultimate good, God. Thus, “pride is the beginning of all sin.”4 In a final twist, it turns out that the process of thinking through the problem of evil instills the virtue, piety, that opposes the vice at the heart of evil, pride. In short, thinking about evil makes us better people.5

De lib. arbit. may open with a merely theoretical question of why God allows evil. Yet the inquiry that ensues seeks nothing short of reorienting our relationship to temporal and eternal goods. This project is best understood, I suggest, against the backdrop of Platonist ideas about the “grades of virtue.”6 The basic idea is that if virtues are human excellences, then there are three different ways in which humans may excel: living an embodied life (civic virtue), purifying themselves of embodied life (kathartic virtue), and living above bodily life (contemplative virtue). References to this scheme are scattered across Augustine’s dialogues.7 The most elaborate comes at the end of De quantitate animae, where Augustine develops Plotinus’s three grades of virtue into a seven-step scheme of the human soul’s activities (33.70–36.81). The first three involve the soul’s (1) living, (2) sensing, and (3) rational activity through the body. In the next two, the soul turns to itself to (4) purify itself of bodily attachments and (5) keep itself pure. In the final two, the soul (6) looks to and (7) finally sees God. The more significant stages here are 4 which De quant. an. identifies as “virtue,” i.e. kathartic virtue, and 7 which it dubs “contemplation.” Stage 3 represents the highest human life short of the inward turn and is characterized by arts from housebuilding to politics to poetry. Yet one may be an excellent poet and a terrible human being. I suggest that Augustine does not allow for independent civic virtue.8 Virtue requires self-knowledge, in particular knowledge that the rational soul is more valuable than anything physical but less valuable than God. As metaphysical straddlers, our best life is to contemplate eternal truths in God. Our second-best life is to strive for such contemplation, while using the same eternal standards in directing our day-to-day affairs. There is no third-best life. Treating the world only on the world’s terms is, for Augustine, not a viable option.

1.1.2 Confessiones

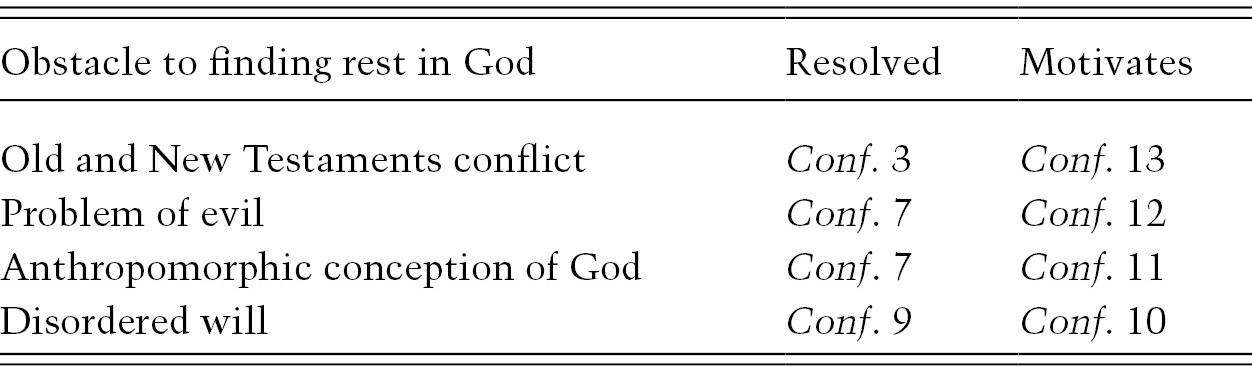

Augustine opens Confessiones announcing, “our heart is restless until it rests in you [God]” (Conf. 1.1.1) and closes it with an allegorical reading of the seventh day of creation, when the human heart will finally rest in the Lord (13.35.50–37.52). If we take this as the work’s main frame, then the intervening action consists in Augustine working through obstacles to finding this rest. He comes close to giving us a table of contents at the start of book 3. At this point, a twenty-something Augustine has, in the course of studying rhetoric, read Cicero’s Hortensius, which set him on the search for God and wisdom. Meanwhile, given his Christian upbringing, he holds the “name of Christ” to be a requirement that is not up for negotiation. The trouble is that he has been confronted with two groups – Catholics and Manichees – who claim the name of Christ and promise a path to wisdom. Augustine reports that three Manichee critiques of Catholicism held him back: conflict between the Old and New Testaments, the problem of evil, and Catholics’ anthropomorphic conception of God (Conf. 3.6.10–7.12). As in De lib. arbit., Conf. treats a rightly ordered will as a necessary step along the way to knowledge of God. We may thus add Augustine’s disordered will to the list as a subsidiary problem. Conf. is structured around these four obstacles to finding rest in God. The narrative books, 1–9, recount Augustine working through them in a sort of coming-of-age story. The answers he arrives at, in turn, motivate the self-reflection of 10 and scriptural exegesis of 11–13, as Augustine finds his new worldview within the account of creation in Genesis.9 (See Table 1.1.)

These critiques and Augustine’s responses to them build upon the ethical thought of Augustine’s dialogues. Let us therefore walk briefly through Conf., tracing how each of these threads plays out and focusing on how the discussion here expands upon what we have already seen.

Manichees were selective in their use of Scripture and criticized the Catholics for accepting contradictory passages, e.g. the differing stances on polygamy found in the Old and New Testaments. Augustine responds by invoking an account of temporal and eternal law (3.7.13–9.17). His strategy is to argue that eternal laws never change, temporal laws may change, and issues like polygamy are matters of temporal law. Scripture may thus without contradiction endorse polygamy in one instance but not another. Augustine draws eternal law from Matthew 22: love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind; love your neighbor as yourself. In this, he finds a scriptural hook for De lib. arbit.’s hierarchies, according to which God is to be valued over all else, and rational human beings over non-rational creation. Much of the drama of Conf. can be traced in terms of how well or poorly Augustine’s will is ordered around these first two laws.10 To these, Augustine adds a corollary: do nothing contrary to nature. God, after all, created nature, so acts contrary to nature offend the love of God. Otherwise, one should follow the rules of one’s state. These may vary from place to place and change over time, but that’s okay. If these temporal laws contradict eternal law, however, eternal law always trumps. In our terms, this is a kind of Christian ethical pluralism, which moderately minded Christians today should find attractive. In holding to love as the core of Christian ethics and letting the details work out as they will, Augustine walks a middle way between a fundamentalist’s rigidity and a freewheeling relativism which will accommodate cultural differences to the point of spinelessness.

According to the Manichees Good and Evil are both material substances, eternal and equal to one another. Our world is a battleground between these two forces, and the point of Manichee religion is to liberate portions of the Good through ascetic discipline. The reason God does not stop evil is that He cannot. According to Conf. 5.5.8, part of Augustine’s initial attraction to Manicheism was that the Catholics did not seem to have any better explanation of evil. All of this, however, is narrated from the perspective of a forty-something Catholic bishop with Platonist sensibilities, who takes himself to have found just such an explanation. Books 3–7 recount the young Augustine’s progress toward this goal. First, he had to realize that passages of Scripture that seem to offend correct reason may be read figuratively. The sermons of Ambrose introduce Augustine to this idea (5.14.24, 6.1.1–5.8), which he makes ample use of in the later books’ reading of Genesis, particularly book 13. This much gets him over Scripture’s crassly anthropomorphic images of God as a man with a body, sitting on a throne, etc. Yet this leaves him still needing to find a conception of God to replace this crassly materialistic one. Augustine gets there in the ascent of Conf. 7.10.16–21.27. While he borrows moving language from the Psalms, the basic shape of this ascent is in keeping with De lib. arbit. 2’s reflections on human acts of judgment. The main insight in the current version is of God as Being, infinite and immutable, the ultimate cause of all finite, mutable beings. The books leading up to this judge the young Augustine’s progress toward this goal.11

While Conf. 7’s insight finally resolves the Manichees’ three critiques of Catholicism, Augustine finds himself still having trouble committing to his new worldview. In the terms of De lib. arbit. 3.18.51–23.70, the insight of Conf. 7 resolved his “ignorance of the good” but left him with “trouble in holding to it.” Conf. 8 addresses this new hurdle, with Augustine’s reflections on how one’s will can be divided against itself (8.5.10–12, 8.20–11.27, 12.29). Into this are woven narratives of conversion experiences through which individuals have overcome such problems: the pagan orator Victorinus (8.1.1–5.10), Anthony of Egypt (8.6.14–15), and ultimately Augustine himself (8.6.13–12.30). The basic point is that merely assenting to a correct view of God is insufficient for resting in God. One must reorient one’s life around this view. For Augustine, this took nothing short of a providential conversion experience. Conf. 9 concludes the work’s narrative portion by presenting the life of Augustine’s mother, Monnica, as an instance of such reorientation (9.8.17–10.25), and a second, more successful ascent as mother and son rise to God together in the final days before Monnica’s death (9.10.23–13.35).

With Conf. 10 Augustine turns from narrative to theoretical reflection on what it means to seek God within (10.1.1–26.37) and then takes stock of his current progress in reorienting his life around the eternal (10.27.38–43.70). Similar to De lib. arbit.’s piety check, Conf. 10 tests how well the preceding philosophical inquiry has prepared Augustine for reading Scripture. The rest of the work looks to Genesis to ground the new worldview Augustine has forged in books 1–9. Conf. 11 uses Genesis 1:1 as a test case for developing a more sophisticated approach to reading Scripture than the Manichees had allowed for in Catholicism. Conf. 12 reads the account of creation in Genesis in a way that supports the metaphysical assumptions undergirding Augustine’s solution to the problem of evil. Conf. 13 returns to book 3’s discussion of temporal and eternal law, as Augustine presents an allegorical reading of the seven days of creation which, like De quant. an.’s seven grades of virtue, provides a unifying framework for God’s actions scattered across history.

In sum, Conf. reiterates and expands upon the theoretical content we find in De lib. arbit. – grades of goods, temporal and eternal law, account of evil. Both treat philosophical inquiry as a kind of reality check, bringing our confused opinions and desires in line with reality. In this, philosophy provides a useful arena for practicing kathartic virtue, which Augustine treats as a prerequisite to reading Scripture in a useful way. While the two works share similar deep structures, they part ways in their more overt framing, as De lib. arbit.’s inquiry into evil is replaced by a first-person coming-of-age story.

1.2 Boethius, Consolatio Philosophiae

Boethius (480–524) was born into wealth and power and adopted by a descendant of the Symmachus who helped Augustine secure a position in Milan. In addition to keeping up family traditions of politicking, Boethius was an ardent student of classical learning. Fluent in Greek literature, language, and philosophy, he set out to preserve this education for the West by providing Latin commentaries and translations of the complete works of Aristotle and then Plato. But his political career got in the way when he was imprisoned and executed by Theoderic, the Ostrogothic emperor of Rome. Following a Platonist curriculum of his day, Boethius had begun with the logical works of Aristotle and was cut short before finishing even these. While his project would presumably have brought him around to ethical questions eventually, his impending death sentence prompted him to get there more quickly.

Consolation of Philosophy represents the West’s last classically trained philosopher mustering a millennium of thought to prove to himself that despite the loss of wealth, power, freedom, family, and even life, happiness is still within his grasp. The work is cast as a dialogue in which Philosophy personified plays doctor to a Boethius gripped by a spiritual sickness (for clarity’s sake, I will refer to the author as “Boethius” and the character as “the Patient”). Its particular genre takes its cue from Menippean Satire, as the text alternates between sections of prose and poetry, heavy with nature-imagery, in a variety of meters. Scholarship on Cons. has been dominated by two debates. First, why does this work of a Christian author contain so little distinctively Christian content? Second, how does the work’s seemingly scattered collection of ideas fit together, if at all? While the first of these may seem more relevant to questions of ethics, in Boethius’s time issues of literary shape have philosophical significance. I suggest that addressing the second will put us in a position to see why the first is mostly a red herring.

Cons. 1 opens as the Patient bewails his ill fortune and concludes as Philosophy takes the Patient’s spiritual temperature through three questions (1.5–7). Problems arise with the last: “Do you, a human, remember what you are?” The Patient gives the common response: a mortal, rational animal. Philosophy’s diagnosis is that he has forgotten himself, and she sets out to remedy this problem. The Patient’s problem is a lack of self-knowledge. Given that he is in fact a rational animal, the most specific problem is that he has forgotten his immortality. Since this is a lot to swallow, Philosophy sets out on a spiritual regimen, starting with lighter treatments and working her way up to harder ones.

Cons. 2 is a delightful read. Philosophy’s first move is to use rhetorical wit to get her Patient to stop whining. She begins by pointing out that it is in the nature of Fortune to change (2.1–2) and argues, following Epicurus, that minimizing one’s desires is a better way to satisfy desires than relying on Fortune (2.3–4). From here, she moves on to Stoic arguments, stripping the apparent value from externals such as wealth (2.5), power (2.6), and reputation (2.7). She ends with a soul-making argument that what is normally called good fortune is in fact bad as it seduces us into valuing such externals, while adverse fortune is actually good as it helps us recognize true goods such as friendship (2.8).

The gloves come off in Cons. 3, as Philosophy constructs an argument to turn her Patient from false happiness to true happiness. To start, she invokes Aristotle’s endoxic method from Nicomachean Ethics 1, taking stock of what kinds of life people consider to be happy, teasing out the good pursued in each kind of life, and pointing out how each falls short. Following Aristotle, Philosophy argues that people who devote their lives to the pursuit of wealth, office, kingdoms, glory, and pleasure are really after self-sufficiency, preeminence, power, acclamation, and delight, respectively. Yet they never attain these ends, since wealth can be lost, kingdoms usurped, etc. Within NE, Aristotle uses his survey of lives to argue that his own account of happiness captures everything worth capturing in other accounts but without their problems (NE 1.8). In Cons., Philosophy uses the same strategy to argue for a Platonist conclusion. Invoking a principle of convertibility, she argues that each of the goods pursued by the five kinds of life canvassed is, in its true form, the same good (Cons. 3.9). That is to say that, in their true forms, self-sufficiency = preeminence = power = acclamation = delight. Real power, for instance, comes from not relying on anyone except oneself, which is what self-sufficiency really is. People go wrong when they seek part of what is really partless, thus closing themselves off from the whole of happiness. At this point, the Patient has been freed from false conceptions of happiness and turned toward a true one. To show that such a singular good exists (3.10), Philosophy invokes the principle that perfection can decay into imperfection but imperfection cannot build to what is perfect. Given that we have ideas of imperfect happiness, there must therefore be a perfect happiness. And since nothing is better than God, this true happiness is God. Human beings who become happy thus become gods, albeit by participation rather than by nature. Philosophy closes (3.11–12) by arguing that all things are good insofar as they live fully into their nature and they do this insofar as they preserve their own unity. Thus, the God/True Happiness we’ve been talking about is Unity. And since we humans find unity through our minds, not our bodies, we should look for happiness within.

It’s one thing to be convinced that true happiness exists, it’s another thing to be truly happy. What would the Patient need to do to attain such happiness? Book 1 identifies the Patient’s problem as forgetting his immortality. Book 3 elaborates that, in seeking happiness in externals, he found misery by breaking into parts what is partless. What he needs is a way to turn inward toward the unity that sits behind and above external multiplicity. This, I suggest, is the purpose of the rest of the work. When Boethius raises the problem of evil in Cons. 4 and of divine foreknowledge in Cons. 5, the point is not that the Patient wants some nagging questions resolved. The point is that the conceptual work involved in resolving these problems will help the Patient turn inward to (re)capture his immortality.

Cons. 4’s discussion of evil is familiar from Augustine, albeit anchored in different schools of thought: Platonic (4.p2.11–16), Aristotelian (4.p2.17–24), and Stoic (4.6–7). Yet the last of these is introduced via a quite un-Stoic distinction between God’s Providence, which takes in the whole at a glance, and Fate, which is the working out of this Providence in time. Philosophy elaborates by analogies of an artist’s plan vs. the execution of that plan; a point vs. a circle; eternity vs. time. While none of these distinctions is really necessary for resolving the problem – the Stoics did fine without invoking eternity – thinking through them is good practice for thinking about the unity that sits behind multiplicity, thus setting the stage for the final book.

Cons. 5 tackles the problem of reconciling human freedom and God’s foreknowledge. The problem is formulated in two ways: one focuses on its being fore- (5.p3.3–6), the other on its being -knowledge (5.p3.19–32). Philosophy’s response incorporates two conceptual enrichments. The first deals with necessity. If we assume that knowledge is of what is necessary (e.g. mathematical truths), then whatever God knows happens by necessity and not free choice. Philosophy responds by arguing that the necessity of knowledge stems not from the object known but from the nature of the knower (5.4–5). To present this point, she leads the Patient through an ascending series of cognitive capacities, reminiscent of De lib. arbit. 2, beginning with conches, whose sense capacities allow them to grasp objects insofar as they cause feelings of pleasure or pain; brute animals, whose imagination allows them to grasp objects as particulars; humans, whose reason allows us to grasp objects as universals in a spread-out way; and God, whose understanding grasps universals in a unified way. A stick, for instance, when poked into a conch would feel like pain, when thrown around a dog would register as a particular object to be chased, when presented to a human can become the object for reflection on stick-ness, which may ultimately culminate in the kind of understanding that God had already. Each level embraces those below, bringing more certainty in a way that does not change the object grasped: a stick is a stick, even if a dog has a better grasp of it than a conch does. This is what undergirds Philosophy’s argument that God’s foreknowledge does not necessitate events. Moreover, human beings are capable of this complete range of cognition. While we may spend most of our time with reason, we are capable of moving beyond this to understanding. When we do, we rise above our merely human state and grasp the world as God does. In this way, we become gods. On my reading, this is what advances the work’s bigger project, as it pushes the Patient to remember that within him which is immortal. Philosophy’s second conceptual enrichment is to define eternity as “a possession of life simultaneously entire and perfect, which has no end,” in contrast with time, which is characterized by a life that has its moments spread out. Just as unified understanding is preferable to spread-out reasoning, a unified eternal life is preferable to a life spread out in time. It is not that God lacks temporal beings’ ability to change; it is temporal beings that lack God’s ability to hold it all together. To wrap our minds around this, we must view the world from the perspective of eternity. If we do so, then we realize that God’s simultaneous gaze over all of time adds no more necessity to events than a dog’s looking at a stick does. More importantly, by taking this perspective we touch that which is immortal within us, becoming gods however briefly.12

While there might not be much Scripture involved, Cons. lays out a spiritual regimen thoroughly in line with Augustine. On my reading, Cons. is an exercise in kathartic virtue. In this it fulfils the role assigned to philosophy in De quant. an.: one step on the way to seeing God. Given God’s ability to operate through sacraments and more hidden means, it may even be an unnecessary step. But it is still a useful one. Given the circumstances of its composition, Cons. shows us in particularly stark relief the role of ethical thought in this period: the first-person project of reorienting one’s life around the eternal.

1.3 Alcuin

In terms of philosophical production, not much happened in the century or two following Boethius’s death. Seeking to rebuild the high culture through which Augustine and Boethius had moved, Charlemagne (742–814) established schools in cathedrals and monasteries, using classical learning as preparation for the study of Holy Scripture. Alcuin of York (735–804) was central to this project, which combined theoretical questions of curriculum design with practical challenges of producing accurate copies of texts.

1.3.1 De Virtutibus et Vitiis Liber

Alcuin’s Book on Virtues and Vices is dedicated to a certain Count Guy, “to arouse zeal for eternal blessedness” (De virt. 5–6). Since Guy is “busy with secular matters,” Alcuin neatly lays it out as a “handbook” (46), holding up Scripture as a mirror for the reader to consider himself in (11). The result is something like a second-person spiritual exercise which walks through lists of the kinds of virtues one finds in Scripture: faith, charity, and hope (8–10); almsgiving, chastity, and avoiding fraud (23–25); and the “eight principal vices” (33), which are conquered by eight holy virtues: “pride by humility, greed by abstinence, fornication by chastity, avarice by wisdom, anger by patience, weariness by constancy of good works, bad sadness by spiritual joy, vainglory by the charity of God” (42).

1.3.2 Disputatio de Rhetorica et de Virtutibus

At first glance, Alcuin’s Dialogue on Rhetoric and the Virtues seems to advance far less ethical theorizing than De virt. does. The bulk of this dialogue consists in Alcuin walking Charlemagne through the five parts of Rhetoric: invention (4–45), arrangement (36), style (37–38), memory (39), and delivery (40). The work closes with a brief discussion of the virtues’ four “roots” (radices): prudence, justice, courage, and temperance (40–47). Ethically charged insights into character, motive, and the nature of law are scattered throughout the discussion of Rhetoric, particularly in the section on Invention, or “the devising of subject matter, either true or apparently true, which makes a case convincing” (4).13 Yet it is a systematic exposition of rhetorical principles, rich with distinctions and sub-distinctions, that drives the discussion. The closing discussion is equally tidy, marching dutifully through the four virtues from philosophical (44–46) and Christian (47) perspectives.

The work’s two main sections, while rather dry on their own, become interesting when juxtaposed. Insights scattered throughout the discussion of rhetoric are gathered together and refocused within the closing discussion of virtues. For the moderate person, principles of delivery will come naturally (42–43). Similar connections may be drawn between other virtues and rhetorical principles. The concluding Christian look at the virtues brings the focus even tighter, grounding the four virtues in the love of God and neighbor. Such love may “purify” the soul, helping it “fly back from this troubled and wretched life to eternal peace.” It is thus only at the end that we discover the work’s main project, as a dialogue, “which had its origin in the changing modes of civil questions, [that] finds thus an end in eternal stability” (47).

1.4 Eriugena, Periphyseon

Two generations after Alcuin, Charlemagne’s grandson, Charles the Bald, commissioned John Scottus Eriugena (815–877) to translate into Latin the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. This enigmatic author, probably a fifth-century Syrian monk, adopted the literary identity of a first-century Athenian who converted to Christianity upon hearing Paul’s sermon on the unknown God (Acts 17:34). Pseudo-Dionysius’s negative theology develops the Platonist idea that God is beyond human comprehension and thus is described better through denials than through affirmations. This provides a skeptical challenge of a sort, which throws into question the whole Augustinian project of seeking happiness in the understanding of God. As Platonists, Augustine and Boethius occasionally nod to the idea that God is beyond the ability of human beings to grasp; yet in their main lines of thought, Augustine was happy to equate God with Being and Truth as the ultimate object of human contemplation (Conf. 7),14 and Boethius continued the project with his account of divine simplicity (Cons. 3). In short, both figures based their ethical theories on the idea that human contemplation of God is the ultimate end of human life. Negative theology throws all of this into question by claiming that God, the One, exceeds even the highest of human cognitive faculties. The best we can hope for is to put knowledge aside and strive to become one with the One through a mystical loss of self. Eriugena’s Periphyseon (On Nature) seeks to reconcile Eastern mysticism and Western rationalism via some of the most elaborate theory construction since Boethius.

Periphyseon has rightly been described as a “summa of reality” (Carabine Reference Carabine2000, 17). The dialogue between Teacher and Student opens with a fourfold division of nature (1.1): that which creates and is not created (God as the Source of all creation), that which is created and creates (the primary causes, which are more or less Platonic forms), that which is created but does not create (effects of the primary causes; more or less the sensible world), and that which is neither created nor creates (God as the End of all creation). Each division of nature is assigned a book, with two books for the last. This simple scheme, however, provides the framework for the work’s deeper structure (3.3), which moves through logic, theology, physics, and ethics, while simultaneously following a Platonist emanation scheme as all things process from and return to the One. Since God is incomprehensible, book 1 lays out a logic whereby we may make metaphorical assertions about God by attributing created effects to their Creator. This allows us to say that God is Good, Being, Truth, and whatever else Augustine and Boethius attributed to him. Strictly speaking, though, God is none of these, not because he lacks such properties but because He exceeds them: God is Good to such a degree that our concept of Goodness falls short. That said, all creation gives finite expression to its infinite Creator through a series of “theophanies.” Book 2 lays out the first of these, the primordial causes, “which the Greeks called ideas or forms” (2.36)15 and which lie eternally in the Word of God. Book 3 argues that corporeal bodies are merely bundles of these intelligible ideas (3.7–8), and undertakes a heavily allegorical reading of Scripture, finding this metaphysical scheme in the account of creation in Genesis. Book 4 proceeds to the creation of humanity. Here Augustine’s and Boethius’s habit of comparing human cognitive faculties to non-human creatures’ (plants, conches, etc.) is put to the novel task of arguing that all creation is contained within human nature. While the human soul is one, it is called “intellect” when it approaches the Divine Essence, “reason” when it considers created causes, “sense” when it looks to created effects, and “vital motion” when it tends to a body. This account of humans as metaphysical straddlers underlies what we might call Eriugena’s “negative anthropology.” Just as God is Truth and not (because exceeding) Truth, man (homo) is animal and not (because exceeding) animal (4.5). As the image of God, human nature is infinite and thus ultimately unknowable (4.7). Because of the Fall, however, we have forgotten our exalted status, being weighed down by the earthly bodies given as a punishment for sin.

Book 5 completes Eriugena’s allegorical reading of Genesis, explaining how all creation will be perfected by returning to its Creator. This is accomplished by reversing the order of creation (5.20–40). The process starts as humanity’s earthly body is exchanged for its original spiritual body. Given that all creation is contained in humanity, the rest of creation comes along for the ride. Given that all bodies, even spiritual ones, are ultimately ideas, these spiritual bodies will then turn into ideas in the mind of Christ. At this point, all humans will have returned to Paradise, which is simply the contemplation of God. Those who would rather be attending to temporal affairs won’t like it much (this is Eriugena’s version of eternal damnation). Others will pass even beyond this understanding and become, through an ineffable union, one with God through the process of “deification” (5.36–38). Given God’s infinity, this process will never be completed; rather each of us will strive toward an unattainable goal as much as our individual natures allow. Given that “God Himself is both the Maker of all things and is made in all things” (3.9), our coming to know God is also God’s coming to know Himself through his theophanies. We humans will not, however, lose our individuality; rather, to borrow an image from Pseudo-Dionysius, we will be like the light of several lamps combining in one without losing their individual identity (5.8–13).

In short, Eriugena makes humanity the linchpin of cosmic salvation. In this, we find the tension between civic and contemplative virtue finally broken in favor of the latter. Augustine and Boethius sought to integrate civic virtue within a broader scheme. Even Alcuin was content to allow this-worldly advice to sit side-by-side with a call to eternal goods. For Eriugena, not just humanity but all creation finds its ultimate happiness in humanity’s contemplation of God.

1.5 Conclusion: From Classical to Medieval

The content of Eriugena’s Christian Platonism – grades of goods, the primacy of contemplation, account of evil – clearly has much in common with that of Augustine and Boethius. Yet the works of these earlier figures start from the bottom and seek to turn the mind back to God. Pseudo-Dionysius’s influence leads Eriugena to start from the top and trace the procession of all things from the One as a way of setting the stage for the return of things to their origin. In following Pseudo-Dionysius’s lead, Eriugena loses Augustine’s introspective, first-person approach. While Periphyseon follows De lib. arbit. and Conf. in using philosophical reasoning to prepare the way for reading Scripture, the mode of philosophical reasoning is markedly different. Augustine starts with personal experience and uses it to make sense of the broader world. Eriugena starts with the structure of the world – arrived at through a combination of reason and authorities – and uses it to make sense of personal experience. Whether we think this is a change for the better or the worse, Periphyseon provides a model for Aquinas’s Summa in a way that Conf. or Cons. never could, marking a midpoint between scholasticism and the classical world.