During most of the 1960s, it was easy to view the musical as hopelessly out of touch with contemporary America. Even with three Broadway blockbusters opening in the same year (1964) – Fiddler on the Roof, Hello, Dolly! and Funny Girl – and the film version of My Fair Lady walking away with eight Academy Awards – it seemed apparent to some that the Golden Age of Musical Theatre had staged its own grand finale as these works neither reflected nor commented on the turmoil of the 1960s; they were escapist and nostalgic. With the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy (1963), Martin Luther King (1968) and Senator Bobby Kennedy (1968), and the escalating war in Vietnam, the world was a different place from the comparative calm of the 1950s. In 1964, the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show for the first time, heralding with electronic chords that the British invasion was in full force, and rock ’n’ roll was here to stay. As urban centres across the county fell into disrepair, many downtown theatres were abandoned (often to the wrecking ball) and the road business of touring musicals began to decline. Financially and artistically, the fabulous invalid was not in very good shape.

When Hair arrived on Broadway in 1968, the Great White Way at last embraced a musical whose music and sentiment reflected some of the headlines of its day, and it was staged in a way that distanced itself aesthetically light years away from other musicals playing around Times Square. With the New York premieres of Stephen Sondheim’s Company (1970), Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1971), Michael Bennett’s A Chorus Line (1975) and John Kander, Fred Ebb and Bob Fosse’s Chicago (1975), several new artists found audiences for their disparate visions of what a musical could be, sing and/or dance about. Experimentation continued as the concept musical, the jukebox musical, the revisal, the dansical, and the megamusical came to be. Despite rising ticket prices, theatre attendance began to climb both in New York and on the road. While movie musicals virtually disappeared from the silver screen after Cabaret (1972) and Grease (1978), the stage musical continued to attract audiences even as it experimented with new forms and structures. Truly, rumours of its demise were grossly exaggerated.

Changes that occurred in the American musical at the end of the twentieth century made it clear that while twenty-first century musical theatre owed much to the past, it was creating sub-genres which would have been unrecognisable to its original creators such as Cohan, Kern, Berlin, Gershwin, Hart and Fields. In order to explicate the musical at the dawn of the twenty-first century, we will first look at musical theatre genres that have their roots in the past, then move to new forms which emerged around and after 2000.1 Finally, we will explore the changing roles of directors, choreographers, actors and producers as musical theatre explores new options in the twenty-first century.

The Operetta Musical

One of the many antecedents of musical theatre is the operetta – epitomised by the work of Gilbert and Sullivan – the genre in which Rudolf Friml, Sigmund Romberg, Victor Herbert and sometimes Jerome Kern operated. (See Chapters 4 and 5.) In traditional operetta, the music will be well crafted, and though the plots and even the sentiments may sometimes seem silly, the musical result is likely to be glorious. A prime requisite is well-trained semi-operatic voices. More contemporary derivations of the operetta can be heard in Raphael Crystal’s Kuni-Lemi (1984), Frank Wildhorn’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1997), Jeffrey Stock’s Triumph of Love (1997) and Michael John LaChiusa’s Marie Christine (1999). These late twentieth-century operettas were not marketed as such, since producers no doubt wanted to avoid anything that might sound old-fashioned. Similarly, Sondheim did not label his own work thus, but A Little Night Music (1973), Sweeney Todd (1979) and Passion (1994) fall into this category. Opera companies often undertake stagings of these almost-an-opera musicals/operettas.

Commissioned by Philadelphia’s American Music Theatre Festival in 1994, Floyd Collins belongs in this category, albeit a ‘pocket operetta’ needing only thirteen performers. Based on the true story of a Kentucky man who was trapped in a cave in 1925 for sixteen days, the work features a score by Adam Guettel and a book by Tina Landau. While one reporter visited and interviewed Collins eight times, efforts to save him failed. Before he was discovered dead, an enormous media circus sprung up outside the Sand Cave. When Floyd Collins opened off-Broadway at Playwrights Horizons in 1996, Ben Brantley of the New York Times found the work to exhibit ‘good faith, moral seriousness and artistic discipline’; nevertheless he also thought it ‘half realized’.2 Responding to a 1999 revival at the Old Globe in San Diego, Rick Simas positioned Guettel with Bernstein and Sondheim – as ‘one of the most innovative composers to write for the musical theatre’ – and found Landau’s book and direction to be ‘fresh’ and ‘exciting’.3

The son of Mary Rodgers (Once Upon a Mattress) and grandson of Richard Rodgers, Guettel certainly enjoys the prestige of belonging to an American musical theatre dynasty. While Floyd Collins has its cult followers, Love’s Fire and Saturn Returns (aka Myths and Hymns, 1998) generated more good press. Winning Tony Awards for Best Original Score and Best Orchestrations (with Bruce Coughlin and Ted Sperling) for The Light in the Piazza (2005) secured Guettel’s place in history. In this lush, romantic score, Guettel created a soundscape much closer to Passion than to conventional musical theatre. Guettel’s recent projects have yet to reach the stage (The Princess Bride; Millions; The Invisible Man; Days of Wine and Roses) for various reasons, but he remains active in the field.

The Integrated Musical

Shows with a coherent, strong libretto that create a theatrical world where the focus is on story and character, and songs are constructed to further plot and character development, are alive and well. Productions such as Ragtime (1998), Hairspray (2002), Avenue Q (2003), The Drowsy Chaperone (2006), The Book of Mormon (2011) and Something Rotten! (2015) continue this fine tradition. While the Golden Age of Musical Theatre is often seen as the maturation of the integrated book musical, musical theatre creators are still drawn to the proven efficacy of this form.

The Pop/Rock Musical

For most of the twentieth century, musical theatre supplied many of the popular songs of the day. With the advent of rock ’n’ roll, however, musical theatre composers were slow to adopt this genre as rhythm had replaced melody as the unifying element of a song, and lyrics often took a back seat to percussion. For these reasons, most conventional Broadway composers veered away from rock. As a result, it is generally composers new to Broadway or the West End who write the majority of pop/rock musicals; unhappily, these writing team teams tend to create only one successful work. (See Chapter 14 for more on rock musicals.) Where are the follow-up hits by Galt McDermott (Hair, 1968), Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey (Grease, 1972), Carol King (Really Rosie, 1980), Roger Miller (Big River, 1985), Stew (Passing Strange, 2008), Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova (Once, 2012) and others? While such musicals enjoyed long runs, they appear to be one-offs.

The exceptions to this one-hit trend are Stephen Schwartz, Elton John, David Yazbek, Frank Wildhorn, Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey, who have brought numerous contemporary pop/rock musicals to the Broadway stage. Following Godspell (1971), Schwartz penned successful Broadway musicals – Pippin (1972), The Magic Show (1974) – and supplied the lyrics to three animated film musicals (Pocahontas, 1995; The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1996; Enchanted, 2007) and music and lyrics to another (The Prince of Egypt, 1997) before he wrote the blockbuster Wicked (2003). (See Chapter 1 for more on the creation of Wicked.) Elton John was certainly no stranger to popular prestige, but even his most ardent fans were probably surprised by the vengeance with which he conquered the stage musical. Elton John and Tim Rice’s film The Lion King (1994) became a phenomenal stage sensation in 1997 and then John began writing directly for the stage, starting with Aida (lyrics by Tim Rice) in 2000, Billy Elliot: The Musical (lyrics by Lee Hall) in 2005 and Lestat (lyrics by Bernie Taupin) in 2006. Only Lestat failed to connect with critics and audiences.

Having been recorded by a number of popular groups and the composer of scores for television, David Yazbek came to musical theatre by adapting for the stage the 1997 British hit film The Fully Monty. Teaming up with veteran librettist Terrence McNally, the stage musical ran for 770 performances. Yazbek returned to Broadway with the stage musical adaptation of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (2005; 627 performances), this time collaborating with librettist Jeffrey Lane. On the other hand, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (2010), closed after 69 performances. Along with Elton John, Yazbek is a successful pop songwriter who made the transition to musical theatre, proving that he can write for character and keep his award-winning aesthetic of the engaging, contemporary pop song. Another pop song composer who has had success on Broadway is Frank Wildhorn, who had three musicals running simultaneously on Broadway in 1999: Jekyll & Hyde (1997), Scarlet Pimpernel (1997) and The Civil War (1999).4 These were followed by Dracula (2004), Carmen (Prague, 2008), Count of Monte Cristo (Switzerland, 2009), Wonderland (2011), Bonnie and Clyde (2011) and a 2013 revival of Jekyll & Hyde, all of which had short runs.

Fellow participants in the BMI Musical Theatre workshop, Brian Yorkey (librettist, lyricist) and Tom Kitt (composer, conductor, orchestrator) have collaborated on two hit Broadway musicals: Next to Normal (2009; 733 performances; Pulitzer Prize) and If/Then (2014; 401 performances). Currently playing the regional circuit (Signature Theatre, La Jolla Playhouse, Cleveland Playhouse, Alley Theatre), Disney’s Freaky Friday features music by Kitt, lyrics by Yorkey and a book by Bridget Carpenter. Yorkey penned the book for Sting’s The Last Ship (2014), while Kitt has been represented on Broadway by Bring It On (2012, with Amanda Green, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Jeff Whitty), and High Fidelity (2006, with Amanda Green, and David Lindsay-Abaire).

Related to the pop/rock musical is the ‘jukebox musical’. These revues and musicals take advantage of previously written music, as opposed to the previously mentioned productions, which feature original music. Similar to the revue, the jukebox musical is an assemblage of pre-existing songs where the emphasis is clearly on the songs, not on plot and/or character. Unlike earlier elaborate revues put on by the likes of Ziegfeld and George White, late-twentieth century revues tend to focus on the music of one composer and generally do not showcase stars. With the exception of Bubblin’ Brown Sugar (1976), Sophisticated Ladies (1981) and Black and Blue (1989) – which featured large casts, elaborate sets, and demanding choreography – most late-twentieth century jukebox musicals were small, intimate affairs: Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1978, music of Fats Waller), Five Guys Named Moe (1992, songs by Louis Jordan), Smokey Joe’s Cafe (1995, songs by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller), Dream (1997, lyrics by Johnny Mercer) and Sondheim on Sondheim (Reference Sondheim2010, songs by Stephen Sondheim).

One variation of the jukebox musical/musical revue is the ‘disguised pop/rock concert’. In this format a series of pop or rock hits are staged as a concert; the evening invariably ends with an uninterrupted series of numbers performed by the cast. Some of these musicals are semi-biographical: Beatlemania (1977, Beatles), Eubie! (1978, Eubie Blake), Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story (1990), Leader of the Pack (1985, Ellie Greenwich) and Jersey Boys (2006, Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons). Others are less concert and more biography, often using songs a singer and/or songwriter made famous and include The Boy from Oz (2003, Peter Allen), Good Vibrations (2005, Beach Boys), Fela! (2009, Fela Kuti), Beautiful, The Carole King Musical (2014) and On Your Feet! (2015, Gloria Estefan).

Another genre of the jukebox musical that utilises pre-existing songs, but creates a plot around them, is the ‘story album musical’ or the ‘anthology with a story’ musical. (These contain plots where the story is not a biography of the songwriter.) Some incorporate songs written originally for musical theatre, and others use pop songs. Two of the most popular of the former variety are the ‘new’ Gershwin musicals My One and Only (1983) and Crazy for You (1992). Crazy for You contains five songs from Girl Crazy, four from A Damsel in Distress, three from the film Shall We Dance and six other Gershwin tunes. Ken Ludwig wrote a new libretto; directed by Mike Ockrent and choreographed by Susan Stroman, the musical was very popular with audiences. Similarly, two plot musicals have created new characters and contexts for songs already written by Stephen Sondheim: Marry Me a Little (1980) and Putting It Together (1999).

Jukebox musicals featuring pop songs (and non-biographical plots) include the international sensation Mamma Mia! (1999); the Billy Joel/Twyla Tharp dansical, Movin’ Out (2002); Queen’s We Will Rock You (2002); and Green Day’s American Idiot (2010). Like the biographical or rock concert jukebox musical, musicals in this niche enjoy the fact that many potential theatre patrons already know the music very well. During their ten years of existence as a band (1972–82), the Swedish group ABBA had fourteen singles in the Top 40 (four in the Top 10), and record sales that exceeded 350 million units. British playwright Catherine Johnson took twenty-two of their greatest hits and fashioned a plot around them about a young woman who wants her father to give her away at her wedding; problem is, mom doesn’t know which one of three men she was seeing at the time might be Sophie’s dad. The NYC production closed in 2015, after fourteen years (5,773 performances), making it the eighth-longest running musical in Broadway history. Playing for six years (2003–9) in Las Vegas, it is the longest-running full-length Broadway musical ever to play the city of chance. Mamma Mia! has been performed in eighteen languages in more than forty countries to more than 54 million people; it has become an entertainment industry in its own right, with worldwide grosses exceeding $2 billion. A $52 million film version of Mamma Mia! was released in 2008, starring Meryl Streep, earning $609.8 million.

Black Musicals

The black musical is a subdivision of the pop/rock musical, featuring music that reflects jazz, blues, gospel, funk, reggae, rap or Motown. Examples are Gary Geld’s Purlie (1970), Judd Woldin and Robert Brittan’s Raisin’ (1973), Micki Grant’s Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope (1972) and Your Arms Too Short to Box With God (1976), Charlie Small’s The Wiz (1975), Michael Butler’s Reggae (1980), Gary Sherman’s Amen Corner (1983) and The Color Purple (2005) with book by Marsha Norman and score by Brenda Russell, Allee Willis and Stephen Bray. Special mention should be made of Mama, I Want to Sing! (1983), which opened at the 632-seat Heckscher Theater in Harlem. Written by Vy Higginsen, Ken Wydro and Wesley Naylor, the original production ran 2,213 performances, closing after eight years only because of a lease dispute. Two sequels – Mama, I Want to Sing II (1990) and Born to Sing! (1996) – a six-month run on the West End of Mama in 1995, and several world tours brought the musical to millions. The original Mama cost $35,000 but grossed $25 million in its first five years. Higgeninsen (wife) and Wydro’s (husband) family business earned $8.7 million in 1988; they are one of the most successful black-owned enterprises in America.

The jukebox musical also proved to be a popular form for African American songwriters and performers. Notable examples include Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1978), a celebration of songs by Fats Waller; Sophisticated Ladies (1981), showcasing the music of Duke Ellington; Black and Blue (1989), an anthology of songs by African Americans that were popular in Paris between the two world wars; and Five Guys Named Moe (1992), focusing on songs by Louis Jordan. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the demographics of the Broadway audience, few producers in the twentieth century attempted to bring rap music to Broadway, the exception being Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk (1996). Conceived and directed by George C. Wolfe, the appeal of Funk had more to do with the innovative choreography and performance by Savion Glover than the music.

Having sold more than 75 million records worldwide, rapper Tupac Amaru Shakur (1971–96) was hailed by Rolling Stone in 2010 as one of the ‘100 Greatest Artists’ of all time. But the jukebox musical Holler If You Hear Me (2014), featuring his music failed to connect with audiences (thirty-eight performances). More successful was Stew and Heidi Rodewald’s Passing Strange, which ran for 165 performances during its Broadway run in 2008. Spike Lee filmed the stage performance, releasing a feature film of the same name in 2009.

Latino/a Musicals

In the twenty-first century, Lin-Manuel Miranda single-handedly changed what the Broadway musical could sound like. A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama, In the Heights (2008) not only brought a story (by Quiara Alegris Hudes) about Latino immigrants in New York City to the Great White Way, its score (by Lin-Manuel Miranda) is an intoxicating gumbo of hip hop, salsa, merengue and more. Winning the Tony Award for Best Musical, the show went on to garner 1,185 performances on Broadway, a national tour and productions around the world. But the success of In the Heights (2008) was overshadowed by the juggernaut that was Miranda’s Hamilton (2015) when it opened off-Broadway at the Public Theatre. After its sold-out limited engagement, the musical opened on Broadway to rapturous reviews and $27.6 million in advance ticket sales. Starring Miranda as Alexander Hamilton, with his book, music and lyrics, Miranda recast American history with actors of color, and tells the story of their creation of a new country in rap, hip hop, and R&B ballads. As Ben Brantley of the New York Times enthused, Hamilton is ‘proof that the American musical is not only surviving but also evolving in ways that should allow it to thrive and transmogrify in years to come’.5

New York City census information from 2014 indicates that 28.6 per cent of the metropolitan population was Hispanic or Latino, and that 30 per cent of Broadway audiences come from the New York metropolitan region. Given this demographic information, it seems surprising that the Latino musical did not find an audience on Broadway in the twentieth century. Valiant attempts include Luis Valdez’s Zoot Suit (1979) and Paul Simon’s Capeman (1998). Arne Glimcher’s The Mambo Kings (2005) closed in San Francisco before it even came to New York.6 More successful have been dance-based revues such as Tango Argentino (1985, revived 1999), Flamenco Puro (1986) and Forever Tango (1997, revived 2004) and off-Broadway productions such as El Bravo! (1981) by José Fernandez, Thom Schiera and John Clifton; ¡Sofrito! (1997), a bilingual musical by David Gonzalez and Larry Harlow with a Caribbean-influenced score that played to sold-out audiences at New York’s New Victory Theater; and Gardel: The Musical (2006), a bio-musical about Argentine tango music legend Carlos Gardel. Since the only two genres of music that saw increases in CD sales in 2004 were country and Spanish, it was only a matter of time before savvy theatre producers moved into this market, especially since Miranda’s In the Heights (2008) and Hamilton (2015) proved that there is a Broadway audience for Latin and contemporary music. One might also expect more examples of the Spanish light opera, or zarzuela, to begin to appear in the repertoire of English and American opera companies. (See Chapter 3 for more on the zarzuela in North America.) Hamilton and On Your Feet! (2015) – a jukebox musical which tells the story of Emilio and Gloria Estefan – might be the beginning of a renaissance of Latino/a Musicals on Broadway.

Asian Musicals

While such shows as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song (1958) and Boublil and Schonberg’s Miss Saigon (1989) have given Asian American performers long-running hits in which to perform, there have been very few Asian American–authored musicals. Leon Ko and Robert Lee’s Heading East (1999), Making Tracks (by Welly Yang, Brian Yorkey, Woody Pak, Matt Eddy, 1999), The Wedding Banquet (book and lyrics by Brian Yorkey; music by Woody Pak, 2003), A. R. Rahman’s Bombay Dreams (2004) and Maria Maria (book and lyrics by Hye Jung Yu, music by Gyung Chan Cha, 2006) are rare exceptions. Though the original music was kept, David Henry Hwang wrote a new libretto for The Flower Drum Song when it was revived on Broadway in 2002.

From a chance encounter between Star Trek star George Takei and songwriters Jay Kuo and Lorenzo Thione in 2008, it was a long road to Broadway for Allegiance (2015), a new musical which tells the story of a shameful piece of American history, when more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly interned in prison camps during World War II. Written by Jay Kuo (music, lyrics and book), Lorenzo Thione (book) and Marc Acito (book), and directed by Stafford Arima, Allegiance had a fifty-two-performance successful run at San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre in 2012, but was stalled until a suitable Broadway house opened up in 2015. Along with the star power of Takei, Tony Award winner Lea Salonga and Telly Leung, the production also marked the debut of Telecharge Digital Lottery, where patrons could apply online for $39 rush tickets. Failing to find an audience, the musical closed after three months.

Folk/Country Musicals

In the folk/country/western music genre, notable past successes include Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner’s Paint Your Wagon (1952), Carol Hall’s Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1978), Barbara Damashek and Molly Newman’s Quilters (1984) and Roger Miller’s Big River (1985). Nevertheless, even though country music sales have been rising along with Spanish CD music sales, there has yet to be a successful twenty-first-century folk or country musical. While the Broadway debut in 2014 of Jeanine Tesori’s Violet (1997) featured a highly praised score which incorporated gospel, blues, country, bluegrass and honky-tonk, its Broadway run of 128 performances owed more to the star power of Sutton Foster than to its sound.

The Non-linear or ‘Concept’ Musical

In contrast to the integrated musical, the concept musical rejects a traditional storyline. Instead the emphasis is on character, or on a theme or a message. And since they are ‘thought pieces’, concept musicals are rarely comedies. Early experiments with the form include Allegro (1947), Love Life (1948), Man of La Mancha (1965), Cabaret (1966), Company (1970) and A Chorus Line (1975). After two successful off-Broadway musicals (First Lady Suite, 1993; Hello, Again, 1994), composer/lyricist Michael John LaChiusa was heralded as one of the promising musical theatre creators who were forging new forms. But the box-office failures of The Petrified Prince (1994), Marie Christine (1999) and The Wild Party (2000) seemed to indicate that Broadway audiences were not yet ready to embrace his experiments with the concept musical.

Based on Joseph Moncure March’s 1926 poem, The Wild Party inspired LaChiusa and co-librettist/director George C. Wolfe to musicalise this depiction of jazz-age debauchery.7 Produced by the New York Shakespeare Festival, the production opened on Broadway in 2000 with a top-tier cast (Eartha Kitt, Mandy Patinkin and Toni Collette) and was nominated for seven Tony Awards. Set in the twilight of the vaudeville era, the show is conceptualised around a series of vaudeville turns, complete with signs announcing the titles of the acts. New York Magazine’s John Simon found the piece to be ‘a fiasco’ since it appeared to him to be a series of ‘random incidents that refuse to mesh’.8 Similarly, Ben Brantley (New York Times) described the evening as ‘a parade of personalities in search of a missing party’.9 Unable to find an audience, The Wild Party closed after sixty-eight performances, losing all of its $5 million capitalisation.

While the concept musical fits very well within the tenets of postmodernism, musical theatre audiences tended to be more conservative, preferring a linear story and hummable tunes to radical experimentation. The box-office failures of Jerry Herman’s Mack and Mabel (1974, 66 performances), Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along (1981, 16 performances) and Jeanine Tesori’s Caroline, or Change (2004, 136 performances) serve as warning beacons to those who would argue that audiences want challenging fare. Even though many critics considered each of these musicals to be some of the finest work that these creative teams in question had ever written, they failed to find a loyal audience.

The concept musical that might buck the trend of critically acclaimed shows that perform poorly at the box office is Fun Home (2015). Based on the unlikely source material of Alison Bechdel’s 2006 graphic memoir, the musical was a hit off-Broadway at the Public Theatre in 2013, extending its run several times. Winning numerous awards, it was also a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize, unusual for the first Broadway musical with a lesbian protagonist. With music by Jeanine Tesori and book and lyrics by Lisa Kron, Fun Home tells of Alison’s realisation she is a lesbian, and also learning of her father’s homosexual relationships. Bruce is killed (or commits suicide?) four months after Alison comes out to her parents. Joe Dziemianowicz (New York Daily News) called the musical ‘achingly beautiful’, one that ‘speaks to one family and all families torn by secrets and lies’.10 New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini praised Tesori’s score as a ‘masterpiece’, noting that the ‘vibrant pastiche songs’ and ‘varied kinds of music … a jazzy number for the young Alison in the middle of a rescue fantasy; Sondheim-influenced songs that unfold over insistent rhythmic figures and shifting, rich harmonies’ come together to create ‘an impressively integrated entity’.11 Winning the 2015 Tony Award for Best Musical (in addition to four other awards and eight additional nominations), the show was clearly the darling of critics and Tony voters. Time will tell if it continues to capture audiences. Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron are the first female writing team to win the Tony Award for Best Original Score.

One variation of the concept musical that has found appreciative audiences is the self-reflexive musical. While the ‘backstage musical’ has long been a popular genre – Kiss Me, Kate (1948), Gypsy (1959), Dreamgirls (1981), The Producers (2001) – the self-reflexive musical is not just about show business and/or musical theatre; it asks the audience to believe that the production of the musical which they are watching is happening in real time in front of them. Little Sally interrupts Office Lockstop as he attempts to introduce the audience to Urinetown, the Musical (2001), with questions as to why the musical has such an ‘awful’ title, especially when the music is so ‘happy’. When she attempts to understand the seriousness of the water shortage crisis around which the musical’s plot revolves, Officer Lockstock cuts her off, explaining ‘nothing can kill a musical faster than too much exposition’.12 Similarly, in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (2005) and Spamalot (2005), characters often break the fourth wall. The self-reflexive musical can appear as too much of an insider phenomenon – like quoting choreography from West Side Story in Urinetown – suggesting that audiences must know a great deal about musicals in order to get all of the allusions and jokes. But musical theatre never gets tired of looking at its own reflection, as writers continue to be drawn to the backstage musical, the show-within-a-show, and the self-reflexive musical in works such as The Musical of Musicals: The Musical (2003), The Drowsy Chaperone (2006), Curtains! (2007), [title of show] (2008) and Something Rotten! (2015).

The ‘Dansical’

When Contact won the Tony Award for Best Musical in 2000, it was clear that the dansical had arrived, although director/choreographer Susan Stroman’s work was advertised as ‘a dance play’. Here the emphasis is on dance and the narrative is told through movement since there is generally no dialogue or sung lyrics. As another sign of the new supremacy of the choreographer/director (see Chapter 13), the dansical often does not contain original music. Consider, for example, Big Deal (Bob Fosse, 1986), Dangerous Games (Graciela Daniele, 1989), Chronicle of a Death Foretold (Daniele, 1995), Contact (Stroman, 2000), Movin’ Out (Twyla Tharp, 2003), The Times They Are A-Changin’ (Tharp, 2007) and Come Fly Away (Tharp, 2010). While the form is not new, Susan Stroman and Twyla Tharp can be given credit for almost single-handedly popularising the form. Some critics noted that Tharp had already been on Broadway before with an evening-long dance theatre piece The Catherine Wheel, which had a three-week engagement in 1981.

‘Actor-Musicianship’

Having worked in British regional theatres for several decades, during the belt-tightening of the 1990s, John Doyle was faced with the challenge of directing/producing musical theatre with companies that could no longer afford orchestras. At first he had actors play musical instruments when their characters were not on stage. Then he began to direct the musical in a way that the characters stayed on stage and in character, and so their playing an instrument became another facet of their characterisation. For this reason, Doyle calls his approach ‘actor-musicianship’ as it is ‘a “multi-skilled” way of telling a story’.13 As associate director of the Watermill Theatre, his experiments in this 220-seat theatre in Berkshire attracted critical notice. But when Doyle’s The Gondoliers (2001) and Sweeney Todd (2004) transferred to the West End, more audiences were exposed to these unique revisals. Gondoliers was rewritten with a cast of eight actors to feature a Chicago Mafia family who find themselves in a London Italian jazz cafe, while Sweeney was reduced to a cast of ten performers who all played musical instruments; neither production featured a separate orchestra. When Sweeney Todd moved to Broadway, Doyle won the Tony Award for Best Director of a Musical. Doyle’s refashioned Mack and Mabel transferred to London’s Criterion Theatre in 2006, the same year his Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park production of Company (with new orchestrations by Mary-Mitchell Campbell) moved to Broadway. In 2014, with permission of the Rodgers and Hammerstein estates, Doyle refashioned Allegro into a ninety-minute version with actor-musicians. In these re-imaginings, the guiding hand of the auteur director (and auteur orchestrator) is in the foreground.

The ‘Revisal’

A variation on the director and/or choreographer as auteur is the revival which features a new (or significantly altered) libretto. In the case of these ‘revisals’, the librettist is now the auteur. In 1983, Peter Stone and Timothy S. Mayer crafted a new book to create My One and Only, using many of the songs from George and Ira Gershwin’s Funny Face (1927). Eventually running 767 performances, its commercial success no doubt inspired the creation of the next ‘new’ Gershwin musical, Crazy for You (1992), for which Ken Ludwig wrote a new libretto using Guy Bolton’s basic storyline for the Gershwins’ Girl Crazy (1930). Then in 2012, Joe DiPietro penned the book for the ‘new’ Gershwin musical, Nice Work If You Can Get It, based on material by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse.

The practice of the revisal dates back centuries. When French composer Georges Bizet created Carmen to a libretto by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halevy in 1875, this opera-comique contained spoken dialogue. By the time it opened in Vienna later in 1875, Carmen no longer featured spoken dialogue, but rather recitative devised by Ernest Guiraud, as Bizet had died three months after the opera’s premiere. Oscar Hammerstein II then wrote a new libretto and lyrics in 1943 to Bizet’s music, titling the new work Carmen Jones and setting it in World War II Alabama. The next major reiteration occurred in 1983 when Peter Brook and Jean-Claude Carrière removed the chorus to create La Tragédie de Carmen, and then MTV produced Carmen: A Hip Hopera (2001) starring Beyoncé Knowles and Mos Def, with a hip-hop score by Kip Collins.

When a production of Annie Get Your Gun was being prepared for a 1999 Broadway revival starring Bernadette Peters, the original book by Herbert Fields and Dorothy Fields was significantly revised by Peter Stone to remove the jokes and songs aimed at American Indians. The song ‘I’m an Indian, Too’ was cut and the musical’s subplot was rewritten to feature an interracial couple. Even though Stone’s alterations were made with the permission of Berlins’ and Fields’ heirs, criticism was levelled at Stone and the revival’s producers for changing a work of art. On the other hand, no one missed the racial slurs of the original 1946 show, and with Stone’s new book and galvanising performances by Peters and her replacement Reba McIntyre, this revisal had a very profitable run of 1,045 performances on Broadway and a lengthy national tour.

In 2001, David Henry Hwang wrote an entirely new libretto for Joseph Fields, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s The Flower Drum Song. While groundbreaking in 1958 for humanising a marginalised group in American society, the work nevertheless became perceived as sentimental, a ‘minor’ Rodgers and Hammerstein work. The reviews that greeted the 2001 ‘revisal’ at the Mark Taper Forum were universally positive. Variety applauded Hwang’s ‘wholesale reconstructive surgery’ to the script, calling it ‘an artistic success, revealing a revitalised score and a dramatic complexion that’s far richer than the original’.14 Diane Haithman of the Los Angeles Times noted that Hwang’s changes are not about updating a 1958 musical to twenty-first-century standards of political correctness, instead ‘he plays with Asian stereotypes, rather than eliminate them’.15 The reviews for the New York run were not as positive, and the production only managed a run of 172 performances on Broadway.

When the Gershwin estate approached director Diane Paulus to create a new musical theatre version of the venerable folk opera, Porgy and Bess, detractors (including Stephen Sondheim) pounced on the announcements that the creative team included playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and composer-arranger Diedre Murray, brought on board to flesh out the ‘cardboard cutout characters’ in the libretto. Replacing dialogue for recitative, The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (2011) received mixed reviews, but was nominated for ten Tony Awards, and ran 322 performances, making it the longest-running production of Porgy and Bess to date.

While the producers clearly marketed their productions of My One and Only and Crazy for You as ‘new’ Gershwin musicals (complete with quotation marks), the revisals of Annie Get Your Gun and Flower Drum Song did not have titles that distinguished them from their original incarnations. Unlike various versions of a song recorded by different artists, these revisals are not interpretations of a work of art; they are unique works of art. It is ahistorical and unethical to present a work to audiences under its old title when it contains significant alterations to its original form.

For decades, it has been standard practice to adapt Broadway musicals that were slated to play Las Vegas. Most were trimmed to ninety minutes but retained the design, direction, choreography and so on which made the Broadway run a success. For Phantom – The Las Vegas Spectacular, original director Harold Prince trimmed Andrew Lloyd Webber’s smash hit, The Phantom of the Opera, to an intermission-less ninety-five minutes. Often playing up to ten performances a week, the Vegas version ran from 2006 to 2012 (2,691 performances) in a $40 million theatre at the Venetian. With the London staging nearing its twenty-fifth anniversary, producer Cameron Mackintosh made the unprecedented move to commission a second version of The Phantom of the Opera, while its original staging was still playing in London, New York and other cities around the world. Debuting in 2012 in Plymouth, England, and subsequently touring the UK, the U.S. tour started in Providence, Rhode Island, in 2013, directed by Laurence Connor, with new choreography by Scott Ambler, and new sets designed by Paul Brown. Described by Macintosh as ‘darker and grittier’ than the original 1986 staging, Michael J. Roberts (Showbiz Chicago) found the Connor staging to maintain Phantom as an ‘iconic, moving piece of grand theatre’, with ‘characters more fully developed’ than the original.16 While the tour is still an enormous production – one set unit weighs 10 tons – it can be loaded in and out of a theatre in less time than the original set by Maria Bjornson. Los Angeles Daily News’s Dany Margolies found the new settings to be ‘ravishing’, but the overall production ‘not necessarily improved’.17 As of this writing, neither Lloyd Webber nor Macintosh has indicated if (or when) the Connor revisal will replace the Prince version.

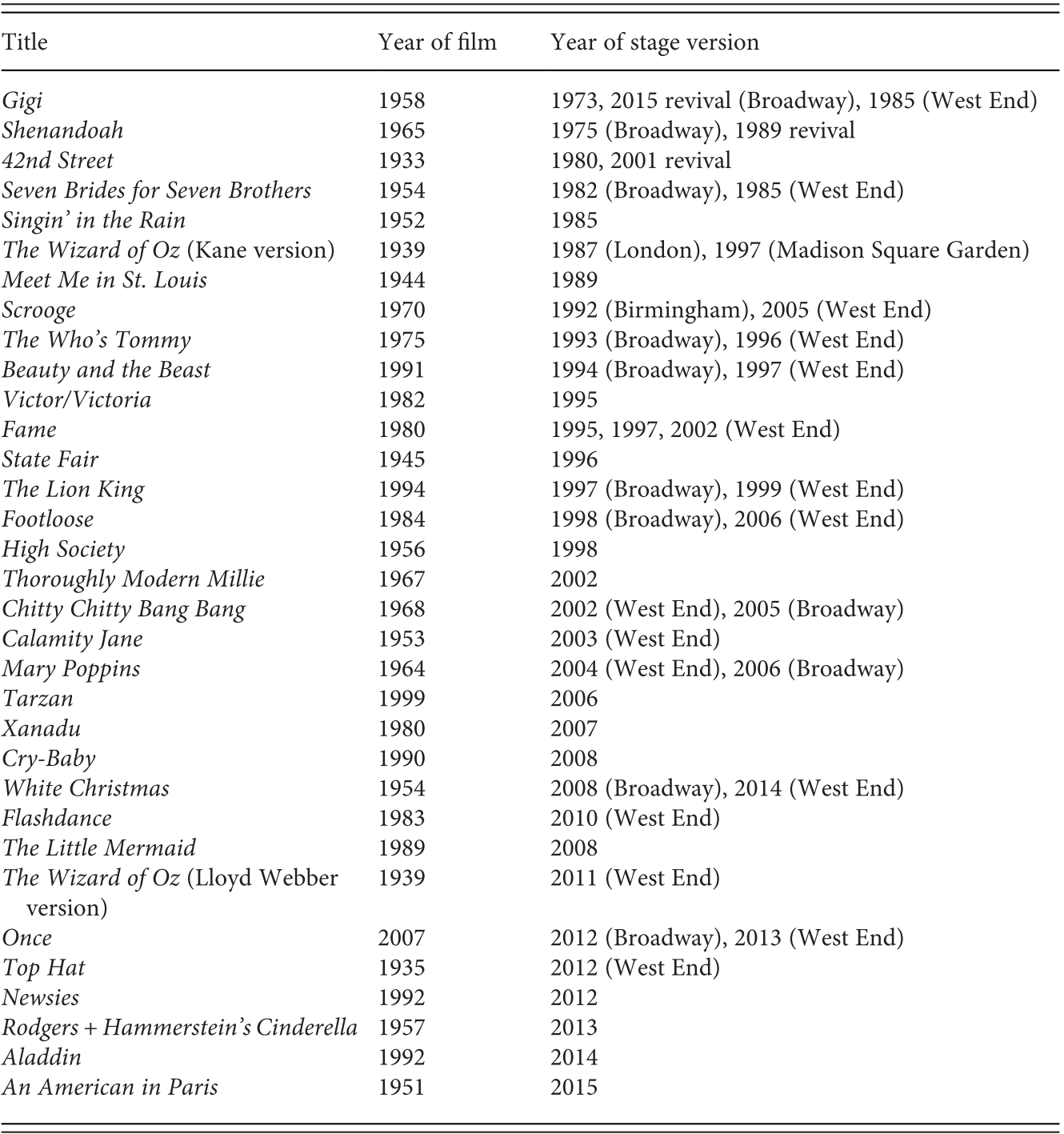

For most of the twentieth century, musical theatre writers not only supplied the nation with many of its hit songs but also many of its top musical films as well. Indeed, perusal of the American Film Institute’s (AFI) list of its twenty-five ‘Greatest Movie Musicals’ reveals that more than half started on the Broadway stage. While the norm has been stage–to–screen transfers, there are a growing handful of musicals that were originally conceived and written for film that have been subsequently reconfigured for the Broadway stage. (See Table 18.1.)

Table 18.1 Selected stage adaptations of musical films (arranged chronologically according to the year of the stage version)

Not all screen-to-stage adaptations have Broadway as their goal. The long-running short-music video format, School House Rock (1973–2009), was adapted into a stage musical Schoolhouse Rock Live! in 1996. Disney Channel’s megahit High School Musical (2006) went from cable television to high school productions within its first year. Curiously, neither one of the stage adaptations of The Wizard of Oz has ever played in a Broadway theatre. A New York run was once seen as an absolute imperative so a production could boast ‘direct from Broadway’ even if it did not have any good reviews to bolster that claim. But these three popular titles purposefully declined a Broadway production, as none of them needed the imprint of a New York production to ‘validate’ them.

Concerning story and characters, a minority of musicals feature an original plot; most are adaptations of source material that first existed as a novel, short story, news article, comic book (Spiderman: Turn Off the Dark), graphic novel, biography, ballet or even a painting (Sunday in the Park with George). A recent trend – which some critics fear has become an epidemic – is the musicalisation of popular films. (See Table 18.2.) A snapshot taken on 1 January 2006 shows thirty-eight productions on Broadway; of the twenty-nine musicals running, nineteen were either made into or from a film.

Table 18.2 Selected stage musicals based on largely non-musical films, some of which feature significant musical sequences (arranged chronologically according to the year of the stage version).

| Title | Year of film | Year of stage musical |

|---|---|---|

| Carnival in Flanders | 1934 | 1953 |

| Silk Stockings | 1939 | 1955 |

| Carnival! | 1953 | 1961 |

| Breakfast at Tiffany’s | 1961 | 1966 (Broadway), 2013 (London) |

| Sweet Charity* | 1969 | 1966 (Broadway), 1967 (West End) |

| Applause | 1950 | 1970 |

| Sugar | 1959 | 1972 (Broadway), 1992 (West End) |

| A Little Night Music† | 1955 | 1973 |

| King of Hearts | 1966 | 1978 |

| On the Twentieth Century | 1934 | 1978, 2015 revival, 1980 (West End) |

| Carmelina‡ | 1968 | 1979 |

| Woman of the Year | 1942 | 1981 (Broadway) |

| Nine§ | 1963 | 1982, 2003 revival, 1996 (West End) |

| Little Shop of Horrors | 1960 | 1982, 2003 revival |

| La Cage aux Folles | 1978 | 1983, 2004 revival |

| Smile | 1975 | 1986 |

| Carrie | 1976 | 1988 (Broadway), 2015 (West End) |

| Grand Hotel | 1932 | 1989 (Broadway), 1992 (West End) |

| Return to the Forbidden Planet | 1956 | 1989 (West End) |

| Metropolis | 1927 | 1989 (West End) |

| The Baker’s Wife | 1938 | 1989 (West End) |

| Prince of Central Park | 1977 | 1989 |

| My Favorite Year | 1982 | 1992 |

| The Goodbye Girl | 1977 | 1993 |

| The Red Shoes | 1948 | 1993 |

| Sunset Boulevard | 1950 | 1993 (West End), 1994 (Broadway) |

| Passion ¶ | 1981 | 1994 |

| Big | 1988 | 1996 |

| Whistle Down the Wind | 1961 | 1998 (West End) |

| Martin Guerre | 1982 | 1996 (West End) |

| Saturday Night Fever | 1977 | 1998 (West End), 1999 (Broadway) |

| The Hunchback of Notre Dame | 1996 | 1999 (Berlin) |

| The Full Monty | 1997 | 2000 |

| The Producers | 1968 | 2001 |

| Peggy Sue Got Married | 1986 | 2001 (West End) |

| Hairspray | 1988 | 2002 |

| A Man of No Importance | 1994 | 2002 (New York), 2009 (London) |

| Sweet Smell of Success | 1957 | 2002 |

| Urban Cowboy | 1980 | 2003 |

| Spamalot ** | 1975 | 2005 |

| Dirty Rotten Scoundrels | 1988 | 2005 |

| The Color Purple | 1985 | 2005 |

| Billy Elliot: The Musical | 2000 | 2005 (West End), 2007 (Broadway) |

| The Wedding Singer | 1988 | 2006 |

| Grey Gardens | 1975 | 2006 |

| Tarzan | 1999 | 2006 |

| Legally Blonde | 2001 | 2007 |

| Young Frankenstein | 1974 | 2007 |

| A Catered Affair | 1956 | 2008 |

| Shrek, the Musical | 2001 | 2008 (Broadway), 2011 (West End) |

| 9 to 5 | 1980 | 2009 |

| Sister Act | 1992 | 2009 (West End), 2011 (Broadway) |

| Priscilla, Queen of the Desert | 1994 | 2009 (West End), 2011 (Broadway) |

| Elf: The Musical | 2003 | 2010 |

| Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown | 1988 | 2010 (Broadway), 2015 (West End) |

| Catch Me If You Can | 2002 | 2011 |

| Ghost: The Musical | 1990 | 2011 (West End), 2012 (Broadway) |

| Bring It On: The Musical | 2000 | 2012 |

| A Christmas Story: The Musical | 1983 | 2012 |

| Leap of Faith | 1992 | 2012 |

| The Bodyguard | 1992 | 2012 (West End) |

| Kinky Boots | 2005 | 2013 (Broadway), 2015 (West End) |

| Bullets Over Broadway | 1994 | 2014 |

| The Bridges of Madison County | 1995 | 2014 |

| Big Fish | 2003 | 2013 |

| Diner | 1982 | 2014 (Washington, D.C.) |

| Made in Dagenham | 2010 | 2014 (West End) |

| Rocky, the Musical | 1976 | 2012 (Hamburg), 2014 (Broadway) |

| Bend It Like Beckham | 2002 | 2015 (West End) |

| Finding Neverland | 2004 | 2015 |

| Honeymoon in Vegas | 1992 | 2015 |

| School of Rock | 2003 | 2015 |

| Mrs. Henderson Presents | 2005 | 2016 |

The genre of the source material is no guarantee of the critical and/or commercial success of a musical, but what the screen-to-stage musicalisation can capitalise on is name recognition. When a film like Footloose comes to Broadway, even a mediocre staging can run for 709 performances in New York, enjoy a long run in Las Vegas, and see numerous amateur productions. But name recognition is certainly not a reliable insurance policy: for every megahit (Little Shop of Horrors, La Cage aux Folles, Hairspray) there is an implosion (The Goodbye Girl, Urban Cowboy, The Bridges of Madison County). In 2002, MGM created ‘MGM On Stage’ to develop and licence films from its catalogue for stage production. Starting with Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, the division has thus far musicalised The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, Legally Blonde and Promises, Promises.

Producers

Producing changed a great deal during the last decade of the twentieth century as the days of the sole theatrical producer disappeared. Legendary solo producers, such as David Merrick, George Abbott, Vinton Freedley, Joseph Papp, Saint Subber and others, were known for their idiosyncratic taste, business savvy and aesthetic fingerprint. Indeed, there is a universal sentiment with the disappearance of the solo producer there was a corresponding evaporation of much risk taking on Broadway. These producers did not just ‘discover’ new musicals; they often assembled a creative team to realise an idea that they had for a musical. Historians Lawrence Maslon and Michael Kantor conclude that ‘whereas once a producer was expected to have some artistic acumen, the job now was about cultivating cash’.18 As costs to mount a new musical increased, producers beginning in the 1960s began to experiment with often bold ventures in order to secure a profit from their ventures. One of Merrick’s innovations was celebrity casting. When the originating star of a musical left the show, it was the Broadway convention that that he or she would be replaced by an unknown (and cheaper) talented performer. Merrick’s Hello, Dolly!, starring Carol Channing, started off with a bang, winning a record ten Tony Awards in 1964. When Channing left the show, Merrick engaged Ginger Rogers, Martha Rae and then Betty Grable to essay the role. Merrick then prepared an all–African American cast, starring Pearl Bailey and Cab Calloway, which attracted new publicity and new audiences. Back to a Caucasian cast, Phyllis Diller and then Ethel Merman performed the role of Mrs Dolly Gallagher Levi to realise a run of 2,844 performances (almost six years). For Merrick, the idea was not to get patrons to buy a ticket once, but to create reasons for them to return. And by casting wildly different stars in the role, he also ensured that different demographics might be attracted to his show. This ‘revolving door’ star casting ploy has been employed by producers Fran and Barry Weissler with equally impressive results in the 1994 revivals of Grease, and later Annie Get Your Gun, Wonderful Town and the most lucrative to date, Chicago (1996), which was still running in 2017.

Like Irving Berlin, Frank Loesser, and Rodgers and Hammerstein – in addition to prodigious accomplishments as an artist – Andrew Lloyd Webber has enjoyed much success as a producer. From 1986 to 1990, Lloyd Webber sought to eliminate the ‘backer’s audition’ where the composer and lyricist sing through the score with the hope of enticing well-heeled angels to invest in their show. Instead, he sold shares in his Really Useful Group, so that investors would be gambling that any future Lloyd Webber property would be popular and run a profit, or become a blockbuster like Cats or The Phantom of the Opera and make a great deal of money. Ultimately, the strain of maintaining a publicly held company led Lloyd Webber to buy back the outstanding shares in 1990. Canadian producer Garth Drabinsky similarly took his company Livent, Inc. public in 1993, but the company collapsed in 1998. Drabinsky was convicted of fraud and forgery in 2009.

For a 2006 London revival of The Sound of Music, Lloyd Webber hit upon the novel idea of creating a reality television programme centred on the musical’s casting. The viewing audience voted on the contestants at each stage, and the actors with the fewest votes were eliminated. Carried on BBC for eleven hours, How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria? was very successful in terms of generating audience interest, as the advance ticket sales topped £10 million before opening. And while 7.7 million viewers witnessed the final showdown between the top three finalists and 2 million voted to extend a six-month contract to Connie Fisher, it seemed nothing more than a publicity stunt, but twenty-three-year-old Fisher received great reviews. It was inevitable that an American producer would seek to emulate this successful gimmick: Grease: You’re The One That I Want! appeared on NBC in 2007, with viewers deciding on the casting of the leads for a Broadway revival of the classic musical. Copycat programs included Legally Blonde: The Musical—The Search for Elle Woods (2008).

By the 1990s, costs had begun to escalate outside the reach of the individual investor. Broadway musicals are now generally financed by teams of producers and/or corporations (Disney, 20th Century Fox, Clear Channel Entertainment, Suntory International Corporation, Warner Bros. etc.). Disney made its Broadway debut with little fanfare as ‘The Walt Disney Studios’ was listed along with James B. Freydberg, Kenneth Feld, Jerry L. Cohen, Max Weitzenhoffer and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts as producers of Bill Irwin’s wordless masterpiece, Largely New York (1989). With their revitalised animated film musicals back in popularity, it was only natural that Disney began to look at its own catalogue of film musicals for possible stage transfers. The newly formed Disney Theatrical Productions made its Broadway debut in 1994 with Beauty and the Beast, which when it opened in London in 1997 was the most expensive West End show of its time (£10 million). With cross platform advertising (television, video, web, etc.) and extensive merchandising, Beauty and the Beast has enormous visibility. Two additional factors contributed to the Broadway production playing for thirteen years (5,461 performances): a reputation as ‘family entertainment’ and occasional star casting. As of 2015, the production had played to more than 35 million people in 30 countries.

In short order, Disney decided not only to continue to produce live musicals but also to become a theatre owner as well. After a $36 million renovation, Disney reopened the New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street to become the home of the next Disney blockbuster: The Lion King. In 1998, Disney began work on an original musical instead of adapting another one of its existing film musicals for the stage. Elaborate Lives was not well received in Atlanta, so Disney put the show back into rehearsal before a redesigned, rewritten, recast and retitled Aida opened on Broadway. Also penned by Lion King’s Elton John, Aida was another artistic triumph (four Tony Awards) and box-office success (1,852 performances). In 2004, Disney teamed up with British producer Cameron Mackintosh to bring Mary Poppins to the stage. Based on the stories of P. L. Travers and Disney’s own 1964 film version, this was another victory. While the stage musical version of Tarzan (2006, score by Phil Collins) was not well received critically, it appears to have found an audience in Europe with a revised libretto. The Little Mermaid (2008) was another box-office disappointment for the Mouse, but Newsies (2012) and Aladdin (2014) demonstrated that the Disney magic was back in full force.

With the disappearance of the individual producer came the increased importance of transfers arriving to Broadway not only from London but also from American regional theatres. Joseph Papp’s Public Theatre has been importing productions to Broadway since Hair (1967) and A Chorus Line (1975); other musical transfers to Broadway include Two Gentlemen of Verona (1971), The Pirates of Penzance (1980 revival), The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1985), Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk (1996) and Fun Home (2015).

Other non-profit theatres no doubt dream of replicating the success of A Chorus Line, which ran 6,137 performances in its original Broadway run, ultimately grossing $280 million worldwide. While Lincoln Center produces many musicals in its own theatres, it also has produced shows in traditional Broadway houses, such as Passion (1994) and Sarafina! (1987). Established in 1963, the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut, has exported twenty productions to Broadway, including Man of La Mancha (1965), Shenandoah (1975), Annie (1977), Swinging on a Star (1995), By Jeeves (2001) and All Shook Up (2005). Two major theatres in California have also been successful in New York: La Jolla Playhouse with Big River (1985), Thoroughly Modern Millie (2002), Jersey Boys (2005), Memphis (2009) and others, and the Old Globe Theatre with Into the Woods (1987), Damn Yankees (1994 revival), The Full Monty (2000), Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (2005) and A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (2013).

Musicals also arrive via organisations whose goals are to provide affordable New York visibility for new work; among these, the New York Musical Theatre Festival (NYMT), the New York International Fringe Festival (NYF) and the National Alliance for Musical Theatre (NAMT) are increasingly important development conduits. Established in 1999, NYF produced Urinetown (1999, NYF Festival; 2001, Broadway), Debbie Does Dallas (2001, NYF Festival; 2001, off-Broadway) and How to Save the World and Find True Love in 90 Minutes (2004, NYF Festival; 2006, off-Broadway). For three weeks every September, the NYMT has been presenting approximately thirty productions each season. Twenty-four productions have moved to commercial runs off-Broadway, which include Altar Boyz (2005), The Great American Trailer Park Musical (2005) and Gutenberg! The Musical! (2006); three NYMT musicals have opened on Broadway: Chaplin (2012), Next to Normal (2009) and [title of show] (2008). Each year eight musicals are chosen for the National Alliance for Musical Theatre’s (NAMT) annual New York conference, and are presented as forty-five-minute readings for commercial, regional and independent producers scattered around the country. NAMT notes that 85 per cent of the festival productions have received subsequent productions, including The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin (2000), Thoroughly Modern Millie (2000), Songs for a New World (2000), The Drowsy Chaperone (2006) and I Love You Because (2006).

The Business of Broadway

While the newest technological innovations seem to make their way into the set, light, projections, sound and costume designs of theatrical productions, modernisation of the business of the theatre often seems to come in fits and starts. Some theatres experimented with phone reservations and credit cards in the 1960s, but it was not until 1971 that all Broadway ticket offices began to accept American Express. By the 1980s, ticket sales were handled by centralised ticket sellers (Telecharge, Ticketmaster, Tickets.com) that allow patrons to buy tickets 24/7. Computerised ticketing meant that shows could sell further in advance than was possible with hard tickets, and by the early 1990s, patrons were able to choose their seats when ordering. The TKTS Booth opened for business in Times Square in 1973, run by the Theatre Development Fund. By selling half-price tickets the day of performance, many struggling shows were able to put paying customers in their seats, and folks of more modest means were able to attend a Broadway show. A different kind of selling tool came into being in 2001 when The Producers conceived the idea of premium-price ticketing in order to counteract the practice of ticket brokers buying the best seats in the house and reselling them at an enormous mark-up, a profit that did not benefit the original producers of the musical. Pricing the premium tickets at $480 meant that few seats went to resellers and that the profit from the mark-up went to the producers. While no one begrudges producers from turning a profit with their productions, this pricing scheme has not been met with universal support. According to one producer, ‘The number of premium seats for the special-event shows are spiraling out of control. We’re setting up a system that says, “Hey, if you’re not rich, don’t even bother coming to our show.”’19

Just as the manner of selling of tickets changed radically at the end of the twentieth century, so did advertising. Recognising that the primary strength of Pippin (1972) was Bob Fosse’s choreography, producer Stuart Ostrow created the first television commercial to feature clips of an actual Broadway production. Running 1,944 performances, Pippin owed a great deal of its longevity to this commercial. While show websites were relatively modest in the 1990s, by the twenty-first century they were often elaborate affairs, selling not only tickets, but merchandise as well. Boublil and Schönberg’s The Pirate Queen added ‘castcom’ to its website when the production was in previews in Chicago in 2006. Every day one or two video blogs were posted featuring interviews with cast and crew, members of the creative team, and audience testimonials. Web viewers were invited to post comments to each entry. While most blogs and threaded discussions on musical theatre tend to focus on the negative and their pessimistic tone can be seen as damaging word of mouth, the producers of The Pirate Queen sought to control at least part of the web dialogue about their production.

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Really Useful Group and Disney are thus far the only producing entities which group their current productions in advertising in order to build awareness in theatregoers that there is a branding that is larger than the individual production. Otherwise, advertising for Broadway shows is done on an individual basis. Realising the strong economic impact of live theatre in New York City, the New York State Department of Commerce launched the ‘I Love New York’ commercials in 1978. Promoting Broadway as a must-see tourist attraction, these commercials not only increased audience attendance but are also credited with assisting the economic recovery of New York City in the 1980s. Even though the professional organisation of the League of American Theatre Owners and Producers was established in 1930, it was not until the end of the twentieth century that its mission was broadened to include promoting not specific shows, but Broadway in general. In 1997 it unveiled the ‘Live Broadway’ logo and advertising campaign, which is meant ‘to designate genuine Broadway theatre, the highest quality form of popular entertainment’.20 While some are leery of any advertising scheme that attempts to promote the Ur-Broadway musical, others see a benefit to Broadway and New York to position live, professional theatre on Broadway as a unique experience.

Ultimately it does not matter whether the musical is produced by an individual or a corporation, whether it boasts an original plot or is a film-to-stage transfer, whether the seats are $20 off-off-Broadway or cost $480 for the Premium Broadway experience; whether the show has been in development for years or opens ‘cold’ on Broadway, there is no predicting unqualified success. If focus groups, talkbacks, threaded discussions and questionnaires were 100 per cent effective, then there would be no flops on Broadway. Yet the statistics yield a sobering fact: musical theatre remains a high-risk medium where less than one show in five breaks even. But when a show is financially successful, the economic possibilities can be staggering.

In the twenty-first century, artists continue to stretch and question many of the assumptions and conventions that have guided musical theatre throughout the previous century. The Drowsy Chaperone’s ‘Man in the Chair’ explains to us the virtues of the silly (and fictional) 1928 musical we have been watching: ‘It does what a musical is supposed to do. It takes you to another world, and it gives you a little tune to carry in your head when you’re feeling blue.’21 Of course, not all musical theatre authors approach the genre with this goal. Nevertheless, whether they are writing a traditional book musical, a concept musical, a jukebox musical, a sung-through musical, a rock opera, a dansical, a film-to-stage musical and so on, all of these creators would probably agree with the director Julian Marsh when he declares his core values in 42nd Street: ‘Musical comedy: the most glorious words in the English language.’ While Mr. Marsh would not recognise much of the innovation in the twenty-first century, he would no doubt approve of the talent and passion that drive musical theatre artists who keep the art form alive, relevant and revelatory.