1 Introduction

From investment banking to trading and portfolio management, virtually all financial market activity is in one way or another related to assets. However, assets have until recently remained a “blind spot” in political economy scholarship and social studies of finance (Langley, Reference Langley2020). Although this is rapidly changing as assets, assetization, and asset management are attracting considerable, cross-disciplinary research interest (Adkins, Cooper, and Konings, Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2020; Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020; Braun, Reference Braun2020), assets have not yet seen much attention from scholars of financial infrastructures. One reason for this may be the fact that assets are highly heterogeneous objects that have sparked a yet-to-be-resolved scholarly debate over their definition (Birch and Ward, Reference Birch and Ward2022; Chiapello, Reference Chiapello2023). This makes studying the link between assets and infrastructures more challenging compared to rather clearly demarcated sites such as trading desks or stock exchanges. And yet, assets are of particular importance for scholars of financial infrastructures because, as I argue in this chapter, they mediate between financial activity and infrastructures and have some infrastructural properties themselves.

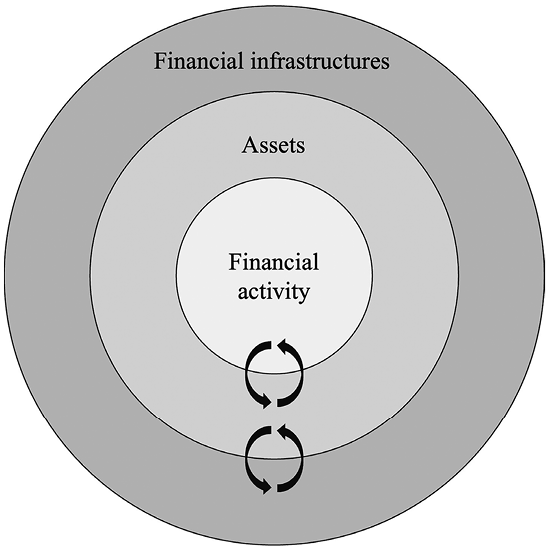

The main argument in this chapter is that assets are boundary objects between financial actors and financial infrastructures. Boundary objects inhabit various social worlds in which they have different meanings but nevertheless have a structure that is common enough to facilitate interaction between various groups (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989). Assets are boundary objects in the sense that they enable interactions – and structure social relations – between a myriad of actors, ranging from smallholder farmers in the Global South to financial traders in New York. Transformed into assets, all kinds of things – from farmland to industrial firms and public goods – become actionable by financial markets, and financial infrastructures play an important role in this process. At the same time, financial activity geared at particular assets can also affect the development of financial infrastructures. These interconnections are schematized in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Assets as boundary objects between financial infrastructures and financial activity.

The second argument made in this chapter is that the mediating role of assets differs along their lifecycle. Three different stages in the lifecycle of assets can be distinguished. Assetization is the first one and denotes the sociolegal transformation that restructures social relations in such a way that things become assets (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020; Tellmann, Reference Tellmann2022). The goal of assetization processes is to dissect cash flows from the objects that generate them and/or to attract financial capital. Assetization has important infrastructural characteristics for the operation of financial markets (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, p. 777): It facilitates the trade of these objects – as assets – on financial markets. When qualified according to particular asset classes, it standardizes core features and makes them durable. Assetization shows centrality, as assets structure much financial activity, and obscurity, as it produces a taken-for-granted reality – the asset form and the expected returns that come with it – that hides other aspects such as the struggles over return extraction (Golka, Reference Golka2023). Once traded on financial markets, assets undergo a translation into their second stage in the lifecycle: asset management. Here, two other practices, accompanied by different actors and infrastructures, take the stage: the management of and activities related to volatile asset prices, as well as the creation of new assets from assets (Leyshon and Thrift, Reference Leyshon and Thrift2007). The final step in the lifecycle of assets is their planned, forced, or accidental breakdown: deassetization. As deassetization often frees up the financial resources previously bound in the asset form, it is of constitutive importance for financial markets. However, as the case of “stranded” carbon assets shows, forced deassetization lays bare the power relations that constitute the asset form. Surprisingly, deassetization has received relatively little scholarly attention, which is why this chapter describes how an “infrastructural gaze” would guide and inform future scholarship (Westermeier, Campbell-Verduyn, and Brandl, this volume).

In Section 2, I briefly discuss the recent scholarly debate over the definition of assets and show how it can be resolved by understanding assets as boundary objects. The next three sections discuss the role of assets as boundary objects in between various forms of financial activity and financial infrastructures. Each section follows the travel of assets along three key stages of their lifecycle: assetization, asset management, and deassetization. This chapter ends with a conclusion.

2 What Is An Asset?

According to Merriam-Webster, the term asset derives from the French word assez (sufficient) and has historically meant “sufficient estate.” One important function of assets is thus to act as a collateral to cover corresponding liabilities. This can be seen in corporate balance sheets, where assets are usually ordered by their liquidity, ranging from cash and marketable securities to illiquid assets such as inventory. But assets are more than just collateral. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) understands assets as rights to economic benefit (FASB, 2021, E16–36). These may derive from property ownership but there are also other legal and contractual instruments that grant such rights (Pistor, Reference Pistor2019). While scholarship agrees that assets are relational, sociolegal constructs, there is less unity as to whether or not assets are necessarily return-bearing (Birch and Ward, Reference Birch and Ward2022; Chiapello, Reference Chiapello2023). This is an important question because return-bearing assets rest on a particular relational structure that enables the extraction of financial returns (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020; Tellmann, Reference Tellmann2022), whereas other assets such as currency – despite also being sociolegal constructs that grant rights to economic benefits, such as their exchange value – show entirely different relational configurations.

To circumvent these ontological questions, this chapter proposes to understand assets as boundary objects (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989). Originating in science and technology studies, boundary objects are objects, such as repositories, that facilitate interaction between social groups because their “interpretive flexibility” allows the maintenance of plural meanings that get stabilized in use without requiring consensus across groups (Star, Reference Star2010). Assets are boundary objects as they cater for the plural meanings that arise from the heterogeneous “information needs” of various social worlds (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989): Accountants may see assets on corporate balance sheets as “resources available for business operation” whereas portfolio managers may view them from their risk-return profile (Chiapello, Reference Chiapello2023, p. 1). However, these meanings need not be consensual, as exemplified by the case of cryptocurrencies that are labeled “crypto assets” by their proponents and Ponzi schemes by their opponents.

As boundary objects, assets also enable interaction between these diverse groups. If we follow an asset as it travels from, say, the exploration of an oil field via the balance sheet of a fossil fuel company into the portfolio of an asset manager that is later sold off in response to a divestment campaign, we see that assets travel along complex “chains of translation” (Latour, Reference Latour1999), understood as structured situations in which different actors act with and upon assets in different ways. In the following sections, I will discuss three of such situations – assetization, asset management, and deassetization – in more detail. In each of these situations, assets serve as important mediators between various actors and financial infrastructures and even carry several important characteristics of infrastructures themselves. Importantly, the infrastructures that enable the creation and trade of assets along their lifecycle are financial in the sense that they are related to the financial dimension of assets – whether or not they are related to financial markets. Investigating the lifecycle of assets thus helps in understanding financial infrastructures even where they precede financial market exchange.

3 Assetization

The transformation of all sorts of things into assets is called assetization and is the first step in the asset lifecycle (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020). Redirecting scholarly attention to the social process of creating assets, assetization scholarship has studied a remarkable breadth of objects, including data (Geiger and Gross, Reference Geiger and Gross2021), plant seedlings (V. Braun, Reference Braun2021), farmland (Ouma, Reference Ouma2020), or real estate (Fields, Reference Fields2018). Assetization, then, is a relational transformation by which these objects are detached from their initial context or claimants and “rebundled” into an asset (Tellmann, Reference Tellmann2022). This process of “narrative transformation” brings together various professions such as accountants, investors, business developers, or certifiers (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020).

Scholars of assetization have thus far focused on the creation of return-bearing assets.1 Here, the creation of durable economic rents is the key goal of assetization processes, which entails that many of these assets are made to keep rather than to be sold on financial markets (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020; Birch and Ward, Reference Birch and Ward2022). The asset form, then, can be understood as a boundary object in the contested social process called capitalization that entrenches the valuation of objects from the perspective of financial investors (Muniesa et al., Reference Muniesa, Doganova, Ortiz, Pina-Stranger, Paterson, Bourgoin and Yon2017). While various social groups interact in the valuation of objects, the asset form helps investors to “colonize” the valuation process by centering valuation on expected future cash flows (Chiapello, Reference Chiapello2015). Aiding in this process are financial valuation tools (such as business plans), through which expected future cash flows are constructed and discounted to the present moment (Doganova, Reference Doganova, Beckert and Bronk2018). In many cases, the valuation of “intangible” asset components such as property rights or market share plays an important role as their ascribed value often exceeds that of the tangible asset components such as buildings or machinery (Birch, Reference Birch2017; Bryan, Rafferty, and Wigan, Reference Bryan, Rafferty and Wigan2017; Chiapello and Engels, Reference Chiapello and Engels2021).

Strengthening the perspective of investors and enabling the extraction of rents, assetization is a fundamentally political process. The politics of assetization surfaces not only in struggles over various questions of valuation (Williams, Reference Williams, Birch and Muniesa2020), but also in resistances – even nonhuman ones – to the creation of relations of control (Ouma, Reference Ouma2020; V. Braun, Reference Braun2021). To overcome such resistances, proponents of assetization often call for the help of governments (Gabor, Reference Gabor2021; Golka, Reference Golka2023). A case in point is the assetization of public goods whereby private investors gain ownership of and control over previously public infrastructures (such as water or transport networks) and use their power to “sweat” these assets by extracting monopoly rents and underinvesting in maintenance (Allen and Pryke, Reference Allen and Pryke2013; Langley, Reference Langley2020; Christophers, Reference Christophers2023b). Governments also play a vital role by creating the wider sociolegal infrastructures that enable assetization in the first place and protect the extraction of rents (Pistor, Reference Pistor2019). Governments are furthermore turning to assetization as a form of developmental or industrial policy, subsidizing (“derisking”) private investments instead of financing projects directly (Gabor, Reference Gabor2021). This entails that assetization requires supportive political coalitions: As the attempt to create a market for so-called social impact investments in the UK has shown, assetization needs to be perceived as a credible and salient policy option and may quickly unravel with a change of political contexts (Golka, Reference Golka2023).

Assetization is an important case for scholars of financial infrastructures for two reasons. First, there are manifold, often bidirectional linkages between assetization and financial infrastructures that have thus far only rarely been made explicit. Informing pricing, risk assessment, and payment, financial infrastructures affect virtually all aspects of assetization (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019). A case in point is the role of digital infrastructures in creating assets such as cryptocurrencies that attract speculative capital even without granting access to future cash flows (Campbell-Verduyn, 2017), or that transform monetary flows into traceable digital stocks (Westermeier, Reference Westermeier2023). Other examples include financial infrastructures surrounding credit ratings or remittances that mediate processes of abstraction necessary for rent extraction (Kunz, Reference Kunz2011; Bernards, Reference Bernards2019). Complex information infrastructures, or “infostructures” (Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter, Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019), play a vital role in qualifying less tangible things such as windy sites (Nadaï and Cointe, Reference Nadaï, Cointe, Birch and Muniesa2020) or carbon credits (Langley et al., Reference Langley, Bridge, Bulkeley and van Veelen2021) into assets. Another important case is that of the digital infrastructures developed by real estate firms that gather data and automate key functions of the management of geographically dispersed property portfolios, such as rent collection and maintenance (Fields, Reference Fields2018, Reference Fields2022). These infrastructures are crucial enablers of assetization processes because they perform essential scale work that turns lower-tier real estate into an attractive investment opportunity. But the reverse may also be true as financial infrastructures can themselves be assetized. For example, Petry (Reference Petry2021) has studied how marketization, internationalization, and digitalization have turned exchanges into providers of infrastructures such as market data or indices. But this leaves open the question whether and how these infrastructures have themselves been turned into return-bearing assets by global exchange groups, and how this process of assetization has affected their operation and development.

Second, an “infrastructural gaze” could also help understand how and under what conditions assetization is bound up with infrastructural characteristics that enable and shape financial market activity, and what role financial infrastructures play in enabling these characteristics in the first place (Westermeier, Campbell-Verduyn, and Brandl, this volume). One important aspect here is that assetization allows separating ownership from control whereby even things that cannot be owned (such as consumers) can still be assetized (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020). Through sociolegal operations such as copyrights, assetization allows controlling things even after they are sold – which distinguishes assets from commodities where control relations end in the moment of exchange. Of even greater importance, however, is that assetization results in a “separation of rights from the thing involved” (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020, pp. 5–6), for example by separating the (legal and financial) corporation from the (material and operational) firm (Robé, Reference Robé2011). Shares, for example, grant rights to a corporation’s future cash flows rather than to, say, a piece of physical equipment. Viewed from an infrastructural perspective (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, p. 777), this separation not only facilitates the translation of real assets into financial products but also creates obscurity in the sense that the real and ongoing struggles over the extraction of financial returns become invisible to financial market actors. Likewise, the laws and regulations regarding assets, such as information requirements for stock market listings, or ratings and quality conventions, form part of the infrastructural work that enables financial activity through standardization and compartmentalization (Chiapello and Godefroy, Reference Chiapello and Godefroy2017). However, more research is needed to understand how assetization performs such infrastructural characteristics and what role(s) financial infrastructures play in this process. Viewing assets as boundary objects can provide a useful lens in these research endeavors, not least because it also allows making the connection to financial market exchange, to which this chapter turns to next.

4 Asset Management

The translation of assets into the second stage of their lifecycle is marked by their sale on financial markets. Importantly, not all assets will undergo this translation, or won’t do so immediately, as assets are often made to keep (Birch and Muniesa, Reference Birch and Muniesa2020). If they do, however, assets become financial assets, and are marked by two crucial operations during which the actors and infrastructures related to them change significantly. The first operation is the exchange or trading of assets, which introduces a more or less volatile market price. This means that assets also become commodities that can be speculated with (i.e., asset commodities). The trading of these asset commodities does not necessarily affect the asset form, even though asset prices may feed back into the sociomaterial structure that underpins the respective asset (such as the corporation whose shares are speculated with). Scholars of financial infrastructures have paid considerable attention to the ways in which infrastructures enable, shape, and transform the various sites and practices of asset trading. The second operation, however, has thus far received less systematic attention from an infrastructural perspective. This operation is what I call layering, that is, the production of new assets from assets (Golka, Reference Golka2021). After a short overview of research on trading and infrastructures, this section will turn to layering.

The manifold interconnections between asset trading and financial infrastructures have received considerable scholarly attention, particularly in the social studies of finance (see chapters by Handel, Muellerleile, Petry, as well as Tong and Preda, in this volume). The introduction and historical transformation of stock exchanges are a paradigmatic case, showcasing the bidirectional connections between financial activity and infrastructures. For example, the introduction of the stock ticker had a profound effect on the operation of financial markets through standardization and the creation of shared temporal structures (Preda, Reference Preda2006). More recently, Pardo-Guerra (Reference Pardo-Guerra2019) has shown how the infrastructure of automated stock exchanges has informed the division of professional roles and practices in financial markets. Another example is the development of high-frequency trading, which is, regarding physical proximity or trading algorithms, often tailored to specific stock exchanges but also drives the development of underlying sociotechnical infrastructures (MacKenzie et al., Reference MacKenzie, Beunza, Millo and Pardo-Guerra2012; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2018). This is also an important insight for political economy scholarship as these infrastructural dependencies inform new inequalities and power relations (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019).

What does attention to the asset form add to such scholarship? This is an important question not least because many characteristics of today’s trading infrastructures can be traced to their role in facilitating commodity – rather than asset – trading (Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021). One important way to address this question is by understanding how, with the rise of asset management (B. Braun, Reference Braun2021), trading and layering are increasingly entangled, and how this entanglement transforms financial infrastructures. Tracing the development of financial exchanges, Petry (Reference Petry2021; see also this volume) has shown how they have increasingly broadened their scope from mere trading sites to what he calls “global providers of financial infrastructures.” However, these infrastructures, market data, indices, and financial products may not only become assets for the exchange groups themselves, but are indeed often geared at facilitating layering by asset management companies or the exchanges themselves. Enabling new forms of layering may thus have become a key factor driving the development of financial infrastructures.

So what exactly, then, is asset layering? By asset layering, I mean the construction of new financial assets from existing financial assets. Two of the most important forms of layering are the construction of portfolios as well as the issuance of derivatives. The fact that the same asset (e.g., a listed share) can undergo both of these layering processes at once points again to the importance and utility of understanding assets as boundary objects. Layering is an important part of financial market activity because it can absorb significant volumes of capital, generate fees for financial intermediaries, and cater for the needs of institutional investors. The rise of the “Big 3” asset managers (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) exemplifies one important approach to layering as these actors construct large-scale, index-tracking, fully diversified portfolios (Braun, Reference Braun2016; Fichtner, Heemskerk, and Garcia-Bernardo, Reference Fichtner, Heemskerk and Garcia-Bernardo2017; Petry, Fichtner, and Heemskerk, Reference Petry, Fichtner and Heemskerk2021). This new, “passive” approach to asset layering has significantly altered global flows of capital and is poised to overtake the traditional layering approach of curated, actively managed portfolios within the next few years (Bloomberg, 2021). It has been enabled by the development of financial infrastructures surrounding exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that allowed tracking indices even for frequent financial transactions (Braun, Reference Braun2016), and has since led to a fundamental transformation of power relations within the financial sector by giving index providers and large asset managers considerable infrastructural power (B. Braun, Reference Braun2021; Petry, Fichtner, and Heemskerk, Reference Petry, Fichtner and Heemskerk2021).

Asset layering also shapes how the financial sector affects the economic governance of the respective portfolio firms and thus translates changes in the realm of financial infrastructures back into the real economy. Passive investing combines full diversification, that is, the inability to “exit,” with performance-independent fees that give little incentives to “voice” (Fichtner, Heemskerk, and Garcia-Bernardo, Reference Fichtner, Heemskerk and Garcia-Bernardo2017; Braun, Reference Braun2022). As indices often weigh firms on market capitalization, passive investing may fuel superstar stocks such as Big Tech or fossil fuel shares that become an important source of asset manager profits (Petry, Fichtner, and Heemskerk, Reference Petry, Fichtner and Heemskerk2021; Baines and Hager, Reference Baines and Hager2023). This means that demand from passive investors affects firms’ share prices more than their dividend payments – that is, the expected cash flows that constitute the asset form. New forms of asset layering may therefore, seemingly paradoxically, shield superstar firms from assetization pressures regarding the extraction of returns. Indeed, this matches the observation that many Big Tech firms pay only little to no dividends (Klinge et al., Reference Klinge, Hendrikse, Fernandez and Adriaans2023). However, other approaches to asset layering may lead to different outcomes, as evidenced by private equity and venture capital funds. These funds invest in only a small number of firms, over which they gain considerable control, and earn fees based on their financial performance. These investors are known to exert significant pressure on their portfolio firms, using their position to “sweat” assets, force them to aggressively increase market share to drive up initial public offering (IPO) valuation, or burden them with considerable debt (Froud and Williams, Reference Froud and Williams2007; Robertson, Reference Robertson2009; Birch, Reference Birch2017).

The creation of derivatives is another vitally important strategy of asset layering. If measured by notational amount, derivatives have, with over $600 trillion, by far the largest volume of any financial product, and far exceed global US dollar supply. However, their gross market value is considerably lower. Moreover, the vast majority of derivatives is not based on return-bearing assets, such as equity or bonds, but on interest rates and foreign exchange (BIS, 2022). The development of foreign exchange and interest rate derivatives has been linked to the emergence of new financial infrastructures within governments (Lagna, Reference Lagna2016; Schwan, Trampusch, and Fastenrath, Reference Schwan, Trampusch and Fastenrath2021). Historically, derivatives have emerged as an insurance on markets for agricultural commodities (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile2015), whereas asset derivatives such as stock options have long been seen as (illegitimate) gambling. This only changed with the development of the Black–Scholes formula for option pricing in the mid-1970s, which played an important role in legitimating option trading and structured option pricing and the development of respective financial infrastructures (MacKenzie and Millo, Reference MacKenzie and Millo2003; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2008). The introduction of the Black–Scholes formula also changed option trading as it allowed pricing the volatility of stocks, thus creating a market for risk (Millo and MacKenzie, Reference Millo and MacKenzie2007). Stock options are an important case for the power of financial infrastructures as exchanges and clearing houses such as the Options Clearing Corporation shape virtually all aspects of issuance, trade, and post-trade on option markets (Genito, Reference Genito2019). However, as Petry (Reference Petry2021) notes, their role beyond the provision of marketplaces has received only little scholarly attention (but see Genito and Lagna, this volume). Hedge funds are the most important actors in derivatives trading, using the latter to increase their market exposure (Holmes, Reference Holmes2009). Hedge funds also create important connections between financial trading centers in the USA and offshore destinations such as the Cayman Islands (Fichtner, Reference Fichtner2016). This may partially explain the secrecy and the significant research gap surrounding hedge funds and thus the use of derivatives more generally. As recent market data suggest, equity options are increasingly losing market share relative to ETF and index options that have seen double-digit growth rates (OCC, 2023). This poses the question of how transformations in one area of asset layering may inform changes in another, and how these dynamics are enabled or mediated by financial infrastructures.

While scholarship has begun to understand the bidirectional relationships between financial infrastructures and asset layering (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2008; Braun, Reference Braun2016), more research is needed to address at least four other sets of questions. The first one is how changes in the link between financial infrastructures and asset management can become self-reinforcing. This may include transformations in the epistemic realm whereby growing dependencies on financial markets strengthen financial experts and crowd out other forms of expertise (Golka and van der Zwan, Reference Golka and van der Zwan2022). This points to the second question: unintended consequences resulting from changes in the link between asset layering and financial infrastructures. This is exemplified by the “clearing mandate” introduced to derivatives settling that, contrary to policymakers’ intents, strengthened private authority and created new financial stability risks (Genito, Reference Genito2019). A third set of questions is whether and how constrained access to infrastructures may spark reactivity. An example is special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) – listed vehicles that acquire private companies that then become publicly traded. SPACs remunerate their sponsors with total fees beyond 20–25%, which are called “ridiculous” even within the financial industry (Citywire, 2021). As SPACs are designed specifically to circumvent formal IPO requirements, it is access to otherwise inaccessible financial infrastructures that may make them attractive to some actors despite their hefty fees. A fourth set of questions revolves around how asset layering interacts with infrastructural developments across domains. For example, as described, the development of digital infrastructures was a key enabler for the assetization of housing (Fields, Reference Fields2018, Reference Fields2022). This development coincided with the rise of real estate investment trusts (REITs), relatively diversified commercial or residential real estate portfolios listed on stock exchanges. REITs have gained prominence following the collapse of mortgage-backed securities markets during the 2008 financial crisis and play an increasingly important role in funneling institutional capital to real estate (Waldron, Reference Waldron2018; Fuller, Reference Fuller2021). While REITs have been found to create opportunities and incentives for asset managers to increase rent extraction from real estate (Yrigoy, Reference Yrigoy2021), less is known about the interaction between these various infrastructural developments. More research that explores the manifold linkages between financial infrastructures, asset layering, and financial actors is therefore needed.

5 Deassetization

The third and final stage in the asset lifecycle is deassetization, that is, the dissolution of the asset form or one of its layers. For the majority of financial assets, deassetization is a planned feature: Stock options cease to exist once the option right is used, as do bonds and loans once they are fully repaid. Layered assets such as fixed-term funds that are common in private equity and venture capital are unbundled after a predefined duration, releasing cash to investors and performance fees to asset managers, while the portfolio items themselves continue to exist as assets with different owners (Cooiman, Reference Cooiman2023). Writing off assets that cannot be sold – such as Russian holdings following the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Phillips, Reference Phillips2022) – may also be seen as a particular form of deassetization. As deassetization has, to date, received only little scholarly attention, its interconnections with financial infrastructures remain rather unclear. This raises questions regarding how infrastructural actors such as clearing houses inform the terms and processes of deassetization, and what consequences this has for financial activity more generally. Another fruitful avenue could be to explore further the role of (planned) deassetization for the infrastructural characteristics resulting from assetization processes. For example, Brett Christophers argued in a recent Financial Times op-ed (2023a) that private investors investing in public infrastructures (such as roads) have incentives to underinvest into maintenance and improvement as they will not reap potential profits from such investments due to the lifespan of the fund. An infrastructural gaze on assets and their planned deassetization could thus help address recent calls for a sociology that understands societal futures as shaped by the temporal logics of assets (Adkins, Bryant, and Konings, Reference Adkins, Bryant and Konings2023).

When unplanned, however, deassetization makes visible the inequalities and power relations that are often obscured by the asset form. A case in point here is “stranded” assets, that is, financial assets that are expected to face significant devaluation (Caldecott, Reference Caldecott2017). In the context of an escalating climate crisis, fossil fuel assets are increasingly seen as stranded as many carbon reservoirs must not be burned in order to achieve the Paris climate goals. Here, an infrastructural gaze could help unpack how, much like infrastructures that become visible upon collapse (Star and Ruhleder, Reference Star, Ruhleder, Bowker, Timmermans, Clarke and Balka2015 [1996]), the threat of deassetization lays bare the ways in which inequalities and relations of expropriation have been made durable and obscured in a layered asset economy (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019; de Goede, Reference de Goede2020). Not surprisingly, owners of carbon assets leverage their legal affordances to address the threat of devaluation (Caldecott et al., Reference Caldecott, Clark, Koskelo, Mulholland and Hickey2021), or use their power resources to mobilize significant compensation from governments (Furnaro, Reference Furnaro2023). However, an infrastructural perspective would go even further and investigate how infrastructural dependencies – and thus investors’ ability to leverage infrastructural power – shape the struggles over carbon deassetization. An infrastructural perspective could also investigate how looming threats of deassetization are translated into risks, and how these and wider climate risks are managed by financial actors, informed by and informing new financial infrastructures (Taylor, Reference Taylor2023). As many carbon assets and sinks are located in the Global South but owned in the Global North (Semieniuk et al., Reference Semieniuk, Holden, Mercure, Salas, Pollitt, Jobson and Viñuales2022), an infrastructural perspective may also help understand the colonial aspects of such deassetization struggles as it allows bridging between the micro-level of individual carbon assets and the macro-level of global finance (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019; de Goede, Reference de Goede2020).

6 Conclusion

In this chapter, I made the case for assets as important research objects for scholars of financial infrastructures. My argument was that assets are boundary objects that enable interaction across social groups and, depending on the stage in their lifecycle, serve as important hinges between financial infrastructures and various forms of financial activity. Being the focal point of much of global financial activity, assets – and the various approaches to asset layering – play an important role in the development of new financial infrastructures. However, at the same time, assets are critically shaped by financial infrastructures and carry important infrastructural characteristics that enable financial activity in the first place. To unpack these bidirectional interlinkages, this chapter has focused on three key stages in the lifecycle of assets – assetization, asset management, and deassetization – that differ in these interlinkages.

This chapter thus contributes to making renewed research interest in assets and assetization accessible to scholars of financial infrastructures, and to pointing out the importance of financial infrastructures to scholars of assetization. Tracing assets along their various steps of translation, this chapter also takes seriously the reminder from Leyshon and Thrift (Reference Leyshon and Thrift2007, p. 109) that financial capitalism is “not all smoke and mirrors” and that “there has to be something there to begin with” – that is, assets. However, taking the asset form – and its manifold interrelations with financial actors and infrastructures – seriously matters not only for scholars of finance. Sociologists and political economists have shown the fundamental importance of assets in structuring new class boundaries (Adkins, Cooper, and Konings, Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2020) and global wealth inequalities (Pfeffer and Waitkus, Reference Pfeffer and Waitkus2021). Bridging the inside and outside of financial markets, the micro and the macro, and unpacking the making and transformation of power relations (Westermeier, Campbell-Verduyn, and Brandl, this volume), a shared perspective of assets and infrastructures could help uncover important mechanisms for the entrenchment and perpetuation of such asset-related inequalities.