1 Introduction

Over a decade ago, cultural anthropologist and sociolegal scholar Bill Maurer called for attention to “the act and infrastructure of value transfer” – that is, to payment, a domain long neglected in social studies of finance (2012a, p. 19). Payment, he argued, was important to understand both because it was a key cultural, economic, and technological form and because its cultures, economies, and technologies were rapidly changing. In other words, it served the infrastructural functions of money.

In the first decades of the 2000s in the United States, payment infrastructures are rapidly becoming more powerful. As scholars such as O’Dwyer (Reference O’Dwyer2023) and Westermeier (Reference Westermeier2020) demonstrate, finances are increasingly becoming platformized, with large, data-driven companies working to embed payments within their platforms and seeking to profit from access to users’ transactional data.

Understanding payment as an act and infrastructure underscores that money is a communication medium, a way of transmitting information that produces shared meaning (Swartz, Reference Swartz2020). Payment technologies – cash, cards, checks, or apps – do not simply transmit value. They communicate the nature of the relationship between two parties and reveal information about how we see ourselves and how we are viewed by powerful institutions (Zelizer, Reference Zelizer1997). As a communication infrastructure, payment binds us together in a transactional community, a shared economic world, and this shores up new and existing inequalities.

Payment infrastructures are increasingly being understood as a form of “social media.” In the broader communication context, there is a sense that the era of mass media (characterized by unidirectional broadcast and print technologies) has given way to one of social media (digital media that is niche, participatory, peer-to-peer, globalized, and surveilled). So too, mass money media have shifted to social money media. If, as geographer Emily Gilbert suggests, state currency was designed to enact “mass” transactional communities at the scope of the nation-state, what kinds of transactional communities do new “social” payment systems entail?

Of course, there is no way to neatly segment the two; most critical scholars are uncomfortable even using the terms “mass media” and “social media” (see, e.g., Papacharissi, Reference Papacharissi2015) as though they describe discrete phases. Similarly, the shift from mass money media to social money media is more complicated than it sounds. The mass medium of cash has always been accompanied by other money tokens, including foreign currency, coupons, and checks (Carruthers and Babb, Reference Carruthers and Babb1996; Henkin, Reference Henkin1998).

Yet social media money is helpful shorthand for an industry, a way of describing a certain set of technologies and a series of norms and engagements. To be sure, money has always been social and money has always been media. As a media technology, payment infrastructure is currently being redesigned to look more like social media, largely by Silicon Valley.

But this redesign brings up new questions: Who gets to control payment? Communication technologies come with constraints that can exclude potential users from the transactional communities produced by those forms of payment. Despite being a state technology, cash is difficult to control or surveil and has a low barrier to entry. New money media, created in the image and footsteps of social media, will not be equally accessible. As we move from mass transactional communities to social transactional communities, what are the implications of this shift? Who will monitor, control, and restrict these new payment rails?

2 Transactional Memories: Social Payments and Data Economies

The media studies scholar Josh Lauer (Reference Lauer2017) demonstrates that the concept of “financial identities” is centuries old: credit bureaus of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries collected information and stories to determine borrowers’ ability to repay. These reports, Lauer says, made modern people into “legible economic actors” (p. 35).

But in recent years, there has been a shift from these aggregations of financial data to what I call transactional identities, shaped by how, where, when, and with whom we transact. If the former constituted identity via credit, the latter constitutes identity via payment infrastructure. We perform these transactional identities through payment, and they shape how others view us, whether as Amex Black card holders or electronic benefits welfare card users.

These transactional identities are being shaped in real time by social money media, as exemplified by Venmo, a peer-to-peer mobile payment app that is especially popular in the United States, where bank transfers are expensive and cumbersome. Venmo includes a social “feed” of transactions, visible to friends, similar to a Facebook news feed or Instagram post. The app requires users to annotate their transactions with notes and encourages them to use emojis: pizza, taxi, clinking wine glasses.

In this way, Venmo illustrates what sociologists Alya Guseva and Akos Rona-Tas (2017) call the “new sociability of money”: The ability of digital money technologies to “preserve the details of economic transactions, to capture our geographic movements, to infer our tastes and routines” (p. 204). The app also gives rise to new forms of social communication, including playful interactions and coded messages (Acker and Murthy, Reference Acker and Murthy2018). Its social streams reinforce, memorialize, and even potentially strain social relationships (Drenten, Reference Drenten, Belk and Llamas2022).

Venmo reveals that money has always been social, but it also encloses that sociality within its platform and records it for perpetuity (O’Dwyer, Reference O’Dwyer2019). Scholars across fields have argued that money is a technology of memory (see, e.g., Kocherlakota, Reference Kocherlakota1998). Social media is also a technology of memory; it is part of what the media scholar Jordan Frith has called “a new memory ecology” assembled on mobile phones (2015, pp. 90–91).

These transactional memories can also be used for surveillance and control. Nigel Dodd writes that “a device for remembering cannot be divorced from the criticism that it is also a vehicle for political and commercial surveillance, above all, as long as the technology involved is controlled by corporations and states” (2014, p. 296, original emphasis). Kelsi Barkway (Reference Barkway2023) documents how even seemingly benign technologies (in this case, benefits cards for distributing welfare payments) can be perceived as tools of surveillance and social control, inciting fears in users that their spending is being monitored and they will be judged as undeserving.

Digital transactions are, in fact, being used for control and punishment. Police in Atlanta have used access to an activist’s PayPal account to bring criminal charges against a bail fund that has supported protests against the construction of a large police training facility (Lennard, Reference Lennard2023). Consumers may not be aware that their transactional memories can be used to cause them trouble, as in the case of mobile-phone borrowers in Kenya, whose phones offer them access to credit while simultaneously generating a stream of financial and personal data that can harm their credit scores. Social scientists Kevin P. Donovan and Emma Park (Reference Donovan and Park2022a, 2022b) note that many of these borrowers end up seeking expensive short-term credit to prevent damage to their credit scores, ensnaring them in a cycle of debt that is difficult to exit, a form of “predatory inclusion.”

In fact, many of our experiments with digital payment technologies are being enacted on the world’s most vulnerable people. Aaron Martin (Reference Martin2019) documents how mobile money platforms facilitate both familiar and novel forms of surveillance of users by government entities and service providers. Similarly, anthropologist Margie Cheesman notes that companies and aid organizations providing support in refugee camps are testing out web3 technologies such as blockchain wallets to distribute various kinds of payments. In this environment, where users have limited choices, rights, and protection, forced use of these technologies requires them to generate financial data over which they have little control (Cheesman, Reference Cheesman2022a). Thus, she recommends that web3 technologies not be used experimentally among vulnerable populations (Cheesman, Reference Cheesman2022b).

3 Chokepoint Power: How Controlling Payment Infrastructure Controls Users’ Lives

The systems that allow us to get paid, like many other critical infrastructures, are largely invisible until they stop working (Star, Reference Star1999; Edwards, Reference Edwards, Misa, Brey and Feenberg2003). And when those systems stop working, it often comes as an account that is frozen without warning, perhaps for opaque reasons. Users may have little recourse, and the consequences of an account freeze can be severe.

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the US Department of Justice and the Financial Fraud Enforcement Task Force launched Operation Choke Point. The name of the project is notable: The task force had the power to constrain merchants’ ability to get paid, targeting fraudulent institutions by “choking them off from the very air they need to survive” (Zibell and Kendall, Reference Zibell and Kendall2013). To fully participate in a transactional community – to be a “citizen” of that community – you need unobstructed access to a system of payment, because a system that can suddenly cut you off is more dangerous than not having access at all.

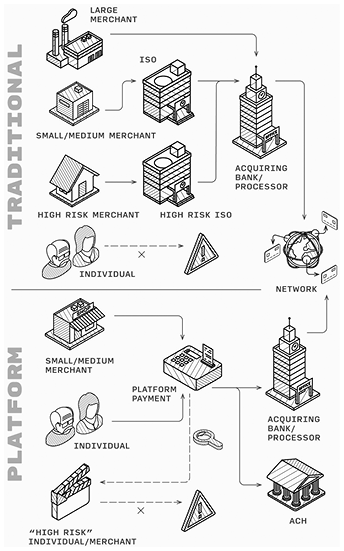

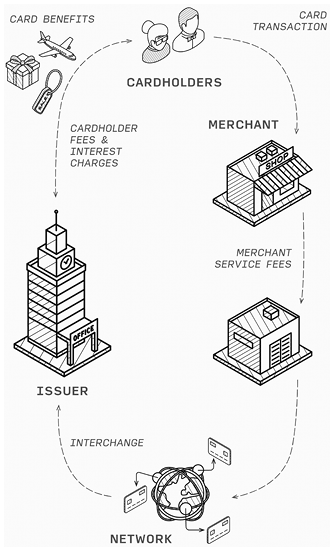

In recent decades, the business of getting paid has been changing in critical ways. In the United States, for example, payment acquisition systems are shifting from traditional independent sales organizations or ISOs (middlemen organizations that serve as payment service wholesalers), to tech startups looking to disrupt the payments system (see Figures 24.1 and 24.2). Payment cards were originally designed for an economy in which the line between buyers and sellers was clear; modern payments companies facilitate peer-to-peer payments in a geographically dispersed communication system.

Figure 24.1 Traditional and platform models of how payments are acquired.

Figure 24.2 The communication of a card payment.

In the 1990s, an emerging set of payment service providers (PSPs) overlaid new systems on existing infrastructure, bridging old and new technologies and policies (some more successfully than others). The first of these providers, and likely still the most successful, was PayPal, which created parity between users. Its primary innovation was to bypass the old payment acquisition system by keeping money in a closed loop on its platform for as long as possible. This has become the predominant model for PSPs coming out of the tech sector, such as WePay, Square, Venmo (now owned by PayPal), and most of the embedded social media payment systems, such as Facebook Messenger Payments.

However, in the midst of this shift, the way that payment providers manage risk has also changed, in ways that do not benefit – and indeed, can imperil – consumers. This is a shift in what sociologists call “riskwork” – how risk is imagined and managed – that can lead to payment shutoffs for vulnerable users. Managing payments means managing risk, and managing risk is inherently political.

In the traditional ISO model, issuers represent the interests of cardholders, while acquirers represent the interest of merchants and there is a marketplace for payments in high-risk industries. In contrast, within the new payments model, the PSP’s client is the platform, not the parties who are transacting. Risk is managed, not through a marketplace model, but a standard tech-industry mechanism: the terms of service (TOS) agreement, which users must agree to (but don’t usually read) when they sign up for an account, TOS agreements can change at any time. and there is no compelling interest for tech companies to find a way to manage risk when they can simply ban any transactions they deem “too risky.”

As is common in the realm of social media, these peer-to-peer payment systems use surveillance and automation to enforce TOS agreements and mitigate risk. Surveillance scholars have noted that the power of surveillance extends beyond watching to identifying, classifying, and assessing (Gandy, Reference Gandy1993; Lyon, Reference Lyon2002), making surveillance a form of “social sorting.” As Fourcade and Healy point out, the “classification situations” produced by the wrangling of “big data” are “presented, and experienced, as moral-ized systems of opportunities and just deserts.” They “have learned to ‘see’ in a new way and are teaching us to see ourselves that way, too” (2017, p. 10).

Although the tech industry could, theoretically, develop systems that profit from varied appetites for risk, like traditional ISOs, there has instead been a shift toward probabilistic modeling and monitoring, using machine learning to monitor users’ social media presence to flag “high-risk” transactions and ban them.

But this gives rise to a variety of mistakes, like bans on users who tag a Venmo purchase “Cuban” for a sandwich, or playfully use a bomb emoji. Predictive analytics systems are always experimental and designed to live in “perpetual beta,” in which products are “developed in the open, with new features slipstreamed in on a monthly, weekly, or even daily basis” (O’Reilly, 2005). This makes it even harder for users to predict what might earn them an account freeze.

To make things more confusing for users – and more perilous for users with fewer resources – TOS agreements tend to be unevenly enforced. As the internet researcher Tarleton Gillespie (Reference Gillespie2018) points out, platforms of all kinds routinely make seemingly arbitrary calls about what does and does not violate TOS. For banned users, often their only form of recourse is a byzantine and ineffective process, while, in the meantime, they have lost access to their stored funds, as well as to the transactional community of the platform.

This has been notably true for sex workers. As of 2018, the sex-worker activist Liara Roux has collected dozens of examples of discrimination against sex workers by financial services companies (Lake and Roux, Reference Lake and Roux2018; see also Blue, Reference Blue2015). Legislation and policies intended to reduce human trafficking also constrain sex workers, denying them access to the websites they use to work and make a living (Blunt and Wolf, Reference Blunt and Wolf2020).

We still haven’t created payment infrastructures that move at the pace of our modern world but maintain all of the key affordances of cash. Cash is anti-surveillant, self-clearing, immediate, and reliable (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2017; Scott, Reference Scott2022). But the most vulnerable are often forced to choose between payment channels that are unreliable or totally inappropriate for the digital nature of their work. We are still not getting payments right – not for everyone, and not all of the time.

4 Money (and Everything Else): Increasingly Private, Segregated, Siloed

In recent decades, the card-issuing business in the United States has become increasingly competitive and stratified, producing niche transactional identities. Although payment card products are mandated to look similar and use the same infrastructure, they are imbricated in different infrastructural, economic, and discursive assemblages (see Deville, Reference Deville, Gabrys, Hawkins and Michael2013; Gießmann, Reference Gießmann2018). Some cards pay users back; others charge usage fees. Some are more expensive than others for merchants to accept. The architecture of the modern card network is marked by hierarchy, difference, and communication.

Merchants agree to pay slightly more in interchange fees to receive payment from rewards cards and other luxury credit cards designed for the most “desirable” consumers than they do from standard cards. But because merchants then increase their costs to account for interchange, some consumer advocates argue that customers wind up paying for their own – or other people’s – rewards (see, e.g., Schuh, Shy, and Stavins, Reference Schuh, Shy and Stavins2010). As Maurer (Reference Maurer2012b) has pointed out, this system doesn’t exactly fit the picture of the capitalist economy; it is a rare situation where competition among issuers for the “best customers” drives prices up for everyone.

Universally accepted payment cards are relatively new (see Swartz and Stearns, Reference Swartz, Stearns, Nelms and Peterson2019; Swartz, Reference Swartz2020). The earliest precursor to credit cards, Charga-Plates, emerged in the 1930s. Resembling dog tags, these metal rectangles could be used by department stores to quickly imprint a customer’s account information on a payment slip.

By the 1950s, the Diners Club charge card had emerged as the first universal third-party payment card in the US, although it did not give customers access to credit, and in fact preceded the first credit card by at least fifteen years. The club functioned like a membership organization, offering a range of services beyond credit. Merchants paid a fee to be able to accept Diners Club card payments (a closed-loop system), but were assured by the organization that these members would likely spend. Indeed, having a Diners Club card was seen as a ticket to an elite group who had access to “country club style billing” or receiving a folio bill (Sutton, Reference Sutton1958). By the end of the 1960s, these elite customers were flocking to American Express, another closed-loop charge card. An AmEx card was initially difficult to get, and the company made a name for itself over the next several decades as a product for the elite, conferring privileges and status (Grossman, Reference Grossman1987).

In the late 1960s, beginning with Bank of America’s BankAmericard, banks began to issue payment cards linked to consumer credit accounts (Evans and Schmalensee, Reference Evans and Schmalensee2001). These credit cards, unlike Diners Club and American Express, were easy for bank customers to access; even with poor credit, most Americans could be approved for some kind of credit card (Nocera, Reference Nocera1994), which meant that paying by card was no longer reserved for elite customers. The BankAmericard network was eventually licensed to other banks and became the Visa Network, an open-loop system that acted as an intermediary among a variety of banks, merchants, and cardholders. As the historian of technology David L. Stearns (Reference Stearns2011) explains, opening the loop – making it possible to pay across banks, card types, and indeed transactional identity classes – was the key innovation of the bank card system.

When regulations against interstate banking loosened, beginning in 1978, banks in open-loop networks started to issue credit cards on a national level, competing for customers on a much wider geographical scale. By the early 2000s, the payment card market had become differentiated enough to create a wide range of stratified transactional identities – from “ultrapremium” cards for wealthy (or at least choosy) consumers, to small-business credit cards, debit cards, secured credit cards for those with poor credit, and prepaid cards for consumers who were unbanked or underbanked.

Just as payment methods have become increasingly stratified, so too have our visions of the future of money. A variety of scholars, activists, and entrepreneurs have described futures in which money is digital and issued by nongovernment entities (Maurer, Reference Maurer2005; Brunton, Reference Brunton2019). In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, many people were eager to try anything other than money as usual (Maurer, Reference Maurer2011).

One of these imagined futures is cryptocurrency. Beginning with Bitcoin, first theorized in 2008, these digital currencies intentionally create new transactional communities, rethinking the value, identity, space, time, and politics of money. Designed to be a kind of “digital gold,” Bitcoin took hold of the public imagination as a kind of “Magic Internet Money,” backed not by the government but by cryptographic scarcity, able to move at the speed of the Internet without the drawbacks of traditional payment systems like fees and surveillance (Maurer, Nelms, and Swartz, Reference Maurer, Nelms and Swartz2013; Swartz, Reference Swartz and Castells2017). Bitcoin has been joined by thousands of other cryptocurrencies, few of which have ever been accepted by vendors, but all of which are ways to reimagine nongovernment-issued money, which might outcompete and outlast state-issued currency (Swartz, Reference Swartz2018; Brunton, Reference Brunton2019).

The future of money might also look something like corporate currency, a reality that is already playing out in the forms of rewards programs and social media payments. Starbucks, for example, now issues something that hews very close to a private digital currency: Starbucks Rewards, a loyalty program in which members can earn “stars” for purchases and can load and reload funds on Starbucks gift cards for perks. As of 2023, the program had 30.4 million members and funds loaded on cards had reached US$3.3 billion (Starbucks, 2023).

Facebook has also dabbled in creating a corporate currency, first with the announcement in 2019 of Libra, envisioned as a universal, global digital currency: a one-world money. Rather than being niche and segmented, Libra was described as connecting users across currencies and payment systems. Unlike cryptocurrencies, Libra’s design involved large corporations managing its monetary policy and infrastructure. Although the project was eventually shut down, in 2019 Facebook also announced the launch of Facebook Pay (now Meta Pay), which integrated payments with the company’s suite of social media products.

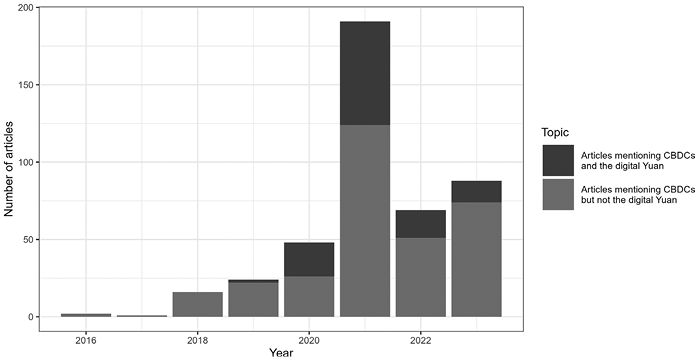

Some new forms of currency seek to be more universally accessible, but whether they will be able to achieve this is uncertain. Central bank digital currencies (CBDC) are currently being “explored” by many of the world’s central banks. While designs for these currencies vary widely, they are by definition a liability of the central bank, accessible to the public. However, since central banks do not have the digital infrastructure to provide financial services directly to consumers, these currencies must be intermediated, and the questions of by whom and how are crucial. If CBDC are to be truly accessible, rather than replicating existing systems that lock some consumers out, they must be very carefully designed (Narula, Swartz, and Frizzo-Barker, Reference Narula, Swartz and Frizzo-Barker2023; see also Swartz and Westermeier, Reference Swartz and Westermeier2023).

The future of payment infrastructures seems increasingly stratified. Customers who are members of loyalty programs or who carry “ultrapremium” cards often have access to a differentiated experience, with a separate customer service portal, lavish treatment, and even different physical spaces within a hotel or sports arena. The flipside is true for shoppers using state benefits cards, who can only buy certain foods at the grocery store. Technology and culture scholar Nathaniel Tkacz (Reference Tkacz2019) argues that payment apps compete on the basis of offering not just payment but, perhaps more importantly, “experience” of the world. He explains that such “experience money” takes up ordinary transactions and “deliberately infuse[s]” them “with a coherent value proposition” (p. 277).

As our money becomes more plural, so too do our transactional identities. We may find ourselves using multiple monies, bouncing between different payment infrastructures, and thus oscillating in and out of a variety of transactional identities (Maurer, Reference Maurer2005, p. 13). We don’t know the shape of tomorrow’s transaction media: What is emerging is social media money: private, surveilled, and data-driven. Some new money forms are hierarchical and segmented; others are universal. It is likely that we will be asked to trust corporations with our money and our data and our ability to get paid. The segmentation of these money forms means that you could be living in a separate transactional community than the person sitting next to you, while their plurality means that we will be constantly shifting between different communities and different forms of money.

And it is worth noting that some marginalized communities are experimenting with cryptocurrency to express resistance to the imposition of colonial economics, even though most cryptocurrency projects ultimately fail (Cordes, Reference Cordes2022).

5 The “Social” Future of Payments

Venmo users with public feeds broadcast a lot of personal information without realizing it. Friends can watch each other meet cute, fall in love, and break up in the course of a few months’ transactions. See, for example, the 2017 art project by Han Thi Duc, Public By Default, which finds poignant stories in the Venmo lives of others.

But Venmo can also be used to conduct social experiments, like the one that unfolded in June 2020, as the USA convulsed with anger over the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of White police officers. As tensions simmered, a handful of people, separately, in diverse geographic locations, began to experiment with a kind of informal reparations: peer-to-peer payments to Black people, either friends or strangers.

In Vermont, activists Moirha Smith and Jas Wheeler crowdsourced a list of Black people’s Cash App and Venmo accounts, titled “Wealth Redistribution for Black People in Vermont,” and posted it on Facebook. The accompanying “Letter to White People” noted that “one of the easiest … ways to support Black life, Black joy, Black safety, Black community is to give your money to Black people.” The list ultimately grew to over 300 names, and its organizers estimate that $65,000 was transferred in varying amounts.

Recipients reported that they felt weird about getting money from strangers, but did appreciate the funds (NPR, 2021). Meanwhile, a few Black people in other parts of the USA began to receive notifications that White friends and acquaintances had sent them small amounts of money, presumably as a form of reparation – but without any kind of organized campaign. These transfers tended to be small amounts of money, and recipients said they found them baffling and insulting (Gimlet, 2020).

Just as people are always finding new ways to communicate, we are also finding new ways to pay. Money is inherently social and new forms of sociality will necessarily be reflected in our payment systems. New money technologies, then, will offer an opportunity to make new kinds of transactional communities and also to make mistakes, forging a messy path toward an unknowable payments future.

1 Sociability in the Market

Individual participation in financial transactions has been a market feature since at least the days of the tulip mania. While in North America and Western Europe individuals have lost ground to institutional investors since the 1960s (Useem, Reference Useem1996), it is worth noting that in other major financial markets, especially Asian ones, they continue playing a significant role in terms of share of market transactions and volume. Since the late 2000s, though, we observe an increased participation of retail investors in market operations in North America and Western Europe too: Episodes such as the GameStop saga in 2021 – when groups of retail investors managed for a while to cause significant losses to some hedge funds – have brought some of this participation to public attention. Equally, periodic waves of popular enthusiasm for Bitcoin, tokens, or nonfungible tokens have contributed to this public attention, especially since of late crypto assets have gained regulatory legitimacy.

A common ground for these apparently disparate phenomena – GameStop was about the stock of a fading game retailing chain, while crypto manias are about a new and ill-defined class of assets – is the infrastructures that made them both possible. Chat forums such as Reddit, where retail traders coordinated their actions and summoned each other in real time, trading apps such as Robinhood, or crypto trading apps belong to the infrastructures that made possible this broader individual participation to financial transactions. Of course, as David Pinzur argues (this volume), we need to distinguish between ready-to-hand devices and infrastructures: Trading apps on smartphones and chatrooms belong to the former, while data centers, cloud computing, or transmission lines, as well as the algorithms calculating spreads on the GameStop stock (among many other things) would belong to the invisible background that solicits awareness only in moments of crisis. Yet, we have to notice here a few interrelated aspects: First, while communication infrastructures play a crucial role in finance (see also Coombs in this volume), social media have been seldom counted by academics as pertaining to financial infrastructures (though professional investors have recognized their significance). Second, we need to ask the question, how does social media, as part of this infrastructure, impact investor behavior? How do they (mis)align participants? What kind of social dynamics do they foster?

While financial markets are social by definition and communication has played a key role since their inception, this has been less recognized in benchmark models of financial decision-making, which have focused on individual behavior seen as striving toward utility maximization, grounded in an efficient processing of information, and risk aversion (e.g., Fama, Reference Fama1970). Forms of sociability and their consequences have been largely seen as imitative behavior and investigated as such (herding phenomena). Finance scholars have more recently recognized that social behavior in markets extends beyond imitation phenomena – hence the shift in focus toward “social finance” (Hirshleifer, Reference Hirshleifer2015) meant to emphasize a reorientation of investigations away from the presumption of individual decision-making to the effects of mediated social dynamics upon markets. While there is a decades-long body of financial research on individual investors, social media-influenced decisions are much less well understood. This opens a potentially fertile ground for dialogues between sociologists of finance and financial economists interested in social behavior.

Over the last fifteen years, social media have become more and more integrated with trading platforms, giving rise to what are called social trading platforms (STPs) (see also Tong and Preda (Reference Tong and Preda2023) for more detail). From the perspective of social research, STPs, as we have argued, add another dimension to the study of how evolving infrastructures reshape not only market institutions but also the behavior of participants.

The rise of general social media (such as Facebook) has been quickly followed by the rise of social media exclusively dedicated to traders and integrated with online trading, often built in a smartphone app (“Facebook” for traders). In the institutional realm, data providers such as Bloomberg have also integrated social messaging in their data provision. By offering much lower fees compared with traditional brokerages, coupled with a global outreach, STPs have managed to attract millions of individuals into financial transactions. Some of the largest STPs have millions of subscribers and revenues of over one billion US dollars (The Insight Partners, 2022). STPs offer platform-wide communication forums, as well as the possibility of building communication groups. Traders can exchange messages in real time – meaning as they trade and observe the market – either within distinct groups or with everyone who has an account on the platforms. At least as important, STPs use metrics for ranking the most successful traders and embed copying algorithms that allow participants to automatically copy the transactions of those traders deemed to be more skilled. Should the latter be successful, they receive a share of the profits made by those who have copied them. In this sense, STPs can be seen as integrating within broader societal trends of generating status differentials by means of commensuration and public rankings (Mennicken and Espeland, Reference Mennicken and Espeland2019).

For sociologists of finance and financial economists alike, there is very rich data to be studied from STPs, such as trading data, network data, and communication data (e.g., Tong and Preda, Reference Tong and Preda2023). These different types of data have become increasingly valuable with the rapid growth in technological innovations, such as AI and machine learning. Institutions or individuals may utilize these tools to construct trading strategies or even perform algorithmic trading. Trading data includes traders’ everyday trading records, such as daily balances, profits and losses, number of trades, trade sizes, and so on. Network data includes the structures of how traders are connected to each other as well as whether/how often they participate in the social communication features, such as online discussion forum (ODF) and one-on-one messaging. Communication data includes the discussion content on the ODF, revealing how traders perceive and frame market events, how they justify their trading decisions, and how they account for market events. As some STPs (and other trading platforms) have made this data available for social science research, it becomes possible to investigate how new communication infrastructures shape the social dynamics of markets. This chapter aims to shed light on this issue.

2 Sociability and Financial Performance

At least three streams of literature are directly relevant to the notion of “sociability” in relation to the financial performance of investors. We present three streams of literature to reflect the profound impacts of social interactions on financial decisions as well as the inherent skills and abilities of both professional and retail investors in financial markets. We aim to highlight the dynamic nature of human behavior, particularly in financial markets, in the presence of infrastructures that facilitate interactions among investors (e.g., social media). We argue that it is important to further understand the relationship between social interactions and investors’ financial performance, as well as the underlying mechanisms through which investors’ financial decisions are influenced.

The first stream of literature investigates the relationship between social interactions and investment biases, such as disposition effects (Heimer, Reference Heimer2016) and herding effects (Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018b). We should make clear that the notion of bias, widely used in behavioral finance, does not mean “irrationality” or “prejudice” or attachment to stereotypes on the part of investors. It simply means that observed behavior does not fit the predictions of the benchmark model of individual decision-making – as such, “bias” should be understood as deviation from such predictions (it is used interchangeably with “effect” in the sense of empirically observed effects). This being said, most studies are silent on how social interactions through media impact the financial performance of individual investors (Heimer, Reference Heimer2014, Reference Heimer2016; Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018a). Online communication represents a distinct form of social interaction. Research indicates that online chats can offer valuable information for individual investors, aiding their decision-making (Antweiler and Frank, Reference Antweiler and Frank2004; Das and Chen, Reference Das and Chen2007). A recurring theme in this body of literature is the emphasis on the significance of STPs (Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018a, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018b) and information systems (Abuelfadl, Choi, and Abbey, Reference Abuelfadl, Choi and Abbey2016) through which individual investors make their financial decisions. Online trading platforms, including social interaction features, provide a unique avenue for researchers to explore the impact of social interactions on investor behavior and financial performance. It is important to note, however, that a majority of individual investors tend to experience financial losses on such platforms (Preda, Reference Preda2017). For instance, studies using data from investment-specific online social networks, involving 5,693 foreign exchange retail traders with around 2.2 million trades from early 2009 to December 2010, have examined the influence of social interactions on the disposition effect (investment bias). These studies have shown that after gaining access to social networks, traders tend to exhibit nearly twice the magnitude of the disposition effect. This effect refers to a trader’s tendency to sell winning stocks while holding onto losing stocks (Heimer, Reference Heimer2016). By utilizing data from the Consumer Expenditure Quarterly Interview Survey spanning from 2000Q2 to 2010Q1, Heimer (Reference Heimer2014) has demonstrated a strong association between social interactions and active portfolio management. This is more prevalent among active investors compared to passive investors. It is important to note that this study cannot establish the direction of causality in the relationship between sociability and active portfolio management, as acknowledged by the author. Furthermore, there is an implication that social interactions may increase risk-taking, which could potentially have a negative impact on the financial welfare of traders.

However, a fundamental question remains unaddressed in existing literature: whether being sociable in the market, involving more social interactions, is advantageous or disadvantageous for the financial performance of individual investors. Notably, the existing literature does not distinguish between individual investors in terms of their social characteristics. Future research should bridge this gap by examining the financial performance of individual investors in relation to their varying levels of sociability in the market.

The second strand of literature is in alignment with broader social sciences and natural sciences. It seeks to uncover the impact of social interactions on the financial performance of individual investors, from the perspective of complex human systems and social networks (Saavedra, Duch, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Duch and Uzzi2011; Saavedra, Hagerty, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Hagerty and Uzzi2011; Liu, Govindan, and Uzzi, Reference Liu, Govindan and Uzzi2016). This strand’s focus lies in understanding the complexity of human systems and the collective wisdom of human interactions rather than merely examining the outcomes of financial decisions (Pan, Altshuler, and Pentland, Reference Pan, Altshuler and Pentland2012; Altshuler, Pentland, and Gordon, Reference Altshuler, Pentland and Gordon2015). Research in this area highlights that the patterns and content of instant messages (IMs) sent and received by professional stock day traders in typical trading firms can be interpreted as indicators of collective wisdom among individual investors across various platforms and can potentially influence investors’ financial performance (Saavedra, Duch, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Duch and Uzzi2011; Saavedra, Hagerty, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Hagerty and Uzzi2011; Liu, Govindan, and Uzzi, Reference Liu, Govindan and Uzzi2016). For example, Saavedra, Hagerty, and Uzzi (Reference Saavedra, Hagerty and Uzzi2011) used a dataset consisting of 66 individual stock day traders in a typical trading firm from September 2007 to February 2009, including over 1 million trades, with 55% being profitable. Their findings indicate a positive association between synchronous trading and the probability of making a profit, and the levels of synchronous trading are closely related to the patterns of IMs. Similarly, Liu, Govindan, and Uzzi (Reference Liu, Govindan and Uzzi2016) examined a dataset from 30 professional day traders, covering around 886,000 trading records and over 1.2 million IMs from January 2007 to December 2008. Their research reveals a connection between the expressed emotions in online communications and the profitability of actual trades. Traders who exhibit minimal or excessive emotional expression tend to make relatively unprofitable trades, while those with moderate emotional expression tend to make relatively profitable trades. Pan, Altshuler, and Pentland (Reference Pan, Altshuler and Pentland2012) utilized data from the online STP eToro and provided evidence that social trades, often associated with crowd wisdom, are more likely to outperform individual trades. However, it’s important to note that social traders are not consistently optimal performers (Pan, Altshuler, and Pentland, Reference Pan, Altshuler and Pentland2012). These studies operate with a notion of collective or crowd wisdom that in part sends back to the established concept of herding, and in part attempts to identify emerging phenomena in communication processes, based on large datasets: Communication is synchronized with trading actions, while interpretive frames (for market events) emerge within communication and become objectified (more specifically, are iterated across communication sequences and cannot be attributed to a single source anymore). The results point to at least two effects of communicational infrastructures: action synchronicity and objectification of interpretive frames.

These studies suggest that social communication and interactions play a significant role in the decision-making process of individual investors, highlighting the need for a more precise behavioral model (Pan, Altshuler, and Pentland, Reference Pan, Altshuler and Pentland2012). Furthermore, Altshuler, Pentland, and Gordon (Reference Altshuler, Pentland and Gordon2015), using data from the same online STP (eToro), which involved over 3 million individual investors and more than 40 million trades spanning from 2011 to 2014, revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between the average financial gains and the number of information sources used for decision-making. This suggests that having too little information is insufficient, while an excess of information can be harmful in terms of financial performance. As mentioned earlier, while some studies indicate an association between social interactions and financial performance, the literature does not investigate different degrees of communication in relationship to investors’ financial performance. Future research needs to address this question by taking into account different levels and degrees of communication and to develop an analytical model to explore the relationship between communicative interactions and the financial performance of individual investors.

The third strand of literature investigates the skills and abilities of investors (including both professional and retail) in relationship to the (positive) returns on investments. We distinguish here between professional and retail investors. This is because individual investors tend to exhibit different patterns of decision-making compared with professional investors (Preda, Reference Preda2017). In terms of professional investors, previous research indicates that approximately 24% of professional currency managers (drawn from a sample of thirty-four individual currency fund managers) have the potential to achieve significantly positive abnormal returns within a four-factor model in the currency market (Pojarliev and Levich, Reference Pojarliev and Levich2008). However, there is no evidence demonstrating that currency fund managers can consistently generate abnormal returns (Pojarliev and Levich, Reference Pojarliev and Levich2010). In contrast, when we consider retail investors, conventional wisdom suggests that, in the stock market, active trading individual investors tend to underperform passive trading individual investors. This underperformance is often attributed to the costs associated with a high level of trading (turnover) (Barber and Odean, Reference Barber and Odean2000). However, other studies present evidence that within the highly active individual investors there exist small subsets of individual investors that earn abnormal returns (Goetzmann and Kumar, Reference Goetzmann and Kumar2008; Dahlquist, Martinez, and Söderlind, Reference Dahlquist, Martinez and Söderlind2016). For instance, in Sweden’s Premium Pension System approximately 5.8% of active and 0.6% of highly active individual investors earn significantly higher returns, achieving average returns of 6.86% and 12.57% per year, respectively. This is in comparison to the remaining 93.5% of inactive individual investors who achieve average returns of 3.82% per year. These active investors manage their investments by reallocating money from different funds in their pension accounts (Dahlquist, Martinez, and Söderlind, Reference Dahlquist, Martinez and Söderlind2016). Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that around 2% of high-turnover and under-diversified individual investors’ portfolios perform better than their high-turnover and better-diversified counterparts in the stock market (Goetzmann and Kumar, Reference Goetzmann and Kumar2008). This demonstrates that active trading is not always hazardous to wealth, at least for some investors, although their proportion is quite small. In the context of individual currency investors, which is the focus of this chapter, certain studies employing a four-factor model (Pojarliev and Levich, Reference Pojarliev and Levich2008) indicate that individual currency investors can achieve abnormal returns even after accounting for transaction costs (Abbey and Doukas, Reference Abbey and Doukas2015).

Building upon these strands in existing literature, it becomes evident that they all place significant emphasis on communication and instant messaging within the context of STPs. Sociability, as implicitly depicted in these studies, revolves around engaging in communication with other traders through instant messaging and participating in community discussions. However, existing studies do not furnish clear-cut evidence regarding whether this sociability, understood as engaging in communication, has a positive or negative impact on financial performance. The underlying assumption is that the “wisdom of crowds” is superior to making decisions independently. But is this indeed the case? Does online communication with other traders enhance financial performance? On the one hand, one can argue that engaging in online communication enables traders to swiftly exchange information and acquire knowledge. On the other hand, however, an opposing argument can be made – that online communication distracts traders and exerts a detrimental influence on their performance. The question of whether sociability in the form of communication is ultimately advantageous or detrimental to financial performance remains a pivotal one.

3 Communication and Survivorship: A Case Study of STP

Communication alters investors’ trading behavior and decision-making process (Heimer, Reference Heimer2016; Han, Hirshleifer, and Walden, Reference Han, Hirshleifer and Walden2022; Tong and Preda, Reference Tong and Preda2023). Traders can be influenced by communication with friends and neighbors in terms of stock market participation (Hong, Kubik, and Stein, Reference Hong, Kubik and Stein2004; Guiso and Jappelli, Reference Guiso and Jappelli2005) and investing strategies (Han and Hirshleifer, Reference Han and Hirshleifer2012; Heimer, Reference Heimer2014). Empirical studies have documented that communication plays a role in retail traders’ decision to start trading in equity and foreign exchange (FX) markets (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Ivković, Smith and Weisbenner2008; Kaustia and Knüpfer, Reference Kaustia and Knüpfer2012; Changwony, Campbell, and Tabner, Reference Changwony, Campbell and Tabner2015; Chen and Roscoe, Reference Chen and Roscoe2017). Against this background, it is intuitive that traders can also be influenced by the conversations they have with other traders while trading, especially when they are discussing their ongoing trading activities and decisions. The consequences of social communication on traders can not only include the decision to participate and to adapt their trading strategies, but also the decision to continue (survive) or to cease (quit) their trading activities.

However, the relationship between survivorship in trading and social communication is unexplored in the literature. The investigation of the survival of traders has a distinct value for understanding the dynamics of a trader’s lifetime decision-making processes, which is different from the decision to participate (at the beginning of a trading life) and to choose their trading strategies (in the middle of a trading life). It is the decision to quit trading (at the end of a trading life) which finally concludes the story of a trader’s trading life. This decision constitutes an important aspect of the characteristics of a trader’s trading life.

It is not fully clear to the academic community what traders talk about and how the various aspects of their trading activities are influenced by the content of the conversations they have while making their trading decisions (let alone examining the impact of social communication on traders’ behavior). However, in the setting we explore in this chapter (data from a STP) we can observe what traders talk about while trading and how their behavior is subsequently altered by such social communication. We observe that traders are keen to talk about the future in the ODF. For example, “Today is looking very sketchy, I’m going to hold a long aud/jpy averaged about 77.90 and call it a week,” “What do yu [sic] think the EURUSD pair is going to do in the next 5 hours?,” and “Maybe MyFXtrade will have a real-time graph of these numbers in the future we can use.”

Intuitively, these discussions anchor traders’ expectations regarding the future. Traders should therefore be more curious to check out their expectations in the future and more likely to stick around to see what happens, compared to instances where they do not have any expectations at all. Consequently, traders should have the incentives to continue to stay (survive) in the market (as opposed to exiting the market) after having such conversations regarding the future of the market. Therefore, we examine whether social communication impacts the survival of traders.

Such an investigation is especially relevant since, as we have argued, technological evolutions have led to integrating communication with real-time trading. This integration changes the way transactions are organized, in the sense that it becomes possible to obtain real-time information about how fellow traders make decisions, swap opinions, and interpret market information jointly. Evidence shows that communication on social media can predict prices in equity markets and FX market movements (Ozturk and Ciftci, Reference Ozturk and Ciftci2014; Reed, Reference Reed2016; Lachanski and Pav, Reference Lachanski and Pav2017). FX markets are of particular interest because entry barriers are usually lower compared with the stock market, attracting a broader spectrum of investors of different financial means. Crypto asset markets are another domain of interest here, but studies of crypto traders are still in an incipient stage. Recently, studies have developed theoretical models in order to describe information transmission in the market through network communication, capturing the implications for asset prices (Ozsoylev, Reference Ozsoylev2004; Han and Yang, Reference Han and Yang2013; Han, Hirshleifer, and Walden, Reference Han, Hirshleifer and Walden2022).

4 Communication and Survivorship: Possible Explanations

We encounter several converging explanatory approaches. One, coming from the sociology of finance, is that market participants (i.e., professional traders) use face-to-face communication or online messaging to coordinate with each other, build joint expectations based on what they observe while trading, and reciprocal obligations (e.g., Knorr Cetina and Bruegger, Reference Knorr Cetina and Bruegger2002; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2009; Laube, Reference Laube2016). This explanation is grounded in studies of institutional trading floors and trading rooms, studies that do not examine massive online communication.

Another explanatory approach is that capitalist organizations generate fictional projections of the future as a means of coping with uncertainty (Beckert, Reference Beckert2016). However, such projections are generated at an organizational level, including various tools (e.g., business plans). It is unclear how they impact survival at organizational or individual level (if at all).

A third approach is provided by the anticipatory discourse theory which has been advanced in applied linguistics and psychology studies (Kinsbourne and Jordan, Reference Kinsbourne and Jordan2009; Streeck and Jordan, Reference Streeck and Jordan2009; Saint-Georges, Reference Saint-Georges and Chapelle2012; Poli, Reference Poli2019). Specifically, the anticipatory discourse theory suggests that “futurity is an inevitable component of text, talk, and more largely of social life, because human action has an intrinsically forward-looking nature” (Saint-Georges, Reference Saint-Georges and Chapelle2012). The “forward-looking nature” embedded in human communication takes two forms in the discourse processes, namely projection and anticipation (Kinsbourne and Jordan, Reference Kinsbourne and Jordan2009). Streeck and Jordan (Reference Streeck and Jordan2009) suggest that the forward-looking nature “consistently emerges in any discussion of interaction” (p. 93).

These insights reveal an important theoretical implication on the dynamics of human behavior subsequent to communication. That is “the very fabric of interaction and communication seems to be imbued with forward-looking anticipatory structures that facilitate ongoing, fluid interactions in a dynamic social environment” (Streeck and Jordan, Reference Streeck and Jordan2009, p. 95). Applied to the case discussed here, it would mean that communicational infrastructures present in markets embed such anticipatory affordances – they provide participants with opportunities to project the future repeatedly – and such anticipations ground actions in the market.

This theoretical implication is not exclusive to finance. We find that, in the context of STPs, these insights are evidenced by the discussion contents of the ODF. When reading through the content of the ODF, one significant feature is that traders are keen to talk about events in the future, share their predictions about the future, and discuss trading strategies based upon their perception of different states of the market in the future.

Given the discussed forward-looking nature of online discussions, we would expect that social communication increases the survival of traders. This is because traders, based upon the online discussions, may change their future expectations about the market or the platform, alter their perception of their own trading skills, and try out new trading strategies. These influences can be eventually translated into an increased survival probability of traders in the short term or a prolonged trading period in the long term. Therefore, we would expect that social communication increases the survivability of traders on a STP.

5 Sociability and the Wisdom of Crowds

This section aims to shed light on the effect of social media on the wisdom of crowds, and among different types of crowds, most of which are affected by communication. At least two strands of literature are directly relevant to the issue. The first one is the influence of social media on human behavior and the second one is the wisdom of crowds. As the literature shows that social media has broad influences on human behavior, we have sufficient grounds to expect that social media plays a (positive or negative) role in the decision-making process of individual investors. However, the wisdom-of-crowds literature focuses more on when and why crowds make better decisions. It remains unclear whether this wisdom can be influenced by social media and whether it is influenced differently according to different types of crowds. For instance, we can expect that social media accelerates crowd formation and/or polarization of opinions, and that there are differences in this respect between media and other communicational infrastructures.

5.1 The Impact of Social Media on Individual Behavior

There is ample evidence coming from nonfinancial domains showing that social media alters the behavior of individuals, affects life satisfaction, and even causes addiction-like symptoms and mental health issues (i.e., mental depression, see Shensa et al., Reference Shensa, Escobar-Viera, Sidani, Bowman, Marshal and Primack2017) in a variety of settings (Kuss et al., Reference Kuss, van Rooij, Shorter, Griffiths and van de Mheen2013; Leung, Reference Leung2014; Colucci, Reference Colucci2016; Alkhalaf, Tekian, and Park, Reference Alkhalaf, Tekian and Park2018; O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Dogra, Whiteman, Hughes, Eruyar and Reilly2018; Turel and Gil-Or, Reference Turel and Gil-Or2018). For instance, the use of WhatsApp is not directly linked to the academic performance of students, but the time spent using WhatsApp is proportionally related to symptoms of addiction (Alkhalaf, Tekian, and Park, Reference Alkhalaf, Tekian and Park2018). Moreover, besides the evidence suggesting that the negative relationship between social media addiction and well-being varies between women and men to some extent (Turel and Gil-Or, Reference Turel and Gil-Or2018), adolescents themselves often perceive social media as a threat to their well-being (O’Reilly et al., Reference O’Reilly, Dogra, Whiteman, Hughes, Eruyar and Reilly2018). Furthermore, symptoms resembling addiction and problematic behaviors associated with excessive or even compulsory social media usage are prevalent among the general population. These phenomena can be explained from the perspective of the morphology of the posterior subdivision of the insular cortex in human brain systems and processes (Turel et al., Reference Turel, He, Brevers and Bechara2018). It is estimated that more than 210 million people worldwide suffer from internet and social media addiction (Longstreet and Brooks, Reference Longstreet and Brooks2017).

Similarly, in the financial markets, social media is also found to have a significant impact on the behavior of individual investors, in terms of both financial performance and decision-making (e.g., the decision to quit or stay in the market). More recently it has been argued that social media significantly impacts the behavioral biases of individual investors, such as herding effect and disposition effect (Heimer, Reference Heimer2016; Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018a, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018b). For example, it is estimated that after the inclusion of social media on trading platforms, trading behavior is significantly influenced and, as a result, investors exhibit around twice as much disposition effect as before the inclusion (Heimer, Reference Heimer2016). In addition, on different types of trading platforms, investors tend to exhibit different magnitudes of disposition effect. For example, individual investors on an online STP, one that incorporates social media features such as the ability to observe the financial performance of other investors, exhibit a lower disposition effect when compared to individual investors using a traditional trading platform (Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018a). However, individual investors on a STP tend to exhibit higher levels of herding when compared with those within traditional trading environments (Gemayel and Preda, Reference Gemayel and Preda2018b).

5.2 The Wisdom of Crowds

Another strand of literature documents the collective effect of the wisdom of crowds, which is similar to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once collective anticipations of the future are adopted by a crowd and objectified, the crowd starts acting according to the anticipations and thus realizes them. A case in point is provided by the predictability of price movements based on analyzing the anticipative information produced by a group of people (Chalmers, Kaul, and Phillips, Reference Chalmers, Kaul and Phillips2013; Nofer and Hinz, Reference Nofer and Hinz2014; Azar and Lo, Reference Azar and Lo2016; Karagozoglu and Fabozzi, Reference Karagozoglu and Fabozzi2017; Polzin, Toxopeus, and Stam, 2018). For instance, through text analysis, research demonstrates that both articles and investor comments posted on a popular US social media platform for investors have the predictive power for stock returns and earnings surprises (Chen et al., Reference Chen, De, Hu and Hwang2014). Moreover, social media, serving as a tool to reflect investor sentiment, contains valuable information regarding future asset prices. For example, using Twitter data that includes tweets related to the Federal Reserve, a tweet-based asset allocation strategy outperforms several benchmarks. This includes outperforming a buy-and-hold strategy on the market index (Azar and Lo, Reference Azar and Lo2016). Furthermore, in the domains other than finance, such as in computer science (as well as in other social sciences), research shows that a complex human system, including social interactions between participants, has a significant impact on the decision-making processes of individuals. This decision-making in turn influences the financial performance of participating investors (Saavedra, Duch, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Duch and Uzzi2011; Saavedra, Hagerty, and Uzzi, Reference Saavedra, Hagerty and Uzzi2011; Pan, Altshuler, and Pentland, Reference Pan, Altshuler and Pentland2012; Altshuler, Pentland, and Gordon, Reference Altshuler, Pentland and Gordon2015; Liu, Govindan, and Uzzi, Reference Liu, Govindan and Uzzi2016). For instance, there is an inverted-U shaped relationship between information and the financial performance of investors who engage in sending and receiving IMs while making financial decisions. In this relationship, financial performance tends to improve as the information level increases, but it eventually reverses when information becomes excessive (Altshuler, Pentland, and Gordon, Reference Altshuler, Pentland and Gordon2015). The accuracy or efficiency of the wisdom of crowds relates to the diversity of the agents in the crowd (in terms of their skills and abilities) and to the structure of the crowd, such as population size and social structure (e.g., Hong and Page, Reference Hong and Page2001, Reference Hong and Page2004; Page, Reference Page2007; Economo, Hong, and Page, Reference Economo, Hong and Page2016). For example, a group with diverse agents sampled from a competent population outperforms a group with high-ability agents in terms of problem-solving, which indicates the tradeoff between ability and diversity on the wisdom of crowds (Hong and Page, Reference Hong and Page2004).

5.3 The Impact of Social Media on the Wisdom of Crowds

We can see from this that social media significantly impacts the behavior of individual investors in both financial markets and other domains of everyday life. As individuals are impacted under a variety of settings, it is worth considering how exactly this social feature influences the behavior of a group of participants and the associated outcomes. However, based on the literature on the wisdom of crowds in financial markets, there is not enough evidence on its temporal dynamics or under different circumstances, and on the reactions of the wisdom to external shocks (e.g., inclusion of social media). Furthermore, there is insufficient evidence to indicate which specific groups within the crowd are most affected by external shocks, particularly the inclusion of social media. There is also a gap in understanding how the wisdom evolves in the presence of social interactions compared to when there are no social interactions among individuals.

So far, this impact seems not to be very clear and there is a need to examine additional empirical evidence. One can argue that the inclusion of social media improves the wisdom of crowds. This is because individual investors get access to more sources of information which helps with their investing activities online. However, one can argue that the wisdom of crowds is negatively impacted by the inclusion of social media: The additional information disseminated through social media can be ambiguous or manipulated, while individual investors can also be distracted by information-exchanging activities. Similarly, it is also not clear who will be impacted more by social media. We could say that more intensive users will be impacted more. However, we could also say that less involved investors are impacted more, since they do not fully understand what is going on in these chats, given their lesser exposure to these activities and, eventually, they will get distracted by these activities. Consequently, intuition cannot help us much here. We need more evidence on these issues.

In summary, the puzzle here is how exactly the inclusion of social media impacts the decision-making of individual investors and, more importantly, which categories/groups of investors are most affected in terms of different levels of sociability. Trading platforms can be structured in various ways: some incorporate social media features, while others do not. Furthermore, among investors on STPs, there are those who actively utilize these social media features, and conversely, there are those who do not, even if these features are available. The crucial question is whether this disparity in the use of social media features an impact on the wisdom of crowds of individual investors. This inquiry can be focused on identifying which groups of investors are more profoundly affected by the inclusion of social media, particularly with regard to their level of engagement in these online social activities (e.g., the wisdom of more sociable vs. less sociable individual traders as distinct groups).

6 Conclusion

We have examined here two interrelated issues: the integration of communication infrastructures into trading platforms and the impact of social media on trading behavior. This chapter has primarily focused on three aspects: the potential impact of communication on trading decisions and associated outcomes (i.e., financial performance); decisions to quit trading (i.e., survivorship); and the wisdom of crowds (i.e., group decisions). We discuss existing literature on each of these aspects and highlight potential areas for future research.

We have formulated two arguments: The first, theoretical, is that communication infrastructures, long seen as essential in finance, need to include social media. These play a key role not only in the realm of individual traders – which we have discussed here – but also in that of institutional traders. As we have mentioned in the opening, institutional data providers have integrated social messaging into their offerings, while, to the best of our knowledge, we have limited evidence on the impact of social media on the behavior of institutional traders. We know that social media data is intensely used in devising trading strategies, including algorithmic ones. Especially as communicational infrastructures evolve rapidly under the impact of AI and machine learning, it is imperative to examine closer both their evolution and their impact in finance and beyond.

The second argument we have made here concerns the impact of social media on trading behavior. Evidence points to the fact that social media usage increases imitative behavior and conformism (perhaps not surprisingly), but also that financial performance, at least in the realm of individual traders, is not positively impacted by social media usage (except for a tiny minority). This raises, among others, regulatory issues with regard to the integration of social media with trading platforms, even more so as these media incessantly evolve and as market infrastructures are regulated.

1 Introduction

Through digitalization the reach of formal finance can be expanded to previously underserved territories and populations, thereby enhancing the capacity of financial infrastructures to increase monetary flows. This transformation is observable in developing countries, where various actors collaborate to integrate informal economic activities into financial circuits, trying to connect them to the financialized capitalist system and adapt financial infrastructures. This chapter focuses on the role of philanthrocapitalist actors in this process, specifically examining the efforts of the Mastercard Foundation to advance the digitalization of financial infrastructures around the African agribusiness sector.

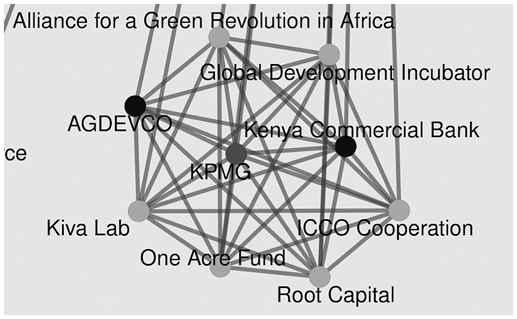

Our approach uses both critical development studies and science and technology studies (STS) to investigate infrastructuring processes. Grounded in the insights of Star and Ruhleder (Reference Star and Ruhleder1996), we perceive networking as a pivotal element of infrastructural change, encompassing interconnected social, organizational, and technical dimensions. We study the infrastructural transformation process by analysing the Foundation’s practices in agriculture and digital finance through discourse and programme analysis, as well as by examining its network of partnerships and fundings using social network analysis (SNA).

In keeping with Carse’s historical observation that infrastructure originally pertained to the organizational groundwork that preceded the construction of physical artefacts (Carse, Reference Carse, Harvey, Jensen and Morita2016), we posit that the Foundation contributes to financial infrastructural changes by assembling organizations, technologies, and capital through its networks, thereby creating platforms capable of (re)directing African resource flows into formal finance circuits. Previous research has shown that the Foundation helps to connect digital financial infrastructures to the financialized capitalist economy and that the firm Mastercard is frequently involved in those circuits (Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, and Lefèvre, Reference Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, Lefèvre, Chiapello, Engels and Gresse2023). This is not to suggest that these efforts to alter financial infrastructures are guaranteed to succeed; in fact, they encounter various challenges, gaps within existing infrastructures, and complexities in connecting them to peripheral economic elements such as rural finance. Nevertheless, we observe continued digitalization of agricultural finance in which the Foundation is actively involved. Our goal is to understand the project and shed light on the consequences of this process in terms of wealth circulation. We ask: How might the evolution of relationships reshape the credit landscape, impacting accessibility, costs, and organizational channels? We thus aim to contribute to social and policy debates about the power of (digital) financial infrastructures and their agency (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019; de Goede, Reference de Goede2021; Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021; Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten, Reference Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten2023).

We begin in Section 2 with our conceptual framework, followed by our methodology. Section 3 delves into the Foundation’s approach and analyses its project related to the emerging digital financial infrastructure in the African agribusiness sector. We then explore the various networks, organizations, and actors involved, and finally, we conclude by reflecting on the connections between this evolving infrastructure and global power structures in the financialized capitalist economy.

2 Philanthrocapitalism and Digital Financial Infrastructures

In a conception akin to an agencement, as described by Callon (Reference Callon2021), Pinzur (this volume) emphasizes, like Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn (Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019), that infrastructures do not inherently exist but instead take shape or materialize through labor that often remains unseen. We specifically argue that the contributions of organizations associated with philanthrocapitalism (or strategic philanthropy) to the emergence and transformation of market infrastructures are overlooked and remain largely imperceptible to analysts in critical development studies and STS. Nevertheless, entities like the Mastercard Foundation are significant actors in the realm of development and the capitalist economy. It is crucial to explore how the practices of these mega-foundations can potentially alter the circulation of wealth as they contribute to transformations such as the creation of new platforms, the digitalization of financial infrastructures, their recombination with other elements, and even the construction of new infrastructures.

Created by Mastercard International, a global payment technology firm that plays a major role in financialized capitalism, the Mastercard Foundation is one of the largest philanthropic institutions in the world in terms of capitalization. It is driven by its mission to advance education and financial inclusion as a catalyst for inclusive growth in developing countries. This raison d’être inherently places the Foundation within the process of financial infrastructures transformation and its digitalization. The critical literature on financial inclusion highlights the pivotal role of digital financial technologies in extending financialization at the margins (e.g., Langevin, Reference Langevin2019; Natile, Reference Natile2020; Bernards, Reference Bernards2022). These mechanisms are vital in establishing financial circuits that link peripheral agricultural markets to the dominant circuits of financialized capitalism. To make payment and credit transactions viable and profitable, operational digital financial infrastructures are essential.

By looking at the prevailing constellation of actors involved in the Foundation’s financial inclusion project and targeting marginal spaces in the global political economy through a neo-colonial analytical lens, we seek to identify the power relations being played out. To do so, we draw upon a broad concept of infrastructures conceived as a background operation and define the financial ‘infrastructuring process’ as an agency process of emerging new capabilities born at the confluence of innovative practical configurations to link, in this case, segments on the periphery of formal economic and financial circuits. This perspective is essential for incorporating infrastructural agency because, as de Goede (Reference de Goede2021, p. 353) contends regarding global payment infrastructures, their inherently political nature holds the potential to ‘reinscribe power relations and reroute money flows’.

The Mastercard Foundation’s existence is intricately linked to global power structures. As part of its 2006 IPO (initial public offering), the firm Mastercard International provided the Foundation with its capital from the firm’s own shares. With a substantial endowment of over $39 billion (Canada Revenue Agency, 2022), the operational capacities of the Foundation are thus partly built on the profitability of the firm Mastercard, a dominant financial capitalism corporation. What Mastercard International does in global capitalism is provide technological financial services to states, consumers, and enterprises to make their financial transactions fluid and secure. Simply put, the business case for the firm is that the higher the volume of transactions through their financial infrastructures, the more user fees are collected. Our previous work revealed that the Foundation’s practices reinforce Mastercard’s global organizational power by helping establish new market infrastructures, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, and Lefèvre, Reference Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, Lefèvre, Chiapello, Engels and Gresse2023). In this chapter, we narrow our focus to agribusiness, a strategically vital area for development institutions, for-profit entities, public entities, and philanthrocapitalist organizations. Globally, the Foundation ranks among the top ten private foundations that invest in agriculture (OECD, 2018, p. 61), with a significant portion of its investment portfolio directed to this sector (OECD, 2023).

The infrastructures discussed in this chapter go beyond being mere physical conduits; they involve farmers who are integrated into the global political economy, albeit through various pathways and socio-technical relations. On a relational level, we aim to differentiate what impacts the potential for inclusion and wealth capture in this infrastructuring process. We explore how new infrastructures emerge and interconnect with existing ones and consider the adaptable nature of the ‘installed base’ (Star, Reference Star1999, p. 382). Socio-technical relations may in fact evolve ‘often subtly – as alternative bundles of sociotechnical relations arise and interact with sociotechnical relations that already exist’ (Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten, Reference Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten2023, p. 461). We put forward the following question: What new relationships between actors and technologies alter the landscape and influence who can access credit, at what cost, and through which organizational channels?

3 Method, Empirical Materials, and Analytical Grid