Freedom is one of the values humans most cherish. We are free if we are not imprisoned or enslaved. We are free if we are not unduly coerced or constrained in our choices or actions. Freedom can be difficult to define, but surely, we know when we lose it or when it has been taken from us.

Human rights advocates are rightly concerned when certain groups of people are exploited for their labor, like migrant workers forced into virtual slavery on fishing vessels or toiling in fields for little pay. They are concerned when groups of people are exploited for their bodies, as when young girls are forced into the sex trade. And they are concerned when groups of people are not allowed to move about or speak freely or engage in cultural rituals that are important to them. We value the freedom to choose our family and friends, to bear and raise children, to think for ourselves, and to work for a decent living. Of course, there is no such thing as pure, unadulterated freedom – we are controlled by our unconscious impulses, genetics, unspoken social conventions, and by government rules that ensure public safety and order. But we are nonetheless free in important respects. Some measure of freedom is fundamental to human well-being: it provides the substrate for human flourishing.Footnote 1

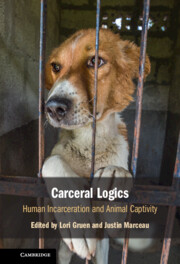

Yet although we prize our freedom above all else, we routinely deny numerous freedoms to nonhuman animals (animals) with whom we share our planet. We imprison and enslave animals, we exploit them for their labor and their skin and bodies, we constrain what they can do and with whom they can interact. We do not let them choose their family or friends, we decide for them when and if and with whom they mate and bear offspring, and often take their children away at birth. We control their movements, their behaviors, their social interactions, while bending them to our will or to our self-serving economic agenda. Animal incarceration is so pervasive and insidious that we often do not even notice that animals are being held prisoner. If we think about it at all, we imagine animals as creatures so different from us that they don’t value the same things – and, in particular, that they don’t value their freedom because they lack the cognitive awareness to know what freedom is.

But, in fact, animals are like us in the most important respects. All animals want and need food, water, air, sleep. They need shelter and safety from physical and psychological threats, and an environment they can control. And like us, they have what might be called “higher-order” needs, such as the need to exercise control over their lives, make choices, do meaningful work, form meaningful relationships with others, and engage in forms of play and creativity. Some measure of freedom is fundamental to satisfying these higher-order needs and provides a necessary substrate for individuals to thrive and to look forward to a new day. Although they might not write books about the concepts of freedom and incarceration, animals nonetheless value their freedom and suffer in captivity just as we do.

The goods that animals value stand in stark relief against the lives that we force on them. Animals are held captive in a dizzying array of venues: zoos, factory farms, research laboratories, wet markets, fur farms, breeding facilities, pet store shelves, and so on and so on. Billions of animals around the globe are subjected to a lifetime of incarceration. (Incarceration and captivity are taken to be the same, for the purposes of this chapter.)

Incarceration clearly is more complicated and far-reaching than merely being behind bars. When we put nonhumans and humans in prison, we are dealing out punishment. Being physically confined is understood as a temporary deprivation of life’s higher-order goods. But with animals, the routine deprivations of prolonged incarceration are not understood by humans as a punishment, but rather as a neutral action, or even – as is the case with pets – a favor we do them.

Although there might be some reasonable conversation or debate about the appropriateness of incarceration for humans, there is no reasonable justification for incarcerating animals. Animals should not be behind bars, whether those bars are real or metaphorical. Animals don’t commit crimes, they aren’t violent offenders, and they don’t disregard any real or imagined social contract with humankind. Any confinement of animals against their will (which would be pretty much every instance of confinement one could imagine) counts as incarceration.

12.1 The Myriad Harms of Captivity

The fact that there is an entire literature dedicated to so-called captivity effects should leave us in no doubt that captivity causes suffering. “Captivity effects” refers to the range of physical, physiological, and even neurobiological changes induced by captive conditions. These captivity effects are similar in humans and other animals. The vast empirical database on captivity effects in nonhuman animals spans a broad range of species – from chimpanzees, dolphins, and wolves to domesticated animals such as dogs, cats, pigs, and chickens, to reptiles, amphibians, and fish – kept in a range of captive conditions, from the most obviously captive (the cows, chickens, pigs, and other animals on factory farms) to the animals caged in research and testing laboratories, to animals caged in zoos, to the animals who are captive in more ambiguous ways, such as pet dogs and cats.Footnote 2 (Because the literature uses the language of “captivity” rather than “incarceration” we will use the term captivity in this section – but take it to be synonymous with incarceration.)

Captivity – including physical confinement, social isolation, and chronic exposure to stress – leads to measurable physiological changes in the brain, including loss of neural plasticity, long-term activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis,Footnote 3 and permanent changes in brain morphology.Footnote 4 It can lead to changes to immune function,Footnote 5 reproductive behaviors,Footnote 6 circadian rhythms, and psychological trauma.Footnote 7 The loss of freedom often manifests in observable abnormal behaviors. Since many of the people who will read this book come from the perspective of human incarceration, we offer a few specific examples of the physical and psychological sequelae of incarceration documented in animals. In particular, we give a few examples of what, in the scientific literature, are called “stereotypic behaviors or stereotypies” but which we could more loosely call “captivity-induced madness.”

Stereotypic behavior is the term used to describe animal behavior which is invariant, repetitive, and serves no obvious function. Stereotypes are thought to be caused by brain dysfunction brought on by stress-induced damage to the central nervous system. It is important to note that stereotypic behaviors do not occur in the wild; they are a product of captivity, a captivity-induced psychosis.Footnote 8

Irregular pacing behavior is often observed in captive animals who, in the wild, have large home ranges. This behavior pattern is referred to as a repetitive locomotion stereotype, or locomotory stereotypy. Polar bears, to give one example, are known to do poorly in captivity. A study published in Nature suggested that the reason why locomotory stereotypies may be so common in polar bears is that in the wild, the animals can range over tracts of land as large as 185,000 square miles each year.Footnote 9 Locomotory stereotypies are well documented in elephants, tigers, lions, wolves, and other canids.Footnote 10 The frenetic weaving of the mink back and forth within their tiny wire cages, as seen in undercover video footage of mink farms, is a disturbing example of locomotory stereotypy or captivity-induced madness.Footnote 11

Grooming to the point of baldness, feather plucking, and other self-mutilation behaviors are sometimes called self-directed stereotypies.Footnote 12 These behaviors occur in a wide range of species including rodents and primates in research laboratories, parrots, and other birds in captivity and cats in shelter environments or other stressful situations.

Oral stereotypies, in which an animal performs repetitive and seemingly functionless oral and oronasal activities, are prevalent in captive ungulates such as cows, pigs, and horses.Footnote 13 One example is a repetitive movement of the jaw, such as the “sham-chewing” commonly seen in pigs kept in gestation crates.Footnote 14 The behavior mimics the exact movement of the jaw when food is being consumed. However, sham-chewing is performed in the absence of food. Oral stereotypies surrounding food and eating are a good place to explore why providing animals with their basic needs – food, shelter, enough space to turn around – isn’t enough to ensure that they don’t suffer from profound distress caused by captivity. Next to breathing, eating is the behavior most essential for survival, and different species are exquisitely adapted to meet their survival needs within the ecosystems in which they evolved. Many of the behavioral patterns of a given animal are directed at finding food, and animals are highly motivated to perform these food-acquiring behaviors, because they are basic to survival. Providing a cow with a trough of grain may satiate the cow’s physical hunger but will not allow the cow to use any of the behavioral skills she has evolved to acquire food for herself. The behavioral urge to forage is present, even when cows are fed ad libitum. And a strong behavioral urge or motivation that goes unsatisfied leads to welfare problems. Other commonly seen oral stereotypies include tongue-rolling, object licking, chewing on cage bars or chains, and polydipsia or excessive drinking.

Often, and unfortunately for animals, the behavioral sequalae resulting from captivity are described as “problem behaviors” – this is to say, they are problematic for us, the animals’ keepers. This is perhaps most obvious in relation to animals caught in the wheels of the food industry, where the sequalae of incarceration pose a challenge to productivity. For example, agonistic behaviors among chickens or tail-biting behaviors among piglets kept in unnaturally crowded conditions can lead to injury and death – and loss of revenue. The human response to these manifestations of suffering is indecent: instead of addressing the source of suffering, we go for a Band-Aid solution, and one that simply piles one cruelty on top of another. Chickens have their beaks cut off with a hot knife and piglets have their tails cut off with clippers. A less obvious example – but closer to home for many of us – are the perceived behavioral problems of dogs who are confined to a home or crate or backyard for long periods of time: excessive barking, obsessive compulsive behaviors such as self-grooming to the point of developing lick granulomas. Many people who live with dogs fail to connect their animals’ “problem behaviors” with psychological distress, boredom, or frustration, and, as with the chickens and piglets, simply compound cruelty with more cruelty: excessive barking is “fixed” with a shock collar or a one-way trip to the shelter.

It can be difficult to untangle the threads of harm arising from animal incarceration: which aspects of animal suffering are attributed to the specific conditions of their captivity and which are the result of captivity itself? This distinction is critically important because the focus of attention in discussions of animal welfare and animal ethics is often on reducing specific harms suffered by captive animals, and never questions the broader harms of captivity itself. The physical, psychological, social harms to animals caused by the captive state are not or at least not always the result of poorly executed captivity, but of captivity itself. Take, for example, the problems of captive snakes, which have been highlighted by the work of Clifford Warwick. Most snakes in captivity as kept in enclosures that are too small to allow full extension of the snake’s body, and snakes are harmed physically and psychologically by not having enough space to spread out.Footnote 15 But they are also harmed by captivity itself, no matter whether their enclosure is adequately large relative to their body size.

Suffice it to say that alleviating some of the suffering caused by “bad captivity” may be a good short-term goal, as we move beyond cultural and economic structures that institutionalize violence toward animals. But improving the lot of captive animals is not enough. There is no such thing as “good captivity” or “good incarceration” for animals, and we need to stop pretending that there is. A well-appointed prison is still a prison.

12.2 Fake Freedoms: The Appropriation of “Freedom” Discourses

Many people who have taken an interest in issues of animal protection are familiar with the “Five Freedoms.” The Five Freedoms have become a popular cornerstone of animal welfare around the world and in various contexts of animal incarceration.

The Five Freedoms originated in the early 1960s in an eighty-five-page “Report of the Technical Committee to Enquire into the Welfare of Animals Kept under Intensive Livestock Husbandry Systems.”Footnote 16 This document, informally and widely known as The Brambell Report, was a response to public outcry over the abusive treatment of animals within agricultural settings. Ruth Harrison’s 1964 book Animal Machines brought readers inside the walls of the newly developing industrialized farming systems in the United Kingdom, what we have come to know as “factory farms.” Harrison, a Quaker and conscientious objector during World War II, described appalling practices like battery cage systems for egg-laying hens and gestation crates for sows, and consumers were shocked by what was hidden behind closed doors.

To mollify the public, the UK government commissioned an investigation into livestock husbandry, led by Bangor University zoology professor Roger Brambell. The commission concluded that there were, indeed, grave ethical concerns with the treatment of animals in the food industry and that something must be done. In its initial report, the commission specified that animals should have the freedom to “stand up, lie down, turn around, groom themselves and stretch their limbs.” These minimal requirements became known as the “freedoms,” and represented the conditions the Brambell Commission felt were essential to animal welfare.

The Commission also requested the formation of the Farm Animal Welfare Advisory Committee to monitor the UK farming industry. In 1979, the name of this organization was changed to the Farm Animal Welfare Council, and the “freedoms” were subsequently expanded into their current form. The Five Freedoms state that all animals under human care should have:

1. Freedom from hunger and thirst, by ready access to water and a diet to maintain health and vigor.

2. Freedom from discomfort, by providing an appropriate environment.

3. Freedom from pain, injury and disease, by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

4. Freedom to express normal behavior, by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and appropriate company of the animal’s own kind.

5. Freedom from fear and distress, by ensuring conditions and treatment, which avoid mental suffering.

The Freedoms are now invoked not only in relationship to farmed animals, but also to animals in research laboratories, zoos. and aquaria, and even to companion animals in shelters and breeding facilities. The Freedoms appear in nearly every book about animal welfare, can be found on nearly every website dedicated to food animal or lab animal welfare, form the basis of many animal welfare auditing programs, and are taught to many of those working in fields of animal husbandry.

It is worth stopping for a moment to acknowledge how forward thinking the Brambell Report on animal freedoms was. The report was crafted at a time when the notion that animals might experience pain was still just a superstition for many researchers and others working with animals. The Brambell Report not only acknowledged that animals experience pain but went a giant step further by also providing evidence that they experience mental states and have rich emotional lives. The report (the full text of which very few people who ascribe to the Five Freedoms actually read) said plainly that making animals happy involves more than simply reducing sources of pain and suffering, but also involves providing them with positive, pleasurable experiences.

Yet although widely hailed as a huge step forward, the Brambell Report was arguably the worst thing that has happened to animals in the past century. The Five Freedoms became the cornerstone of an academic discipline called “animal welfare science” and provided a justificatory framework – a logic of incarceration which we call “welfarism” – for thinking about and justifying the widespread confinement and exploitation of animals. The Five Freedoms have become shorthand for “ethical treatment of animals.” They provide, according to a current statement by the Farm Animal Welfare Council, a “logical and comprehensive framework for analysis of animal welfare” and are typically the end of the conversation about what animals need and want. Welfarism delivers a scientific and moral buttressing for incarceration, under the auspices of caring for animals and giving them Freedoms. Under the welfarist regime, the number of animals under incarceration around the globe has been steadily climbing.

Why the Brambell Commission fixed upon the word “freedom” in their formulation of welfare guidelines remains unclear – no record exists of how this language came to be adopted. It is hard to imagine that the crafters of the Freedoms failed to recognize the fundamental paradox: how can an animal in an abattoir or battery cage be free? Being fed and housed by your captor is not freedom; it is simply what your caregiver does to keep you alive. Indeed, the Five Freedoms are not concerned with freedom but rather define the outer limits of incarceration; they provide guidance for keeping animals under conditions of profound deprivation.

Welfare concerns generally focus on preventing or relieving suffering, and making sure animals are being well-fed and cared for, without questioning the underlying conditions of incarceration that shape the very nature of their lives. We offer lip service to freedom, in talking about “cage-free chickens” and “naturalistic zoo enclosures” and in producing a steady stream of academic papers offering incremental improvements to animal prisons. But real freedom for animals is the one value we don’t want to acknowledge because it would require a deep examination of our own behavior. It might mean we should change the way we treat and relate to animals, not just to make cages bigger or provide new enrichment activities to blunt the sharp edges of boredom and frustration, but to allow animals much more freedom in a wide array of venues.

12.3 Working toward Abolition

A great deal of advocacy on behalf of animals focuses on “improving welfare” by paying attention to the Five Freedoms. This amounts to making animal prisons somewhat nicer, somewhat kinder and gentler. But the fundamental violence against animals remains intact. Welfarism and “the Freedoms” do considerable damage to animals by reinforcing and even providing improved moral padding for the logic of incarceration. This explains why some of the most vocal advocates for animal welfare work for zoos, slaughterhouses, and animal research laboratories, and sit on the boards of organizations who support the industrialized incarceration of animals.

Even the literature on captivity effects has been entwined into the logic of animal incarceration, using what we are learning about animal cognition and emotions – the very research that confirms how much animals have to lose in captivity – to make their incarceration incrementally less torturous while simultaneously reinforcing the structures of violence that keep them imprisoned.

The typical justification for holding animals captive is that although captivity may impose some harms, these harms are justified by the benefits that accrue from these practices. But one of the golden rules of ethics is that in a balancing of harms and benefits, it is unjust for the harms to befall one group and the benefits another. In the case of incarcerated animals, all the harms fall on animals while all the benefits fall to us. The animals have everything to lose and nothing to gain. This is a serious justice issue and a blatant abuse of power.

It is hard not to see a profound moral problem in our unjust incarceration of billions of animals. Making incremental welfare improvements and giving lip service to Five Freedoms is a face-saving maneuver: let’s admit that holding animals captive is not ideal and causes some harm, so let’s make the prison experience less unpleasant by decreasing the harms of captivity. The audaciousness of the workaround is remarkable: incarcerating animals is morally wrong, so let’s give them “freedoms.” The Five Freedoms are really designed to liberate us, allowing us to slip quietly past the prison gates, ensuring our peace of mind in the face of animal suffering.

The incarceration of animals, in all its myriad forms, should stop. But it cannot and will not suddenly tomorrow. A phase out is key. The animals who are currently in captivity will need to remain so, because it is unlikely that they could survive on their own and offering them “freedom” without the requisite skills to survive and without a home or family will only compound their suffering. But starting tomorrow there should be no more captive breeding of animals in captivity, for captivity. No animals should be captured from the wild and made captive, even for experiments that are aimed at saving the species from extinction since it is not fair to ask an individual to suffer for the sake of a group. (We wouldn’t justify this with humans, so shouldn’t with animals either.)

Abundant scientific research supports the idea that animals suffer physically and psychologically when held captive. It is not only the “aversive” experiences felt within captivity – the too-small cages, the boredom of eating the same food every day for your whole life, or the lack of sensory stimulation – but the captivity experience itself, the loss of self-determination, bodily integrity, the sense of experiencing life as the kind of animal that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years of evolution have prepared you to be. Captivity is a harm because it robs animals of their own lives.