The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE US CONSTITUTION WAS RATIFIED IN August 1920, setting off a flurry of speculation about how newly enfranchised women would vote in the upcoming presidential election. Although women in fifteen states already enjoyed the right to vote by 1920, politicians and observers nonetheless expressed uncertainty about what to expect. “Women’s Vote Baffles Politicians’ Efforts to Forecast Election” claimed one newspaper.1 Another reported that “anxious politicians of both parties are sitting up nights worrying about [women’s votes].”2 Appeals to new women voters emphasized issues specific to women, such as equal pay and maternity care, and issues related to women’s roles as mothers, such as child labor and education.3 In the aftermath of the election, many claimed that women had handed the election to Republican Warren G. Harding, for reasons ranging from his good looks to the Republican party’s support of women’s suffrage.4 Others attributed the Republican advantage to specific groups of women; the women many considered most likely to turn out to vote in 1920 – suffrage activists – tended to be native-born white women, who like native-born white men, were expected to vote Republican.5

Almost a century later, the presidential election of 2016 – with Tweets, Russian meddling, and the first-ever woman major party nominee – differed dramatically from the presidential election of 1920. And yet, there are striking similarities between the two when it comes to women voters. Interest in the potential impact of women was again pervasive: “The Trump-Clinton Gender Gap Could be the Largest in More Than 60 Years,” predicted NPR.6 “Women May Decide the Election,” claimed The Atlantic.7 Parties and candidates continued to target women voters, defined as women, and especially as mothers: Hillary Clinton highlighted her famous declaration that “women’s rights are human rights” in an “appeal to female voters,” explained NPR.8 Donald Trump was “Targeting ‘Security Moms,’” according to Time magazine.9 As in 1920, post-election analysis focused on the distinct contributions of different groups of women to the Republican victory: “Clinton Couldn’t Win Over White Women,” emphasized popular election website, FiveThiryEight. “Why Hillary Clinton lost the white women’s vote,” echoed the Christian Science Monitor.10

The presidential elections of 1920 and 2016 both featured widespread speculation about the impact of women voters. In both elections, appeals to and analysis of women voters often were grounded in assumptions and stereotypes about women’s interests as women, and particularly as mothers. In both elections, the Republican candidate won. Yet, the actual political behavior of women in these two elections was quite different. In 1920, our best estimates are that about one-third of eligible women turned out to vote. In 2016, 63% of women cast ballots in the presidential election. Women were much less likely to turn out than were men in 1920 (a nearly 35 point gap, on average), but women were slightly more likely to turn out to vote than were men in 2016 (4 point gap). Women’s partisan preferences also shifted. Republicans had a slight advantage, at most, among women in 1920, but by 2016, it was Democrats who maintained a consistent advantage among women. Both women (63%) and men (60%) overwhelmingly supported Harding in 1920. Exit polls conducted in 2016 indicated that only 41% of women voted for Trump compared to 52% of men.11

A Century of Votes for Women describes and explains how women voted in presidential elections from the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment until the present day. Our brief discussion of women voters in the first (1920) and last (2016) elections covered here highlights four key arguments of this book. First, the actual voting behavior of women – both the extent to which they turn out to vote and the parties and candidates they tend to support – has varied considerably over time. We trace the evolution of women’s turnout and vote choice across the past century briefly below and in detail in the chapters that follow. Second, popular discourse about “the woman voter” varies but also is characterized by remarkably consistent themes and assumptions over these ten decades, despite extraordinary changes in women’s lives. Third, women (like men) are not a monolithic group and other identities and experiences are often as or more important than gender for women’s voting behavior. Fourth, history matters. Women’s (and men’s) electoral behavior must be understood within the unique political, social, and economic context in which it takes place.

Women Voters Over Time

Women’s voting behavior has evolved since the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. The story of voter turnout is largely one of women becoming increasingly similar to men. In terms of vote choice, however, women have become more distinct. The first women voters lagged considerably behind men in their tendency to enter polling places, although the extent to which women and men turned out (and the size of the turnout gender gap) varied from state to state depending on the political context.12 By 1964, women’s increasingly high turnout combined with women’s greater numbers in the eligible electorate translated into more women than men casting ballots for president. Since 1980 women have been more likely than men to turn out in presidential elections.13

The historical trajectory of women’s vote choice – which parties and candidates women tend to support at the polls – is a more complicated story. In the main, the ebbs and flows of women’s vote choice have reflected the broader electoral trends of the nation as a whole: Republicans were the majority party, consistently winning presidential elections, in the period immediately after extension of the suffrage. Women, like men, voted overwhelmingly Republican. In a dramatic shift, Democrats wrested majority status from the GOP during the New Deal period of the 1930s, and would maintain that status for at least the next 50 years. Women, like men, contributed to the emerging and persistent Democratic majority. As that majority status eroded across the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, both men and women shifted toward the Republican party. These shared shifts are significant. Despite women’s historic exclusion from the electorate, differences in gender socialization, and women’s distinct position in the social and economic structure, women and men generally cast ballots for the same parties and candidates.

Yet, in some places and in some times, women’s vote choice diverged from that of men. Women voters were slightly more likely than men to cast Republican ballots in some elections prior to 1964. Women voters have become consistently more likely than men to support Democratic candidates, and men to support Republicans, since at least 1980.14 This does not mean that a majority of women cast Democratic ballots in every election since 1980; Republicans won majorities of women’s votes in 1984 and 1988. But the percentage of men casting Republican ballots is larger than the percentage of women doing so in every presidential election from 1980 on, even when Republicans captured a majority of the votes of both women and men. In some recent elections – 2000, 2004, 2012, and 2016 – a majority of women favor the Democratic candidate, while a majority of men favor the Republican.15

Framing Women Voters

Women voters have been the subject of considerable interest and speculation across these ten decades. Observers and campaigns have often assumed women’s gender per se is the key to understanding women’s political behavior and interests. Women’s presumed natural disinterest in the rough-and-tumble world of politics explains their relatively low turnout in early presidential elections, for example.16 Women’s interest in issues specific to women – suffrage, equal pay, abortion – have been invoked to explain their choice of party and candidates.17 Fundamental personality and values differences, such as women’s greater compassion, are assumed to explain women’s support for social welfare programs and the parties associated with them.18 The interests of women voters have been repeatedly understood in terms of their roles as wives and mothers: Women oppose war (ranging from Korea to Iraq) because they fear their husbands and sons being sent off to fight. Women are concerned with inflation and high prices because they manage the household finances. Women prioritize education and health care because of their maternal concern for the well-being of children. These beliefs about the interests and behavior of women as voters has shaped women’s political influence, the creation of public policy, and the ways in which candidates and parties appealed to female voters. We seek to not only describe how women voted, but how women voters were understood by contemporaries and scholars.

Women are Not a Voting Bloc

American women are diverse. Not all women turn out to vote or vote the same way. Gender is not the most salient political identity shaping electoral behavior for most women (or men). Factors such as race, ethnicity, class, religion, employment, education, and marital status all shape women’s (and men’s) electoral behavior in important ways. Women’s experiences also are shaped by their location; where women exercise their electoral rights is often as important as the fact that they are women. Among the most important aspects of women’s diversity is race. The Nineteenth Amendment prohibited the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex. It left in place, however, legal and extra-legal practices which denied voting rights on other bases, most notably on the basis of race in the American South.19 As a result, most women of color continued to be excluded from the suffrage until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 and face unique challenges today.20

Diversity means that it is impossible to speak of “the woman’s vote.” There is no one stereotypical woman, but rather as many “kinds” of women voters as there are kinds of men voters. Multiple factors determine women’s decision to turn out to vote and who to vote for, many of which trump the impact of being a woman. Women also vary in their political views, generally and specifically related to women’s rights. Women have both opposed and supported suffrage, equal pay, abortion rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, and family leave policies. Women are capable of holding and expressing sexist beliefs – both benevolent and hostile – with consequences for their electoral behavior.21 We describe women’s rates of turnout and party vote share in a general sense, but our further analysis emphasizes the considerable variability of electoral behavior across different groups of women.

The Importance of Historical Context

Finally, voters do not cast ballots in a vacuum. Rather, the decision to turn out to vote and for whom to cast a ballot is made within a specific moment, characterized by events, issues, conditions, and candidates that shape and frame decisions in particular ways. For that reason, we have organized our discussion of women voters historically, which allows us to highlight the specific issues and candidates, as well as the social, economic, and political developments, that shaped electoral choices for women and men, and how those actions were understood, in each election and era.

Major political developments ranging from the New Deal and the Cold War to the civil rights movement and 9/11 have transformed American politics for citizens in general and often for women in particular. Technological and economic developments, such as the expansion of mass-produced clothing and food and the shift from an industrial to a post-industrial economy, have had social and political impacts broadly, as well as specifically for women. Significant changes in the conditions of women’s lives – the increasing participation of women in the paid workforce, the expansion of occupations open to women, changes in marital practice and stability, and shifting patterns of pregnancy and child-rearing – have always had political consequences.22

The chapters that follow provide ample support for these arguments and observations, and we return to them again in the conclusion. In this introductory chapter, we prepare readers for our discussion of women voters across the past century in three ways: First, we identify and discuss some of the key issues involved in thinking about and examining women as voters in American politics across 100 years. Next, we briefly review the many monumental developments in the lived experience of women’s lives across this ten-decade period. Finally, we describe, in the most general sense, the turnout and vote choice of women voters from 1920 through 2016, highlighting general trends that are explored in greater detail throughout the book. We conclude the chapter with a preview of the chapters which follow.

The Study of Women Voters

This is a book about women voters. Specifically, it is a book about the turnout and vote choice of American women in presidential elections from the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 through the election of 2016. We seek to understand how women used the vote – and how political observers and scholars explained women’s use of the vote – across the past 100 years. In this section, we review a number of the key issues that arise when we examine women as voters.

Women Voters and the Gender Gap

To understand women voters as women, we must be attentive to the voting behavior of the rest of the voting age population – that is, to men. In other words, if we want to understand how, if at all, women as a group employ their right to vote in a distinctive manner, we need to compare their turnout and vote choice to that of men. The difference between the political behavior of women and men is known in both popular and scholarly parlance as the gender gap. The term “gender gap” was coined by feminist activists seeking to gain political leverage from the fact that women were less likely than men to cast ballots for Republican Ronald Reagan in 1980. Activists argued that the gender gap was a reaction to Reagan’s anti-feminist positions; by revealing the electoral costs of those actions, they hoped to create political pressure in favor of women’s rights.23 The size, consequences, and reasons for the gender gap remain politically contested; Republicans, for example, have an incentive to highlight the problems Democrats seem to have in attracting men’s votes, while Democrats frame their advantage among women as a seal of approval for their policy positions. Despite its political origins, the term gender gap is now in widespread use to describe any and all differences between women and men ranging from economics and health to movie dialogue and celebrity chefs.24

The divergent voting preferences of women and men remain the original definition and prevailing use of the term gender gap. For the sake of clarity, we use the term “turnout gender gap” when speaking of differences between the percentage of eligible women turning out to vote versus the percentage of men doing so. Differences between the percentage of women voting for a candidate or party (usually the winning one) and the percentage of men who do so are described as the “gender gap” or the “partisan gender gap.” Measurement of the gender gap is contested, but our measure is the standard approach used by activists, the press, and scholars since the gender gap was “named” after the 1980 election.25

We are cognizant that the gender gap can obscure as much as it reveals, particularly when considering change over time. A change in the size of the partisan gender gap, for example, can result from dramatic shifts in men’s preferences while women remain steadfast for one party, shifts among women but not men, or shifts in the party preferences of both women and men. Each has different implications for our understanding of the political behavior of women and of the impact of gender on electoral politics.26 For this reason, our practice is to present women’s and men’s turnout and vote choice separately, rather than the gender gap alone, in most cases.

The Male Standard

While useful, comparisons of women’s and men’s voting behavior can be problematic.27 In voting, as in other areas, the behavior of men is often presented as the standard; that is, male turnout and vote choice are understood as normal and any divergence from the male standard by women is viewed as a puzzle to be solved. Women’s turnout is considered high or low relative to male turnout. Women’s support for particular parties is only presented as notable when it diverges from the partisan preferences of men.

The focus on comparison with men can lead to distorted and inaccurate understandings of women’s political behavior. In recent decades, popular and scholarly discussions of the gender gap gave the impression that women were strong supporters of the Democratic party. Women of all racial and ethnic groups have been more supportive of Democrats than similar men since at least 1980, but in the case of white women that does not always, or even usually, mean that women supported Democrats more than they supported Republicans. Indeed, a majority of white women supported the Republican candidate in every presidential election since 1950, save two. Black women, on the other hand, have consistently given a majority of their votes to Democratic candidates to an even greater extent than have black men during this period. A focus on the gender gap combined with a failure to recognize diversity among women gives the mistaken impression that all women vote Democratic.28

The male standard hampers our understanding of women as voters in other ways as well. When political activists identified the partisan gender gap in favor of Democrats in 1980, popular discourse focused on women as the cause of any divergence in party preference between women and men. Men’s choice of candidates was presumed to be the norm; women’s a deviation. Not surprisingly, then, explanations for the gender gap (discussed in Chapter 3) have tended to focus on women per se – women’s growing autonomy from men, women’s reaction to the parties’ changing positions on women’s rights issues, the impact of women’s increased education and employment, and so on. Yet, in reality, the emergence of the current gender gap was as much or more due to the behavior of men as it was women: Men shifted to the GOP after the 1960s, while women remained Democrats or shifted toward the Republican party to a lesser extent than men (see Chapter 7).29

The male standard also is problematic when men’s political behavior is treated as not just normal, but as normatively ideal. For example, one of the key findings of early voting research was that women were less likely to express a sense that they personally can influence the political world; that is, they were less likely to express political efficacy. This shortcoming was viewed as key to understanding why women lagged behind men in voter turnout but also as a failure of women as citizens.30 Yet, later scholars noted that framing women as deficient for not expressing more personal efficacy assumes that men’s tendency to view themselves as effective political agents was a reasonable and even laudable belief. But is it? Political scientists Sandra Baxter and Marjorie Lansing explain:

Instead of interpreting the difference as an inadequacy in women, we suggest that given the very limited number of issues that citizens can affect, the lower sense of political efficacy expressed by women may be a perceptive assessment of the political process. Men, on the other hand, express irrationally high rates of efficacy.31

We compare women’s and men’s voting behavior throughout this book, as one way of determining when gender is, and is not, meaningful for electoral behavior. We avoid claiming that one group’s behavior is the standard against which the other’s behavior should be judged or offering conclusions than how one group measures up normatively against the other.

While our focus is on the specific, political act of voting, we also are aware that the male standard can shape even our understanding of what is political. When we judge women by whether they vote, donate to political campaigns, know national political figures, or run for office, we are holding women to a standard of political activity that is defined by things men have traditionally done. When we turn to other behaviors, such as working with community organizations, volunteering on civic and political campaigns, and knowing everyday economic information (like prices) – all of which are absolutely political – a very different picture of women’s engagement emerges.32 In this book, our concern is with traditional electoral participation, but we remain cognizant of the diverse other ways in which women engage in political activity.

One Hundred Years?

We begin our examination of women voters with the presidential election of 1920, held just weeks after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. For the study of women voters, the election of 1920 is both “too late and too early.”33 The election of 1920 is too late because women had been voting in American elections for decades prior to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Indeed, a few propertied women cast ballots in several New England states in the late eighteenth century. As states expanded voting rights for men without property in the early decades of the nineteenth century, they closed those state-level loopholes for women.34 As a result of the determined work of suffragists in state campaigns in the second half of the nineteenth century, women in fifteen states had secured the right to vote in most elections prior to 1920 (see Chapter 2).35 The national woman suffrage amendment was the culmination of a long-term process of expanding, and sometimes constricting, voting rights for women in the United States.

At the same time, the election of 1920 is much too early to declare universal female suffrage accomplished. There were short-term delays for women; four Southern states refused to let women vote in 1920 due to their failure to meet registration deadlines that occurred months before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. (Other states with similar deadlines adjusted their rules to accommodate new women voters.)36 Women in those states were unable to vote in a presidential election until 1924.

In the longer term, Jim Crow practices in the South meant most black women continued to be disenfranchised on the basis of their race for decades following the presidential election of 1920.37 The continuing disenfranchisement of black women after suffrage occurs in a broader context in which suffragists, especially in the final decades of the struggle, often adopted racist and ethnocentric arguments in favor of giving women the right to vote, claiming that native-born white women would counter the votes of black and immigrant men. How could such men, suffragists explicitly argued, deserve the right to vote when respectable white, middle-class women did not? Prominent suffragists engaged in overtly racist language and behavior and excluded black suffragists from white suffrage organizations and activism. The woman suffrage cause was linked to racism and Jim Crow long before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified.38

Just as the Fifteenth Amendment (on which the Nineteenth is expressly modeled) forbade the denial of voting rights on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” the Nineteenth Amendment similarly prohibited the denial of voting rights “on account of sex.” However, neither the Fifteenth nor the Nineteenth Amendment established an affirmative right to vote, akin to the rights to speech, assembly, due process, and so on enshrined elsewhere in the US Constitution. Indeed, the Constitution itself says little about voting and does not guarantee the right to vote to anyone (see Chapter 2). The Nineteenth Amendment thus did not directly confront legal or extra-legal practices that denied people of color, including women of color, the right to vote in the South.39

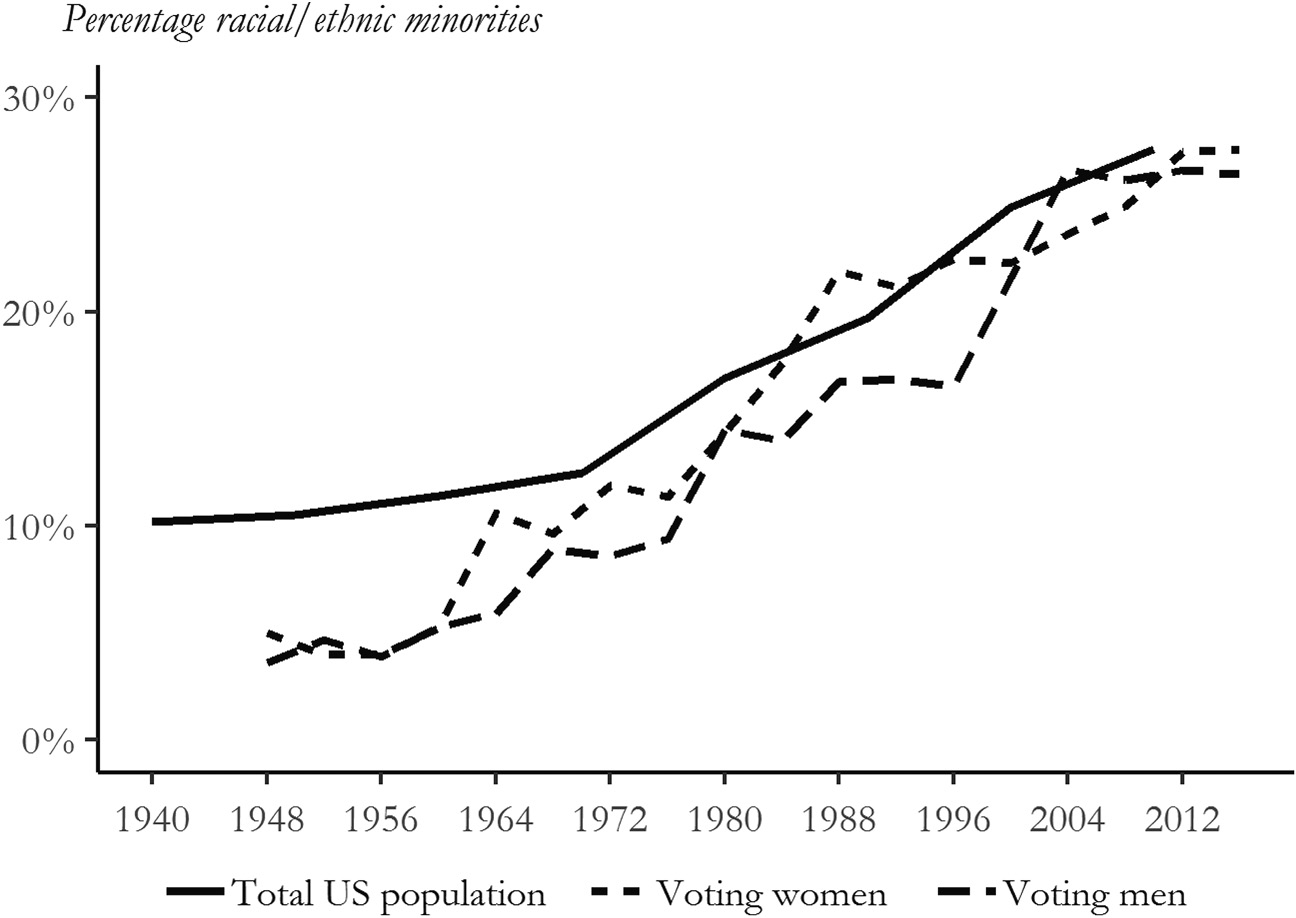

The impact of Jim Crow on access to the vote for black women was enormous. Nationwide, women of color comprised only about 5% of the total female electorate in any election before 1964, despite black women being 11% of the population (see Figure 1.1).40 Nonetheless, some black women were able to vote prior to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Historian Suzanne Lebsock details the considerable lengths to which local governments and the Democratic party went to keep black women from registering (and to encourage white women to register in order to counteract black women at the polls) in 1920s Virginia. These efforts were not entirely successful, however; Lebsock concludes: “By the end of 1920 Virginia was still a bastion of white supremacy, but several thousand black women had achieved the dignity of citizenship,” often as a result of great individual and collective effort and cost.41 The implementation of Jim Crow varied, in part based on the relative size of the black community; the larger the African American population, the greater the efforts were to suppress their votes. In their study of black and white Southerners (see Chapter 5), Donald R. Matthews and James W. Prothro report African American registration rates varying from zero to more than 60% across Southern counties in 1960. On the whole, however, the reality was that while the Nineteenth Amendment prohibited the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex, Jim Crow and other practices kept the vast majority of African American women from exercising their voting rights for decades.

Figure 1.1 Racial composition of US voters shows women of color generally lacked access to the ballot until the 1960s (ANES and US Census), 1948–2016

While the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment did not mean that all women had access to the ballot, it is nonetheless a landmark for women in American politics. The amendment transformed women’s relationship to the political sphere, as well as the “boundaries between male and female.”42 Politics as the sole province of men and the home as women’s natural place were considered fundamental aspects of masculinity and femininity. By prohibiting discrimination in access to the ballot on the basis of sex, the Nineteenth Amendment recognized women as political actors in their own, independent right, challenging long-held norms about women, men, and the nature of politics itself.43 The installation of those principles into the US Constitution represented a profound challenge to traditional political structures that excluded and disparaged women. The Nineteenth Amendment thus was a key step in a long, not always straightforward, process of expanding political equality and access to power for women. The centennial of that achievement provides an opportunity to take stock of how American women have used their hard-won right to vote and how women voters have been understood by contemporary observers and later scholars.

Identifying Periods of Analysis

In the chapters that follow, we divide the past ten decades into five time periods to facilitate our understanding of women voters. How did we select these periods? We are focused in this book on (1) the voting rights of women, (2) the shifting political, economic, and social context, especially with regards to women, and (3) the actual voting behavior of women. All three of these dynamics have experienced considerable change during the past 100 years. All three are clearly interrelated. Yet, each has followed a unique trajectory. The empirical chapters are structured around key shifts in all three.44

Legal order.

In terms of legal suffrage rights, the period 1920 to the present day might be described as a single period in which women enjoyed voting rights post-Nineteenth Amendment. That amendment prohibited discrimination in access to the vote on the basis of sex.45 Unlike the prohibition on race and previous servitude as voting qualifications in the Fifteenth Amendment, there was no state-implemented, aided, and endorsed retraction of suffrage rights for women qua women after 1920.

Yet, the right to vote is not a constant for all American women across this period, as we have discussed. Most notably, the same formal and informal institutions that denied the vast majority of African American men access to the ballot in the first half of the twentieth century applied with equal force to African American women. Despite the concerns of white Southerners that the repression of black voters would be more difficult in the case of black women, the Jim Crow South found ways, including violence, to deny women of color the vote. For the vast majority of black women, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a transformative moment as or more central to voting rights than is the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. There are therefore at least two important shifts in women’s voting rights across this century.

Gender order.

Both the expectations for and reality of women’s political, economic, and social lives – what we term gender orders – is a second dynamic that organizes our analysis. Gender orders describe the actual practice and structure of society and institutions, but also are ideational in the sense of a set of culturally shared, idealized feminine and masculine roles, characteristics, behaviors, and stereotypes, as well as conscious and unconscious biases related to sex and gender.46 Traditional views of gender (or what we term traditional gender orders) are characterized by distinct and conservative sex roles and norms, and greater male power and status relative to women. Egalitarian gender orders, on the other hand, institute or propose a view of women and men as fundamentally equal in capacity, opportunity, and rights. These are of course ideals, with most periods characterized by a mix of both traditional and egalitarian gender norms.

While the Nineteenth Amendment certainly represents a challenge to a key aspect of traditional gender norms, it did not necessarily disrupt other types of gender traditionalism which were consequential for women’s use of the ballot. For example, continuing (and legally enforced) sex segregation in the workforce and sex role differentiation in the family have significant consequences for women’s use of the vote.47 At the same time, while the expansion of suffrage to women was likely both an expression of and helped to bring about shifts in widely held views about women and gender (i.e., ideation), the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment did not necessarily change assumptions about women’s political capacities or interests, as we show.

The previous 100 years have been characterized by dramatic and successful challenges to traditional gender order and shifts toward egalitarian gender order. Progress is not linear, however, but characterized by the undermining of some aspects of traditional gender order and the reconfiguring and reassertion of others. The challenging of sexual mores in the “Roaring Twenties” followed by the opening up of opportunities for women in the workforce made possible by the Great Depression, and especially the Second World War, created a period of shifting gender roles and norms in the 1920s through the early 1940s, although most sex-based legal structures remained unchanged. On the other hand, the 1940s through the early 1960s are generally understood as a period in which traditional femininity and gender roles were reasserted in culture and institutions. The late 1960s and 1970s witnessed the emergence of the second wave of the women’s movement, dramatic shifts in women’s participation in the paid workforce and in the structure of families, and significant transformations in gender roles in the United States and throughout the world. A conservative backlash against those changes contributed to the emergence of the modern culture war in the 1980s and 1990s. Understanding the evolving framing of and rhetoric surrounding women as voters requires attention to the dynamics of gender orders in the United States over time.48

Electoral behavior.

Women’s voting behavior shifts over time, as does our capacity to observe it. With very few exceptions, official vote records do not and cannot distinguish between the turnout and vote choice of women and men. Reliable mass surveys did not begin to appear until the mid-1930s, and were not widely available until the 1950s. Exit polls did not come into wide use until the 1970s. Thus while commentators and scholars make claims about how women voted from the 1920 election onwards, the quality and quantity of the available evidence varies considerably over time. Even when reliable public opinion data are available, the degree to which informed analysis of how and why women voted as they did is disseminated through the press and to the public varies as well.49

We trace stability and change in the two key aspects of women’s electoral behavior: turnout and vote choice. Women remained less likely to turn out than men until 1980, although due to the greater numbers of women in the population and their eligibility to vote, there were more women than men in the active presidential electorate from 1964 onwards.50 The story for vote choice is more complicated. Conventional wisdom (and some data analysis) has long described women voters as favoring the Republican party, but only to a very small degree, before the early 1960s. Women and men were then largely indistinguishable in their party preference until 1980. From that time on, women have been consistently more likely to favor Democratic candidates, although the presence and extent of that advantage varies across groups and over time.51

Organizing the century.

Focusing on these three dimensions – the status of legal voting rights relevant to women (legal order), gender roles, norms, and structures (gender order), and the actual voting behavior of women (electoral behavior) – we divide the century into five periods: the first women voters (1920–36); feminine mystique and the American voter (1940–64); feminism resurgent (1968–76); the discovery of the gender gap (1980–96); and the new millennium (2000–16). In each empirical chapter, we specify key aspects of the political context, with special attention to shifting gender norms and practices as well as relevant shifts in the legal environment in which women cast their votes. The ultimate goal of each chapter is then to describe and review trends in, and explanations for, the turnout and vote choice of women voters.

Our first period (1920–36), for example, kicks off with a dramatic shift in women’s legal access to the franchise with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment (legal order). Restrictions on voting by people of color and immigrants, however, continue to bar some women from the vote. We highlight important changes in gender roles (gender order), as sexual mores were loosened during the “Roaring Twenties” and technological changes – electricity, indoor plumbing, mass-produced food and clothing – were transforming the domestic obligations of women. Yet views about women’s political interests remained rooted in motherhood and domesticity, and assumptions about women’s essentially apolitical nature remained strong.52 Until recently, information about the actual turnout and vote choice of women (electoral behavior) has been virtually nonexistent as public opinion surveys were unavailable or unreliable during this period. Nonetheless, both contemporary and later observers made rather definitive claims about how women used their votes.53 In this period, we use recent research to inform our description of the turnout and vote choice of the first women to enter polling places after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. Each empirical chapter offers a similar overview of a key period for women as voters in American politics.

Turnout and Vote Choice in Presidential Elections

When we examine women voters we are interested in two distinct, but related political choices. First, the choice of whether to exercise the right to vote – the participation decision. Second, the choice of candidates – the vote choice decision. These choices are intertwined: People turn out to vote largely in order to cast ballots for particular parties and candidates.54

A number of scholars interested in the electoral behavior of women have focused on gender differences in party identification, rather than actual vote. These two behaviors are closely related; the most powerful predictor of vote choice is the party with which a citizen identifies. Not surprisingly, respondents who say they identify as Republicans tend to vote for Republican candidates, and respondents who claim Democratic identification tend to vote for Democratic nominees.55 The strength of the association between party identification and vote choice shifts over time, but it is usually quite strong.56

Party identification is generally more stable than vote choice over the lifetime, so focusing on vote choice allows us to observe more clearly the way women respond to specific electoral contests and contexts. Gender differences in vote choice tend to be associated with gender differences in party identification, and the arguments for why women tend to be more or less likely than men to identify with specific parties are largely indistinguishable from the arguments for why women tend to be more or less likely to vote for each party’s candidates. In our discussion of the causes of gender differences we highlight explanations offered for both vote choice and party identification.

Our focus is on women voters in presidential elections. Certainly presidential elections have been the focus of much of the rhetoric and analysis around women voters. As the most prominent and salient of American elections, presidential contests provide an ideal opportunity to trace the electoral behavior of women and men. In other races, most notably for the US House and US Senate, the powerful impact of incumbency can overwhelm other effects, including gender. While the patterns we identify, such as women’s increasing propensity to turn out and the recent relative Democratic advantage among women voters, characterize elections for other offices, those races are characterized by their own unique dynamics as well.57

Sex and Gender

We are cognizant of our use of the terms sex and gender. It has become commonplace to treat sex as a biological marker distinguishing females from males, while gender is understood as the social meaning we give to sex; gender is the set of stereotypes, norms, and expectations that society assigns to the biological categories of women and men. Importantly, gender characterizes, shapes, and defines not only human beings but also institutions, social organization, and the state.58

Some would argue that the two broad categories we examine here – women and men – are examples of simple sex difference. In a strict sense, the vast majority of the research we describe and present distinguishes between women and men, but does not measure gender (in terms of femininity and masculinity) or gender identity. However, we choose to use the term gender in this book to highlight that our focus is on “men and women as social groups rather than biological groups.”59 Our analysis of the turnout and vote choice of women and men relies on observations of the reported (or assumed) gender identity of citizens in census reports, exit polls, and public opinion surveys. Explanations for how and why women vote and vote the way they do are deeply rooted in gender role expectations and norms that are sustained and reproduced through social, economic, and political interactions, institutions, and practices. And perhaps most simply, the widespread adoption of the term “gender gap” has generated a strong association between the term gender and the political behavior of women and men. We recognize that gender is a far more complicated concept than the simple difference in women’s and men’s observed electoral behavior that we examine here. Recent work, for example, has begun to explore non-binary gender identification and voting behavior as well as the impact of masculinity and femininity distinct from sex. One benefit of our use of the term gender is that it emphasizes the complexity of how gender roles and stereotypes operate, and thus captures the complexity of the electoral behavior we seek to understand.

The Evolving Lives of Women Voters

It would be difficult to overstate the extent of social, economic, and political change across the last century. The Great Depression, postwar boom, oil crisis, inflation, tech boom, and real estate crash. American’s rise as a global power and recurring struggles on the world stage. Social and racial progress and backlash. These developments and many more provide the backdrop for the electoral contests of this age in general, and for women voters in specific ways.

The 100-year period we examine here also is characterized by dramatic changes in the lived experiences of American women. In this section, we highlight three developments since 1920 that are particularly consequential for women and politics: Women have become more likely to complete college; more likely to delay marriage and families; and more likely to participate in the labor force. The combination of these factors implies a fairly radical change in the social and economic status of women relative to men, as well as absolute gains in economic security and educational attainment. The implications of these changes in status are clear for women’s turnout: Each change should increase turnout. The impact of these changes on women’s ties to the major political parties is more complicated. While we explore the political implications in more detail in later chapters, we set the stage here by describing the three major changes in broad strokes.

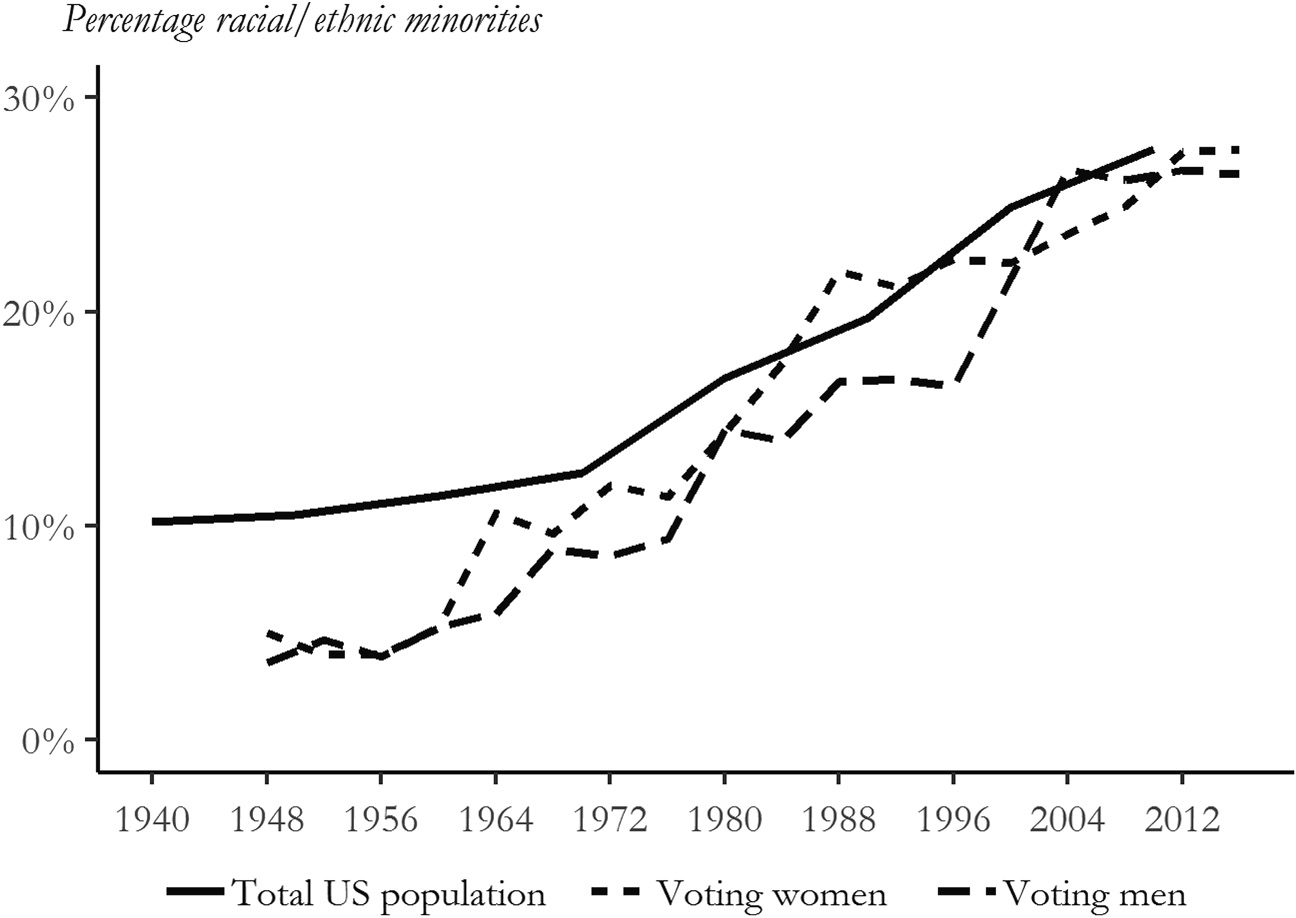

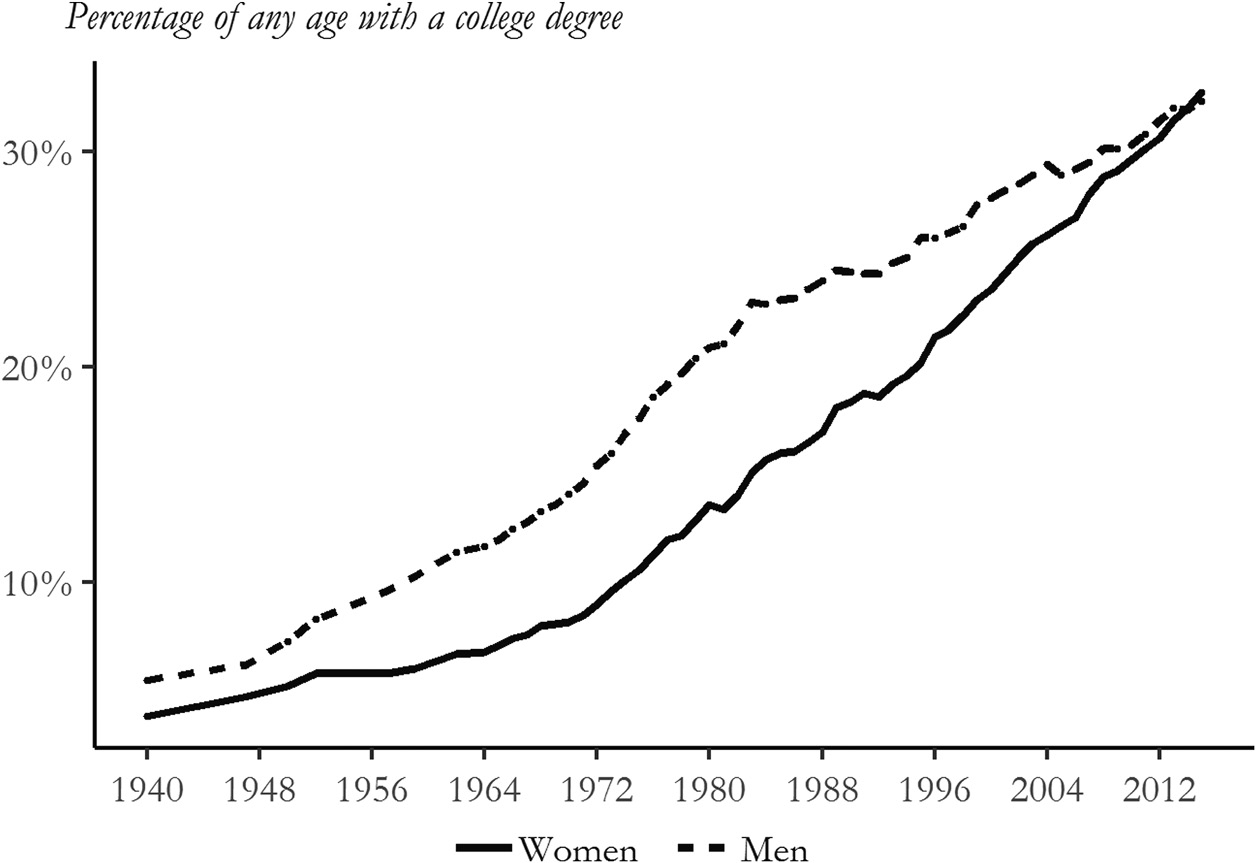

Education

Both women and men realized major gains in educational attainment after 1940, but the timing of those gains was quite different for the two groups, as data from the US Census demonstrates in Figure 1.2. College completion rates for men rose faster than for women before 1983. In that year, women were a third less likely to have four years of college or more than men. At the same time, younger women began to graduate college at higher rates than younger men, narrowing the overall gap between men and women each year. While generational differences remain, the educational attainment advantage among women in younger cohorts is now large enough to make the rate of college completion similar between women and men overall. Today, women are more likely than men to have completed four years of college and this educational advantage is likely to persist and grow over time.

Figure 1.2 Women catch up to men in college attainment by 2015 (US Census), 1940–2016

Work

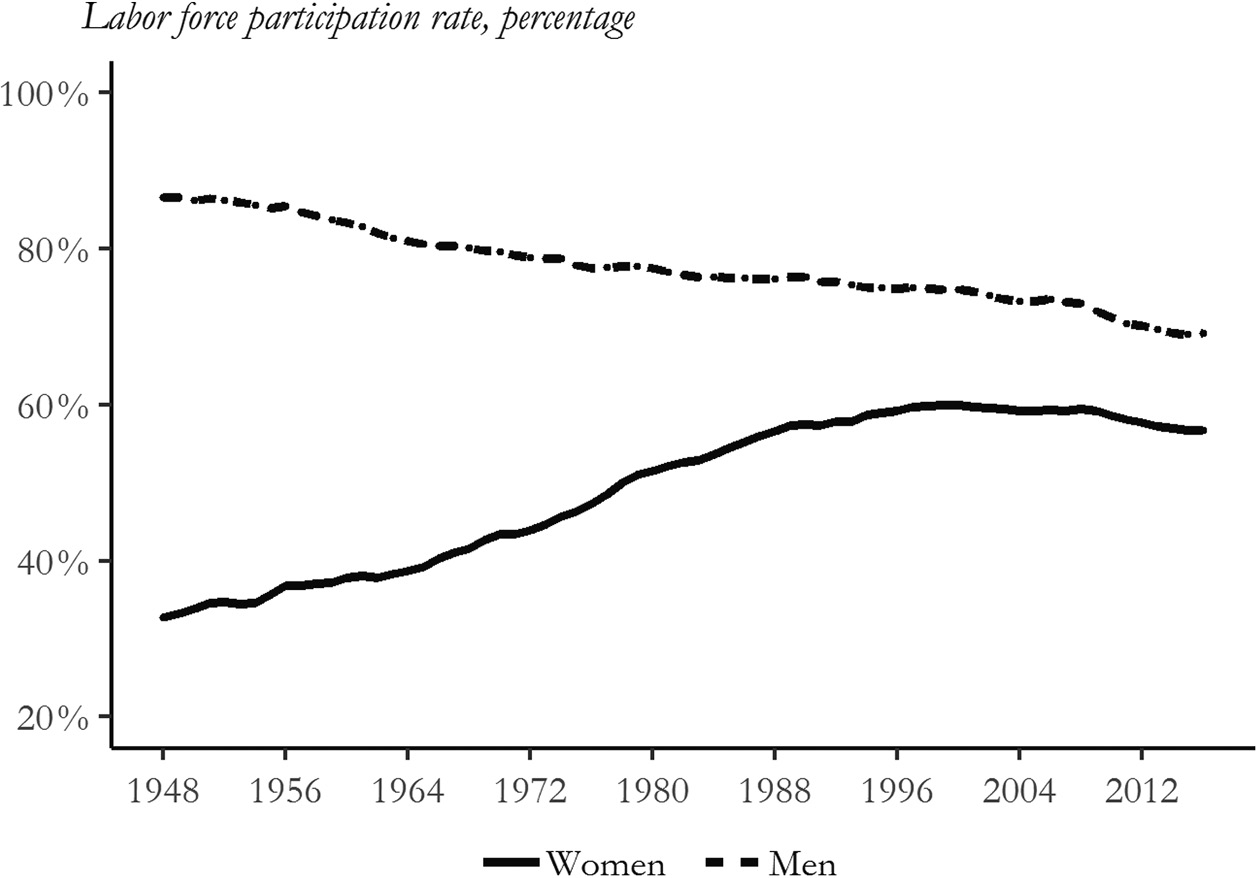

Women had increasingly entered the paid workforce since the nineteenth century, particularly poor, African American, and immigrant women. In the 1920s, increasing numbers of young and unmarried white women joined the labor force as well. The Second World War famously witnessed a sharp expansion in women’s labor force participation; while the rate of women engaged in paid work declined after 1945, it did not return to prewar levels, and continued to rise thereafter. Labor force participation rates after the Second World War reveal very different trajectories for men and women (see Figure 1.3).60 Men had nearly universal labor force participation in 1948, but the proportion of men aged 16 and over engaged with work dropped to nearly 70% by 2016. The percentage of women in the paid workforce, on the other hand, increased dramatically after 1948 (when it was barely over 30%) and plateaued after 2000 at about 60%.

Figure 1.3 Women’s labor force participation grows sharply, while men’s declines, in the postwar era (Bureau of Labor Statistics), 1948–2016

Marriage and Family

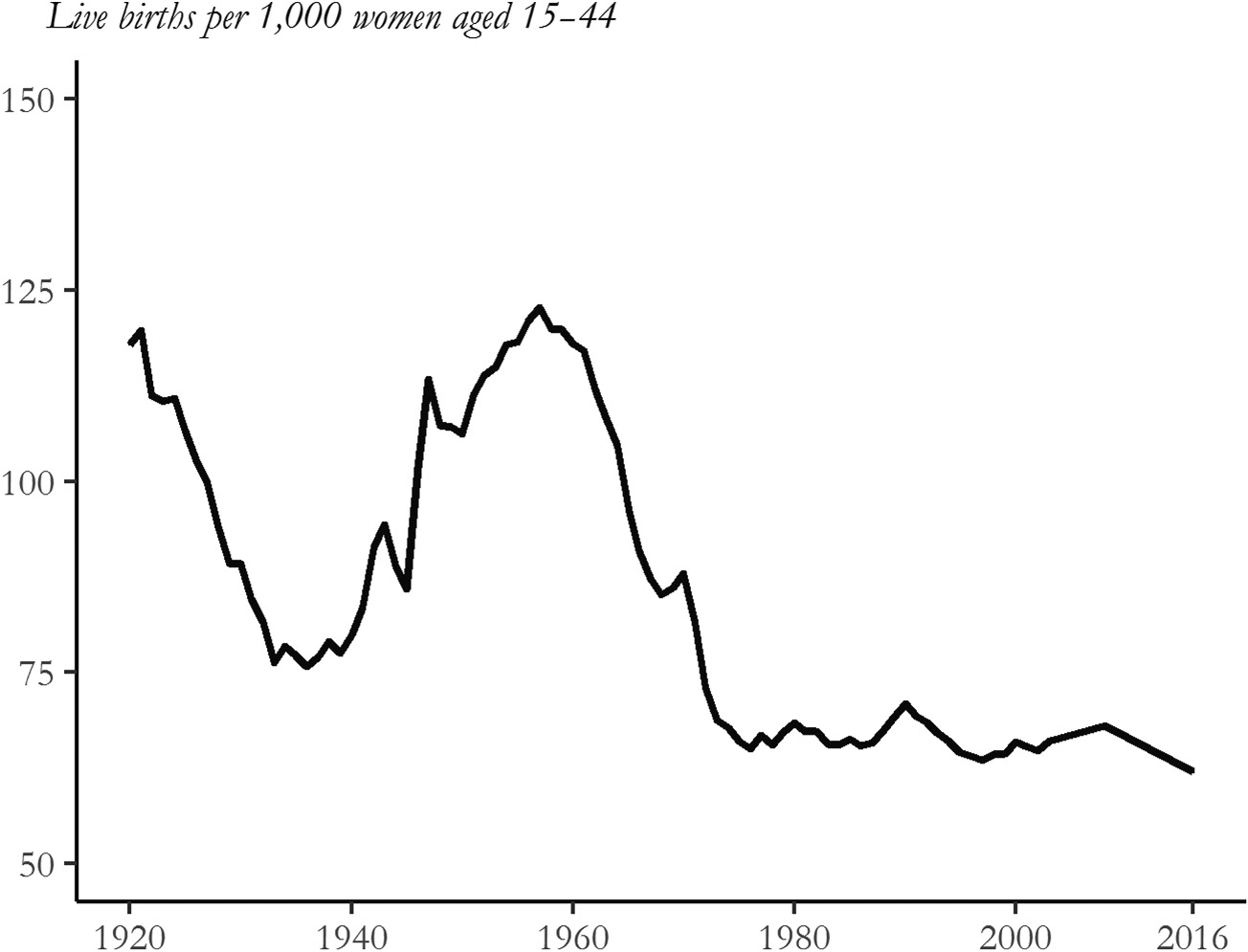

Finally, a combination of economic transformations, shifting social norms, legal changes, and wider access to effective contraception transformed patterns of marriage and childbearing in the United States. The change in the fertility rate (number of children born per 1,000 women aged 15–44) is clearly the most dramatic of the changes we identify; see Figure 1.4.61 The average number of children born to women fell across the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, with a particularly rapid decrease during the Great Depression. Fertility rates famously “boom” after the Second World War, as women had more children and at a younger age. The Baby Boom crested in 1960, as fertility rates fell to levels lower than before the war and then largely stabilized from the mid-1970s onward. All of these shifts in childbearing would have consequences for the opportunities, constraints, and interests of women.

Figure 1.4 Baby boom and bust across the twentieth century (National Center for Health Statistics), 1920–2016

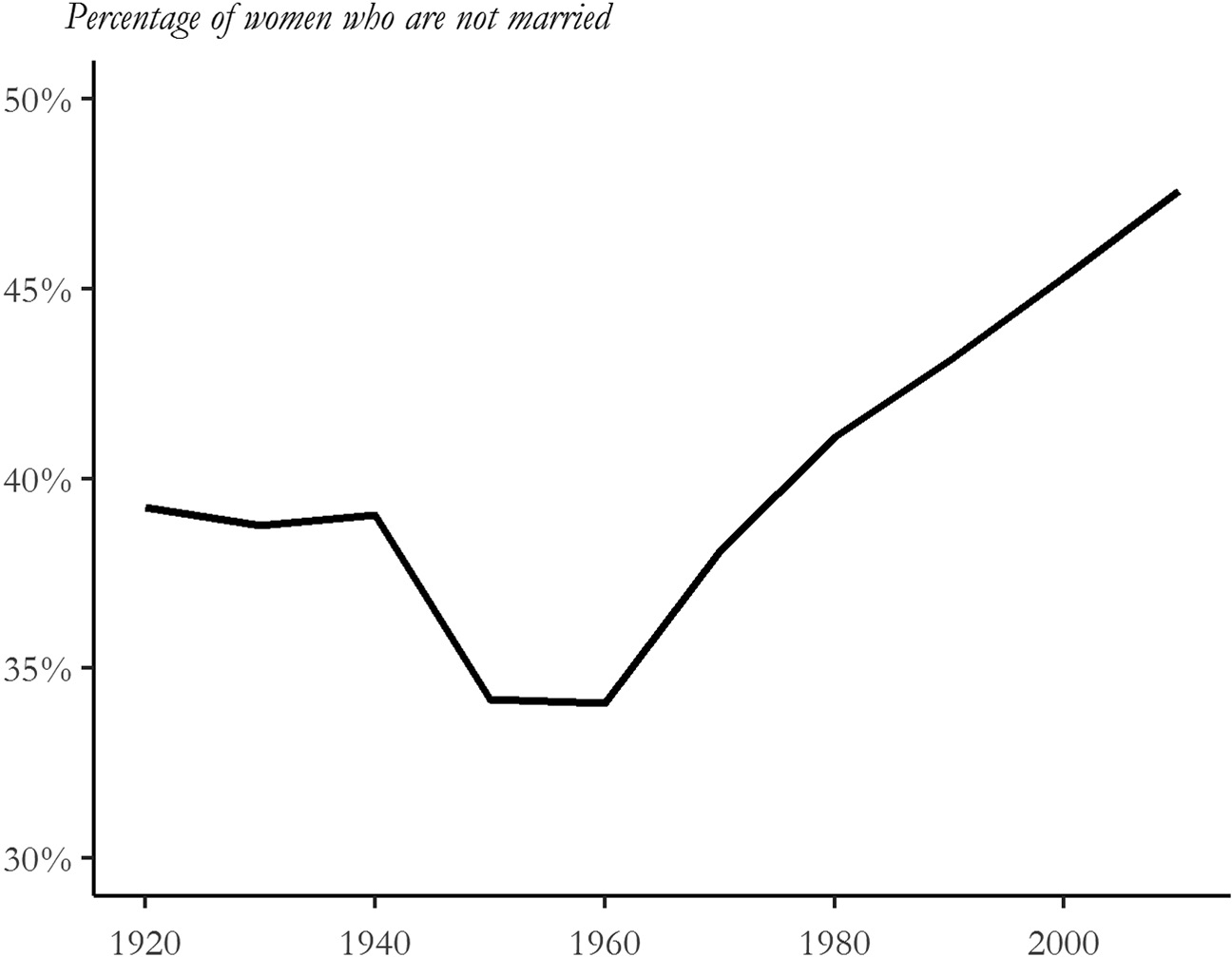

There is a related but distinct pattern for marriage. According to the US Census, the percentage of women over 15 who were unmarried was fairly stable at just under 40% before the Second World War (see Figure 1.5). The postwar period also witnesses a marriage boom as the age of first marriage declines and the percentage of unmarried women plummets. After 1960, however, legal and social changes contribute to rising divorce rates, delayed marriage, and eventually expanding rates of cohabitation. By 2020, fully one-half of women will be unmarried.

Figure 1.5 Fewer women marry in the second half of the twentieth century (US Census), 1920–2016

Women’s Changing Lives

By the twenty-first century, American women were more likely to obtain a higher education, to work outside of the home, to be unmarried, and to have fewer children than at any previous point in American history. The political impacts of these developments are both enormous and contested. Many have highlighted the ways in which these changes have increased women’s independence, power, and control over their own lives. That autonomy, Susan Carroll has argued, permits women to develop and recognize their own, independent, and gendered political interests, as well as the opportunity (due to declining dependence on patriarchal security) to act on those distinct preferences as political actors.62

Others have emphasized how these developments have resulted in a more precarious position for many American women. Due to less opportunity to develop resources (including experience), as well as sex (and race) discrimination, women were more likely to hold less stable and less well-compensated jobs. Increasing marital instability and changing fertility patterns generated more female-headed households dependent solely on women’s income. The “second shift” that most women performed in their own homes created a substantial burden for women, however well-educated or well-compensated.63

Both of these effects – greater autonomy and greater precariousness – are clearly at work in many American women’s lives today. More generally, shifting roles and experiences shaped women’s expectations and perspectives in multiple ways. In the chapters that follow, we explore how these dynamics contributed to how women voters have been understood by candidates and the press, how women have identified and prioritized their own interests, and how women’s political power and influence has shifted.

Women Voters

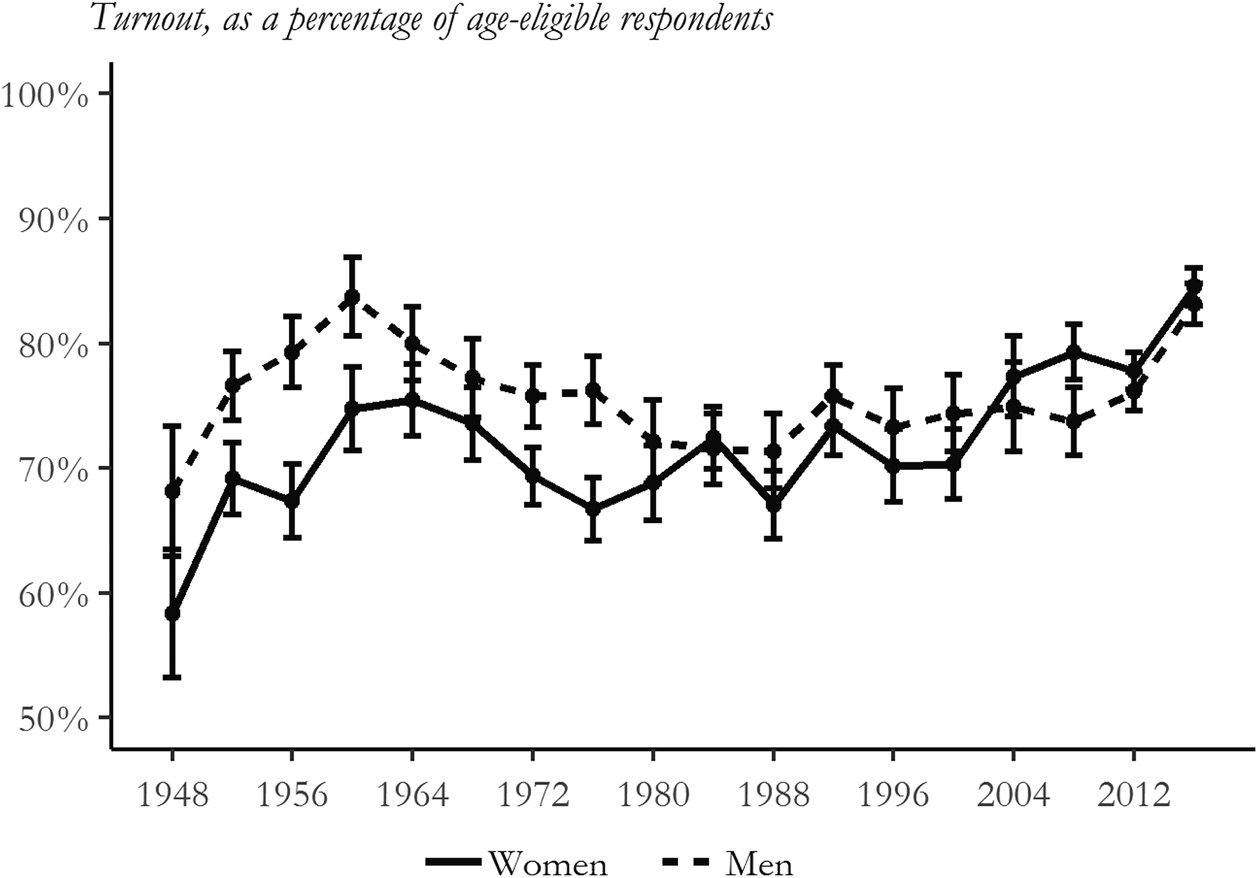

We turn, finally, to reviewing in broad strokes the electoral behavior of women as a whole. In these figures, we use American National Election Studies data (described in Chapter 5) to trace women’s turnout and vote choice from 1948 (when these surveys were first conducted) through 2016. (In the empirical chapters, we use other data to observe women voters in elections before 1948.) Self-reported turnout data in Figure 1.6 show that women’s turnout lagged men’s by an average of over 10 percentage points prior to 1964, but that gap had narrowed to zero by the early 1980s. In recent decades, women are consistently more likely than men to turn out to vote in presidential elections.

Figure 1.6 Women’s turnout initially lags, but eventually exceeds, men’s turnout (ANES), 1948–2016

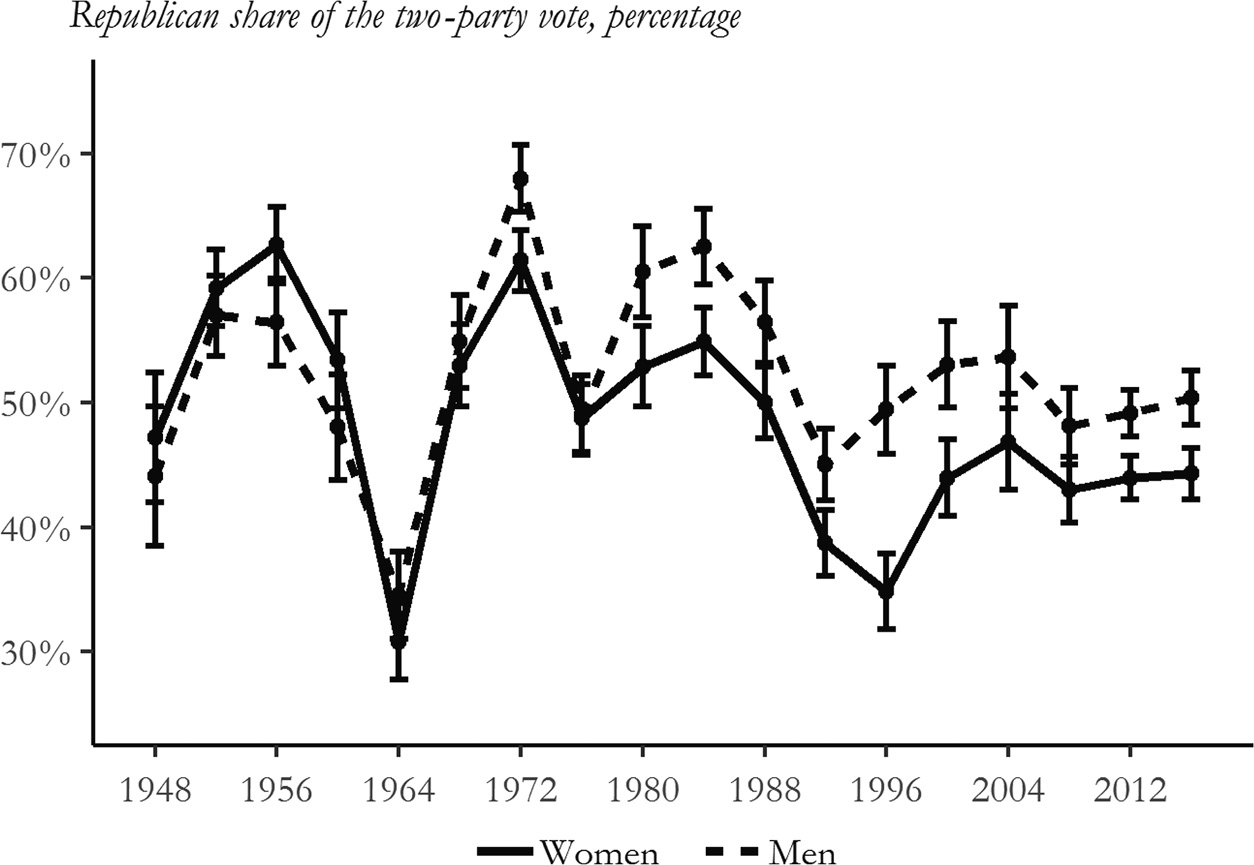

Who women voted for is a more complicated story. The first thing to notice about Figure 1.7 is that women and men overwhelmingly voted the same way. As the parties’ fortunes rose and fell across the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, women and men move in the same direction from election to election. When women swung to Republicans, so did men. When men voted for Democrats, so did women. For all our talk of gender differences, women and men were consistently more similar in their electoral choices than they were different.

Figure 1.7 Women and men vote similarly, but gender gaps emerge after 1980 (ANES), 1948–2016

That said, gender differences are apparent, especially since the 1980 presidential election. Women were more likely than men to vote for the Republican presidential candidate prior to 1964 but differences were small and largely insignificant. This pattern reversed in 1964, but differences remained too small to be meaningful. From 1980 on, men were more likely than women to vote for Republican presidential candidates. In the chapters that follow we delve more deeply into the turnout and vote choice of women and men across these ten decades, putting the electoral behavior of women within the shifting legal, social, and economic context.

Plan of This Book

When Hillary Rodham Clinton accepted the Democratic party’s nomination in 2016, she wore a white pantsuit, consciously invoking the white dresses worn by suffragists more than a century before she became the first female major party nominee for president. Women have cast ballots in presidential elections for more than 100 years because other women both confronted and adapted gender role expectations to fight for women’s right to vote. Since women first entered polling places, popular discourse and social scientific research has sought to understand women voters.

In this book, we trace how women have used their right to vote in presidential elections from 1920 – the first presidential election after the suffrage amendment was ratified – through to the historic presidential election of 2016. In Chapter 2, we provide further context for understanding women voters by examining why women were excluded from the franchise for so long and how women finally won the vote. In Chapter 3 we review and organize major explanations for women’s voting behavior promoted by political observers, politicians, and scholars since suffrage. This discussion informs our discussion of women voters in the chapters which follow.

Chapters 4 to 8 represent the core of this book as we examine how and why women turned out to vote and for which candidates in periods spanning the nearly 100 years since the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. We start with the first women voters, whose entrance into the electorate was shaped by two world wars, the Great Depression, and the most significant partisan realignment in American history. We turn next to the period of the 1940s and 1950s when traditional gender norms and attitudes both shaped women’s voting and the analysis of it. We then trace the shifting electoral behavior of women as a broad set of disruptions – most notably the second wave of the women’s movement – transformed American politics in the late 1960s and 1970s. With the discovery of the gender gap in 1980, female voters attracted unprecedented attention – and scrutiny – from political observers and from the candidates who sought their votes in the decades that followed. Finally, we consider the ways in which women employed their votes at the dawn of a new millennium, as women’s issues and women’s political representation remained as central to politics as ever. We conclude by summarizing the various trends in women’s electoral behavior across the entire century of enfranchisement.

The Nineteenth Amendment transformed the political status of American women. How did women use their hard-won political rights? In the chapters that follow we trace not only the actual behavior of women voters, but how that behavior has been understood within both popular discourse and scholarship.