The Culture of Nationalism

To understand nationalism properly we should see it as more than a political doctrine or social movement. The nation, after which nationalism names itself and which it invokes as its supreme guiding principle, seems to be above politics. It is invoked not as one of those socio-economic or political principles or allegiance patterns that run across society – the way in which stability is invoked by conservatives, free enterprise by liberals, class by socialists, labour by social democrats, or religion by Christian democrats – but as something that transcends those particular interests; the nation is considered to unite rather than divide society. The nation is felt to be politically uncontentious, something to which everyone, regardless of political hue, can feel and express allegiance. Accordingly, nationalism is a shape-shifting, flexible presence in the political landscape; it can hyphenate itself with other political movements of the left, centre, or right, effortlessly adapting itself to the political climate of the decade. It appears as anti-Napoleonism in the 1810s, as anti-absolutism in the 1830s and 1840s, as chauvinistic patriotism in the decades around 1900, and nowadays as a key ingredient in ethnopopulism. The nation can be invoked as vindication by practically any politician – dictators as different as Stalin and Salazar; Italian leaders as different as Mazzini, Mussolini and Berlusconi; and in the post-imperial tradition of Britain and France, political leaders as different as Churchill, Gandhi and Boris Johnson, as De Gaulle, Bourguiba and Le Pen.

In order to get this shifting political force field into focus we need to understand nationalism as the political application of a fundamentally cultural concept. The nation that is invoked as a political ideal is, from the days of Napoleon onward, seen as a community held together by a shared culture and expressing its identity culturally. The nation is as commanding and all-pervasive a presence in the field of cultural production as in those of social and political relations, and its prominent spokespersons are artists and intellectuals as much as politicians or economists. Culture is central to the nation and central to our understanding of nationalism as a historical force.

In this book, I chart not only a history of this culture of nationalism, from Romantic medievalism beginning around 1800 to national-heroic action movies from the 2000s, but also a cultural history of nationalism.1 Culture does not just, as the old-fashioned expression has it, hold up a mirror to society, reflecting political nationalism in the spheres of learning, literature, the arts, and leisure-time amusement. It does all that, but it is in the first instance a blueprint, a scenario, inspiring and articulating agendas and ambitions for the future, disseminating them in alluring forms across platforms and media (prestigious as well as popular ones), and as such it is an active participant in political developments and exercises an autonomous historical agency. In the well-known ‘phase model’ of Miroslav Hroch, which identifies stages in the development of national movements in Europe, the initial stage, ‘Phase A’, is cultural in nature. It does, undeniably, come first (at least within Europe), preparing the subsequent stages of social demands and mass mobilization; and it has left lasting, deep, widespread traces. Europe (and not Europe alone) has been dominated over the past two centuries, and continues to be dominated, by a culture of nationalism. This culture is a generally ambient (‘unpolitical’) repertoire of tropes and references; it frames the way in which we see history and society, past and future. Much as the nation is seen fundamentally as a cultural community, culture itself, in all its manifold fields and expressions, can function as the habitat of nationalism, its conceptual hatching-ground, its rhetorical amplifier and its communicative platform. Culture, in other words, ensures the social presence and the political prevalence of nationalism. It aids the conceptualization as well as the propagation of the idea that nations are natural, timeless entities and that as moral instances they justify the policies that are pursued in their name. Nationalism, in this definition, is a politically influential cultural repertoire; and this book sets out to chart that repertoire and its development since 1800.

The cultural repertoire of nationalism does not in itself explain the course of history, and readers should not expect this book to provide such an explanation. What I attempt, in the following pages, is to explain the repertoire itself; to chart it across cultural fields, across countries and over the decades, in its proliferating and mutating development; to document and disentangle its historical adaptability and its protean, multifarious, ongoing presence.

By now, the word ‘culture’ may begin to sound like a mantra. Sharpening my usage of the term is necessary.

In a bare-bones semantic distinction, culture is everything in human life that is not ‘nature’. In that contradistinction, culture refers to those behavioural or communicative practices by which humans deliberately shape, control, adjust and modify their physical environment and their physiological processes. In this anthropological meaning, culture ranges from agriculture to the building of dikes and dwellings, from clothing and fashion to food preparation and table manners, from the societal regulation of mating and procreation to wedding parties and baby showers, from the grinding of lenses to the manufacture of ink and photocopiers. Culture also involves sharing memories and keeping them alive by means of writing, ritual or the symbolic dedication of spaces; it involves dancing, music and telling stories from nursery rhymes to epic and cinema; it includes the recitation of prayers and debating the international rule of law. Etcetera; this list serves only to give the reader an idea. Of course, not all of this is relevant for our present purposes. Some of this culture is ‘deep’: ancient, widespread and anthropological, such as the domestication of the dog; some of it is rarefied, a by-product of modern Western commercialism and leisure-time entertainment. In the following pages, samples of ‘culture’ will range across that entire spectrum, from ‘deep’ things such as language, cultural memory and narrating the past to classical music concerts, action movies and postage stamps.

Culture is all over the place; how can we save this book from being all over the place? In the following clarifications I will attempt to present a more fine-grained understanding of the ‘culture of nationalism’.

Cultural Production: Artists and Intellectuals

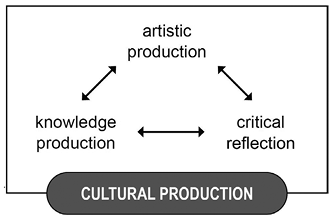

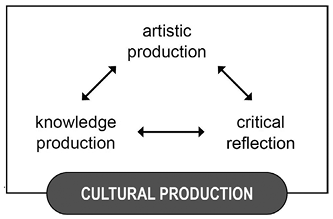

Culture involves not only artistic production and philosophical reflection but also knowledge production. Scholarly and scientific insights may at first sight appear as the systematic explanation of independently existing, objective facts of life – oxidization, gravity or ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. But these discoveries occurred at specific historical moments, were made possible by historically specific circumstances; and whatever wider reverberations they had turned them into specific historical events. In the humanities in particular, scholarly advances dovetail with infrastructural innovations: the exploration of the world and its cultures under colonial auspices; the reinventorization of old archives after 1780; the widening platform of printed books thanks to wood-pulp paper and automated printing presses; the post-1800 restructuring of university faculties and departments. On the timeline of those historical changes, we can map developments in knowledge production (such as the collecting of folk tales and folk ballads and the re-edition and dating of ancient epics), as well as developments in literature and the arts (the rise of the bestseller author and of the historical novel, the national turn in history painting and history writing, the neo-Gothic taste in architecture). In this book I will treat cultural production as the joint operation of artistic production (in aesthetically valorized genres such as the visual arts, fiction/drama and music) and knowledge production (in the world of scholarship), with institutional, socio-political and technological changes functioning as an enabling ambience or context.2

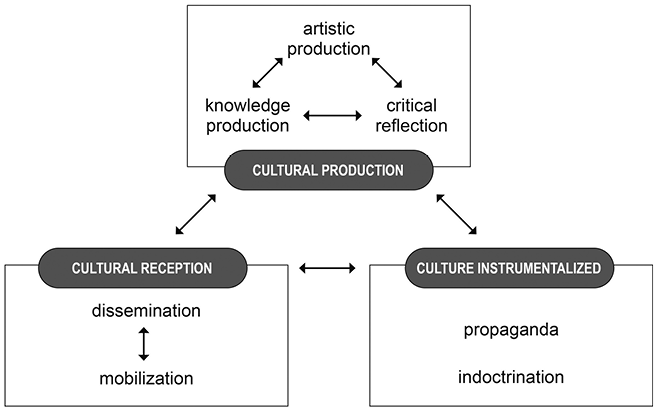

This two-pronged approach to cultural production is complemented by the fact that culture invariably reflects upon itself: literature, the arts and music are pursued in an ambience of literary, artistic and musical criticism, with periodicals and public lectures dedicated to those critical reflections; history writing is accompanied by reviews and by educational discussions about the pedagogical uses of the past. The importance of culture (which frequently means its importance for the nation) is a constant point of reflection among those who are involved in artistic or scholarly production. I therefore schematize cultural activities in a triad of artistic production, knowledge production and critical reflection, as visualized in Figure I.1.

Figure I.1 Cultural production schematized as the interplay of artistic production, knowledge production and critical reflection.

The individuals involved in cultural production are, then, artists and intellectuals. They are the ‘protagonists’, as Miroslav Hroch calls them, of national movements in their early stages of consciousness-building. Their work is what forms the core corpus of this book. Indeed, the texts and artworks produced by these artists and intellectuals are themselves historical actors: they are productive as well as being produced, procreative as well as created – for example ‘La Marseillaise’ and statues of Joan of Arc in France, the Kalevala in Finland and Hendrik Conscience’s novel De Leeuw van Vlaenderen (1838) in Flanders.3

The artists and intellectuals who produced the culture of nationalism cannot really be laid along the measuring tape of ‘elite’ versus ‘popular masses’. The ‘intelligentsia’ (as Hroch calls them elsewhere, those who ‘speak for the nation’) ranged from fretful tutors in private households and bohemian artists starving in garrets to members of the high nobility, urbanites, salonnières and countryfolk, and included country parsons, doctors and schoolmasters who, highly educated, were in close contact with rural-peripheral communities. For them, the nation was, precisely, something that united society across the divides of class and locality thanks to a common heritage and cultural allegiance.4

Dissemination, Canonicity, Remediation

In the history of cultural production and dissemination since 1800, we shall notice a long-term trend towards mass-reproduced media. A new ‘technical reproducibility’ of culture was identified in 1935 by Walter Benjamin (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1963). More generally, the past centuries were characterized by increased quantitative production at decreasing costs, resulting in cheaper availability and greater market penetration. A typical example is the lower price and increased production and availability of printed books after the introduction of woodpulp paper and the mechanized printing press – involving widening circles of readership; or the reproduction of opera arias as sheet music for amateur choirs. For Pierre Bourdieu, these supply-and-demand factors play a crucial role in the symbolic value of cultural products. Culture that is in short supply and involves great expense (such as a ballet performance at Covent Garden, or a rare antique) will be more exclusive and accordingly more highly valorized. Conversely, culture that is readily available to great numbers of people (hence the word ‘popular’) will have less exclusivity or prestige. I will rely on Bourdieu’s distinction between ‘restricted’ and ‘unrestricted’ cultural production when discussing these dynamic shifts: over time, the nation’s identity and self-articulation will come to rely increasingly on ‘popular’ media such as postage stamps, characterized by ‘unrestricted’ production.5

Bourdieu’s criterion is also relevant when tracing the dynamics between ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture. Artists and intellectuals of the Romantic generation draw on folk tales and folksongs, fin-de-siècle design is inspired by popular-traditional crafts; conversely, hitherto prestigious genres such as the historical novel become popular reading for boys, and history paintings end up as engraved or lithographed illustrations in school textbooks. No sooner does one try to apply a distinction between ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture than the entanglement between them becomes obvious. Status and canonicity were, however, important elements for the influence that high-status culture could exercise, and mass popularity was a measure of its social penetration; ignoring such historical factors would be unwise.

We can usefully apply Bourdieu’s notion of prestige here. Some cultural practices play into a societal mechanism whereby elites affirm and perpetuate their higher standing in the social order. Such culture involves, in Bourdieu’s analysis, ‘distinction’; it is prestigious and belongs to what is generally distinguished as ‘high culture’ from the less prestigious ‘popular culture’. High culture is in turn linked to the idea of canonicity. This is at work when a set of cultural expressions or memories are credited with persistently enduring merit or importance, and as such deemed to have a particular pedagogical, society-reaffirming value. As such, high culture is not ephemeral, and even though its social catchment area may be narrow, restricted to the privileged apex of society, its endurance over time renders its importance more considerable than more widespread but ephemeral cultural fashions. The centuries-long cultural presence of the patriotic speeches in Shakespeare’s Henry V are a case in point. Henry V also illustrates another element of canonicity: its capacity for remediation. In Chapter 1, we shall encounter an important instance of how those patriotic speeches were reprised in Lawrence Olivier’s 1944 film version of the play. Canonical works are particularly apt at being adapted into new media as these emerge: certain plays and novels, thanks to their canonicity, are chosen to be reworked into operas, movies, comic strips and musicals, and that adaptability is both a result and a measure of their canonicity. Again, readers will encounter repeated instances in the course of this book.6

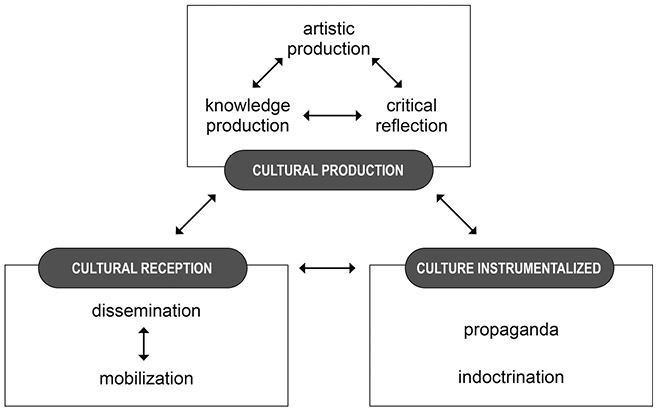

Cultural production is itself only one of at least three ways in which culture makes its presence felt historically. Culture is not only produced, it is also received. People inhabit cities suffused with architectural and monumental markers of history and nationality. People read books (from poetry to collections of folk tales and treatises on myths and archaeology); and they also read book reviews and periodicals dedicated to reviewing and criticism; they go to exhibitions, festivals, concerts and public lectures, and the success of this or that author or work before a more-or-less appreciative audience matters. Successful cultural producers may even convey a direct national-political message to their audiences, as Thomas Davis did in Ireland, ‘La Marseillaise’ in France, Jacob Grimm and Ernst Moritz Arndt in Germany, the Kalevala in Finland, Liszt’s rhapsodies in Hungary, Taras Shevchenko’s verse in Ukraine and Vuk Karadžić’s philological work in Serbia. Ultimately, such work may be instrumentalized by governments for political propaganda and culture may become a tool for national politics. The dynamics of the ‘culture of nationalism’ may accordingly be schematized more fully, as shown in Figure I.2.

Figure I.2 The dynamics of culture in nineteenth-century nationalism.

This schematization visualizes a good many feedback loops between culture as produced in different fields and as received/disseminated in different modalities. Such feedback loops – all elements simultaneously experience influences from others and in turn exercise influences upon them in their nesting mutual relations – are par for the course in a complex system,7 involving things as diverse as a Walter Scott novel, a choral festival in Tallinn in 1897 or in 1989, the unveiling of a commemorative statue of Dante in Florence in 1862, Wagner using the ancient German Nibelungenlied for an operatic German Gesamtkunstwerk, the Norwegian folk tale of Peer Gynt, Frisians commemorating the seventeenth-century poet Gysbert Japikx, Irish activists playing national sports and taking evening classes in the Gaelic language, the restored imperial manor of Goslar being decorated with murals illustrative of German history and the German fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty. All these things (we shall encounter them in the course of this book) hang together, and in their hanging together they establish, both at the international and at the national level, what I here call the culture of nationalism. It is important not to reduce that to a mere glop called ‘culture’ but instead to envisage how intricate such connections and interactions were; and also (for this is a historical study) to examine which ones came first, which ones later: that alone requires a disentanglement of ‘culture’ as a complex system.

The Self-Distinguishing Nation and the Cultivation of Culture

The fact that culture reflects upon itself – is self-aware – is crucial for the type of cultural history attempted here. The mere presence of a certain set of cultural practices (e.g. having domesticated, house-trained dogs, or lighting bonfires on certain occasions) may characterize a society or population without necessarily playing a nation-defining role. I here follow the classic argument of Ernest Renan, in his seminal lecture ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?’ of 1883, that whatever elements play a role in marking and identifying a nation as such can do so only provided the people concerned are ready to acknowledge them as being meaningful. (More on this in Chapter 11.)

What makes culture, or a given cultural practice, meaningful is, precisely, this reflective self-awareness. Owning dogs, or tying one’s shoes with shoelaces, or eating one’s food with fork and knife, or speaking a certain language, can be an unreflected, ingrained habitus, as unconsciously performed as blinking one’s eyes or drawing breath.8 However, the fact that one speaks one language rather than another can, in a confrontational setting, become deliberate, a conscious choice, made for identifiable reasons; and those reasons may have to do with asserting one’s separate identity or maintaining a cultural continuity with previous and future generations. At that moment, language use becomes reflected, conscious, meaningful. So too for other cultural practices. One may wear a kilt merely because it looks cool to show off one’s calves, but it may also be motivated by a self-identification with the specific tradition that it stands for (i.e. its meaning). Singing songs together may be just an assertion of togetherness (‘Happy Birthday’, ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow’), but it can also be much more meaningful, as a symbol of the continuity of togetherness joyfully or respectfully asserted: ‘Previous generations sang the national anthem at their moments of joy, pride or anguish, and as I sing it I am mindful of that fact.’

We can infer at the outset that turning a cultural habit into a conscious cultural choice presupposes that there are alternatives – such as other languages or articles of clothing competing in a given setting, and a sense that the habitual language or dress is no longer the only, default option. In other words, the sense that one’s habitual cultural practices are exposed to, and are competing with, other ones, is a strong motivator for attaching an added, consciously experienced meaning and importance to them. Nationality becomes meaningful once it is exposed to the presence of foreignness – the Fremderfahrung, as Hugo Dyserinck called it. Hence in this book I follow Walker Connor’s definition of the nation as a ‘self-distinguishing culture group’9 – not only as a ‘self-identifying’ group that chooses to identify as a nation, on the basis of whatever shared culture is considered meaningful (the point already made by Renan), but also as a group that performs that self-identification in the process of articulating its distinctness from others.Footnote *

This helps us to sharpen our focus on the types of culture that are meaningful in the nation’s articulation of its distinctness. To begin with, it means that we can no longer invoke ‘culture’ as the generic thing that establishes a national identity. The culture that establishes a national identity is a highly specific and restricted subset of culture: it is culture that is aware of itself and that is consciously experienced as being meaningful for one’s national self-distinguishing.

Such consciously experienced culture is a historical praxis, a choice made in specific, datable circumstances. That alone should alert us that the nation can never be ‘timeless’. Speaking Basque in the town of Guernica was unremarkable in 1800; in the 1950s it was an act of defiance. Culture as such may be of long standing, almost perennial, and difficult to plot on a timeline; but the self-conscious cultivation of culture to enable a national self-distinguishing is a firmly historical process. I shall return to this ambivalent chronology further on.

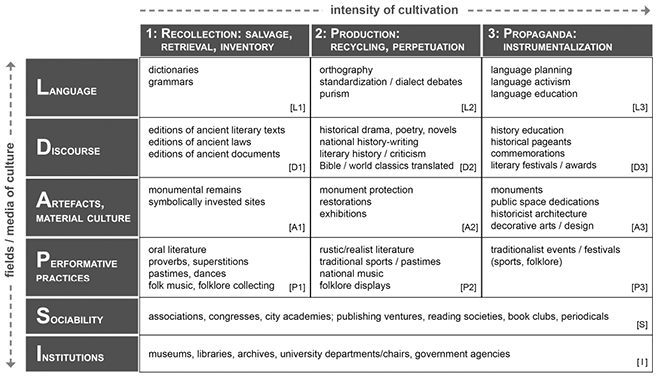

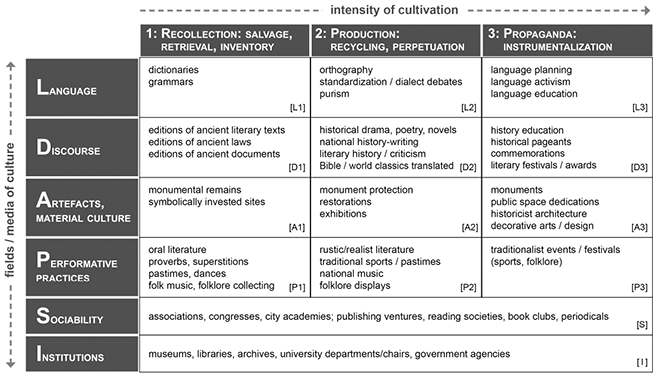

All these considerations make it possible to array a specific set of cultural practices as being meaningful for national self-distinguishing and as operative elements in a ‘culture of nationalism’. We can, empirically and phenomenologically, select from the historical record such cultural practices as were consciously invested with symbolic meaningfulness for national identity; and we can establish, for each of these, the degree of intensity to which they were ‘cultivated’ as such in the political articulation of a national identity. This results in a matrix that I call the ‘cultivation of culture’, shown in Figure I.3. In this matrix, the horizontal rows capture relevant cultural practices as inventorized according to their field or medium of expression (language, texts, material artefacts and performative practices). The vertical columns distinguish three degrees of intensity in cultivation, ranging from mere ‘recollection’ (a salvaging drive to record, inventorize and document culture that is considered to be under pressure or eroding) to downright propaganda instrumentalization, with a middle category for culture produced, recycled and disseminated as being nationally inspired or inspiring.10

Figure I.3 The cultivation of culture in nation-building.

To explain the schema:

The preoccupation with language (top row of Figure I.3) moves from dialectology and linguistics (L1) by way of concerns with orthography, standardization and purism (L2) to the instrumentalization of language as a marker of national identity (L3: activism, language planning and state-planned language education).

The field of textually communicated culture (discourse, second row) embraces artistic and knowledge production. The leftmost ‘Recollection’ column (D1) involves the rediscovery, salvage and printed publication of ancient texts, from epics to laws and ancient charters. Historical novels and dramas, national history writing including literary history, and the field of cultural criticism follow in the middle row (D2). What is also marked here is how many emerging, minoritarian and often newly literate language communities symbolically claim their place in the modern world by translating and appropriating great classical texts (the Bible, Shakespeare, Homer) in their vernacular. On the right (D3) we encounter how nation-building makes use of national history education, the staging of historical pageants and commemorations and the self-celebration of the national literature by means of festivals and awards.

In the third row, material culture (artefacts) is salvaged by archaeologists and in the antiquarian identification of important sites (A1). The protection and restoration of artefacts follows in the next stage (A2), together with the establishment of dedicated national museums. The past is also evoked in history paintings. Such material culture becomes a carrier of national propaganda (A3) when commemorative statues are used to mark public spaces and when public buildings are put up using nationally historicizing architecture, often reinforced by means of decorative arts. Traditional dress is also among the material artefacts gaining national meaningfulness.

Immaterial culture (performative practices) moves, in the fourth row, from folkloristic collections of oral literature and performed traditional music, dances, sports and customs (P1) to their revival as a middle-class pastime and their celebration in rustic literature and rustic genre painting; the composition of national music belongs here as well (P2); and festival culture can turn all of these into mass events with an identity-affirming or propagandistic purpose.

For good measure, the grid also includes two categories that can accommodate initiatives in civil society or government policy enabling a national cultivation of culture: sociability, associational life and journalism; and institutions, museums, libraries and archives.

As a sorting grid, this matrix captures most of the cultural events and practices that I have encountered over the past twenty-five years as meaningful elements in the emergence of national movements across Europe. It is of course highly artificial, like drawing a longitude/latitude grid across the world map: it does not describe the world as it is, but it makes it possible to situate places and trajectories across its varied and irregular surface.

Applying the parameters of the ‘cultivation of culture’ differentiates ‘culture’ into an identifiable set of discrete points where cultural practices intervene in society and in history. That makes it possible to write a cultural history of nationalism – a historical analysis of nationalism that is properly cultural, and a cultural analysis of nationalism that is properly historical.

Culture and the Nation in History

I hope, then, not just to elucidate the development of nationalism by approaching it from a cultural history perspective but also to throw some light on cultural history (the arts, literature, memory and knowledge production) by aligning its developments with the political climate of nationalism. Of course, just as there was a good deal of nationalism outside the realm of culture, there was a great deal of culture outside of nationalism. Many artists and intellectuals were dedicated anti-nationalists: liberal cosmopolitans or internationalist socialists. Many others were conflicted: Heinrich Heine, while deeply, romantically attached to his cherished native country, was repelled by the chauvinistic nationalism of his German contemporaries and satirized them mercilessly. Such voices I find edifying and personally inspiring, but they are not my topic here.

That being said, in focusing on the culture/nationalism overlap I hope to mediate between two tendencies in nationalism studies that have for too long been at loggerheads: traditionalism and modernism.Footnote * For modernists, nationalism is a by-product of the modernization process, and its application to pre-modern societies is considered an anachronism, almost like calling Nebuchadnezzar II anti-Semitic. For traditionalists, it is patently obvious that the societies that developed nationalist aspirations in the nineteenth century did so in continuation of similar aspirations that were operative in those same societies centuries previously and with which they identify by asserting a historical continuity. As in any dilemma properly speaking, both sides, though incompatible, are perfectly correct. And both suffer from blind spots.

Many modernists, concentrated as they are in the fields of historical sociology and social or political history, are reluctant to acknowledge the agency of anything that is not part of the social, economic, technological and political modernization process. From this perspective, the prime mover of history and of social or political movements is the contestation of power distribution, and such things as culture are either shrugged off as mere inconsequential pastimes or rhetorical window-dressing, or else reductively explained away as the mere by-product of ‘underlying’ socio-economic or political power contestations.11

Traditionalists take culture much more seriously but tend to downplay the importance of the modernization process – as if the shift from monarchical systems to popular sovereignty, or scientific progress, or the technological and institutional revolutions of the period 1750–1850, did not really matter. Nor is there much discussion among traditionalists of how modernity affected the production, reception and status of culture, its shift to popular, unrestricted productivity and its cultivation as a nationally meaningful rallying point. While culture is given its proper importance, it tends to be invoked glop-like, as the invariant, transgenerationally maintained lifestyle by which a given society has always maintained its own specific identity. The assertion is frequently encountered that, just because the notion of nationalism had not yet been coined in 1600, that doesn’t mean the thing itself (like gravity or oxidization) was not operative.

That last argument is, by the way, something I wish to dispel. Ideologies are not like physical laws. Women’s suffrage was not really a ‘thing’ under the T’ang dynasty, although gravity and oxidization were: ideologies are society-specific, as is the discourse in which they are articulated and make sense; and in the decades around 1800 (the watershed period or Sattelzeit) European society changed fundamentally, and with it the discourse that made new ideologies, such as nationalism, thinkable and sayable.Footnote *

With that assertion, readers will think, and for good reason, that I have nailed my colours to the mast of modernism. Not quite, though; for I see culture as a separate, autonomous social agent, unlike many modernists who see national movements as wholly socially and politically determined.12

Methodological Nationalism as a Historical Problem

Methodological nationalism can for my present purposes be defined as the uncritical reliance on the contours and catchment of the present-day state as the most meaningful and valid framework for the analysis of historical processes.13 To some extent this involves a tunnel vision whereby phenomena are primarily, if not exclusively, registered as taking place within a given national context (with a concomitant marginalization of transnational and border-straddling phenomena), and the causes for these phenomena are sought primarily within that same national context (with a concomitant marginalization of border-crossing patterns of cause and effect, influence and interaction). Such methodological nationalism threatens social and political historians especially, since the archives they rely on for their work have often been assembled and administered by public authorities and hence foreground in their organization those state-political categories that were in force as these archives were being organized.

That this national compartmentalization needs to be counterbalanced by a comparative, cross-border approach has been obvious for the past decades, with the work of Miroslav Hroch and of Anne-Marie Thiesse standing out as shining examples. To some extent this book can be seen as the extension, by a cultural and intellectual historian, of Hroch’s work as a social historian.14 I was convinced – and I aim to demonstrate in the following pages – that Hroch’s ‘Phase A’ of national-cultural consciousness-raising did not emerge gradually out of older cultural-patriotic traditions. Its emergence was brusque, marked by the coinciding moments of the Romantic revolution and the discovery of Indo-European language relations; and this in itself marks an important historical inflection point. Moreover, as a comparatist I was especially intrigued by the transfers and influences that I saw unfold between different cultural communities within Phase A and as part of the cultural consciousness-raising that persisted even in Phases B and C; and it is here that I found the work of the cultural and literary sociologist Thiesse especially inspiring. Her pioneering analysis of ‘cultural transfers’ between national movements in different countries allowed her to identify a specific – and transnational – agency for intellectuals and for knowledge production, and a set of common concerns. As Thiesse has demonstrated, European nationalism, like European literature, should be studied as a multinational phenomenon from a transnational point of view (as Hugo Dyserinck phrased it).15

The challenge remains that, since the scholar’s working environment (archives, national libraries, university departments) was established by the modern state, our working assumptions may be slanted and determined by the national purview of those states who organized our working field for us. It is still counter-intuitive to see that pre-1815 Danish literature is to a significant extent written in German, or to trace the history of the pre-1830 Low Countries in a continuous shuttle search between Dutch and Belgian archives. One side-effect of this is that the Sattelzeit or watershed around 1800 is also to some extent a filtering threshold in the historian’s own expertise and field of vision (given their familiarity with archives differently ordered pre- and post-1800): traditionalists on the whole tend to neglect the analysis of post-1800 events, while modernists rarely study the pre-1800 centuries as closely as they deserve. This plays into a tendency of both approaches to gravitate towards their own archival bubbles; they look for their lost car keys under the street lamps either on one side of the road or on the other.16

The Nation’s Short History and Long Memory

While the advent of modernity is an indispensable precondition for the development of the nationalist ideology, culture sits uneasily astride the Sattelzeit that marks the acceleration of modernizing process around 1800. The iterative, feedback-looped notion of culture means that certain cultural practices drawn on in the development of nationalist thought (e.g. language and a repertoire of literary texts and historical memories) do indeed date from well before the rise of nationalism by many centuries; but the cultivation of those cultural things, their recycling with the added investment of being meaningful markers of a separate identity, is something that very much part of post-1800 modernity.17 The Nibelungenlied and the Chanson de Roland, as texts, are of medieval vintage; their redissemination and canonization as national German and French classics is strictly a nineteenth-century process.

Given this dual timescale on which the cultivation of culture operates (a modern cultivation of more ancient culture) it may be said that nationalism has a modern, post-1800 history that draws on an old, pre-1800 legacy. It is in this sense that I present the approach taken here as a reconciliation midway between modernist and traditionalist approaches. It is also meant as a way of moving on beyond the ‘invention of tradition’ model. Traditions (authentic, manipulated or faked) are, all of them, sites of memory, lieux de mémoire, and should be analysed in their reception trajectory rather than in the conditions of how they came into being.18 Yes, to be sure, the Romantic century recreated the past in its own image, and in the process produced much that was meant to look authentic but was in fact a latter-day contrivance. To take it at face value would make us fall victim to anachronism. But merely to denounce this way of recreating the past as a mere humbug to hoodwink the credulous public may just be one-upmanship. We must ask ourselves, as with all forms of historicist artistic and knowledge production (fake, misguided or faithfully accurate), what their driving force was, what repertoire they drew on, what purpose they hoped to serve, and how contemporaries (not latter-day historians) reacted to it. Whether accurately documented or falsely imagined, the nation’s collective cultural memory was drawn upon in marshalling the past to inspire contemporary cultural productivity in the arts, literature and learning.19

While accepting anachronism as a fact of life, certainly in the Romantic century, we should nonetheless realize that the ‘short history, long memory’ ambivalence of the cultivation of culture creates one overriding anachronism that has bedevilled our proper understanding of the nation as such, and which, though widely current as ‘a truth universally acknowledged’, should not be exempt from critical inquiry. The culture of nationalism asserts, and is predicated on the a priori supposition, that the nation is ancient, and that it stands as an ancient, transgenerationally enduring presence amidst the turmoil and vicissitudes of unstable states.Footnote * Most modern states evoke in their national symbolism a pretended continuity from ancient, pre-modern (feudal or tribal) polities, and some (Greece, Ireland, Israel) saw or see themselves, quite anachronistically, as ancient, primordial polities newly reconstituted.

As this book will demonstrate, the appropriation of a national antiquity by the modern state is the fundamental, axiomatic basis of nationalism. It denies the extent to which the nation has been imagined or reimagined in recent history, as the outcome of volatile processes of self-distinguishing. In the words of Karl Deutsch (invoking a ‘rueful European saying’), a nation is ‘a group of persons united by a common error about their ancestry and a common dislike of their neighbors’. As such, it is a rather unstable, contentious foundation to base states on.20

The Nation as Contingency: Working Definitions

An interesting attempt to transcend the ambivalence between the nation’s short history and its long memory was made by Anthony Smith with his ‘ethno-symbolist’ approach. For Smith, nationalism was a politically performative mobilization of ethnic identity, and he was, later on in his career, increasingly ready to acknowledge that that ethnic identity was itself (re-)constituted as part of this performative self-articulation. Much valuable research has come out of the ethno-symbolist approach (e.g. John Hutchinson’s study of Irish cultural nationalism); but nonetheless, ethno-symbolism harbours a risk of backsliding into ethnic essentialism and into what Rogers Brubaker has aptly termed ‘groupism’. I take that term to mean that social behaviour (and culture) are seen as a variable output that is produced by an a priori given social group. The group is thus seen as the fixity and as the engendering agent for various social and cultural practices. Brubaker rightly criticizes this one-way line of thinking, pointing out that many groups constitute themselves through – come into being as a result of – the actions they collectively perform or the causes they identify with. Groups can emerge out of ad hoc lifestyle choices such as riding a Harley-Davidson motorcycle; and the historian who studies the history of nations and national self-articulations will notice much the same thing. Whether people collectively self-distinguish as Samogitians or Lithuanians, as Macedonians, Estonians or Walloons, is a historical contingency; ethnogenesis is happening and revising itself all the time. The cause, the act of identification, shapes the group, not vice versa. The same goes for that ‘ethnicity’ at the heart of ethno-symbolism; yet many in the tradition of ethno-symbolism see the ethnie as a social fixity producing culture and are reluctant to see it as a historical contingency culturally produced – as, in Hugo Dyserinck’s words, ‘a mental concept acquiring a transitory actualization in space and time’.21

Avoiding groupism and taking a constructivist approach safeguards us from historical anachronisms and forces us to acknowledge the open-ended variabilities and the never-ending contestations of history. As John Hutchinson has pointed out, the agenda of cultural nationalists was not necessarily ‘state-seeking’; their primary concern was nation-building, that is, the consolidation of national communities as persistent moral-collective entities.22 How this panned out in the course of political history was highly contingent, and even the patterns of self-distinguishing the nation were anything but fixed. The self-identifications that were historically operative in Ulster, Flanders or Savoy at successive moments (say: 1640, 1740, 1840 and 1940) are documented, historical givens, but over time they show radical breaks and shifts. To see behind them, in all their contradictory discontinuity, the agency of a single, persistent group (‘the nation’), identified as such from a present-day vantage point: that is a questionable leap of faith. It is one that is habitually asserted by those who believe in the ideological tenets of nationalism (the belief that behind the vicissitudes of history there is a transhistorically constant agent called the nation), but it is nonetheless an act of faith, an article of belief, a metaphysics of nationalism. As Brubaker put it:

we should not ask ‘what is a nation?’ but rather: how is nationhood as a political and cultural form institutionalized within and among states? How does the nation work as practical category, as classificatory scheme, as cognitive frame? What makes the use of that category by or against states more of less resonant or effective? What makes the nation-evoking, nation-invoking efforts of political entrepreneurs more or less likely to succeed?23

In this book, I trace a history of self-positionings, ideas and repertoires, rather than the history of groups, or nations, or societies in which those ideas and repertoires circulated. I am not even overly bothered by how ‘representative’ those ideas or repertoires were for society at large at any given moment in time; that I leave to social historians. I am more interested in their longevity and adaptability over time: their persistence amidst shifting circumstances. That persistence and adaptability is a measure of the influence of culture – its influence on other, emerging and developing culture, as well as on political institutions – which to me appears at least as relevant as raw mobilizing power. (The distinction between influence and power is something I shall return to in the course of this book.) What I trace is how those ideas and repertoires reproduced themselves, in what media or cultural fields, with what rhetoric or endorsement; how they worked.

On that basis I offer three conceptual definitions on which this books rests.

Nations are the result of collective acts of political self-distinguishing (i.e. a self-identification as being collectively separate from others) performed on the basis of a cultural self-characterization.

Nationalism is a political agenda working towards the social and political recognition of the nation; it is, as such, the political application of a cultural sense of identity.24

The culture of nationalism is the celebration of the nation (defined in its language, history and cultural character) as an inspiring ideal for artistic production and a meaningful category for knowledge production; and the instrumentalization of that cultural productivity in political consciousness-raising.

That last definition echoes, in slightly expanded form, my definition of ‘Romantic nationalism’ in earlier work on the subject.25 In this book, the reader will encounter repeated references to Romanticism and explanations of why it enjoys a privileged relationship with the ideology and culture of nationalism. Nationalism emerged during the Romantic movement, among intellectuals and artists profoundly influenced by it. It accordingly exhibits some hallmarks typical of Romanticism (further explored in Chapter 3): its idealism (the assumption that pragmatic reality is informed by a transcendent world of abstract ideas, national identity being one of these), its reliance on intuitive knowledge, its resistance to disenchantment, its charismatic heroes, and the power of affect and enthusiasm. In nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Europe, cultural nationalism is practically coterminous with Romantic nationalism and what I call its ‘long tail’.

The emergence of Romanticism explains both the starting date and the geographical purview of this book. The starting date is the Sattelzeit, the watershed decades around 1800; the area is Europe, in particular the fault-lines and border zones among the European empires as shaken by the democratic revolutions and the reign of Napoleon. I do take into account the long memories at work that reached back across 1800 into a far deeper past, but I focus on their cultivation in the context of the modernizing nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The time-curve of Romanticism and of Romantic nationalism is like a wave: a fairly sudden onset, relatively precisely datable, cresting to a burgeoning high point that is then followed by a protracted, tapering run-off with occasional eddies and aftermaths. As a result, it is far less easy to be precise about the end-point of my working period. The ‘long tail’ of Romanticism was overlaid by opposing movements (positivism and realism in the nineteenth century, a technocratic and/or anti-lyrical avant-garde modernity in the twentieth); it is also marked by resurging neo-Romantic currents and undercurrents (fin-de-siècle symbolism, 1960s counterculture), finding expression in newly emerging media such as folk museums and epic or rustic-idyllic movies. That ‘long tail’ also characterizes Romantic nationalism; it will be flagged repeatedly in the book’s chapters and specifically in the closing one.

The focus will on the whole be European, since the legacy of Romantic nationalism cannot claim to have general, worldwide (trans-European) applicability; that it became part of a global circulation of ideas and did not leave Japan, India, Persia, or other continents altogether uninvolved, is recognized in principle and gestured at wherever the reminder seemed opportune; but the further exploration of those extra-European dimensions I leave to better qualified scholars. The European working field itself is here defined as it was in the Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe, as the polygon marked out by the metropolitan catchment areas of Reykjavík, Seville, Athens, Tbilisi, Kazan and St Petersburg.26

Outline of the Book

Chapter 1, ‘The Romantic Spell’, begins in medias res and traces the ongoing potency of Romantic historicism in the political imagination of the two World Wars. Two specific legacies of Romanticism are identified: the idea that the nation is a transcendent principle deserving our devotion and loyalty and the paradox that the nation, while commanding our political allegiance, it is itself not political or contentious but, rather, ‘unpolitical’. This twofold legacy explains the title of this book, Charismatic Nations.

Chapter 2, ‘Becoming Something, Unmaking Empires’, gives a background outline of how, between the French Revolution and the Treaty of Versailles, the nation gained force as a constitutional principle in political history, and how nationalism, despite its lack of actual political clout or mobilizing power, was eventually capable of replacing empires with nation-states.

Following this, the cultural history of nationalism is traced in Chapters 3–8, which run more or less parallel across the long nineteenth century. Each addresses one of the cultural fields mapped in Figure I.3 and analyses how it was cultivated in a national sense.

Chapter 3, ‘Romantic Prophets: Inspired Poets Inspiring People’, deals with the poetics of Romanticism and the idea that the transcendent identity of the nation required inspired voices to channel it and to spread its inspiration.

Chapter 4, ‘Manuscripts Found in the Attic’, discusses the rise of historicism: the cultivation of the past and the desire to turn it, and the nation’s ancient roots, into an inspiring contemporary presence.

Chapter 5, ‘Ancestral Voices’, analyses how the Romantic interest in popular and oral traditions deepened into an ethnography of the nation’s mythologies, world-view and fundamental character or Volksgeist.

Chapter 6, ‘Languages, States, Races’, discusses the problematic but ubiquitous attempt to map languages onto language areas and to map states onto those. Much as languages have an uneasy scalar position between dialects and language families, so too states can fission or expand in order to embrace more or less broadly circumscribed language groups. The chapter discusses the logic whereby wider Germanic and Indo-European aggregations make nationalism shade into racism.

Chapter 7, ‘History Related’, deals with narrative representations of the national past. The rise and decline of the Romantic historical novel is discussed, and its lasting impact on cultural memory – which became increasingly divorced from history writing as the latter turned towards academic, archive-based factualism.

The visual imagery of the national past is the topic of Chapter 8, ‘The Image and the Presence’. The heyday of Romantic-academic history painting is traced from its beginnings by way of the Nazarenes to the ubiquitous dominance of the large-scale historical mural. An analysis of the German history murals of Goslar shows how high academicism, paradoxically, morphs into a decorative art form as, towards the end of the nineteenth century, academicism declines and avant-garde movements take over.

Chapter 9 turns to music, not only as a high-Romantic art form experiencing a national inflection (the sample case here being Franz Liszt, who, after an early cosmopolitan life, rediscovered his Hungarian roots and celebrated them in his rhapsodies) but also as a convivial platform for joint performance and rousing patriotic choruses. Choral gatherings and mass concerts become the prototype of participatory festival culture in general.

In many cultural fields and genres, developments across the century marked a shift from what one might call ‘past to peasant’. The medievalism and historicism that marked the Romantic novel and academic painting gave way, or were overlaid by, a greater interest in the contemporary peasantry, in a shift that moved by way of post-Romantic sentimentalism towards something called, both in literature and in the visual arts, ‘realism’. For those wishing to evoke the nation’s essential character, the ‘timeless’ countryfolk, rather than tribal or medieval forebears, were now held up as characteristic and recognizable representative types. Paradoxically, this folkloristic turn took place during a period of accelerated, technology-driven and urbanizing modernity, and a shift towards ‘unrestricted’, commercially driven, mass-appeal cultural media.

That paradox is explored in Chapter 10, ‘People in the Present’, which traces the interaction between the modern city and the timeless country from world’s fairs to the art theatres of the fin-de-siècle. The chapter concludes by outlining how the new modern and decorative arts (Arts and Crafts, art nouveau) functioned as carriers of progressive national revival movements in Europe’s sub-imperial capitals, from Dublin and Barcelona to Prague and Riga; and how their anti-imperial emancipation agenda was uneasily poised between progressive cosmopolitanism and nativist essentialism.

Chapter 11, ‘Culture Mobilized’, covers the same period, the half-century prior to 1914, but this time as a period of increasingly contentious international relations characterized by the developing force of public opinion. Patriotic humanities scholars acquired a new role as public intellectuals, to justify the ways of history to men. The French–German debates over Germany’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 are placed in the time frame of what Wolfgang Schivelbusch has identified as a ‘Culture of Defeat’ – both countries repeatedly experienced the bitterness and rancour of lost wars between 1804 and 1918, with 1871 as a hinge moment for French revanchism and German triumphalism.27 The debates of 1871 are seen as the breeding ground, paradoxically, both of Ernest Renan’s seminal and still authoritative ‘voluntaristic’ theory of national identity and of a type of chauvinistic propaganda that reached almost hysterical levels in 1914. The fervent jingoism of the Great War, fomented and rationalized by learned disquisitions from prestigious academics, marks the zenith of nationalism as a force in European relations.

Chapter 12, ‘The Long Tail’, starts with the universal adoption of the principle of the nation’s right to self-determination,28 which, applied in the Paris peace treaties of 1919, was meant to stabilize international relations and which turned the central tenet of nationalism into a cornerstone of international law. The chapter traces how, in a European continent divided into ethnoculturally defined nation-states, the culture of nationalism continued to be operative. The newly established democracies slid (partly because of an unresolved ambiguity between civic and ethnic definitions of the nation) from parliamentary and constitutional governance towards authoritarianism and dictatorships. Meanwhile, new cultural media emerged, such as cinema. This medium is surveyed to explain the remarkable survival of nationalism across the totalitarian dictatorships and devastating wars of the mid-century, and across the internationalist and anti-totalitarian recoil that dominated the post-1945 decades. It is suggested that this survival, and the renewed contemporary dominance of nationalism as an ideology, is due in large part to its ability to shift back and forth between anodyne and virulent states, latency and salience. The alternation between those states served to proclaim the nation’s charisma both as a merely cultural (unpolitical) feel-good factor and as a political imperative, a commanding, inspiring validator for belligerent heroism.29

Finally, ‘Summing Up’ draws some more general inferences that are relevant for a historical theory of nationalism and national movements. In tracing nationalism across its more antagonistic manifestations and towards populist ‘ethnocracy’, the chapter suggests that the experience of the nation’s charisma could act as a palliative against political and social disenchantment, but may erode the rule of law and derail into national narcissism.Footnote *