Book contents

- Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change

- Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Innovations in Theory and Method

- Part II Innovative Variables in English

- Part III Language Contact Settings

- Afterword

- References

- Index

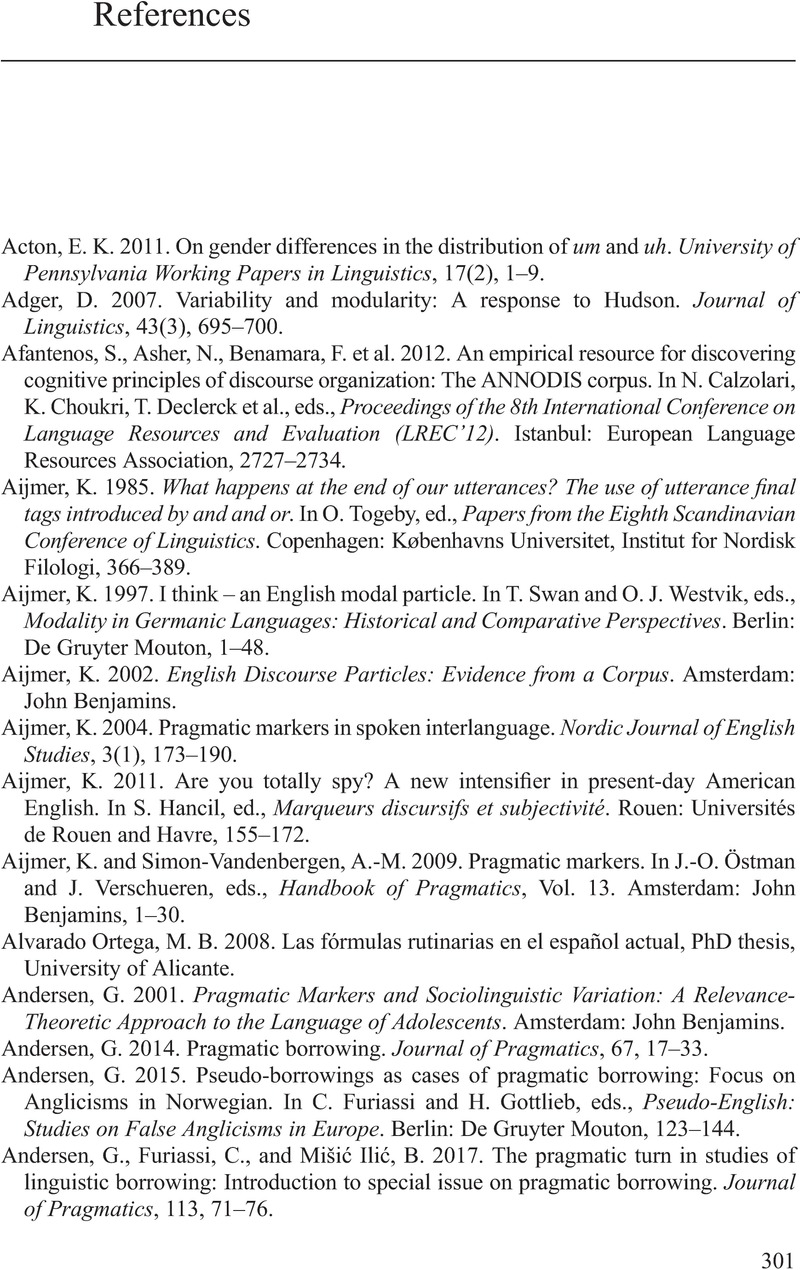

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 July 2022

- Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change

- Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and Change

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Innovations in Theory and Method

- Part II Innovative Variables in English

- Part III Language Contact Settings

- Afterword

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Discourse-Pragmatic Variation and ChangeTheory, Innovations, Contact, pp. 301 - 328Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022