In foreign relations law, the power to wage war is inherently an executive power.Footnote 1 It is the government that declares war or sends the military forces into battle. Yet, increasingly, the prerogative to engage in military action has been open to scrutiny by domestic parliaments. This trend was first noted in 1990, when Lori Damrosch argued that there was a trend ‘towards parliamentary control over the decision to introduce troops into situations of actual or potential hostilities’.Footnote 2 In relation to the Gulf War she noted a ‘striking pattern of parliamentary approvals for decisions to commit military support, including votes in the US Congress, the French Assemblée nationale, and the Parliaments of Italy, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, Greece, Turkey and Spain’.Footnote 3 Similarly, the NATO bombing against the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999 triggered ‘intensive parliamentary deliberations’ in all participating statesFootnote 4 as did the 2003 Iraq invasion.Footnote 5 In relation to both conflicts, the legality of intervention was highly disputed. Since then, the involvement of parliaments around the world has become a fait accompli. The Netherlands Constitution, for example, was revised to require the Government to inform Parliament prior to deployment of forces abroad,Footnote 6 the French Constitution also similarly strengthened the position of Parliament,Footnote 7 whilst other countries changed legislation to define the precise role of the legislature in the context of deployment of armed forces abroad.Footnote 8 In all of these cases, the role of Parliament has been strengthened so that it could provide support or approval for military action and for troops on the ground.Footnote 9 The votes in national parliaments provide legitimacy to the decisions made and give the impression that the Government was held to account by the people’s representatives.Footnote 10 In some cases, for example when national parliaments had effectively vetoed the Government’s plans for military actions, there is even talk of a quasi-sharing of powers between the Executive and the Legislature.Footnote 11

In the context of the United Kingdom, these developments are captured in my recent monograph, Parliament’s Secret War (co-authored with Hayley Hooper).Footnote 12 In the monograph, we contextualise the recent emergence of a constitutional convention, which requires that the House of Commons should have an opportunity to debate an intervention before troops are committed. The Convention, which was adopted in response to the Iraq invasion and recognised by subsequent Governments, has been hailed as historic and is said to represent a real shift in power from the Government to Parliament. In this context, the book makes a strong argument about how international institutions and international law more generally have facilitated this move: on one side, by failing to provide legal bases for interventions on the international level (e.g. Security Council) thus creating a lacuna for national legislatures to step in, and on the other side, by giving parliamentarians the necessary international law terminology on the basis of which they could assess the legality (and legitimacy) of the use of force. The book makes clear that ‘international law’ has influenced domestic parliamentary discourse in several ways.

This chapter presents the empirical evidence to support the arguments made in and serves as a precursor to Parliament’s Secret War. Through discourse analysis, I seek to empirically trace how international law influences domestic parliamentary language. In this regard, I am interested in how members of Parliament understand and explain their role in the context of decisions to use force. I show how by merely looking at the debates in Parliament, one can conclude that after Iraq there has been a change in power-relations between the Government and Parliament. Tracing the terminology used by MPs, I reveal the decline of the term ‘Government’ and the rise of the reference to the ‘House’. This terminology suggests a shift of focus (and perhaps power) from the Government to the House. The chapter maps out how this shift is mirrored in the increased relevance of international law and specifically the question surrounding the legality of the military intervention. It is this question – and particularly the experience of Iraq – that has reshaped the debates in the UK Parliament vis-à-vis the Government. When the legal basis is ambiguous, Parliament reaches for the ‘international law’ toolbox to assert its responsibility. The presence of ‘international’ concerns in parliamentary discourse then fluctuates depending on the clarity of the basis for the intervention. The investigation also reveals that as MPs become more and more involved and informed on issues of war, the deference shown to international institutions and their evaluation of the situation decreases. MPs appear to become more confident in referring to traditional international terms and more competent to make decisions about interventions themselves.

I Who Has Power?

Prior to the Iraq war, the involvement of the House of Commons in debating a potential military intervention was limited. The House was traditionally engaged after the Government made its decision on intervention and more specifically, after the start of hostilities. According to Tony Blair, this tradition required that the Prime Minister make a statement in the House of Commons, followed by a question and answer session or a potential debate. Yet, these debates never ended in a vote, which would explicitly support or reject the military engagement. Instead, a procedural motion of adjournment was called, allowing the Government to preserve face even when seriously criticised.

In 2003, the questions surrounding the legality of the intervention in Iraq without an explicit Security Council Resolution triggered an important debate in the UK as to the role of the Westminster Parliament. In response to previous disputes, such as Suez and Kosovo, in which MPs were denied an opportunity to debate or have a meaningful vote, concerns were raised that ‘The question of whether British troops are committed to action ought to require the dignity of a more meaningful procedure’.Footnote 13 In face of a strong revolt from Labour backbenchers and the resignation of Robin Cook, MPs were – for the first time – given an opportunity to vote prior to the start of hostilities about whether they supported the war or not.

The Iraq example could be an anomaly in an otherwise consistent practice of governments from both sides of the isle which had sidelined Parliament. Yet, the eventual discovery that no nuclear weapons existed, and the clear illegality of the invasion triggered a period of introspection in the UK.Footnote 14 A number of committees and inquiries debated the issue of the appropriate role for Parliament on questions of military action. The reports (aptly called as Taming the Prerogative and Governance of Britain) underlined the need for the Government to be ‘accountable to Parliament for the use of prerogative powers just as for things done under statutory or common law authority’.Footnote 15 The main complaints made against the traditional arrangements were that the Government was usually only ‘accountable after the event’.Footnote 16 This allowed it to take decisions in a vacuum and escape accountability by providing a reason for intervention only when troops were already on the ground. By that point, most of the strategic decisions had already been taken and a step back from military action would be potentially embarrassing and dangerous for the troops. The involvement of Parliament only at this late stage – effectively as a confirmatory organ – greatly demeaned the House of Commons.Footnote 17 In this regard, the 2003 Iraq vote could not be treated only ‘as an act of generosity by the Government for which we had to be grateful at the time’Footnote 18 but had set a precedent for the future.

As a consequence, by 2011 consensus had arisen around the position that ‘any major military action should have explicit parliamentary approval’.Footnote 19 The Government acknowledged this in the Cabinet Manual by recognising a new ‘convention … that before troops were committed the House of Commons should have an opportunity to debate the matter and said that it proposed to observe that convention except when there was an emergency and such action would not be appropriate’.Footnote 20 This recognition of the role of Parliament in sending troops into battle redefines the relationship between the Government and the House of Commons. The convention puts the traditional arrangements under which the Government is the sole source of the deployment power under question and as a consequence, the old arrangements are no longer sufficient. If ‘Parliament should be the source of Government’s power’, this requires a different role for the Commons.Footnote 21 In this context, the timing of its involvement is key – the Commons has to be involved prior to deployment. In this case, the debate and vote can serve to question the Government about its decision and strategy and Parliament can ultimately provide approval for the exercise of the deployment power. The whole issue can ‘be better scrutinised, better thought through, better prepared and the decision would be better made’.Footnote 22

Since the Manual’s publication in 2011, the House of Commons has been given the opportunity to debate military deployments in relation to Syria, against Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and most recently against IS in Syria. Instead of voting on procedural motions, these are now put as substantive questions of support and approval of governmental actions. Today, MPs could argue that the practice of putting the question to the House on a substantive motion has developed into a binding convention, which requires the House’s involvement every time the Government contemplates military action.Footnote 23 Although the timing of this debate and vote is still inconsistent (sometimes prior, other after the fact), the substantive involvement suggests a fundamental shift in the role of Parliament.

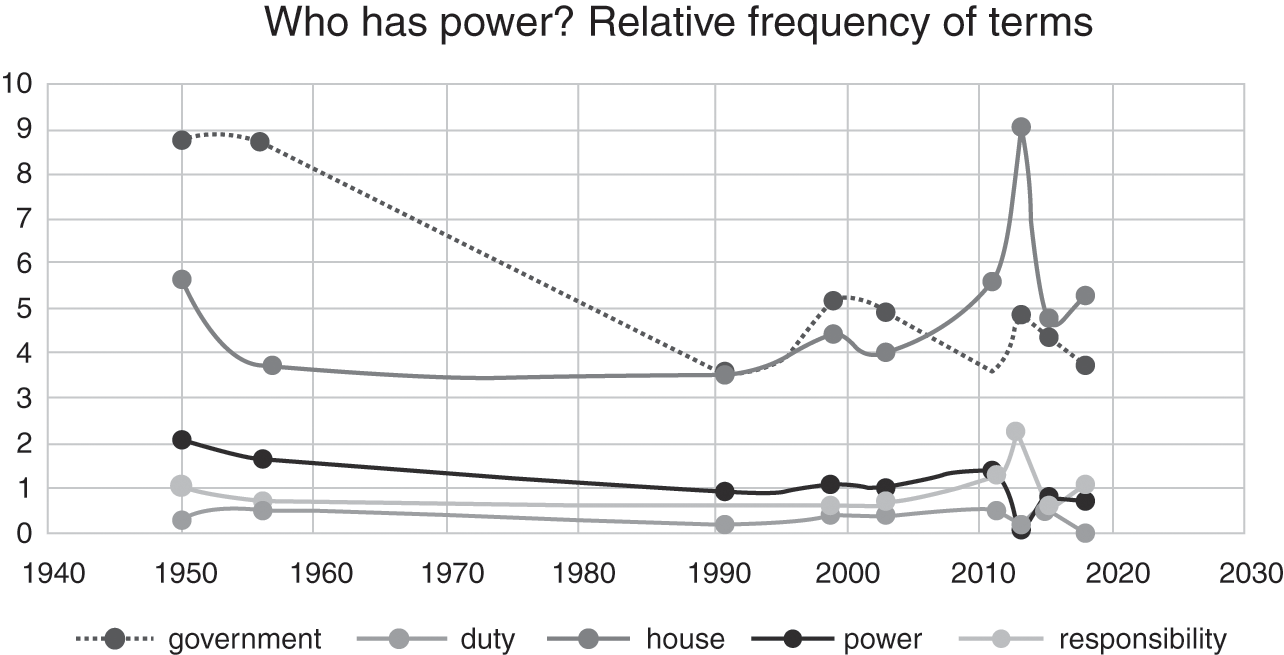

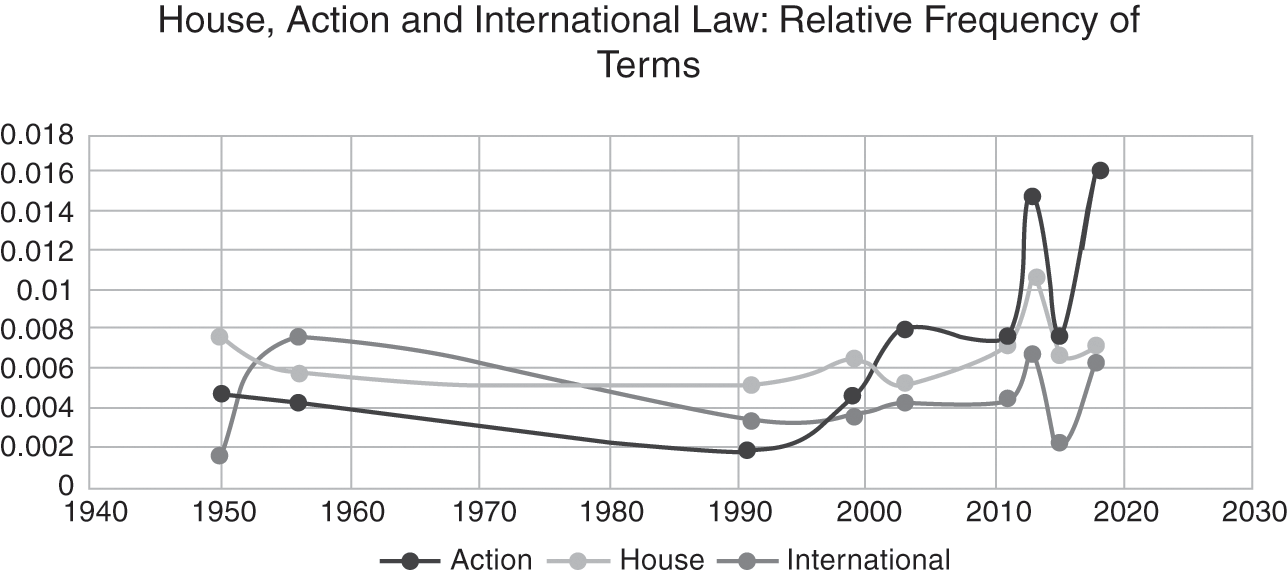

This story of the birth of the constitutional convention and the role and responsibility of the House of Commons in the context of decisions to use force can also be traced in the choice of terminology used by MPs in debates of the House. Nine debates are mapped out on the graph below – from Korea 1950, to Suez 1956, Gulf 1991, Kosovo 1999, Iraq 2003, Libya 2011, Syria 2013, ISIL in Iraq 2015 and Syria 2018.Footnote 24 The picture reveals a clear story of the decrease in the (linguistic) relevance of ‘Government’, eclipsed by an increase in the relevance of ‘the House’. After the experience of Iraq in 2003, the importance of the House of Commons can be visible as a slight bump on the graph. A further and considerable increase in the relevance of the ‘House’ can be seen in the context of the 2013 vote in which MPs vetoed the proposed intervention of the Government in Syria against Assad, a day labelled as a ‘historic night’ and ‘a victory for Parliament’.Footnote 25 After this defeat of the Government’s motion to deploy troops to Syria, commentators even argued that the decision of Prime Minister Cameron to comply with the vote in the House suggests the so-called ‘consultation’ convention has solidified into a binding constitutional convention regulating relationship between two institutions of the constitution and that as a consequence Westminster Parliament had acquired a type of veto-power over decisions on military action.Footnote 26 This, however, appears to have been the peak of Parliament’s power. Since then, subsequent governments (under Theresa May) appear to have taken a step back and the extent of power that Parliament has over these issues remains unclear.Footnote 27 This fluidity is visible on Figure 14.1 as references to ‘the House’ decrease after 2013.

Figure 14.1 Who has power? Relative frequency of terms

The terms ‘House’ and ‘Government’ cannot be seen in isolation from what they require: The growing reference to the ‘House of Commons’, for example, is mirrored by the relevance of the terms such as ‘responsibility’ and ‘duty’ to refer to MPs’ role, as well as the appearance of the terms ‘constitutional convention’,Footnote 28 all of which become more widely used after 2003. For example, although MPs initially had no ‘legal or constitutional right to decide the matters [of military deployment]’, they had a ‘duty to represent the people’.Footnote 29 In contrast, after 2011 MPs insist that ‘the new convention places a responsibility on Members of Parliament to weigh up the arguments and vote according to their conscience’.Footnote 30 ‘Being a Member of Parliament is a great honour, but it carries responsibility: the responsibility for deciding whether one agrees with the Government of the day’.Footnote 31 If before the focus was on helping and supporting Government, now this new responsibility requires parliamentarians to hold the Government to account. If military intervention will be waged with the approval of Parliament, then ‘with deeper engagement comes greater responsibility’,Footnote 32 a responsibility, which MPs cannot abdicate.

The convention therefore not only appears to shift the discourse about the power from the Government to Parliament, it also very clearly changes how MPs perceive their own function.

II The Role of International Law in Domestic Parliamentary Discourse

When the constitutional convention was emerging, the most frequently asserted reason for its birth and recognition was the idea of increasing the accountability of the Government to the House.Footnote 33 The aim was therefore to democratize the prerogative power. Yet, in Parliament’s Secret War, we put forward a different argument – one that questions whether the idea of accountability was the main driving force in the recognition of the convention. Instead, we argue that the consistent failure of the Security Council to act and support military action in certain conflicts, created a ‘lacuna’, which ‘could be filled by domestic legislatures’.Footnote 34 The failure of the international community to provide authorisation for action in the context of Kosovo, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, etc., had prompted subsequent governments to turn inwards and look to their own parliaments to provide legitimacy for their action. The developments on the international sphere have therefore triggered a ‘domestication’ of decision-making.Footnote 35 In the UK, this has placed Westminster Parliament centre stage and has made MPs primary decision-makers on decisions to use force.Footnote 36

The shift of decision-making from the international sphere to the domestic, however, ‘has not resulted in a more domestically focused discourse. Instead, the discussions in the House have focused precisely on those questions which the international community should have resolved – questions of the legality of the use of force’.Footnote 37 In many ways, Westminster Parliament appears to be carrying out similar functions as the Security Council – for example, testing whether there is enough basis to support military action proposed by their Government.

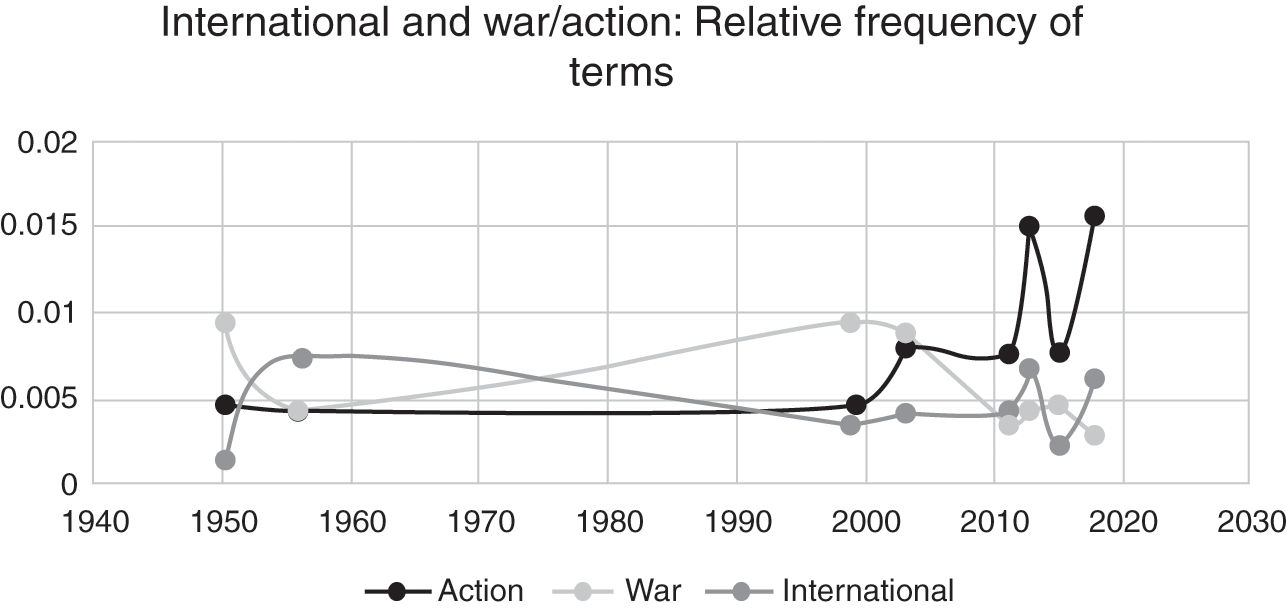

This can be clearly seen in the graph below.Footnote 38 Looking at the different disputes of the last seventy years, it is clear that those which have a clear international authorisation (Gulf War and Korea),Footnote 39 raise little if any concerns about international law. For example, in relation to Korea, MPs talk about the ‘authority of international law’ and the need for Britain to ‘act up to [its] supreme international obligations’.Footnote 40 In these cases, the additional support and legitimacy that a national parliament could provide to an already authorised international action is minimal and MPs therefore appear not to be too concerned or worried about international norms. References to ‘international’ law are minimal.Footnote 41

In contrast, the peaks of debate about international law can be seen clearly (on Figure 14.2) in cases where the international basis for the intervention is unclear or ambiguous: after Iraq 2003, most references to international law are made in the context of the 2013 Syria debate and in 2018. However, the most visible peak of concern about ‘international’ legality of military action can be seen in relation to the 1956 Suez crisis, in which Britain helped Israel and France in the nationalization of the Suez Canal. The action was condemned by the international community, but the Security Council failed to condemn the nationalisation due to France and Britain’s veto.Footnote 42 In the Suez debate, which followed in the House, there were 302 references to ‘international’ law. Later, in 2003, Iraq generated 98 references.

Figure 14.2 International and war/action: relative frequency of terms

Developments on the international level have therefore created space for domestic parliaments, but they have also – at least indirectly – imposed a responsibility on MPs to not allow themselves to be used strategically in a manner that enables the Government to fill the void at international law level. As the Constitutional Committee in its Waging War Report found:

Given the absence of legal restraint on the deployment power under domestic law, the rules of international law on the use of force take on an enhanced significance as the only apparent limitation on the prerogative. Domestic legality does not pre-empt international law. In other words, action, which may not be unlawful under domestic law, could be in violation of international law.Footnote 43

In fact, looking closely at debates, international law appears to provide MPs with the framework and language with which they can carry out their functions. In Suez, for example, MPs underlined that the UK as a member of the United Nations had ‘steadfastly avoided any international action which would be in breach of international law or, indeed, contrary to the public opinion of the world. We must not, therefore, allow ourselves to get into a position where we might be denounced in the Security Council as aggressors, or where the majority of the Assembly were against us.’Footnote 44 Others equally recognized what was at stake: ‘are we to live under a regime of international anarchy or international law? … We all recognise that [the Charter] has its limitations. … But nevertheless it has sufficient authority for one to say that no action that we take … should be in derogation of the Charter, much less in contradiction of it’.Footnote 45

In Iraq, when debating potential military action, MPs objected that ‘The action against Iraq is, I believe, pre-emptive, and therefore demands even greater international support and consensus than other sorts of intervention. We do not have it. Such isolation entails a genuine cost and danger. It undermines the legitimacy that we must maintain to tackle the many threats to global security’.Footnote 46

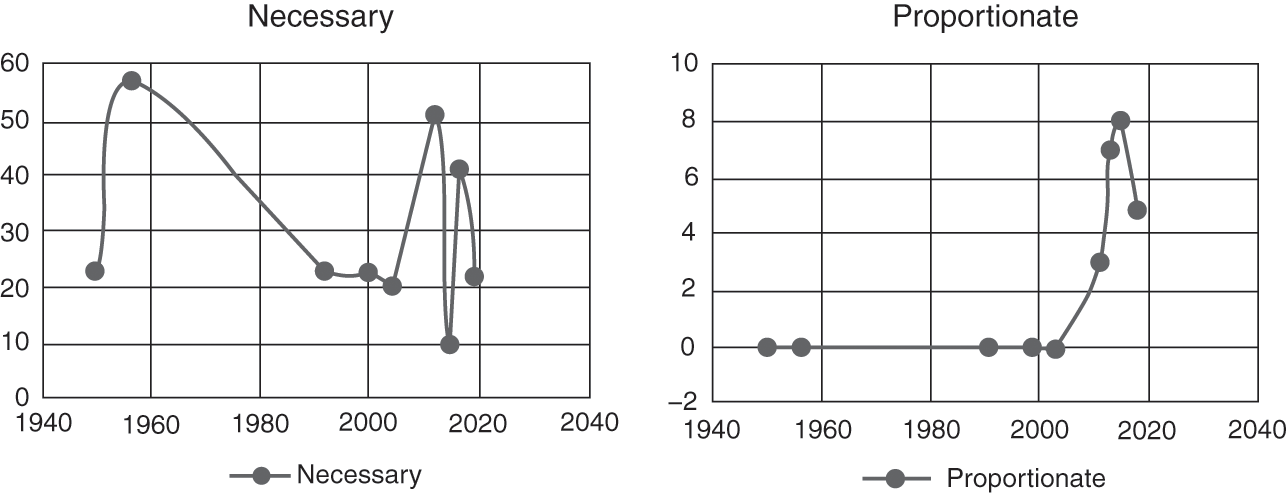

These concerns run through the debates that seek to fill the void left by unauthorised, unilateral military interventions. In fact, MPs appear to have internalised international concerns about the legality of the proposed action and worry about how they will be perceived by the international community.Footnote 47 For this reason, when the Government makes its case to MPs, it does so in a similar manner as it would before the United Nations – by referring to the Charter and presenting the intervention as ‘necessary’ and ‘proportionate’. In turn, MPs – in effect invited to step into the shoes of the Security Council and support the use of force – pick up on this international language of ‘necessity’ and ‘proportionality’ and use the same terminology to assess and evaluate the legitimacy of the proposed military intervention. The graphs below show clearly how in the debates of the Commons the use of the terms ‘necessary’ and ‘proportionate’ – to refer to the appropriate extent and scope of the use of force – have skyrocketed since the Iraq War.Footnote 48 Before 2004, MPs barely made use of this terminology to discuss the use of military action (bar the blatant exception of Suez). Even in relation to the Falklands Islands, where the intervention was defined as one of self-defence, the necessity and proportionality were not high on the agenda. After 2004, both terms ‘necessary’ and ‘proportionate’ feature prominently as seen in Figure 14.3 (e.g. in the context of debates concerning Libya 2011 – ‘necessary’, Syria 2013 – ‘proportionate’, Syria 2015 – both).

Figure 14.3 Use of terms ‘necessary’ and ‘proportionate’

The graphs in this section portray the lessons from Iraq clearly: since 2004, MPs regularly require that the Government seek a legal opinion about potential military action and make a clear case as to the legality of the intervention.Footnote 49 But their expectations do not stop there – an assessment of proportionality of the action is also expected and MPs themselves will query this element of the intervention throughout the debate. The ‘proportionality’ graph shows beautifully how before 2003, no assessment of proportionality took place in the Commons. Since then, however, MPs are not only informed about what international law requires but also concerned that the country complies with its requirements.

It is clear from what has been said that whilst international concerns have always been at the heart of debates in Parliament (partly due to the international nature of war), with the birth of the War Powers Convention after 2003, interest in international law has steadily increased, driven by the need for accountability. This need was more pronounced in situations where military intervention had no clear authorisation from the Security Council, that is, in the case of Syria 2013 and airstrikes in Syria in 2018. The graph below shows clearly how the enhanced involvement of the ‘House’ (and the power associated with it) and the need to hold the Executive to account for the proposed ‘action’ directly correlates with the House’s attention to ‘international’ concerns. Since 2003, when the Pandora’s box for enhanced parliamentary involvement was opened, the three lines (and seen on Figure 14.4) appear to move almost in parallel. The strong link between the ‘international’ and the power and relevance of the ‘House’ is therefore clear.

Figure 14.4 House, action and international law: relative frequency of terms

III The Implications for International Law

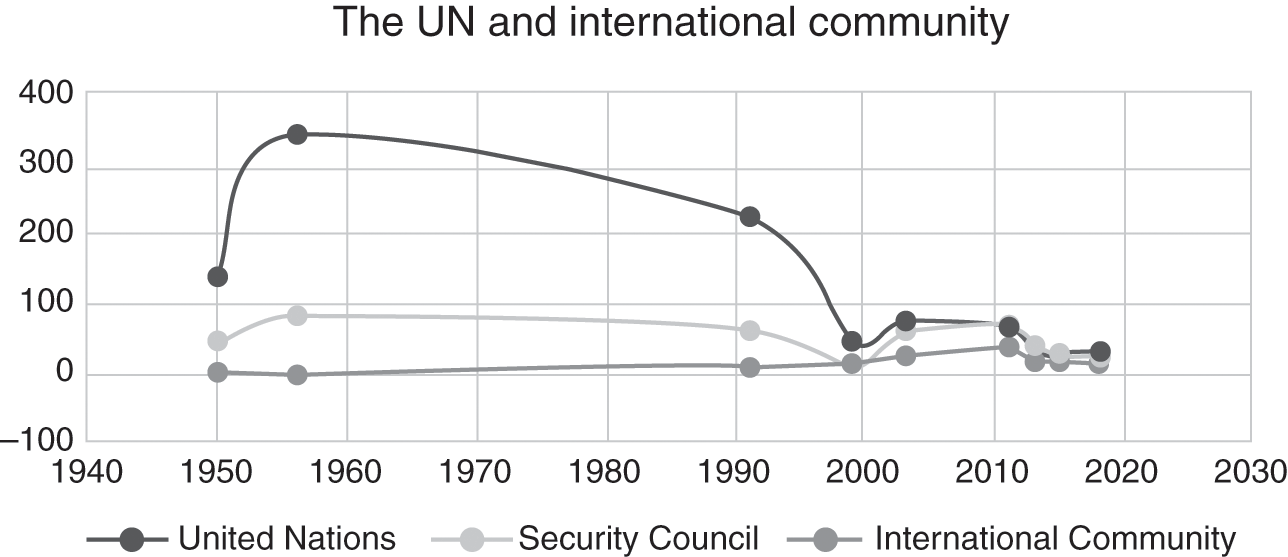

Governments have turned to domestic parliaments strategically, inviting them to fill the lacuna left by the international community (e.g. Security Council). MPs appear to have accepted this challenge and have become increasingly more confident and more competent to discuss the use of military action in terms usually preserved for the Security Council. The question however arises as to whether the new role of the Commons has – at least internally – increased or decreased the relevance of the United Nations and the Security Council. And what does Westminster Parliament’s decision to act instead of the Security Council mean for the international community and for international law?

From the view of debates in Parliament, it is clear that references to the ‘United Nations’ have importantly decreased. If in Korea, Suez and during the Gulf war, the United Nations was in the forefront of MPs minds, this is no longer the case. Since 2011, when the War Powers Convention was officially recognised and the position of the Commons solidified in relation to decisions to use force, these references have fallen even further. A similar trend can be seen in relation to the ‘Security Council’. Whilst references to the Council have remained steady throughout the sixty years, since 2011 there has been a steep drop in their appearance in debates in the House (as seen in Figure 14.5). It is this drop which is perhaps the most remarkable: once the issue of the use of military action is ‘domesticated’ through the War Powers Convention, references to the UN, the Security Council and even the ‘international community’ become so rare that regardless of whether the use of force is authorised or not, these external bodies/audiences appear to become less relevant in the domestic debate.Footnote 50 As the position of the Commons to have a say on the matter is solidified and MPs become more involved and informed on issues of war, the deference shown to international institutions and their evaluation of the situation decreases.

Figure 14.5 The UN and international community

This is confirmed by the most recent 2019 report of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, which investigates the role of Westminster Parliament in debates to authorise the use of military force. The aim of the report is to explore the scope of the War Powers Convention and the role of Parliament vis-à-vis the Government after the Iraq, Libya and Syria 2013, 2015 and 2018 experiences. Although the report mentions the UN Charter (once and in footnotes!), it does not refer to the United Nations, the Security Council or the international community.Footnote 51 Even more, the term ‘international law’ does not appear in the report.Footnote 52 The document is therefore clearly concerned to situate Parliament in the domestic sphere, rather than define its role vis-à-vis international institutions or the international community. In the domestic sphere, Parliament can claim to have a say in authorising military action, or as some commentators asserted even a ‘de facto veto power’,Footnote 53 but its role – which emerged due to a lacuna created by the international community – does not remain inextricably linked to the international sphere. Although international terminology may be used by Parliament to assess the legal basis for an intervention, international actors do not appear to feature in Hansard debates.

The shift of decision-making from the international sphere to the domestic has important implications for international law. The sidelining of international institutions not only as fora of decision-making but as fora with expertise in international law signposts a move towards unilateralism and isolationism.Footnote 54 As Murray and O’Donoghue put it:

We challenge the underlying assumption that Parliament’s interventions mark an indisputably positive development in constraining the use of force. When coupled with the focus upon the doctrine of humanitarian intervention which has accompanied many controversial exercises of UK military force since the end of the Cold War, the involvement of Parliament in the decision-making process risks hollowing out UN Charter safeguards. … Relying upon domestic assemblies to provide the sole necessary authorization point for certain uses of force might appear to offer a means to unblock international institutional processes – but this course turns away from international constraints upon the use of force and opens the door to new forms of unilateralism.Footnote 55

Murray and O’Donoghue for example show that in the domestic legislatures claims to self-defence have been stretched far beyond what international law envisages, to include collective self-defence in relation to Afghanistan, situations of pre-emptive self-defence, and targeted killings.Footnote 56 Similarly, Parliament’s Secret War maps out how multiple legal bases are being used by the Government before UK Parliament to make claims about the legality of military action, even though international law excludes accumulation of such arguments (e.g. self-defence versus authorised action).Footnote 57 Both of these practices ‘complicate the question of whether a use of force complies with international law’.Footnote 58 On international level, such claims would not be (or indeed are not successful) since the UK cannot control action of other States, yet domestically they succeed because the legislature is ‘more susceptible to executive influence’.Footnote 59 This is especially true in the UK, where due to the fusion of power between Government and Parliament and the control the former enjoys in the Commons, its decisions are regularly upheld by the House.Footnote 60

Ultimately, the victim of the process of ‘domesticating decisions on military action has been international law, and in particular the UN Charter. By acting instead of the UN and by using international law language, governments have sought to sideline the international community and invited parliamentarians to aid them in redefining what is legally permissible’.Footnote 61 These examples have contributed to the development of customary international law on the use of force, which lives in parallel to and competes with the UN Charter. In this regard, as Hans Blix has commented, national governments – supported by their own legislatures – have become ‘global policemen’, acting without or even contrary to UN mandate, writing their own rules for the use of force.Footnote 62 Such unilateralism undermines the original basic tenets of the Charter, undermines the international institutions that are responsible for its enforcement, and ultimately leads to fragmentation of international law.

IV Conclusion

This chapter traces the influence of international law on the birth of the consultation convention, which has allowed the UK Parliament to be increasingly involved on questions of war. Through discourse analysis, it shows how the way in which members of Parliament understand and explain their role in the context of decisions to use force changed, especially after Iraq. Tracing the terminology used by MPs, I reveal the decline of the term ‘Government’ and the rise of the reference to the ‘House’. MPs speak of their own ‘duty’ and ‘responsibility’ to weigh up arguments on the use of force and hold the Government to account. This shift in terminology is mirrored in the increased relevance of international law and specifically the question surrounding the legality of the military intervention. The presence of ‘international’ concerns in parliamentary discourse fluctuates depending on the clarity of the basis for the intervention. When the legal basis is ambiguous, Parliament reaches for the ‘international law’ terms like ‘necessity’ and ‘proportionality’ to assert its responsibility and hold the Government to account. The importance of international law, however, is not limited to the ‘borrowing’ of the international law toolbox. Indeed, the failure of international institutions to provide legal bases for interventions in cases like Kosovo, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, has created room for national parliaments to be involved on these questions in the first place. But as questions on the use of force are ‘brought home’ and ‘domesticated’, this has not led to a reinforced relevance of the international community or its institutions. The investigation for example reveals that as MPs become more informed and confident to discuss issues of war, the deference shown to international institutions and their evaluation of the situation decreases. References to the ‘United Nations’ and the ‘Security Council’ disappear from Hansard debates. Even more, the Government is able to persuade MPs about the legality of the use of force in ways that would not be acceptable at international level. These examples show how increasingly international law is being developed at domestic level independently of international institutions and often unilaterally, by Governments acting only through and with the support of their own parliaments. Gradually, from conflict to conflict, such unilateral action is contributing to the development of customary international law on the use of force, which competes and potentially contradicts with arrangements under the UN Charter. Although hailed as a historic step in the direction of heightened accountability, the recent empowerment of domestic parliaments on issues of the use of force counterintuitively suggests that the future of the international law on the use of force appears to be ‘domestic’.