Chapter 3 examines how Ethiopian state formation resulted in a particular state structure, which afforded both opportunities and challenges to the EPRDF when it seized power in 1991. The analysis briefly examines the history of the state over the past 2,000 years, particularly focusing on the period since 1855, which is widely regarded as the beginning of the modernisation of the Ethiopian state, and the revolution of the 1970s. This history has already been the subject of extensive debate in the literature. As such, the chapter provides a brief synthesis of key issues relevant to the book’s analytical focus, rather than attempting complete coverage of this long and complex history.Footnote 1

This analysis makes two main contributions to understanding the EPRDF and its project of state-led development, both of which tend to be downplayed or neglected in the existing literature. The first is to show that long-run state formation and the revolutionary changes of the 1970s forged many features of the Ethiopian state – such as a high degree of state autonomy and a relatively high state capacity – that subsequently enabled the EPRDF’s state-led development project, even if these state structures were not initially utilised for developmental purposes under the Derg. More problematically however, Imperial state-building and the revolutionary period also resulted in an extremely linguistically and culturally diverse population, which was increasingly politicised along ethno-nationalist lines. Second, the chapter emphasises the EPRDF’s origins in the revolutionary events of the 1970s and examines how this history shaped the party. The Emperor’s overthrow in 1974 resulted in competition for political dominance between multiple revolutionary movements, including one that was overtaken by the military in urban areas and a range of ethno-nationalist insurgencies that started in rural areas and sought to fight their way to the centre. These revolutionary origins shaped the EPRDF’s political strategy for gaining and maintaining power, and the structure of the party itself, as it transitioned from an ethno-nationalist movement to a national government.

The chapter begins by providing an overview of the origins of the Ethiopian state before focusing on the period of state-building and territorial expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century under the threat of European colonialism. The analysis then turns to Emperor Haile Selassie’s attempt to centralise power and transform the Ethiopian state in the twentieth century, followed by the revolutionary processes unleashed by the failings of this attempted modernisation. The remainder of the chapter considers the competing revolutionary projects carried out by the Derg and the ultimately victorious Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), highlighting the legacies of the revolution in terms of the structure of the state, nation-building and state–society relations.

The Origins of the Ethiopian State

The roots of the Ethiopian state can be traced at least as far back as the Aksumite civilisation in contemporary Tigray and Eritrea in the first century AD. Though a detailed discussion of this long history lies outside the scope of the book, a brief summary provides essential context for subsequent analysis, particularly regarding the centrality of land to political power, the limits of state infrastructural power and the complex origins of Ethiopia’s ethno-linguistic diversity.

For many observers, a key factor distinguishing Ethiopia from most of Africa was the early adoption of the ox-drawn plough that underpinned an agrarian social hierarchy (Goody Reference Goody1971, Tareke Reference Tareke1991, McCann Reference McCann1995, Crummey Reference Crummey2000). Moreover, following King Ezana’s conversion to Christianity in the fourth century, the link to the Coptic Church in Alexandria was key to legitimising state power (Erlich Reference Erlich2002). Aksum was succeeded by kingdoms to the south, first the Zagwe kingdom and, from 1270, the restoration of kings claiming descent from the mythical tenth century BC King Menelik I, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. A consistent challenge to the exercise of authority was contestation between the Emperor’s attempts to centralise power and centrifugal pressures of the nobility (Ellis Reference Ellis1976, Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). The Imperial state’s infrastructural power was constrained by limited technology, and the mountainous territory that is divided in many places by deep ravines and rivers that were all but impassable in the rainy season. Consequently, the Emperor relied on the nobility and church to maintain local order. Vital to this relationship was the Emperor’s power to allocate gult, or fiefs to members of the nobility and the church (Crummey Reference Crummey2000). Gult-holders had the right to demand tax, tribute and labour from tribute-paying peasants (gebbar) in a particular territory in exchange for keeping the peace, dispensing justice and providing military support to the emperor. Gult rights were overlaid on diverse land tenure regimes of which the most common was rist. Under rist, peasant farmers held rights to a share of community land through descent from a common ancestor along male and female lines.Footnote 2 The allocation of gult rights was therefore the central means of sustaining the power of a mediated state comprising the Emperor, the landed nobility and the church.

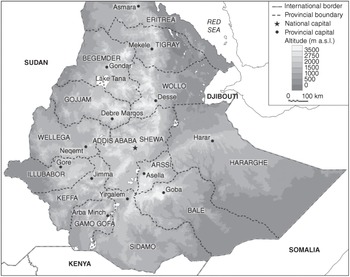

The empire gradually expanded its territory up to the early sixteenth century into the western highlands and as far south as parts of Bale (see Figure 3.1), while trade networks extended into areas beyond Imperial control (Tareke Reference Tareke1991, Crummey Reference Crummey2000). In doing so, this expansion brought the Christian kingdom into contact with other societies, including the Muslim Adal Sultanate based in Harar, and Oromo populations to the south (Hassen Reference Hassen2015). The result was contestation over territory over an extended period and, from the early sixteenth century, the reversal of the Christian kingdom’s expansion. The first major challenge was presented by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim, commonly known as Ahmad Gragn, of the Adal Sultanate who conquered most of the Christian Empire from 1529. While Ahmad was eventually defeated with Portuguese support in 1543, the Christian empire was severely weakened, contributing to a major expansion of the Oromo from Bale and Sidamo from the early sixteenth century (Zewde Reference Zewde1991). Through a combination of migration and assimilation of non-Oromo groups, Oromo populations established themselves as far north as Wello and Tigray, and as far west as Wellega (Crummey Reference Crummey2000, Hassen Reference Hassen2015). The result was that Ethiopian emperors in the seventeenth century ruled over a much-reduced territory centred on a new capital at Gondar, while the Oromo were divided into different kingdoms and societies, including integration into parts of the Christian Empire. Weakened by conflict and religious divisions, Ethiopian emperors were reduced to mere pawns in the hands of powerful regional leaders during the ‘Era of the Princes’ from 1769 to 1855 (Clapham Reference Clapham1969, Crummey Reference Crummey2000).

Figure 3.1 Ethiopian provinces as of 1963

State Centralisation, Expansion and External Military Threats

Most historians date the formation of the modern Ethiopian state to the reigns of Emperor Tewodros II (1855–1868), Yohannes IV (1872–1889) and Menelik II (1889–1913) (Zewde Reference Zewde1991). The expansionist claims of Egypt (1875–1876), and then Italy and Sudan highlighted the technological deficiency of the Ethiopian armies, and the need to centralise political power internally and to secure foreign manufactured weapons through trade. The result was the southward expansion of the empire to secure lucrative resources for commodity exports and a fundamental re-orientation of the Ethiopian state. This expansion, in turn, left a lasting legacy in terms of the territorial contours of the state and the challenge of nation-building.

A common critique of the Imperial land tenure system is that tenure insecurity undermined agricultural production incentives for both gult-holders and rist-holders, leading to agrarian stagnation. Gult-holders had no direct role in production and only had rights to extract tribute for as long as they retained the Emperor’s favour, providing strong incentives to extract rather invest in productivity. Likewise, rist-holders had rights to a share of community land, but not particular parcels. Periodic land redistributions and endless litigation provided a constant threat of loss of access to existing landholdings (Hoben Reference Hoben1973, Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984, Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). Consequently, the main means by which the state could increase economic production was to expand control over greater tracts of low productivity agriculture, rather than intensification of existing production. This expansionist dynamic was reinforced by the need for imported weapons to maintain independence from foreign aggression and to establish dominance against domestic rivals. Territorial conquest south of the Blue Nile and Awash rivers provided access to slaves, ivory and, particularly, coffee, key export commodities that increased state revenues and financed imports.

The provinces of Gojjam and Shewa, the southernmost points of Ethiopian territory, were best placed for this southern conquest. Shewa expanded its territory from Amharic-speaking areas in the north of the province into Afaan Oromo speaking areas to the south from the second half of the eighteenth century (Zewde Reference Zewde1991). In 1882, Shewa defeated Gojjam at the Battle of Embabo to secure Shewan dominance over the south. During the 1880s, Menelik II, as king of Shewa, built on this victory to establish Shewan control of Oromo-speaking societies in Nekemte, Jimma, Illubabor and Arssi and the lucrative trade opportunities that these afforded. Following Emperor Yohannes’ death in battle with the Sudanese, Menelik became Emperor and signalled the southward shift in political and economic power by moving his capital from Ankober in north Shewa to the newly established city of Addis Ababa in 1891.

Meanwhile, the external threat in the north continued to grow. The Italians seized the port of Massawa when the Egyptians were defeated by Yohannes IV in 1875–1876. Italy subsequently established a colony in Eritrea in 1890 and invaded Ethiopia in 1896. The remarkable victory of the Ethiopians at the Battle of Adwa was a testament to the centralisation of power under Menelik, a brief moment of unity within the Ethiopian nobility, as well as strategic errors by what was one of Europe’s weakest powers (Zewde Reference Zewde1991). Controversially, Menelik decided not to build on this victory by removing the Italians from Eritrea, instead signing a treaty that ceded the territory in exchange for Italian recognition of Ethiopian sovereignty. The treaty left Ethiopia landlocked and divided the Tigrigna-speaking population between colonial Eritrea and Ethiopia’s Tigray province. Nonetheless, victory secured independence for a further four decades and ensured that Ethiopia’s subsequent brush with European colonialism was brief.

Following Adwa, Menelik raced with neighbouring European colonialists to expand Ethiopian territory to the west, south and east (Zewde Reference Zewde1991). Ethiopia’s borders were settled in treaties with France, Italy and the United Kingdom in 1897 and 1900. In doing so, Menelik incorporated into Ethiopia some areas which had been under Ethiopian control in the near or distant past, some which had long been in contact with Ethiopia through trade links and raids, and some which were well beyond any previous Ethiopian claims. Thanks to the vast and rapid territorial expansion, Addis Ababa – at the southern tip of the Ethiopian empire when established – found itself at the geographical centre of the country by the early twentieth century.

Menelik pursued distinct strategies for incorporating new territories, ruling through tribute-paying local leaders where they submitted peacefully and establishing direct control where they faced resistance (Markakis Reference Markakis1974, Tareke Reference Tareke1991, Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). In contrast, in remote areas of the west, south and east the state established very little state presence despite its territorial claims. Where previous leaders had resisted Menelik, their removal necessitated new forms of control in order to extract resources. Supported by a string of military garrisons that would provide the seed of many towns in the south, the Emperor expropriated vast amounts of land and allocated gult rights to churches and military leaders (neftegna) (Crummey Reference Crummey2000). While the farmers were, like in the north, known as gebbar, unlike in northern Ethiopia, gebbar did not have rist rights, but were tribute-paying tenants and subject to labour service. Responsibility for keeping the local population in line and extracting tribute often fell to local leaders who were given economic privileges in return (Markakis Reference Markakis1974). The result was the imposition of highly exploitative class relations overlaid on ethno-linguistic divisions between the neftegna – generally Amharic or Tigrigna-speakers from northern Ethiopia or co-opted local leaders – and the southern gebbar.

A major legacy of the Menelik era was therefore to lay the foundations of an ethnically, religiously and linguistically diverse state. However, it is important not to impose contemporary ethnic identities retrospectively onto the past. Today’s ethnic identities are the product of political projects of nationalist and ethno-nationalist mobilisation over the following century. Ethiopian state-building in the early twentieth century was an elite project, which sought legitimacy in terms of the divine right to rule of the descendants of Solomon and Sheba, rather any claims to rule on behalf of a national population. Moreover, in overwhelmingly rural societies where claims to land and livelihood depended on local relationships within the descent group and with little in the way of literacy or media, transport or communication links, identities were overwhelmingly local rather than pan-ethnic (Tareke Reference Tareke2009). This applies just as much to the Amharic and Tigrigna-speaking north, which was divided into provinces and awraja (counties), as it did in the south, where speakers of Afaan Oromo and other languages were divided into distinct polities and communities (Hassen Reference Hassen1990, Keller Reference Keller1995, Michael Reference Michael2008, Tareke Reference Tareke2009). The late nineteenth century state expansion, meanwhile, meant that Amharic and Tigrigna speakers – who shared linguistic and religious ties and previously formed the majority – came to be a minority as the country incorporated many groups with few if any shared linguistic, religious or cultural ties. Ethnic identities were by no means pre-determined at this point. However, with the subsequent global spread of nationalism as a form of political organisation and as leaders embraced the idea of ruling on behalf of ‘the people’, this diversity would inevitably present a challenge to the construction of a cohesive nation-state.

Menelik’s reign was, therefore, a defining moment for the Ethiopian state, centralising political power and securing sovereignty at the Battle of Adwa, as well as expanding territorial claims to contemporary borders. Menelik also undertook a number of state reforms, establishing a National Bank, cabinet government and formal education. However, the Emperor suffered a stroke in 1906 that incapacitated him until his death in 1913. The fragmentation of political power during the succession struggle slowed reforms under Lijj Iyasu (1913–1916) and Empress Zewditu (1916–1930), who governed with her regent, Ras Tafari. Over time, Tafari gradually consolidated power and became Ethiopia’s de facto ruler. He was eventually crowned Emperor Haile Selassie following Zewditu’s death in 1930.

Modernisation and Stagnation

Haile Selassie’s reign, like those of his predecessors, was shaped by the dual challenge of maintaining Ethiopia’s independence from European colonialists, and centralising power domestically. Initial efforts at state-building were curtailed by the Italian occupation of Ethiopia in 1936–1941. However, the Italians’ revenge for the loss at Adwa was short lived, with Ethiopian resistance fighters and the British military removing the Italians during the Second World War. While the Emperor made significant progress in strengthening the state on his return to power, his reforms were ultimately constrained by resistance from the nobility, while nation-building efforts contributed to growing ethno-political mobilisation.

Under Haile Selassie, Ethiopia began the transition from a mediated state – in which the Emperor ruled through the nobility – to an absolutist monarchy with a centralised state bureaucracy (Zewde Reference Zewde1984). Ethiopia’s first constitution in 1931 and a revision in 1955 enhanced Imperial powers over the nobility, and created a national standing army, rather than relying on the private armies of provincial leaders. Following the Italian occupation, the Emperor introduced the position of Prime Minister, re-established ministries, and re-organised the country into 14 provinces, 100 awraja and some 600 wereda (districts) (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, p. 102). A centrally appointed and salaried official was placed at each level of this administration, in contrast to the past practice of using gult as a reward for service (Markakis Reference Markakis1974, Crummey Reference Crummey2000, Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). A necessary corollary of this growing state bureaucracy was increased taxation, with standardisation of the tax structure and the move to payment in cash rather than in kind. Likewise, the government expanded education to staff the growing bureaucracy, including the establishment of Haile Selassie I University in 1961 and scholarships for students to study in Europe and North America.

Despite major changes, the result was far from a Weberian ideal-type bureaucracy. State positions were often allocated not on merit but as patronage, enabling the Emperor to balance contending factions amongst the nobility (Clapham Reference Clapham1969, Markakis Reference Markakis1974, Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). Moreover, there remained limits to state infrastructural power, even in the central highlands, where, below the wereda, there was not even ‘the fiction of modern administration’ (Ottaway Reference Ottaway1977, p. 85). Instead, the chika shum, the hereditary village headman, recruited from the landholders remained the key figure linking the wereda to the local population (Tareke Reference Tareke1991).

Bureaucratic reforms also aimed to promote agricultural commercialisation, expand commodity exports and increase state revenues, which primarily derived from recently incorporated areas in southern Ethiopia (Donham Reference Donham, Donham and James2002). While the neftegna-gebbar system and allocation of gult rights had proven an effective means of establishing political control over the south, it did not serve economic requirements. Characterised by absentee landlords and insecure tenancy arrangements, there was little incentive to invest in production (Brietzke Reference Brietzke1976, Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984). Meanwhile, the state’s reliance on intermediaries meant much of the surplus never reached the central state. State bureaucratisation went some way to replacing the role of the nobility, but taking advantage of the economic opportunities afforded by international trade – particular for coffee – required exerting direct control over producers (Crummey Reference Crummey2000).

Reforms in the 1940s and then the 1960s sought to end labour and tribute requirements, eliminate gult and covert land to freehold, and establish direct taxation. In northern Ethiopia, however, reforms were fiercely resisted by both the landed elite, who resisted the attempt to remove their powers and privileges, and the peasantry, who feared loss of rist rights (Tareke Reference Tareke1991). The first revolt, known as the Weyane, took place in southern and eastern Tigray in 1943, sparked by diverse grievances related to recent reforms and which was ultimately crushed with the support of the British army and air force. Similarly, the passing of an agricultural income tax in 1967 was abandoned after a year of rebellion in Gojjam. In southern Ethiopia, meanwhile, reforms failed to improve conditions for the gebbar and in some cases made them worse as a result of the conversion of gult rights to private property, fraudulent land expropriations and the failure to end labour obligations (Tareke Reference Tareke1991, Zewde Reference Zewde1991). These factors, along with Somalia’s push for creation of a Greater Somalia including southeast Ethiopia, contributed to a major rebellion in Bale from 1963 to 1970 that was eventually suppressed by the military (Tareke Reference Tareke1991, Østebø Reference Østebø2020a).

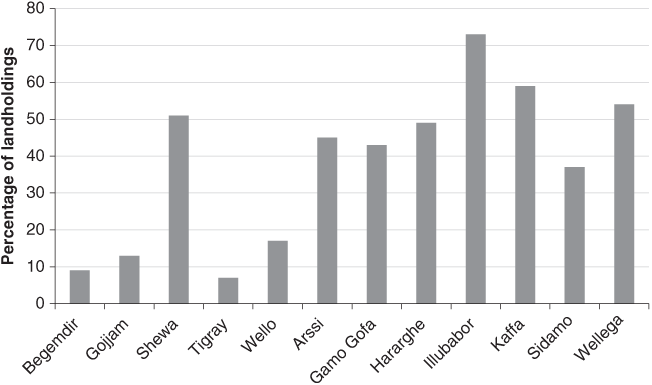

From the 1960s, the student movement and several donor agencies highlighted the failings of the agrarian economy and the need for land reform (Cohen Reference Cohen1985, Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2020). Yet, it was only in 1966 that the Emperor paid any attention to smallholder agriculture with the creation of the Ministry of Land Reform in 1966 and a focus on raising smallholder productivity in the third five-year plan (1968–1973). However, attempts to regulate tenancy arrangements – let alone far-reaching land reforms – were blocked by the nobility that dominated parliament. For ministry officials, the Emperor merely established a ‘fake’ ministry to placate donors and students, rather making a meaningful attempt to reform the agrarian system (Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2020, also Brietzke Reference Brietzke1976). Ultimately, the Emperor was unable or unwilling to push through agrarian reform in the face of a powerful landed nobility, which had much to lose. The result was that by the end of the Imperial era, the prevalence of tenancy still mapped closely on to the pattern of nineteenth century state expansion. As shown in Figure 3.2, tenancy was very low in northern provinces of Begemdir, Gojjam, Tigray and Wello where rist was common. In contrast, in the recently incorporated south, tenancy was as high as 73 per cent in some provinces.Footnote 3 Shewa, in turn, represented the dividing line, with rist common in the historic northern core of the province and tenancy prevalent in the more recently incorporated south.

Figure 3.2 Rented landholdings by province (1966–1968)

Instead, the main economic priority for the Imperial government was to use foreign investment to promote import substitution and some exports. This included foreign investments in large-scale, ‘modern’ agriculture producing sugar and cotton in the Awash Basin, and sesame in Humera, north-western Ethiopia (Ashami Reference Ashami1985, Zewde Reference Zewde and Zewde2008a, Puddu Reference Puddu2016). These investments avoided disruption to the political order in the highlands but necessitated displacement of pastoralists from grazing lands and water access. These plantations were also linked to new foreign-owned factories for agro-processing for domestic markets, including sugar factories at Wenji-Shoa and Metehara, and textile factories at Bahir Dar and Akaki (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Zewde Reference Zewde1991). By 1974, however, the industrial economy remained miniscule, and any incipient processes of capitalist transformation that had begun were ‘stopped in their tracks’ by the revolution of 1974 (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, p. 164).

Haile Selassie inherited from Menelik a legacy of an extremely linguistically and culturally diverse population. Attempts to modernise the state apparatus, to expand educational opportunities, and improvements in transport and communications all served to highlight this diversity and the great inequality between ethno-linguistic groups. Moreover, as Haile Selassie sought to modernise his administration and supplement his divine rights with popular legitimacy, this raised the question as to what sort of ‘nation’ Ethiopia was.Footnote 4 The nation-building challenge was further enhanced by the federation of Eritrea with Ethiopia in 1952, and the Emperor’s subsequent move to integrate the region as an Ethiopian province in 1962. The Emperor sought to build an Ethiopian nation in continuity with longstanding principles of Imperial state-building that rested on the expansion of the Amharic language and Orthodox Church. Access to state employment, services and the legal system required fluency in Amharic, while the development of other written languages was forbidden in an attempt to promote a single national language and identity (Cohen Reference Cohen and Turton2006, Hussein Reference Hussein2008). While this undoubtedly contributed to ethnic inequality, it did not necessarily mean that all non-Amhara were barred from state positions. Rather non-Amhara had to learn Amharic, and often adopt Orthodox Christianity and Amhara names in order to advance within the system (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Michael Reference Michael2008).

Haile Selassie’s legacy is therefore a mixed one. As regent and in his initial decades as Emperor he took major strides in transforming and strengthening the state, as well as restoring Ethiopia’s independence following the Italian occupation. However, in the last decades of his rule, the aging Emperor lost the will for reform and failed to drive through the changes that might have resulted in greater economic dynamism or equality.

Imperial Collapse and the Competition to Control the Revolution

To many observers, it was clear by the 1960s that the ‘future of the existing traditional monarchies [including Ethiopia’s] is bleak’ (Huntington Reference Huntington1968, p. 191). Indeed, growing dissatisfaction amongst the military, the civil service, the student population, urban workers and the peasantry, and the failure of the Imperial regime to take the far-reaching measures required to address these grievances culminated in the revolution that began in 1974.

The process leading to 1974 was long and complex.Footnote 5 A failed coup by the Imperial bodyguard in 1960 punctured the Emperor’s image of invincibility and sparked the subsequent student movement (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Tareke Reference Tareke2009). Likewise, peasant rebellions in Tigray, Bale, Gojjam, Wello and Gedeo highlighted inequality and economic stagnation, while providing one of the movement’s main slogans: ‘land to the tiller’ (Tareke Reference Tareke1991, Zewde Reference Zewde1991). The 1973 famine in Tigray and Wello that is estimated to have killed 200,000 also served to delegitimise a regime that failed to respond. Furthermore, the union with Eritrea forced the national question to the fore and led to the establishment of the secessionist Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) in 1961 whose rebellion grew into a major conflict, stretching the military and fostering divisions.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s the student movement within Ethiopia and at universities in Europe and North America was a central focus of resistance to the Imperial regime and a source of ideas on how to reshape state and society (Tareke Reference Tareke2009, Zeleke Reference Zeleke2019). While Haile Selassie had taken a personal interest in expanding educational opportunities, for many students, exposure to the outside world highlighted how Ethiopia had fallen behind not just the advanced economies, but also many African former colonies. Moreover, many students found that education did not necessarily lead to the employment opportunities that they had expected (Markakis Reference Markakis1974). Inspired by African independence and the US civil rights movements, students engaged in annual mass demonstrations from 1965, as well as vigorous debate in newspapers and journals that increasingly drew on Marxist and anti-Imperialist theories (Zeleke Reference Zeleke2019). The growing threat posed by the movement inevitably led to state repression, forcing many leaders into exile.

The student movement came to focus on two fundamental questions that shaped the revolution and, indeed, Ethiopian politics through to the present day. The first was the land question and the need to address the inequality and stagnation of the agrarian economy. The second was the national question concerning the interpretation of Ethiopian history and how to structure politics in an ethnically and linguistically diverse country. Particularly influential was a famous speech by a student, Walleligne Makonnen (Reference Mekonnen1969), in which he argued that for members of the diverse ethnic groups ‘to be an Ethiopian, you will have to wear an Amhara mask’. The ensuing debates were dominated by Stalin’s essay on the National Question and his definition of nations, nationalities and peoples (Zeleke Reference Zeleke2019). Though the majority of those involved agreed on the necessity of self-determination for ethnic groups, the main dividing lines concerned whether the national question was merely a manifestation of class oppression or whether addressing the national question was essential to overcoming class oppression.

The revolution itself began as a series of relatively minor events in early 1974 that snowballed, culminating in the removal of the Emperor in September. The first was a mutiny by an army division in Negelle Borana in January over food rations and salaries that sparked unrest in other military units (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Zewde Reference Zewde1991). This was followed in February by strikes by teachers and taxi drivers, and a general strike in March, all supported by the students. As urban areas were paralysed by unrest, the lower ranks of the army selected a committee of divisional representatives named the Derg to coordinate the military’s demands. From June onwards, the Derg conducted a ‘creeping coup’ involving ‘the slow but systematic erosion of imperial power culminating in the disposition of the emperor’ (Zewde Reference Zewde1991, p. 234). When Haile Selassie was finally detained, the Derg took power. As is common following regime overthrow, the Emperor’s removal provoked a contest for power. Indeed, the Derg was internally divided, and faced considerable opposition from the urban groups – the students, teachers and unions – that had launched the revolution, and the nobility who were threatened by it. Key Derg leaders moved quickly to eliminate opposition and consolidate the regime’s control over society. Despite much bloodshed, it never quite succeeded.

Mengistu Hailemariam rose from a junior member of the Derg to the sole leader by 1977, eliminating his rivals one by one. The new regime also quickly moved from its initial position, which espoused Ethiopian nationalism and support of the Emperor, to a radical socialist outlook and a full frontal attack on the ancien régime (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). The first move in this direction was in November 1974 when the Derg executed some sixty members of the aristocracy and senior military officials. This was followed in early 1975 by the nationalisation of the financial sector, private enterprises, and, as discussed in the following section, rural and urban land reform. Land reform eliminated the economic base of the nobility, and initial attempts by former governors of Tigray and Gondar to resist the new regime by organising the Ethiopian Democratic Union were subdued by 1977.

The Derg’s turn to socialism was heavily influenced by the student movement, including returning students from Europe and North America (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Zewde Reference Zewde1991). The student movement crystallised into two sharply divided parties, which competed to form the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary vanguard. These were MEISON (All Ethiopia Socialist Movement) that critically engaged with the Derg from 1975 and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP), which resisted the military takeover. From 1976, the EPRP began a campaign of urban terrorism, assassinating MEISON and regime officials, while the Derg moved to eliminate the EPRP in a period known as the Red Terror. The Derg’s bloody campaign forced EPRP remnants to withdraw from urban areas, and the Derg proceeded to eliminate MEISON, which it had come to view as a threat (Zewde Reference Zewde1991).

As is often the case, the weakness of the Ethiopian state following the revolution was seen as an opportunity by neighbouring states (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979, Clapham Reference Clapham1988). The Somali army invaded in 1977 claiming south-eastern Ethiopia, which was incorporated under Menelik and contained a large Somali-speaking population. Despite rapid Somali advances, the tide turned as a result of Ethiopian mobilisation and the Soviet Union’s decision to end its support to Somalia and switch allegiances to the Derg (Patman Reference Patman2009). With Soviet and Cuban support, the Ethiopian army removed Somali forces from Ethiopia by early 1978.

By 1978, Mengistu Hailemariam had gone a considerable way to consolidating his position, eliminating the nobility, urban opposition and the Somali threat. With the Derg’s attention elsewhere, however, by this time a range of rural insurgencies were well established across the country. The result, as Tareke (Reference Tareke2009) argues, was competition between multiple revolutionary movements that were divided by the national question. The Derg took a nationalist stance, rejecting self-determination for Eritrea and other ethnic groups, and viewed the national question as a diversion from class struggle.Footnote 6 Having consolidated control of urban and many rural areas, the regime sought to extend its control and eliminate its rivals. In contrast, a range of rural insurgencies, some of which began before 1974, sought to fight their way to power. For the most part, these groups were ethno-nationalists that favoured self-determination up to and including secession.

The strongest insurgencies were in Eritrea. The ELF launched an insurrection in 1961 in response to Haile Selassie’s annexation of Eritrea and achieved considerable military success (Pool Reference Pool and Clapham1998). However, the ELF subsequently fragmented along ethnic lines and suffered major reversals in the late 1960s (Woldemariam Reference Woldemariam2018). Several splinter groups merged to form the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) in 1972 (Pool Reference Pool and Clapham1998). Both the ELF and EPLF benefitted from the diversion of revolutionary upheaval and the Somali conflict, extending their territory across much of Eritrea. Following the end of the Somali conflict, however, the Ethiopian military focused on Eritrea and came close to eliminating both groups. The ELF never recovered as a major force, while the EPLF managed to resist repeated attacks. After years of stalemate and in coordination with the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), discussed below, the EPLF wore down the Ethiopian army, securing full control of Eritrea in the late 1980s and subsequent independence.

Another ethno-nationalist insurgency that pre-dated the revolution is the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). Despite forming the largest ethno-linguistic group in Ethiopia, Oromo ethno-nationalism arose relatively late on. Haile Selassie’s efforts to build a centralised state provided an important impulse to Oromo ethno-nationalism through access to education, state bureaucracy and imposition of Amharic. As Baxter (Reference Baxter1978, p. 290) argues, the ‘new pan-Oromo consciousness was generated in the army, the University and the Parliament itself’. An important step was the creation of the Mecha and Tulama Self Help Association formed to promote Oromo identity in 1967. Alarmed, the Imperial regime banned the organisation and arrested its leadership. Nonetheless, Mecha and Tulama provided the inspiration and many of the members of what became the OLF, which was founded in late 1973 in Bale and Hararghe. While the EPLF and TPLF benefitted from the distraction of the Somali conflict, the OLF instead found itself caught in the midst of the war, and subsequently relocated its base to Wellega in western Ethiopia (Keller Reference Keller1995, Woldemariam Reference Woldemariam2018). Though the OLF made some gains against the Derg, these did not compare to those of the EPLF and TPLF in the north. The OLF remained militarily weak by 1991 when the Derg was removed from power.

Competing Revolutions: The Derg’s Military Marxism

The Derg not only ended seven hundred years of the Solomonic dynasty, but also transformed the economic, social and political basis of the country. Among its first and most significant acts, the Derg nationalised all rural land in March 1975, one of the most radical and far-reaching land reforms in the world. However, neither land reform nor the resulting transformation of the agrarian structure was set in stone from the beginning. While the need for some agrarian reform was widely acknowledged, there was considerable debate as to the best way forward. For revolutionaries, radical land reform was essential to promote equality, while for moderates the principal objective was the promotion of agricultural productivity through limited land redistribution and privatisation (Cohen Reference Cohen1985, Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2020).

The decision to pursue a radical land reform was heavily shaped by the student movement (Tareke Reference Tareke2009, Zeleke Reference Zeleke2019). Moreover, the Derg’s decisive break from the Imperial regime – symbolised by the November 1974 execution of leading aristocrats – enabled land reform as a means of destroying the economic basis of the nobility, which posed a powerful obstacle to state authority (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). In late 1974, Zegeye Asfaw – a former official in the Ministry of Land Reform that had failed to secure any changes under the Imperial regime – was approached by two of the radical faction of the Derg officers for advice. These officers were quite clear that, ‘We don’t want to make amendments every year. We want to have an ultimate law to end the feudal regime’ (Zegeye Asfaw, cited in Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2020, p. 28).Footnote 7

The resulting proclamation nationalised all land, and distributed usufruct rights to peasant households up to a maximum limit of 10 hectares (a limit that was rarely reached in practice), as well as prohibiting sales, rental, inheritance, mortgaging and wage labour to prevent land consolidation and labour exploitation (PDRE 1975a). Land was to be redistributed every 2–3 years to take into account demographic changes. Moreover, the rural land reform was followed by the nationalisation of urban land in July 1975 (PDRE 1975b). According to Zegeye, the intention was to put an end to the ‘counter revolution’ by landlords who also dominated urban land ownership and were thought to be regrouping to ‘sabotage the revolution’ (Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2020, p. 45). Finally, the few large-scale agricultural investments, mostly foreign owned, were turned into state farms.

Peasant Associations were established beneath the wereda as means of ‘creating a new political and social organization in the countryside’, incorporating the administrative and judicial functions of the chika shum and effectively forming another tier of state administration (Ottaway Reference Ottaway1977, p. 80, Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984, Clapham Reference Clapham1988). According to official figures, by 1977, 24,700 Peasant Associations had been established with 6.7 million members (Ottaway Reference Ottaway1977, p. 79). In addition, the Derg sent campaigns of high school and university students to bring the revolution to the countryside, while conveniently removing an influential group from the cities as the Derg consolidated power (Ottaway Reference Ottaway1977).

While land reform was undoubtedly influenced by socialist ideology, nationalisation was a prime example of coercive distribution whereby rival elites are displaced and the state consolidates its control over the peasantry (Albertus et al. Reference Albertus, Fenner and Slater2018). The revolution inevitably led to ‘an enormous upsurge in popular political mobilisation, which needs to be channelled and restricted in the post-revolutionary period’ (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, p. 9). Land redistribution and the expansion of state infrastructural power through peasant associations, urban dwellers’ associations and mass organisations aimed to consolidate the regime’s control of the urban and rural masses.

Implementation of these radical reforms was remarkably thorough, with the exception of parts of Eritrea and Tigray where Derg authority was challenged by competing revolutionaries. A 1979/80 survey found that peasant holdings covered 87 per cent of the cropland area, with collective and state farms making up the remainder, a stark contrast to the prevalence of tenancy pre-revolution (Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984, p. 72). Land reform secured significant popularity in the south where agrarian relations – overlaid on ethnic divisions – were extremely exploitative. The main impact was not so much about land distribution, since most farmers continued to cultivate similar holdings, but rather eliminating the exactions of the landed elite (Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984). In the north, previous tenure regimes were generally less exploitative and land reform less popular. Indeed, the Derg’s top-down approach to land reform at times alienated northern peasants (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, Young Reference Young1997). Nonetheless, state ownership meant the abolition of gult and fit with key principles of previous northern tenure systems – that community members had the right to a share of community land, rather than individual rights to a particular plot (Hoben Reference Hoben2001). Land reform transformed the agrarian structure from one of considerable heterogeneity in the Imperial era towards the homogeneity of peasant production (Rahmato Reference Rahmato, Rahmato and Assefa2006).

While land reform improved the circumstances of the rural population, it also removed the mechanism of surplus extraction based on the nobility. The result was an urban food crisis that necessitated further reforms to provide food for the cities (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). The Agricultural Marketing Corporation consequently required farmers to provide fixed quotas of crops at low prices. While this ensured a supply for urban areas, it removed farmers’ production incentives and imposed considerable hardship (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). From 1983 onwards, there were attempts to promote collective agriculture through producer cooperatives and villagisation, aiming to achieve economies of scale, enhance control over agricultural production and support conscription for the armed forces (Clapham Reference Clapham1988).

The Derg’s industrial strategy likewise entailed bringing industrial production of any substantial scale under state ownership, nationalising the small number of existing factories from their foreign owners (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). Industrial expansion, meanwhile, rested on financial and technical support from aligned socialist countries, with a tendency towards a small number of large, symbolic projects aimed at domestic supply, including the Mugher cement factory, a textile mill in Kombolcha and a tractor factory in Nazret. Industry remained a small, though growing, part of the economy with the state-dominated sector concentrated in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa and the string of towns along the railway, and Asmara. Most state firms, however, were highly inefficient and lacked incentives for productivity improvements.

The Derg therefore pursued a new direction in its attempt to resolve the agrarian question, motivated by political concerns, but drawing heavily on socialist ideology and the models of the Soviet Union and China. In terms of the relations of production, the pre-capitalist landed elite was dispossessed, and replaced by peasant farmers, collective agriculture and state farms. As under Stalin’s Soviet Union, this agrarian system was expected to generate an agrarian ‘surplus’, which could then be extracted by the Agricultural Marketing Corporation to subsidise the cities and industrial development. Over time, Peasant Associations evolved from initially autonomous entities formed by the peasants into an additional tier of the state administration. The result of these reforms, as Rahmato (Reference Rahmato1984) has argued, was that the state effectively replaced the nobility as the landlord of the peasantry.

Politically, the Derg established the Ethiopian Workers’ Party in 1984 as a vanguard party to lead Ethiopia to state socialism. Despite an official commitment to the working class and the peasantry, however, the attitude towards the peasantry was ‘contemptuous’ (Crummey Reference Crummey2000, p. 245). Peasants were ‘seen as a problem rather than an asset, as tradition-bound, unthinking, and obdurate innocents who will react negatively to any new policy, and who must be forcibly re-educated to understand their own best interests’ (Brietzke Reference Brietzke1976, p. 654). While the land reform initially secured significant popular support in southern Ethiopia, this reserve of goodwill was subsequently eroded by state extraction and control.

The Derg’s failings were apparent to observers of the time. The removal of incentives for peasant and collective agriculture resulted in stagnant or declining agricultural productivity, while population growth and regular land redistributions meant the gradual erosion of landholding size (Rahmato Reference Rahmato1984, Reference Rahmato1991, Reference Rahmato1993). Meanwhile, state farms that received a disproportionate share of the state budget were poorly managed and grossly inefficient (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). In 1990, the Derg announced reforms aimed to win back support from insurgents in Tigray and Eritrea, including de-collectivisation, heritable land rights, removal of the restriction on hired labour, and the removal of quotas to the Marketing Corporation. These reforms had little impact, however, due to the rapid advances of the TPLF and EPLF.

The Derg era was therefore characterised by a continuous violent struggle as the regime sought to consolidate power. While the military regime came close to eliminating the threat posed by the EPLF and TPLF, it never quite succeeded in establishing full territorial control. Nonetheless, the reforms carried out under the Derg made a major contribution to expanding the capacity and reach of the state, as well as its autonomy from societal groups. Land reform and nationalisation eliminated the landed elite and the nascent capitalist class, leaving the state relatively free from organised societal interests. Moreover, the Derg expanded bureaucratic capacity and significantly extended its territorial reach through a process of encadrement, whereby land redistribution, and the establishment of cooperatives and collective agriculture, incorporated the peasantry into structures of control (Clapham Reference Clapham, James, Donham, Kurimoto and Triulzi2002). In doing so, the Derg’s revolution undoubtedly made a major contribution to the establishment of structures capable of state-led development, even if this potential was initially unrealised.

Competing Revolutions: The TPLF’s Peasant Insurrection

At the end of the 1970s, the main challenge to the Derg lay in Eritrea, in the form of the ELF and EPLF. However, soon after the 1974 revolution, the TPLF also commenced an insurgency that, after many years, would end in the Derg’s defeat and the TPLF’s ascent to national power.

The TPLF originated in the student movement at Haile Selassie I University. In the days after Haile Selassie was deposed in September 1974, a group of students formed the Tigray National Organisation, committing to launch a rural insurrection, which began in February 1975. This insurgency commenced with just a handful of members and four rifles at Dedebit in western Tigray, with the group renamed the TPLF (Berhe Reference Berhe2008). The group was inspired by Eritrean liberation movements and received training and support from the EPLF early on. Based on the practical reality of the area in which they found themselves, the TPLF adopted a Maoist strategy of organisation and warfare, with the Front’s survival dependent on the support of the peasantry (Young Reference Young1997, Berhe Reference Berhe2008). As Meles Zenawi, future Prime Minister, succinctly summed up later, ‘If they [the peasants] gave us food, we would have enough to eat. If they didn’t, we would go hungry’ (Meles, cited in Gill Reference Gill2010).

Despite the fact that early TPLF leaders comprised children of the lower ranks of the nobility (Young Reference Young1997), they were unusual amongst African liberation movements in following Mao in committing ‘class suicide’ by abandoning urban lives of the petty bourgeoisie ‘to swim among the masses like fish in the water’ (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire2002, pp. 181–182). Potential supporters and opponents were identified using a straightforward class analysis, with the poor and middle peasants considered the Front’s core constituency. Equally, the urban poor and working class were considered an ally, albeit the insurrection remained a rural affair until the late 1980s. In contrast the ‘feudal’ elite and the comprador bourgeoisie were identified as the TPLF’s opponents. The nature and revolutionary potential of the rich peasants and the national bourgeoisie were subject to considerable debate, drawing heavily on Marx and Mao, with the national bourgeoisie ultimately classified as a ‘wavering strategic ally’ (Tadesse and Young Reference Tadesse and Young2003; Berhe Reference Berhe2008, p. 223) while rich peasants could be ‘friends of the revolution’ (Young Reference Young1997, p. 137).Footnote 8 This ambiguity regarding the bourgeoisie was a recurrent issue for the EPRDF, as discussed in Chapter 4.

The key to the TPLF’s success lay in its ability to align the interests and ideological convictions of its urban intellectual leadership with those of the peasantry. Tigray in the 1970s certainly experienced widespread poverty and legitimate grounds for grievance. However, it is not clear that the rural population was on the verge of mass revolt until the TPLF mobilised the peasantry for this purpose. To do so, the TPLF relied on a dual strategy of mass distribution along class lines and the symbolic appeal of ethno-nationalism, underpinned by the organisational capacity of a Leninist party structure. As shown in Chapter 4, this combination also formed the basis of the party’s political strategy on taking national office.

A central feature of the TPLF’s distributive strategy was land, the key resource in any agrarian economy. While the Derg conducted land reform across Ethiopia, the TPLF and other revolutionary groups conducted their own land reforms in liberated areas from 1976. According to TPLF leaders at the time, land reform was not initially a top priority, but as the Derg and then the EPRP – displaced by the Red Terror to eastern Tigray – conducted land redistribution, the TPLF launched its own reforms to compete for peasant support (Young Reference Young1997, Berhe Reference Berhe2008). As with the Derg, TPLF land reform served as the first step in a strategy captured by the concept of ‘coercive distribution’, consolidating control of liberated areas by undercutting rival elites – the nobility, the Derg and the EPRP – and establishing direct ties of dependence with the peasantry.

A TPLF publication from the time echoed the Derg in justifying land reform as a means of freeing the Tigrayan peasantry from the ‘yoke of feudal rulers’ (People’s Voice 1982: 1, cited in Chiari Reference Chiari2004, p. 62). However, for the TPLF these ‘feudal rulers’ were particularly associated with the Shewan-Amhara nobility. Like under the Derg, TPLF land reform distributed rights to a share of community land and prohibited land sales and mortgaging that could otherwise lead to class differentiation. However, the TPLF differed in ways that demonstrated flexibility rather than ideological rigidity. In contrast to the Derg’s top-down reforms, the TPLF pursued a participative approach, involving communities in design and implementation, as means of building popular support (Young Reference Young1997, Chiari Reference Chiari2004, Berhe Reference Berhe2008). Notably, the TPLF allowed tenancy, wage labour and land rental, unlike the Derg’s prohibitions which had led to great resentment in Tigray where many relied on seasonal labour migration (Hendrie Reference Hendrie1999, Chiari Reference Chiari2004).Footnote 9

Access to land was the first part of a political strategy that sought peasant support through material distribution. However, this distributive strategy was always balanced with the overwhelming imperative – which approached ideological status – of self-reliance given the extreme resource shortages and minimal external support received by the Front.Footnote 10 The result was that the TPLF sought to mobilise the population to improve their circumstances, with any TPLF distribution accompanied by community contributions of labour and resources. This distributive strategy comprised the training of teachers, health workers and agricultural extension agents who were drafted to communities to establish basic services that had to that point been virtually non-existent. Education, health and agricultural productivity were all valued both as means of improving the lot of the peasantry and strengthening the physical and ideological capacity of TPLF fighters. The TPLF also formed the Relief Society of Tigray (REST) – formally an NGO, but essentially a wing of the TPLF – to provide emergency relief, with REST assuming a particularly important role during the 1984/85 famine. Once again, however, the TPLF sought to link food aid to productive activity by making support conditional on participation in public works (Lavers Reference Lavers2019a, Reference Lavers2019b).

Alongside this mass distributive strategy, the TPLF sought to mobilise the peasantry through the symbolic power of ethno-nationalism, drawing on student debates regarding the national question. Unlike the Derg, which viewed ethnicity as a diversion from class consciousness, for the TPLF, ‘the Leninist ‘‘nation, nationality or people’’ was the largest unit across which the solidarity necessary for the mass mobilization they desired was possible’ (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2011, p. 627). As with other ethno-nationalist movements at the time, the TPLF was able to exploit existing grievances, but did not encounter fully formed ethnic self-identification amongst the peasantry. As Gebru Tareke argues,

most Tigrayans, who were peasants, had little concept of their nationality. More than 90 percent of the population were illiterate farmers and pastoralists who lived in isolated villages, each governed by a backward tradition of the spoken word. It was a world without roads, schools, newspapers, or postal and telegraph services. The world beyond the boundaries of the village and its parish was another country. Given the limited contact peasants had with either the state or other ethnic communities, they had little awareness of a social identity or collective destiny that transcended their rural communities.

Rather it was the TPLF, in applying concepts developed and adapted in the student movement, that helped forge Tigrayan ethno-nationalism through its programme of mass mobilisation. The TPLF framed its struggle as building on the glorious legacy of the Aksumite civilisation and the first Weyane’s valiant resistance to Shewan-Amhara oppression in 1943. Meanwhile, Tigray’s long-term economic decline was attributed to Shewan-Amhara exploitation that had divided the Tigrigna speaking population in Eritrea and marginalised the province (Tareke Reference Tareke2009). The TPLF struggle was therefore cast as a Second Weyane that would pursue self-determination for Tigray.Footnote 11

Central to both the distributive and symbolic appeals of the TPLF was the need for political organisation, enabling the party to reach out to the masses. The TPLF adopted a Leninist party structure based on the principles of revolutionary democracy and democratic centralism. As others have noted, revolutionary democracy is a somewhat flexible concept that has evolved over time (Bach Reference Bach2011, Vaughan Reference Vaughan2011). According to one of the TPLF’s founding members, revolutionary democracy was taken from Lenin’s work on ‘Bourgeois Democracy and the Proletarian Dictatorship’ (Berhe Reference Berhe2008, p. 234). In contrast to parliamentary or ‘bourgeois democracy’, revolutionary democracy entailed ‘a politically trained vanguard party representing “the masses”’ (Berhe Reference Berhe2008, p. 234). For the TPLF, land reform – undertaken in all liberated areas – turned rural society into a ‘“homogeneous mass” with common needs, interests, and political outlook’, enabling the Front to act in their interests as the vanguard (Vaughan and Tronvoll Reference Vaughan and Tronvoll2003, p. 117). Under democratic centralism, meanwhile, debate on policy and strategic positions was encouraged, with the vanguard party the sole actor able to take the ‘scattered and unsystematic ideas’ of the masses and concentrate these into a programme for action (Berhe Reference Berhe2020, p. 89). Once a decision was taken by the vanguard, it was binding on all members, with dissention and factionalism ‘strictly prohibited’ and severely punished (Milkias Reference Milkias2003, p. 13). The TPLF was based on collective leadership through elected executive and central committees, and the party congress. Accountability at all levels was ensured through gim gema (based on the Tigrigna word for evaluation), which requires all members to regularly self-critique their performance in front of their peers, before facing criticism of others.

Given the foundational need to win and maintain the support of the peasantry, from very early on the TPLF built administrative structures in areas liberated from the Derg to provide security and the infrastructure with which to distribute resources and promote its ethno-nationalist message. In effect, therefore, the TPLF was building party-state structures in competition with those of the Derg. Local administrations were established at tabiya (sub-district) level in 1980, initially with responsibilities for land reform and security, but subsequently expanding into economic and social affairs (Young Reference Young1997, Berhe Reference Berhe2020). This administrative system was extended to higher levels – namely, the wereda (district) and zoba (zone) – and down to the kushet (village) below the tabiya, which at that time reportedly comprised 40–50 households (Berhe Reference Berhe2008, Segers et al. Reference Segers, Dessein, Hagberg, Develtere, Haile and Deckers2009, Vaughan Reference Vaughan2011). In addition, the TPLF created mass associations by 1979, organising the population of liberated areas into associations for peasants, women, youth, traders and students (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2011, Berhe Reference Berhe2020). Political leaders, volunteer agricultural extension agents and community health workers worked through these structures to provide services (Adhanom et al. Reference Adhanom, Alemayehu, Bosma, Hanna Witten and Teklehaimanot1996, Barnabas and Zwi Reference Barnabas and Zwi1997), in effect tying distribution to the Front.

Several accounts of the TPLF by foreigners who spent time in Tigray in this period emphasise the Front’s participative nature and how it cultivated peasant support (Young Reference Young1997, Hammond Reference Hammond1999). Clearly the TPLF’s enormous success was dependent to a great extent on its ability to align itself with the peasantry and to secure popular support. However, it should be acknowledged that even at this early stage, the TPLF’s approach to political mobilisation centralised power within the political leadership and demanded peasants’ allegiance. The TPLF’s approach to land and social services closely approximates coercive distribution and there is evidence that where peasant support was not forthcoming, outright coercion underpinned the TPLF’s organisational strategy (Tareke Reference Tareke2009). It can hardly be a surprise, therefore, that on assuming national power, the TPLF did not show much inclination to compete for or share the power it had won militarily.

As discussed in Chapter 5, the basic principles of the agricultural development strategy that the Front subsequently pursued once in power nationally built on initiatives during the conflict. In particular, land reform and regular land redistributions created a class of relatively undifferentiated peasants as the Front’s core constituency. Meanwhile the TPLF sought to raise the agricultural productivity of all these farmers as means to ‘the final strategic aim of self-reliance in the agricultural sector’ (TPLF 1986, p. 8 cited in Chiari Reference Chiari2004). Specific measures included: training agricultural extension workers (Hammond Reference Hammond1999, Berhe Reference Berhe2020); distributing traditional and modern fertilisers, and select seeds; and a ‘standardisation’ policy, whereby leading farmers were supported to raise their productivity, as well as being encouraged to share their expertise with less effective farmers to bring all up to the same level (Chiari Reference Chiari2004, pp. 86–87). The TPLF also sought to balance socialist ideology with the necessity of securing peasant support, in doing so, avoiding many of the economic reforms that alienated the peasantry in Derg-controlled areas. The TPLF debated collective agriculture, but rejected it based on the negative experiences in Ethiopia and elsewhere (Young Reference Young1997, Chiari Reference Chiari2004). Likewise, while the TPLF formally committed to a planned economy (TPLF 1983) and initially experimented with trade and marketing controls, these were abandoned due to resistance from poor peasants working as traders (Young Reference Young1997). The TPLF’s agricultural strategy was also spatially differentiated from early on: while the peasantry was the central focus in densely-populated highlands, there was an attempt to lease larger plots to agricultural investors in more sparsely-populated areas of lowland Humera in the late 1980s (Bruce et al. Reference Bruce, Hoben and Rahmato1994, Chiari Reference Chiari2004). As such, the TPLF’s political strategy provided the outline of an agricultural development strategy, albeit that available documents fall short of a complete response to the agrarian question, with little apparent discussion of the role of agriculture within accumulation and its contribution to industrialisation.

The TPLF’s progression from rural insurgency to national government was long and arduous. The conflict and the TPLF’s evolving political and military strategy inevitably placed enormous strain on the TPLF leadership. The result was a number of leadership splits, and the departure and death of several influential figures.Footnote 12 Nonetheless, the system of collective leadership was retained, with several founding members – including Seyoum Mesfin and Abay Tsehaye – and early recruits – including Meles Zenawi and Sebhat Nega – maintaining senior roles in the Front and taking senior positions in the new national government after 1991. Meles Zenawi, who came to play an outsized role, rose to chairman of the TPLF and EPRDF in 1989, though very much as first among equals within the system of collective leadership.

When the TPLF launched its insurgency in 1975 it undoubtedly benefitted from the revolutionary upheaval, the Somali war and the Derg’s focus on more established insurgencies in Eritrea. While the Derg paid comparatively less attention to the TPLF, the Front nonetheless faced major challenges from competing groups in Tigray. These included the Tigrayan Liberation Front that aimed to create a Greater Tigray including Tigrigna-speaking populations in Eritrea, the monarchist Ethiopian Democratic Union in the west and the remnants of the EPRP in Eastern Tigray. Ultimately the TPLF defeated each of these competitors by 1978 (Young Reference Young1997, Tareke Reference Tareke2009). The battle-hardened TPLF then focused its attention on the Derg, employing a Maoist strategy of small, highly mobile units that sought to wear down the army through surprise attacks rather than direct confrontation.

Throughout the war, relations with the EPLF to the north were mixed. Undoubtedly the two Fronts benefitted from each other’s presence, and it is likely that neither would have succeeded alone. Yet collaboration was difficult to achieve. The EPLF initially favoured the EPRP, rather than the TPLF, while the TPLF and EPLF fell out around 1985 over the national question in Eritrea and military tactics, leading the EPLF to block passage of food aid to Tigray in the midst of the catastrophic famine (Young Reference Young1997, Berhe Reference Berhe2008, Tareke Reference Tareke2009). Ultimately, the two Fronts renewed contact and formed a tactical alliance from 1988, enabling them to coordinate attacks and achieve major successes first in Eritrea and then in Tigray (Tareke Reference Tareke2009). Attempts to form a comparable alliance between the TPLF and OLF were even less successful, with TPLF leaders doubting the OLF’s organisational capacities and revolutionary credentials.

Gradually, the conflict, economic crisis and withdrawal of Soviet support for the Derg after the fall of the Berlin Wall led to the collapse of the Ethiopian army, resulting in the liberation of Tigray and Eritrea in 1989 and the capture of Addis Ababa in 1991.Footnote 13 As the TPLF advanced it confronted the question of how to extend its political strategy beyond Tigray. As Thandika Mkandawire notes, by extending Mao’s famous metaphor, a regional rebel movement outside its home base risks becoming ‘fish on dry land’ (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire2002, p. 201). The TPLF’s strategy was to extend its approach to political mobilisation in Tigray, based on peasant mobilisation through mass distribution and ethno-nationalism, to the rest of Ethiopia. The TPLF formed the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of ethnic parties to represent Ethiopia’s diverse ‘nations, nationalities and peoples’. The first ally was the Ethiopian Peoples’ Democratic Movement (EPDM), formed by an EPRP splinter group which had already established some operations in Wello, to the south of Tigray. The organisation was subsequently re-named the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), limiting its operations to Amharic-speaking areas. In 1989, the TPLF formed the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation (OPDO), originally consisting of Oromo prisoners of war captured by the TPLF and subjected to political training (Vaughan Reference Vaughan2003, Reference Vaughan2011).Footnote 14

Conclusion

The key point of this chapter is to analyse how the history of state formation and the revolution shaped the structure of the state and its potential role in state-led development. The revolution thrust to the fore two fundamental questions about the nature of the Ethiopian state and society, namely those concerning land and nationalities. The Derg and other revolutionary movements sought to address the land question by dismantling the previous tenure system and the class structure on which it rested, distributing usufruct rights to landholders. While doing much to address inequality, subsequent policies tended to undermine production incentives, however. Rapid population growth, land shortages, low productivity and low levels of industrialisation meant that land reform only provided a partial and unsatisfactory answer to the broader agrarian question.

The Derg’s failure to tackle the national question was even more definitive. As should be clear from the preceding discussion, the process leading to the creation of a linguistically, religiously and culturally diverse population is a long and complex one that defies simple characterisation. Over the past millennium at least, there has been considerable fluidity in the territorial control of different polities, just as there has been fluidity in language, religion and culture, with forced and, perhaps, voluntary assimilation of different ethnic groups. Nonetheless, the historical record provides certain pieces of evidence that can be, and have been, cherry-picked by different actors to present sharply contrasting narratives (Gudina Reference Gudina and Turton2006). The first emphasises the continuity of the Ethiopian state over the last 2,000 years to the Aksumite Empire (or 3,000 if this is stretched to the myth of Solomonic descent), the maximum territory secured prior to Ahmad Gragn’s invasion and thereby the historic integrity of ‘Greater Ethiopia’. The second frames Menelik’s territorial expansion as a colonial conquest, in which non-Amhara were forcibly incorporated by the Shewan-Amhara state, reducing modern Ethiopian history to a single century of ethnic oppression. The Derg’s attempts to consolidate control of the expanded territory inherited from Menelik and Haile Selassie, and to build Ethiopian nationalism was subsequently replaced by ethno-nationalists who sought to apply the principle of self-determination to resolve the challenge represented by Ethiopia’s diverse and, increasingly, ethnic self-identifying population.

As Theda Skocpol argued, the removal of the ancien régime inevitably results in a power vacuum with contending revolutionary groups competing for power, a struggle that only ends when one develops sufficient organisational capacity to establish control. In Ethiopia, the Emperor’s displacement resulted in competing revolutionary movements in urban and rural areas. While the military was initially best placed to take power, the Derg never managed to extinguish competing rural revolutionary movements. It was only with the victory of the EPLF and TPLF in 1991 that the revolutionary fervour unleashed in the 1970s finally played out. As such, the TPLF is, in important respects, a product of the student movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and the revolution that displaced the Emperor. As such, I argue that a critical assessment of the EPRDF’s time in office must be rooted in an understanding of the revolutionary processes that led to its formation. This stands in contrast to much of the literature, which tends to analyse Ethiopian politics in terms of a sequential periodisation, with the Derg responding to the challenges presented by the Imperial era, while the EPRDF responded to the failings of the Derg era. The TPLF was forged through its assessment of and response to the Imperial era, as much as its struggle with the Derg.

The legacy of the revolution was that the EPRDF inherited a state structure that, in certain respects, provided significant potential for state-led development. First, the new government had considerable autonomy from societal groups. There was no landed elite, no capitalist class and all competing revolutionary groups had either been defeated, seceded (EPLF) or had struggled to make significant progress (OLF). The absence of a capitalist class would pose a major challenge for subsequent attempts at industrialisation (see Chapter 6). Yet, on taking power, the EPRDF faced little in the way of powerful, organised interest groups. Second, Haile Selassie and the Derg had transformed the mediated state of the past, considerably enhancing bureaucratic capacity and the infrastructural power of the state. As Christopher Clapham argued, the legacy of the Imperial regime was ‘its strength (when appropriately transformed) as a source of centralised national government’ (Clapham Reference Clapham1988, p. 4). While the bureaucracy lacked expertise and efficiency, it dominated society. In this sense, the land reforms of the 1970s and the accompanying creation of peasant associations were a defining moment in Ethiopian politics, greatly expanding state autonomy and capacity. Indeed, as with state-led development in East Asia, it is hard to believe that the EPRDF’s subsequent developmental successes would have been possible without prior land reform.

The situation facing the EPRDF was not all positive, however. The new government confronted the national question, which represented a growing challenge in light of the TPLF’s origins in just one small corner of the diverse country that is Ethiopia, as well as a growing sense of ethno-nationalism resulting in part from the mobilisation of groups such as the TPLF. This challenge in the country was replicated with particular intensity within the EPRDF. The TPLF was a revolutionary party, with all the characteristics that tend to underpin durable authoritarian regimes such as a coherent and ideologically aligned elite, strong party discipline and control over the military (Lachapelle et al. Reference Lachapelle, Levitsky, Way and Casey2020). However, in extending the conflict beyond Tigray and creating the EPRDF coalition, the TPLF incorporated three quite different parties, none of which had the same ideological alignment, a siege mentality forged through existential crisis or a solid rural base. From the beginning it was unclear to what extent these other three parties could legitimately claim to represent their ethnic communities.