Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2021

Summary

How many people have heard of Przasnysz? Probably not many. In 1914, it was a small Mazovian town close to the southern border of East Prussia. Depending on the point of view, whether Russian or German, Przasnysz was situated on one of the main roads leading to East Prussia or, going in the opposite direction, to Warsaw.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

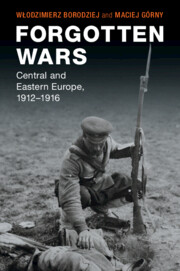

- Forgotten WarsCentral and Eastern Europe, 1912–1916, pp. 1 - 10Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021