The Swiss and German colonists who arrived in southern Bahia on the eve of Brazil's independence found themselves in the middle of a vast warzone. The Portuguese Crown had given them a land grant (sesmaria) in 1818 in what was then Porto Seguro, a captaincy of small towns and hamlets on the Atlantic frontier, worlds apart from the bustling coastal cities of Salvador, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro. The region was the field of a “just war” against the Botocudo Indians. This war, declared by the Prince Regent João VI in 1808 but long in the making, authorized the Indians’ enslavement, violent subjugation, and land seizure. Once feared and avoided by the Portuguese as savages and cannibals, the Botocudo were now seen as an infestation to be removed from an otherwise pristine, virginal terrain ripe for the taking.

Brazilian nationhood would thus inaugurate amidst the conquest of the Atlantic frontier. Spanning a vast area from the interior mountains to the ocean, these formerly “forbidden lands” may not have been the El Dorado some had dreamt of. Still, they seduced newcomers with the promise of untapped diamond mines, navigable rivers, high-quality timber, and plenty of cultivable land tantalizingly close to the ocean. European immigrants embodied the Crown's hopes of civilizing this indigenous territory with the introduction of white, free labor. The settlement, which the immigrants named Colônia Leopoldina, would play an important role in colonizing the Atlantic frontier over the course of the nineteenth century. Doubtless the settlers did not foresee the remarkable cycle of violence they would help unleash in the nation after independence, engulfing immigrants and Brazilians, Indians and blacks in countless territorial conflicts for decades to come.

By the mid-nineteenth century these European colonists would be among the most powerful coffee producers in the region. Yet their wealth was not the result of innovative agricultural technology or Indian subjugation alone. Driving their ascent was a growing labor force of enslaved Africans and their descendants who toiled daily in the oppressive heat of the southern Bahian sun to tend to the colony's vast coffee and manioc fields. The colonists’ success was enabled by the expansion of African slavery into frontier lands, where it forcefully converged with Indian enslavement, last abolished in the late eighteenth century but relegalized during the Botocudo Wars. The enslavement of black and indigenous people became foundational to the incorporation of the Atlantic frontier into the nation from which, as slaves and “savages,” they themselves were excluded.

Paralleling the violence of the frontier were the debates on Brazilian citizenship taking place in the parliament of the newly independent Brazil. The 1824 Constitution presented a remarkably inclusive, liberal idea of citizenship that extended it to Brazilian-born freedpeople. Yet its ambiguities and exclusions reflected the political elite's unwillingness to recognize Africans, Indians, and slaves as members of the new nation. To examine the constitutional debates and the territorial incorporation of the Atlantic frontier together is to see not two disconnected spheres but rather two simultaneous and confluent processes of nation-building. From its inception, the new Brazilian nation engendered exclusions in both spheres by forging a legal and physical geography of slavery and quasi-citizenship of its black and indigenous people.

“Merely Brazilian”: Early Debates and Silences on Citizenship, 1823–1824

Pedro I declared Brazilian independence in September 1822 and was proclaimed emperor in October.Footnote 1 A year later, the General Constituent and Legislative Assembly met to define the new constitution's parameters of Brazilian citizenship. Deciding who would be included within – and excluded from – the nation was no simple feat in a vast territory where political unity was far from achieved.Footnote 2 Proslavery interests also successfully maintained the trans-Atlantic trade, defeating its critics and ensuring that liberalism in post-independence Brazil would coexist with slavery. In the heated discussions, Indians and slaves became key groups through which the terms of inclusion and exclusion were defined.

The debate was unleashed by Senator Nicolau Vergueiro of São Paulo, who proposed to amend Article 5 of the Constitutional Project for the Empire of Brazil. Vergueiro suggested amending the language “[o]f the members of the society of the Empire of Brazil” by replacing “members of society” with “citizen.” He believed the change was necessary given the presence of “slaves and Indians who are Brazilian but not part of society” to whom the Constitution would not apply.Footnote 3 His view was seconded by Manoel França of Rio de Janeiro, who contended that birthplace made one Brazilian but did not automatically confer citizenship. In his view, “enslaved crioulos [Brazilian-born slaves] are born in Brazilian territory but are not Brazilian citizens. We must make this distinction: a Brazilian is he who is born in Brazil; a Brazilian citizen is he who has civil rights.” His argument extended to the indigenous people, who were also required to meet civilizational criteria. “Indians who live in the forests are Brazilians, but nevertheless are not Brazilian citizens as long as they do not embrace our civilization,” he argued, adding that “wild” Indians “in their savage state…cannot be considered part of the ‘great Brazilian family.’”Footnote 4 Both referred only to autonomous Indians. Following their arguments, Francisco Carneiro of Bahia explicitly excluded slaves and Indians from citizenship. “Our intention is to determine who are Brazilian citizens,” he began, “for once we know who they are, the others can be called simply Brazilian, for being born in the country, as slaves, crioulos or Indians, etc.” In no uncertain terms Carneiro affirmed that the “Constitution does not deal with [them], because they do not enter in the social pact.” Slaves and Indians were “merely Brazilian but do not belong to so-called civil society and do not have any rights beyond mere protection.”Footnote 5 These representatives agreed that citizenship could not be conferred by birthplace alone – the principle of ius soli. Brazilian-born slaves and Indians were excluded from its purview, the former because of their enslaved status and the latter for lacking civilization. França described these variations as a problem of the “heterogeneity of our population.”Footnote 6

If the exclusion of slaves and autonomous Indians was asserted, the possibilities for a future inclusion were left open. Brazilian-born slaves were best placed in this regard. The representatives supported citizenship for manumitted Brazilian slaves with little controversy. Scholars have noted that this support was based not on the principle of universal citizenship but rather on a liberal defense of slavery. Proslavery representatives calculated that providing libertos (freedpeople) with the possibility of individual liberty and citizenship would ultimately help maintain the existing social order of slave society.Footnote 7 The same possibilities were closed down for African libertos, whom many openly disdained. Almeida e Albuquerque of Pernambuco, for example, questioned, “How is it possible that a man without a homeland, virtue, nor customs, seized by a hateful commerce from his land and brought to Brazil, could just by virtue of his master's will suddenly acquire such rights in our lands?” He considered Africans among those who should not be given the right to citizenship since they lacked a “certain aptitude for the good of society and do not have moral qualities.” He found it unacceptable that manumission would automatically grant citizenship to Africans when Europeans were required to naturalize.Footnote 8 A striking defense of African libertos’ citizenship came from Silva Lisboa of Bahia, who squarely blamed Europeans, and in particular the Portuguese, for the slave trade. He criticized the “hateful caste distinctions that exist based on differences in color” and urged the Assembly not to promote “new inequalities” that would result from granting citizenship only to Brazilian libertos.Footnote 9 Silva Lisboa clashed with and was ultimately defeated by Maciel da Costa of São Paulo, who blamed Africans’ “barbaric compatriots” for selling them into slavery. He viewed their enslavement as a contract that Brazilians had already fulfilled, and that citizenship was not owed them. A recent governor of French Guiana under Brazilian rule, da Costa had seen up close the tumultuous events of the French colonies rippling out from St. Domingue. He argued that public security was more important than “philanthropy” and suggested that limiting citizenship to Brazilian libertos would help maintain social order by driving a wedge between them and Africans.Footnote 10

Compared to the libertos, much greater ambiguity shrouded the citizenship possibilities of Indians. First, advocates of Indian exclusion were addressing only the autonomous Indians, many of whom were being enslaved through just war precisely during these debates. The eligibility of aldeia Indians – those who had become Portuguese vassals and resided in state-sponsored villages, subject to separate laws from the autonomous – was left undefined.Footnote 11 Teixeira Vasconcellos of Minas Gerais pointed out this omission in França's earlier argument, noting that he seemingly excluded all Indians from citizenship although “they are born free and live in Brazil.” Speaking of aldeia Indians, he contended that if they are “part of the social pact, there is no reason to exclude them.” Similarly, José de Alencar of Ceará argued that “an Indian who ‘enters our society,’ savage as he is, is a citizen.” Yet tellingly, neither of these comments were followed up, perhaps based on an implicit assumption that aldeia Indians required no special discussion.Footnote 12 Second, unlike those for manumission for Brazilian libertos, there were no clear criteria according to which autonomous Indians would be eligible for citizenship. França himself suggested that “we will give them the rights of a citizen once they embrace our customs and civilization.” Francisco Montesuma of Bahia agreed that Indians could enter the “family that constitutes the Empire” as soon as they wished and suggested that the Constitution “establish a chapter that discusses the methods of inviting them into the cradle [of our society].”Footnote 13 However, the Assembly's deliberations on these matters were abruptly terminated in November 1823 when it was dissolved by Pedro I, who replaced it with a new commission that included six of the former representatives, headed by Maciel da Costa. It was they who put the final stamp on the Constitution promulgated in March 1824.

In a striking departure from the specificity in the discussions held in the Constituent Assembly, the 1824 Brazilian Constitution was both explicit and remarkably vague about who qualified as a citizen. According to Article 6, “Brazilian citizens are those born in Brazil, either freeborn or freed, even if the father is a foreigner, once he is no longer in service of his nation.” Also included were the foreign-born children of a Brazilian father, and the illegitimate children of a Brazilian mother who came to establish residence in the Empire. Finally, Portuguese residing in Brazil who had pledged allegiance to independence, as well as naturalized foreigners of any faith, also qualified.Footnote 14 Latin America's largest slave society thus granted citizenship to all free and formerly enslaved persons born in Brazil.Footnote 15

As notable as its inclusiveness, however, were the Constitution's silences. There was no mention of gender qualifications. Nor were there any racial criteria by which citizenship was made available to a Brazilian-born freedperson. Such deracialized citizenship contrasted with the race-based exclusion of native-born black and indigenous people in the United States.Footnote 16 African libertos, however, were completely excluded from the Constitution. Although they could potentially naturalize like European immigrants, they were considered stateless persons encouraged to self-deport rather than lay claim to Brazilian citizenship.Footnote 17

The Constitution also maintained a total silence on Indians. Article 6's principle of ius soli (birthplace) implied that all Indians were citizens, but the preceding Assembly debates clearly demonstrated the representatives’ consensus over the exclusion of autonomous Indians.Footnote 18 As for Montesuma's earlier suggestion that it include a chapter on methods to invite these Indians into society, the matter was discussed but ultimately voided in the final version of the Constitution, and a follow-up attempt to devise a national policy of catechism and civilization in 1826 would also fail.Footnote 19 In fact, only in 1845, when the Brazilian state had achieved greater centralization under Pedro II, would there be a national body of legislation for Indian incorporation. The Constitution therefore at best implied, but never affirmed, their inclusion. Its silence on Indian citizenship could partly be explained by the inability of representatives deliberating the matter in Rio de Janeiro to confront the diversity of indigenous groups and local laws across Brazil of which they had little experience or knowledge. But more fundamentally, a central problem in defining Indian citizenship was its impossibility – since according to the political elite's ideas about race and culture, to enter the social pact, Indians needed to be civilized, and in doing so, they were no longer Indian.Footnote 20

Their resulting omission of Indians was criticized in the frontlines. Guido Marlière, the French-born Director-General of Indians of Minas Gerais who lived among the Botocudo, decried in 1825 that the “Constitution qualifies freed slaves as citizens. But the Indians, Senhores Proprietários, born in this immense land that we inhabit, have not received this title! That is our equality!” Confusion over their status was evident in Marlière's referring to them later as “Indian Citizens” – an oxymoron in the minds of many legislators.Footnote 21

Finally, the Constitution was also distinguished by what James Holston has called its “inclusively inegalitarian” nature. It extended citizenship to many but was simultaneously predicated on the unequal distribution of rights. Nowhere was this more evident than in the absence of the word “equality.” Brazil's idea of citizenship differed fundamentally in this regard from North American and French models based on the “all-or-nothing” distribution of rights.Footnote 22 Rights were separated into civil and political rights, the latter reserved only for a few and distributed unevenly among three levels of citizens: passive citizens, active voting citizens, and active electors, the last of whom had to be born free.Footnote 23 The vast majority were passive citizens who could not vote. Brazilian libertos made some important gains, including the right to own property without restriction, maintain a family, inherit and bequeath, be a legal guardian, and represent themselves at court and before the state. However, they could vote only in primary elections and were ineligible to work as public servants.Footnote 24 The political exclusion of women was not mentioned at all, because it was so evident to legislators as to not warrant special mention.Footnote 25 Even the representatives at the Constituent Assembly who disagreed over various matters had no qualms about the inequality of citizenship itself. As Andrea Slemian has observed, the constitution was a “model of liberal citizenship that adopted, without trauma, the idea of society as naturally unequal.”Footnote 26

Inequality and exclusions, both explicit and implicit, were thus central to the definition of citizenship in the Brazilian constitution. Citizenship was constructed around not only active and passive, free and slave, but also civilized and uncivilized. All slaves and autonomous Indians were excluded from the constitution's purview because they existed “outside of the social pact.” Yet although Brazilian slaves had a pathway to eventual citizenship, such possibilities did not challenge the existence of slavery itself. This maintenance of slavery ensured its expansion in postcolonial Brazil.

For Indians, the constitution's apparently inclusive language based on birthplace and free status was deliberately silent on their eligibility. No representative affirmed the citizenship of aldeia Indians, while a cohesive set of legislations to realize autonomous Indians’ eventual inclusion was abandoned.Footnote 27 The Botocudo Wars and other offensive wars created the opening for many Indians to enter the nation as slaves, a condition that would haunt them long after the wars and Indian slavery were officially ended. This ambiguous citizenship status placed Brazilian Indians in a vulnerable, legal gray area that would effectively erode their rights and protections over the course of the nineteenth century. Like libertos given only partial or conditional manumission and threatened by a precarious hold on citizenship, Indians became quasi-citizens from the moment of the nation's birth, at best eligible for an uncertain future citizenship.Footnote 28 If state policies deliberated in Rio seemed irrelevant in a politically fragmented new nation, they would converge with war and slavery on the Atlantic frontier.

Civilizing with Slavery: The Curious Life of Colônia Leopoldina

Colônia Leopoldina's creation in southern Bahia on the eve of independence was enabled by the Crown's fusion of settler occupation with indigenous conquest. In his authorization of the Botocudo Wars in Bahia, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais, João VI had clearly stated his territorial objectives.Footnote 29 They included the navigation of the Doce River (the principal river linking Minas Gerais to the Atlantic through Espírito Santo captaincy) and special concessions to “those who want to settle those precious, auriferous terrains that are today abandoned due to the fear caused by the Botocudo Indians.” He provided generous incentives to prospective settlers, including sesmarias, debt forgiveness, and freedom from paying the royal tax for ten years. The Crown also created eight infantry divisions to protect the settlers, the Doce River Divisions, reaching from Minas to the borders of Espírito Santo and Bahia.Footnote 30 In 1811, three years after declaring the Botocudo Wars, João VI approved assistance for 3,000 colonists who had “entered in the lands free from the invasion of barbarian Indians” in the Porto Seguro captaincy. These lands which, in the language of just war, were “rescued” from the “anthropophagous Botocudo Indians” were distributed as land grants among the new arrivals. By this year, 381 sesmarias were granted in a single military district.Footnote 31

Following these grants, in 1818, the Crown began sponsoring immigrant agricultural colonies in the region in accordance with João VI's 1808 decree authorizing land grants to foreigners. With assistance from the governor of Bahia, in June of 1819 the German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Freyreiss and five fellow immigrants from Switzerland and Hamburg received their grant. A few years later they were joined by other Swiss and Germans including Jan Martins (João Martinho) Flach and Georg Anton von (Jorge Antônio) Schaeffer. They named their colony after Maria Leopoldina of Austria, who would shortly become the empress on João VI's return to Portugal and the accession to the throne of his son, Pedro I, who decided to remain in Brazil with his new consort after independence.Footnote 32 Schaeffer was a colonization agent with close ties to Pedro I and José Bonifácio, Brazil's “father of independence,” who encouraged Schaeffer to invite Germans to settle near Colônia Leopoldina.Footnote 33 Between 1818 and 1829, other immigrant colonies would be established throughout Brazil, including three more in southern Bahia; Nova Friburgo in the province of Rio de Janeiro; São Leopoldo and São Pedro de Alcântara in the nation's extreme south (today Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina); and Santo Amaro, Itapecerica, and Rio Negro in the province of São Paulo.Footnote 34

Colônia Leopoldina was located on nearly 11,000 hectares of heavily forested land inhabited by Pataxó, Maxacali, and Puri Indians on the banks of the Peruípe River, 20 miles northwest of Vila Viçosa. A natural canal linked the Peruípe to the Caravelas River and the Atlantic Ocean through a labyrinth of mangroves. Large ships arriving from Salvador and Rio de Janeiro were able to navigate this route up to the Port of São José near the colony. With the expansion of its agricultural production, the colony's relative proximity to the ocean proved invaluable for its ability sell its products to Salvador, Rio, and Europe. At its apogee, the colony would extend nearly 53 square kilometers on both sides of the Peruípe River.Footnote 35 In exchange for the Crown's sponsorship that included land, livestock, and tools, the colonists were required to observe stringent residency and production regulations. Among these, the most difficult to meet were those regarding labor. In an 1820 decree the Crown required the grantees to work half the land with the labor of their own families, and to distribute the other half among other immigrants whom they were responsible for securing. This effectively prohibited the use of slave labor. In this way the Crown asserted its intent to settle these newly acquired lands with white, free labor.Footnote 36

The spectacular failure of this racialized free labor project in the ensuing decades reveals its incompatibility with the incorporation of Brazil's frontiers, where slavery proved vital to their settlement and economic development. And if Colônia Leopoldina's transformation into a thriving slave plantation community suggested the disconnect between the central government and the frontier, and the inability of the former to extend its authority over the latter, the separation of the two was much less crystalline in practice. Even as it criticized the colony, the state took no concrete action to foster free labor in the frontiers as it ceded to profitability and proslavery interests. Colônia Leopoldina's trajectory embodied a territorial incorporation process that expanded the geography of noncitizens in the incipient nation.

Two traveling Italian missionaries had introduced coffee into southern Bahia in the late eighteenth century. By the time the Swiss and German immigrants arrived, small-scale coffee cultivation was already underway. It was only under Colônia Leopoldina, however, that it would flourish, leading to the establishment of Bahia's only coffee plantation economy, with some of the fazendas (plantations) approaching the size of the great estates of southeastern Brazil. Its coffee would command popularity in Rio and even Europe.Footnote 37 Only in the second half of the nineteenth century did São Mateus also begin cultivating coffee, spurred by the coffee frontier expanding from the Paraíba Valley farther south.

The first slaves were introduced to Colônia Leopoldina by 1824 in spite of the Crown's stipulations for free labor. While the exact reasons for this turn to slave labor are unclear, the absence of further immigrant arrivals was an important factor. The correlation of these two issues is evident in a letter addressed to Pedro I by the Swiss immigrant and Rio de Janeiro transplant João Flach, who requested royal assistance to bring more immigrants to the colony and also mentioned introducing fifteen slaves and an overseer.Footnote 38 According to B. J. Barickman's calculations, in 1820 the region as a whole had 3,529 African-descended slaves.Footnote 39 This racial landscape would change dramatically as Colônia Leopoldina overwhelmed the surrounding properties in both production and the slave population, and as São Mateus also accelerated its manioc production through slave labor.Footnote 40

Slave prices were low in the early years, their purchases facilitated by immigrant-owned and Brazilian firms that extended credit to the colonists. Some of the wealthier Leopoldina colonists would later set up their own lending businesses.Footnote 41 The uptick in the slave population soon aggravated conflicts with their immigrant masters. Many of the enslaved ran away to the sparsely settled indigenous hinterlands to establish quilombos (maroon settlements).Footnote 42 The colony experienced its first major uprising in 1832 when Schaeffer's slaves shot another planter, dragged Schaeffer's wife back to his plantation, and beat her mercilessly. The original colonists were wary of Schaeffer for leaving “his blacks in an entire insubordination, an ominous example for the blacks on other plantations.” They complained to the Swiss consul that Schaeffer's slaves, “armed with rifles, went to the Leopoldina plantations to incite the blacks there to join them and kill the whites.” Having experienced racial conflict firsthand, they were eager to discipline their slaves and discourage them from raising a “fearless hand on whites without receiving the punishment they deserve.”Footnote 43 By the 1840s, the colonists collectively owned more than a thousand slaves. Still, some of them may have admitted that such an economy was not what the Brazilian government had envisioned when it had granted them land. The real problem was not that slaves were fleeing and revolting, but that they were in the region at all.

The Crown's prohibition of slavery on these land grant colonies was founded on a specific vision of race and civilization that it aspired to realize in frontier territories. The Portuguese royals who relocated their seat of empire to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 were disconcerted by the bustling black slave society that welcomed them. While recognizing Brazil's utter dependence on the forced labor of black women and men, the royal court and the Brazilian imperial government that followed considered the sizeable African-descended population a fundamental problem. The court envisioned the empire as a homogeneous political body, and white European immigrants played a key role in its desire to facilitate the exclusion of “barbarous” African “foreigners” from participation in civil society.Footnote 44 Such racialized fears of Africans became especially pronounced in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution. In 1821 the aforementioned Maciel da Costa warned that with a racial inundation of Africans, “Brazil will be mistaken for Africa” and raised alarm about a “Kingdom of Congo” growing in its midst. Costa was confident that “it would not be difficult to increase our white population with European émigrés” and specifically promoted agricultural colonies as the best way to acquire hard-working laborers who could set an example in a society too dependent on slaves.Footnote 45

These anti-African sentiments became pronounced in the wake of the 1835 Malê Revolt in Salvador, led by Muslim West African slaves, that shook all of Brazil to its core with the fear of an African takeover.Footnote 46 That year the Bahian politician and planter Miguel Pin e Almeida, who sought to establish an immigration company, urged his compatriots to extirpate the “African cancer” and promote immigrant free labor. He explicitly linked free labor with civilization and nation-building, arguing that it was the “most solid basis for the prosperity of a new state,” the only way for converting “wilderness into cities, and forests into tilled fields.”Footnote 47 At the same time, a general population shortage prompted the Minister of Empire to encourage European immigration and Indian civilization.Footnote 48 Scholars have noted the rise of immigration debates during the later nineteenth century, when the economic and political elite of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, realizing the inevitability of abolition, advocated for European immigrants as a replacement for slave labor. However, the Crown's early prohibition of slave labor from immigrant colonies and its favoring German and Swiss immigrants indicate that by the early nineteenth century it already saw white immigration as an antidote to Africanness and slavery.Footnote 49

At the same time, the predominance of African slaves and the lack of free labor were not the only problems immigration was meant to assuage. Most of the early immigrant colonies were founded in the hinterland, where they were intended to fulfill multiple purposes.Footnote 50 First, as Colônia Leopoldina's location and period of founding attested, immigrants were above all the agents of settlement and colonization of frontier territories undergoing violent state incorporation. This included both internal and inter-imperial frontiers such as those in the extreme south.Footnote 51 Second, the immigrants served as a buffer against enemies of the state – whether hostile Indians or foreign powers, especially Spanish forces in Rio de la Plata – and offered manpower in the service of war. Thus São Pedro, Rio Negro, and Nova Friburgo were, like Colônia Leopoldina, in indigenous territory. The aforementioned Schaeffer was an immigrant recruiter who brought in Germans to serve as colonists and mercenaries, 3,000 of whom served in the Cisplatine War (1825–28) against the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata.Footnote 52 Third, immigrants promised to improve these frontier regions, which the elite considered backward, with a welcome dose of economic development and European civilization. A local judge expressed his admiration for the colony's cleared fields and orderly rows of coffee trees as embodiments of European-style progress and exclaimed, “If only all of Brazil had roads like these!”Footnote 53 Finally, João VI had envisioned making the immigrants into small proprietors who would form an intermediary class between large landowners and slaves and complement the large estates by producing for the domestic market.Footnote 54 After independence, official support for Colônia Leopoldina continued under Pedro I, who ordered the local government to assist the immigrants in encouraging the “great advantages that it could bring to the State” (Figure 1.1).Footnote 55

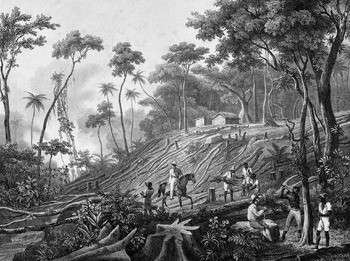

Figure 1.1 Enslaved Africans and their descendants cleared the Atlantic forest for settlements and roads connecting the interior to the coast.

Enthusiasm for immigration and economic development of Bahia's southernmost region grew as the system of slave-based production itself was increasingly cast into doubt. The 1840s were beset by economic crisis as Bahia's commerce was shaken by the ravages of the federalist Sabinada revolt (1837–38).Footnote 56 The province had lost its former trading partners during the revolt to more stable rivals. The loss also extended overseas, where Bahia found its access to West and West Central African markets cut off by the increased presence of the British in Atlantic waters as they hunted down illegal slavers, many of them headed for Brazil. Aggravating the crisis was the impending abolition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade by the Brazilian government, a measure largely ignored when the original law was passed in 1831, but now an increasingly plausible reality as British ships patrolled the Atlantic waters with greater frequency. Indeed, the Eusébio de Queirós Law of 1850 – which shifted prosecution of slave-trading from local courts to special imperial tribunals – would finally end the trade, signaling the beginning of the end of slavery in Brazil, and a crisis in all economic practices based on it.Footnote 57

By the mid-nineteenth century, the confluence of international political pressure, antislavery initiatives, and federalist strife in Salvador instigated an economic crisis in Bahia that threatened the future of African-based slavery. The dour economic climate and labor crisis made European immigrants seem increasingly desirable at the same time that Bahian state officials, eager for a solution, looked with heightened interest toward the colonization of the southern part of the province. Bahian president Joaquim Vasconcellos waxed enthusiastic about the prospects and believed that southern Bahia could settle more than 600,000 colonists.Footnote 58 His sentiments were echoed in 1857 by another Bahian president who grandly proclaimed that “casting our eyes upon the southern districts shows us that lying there, underdeveloped, are vast and rich lands between the ocean and the sertão, awash by [many] rivers…What vast grounds for a great colonization!”Footnote 59

At first glance, then, Colônia Leopoldina was exactly what the province needed: Europeans contributing to the settlement and economic development of the nation's hinterlands. But instead of enthusiasm there was growing skepticism and criticism. The problem was that Colônia Leopoldina was not, strictly speaking, a European immigrant colony. Its coffee production was doing well, President Vasconcellos admitted in 1842, but much more would be accomplished, he insisted, if all agriculture were done by free workers.Footnote 60 Five years later, diminishing the allure of the province's only prosperous colony was another president's observation that “it is a shame that all this [coffee and manioc flour] is not produced solely by free workers.”Footnote 61 An engineer assessing the lack of economic development in southern Bahia soon after the cessation of the trans-Atlantic slave trade also warned that although the colony was the region's only economic engine, its slave-based economy had only further stymied the necessary transition to free labor.Footnote 62

In short, the enlightened European colony had degenerated into a slave plantation. In 1832 Colônia Leopoldina counted 18 plantations run by 86 whites and 489 slaves. By 1858, 39 years after its founding, it was home to 40 plantations, 200 free European- and Brazilian-born residents, and close to 2,000 slaves (Table 1.1). A German physician named Karl Tölsner, who resided in the colony during the 1850s, attributed the growth of the slave population to their good treatment, a claim disputed by its Brazilian neighbors.Footnote 63 About half of the colony's slaves were African born in the first half of the nineteenth century, and were gradually superseded by Brazilian-born slaves in the second half, as the planters focused on the slaves’ reproduction to ensure the maintenance of their work force.Footnote 64 The colony's growth trajectory exposed how much the poster child of European immigration had veered off course, an embarrassment to the nation-building aspirations of the Brazilian political elite. Far from showcasing the marvels of European free labor, the immigrants comfortably delegated the backbreaking work of coffee production to their slaves. Colônia Leopoldina's economic success became a bitter testament to the fact that the conquest and settlement of the Atlantic frontier was accomplished not by European enlightenment and civilization, but by the enslaved labor of Africans and their descendants that it was meant to eradicate (Figure 1.2).

Table 1.1 Colônia Leopoldina: White and Slave Population, 1824–1857

| Year | No. of Properties | Whites/Free | Black Slaves |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1824 | 20 | 15 min. (Flach) | |

| 1832 | 18 | 86 | 489 |

| 1840 | 55 | 1,036 | |

| 1848 | 37 | 130 | 1,267 |

| 1851 | 43 | 65 “pessoas de familia” | 1,243 |

| 1852 | 54 Europeans, 400 Brazilians | 1,600 | |

| 1857 | 200 whites | 2,000 (approx.) |

Note: Numbers for Indians, settled and autonomous, were not available, although the nearby town of Prado had a 43% Indian population in the 1840s, and more individuals of indigenous ancestry were likely included among pardos (10%) and mamelucos (2%). Maria Rosário de Carvalho. “Índios do sul e extremo sul baianos: Reprodução demográfica e relações interétnicas.” In A presença indígena no Nordeste: processos de territorialização, modos de reconhecimento e regimes de memória, edited by Ana Stela de Negreiros Oliveira and João Pacheco de Oliveira. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 2011, 374.

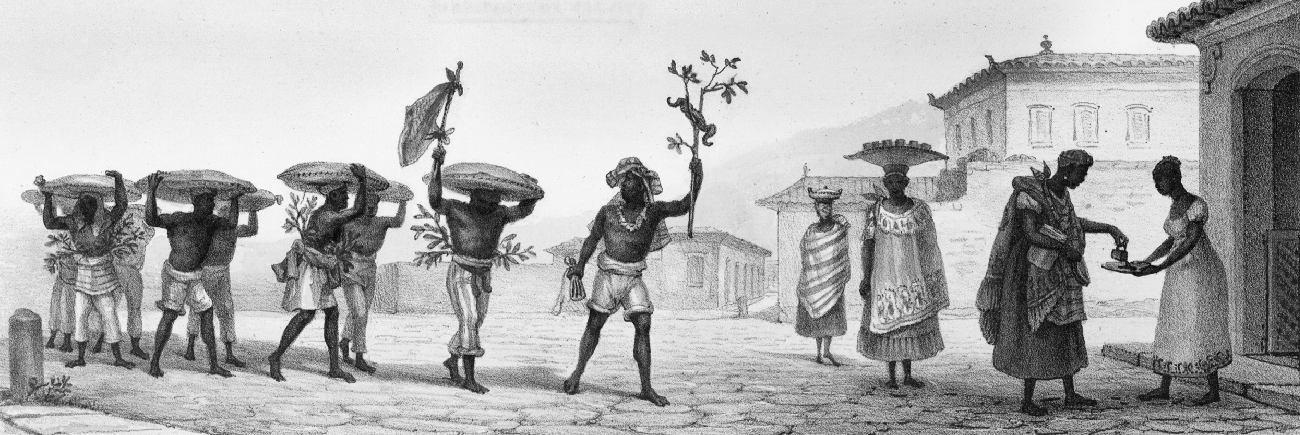

Figure 1.2 Colônia Leopoldina's coffee, produced by slaves, was shipped from a local port on the Peruípe River to the rest of Brazil and sometimes, Europe.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, public attitudes toward the colony were downright chilly, sharply contrasting with the accolades of times past. Brazilians and foreign observers alike criticized the colony for depending on slave labor instead of encouraging further European immigration. Their negative assessment remained unchanged even when the colony's coffee, known by the name of Café de Caravelas, became renowned throughout Brazil for its superior quality. The harshest critics claimed that Colônia Leopoldina could no longer be considered a colony, as it was now “inhabited by a great majority of foreigners who own coffee plantations, whose cultivation is handled by approximately 2,000 slaves.” Subsequent to these dismissals, the darling of colonization ventures, though economically vibrant, began to disappear from official government reports in a clear indication of its diminishing worth and promise.

The Swiss and German immigrants may have been content with their accomplishment: vast, orderly coffee fields tended by a few thousand slaves had replaced formerly uncultivated virgin lands “infested” with “savage” Indians. But this was undeniably far from the conception of racial and economic progress the Brazilian government had envisioned – one that, in practice, it had done little to support. In fact, a budgetary law in December 1830 had totally suspended any state financial assistance to the colonies or the introduction of new immigrants, leaving the colonists to their own devices, which the colony's critics failed to mention. Proslavery interests had likely passed the law, suspicious of free labor and of immigrant small landownership creating a class that would encroach upon their power. By taking no concrete action to discourage slave labor or provide material support for an immigrant colony, even Colônia Leopoldina's critics ultimately allowed slavery to grow.Footnote 65 Meanwhile, other early colonies around Brazil similarly stagnated, while those that thrived, such as Cantagalo and Macaé in Rio de Janeiro, had also transformed into slave-based coffee plantations.Footnote 66

Despite the colony's detractors, however, its planters remained indifferent to their fall from grace. Slave-based coffee cultivation continued. With the scarcity of free laborers and a dearth of alternatives, black slavery was the planters’ lifeline, one they would defend until the very end. They would suppress abolitionism with violence even as the rest of the nation had come to accept it. The colony was the very place where the region's legendary maroon leader, Benedito, would be gunned down on the eve of abolition after years on the run (see Chapter 5).

Examining the trajectory of Colônia Leopoldina allows us to trace the expansion of African-based slavery into the nation's indigenous frontiers, challenging a well-established idea that it extended into empty lands.Footnote 67 Its twisted journey, however, was more than just another chapter in the consolidation of nineteenth-century slave-based plantation economies, as we have seen in various regions of Brazil, as well as Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the United States. Rather, its original purpose embodied the aspirations of an emerging nation – to foster racial whitening, civilization, and colonization of the frontiers through a fusion of indigenous conquest, European immigration, and economic development. That it lasted and prospered as a slave plantation zone until the eve of the twentieth century, at the same time that a slave-owning oligarchy was also emerging in nearby São Mateus, vividly exposes how much slavery expansion was fundamental to Brazilian nation-building. It was a process that both relied on and engendered people who, as Africans and slaves, resided in but were excluded from the nation.

“Perfect Captivity”: Indian Slavery in the Nineteenth Century

While Colônia Leopoldina's immigrants pioneered large-scale, African slave-based plantation agriculture on the Atlantic frontier, another form of slavery – of Indians – was already in practice in the region. In the early nineteenth century, the conquest and settlement of these territories instigated the violent merger of African and indigenous slavery. The entanglement of these two histories of bondage compels us to question the commonplace acceptance of indigenous slavery as the “first slavery,” a colonial practice superseded by African-based slavery long before the nineteenth century.Footnote 68 João VI had justified offensive war in his 1808 declaration as the only viable option to subdue what he reviled as a hostile, “atrocious anthropophagous race.” The Botocudos’ alleged cannibalism and hostility to Portuguese rule were enumerated as necessitating violent measures, and just wars legalized their enslavement. Captured Indians, along with those “rescued” from hostile Indians, became prisoners of war who were forced to serve their captors for a minimum of ten years, and for as long as their “ferocity” lasted. It was a very convenient setup for settlers needing a labor force.Footnote 69

Indian slavery was inseparable from the clamor for territorial control accelerating in the early nineteenth century. Around the same time as the Botocudo Wars, offensive wars were also declared against the Kaingang, Xavante, Karajá, Apinayé, and Canoeiro Indians in Brazil's other frontier regions from São Paulo to Goiás, Ceará, and the Amazon.Footnote 70 For instance, just six months after he declared the Botocudo Wars, João VI authorized another offensive war against the bugre (a derogatory term denoting savages) Indians in São Paulo.Footnote 71 In southern Bahia, Baltazar da Silva Lisboa, the royal judge of Ilhéus who was entrusted with opening roads from the interior, affirmed the necessity of just war given the “projects that cannot be realized while the barbarians remain in their savage state…making necessary the use of troops accustomed to this type of war.” Writing less than a decade before the founding of Colônia Leopoldina, he optimistically observed that by subjugating the Botocudo, “the state will have power, wealth, and population, and these very fertile lands will attract many colonists, who will produce mountains of wealth.”Footnote 72

The enslavement of “hostile” Indians remained relegalized until a decade after independence, outlasting the transition from colony to nation alongside African-based slavery. It was abolished the very same year, as was the trans-Atlantic slave trade (1831), a fact little noted by scholars of nineteenth-century slavery. Portuguese law had always guaranteed the freedom of aldeia Indians, who were their allies in the colonial project. Yet it had maintained an irregular stance regarding autonomous Indians, alternately abolishing and relegalizing their enslavement. If repeated laws abolishing Indian slavery were a bitter testament to the difficulty of implementing them, the Crown's periodic reauthorization of legal enslavement derived from what it considered the impossibility of freedom for all Indians, given the preponderance of hostile Indians. Indian slavery had most recently been abolished and Indian freedom affirmed between 1755 and 1758 by the royal administrator, the future Marquis of Pombal, who expelled the Jesuits and secularized Indian administration.Footnote 73 After it was legalized anew in 1808, the total silence on Indians in the 1824 Constitution meant that the status of autonomous Indians, whom Brazilian representatives considered to live outside of the social pact, remained unaddressed, with many effectively entering the new nation as slaves. The legal ambiguity about their status would help maintain de facto Indian slavery long after its abolition in 1831, just as the trans-Atlantic slave trade to Brazil continued after the 1831 prohibition.Footnote 74

Sources abound with episodes of staggering violence against the Botocudo and other indigenous groups in the Bahia–Espírito Santo borderlands in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Prince Maximilian Wied-Neuwied, who was traveling through Brazil on the eve of independence, captured the severity of the violence when he observed that

there has been no truce for the Botocudos, who were exterminated wherever they were found, without regard for their age or sex. Only from time to time, in certain occasions, are small children spared and cared for. This war of extermination was executed with the utmost perseverance and cruelty, since [the perpetrators] firmly believed that [the Indians] killed and devoured all enemies that fell into their hands.Footnote 75

What Maximilian may not have known was that this “war of extermination” was only in its early stages. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the violence of settler expansion would combine with a complex amalgam of policies, racial theories, and science to devastate the lives of indigenous people of the Atlantic frontier.

Contrary to what this anti-indigenous violence suggests, however, Brazilian indigenous policy in the years following independence was not exterminationist. On the contrary, it was assimilationist. While the new national government would not devise a nation-wide indigenous policy until 1845, it generally advocated brandura, or “gentleness,” in the treatment of Indians even as it conducted offensive war against its enemies. In his “Notes on the Civilization of the Wild Indians of Brazil” (1823), Minister of Empire José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva mapped out a state policy, drawing largely on the late colonial policies of Pombal and based on peaceful means to civilize Indians through productive labor regimes. The “Notes” explicitly criticized the offensive wars that “in a century so enlightened such as ours, in the Court of Brazil,” had allowed for “the Botocudo, the Puri of the North, and the Bugres of Guarapava [to be] converted once again from prisoners of war into miserable slaves.” He insinuated that Indian slavery was as anathema to Brazil's progress as African slavery, an allegation that put him at odds with the nation's powerful slaveocracy. José Bonifácio envisioned the incorporation of all Indians, aldeia-residing and autonomous (along with mulattoes and blacks), into Brazilian nationhood through civilization and miscegenation. Doing so would “tie the reciprocal interests of the Indians with ours, and from them create one sole body of the nation – stronger, educated, and entrepreneurial.”Footnote 76 His homogenizing vision echoed the prevalent view, shared by members of the Constituent Assembly, that Indians did not constitute a society of their own but rather, existed outside of it. Nor was José Bonifácio interested in preserving indigenous societies or indigenous citizenship, for the goal of assimilation was for Indians to cease existing as a distinct group. As Manuela Carneiro da Cunha has noted, assimilation was not considered destructive to indigenous society, as the latter was seen as nonexistent in the first place.Footnote 77 Although José Bonifacio was driven into exile and his proposal thrown out when Pedro I dissolved the Constituent Assembly, his “gentle” approach, based on assimilation, set the tone for subsequent national indigenous policy (discussed further in Chapter 3).Footnote 78

Far away from the comforts of Rio de Janeiro, the challenges of implementing a national indigenous policy were immediately evident. An attempt to do so in 1826 failed. Meanwhile, in 1831, with the end of just war, Botocudo slavery was abolished one last time.Footnote 79 Rather than being freed, however, Indians were juridically transformed into orphans under state guardianship. Their new legal status as the nation's children placed them in a condition similar to that of emancipated Africans and recent libertos. The Justice of Orphans was responsible for overseeing them until they were deemed ready to be emancipated and enter society, meanwhile ensuring that Indians were paid for their labor and protected from reenslavement, and eventually baptized.Footnote 80 While such measures could be taken as a concrete step to begin incorporating “wild” Indians into the nation as citizens, settlers residing in the Botocudo warzone who had been benefiting from Indian slavery were threatened by this state intervention. State institutions on their part lacked the enthusiasm and funds to enforce brandura policies, all of which contributed to the collapse of Indian civilizing ventures premised on government–settler cooperation.

A case in point was the swift failure of the government-funded aldeia of Biririca in the São Mateus hinterland. Biririca's objectives were to relocate Indians onto fertile lands along the river to be trained for agricultural work, and to send them to Rio de Janeiro to serve in the navy. The Espírito Santo government, however, increasingly preoccupied with the proliferation of quilombos throughout the province, showed only lukewarm interest in Biririca. The São Mateus Municipal Chamber finally authorized its establishment in 1841 after turning down several requests to fund other aldeias. It expected Biririca to capitalize on the “daily communication that these Indians have had over nine years with the town's inhabitants, selling, buying, and working on the fazendas with compensation.”Footnote 81 However, an overall lack of government investment, aggravated by sabotage and general hostility from area settlers who saw the aldeia interfering in their access to indigenous laborers, led to its collapse by 1848. Biririca was unable to settle a single Indian, and no other aldeia was founded thereafter.Footnote 82

Differing conceptualizations about indigenous labor held by the state and frontier settlers exposed the fragilities of Indian citizenship. The state viewed labor regimes as a means to civilize autonomous Indians by transforming them into a settled, productive peasantry to prepare them for eventual citizenship. On the other hand, many settlers, particularly those without access to black slaves, simply coveted servile workers and had no qualms about enslaving Indians. The Brazilian government allowed Indians to work for individuals under a contract in the Regulation of Missions (1845), its one major national indigenous law of the nineteenth century. But leaving the contracts in the hands of private citizens ensured that much of the labor effectively went unremunerated. Many settlers “paid” Indians with cachaça, a sugarcane-derived spirit, which contributed to the spread of alcoholism.Footnote 83 In fact, another reason for Biririca's failure owed to the state's attempt to resettle indigenous families there and prevent them from going to individual properties, where they risked reenslavement and abuse.Footnote 84

However, settlers were not the lone enthusiasts of Indian slavery. The state's reticence about Indian citizenship and lack of a cohesive civilization plan translated into an ambiguous indigenous policy that was officially “gentle” yet simultaneously condemned and enabled Indian slavery.Footnote 85 During the Botocudo Wars, captured Indians were turned over to individual settlers for a minimum period of ten to fifteen or, if they were children, twenty years. The settlers were responsible for feeding, dressing, educating, and Christianizing their slaves in exchange for their labor as a way to prepare them for eventual participation in society as full citizens.Footnote 86 Indigenous slavery thus had a perversely pedagogical objective that linked government and individual interests. Unsurprisingly, pedagogy was not foremost on anyone's agenda. The French traveler Auguste de Saint-Hilaire noted that settlers used this promise in order to trick the Botocudo into giving up their children, whom they sold for 15 to 20 mil reis. Government officials also lent each other Indian laborers who had to clear roads through what had been their own lands to facilitate settlers and commerce. The president of Espírito Santo was particularly eager to “borrow” indigenous laborers from Minas Gerais since it was “difficult, if not impossible, to find free day laborers or slaves to work in these far flung locations…For now we can only count on Indians.”Footnote 87 After the abolition of Indian slavery in 1831, as we have seen, these enslaved Indians were transformed into orphans under the guardianship of a judge. The judge possessed the power to distribute them as free laborers to those in his sphere of influence. Many judges abused this privilege liberally, amassing great personal wealth.Footnote 88

This slippery slope of state-sanctioned Indian civilization and slavery created many opportunities for abuse that lasted long after Indian slavery was officially abolished. Particularly appalling was the enslavement and trafficking of Indians, especially their children, who were known as kurukas.Footnote 89 Saint-Hilaire aptly decried that “in Brazil was repeating what happens on the Coast of Africa: tempted by the prices that the Portuguese paid for the children, the Botocudo captains fought one another to obtain children to sell.” The demand for kurukas profoundly destabilized intra-indigenous relations. For example, two Botocudo groups in northern Minas had been nearly annihilated by wars to obtain kurukas for the Portuguese.Footnote 90 Kuruka slavery also touched many other indigenous groups, aldeia-residing and autonomous, with more than a few settlers intentionally mislabeling their victims as Botocudo in order to justify their enslavement.Footnote 91 Little is known about kuruka slavery in nineteenth-century Brazil, partly due to the sparse attention given to indigenous slavery during the Empire, but also because of its smaller numbers and extralegality. Unlike African slavery, which has produced volumes of registries, bills of sale, and inventories, kuruka slavery suffers from a dearth of documentation. Nonetheless, kurukas appear in the historical record frequently enough to force us to question what this slavery reveals about indigenous people's status in postcolonial Brazil.

Kurukas were employed for a variety of purposes. The majority were captured, traded, and used by unscrupulous settlers as domestic servants and farm laborers and at times to harvest the prized jacaranda wood. Some wealthy individuals considered them a sign of social prestige and gave each other kurukas as favors and gifts. Soldiers in Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais “gifted” seven Botocudo kurukas to Pedro I in the early 1820s to be educated in the schools, which Marco Morel has identified as slavery, since the children were owned by soldiers who had attacked and killed their parents.Footnote 92 Children were generally preferred to adults because of their supposedly greater propensity toward assimilation. Even Saint-Hilaire, who vocally denounced kuruka slavery, was determined to obtain his own Botocudo child. His repeated requests were refused by the cacique (indigenous leader) Johaima, who poignantly told the Frenchman that the “Portuguese took almost all our children, promising us they would return, but we never saw them again.” When Saint-Hilaire insisted, Johaima evoked the Portuguese lexicon of Indian civilization to deflect him, stating that “since we would like to cultivate the earth, we couldn't dispense of our children.” He added that the whites had enough women to give them children, and that they “didn't need to come looking for Botocudos.”Footnote 93 Saint-Hilaire was not the only white person who had difficulty comprehending why Indians did not want to give up their children. A Portuguese director of Indians who marveled at their capacity to mourn the loss of children remarked, “One cannot remove a single child from them because as parents, although savages, they adore their children as much as we do.”Footnote 94

Especially problematic was the state's involvement in kuruka slavery. Children on aldeias were nurtured to become go-betweens to assist in bringing autonomous Indians into Portuguese villages. In Espírito Santo, indigenous families protested their children's being sent away to serve in remote regions by claiming that they were “national Indians” and thus citizens (a rare, valuable instance) and should be exempt from such treatment. An even more troubling example was the Director of Indians of said province, who regularly coerced aldeia Indians to give up their children, including boys as young as eleven and girls as young as three. He liberally distributed seventy-two kurukas to prestigious persons in 1834, arguing that it was the best means to transform “wild animals” into a “useful population that this province needs.” Sexual abuse was likely.Footnote 95 Finally, in its worst iteration, settlers massacred entire Indian villages and seized their children in a practice known as matar uma aldeia, which Chapter 4 investigates in depth. These repeated examples of Indian slavery on the Atlantic frontier, sometimes illegal and other times disguised as tutelage, all point to the de facto lack of legal protection for Indians and the inability and unwillingness of the state to curtail the practice when it was not itself participating.Footnote 96

That said, some Indians also entrusted the care of their children to missionaries and settlers and were not strictly victims of slave raids or coercion. Paraíso has argued that the Indians did this out of poverty, the desire for objects, and a lack of perspective about the future. The aforementioned Director of Indians especially targeted orphaned children whose relatives were more inclined to give them up in exchange for objects.Footnote 97 The US traveler Thomas Ewbank was horrified to encounter Indian mothers from drought-stricken Ceará in Rio de Janeiro selling their sons to the navy in desperation. However, sending their children to outsiders was also an important means for Indians to negotiate their survival amidst growing settler occupation. They “offered their children to captivity” under local settlers in order to secure themselves against raids, appease hostilities, and establish strategic alliances and patronage protection. For example, the Botocudo of the Mucuri River Valley “gifted” several kurukas to the mineiro (from Minas Gerais) senator Teófilo Ottoni, who was seeking to establish himself in their lands. They told him that the purpose was to ensure that Ottoni “remained tame,” another instance in which the Botocudo manipulated the Portuguese lexicon of Indian civilization.Footnote 98 In Bahia and Espírito Santo some Indians worked sporadically alongside black slaves but sold their children to local settlers. Among them were the residents of Colônia Leopoldina, where many Botocudo came to seek refuge from other settlers, sometimes requesting baptism as a way to cement their alliance. A few Indians had even become peasants on the colony's lands.Footnote 99

Even so, the precariousness of these alliances was exemplified by an incident at São José de Porto Alegre south of the colony, where kuruka ownership was common. A group of Indians residing in the interior had been selectively sending their youth to the hamlet's missionary and settlers until the latter, coveting the financial rewards promised by their kuruka-seeking neighbors, invaded the Indians’ settlements and seized their children, destroying the burgeoning alliance. The next year, a resident of the same hamlet massacred a group of fourteen Botocudo headed by a leader identified as Jiporok, in retaliation for his killing of a local family. Widely reported as the epitome of Botocudo savagery, Jiporok's attack had in fact been motivated by the family's kidnapping of his own children.Footnote 100

Indians were also trafficked in an interprovincial trade. The concentration of documents denouncing Indian slavery and trafficking in the mid- to late-1840s suggests that they were not immune to the scramble for slave labor sparked by the impending prohibition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1850.Footnote 101 Children and adults were enslaved and sold as far as Rio de Janeiro. The Indian slave trade has been nearly invisible in the history of nineteenth-century Brazil, since the number of trafficked Indians was likely minuscule compared to that of black slaves. There are no comprehensive numbers available beyond the estimated 600 to 700 Botocudo dispersed among three towns in northern Minas in the 1820s; 72 sent away by the Espírito Santo Director of Indians in 1834; and the 52 held privately without a contract in Rio de Janeiro in 1845.Footnote 102 Thomas Ewbank was startled to learn that “Indians appear to be enslaved as much almost as negroes, and are bought and sold like them” in Rio as late as 1845.Footnote 103 The same year, a decree demanded vigilance for children destined for other provinces without evidence of a contract or consent from their parents or guardians. The shipping of an indigenous woman from São Mateus to a resident in Rio de Janeiro also sparked concerns about the trafficking of Indians to private citizens for whom they worked without a contract. The city's Justice of Orphans expressed concern that these Indians, taken advantage of for their “natural simplicity,” were held in a “quasi perfect captivity.”Footnote 104 Two years later, the president of Espírito Santo cautiously praised the economic progress of São Mateus, noting how its planters had “managed to domesticate the Botocudo and employ them in their agriculture in exchange for sustenance and clothing.” He nonetheless remained wary of illegal enslavement and advocated establishing government-funded aldeias as a way to keep tabs on Indian laborers and the individuals they served. The plan never materialized.Footnote 105

Kuruka slavery, like that of Africans illegally brought to Brazil after 1831, was an open secret. When the issue surfaced again in 1841, the Espírito Santo president showed no surprise but lamented that the “barbaric and abominable custom of buying wild Indians from the forests” was still in effect.Footnote 106 The Justice of Law in São Mateus was one of the few who did contest the practice, seeking to prosecute Indian enslavement as a violation of Article 179 of the Criminal Code that criminalized the reduction of free people into slavery. Yet he also claimed that the Indians were coming to settlers’ homes of their own free will without coercion, contradicting his acknowledgment that their living conditions were increasingly dire. Beyond the disingenuous insinuation that Indians were willingly enslaving themselves was the harsh reality of disappearing lands and livelihood, rendering them ever more vulnerable to captivity.Footnote 107

Legally speaking, indigenous and African-based forms of slavery were not identical. Among Brazilian-born blacks, slavery was an inheritable biological condition before the Free Womb Law of 1871, while Indians legally became slaves through capture in just war but did not inherit their condition. Black slaves could potentially purchase their freedom or be manumitted, but no such options were available for Indians, who were held in captivity for the royally designated period or until they were “civilized,” a completely subjective condition.Footnote 108 Yet to examine the process of frontier settlement is to see how these two forms of slavery overlapped temporally, geographically, and experientially. Black and indigenous people shared the devastating experiences of enslavement, sales and trafficking, forced migration, and the rupture of families. Even if Indian slavery sometimes assumed the guise of contractual labor or tutelage, the actual experience was often one of “perfect slavery.”Footnote 109

As the new nation grappled with the challenges of extending its sovereignty over its vast domain, frontier settlement gave concrete form to the exclusion of black and indigenous people. African-based slavery, not free white labor, drove the process, fusing with and accelerating Indian persecution and enslavement. Frontier settlement and incorporation thus relied on the deliberate creation of people who were “outside of the social pact” and whose existence was yet embedded in the very construction of a liberal Brazilian citizenship.

Black and indigenous people's enslavement also exposed the ambiguity of citizenship and its precondition, freedom. For if both African and Brazilian slaves were legally entitled to a future manumission, that possibility was contingent on the master's will or on the slave's ability to self-purchase. Neither was widely available where labor was scarce. Furthermore, as Sidney Chalhoub has shown, African and native-born slaves and freedpeople in nineteenth-century Brazil were subjected to an abundance of conditional manumissions, revocations of freedom, and restrictions to full citizenship.Footnote 110 So while Africans were actively discouraged from becoming citizens, even Brazilian libertos discovered that their access to citizenship was ominously elusive, always threatened by the potential to be trapped in a purgatory of “half-freedom,” or worse, to fall back from citizen to slave.

The precariousness of freedom also threatened indigenous lives. One who perceived it was Manoel Mascarenhas, the Espírito Santo president, who decried the deleterious effects that child trafficking had on Indian civilization. He presumed the Indians would prefer to live in the hinterland where they maintained their freedom, rather than enter the “cradle of society” where they witnessed their children being reduced to slavery by people who were “free like them.”Footnote 111 That Indians entered Brazilian society as slaves casts a harsh light on a central question. Were Indians free? And if so, were they citizens? By 1844 when Mascarenhas spoke, there was no legal Indian slavery in Brazil. It continued brazenly in practice, however, sometimes assuming the guise of tutelage or informal labor arrangements. Their “perfect” enslavement exposed just how imperfect were the laws governing Indian citizenship, which remained as ambiguous as it was in the 1824 Constitution. The Swiss naturalist J. J. von Tschudi succinctly captured the problem when criticizing the war of extermination against Indians in the Mucuri Valley, which was continuing “in spite of the beautiful, but unfortunately defective Brazilian Constitution.”Footnote 112

To say that in Brazil's early postcolonial decades the state had no bearing on events on the Atlantic frontier is to ignore the ways in which Brazilians, from the national political elite down to the local settler – whether through indifference or direct involvement – allowed slavery, legal and illegal, to propel its settlement and incorporation. Fears of an African Brazil and praise for the civilizing promises of white immigrant labor translated into no material support for Colônia Leopoldina, whose transformation into a slave plantation the state, noting its profits and ceding to proslavery interests, criticized only from afar. Having maintained offensive war against “hostile” Indians, it did little to enforce the abolition of Indian slavery and sometimes participated itself. State and frontier thus converged, ensuring that the inequalities and exclusions of Brazilian citizenship reproduced themselves through the creation of slaves and quasi-citizens who resided within, yet did not have the rights to, Brazil's national territory. How black and indigenous people experienced and interpreted these terms of their inclusion and exclusion and sometimes articulated their own terms, is the subject of the next chapter.