1933–1934: The New Reality

During the first year and a half of Nazi rule, the agrarian world was in a state of flux. Surprisingly, there was initially room for dissent, as we will see both in Sering’s publications, as well as in the pages of AFK. In fact, for the first six months of the Nazi regime, the classic inner colonizers had a staunch ally in Hitler’s cabinet, as Hugenberg was the Minister for Agriculture. A man who will be featured prominently in this chapter, Sering’s all-time archenemy Richard Walther Darré, had expected to be given this position but had to instead stew for six months while Hitler appeased Hugenberg’s DNVP. An article appearing in AFK entitled, “What Should Agrarian Settlement Expect from Hugenberg?”Footnote 1 assured readers that they had nothing to fear from the famous industrialist, as his incredibly long (especially prewar) history with inner colonization was impeccable. Indeed, during his six-month tenure Hugenberg did attempt to place the agrarian sector at the center of the German economy, but he did not share the extreme racist goals of Darré and was constantly at loggerheads with him. When Hugenberg resigned in June, both his career and the DNVP came to an end.Footnote 2 Hugenberg’s, and indeed most inner colonizers’, misunderstanding of Nazi settlement thinking was that while they, the moderates, believed that the land was as important as the Volk, Darré simply saw the land as the setting, and in some ways the engine, for the creation of the Bauerntum, the new racially pure peasantry. As opposed to soil and vegetables, Darré thought only in terms of human breeding.Footnote 3 He was, however, still an agrarian romantic. Even though Darré’s purely racial approach would logically produce an egalitarian German population, a “Master Race” (Herrenrasse), he believed in a heroic peasantry ruled over by a Herrenschicht, a class of lords, not so dissimilar to the medieval village that existed in Sering’s mind.

Darré’s thinking was well known via his previous publications,Footnote 4 and there were early attempts by agrarian moderates to temper his ideas. A month after Hitler’s ascent, Sering gave a speech at an agrarian conference for the Friedrich List Society in Bad Oeynhausen. He was well aware of Nazi thinking, and that Darré was in the audience, when he walked through three issues. First, he addressed (then quickly moved on from) the “racial political historical viewpoint,” arguing that, despite centuries of movement from the land to the city, Germany still possessed a strong reserve of peasant stock. This was unlike what he, Sering, had witnessed the previous Fall in England where their version of a “Reich Settlement Law” had been a complete failure and the land was still empty.Footnote 5 He then moved on to his next theme, “Eastern Border Protection,” an old favourite and an outlook that he enthusiastically shared with the National Socialists. Yet his discussion of it pre-emptively attacked the hereditary, racially based, semi-feudal inheritance law that Darré had been publicly formulating, in which only one member of the family would inherit the farm. Sering insisted that the existing farming situation, where all family members had a stake in the property, led to early marriage and lots of children. Such an inheritance situation should remain at all costs, Sering argued: “It’s about the existence of Germanness in the East, it’s about the survival of the Reich.”Footnote 6 Finally, Sering turned to the problem of six to seven million unemployed people and how inner colonization could solve this problem. But to do so, the new regime needed to carry out what had already been agreed to in his 1919 law, the expropriation of a third of the large landed estates. And to counter any claims that this was somehow illegal, Sering made the incredibly bold statement: “in the Middle Ages peasant property was forcibly confiscated or bought by the Junker. In that regard, it is therefore an act of restitution.”Footnote 7 Sadly, Sering complained, the Osthilfe program had kept alive many Junker estates, and should surely now be suspended. Here Sering drove home his anti-Junker argument, describing how he had visited giant farms in the American West in 1930, and had seen the results: a vast expanse of land with very few people.

This pre-emptive strike against Darré’s plans continued in the pages of AFK, initially with a contributor who later supported the Nazi position. Max Stolt’s article, “Future Settlement and the Most Appropriate Legal Reforms for its Practitioners,” completed its brief history of inner colonization by pointing out that it had fared worst when the hand of a controlling government was heaviest, a direct reference to Darré’s preparation for massive state intervention. He then mischievously invoked the Führerprinzip, that agrarians knew the will of the leader, and therefore they understood best how to carry out his principles. The journal carried a long quote from Wilhelm Kube’s “Eastern Questions and National Socialism,” that stated that the importance of eastern colonization was not in itself “anti-Junker,” but that there was nevertheless little need for large latifundia.Footnote 8 Meanwhile, however, the future historian of inter-war agrarian settlement, Wilhelm Boyens, penned an article that acknowledged the power of a National Socialist agrarian policy, noting that flight from the land was now being caused by heavy indebtedness and this debt quite simply needed to be forgiven.Footnote 9 Indeed, this was exactly what Darré was mooting at the time and would implement.

By the summer of 1933, Sering was heavily involved in organizing the hosting of a major international agrarian conference at Bad Eilsen, and in late June reached out to the new Reich Minister for Food and Agriculture Darré, inviting him to attend.Footnote 10 In an obvious effort to get Darré on his side, Sering followed up with a gushing letter in early July, telling Darré how pleased he was that the Ministry was in the hands of someone who understood how important farmers were. Sering then declared that he would be giving up his scientific life’s work, his leadership of this conference, and his involvement in the GFK, now that he knew agrarian settlement was in such good hands.Footnote 11 Darré responded that, although he would not be able to make it to the conference, Sering should be assured “that it is for him a great pleasure to know that in the future they can work together hand in hand on the question of settlement.”Footnote 12 This seemingly happy exchange ended with Sering informing Darré that, sadly, due to the economic crisis, it had become impossible for their American colleagues to make it to Germany, so the conference would be postponed for a year.

Sering’s real thoughts about what was happening to his world in Germany can be found in a letter he wrote to the English agronomist Leonard K. Elmhirst, in late November. He noted that, although they had had to suspend the conference this year, it was crucial that it go ahead the next year:

Since the War an increased feeling of nationalism spread throughout the world. Herein lies the danger of the destruction of ideals with which mankind has long been concerned. I am deeply convinced, that it is not only our duty to represent national interest but also those of humanity and the unity of mankind. There is perhaps no organisation which is more fitted to foster the interest of humanity than our own, because we are united by science, the systematic exploration of truth. In this respect the single scholars do not only depend on one another, because their works are complementary, but the more we obtain a profounder recognition of the decisive causes of economic developments, the more the conviction grows that the well being of a single nation is dependent on that of all the others.Footnote 13

Reichsbauernführer Darré and Extreme Inner Colonization

The law that Darré introduced at the national level in September 1933, the so-called Erbhofrecht, or Law of Inheritance, was nothing short of the firmest answer to central problems that had been in the mind of Sering and all of inner colonization from the start: how do you give land to a peasant family and then stop them from selling it? How do you stop speculation? How can you entail peasants while pretending you are not recreating serfdom? Darré created an inheritance structure that made it virtually impossible for a majority of farmers to sell.Footnote 14 Further, the law allowed the state to remove a farmer if he was found to be “dishonourable” or “inefficient,” for, as Darré pointed out, the individual’s needs did not outweigh the needs of the race. And, in a move that had no historical precedent (as Sering would point out), in certain circumstances, the inheritor of the farm was to be the youngest son, not the traditional first born.Footnote 15 Cabinet members spoke up, exclaiming (correctly) that this amounted to something akin to feudalism. At this early stage, Darré had the backing of Hitler, and at this moment the Führer declared that such a law was indeed the only way to stop speculation. Darré thus got his way. Fascinatingly, powerful economic arguments that such small estates would not increase food production were dismissed by Darré, for this plan to maintain the small peasant on the land at all costs was deemed necessary for the future of the race. That nation/race was more important than pure scale economics had long been accepted by the most moderate of inner colonizers. Darré argued that such an approach was neither socialism nor capitalism. Again, at this point, such extreme focus on agrarian human breeding was approved by Hitler and would only become a problem when Darré insisted that there be no expansion of the borders in the East, for there was more than enough racial work to be accomplished within the Altreich. In some ways, this was a new version of the empty/full arguments surrounding space, already seen in the First World War. Whereas Kaiserreich inner colonization required new land to escape the obstacles they encountered within Germany, for Darré, there was no need to “escape” the confines of Germany, as the Nazis could simply remove any obstacles, legal or otherwise.

Of course, Sering and his fellow travellers had always claimed that inner colonization was above any mere definition as socialist or capitalist. While he, and the likes of Max Weber, had insisted that it was instead nationalist, that term was now simply replaced with a more abstract racial notion, yet the sentiment was similar. Darré’s new law stated that any farm large enough to sustain a family was to be included in the strict inheritance system. But whereas “national” had always been squishy among the pre-1933 thinkers, now Darré was able to bring racial selection directly into play regarding who could receive or retain land. Using figures that should have pleased the Junker-hating Sering, Darré’s settlement office projected settling 1.5 million ha with 90,000 new holdings, which was exactly the amount of land made up by farms over 100 ha, that is, large estates. Indeed, Darré and the influential Nazi racial thinker Alfred Rosenberg spoke openly of the “twilight of the Junker,” a class to be replaced with the blood and soil of peasants.Footnote 16 The Nazis hated that the Junker used foreign labour, and they, along with Junker allies like President Hugenberg and Conservatives in general, were all deemed to be unreliable. Hitler was sympathetic to these anti-Junker sentiments but, ever the political schemer, he knew that his Wehrmacht generals were for the most part raised on these landed estates and he would have to put up with them for a while.

Resistance from the Old Inner Colonizers

Darré’s new law, the Erbhofrecht, was initially put forward at the provincial level, for the state of Prussia, and this version was printed in the AFK in mid-May 1933. After it had become law and the idea of a national Erbhofrecht was being pushed, the issue was actually debated in the pages of the journal by Darré and Hugenberg. Darré put forward his position that this was the best way to control a form of settlement that was not “at any price” (by disallowing speculation), and yet would last. Hugenberg responded that he was happy with traditional Laws of Inheritance (Anerbenrecht) and he was against the state having too much control over the lives of farmers’ families. Another contributor was critical of a law that was supposed to create a true “land of peasants” (Bauernland) yet allowed for the continued survival of the Junker.Footnote 17 The Nazi-leaning Boeckmann then claimed that the relationship of the state to the peasant was outside any liberal system, that it should largely be outside any money scheme, and that the Reich should pay for peasants to stay on the land.Footnote 18 Even after the national law had passed in September, critique was sustained in AFK, with Wilhelm von Gayl and others attacking Boeckmann’s ideas. In the last issue of 1933, an article about how to find good settlers was so critical of pre-1933 inner colonization that the editors intervened with explanatory footnotes. The first footnote challenged the assertion that postwar settlement was controlled by Marxists. Sure, the editors admitted, there were some Marxist influences in the government, but such a statement was very unfair, especially as the people being slandered were the editors!Footnote 19 The same December 1933 issue announced that the journal, currently on volume 25, would be renamed in January. In a highly symbolic move, the title that focused as much on land as people, the Archive of Inner Colonization, would now be changed to directly reference Darré’s prime consideration, Neues Bauerntum, or New Peasantry (hereafter NB). In an editorial, the journal editors stated that the old title was too difficult to say (true) and used foreign words.Footnote 20

Throughout 1934, NB described the new orthodoxy in articles like “Fundamental Questions of National Socialist Farmer Politics,” which stressed “blood” and the Germanic roots of rural settlement in Germany.Footnote 21 The international flavour of AFK was maintained, however, with an article on the first 10,000 Japanese reservists sent to settle in Manchuria.Footnote 22 A more sinister “international” flavour appeared in the small notice, “Settlement of Jews from Germany in France?” which remarked on the Jewish Press’s concern over the national revolution, arguing that it was time to go, for now, to southern France. Was this to form a colony there, the editors asked, or merely a stopping point on the way to Palestine or Argentina? They did not know.Footnote 23 Also, in 1934, there emerged a new and serious interest in “Raumordnung,” the study of the physical space that Germany took up in Central Europe, and the question as to whether or not there was enough of it. In his May article, “The Organization of Space (Settlement Planning) in the Service of the Regeneration of German Farmers,” Carl Lörcher claimed that, although Germany currently did not have “enough” Raum, for the time being it had to focus on thickly settling what it did currently possess, especially in the threatened East.Footnote 24 The 1935 article, “Regarding the Question of Raum in German Settlement,” complained that Germany had lost twenty-seven million souls to overseas emigration, before claiming that there was currently more than enough Raum within Germany for big, healthy new German families.Footnote 25 By 1937, the work of Konrad Meyer, the ultimate Raumforscher (spatial researcher) would regularly appear in NB.Footnote 26 But the newly renamed journal did spend some time reflecting upon and thanking the now dissolved GFK. Since the Reich itself oversaw inner colonization, there was no longer any need for the Society, and the editors thanked the major players for their work, including Sering, but noticeably failed to mention the already persona non grata, Hugenberg. In fact, in the detailed history of the GFK that appeared in the pages of NB in 1934, Sering was heavily praised. But this would be the last moment of such reverence in this journal, as Sering was also about to become an unmentionable.

Sering Breaks with Darré

Sering’s daughter lived with her family a short walk away from her father in Dahlem, and every Sunday she would set out from the von Tirpitz household with her youngest son (Wolfgang, born 1933) to walk to the famous home (and Sering Institut) at Luciusstrasse 9 for dinner. About halfway along the walk, at Am Hirschsprung 44–46, she would stop in front of an imposing, gated mansion, turn to little Wolfgang, and exclaim, “This is the house of the enemy of your father.”Footnote 27 It was the house of Darré. In the initial stages of their relationship, Sering was diplomatic toward Darré, as was clear in the earlier cited letter exchange about the conference. Sering and Darré had still shared the stage as late as June 1933 at the GFK conference, which was held after the Prussian Erbhofrecht was in place. But by early 1934 Sering believed it was time to make his problems with a state-controlled, racially based system of agriculture more widely known. He wrote, but initially did not publish, a fifty-page memorandum entitled “The Right of Inheritance and Debt Relief: Legal, Economic, and Biological Aspects.”Footnote 28 He began by arguing that Law (Recht) was indeed very important and had been a crucial part of the history of the peasantry.Footnote 29 Fundamental to that legal history, and what had now been rejected with the new law was that peasant families had always decided to whom the inheritance would go, and they had decided whether to perform a wholehearted Anerben, or the more equitable Realteilung, ceding the entire farm to one heir, or dividing it among the children. Now, with the new law, it was the legal authorities alone that made these ancient and traditional decisions. Then, in an interesting move to fight the anti-liberal Nazi fire with his own, Sering made the following argument: when the state intervened within what is the most fundamental cell of the state body, the peasant family, it was breaking up that cell into something to be controlled by a bureaucracy, an insidiously “liberal,” “individualizing” move. Sering then undertook to dissect the motive for all of this, which he rightly stated to be Darré’s desire to make the peasantry the blood source of the race. But, argued Sering, while the peasants had been the soldiers (Kampftruppen) of the early National Socialists, these new policies had now sapped them of their energy. The new law created “grotesque” situations, such as the case where the desire to have the farm in the hands of the strongest and longest yet to live farmer resulted in the youngest son inheriting the farm. If he had no cash on hand to pay off his siblings, one could foresee circumstances where the oldest son now served the youngest. Sering finished by again using Nazi racial logic to attack the very same: after citing Hitler and Erwin Bauer on the importance of avoiding “degeneration” at all costs, Sering claimed that the biological impacts of the new law were such that unhappy families were forced to have only one child, for this was the only security in controlling their own family’s inheritance.

In early February 1934, Sering wrote to Darré to inform him that he simply could not agree with Darré’s Erbhofrecht. Sering offered ideas that would bring it more squarely in line with traditional Bauernrecht, peasant law. He enclosed his recently written memorandum with the letter and asked Darré to please have a look.Footnote 30 Sering ended the letter by confirming that the previously delayed international agrarian conference was now definitely going to take place. No invitation was extended. Darré responded back in a letter to the doyen of agrarian settlement with the rather dismissive claim that he rejected Sering’s “purely economic” reasons against Erbhofrecht, and that, due to their “fundamentally different starting points,” it did not make much sense to continue to argue about it.Footnote 31 At the same moment, Sering sent Goebbels a notice that he had provided Darré with a memorandum highly critical of entailment and that it was here attached, should he be interested. Walter Funk, Goebbels’ state secretary, responded that the Reichsminister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda had read it with great interest.Footnote 32 Before Darré had even received the memorandum, he had his henchman, Herbert Backe, write to Sering on January 27, informing the professor that his institute would no longer be funded, as this was only causing a “fragmentation” of research, and that Sering’s work was now redundant in the wake of the successful revolution.Footnote 33 Sering promptly wrote to Reich Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, claiming that the recently deceased Professor Erwin Bauer had promised that Frick would allow good research to continue. Apparently, Frick relented. The institute stayed open for the time being.Footnote 34

In any case, Sering had already let loose the dogs of war. His colleague Hjalmar Schacht, President of the Reichsbank, and soon to be Minister of Economics, had financed the printing of 100 copies of this memorandum, and Sering had distributed them to anyone he thought might be interested. It was not long before some of them slipped out of the country to be read and eventually reported on by the foreign press. Darré was furious. In June 1934, Darré had Der Stürmer print an article “outing” Sering as a “half Jew” who personally disliked the law as it prevented “Mischung,” the mixing of races. Darré then directly asked Hitler in late June to please cancel the big upcoming conference. Hitler responded that for “diplomatic” reasons he simply could not.Footnote 35

1934 Primer for the Conference

While under assault for his attack on Darré, Sering continued to organize the major conference to take place at Bad Eilsen in September and managed to put together and publish a large tome to act as a primer on all things German for those attending the conference.Footnote 36 In the second chapter, on the history of agriculture in Germany, Sering did not hesitate to once again critique those currently running the show. After a nod toward race, including that it was in fact “Indo-Germanic” for the eldest son to inherit the father’s house,Footnote 37 Sering agreed with the Nazis that the reforms of the early nineteenth century, the introduction of capitalism into land ownership, had indeed “mobilized” the land in ways that hurt the peasantry. Then, in what would have been unsurprising to most (and music to Nazi ears), he stated that the World War was “a war of the land-rich versus the land-poor peoples of Central Europe.”Footnote 38 He then used his reverse-colonial rhetoric to state that the experience of Germany under the Versailles Diktat had been akin to how the old Kulturvölker used to treat people of colour. But, all this agrarian history was discarded, claimed Sering, in the new Erbhofrecht, an ahistorical law that had as its sole focus an abstract idea about what an ideal peasant should be.Footnote 39 Although the Prussian Settlement Commission had been expensive, Sering admitted, its results, he surprisingly claimed, were stellar. At the cost of half a billion marks they had settled 21,749 families on 309,139 ha of land. He then argued that, since 1919, the settlement work had continued, and that garden suburbs were now also a key feature. In a hint that Sering no longer believed in the Nazi ideal of autarky, he claimed that this blending of industry and agrarianism was crucial, as Germany was “weak on raw materials” and would forever need healthy trade. But this Weimar period of settlement was not yet over, Sering claimed. He then quoted some of Darré’s rants about Jews and how capitalism needed to be removed from the agrarian sector. To this, Sering responded that, instead, unfortunately, the agrarian sector had now been made socialist. Sering registered his astonishment at how much had changed so fast. In one year, one man, Darré, had changed everything.

What Sering surely did not want to admit was that Darré and his racist colleagues had almost managed to cancel the conference. A letter that Sering received in early March from the Reich Food Office (Reichsnährstand) informed him that they had only just been made aware of the conference and that they must know exactly who would be representing Germany, as no international conference could now be held in Germany “without the competent and responsible official bodies being involved, or at least informed.”Footnote 40 Sering answered by sternly reminding them that their boss (Darré) was fully aware of the conference, attached a list of letters and attendees, and ended the letter with “Heil Hitler.”Footnote 41 After some more back and forth, Sering was informed that Konrad Meyer would represent the German government.

Sering was then contacted by Elmhirst in early May, with the American professor passing along the news that one of the members, a “Hebrew,” was withdrawing from the conference, and asked whether there was any guarantee that the Russian delegation would be able to attend.Footnote 42 Sering contacted Frick and received a guarantee in writing that no “obstacles” would be encountered by the Russian delegation to the conference. Sering then passed this information to Elmhirst.Footnote 43

Finally, in late August and early September, the International Conference of Agrarian Economists took place and representing the German government, in Darré’s place, was the man who perhaps more formally would supersede Sering, Konrad Meyer. Elmhirst opened the proceedings, thanking Sering for his and others’ organizing of the event and the German government for sending Meyer. Sering next provided a basic greeting, and was followed by Meyer, who mounted the podium to deliver a speech full of Race, Space, Lebensraum and Volk. In line with the Nazi approach to science, Meyer reminded these assembled scientists that yes, we can exchange ideas, but politics was of the uppermost importance. He finished with a reference to the health of nations, noting that, while the foreign members of the audience had arrived to find a weak nation, he promised that it would quickly become stronger. Although this was followed by a relatively tame global overview of the world economy by Sering, the old professor ended by imploring that governmental control not “smother” the peasantry and warning that when governments move too quickly they tend to not allow much public discussion of what they are doing. Nevertheless, Sering reminded his audience, “we” are men of science, and let us not personally attack anyone or any party at this conference.Footnote 44

Darré would have been pleased with the next two speakers. The first attacked the expert (Sering), accusing him of committing the “murder of the pigs” during the war.Footnote 45 Then, reporting straight from Darré’s office, Dr. Ludwig Herrmann opened with this: “National Socialism is not a method, instead it is a Weltanschauung.”Footnote 46 He went on to mock the idea that, as Ukraine and Canada produced more than enough wheat for the world, we should let them alone grow it. Alas, this philosopher noted, people are not so nice, and instead “becoming (werden) and growing is only accomplished through fighting and striving and struggling in this world,” and that there was no such thing as a “global economy, only a Volk-economy (Volkswirtschaft).”Footnote 47 We Germans, Herrmann stated, required food security and market regulation, and only via Darré’s law could this be achieved.

One speaker who at least attempted to please both sides was G. Lorenzoni. He opened by praising the massive influence of Sering in Italy for the last many decades, especially via the 1919 Reich Settlement Law. Lorenzoni happily pointed out that Sering had in fact been his teacher some thirty-four years earlier. Interestingly, to this agrarian scientist, operating outside the German personal and political fights, he concluded by stating that the fascist approach to inner colonization in Italy was working very well.Footnote 48 Schacht then spoke of international credit problems, Henry C. Taylor discussed international agrarian planning, and Sering gave a brief closing address.Footnote 49

The Setting Aside of Sering

A few weeks after the conference, Darré wrote to Frick thanking him for the embargo on Sering’s memorandum and went on to point out how dangerous it was for Germany, especially considering the press coverage. Darré later forwarded this letter to Hitler in November and Chief of the Reich Chancellery Hans Lammers in December. Finally, in late December Darré reprimanded Frick and told him to stop protecting the professor and to please cut off all government funding to the Sering Institut.Footnote 50 This last letter is especially intriguing as it indicates that Darré was unaware that Konrad Meyer had in fact already achieved this. Not long after the conference, on October 12, Meyer called for the end of all funding for the Sering Institut by November 1. Sering had been given assurances that he still had time to finish up the institute’s affairs, for he wrote to the Minister of Science, Education and National Culture, Bernhard Rust on November 19 thanking him for a three-month extension in funding. Whatever promises had been made, Rust quickly got back into party line, writing four days later: “due to a scarcity of funds a monthly subsidy from 1 November 1934 can no longer be granted.”Footnote 51 An indignant Sering responded that they had been promised funding until April 1, that people were employed, there was work to be done, and that they could not accept a sudden suspension of funding. This letter ended with “Heil Hitler.” Another ministry letter, from December 22, stated that as of the twentieth, there was no more funding available and that “[t]herefore I see myself obliged to dissolve the institute with effect from 31 December 1934.”Footnote 52 On Christmas Eve, Sering was forced to write to the members of the institute that it would be pointless for him to reiterate the reasons the government was shutting them down, as these motives were already widely known. He reminded his colleagues that since the end of the war they had been the central place for the study of settlement, something they had shown the world at Bad Eilsen, and that they should therefore all be proud. This letter he ended with “mit deutschem Gruss,” (with German greetings) and not “Heil Hitler.”Footnote 53

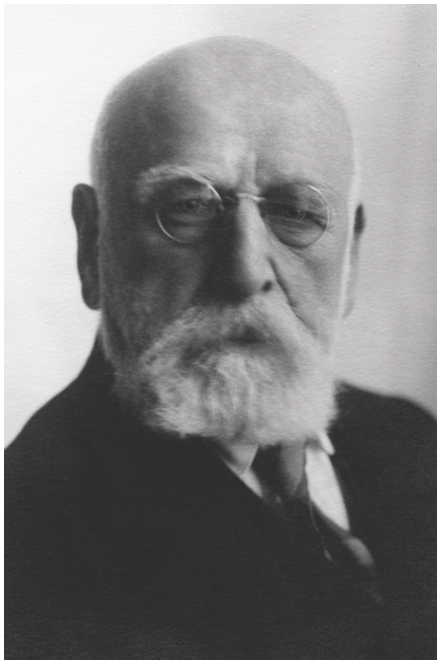

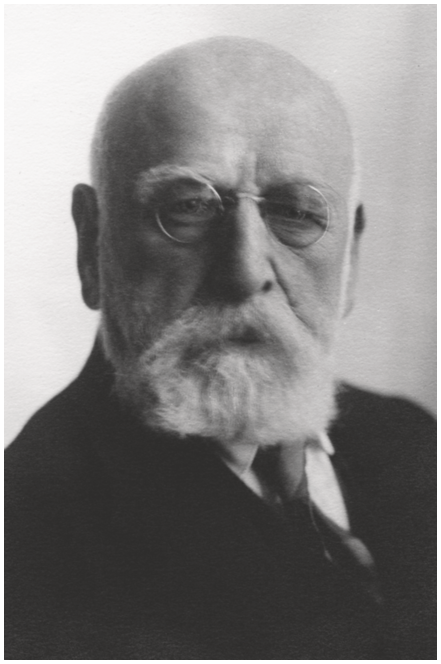

In her analysis of the shift in power from Sering to Meyer, Irene Stoehr astutely suggests that Meyer likely used Darré’s indignation to help him shut down Sering, though it seems without informing Darré of the fact. The institute had been on its deathbed since early November 1934 when, on December 20, Meyer confirmed that the Institute had to close once and for all, as the Minister had no “trust” (Vertrauen) in either the old professor or any of his trained students.Footnote 54 Darré’s letter demanding that Frick cut off funding, mentioned at the start of this section, was written on December 22. Darré may well have also been fooled by the fearless countenance of the seventy-seven-year-old professor. One of the only glimpses we have into the personal life of Max Sering at this time comes from the incredibly rich diary of the American Ambassador William Dodd. The University of Chicago history professor had actually spent time in 1900 studying at Leipzig and had likely already then been made aware of this friend of America. In fact, US Secretary for Agriculture, Henry A. Wallace, whom Sering had visited in Iowa in 1930, had told Dodd to allow Sering to use his diplomatic pouch for any correspondence to the United States. On the morning of October 24, 1934, Sering called on Dodd, to speak to him about a letter he was writing to Wallace. Dodd reported that the “very vigorous” Sering told him: “[t]hese people do not know anything about economic and historical problems. They are sacrificing the culture and intellectual life of Germany for their fantastic ideals of perfect unity and complete independence of all the world, which is impossible for a great nation.”Footnote 55 Dodd then relayed to Sering that, in March, he had strongly reminded Hitler and Rust about the importance of academic freedom for world civilization. Sering was “surprised and most happy” to hear this. The old German, who did not fear the Gestapo, went on, arguing that the present German leadership

has got itself into a warlike attitude toward all neighbors, and war would ruin Western civilization. This leadership demands submission from the universities, the churches and the people, to its childish ideal. It allows no freedom of speech, conscience or initiative. That will ruin us. We cannot endure it. I am no longer young. I oppose the system and I express my opinions when opportunity offers. If they want to kill me, they can do it. I shall not submit.Footnote 56

Dodd ended his diary entry with this: “Dr. Sering is in danger – serious danger – although I shall keep what he said entirely confidential.”Footnote 57 Dodd knew Schacht well, one of Sering’s staunchest defenders, and it is entirely possible that Schacht had brought home to Dodd the full danger of Sering’s situation.

Dodd met Sering again that momentous Fall, on Sunday, November 11. At lunch, Sering “was again most vigorous and outspoken in his opposition to the Hitler philosophy and practice.” And then, interestingly, “[h]is wife was even more venturesome in my presence.” Dodd wrote that the couple were attending Niemoeller’s church in Dahlem, and “rejoice at the Lutheran revolt against the present effort to force all Germans into one church – the Deutsche Christen.”Footnote 58 Sitting at that very table was a man wearing “the regular Party badge and to [Dodd’s] surprise, seemed to be preparing a report to the Propaganda Ministry of what he heard.” Sering ignored the man, although Dodd claimed the attentive Nazi was somewhat interested to hear that Sering was related to Admiral Tirpitz.Footnote 59

Although Darré had earlier attempted to bring the full force of antisemitism against Sering in the previously mentioned Der Stürmer article, Sering was forced to formally defend himself in the wake of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. After Sering filled out a University of Berlin form in September 1935, stating: “I do not belong to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party,” the University then sent him a letter in October asking whether any of his grandparents were “full Jews,” or “members of the Jewish religious community.” In his handwritten response, in December, Sering referenced the new laws to indicate that, with only one Jewish grandparent, he was just fine. Perhaps his response was not properly recorded, for in late February the following year, the Rector informed Sering that he could no longer be affiliated with the university, as he was “of a foreign race” (fremdrassig).Footnote 60 Sering responded again with his racial information, and in early March the Rector wrote that he was indeed sorry, there had been a mix-up in the office.

An important defender of Sering’s was “Hitler’s Banker,” the earlier mentioned President of the Reichsbank and Minister of Economics, Hjalmar Schacht.Footnote 61 Schacht put together a large edited volume in 1937 and had Sering contribute a chapter, the elderly professor’s first publication since the 1934 imbroglio. Although much of the article, “The Agrarian Foundation of the Social Constitution. Great Britain – Germany – Southern Slavic Countries,” focuses on the United Kingdom, Sering’s growing interest in the Danubian Basin (Donauraum) of the Southeast was on full display. Once again, Sering stubbornly mentioned the importance of traditional laws of inheritance for family and farmer stability, something that would surely be seen as once again criticizing the Darré system.Footnote 62 Indeed, more evidence indicates that Sering was as foolhardy as ever. As this volume was coming out, Sering and Schacht made an interesting appearance in Dodd’s diary. On March 30, 1937, Dodd arrived late to what he referred to as Sering’s eighty-fifth birthday (Sering was eighty and, while his birthday was in January, the party that year was in March). Although he missed Sering’s and Schacht’s speeches, he heard that, in front of a hundred guests, both had “criticized the Nazi policy and German military activity. I [Dodd] knew both of them thought this way but was surprised to hear they had felt free enough to talk before a large group of people. Schacht said to me [Dodd]: ‘My position is very critical; I do not know what is to happen’.”Footnote 63

The Triumph of Race Science and the Evolution of the German Right

With Darré’s “breeding” policies ultimately replacing the ethnic nationalism of Sering’s agrarian-centred small-plot farming families, we see the emergence of eugenics onto centre stage in Germany. From the 1890s to the late 1920s, eugenicists were often in Sering’s orbit, whether sitting beside him at meetings of the Navy League or whispering in the ears of his close friends, such as in Schwerin’s Pan-German circles or amongst the utopian rural thinkers around Sohnrey. In eugenics’ earliest form, the Social Darwinists were interested in rural reform and may well have eventually crossed paths with Sering and garnered his attention, but by the time of the founding of the Racial Hygiene Society in 1905, Alfred Ploetz and other leaders of the movement had largely abandoned any agrarian or romantic interests and were purely focused on “scientific” breeding. But these thinkers were difficult to place on the political spectrum. Because of their desire to prevent the procreation of those deemed “weak” or “inferior,” it is often mistakenly assumed that eugenicists were fully on the right politically. Yet their belief that certain traditional values should be ignored in the pursuit of maximally healthy human bodies often led them to hold seemingly liberal values, such as equal rights for women, an interest in socialism, and very little patience for antisemitism. In the 1920s, however, thinkers like Darré managed to take the baseline eugenic program of breeding and link it to exclusive race thinking, that is, Aryanism. Further, Darré connected racial hygiene to his version of inner colonization, where race breeding was to take precedence over the “agrarian” functioning of the system. This was the new agrarian program against which Sering fought in 1934. As “proper” inner colonial thinkers like Sering were “removed” by Darré and his ilk, so the old, “pure” eugenicists were equally silenced by the Reichsbauernführer. To the previous generation who had fought hard to remove “tradition” and “unscientific” thinking from racial hygiene, the Nordic Ring and associated Aryan occult elements all sounded rather silly.Footnote 64

Paul Weindling argues that it was the First World War that marked the shift in eugenics from intellectual theory to state planning, spurred by concern over a falling birthrate, nutrition challenges, the loss of so many young men, etc.Footnote 65 Sering’s inner colonization had been offered as the solution to such problems before the war but, over the course of the 1920s, the more radical solutions of eugenics gained increasing purchase. Simultaneously, the experience of the war marked a crucial shift in the possibilities of German colonial thinking. The prewar Pan-Germans and their ilk had been interested in the expansion of the German sphere of influence deeper into eastern and southeastern Europe. But such “colonial” endeavours were always to be undertaken alongside the classic pursuit of a proper nineteenth-century Great Power, that is, the maintenance of overseas colonies and global trade, all protected by a modern navy. With the loss of the German overseas empire during the war, there would be no more “split” in German colonial attention or ambition. Although the Eastern Empire had also been lost, most imperial-leaning German thinkers from 1919 on agreed that the only future for German expansion would be by land. While Sering remained detached from the rise of biological racism on the German Right, he was of course very sympathetic to the increasingly land-focused thinking of his conservative colleagues. In fact, in the final phase of his life, Sering would become a major advocate of a Mitteleuropa-style of thinking, along the lines of Naumann’s publication of that name in 1915.

Sering, Inner Colonizer of the East, Becomes an Ostforscher

By 1935, Sering fully realized that he had lost his hallowed perch atop the world of “inner colonization.” Darré and Meyer had taken over his role as the new intellectuals of settling Germans on “empty space,” within the Raum and the borders of the Reich. Sering hated their approach to settlement, but of course in certain key ways it could be seen as simply the most radical version of what he had always wanted.Footnote 66 The fact that his protégé, the man who took over his chair at Berlin, Dietze, seemingly endorsed the new Nazi path and yet remained a very close colleague of Sering, indicates that pride was likely at the center of the obstinate Sering’s dismissal of the Erbhofrecht. He could have chosen at this moment to walk quietly into oblivion, or indeed to turn against all Nazi colonial thinking. But he most certainly did not. Instead, just as the radical laboratory that was the Great War had led to him moving further “eastward” in his thinking, beyond Germany itself and all its many frustrations and obstacles, Sering spent the twilight of his career doing, mentally, the very same thing. Sering became an Ostforscher, a researcher of the “East.”

Michael Burleigh’s seminal 1988 book, Germany Turns Eastward, details the transition from Osteuropaforschung, the study of Eastern Europe, to Ostforschung, the study of “the East,” a change in thinking that is helpful in understanding this late and final evolution of Sering. Alongside colleagues like the renowned Russia expert Otto Hoetzsch, Sering had for decades studied the people and land of East Central Europe, and importantly did not see Russia as the Urfeind, eternal enemy, of Germany. Poles were much more of a problem for Sering than Russians. Burleigh tracks a shift in the late 1920s, and increasingly throughout the 1930s, of academic specialists of the East, like Sering, from their “moderate” study of Eastern Europe to a focus on the entire Eastern European space as one to be dominated by Germany. Such a move inevitably became anti-Russian at its core. And such was of course an academic development fully in line with Nazi spatial thinking and ideology. As we shall see, whereas Hoetzsch would not bend the knee and was largely removed from the academic scene by 1935, in that same year, Sering, in the wake of his troubles with Darré, decided to cozy up to the now dominant Ostforscher, specialists of “the East.”Footnote 67

Ultimately, this was not exactly a major leap for the old inner colonizer. One of the major areas of Ostforschung was the study of Deutsche Sprachinseln, islands of German speakers found throughout Eastern Europe, and, following from this, how these Germans could be used for geopolitical gain. Indeed, David Thomas Murphy, in his The Heroic Earth: Geopolitical Thought in Weimar Germany, 1918–1933, makes the argument that the intellectual foundation provided by the “inner colonizers” was key to the rise of this academic discipline.Footnote 68 He states that those historians who attempt to draw a hard divide between the earlier thinkers and those who thrived under National Socialism, due to the injection of specific race theories, are simply wrong. Willi Oberkrome pushes this argument, claiming that, instead of a 1933 caesura when it comes to German thinking about the East, one must instead recognize the continuum, as he argues in “Consensus and Opposition: Max Sering, Constantin von Dietze and the ‘Right Camp’ 1920–1940.”Footnote 69 Here Oberkrome traces the many ways in which the work of these two professors on agrarian settlement were not so very different from what became Nazi agrarian settlement science. Once Sering announced that he would like to be a part of team Ostforscher, he had little trouble, for, after all, in Oberkrome’s words, he was “one of the most imposing figures in the German academic landscape of the early twentieth century.”Footnote 70

A mere two months after Darré and Meyer’s “silencing” of Sering, the old professor sent a letter to the German Academy in what would today be termed a “cold call.” After informing the leadership there of how important his International Agrarian Conference had been, and that both Schacht and important members of the NSDAP had attended in Bad Eilsen, he stated that the Academy had indicated its desire to focus on German settlement in eastern and southeastern Europe. As a specialist on the agrarian history of Germans, he informed them that, since the Middle Ages, German peasants’ ability to sell their own land had been crucial to their development (somewhat ironic from a man who had spent decades complaining about speculation). Thus, immediately after citing his Nazi bona fides (Meyer’s attendance at the conference), Sering could not help himself but directly criticize Darré’s Erbhofrecht. He ended his letter with a request, suggesting to the Academy that he write “the agricultural constitution of German settlements in non-Russian eastern and southeastern Europe.”Footnote 71 As was the case for the remainder of his life, Sering ended the letter with his “German greeting,” and not “Heil Hitler.” It appears the latter was only used when he still believed he could convince high level Nazis of his point of view or was attempting appease Nazi addressees. A couple of weeks later Sering wrote directly to the godfather of geopolitical-thinking, Karl Haushofer, thanking him for the writings he had sent Sering. He complimented Haushofer, telling him that, for many years, he had been an “eager reader” of his Zeitschrift für Geopolitik. He hoped that Haushofer had seen his recent request to the Academy and informed him that he would be attending the upcoming conference in Munich.Footnote 72 Haushofer responded that he was so excited by Sering’s ideas that he would like him to present at the conference.Footnote 73

Sering attended the Munich conference and claimed to have learned a lot from the growing Ostforscher crowd.Footnote 74 By May 1935, Sering was in correspondence with many of them, including Albert Brackmann, Director of the Prussian State Archives in Dahlem. In turn, the Ostforscher were keen to tell Sering to be very discrete, as the politics were rather delicate, especially with Poland and Czechoslovakia.Footnote 75 In late May, Sering wrote to Dietze informing him that Brackmann had told him that he, Brackmann, led a research foundation that had as its focus the European East and the Germans living in that space. Further, Sering would be giving a talk for them at the Prussian Archive in Dahlem the following Tuesday.Footnote 76 Sering then went one step further and used his lifelong accumulated stature as a fair-minded international scholar: he wrote to his co-conspirators that they could use the International Agrarian Conference membership and structure as an umbrella to make the whole project look innocuous and scientific, but to watch out as there were members from Eastern Europe and the Baltic states that had to be kept in the dark.Footnote 77 This approach reached its culmination in Sering’s speech at the International Agrarian Conference held in St. Andrews, Scotland, in late Summer 1936. After walking his listeners through Germany’s agrarian history, and how the Diktat had both wreaked havoc on the agricultural sector and barred Germany from global trade, he turned to his new idée fixe; southeastern Europe, if joined in an economic union with Germany, would encompass some 225 million souls and be the size of the United States, always Sering’s standard for a proper land empire. Further, and invoking one of Sering’s favourite colonial measurements, the density of the population living along the Danube was only 57 PPSKM. Finally, while this area would only benefit from free and open trade with Germany, it happened to be in possession of most of the raw materials that the German economy required.Footnote 78 This appears to have been Sering’s final moment on the international stage.

By June 1935 Sering was actively bringing together authors for the chapters of his planned edited volume on Eastern Europe, the book that would be his final major project. The people he brought on board, such as Kurt Lück and Walter Kuhn, would later become intimately involved in Meyer’s Generalplan Ost, the genocidal organization of occupied Eastern Europe during the Second World War.Footnote 79 By October, Sering was far enough along on the project to ask his new “source of support,” the Academy, for ninety-five marks for an eight-day research trip to Poland. They gave it to him.Footnote 80 Sering surely felt (as would decades of historians after 1945), that his new friends, the Ostforscher, were somehow not part and parcel of the Nazi project for the East. On December 6, 1935, Dodd once again encountered Sering and his wife, and Sering’s daughter’s mother-in-law, Countess von Tirpitz. The “frank” talk at the table shocked Dodd, as all present openly criticized the current regime. Nevertheless, Dodd was taken aback when his private conversation with Sering took a very different turn: “Germany’s economic interests must spread over the Balkan zone, where there must be an exchange of industrial for agricultural goods,” stated Sering, who later added, “[o]f course political co-operation must follow.” Dodd, who had clearly met many similar “non-Nazis,” wrote the following in his diary:

This was not discussed because I did not care to remind him that the old Kaiser’s policy of expanding toward Constantinople was the chief cause of the World War. It is an instinctive policy of national-minded and even moderate Germans to annex parts of the Balkan states and dominate the others, just as Mussolini thinks the Mediterranean Sea and the countries bordering it are properly his, perhaps excepting France.Footnote 81

Here, Dodd is succinctly summarizing Burleigh’s thesis many decades in advance. Yet, as Dodd would note a month later, Sering was never a Nazi, and was instead “an old-time royalist who prays for Hohenzollern restoration.”Footnote 82 Indeed, while warming up to the Nazi-adjacent Ostforscher, Sering made clear his contempt for those who held undisputed power in the Third Reich. At an event on February 20, 1937, with black-uniformed SS in the room, Sering openly and loudly criticized the regime’s treatment of universities. After Dodd signalled to him the enemy in the room, Sering shouted “I say what I think. They can shoot me any time they want to. This system is ruining German intellectual life.”Footnote 83

Of course, Sering’s research was an obvious and direct continuation of the very Naumannesque Mitteleuropa-thinking praised by Sering and others some twenty years earlier during the Great War. To what degree then was Sering now flirting with the newer, darker, racial elements of Ostforschung? A folder in Sering’s papers, containing some research notes for his edited volume then underway, reveal that he was, at the very least, reading the racially leaning material of his peers. Works like Herbert Meyer’s “Folk, Race and Law” are heavily underlined, and there are typed notes to Karl Schöpke’s “Outline for an Overall Plan for Policies to Overcome the Flight from Agriculture.” Although the latter was deeply race-based, Sering surely enjoyed the author’s claim that Sering’s Reich Settlement Law had been successful. Strangely, Schöpke first praised Darré’s 1934 law before pointing out that a lot of farmers had left the land from 1933 to 1938. Sering’s handwritten note at the end of this last sentence screams “NB! Without any connection to the previous point then.”Footnote 84

Sering’s activity regarding the volume was intense. In October 1937, he toured the Balkans, visiting professors, and in March 1938 he spent a week in Timisoara, Romania. In May 1938, he exchanged letters with Gustav Fochler-Hauke, a Sudeten German who worked closely with Karl Haushofer. At the time, Sering was editing the volume’s chapter by Andreas Meisner on the Sudetenland, and fascinatingly, at this moment when the circumstances for the Germans living there had quite suddenly changed, Sering did not want the chapter to be “updated.”Footnote 85 In another letter to Fochler-Hauke in April 1939, as the edited volume was about to appear, Sering proclaimed that both Lebensraum and Sprachinseln (ethnic enclaves or “language islands”) were themes in the new work and he very much hoped it would find a wide audience. Sering then admitted that, as Fochler-Hauke likely already knew, Darré hated him for something he had written long ago, something that “developments had unfortunately proven [Sering] to be completely correct about.” Regarding the sour relationship, Sering “fear[ed] that because of this,” any review in a journal associated with Darré was bound to be biased against him.Footnote 86

When the volume finally did appear, Sering and Dietze’s long forward opened with the happy news of the return of the Sudeten Germans to the Empire.Footnote 87 Despite Sering’s readings over the last two years, the tone is not explicitly racist. It instead harkens back to the decades-old language of German high culture, law, and justice, and how these things should spread into the eastern and southeastern spaces that were, and had always been, German. They argued that the “principle of nationality” meant, quite simply, that once land was Germanized, that land should become a part of the nation of Germany, an argument that was in effect a green light to conquer most of eastern and southeastern Europe, for at least “some” Germans could be found almost anywhere. Along these lines, their discussion of the Wartheland is especially illuminating. After stating that Posen and West Prussia had been settled by Poles and Germans, and that Frederick the Great had disparagingly referred to this space as “backwoods Canada” (hinter Kanada), they argued that the 1886 Program of Inner Colonization had only been partially successful, as “the ruling government principles avoided any compulsion and an energetic Polish counter-colonization was allowed.”Footnote 88 At the very end of his life, Sering was here regurgitating elements of the Nazi critique of his life-long work, that legal niceties were weak, and that “lesser races” were not to be negotiated with. The authors then spent some time, in line with the “principle of nationality,” arguing for the German nature of this land, especially the so-called Polish Corridor, and thereby providing “scientific” cover for Hitler’s “proper” return of said space to the Reich (something about to take place that fall). With regard to the land of the Corridor, they wrote: “The efforts made during the Bismarck Empire, when it was considered inadmissible to use force, resulted in merely consolidating the existing German population, and thereby the German majority.”Footnote 89 Indeed, the authors claimed that had Posen and West Prussia been given a vote in 1919, they would have chosen to stay in the German Empire, as many of the Poles had assimilated and the Prussian state had instilled duty and honour among them. Thankfully, rejoiced the authors, Hitler had ripped up the very Diktat that had stolen the land. They finished their foreword claiming that a new “Greater Economic Space” (Grosswirtschaftsraum) in East Central Europe would be good for Germany, and the Sprachinseln would be much safer under such circumstances.Footnote 90

The Twilight Years

Supporting Women

In an article celebrating the old professor’s eightieth birthday in January 1937, one of Sering’s many female students, Wendelin Hecht, wrote that, after the war, Sering had ended every lecture with a call for the end of the Diktat, the restoration of the honourable military, and the independence of Germany. She claimed that the lecture halls were packed with soldiers and officers who loved him, and that he would take students on hour-long hikes through the Grunewald, observing woodpeckers hunting for worms.Footnote 91 Among the ninety-six guests at the formal birthday party held that March were old academic pals, Auhagen, Broedrich, Meinecke, Oncken, Ponfick, Adolph Weber, inner colonizers Gayl and Lindequist, the lead Ostforcher Brackmann, Sering’s closest protegé Dietze, Sering’s daughter and her husband von Tirpitz, Schacht, Ambassador Dodd, and the Minister of Finance Graf Schwerin von Krosingk.Footnote 92 In a speech at the party, Schacht declared Sering to be the “best fighter for Germany’s Lebensraum.”Footnote 93 For his part, Sering expressed that he did not hear that evening’s speeches to be so much about him, as they were about the importance of “free speech in the sciences as necessary for Germany’s well-being.”Footnote 94 In other words, the old professor seemed to never let a public moment slip past without a dig at the anti-intellectualism of the Nazis.

It was no coincidence that a woman wrote the article detailing the professor’s relationship with his students. German politician and seminal member of the German women’s rights movement, Marie-Elisabeth Lüders, published an article in Die Frau in February, fondly recalling her classes with Professor Sering, how the door to the lecture hall would swing open ninety degrees, and in Sering would confidently stride. He would put down his books with a thump, then lecture passionately in a loud full voice, all the while with his water glass at the edge of the lectern, about to fall.Footnote 95 Although conservative, Sering took on many female students and possessed at least a moderately feminist understanding of women’s roles in the public sphere. In 1905, he hosted women’s rights activists at his home, and as early as 1902 he convinced the later famous social reformer, Alice Salomon, to pursue studies which he later oversaw. Salomon proclaimed Sering to be “very progressive.”Footnote 96 Lüders had in fact been his doctoral student (co-supervised with Schmoller) in 1912. Indeed, Sering’s own daughter was studying economics under her father when she met Wolfgang, the son of Admiral von Tirpitz, in class, whom she then married in 1921. Female academics knew Sering to have a sympathetic ear, and many of them wrote letters to him when he took his stand against the Erbhofrecht in 1934, for, in its already absurd “youngest son” inheritance procedure, women (including the widow) could be banned from inheriting the farm even if they were the only living child.Footnote 97 Sering’s interest in female academics reached its zenith at the very end of his career when, in 1939, he and Dietze edited volume number three of the series “German Agrarian Politics,” entitled Women in German Agriculture. In the foreword the authors generously stated that the new Erbhofrecht had stopped the agrarian crisis but had not done enough to halt the flight from the land. This flight, they argued, alongside massive industrialization, had put the German Hausfrau in an incredibly difficult situation.Footnote 98 There followed six chapters on the plight of women in the German countryside, and all were written by women.Footnote 99

Negotiating with Power

Sering was forced to use what power he had left in the Summer of 1937 when his protegé, Dietze, was arrested. Dietze had been a Russian prisoner of war in Siberia and had there learned Russian. After the war he had written a dissertation at the University of Breslau in 1919 on Stolypin’s land reforms and completed his Habilitation with Sering in 1922.Footnote 100 The two had in fact met in Warsaw in March 1918, after Dietze’s liberation following the Russian Revolution. Dietze was Sering’s replacement at the University of Berlin in 1933, but things were not easy for him under the Nazi regime. At Bad Eilsen in 1934, Dietze had put on a good face, praising the attempt at full control over the agrarian sector being put in place by Darré, but, behind the scenes, there was little Sering’s protegé could do to escape the wrath of the Reichminister.Footnote 101 He did not help himself by being a member, like Sering, of the Confessing Church, and he was indeed quite active in his local church in Potsdam. By 1936, he had escaped to the more hospitable Freiburg, replacing the retiring Professor Karl Diehl at the university there, but he was back visiting in Potsdam in the Summer of 1937 when he crossed the line, as it were. It appears that the local Confessing Church pastor had been removed and replaced by a member of the Nazi-friendly “German Christians.” That new pastor, Dr. Thom, did not like what Dietze was saying in the church one Sunday and asked him to stop. Dietze then asked the congregation to follow him outside, where he continued to speak of the injustice of the current situation. Shortly thereafter the Gestapo arrested him. Sering fired off letters to Schacht and the Minister of Finance, Krosingk. Dietze was released after two weeks and skulked off to Freiburg where he kept his head relatively low but continued to work closely with Sering over the next two years.Footnote 102

In the same year as Dietze’s arrest, Darré resumed his vitriolic attack on Sering with the publication of a book entitled The Murder of the Pigs (Der Schweinemord). Darré’s thesis was that a cabal of Jewish professors, intent on the destruction of Germany from within, conspired to starve the nation into defeat during the Great War. At the centre of the story was the “half Jew” (in reality, one-quarter Jewish) Sering, at the head of the scientific commission charged with organizing the feeding of the German people. The first thing Sering and his henchmen did, seethed Darré, was to call for the slaughter of seventy-five percent of Germany’s pigs in early 1915. Of course, a Jewish disgust for pork was cited as a motivating factor. And to remind us as to why Darré was so angry with Sering, he wrote that Sering’s call for the pig slaughter was done via a secret memorandum (the very same way he attempted to disrupt Darré’s Erbhofrecht in 1934). Some twelve pages later, Darré indeed reminded his readers of the 1934 backstabbing episode.Footnote 103

While it is more than clear that Darré had an undying hatred for old Sering, Konrad Meyer’s relationship with him is more difficult to discern. Irene Stoehr argues that the cold, calculating Meyer instrumentalized Darré’s anger against Sering for his own purposes, slowly but surely usurping Sering’s role as the chief settlement expert of Germany. She goes further, invoking a vaguely Oedipal take down and replacing of the authoritative father, but a passage in Meyer’s autobiography runs somewhat against such an interpretation. Meyer’s father was a conservative patriot embittered by the First World War, similar to Sering, and the father and son were quite close before the former’s death in 1931.Footnote 104 In any case, Meyer was directly involved in sidelining Sering in 1934, but the historical record leaves us with the words of someone who at least “performed” respect and deference toward his elder. In the preparation for the next International Agrarian Conference, to be held in Banff in 1938, Meyer corresponded very cordially with Sering, as Meyer would be representing Germany in Canada. Sering was heavily involved in organizing which other professors would be going and was full of advice for Meyer. Stoehr frames this as the final usurpation of Sering by Meyer, but I highly doubt Sering was ever going to make such a journey at his advanced age.Footnote 105 The following year Meyer would take over the editorial role for NB, and at that point a noticeable shift to more theoretical work on settlement appeared in the journal.Footnote 106 Such thinking would soon take centre stage with the conquest of Poland and renewed work of settlement in the Wartheland.

Sering’s End

Indeed, the newly erupted war in the Fall of 1939 led to Sering’s final act. Finding his nation once again involved in a major conflagration, Sering set aside his reservations with the Nazi regime and relied upon his experience during the First World War studying Germany’s wartime economy to come up with a ten-page report in October, providing some general advice on how Germany should more effectively withstand the pressures of a breakdown in global trade. It surely irked him that he had never been allowed to publish the findings of his First World War research team, though at least he knew their work was probably being studied, as the Nazis had confiscated his entire archive of documents for the Economic Commission in 1933. In any case, he now set about putting his thoughts to paper, beginning by reminding the audience of his expertise, highlighting that “during the world war” he had been “Chairman of the ‘Scientific Commission of the Prussian War Ministry’.”Footnote 107 His three major points were profoundly linked to the experience of that war: (1) Germany could not win a stalemate war with France under the current conditions, so a British Blockade would have to be overcome (sprengen); (2) To survive a long war Germany would have to be on the defensive behind a “Westwall,” while getting rural workers back on the land, and developing the Silesian coal export to neutral Eurasian countries; and, finally (3) Pursue a strong diplomacy with neutral countries in order to keep Germany as powerful as Russia. He proceeded from these points to offer several interesting thoughts, including a fear that the Americans would set up factories in Canada in order to be able to make and sell weapons to the Allies. He opined that it would be great if the Germans could pierce the Maginot Line and win a war of movement, as they had in Poland, but that this was highly unlikely, and unfortunately Germany could never win a long war of attrition against the Allies. This was especially true as another 950,000 Germans had fled the rural districts since 1933. Shockingly, Sering chose this moment to once again blame Darré’s inheritance law for this flight from the land. Nevertheless, hunkering down behind a western wall would protect German rural workers, and then a “diplomacy” that brought in East Central Europe, Southeastern Europe, Italy and Italian Africa would create a bloc of 225 million people, Sering claimed, enough to weather any blockade, especially if good trade relations with Russia were maintained. He ended the memorandum with praise for Hitler’s ripping up of the Diktat, and the hope that Germany, in such an alliance with Eastern Europeans and Russia, could defeat the “pirate law” of the British, the true enemy. If we required any more evidence of just how out of step Sering’s understanding of the new dynamics in Germany were, how naïve he was about Germany’s future in the East, this final document makes it quite plain that, at the end, Sering was still the relatively moderate nineteenth-century imperialist he had always been.Footnote 108

These thoughts, on how his homeland could best weather the storm of yet another global conflict, were still on Sering’s mind when, at 10 pm on the evening of Sunday, November 12, he died. After working hard throughout October, stomach trouble sent him to bed in early November. During that final Sunday, intestinal and stomach bleeding hastened the end. As late as 9 pm he was reading aloud from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, indicating which sections should be highlighted.Footnote 109 He then fell asleep. But, at the last moment, he awoke with a start and said to his daughter his last sentence. It was a summation of what he had learned in a lifetime of studying economics and imperialism, and simultaneously a critique of the National Socialists: “Autarky, crazy!” (“Autarkie, wahnsinn!”)Footnote 110

At 11:30 am, on Thursday, November 16, 1939, Sering was buried beside his son in the small cemetery behind the St. Anne Church in Dahlem, Berlin.Footnote 111