1.1 Definition and extent

The cryosphere is the term which collectively describes the portions of the Earth’s surface where water is in its frozen state – snow cover, glaciers, ice sheets and shelves, freshwater ice, sea ice, icebergs, permafrost, and ground ice. The word kryos is Greek meaning icy cold. Reference DobrowolskiDobrowolski (1923, p. 2, Reference Barry, Jania and BirkenmajerBarry et al., 2011) introduced the term cryosphere and this usage was elaborated by Reference ShumskiiShumskii (1964, pp. 445–55) and by Reference Reinwarth and StäbleinReinwarth and Stäblein (1972). Shumskii included atmospheric ice, but this has generally been excluded. The cryosphere is an integral part of the global climate system. It has important linkages and feedbacks with the atmosphere and hydrosphere that are generated through its effects on surface energy and on moisture fluxes, by releasing large amounts of fresh water when snow or ice melts (which affects thermohaline oceanic circulations), and by locking up fresh water when they freeze. In other words, the cryosphere affects atmospheric processes such as clouds and precipitation, and surface hydrology through changes in the amount of fresh water on lands and oceans. Reference Slaymaker and KellySlaymaker and Kelly (2006) published a study of the cryosphere in the context of global change, while Reference Bamber and PayneBamber and Payne (2004) detail the mass balance of glaciers, ice sheets, and sea ice. The discipline of glaciology encompasses the scientific study of snow, floating ice, and glaciers, while the study of permafrost (cryopedology) has largely developed independently.

In a report on the International Polar Year, March 2007–March 2009, the World Meteorological Organization (2009) identified the following important foci of cryospheric research: rapid climate change in the Arctic and in parts of the Antarctic; diminishing snow and ice worldwide (sea ice, glaciers, ice sheets, snow cover, permafrost); the contribution of the great ice sheets to sea-level rise and the role of subglacial environments in controlling ice-sheet dynamics; and methane release to the atmosphere from melting permafrost. These topics will be discussed, but in each case we first survey the basic characteristics and processes at work for each cryospheric element. We also consider the past cryosphere throughout geological time and model simulations of future cryospheric states and their significance. In the concluding Chapter 11, practical applications of snow and ice research are presented. We begin by considering the dimensions of the cryosphere.

Dimensions of the cryosphere

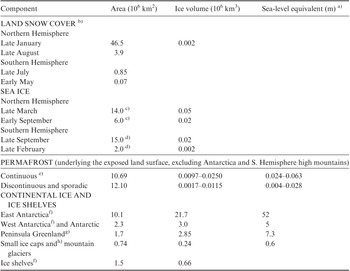

Table 1.1 shows the major characteristics of the components of the cryosphere.

Table 1.1 Areal and volumetric extent of major components of the cryosphere (updated after Goodison et al., 1999)

| Component | Area (106 km2) | Ice volume (106 km3) | Sea-level equivalent (m) a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAND SNOW COVER b) | |||

| Northern Hemisphere | |||

| Late January | 46.5 | 0.002 | |

| Late August | 3.9 | ||

| Southern Hemisphere | |||

| Late July | 0.85 | ||

| Early May | 0.07 | ||

| SEA ICE | |||

| Northern Hemisphere | |||

| Late March | 14.0 c) | 0.05 | |

| Early September | 6.0 c) | 0.02 | |

| Southern Hemisphere | |||

| Late September | 15.0 d) | 0.02 | |

| Late February | 2.0 d) | 0.002 | |

| PERMAFROST (underlying the exposed land surface, excluding Antarctica and S. Hemisphere high mountains) | |||

| Continuous e) | 10.69 | 0.0097–0.0250 | 0.024–0.063 |

| Discontinuous and sporadic | 12.10 | 0.0017–0.0115 | 0.004–0.028 |

| CONTINENTAL ICE AND ICE SHELVES | |||

| East Antarcticaf) | 10.1 | 21.7 | 52 |

| West Antarcticaf) and Antarctic | 2.3 | 3.0 | 5 |

| Peninsula Greenlandg) | 1.7 | 2.85 | 7.3 |

| Small ice caps andh) mountain glaciers | 0.74 | 0.24 | 0.6 |

| Ice shelvesf) | 1.5 | 0.66 | |

a) Sea-level equivalent does not equate directly with potential sea-level rise, as a correction is required for the volume of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets that are presently below sea level. 400,000 km3 of ice is equivalent to 1 m of global sea level.

b) Snow cover includes that on land ice, but excludes snow-covered sea ice (Reference Robinson, Frei and SerrezeRobinson et al., 1995).

c) Actual ice areas, excluding open water. Ice extent ranges between approximately 7.0 and 15.4 × 106 km2 for 1979–2004 (Reference Parkinson, Comiso and ZwallyParkinson et al., 1999a).

d) Actual ice area excluding open water (Reference Gloersen, Campbell, Cavalieri, Comiso, Parkinson and ZwallyGloersen et al., 1993). Ice extent ranges between approximately 3.8 and 18.8 × 106 km2. Southern Hemisphere sea ice is mostly seasonal and generally much thinner than Arctic sea ice.

e) Data calculated using the Digital Circum-Arctic Map of Permafrost and Ground-Ice Conditions (Reference Brown, Ferrians, Heginbottom and MelnikovBrown et al., 1997) and the GLOBE-1 km Elevation Data Set (Reference ZhangZhang et al., 1999).

f) Ice-sheet data include only grounded ice. Floating ice shelves, which do not affect sea level, are considered separately (Reference Drewry, Jordan and JankowskiDrewry et al., 1982; Reference HuybrechtsHuybrechts et al., 2000; Reference Lythe and VaughanLythe et al., 2001)

Figure 1.1 illustrates the global distribution of these components.

Figure 1.1 The global distribution of the components of the cryosphere (from Hugo Ahlenius, courtesy UNEP/GRID-Arendal, Norway) (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/ba/Cryosphere_Fuller_Projection.png)

The cryosphere has seasonally varying components and more permanent features. Snow cover has the second largest extent of any component of the cryosphere, with a mean annual area of approximately 26 million km2 (Table 1.1). Almost all of the Earth’s snow-covered land area is located in the Northern Hemisphere, and temporal variability is dominated by the seasonal cycle. The Northern Hemisphere mean snow cover extent ranges from ~46 million km2 in January to 3.8 million km2 in August. Sea-ice extent in the Southern Hemisphere varies seasonally by a factor of five, from a minimum of 3–4 million km2 in February to a maximum of 17–20 million km2 in September (Reference Gloersen, Campbell, Cavalieri, Comiso, Parkinson and ZwallyGloersen et al., 1993; Reference StroeveStroeve et al., 2012). The seasonal variation is much less in the Northern Hemisphere where the confined nature and high latitudes of the Arctic Ocean result in a much larger perennial ice cover, and the surrounding land limits the equator-ward extent of wintertime ice. Northern Hemisphere ice extent varies by only a factor of two, from a minimum of 7–9 million km2 in September to a maximum of 14–16 million km2 in March during 1979–2004. Subsequent years have seen much smaller areas in late summer (Reference Kay, Holland and JahnKay et al., 2011).

Ice sheets are the greatest potential source of fresh water, holding approximately 77% of the global total. Fresh water in ice bodies corresponds to 71 m of world sea-level equivalent, with Antarctica accounting for 90% of this and Greenland almost 10%. Other ice caps and glaciers account for about 0.5% (Table 1.1).

The World Atlas of Snow and Ice Resources (Reference KotlyakovKotlyakov, 1997) provides maps of climatic factors (air temperature, solid precipitation), snow water equivalent (SWE), runoff, glacier morphology, mass balance and glacier fluctuations, river freeze-up/breakup avalanche occurrence, and many other variables. The maps range from global, at a scale 1:60 million, to regional maps at 1:5 million to 1:10 million and local maps of individual glaciers at 1: 25,000 to 1:100,000.

Permafrost (perennially frozen ground) may occur where the mean annual air temperature (MAAT) is less than −1 °C and is generally continuous where MAAT is less than −7 °C. It is estimated that permafrost underlies about 22 million km2 of exposed Northern Hemisphere land areas (Table 1.1), with maximum areal extent between about 60° and 68° N. Its thickness exceeds 600 m along the Arctic coast of northeastern Siberia and Alaska, but permafrost thins and becomes horizontally discontinuous toward the margins. Only about 2 million km2 consists of actual ground ice (“ice-rich”). The remainder (dry permafrost) is simply soil or rock at subfreezing temperatures. A map of Northern Hemisphere permafrost and ground ice (1:10 million) was published by Reference BrownBrown et al. (2001) and is available electronically at http://nsidc.org/data/ggd318.html.

Seasonally frozen ground, not included in Table 1.1, covers a larger expanse of the globe than snow cover. Its depth and distribution varies as a function of air temperature, snow depth and vegetation cover, ground moisture, and aspect. Hence it can exhibit high temporal and spatial variability. The area of seasonally frozen ground in the Northern Hemisphere is approximately 55 million km2 or 58% of the land area in the hemisphere (Reference Zhang, Phillips, Springman and ArensonZhang et al., 2003b).

Ice (see Note 1.1) also forms on rivers and lakes in response to seasonal cooling. The freeze-up/breakup processes respond to large-scale and local weather factors, producing considerable interannual variability in the dates of appearance and disappearance of the ice. Long series of lake-ice observations can serve as a climatic indicator; and freeze-up and breakup trends may provide a convenient integrated and seasonally specific index of climatic perturbations. The total area of ice-covered lakes and rivers is not accurately known and hence this element has not been included in Table 1.1.

1.2 The role of the cryosphere in the climate system

The elements of the cryosphere play several critical roles in the climate system (Reference Barry and RadokBarry, 1987, Reference Barry2002b; Reference Barry and GanBarry and Gan, 2011). The primary one operates through the ice–albedo feedback mechanism. This concerns the expansion of snow and ice cover increasing the albedo, thereby increasing the reflected solar radiation and lowering the temperature, thus enabling the ice and snow cover to expand further. At the present day this effect is working in the opposite direction with the shrinkage of snow and ice cover lowering the albedo and increasing the absorption of solar radiation, thereby raising the temperature and further reducing the snow and ice cover. On a global scale, the ice–albedo effect amplifies climate sensitivity by about 25–40% (depending on cloudiness changes).

A second major influence is the insulation of the land surface by snow cover and of the ocean (as well as lakes and rivers) by floating ice. This insulation greatly modifies the temperature regime in the underlying land or water. The difference in the temperature of air overlying bare ground versus snow-covered ground is of the order of 10 °C based on winter measurements in the Great Plains of North America. The absence of snow cover could mean higher mean-annual surface air temperature, but severe wintertime cooling, and a substantial increase in permafrost areas over high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere such as Siberia (Reference VavrusVavrus, 2007).

A third effect is on the hydrological cycle due to the storage of water in snow cover, glaciers, ice caps, and ice sheets and associated delays in freshwater runoff. The time scales involved range from weeks to months in the case of snow cover, decades to centuries for glaciers and ice caps, and to 105–106 years in the case of ice sheets and permafrost. The more permanent features of the cryosphere accordingly have a great influence on eustatic changes in global sea level (see Table 1.1). A 1-mm rise in eustatic sea level requires the melting of 360 Gt of ice.

A fourth effect is related to the latent heat involved in phase changes of ice/water. This applies to all elements of the cryosphere. It is estimated, for example, that a 10-cm snow cover over England has a latent heat of fusion of 1015 kJ; melting the Greenland Ice Sheet would require ~1021 kJ. Reference OhmuraOhmura (1987) calculated that the melting of ice since the Last Glacial Maximum about 20 ka accounted for 26–39 × 103 MJ m−2, of similar magnitude to the total energy stored in the climate system (30–60 × 103 MJ m−2).

A fifth effect is caused by seasonally frozen ground and permafrost modulating water and energy fluxes, and the exchange of carbon (especially methane), between the land and the atmosphere.

1.3 The organization of snow and ice observations and research

The organization of cryospheric data began during the International Geophysical Year (IGY), 1957–1958, with the establishment of the World Data Center (WDC) system.

WDCs for Glaciology were designated in the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom. In 1976, World Data Center-A for Glaciology was transferred from the US Geological Survey in Tacoma, WA, to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Boulder, CO, where it has subsequently been operated by the University of Colorado (Reference BarryBarry, 2002a). The scope of its operations expanded to address data on all forms of snow and ice and in 1981 the National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service (NESDIS) of NOAA designated a National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). Its financial support was greatly augmented by contracts and grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) and the National Science Foundation. Roger G. Barry served as Director from 1976 until 2008 and was succeeded by Mark Serreze. Details on its data holdings and research activities may be found at http://nsidc.org. World Data Center-C for Glaciology addresses bibliographic data and is operated by the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge, UK, World Data Center-D for Glaciology was established at the Laboratory for Glaciology and Geocryology, Lanzhou, China in 1986. The letter designations were dropped in 1999 and in 2009 the International Council of Science (ICSU) decided to convert the WDC system into a World Data System. This is not yet operational but in the interim the WDCs continue to function as before. The International Science Council’s (ISC) General Assembly created the ISC-WDS (World Data System) in Tokyo, Japan in October 2008 (https://www.worlddatasystem.org/).

Over the last few years, major advances have occurred in the organization of snow and ice observations and research. Initially, the organization took place within the various cryospheric subfields (snow, avalanches, glaciers and ice sheets, freshwater ice, sea ice, and permafrost). Then, beginning in the 1990s, the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), and its partners the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and Global Terrestrial Observing System (GTOS), defined Essential Climate Variables (ECVs) (Barry, 1995; GCOS, 2004). For the cryosphere, these include snow cover, glaciers, permafrost, and sea ice. Global Terrestrial Networks (GTN) were specified for glaciers (GTN-G) and permafrost (GTN-P) (http://gosic.org/ios/GTOS_observing_system.asp).

At a higher level, the Integrated Global Observing System (IGOS) initiated the preparation of a report on a cryosphere theme (Reference Key, Drinkwater and UkitoKey et al., 2007) that documented the available and needed cryospheric data sets. In May 2007, the 15th Congress of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) received a proposal from Canada to create a Global Cryosphere Watch (GCW), analogous to the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW). In 2011, the 16th World Meteorological Congress (WMC) approved the GCW Implementation Strategy. In 2015, the 17th WMC implemented GCW in WMO Programmes (https://globalcryospherewatch.org/).

In July 2007, at the XXIVth General Assembly of the International Union of Geophysics and Geodetics (IUGG) in Perugia, Italy, the IUGG Council launched the International Association of Cryospheric Sciences (IACS) as the eighth IUGG Association. IAGS was developed from the International Commission of Snow and Ice of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS) via the transitional Union Commission for the Cryospheric Sciences (UCCS). This superseded the International Commission for Snow and Ice (ICSI) (Reference RadokRadok, 1997). IACS has the following five divisions: snow and avalanches, glaciers and ice-sheets, marine and freshwater ice, cryosphere, atmosphere and climate, and planetary and other ices of the solar system. www.iugg.org/associations/iacs.php

On the research side, the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) established a Climate and Cryosphere (CliC) Project in 2000 (Reference Allison, Barry and GoodisonAllison et al., 2001; Reference BarryBarry, 2003) that has four thematic areas: interactions between the atmosphere, snow, and land; interactions between land ice and sea level; interactions between sea ice, oceans, and the atmosphere; and cryosphere-ocean/cryosphere-atmosphere interactions on a global scale (http://clic.npolar.no). The CliC project is directed by a Science Steering Group and regularly organizes workshops and conferences.

In 2019, Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change published the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) that summarizes the characteristics and interconnection of ocean and cryosphere and their importance in the earth system, particularly in light of climate change impact.

1.4 Remote sensing of the cryosphere

Cryospheric science has benefitted enormously from the ready availability of satellite data since the mid-1960s. In recent years, there has been significant progress in the observation of the cryosphere by satellites, such as temporal and regional changes in ice sheets, trends and anomalies in Arctic sea ice cover, substantial decline of Arctic summer sea ice extent in 2012, pan-Arctic measurements of changes in ice thickness using satellite altimetry, and changes of its volume and mass. As a result, recent fluctuations in the cryosphere have been mapped with increasing certainty, demonstrating the potential for rapid loss in sea ice and snow cover, and the associated sea-level rise. Remote-sensing measurements of regional glacier volume change are also now available widely and modeling of glacier mass change has improved considerably. We will briefly summarize the main instruments that have operated and some of their applications. Further details are provided in the relevant chapters.

The hemispheric analysis of snow cover extent began in October 1966 from NOAA’s polar orbiting Very High Resolution Radiometer (VHRR) and continued with the use of the Advanced VHRR (AVHRR) and other visible-band satellite data. Global snow cover maps are now available from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on Terra (February 2000–present) and Aqua (July 2002–present). In December 1972, the NASA launched the Electrically Scanning Microwave Radiometer (ESMR) on Nimbus 5 enabling all-weather mapping of sea ice extent.

Passive microwave (PM) remote sensing has been in the core attention for obtaining representative retrieval of SWE data, which plays an important role in hydrological process. Despite of coarse resolutions and large uncertainties from systematic and random error in SWE data retrieved from spaceborne microwave sensors, such multifrequency satellite data are widely used in retrieving snow information of large coverage because the sensors are of wide swath, which produces many repeated observations and are insensitive to illumination and minimal influence of cloud cover. In October 1978, the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer (SMMR) launched on Nimbus 7 allowed sea ice concentrations and SWE to be delimited. SMMR operated until August 1987 and the records continued to the present with the Special Sensor Microwave Imager (SSM/I) on Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) satellites. The Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer – Earth (AMSR-E) observing system on board the Aqua satellite of NASA launched in 2002 provides a higher spatial resolution than SMMR and SSM/I (http://weather.msfc.nasa.gov/AMSR/). The frequency of the SMMR sensor is 6.6–37 GHz, the SSM/I sensor is 19–85.5 GHz, and the AMSR-E sensor is 6.9–89 GHz. Most retrieval algorithms for SWE exploit the negative spectral gradient between ~37 GHz frequency sensitive to snow grain volume scattering and a ~19 GHz frequency largely insensitive to snow (Reference TakalaTakala et al., 2011). The larger the difference between brightness temperature (TB) measurements at these two frequencies, the higher the SWE estimated.

AMSR-E has mapped SWE data sets over northern and southern hemisphere producing AE_5DSno SWE products since 2002. However, due to spatial variability of climate and terrain properties, the application of AE_5DSno SWE products (and similar PM data) and that of SMMR and SSM/I in mountainous areas has been argued. These products have 25 × 25 km fixed-grid cell resolution, which is very coarse for rugged surface topography of mountainous areas. However, there are classic downscaling methods based on uniform and nonuniform redistributions of SWE within a coarse pixel, and elevation and aspect direction maps developed to generate SWE products in 500 m spatial resolution, utilizing daily Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) snow cover images with cloud covers removed by, say, a time neighborhood method.

The Landsat series began in 1972 and in April 1999 Landsat 7 was launched. The Multispectral Scanner (MSS) at 80 m resolution operated through the mid-1990s, but with Landsat 4 (1982) and Landsat 5 (1984) the Thematic Mapper (TM) with 30 m resolution came into use. With the Landsat 7 launched in April 1999, the Enhanced TM (ETM) could provide data at 15–30 m resolution. The latest Landsat 8 satellite launched in February of 2013 carries two sensors, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) and Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) which acquire images in nine spectral bands with a spatial resolution of 30 meters. Landsat data have been widely used for mapping mountain glaciers. Together with 15 m resolution data from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) instrument (http://asterweb.jpl.nasa.gov/asterhome/), aboard the Terra satellite, outlines for over 83,000 glaciers have been compiled into the database of the Global Land Ice Measurement from Space (GLIMS) project at the NSIDC.

Extensive synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data have been obtained since the 1990s. The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Earth Remote Sensing (ERS)-1 active microwave instrument operated between 1992 and 1996 and ERS-2 has been operating since 1996. The available time series has been used to determine ice-sheet mass balances. The Canadian RADARSAT-I sensor has been providing SAR coverage of Arctic sea ice since 1995. In 1997, RADARSAT was rotated so that the first high-resolution mapping of the entire Antarctic continent could be performed. The RADARSAT-II mission launched in late 2007, which carries a C-band SAR offering multiple modes of operation including quad polarization, ensures the continuity and improvement of SAR coverage of Arctic sea ice. The NASA scatterometer on QuikSCAT has operated since 1999 providing another view of sea ice extent.

ERS radar altimetry has been used to estimate ice thickness in both polar regions. In 1997 interferometry with SAR was used to obtain ice velocity vectors over the East Antarctic ice streams. NASA’s Geoscience Laser Altimeter System (GLAS) on the Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) was used to measure ice-sheet elevations and changes in elevation, as well as sea ice freeboard from February 2003 through November 2009. ICESat-2, part of NASA’s Earth Observing System launched in September 2018, measures ice-sheet elevation and sea ice thickness, land topography, vegetation characteristics, and clouds. In April 2010 ESA’s Earth Explorer CryoSat mission, which carries a SAR Interferometric Radar Altimeter (SIRAL), was launched. It is dedicated to precise monitoring of changes in the thickness of sea ice in the polar oceans and variations in the thickness of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) was a joint mission of NASA and the German Aerospace Center. Since March 2002 to October 2017, by sensing gravity, the attraction between two objects from space, the twin satellites of GRACE have been mapping Earth’s gravitational field anomalies determined by mass every 30 days (Reference Tapley, Bettadpur, Ries, Thompson and WatkinsTapley et al., 2004), which is very useful for the scientific understanding of ice-sheet dynamics, land-ice response, and sea-level change to climate warming (Velicogna and Wahr, 2006). The movements of water and ice would cause a change in the Earth’s mass, which causes the distance between the twin satellites to change. By tracking changes in the distance between both satellites, we can calculate how gravity on Earth is changing regionally, from which GRACE can identify the shrinkage of ice sheets and land ice (ice sheets, icefields, ice caps, and glaciers) worldwide. GRACE data show that ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica have lost 280 ± 58 and 67 ± 44 Gt of ice per year between 2003 and 2013, respectively, which equate to a total of 0.9 mm yr−1 of sea-level rise.

GRACE can also determine the cause of sea-level rise, whether it is the mass of melting glaciers being added to the ocean, or from thermal expansion of warming water. Sea level has been rising globally given loses of land ice from meltwater runoff and calving of solid ice into the ocean are greater than gaining land ice through precipitation. In recent years, scientists estimated losses from land ice have been responsible for two-thirds of the observed sea-level rise (Reference CazenaveCazenave et al., 2018; Reference Chen, Wilson and TapleyChen et al., 2013). For example, using RL05 GRACE data for 2003–2012, Reference Velicogna and WahrVelicogna and Wahr (2013) found a mass loss of 258 ± 41 Gt yr−1 for Greenland, with an acceleration of 31 ± 6 Gt yr−2, and a loss that progressively affect the entire periphery. For Antarctica, they found a loss of 83 ± 49 and 147 ± 80 Gt yr−1, with an acceleration of −12 ± 9 Gt yr−2 and a dominance from the southeast pacific sector of West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula. The successor of GRACE, GRACE-FO, or GRACE Follow-On was launched on May 2018 to continue monitoring Earth’s gravity and tracking changes in global sea levels, glaciers, and ice sheets, as well as large lake and river water levels, and soil moisture.

The recently launched ICESat-2 (Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite-2) satellite carries a photon-counting laser altimeter to measure the height of a changing Earth, for example, the elevation of ice sheets, glaciers, sea ice, and more in unprecedented details by 10,000 laser pulses a second. Our planet’s frozen and icy polar regions, called the cryosphere, are particularly sensitive to a warming climate. For instance, Arctic amplification is climate change impact amplified in the Arctic, which has been warming at about twice the global rate since 1980s, caused by several feedback mechanisms, namely, ice–albedo, temperature (Planck and Lapse rate), water vapor, CO2, and cloud feedbacks. Therefore, how much and how fast is our cryosphere changing under a warmer climate is of significant interest to us. ICESat-2 has four science objectives: (1) estimate how melting ice sheets contribute to sea-level rise; (2) measure signatures of ice-sheet changes to assess the mechanisms driving those changes; (3) estimate sea ice thickness to examine ice/ocean/atmosphere exchanges of energy, mass, and moisture; and (4) measure vegetation canopy height to estimate large-scale biomass changes in ecosystems worldwide (IceSat-2, 2018).

CryoSat-2 is a European Space Agency environmental research satellite and part of the CryoSat programme to study the Earth’s polar ice caps (Reference Pessina and Kasten-CoorsPessina et al., 2011). It was launched on April 8, 2010 to understand how climate change is affecting marine ice floating in the Arctic Ocean, how the thickness of the ice, both on land and floating in the sea is changing for in recent years, the summer Arctic sea ice extent has been diminishing drastically, since early 2000. CryoSat-2 is used to determine if there is a trend toward diminishing ice cover by providing data about the polar ice caps and changes in the ice thickness with a resolution of about 1.3 cm. On October 22, 2010, CryoSat-2 was declared operational following six months of on-orbit testing. The main instrument of CryoSat-2 is an interferometric radar range-finder with twin antennas, which measures the height difference between the upper surface of floating ice and surrounding water often known as “free-board.”

Note 1.1

Ice: Ice is the solid phase, usually crystalline, of water. The word derives from Old English is, which has Germanic roots. There are other ices – carbon dioxide ice (dry ice), ammonia ice, and methane ice – but these will not concern us here. Ice is transparent or an opaque bluish-white color depending on the presence of impurities or air inclusions. Light reflecting from ice often appears blue, because ice absorbs more of the red frequencies than the blue ones. Ice at atmospheric pressure is approximately 9% less dense than liquid water. It is the only known nonmetallic substance to expand when it freezes.