This book focuses on inclusive, sustainable structural transformation and its financing mechanisms because conventional development aid is inadequate to address the bottlenecks to growth in many developing and emerging market economies, including those in sub-Saharan Africa. In the next few decades, the development community and governments are going to focus on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in 2030 and combating climate change as specified in COP21 objectives, both requiring huge amounts of resources. So, we need to go well beyond aid and purposefully combine aid, trade, and investment, using all financial instruments available and introducing new and innovative ones to meet the challenges of eliminating poverty and transforming industrial structures toward green and emission-reducing development. These tasks are daunting.

Aid, Trade, and Investment for Broader Development Goals

In today’s increasingly dynamic, multipolar, and yet interdependent world, a new set of broader definitions of development finance – if applied – would improve the transparency, accountability, and selectivity of development partners. It would also encourage sovereign wealth funds and foreign direct investors, among others, to invest more effectively in developing countries and to support global and regional public goods. Indeed, that is what we do in going beyond aid. We offer multiple and more inclusive definitions than suggested by, say, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD–DAC) (Lin and Wang Reference Lin and Wang2014).1 We also present future options and prospects for global governance.

Brazil, China, India, and other emerging economies provide not only new ideas, experiences, growth opportunities, and tacit knowledge but also financing for development. In the new multipolar world, BRICS countries, including China, are experiencing industrial diversification and upgrading, relocating their “comparative advantage–losing” industries to lower income countries and creating millions of jobs there. As newcomers, they are continuing to learn how to become better development partners and be more responsible stakeholders in global affairs. China in particular is also making a transition from a largely bilateral approach in development cooperation to supporting a multilateral system of cooperation.

Against a background of a plethora of recent initiatives – including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank (formerly the BRICS Bank), the China-Africa Development Fund, the Silk Road Fund, and the South-South Development Fund – we hope this book will provide a framework for analysis and discussion to guide policies and practices for South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC). That framework combines aid, trade, and investment to achieve broader development goals such as employment generation and sustainable welfare improvement.

Why Go Beyond Aid?

According to the OECD definition, Official Development Assistance (ODA) includes grants and concessional loans (with a grant element of at least 25 percent) provided by governments and used for development.2 The basic idea is that ODA must be concessional. Export credits do not count. Infrastructure loans, if not concessional enough, do not count. This definition, subject to strong criticism, has recently been revised (OECD–DAC 2014a). In our view, even the revised OECD–DAC definition is too restrictive.

Economic development is the main purpose of ODA, yet some of the more effective means of facilitating development, such as export credits and large but less concessional infrastructure investments, are excluded from the OECD–DAC definition. So this book goes beyond aid with a broader concept including trade, aid, and investment for development objectives, as long as those activities contribute to improving recipients’ well-being.

One reason is that the main players in international development finance now include countries that are both recipients and contributors of such financing. As elaborated in the New Structural Economics,3 the most effective and sustainable way for a low-income country to develop is to jump-start the process of structural transformation by developing sectors in which it has latent comparative advantages.4 The government could intervene to reduce transaction costs for those sectors by, say, creating special economic zones or industrial parks with good infrastructure and an attractive business environment. If a developing country adopts this approach, it can immediately grow dynamically and launch a virtuous circle of job generation and poverty reduction, even though its national infrastructure and business environment may be poor.

We therefore propose a model of “joint learning and concerted transformation” where all development partners are learners on an equal footing, but are learning at different speeds. Learners at different stages of development can choose different learning partners (or “teammates”) according to their own comparative advantages, “instruments of interaction,”5 and degrees of complementarity. There is a freedom of selecting partners, development strategies as well as sequencing and priorities.6 One learner could have multiple partners – upstream or downstream, North or South – each playing a mutually beneficial complementary role. Another analogy is that emerging and developing countries are at various stages of climbing the same mountain of structural transformation. In a globalized world, no one can climb that mountain without learning from and helping each other every step of the way.7

Brazil, China, India, and other emerging market economies – somewhat ahead in structural transformation – have many such instruments and high complementarities. For example, with a revealed comparative advantage in 45 of 97 subsectors, 8 and demonstrated capacities in building large infrastructure projects such as roads, ports, rail networks, and hydropower systems, China is in a position to provide ideas, tacit knowledge,9 and help releasing the “bottlenecks” that prevent many developing countries from capturing the opportunities in structural transformation. And with labor costs rising steeply in China and other emerging economies, low-income countries can benefit from attracting labor-intensive enterprises that are relocating to places with lower labor costs (Lin Reference Lin2012c; Lin and Wang Reference Lin and Wang2014).

Importantly, our model is market-based one, based on “exchanging what I have with what you have,” signifying mutual exchange on an equal footing. Following comparative advantages in trade and cooperation, both sides can gain from this trade, as we learn from Adam Smith. This could potentially align the interests of all partners – North or South, rich or not so rich, multilateral or bilateral – working together to try to reach “multiple win” solutions (Lin and Wang Reference Lin, Wang, Lin and Monga2015).

A second reason this book goes beyond aid is that traditional development aid from the advanced countries has not been effective for poverty reduction, primarily because it was not used for structural transformation. If that traditional aid had been directed to augmenting the resources under the command of governments to ease the bottlenecks to growth in sectors with latent comparative advantages, it would have been better at reducing poverty and achieving inclusive and sustainable development in low-income countries. Examples include improving infrastructure for special economic zones and building roads to ports.

In the past 30 years, China achieved the most rapid economic growth and poverty reduction – it alone accounted for most of the decline in extreme poverty over the past three decades. Between 1981 and 2011, 753 million people in China moved above the $1.90-a-day threshold. During the same time, the developing world as a whole saw a reduction in poverty of 1.1 billion (World Bank 2016).10 Developing countries are looking at China’s experience to see what has worked and how effective these policies are.

To end absolute poverty by 2030, international aid must be used in the context of other resources such as non-concessional loans, direct investment, and government spending (Development Initiatives 2013). Where aid is more effective – as in the Republic of Korea, China, Vietnam, and India – it has been used together with trade, foreign direct investment, commercial loans for infrastructure, bond and equity investments, and concessional or non-concessional export credit. Indeed, separating aid from trade and investment goes against market orientation.

A third reason is that South-South Development Cooperation would be most effective for poverty reduction in a poor country if it created a home-grown or local (not national) enabling environment for dynamic structural transformation in an economy characterized by poor infrastructure and distorted institutional environment. This solution to promote industrial clustering and agglomeration is more effective in low-income countries.11

A dynamically growing developing country is in the best position to help a poor country to jump-start dynamic structural transformation and poverty reduction: It can share its experience of building a localized enabling environment in special economic zones or industrial parks, and it can relocate its labor-intensive light manufacturing industries to the poor country in a “flying geese pattern” (Lin Reference Lin2012c).

This book shows that South-South Development Cooperation from China and other emerging market economies is more likely to bring “quick wins” in poverty reduction and inclusive, sustainable growth. These economies, and especially China, have comparative advantages in infrastructure sectors, including construction material industries and civil engineering, fostered through grants, loans, and other financial arrangements, in a win-win for both sides. These economies, again China particularly, are relocating their light manufacturing, export-processing industries to low-income countries – industries in which the low-income countries have a latent comparative advantage. History suggests that any low-income country that can capture these relocating light manufacturing industries can have dynamic growth for several decades as it becomes a middle-income or even a high-income country.

The book also shows that Brazil, China, India, and other emerging market economies will, as newcomers, continue to learn to become better development partners and more responsible stakeholders in global affairs. “One cannot learn how to swim without jumping into the sea,” as the Chinese proverb says. The new development banks and funds are steps in such a learning process.

Sometimes, emerging market economies need to be helped by other partners on social and environmental standards, safeguards, and risk management. Here, the international development community, nongovernmental organizations, and civil society come into play. All partners, in different positions in the development process, need to keep an open mind on South–North or trilateral cooperation, to ensure that it promotes “modern multilateralism.” In a multipolar world, the emergence of new multilateral development institutions is inevitable and brings new momentum, energy, and competition to the development arena.

This short book does not attempt to cover all areas of foreign aid, nor does it present a comprehensive development framework, as foreign aid is closely related to the foreign policy of a country and wider issues of political economy. The book does not examine humanitarian aid, since that is guided by principles different from those of development aid and cooperation, nor is it an overview of China’s foreign aid.12 Instead, it studies the economics of development aid and cooperation from the angle of structural transformation, since ODA as currently defined and applied is ineffective for structural transformation (Chapter 3). It is time for the international development community to move on to new definitions that are broad enough to include multiple forms of SSDC, to facilitate triangular learning and cooperation, and to support low-income countries in capturing their windows of opportunity.

The Start of a New Era in 2015

The global development process seems to have reached a turning point. Never before did the balance of power shift as much as in March 2015, when 57 countries, including the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and many other European states became the founding members of the AIIB. More than 30 countries are waiting to join in 2016.

In our view, this shift represents a new era of globalization where southern countries are playing an increasingly important role. It also signifies a major change in China’s development cooperation from bilateralism to multilateralism, as it deepens South-South and trilateral cooperation. Having experienced many frustrations in reforming the current multilateral development organizations, China is taking a greater leadership role in global development – forming multilateral financial bodies to reflect its development ideas, experience, and tacit knowledge. Building on many years of successful development, China is confident of the positive impact it can have on global development.

Nearly eight years after the global financial crisis broke, recovery is still anemic despite years of zero interest rates. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) adjusted downward the growth rates of all industrial countries in April 2016. Monolithic explanations of international development seem to fail in describing today’s multipolar world. Some world-renowned economists are discussing the possible “secular stagnation” of industrial countries.13 Having lost confidence in the Washington Consensus14 in the great recession, developing countries are increasingly looking to the East for experiences and ideas – for what has worked, why, and how.

China, based on its thousands of years of uninterrupted civilization and its recent 36 years of economic success, proposes a grand vision: “The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” (One Belt, One Road). It focuses on connectivity, infrastructure development, and structural transformation, with the AIIB and the Silk Road Fund as two of its funding mechanisms. This vision and new proposals by Chinese President Xi Jinping in September 2013 have won the hearts and minds of some developing and industrial countries, in Asia and beyond.

What is the rationale behind One Belt, One Road? We believe, first, that the vision reflects not only strong demand from countries overcoming infrastructure bottlenecks and improving connectivity, but also China’s own key ideas and experiences for economic development. Building infrastructure sooner rather than later could facilitate trade at lower cost (Chapter 5). And building bottleneck-releasing infrastructure as a countercyclical measure could boost aggregate demand and long-term productivity. China has used expansionary monetary, fiscal, and investment policy to overcome contractionary pressures during two crises – 1998 (in Asia) and 2008–2009 (globally). The International Monetary Fund (IMF), after resisting for many years, has finally accepted the idea of building infrastructure as a countercyclical measure in a low interest rate environment,15 and even recommends it (IMF 2014; See also Chapter 3, this volume).

We also believe that One Belt, One Road makes concrete the desires of Chinese leaders for “peaceful coexistence with differences” and commitments for providing global public goods, peace, security, and sustainability. China has provided development cooperation since the 1950s, when its per capita income was only one-third of Africa’s. It has followed a revived Chinese value system of ren and yi (仁,义), which has rich meanings of several layers. One layer implies that “one wishing to be successful oneself seeks to help others to be successful; and one wishing to develop oneself seeks to help others to develop” (“己欲立而立人,己欲达而达人”). Another layer implies that “one should not impose on others what oneself does not desire” (“己所不欲,勿施于人”).

These values were reflected in the Bandung principles of mutual respect and reciprocal non-interference, agreed at Bandung Conference in 1955, and they have been consistently implemented by China’s foreign aid policy in the last 60 years. They will be modernized and strengthened by the current generation of leaders, as shown by the recent commitments to support global public goods and tackle climate change. “China now has its basic interest and responsibility in the systemic functioning of global development financing,” as Xu and Carey (Reference Xu and Carey2015a) observed. As Chinese President Xi said in his interview in the Washington Post published on February 12, 2012, “The vast Pacific Ocean has ample space for China and the United States.” In the same vein, our view is that the vast oceans are large enough to allow many developing nations to emerge peacefully – and that China’s rise is conducive to world development and peace.

On the economic front, some of the considerations that motivated us to write this book are that

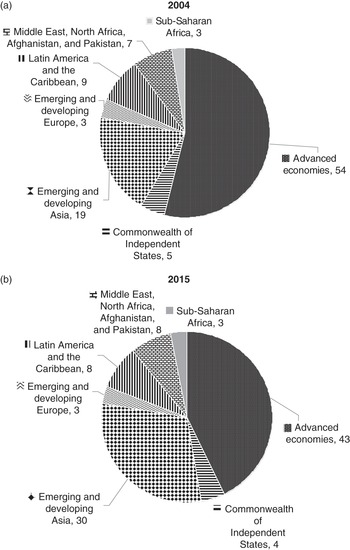

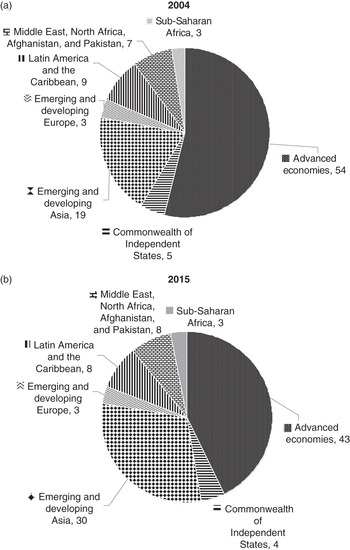

Emerging and developing countries now account for more than 57 percent of global GDP; the advanced industrial countries account for less than 43 percent (Figure 1.1).

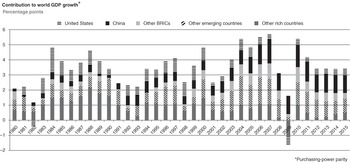

In the 1990s, developing countries accounted for about a fifth of global growth. Today, emerging and developing countries account for two-thirds of global growth and are driving the global economy. China alone accounts for more than 30 percent of global growth. Given its economic size, 6.5 to 7 percent annual growth in China produces one-fourth to one-third of global growth (Figure 1.2).

Over past 10 years, emerging economies have become major sources of international development finance, infrastructure investment, and outward foreign direct investment. The IMF finds, “In recent years, China has become the largest single trading partner for Africa and a key investor and provider of aid,” and “a 1 percentage point increase in China’s real domestic fixed asset investment growth has tended to increase sub-Saharan Africa’s export growth rate on average by 0.6 percentage point” (IMF 2013, p. 5).

China has become the largest financier of Africa’s infrastructure, accounting for around one-third of total financing (Chen Reference Chen2013; Baker & McKenzie 2015). Chinese banks have provided around US$132 billion in financing to Africa and Latin American countries since 2003 (Braütigam and Gallagher Reference Braütigam and Gallagher2014; Braütigam Reference Braütigam2016; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2016).

China’s outward non-financial direct investment has risen from a few million dollars in the 1990s to US$118 billion in 2015 and $89 billion in the first half of 2016 (MOFCOM 2016).16 Much of it is in economic infrastructure and manufacturing.

Figure 1.2 Contributions to world GDP growth, 1980–2015

What Was Missing in the Previous Era? And How to Respond?

We are all beneficiaries of learning from the economic literature and international experiences in development. With the benefit of hindsight and standing on the “shoulders of giants,” we examine the literature of international aid and aid effectiveness (which is newer than that on the economics of development). Such literature seems, however, to have focused on established donors’ behaviors: who provides aid, donor objectives and motivations, the conditions for aid, and aid effectiveness. Very little economic work has been done on the conceptual and theoretical foundations of development finance provided by emerging economies from the “Global South.”

The extensive recent literature on aid effectiveness includes Boone (Reference Boone1996); Burnside and Dollar (Reference Burnside and Dollar2000); Easterly et al. (Reference Easterly, Levine and Roodman2003); Easterly (Reference Easterly2003, Reference Easterly2006, Reference Easterly2013); Collier (Reference Collier2007), Collier and Hoeffler (Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004); Rajan and Subramanian (Reference Rajan and Subramanian2008); Roodman (Reference Roodman2007); Arndt et al. (Reference Arndt, Jones and Tarp2010); Moyo (Reference Moyo2009); Deaton (2013); and Edwards (Reference Edwards2014a and Reference Edwards2014b). One group of studies, addressing the issue of absorption and capital flight, asks, “Where did all the aid go?”17 Only a few authors have focused on the institutional economics of aid (such as Martens et al. Reference Martens, Mummert, Murrell and Seabright2002), and more recently on the sectoral allocation of foreign aid, growth, and employment (Akramov Reference Akramov201218; Van der Hoeven Reference Van der Hoeven201219).

Martens et al. (Reference Martens, Mummert, Murrell and Seabright2002) highlighted the “principal-agent” problems in the “donor-recipient” relationship and found that “the nature of foreign aid – with a broken information feedback loop … put a number of inherent constraints on the performance of foreign aid programs. All these constraints are due to imperfect information flows in the aid delivery process” (p. 30). They quoted Streeten’s famous question on aid with conditionality: “Why would a donor pay a recipient to do something that is anyway in his own interest? And if it is not in his own interest, why would the recipient do it anyway?” (Martens et al. Reference Martens, Mummert, Murrell and Seabright2002, p.9). Their study pointed squarely to one of the basic dilemmas in modern ODA – the nonaligned incentives between donors and recipients.20

Indeed, the imperfect information and the agency problem in aid with conditionality are under-researched. The role of the IMF and World Bank as “enforcers” of the global rules of development has been called into question by many authors. The IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) admits that the IMF made several mistakes during the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998, causing unnecessary pain. “Full capital account liberalization may not be an appropriate goal for all countries at all times, and that under certain circumstances capital flow management measures can have a place in the macroeconomic policy toolkit” (IEO 2007, 2015). After the release of a staff paper on capital control (Ostry et al. Reference Ostry, Ghosh, Habermeier, Chamon, Qureshi and Reinhardt2010), Rodrik called the paper “a stunning reversal – as close as an institution can come to recanting without saying, ‘Sorry, we messed up’” (Rodrik Reference Rodrik and McMillan2010).

In the face of rising international financing flows to developing countries, including Africa, we believe that some elements of the current theoretical framework may be out of date. Consider three examples.

The IMF-World Bank debt sustainability framework (DSF) may be overly constraining for low-income countries because it does not take into account the dynamic impact of large infrastructure investment on long-term growth (Chapter 3).

The World Bank’s cost-benefit analysis on road projects has sometimes “forgotten” the important element of land price factors when considering the need for building a highway now, as opposed to 10 years later (Chapter 5).

The World Bank’s publication on “Long Term Finance,”(World Bank 2015) has missed an opportunity to summarize the experiences of East Asian countries, such as Singapore, the Republic of Korea, and China, which have successfully raised funds for long-term infrastructure financing through market instruments, state development banks, and sovereign wealth funds (Chapter 3).

And so it is high time for the IMF and the World Bank to “open up their kitchens” and welcome different development theories and ideas from the East as ingredients in their policy recommendations. Indeed, the dominant development paradigm seems to be changing: The IMF has started to rethink the “neoliberal agenda” that it had been pushing. A report by its research department points out, “instead of delivering growth, some neoliberal policies have increased inequality, in turn jeopardizing durable expansion.” After capital account liberalization, “Although growth benefits are uncertain, costs in terms of increased economic volatility and crisis frequency seem more evident.” (Ostry et al. Reference Ostry, Loungani and Furceri2016, p. 39). We think that democratization in development thinking is needed. Several different paradigms could coexist, and developing countries could select from the menu, based on their own developmental needs (Lin and Rosenblatt Reference Lin and Rosenblat2012).

From the angle of joint learning and concerted transformation, we argue that SSDC is more effective since these southern countries are at similar stages of structural transformation, closer together on the development path, and have similar human and institutional constraints. If they start to learn from and help each other, they would start on a more or less equal footing. They must use whatever they have and do “what they can potentially do well” – that is, develop their latent comparative advantages. Such joint learning and concerted transformation can align incentives and alleviate the principal-agent problems, the broken feedback loop, and the gaming behaviors in the aid with conditionality model (Chapters 4, 5, and 6). In Chapter 7 we discuss the new ways to overcome existing issues with South-South Development Cooperation, by using the advantage of backwardness, by targeting the sectors where an economy has latent comparative advantages,21 and by encouraging clustering and agglomeration via establishing special economic zones or green industrial parks, to reach quick wins. Chapter 8 discusses the prospects for development finance.

***

This book should interest policymakers in government, aid agencies, academics, students, international development banks such as the World Bank Group and IMF, regional development banks (including the new banks and funds), sovereign wealth funds, public pension funds, nongovernmental organizations, civil society organizations, and private sector investors.

We hope to contribute to the debate on international aid and development cooperation, to bring fresh ideas based on experiences from countries with successful structural transformation, to deepen the understanding of alternative views from emerging market economies, to play some small part in helping establish inclusive mechanisms for aid and cooperation, and ultimately to reduce poverty and sustain development in the post-2015 era.