Book contents

- Knowledge and the Gettier Problem

- Knowledge and the Gettier Problem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Introducing Gettierism

- 2 Explicating Gettierism: A General Challenge

- 3 Explicating Gettierism: A Case Study

- 4 Explicating Gettierism: Modality and Properties

- 5 Explicating Gettierism: Infallibility Presuppositions

- 6 Gettierism and Its Intuitions

- 7 Gettierism Improved

- References

- Index

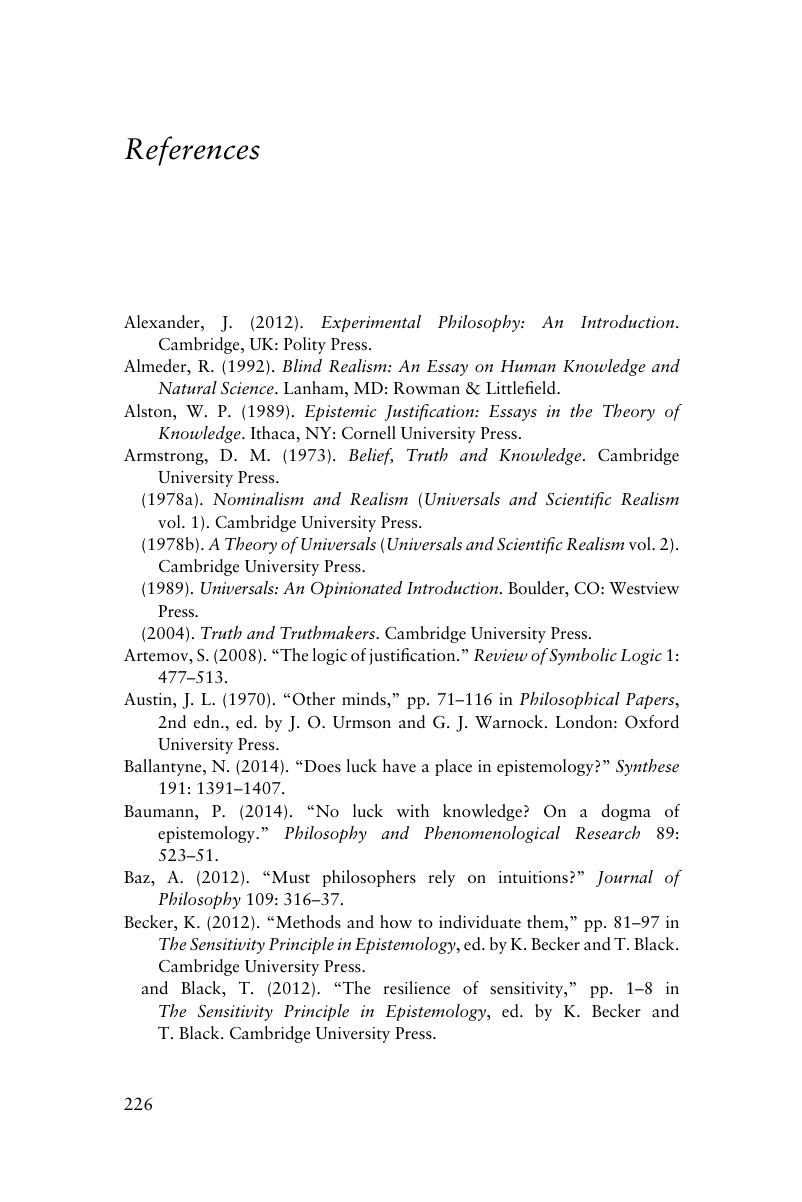

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2016

- Knowledge and the Gettier Problem

- Knowledge and the Gettier Problem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Introducing Gettierism

- 2 Explicating Gettierism: A General Challenge

- 3 Explicating Gettierism: A Case Study

- 4 Explicating Gettierism: Modality and Properties

- 5 Explicating Gettierism: Infallibility Presuppositions

- 6 Gettierism and Its Intuitions

- 7 Gettierism Improved

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Knowledge and the Gettier Problem , pp. 226 - 236Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016