The decline of Japanese labor migration to the United States ushered in a new phase in Japan’s migration-based expansion as Japanese intellectuals, policymakers, and migration promoters began to propose and carry out farmer migration campaigns in regions both inside and outside of the imperial territory. Following the failure of the rice cultivation campaign in Texas, the period between the late 1900s and 1924 was marked by two general courses of action taken jointly by Japan’s government and social groups. The first was to explore alternative routes and models of expansion, and the second was to facilitate Japanese immigrants’ assimilation into American society with the aim of placating anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States and removing the restriction on Japanese immigration. Both of these courses of action were legitimized by the logic of Malthusian expansionism.

The formation of the Japanese Emigration Association (Nihon Imin Kyōkai) in 1914 was a milestone event in the Japanese state’s involvement in migration management and promotion. As the embodiment of synergy between the government and social groups, the association worked to appease anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. Through both education and moral suasion, it carried out campaigns that aimed at helping Japanese Americans assimilate into mainstream American society. Members of the Emigration Association believed that if all Japanese men and women in the United States could behave like civilized white Americans, the Japanese race would eventually be able to gain admission to the white men’s world and anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States would automatically disappear.

In response to the decline of Japanese migration to the United States, the years following the Gentlemen’s Agreement witnessed three general campaigns of expansion launched under the collaboration of the Japanese government and private groups. These campaigns included expansion to Northeast Asia (the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria), the South Seas, and South America. As Malthusian expansionism continued to legitimize the migration-based model of expansion itself, the ongoing anti-Japanese movement in the United States became the midwife of these campaigns. All three campaigns were expected to change the image of the Japanese as an unwelcome intruder into the white men’s domain. They were aimed at directing Japanese migration to alternative political spaces beyond North America so that Japanese expansion could be tolerated by Western colonial powers.

The proposal of redirecting migration into Japan’s own spheres of influence in Northeast Asia was designed to avoid any direct confrontation with the West; the call for expansion to the South Seas, areas already under Western colonial influence, was presented as joining the West in the mission of spreading civilization to remote corners of the world; while the plan of directing migration to Latin America was based on the assumption that Latin America was still operating in a political vacuum – that is, yet unclaimed by any colonial power. The Japanese government had an unprecedented level of involvement in all of these campaigns. It sponsored semigovernmental and private associations to investigate the possibilities and means of migration and built up public appetite for expansion.Footnote 1 It also provided political and financial support for private migration companies that put these new migration plans into practice.

Japan’s efforts to placate anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States and to explore alternative migration destinations were fundamentally intertwined: both were justified as solutions to the issue of overpopulation at home. Building upon the Texas farmer migration experience, both campaigns stemmed from the belief that the project of labor migration to the United States was irrevocably flawed and should be replaced by the model of farmer migration. Moreover, Japanese expansionists believed that Japanese immigrants’ successful assimilation into American society would further facilitate Japanese expansion to other parts of the globe. Once these Japanese immigrants won the acceptance of the white Americans, it would not only justify Japanese colonial expansion as a mission of spreading civilization but also dispel the fear of the Japanese “yellow peril” among the Western powers. For this reason, in addition to leading the campaigns to facilitate Japanese American assimilation, the Emigration Association also played a central role in exploring migration destinations elsewhere.

This chapter examines the interactions and confluence of these two courses of action from the late 1900s to the mid-1920s. It shows how farmer migration, buttressed by the logic of Malthusian expansionism, became entrenched as the dominant mode of Japanese migration-driven expansion. The Japanese American assimilation campaign’s hopes were dashed by the Immigration Act of 1924, which closed US doors to all Asian immigrants. The collaborative efforts made by the government and social groups in migrant expansion to Northeast Asia and the South Seas also resulted in disappointment. However, the initial success in farmer migration in Brazil invited an increasing number of Japanese expansionists to cast their gaze to the biggest country in South America.

The Beginning of Japanese Farmer Migration in Northeast Asia

After the Russo-Japanese War cemented Japan’s political ascendancy in Northeast Asia, the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria became convenient alternatives to North America following the demise of the Texas campaign and the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement. The most famous proponent for Japan’s expansion into Northeast Asia was Komura Jutarō, the minister of foreign affairs in the second Katsura Cabinet, who proposed the strategy of “concentrating on Manchuria and Korea” (Man Kan Shūchū) in a speech to the Imperial Diet in 1909. The formation of the Oriental Development Company (Tōyō Takushoku Kabushiki Gaisha) in 1908, under the political and financial support of the Prime Minister Katsura Tarō, brought the proposal of Northeast Asian expansion into action. The company acquired farmland on the Korean Peninsula, recruited Japanese farmers, and settled them there.Footnote 2

Japan’s migration-based expansion in Northeast Asia, both in ideology and in practice, was a replica of the failed Texas migration campaign, in terms of both the discourse of Malthusian expansionism and the idea of farm migration. Komura, for example, reasoned that the spacious land in the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria would be more than enough to accommodate Japan’s surplus population. He further argued that migration would also help to stimulate Japanese population growth by an extra thirty million.Footnote 3

The idea of farmer migration to the Korean Peninsula was further articulated by Kanbe Masao, a professor of law at Kyoto Imperial University. He published On Agricultural Migration to Korea (Chōsen Nōgyō Imin Ron) in 1910, on the eve of Japan’s formal annexation of Korea. Like Komura, Kanbe believed that instead of Hawaiʻi, the US mainland, or Latin America, the Korean Peninsula should be the premier destination for Japanese migrants. For Kanbe, agricultural migration from Japan to Korea was not merely a solution to the issue of overpopulation but also a mission of spreading civilization because the unenlightened and incompetent Koreans had to be guided by the Japanese in order to cultivate their own land.Footnote 4

In addition, the proposal of expansion into Northeast Asia was also a strategic response to anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. It was in line with Komura’s acceptance of the Western imperialist world order and his efforts to gain Japan entry to the club of civilized powers. A longtime diplomat, Komura played a key role in forming the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902 and in renewing it in 1911. In 1907, while serving as Japan’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, he contributed to Japan’s diplomatic efforts to placate the anti-Japanese sentiments in Canada.Footnote 5 Taking the cabinet post of minister of foreign affairs soon after the Gentlemen’s Agreement was reached, Komura fulfilled the government’s promise to ban Japanese labor migration to the United States. Adopting a pro-Anglo-American stance, he proved instrumental in negotiating the Root-Takahira Treaty with the United States in 1908. The treaty clarified the two countries’ colonial privileges in the Asia-Pacific region in order to avoid possible conflicts between these two Pacific powers.Footnote 6 For its part, the policy of Man Kan Shūchū was in line with Katsura Cabinet’s efforts to find a way for Japan to expand without rousing American suspicion and hostility.Footnote 7

As will be discussed in the following paragraphs, Komura’s notion of achieving conciliation with the United States in exchange for Japan’s membership in the club of civilization was shared by contemporary advocates for Japan’s southward expansion (nanshin) in the South Seas. These campaigns for exploring alternative routes of expansion were intertwined with Tokyo’s efforts in facilitating Japanese American assimilation. During the interactions between the course of exploring alternative routes of expansion and that of fostering Japanese assimilation into the American society, farmer migration with the goal of permanent settlement was further solidified as the most desirable mode of Japanese expansion in the following decades.

White Racism and Malthusian Expansionism: The Formation of the Emigration Association

In the history of Japan’s migration-driven expansion, if the campaign of Texas migration marked the beginning of the paradigm shift from labor to agriculture, the enactment of the Alien Land Law in California in 1913 was another critical event. Aimed at excluding Japanese farmers from the domestic agricultural sector and creating a social climate that was pointedly inhospitable for immigrants, the California Alien Land Law of 1913 denied issei Japanese Americans the right to land ownership and restricted their legal tenancy to three years. It not only damaged the agricultural development of Japanese American communities but also gave a bitter lesson to the Japanese Malthusian expansionists about the importance of land ownership. It thus further cemented the centrality of land-acquisition-based farmer migration in the history of Japanese migration-driven expansion in the following decades.

In response to the Alien Land Law, Japanese politicians and social groups redoubled their efforts to placate anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. Entrusted by business tycoon Shibusawa Ei’ichi, the first president of Industrial Bank of Japan (Nihon Kōgyō Ginkō), Soeda Jū’ichi and Kamiya Tadao, an employee of the Brazil Colonization Company, went to the United States to investigate the issue.Footnote 8 Soeda and Kamiya concluded that a moral reform was needed to “civilize” Japanese immigrants because their backward behaviors and lifestyle had been fueling anti-Japanese sentiment. Based on this conclusion, Shibusawa, Soeda, and Nakano Takenaka – the director of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce – jointly submitted two proposals to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The first proposal contained their plans to smooth over anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States, including promoting mutual understanding between the two nations and turning Japanese Americans in the United States into better civilized subjects. The second proposal, however, called for looking to the South Seas and Latin America as alternative destinations for Japanese migration in the following decades.

These two proposals found supporters within the imperial government. In 1914, the government and social groups collaborated to form the Japanese Emigration Association to facilitate Japanese overseas migration and expansion by giving public lectures, conducting workshops, and publishing journals/books on the subject. Its members included top government officials, Imperial Diet members, business elites, intellectuals, and migration agents.

The inaugural meeting of the Emigration Association was held in the hall of Tokyo Geographical Association,Footnote 9 the founding site of the Colonial Association (Shokumin Kyōkai), and there were indeed parallels between these two organizations. Like the Colonial Association, the Emigration Association was formed in response to Asian exclusion campaigns in the United States, and both membership rosters included Japanese politicians, social elites, and intellectuals. Members of the Emigration Association supported migration for different purposes: policymakers saw migration as essential for expansion, business tycoons expected it to boost international trade, while intellectuals believed it would make Japan rise through the global racial hierarchy. Yet as a whole they were, like the Colonial Association members before them, adherents to Malthusian expansionism who lamented the issue of overpopulation in Japan but simultaneously avowed the necessity of further population growth.

As the manifesto of the Emigration Association claimed, among the nations of the world, the Japanese nation had an outstanding population growth rate as well as impressive population density. The goal of the association was to facilitate overseas migration so that the nation would not be mired in poverty and revolutions. Emigration, however, was not simply aimed at offloading of the surplus population. As the founders of the association also emphasized in the manifesto, “Western scholars often use the terms of colonial nation (shokumin koku) and non-colonial nation (hi shokumin koku) to differentiate successful nations from the unsuccessful ones.” As a few European empires continued to strive as colonial nations, “Japan and the U.S. also began to take part in this imperial competition.” The association’s mission, then, was to serve Japan’s national interests by facilitating migration-based expansion and cementing Japan’s status as a member of the colonial nations’ club.Footnote 10

While the Colonial Association aimed to promote shizoku expansion in order to prepare for racial competition with the West, the Emigration Association was founded when anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States was at its peak. Yet instead of adopting a combative stance toward the West, the association hoped to keep the general avenues of Japanese overseas migration open by reconciling with Anglo-American colonial hegemony. Members of the association believed that widening the channel for Japanese immigration into the United States was not only crucial for Japan’s future expansion but also feasible in practice. As Soeda Jū’ichi articulated, they were optimistic for two reasons. First, they denied the existence of racism against Japanese among white Americans and argued that Japanese immigrants themselves should be blamed for anti-Japanese sentiment because of their lack of social manners and backward lifestyle. As they saw it, at the heart of the problem was the insular national character of the Japanese, a product of the long-term isolationist (sakoku) policy of the backward Tokugawa regime. If this trait could be altered, then the anti-Japanese sentiment would disappear.Footnote 11 Second, they perceived World War I as a turning point that would lift the migration restriction in the United States: as the European battlefields demanded manpower, the flow of European migration to the United States would dry up after the war began, and Japanese immigrants would thus again be welcomed to fill the labor vacuum. In addition, Japanese Canadians who voluntarily joined the Canadian military to fight in the war would also improve Japan’s international image.Footnote 12

In the Emigration Association’s blueprint for Japanese global expansion, the removal of migration restrictions in the United States was of paramount importance. This was not only because the United States still had spacious, fertile, and sparsely populated land, but also because the acceptance of Japanese immigrants by Americans would provide irrefutable evidence for Japan’s status as a civilized nation equal to the Westerners. It would legitimize Japan’s expansion in the future by opening the doors of other countries, both “civilized” and “uncivilized” alike, to Japanese migration. As the director of the Emigration Association Ōkuma Shigenobu envisioned, American acceptance of Japanese immigration would prove that Japan was capable of synthesizing the essences of the East and West. Standing on the top of the hierarchy of civilizations, Japan’s expansion was destined to bring enlightenment to the entire world.Footnote 13

The Enlightenment Campaign for Japanese American Assimilation and Women’s Education

Members of the Emigration Association such as Shibusawa Eiichi and Soeda Jū’ichi played leading roles in the enlightenment campaign (keihatsu undō), a collaborative initiative launched by government officials and social leaders in Japan as well as Japanese Americans community leaders. It employed a two-pronged approach to achieve its goal of Japan-US conciliation that included both “external enlightenment” (gai teki keihatsu) and “internal enlightenment” (nai teki keihatsu). The former sought to improve the image of Japan and Japanese among the white Americans by increasing commercial, religious, and cultural exchanges between Japan and the United States. The latter, on the other hand, was targeted at the Japanese immigrants in the United States. If the Japanese immigrants’ “problems” could be corrected, the campaign leaders believed, the anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States would naturally give way to acceptance. To this end, they identified a variety of problems common to Japanese Americans. These issues included ignorance of American customs, inadequate English proficiency, insufficient interaction with white Americans, engagement in gambling and prostitution, as well as reluctance to make social investment in the United States.Footnote 14

In the campaign leaders’ blueprint of civilizing the Japanese American communities, women played a critical role. Though Shimanuki Hyōdayū, the first president of the Japanese Striving Society, died as early as 1913 and was not an official participant in the enlightenment campaign, his ideas on how women could contribute to the Japanese American assimilation actually set the agenda for the enlightenment campaign. Between the late 1900s and early 1920s, Japanese women began to migrate to the United States as marriage partners of the Japanese male immigrants in a growing number. This was because the Gentlemen’s Agreement shut the American doors to Japanese migrant laborers but left them open to family members of the existing immigrants. Responding quickly to this situation, Shimanuki started raising fund for the establishment of women’s school (Rikkō Jogakkō) inside the Striving Society in 1909, which became true at the end of that year.Footnote 15 Referring to their racial struggles in the United States, Shimanuki argued, the Japanese American immigrants were fighting a peaceful war, one as significant as the Russo-Japanese War. To support their battle to win the Japanese race deserved recognition from the white Americans, the society was dedicated to facilitating the migration of Japanese women to the United States so that they could become marriage partners and domestic assistants to male immigrants.Footnote 16

The migration of Japanese women, Shimanuki reasoned, would placate anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States in two ways. First, the most important reason for the overall success in the worldwide colonial expansion of the European powers was that the male settlers migrated overseas with their wives. Just like the wives of the European colonial settlers, the Japanese women could give their husbands in the United States physical assistance and emotional comfort to overcome the material difficulties and loneliness in the foreign land. This family life would not only help the Japanese male immigrants to restrain themselves from indulgence in immorality and crimes but also solidify their resolution of permanent settlement in the United States. The improvement of Japanese immigrants’ lifestyle would change the white Americans’ attitude toward Japanese immigration. Second, women could also give birth to the next generation of the Japanese in the United States, who enjoyed the birthright citizenship and political rights attached to it. Because most of the first generation of Japanese immigrants had no access to US citizenship, the more children they had, the stronger the Japanese American communities would become politically. The growth of Japanese population with citizenship would prevent anti-Japanese campaigns from having political consequences.Footnote 17 However, for Shimanuki, not all Japanese women were qualified to take on this mission. Only those who were physically and mentally ready were qualified. The goal of the Women’s School of the Japanese Striving Society was to prepare these women to become good wives and mothers in the frontiers of Japanese expansion before their migration.Footnote 18

In the minds of the leaders of the enlightenment campaign, the female migrants were far from ready to take on this glorious mission. Most of the Japanese women who reached the American shore between late 1900s and early 1920s were picture brides (shashin hanayome) from poor families in rural Japan.Footnote 19 Japanese educators criticized them for bringing shame on the Japanese race and nation because of their “inappropriate” manners and “outdated” makeup and dress. Kawai Michi, national secretary of Japanese Young Women’s Christian Association (JYWCA) and a central figure in the enlightenment campaign, attributed American anti-Japanese sentiment in part to the “uneducated” behavior of these women. Having studied in the United States under the support of the scholarship established by Tsuda Umeko, Kawai firmly believed that the image of a nation was judged by the education level of its women. Under her leadership, the JYWCA and its main branch in California initiated education campaigns to discipline picture brides so that they could represent Japan in more desirable ways.Footnote 20 With support from the local government and politicians, the JYWCA established an emigrant women’s school in Yokohama, providing classes on housework, English, child rearing, American society, Western lifestyles, and travel tips for the picture brides before they left for the United States.Footnote 21 Besides training, the JYWCA disseminated pamphlets with similar guidance among emigrant women. The JYWCA’s California branch also offered accommodation and similar training to picture brides after their arrival.Footnote 22 Through these efforts, the campaign leaders expected to showcase civilized Japanese womanhood to the white Americans.

In addition, the female migrants were also expected to solidify families and give birth to children for Japanese American communities. For this reason, the mission of disciplining rural women’s wrongdoings did not stop at correcting their manners in daily life but went as far as regulating their marriage and occupation. Owing to limitations of communication and understanding between the two sides before marriage, not all marriages of Japanese immigrants ended happily. In order to find a good partner, some Japanese male immigrants used fake pictures to appear younger and more handsome than they really were. Others lied about their financial situation, claiming that they were successful businessmen or rich landowners, while in reality they were merely agricultural laborers.Footnote 23 As a result, many picture brides felt either disappointed or cheated when they faced reality. Since there were far fewer women than men in Japanese communities in California, it was relatively easy for a single female to find a job and live by herself. Some disappointed brides thus chose divorce.Footnote 24 Leaders of the enlightenment campaign attributed these wife-initiated divorces to “the weakness of Japanese females” and “degradation of female morality.”Footnote 25 They warned that these “degraded women” were the cause of American anti-Japanese sentiment, and urged all Japanese immigrant women to remain loyal to their husbands and fulfill their duty to raise children.Footnote 26 Local Japanese Christian women’s homes sometimes even intervened and managed to prevent such divorces.Footnote 27

Responding to financial difficulties and the hardship of agricultural life, most Japanese immigrant women living in rural areas had no choice but to work in the fields with their husbands.Footnote 28 White exclusionists accused them of transgressing gender boundaries, in which a man should be the only breadwinner while a woman should stay at home taking care of the family. They described the Japanese women in the field as the slaves of their husbands and attributed such “transgression” to the racial inferiority and uncivilized tradition of Japanese immigrants.Footnote 29 Replicating claims of the exclusionists, Kawai argued that if women went out to work, their housework and child-rearing duties would be neglected. She maintained that Japanese female immigrants’ farm work was driven by their greed for money and assumed that it was a cause of American anti-Japanese sentiment.Footnote 30

Permanent Settlement and the Intellectual Shift from “Increasing People” to “Planting People”

This campaign of educating Japanese picture brides in the United States was also part of the ideological transition of Japanese expansionism in response to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment in North America. The threat of racial exclusion in the United States reminded the expansionists in Tokyo the importance of permanent settlement of the Japanese migrants abroad. Unlike Ōkawadaira Takamitsu and Tōgō Minoru who called for Japanese expansion elsewhere in the late 1900s, the enlightenment campaign’s goal was to remove the restrictions on Japanese migration to the United States. Yet the enlightenment campaign was also an offspring of the intellectual debates since the late 1900s that attempted to make sense of the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. Replicating the ideas of Ōkawadaira and Tōgō, the campaign leaders identified the immigrants’ sojourner mentality (dekasegi konsei) as the root of all evil, thus they believed that the ultimate solution was for the immigrants to commit to permanent settlement. As rural peasants came to constitute the majority of the migrant population and the domestic rice riots continued, agricultural settlement was naturally favored by the campaign leaders as the most desirable model of migration. In their minds, the enactment of the California Alien Land Law of 1913 reinforced the central importance of land ownership in order for Japanese immigrants to succeed in permanent settlement.Footnote 31

To prepare migrants for the long-term commitment, the campaign leaders stressed the importance of training the migrants before they left Japan. To this end, the Emigration Association held regular lectures in Tokyo and Yokohama, published journals and books that disseminated migration-related information, and organized annual workshops from 1916 to 1919. These workshops were attended by teachers from high schools and professional schools throughout the archipelago.Footnote 32 The association also established an emigration training center in Yokohama in 1916, directly offering emigrants classes on social manners, hygiene, foreign languages, child rearing, and housework. Over four hundred migrants – two-fifths were women – attended the classes at the training center within two months after it opened. The center was jointly founded by funds from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and donations from entrepreneurial tycoons. Nagata Shigeshi, the president of Japanese Striving Society, served as its first director.Footnote 33

The Japanese expansionists’ growing interest in permanent settlement was reflected by the ascendency of the term 植民 over 殖民 when referring to the concept of colonial migration. As written forms for the concept shokumin, the Japanese translation for the Western word “colonization,”Footnote 34 both terms first appeared during the early Meiji era. Even though their characters (kanji) differed, the Meiji intellectuals at times used the two terms interchangeably because they shared the same pronunciation, a common practice in the modern Japanese language.

The word 殖民, with the implication of reproducing, clearly dominated in governmental documents and intellectual works throughout most of the Meiji period – as the first chapter of this book had illustrated, Meiji colonial expansion was developed hand in hand with the original accumulation of modern Japanese capitalism. However, 植民 gained increasing popularity among Japanese intellectuals in response to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States in the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 35 The first Japanese book that adopted 植民 instead of 殖民 was On Japanese Colonial Migration (Nihon Shokumin Ron), authored by Tōgō Minoru in 1906. As the previous chapter showed, while Tōgō did not explain his choice of wording, this book marked only the beginning of the Japanese expansionists’ intellectual exploration of the model of permanent migration. In 1916, Nitobe Inazō, Tōgō’s coadvisor at Sapporo Agricultural College, penned an article that clarified the difference between these two written forms. As Nitobe pointed out, while 殖民 was a combination of the character 殖, literally meaning “reproducing,” with the character 民, literally meaning “people,” 植民 was a combination between 植, with the meaning of “planting,” with “people,” 民.Footnote 36 The fact that Nitobe used 植民 instead of 殖民 throughout the article demonstrated that the choice of this written form was deliberate. From the 1900s onward, 植民 gradually replaced 殖民 as the written form of shokumin in Japanese. Its increasing popularity among Japanese expansionists mirrored the affirmation of agriculture-centered permanent migration as the dominant model of Japanese expansion throughout the Taishō and early Shōwa years.

Japanese Expansion in Northeast Asia and the South Seas

The transformation in the discourse of Japanese expansion was further solidified by Japan’s participation in World War I (1914–1918). As historian Frederick Dickinson forcefully argues, this first global war offered Japan a golden opportunity to join the club of modern empires as a valuable member.Footnote 37 Although its proposal to write the clause of racial equality into the charter of the League of Nations was rejected at the Paris Peace Conference, Japan, as a victor of the war, was able to secure a position of leadership in the postwar world as a charter member of the league.Footnote 38 It was also rewarded with Germany’s colonies in Micronesia and colonial privileges in the Shandong Peninsula in China. At the turn of the 1920s, it seemed that Japan had much to gain and little to lose by embracing the new world order. Under Anglo-American hegemony, this new order professed to reject territorial expansion in favor of peace and cooperation. Japan had to halt its military expansion, but migration with the expectations of permanent settlement and local engagement seamlessly fitted into this new world order as a peaceful means of expansion.Footnote 39 Thus the years during and right after World War I witnessed increased Japanese efforts to expand via alternative routes by nonmilitary means.

The career trajectories of individual members of the Emigration Association around this time demonstrate how the Japanese American enlightenment campaign was intertwined with Japanese expansion campaigns in other part of the world that emerged at this time. Ōkuma Shigenobu, the president of the Emigration Association, was a long-standing advocate of Japanese conciliation with the West. Ōkuma was a passionate supporter of the enlightenment campaign, and his promotion of Japanese immigrants’ assimilation into white society was tied to his agenda of integrating Japanese expansion in Northeast Asia into the existing imperial world order. It was also Ōkuma who, during his tenure as the prime minister of Japan, forced the Yuan Shikai regime to accept the Twenty-One Demands in order to deepen Japan’s political and economic penetration in China while avoiding challenging the Western powers’ existing colonial interest in China.Footnote 40 The aim of Japanese expansion in Northeast Asia, Ōkuma argued, should not only be solving the issue of domestic overpopulation and food shortage; Japan also needed to contribute to the economic prosperity and peace of local societies.Footnote 41

The call for expansion to the South Seas emerged prior to the first two decades of the twentieth century – the Seikyō Sha leaders in the 1890s had advocated nanshin as a way to prepare Japan for the inevitable race war against the West. However, the later proposals of expansion to the South Seas were shaped by the experiences of Japanese American enlightenment campaign and World War I. As a result, this new discourse of southward expansion was centered on cooperation with the Western powers instead of challenging them. Takekoshi Yosaburō, a politician-cum-journalist and member of the Emigration Association, was a leading proponent of this trend of thought. In order for Japan to shed its image of the invader (as American exclusionists described Japan), Takekoshi argued, Japan’s expansion must be carried out not via military invasion but instead by focusing on bringing civilization to the world: while Japan was a latecomer to the civilized world, it was now already a full-fledged member, thus it was time for the Japanese to partake in carrying the “White Man’s Burden” (Hakujin no Omoni).Footnote 42 The ideal direction for such a Japanese expansion was southward. Its targets included the South Pacific islands, originally proposed by the nanshin thinkers in the 1880s and 1890s, and Southeast Asia, which came under the Japanese colonial gaze after the annexation of Taiwan following the Sino-Japanese War.

Takekoshi acknowledged the fact that the majority of these areas were already under Western colonial rule. Yet Westerners, he contended, were too occupied with extracting profits from the colonies and ignored the task of civilizing these backward regions. Therefore, Japan should take this opportunity to bring civilization to Western colonies, guiding local peoples to make progress in developing commerce and acquiring education. If Japan took up the task to share the blessings of civilization with the native peoples, Takekoshi argued, its expansion would no longer be met with criticism.Footnote 43

The calls for southward expansion also gained material support from the imperial government. In the 1910s, in addition to taking over Micronesia from Germany, the government also sponsored private Japanese enterprises to purchase lands for emigration in North Borneo. It also reached out to the French government in order to facilitate Japanese business expansion in Indochina.Footnote 44 Another member of the association, a politician and entrepreneurial tycoon named Inoue Masaji, played a leading role in Japanese mercantile and migrant expansion in the South Seas from the 1910s to the 1940s. He was the founder of the South Asia Company (Nan’a Kōshi), a Singapore-based Japanese trading company operating in Southeast Asia. He also cofounded the South Seas Association (Nan’yō Kyōkai), a semigovernmental association that promoted Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific.Footnote 45 He later became the head of the government-sponsored Overseas Development Company (Kaigai Kōgyō Kabushiki Gaisha) and was in charge of the majority of the activities in Japanese Brazilian migration throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

The empire’s expansion in Northeast Asia and the South Seas in the 1910s provided new colonial privileges for Japanese agricultural migrants. Japan’s annexation of Korea not only safeguarded the land properties previously acquired by Japanese settlers but also gave them legal privileges for further land grabbing.Footnote 46 The Twenty-One Demands allowed Japanese subjects to lease land throughout Manchuria. The empire’s annexation of German Micronesia in 1915 as a mandate territory gave Japanese expansionists a free hand for land acquisition and migration there.

However, despite the imperial government’s enthusiastic encouragement and political support by the end of the 1920s, the Malthusian expansionists were never fully satisfied with the state of Japanese agricultural migration to Northeast Asia and the South Seas. While the Korean Peninsula had one of the biggest Japanese overseas communities in the first half of the twentieth century, relatively few Japanese settlers there were farmers. Instead, they were either landlords or urbanites who worked for the colonial government and Japanese companies.Footnote 47 The Oriental Development Company had originally planned to move three hundred thousand Japanese farming households to the Korean Peninsula, but it managed to settle only fewer than four thousand households by 1924.Footnote 48 By 1931, only about eight hundred Japanese farmers were living inside Japan’s sphere of influence in Manchuria, constituting a tiny portion of the primarily urban settler population.Footnote 49

A direct reason for this failure was that Japanese agricultural settlers had serious difficulty competing with local Korean and Chinese farmers, whose cost of living and labor were substantially lower than theirs.Footnote 50 Japanese expansion to the South Seas in general primarily focused on commerce, accompanied by Japanese contract laborer migration to local sugar plantations. Specifically, Japanese farmer migration to the South Pacific began in the 1920s and the migrants mainly settled in the empire’s mandate territory in Micronesia. While the number of settlers steadily increased under governmental support from the 1920s to the end of World War II, the total size of Japanese population in the South Pacific did not exceed twenty thousand by 1930.Footnote 51

The Rise of Migration to Brazil, 1908–1924

While the migration experiments in Northeast Asia and the South Seas proved disappointing, Brazil, with its relatively friendly immigration policy toward the Japanese, turned out to be the most promising option for the Malthusian expansionists in Tokyo. Between 1908 and 1924, Japanese immigrants in Brazil not only grew steadily in number but also succeeded in agricultural settlement. In 1920, before the arrival of the bigger waves of Japanese migrants to Brazil, there were over twenty-eight thousand Japanese settlers in Brazil, 94.8 percent of whom were engaging in rural agriculture. By the time the Immigration Act of 1924 passed, the number of Japanese migrants in Brazil had already climbed to thirty-five thousand.Footnote 52 In the same year, an unprecedented number of migrants from rural Japan, fully subsidized by Tokyo, also began to arrive on the shores of the state of São Paulo. From then until 1936, Brazil remained the single country that received the most Japanese migrants outside of Asia.Footnote 53 In that year, Japanese migrants to Manchuria eventually outnumbered those to Brazil. The following pages of this chapter discuss the reasons why Japanese agricultural migration eventually found success in Brazil.

Japanese expansionists had set their sights on Brazil decades before the Russo-Japanese War. As a result of the efforts of Enomoto Takeaki and his followers, Japan established diplomatic relationship with Brazil in 1895. This was soon followed by a Yoshisa Emigration Company project that recruited 1,592 laborers from Japan to work on coffee plantations in Brazil. However, this plan was suddenly canceled by Yoshisa Emigration Company’s partner in Brazil, Prado Jordão & Company, due to the coffee market’s collapse the same year. This aborted project revealed that the Brazilian government and coffee plantation labor contractors did not take Japanese migrants seriously, as European immigrant laborers’ numbers remained high while the global coffee market continued to lag. The failure of this migration project forced the policymakers in Tokyo to suspend all future plans of migration to Brazil in order to avoid economic loss and any further damage to Japan’s international prestige.Footnote 54

Table 5.1 Annual numbers of Japanese migrants to Brazil and Manchuria in comparison (1932–1939)

| 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese migrants to Brazil | 15,092 | 23,229 | 22,960 | 5,745 | 5,375 | 4,675 | 2,563 | 1,314 |

| Japanese migrants to Manchuria | 2,569 | 2,574 | 1,553 | 2,605 | 5,778 | 20,095 | 25,654 | 39,018 |

Data regarding Japanese migrants to Brazil are drawn from Gaimushō Ryōji Ijūbu, Wa Ga Kokumin no Kaigai Hatten: Ijū Hyakunen no Ayumi –Shiryōhen (Tokyo: Gaimushō Ryōji Ijūbu, 1972), 140. Data regarding Japanese migrants to Manchuria are drawn from Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 395.

After the Russo-Japanese War, the resurgent interest in migration to Brazil was a direct result of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. In 1905, Japan’s minister in Brazil, Sugimura Fukashi, sent a report to Tokyo that advocated Japanese migration to Brazil. Later published by Osaka Asahi News (Osaka Asahi Shimbun), this report pointed out that the Italian government’s decision to suspend migration to Brazil had led to a labor shortage in the country. While white racism against Japanese in the United States, Canada, and Australia had worsened, Sugimura argued, Brazil would be an ideal alternative for Japanese migrants. He also encouraged migration agents in Japan to visit Brazil in order to explore the opportunities firsthand.Footnote 55

The state of São Paulo in Brazil welcomed the Japanese immigrants for two reasons. The first was that it expected these migrants’ arrival would foster the further growth of its coffee economy. The migrants would fill the labor vacuum created by the suspension of migration from Italy and open up Japanese market to Brazilian coffee – the ships that ferried the migrants to Brazil were expected to carry local coffee back to Japan. Paulista elites also believed that the Japanese migrants would turn the sparsely populated lowlands along the coast into productive farms.Footnote 56 With such expectations in mind, the state of São Paulo offered financial support for the endeavor.

Two migration projects, spearheaded by Mizuno Ryū and Aoyagi Ikutarō, respectively, were carried out with Brazilian support. Both Mizuno and Aoyagi believed that overseas migration was necessary not only to solve Japan’s overpopulation issue but also to strengthen the Japanese empire,Footnote 57 and both men had previous migration experience elsewhere.Footnote 58 While their Brazilian migration projects represented two different models of migration – Mizuno’s focused on contract labor while Aoyagi’s focused on farmer migration with land acquisition—they were both ideological heirs to the earlier Texas migration project.

Uchida Sadatsuchi, the initial architect of Japanese agricultural migration to Texas, became the Japanese consul in the state of São Paulo in 1907. He served as an advocate for Mizuno’s plan of Brazil-bound migration within the Japanese government. Japanese labor migration to Brazil, he reasoned, would eventually result in agricultural settlement like it had in Texas. He further argued that this time around, the settlement project was destined for success because, unlike the Americans, the Brazilians were not racist against the Japanese.Footnote 59 Uchida also played a central role during the initial negotiations between the state of São Paulo and the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that made it possible for Mizuno Ryū to transport 781 Japanese migrants to Brazil in June 1908 via the ship Kasato-maru.Footnote 60

The state of São Paulo had partially subsidized the migrants’ trip expenses with the expectation that they would work in the designated coffee plantations (fazendas) as laborers (colonos). The initial phase of the project, however, was not met with success, as Mizuno’s poor planning led to company bankruptcy and caused misery for many of the first-wave migrants.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, Mizuno was able to continue his migration career via the newly established Takemura Colonial Migration Company (Takemura Shokumin Shōkai).Footnote 62 Between 1908 and 1914, Japanese labor migration to Brazil remained unsuccessful due to conflicting expectations of the Japanese migrants and the Brazilian plantation owners. The former, misled by migration companies to a degree, thought they could quickly make a fortune in Brazil. The latter, on the other hand, saw the migrants as exploitable cheap laborers who would accept a low standard of living and below-average wage. In 1914, unsatisfied with the Japanese immigrant laborers’ performance, the state of São Paulo suspended its subsidy for Japanese migration. Worried that anti-Japanese sentiment would raise its head in South America like it had in the United States, Tokyo decided to halt further labor migration to Brazil.Footnote 63

Aoyagi Ikutarō’s migration project, on the other hand, closely resembled the earlier Japanese rice farming experience in Texas. Its participants arrived in Brazil as owner-farmers with long-term settlement plans. To take advantage of a law enacted by the state of São Paulo in 1907 that provided subsidies and land concessions to any migration companies that brought in agricultural settlers, a group of Japanese merchants and politicians formed the migration company Tokyo Syndicate. As the head of this company, Aoyagi planned to establish Japanese farming communities in Brazil by purchasing the lands at a low price in São Paulo and then selling portions to individual Japanese farmers. In 1912, the state of São Paulo granted fifty thousand hectares of uncultivated land in the Iguape region to Tokyo Syndicate under the condition that the company would relocate two thousand Japanese families there within four years.Footnote 64

The year 1913 was crucial to Aoyagi’s success. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 showed the Japanese leaders how important landownership was to successful migrant expansion. Aoyagi’s efforts in Brazilian land acquisition thus caught the attention of Shibusawa Ei’ichi, a founding member of the Emigration Association and the central figure in the Japanese American enlightenment campaign. Shibusawa was well aware of how Japanese immigrants in California had suffered when they were deprived of their landownership; he became a passionate donor to and supporter for Aoyagi’s campaign in Brazil. Under Shibusawa’s leadership, a group of Japanese entrepreneurial elites formed the Brazil Colonization Company (Burajiru Takushoku Gaisha). With endorsements from the second Katsura Cabinet, the Brazil Colonization Company took over from Tokyo Syndicate to further expand land acquisition in the state of São Paulo while keeping Aoyagi Ikutarō at its helm.

This new company not only secured the ownership of the Iguape Colony but also purchased fourteen hundred hectares of land in the Gipuvura region from the state of São Paulo. In recognition of the support offered by the Japanese government, the company named their new property Katsura Colony after Katsura Tarō, the prime minister.Footnote 65 The imperial government was not the only party that was interested in experimenting with farmer migration in Brazil. Beginning with Shibusawa Ei’ichi, there was a number of Japanese entrepreneurial elites who also played a key role in Aoyagi’s Brazilian land acquisition initiative. As most of their businesses depended heavily on Japan-US bilateral trade, they were interested in exploring alternative overseas markets to make up for the possible profit loss caused by the Americans’ anti-Japanese stance. They believed that land acquisition in Brazil, coupled with Japanese farmer migration and permanent settlement, would open up more business opportunities for them.

Aside from government officials and business tycoons, Aoyagi Ikutarō’s project also had supporters in the intellectual circles. In 1914, Kyoto Imperial University professor Kawada Shirō published his study of Brazil as a potential colony for Japan. Titled Brazil as a Colony (Shokuminchi Toshite no Burajiru), this book was the most representative product of the Japanese Malthusian expansionists’ debate during the 1910s in response to the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement and the passage of the Alien Land Law in California. It pointed to Brazil as the most pragmatic alternative to the United States for Japan’s surplus people. Brazil was the ideal destination for Japan’s surplus population because it had fertile and spacious land, a small population, and no race-based restrictions on citizenship or property rights.Footnote 66 At the same time, Kawada also pointed out, not all types of migration were desirable. Like Tōgō and Ōkawadaira, he stressed the difference between the less desirable emigration (imin) and the more desirable colonial migration (shokumin). Kawada paid special attention to the Brazilian Colonial Company as the first Japanese company to conduct “colonial migration” (shokumin), which was different from the previous migration endeavors that exported only the less desirable imin – that is, the contract laborers and temporary emigrants.Footnote 67 Kawada argued that Aoyagi’s campaign, with its mission of acquiring farmland and helping Japanese peasants to permanently settle overseas, represented colonial migration rather than emigration. More importantly, it was the former that best served the interests of the Japanese empire.Footnote 68

The Success of Farmer Migration in Brazil

Farmer migration with land acquisition in Brazil was the Japanese expansionists’ answer to American racism against their compatriots. It was also ideologically complementary to the Japanese American enlightenment campaign that was under way at around the same time. However, the actual success of Aoyagi’s project depended on a few contingent but indispensable global and local factors. The outbreak of World War I, the existing flow of Japanese laborers to Brazil, and the specific conditions of coffee and cotton plantations in the state of São Paulo all contributed to the campaign’s success.

Although Aoyagi was successful in securing financial support, he had considerable difficulty recruiting migrants from Japan to Brazil. Japanese farmers were naturally reluctant to join this venture: not only did they have to permanently leave their homeland, they also had to fork over a significant amount of cash in order to purchase farmlands from the Brazil Colonization Company. Farmers who already owned land in Japan had few reasons to take the risk, while the landless farmers struggled to meet the financial requirement. For the latter group, migrating to Brazil as plantation laborers was only possible if their trips were subsidized. As a result, a majority of the initial setters in the company’s colonies were Japanese contract laborers in coffee plantations who were already living in Brazil. For example, among the first thirty-three families who settled in the Katsura Colony in 1913, only three were recruited from the archipelago; all the rest were Japanese laborers who had left their previous plantations in Brazil.Footnote 69

Thus, in a stroke of irony, even though agricultural migration was slated to replace the “outdated and undesirable” model of laborer migration, it was the latter that provided the former with sufficient human capital for its initial success. The revival of Japanese labor migration was an immediate result of World War I, as the outbreak of the war led to a catastrophic decline in labor supply for the Brazilian coffee plantations. The annual number of new immigrants arriving in Brazil dropped from 119,758 in 1913 to a mere 20,937 in 1915. To make matters worse for the plantations, some European laborers already in their employment returned to their home countries, while still many others left for the cities to work in the more lucrative war-related industries.Footnote 70 Such an unexpected and urgent need for coffee plantation laborers eventually pushed the state government of São Paulo to resume its subsidy for labor migration from Japan in 1916.Footnote 71

While the constant flow of laborers from rural Japan to coffee plantations in São Paulo provided a stable supply of potential farmer-settlers, the very structure of the Brazilian rural economy made it not only possible but also necessary for the Japanese laborers working on coffee plantations to gradually transform themselves into landowning farmers. The low wages these laborers received caused them much disappointment, but it also made it impossible for them to quickly return to Japan; thus they had to focus on improving their station in life while staying in Brazil. At the same time, the cultivation of alternative crops such as rice and cotton proved to be highly lucrative. While urbanization and industrialization increased the demand for rice as food and cotton as raw material, most of Brazil’s rural landlords showed little interest in switching from coffee to these crops. The increasing demand for rice and cotton and the lack of local supply left a niche spot that the Japanese immigrants could ably fill. Having grown up in rural Japan, most of them had farming skills before coming to Brazil, and a lack of competition from the locals all but guaranteed their profits. In addition, unlike coffee, which required a multiple-year cycle to yield investment return, rice and cotton were annual crops that allowed farmers to quickly accumulate wealth with little initial investment. Therefore, even though their income levels were low, it was not difficult for Japanese migrants working on coffee plantations to purchase their own lands by cultivating rice and cotton in their spare time.

Under the management of Brazil Colonization Company, the region of Iguape became highly attractive to Japanese migrant laborers. In addition to dividing its land into small portions and allowing immigrants to purchase them by annual installments, the company’s management of Iguape provided the Japanese immigrants with a sense of community. For example, the residents of Katsura Colony, the first settler community in Iguape, were able to communicate in Japanese in daily life, enjoy Japanese food such as rice and miso, and purchase Japanese goods at reasonable prices in local stores.Footnote 72 The Registro Colony, the second settler community in Iguape, founded in 1916, featured a medical clinic and its own brick and tile factories. Later on, both Katsura and Registro colonies also established schools.Footnote 73 In 1917, the Brazil Colonization Company started offering loans to every Japanese family – be they located in Japan or Brazil – that would come live in Registro. As a result, the number of new families who moved in grew from twenty in 1916 to one hundred fifty in 1918.Footnote 74

Iguape: A Turning Point

Between 1914 and 1917, while the total settler population in Iguape remained low, the number of recruits grew rapidly every year. The growth and stability of Japanese settler communities in Iguape during these years marked a turning point in the history of Japanese migration in Brazil for two reasons. For one thing, long-term opportunities in Iguape attracted more and more Japanese immigrants who came to Brazil as contract laborers to stay and give up their plan of returning. For another, the prosperity of Iguape also drew increasing support from the imperial government in Brazilian migration.

Figure 5.3 Hundreds of bags of rice produced by Japanese immigrants piled up on a railway that connected the Japanese community in Registro with other parts of Brazil. This picture was also used by Japanese Striving Society’s president Nagata Shigeshi for his speeches around Nagano prefecture in late 1910s to promote Japanese migration to Brazil.

First, to those who initially migrated from Japan to Brazil as plantation laborers with the goal of returning home, the success of their peers in Iguape helped to motivate them to settle down and acquire lands for themselves. By 1920, Japanese immigrants in Brazil were more likely to own farmland than any other ethnic group. During that year, the Japanese immigrants held 5.3 percent of the alien-owned farmland in São Paulo, while they constituted only 4.3 percent of the state’s foreign population.Footnote 75 In the same year, 94 percent of Japanese living in Brazil were engaged in agriculture in one way or another,Footnote 76 a figure that was in sharp contrast to the Japanese communities in Northeast Asia and the South Seas. By then, expansionists in Tokyo were convinced that agricultural migration was the most desirable migration model for the expanding empire. Yet only in Brazil, buoyed by specific local and global contextual factors, did agricultural settlement prove to be the most profitable choice for Japanese migrants.

Second, the prevailing trend of Japanese laborers in Brazil repositioning themselves as independent farmer also prompted the imperial government to take a fresh look at the value of labor migration. Indeed, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs endorsed Mizuno Ryū’s initial campaign of labor migration to Brazil in 1908 because it expected that these labor migrants would eventually settle down in South America as independent farmers.Footnote 77 However, it was the growing size of laborer-turned-independent farmers in Japanese Brazilian communities that proved the model’s merits to Tokyo. Thus convinced, the Japanese government became further involved in expanding and managing labor migration projects overseas in general and to Brazil in particular.

Between 1917 and 1918, four leading Japanese migration companies, including the South America Colonial Company (Nanbei Shokumin Kabushiki Gaisha), managed by Mizuno Ryū, merged into the Overseas Development Company (Kaigai Kōgyō Kabushiki Gaisha), commonly known as Kaikō for short.Footnote 78 After acquiring the Morioka Emigration Company (Morioka Imin Gaisha) in 1920, the Kaikō became the only government-authorized Japanese migration company operating in Brazil. At the time of its formation, the Kaikō primarily ran on private funds, but it maintained close ties with the government.Footnote 79 Not only was its first director Kamiyama Jūnji a former bureaucrat, its very inception was endorsed by Tokyo with the goal of consolidating the migration companies so that the government could monitor and manage overseas migration more effectively.Footnote 80

The Kaikō’s initial task was recruiting farmers from rural Japan and relocating them overseas as contract laborers. Aside from coffee plantations in Brazil, it also sent migrants to work on sugar plantations and mines in other places around the Pacific Rim such as the Philippines, Australia, and Peru. Nevertheless, labor migration to Brazil claimed an increasing share of the Kaikō’s business and became its dominant source of revenue from 1920 onward.Footnote 81

In 1919, the Kaikō expanded into South America by merging with Aoyagi’s Brazil Colonization Company, taking over the latter’s land property and business in Brazil. Through this merger, the Kaikō combined the previously separate labor migration and farmer migration projects. More human and financial resources were then poured into the program of land acquisition in Iguape.Footnote 82 During the next year, the Kaikō established a third settler community named Sete Barras Colony in Iguape next to Registro. The company built roads to interconnect the three Japanese communities, linking them with river ports and adjacent Brazilian towns. With support from the imperial government, the Kaikō also began to integrate the domestic aspects of the migration campaign such as public promotion, candidate selection, and predeparture training. The migrants were expected to show their absolute dedication to the empire by permanently settling overseas as independent farmers, extending the Japanese empire’s influence to the other side of the Pacific.

While the social mobility of the Japanese laborers-turned-owners in Brazil attracted increasing support from Tokyo, it also prompted the state of São Paulo to suspend its subsidy to Japanese immigrants. As more and more Japanese laborers left their original plantations to take up independent farming, São Paulo’s policymakers became convinced that it was no longer cost-effective for their coffee plantations to seek out laborers from Japan.Footnote 83 This conclusion was also made at the moment when migrants from Europe once again began to pour into Brazilian plantations at the end of World War I. Despite the Japanese perception of racial equality in Brazil, the Brazilian government had always deemed European immigrants to be more desirable than those from Asia. In 1922, the state of São Paulo officially ended its subsidy for Japanese labor migration.

Toward a New Era of Japanese Settler Colonialism

The decline of São Paulo’s interest in Japanese laborers, however, did not put an end to the flow of Japanese migration to Brazil. On the contrary, the number of Japanese immigrants in Brazil grew at a rapid pace after the turn of the 1920s. Growth of the Japanese migration flow to Brazil was accompanied by the overall changes in Japanese migration-based expansion in general, marked by the emphases on permanent settlement and the importance of women and the increasing involvement of the Japanese government in migration promotion and management. These changes were consolidated by a series of international and domestic events that took place in the first half of the 1920s.

In 1920, the California Alien Land Law was revised to close many significant loopholes that had existed in the original 1913 version. With Japanese American farmers as its primary target, the revised law banned aliens ineligible for citizenship from purchasing land in the names of their American-born children or in the names of corporations. Both practices were popular with Japanese immigrant farmers in California as ways to circumvent the original law. In addition to the right of purchasing and long-term leasing lands, the Japanese immigrants’ right of short-term land leasing was also taken away from them. This revised law not only dealt a fatal blow to Japanese American farmers in California but also convinced Tokyo that the Japanese American enlightenment campaign had failed. In 1922, the Japanese government had to “voluntarily” stop issuing passports to picture brides to avoid fanning further anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. In the meantime, while Asia and the South Pacific appeared to be unattractive destinations, white racism in North America spurred the Japanese expansionists to gaze into Brazil. The success of Japanese agricultural settlement in Iguape convinced Japanese policymakers that migration to Brazil was worth the financial investment.

Emerging amid the waves of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States and the Japanese American enlightenment campaign, Japanese Brazilian migration immediately inherited the campaign leaders’ emphasis on the principle of permanent settlement and the importance of women in Japanese community building. The Brazilian migration was carried out with efforts in fostering both land acquisition and family-centered settlement. For example, the Overseas Development Company that sent most of Japanese migrants to Brazil in the 1920s and 1930s, recruited migrants in family units instead of individually. To be qualified to sign the contract of migration with the Kaikō, each migrant family had to comprise at least three adults (above the age of twelve).Footnote 84

Figure 5.4 Kaikō poster from around the mid-1920s to recruit Japanese for Brazilian migration. It clearly illustrates two expectations on the migrants: (1) they were supposed to migrate in the unit of family; (2) with the hoe in hand, the central figure in the poster is a farmer. This indicates that migration should be agriculture centered.

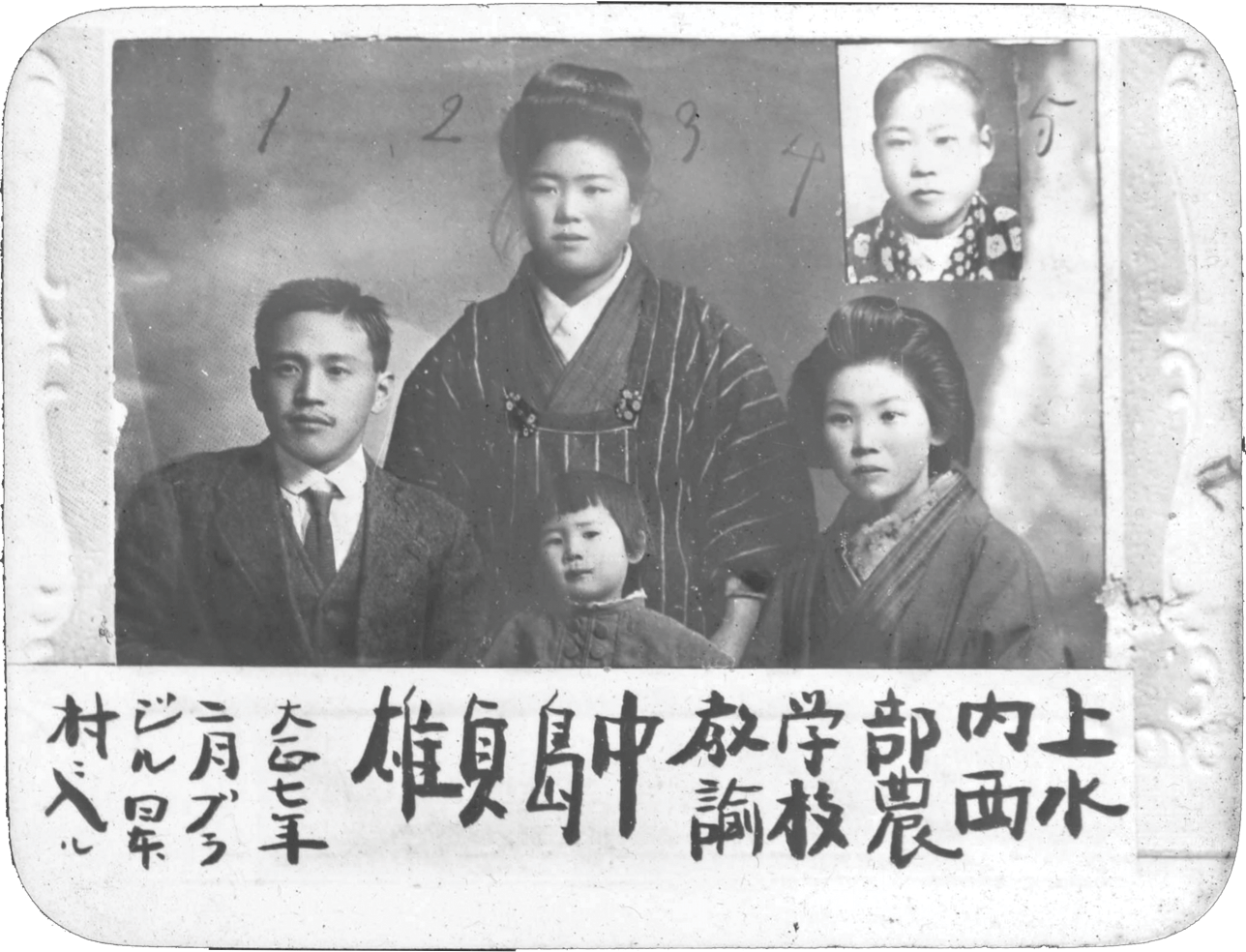

Figure 5.5 Magic lantern slide that the Japanese Striving Society’s president Nagata Shigeshi used during his speeches around Nagano prefecture in late 1910s to promote Japanese migration in Brazil. It is a picture of the family of Nakamura Sadao, a schoolteacher from Kamiminochi County in Nagano prefecture, who migrated to Registro, Brazil, together in 1918. Family migration had begun to be the norm for Japanese migration to Brazil around that time.

White racism in North America not only made Brazil increasingly attractive as a colonial target for Japanese Malthusian expansionists but also convinced them of the importance of permanent settlement and the role of women in Japanese overseas community building. On the other hand, the continuation of rural depression in Japan brought about a structural change in the imperial government’s support for migration. Two years after the Rice Riots (Kome Sōdō) of 1918, the government created a Bureau of Social Affairs under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Aside from tending to issues such as unemployment and poverty, the Bureau of Social Affairs was also tasked with promoting and managing overseas migration. This institutional change signaled that the Japanese government had come to recognize overseas migration as an important tool to combat domestic social issues; it was no longer a purely diplomatic matter under the sole management of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Great Kantō Earthquake (Kantō Dai Shinsai) of 1923 further stimulated the Bureau of Social Affairs’ migration promotion. To forestall unrests following the disaster, the bureau began to provide full subsidies for migration to Brazil through the Kaikō. It offered thirty-five Japanese yen for each Brazil-bound migrant whom the company recruited, a sum that covered the costs of both enrollment and transportation, making migration to Brazil free of charge for the migrants themselves.Footnote 85 The number of Japanese migrants to Brazil jumped from 797 in 1923 to 3,689 in 1924.Footnote 86

Meanwhile, the Immigration Act of 1924 put a complete stop to Japanese immigration to the United States. At the Imperial Economic Conference held in Tokyo in the same year, Japanese Diet members, government officials, and public intellectuals reached an agreement that the existing government policy on overseas migration needed an overhaul. The participants recognized the importance of overseas migration both as a way to alleviate overpopulation and rural poverty at home and as a means of peaceful expansion abroad. To avoid repeating the migration project’s failure in North America, they demanded that the government increase its support for migration by playing a central role in protecting and training the emigrants.

The imperial government carried out this conference’s agenda in the following years, and a new era of Japan’s migration-based expansion thus began. From 1924 onward, the Japanese state – at both central and local levels – took on an unprecedented degree of responsibility in financing, promoting, and organizing emigration programs to Brazil and later Manchuria. This new era of migration also saw a radical departure from its past practices in terms of the migrants’ social status. Given the continuing rural depression and full government subsidy for the migrants, the most destitute residents in the Japanese countryside became involved in the imperial mission of expansion.

Conclusion

This chapter has examined the two courses of action in Japanese overseas expansion between the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1907 and the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924. Seeing overseas migration as an effective solution to the ever-growing surplus population in Japan, the Malthusian expansionists sought to placate the anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States while exploring alternative migration destinations. Both courses of action were marked by their efforts at embracing the logic of Western imperialism so that Japan’s own expansion could fit into the existing world order as to share the “White Man’s Burden” instead of challenging the hegemonic powers.

At the same time, most migration-related campaigns during these years were ultimately unfruitful. In the United States, the enlightenment campaign spearheaded by the Emigration Association ended with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924. While the period between the late 1900s and the 1920s witnessed an expansion of Japanese colonial presence in Northeast Asia and the South Seas, Japanese farmer migration and settlement in these parts remained disappointing when measured against the expansionists’ visions. An exception to this norm was Brazil, where Japanese migrants were able to build and expand their farming communities. Encouraged by what happened in Brazil, the Japanese government began to provide unprecedented support to expand Japanese migration to Brazil when the outlook for US-bound migration grew dim. The history of Japan’s migration-based expansion entered a new era (from the mid-1920s to 1945) with a radical departure from the past in terms of the degree of the state’s involvement, the social statuses of migrants, and the relationship of Japanese expansion with Western imperialism. The next two chapters will examine these radical changes and explain the new ways in which the discourse of overpopulation legitimized and shaped Japanese expansion in this new era.